a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Auction Block Author: Rex Beach * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1900511h.html Language: English Date first posted: May 2019 Most recent update: May 2019 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Chapter 1.

Chapter 2.

Chapter 3.

Chapter 4.

Chapter 5.

Chapter 6.

Chapter 7.

Chapter 8.

Chapter 9.

Chapter 10.

Chapter 11.

Chapter 12.

Chapter 13.

Chapter 14.

Chapter 15.

Chapter 16.

Chapter 17.

Chapter 18.

Chapter 19.

Chapter 20.

Chapter 21.

Chapter 22.

Chapter 23.

Chapter 24.

Chapter 25.

Chapter 26.

Chapter 27.

Chapter 28.

Chapter 29.

Peter Knight flung himself into the decrepit arm-chair beside the center-table and growled:

“Isn’t that just my luck? And me a Democrat for twenty years. There’s nothing in politics, Jimmy.”

His son James smiled crookedly, with a languid tolerance bespeaking amusement and contempt. James prided himself upon his forbearance, and it was rarely indeed that he betrayed more than a hint of the superiority which he felt toward his parent.

“Politics is all right, provided you’re a good picker,” he said, with all the assurance of twenty-two, “but you fell off the wrong side of the fence, and you’re sore.”

“Of course I am. Wouldn’t anybody be sore?”

“These country towns always go in for the reform stuff, every so often. If you’d listen to me and—”

His father interrupted harshly: “Now, cut that out. I don’t want to go to New York, and I won’t.” Peter Knight tried to look forceful, but the expression did not fit his weak, complacent features. He was a plump man with red cheeks rounded by habitual good humor; his chin was short, and beneath it were other chins, distended and sagging as if from the weight of chuckles within. When he had succeeded in fixing a look of determination upon his countenance the result was an artificial scowl and a palpably false pout. Wearing such a front, he continued: “When I say ‘no’ I mean it, and the subject is closed. I like Vale, I know everybody here, and everybody knows me.”

“That’s why it’s time to move,” said Jim, with another unpleasant curl of his lip. “As long as they didn’t know you you got past. But you’ll never hold another office.”

“Indeed! My record’s open to inspection. I made the best sheriff in—”

“Two years. Don’t kid yourself, pa. Your foot slipped when the trolley line went through.”

“What do you know about the trolley line?” angrily demanded Mr. Knight.

“Well, I know as much as the county knows. And I know something about the big dam, too. You got into the mud, pa, but you didn’t go deep enough to find the frogs. Fogarty got his, didn’t he?”

Mr. Knight breathed deep with indignation.

“Senator Fogarty is my good friend. I won’t let you question his honor, although you do presume to question mine.”

“Of course he’s your friend; that’s why he’s fixed you for this New York job. He’s not like these Reubs; he remembers a good turn and blows back with another. He’s a real politician.”

“ ‘Department of Water Supply, Gas, and Electricity,’ ” sneered Peter. “It sounds good, but the salary is fifteen hundred a year. A clerk—at my age!”

“Say, d’you suppose Tammany men live on their salaries?” Jimmy inquired. “Wake up! This is your chance to horn into the real herd. In New York politics is a vocation; up here it’s a vacation—everybody tries it once, like music lessons. If you’d been hooked up with Tammany instead of the state machine you’d have been taken care of.”

“I tell you I don’t like cities. It’s no place to raise kids.”

At this James betrayed some irritation. “I’m of age, and Lorelei’s a grown woman. If we don’t get out of Vale I’ll still be a brakeman on a soda-fountain when I’m your age.”

“If you’d worked hard you’d have had an interest in the drug store now.”

“Rats!”

At this juncture Mrs. Knight, having finished the supper dishes and set her bread to rise, entered the shoddy parlor. Jim turned to her, shrugging his shoulders with an air of washing his hands of a disagreeable subject. “Pa’s weakened again,” he explained. “He won’t go.”

“Me, a clerk—at my age!” mumbled Peter.

“I’ve been trying to tell him that he’d get a half-Nelson on Tammany inside of a year. He squeezed the sheriff’s office till it squealed, and if he can pinch a dollar out of this burg he can—”

“You shut up! I don’t like your way of saying things,” snarled Mr. Knight.

His wife spoke for the first time, with brief conclusiveness.

“I wrote and thanked Senator Fogarty for his offer and told him you’d accept.”

“You—what?” Peter was dumfounded.

“Yes”—Mrs. Knight seemed oblivious of his wrath—“we’re going to make a change.”

Mrs. Knight was a large woman well advanced beyond that indefinite turning-point of middle age; in her unattractive face was none of the easy good nature so unmistakably stamped upon her husband’s. Peter J. was inherently optimistic; his head was forever hidden in a roseate aura of hopefulness and expectation. Under easy living he had grayed and fattened; his eyes were small and colorless, his cheeks full and veined with tiny sprays Of purple, his hands soft and limber. What had once been a measure of good looks was hidden now behind a flabby, indefinite mediocrity which an unusual carefulness in dress could not disguise. He was big-hearted in little things; in big things he was small. He told an excellent story, but never imagined one, and his laugh was hearty though insincere. Men who knew him well laughed with him, but did not indorse his notes.

His wife was of a totally different stamp, showing evidence of unusual force. Her thin lips, her clean-cut nose betokened purpose; a pair of alert, unpleasant eyes spoke of a mental activity that was entirely lacking in her mate, and she was generally recognized as the source of what little prominence he had attained.

“Yes, we’re going to make a change,” she repeated. “I’m glad, too, for I’m tired of housework.”

“You don’t have to do your own work. There’s Lorelei to help.”

“You know I wouldn’t let her do it.”

“Afraid it would spoil her hands, eh?” Mr. Knight snorted, disdainfully. “What are hands made for, anyhow? Honest work never hurt mine.”

Jim stirred and smiled; the retort upon his lips was only too obvious.

“She’s too pretty,” said the mother. “You don’t realize it; none of us do, but—she’s beautiful. Where she gets her good looks from I don’t know.”

“What’s the difference? It won’t hurt her to wash dishes. She wouldn’t have to keep it up forever, anyhow; she can have any fellow in the county.”

“Yes, and she’ll marry, sure, if we stay here.”

Knight’s colorless eyes opened. “Then what are you talking about going away to a strange place for? It ain’t every girl that can have her pick.”

Mrs. Knight began slowly, musingly: “You need some plain talk, Peter. I don’t often tell you just what I think, but I’m going to now. You’re past fifty; you’ve spent twenty years puttering around at politics, with business as a side issue, and what have you got to show for it? Nothing. The reformers are in at last, and you’re out for good. You had your chance and you missed it. You were always expecting something big, some fat office with big profits, but it never came. Do you know why? Because you aren’t big, that’s why. You’re little, Peter; you know it, and so does the party.”

The object of this address swelled pompously; his cheeks deepened in hue and distended; but while he was summoning words for a defense his wife ran on evenly:

“The party used you just as long as you could deliver something, but you’re down and out now, and they’ve thrown you over. Fogarty offers to pay his debt, and I’m not going to refuse his help.”

“I suppose you think you could have done better if you’d been in my place,” Peter grumbled. He was angry, yet the undeniable truth of his wife’s words struck home. “That’s the woman of it. You kick because we’re poor, and then want me to take a fifteen-hundred-dollar job.”

“Bother the salary! It will keep us going as long as necessary”

“Eh?” Mr. Knight looked blank.

“I’m thinking of Lorelei. She’s going to give us our chance.”

“Lorelei?”

“Yes. You wonder why I’ve never let her spoil her hands—why I’ve scrimped to give her pretty clothes, and taught her to take care of her figure, and made her go out with young people. Well, I knew what I was doing; it was part of her schooling. She’s old enough now; and she has everything that any girl ever had, so far as looks go. She’s going to do for us what you never have been and never will be able to do, Peter Knight. She’s going to make us rich. But she can’t do it in Vale.”

“Ma’s right,” declared James. “New York’s the place for pretty women; the town is full of them.”

“If it’s full of pretty women what chance has she got?” queried Peter. “She can’t break into society on my fifteen hundred—”

“She won’t need to. She can go on the stage.”

“Good Lord! What makes you think she can act?”

“Do you remember that Miss Donald who stopped at Myrtle Lodge last summer? She’s an actress.”

“No!” Mr. Knight was amazed.

“She told me a good deal about the show business. She said Lorelei wouldn’t have the least bit of trouble getting a position. She gave me a note to a manager, too, and I sent him Lorelei’s photograph. He wrote right back that he’d give her a place.”

“Really?”

“Yes; he’s looking for pretty girls with good figures. His name is Bergman.”

Jim broke in eagerly. “You’ve heard of Bergman’s Revues, pa. We saw one last summer, remember? Bergman’s a big fellow.”

“That show? Why, that was—rotten. It isn’t a very decent life, either.”

“Don’t worry about Sis,” advised Jim. “She can take care of herself, and she’ll grab a millionaire sure—with her looks. Other girls are doing it every day—why not her? Ma’s got the right idea.”

Impassively Mrs. Knight resumed her argument. “New York is where the money is—and the women that go with money. It’s the market-place. The stage advertises a pretty girl and gives her chances to meet rich men. Here in Vale there’s nobody with money, and, besides, people know us. The Stevens girls have been nasty to Lorelei all winter, and she’s never invited to the golf-club dances any more.”

At this intelligence Mr. Knight burst forth indignantly:

“They’re putting on a lot of airs since the Interurban went through; but Ben Stevens forgets who helped him get the franchise. I could tell a lot of things—”

“Bergman writes,” continued Mrs. Knight, “that Lorelei wouldn’t have to go on the road at all if she didn’t care to. The real pretty show-girls stay right in New York.”

Jim added another word. “She’s the best asset we’ve got, pa, and if we all work together we’ll land her in the money, sure.”

Peter Knight pinched his full red lips into a pucker and stared speculatively at his wife. It was not often that she openly showed her hand to him.

“It seems like an awful long chance,” he said.

“Not so long, perhaps, as you think,” his wife assured him. “Anyhow, it’s our only chance, and we’re not popular in Vale.”

“Have you talked to her about it?”

“A little. She’ll do anything we ask. She’s a good girl that way.”

The three were still buried in discussion when Lorelei appeared at the door.

“I’m going over to Mabel’s,” she paused a moment to say. “I’ll be back early, mother.”

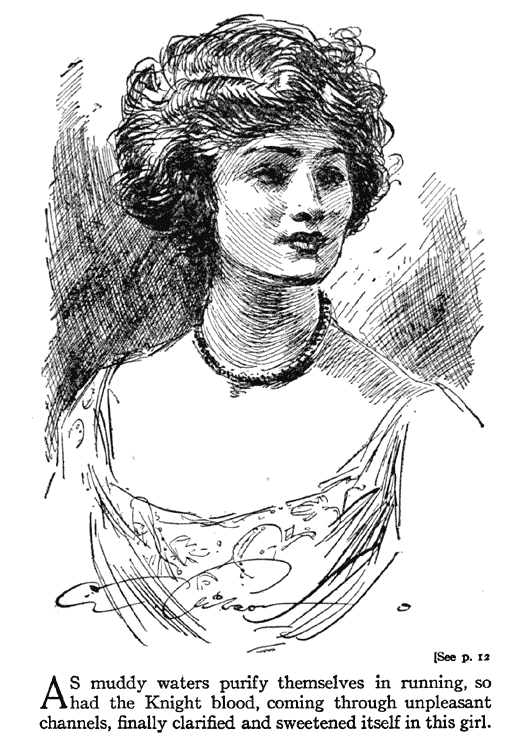

In Peter Knight’s eyes, as he gazed at his daughter, there was something akin to shame; but Jim evinced only a hard, calculating appraisal. Both men inwardly acknowledged that the mother had spoken less than half the truth, for the girl was extravagantly, bewitchingly attractive. Her face and form would have been noticeable anywhere and under any circumstances; but now in contrast with the unmodified homeliness of her parents and brother her comeliness was almost startling. The others seemed to harmonize with their drab surroundings, with the dull, unattractive house and its furnishings, but Lorelei was in violent opposition to everything about her. She wore her beauty unconsciously, too, as a princess wears the purple of her rank. Neither in speech nor in look did she show a trace of her father’s fatuous commonplaceness, and she gave no sign of her mother’s coldly calculating disposition. Equally the girl differed from her brother, for Jim was anemic, underdeveloped, sallow; his only mark of distinction being his bright and impudent eye, while she was full-blooded, healthy, and clean. Splendidly distinctive, from her crown of warm amber hair to her shapely, slender feet, it seemed that all the hopes, all the aspirations, all the longings of bygone generations of Knights had flowered in her. As muddy waters purify themselves in running, so had the Knight blood, coming through unpleasant channels, finally clarified and sweetened itself in this girl. In the color of her eyes she resembled neither parent; Mrs. Knight’s were close-set and hard; Peter’s shallow, indefinite, weak. Lorelei’s were limpid and of a twilight blue. Her single paternal inheritance was a smile perhaps a trifle too ready and too meaningless. Yet it was a pleasant smile, indicative of a disposition toward courtesy, if not self-depreciation.

But there all resemblance ceased. Lorelei Knight was mysteriously different from her kin; she might almost have sprung from a different strain, and except as one of those “throwbacks” which sometimes occur in a mediocre family, when an exotic offspring blooms like a delicate blossom in a bed of weeds, she was inexplicable. Simple living had made her strong, yet she remained exquisite; behind a natural and a deep reserve she was vibrant with youth and spirits.

In the doorway she hesitated an instant, favoring the group with her shadowy, impersonal smile. In her gaze there was a faint inquiry, for it was plain that she had interrupted a serious discussion. She came forward and rested a hand upon her father’s thinly haired bullet-head. Peter reached up and took it in his own moist palm.

“We were just talking about you,” he said.

“Yes?” The smile remained as the girl’s touch lingered.

“Your ma thinks I’d better accept that New York offer on your account.”

“On mine? I don’t understand.”

Peter stroked the hand in his clasp, and his weak, upturned face was wrinkled with apprehension. “She thinks you should see the world and—make something of yourself.”

“That would be nice.” Lorelei’s lips were still parted as she turned toward her mother in some bewilderment.

“You’d like the city, wouldn’t you?” Mrs. Knight inquired.

“Why, yes; I suppose so.”

“We’re poor—poorer than we’ve ever been. Jim will have to work, and so will you.”

“I’ll do what I can, of course; but—I don’t know how to do anything. I’m afraid I won’t be much help at first.”

“We’ll see to that. Now, run along, dearie.”

When she had gone Peter gave a grunt of conviction.

“She is pretty,” he acknowledged; “pretty as a picture, and you certainly dress her well. She’d ought to make a good actress.”

Jim echoed him enthusiastically. “Pretty? I’ll bet Bernhardt’s got nothing on her for looks. She’ll have a brownstone hut on Fifth Avenue and an air-tight limousine one of these days, see if she don’t.”

“When do you plan to leave?” faltered the father.

Mrs. Knight answered with some satisfaction: “Rehearsals commence in May.”

Mr. Campbell Pope was a cynic. He had cultivated a superb contempt for those beliefs which other people cherish; he rejoiced in an open rebellion against convention, and manifested this hostility in an exaggerated carelessness of dress and manner. It was perhaps his habit of thought as much as anything else that had made him a dramatic critic; but it was a knack for keen analysis and a natural, caustic wit that had raised him to eminence in his field. Outwardly he was a sloven and a misanthrope; inwardly he was simple and rather boyish, but years of experience in a box-office, then as advance man and publicity agent for a circus, and finally as a Metropolitan reviewer, had destroyed his illusions and soured his taste for theatrical life. His column was widely read; his name was known; as a prophet he was uncanny, hence managers treated him with a gingerly courtesy not always quite sincere.

Most men attain success through love of their work; Mr. Pope had become an eminent critic because of his hatred for the drama and all things dramatic. Nor was he any more enamoured of journalism, being in truth by nature bucolic, but after trying many occupations and failing in all of them he had returned to his desk after each excursion into other fields. First-night audiences knew him now, and had come to look for his thin, sharp features. His shapeless, wrinkled suit that resembled a sleeping-bag; his flannel shirt, always tieless and frequently collarless, were considered attributes of genius; and, finding New York to be amazingly gullible, he took a certain delight in accentuating his eccentricities. At especially prominent premieres he affected a sweater underneath his coat, but that was his nearest approach to formal evening dress. Further concession to fashion he made none.

Owing to the dearth of new productions this summer, Pope had undertaken a series of magazine articles descriptive of the reigning theatrical beauties, and, while he detested women in general and the painted favorites of Broadway in particular, he had forced himself to write the common laudatory stuff which the public demanded. Only once had he given free rein to his inclinations and written with a poisoned pen. To-night, however, as he entered the stage door of Bergman’s Circuit Theater, it was with a different intent.

Regan, the stage-door tender, better known since his vaudeville days as “The Judge,” answered his greeting with a lugubrious shake of a bald head.

“I’m a sick man, Mr. Pope. Same old trouble.”

“M-m-m. Kidneys, isn’t it?”

“No. Rheumatism. I’m a beehive swarmin’ with pains.”

“To be sure. It’s Hemphill, the door-man at the Columbus, who has the floating kidney. I paid for his operation.”

“Hemphill. Operation! Ha!” The Judge cackled in a voice hoarse from alcoholic excesses. “He bilked you, Mr. Pope. He’s the guy that put the kid in kidney. There’s nothing wrong with him. He could do his old acrobatic turn if he wanted to.”

“I remember the act.”

“Me an’ Greenberg played the same bill with him twenty years ago.” The Judge leaned forward, and a strong odor of whisky enveloped the caller. “Could you slip me four bits for some liniment?”

The critic smiled. “There’s a dollar, Regan. Try Scotch for a change. It’s better for you than these cheap blends. And don’t breathe toward a lamp, or you’ll ignite.”

The Judge laughed wheezingly. “I do take a drop now and then.”

“A drop? You’d better take a tumble, or Bergman will let you out.”

“See here, you know all the managers, Mr. Pope. Can’t you find a job for a swell dame?” the Judge inquired, anxiously.

“Who is she?”

“Lottie Devine. She’s out with the ‘Peach Blossom Girls.’ ”

“Lottie Devine. Why, she’s your wife, isn’t she?”

“Sure, and playing the ‘Wheel’ when she belongs in musical comedy. She dances as good as she did when we worked together—after she gets warmed up—and she looks great in tights—swellest legs in burlesque, Mr. Pope. Can’t you place her?”

“She’s a trifle old, I’m afraid.”

“Huh! She wigs up a lot better’n some of the squabs in this troupe. Believe me, she’d fit any chorus.”

“Why don’t you ask Bergman?”

Mr. Regan shook his hairless head. “He’s dippy on ‘types.’ This show’s full of ’em: real blondes, real brunettes, bold and dashin’ ones, tall and statelies, blushers, shrinkers, laughers, and sadlings. He won’t stand for make-up; he wants ’em with the dew on. They’ve got to look natural for Bergman. That’s some of ’em now.” He nodded toward a group of young, fresh-cheeked girls who had entered the stage door and were hurrying down the hall. “There ain’t a Hepnerized ensemble in the whole first act, and they wear talcum powder instead of tights. It’s dimples he wants, not ‘fats.’ How them girls stand the draught I don’t know. It would kill an old-timer.”

“I’ve come to interview one of Bergman’s ‘types’; that new beauty, Miss Knight. Is she here yet?”

“Sure; her and the back-drop, too. She carries the old woman for scenery.” Mr. Regan took the caller’s card and shuffled away, leaving Pope to watch the stream of performers as they entered and made for their quarters. There were many women in the number, and all of them were pretty. Most of them were overdressed in the extremes of fashion; a few quietly garbed ladies and gentlemen entered the lower dressing-rooms reserved for the principals.

It was no novel sight to the reviewer, whose theatrical apprenticeship had been thorough, yet it never failed to awaken his deepest cynicism. Somewhere within him was a puritanical streak, and he still cherished youthful memories. He reflected now that it was he who had laid the foundation for the popularity of the girl he had come to interview; for he had picked her out of the chorus of the preceding Revue and commented so enthusiastically upon her beauty that this season had witnessed her advancement to a speaking part. Through Pope’s column attention had been focused upon Bergman’s latest acquisition; and once New York had paused to look carefully at this fresh young new-comer, her fame had spread. But he had never met the girl herself, and he wondered idly what effect success had had upon her. A total absence of scandal had argued against any previous theatrical experience.

Meanwhile he exchanged greetings with the star—a clear-eyed man with the face of a scholar and the limbs of an athlete. The latter had studied for the law; he had the drollest legs in the business, and his salary exceeded that of Supreme Court Justice. They were talking when Mr. Regan returned to tell the interviewer that he would be received.

Pope followed to the next floor and entered a brightly lighted, overheated dressing-room, where Lorelei and her mother were waiting. It was a glaring, stuffy cubbyhole ventilated by means of the hall door and a tiny window opening from the lavatory at the rear. Along the sides ran mirrors, beneath which was fixed a wide make-up shelf. From the ceiling depended several unshaded incandescent globes which flooded the place with a desert heat and radiance. An attempt had been made to give the room at least a semblance of coolness by hanging an attractively figured cretonne over the entrance and over the wardrobe hooks fixed in the rear wall; but the result was hardly successful. The same material had been utilized to cover the shelves which were littered with a bewildering assortment of make-up tins, cold-cream cans, rouge and powder boxes, whitening bottles, wig-blocks, and the multifarious disordered accumulations of a dressing-room. The walls were half hidden behind photographs, impaled upon pins, like entomological specimens; photographs were thrust into the mirror frames, they were propped against the heaps of tins and boxes or hidden beneath the confusion of toilet articles. But the collection was not limited to this variety of specimen. One section of the wall was devoted to telegraph and cable forms, bearing messages of felicitation at the opening of “The Revue of 1913.” A zoologist would have found the display uninteresting; but a society reporter would have reveled in the names—and especially in the sentiments—inscribed upon the yellow sheets. Some were addressed to Lorelei Knight, others to Lilas Lynn, her roommate.

Pope found Lorelei completely dressed, in expectation of his arrival. She wore the white and silver first-act costume of the Fairy Princess. Both she and her mother were plainly nonplussed at the appearance of their caller; but Mrs. Knight recovered quickly from the shock and said agreeably:

“Lorelei was frightened to death at your message yesterday. She was almost afraid to let you interview her after what you wrote about Adoree Demorest.”

Pope shrugged. “Your daughter is altogether different to the star of the Palace Garden, Mrs. Knight. Demorest trades openly upon her notoriety and—I don’t like bad women. New York never would have taken her up if she hadn’t been advertised as the wickedest woman in Europe, for she can neither act, sing, nor dance. However, she’s become the rage, so I had to include her in my series of articles. Now, Miss Knight has made a legitimate success as far as she has gone.”

He turned to the girl herself, who was smiling at him as she had smiled since his entrance. He did not wonder at the prominence her beauty had brought her, for even at this close range her make-up could not disguise her loveliness. The lily had been painted, to be sure, but the sacrilege was not too noticeable; and he knew that the cheeks beneath their rouge were faintly colored, that the lashes under the heavy beading were long and dark and sweeping. As for her other features, no paint could conceal their perfection. Her forehead was linelessly serene, her brows were straight and too well-defined to need the pencil. As for her eyes, too much had been written about them already; they had proven the despair of many men, or so rumor had it. He saw that they had depths and shadows and glints of color that he could not readily define. Her nose, pronounced perfect by experts on noses, seemed faultless indeed. Her mouth was no tiny cupid’s bow, but generous enough for character. Of course, the lips were glaringly red now, but the expression was none the less sweet and friendly.

“There’s nothing ‘legitimate’ about musical shows,” she told him, in reply to his last remark, “and I can’t act or sing or dance as well as Miss Demorest.”

“You don’t need to; just let the public rest its eyes on you and it will be satisfied—anyhow, it should be. Of course, everybody flatters you. Has success turned your head?”

Mrs. Knight answered for her daughter. “Lorelei has too much sense for that. She succeeded easily, but she isn’t spoiled.”

Then, in response to a question by Pope, Lorelei told him something of her experience. “We’re up-state people, you know. Mr. Bergman was looking for types, and I seemed to suit, so I got an engagement at once. The newspapers began to mention me, and when he produced this show he had the part of the Fairy Princess written in for me. It’s really very easy, and I don’t do much except wear the gowns and speak a few lines.”

“You’re one of the principals,” her mother said, chidingly.

“I suppose you’re ambitious?” Pope put in.

Again the mother answered. “Indeed she is, and she’s bound to succeed. Of course, she hasn’t had any experience to speak of, but there’s more than one manager that’s got his eye on her.” The listener inwardly cringed. “She could be starred easy, and she will be, too, in another season.”

“Then you must be studying hard, Miss Knight?”

Lorelei shook her head.

“Not even voice culture?”

“No.”

“Nor dancing? Nor acting?”

“No.”

“She has so little time. You’ve no idea how popular she is,” twittered Mrs. Knight.

Pope fancied the girl herself flushed under his inquiring eye; at any rate, her gaze wavered and she seemed vexed by her mother’s explanation. He, too, resented Mrs. Knight’s share in the conversation. He did not like the elder woman’s face, nor her voice, nor her manner. She impressed him as another theatrical type with which he was familiar—the stage mama. He found himself marveling at the dissimilarity of the two women.

“Of course, a famous beauty does meet a lot of people,” he said. “Tell me what you think of our nourishing little city and our New York men.”

But Lorelei raised a slender hand.

“Not for worlds. Besides, you’re making fun of me now. I was afraid to see you, and I’d feel terribly if you printed anything I really told you. Good interviewers never do that. They come and talk about nothing, then go away and put the most brilliant things into your mouth. You are considered a very dangerous person, Mr. Pope.”

“You’re thinking of my story about that Demorest woman again,” he laughed.

“Is she really as bad as you described her?”

“I don’t know, never having met the lady. I wouldn’t humiliate myself by a personal interview, so I built a story on the Broadway gossip. Inasmuch as she goes in for notoriety, I gave her some of the best I had in stock. Her photographer did the rest.”

The door curtains parted, and Lilas Lynn, a slim, black-eyed young woman, entered. She greeted Pope cordially as she removed her hat and handed it to the woman who acted as dresser for the two occupants of the room.

“I’m late, as usual,” she said. “But don’t leave on my account.” She disappeared into the lavatory, and emerged a moment later in a combing-jacket; seating herself before her own mirrors, she dove into a cosmetic can and vigorously applied a priming coat to her features, while the dresser drew her hair back and secured it tightly with a wig-band. “Lorelei’s got her nerve to talk to you after the panning you gave Demorest,” she continued. “Aren’t you ashamed of yourself to strike a defenseless star?”

Pope nodded. “I am, and I’m ashamed of my entire sex when I hear of them flocking to the Palace Garden just to see a woman who has nothing to distinguish her but a reputation for vileness.”

“Did you see the crown jewels—the King’s Cabachon rubies?” Lorelei asked.

“Only from the front. I dare say they’re as counterfeit as she is.”

Miss Lynn turned, revealing a countenance as shiny as that of an Eskimo belle. With her war-paint only half applied and her hair secured closely to her small head, she did not in the least resemble the dashing “Countess” of the program.

“Oh, they’re real enough. I got that straight.”

Campbell Pope scoffed.

“Isn’t it true about the King of Seldovia? Didn’t she wreck his throne?” eagerly queried Mrs. Knight.

“I never met the King, and I haven’t examined his throne. But, you know, kings can do no wrong, and thrones are easily mended.”

But Mrs. Knight was insistent; her eyes glittered, her sharp nose was thrust forward inquisitively. “They say she draws two thousand a week, and won’t go to supper with a man for less than five hundred dollars. She says if fellows want to be seen in public with her they’ll have to pay for it, and she’s right. Of course, she’s terribly bad, but you must admit she’s done mighty well for herself.”

“We’ll have a chance to see her to-night,” announced Lilas. “Mr. Hammon is giving a big supper to some of his friends and we’re going—Lorelei and I. Demorest is down for her ‘Danse de Nuit.’ They say it’s the limit.”

“Hammon, the steel man?” queried the critic, curiously.

“Sure. There’s only one Hammon. But nix on the newspaper story; this is a private affair.”

“Never let us speak ill of a poor Pittsburgh millionaire,” laughed Pope. “Scandal must never darken the soot of that village.” He turned as Slosson, the press-agent of the show, entered with a bundle of photographs.

“Here are the new pictures of Lorelei for your story, old man,” Mr. Slosson said. “Bergman will appreciate the boost for one of his girls. Help yourself to those you want. If you need any more stuff I’ll supply it. Blushing country lass just out of the alfalfa belt—first appearance on any stage—instantaneous hit, and a record for pulchritude in an aggregation where the homeliest member is a Helen of Troy. Every appearance a riot; stage-door Johns standing on their heads; members of our best families dying to lead her to the altar; under five-year contract with Bergman, and refuses to marry until the time’s up. Delancey Page, the artist, wants to paint her, and says she’s the perfect American type at last. Say, Bergman can certainly pick ’em, can’t he? I’ll frame it for a special cop at the back door, detailed to hold off the matrimony squad of society youths, if you can use it.”

“Don’t go to the trouble,” Pope hastily deprecated. “I know the story. Now I’m going to leave and let Miss Lynn dress.”

“Don’t go on my account,” urged Lilas. “This room is like a subway station, and I’ve got so I could ‘change’ in Bryant Park at noon and never shock a policeman.”

“You won’t say anything mean about us, will you?” Mrs. Knight implored. “In this business a girl’s reputation is all she has.”

“I promise.” Pope held out his hand to Lorelei, and as she took it her lips parted in her ever-ready smile. “Nice girl, that,” the critic remarked, as he and Slosson descended the stairs.

“Which one—Lorelei, Lilas, or the female gorilla?”

“How did she come to choose that for a mother?” muttered Pope.

“One of Nature’s inscrutable mysteries. But wait. Have you seen brother Jim?”

“No. Who’s he?”

“His mother’s son. Need we say more? He’s a great help to the family, for he keeps ’em from getting too proud over Lorelei. He sells introductions to his sister.”

Campbell Pope’s exclamation was lost in a babble of voices as a bevy of “Swimming Girls” descended from the enchanted regions above and scurried out upon the stage. Through the double curtain the orchestra could be faintly heard; a voice was crying, “Places.”

“Some Soul Kissers with this troupe, eh?” remarked Slosson, when the scampering figures had disappeared.

“Yes. Bergman has made a fortune out of this kind of show. He’s a friend to the ‘Tired Business Man.’ ”

“Speaking of the weary Wall Street workers, there will be a dozen of our ribbon-winners at that Hammon supper to-night. Twelve ‘Bergman Beauties.’ Twelve; count ’em! Any time you want to pull off a classy party for some of your bachelor friends let me know, and I’ll supply the dames—at one hundred dollars a head—and guarantee their manners. They’re all trained to terrapin, and know how to pick the proper forks.”

“One hundred? Last season a girl was lucky to get fifty dollars as a banquet favor; but the cost of living rises nightly. No wonder Hammon’s against the income tax.”

“Yes, and that’s exclusive of the regulation favors. There’s a good story in this party if you could get the men’s names.”

Pope’s thin lip curled, and he shook his head.

“I write theatrical stuff,” he said, shortly, “because I have to, not because I like to. I try to keep it reasonably clean.”

Slosson was instantly apologetic. “Oh, I don’t mean there’s anything wrong about this affair. Hammon is entertaining a crowd of other steel men, and a stag supper is either dull or devilish, so he has invited a good-looking partner for each male guest. It’ll be thoroughly refined, and it’s being done every night.”

“I know it is. Tell me, is Lorelei Knight a regular—er—frequenter of these affairs?”

“Sure. It’s part of the graft.”

“I see.”

“She has to piece out her salary like the other girls. Why, her whole family is around her neck—mother, brother, and father. Old man Knight was run over by a taxi-cab last summer. It didn’t hurt the machine, but he’s got a broken back, or something. Too bad it wasn’t brother Jimmy. You must meet him, by the way. I never heard of Lorelei’s doing anything really—bad.”

For the moment Campbell Pope made no reply. Meanwhile a great wave of singing flooded the regions at the back of the theater as the curtain rose and the chorus broke into sudden sound. When he did speak it was with unusual bitterness.

“It’s the rottenest business in the world, Slosson. Two years ago she was a country girl; now she’s a Broadway belle. How long will she last, d’you think?”

“She’s too beautiful to last long,” agreed the press-agent, soberly, “especially now that the wolves are on her trail. But her danger isn’t so much from the people she meets with as the people she eats with. That family of hers would drive any girl to the limit. They intend to cash in on her; the mother says so.”

“And they will, too. She can have her choice of the wealthy rounders.”

“Don’t get me wrong,” Slosson hastened to qualify. “She’s square; understand?”

“Of course; ‘object, matrimony.’ It’s the old story, and her mother will see to the ring and the orange blossoms. But what’s the difference, after all, Slosson? It’ll be hell for her, and a sale to the highest bidder, either way.”

“Queer little gink,” the press-agent reflected, as he returned to the front of the house. “I wish he wore stiff collars; I’d like to take him home for dinner.”

As Pope passed out through the stage door the Judge called hoarsely after him:

“You’ll keep your eye skinned for a job for Lottie, won’t you? Remember, the swellest legs in burlesque.”

In his summary of Lorelei’s present life Slosson had not been far wrong. Many changes had come to the Knights during the past two years—changes of habit, of thought, and of outlook; the entire family had found it necessary to alter their system of living. But it was in the girl that the changes showed most. When Mrs. Knight had forecast an immediate success for her daughter she had spoken with the wisdom of a Cassandra. Bergman had taken one look at Lorelei upon their first meeting, then his glance had quickened. She had proved to have at least an average singing-voice; her figure needed no comment. Her inexperience had been the strongest argument in her favor, since Bergman’s shows were famous for their new faces. The result was that he signed her promptly, and mother and daughter had walked out of his office quite unconscious of having accomplished the unusual. At first the city had seemed strange and bewildering, and Lorelei had suffered pangs at the memory of Vale, for at her age the roots of association strike deep; but in a short time the novelty of her new life proved an anodyne and deadened acute regrets, while the vague hazard of it all kept her at an agreeable pitch of excitement.

Moreover, she took naturally to the work, finding it more like play; and, being quite free from girlish timidity, she felt no stage-fright, even upon her first appearance. Her recognition had followed quickly—it was impossible to hide such perfection of loveliness as hers—and the publicity pleased her. In due course rival managers began to make offers, which Mrs. Knight, rising nobly to the first test of her business ability, used as levers to raise her daughter’s salary and to pry out of Bergman a five-year contract. The role of the Fairy Princess was a result.

Thus it was that without conscious effort, without even a proof of merit beyond her appearance, Lorelei had arrived at the point where further advancement depended upon study and hard work; but, since these formed no part of the family program, she remained idle while Mrs. Knight and Jim arranged so many demands upon her time that she had no leisure for serious endeavors, even had she desired it. Proficiency in stage-craft of any sort comes only at the expense of peonage, and this girl was being groomed solely for matrimony.

The principals who topped the Bergman bill were artists—men and women who had climbed through years of patient effort; toward their subordinates they maintained an aloofness that is peculiar to the show business. They moved in a world apart from the chorus: the two classes impinged briefly eight times a week, but outside the theater they never saw each other. Even Labaudie, the doll-like danseuse, looked down upon Lorelei and Lilas almost as she looked down upon the members of her ballet. Out of all the big company there were perhaps a half-dozen chorus men and women who had eyes definitely fixed upon a stage career; the rest, like Lorelei and Lilas, regarded the work simply as an easy means of livelihood.

The theatrical profession is peculiar to itself. It is a world with customs, habits, and ambitions differing from those of any other sphere. That division of stage life to which Lorelei Knight belonged—that army of men and women from shows like Bergman’s—constitutes a still more distinctive community—a community, moreover, that is characteristic of New York alone. Its code is of its own making; its habits of life are as individual as its figures of speech. Although at first all this bewildered the country girl, at length she had come to adopt the new ways as a matter of course. From the association she had learned much. She had learned how to reap the fruits of popularity, how to take without giving, how to profit without sacrifice; and under her mother’s influence she was not allowed to forget what she had learned.

With the support of the family entirely upon her shoulders, she had been driven to many shifts in order to stretch her salary to livable proportions. Peter was a total burden, and Jim either refused or was unable to contribute toward the common fund, while the mother devoted her time almost solely to managing Lorelei’s affairs. Presents were showered upon the girl, and these Mrs. Knight converted into cash. Conspicuous stage characters are always welcome at the prominent cafes; hence Lorelei never had to pay for food or drink when alone, and when escorted she received a commission on the money spent. She was well paid for posing, advertisements of toilet articles, face creams, dentifrices, and the like, especially if accompanied by testimonials, yielded something. In the commercial exploitation of her daughter Mrs. Knight developed something like genius. She arranged for paid interviews and special beauty articles in the Sunday supplements; she saw to it that Lorelei’s features became identified with certain makes of biscuits, petticoats, chewing-gums, chocolates, cameras, short-vamp shoes, and bath-tubs. But of all the so-called “grafts” open to handsome girls in her business the quickest and best returns came from prodigal entertainers like Jarvis Hammon.

As Lorelei and her companion left their taxi-cabs and entered Proctor’s Hotel, shortly before midnight, they were met by a head waiter and shown into an ornate ivory-and-gold elevator which lifted them noiselessly to an upper floor. They made their exit into a deep-carpeted hall, at the end of which two splendid creatures in the panoply of German field-marshals stood guard over one of the smaller banquet-rooms.

Hammon himself greeted the girls when they had surrendered their wraps, and, after his introduction to Lorelei, engaged Lilas in earnest conversation.

Lorelei watched him curiously. She saw a powerfully built gray-haired man, whose vigor age had not impaired. In face he was perhaps fifty years old, in body he was much less. He was the typical forceful New York man of affairs, carefully groomed, perhaps a little inclined to stoutness. By this time millionaires had lost their novelty for the girl. She had met some who were more distinguished in appearance than this man, but never one who seemed possessed of more nervous energy and virility. Jarvis Hammon had a bold, incisive manner that was compelling and stamped him as a big man in more ways than one. Playfully he pinched Lilas’s cheek, then turned with a smile to say:

“You’ll pardon us for whispering, won’t you, Miss Knight? You see, Lilas got up this little party, and I’ve been waiting to consult her about some of the details. Of course, she was late, as usual. However”—he ran an admiring eye over the two girls—“the time wasn’t wasted, I see. My! How lovely you both look!”

Taking an arm of each, he swept them toward a reception-room from which issued noisy laughter.

“Awfully good of you to come, Miss Knight. I hope you’ll find my friends agreeable and enjoy yourself.”

Perhaps twenty men in evening dress and as many elaborately gowned young women were gossiping and smoking as the last comers appeared. Some one raised a vigorous complaint at the host’s tardiness, but Hammon laughed a rejoinder, then gave a signal, whereupon folding-doors at the end of the room were thrown back. From within an orchestra struck up a popular rag-time air, and those nearest the banquet-hall moved toward it. A girl whom Lorelei recognized as a fellow-member of the Revue danced up to her escort with arms extended, and the two turkey-trotted into the larger room.

Hammon was introducing two of his friends—one a languid, middle-aged man who was curled up in a deep chair with a cigarette between his fingers; the other a large-featured person with a rumbling voice. The men had been arguing earnestly, oblivious of the confusion around them; but now the former dropped his cigarette, uncoiled his long form, and, rising, bowed courteously. His appearance as he faced Lorelei was prepossessing, and she breathed a thanksgiving as she took his arm.

Hammon clapped the other gentleman upon the shoulder, crying: “The rail market will take care of itself until to-morrow, Hannibal. What is more to the point, I saw your supper partner flirting with ‘Handsome Dan’ Avery. Better find her quick.”

Lorelei recognized the deep-voiced man as Hannibal C. Wharton, one of the dominant figures in the Steel Syndicate; she knew him instantly from his newspaper pictures. The man beside her, however, was a stranger, and she raised her eyes to his with some curiosity. He was studying her with manifest admiration, despite the fact that his lean features were cast in a sardonic mold.

“It is a pleasure to meet a celebrity like you, Miss Knight,” he murmured. “All New York is at your feet, I understand. I’m deeply indebted to Hammon. Blessings on such a host!”

“Oh, don’t be hasty. You may dislike me furiously before the evening is over. He does things in a magnificent way, doesn’t he? I’m sure this is going to be a splendid party.”

As they entered the banquet-hall she gave a little cry of pleasure, for it was evident that Hammon, noted as he was for a lavish expenditure, had outdone himself this time. The whole room had been transformed into a bower of roses, great, climbing bushes, heavy with blooms; masses of cool, green ivy hid the walls from floor to ceiling and were supported upon cunningly wrought trellises through which hidden lights glowed softly. In certain nooks gleamed marble statuettes so placed as to heighten the effect of space and to carry out the idea of a Roman garden.

The table, a horseshoe of silver and white, of glittering plate and sparkling cut-glass, faced a rustic stage which occupied one end of the room; occupying the inner arc of the half-circle was a wide but shallow stone fountain, upon the surface of which floated large-leaved Egyptian pond-lilies. Fat-bellied goldfish with filmy fins, and tails like iridescent wedding trains, propelled themselves indolently about. Two dimpled cupids strained at a marble cornucopia, out of which trickled a stream of water, its whisper drowned now by the noisy admiration of the guests.

But the surprising feature of the decorating scheme was not apparent at first glance. Through the bewildering riot of greenery had been woven an almost invisible netting, and the space behind formed a prison for birds and butterflies. Where they had come from or at what expense they had been procured it was impossible to conceive. But, disturbed by the commotion, the feathered creatures twittered and fluttered against the netting in a panic which drew attention to them even if it did not wholly convey the illusion of a woodland scene. As for the butterflies, no artificial light could deceive them, and they clung with closed wings to leaves and branches, only now and then displaying their full glory in a sleepy protest. There were scores, hundreds of them, and the diners passed in review of the spectacle like country visitors before the glass tanks of the Aquarium. A strident shriek sounded as a gorgeously caparisoned peacock preened himself; others were discovered here and there, brilliant-hued specimens, voicing shrill indignation.

“How—beautiful!” gasped Lorelei, when she had taken in the whole scene. “But—the poor little things are frightened.” She looked up to find her companion staring in Hammon’s direction with an expression of peculiar, derisive amusement.

Hammon was the center of an admiring group; congratulations were being hurled at him from every quarter. At his side was Lilas Lynn, very dark, very striking, very expensively gowned, and elaborately bejeweled. The room was dinning with the strains of an invisible orchestra and the vocal uproar; topping the confusion came shrieks from the excitable peacocks; the wild birds twittered and beat themselves affrightedly against the netting.

Becoming conscious of Lorelei’s gaze, her escort looked down, showing his teeth in a grin that was not of pleasure.

“You like it?” he asked.

“It’s beautiful, but—the extravagance is almost criminal.”

“Don’t tell me how many starving newsboys or how many poor families the cost of this supper would support for a year. I hate poor people. I like to see ’em starve. If you fed them this year they’d starve next, so—what’s the difference? Nevertheless, Jarvis has surprised me.” He paused, and his eyes, as he stared again at the steel magnate, were mocking. “You’ll admit it was a dazzling idea—coming from a rolling-mill boss. Now for the ortolans and the humming-bird tongues. No doubt there’s a pearl in every wine-cup. Prepare to have your palate tickled with a feather when your appetite flags.”

“That’s what the Romans did, isn’t it?”

“Ah, you are a student as well as an artist, Miss Knight.”

“I thought you were going to be pleasant, but you’re not, are you?” Lorelei was smiling fixedly.

“No, quite the opposite. Thank God, I’m a dyspeptic.”

“Then why did you come here?”

“Why did those birds come? Why did you come?”

“Oh, we—the birds and I—are merely decorations—something to add to the rich man’s gaiety. But I’m afraid you don’t intend to have a good time, Mr.—” They had found their places at the table, and Lorelei’s escort was seating her. “I didn’t catch your name when we were introduced.”

“Nor I,” said he, taking his place beside her. “It sounded like Rice Curry or some other damnable dish, but it’s really Merkle—John T. Merkle.”

“Ah! You’re a banker. Aren’t you pretty—reckless confessing your rank, as it were?”

“I’m a bachelor; also an invalid and an insomniac. You couldn’t bring me any more trouble than I have.”

“You are unpleasant.”

“I’m famous for it. Being the only bachelor present, I claim the privilege of free speech.” Again he looked toward Hammon, and this time he frowned. “From indications I’ll soon have company, however.”

“Indeed. Is there talk of a divorce there?” She inclined her head in the host’s direction.

Merkle retorted acidly: “My dear child, don’t try to act the ingenue. You’re in the same show as Miss Lynn, and you must know what’s going on. This sort of thing can’t continue indefinitely, for Mrs. Hammon is very much alive, to say nothing of her daughters. I dare say they’ll hear about this supper, which won’t improve conditions at home. Now, we both had to come to this Oriental orgy, and, since neither of us enjoys it, let’s be natural, at least. I haven’t slept lately, and I’m not patient enough to be polite.”

“It’s a bargain. I’ll try to be as disagreeable as you are,” said Lorelei; and Mr. Merkle signified his prompt acquiescence. He lit a huge monogrammed cigarette, pushed aside his hors d’oeuvres, and reluctantly turned down his array of wine-glasses one by one.

“Can’t eat, can’t drink, can’t sleep,” he grumbled. “Stewed prunes and rice for my portion. Waiter, bring me a bottle of vichy, and when it’s gone bring me another.”

The diners had arranged themselves by now; the supper had begun. Owing to the nature of the affair, there was a complete absence of the stiffness usual at formal banquets, and, since the women were present in quite the same capacity as the performers who were hired to appear later on the stage, they did not allow the moments to drag. A bohemian spirit prevailed; the ardor of the men, lashed on by laughter, coquetry, and smiles, rose quickly; wine flowed, and a general intimacy began. Introductions were no longer necessary, the talk flew back and forth along the rim of the rose-strewn semicircle.

Lorelei turned from—the man on her left, who had regaled her with an endless story, the point of which had sent the teller into hiccoughs of laughter, and said to John Merkle:

“I’m glad I’m with you to-night. I don’t like drinking men.”

“Can a girl in your position afford preferences?” he inquired, tartly. Thus far the banker had fully lived up to his sour reputation.

“All women are extravagant. I have preferences, even if I can’t afford them. If you were a tippler instead of a plain grouch I could tell you precisely how you’d act and what you’d talk about as the evening goes on. First you’d be gallant and attentive; then you’d forget me and talk business with Mr. Wharton—he’s nearest you. About that time I’d begin to learn the real names of these lords of finance. After that you’d become interested in my future. That’s always the worst period. Once I’d made you realize that you meant nothing in my life and that my future was provided for, you’d tell me stories about your family—how your wife is an invalid, how Tom is at Yale, how Susie is coming out in the autumn, and how you really had no idea ladies were to be present tonight or you’d never have risked coming. Finally you’d confess that you were naturally impulsive, generous, and affectionate, and merely lacked the encouragement of a kindred spirit like me to become a terrible cut-up. Then you’d insist upon dancing. I’d die if I had to teach you the tango.”

Mr. Merkle grunted, “So would I.”

She smiled sweetly. “You see, we’re both unpleasant people.”

Merkle meditated in silence while she attacked her food with a healthy, youthful appetite that awoke his envy.

“I suppose you see a lot of this sort of thing?” he at length suggested.

“There’s something of the kind nearly every night. Is this your first experience?”

“Um-m—no. Steel men are notoriously sporty when they get away from home. But I don’t go out often.”

“This party isn’t as bad as some, for the very reason that most of the men are from out of town and it’s a bit of a novelty to them. But there’s a crowd of regular New-Yorkers—the younger men-about-town—” She paused significantly. “I accepted one invitation from them.”

“Only one?”

“It was quite enough.”

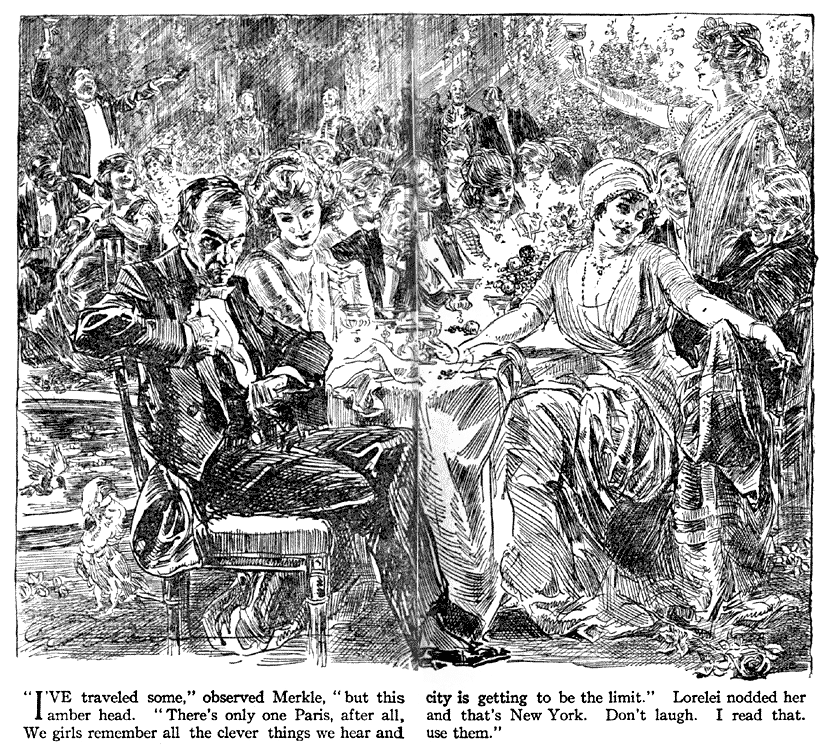

“I’ve traveled some,” observed Merkle, “but this city is getting to be the limit.”

She nodded her amber head. “There’s only one Paris, after all, and that’s New York. Don’t laugh; I read that. We girls remember all the clever things we hear, and use them. Do you see the young person in black and white with the red-nosed man—the one who looks as if he were smelling a rose? Well, she’s in our company, and she’s very popular at these parties because she’s so witty. As a matter of fact, she memorizes the jokes in all the funny papers and springs them as her own. Her men friends say she’s too original to be in the show business.”

For a moment the girl at Merkle’s right engaged his attention, and Lorelei turned again to the incoherent story-teller beside her, who had made it plain by pawing at her that he was bursting once more with tidings of great merriment.

The meal grew noisier; the orchestra interspersed sensuous melodies from the popular successes with the tantalizing rag-time airs that had set the city to singing. Silent-footed attendants deposited tissue-covered packages before the guests. There was a flutter of excitement as the women began to examine their favors.

“What is it?” Merkle inquired, leaning toward Lorelei.

“The new saddle-bag purse. See? It’s very Frenchy. Gold fittings—and a coin-purse and card-case inside. See the monogram? I’m going to keep this.”

“Don’t you keep all your gifts?”

“Not the expensive ones. Lilas picked these out for Mr. Hammon, and they’re exquisite. We share the same dressing-room, you know.”

Merkle regarded her with a sudden new interest.

“You and she dress together?”

“Yes.”

“Then—I dare say you’re close friends?”

“We’re close enough—in that room; but scarcely friends. What did you get?”

He unrolled the package at his plate.

“A gold safety razor—evidently a warning not to play with edged tools. I wonder if Miss Lynn bought one for Jarvis?”

“Now, why did you say that,” Lorelei asked, quickly, “and why did you ask in that peculiar tone if she and I were friends?”

The man leaned closer, saying in a voice that did not carry above the clamor:

“I suppose you know she’s making a fool of him? I suppose you realize what it means when a woman of her stamp gets a man with money in her power? You must know all there is to know from the outside; it occurred to me that you might also know something about the inside of the affair. Do you?”

“I’m afraid not. All I’ve heard is the common gossip.”

“There’s a good deal here that doesn’t show on the surface. That woman is a menace to a great many people, of whom I happen to be one.”

“You speak as if she were a dangerous character, and as if she had deliberately entangled him,” Lorelei said, defendingly. “As a matter of fact, she did nothing of the sort; she avoided him as long as she could, but he forced his attentions upon her. He’s a man who refuses defeat. He persisted, he persecuted her until she was forced to—accept him. Men of his wealth can do anything, you know. Sometimes I think—but it’s none of my business.”

“What do you sometimes think?”

“That she hates him.”

“Nonsense.”

“I know she did at first; I don’t wonder that she makes him pay now. It’s according to her code and the code of this business.”

“I can’t believe she—dislikes him.”

“He may have won her finally, but at first she refused his gifts, refused even to meet him.”

“She had scruples?”

“No more than the rest of us, I presume. She gave her two weeks’ notice because he annoyed her; but before the time was up Bergman took a hand. He sent for her one evening, and when she went down there was Mr. Hammon, too. When she came up-stairs she was hysterical. She cried and laughed and cursed—it was terrible.”

“Curious,” murmured the man, staring at the object of their controversy. “What did she say?”

“Oh, nothing connected. She called him every kind of a monster, accused him of every crime from murder to—”

“Murder!” The banker started.

“He had made a long fight to beat her down, and she was unstrung. She seemed to have a queer physical aversion to him.”

“Humph! She’s got nobly over that.”

“I’ve told you this because you seemed to think she’s to blame, when it is all Mr. Hammon’s doing.”

“It’s a peculiar situation—very. You’ve interested me. But the man himself is peculiar, extraordinary. You can’t draw a proper line on his conduct without knowing the circumstances of his home life, and, in fact, his whole mental make-up. Sometime I’ll tell you his story; I think it would interest you. In a way I don’t blame him for seeking amusement and happiness where he can find it, and yet—I’m afraid of the result. This supper means more than you can understand or than I can explain.”

“The city is full of Samsons, and most of them have their Delilahs.”

Merkle agreed. “These men put Hammon where he is. I wonder if they will let him stay there. It depends upon that girl yonder.” He turned to answer a question from Hannibal Wharton, and Lorelei gave her attention to the part of the entertainment which was beginning on the stage. Turn after turn appeared; black-faced comedians, feature acts from vaudeville and from the reigning successes, high-priced singers, dancers, monologists followed each other. Occasionally they were applauded, but more frequently their efforts to amuse were lost in the self-made merriment of the diners. Now and then an actor was bombarded with jests or openly guyed. Music and wine flowed as steadily as the crystal stream of the fountain; faces became flushed; glasses rang. The women chattered; the men raised loud voices; the birds fluttered and the peacocks shrieked. It all blended in a blood-stirring, Bacchanalian joviality. Only now and then the frolic threatened to become a carouse, and the revel bordered upon a debauch.

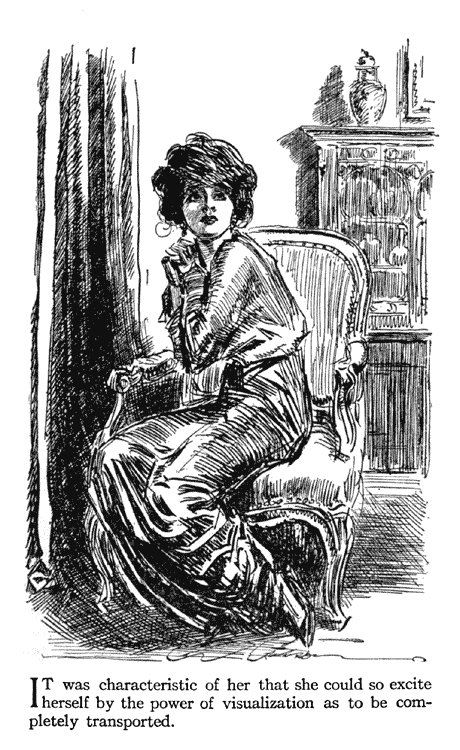

Of a sudden the clamor was silenced, and indifference gave place to curiosity, for the music had begun the introduction to one of Adoree Demorest’s songs.

“Her rubies are the finest in the world.” “Too strong for Paris, so she came to New York.” “Anything goes here if it’s bad enough,” came from various quarters.

Lorelei had never seen this much-discussed actress, whose wickedness had set the town agog, and her first impression was vaguely disappointing. Miss Demorest’s beauty was by no means remarkable, although it was accentuated by the most bizarre creation of the French shops. She was animated, audacious, Gallic in accent and postures—she was vividly alive with a magnetism that meant much more than beauty; but she over-exerted her voice, and her song was nothing to excite applause. At last she was off, in a whirl of skirts, a generous display of hosiery, and a great bobbing of the aigrette pompon that towered above her like an Indian head-dress. Only a moment later she was on again, this time in a daring costume of solid black, against and through which her limbs flashed with startling effect as she performed her famous Danse de Nuit.

“Hm-m! Nothing very extreme about that,” remarked Merkle, at length. “It would be beautiful if it were better done.”

Lorelei agreed. She had been staring with all a woman’s intentness at this sister whose strength consisted of her frailty, and now inquired:

“How does she get away with it?”

“By the power of suggestion, I dare say. Her public is looking for something devilish, and discovers whatever it chooses to imagine in what she says and does.”

Hannibal Wharton had changed his seat, and, regardless of the dancer, began a conversation with Merkle. After a time Lorelei heard him say:

“It cost me five thousand dollars to pay for the damage those boys did. They threatened to jail Bob, but of course I couldn’t allow that.”

“I remember. That was five years ago, and Bob hasn’t changed a whit. I think he’s a menace to society.”

Wharton laughed, but his reply was lost in the clamorous demand for an encore by Mlle. Demorest.

“So he gets his devilment from you, eh?” Merkle inquired.

“It isn’t devilment. Bob’s all right. He’s running with a fast crowd, and he has to keep up his end.”

“Bah! He hasn’t been sober in a year.”

“You’re a dyspeptic, John. You were born with a gray beard, and you’re not growing younger. He wanted to come to this party, but—I didn’t care to have him for obvious reasons, so I told Hammon to refuse him even if he asked. He bet me a thousand dollars that he’d come anyhow, and I’ve been expecting him to overpower those doormen or creep up the fire-escape.”

The hand-clapping ceased as the dancer reappeared, smiling and bowing.

“I will dance again if you wish,” she announced, in perfect English, “introducing my new partner, Mr.—” she glanced into the wings inquiringly—“Senor Roberto. It is his first public appearance in this country, and we will endeavor to execute a variation of the Argentine tango. Senor Roberto is a poor boy; he begs you to applaud him in order that he may secure an engagement and support his old father.” She stooped laughingly to confer with the orchestra leader, who had broken cover at her announcement.

Mr. Wharton was still talking. “That’s my way of raising a son. I taught Bob to drink when I drank, to smoke when I smoked, and all that. My father raised me that way.”

The opening strain of a Spanish dance floated out from the hidden musicians, Mlle. Demorest whirled into view in the arms of a young man in evening dress. She was still laughing, but her partner wore a grave face, and his eyes were lowered; he followed the intricate movements of the dance with some difficulty. To Lorelei he appeared disappointingly amateurish. Then a ripple of merriment, growing into a guffaw, advised her that something out of the ordinary was occurring.

“The—scoundrel!” Hannibal Wharton cried.

Merkle observed dryly: “He’s won your thousand. I withdraw what I said about him; it requires a gigantic intelligence to outwit you.” To Lorelei he added: “This will be considered a great joke on Broadway.”

“That is Mr. Wharton’s son?”

“It is—and the most dissipated lump of arrogance in New York.”

“Bob,” the father shouted, “quit that foolishness and come down here!” But the junior Wharton, his eyes fixed upon the stage, merely danced the harder. When the exhibition ended he bowed, hand in hand with Miss Demorest, then leaped nimbly over the footlights and made his way toward Jarvis Hammon, nodding to the men as he passed.

A moment later he sank into a chair near his father, saying: “Well, dad, what d’you think of my educated legs? I learned that at night school.”

Wharton grumbled unintelligibly, but it was plain that he was not entirely displeased at his son’s prank.

“You were superb,” said Merkle, warmly. “It’s the best thing I ever saw you do, Bob. You could almost make a living for yourself at it.”

The young man grinned, showing rows of firm, strong teeth. Lorelei, who was watching him, decided that he must have at least twice the usual number; yet it was a good mouth—a good, big, generous mouth.

“Thanks for those glorious words of praise; that’s more than we’re doing on the Street nowadays. Miss Demorest said we’d ‘execute’ the dance, and we did. We certainly killed Senor Thomas W. Tango, and I’ll be shot at sunrise for stamping on Adoree’s insteps. I looked before I leaped, but I couldn’t decide where to put my feet. Whew! Got any grape-juice for a growing boy?” He helped himself to his father’s wine-glass and drained it. “You can settle now, dad—one thousand iron men. I owe it to Demorest.”

“What do you mean?”

“Debt of honor. I heard she was due here with some kind of an electric thrill, so I offered her my share of the sweepstakes to further disgrace herself by dancing with me. She’s an expensive doll; she needs that thousand—mortgage on the old family opera-house, no shoes for little sister, and mother selling papers to square the landlord.” He caught Lorelei’s eye and stared boldly. “Hello! I believe in fairies, too, dad. Introduce me to the Princess.”

Merkle volunteered this service, and Bob promptly hitched his chair closer. Lorelei saw that he was very drunk, and marveled at his control during the recent exhibition.

“Tell me more about the ‘Parti-color Petticoat’ and ‘Dentol Chewing-Gum,’ Miss Knight. Your face is a household word in every street-car,” he began.

She replied promptly, quoting haphazard from the various advertisements in which she figured. “It never shrinks; it holds its shape; it must be seen to be appreciated; is cool, refreshing, and prevents decay.”

“How did you meet that French dancer?” Hannibal Wharton queried, sourly, of his son.

“I stormed the stage door, bullied the door-man, and waylaid her in the wings. She thought I was you, dad. Wharton is a grand old name.” He chuckled at his father’s exclamation. “She’s a good fellow, though, and I don’t blame the King of What’s-its-name. Kings have to spend their money somewhere. Maybe I can induce her to invest some of the royal dough in stocks and bonds. The prospect dizzies me.”

“The crowd in your office would give you a banquet if you sold something,” Merkle told him.

Wharton, Senior, pressed for further information. “Where did you learn those Argentine wiggles?”

“Hard times are to blame, dad. The old men on the Exchange play golf all day, and the young ones turkey-trot all night. I stay up late in the hope that I may find a quarter that some suburbanite has dropped. It’s dangerous to drive an automobile through a dark street these days; one’s liable to run down a starving banker or an indigent broker with a piece of lead pipe and a mask. You find it so, don’t you, Miss Knight?”

“I have no automobile,” said the girl.

“Strange. Show business on the blink, too, eh?” The elder men rose and sauntered away in the direction of their host, whereupon Bob winked.

“They’ve left us flat. Why? Because the wicked Mlle. Demorest has finally made her appearance as a guest. My dad is a splendid shock-absorber. Naughty, naughty papa!”

“It’s probably well that you came with her; fathers are so indiscreet.”

Young Wharton signaled to a waiter who was passing with a wine-bottle in a napkin.

“Tarry!” he cried. “Remove the shroud, please, and let me look at poor old Roderer. Thanks. How natural he tastes.” Then to Lorelei: “The governor is a woman-hater; but, just the same, I’m glad you drew Merkle instead of him to-night, or there’d surely be a scandal in the Wharton family. No man is safe in range of your liquid orbs, Miss Knight, unless he has his marriage license sewed into his clothes. Mother keeps hers framed. Wouldn’t she enjoy reading the list of Hammon’s guests at this party? ‘Among those present were Mr. Hannibal C. Wharton, the well-known rolling-mill man; Miss Lorelei Knight, Principal First-Act Fairy of the Bergman Revue; and Mlle. Adoree Demorest, the friend of a king. A good time was had by all, and the diners enjoyed themselves very nice.’ ” He laughed loudly, and the girl stirred.

“She’d be pleased to read also that you came late, but highly intoxicated.”

“Ah! Salvation Nell.” Bob took no offense. “If the hour was late she’d know that my intoxication followed as a matter of course. It always does, just as the dew succeeds the sunset, as the track follows the wheelbarrow, as the cracker pursues the cheese. I am a derivative of alcohol, the one and infallible argument against temperance, Miss Knight. In me you behold the shining example of all that puts the reformer to rout and gladdens the heart of the cafe-keeper.”

“You talk as if you were always drunk.”

“Oh—not always. By day I am frequently sober, but at such times I am fit company for neither man nor beast; I am harsh and unsympathetic; I scheme and I connive. With nightfall, however, there comes a metamorphosis. Ah! Believe me! When the Clover Club is strained and descends like the gentle dew of heaven, when the Bronx is mixed and the Martini shimmers in the first rays of the electric light, then I humanize and harmonize, For me gin is a tonic, rum a restorative, vermuth a balm. Once I am stocked up with ales, wines, liquors, and cigars, I become attuned to the nobler sentiments of life. I aspire. I make friends with lonely derelicts whose digestions have foundered on seas of vichy and buttermilk, and I show them the joys of alcoholism—without cost. We share each other’s pleasures and perplexities, at my expense. They are my brothers. I am optimistic; I laugh; I play cards for money; I turkey-trot. I become a living, palpitating influence for good, spreading happiness and prosperity in my wake.”

“Do you consider yourself in such a condition now?” queried Lorelei, who had been vaguely amused at this Rubaiyat.

“I am, and, since it is long past the closing hour of one and the tango parlors are dark, suppose we blow this ‘Who’s Who in Pittsburg’ and taxi-cab it out to a roadhouse where the bass fiddle is still inhabited and the second generation is trotting to the ‘Robert E. Lee’?”

Lorelei shook her head with a smile.

“Don’t you dance?”

“Doesn’t everybody dance?”

“Then how did you break your leg?”

“I don’t care to go.”

“Strange!” Mr. Wharton helped himself to a goblet of wine, appearing to heap the liquor above the edge of the glass. “Now, if I were sober I could understand how you might prefer these ‘pappy guys’ to me, for nobody likes me then, but I’m agreeably pickled. I’m just like everybody you’ll be likely to meet at this time of night. Merkle won’t take you anywhere, for he’s full of distilled water and has a directors’ meeting at ten. I overflow with spirits and have a noontide engagement with an Ostermoor.”

“Why don’t you ask Miss Demorest? She came with you?”

Wharton sighed hopelessly. “Something queer about that Jane. D’you know what made us so late? She went to mass on the way down.”

“Mass? At that hour?”

“It was a special midnight service conducted for actors. I sat in the taxi and waited. It did me a lot of good.”

Some time later Merkle returned to find Bob still animatedly talking; catching Lorelei’s eye, he signified a desire to speak with her, but she found it difficult to escape from the intoxicated young man at her side. At last, however, she succeeded, and joined her supper companion at the farther edge of the fountain, where the tireless cupids still poured water from the cornucopias.

Merkle was watching his friend’s son with a frown.

“You have just left the personification of everything I detest,” he volunteered. “You heard what his father said about raising him—how he taught Bob to drink when he drank and follow in his footsteps? Well, sometimes the theory works and a boy grows up with open eyes, but more often it turns out as it has in this case. Bob’s an alcoholic, a common drunkard, and he’ll end in an institution, sure. He’d be there now if it wasn’t for Hannibal’s money. He’s run the gamut of extravagance; he’s done everything freakish that there is to do. But that isn’t what I want to say to you. Help me feed these foolish goldfish while I talk.”

“Do you think anybody would understand if they overheard you? I fancied you and I were the only sober ones left.”

“Some of the girls are all right.” Merkle eyed his companion closely. “Don’t you drink?”

“I daren’t, even if I cared to.”

“Daren’t?”

“You’ll notice that most of the pretty girls are sober.”

“Right.”

“I have nothing but my looks. Wouldn’t I be a fool to sacrifice them?”

“You seem to be sensible, Miss Knight. Something tells me you’re very much the right sort. I know you’re trying to get ahead, and—I can help you if you’ll help me.”

“Help you ‘get ahead’?”

He smiled. “Hardly. I need an agent, and I’ll pay a good price to the right person.”

“How mysterious!”

“I’ll be plain. That affair yonder”—he nodded toward Jarvis Hammon and Lilas Lynn—“strikes you as a—well, as a flirtation of the ordinary sort. In one way it is; in another way it is something very different, for he’s in earnest. He thinks he is injuring no one but himself with this business, and he is willing to pay the price; but the fact is he is putting other people in peril—me among the rest. I’m not arguing for his wife nor the two Misses Hammon. I don’t go much on the ordinary kinds of morality, and nobody outside of a man’s family has the right to question his private life so long as it is private in its consequences. But when his secret conduct affects his business affairs, when it endangers vast interests in which others are concerned, then his associates are entitled to take a hand. Do I make myself clear?”

“Perfectly. But you don’t want me; you want a detective.”

“My dear child, we have them by the score. We hire them by the year, and they have told us all they can. We need inside information.”

The girl’s answer was made with her habitual self-possession.

“I’ve heard about such things. I’ve heard about men prying into each other’s private affairs, pretending to be friends when they were enemies, and using scandal for business ends. Lilas Lynn is my friend—at least in a way—and Mr. Hammon is my host, just as he is yours. Oh, I know; this isn’t a conventional party, and I’m not here as a conventional guest—inside the little coin-purse he gave me is a hundred-dollar bill—but, just the same, I don’t care to act as your spy.”

Merkle’s grave attention arrested Lorelei’s burst of indignation.

“Will you believe me,” he asked, “when I tell you that Jarvis Hammon and Hannibal Wharton are the two best friends I have in the world? There is such a thing as loyalty and friendship even in big business; in fact, high finance is founded on confidence and personal honor. This is more than a business matter, Miss Knight.”

“I can hardly believe that.”

“It’s true, however; I mean to serve Hammon. At the same time I must serve myself and those who trust me. My honor is concerned in this as well as his, and there is a rigid code in money matters. If what I suspect is true, Hammon’s infatuation promises to do harm to innocent people. I fear—in fact, I’m sure—that he is being used. I’ve learned things about Miss Lynn that you may not know. What you have told me to-night adds to my anxiety, and I must know more.”

“What, for instance?”

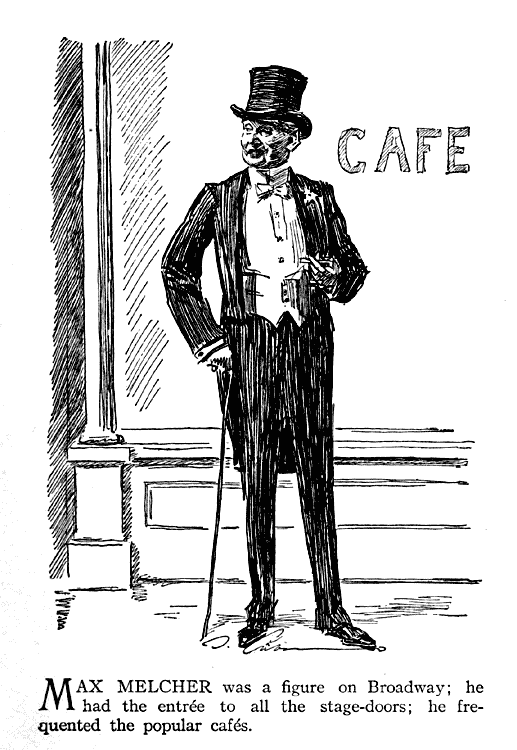

“Her real feeling for him—her intentions—her relations with a man named Melcher—”

“Maxey Melcher?”

“The same. You know his business?”

“No.”

“He is a gambler, a political power; a crafty, unscrupulous fellow who represents—big people. By helping me you can serve many innocent persons and, most of all, perhaps, Hammon himself.”

Lorelei was silent for a moment. “This is very unusual,” she said, at length. “I don’t know whether to believe you or not.”

“Suppose, then, you let the matter rest and keep your eyes open. When you convince yourself who means best to Jarvis—Miss Lynn and Melcher and their crowd, or I and mine—make your decision. You may name your own price.”

“There wouldn’t be any price,” she told him, impatiently. “I’ll wait.”