a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Alfred And Adalgisa Author: Victor J. Daley * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 2001141h.html Language: English Date first posted: October 2020 Most recent update: October 2020 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Published in The Bulletin, Sydney NSW, 19 March 1887

Chapter 1. - The Beginning of the Trouble

Chapter 2. - The Mothers

Chapter 3. - The Infants

Chapter 4. - The Transposition Of The Infants

Chapter 5. - The Other Mother

Chapter 6. - The Effects of Custom

Chapter 7. - Confidences

Chapter 8. - Partners

Chapter 9. - The Execution

Chapter 10. - The Two Husbands

Chapter 11. - The End of the Two Husbands

Chapter 12. - Time Flies

Chapter 13. - Adalgisa

Chapter 14. - Alfred

Chapter 15. - The Happy End

It was as nearly as possible nine o’clock a. m. in the Melbourne Women’s Hospital. Perhaps it was two or three seconds earlier, or later. We will not stay to discuss this now.

Fifteen infants were lying in a row on a large bed.

They had just been washed and dressed.

The nurse, whose duty it was to wash them, always laid them out in this way—like a row of spoons.

It saved trouble.

Nurses do not like trouble.

They prefer portergaff.

The mothers of the infants were asleep—all but one who was in a state of high fever.

Her offspring was a baby boy.

The offspring of the woman in the next bed to her was a baby girl.

Here the trouble begins.

The skin of the fifteen infants was very red.

They looked like one dozen and a quarter mangold-wurze’s (beet roots) wrapped in calico.

Some of them were smiling.

A lady-visitor who was passing by remarked this, and said to the nurse:—

“The sweet little dears are listening to the angels.”

The nurse laughed—a hard, unsympathetic laugh.

“That’s only wind on the stomach,” she said, turning them over one by one on their faces and patting them on the backs till they grew the colour of boiled lobsters.

Nurses are devoid of imagination.

Constant absorption of portergaff makes them gross and matter-of-fact.

Let it—our troubles!

The woman who lay in the bed next to the one who was in a state of high fever woke up and found a male infant beside her.

She began to cry.

“What is the matter?” asked the nurse.

“They have taken away my dear little angel girl,” sobbed the mother, “and—and — put this ugly imp of a boy in her place—and I want my sweet little baby back again.”

The nurse saw at once that she had made a mistake.

Mixed up the infants, in fact.

But she would not acknowledge this.

Nurses never do.

They are like the EVENING NEWS in this respect.

She also saw that it would be useless to reason with the woman and point out to her that all newborn babies were so much alike that it was difficult to tell the difference between them, and that therefore a trifling error of this kind was excusable.

Mothers never believe this.

They all think that nature broke her mould after producing their own particular baby.

It is an amiable delusion.

Let us respect it.

Our mothers thought that way once.

The cold world thinks differently.

It is humiliating to have to admit that the cold world is right.

At the end of a fortnight the woman who was in a fever came out of it.

It left her, in fact.

The first thing she did was to cry.

The nurse came and asked her what was the matter.

She replied that somebody had taken away her little cherub-boy and put a wizen-faced elf of a girl in his place.

The nurse denied this, and insisted that she had given birth to a girl.

But the woman refused to be convinced.

“My child had lovely black hair, like silk,” she sobbed

“Well?” said the nurse.

“Ah, my God!” cried the unhappy woman, “this one has red hair—like a dingo!” And she wept afresh. But the nurse stuck to her ground. She vowed that the woman had brought a girl into the world.

“How should you know?” she said to her, “you were unconscious at the time, and have been in a fever ever since. It is only a hallucination. But if you must have a boy I can bring you one. There are plenty.”

The poor woman, being too weak to argue, said no more, but drew the little red-headed mite to her bosom.

In course of time the two mothers grew accustomed to their changelings. The nurse, by constant repetition of her story, had got them to believe it at last. They exhibited their infants to each other with pride. Each praised the child of the other, while each in her secret heart believed her own was several times sweeter, and dearer and preciouser. The nurse smiled in her sleeve. She had wide sleeves made for the purpose.

Such is the Irony of Fate.

The two mothers grew very friendly and confidential.

The husbands of both had deserted them.

They described them to each other.

One was a tall man, with beautiful black whiskers, and a cast in his left eye.

He used to write poetry for the paper. One day he came home and there was no beer in the house.

The publican had refused to give any more credit.

He—the husband—sat down and wrote a touching poem beginning with

“Farewell! Farewell! to this cold, world.”

Then he smashed some furniture and went out. He never came back again.

The husband of the other was a corporation labourer.

He was a little man, with broad shoulders and bow legs.

His hair was red.

He also smashed some furniture, and left because his wife had lent his Elzevir Edition of the Classics to the pawnbroker. He never returned.

When the two deserted wives left the Hospital they agreed to become partners in a mangle (a machine for pressing clothes).

A subscription was made for them and a mangle bought.

Then they christened the two infants. The boy was named Alfred—the girl Adalgisa.

They were good names and calculated to throw a glamour of romance over the business.

We must now turn to other scenes.

A man is about to be hanged.

He is a middle aged man with hay coloured hair.

He is calm.

Not a muscle quivers.

He looks the grim hangman in the eye and smiles.

This is not bravado: it is courage.

He knows he is going to be hanged.

However he has nothing to do with this story.

Let him hang.

This is how novels are written.

It is as easy as drinking.

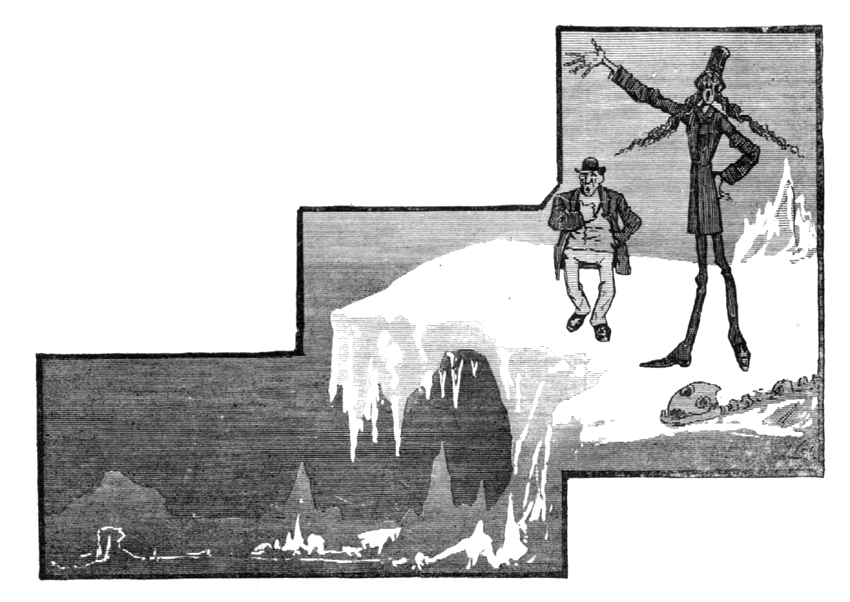

We are on an iceberg.

It is ploughing its way up from the awful silences of the Antarctic circle. Let us pause and consider the Antarctic circle.

It is a terrible thing.

It refuses to be “squared” for any consideration in gold.

It was first discovered by Sir James Ross. He brought away a piece of it, which is now in the possession of the Royal Geographical Society, if it has not melted, or been stolen since.

Two men are on the iceberg.

One is a tall man with black whiskers and a cast in his eye.

He is dressed in a plug hat and a frock-coat.

The other is a short man, with broad shoulders and bow legs.

His hair is red.

The tall man is blaspheming, and calling out for beer and tobacco.

The short man is softly murmuring to himself a passage from the “Philoctetes.”

Both are very gaunt and hungry-looking.

They have been dwelling on this iceberg for 18 years.

During that time all they have had to live upon was half a sea-serpent and a tin of preserved milk.

Such was the story told by the tall man to the whalers afterwards.

They were shipwrecked on the iceberg, and were the sole survivors of a crew of 40 souls.

There were people who said when the account was published that when Gabriel blew his trump these two would answer to 40 names.

This may have been a mere calumny. Anyhow it could never be proved against them.

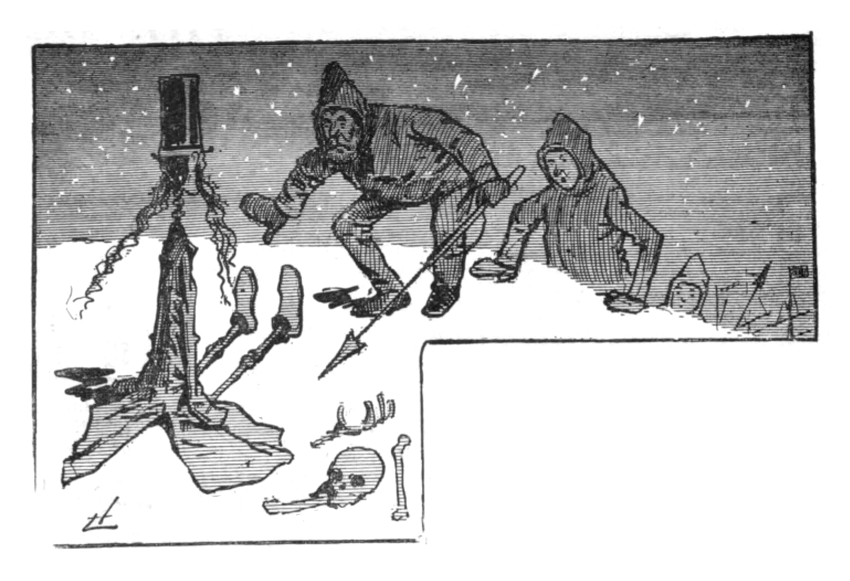

They were very hungry.

The last piece of sea-serpent had been eaten six months before.

The tall man paused in his blasphemy, and said in a hollow voice: “Delays are dangerous. Never put off till to-morrow what can be done to-day. We have nothing else to eat—we must eat each other,” which they did.

They took turn-about at cutting steaks from each other.

The icy air froze up the cuts as soon as made.

They felt no inconvenience from them, and made many jokes, which I regret I am unable to reproduce here.

In this manner they lived for two years more.

At the end of that time the short man was consumed.

The tall man lasted longest.

This was but natural.

One day a body of whalers looking for seals landed on the iceberg.

They found a small heap of bones, and beside it the head and spinal column of the tall man.

He still wore his plug hat, and his frock coat still hung around his close-picked vertebrae.

Thus does civilised man cling to respectability to the end.

He was sleeping at the time.

They jabbed him in the ear with a harpoon and he awoke.

“At last!” he murmured, “at last I see the faces of my kind again.” Then he told them his story, and gave them the address of his wife, in Collingwood, saying—“Tell her I forgive her, and have not forgotten her all these years. Look in the lining of my hat and you will find a poem. Give it to her and tell her to get it published in Melbourne PUNCH. The proceeds (if she has luck) may enable her to buy something—perhaps a jug of beer. Alas! they will buy no beer for me. And now cold world, adieu!” (You will notice that there is a good deal about the cold world in this story. That is because it is true. If it were not it would be easy to leave the cold world out—in the cold) After this affecting speech the head borrowed a piece of tobacco and died expectorating.

Thus two characters drop out of the story.

Let us now return to the mourning Penelopes.

For two or three years they lived together amicably, and made a modest living.

They were respected by all who knew them, and mangled for the Bishop.

Alfred and Adalgisa were very fond of each other.

They made mud-pies together and divided them equally.

They also shared their toffee with each other.

But this blissful time came to an end at last.

Their mothers quarrelled.

I forgot what it was about—a flat-iron, perhaps, or possibly a rolling-pin.

It does not matter, anyhow.

I will therefore say nothing more about it.

They dissolved partnership.

The mother (as she thought herself) of Adalgisa sold out her share to the other and took a public house.

She made money very fast when Adalgisa was old enough to go behind the bar.

Adalgisa is 20 years old in this chapter.

She was very pretty, though her hair was red.

Her admirers called it auburn.

One of them, who was connected with the papers, wrote a poem on it in which he compared it to the sunset.

Then he proceeded to owe half-a-crown for drinks.

But the head of Adalgisa was not turned by all this flattery.

Her heart was still true to the playmate of childhood.

She loved Alfred, though her haughty mother forbade her ever to speak to him.

Her haughty mother called him “the son of a common mangle-woman.”

But Adalgisa cherished her love in secret, and always managed to plant, in a place agreed upon between them, a gallon or two of beer to tide Alfred over the Sunday.

Thus does woman's love laugh at the Licensing Act.

Alfred is 20 years old in this chapter.

He is a good youth.

He carries clothes backwards and forwards for his (supposed) mother.

He also turns the mangle.

Likewise he loves Adalgisa

But he knows that his passion for Adalgisa is hopeless.

He is aware that her haughty mother has higher views in store for her.

He despairs.

One night the lovers meet and agree to commit suicide.

They each fasten a copy of Melbourne PUNCH to their feet and are about to throw themselves into the Yarra when a voice behind them cries “Stop!”

They stop.

The voice proceeds from a woman.

It is the nurse who changed them when they were infants.

It may seem somewhat curious that she should come across them, for the first time in 20 years, just as they were about to drown themselves, but this is always the way it happens in novels.

Then she tells them the story of how they were swapped.

They fall into each other’s arms, and weep tears of joy.

“Now,” cries Alfred, triumphantly, “your haughty mother—I mean my haughty mother— shall no longer prevent you from marrying the son of the despised mangle-woman—I mean of the despised hotel-keeper—nor shall my mother—I mean your mother—.” He pauses abruptly.

“Adalgisa,” he remarks with solemnity, “we must work this thing out on paper. It is too intricate for the unaided brain.”

The nurse at this juncture borrows a shilling to buy cough-mixture, and promises to be round next morning to make her depositions before a magistrate.

Next morning the nurse is on hand. She makes her deposition on oath before a magistrate, and he witnesses them with a quill pen.

The haughty mother is thunder struck.

The humble mother weeps.

Each has grown to love the child of the other to such an extent that to part with them is heartrending.

The nurse comes to the rescue.

“They love each other,” she says—“let them marry. They will then be the children of both of you.”

“Heaven bless you for these words,” cries the haughty hotelkeeper, embracing her, “while you have threepence you need never want a drink as long as I keep a hotel.”

The nurse touched to the heart by this generosity, weeps copiously.

Then the two mothers hug each other, and agree to bury their quarrel about the flat-iron (or rolling-pin) in the deepest part of oblivion.

Alfred and Adalgisa are married, and with their mothers-in-love-and-law live together like a family of turtle-doves ever afterwards.

The solitary iceberg with the little heap of bones on it still ploughs its way through the silent spaces of the Southern ocean. Let it plough. This story is finished.

This site is full of FREE ebooks - Project Gutenberg Australia