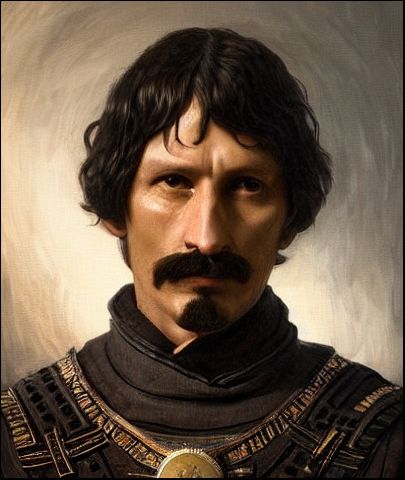

Cover based on a picture created from

historical data by the Deep AI image generator

An ebook published by

Project Gutenberg Australia

The Triumphant Beast

Marjorie Bowen:

eBook No.: 2300801h.html

Language: English

Date first posted: Jun 2023

Most recent update: Jun2023

This eBook was produced by Colin Choat and Roy Glashan

Cover based on a picture created from

historical data by the Deep AI image generator

A portrait of Giordano Bruno

(created from historical data by the Deep AI image generator)

THE murderer whimpered a prayer to the cascade of stars and began to drag his victim down the slope soft with spring grasses and flowers. There had been a furious struggle and he felt exhausted; one of his fingers ached violently, he believed that it was broken; the other man's body was heavy, too, and difficult to tackle; sometimes, in the half-dark, Gioan seized the shirt instead of the coat and felt the linen tear.

Perhaps, thought the murderer, it really would be better not to try to hide the body or even try to escape. Justice of God, if not justice of man would find out and punish him, whatever he did.

He sat down on a boulder and sighed; a tall pine tree made a black pattern between him and the purple sky which was full of falling stars. Never had he seen so many; thousands of them, in a fiery rain, glittered over the city and were reflected in the bay. What did they, mean? A portent, no doubt, but there never were portents for wretches like himself—the falling stars must mean more wars, slaughters, and conspiracies among the great ones, perhaps some prince had been slain in Portugal where the fighting was and where he might have been, earning good pay and a chance of plunder if he had not been useless by reason of his crooked leg, lame from the wound he had received in Flanders.

Gioan wiped the sweat off his face with the back of his hand and bemoaned his ill-luck. Why should all the captains have refused to take him when they were recruiting? He was still able to kill a man. He peered down at the dark heap by his feet—all that was left of the creature who had been so lusty, strong, blasphemous, and so difficult to overcome until he had had that dagger in his breast.

Somehow he must be pushed down the hill and into the sea. Yes, that was the best plan, then, perhaps he would not be found until he was so devoured by fishes and rotted by water that no one would know who he was.

Gioan shivered; the stars seemed to be falling close beside him on either hand, as if they darted into the grasses and the wild vines and were extinguished in the dew. For the first time he was conscious of immensity. It seemed to him impossible to compute the size of the heavens or of the bay, and compared to this unfathomable grandeur of air and water, the city, which hitherto had always appeared to him the most magnificent object possible, seemed quite small and unimportant.

He sighed, crossed himself, rose, and clutched desperately at the prone man. He thought that it would be much easier if he were to kick the corpse down the hill, but he did not want to do that. Tears came to his eyes because of his weakness and all the difficulties and the reaction after the fight.

The man whom he had thought dead spoke and Gioan began to cry.

"Gioan, are we on the hill?"

"Yes." Gioan knelt down to hear what the small, tired voice whispered. "You are not, then, slain!"

"Yes. I shall only live a little while. It is a mercy, which I don't deserve. How these stars confuse one's senses! We seem to be in the midst of them."

"Yes, it is a great miracle, or mystery. They make me feel giddy too. What shall I do for you, Silvestro? Could you get up if I supported you?"

The two men talked together gently, almost affectionately, as if they had never quarrelled. Silvestro had changed completely since his swoon, he no longer was harsh, bullying, full of rage and contempt, but humble and peaceful.

He tried to rise, Gioan helping him. He named him brother and whispered:

"God has given me this little time in which to make my peace. Brother, find me a priest."

Gioan could not think how this could be done; they were both so exhausted and it was not easy to see the way. But he became absorbed in the desire to save his enemy's soul which he had never thought of before.

Silvestro, leaning against the stone, whispered again:

"You cannot do it—they would arrest you. But we might tell them some tale."

"I do not think of that, only of how to find the priest. It is true that a moment ago I wanted to drag you down to the sea for the fishes to eat, but now I only want to help you."

"Think then, quickly, of something, for surely I am dying."

"There is my brother," said Gioan. "Often, when the weather is very warm or there is something wonderful in the heavens he will be in the garden by the cottage, if we could find him—"

"It is too far for me to reach the monastery," Silvestro sighed, and drooped over the boulder; when Gioan shook him he did not speak. The stars fell glittering about the two men, showers of them, thousands of them, like the fireworks on the Viceroy's birthday.

Gioan crept round the convent wall; the tall dark trees hid the heavens from him, he could hear the rustling of the ilex leaves like water running in a still place; he saw at an angle of the wall a glimmer that he knew to be the gardener's cottage, greyish opaque in the starlight and close to that another blur that he was sure was his brother's white habit showing under the black cloak.

"Felipe!" he used the monk's baptismal name, and as he spoke he fell on the grass exhausted and sobbing. But when he heard his brother's tender voice he was as comforted as if a weight had been lifted from his breast.

"Gioan! You are panting, weeping! You are in trouble—tell me."

"I have killed a man. But he is still alive, he longs for a priest—he is out on the hill."

The monk rose, the prone man clasped the edge of his white habit; there was comfort in the feel of the rough cloth, to the edge of which stuck small fragments of dried grasses.

"Oh, the stars, the stars, Felipe! They make me feel giddy—I thought you would be here, watching them—"

"Rise, Gioan. I shall fetch a lantern from the cottage and we will bring this man in—"

"No one will see us?"

"No one. I am allowed the cottage for a little while. The gardener is in the other capanna. They know that I often go on the hill at night, no-one will be surprised. Who is the man?"

"Silvestro."

"So young!" the monk's voice was sad with compassion. He drew his robe gently out of his brother's nervous fingers and turned through the white gate. Very quickly he returned with a lantern; it seemed like a larger, duller star hanging in his hand and the beams showed his coarse white robe and brown sandalled feet, while the upper part of his black-clad body was dim in the purple shade. Gioan, panting and distressed, limped a step ahead to show the way.

"Why did you do this, Gioan? Silvestro was so young, and no worse than others."

"I did it because of you, Felipe."

"Ah? I think that is a lie."

"No, no! Silvestro has been mouthing ugly scandals of you, even in the city streets—that you are a loose-liver and don't keep your vows. That you are a heretic and will soon be denounced."

"You slew him for that? And why here?"

"I followed him from the city—to a quiet place."

"Why did he come here?"

"To spy on you. He said that you had too much liberty, that observing the heavens was only an excuse, that the Prior let you out just to see how far you would go. I sprang on him from behind—he fought, I thought that I could have mastered him easier—it is this accursed leg—"

"Hush, Gioan. You are losing your breath. You must save your strength if you are to help me with Silvestro. If he thinks evil of me I shall not be very welcome to him—"

"I was afraid to fetch anyone else. It should be here. Hold up the lantern a little, Felipe. Yes, there he is."

They approached the man huddled on the wild vines which were covered by strong shoots and curling tendrils; they could hear the distant sound of the waves breaking on the rocks below. The falling stars had vanished, fixed constellations dazzled overhead, the moon was rising, the air became colder.

The monk put the lantern on the boulder and went on his knees beside Silvestro; the beams, like the spokes of a wheel, radiated light into the darkness that was fading into pallor with the strengthening of the moonlight.

"He is alive. Perhaps we can save him. I can stop the bleeding—tear up your shirt. Then we will carry him to the cottage, for we do not know who may be on the hill."

Gioan sat in the gardener's cottage and gazed at the man on the pallet bed; everything seemed strange and he felt light-headed. He wondered why he had killed Silvestro, already the violent fight seemed far away.

The room was small and of white stone; there was a stool near the pallet bed, a cupboard in one corner, a table on which were some books and the lantern, and the bench where Gioan drooped.

On the wall opposite the bed was a crucifix in metalwork and beside it was a door opening into a small kitchen. Silvestro lay straightly, his chest bare save for the bandages of Gioan's shirt; the monk's black cloak had been rolled as a pillow for his head. Gioan had never noticed before how red and glossy was the hair of the dying man nor how sharply his eyebrows sprang from the base of his nose, like wings.

Gioan was quite sure that Silvestro was dying, and he longed to question his brother who sat so quietly with his hands folded in his wide white sleeves and his chin sunk on his breast. The monk was younger than Gioan by a few years, he was about thirty, of middle weight with a countenance of singular nobility, his mouth and his hands were beautiful, his dark thick hair grew long round the tonsure; his black eyes were lively and formidable, his lean cheeks brown. The long, aquiline nose was delicate with sensitive, flaring nostrils, he had the air of a man of much vivacity who contains himself for a deliberate purpose.

Gioan was like him in shape and feature and yet an ordinary man where his brother was extraordinary. He had been coarsened by his profession, which was that of a soldier, yet he had an air of simplicity. The injury to his knee which made him lame had distorted his whole body; his clothes were ragged, and where he had torn his shirt for bandages his hairy chest and arms showed.

Silvestro began to mutter; he had been unable to take the strong native wine that the monk had tried to force on him, there were stains of it on his chin and chest.

"Bring me," said the monk without moving, "the viaticum which I have put ready in the box in the kitchen."

Gioan obeyed. Two candles burnt in the kitchen which was small and very clean. There was a pan of charcoal on a brazier, several pots of herbs, ewers of water, and two wounded pigeons lying in a basket. Gioan fetched two fresh candles, the bottle of oil, the vessel of water, folded a clean linen napkin and the box of wafers which Felipe had set ready. He felt as if he was about to die himself and he wondered about the pigeons—were they for supper? Why did Felipe take such care of them in the basket with fresh grass at the bottom?

Silvestro spoke, thickly and without sense; he cast up his eyes and his lips were the lilac colour of the wine stain on his chin. The monk prayed; Gioan was awed by his beautiful voice and the Latin words; he too knelt and tried to pray, but he was so tired and his finger hurt; he had twisted a piece of the shirt torn up for Silvestro round it, and he noticed that the rag was black and stiff with blood.

Silvestro was dying, and Gioan was a murderer; he looked up at his brother who was placing the wafer on Silvestro's lips that were muttering gross nonsense. The monk's face was serene, earnest, intent on his task. Gioan had seen that look on his face when they had stood in the home fields at Cicala and stared at Monte Somna, knowing that Vesuvius, the great volcano, was behind. The monk's face had the quality of metal, wrought silver or fine bronze, it seemed formed for some peculiar and definite purpose; he had always awed Gioan, to whom he was unalterably kind.

He sprinkled the dying man. "Te asperges..."

Silvestro struggled a little and spat out the wafer; without recognizing anyone he died.

"I have done what I can," said the monk, rising, and placing the napkin over the dead youth's twisted face. "Now I must think of you."

Gioan remained on his knees, he felt sad, tired, and homesick. He wished that they were boys together again in the sweet meadows outside Nola with their mother calling to them from the doorway of their home to food and rest. It seemed stupid to be a soldier, stupid to be a priest, very stupid to kill a man.

"Oh, Felipe!" he sighed, and limped to his feet.

The monk had gone into the kitchen, taking one of the candles with him. He was washing his hands with a ball of white soap in a crock of yellow earthenware. He had put bay leaves and wild thyme into the water and cast some herbs on the charcoal brazier that gave a pungent odour. His loose white habit was the colour of the walls, only his serious, reserved and imperious face and his fine hands from which the water dripped were dark and vivid. He had been outside and thrust a book into a heap of rotting manure. Carefully he washed his hands.

Gioan stared at the pigeons; their feet were tied with a thread. They were still alive and that seemed odd now that Silvestro was dead.

"They were being sold for food," said the monk. "I bought them for a penny."

"How did you get the money?"

"When I was in the city an old man at the door of a shop asked me to read a letter for him. He gave me a penny for the poor."

The monk dried his hands that on the back were covered by long, fine, dark hairs.

"What are we going to do, Gioan? There will be a scandal when Silvestro is found here."

"We could drag him out and throw him into the sea. I was going to do that when I found that he was still alive."

"No. That would beastly. It is time, too, that I left Naples. We will go together."

Gioan was astonished, but pleased, too. He felt that if he had his brother with him it would be like being protected by a god. "You mean that you will leave the monastery?"

"Yes. No one will question a wandering monk."

"Are you afraid?" whispered Gioan with deep sympathy. "They are going to punish you? What have you done?"

"Gioan, there is not time to talk. I have long thought to go out and see the world, and your misfortune has decided me."

Gioan was troubled, he remembered that Felipe had been in difficulties several times with his superiors—yes, even when he was a novice, for giving away to poor old women images of Saint Catherine of Siena, and of Saint Anthony of Padua, as if they were of no importance, instead of keeping them in his cell to worship. But Gioan comforted himself by recalling that his brother had been so brilliant a scholar that he had been made a sub-deacon and deacon when he was only a boy and ordained a priest when he was twenty-four years of age. He had written books, too, and this was very marvellous to the poor soldier who could not read, and he had been taken in a coach to Rome because of his learning, and there, before the Pope himself, he had expounded his theory of memory training, and recited a psalm in Hebrew.

The monk looked keenly at his brother's bewilderment and gave a swift smile.

"Don't be so distressed, Gioan, it is a pity that you slew Silvestro; he was a bad man, but young. And it was a pity that he did not know I was there to give him absolution. But these things are past. If you would save your life you must come with me from Naples. It is well that you have neither wife nor child to leave behind."

A slight distortion passed over the soldier's dark pallid face.

"How shall we live?" he asked sullenly. "I have hardly any money and you have nothing at all."

He glanced round the bare poverty of the kitchen; the monk was untying the threads from the legs of the pigeons.

"They have recovered," he said, "there is a little blood on their wings and their feet are bruised, but they can fly again."

He took the basket to the open door and the birds fluttered, a quiver of lilac and green in the candlelight, then flew away into the night and the rustling of their wings became one with the rustling of the unseen ilex trees.

The two men went down in the moonlight towards the city. Gioan spoke of the falling stars, he asked his brother if he knew what portent there might be in those celestial marvels.

"Nothing," said the monk. "It is only a manifestation of God."

Human lights were before them in the purple dark—the lamps of the city and on the prows of ships in the harbour.

"Where shall we go?" asked the soldier, "they will pursue us on horses and soon overtake us."

"They will not know which way we have gone," replied the monk; he gathered up his robe so that he could walk with more ease.

They entered the suburbs of the city and the strong, sweet perfumes of the hill-side were lost to them, and they were surrounded by the foul exhalations of gutters and garbage heaps, the smell of greasy cooking and the taint of decaying meat and fish.

They had not gone far before they paused under a broken wall-lamp which showed a mean dwelling with a gaudy sign. It was a small puppet theatre which the soldier had kept since he had been disabled from the army. With the rag and wooden dolls gaily dressed in scraps of stuff he begged from his uncle the velvet Weaver, he had been able not only to earn his living and pay two assistants, but to send a few shillings now and then to his mother, who lived with her sister at Cicala since her husband, the stout old soldier, had gone to the wars in Portugal.

The ground floor of the little house was the theatre; a curtain of canvas painted with stars, and a rude scrawling meant to represent the Arms of Spain, Leon, and Castile, divided the stage from the rows of dirty benches where the audience sat.

Now it was empty. The brothers groped their way over the filthy floor to the back of the stage where the puppets with strings and weights attached to their heads, legs, and arms lay sprawling out of their boxes. Here there was a light, a candle on a broken table, and by it sat a boy with a small drum on his knees. As soon as he saw his master he began to beat this vacantly; he was simple in his mind and weakly in his body and could do no other work than this. Gioan employed him because he required no money, only food and a place to sleep.

The monk smiled at him and gently took away the sticks, telling him he need not drum tonight as there would be no performance.

"Shall we take him with us?" he asked his brother.

The soldier shook his head.

"What should we do with an idiot? We are hampered enough already." Then, in a timid voice that he was not able to raise above the level of a sigh, he implored: "Giulia? Giulia!"

"She will never hear that," smiled the monk. In a high, clear voice he called: "Giulia!" so that the word rang beautifully, like clear notes of music in the poor place. The boy had secured the drum-sticks again and began tapping on the drum, bending his head sideways to listen.

The ragged curtain at the back was-raised, and Giulia entered. She was the girl who helped to work the puppets and who, in a thin, squeaky voice recited the words of the female dolls. She was seventeen years old, straight and delicate in every line. Her brilliant hair, which seemed to have the colour of all the metals in it, gold, silver, bronze, and copper, was gathered into a green kerchief and hung so heavily on the nape of her thin neck that it seemed as if she bore a great treasure bound on her forehead and supported on her neck.

"What do you want to tell her asked the monk, for his brother stood mute under the girl's bright gaze.

"What is there to tell me?" asked Giulia quickly.

"I have hurt my finger," muttered Gioan, and he held out his hand disfigured by the bloodstained rag.

"It is worse than that," said the monk serenely, "Gioan has killed a man and I am in danger of arrest, and we intend to leave Naples."

"You, too!" exclaimed the girl, with lively interest and sparkling eyes, "you, too, FrÓ Jordanus?"

"Yes," smiled the monk, "it is time that I saw a little more of the world. I do not suppose that they will pursue me, it is not to their advantage, either, to have a scandal. Come, Giulia, get us a little food, there's a good girl; just some bread and wine and cheese if you have it, and we will set out before the dawn."

The girl withdrew immediately behind the curtain; the idiot boy continued his rapping on the drum, but neither the priest nor the soldier took any more heed of him.

Gioan seated himself at the table. There he rested his elbows and sank his head in his hands.

"You see," he muttered, "she took no notice of my finger, she was not sorry for that at all." Then he added in a lower tone: "What I told you on the hill-side was a lie. I did not kill Silvestro because of anything he said about you, but because of Giulia."

"I knew."

"She liked him," complained the soldier, "they tormented me, both of them. After the puppet shows were over she used to make me give her some of the money, then she would go out on the hill-side to meet Silvestro."

"It is," said the monk serenely, "a beautiful place for lovers. There all would be sanctified—like a rite."

"But she would not go with me," continued Gioan bitterly, "because I am lame and spoiled. Yet sometimes she was kind to me too—just enough to madden me. And he was very insolent—yet I was fond of him. Can you explain it all, Felipe?"

"It was Nature working in all of you. Why were you so desirous for Giulia if she preferred another? There are many tall, sweet girls in Naples."

Gioan snuffed the coarse candle in front of him and continued in a low, rapid voice.

"Silvestro had no parents, they were taken away by the Turkish buccaneers two years ago when they raided the coast for slaves, and there will be no one to pay for Masses for him, unless Giulia—I wonder if she really loved him?"

"Loved, perhaps," replied the monk; "but she will not love a dead man long. Tell me, Gioan, it was not true that you heard Silvestro speak of me evilly—heresy, you said, and loose living?"

"Yes, I've heard that from him and others. I thought there had been many complaints about you, but you're not the only monk who errs, and I dare say no one notices much."

"It is quite true, that they complain of me, I have been aware of it for a long time. They leave me at liberty because they are watching me, and they wish me to commit myself. Since I do not wish to have either my body or my mind fettered I shall leave the Dominicans and leave Naples."

The soldier's uneasiness increased, he felt afraid for his brother. Surely it would be almost better to offend Felipe, the Lord of Naples, than to offend the Church. The Dominicans, too, who enjoyed the special favour of the King, who were so wealthy, who owned so much land! And was not their especial work the hunting out of heretics, so that they were named "Hounds of God"?

"What have you done?" he asked fearfully. "Oh, Felipe, what have you done?"

"The charges they have against me I am ignorant of, but I know that a conversation I had with one of our Order has been reported at head-quarters, it has been taken as a defence of heresy. I am a priest, Gioan, and answerable to the Provincial Father. If he should decide against me, I might find myself in prison. It has always been difficult for me," he added simply, "whatever monastery I have been in—Remember, Gioan, I was no more than fifteen years when I took the vow. Well, we will go, we will leave the kingdom of Naples and once we are in the Papal States we shall be free, at least, of Spain. What were you going to tell Giulia?" he asked rapidly. "Will you let her think you slew some stranger in a scuffle or a brawl—there is enough carrion left in the streets and on the hills every night to satisfy Hydra at his feast."

The girl entered again, and put the rough food on the table. Her movements were quick and anxious, and she glanced continually from the priest to the soldier. She had also brought a strip of linen and with eager rapid movements bound up Gioan's wounded finger.

As she performed this task, frowning in her earnestness, and while the priest ate his bread and drank his wine and water, Gioan gazed sullenly at the bright head bent above his hand. Then he burst out impulsively:

"It was Silvestro whom I killed, and because of you."

The girl began to cry, her face puckered, her eyes brimmed with tears, she bit her trembling lip as she continued to bind up the finger.

"You did not love him, then?" demanded the soldier, joyously.

Giulia would not answer. When she had tied up the finger she remained on her knees and hid her face in her hands, which were amber coloured and work roughened.

"Do not weep for him," said the priest, contemplating Giulia tenderly. "What was alive in him has passed into some other life, and what was beautiful in him has become some other beauty. Did you observe the stars tonight, how they flecked infinity with glory? We see them no longer, but they are not dead, but have passed into some other shape of splendour."

"That is heresy," said the soldier, in distress. "Silvestro is in purgatory and we must pay the Masses to shorten his torment."

The girl had dropped her hands and frowning, gazed earnestly at the priest, whose face seemed full of light even in the murky illumination of the guttering candle.

"Why are you leaving Naples?" she asked. "Are you really afraid of the Inquisitors? But we have not the Inquisition here, the people would never endure it."

"But I as a priest under Spanish jurisdiction am answerable to the Inquisition. I do not want to go to prison, Giulia, I feel restless and impatient, there is so much to see, so much to learn, so much also perhaps, to teach."

"You have read too many books," grumbled the soldier, gulping down the coarse thick wine and pulling at the crusts of black bread. "Even as a boy you were always reading with that old Augustinian, Teofilo. I think it would be better for you to stay here, Felipe, you know so much, whatever they were to say to you you would find an answer."

"That, perhaps," smiled the monk, "would be my chief fault in their eyes. No, I will go to Rome, where men's minds are alive. I will escape this tyranny and the tyranny of Spain which frets me to think of. What do you want to do, brother?" he added in another tone, with sudden tenderness.

"I would like to go back to Nola, to Cicala, we were happy there. That's true, isn't it?"

"Yes, we were happy, brother, because we were young and knew nothing."

But Gioan maintained obstinately:

"It is a beautiful place. Everyone who has ever been there says so. They call it 'the happy fields', don't they? Do you remember our little house, the marble pillars that supported the vine, and you said they came from a heathen temple? The marble hearthstone, too, and the pagan altar at the corner of the pigsty, and the other half-broken pillar to which the goat was tethered? Although it is not so far away it is much sweeter there than here. Do you remember the vintage, Felipe, and the festivals and games we had, and how joyous it all was?"

"I remember it, but we could not go back to it, Gioan, one never can. Oh, yes, I recall it very well. I remember hearing the cuckoo, I must have been a tiny child, I thought it was a spirit."

"You said you saw spirits once," interrupted the soldier, "on the hills, in the beech and laurel groves. It is true there were many ghosts there," he added moodily, as if to himself. "I remember once near that broken temple I saw them too. Then there was the place where the people who had died of the plague had been buried, far away from all the houses. I used to see them at nights sitting on their graves—when I was watching the charcoal burners of Monte Scarvacta coming home."

"It was as fair a place," smiled the priest, "as Araby, or the garden of the Hesperides. How glorious those violet hills, those plains of corn. Our mother is old and lives in our sister's house. Our father is at the wars and we never hear from him; it is quite likely that, old as he is, he will never return. And you and I have our lives to live."

He rose, smiling, and brushed the crumbs of bread from his white habit.

"Come, we must set out. They may soon discover the body of Silvestro—a brother will visit the cottage early—"

"I wish," lamented the soldier bitterly, "I had followed out my own ideas and not listened to you. I wanted to throw him on to the rocks, make it seem as if he had lost his foothold there and been drowned."

"If you had done that you would have been grieved about it afterwards. It is better that he should be found by the brothers and given a Christian burial. It is better not to conceal what one does and to be fearless."

Giulia rose to her knees, the tears had dried in delicate stains on her smooth face.

"I think you are that—fearless," she said directly to the monk.

"It is only," he replied, looking steadily at her, "that I have never yet met or heard of anything that inspires fear."

"That is strange," mused the girl. "The world, has seemed to me sad and dreadful ever since I looked on it! Every day there is murder, cheating, and punishment! Nobody has any pleasure or ease because we must pay taxes to the King of Spain, to root after heretics in a distant country we know nothing about, and the heathens raid our coasts and carry our people away to be slaves." She glanced bitterly at the soldier. "And that which one loves is slain out of jealousy, and still you say, FrÓ Jordanus, that there is nothing to fear!"

"For you, yes, I understand, Giulia, the world is indeed full of misery and terror."

"And then," continued the girl, cutting up what was left of the bread and soaking it in the lees of the wine in the cup, "when one is dead there is no happiness, for if one has, in one's weakness or ignorance, sinned, one is punished to eternity."

"That is not true," said the monk, and the girl paused with the sop in her hand; and Gioan called out in terror:

"That is heresy again! You must not speak so!"

"But I," smiled Giulia, softly, "like to hear it. I like to think that there is no Hell, no matter what the priests say."

She took the sop in a saucer to the boy and set them down beside him; he began to eat greedily, using his mouth like a dog.

"He feeds like that because his teeth are rotten," remarked the girl. "If you give him hard food he only licks it."

"Where does he come from?" asked the monk. "Is there anybody to whom he belongs?"

"No one at all. We found him in the street. One cannot understand very well what he says, but I think he meant to tell us that his mother died of the plague. One can see that he is but a poor idiot who can do nothing but beat the drum."

"He must come with us," said the priest.

The soldier sullenly protested; he was turning over the few rags that were hid behind the puppets and the boxes at the back of the room. He hoped to find a few garments that would be useful to him on his travels, which appeared in his thoughts as so desperate and hopeless. He had no money, no trade, and no relatives, save those who were very distant or as poor as himself.

"Will you take me also?" asked Giulia. "I would look after the boy for you, he is fond of me."

The soldier, clasping a pair of leather shoes to his breast, cried out in an ecstasy.

"Oh, Giulia, you would come with us after all, after I have slain Silvestro?"

"Yes, I will come with you," replied the girl, but she looked at the monk, not at his brother. "You know very well," she added, "what I shall become if I remain in Naples. If there is no longer to be a puppet show where can I earn a few shillings? Gioan was good to me, where shall I find such another?"

"You are very intelligent, Giulia," smiled the monk, "I noticed that when I first met you. How long have I known you now? Five years, since you were a very little maiden. Yes, you may come with us since you have nothing to leave behind of any value. Perhaps we might find work for you somewhere on the way, I know that you are quick and clean and willing."

He paused, and seemed to reflect deeply, the girl's bright glance on him the while. Then he said:

"Would you like to marry Gioan and go with him to Cicala where perhaps, after all, our mother might find something for you both to do? Gioan might work on a farm, or with the charcoal burners; he might even take again a little cottage that we had. I have a friend there who perhaps might do something for you if I wrote to him—Giovanni, the sculptor, or Leone, the scholar."

Giulia shook her head.

"I couldn't marry Gioan." Then she added: "I did not love Silvestro either, it was only that he was young and loved me and it was very sweet on the hill-side."

"I understand," said FrÓ Jordanus. "Put together, then, anything that you may wish to bring with you and come with us."

The early morning was so beautiful that the spirits of all the four travellers were raised. The vast upper air was quivering in an ecstasy of light, the stately violet hills seemed luminous, the upspringing beeches, cypresses, ilex and pine quivered with a vibrant life and every little flower and grass along the wayside was edged with gold.

They had avoided the highways and had taken a winding path through the vineyards so well known to all of them. The minute green flowers of the grapes were budding among the closely curled tendrils; on the ilex trees the small, pale, tender leaves showed against the dry, rusty foliage of last year. The cushat dove was cooing in the silver branches of the beech trees, which were hidden by rosy golden leaves.

When they left the vineyards they crossed by an arched stone bridge over a small stream where the clear water flowed swiftly over round, smooth pebbles.

Giulia, who was leading the boy, leaned for a moment against the bridge and the monk watched her. She reminded him of those little figures on the coins that his father used to find in the fields outside Nola when digging, or on those that he had seen the men turn up with the plough in the furrows round Cicala—the figures of women in straight robes, profiles of women on coins, busts of women with heavy knots of hair on the napes of the slender necks, with straight features and large eyes. The waif of the Naples' slums, although she knew it not, was direct heiress of that ancient and vanished race of Grecia Magna to which he, the Nolan, felt so akin in thought and interests; he felt tenderly towards her because she was formed from that ancient time, because she gave shape and colour to many deep, sweet dreams that had come to him leaning against the broken altars of Cicala.

They journeyed on steadily through the lovely serenity of the spring tide, presently leaving the fields and taking the high road towards Benevento and the frontiers of the Papal States.

The child, with his drum on his back, seemed happy, and the girl and priest were in equable moods, but Gioan, the soldier, was uneasy and depressed. He was homesick for Naples, and the puppet show where he had made a pleasant livelihood, he lamented this and his earlier days when he had served under Prince Juan in Flanders. He longed for the gaiety, the obscenity, the music and the odour of the city.

Though he had been in so many confusions of blood and violence, had done many wicked deeds and seen them done by others, so that they became but a daily matter of course to him, he was much troubled by the death of Silvestro, whom he had killed in the dark on the warm, sweet hill-side under the falling stars. As if to comfort himself he muttered over many of the horrible recollections of what he had beheld at the siege of Antwerp, and yet it was clear that none of this was very real to him, while the murder of Silvestro kept much in his mind.

He, with his lameness and low spirits, and the boy, with his feeble steps, hampered the other two, who could have walked boldly and freely in their health and strength. But, as they had no longer any fear of pursuit once they had cleared the confines of the city, and as there was no object in their travels except to be free of tyranny and to see the world, it did not irk any of them to travel slowly.

They lived on very little; the priest begged at farms and wayside houses and was never refused water or a slice of bread or a bowl of soup with dried peas and perhaps meat in it, a piece of cheese or a few eggs. Other food they procured themselves; Gioan made himself a rod and line and hook from a few trifles he had in his bundle and caught fish in the clear flowing streams which often passed the highway. There were wild sallets and acrid wild roots, very young and soft, which they ate too.

It would have been quite easy for them to have obtained shelter in some barn, or even in a farmhouse kitchen, but they always preferred the open air. The girl would lie down with the boy, and the two men close together, and all would sleep soundly.

But on the third night the priest did not sleep; he remained watchful long after the other three were silent. And then, when he believed that they were no longer conscious of his actions, he rose and turned back the ragged cloak in which his brother was wrapped. Gioan slept, but not peacefully, he muttered and tossed and the sweat glistened on his brow. The moon was high overhead and so strong that the sky seemed like a globe of solid silver; this radiance concealed all the stars, the heavens seemed barren.

The priest very gently loosened the soiled sleeve round his brother's arm, which was swollen and hot to the touch. Even in that light he could see the dull purple flush that ran up from his injured finger.

A shadow fell over the torso of the sleeping man and on the monk's own fine, pitying hands. He glanced up, Giulia stood beside him; she seemed clothed in silver, so did the moonlight transform her rags.

"He is ill, your brother," she whispered, "I noticed it today. He has a fever, I think."

"Yes, he is becoming worse, too, and there is nothing we can do. Indeed, I think there is nothing that a doctor could do."

"He will die?"

"I begged a little vinegar at that last farm we stopped at, they gave it me in return for a blessing. If you have any rags and linen left bring those, we will soak them in vinegar to put on his lips and forehead."

The girl obeyed. Together, and in silence, in that vivid glow of the moon, they tended the sick, unconscious man whose wound was slowly poisoning his blood. Then, together, they watched, one either side, the monk in his white habit which seemed under the moon to be of an unearthly hue, and the girl in her ragged stained clothes, the bodice laced tightly over her slender bosom. A little way off, under a tall solitary tree, the boy slept. Now and then the monk turned his head to look at him; in this light he was beautiful, his malformation and his disease were eclipsed by the universal radiance—a lovely, sleeping child who seemed happy, too.

The monk began to talk to Giulia to comfort her. He told her, in his rich and beautiful voice which he kept very low so as not to wake Gioan to more pain, some of the pleasant things that he could remember—his own childhood and his great felicity as a youth underneath the walls of the very ancient ruined city of Nola, which he still loved so greatly. Though his parents had been so poor when he was born they had been of gentle birth, a branch of a noble family at Asti, and there had been a famous poet by the name of Tansillo, who had made visits to the town and who had—he, Felipe, knew not how—been a friend of his father. He could remember him, a smooth, elegant man, and the verses he would recite, and the stories he would tell of that ancient world which lay, as it were, beneath their feet. He had known Ariosto and Tarso and been patronized by the Spanish Viceroy, Don Pedro de Toledo.

"They were civilized, tolerant, and free, those Greeks, Giulia. Often have I held in my hand a little image of a gracious woman or a noble man, with wise eyes. You could pick them up in the furrows, or when you dug in the garden your spade would clink on them. When I was older I read in Greek and Latin the books written by those people—" he broke off. "You are like them. Did you ever know from what part of Italy you came, Giulia?"

She shook her head. Like Silvestro and the poor little boy, like everyone in that slum of Naples where the puppet theatre was, she knew not what her origin might be. She was a stray creature, a castaway. She could remember being in service with an old woman who was kind to her, and then serving in a vegetable shop, where she was beaten; and then being employed as a goatherd.

"That is when I remember you first, Giulia," interrupted the monk. "I saw you coming out of the wood on the hill-side. I lifted my eyes from the great book I had and you were there. My memory awoke as from a dream—what woman was this? Surely she died long ago?"

"That was when Gioan met me, on the hill-side, when he came up to see you, and so I got work in the puppet show, but I am sorry that all that has come to an end."

They gazed down at the sick man; they were used to bloody death and gross violence, to riot and murder and robbery, they had been born and bred in a country that was sunk beneath a foreign tyranny and was crushed beneath a ruinous taxation. The girl thought of all this cruelty and misery, she found a great comfort in the strong, serene face of the monk; his eyes seemed not to be those of an earthly creature, she thought.

"Why did you become a priest?" she asked, timidly, regretfully.

"Because I love learning, Giulia."

"You should have been a soldier, you are so strong. Gioan told me how you carried Silvestro over the hills to the gardener's cottage, quite easily."

"Gioan helped, and Silvestro was not heavy. I detest war and cruelty—the devices of little men."

The girl asked candidly:

"Have you kept your vows? Is what they say of you true?"

"Where have you heard people talk of me, Giulia?" replied the monk, unperturbed.

"Oh, Gioan told me, Silvestro too. One hears these tales—"

"I have broken no vows," smiled the monk, "save those that no man could make and few men keep."

"I never saw you on the hill-side. Whom did you meet there? Is it true that you write verses?" She spoke without jealousy or curiosity, only with a candid desire to be enlightened.

"See the moon," said her companion. "Diana—truth and wisdom, so lustrous, so benign. She is the lady of my first love—the modest daughter of the Emperor of the Universe—a lonely nymph whom I have woo'd on the golden fields of Nola—name her Philosophy—"

Giulia understood nothing of this, but his voice was so beautiful that she listened, rapt.

"The world is ruined by barbarians. Consider this scene and think of all the misery you have beheld in seventeen years. Consider the beauty of Italy and the men who rule this brilliant earth, whose banners pollute the luminous air. Why am I a monk? Where could I turn for peace? Pest, robbery, the monstrous tyranny of Spain—I recall, when I was a boy I heard of the massacres in Calabria, the heretics who had fled from Piedmont, eighty-eight had their throats cut with one knife—"

"I wish," said Giulia, "that the moon would never set. How warm it is, how still! We do not know that we are poor or pursued—no one mocks us or reminds us of our sins."

"It is like an indrawn breath—all in abeyance. But the sun will rise and life go on."

"Are you not afraid?"

"There is a yoke of fire lighter than air—he who wears it is raised above all things, even above liberty."

"But the Inquisition—"

The girl crouched on the sweet grass and tried to find comfort in the lustre of the moon, but a monstrous figure seemed to blot out that radiance, the shape of the grim Spaniard, Saint Dominic, in his gloomy robes with his fierce dog by his side and his lean hands stained by the blood of heretics; his saturnine visage was in the shadow of his hood—"Persecutor of the Heretics," "the Sword of the Lord" in Toulouse, Captain of the Bodyguard of the Inquisition—domini canes.

"I think of Saint Dominic," sighed Giulia, shivering together as if she strove to protect her heart.

"He was but a man, and no very enlightened one. Make no idol of such, child."

She looked at him eagerly; though he sat so still he seemed the very personification of ardour and energy. So vibrant with life was he in his immobility that she felt comforted as by the presence of something vital and everlasting. The coarse robe clothed him as the cloud clothes the mountain, his feet, beautifully shaped in the thongs of the sandals, seemed as firmly part of the earth as were the trees springing from the warm mould full of seeds and roots.

About him and the girl crouching beside him and the smooth rock on which they sat, the moon cast a pool of deep violet shadow. None of the lines of fatigue and thought were visible in the monk's face; his features were clearly defined, the fine, straight nose, the large wide-set eyes, the fully-curved, tightly set together lips, the rounded chin. His face was like the intaglio on an ancient gem that he had once picked up near the old burial-place (where they had found the urns) outside Nola. When he had washed the jewel it had shone yellow in his hand-a fiery fragment in the setting sun—a portrait of himself cut by a hand long since one with the dust of the lovely landscape.

Patiently, and at peace, they waited, watching the sleep of the sick man.

When Gioan awoke he was in a delirium, and they carried him to the shade of the tree where the boy had slept—a gracious tree full of young green leaves and rousing birds. There was a stream not far away and they took it in turn to watch by him and fetch him water in the little wooden bowl that Giulia had brought. He became hideous, purple faced, swollen, with turgid lips, and much afraid.

The boy, who was quite happy, brought out his drum and rapped softly the little march that opened the puppet show, as if he thought it would comfort his master. Gioan knew nothing of this or anything, and at Giulia's request his brother gave him absolution, and when the evening came again, he died, holding Giulia's hands and crying pitifully to his God for mercy. The child laughed, listening to his drum; the sun was so strong that the water began to dry in the cup as they fetched it.

They were a long way from a town and they had no means of burying the dead man, nor of carrying him to a church or to a burial ground. They waited and hailed one or two passers-by, who only rode the faster when they glimpsed a corpse.

So in the evening they covered him with boughs broken off the beech tree, which the little boy climbed up to get for them, and went on their way towards Benevento.

That night they stayed their journey under the walls of a ruined house which was tufted with wallflowers and brown and cinnamon hued pale grasses. The girl fed the boy with the food they had begged during the day. Neither of them could eat, and Giulia could not sleep for thinking of the two dead men. She believed that their ghosts would come wavering towards them in the moonlight, which cut the desolate house into fantastic shapes.

The monk told her that she need not be fearful, for she would see no phantoms.

"You yourself, FrÓ Jordanus, have said that you saw spirits in the groves outside Nola."

"But they were not spirits who had ever been men, Giulia. If you cannot sleep and are frightened, I will tell you a tale."

She nodded her head meekly, and he spoke to her of a book he had written which was named Noah's Ark, and which he had dedicated to His Beatitude Pius V, and presented to him when the Dominicans had taken him to Rome in a coach.

The monk told Giulia how all the animals in the Ark strove for the most splendid seat, which was in the poop, and that in the end he who claimed it was the ass. Then he broke off in the middle of his tale, which he told with laughter and many gestures, and asked the girl why she had come with him on this tedious journey.

"Was it because you loved Gioan? You have not wept for him very much."

"No. It was because I loved you."

"You know that I am a priest and you know what is forbidden to me."

"Yes, but you said yourself there are some vows that a man cannot keep. Besides, what does it matter? I am happy."

Her candour was as complete and pure as his own. She moved away from him and sat down by the sleeping child, who lay on Gioan's cloak with his drum beside him. The monk walked into the silver night, he heard the girl's voice, thin and faint, coming after him through the absolute stillness.

"You will not forsake me?"

"No, Giulia, I shall return."

He walked along the edge of fields where the young corn was sprouting, the whole earth vibrated with the putting forth of leaf and blossom and the promise of fruit.

The monk felt relieved, happy, in harmony with everything. He looked back at the ruined house, tufted with flowers, at the girl and the child by the silent drum, reposing on the dead man's cloak.

In sweet loneliness the solitary man essayed to review his life which had been suddenly and strangely broken. He was thirty years old, sixteen years a monk, six years a priest. He had always found the world of an exceeding beauty and men of an extreme meanness, ignoble creatures on a noble earth.

He himself had more learning than any scholar he had met. Compared to himself the Prior Ambrogio Pasqua, Vice-Chancellor of the College of Theology, before whom he had made his final vows, was ignorant. Many of his fellows in the great Spanish Order, these "Hounds of God," trained to hunt out heresy as pigs hunt out truffles, were wrapped in superstition, stupid, and dark-minded. Even the splendid Cardinal Rebiba, who had commanded him to come from Naples that he might be presented to the Pope, had not been a man of much erudition, while he, the poor youth from the mean hamlet, outside the broken walls of Nola, had found time for so much reading that he seemed to have done, already, with material learning.

He was as familiar with Spanish as with his native Neapolitan, and the cultured Italian that the great poets, Dante, Ariosto, and Tasso wrote. He could command Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, he had accepted and digested the orthodox education that had been put before him, the study of Aristotle, of Albertus Magnus, and of the great Saint Thomas Aquinas, the angelic doctor, himself the most powerful and famous of all the Dominicans.

But these thinkers were not to him as great as their predecessors, the philosophers of Greece and Arabia, whose writings he had studied in the libraries of the monasteries of the Order of Saint Dominic. So much learning, so much musing, and for what end? The monk stood motionless in the moonlight and clasped his hands tightly together.

For several years he had known that a man who was fearless and candid, whose mind thirsted for knowledge, and whose soul quested for truth, could not live in a convent; even while the other monks praised his learning and seemed proud of his brilliancy and gave him much liberty and independence.

The moment had come when his brother's crime had set him suddenly and violently free—and for what end? He thought of the man whose example had most stimulated him—the Franciscan mystic, Raymond Lull.

He thought of the Cardinal, Cusanus, Roberto of Cusa, the friend of Aeneas Silvius. Raymond Lull had been dead nearly three hundred years, and Cusanus a hundred years, yet the monk thought of them as friends. They seemed to be with him now, modest, simple, but with eyes like jewels.

He sat down on a stone silvered by the moonlight and touched it lovingly with his strong hands. He was happy in his body and in his mind. "God is incomprehensible, and in all."

He remembered the two wounded pigeons that a poor man had sold him for food, and how he had cherished them and given them back to liberty. He recalled the lovely moment when he had set them free and they had flown out in the dark and the noise of their wings had been one with the noise of the leaves of the ilex trees, an act which had made him forget the squalid sadness of the dead man lying on the pallet bed with the murderer kneeling shivering and forlorn. He mused on the exceeding grandeur of the shooting stars, like sparkles of light shaken from the beams on God's forehead, and that reconciled him to the memory of his brother's body, malformed through wounds received in senseless, bloody wars, of his corpse dead from a hurt inflicted by the man whom he had murdered, lying under the fresh boughs of the green tree drowsy with birds, that the idiot boy had plucked so gladly.

He threw back his cowl and shook aside the long dark hair that fell on his forehead. What to do now? What should be the life for a man like himself? He belonged to the Church, he owed the Church much—his education, his learning, the peace and security in which he had pursued his studies, and the Church enshrined magnificent truth. She was necessary as a safeguard and a symbol; she required wise, strong men to purge her of error and corruption—that would, that must be done. He loved her, too, her grave and splendid ceremonies, her high mystic doctrines of the famous saints and doctors.

He remembered Rome, so superb and mighty, with pleasure and gratitude. Even the superstitions of the Church were useful, nay, were necessary to little people, to humble, sorrowful people. He was not a heretic, only the very ignorant or spiteful or malicious would name him that, he had but demanded the right to independent thought, the liberty to unleash his mind on the long quest of truth.

He told himself that there must be his intellectual peers in Italy, even if he had not found them in Naples. The thoughts that inspired him, troubled him, and drove him onwards, could not be his alone. Other men had them before him, men who were long since dead, the essence of whose spirits had been perhaps in those falling stars that had darted into the Bay of Naples, that had lifted the lilac and blue pinions of the two wounded pigeons he had released from the gardener's cottage.

He put his head into his hands and considered the beauty and pleasure and pride of the world. He was young, strong, and healthy; he remembered the orgies in the ripe fields at Cicala. The Spanish masters of the ancient people to whom he belonged, people descended from Greeks, Etruscans, and Moors, had been scandalized and alarmed. They had sent soldiers to prevent the peasants from holding their great festivals at the gathering of the corn and the plucking of the vine.

"Bacchus and Ceres," smiled the monk, "whom they worship in their own way on their own alters."

He remembered his native city with great love; it was now a miserable ruined place lying crushed under the heavy laws of a foreign tyrant. But it had been superb and gorgeous, with twelve gates and a great amphitheatre—a great city of Grecia Magna.

He pondered, but without discontent, how different and how much easier his destiny might have been if he had been born rich—a prince, perhaps, or a great lord. Then he would not have needed to have become a monk in order to obtain learning, to have spent so many years of his youth in a monastery. He could have travelled with dignity and in state, he could, perhaps, have moved the destinies of people, he might have done something to smooth out the bloody confusion in which mankind writhed.

But his father had been a poor mercenary soldier and he had not one penny.

This consideration of his poverty brought to his mind Giulia and the witless boy—one of them loved him and both were, in a way, depending upon him and had trusted him, but he could do nothing for them. He turned back the sleeves of his white habit and locked at his lean wrists. Where, anywhere, in all the world, as he knew it, would life be possible to such a man as he knew himself to be? He felt the scapulary on his breast, he thought of Saint Dominic, dark-faced, in his funereal robes with his lean dog, nosing through the lazy sloth of the night.

Beneath the walls of Benevento they came upon a travelling puppet show. A fat woman with a baby at her bare brown breast was sitting at the door of the wagon mending the green petticoat of a limp doll with tow stitched to its head. Some men were watering a white horse at a stream, two dwarfs were cooking a meal over some charcoal.

"You will go with these people, Giulia," said the monk, "you and the child."

He approached the woman and told her that these were two orphans who were in his charge, and begged her, in the name of God, to take them with her on her journey.

"The girl is clever at working the puppets and saying the voices for the women dolls, and the boy can play the drum. They eat very little and can earn their keep."

The woman stared at the face of the priest and was frightened; she thought at first that he was a saint or an angel.

"The high road from Naples to Rome is full of robbers," added the priest, "and I cannot protect these two. There are many of you and you will be safer."

"Do you go to Rome?" asked Giulia of the woman, who nodded. She was a Neapolitan and greatly frightened of the Spaniard, the priest, and the Dominican.

"I shall see you in Rome," said the monk. "Be kind to these two for your own sake and the love of Our Lady."

The boy sat down on the edge of the woman's skirt and began to beat the little drum. This pleased the baby, who laughed and danced in his mother's arms. The woman smiled, timidly; only Giulia looked sad, like a child whose candid happiness is suddenly taken from it; her mouth moved, trying to shape words that she could not utter.

"We shall stay at the Field of Flowers," said the woman. "We do quite well there. We have acrobats and clowns as well as the dolls."

"The Field of Flowers," repeated the monk, "I do not know the quarter, but I shall find it—"

"It is a square near the river."

The woman rose and placed her laughing baby in Giulia's arms; she had been a rope walker and still retained an alert and wary grace and seemed to place her feet with caution on the grass. She asked the monk if he would share their meal, but he refused, disliking delay. The stroller's baby pulled at Giulia's kerchief and the heavy tresses tumbled to her waist; the monk, smiling at her with his eyes, admired her without desire. He hoped that she would find another lover, one who would be kind to her and make her laugh joyfully.

The dwarfs came close to listen to the child's drumming; they were bow-legged and their mouths had been slit in order to make them grotesque, one had a ginger beard and other was bald with scarred cheeks.

The monk gave them all his blessing and went his way by the walls of Benevento. He had no cause for gladness, but some pulse of his inner being beat in harmony with the universe, with the eternal rhythm of infinity. This gave him a sense of excitement, of enthusiasm that made him walk swiftly.

For a long way he could hear the beat of the child's drum coming faintly and unevenly on the slothful air.

Towards Rome—a long journey. The dusty, uneven road unrolled before him; an almond tree, a church, a farm, a village would be specks before him, then large, taking shape, colour, then close, filling the evening, then behind him again, only to be seen by a backward glance, then lost.

With the evening came a greenish light, pale as the radiance in a lily cup; the monk rested in a solitary place where he could see nothing but the outline of the darkening hill-side against the translucent sky. A little waterbreak, falling from level to level nearby made a hastening sound—an urgent, yet soothing melody. A small tree was outlined, every delicate bough and quivering leaf, against the dazzling purity of the heavens.

The monk spoke to himself: "What are you doing here, Felipe Bruno? Where are you going?"

He mused, his thin face in his fine, hairy hands, the soiled monk's habit hanging heavily on his firm limbs that seemed active even in complete repose.

Into his happy solitude a stranger passed; a tall man walking with an air of strong purpose over the brow of the hill under the dancing leaves of the slender tree, a black figure in an ample cloak thrown darkly against the bright void of the sky. As the monk glanced at him he passed on, looking straight ahead; there was a gaunt dog at his heels.

WHEN the monk entered Rome he was very tired and even a little giddy from long journeying, but the sight of the beautiful, superb city whose very name was like the sound of trumpets, upheld his strength.

It was early in the day and he wandered slowly through the sunny streets until he came to a large fountain and there sat down and refreshed himself, when he had drunk allowing the water to run through his lean, brown hands, which were covered with dust. Already a strong heat crept into the air, the pale buildings, the colour of ochre, of sand, of amber, and of the earth of Sienna, began to dazzle as if they also gave out light.

The narrowed eyes of the monk peered out under his dusty black hood; he could remember the city, but not well, he had only been there once before and not for long, but he could recall the Dominican monastery, the head-quarters of that Order which stood in the great Piazza of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva. He recalled the pleasure he had had in the ruined temple opposite, still, even in decay and neglect, a worthy dwelling-house for the gods.

The sky overhead strengthened into a violent blue, shadows under the balconies, in the deep doorways and window-place became clear-cut and violet in colour; the monk noticed some antique cornices, the full flow of acanthus leaves, the half-defaced mask of a satyr or a nymph built into the walls of the Christian dwellings. He noted also in the gardens, the strong fronds of the plants, the palms and vines, the rose briars and wall-flowers full of sap and rearing proudly to the rising sun.

He lingered by the fountain for he was footsore and he liked to hear the splash of the water falling from the grinning jaws of the marble fish, he liked to watch the ripples spread and break on the curved, discoloured lip of stone, he liked to watch the drips of water fall on the hot paving stones.

Presently children came by and paused to drink and smile at him shyly before they ran away. The monk pondered his future, to which he was really indifferent. Probably it would be safe for him to go to the head-quarters of his Order—wandering monks were common enough, the Dominicans in particular were often sent on the road, sometimes in a secular disguise, to spy out heresy, to observe the world, to take news from one convent to another—it was not likely that any ill report of him had been received from Naples. There had, indeed, been scarcely time, for he, though on foot, had travelled swiftly, often walking through the sweet spring night being content with but an hour or so of sleep. Besides, there had been no definite charge against him put before the Provincial Father.

He recalled curiously as if it were a picture detached from his own experience, the room in the gardener's cottage as he had last seen it, with the dead man on the bed. When that poor corpse was discovered they would see that he had done his best to succour body and soul, whatever they thought of him they would scarcely blame him for that crime nor would they be likely to connect his brother with the murder. Yet, he did not know. He thought of the flight from the puppet show. All gone, and there would be those who knew that Silvestro and Gioan had been both enamoured of Giulia, who pulled the strings and said the words for the female dolls.

The monk rose; none of these things mattered since both the men were dead, and Giulia, as far as he knew, safe enough. With his long easy stride, a little slow by reason of his fatigue, he turned through the noble streets in which it gave him such pleasure to walk, and asked the way from the first man he met—a peasant from the Campagna who was bring fresh vegetables into the city.

The man did not understand him at first because of his Neapolitan accent, but soon guessed from his habit where he was going and eagerly gave him the direction.

The vibrant light was increasing brilliantly over the mighty city, and on every window sill and in every dark plot buds and leaves were uncurling to the gracious heat.

The monk was received without question in the great monastery facing the temple of Agrippa. Clearly, the brothers had had no news from Naples and observed nothing suspicious in the journeyings of FrÓ, Jordanus to Rome. They knew his reputation as a magnificent scholar and treated him with courtesy and respect.

The wanderer was glad of the shadowed cell, the sun-flecked cloisters, the plain food and regular hours, and the large, handsomely appointed library, glad, even, to find himself again one of those black and white-robed figures whose days were given to meditation and prayer. With no sense of hypocrisy he assisted at the divine services in the gorgeous chapel, the ceremonies and observances of a monastic life had become woven into the fibres of his being. He approved of these great organizations, so skilfully managed, so wealthy, and so powerful that strove in a world of blood and chaos, of lust and greed, to maintain philosophy, religion, and a contemplative life, and he mused that if the Dominicans would purge themselves of ignorance and bigotry and allow the minds of their brethren to remain unfettered, he would ask no better than to pass his days as one of them.

But he was irked to find that so many of the richly bound books in the sumptuous library were out of date, traditional, a mere collection of words turning over superstitions, half-truths and lies. And he was vexed by the continuous talk among his brethren of heresy, of the duty of hunting out errors, of the obligations on every priest to accept without a shade of question the tenets laid down by his superiors.

The Prior, who was a Spaniard of haughty birth, and some of the brothers also, was disappointed in FrÓ Jordanus because he did not show much zest and zeal on the question of heresy, but seemed to keep his lips guarded; they mistrusted his eyes, too, which were so full of fire and had a look, they thought, of unaccountable and unwarrantable boldness.

The monk went much abroad, walking the city swiftly, observing everything, from the insects in the cracks of the hot paving stones, to the glitter on the unfinished dome of Saint Peter's Church. Rome was full of activity, on every hand men were labouring and hastening to and fro on arduous work. Huge, formidable fortresses, three or four hundred years old rose beside the gorgeous columns and broken, ornate arches left from the Rome of the Imperial Caesars. Elegant basilicas leaned against the yellowing marble of ancient temples, goats browsed above the capitals of buried pillars, living plants grew next the sculptured vines and acanthus leaves rigid in cracked alabaster.

Eager, gesticulating workmen urged on by earnest overseers were building hospitals, libraries, and spanning the yellow, turgid waters of the Tiber with a new bridge. Palaces raised by men intoxicated by the splendour of their own genius rose triumphantly to the stainless sky.

For the last hundred and fifty years Pope after Pope had striven with a feverish ardour and an unflagging energy to embellish the resplendent city which had been for so long the capital of paganism and the mistress of the world.

Slums and mean, half-dismantled houses jostled by the new, vigorous buildings; beggars, many of them broken and mutilated soldiers, clustered on the shallow steps of the gilded churches and in the shade of the high balconies of the proud palaces. None of the streets was safe after dark, for the country beyond the walls of Rome swarmed with brigands and robbers. Filth, disease, and ignorance were side by side with the sublime aspirations of the human spirit expressed in marble, in stone, in gilding, in mosaics, in wide avenues, in strong, elegant bridges.

FrÓ Jordanus often paused to gaze with his brilliant, restless eyes at the walls of the Vatican, where the great new library, erected to house the collection of priceless books and manuscripts collected by the Popes, was nearing completion. The monk knew the names of several books that were not among those cherished treasures. He mused, smiling, on the Pope, head of Christendom, the Viceroy of God on earth, and the incompetent governor of these tumultuous, badly managed, half-ruined Papal States—an ascetic old man fiercely declaiming against heresy, favouring those fierce soldiers of Christ, the Jesuits, who through the Collegium Romanum were making themselves the masters of education in Rome. Unnoticed, merely another monk in a city crowded by monks, the Dominican went his way observing everything.

The monk found, in the ugly slum inhabited by outcasts, the puppet show that he had seen outside the walls of Benevento. The little theatre had been arranged upon an open space of ground in the Campi dei Flori near a wall which had once been part of a patrician's house. The back and one side of the little theatre was formed by an angle of the ancient yellow and cracked marble walls, with, above, a slightly hollowed niche, in which was the smooth features of a defaced mask crowned by vines. The roof and the other side of the theatre was formed by a tattered awning of orange canvas.

The simple-minded boy whom the monk had brought with him from Naples was seated by his drum, but he was not playing it. He seemed healthier, his dirty face was plump, and he laughed at the dark-eyed baby tied in the shawl that lay on the ground beside him, and whom he was teasing with a bunch of weeds that had quickly wilted in the heat.

Near the shattered fragments of a fluted column sat Giulia; she was threading scarlet beads on a blue string and her smooth long face seemed as empty as the mask carved on the wall. Strong yellow sunlight came from under the coarse awning and glowed on her bare neck, and the glimpse of bosom that showed between the lacings of the ragged bodice.

With his long, yet elegant strides, the monk came over the broken alabaster flagstones through which the luxuriant weeds were sprouting.

She looked up at him when his shadow touched her feet and smiled as if she had been expecting him. There was singing, the voices of boys and men, coming from a basilica nearby. The sound, floating through the narrow windows on the warm air, sounded harsh and unnatural in contrast to the voluptuous sweetness of the day.

"Did you come to look for me?" asked Giulia.

"No," replied the monk, "I found you by chance. But I meant to come."

Giulia let the beads fall into the lap of her ragged skirt, her bare brown feet were clearly defined by a line of purple shadow on the yellowish broken alabaster of the pavement.

The monk asked her if she was happy, and she shook her head.

No. The wife of the puppet master had taken a fancy to the boy for she had lately lost a child of her own who would have been of about that age. She was kind to him, almost foolish with him and he had become pampered and sly, but for herself she was often ignored and often beaten. Several times they had told her that she must leave. She had feared, during that long and dangerous journey from Benevento to Rome, that the wagon would go on in the morning and leave her behind, a prey to all the robbers and evil men who prowled on the highway.

As she told him this she revealed, by her rapid words, by her quick looks, that she was neither resigned nor bitter, there was something gentle and noble in her sad expression.

The monk was helpless to offer advice or help, and she was but one of so many. He thought of the markets as he saw them on his early morning walks, of delicate, lovely, slaughtered birds and animals who had been a few hours before free and joyous and now lay in mangled, bloody piles, sometimes still faintly breathing. Giulia was like that, but one of many fair and helpless creatures who every day were ruthlessly destroyed without anyone feeling regret or remorse.

"This is the life I was born to," continued the girl, smiling, "therefore I ought to be contented. But you know, FrÓ Jordanus, I am not. I often think of those who live delicately and comfortably, I see them in the streets of Rome—ladies, like peacocks, with gold dust in their hair."

"Do not envy them, Giulia, they are no more happy than you are."

"You say that to comfort me, but it is not true. Besides, if I were in such a position, I should not be idle and vain and stupid—" She broke off quickly. "But you! What are you doing? I see you still wear your habit." She spoke half in awe, half in tenderness—he had always known that she was afraid of his robe.

He told her he lodged in the Dominican monastery, that no one had questioned him. They were silent a while, watching the poor, harmless boy and the fat baby who played together on the cracked alabaster through which the weeds sprouted. Resonant and robust the harsh undertone of the song of adoration to God rose from the gilt frames of the windows of the nearby basilica.

"It is difficult," said the monk, "to build up one's life from nothing. We neither of us have anything, Giulia—I, a monk, and you, a vagrant. If we had been left, now, even a little money—"

"But you have so much," she urged, her voice sounded weary and depressed, "your learning, all those books that you have read."

He gave her his vivid, disturbing glance from under his hood.

"I have a great deal of learning, Giulia, yet not as much as I should wish. But I doubt if I were once free of this habit it would suffice to earn me my bread—"

"Nor even to give you happiness?" she asked him. "Your habit—could you not leave that as some do? I have seen them dressed like ordinary men. Could we go away together, somewhere, anywhere? Who would notice or care?"

He smiled at her candour, which so suited his own character. It was also impossible for him to conceal any thought or mood, any impulse or aspiration, save only by that clumsy expedient which he used now in the Dominican monastery—closed lips and downcast eyes, which at once provoked comment and suspicion.

"You and I, Giulia! Neither of us is clever enough for an adventure like that. Besides—"

She interrupted him by rising and coming from without the hot shadow of the orange awning.

"You don't want me," she said decidedly. "Very well."

She turned into the tent and began with feverish vigour to set ready the puppets for the evening performance—all the strings and the lead weights had to be put in order, all the dresses to be brushed and smoothed.

When the monk returned to the monastery another brother with whom he had a little acquaintance and who had been friendly, stopped him in the doorway with an urgent hand on his sleeve.

"I have been waiting for you—do not go in. Come, let us walk up the square a little way as if we were in ordinary converse."

FrÓ Jordanus obeyed. He was astonished at the interest this stranger took in him, he had hardly noticed the man, who was young and plump and who read much in the library and ate heartily in the refectory.

"There has come news from Naples," muttered the young monk, looking steadily down at the hot flagstones. "They say that there was found in the gardener's cottage that you had left, a man who had been slain violently." He looked up quickly, sideways. "That, of course, was nothing. It was supposed to have been some poor wretch whom you had taken in to succour, but they found a book torn across and thrust into a bed of manure. It was a forbidden book," added the young monk, emphatically, without raising his eyes.

"I know," replied the other with complete frankness, "it was some of the works of Saint Jerome, annotated by Erasmus. I knew that they were forbidden, that's why I tore them up and put them under the manure heap. I thought they would not be found."

The young monk glanced at him in astonishment.

"You are very reckless and careless," he said. "You know that that is heresy. The works of the Holy Father are forbidden, and still more the annotations of Erasmus."

They had walked one side of the square—white figures on the white pavement, both gilded by the strong sunshine.

"Why do you concern yourself with me?" asked FrÓ Jordanus, kindly.

"I don't know," replied the other Dominican, troubled, "you seem to me to have no fear. That is what I cannot understand."

"There was nothing evil in the book, of course. We have such ignorant, malicious men in authority, people who understand nothing."

He looked up with an air of triumph at the facade of the temple of Agrippa in front of which their slow steps had come to a pause. He raised his hand and let it fall as if he was measuring the noble lengths of the pillars; he had the air of an architect who has planned a superb building.

"I don't understand you," said the young monk hurriedly, "I thought I would give you a warning. I think they mean to arrest you and hand you over to the Inquisition. It is heresy, you see."

FrÓ Jordanus looked at him kindly, almost with an air of amusement.

"What do you think I could do?" he asked.

"I don't know. I feel you are a great man. I suppose I should not say that, if you have these leanings to heresy, but I feel you are brave, too. I don't think you know what fear is."

FrÓ Jordanus glanced from the temple across the sunlit square across to the convent; a flight of pigeons filled the brilliant air. "I suppose that I had better be on my travels again."