a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Tom Petrie's Reminiscences of Early Queensland Author: Recorded by his daughter (Constance Campbell Petrie) * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 2000451h.html Language: English Date first posted: May 2020 Most recent update: May 2020 This eBook was produced by: Colin Choat Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

TO

MY FATHER,

TOM PETRIE,

WHOSE FAITHFUL MEMORY

HAS SUPPLIED

THE MATERIAL FOR

THIS BOOK.

Tom Petrie

The greater portion of the contents of this book first appeared in the Queenslander in the form of articles, and when those referring to the aborigines were published, Dr. Roth, author of "Ethnological Studies," etc., wrote the following letter to that paper:—

* * *

Tom Petrie's Reminiscences

(By C.C.P.)

To The Editor.

Sir,—It is with extreme interest that I have perused the

remarkable series of articles appearing in the Queenslander

under the above heading, and sincerely trust that they will be

subsequently reprinted...The aborigines of Australia are fast dying

out, and with them one of the most interesting phases in the

history and development of man. Articles such as these, referring

to the old Brisbane blacks, of whom I believe but one old warrior

still remains, are well worth permanently recording in convenient

book form—they are, all of them, clear, straightforward

statements of facts—many of which by analogy, and from early

records, I have been able to confirm and verify—they show an

intimate and profound knowledge of the aboriginals with whom they

deal, and if only to show with what diligence they have been

written, the native names are correctly, i.e., rationally

spelt. Indeed, I know of no other author whose writings on the

autochthonous Brisbaneites can compare with those under the

initials of C.C.P. If these reminiscences are to be reprinted, I

will be glad of your kindly bearing me in mind as a subscriber to

the volume.

I am. Sir, etc.,

WALTER E. ROTH.

COOKTOWN, 23rd August.

My father's name is so well known in Queensland that no explanation of the title of this book is necessary. Its contents are simply what they profess to be—"Tom Petrie's Reminiscences;" no history of Queensland being attempted, though a sketch of life in the early convict days is included in its pages. My father's association with the Queensland aborigines from early boyhood, was so intimate, and extended over so many years, that his experience of their manners, their habits, their customs, their traditions, myths, and folklore, have an undoubted ethnological value. Realising this, I determined as far as lay in my power to save from oblivion by presenting in book form, the vast body of information garnered in the perishable storehouse of one man's—my father's—memory.

To my friend. Dr. Roth, Chief Protector of Aboriginals, Queensland, I am indebted for the proper spelling of aboriginal words, and I wish to thank him for all his kindly interest and help. The spelling thus referred to is that adopted by the Royal Geographical Society of London, and followed in other continental countries. In this connection I may mention that the Brisbane or Turrbal tribe is identical with the Turrubul tribe of Rev. W. Ridley. It was my father who gave this gentleman the original information concerning these particular blacks.

Scientific names of trees and plants have been obtained through the courtesy of Mr. F. M. Bailey, F.L.S., Government Botanist, Brisbane.

Constance Campbell Petrie.

"Murrumba," North Pine,

October, 1904.

PART I.

Tom Petrie—Andrew Petrie—Moreton Bay in the Thirties—Petrie's Bight—First Steamer in the River—"Tom's" Childhood—"Kabon-Tom"—Brisbane or Turrbal Tribe—North Pine Forty-five years ago—Alone with the Blacks—Their Trustworthiness and Consideration—Arsenic in Flour—Black Police—Shooting the Blacks—Inhuman Cruelty—St. Helena Murder—Bribie Island Murder.

Bonyi Season on the Blackall Range—Gatherings like Picnics—Born Mimics—"Cry for the Dead"—Treated like a Prince—Caboolture (Kabul-tur)—Superstitions of the Blacks—Climbing the Bonyi—Gathering the Nuts—Number at these Feasts—Their Food while there—Willingness to Share.

Sacrifice—Cannibalism—Small Number killed in Fights—Corroborees—"Full Dress"—Women's Ornaments—Painted Bodies—Burying the Nuts—Change of Food—Teaching Corroborees—Making new ones—How Brown's Creek got its Name—Kulkarawa—"Mi-na Mee-na".

"Turrwan" or Great Man—"Kundri"—Spirit of Rainbow—A Turrwan's Great Power—Sickness and Death—Burial Customs—Spirit of the Dead—Murderer's Footprint—Bones of Dead—Discovering the Murderer—Revenge—Preparations for a Cannibal Feast—Flesh Divided Out—A Sacred Tree—Presented with a Piece of Skin—Cripples and Deformed People.

How Names were given—"Kippa"-making—Two Ceremonies—Charcoal and Grease Rubbed on Body—Feathers and Paint—Exchanging News—Huts for the Boys—Instructions given them—"Bugaram"—"Wobbalkan"—Trial of the Boys—Red Noses—"Kippa's Dress."

Great Fight—Camping-ground—Yam-sticks—Boys' Weapons—Single-handed Fight—Great Gashes—Charcoal Powder for Healing—Same Treatment Kill a White man—Nose Pierced—Body Marked—"Kippa-ring"—"Kakka"—Notched Stick—Images Along the Road-way.

"Fireworks Display"—Warning the Women—Secret Corroboree—"Look at this Wonder"—Destroying the "Kakka"—How Noses were Pierced—Site of Kippa-rings"—Raised Scars—Inter-tribal Exchange of Weapons, etc.—Removing Left Little Finger—Fishing or Coast Women.

Mourning for the Dead—Red, White, and Yellow Colouring—No Marriage Ceremony—Strict Marriage Laws—Exchange of Brides—Mother-in-Law—Three or Four Wives—Blackfellows' Dogs—Bat Made the Men and Night-Hawk the Women—Thrush which Warned the Blacks—Dreams—Moon and Sun—Lightning—Cures for Illness—Pock Marks—Dugong Oil.

Food—How It was Obtained—Catching and Cooking Dugong—An Incident at Amity Point—Porpoises Never Killed; but Regarded as Friends—They Helped to Catch Fish—Sea Mullet and Other Fish—Fishing Methods—Eels—Crabs—Oysters and Mussels—Cobra.

Grubs as Food—Dr. Leichhardt and Thomas Archer Tasting Them—Ants-Native Bees—Seeking for Honey—Climbing with a Vine—A Disgusting Practice—Sweet Concoction—Catching and Eating Snakes—Iguanas and Lizards—Another Superstition—Hedgehogs—Tortoises—Turtles.

Kangaroos—How Caught and Eaten—Their Skins—The Aboriginal's Wonderful Tracking Powers—Wallaby, Kangaroo Rat, Paddymelon, and Bandicoot—'Possum—'Possum Rugs—Native Bear—Squirrel—Hunting on Bowen Terrace—Glass House Mountain—Native Cat and Dog—Flying Fox.

Emus—Scrub Turkeys—Swans—Ducks—Cockatoos and Parrots—Quail—Root and Other Plant Food—How it was Prepared—Meals—Water—Fire—How obtained—Signs and Signals.

Canoe-making—Rafts of Dead Sticks—How Huts were Made—Weapon Making—Boomerangs—Spears—Waddies—Yam Sticks—Shields—Stone Implements—Vessels—Dilly-Bags—String.

Games—"Murun Murun"—"Purru Purru"—"Murri Murri"—"Birbun Birbun"—Skipping—"Cat's Cradle"—"Marutchi"—Turtle Hunting as a Game—Swimming and Diving—Mimics—"Tambil Tambil."

Aboriginal Characteristics—Hearing—Smelling—Seeing—Eating Powers—Noisy Creatures—Cowards—Property—Sex and Clan "Totems"—"The Last of His Tribe."

Folk Lore—The Cockatoo's Nest—A Strange Fish—A Love Story—The Old-woman Ghost—The Clever Mother Spider—A Brave Little Brother—The Snake's Journey—The Marutchi and Bugawan—The Bittern's Idea of a Joke—A Faithful Bride—The Dog and the Kangaroo—The Cause of the Bar in South Passage.

Duramboi—His Return to Brisbane—Amusing the Squatters—His Subsequent Great Objection to Interviews—Mr. Oscar Friström's Painting—Duramboi Making Money—Marks on His Body—Rev. W. Ridley—A Trip to Enoggera for Information—Explorer Leichhardt—An Incident at York's Hollow—An Inquiry Held.

A Message to Wivenhoe Station after Mr. Uhr's Murder—Another Message to Whiteside Station—Alone in the Bush—A Coffin Ready Waiting—The Murder at Whiteside Station—Piloting "Diamonds" Through the Bush—A Reason for the Murder—An Adventure Down the Bay—No Water; and Nothing to Eat but Oysters—A Drink out of an Old Boot—The Power of Tobacco—"A Mad Trip."

A Search for Gold—An Adventure with the Blacks—"Bumble Dick" and the Ducks—The Petrie's Garden—Old Ned the Gardner—"Tom's" Attempt to Shoot Birds—Aboriginal Fights in the Vicinity of Brisbane—The White Boy a Witness—"Kippa" making at Samford—Women Fighting Over a Young Man—"It Takes a Lot to Kill a Blackfellow"—A Big Fight at York's Hollow—A Body Eaten.

Early Aboriginal Murderers—"Millbong Jemmy" and His Misdeeds—Flogged by Gilegan the Flogger—David Petty—Jemmy's Capture and Death—"Dead Man's Pocket"—An Old Prisoner's Story—Found in a Wretched State—Weather-bound with the Murderers on Bribie Island—Their Explanation—"Dundalli" the Murderer—Hanged in the Present Queen Street—A Horrible Sight—Dundalli's Brother's Death.

The Black Man's Deterioration—Worthy Characters—"Dalaipi"—Recommending North Pine as a Place to Settle—The Birth of "Murrumba"—A Portion of Whiteside Station—Mrs. Griflfen—The First White Man's Humpy at North Pine—Dalaipi's Good Qualities—A Chat with Him—His Death—With Mr. Pettigrew in Early Maryboro'—A Very Old Land-mark at North Pine—Proof of the Durability of Blood-wood Timber—The Word "Humpybong."

A Trip in 1862 to Mooloolah and Maroochy—Tom Petrie the First White Man on Buderim Mountain—Also on Petrie's Creek—A Specially Faithful Black—Tom Petrie and his "Big Arm"—Twenty-five Blacks Branded—King Sandy one of them—The Blacks Dislike to the Darkness—Crossing Maroochy Bar Under Difficulties—Wanangga "Willing" his Skin Away—Doomed—A Blackfellow's Grave Near "Murrumba."

"Puram," the Rain-maker—"Governor Banjo"—His Good Nature—A Ride for Gold with Banjo—Acting a Monkey—Dressed Up and Sent a Message—Banjo and the Hose—"Missus Cranky"—Banjo's Family—His Kindness to Them—An Escape from Poisoning—Banjo's Brass Plate.

Prince Alfred's Visit to Brisbane in 1868—A Novel Welcome to the Duke—A Black Regiment—The Man in Plain Clothes—The Darkies' Fun and Enjoyment—Roads Tom Petrie has Marked—First Picnic Party to Humpybong—Chimney round which a Premier Played—Value of Tom Petrie's "Marked Tree Lines"—First Reserve for Aborigines in Queensland (Bribie Island)—The Interest It Caused—Father McNab—Keen Sense of Humour—Abraham's Death at Bribie—Piper, the Murderer—Death by Poison.

PART II.

Death in 1872 of Mr. Andrew Petrie—A Sketch of His Life taken from the Brisbane Courier—Born in 1798—His Duties in Brisbane—Sir Evan Mackenzie—Mr. David Archer—Colonel Barney—An Early Trip to Limestone (Ipswich)—Two Instances of Aborigines Recovering from Ghastly Wounds.

"Tinker," the Black and White Poley Bullock—Inspecting the Women's Quarters at Eagle Farm—A Picnic Occasion—Cutting in Hamilton Road, made originally by Women Convicts—Dr. Simpson—His After-dinner Smoke—His Former Life—The "Lumber-yard"—The Prisoners' Meals—The Chain-gang—Logan's Reign—The "Crow-minders"—"Andy."

"Andy's" Cooking—Andrew Petrie's Walking Stick as a Warning—Tobacco-making on the Quiet—One Pipe Among a Dozen—The Floggings—"Old Bumble"—Gilligan, the Flogger, Flogged Himself—His Revenge—"Bribie," the Basket-maker—Catching Fish in Creek Street—Old Barn the Prisoners Worked In—"Hand carts."

The Windmill (present Observatory)—Overdue Vessel—Sugar or "Coal Tar"—On the Treadmill—Chain Gang Working Out Their Punishment—Leg Irons Put On—Watching the Performance—Prisoner's Peculiar Way of Walking—"Peg-leg" Kelly—Fifteen or Sixteen Years for Stealing Turnips—Life for Stealing a Sheep—Tom Petrie's Lessons—The Convict's "Feather Beds"—First Execution by Hanging—Sowing Prepared Rice.

Mount Petrie—"Bushed"—The Black Tracker—Relic of the Early Days—Andrew Petrie's Tree—Early Opinion of the Timbers of Moreton Bay—An Excursion to Maroochy—First Specimens of Bunya Pine—First on Beerwah Mountain—"Recollections of a Rambling Life"—Mr. Archer's Disappointment—Another Excursion—A Block of Bunya Timber—"Pinus Petriana"—Less Title to Fame—Discoveries of Coal, etc.

Journal of an Expedition to the "Wide Bay River" in 1842—Discovery of the Mary—Extract from Mr. Andrew Petrie's Diary—Encountering the Aborigines—Bracefield—Same Appearance as the Wild Blacks—Davis—"Never Forget His Appearance"—Could Not Speak His "Mither's Tongue"—Blackfellow with a Watch—Mr. McKenzie's Murdered Shepherds—Frazer Island—Mr. Russell Sea-sick.

The Alteration of Historical Names—Little Short of Criminal—Wreck of the "Stirling Castle"—Band of Explorers—Sir George Gipps—Trip Undertaken in a "Nondescript Boat"—Mr. Russell's Details of the Trip—A Novel Cure for Sunstroke—Gammon Island—Joliffe's Beard.

The Early-time Squatters—Saved by the Natives from Drowning—Mr. Henry Stuart Russell—"Tom" Punished for Smoking—"Ticket-of-Leave" Men—First Racecourse in Brisbane—Harkaway—Other Early Racecourses—Pranks the Squatters Played—Destiny of South Brisbane Changed—First Vessel Built in Moreton Bay—The Parson's Attempt to Drive Bullocks—A Billy-goat Ringing a Church Bell—The First Election—Changing Sign-boards—Sir Arthur Hodgson—Sir Joshua Peter Bell.

"Old Cocky"—His Little Ways—The Sydney Wentworths' "Sulphur Crest"—"Boat Ahoy!"—"Cocky" and the Ferryman—"It's Devilish Cold"—"What the Devil are You Doing There?"—Disturbing the Cat and Kittens—Always Surprising People—Teetotaller for Ever—The Washerwoman's Anger—Vented His Rage on Dr. Hobbs—Loosing His Feathers—Sacrilege to Doubt—"People Won't Believe That"—Governor Cairns.

Mr. Andrew Petrie's Loss of Sight—Walked His Room in Agony—Blind for Twenty-four Years—Overlooking the Workmen—Never Could be Imposed Upon—His Wonderful Power of Feeling—Walter Petrie's Early Death—Drowned in the Present Creek Street—Only Twenty-two Years—Insight into the Unseen—"You Will Find My Poor Boy Down There in the Creek"—A Very Peculiar Coincidence—Walter Petrie's Great Strength—First Brisbane Boat Races.

Great Changes in One Lifetime—How Shells and Coral Were Obtained for Lime-making—King Island or "Winnam"—Lime-burning on Petrie's Bight—Diving Work—Harris's Wharf—A Trick to Obtain "Grog"—Reads Like Romance—Narrow Escape of a Diver.

Characters in the Way of "Old Hands"—Material for a Charles Dickens—"Cranky Tom"—"Deaf Mickey"—Knocked Silly in Logan's Time—"Wonder How Long I've Been Buried"—Scene in the Road Which is Now Queen Street—A Peculiar Court Case—First Brisbane Cemetery.

List of Places, Names, Plants and Trees.

TOM PETRIE'S REMINISCENCES.

Perhaps no one now living knows more from personal experience of the ways and habits of the Queensland aborigines than does my father—Tom Petrie. His experiences amongst these fast-dying-out people are unique, and the reminiscences of his early life in this colony should be recorded; therefore I take up my pen with the wish to do the little I can in that way. My father has spent his life in Queensland, being but three months old when leaving his native land. He was born at Edinburgh, and came out here with his parents in the Stirling Castle in 1831. He is now the only surviving son of the late Andrew Petrie, a civil engineer, who, as every one interested knows, had much to do with Queensland's young days.

The Petrie family landed first in New South Wales, but in 1837 (about twelve years after foundation of Brisbane) came on to Queensland in the James Watt, "the first steamer which ever entered what are now Queensland waters." The late John Petrie, the eldest son, was a boy at the time, and "Tom ", of course, but a child. Their father, the founder of the family, was attached to the Royal Engineers in Sydney, and was chosen to fill the position of superintendent or engineer of works in Brisbane. The Commandant in the latter place had been driven to petition for the services of a competent official, as there seemed no end to the blunders and mistakes always being made. The family came as far as Dunwich in the James Watt, then finished the journey in the pilot boat, manned by convicts, and landed at the King's Jetty—the present Queen's Wharf—the only landing place then existing.

Although my father cannot look back to this day of arrival, he remembers Brisbane town as a city of about ten buildings. Roughly speaking it was like this: At the present Trouton's corner stood a building used as the first Post Office, and joined to it was the watchhouse; then further down the prisoners' barracks extended from above Chapman's to the corner (Grimes & Petty). Where the Treasury stands stood the soldiers' barracks, and the Government hospitals and doctors' quarters took up the land the Supreme Court now occupies. The Commandant's house stood where the new Lands Office is being built (his garden extending along the river bank), and not far away was the Chaplain's quarters. The Commissariat Stores were afterwards called the Colonial Stores, and the block of land from the Longreach Hotel to Gray's corner was occupied by the "lumber yard" (where the prisoners made their own clothes, etc.). The windmill was what is now the Observatory, and, lastly, a place formerly used as a female factory was the building Mr. Andrew Petrie lived in for several months till his own house was built. The factory stood on the ground now occupied by the Post Office, and later on the Petrie' s house was built at the present corner of Wharf and Queen Streets, going towards the Bight (hence the name Petrie's Bight). Their garden stretched all along the river bank where Thomas Brown and Sons' warehouse now stands, being bounded at the far end by the saltwater creek which ran up Creek Street.

Kangaroo Point, New Farm, South Brisbane, and a lot of North Brisbane were then under cultivation, but the rest was all bush, which at that time swarmed with aborigines. So thick was the bush round Petrie's Bight that one of the workmen (a prisoner), engaged in building the house there, was speared; he wasn't much hurt, however, and recovered.

While living at the Bight when a boy my father remembers watching the first steamer which ever came up the river (the James Watt stayed in the Bay). When she rounded Kangaroo Point, with her paddles going, the blacks, who were collected together watching, could not make it out, and took fright, running as though for their lives. They were easily frightened in those days. Father remembers another occasion on which they were terrified. His father one night got hold of a pumpkin, and hollowing it out, formed on one side a face, which he lit up by placing a candle inside, the light shining through the openings of the eyes and mouth. This head he put on a pole, and then wrapping himself in a sheet with the pole, he looked, to the frightened blacks' imagination, for all the world like a ghost, and they could hardly get away fast enough.

From early childhood "Tom" was often with the blacks, and since there was no school to go to, and hardly a white child to play with, he naturally chummed in with all the little dark children, and learned their language, which to this day he can speak fluently. A pretty, soft-sounding language it is on his lips, but rather the opposite when spoken by later comers; indeed, I do not think that any white man unaccustomed to it from childhood can ever successfully master the pronunciation.

"Tom," and his only sister, when children, used to hide out among the bushes, in order to watch the blacks during a fight; and once when the boy had been severely punished by his father for smoking, he ran away from home, and after his people had looked everywhere, they found him at length in the blacks' camp out Bowen Hills way. There was one blackfellow at that time these children used to torment rather unmercifully: a very fierce old man, feared even by the blacks, who believed he could do anything he choose in the way of causing death, etc. He was called "Mindi-Mindi" (or "Kabon-Tom" by the whites), was the head of a small fishing tribe who generally camped at the mouth of the South Pine river, and was a great warrior. One day the children found him outside their home. They teased and called him names in his own tongue till the man grew so fierce that he chased the youngsters right inside. The girl got under a bed, and "Tom" up on a chair, where the blackfellow caught him, and taking his head in his hands started to screw his neck. One hand held the boy's chin and the other the top of his head, and in a few minutes more his life would have ended, but the screams brought the mother just in time. Father's neck was stiff for some time after this, and the children never tormented old "Kabon-Tom" again. They declared always that this man had a perfectly blue tongue, and the palms of his hands were quite white. It was said that he screwed his own little daughter's neck, and thought nothing of such things. However, he and "Tom" were generally friends, indeed this is about the only occasion on which the boy fell out with a blackfellow. "Kabon-Tom" must have been about ninety when he died, and was a very white-haired old man. He was found lying dead one day in the mud in the Brisbane river.

Later on in life, when my father employed the blacks, they were always kind and considerate about him. They are naturally an affectionate people, and he with his good and kindly disposition, and his fun—for the blacks do so enjoy a joke—was very popular with them all. Nowadays it is seldom one sees an aboriginal, but some years ago, when they would come at times and camp round about here (North Pine), it was amusing to see the excitement when they found their old friend in the mood for a yarn. To watch their faces was as good as a play, and to hear Father talk with them!—it seemed all such nonsense, and many a time has some one looking on been convulsed with laughter. A good-natured people they surely are, for amusement at their expense does not call forth resentment; rather would they join in the laugh.

Queensland is a large country, and the tribes in the North differ in their languages, habits, and beliefs from the blacks about Brisbane. Father was very familiar with the Brisbane tribe (Turrbal), and several other tribes all belonging to Southern Queensland who had different languages, but the same habits, etc. The Turrbal language was spoken as far inland as Gold Creek or Moggill, as far north as North Pine, and south to the Logan, but my father could also speak to and understand any black from Ipswich, as far north as Mount Perry, or from Frazer, Bribie, Stradbroke, and Moreton Islands. Of all the blackfellows who were boys when he was a boy there is only one survivor; most of them died off prematurely through drink, introduced by the white man.

On first coming, nearly forty-five years ago, to North Pine, which is sixteen miles by road from Brisbane, the country round about was all wild bush, and the land my father took up was a portion of the Whiteside run. The blacks were very good and helpful, lending a hand to split and fence and put up stockyards, and they would help look after the cattle and yard them at night. For the young fellow was all alone, no white man would come near him, being in dread of the blacks. Here he was among two hundred of them, and came to no harm.

When, with their help, he had got a yard made, and a hut erected, he obtained flour, tea, sugar, and tobacco from Brisbane, and leaving these rations in the hut, in charge of an old aboriginal, went again to Brisbane, and was away this time a fortnight. Fifty head of cattle he also left in the charge of two young blacks, trusting them to yard these at night, etc; and to enable the young darkies to do this, he allowed them each the use of a horse and saddle. On his return all was as it should be, not even a bit of tobacco missing! And those who know no better say the aborigines are treacherous and untrustworthy! Father says he could always trust them; and his experience has been that if you treated them kindly they would do anything for you.

On the occasion just mentioned, during his absence, a station about nine miles away ran short of rations, and the stockman was sent armed with a carbine and a pair of pistols to see if he could borrow from Father. Arrived at his destination, the man found but blacks, and they simply would give him nothing until the master's return. The hut had no doors at the time, and yet they hunted for their own food, touching nothing.

A further refutation of the treachery and untrustworthiness of the blacks is the following:—One young fellow, learning to ride in those days, was thrown several times. My father, vexed with the mare ridden, mounted her himself, and giving the animal a sharp cut with his riding whip, sent her off at full gallop. He carried a revolver in his belt, which he always had handy, as often the blacks would get him to shoot kangaroos they had surrounded and hunted into a water-hole. The mare galloped on, then, stopping suddenly, somehow threw her rider in spite of his good seat. The first thing he remembered afterwards was seeing a company of blacks collected round him, crying, and one old man on his knees sucking his back, where the hammer of the revolver had struck. They then carried him to his hut, and in the morning he was nothing but stiff after his adventure. And there was no white man about!

Many a time when the blacks wished to gather their tribes together for a corroboree (dance and song), or fight, they would send on two men to inquire of Father which way to come so as not to disturb his cattle. This was more than many a white man would do, he says. To him they were always kind and thoughtful, and he wishes this to be clearly understood, for sometimes the blacks are very much blamed for deeds they were really driven to; and of course they resented unkindness. For instance, the owner of a station some distance away used to have his cattle speared and killed. Father would remonstrate and ask the why, and the blacks would answer: It was because if that man caught any of them he would shoot them down like dogs! Then they told this tale: A number of blacks were on the man's run, scattered here and there, looking for wild honey and opossums, when the owner came upon them and shooting one young fellow, first broke his leg, then another shot in the head killed him. The superior white man then hid himself to watch what would happen. Presently the father came looking for his son, and he was shot; the mother coming after met the same fate.

My father knew the blacks well who told him this, and was satisfied they spoke truthfully. It may strike the reader, why did he not make use of his information and bring punishment to the offender? Well, because in those days a blackfellow's evidence counted as nothing, and no good would therefore be gained, but rather the opposite, as the bitterness would be increased, and the blacks get the worst of it. You see, the white men had so many opportunities for working harm; at that time several aboriginals were poisoned through eating stolen flour, it having been carefully left in a hut with arsenic in it.

To show that the aborigines were not unforgiving, here is an example: The squatter before mentioned, who shot the blacks, went once to Father to see if he would use his influence with the aborigines and get them to go to his station and drive wild cattle from the mountain scrub—a difficult undertaking. He agreed to see what could be done, on condition that the blacks were considerately treated, and advised the man to leave all firearms behind, and accompany him to their camp, where he would do his best. "Oh, no! I can't do that," was the reply. "If you won't come to the camp," replied Father, "they will not understand, and won't go; you need fear nothing; they will not touch you while I'm there."

After some discussion, the man was persuaded, though he evidently was in fear and trembling during the whole interview. The blacks agreed to go next day, which they did, leaving their gins and pickaninies under Father's care till their return. In three days they were back, and reported they had got a number of cattle from the scrub, and that the man—"John Master" they called him—had killed a bull for them to eat, and was all right now, not "saucy" any more. They added that they had agreed to go back again, and strip bark for him.

This second time the blacks took their women folk and children, and were away for two or three weeks working for the squatter, cutting bark, etc., and were evidently quite contented and happy. However, in the meantime a report was got up on the station to the effect that the blacks were killing some of the cattle; so a man was sent to where Sandgate now is to ask assistance from the black police, who were stationed there.

These black police were aborigines from New South Wales and distant places, and they, with their white leader, came and shot several blacks, the remaining poor things returning at once to their friend in a great state, protesting they had not touched a beast. Father met the squatter soon after, and said to him: "You're a nice sort of fellow; how could you cause those poor blacks to be shot like that? You know perfectly well they did not kill your cattle." The man excused himself by saying that it was done without his knowledge, that he had a young fellow learning station work who got frightened over the blacks, and went for the police on his own account.

Another time, while out riding in the bush, my father heard a great row, and a voice calling, "Round them up, boys!" And on galloping up he came upon a number of poor blacks—men, women, and children—all in a mob like so many wild cattle, surrounded by the mounted black police. The poor creatures tried to run to their friend for protection, and he inquired of the officer in charge what was the meaning of it all. The officer—a white man, and one, by the way, who was noted for his inhuman cruelty—replied that they merely wished to see who was who. But Father knew that if he hadn't turned up, a number of the poor things would have been shot. Can one wonder there were murders committed by the blacks, seeing how they were sometimes treated? This same police officer (Wheeler, by name), later on was to have been hanged for whipping a poor creature to death, but he escaped and fled from the country. It is possible he is still alive. His victim was a young blackfellow, whom he had tied to a verandah post, and then brutally flogged till he died.

Three men were once murdered at St. Helena Island by aboriginals, and this is the side of the question given by "Billy Dingy" (so called by the whites), one of the blacks concerned. Billy said that he and two other young men, each with his young wife, were taken in a boat by three white men, who promised to land them at Bribie Island, as it was then the great "bunya season," and the aborigines always met there before travelling to the Bunya Mountains (or, to be correct, Bon-yi Mountains—the natives always pronounced it so). Of the "bon-yi season" I will speak later on.

Well, these men, instead of doing as they had promised, landed at St. Helena, and there set nets for catching dugong, acting as though they had not the slightest intention of going near Bribie. They also took possession of the young gins, paying no heed to Billy, who pleaded for their wives and to be taken to Bribie as promised. So Billy, poor soul, didn't know what to do, and at last bethought him to kill the men. He did it in this way: Some distance from where they were camped a cask was sunk in the sand for fresh water, and Billy, in broken English, called to one of the men. Bob Hunter by name: "Bob, Bob, come quick, bring gun, plenty duck sit down longa here." Bob went to Billy all unthinking, and, passing the cask in the sand knelt to drink. There was Billy's chance, and he took it, striking the man from behind with a tomahawk on the back of the head. Bob threw up his arm to save himself, only to be cut on the arm, and then again on the head, and was killed. Billy then dragged him down to the water; and that was the end of that man.

On returning to the camp after this "deed of darkness," Billy told the gins in his own language of what had happened, and that he meant to finish by killing the other two, and they then could all get away together. The gins begged of him not to kill the others, but his mind was fixed, and remained unmoved. Fortune favoured him surely, for he found one man alone sitting by a camp fire smoking, and, creeping up stealthily behind him, cut open his head with the tomahawk; and this man's body was in turn dragged to the water.

There now remained but one other, and he at that time away in the scrub shooting pigeons. Billy followed, and, watching his opportunity, struck the white man as he stooped to go under a vine. This last body was also dragged to the water, and that was the end of the three; and who can say the blacks were wholly to blame?

After the white men were thus disposed of, the natives all got into the boat and came to the mouth of the Pine River, where they left the boat, and walking round on the mainland opposite Bribie, swam across to the island. Bob Hunter's body was afterwards recovered, and it had a cut on the arm even as Billy described to my father. The other bodies were never found, and it was thought they were eaten by sharks.

My father had these three men—Billy and the others—working for him afterwards till their death, and found them all right. He was also alone for days with Billy in the forest looking for cedar timber.

An old man called Gray was killed at Bribie Island (July, 1849). This is the blacks' version as told to their friend: Gray used to go to Bribie with a cutter for oysters; he had a black boy as a help when gathering the oysters on the bank, and he imagined this boy wasn't fast enough in his work, so beat him rather unmercifully, being blessed with a bad temper. The boy escaped and ran away from the oyster bank, swimming to the island, and he told the blacks of his ill-treatment. They were worked up to resentment, and went across and killed Gray. Father says of the latter: "I knew poor old Gray well; he was a very cross old man, and many a slap on the side of the head I got from him when a boy."

HAVING given some instances as proof of the statement that the blacks were murderers or quite otherwise, according to the white man's treatment of them, I will pass now to their native customs, and tell you of the "Bon-yi season." "Bon-yi," the native name for the pine, Araucaria Bidwilli, has been wrongly accepted and pronounced bunya. To the blacks it was bon-yi, the "i" being sounded as an "e" in English, "bon-ye." Grandfather (Andrew Petrie) discovered this tree, but he gave some specimens to a Mr. Bidwill, who forwarded them to the old country, and hence the tree was named after him, not after the true discoverer. Of this more anon.

The bon-yi tree bears huge cones, full of nuts, which the natives are very fond of. Each year the trees will bear a few cones, but it was only in every third year that the great gatherings of the natives took place, for then it was that the trees bore a heavy crop, and the blacks never failed to know the season.

These gatherings were really like huge picnics, the aborigines belonging to the district sending messengers out to invite members from other tribes to come and have a feast. Perhaps fifteen would be asked here, and thirty there, and they were mostly young people, who were able and fit to travel. Then these tribes would in turn ask others. For instance, the Bribie blacks (Ngunda tribe) on receiving their invitation would perchance invite the Turrbal people to join them, and the latter would then ask the Logan, or Yaggapal tribe and other island blacks, and so on from tribe to tribe all over the country, for the different tribes were generally connected by marriage, and the relatives thus invited each other. Those near at hand would all turn up, old and young, but the tribes from afar would leave the aged and the sick behind.

My father was present at one of these feasts, when a boy, for over a fortnight. He is the only free white man who has ever been present at a bon-yi feast. Two or three convicts in the old days, who escaped and lived afterwards with the blacks—James Davis ("Duramboi"), Bracefield ("Wandi"), and Fahey ("Gilbury"), of course, knew all about it, but they are dead now. Father met the two former after their return to civilization, and he has often had a yarn with the old blacks who belonged to the tribes they had lived with.

In those early days the Blackall Range was spoken of as the Bon-yi Mountains, and it was there that Duramboi and Bracefield joined in the feasts, and there also that Father saw it all. He was only fourteen or fifteen years old at the time, and travelled from Brisbane with a party of about one hundred, counting the women and children. They camped the first night at Bu-yu—ba (shin of leg), the native name for the creek crossing at what is now known as Enoggera.

After the camp fires were made and breakwinds of bushes put up as a protection from the night, the party all had something to eat, then gathered comfortably round the fires, and settled themselves ready for some good old yarns, till sleep would claim them for his own. Tales were told of what forefathers did, how wonderful some of them were in hunting and killing game, also in fighting. The blacks have lively imaginations of what happened years ago, and some of the incidents they remembered of their big fights, etc., were truly marvellous! They are also born mimics, and my father has often felt sore with laughing at the way they would take off people, and strut about, and imitate all sorts of animals.

When aborigines are collected anywhere together, each morning at daylight a great cry arises, breaking through the silence: this is the "cry for the dead." Imagine it, falling on the stillness after the night! It comes with the dawn and the first call of the birds; as the Australian bush awakens and stirs, so do Australia's dark children—or, rather they used to, for all is changed now. It must have been weird, that wailing noise and crying; but one could imagine the birds and animals expecting it and listening for it; and the sun in those days would surely have thought something had gone wrong, had there been no great cry to accompany his arising. Whether the dead were the better for the mourning, who can say? But they were always faithfully mourned for, each morning, and at dusk each night. It was crying and wailing and cursing all mixed up together, and was kept going for from ten to twenty minutes, such a noise being made that it was scarcely possible to hear oneself speak. Each person vowed vengeance on their relative's murderer, swearing all the time. To them it was an oath when they called a man "big head," "swelled body," "crooked leg," etc.; and so they cursed and howled away, using all the "oaths" they could think of. There was never a lack of some one to mourn for; so this cry was never omitted, night or morning.

After the dying down of the cry at daybreak, the blacks would have their morning meal, and then, as in the case of this journey to the Bon-yi Mountains, when my father accompanied them, they made ready to move forward on their way. A blackfellow would shout out the name of the place at which they were to meet again that night—this time it happened to be the Pine—and off they all went, hunting here and there, catching all sorts of animals, getting wild honey, too, and coming into the appointed place that night laden with spoil. This same thing went on day by day, and Father was treated like a prince among them all. They never failed to make him a humpy for the night, roofed with bark or perhaps grass; while for themselves they didn't trouble, unless it rained. The third night they camped at Caboolture (Kabul-tur, "place of carpet snakes"), and next day started for the Glasshouse Mountains.

During this journey my father noticed some superstitions of the blacks. For instance, going up the spur of a hill a dog ran through between the legs of a blackfellow, and the man stood stock still and called the dog back, making it return through his legs. When asked why, he said they would both die otherwise. Then, again, they travelled along a footpath, which ran up a ridge, where there was but room to walk one by one, and the white boy noticed a half-fallen tree leaning across the way. Coming to the tree, the first blackfellow paused and pulled a bush from the roadside, and, throwing it down on the path, quietly walked round the tree, the rest following him. Father asked the reason, and the man said that if any one walked under that tree his body would swell, and he would die; he also said that he threw the bush down as a warning to the others. My father, of course, boy-like, wished to show there was nothing in all this, and walked assuredly under the tree, drawing attention to the fact that he didn't die. "Oh, but you are white," they said.

It was the same thing always with regard to a fence; the aboriginals would never climb through or under a fence, but always over, thinking here too that their body would swell and they would die. In the same way a blackfellow would rather you knocked him down than have you step over him or any of his belongings, because to him it meant death. Supposing a gin stepped over one of them—naughty woman!—she would be killed instantly. Father has lain on the ground, and offered to let men, women, and children all step over his body, and if he died they were right in their belief; but, if not, they were wrong. He offered blankets, flour, a tomahawk; but no, nothing would induce them, for they said they did not wish to see him die. As he survived the great ordeal of walking under a tree, because of being a white man, one would think they would risk the other, especially with a promised reward in view. But not they.

Of course, we are speaking of the past; the blacks one sees of late years will go through a fence or under a tree, or anything; just as they will smoke or drink spirits. They used to be fine, athletic men, remarkably free from disease, tall, well-made and graceful, with wonderful powers of enjoyment; now they are often miserable, diseased, degraded creatures. The whites have contaminated them.

On the fourth day of this journey, about 4 o'clock, the party arrived near Mooloolah, at a creek with a scrub on it, and all hands fell to making fires for cooking purposes, etc., and they stripped some bark to make a hut ("ngudur") for their white friend to sleep in, some placing a "pikki" (vessel made from bark) of water ready to his hand, others bringing him yams and honey or anything he fancied to eat. He had a little flour and tea and sugar with him, which the blacks carried, but never touched, leaving them for him. They did not think it worth while making huts for themselves for one night, but just camped alongside the fire with opossum rug coverings.

Arriving at the Blackall Range, the party made a halt at the first bon-yi tree they came to, and a blackfellow accompanying them, who belonged to the district, climbed up the tree by means of a vine. When a native wishes to climb a tree that has no lower branches he cuts notches or steps in the trunk as he goes up, ascending with the help of a vine held round the stem. But my father's experience has been that the blacks would never by any chance cut a bon-yi, affirming that to do so would injure the tree, and they climbed with the vine alone, the rough surface of the tree helping them.

This tree they came first upon was a good specimen, 100 feet high before a branch, and when the native climbing could reach a cone he pulled one and opened it with a tomahawk to see if it was all right. (The others said if he did not do this the nuts would be empty and worthless, and Father noticed afterwards that the first cone was always examined before being thrown to the ground.) Then the man called out that all was well, and, throwing down the cone, he broke a branch, and with it poked and knocked off other cones. As they fell to the ground, the blacks assembled below would break them up and, taking out the nuts, put them in their dilly-bags. Afterwards they went further on, and, camping, made fires to roast the nuts, of which they had a great feed—roasted they were very nice.

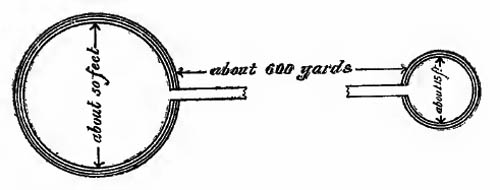

Next day they travelled on again, till they came to where the tribes were all assembling from every part of the country, some hailing from the Burnett, Wide Bay, Bundaberg, Mount Perry, Gympie, Bribie, and Frazer Islands, Gayndah, Kilcoy, Mount Brisbane, and Brisbane. When all turned up there numbered between 600 and 700 blacks. According to some people, the numbers would run to thousands at these feasts. That may have been so in other parts of the country, but not there on the Blackall Ranges. Each blackfellow belonging to the district had two or three trees which he considered his own property, and no one else was allowed to climb these trees and gather the cones, though all the guests would be invited to share equally in the eating of the nuts. The trees were handed down from father to son, as it were, and every one, of course, knew who were the owners.

Aboriginal baby

Great times those were, and what lots of fun these children of the woods had in catching paddymelons in the scrub with their nets, also in obtaining other food, of which there was plenty, such as opossums, snakes, and other animals, turkey eggs, wild yams, native figs, and a large white grub, which was found in dead trees. These latter are as thick as one's finger and about three inches long. They were very plentiful in the scrubs, and the natives knew at a glance where to look for them. They would eat these raw with great relish, as we do an oyster, or they would roast them. Then the young tops of the cabbage tree palm, and other palms which grew there, served as a sort of a vegetable, and were not bad, according to my father. The bon-yi nuts were generally roasted, the blacks preferring them so, but they were also-eaten raw.

It will be seen that there was no lack of food of different kinds during a bon-yi feast; the natives did not only live on nuts as some suppose. To them it was a real pleasure getting their food; they were so light-hearted and gay, nothing troubled them; they had no bills to meet or wages to pay. And there were no missionaries in those days to make them think how bad they were. Whatever their faults Father could not have been treated better, and when they came into camp of an afternoon about four o'clock, from all directions, laden with good things—opossums, carpet snakes, wild turkey eggs, and yams—he would get his share of the best—as much as he could eat. The turkey eggs were about the size of a goose egg, and the fresh ones were taken to the white boy, while addled eggs, or those (let me whisper it) with chickens in them, were eaten and relished by the blacks, after being roasted in the hot ashes.

My father always noticed how open-handed and generous the aborigines were. Some of us would do well to learn from them in that respect. If there were unfortunates who had been unlucky in the hunt for food, it made no difference; they did not go without, but shared equally with, the others.

It has often been given out as a fact that the blacks grew so tired of nuts and vegetable foods during a bon-yi feast that to satisfy the craving that grew upon them for animal food, they terminated the meeting by the sacrifice of one gin or more. This is quite untrue, according to my father. As I have shown, the blacks had plenty of variety in the way of food during these gatherings and, besides, on their way to the Bon-yi Mountains they travelled along the coast as much as was possible, and got fish and oysters as they went along. Then, after the feast was all over, they repaired again to the coast, where they lived for some time on the change of food.

The following passage from Dr. Lang's Queensland, issued in 1864, was quoted once by a gentleman (Mr. A. W. Howitt), who doubted its accuracy and wished my father's opinion on the subject:—

"At certain gatherings of some tribes of Queensland young girls are slain in sacrifice to propitiate some evil divinity, and their bodies likewise are subjected to the horrid rite of cannibalism. The young girls are marked out for sacrifice months before the event by the old men of the tribe."

Dr. Lang, says Mr. Howitt, gave this on the authority of his son, Mr. G. D. Lang, who, as the good doctor puts it, "happened to reside for a few months in the Wide Bay district."

My father says there is no truth in this statement; it is just hearsay, as there was no "such thing as sacrifice among the Queensland aborigines, neither did they ever kill any one for the purpose of eating them. They were most certainly cannibals, however, as they never failed to eat any one killed in fight, and always ate a man noted for his fighting qualities, or a "turrwan" (great man), no matter how old he was, or even if he died from consumption! It was very peculiar, but they said they did it out of pity and consideration for the body—they knew where he was then—"he won't stink!" The old tough gins had the best of it; no one troubled to eat them; their bodies weren't of any importance, and had no pity or consideration shown them! On the other hand, for the consumer's own benefit this time, a young, plump gin would always be eaten, or any one dying in good condition.

I do not mean to infer that the aborigines ate no human flesh during a bon-yi feast, for some one might die and be eaten at any time, and then, too, they always ended up with a big fight, and at least one combatant was sure to be killed. People speak of the great numbers killed in fight, but after all they were but few, though wounds, and big ones, too, were plentiful enough.

At night during the bon-yi season the blacks would have great corroborees, the different tribes showing their special corroboree (song and dance) to each other, so that they might all learn something fresh in that way. For instance, a Northern tribe would show theirs to a Southern one, and so on each night, till at last when they left to journey away again, they each had a fresh corroboree to take with them, and this they passed on in turn to a distant tribe. So from tribe to tribe a corroboree would go travelling for hundreds of miles both north and south, and this explains, I suppose, how it was that the aborigines would often sing songs, the words of which they did not understand in the least, neither could they tell you where they had first come from.

When about to have a corroboree, the women always got the fires ready, and the tribe wishing to show or teach their special corroboree to the others, would rig themselves out in full dress. This meant they had their bodies painted in different ways, and they wore various adornments, which were not used every day. Men always had their noses pierced (women never had), and it was considered a great thing to have a bone through one's nose! This bone was generally taken from a swan's wing, but it might be from a hawk's wing, or a small bone from the kangaroo's leg; and was supposed to be about four inches long. It was only worn during corroborees or fights, and was called the "buluwalam."

In every day life a man always wore a belt or "makamba," in which he carried his boomerang. This belt measured from six feet to eight feet in length, and was worn twisted round and round the waist. It was netted either from 'possum or human hair—but only the great men of the tribe wore human hair belts. A man could also wear "grass-bugle" necklaces ("kulgaripin") at any time; these being made from reeds cut into little pieces and strung together on a string of fibre. But in addition to his everyday dress, during a corroboree a blackfellow would wear round his forehead a band made from root fibre, very nicely plaited, and painted white with clay; also the skin of a native dog's tail (cured with charcoal and dried in the sun), or, rather, a part of one, for one tail made three headdresses when cut up the middle. This piece of tail stuck round the head like a beautiful yellow brush—the natives called it "gilla," and the forehead band "tinggil." Then on his arm kangaroo-skin bands were worn, and these had to be made from the underbody part of the skin, which was of a much lighter colour than the back. Lastly, a man was ornamented with swan's down stuck in his hair and beard, and in strips up and down his body and legs, back and front; or, if he was an inland black, parrot feathers took the place of the down.

Women wore practically no ornaments except necklaces, and feathers stuck in their short hair in bunches, with bees' wax. (The feathers and bees' wax were always ready in their dillies.) Their hair was always kept short, as they were apt to tear at each other when fighting. Men's hair grew long, and some of the great men had theirs tied up in a knob on the top of the head, and when such was the case they wore in this knob little sticks ornamented with yellow feathers from the cockatoo's topknot. The feathers were fastened to the ends of the sticks with bees' wax, and these sticks were stuck here and there in the knob of hair, as Japanese place little fans; and they looked quite nice.

When a good fire was raging the gins all sat in rows of three or four deep behind the fire. The old and married gins would have an opossum rug folded up between their thighs, which they beat with the palms of their hands, and so kept time with the song they sang. The young women beat time on their naked thighs. They held the left wrist with the right hand, and then, with the free hand open, slapped their thighs, making a wonderful noise and keeping excellent time. A pair of blackfellows standing up in front of the gins between them and the fire, would beat two boomerangs together, and these men were in "full dress," as were those who danced on the other side of the fire. First these latter stood some distance off in the dark, but so soon as the singing and beating of time began they would dance up to the others.

The men and women learning the corroboree stood behind the rows of gins seated on the ground, and two extra men, other than those with boomerangs, stood placed like sentinels before the women, with torches in their hands, and they were generally also strangers learning. The torches were fashioned from tea-tree bark, and made a splendid blaze, aiding the fire in its work of lighting up the dancers for the benefit of those concerned. Some few women would dance, but they kept rather apart in front of the others, and their movements were different to those of the men—somewhat stiffer. Always there were two or three funny men among the dancers, men who caused mirth and amusement by their antics—even the blacks had members who could "act the goat."

The aborigines painted their bodies according to the tribe to which they belonged, so in a corroboree or fight they were recognised at once by one another. In the former there would perhaps be ever so many different tribes mixed up, for they might all know the same dance. Father says it was a grand sight to see about 300 men at a time dancing in and out, painted all colours. There they would be, men white and black, men white and red, men white and yellow, and yet others a shiny black with just white spots all over them, or, in place of the spots, rings of white round legs and body, or white strips up and down. Yet again there were those who would have strange figures painted on their dark skins, and no matter which it was, one or the other, they were all neatly, and even beautifully, got up. There they would dance with their head-dress waving in the air—the swan's down, the parrot feathers, or the little sticks with the yellow cockatoo feathers. And, of course, the rest of the dress added to the spectacle—the native dogs' tails round their heads, the bones in their noses, and the various belts and other arrangements.

The dancers would keep up these gaieties for a couple of hours and then all would return to camp, where they settled down to a sort of meeting somewhat after the style of a Salvation Army gathering. One man would stand up and start a story or lecture of what had happened in his part of the country, speaking in a loud tone of voice, so that all could hear. When he had finished, another man from a different tribe stood forth and gave his descriptions, and so on till all the tribes had been represented. Then perhaps a man of one tribe would accuse one from another of being the cause of the death of a friend, and this would lead to a challenge and fight.

Things would be kept going sometimes up to midnight, when quiet reigned supreme again till the daybreak cry for the dead. And if this was a strange sound when two or three tribes were gathered together, what must it have been coming from all these many peoples assembled for a bon-yi feast. It would start perhaps by one old man wailing out, and then in another direction some one would answer, then another would take up the cry, and so on, till the different crying and chanting of all the different tribes rose on the air, with the loud "swears" and threats of what they would do when the enemy was caught, relieving the wailing, monotony.

So the days went on for a month or more, and the blacks employed their time in various ways; some would hunt, while others made weapons preparing for the great fight which always came off at the finish. When a time for this was fixed, all would repair to an open piece of country and there would keep the fight going for a week or so. Of the way this was managed I will speak another time.

At the finish of the great fight the tribes would start off homewards, parting the very best of friends with each other, and carrying large supplies of bon-yi nuts with them. The blacks of the district sought out a damp and boggy place—soft mud and water, with perhaps a spring—and buried their nuts there, placed in dilly-bags. Then off they went to the coast, living there on fish and crabs for the space of a month, when they returned and, digging up the nuts, had another feast, relishing them all the more no doubt because of the change to the seaside! The nuts when unearthed would have a disagreeable, musty smell, and would be all sprouting, but when roasted were improved greatly. The blacks from afar would also go to the coast if they had friends there who invited them, and they would be glad of a corroboree that took them seawards, if only for the one reason that they might have a change of food.

I omitted to mention that, on the way to these feasts, the blacks in those days would often catch emus in the vicinity of the Glass House Mountains, and also get their eggs. This my father knew from what was told him, though none were found when he accompanied them. The feathers, the gins used to stick in their hair on state occasions.

At any time when a certain tribe had learnt a new corroboree they would take the trouble to go even a long distance in order to pass it on. They first sent messengers—two men and their gins—to say they had learnt, or perhaps made, a fresh song and dance, and were coming to teach it. They would very likely stay a week and then go home again, or perhaps a number of tribes would all congregate. Father has seen about five hundred aborigines at a corroboree on Petrie's Creek, and they came from all parts—some from the far interior. Some of them there had never seen a boat before, and made a great wonder of it, looking it over and examining it everywhere.

Father knew an old Moreton Island man, a great character, head of that tribe, who was a good hand at making corroborees. He would disappear at times to a quiet part of the island (the others saying he had gone into the ground), and when he reappeared he had a fresh song and dance to impart. The blacks would sing sometimes of an incident which had happened, and in the dance make movements to carry out the song; for instance, if they sang of rowing they moved in the dance like an oarsman.

At times, if the words were decided upon, the whole tribe would suggest movements which best carried them out. One of the songs my father can sing was composed by a man at the Pine, and was based upon an incident which really happened. Father heard of the happening at the time, and afterwards learnt the corroboree. Here is the whole story:—

Three boats went out in winter time turtling from Coochi-mudlo Island ("Kutchi-mudlo"—red stone). It was after the advent of the whites, and the natives wanted the turtles for sale, not for their own use. In one of the boats was a man called Bobbiwinta, who was always successful in his ventures after turtle, being very good at diving, and clever in handling the creatures. Presently this boatload espied a turtle and gave chase, and whenever Bobbiwinta got a chance he jumped overboard, diving after it. However, it was an extra big one, and he could not manage to bring it up. Those watching above saw bubbles rise to the surface, and knew he was blowing beneath the water to cause the bubbles, so that some one would come down to his assistance. Two more men jumped in at this, and catching the turtle, they managed to turn him over, and bring him alongside the boat. Others in the boat got hold of the creature, and between them all it was hauled on board. Then the men in the water got in.

It was not till now, when the excitement was passed, that they found a man was missing—Bobbiwinta. All looked and could see him nowhere; men jumped overboard and searched, and the other boats coming up helped, but to no avail, he was gone. A great wailing and crying arose then, and by-and-bye a shark was seen floating quietly about, and all remaining hope went.

What seemed to strike the blacks was that they had seen no sign of the man, not even a particle of anything—it was such a complete disappearance. Natives are exceedingly tender-hearted in anything like this, and they were dreadfully cut up. Bobbiwinta's wife was in one of the boats. All camped that night at Kanaipa (towards the south end of Stradbroke), and next morning the beach was searched and searched, but nothing, not even a bone, was found.

The story of Bobbiwinta's mysterious disappearance was told from tribe to tribe; the natives seemed as though they could never get over the sadness of it. One night the man already mentioned belonging to the Pine was supposed to have had a dream, in which a corroboree came to him des-criptive of the event. The song ran as though the man from under the water, appealed for help—pitifully, pleadingly, all in vain. This corroboree was sung and danced everywhere, and years afterwards the mere mention of it was enough to cause tears and wailings. The words had this meaning: "My oar is bad, my oar is bad; send me my boat, I'm sitting here waiting," and so on, sung slowly. Then quickly, dulpai-i-la ngari kimmo-man" (jump over for me friends), and so to the finish. The following is the first portion of the song.

Another good corroboree was based on an incident which happened when my father was a boy. This time it had reference to a young gin—Kulkarawa—who belonged to the Brisbane or Turrbal tribe. A prisoner, a coloured man (an Indian), Shake Brown by name, stole a boat and, making off down the bay, took with him this Kulkarawa, without her people's immediate knowledge or consent. The boat was blown out to sea, and eventually the pair were washed ashore at Noosa Head—or as the blacks called it then, "Wantima," which meant "rising up," or "climbing up." They got ashore all right with just a few bruises, though the boat was broken to pieces. After rambling about for a couple of days, they came across a camp of blacks, and these latter took Kulkarawa from Shake Brown, saying that he must give her up, as she was a relative of theirs; but he might stop with them and they would feed him. So he stayed with them a long time, and the bon-yi season coming round, he accompanied them to the Blackall Range, joining in the feast there.

Before the bon-yi gathering had broken up, Shake Brown, grown tired of living the life of the blacks, left them to make his way to Brisbane. He got on to the old Northern Road going to Durundur, and followed it towards Brisbane. Coming at length to a creek which runs into the North Pine River, there, at the crossing, were a number of Turrbal blacks, who, recognising him, knew that he was the man who had stolen Kulkarawa. They asked what he had done with her, and he replied that the tribe of blacks he had fallen in with had taken her from him, and that she was now at the bon-yi gathering with them. But this, of course, did not satisfy the feeling for revenge that Shake Brown had roused when he took off the young gin from her people, and they turned on him and killed him, throwing his body into the bed of the creek at the crossing. A day or two later, men with a bullock dray going up to Durundur with rations, passing that way, came across Brown's body lying there, and they sent word to Brisbane, also christening the creek Brown's Creek, by which name it is known to this day.

Kulkarawa, living with the Noosa blacks, fretted for her people, and she made a song which ran as follows:

"Oh, flour, where oh where are you now that I used to eat? Oh, oh, take me back to my mother, there to be happy, and roam no more."

She evidently missed the flour which her own tribe got from the white people. The Noosa blacks made a dance to suit the song, and the corroboree was considered a grand one.

Kulkarawa, after living with the Noosa blacks for about two years, was at length brought back to her own people. Father happened to be out at the Bowen Hills or "Barrambin" camp, with two or three black boys, looking for some cows, at the time she arrived. The strange blacks bringing her, both went and sat down at the mother's hut without speaking, and the parents of the young gin, and all her friends, started crying for joy when they saw her, keeping the cry going for some ten minutes in a chanting sort of fashion, even as they do when mourning for the dead. Then a regular talking match ensued, and Kulkarawa was told all that had happened during her absence, including the finding and murder of Shake Brown (or "Marri-dai-o" the blacks called him), on his way to Brisbane. Then she told her news, and Father heard afterwards again from her own lips of her experiences.

The Noosa blacks introduced the corroboree at the "Barrambin" camp, and so it was sung and danced all round about, spreading both near and far.

In the song of a corroboree there were not generally many words, but these were repeated over and over again with different shades of expression. Once my father had the honour of being the subject of a corroboree; they sang of him as he was seen sailing with a native crew through the breakers over Maroochy Bar. The incident and its danger I will mention later. The song described the way he threw the surf from his face, etc. Who knows but what it lives somewhere yet, for it was possible for a corroboree to travel to the other end of the continent.

A Manila man (who afterwards died at Miora, Dunwich, and whose daughter lives there now) once taught a song he knew to the Turrbal blacks. They did not understand its meaning in the least, but learnt the words and the tune, and it became a great favourite with all. My father also picked it up when a boy, and it has since soothed to sleep in turn all his children and two grandchildren. Indeed Baby Armour (the youngest of the tribe) at one time refused to hear anything else when his mother sang to him. "Sing Mi-na" (Mee-na), he would say, if she dared try to vary the monotony. Here is the song (Music arranged by W. A. Ogg.):

In learning a fresh corroboree, some of the young fellows were very smart, and, as to going to a dance, they were just as keen about it as many white boys are.

Before going further, it is necessary for me to tell you something of a "turrwan" or "great man." Well, a "turrwan" was one who was supposed to be able to do anything. He could fly, kill, cure, or dive into the ground, and come out again where and when he liked; he could bring or stop rain, and so on—all by means of the "kundri," a small crystal stone, which he made the gins and others believe he carried about inside him, being able to bring it up at will by a string and swallow again! But my father has seen these stones, and they were really carried in small grass "dillys," under the arm, and were attached with bees' wax to a string made from opossum hair. These stones were generally obtained from deep pools, where they were dived for. The natives believed in a personality they called "Taggan" (inadvertently spelt "Targan" in Dr. Roth's Bulletin, No. 5), who seemed to be the spirit of the rainbow, and he it was who was responsible for these stones or crystals. Wherever the end of the rainbow touched the water, there they said crystals would be found—they knew where to dive for them.

Several men possessing these stones belonged to every tribe; they were never young men, but those who had been through many fights, and had had experience. Each one was noted for something special. For instance, one was a man who could bring thunder, another could cure, and so on. Whenever there was a storm or a flood, the aborigines always blamed a "turrwan" of another tribe for sending it. Supposing the storm came from the north, it was a turrwan from a tribe in the north who was responsible, or if from the south they blamed a southern tribe.

When any one was ill, he was taken to a "turrwan" to be cured, and the latter would make believe that he sucked a stone from the sick person's body, saying that was the cause of the mischief, another "turrwan" of another tribe having put it into him. For whenever any one was ill, no matter under what circumstances, a stranger "turrwan" (or rather his spirit) had most surely seen the afflicted one, and thrown the "kundri" at him. And a spirit could fly, and thus do damage on a man miles away. If found out too late nothing could save him.

Aborigines do not believe they ever die a natural death; death is always caused through a "turrwan" of another tribe. When a man dies, they think that at some previous time he has been killed before without its being known to any one, even himself. Verily a strange belief. They think he was killed with the "kundri" and cut up into pieces, then put together again; afterwards dying by catching a cold, or, perhaps, being killed in a fight. The man who killed him then is never blamed for the deed; "he had to die, you see!" But they blame a man from another tribe for the real cause of death, and do their best to be revenged; this causes all their big fights. They manage to decide on the murderer—how, I will tell you again.

If any one was ill in camp, and a falling star was seen, there would be a great crying and lamenting. To the natives it was a sign that the sick one was "doomed." The star was the fire stick of the turrwan, which he dropped as he flew away after doing the mischief.

Talking of how the aborigines regard death, brings us to their burial customs. Whenever the death of an aboriginal took place, all friends and relatives would gather together and cry, each man cutting his head with a tomahawk, or jobbing it with a spear, till the blood ran freely down his body, and the old women did the same thing with yam-sticks, while the young gins cut their thighs with sharp pieces of flint stone till their legs were covered with blood. In the meantime a couple of men would get some sheets of tea-tree bark on which to place the body, and if the corpse was not to be eaten, it would be wrapped up in this bark and tied round and round with string made from the inside of wattle bark. The feet were always left exposed. Then two old men would carry the body, those mourning following behind, continually crying all the time. You could hear their cry a long way off. They would go some distance till they came to a tree (generally in a gully out of sight) with a fork in the stem, six or eight feet from the ground. Here they would pause and seek about for two suitable forked sticks to match this tree, and these they fixed in the ground at a little distance from it, making the forks correspond in height with that of the tree. Next two sticks cut about seven feet long would be placed from the forked sticks to the tree fork, and from this three-cornered foundation a platform would be made with sticks put across and bound with the wattle-bark string. All being ready, the body would be lifted up on to this platform, which, without fail, would be made so that when the head was placed next the tree the feet would point always towards the west.

After this, a space in the ground underneath the body about four feet square would be cleared bare of grass, and at one side of it a small fire would be built. This was that the spirit of the dead man might come down in the night and warm himself at the fire, or cook his food. If the body was that of a man, a spear or waddy would be placed ready, so that the spirit might go hunting in the night; if a woman, then a yam-stick took the place of the other weapon, and her spirit could also hunt, or dig for roots. These weapons were left that the spirits might obtain food; it was not supposed that they would ever fight.

After finishing these preparations, the blacks would go away lamenting, and the body was left in peace. Then the day after burial—if it could be called burial—an old "turr-wan" would go without the knowledge of the others, back to where this platform stood erect with its burden, and stealthily he would print, on the cleared ground beneath, a mark like a footprint with the palm of his hand. After his departure, two women—old women (near relatives of the deceased, a mother and her sister if alive)—would appear on the scene. They, of course, would see this mark, and at once would imagine that the murderer had been there and left his footprint behind him. Strange to say, too, they would recognise to whom the footprint belonged! So back they went to the others, and told them all who was the murderer—it was generally some one they had a spite against in another tribe—and there would be no question or doubt.

After that no one went near the body till the flesh had dropped off, when two old women, relatives, again went, and, taking it down, they would proceed to separate the bones from each other. Certain of these were always religiously put aside and kept—they were the skull, leg, arm, and hip bones—while those of the ribs and back, etc., were burnt. The bones kept were put in a dilly, and so carried to the camp, and this dilly, with its sacred contents, accompanied the old woman relative on all her wanderings for months afterwards. In the meantime, however, the following happened:—

At the camp a fire would be made some fifty or one hundred yards from the huts, and all hands were called to come and witness the performance. The bones were cleaned and rubbed with charcoal, and one of the old gins who discovered the murderer's footmark would sit in the middle, the rest surrounding her, and she would take the hip bones and, with a stone tomahawk, would chop them, accompanying each chop with the name of some black of another tribe, sung in a chanting fashion. Now and again the bone would crack, and each time it did this the woman happened to call the name of the man she had told them of, who had left his footprint behind on the cleared ground, and the rest would exchange glances, saying he must be the guilty party.

Father has been present on these occasions, and the blacks would always draw his attention to the unquestionableness of the conclusion arrived at. Nothing could persuade them that it was not fair and, should they come across the poor unfortunate singled out, his death was a certainty. Perhaps some night he would be curled up asleep in the dark, when suddenly he was pounced upon and put out of existence; or perhaps he would be innocently engaged at some occupation when a dark form, sneaking up behind him, would send a spear through his skull, or otherwise do the deed. A death always roused great desire for revenge, and the friends of the deceased would watch and plan in every way till at last their end was accomplished. And even when revenged like this, many a big fight took place over a death. For the tribe to which the dead man had belonged would send a challenge to the tribe of the man held responsible for the deed, by two messengers, carrying a stick marked with notches cut in it. This stick served to show that there were a great number of blacks, and that they were in earnest. The messengers suggested a place of meeting for the fight, and after staying perhaps a week would return to their friends, who would look forward to the affray.

I have spoken of the blacks as cannibals, mentioning that it was only ordinary men and women of no condition who were buried. Here is how a cannibal feast would be proceeded with: First, the body was carried about a mile away from the camp, and there placed on sheets of tea-tree bark near a fire. I may mention that it was a practice with the aboriginal to keep his body (minus the head) free from hair, by singeing himself with a torch. It was similar to the habit of shaving. Should an aboriginal be unsinged he was unkempt, as a white man is who has not shaved. He could do his own arms and hands, etc., but would ask the assistance of others for the back. The singeing over, he rubbed his body with charcoal and grease, feeling then beautifully clean and nice. So perhaps it was this habit which made the aborigines singe their dead for the last time, before devouring them.