a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The King Of No-Land Author: B. L. (Benjamin Leopold) Farjeon * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1900231h.html Language: English Date first posted: February 2019 Most recent update: February 2019 This eBook was produced by: Colin Choat Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

I. A WHITE-ROBED

WOOD, BATHED IN SWEET AIR

II. MANY MEN GROW BLIND BY LOOKING AT THE SUN,

AND NEVER SEE THE BEAUTY OF THE STARS

III. DEEP IN THE EARTH LIES THE GOLD, HIDDEN IN

DARKNESS; AND PRECIOUS STONES ARE FOUND IN ROUGHEST PLACES

IV. CHRISTMAS NIGHT AT THE COTTAGE

V. LIKE WHITE FINGERS BECKONING THE DEAD

VI. TO GRASP THE JEWELLED HAND OF POVERTY

VII. THE THREE SMALL FIDDLERS, IRIS, LUCERNE,

AND DAISY

VIII. NO EXAMPLE OF MINE SHALL EVER WEAKEN OR

DEGRADE IN MY PEOPLE'S EYES THE SANCTITY OF THE MARRIAGE BOND

IX. THE QUAMOCLITS AND THE WHORTLEBERRIES

X. SWEET IS THE AIR NOW AND FOR EVER; HEART

WHISPERS LOW, CHANGE WILL COME NEVER

XI. "NOW," SAID THE KING, STEPPING CLOSE TO THE

PRISONER; "AS MAN TO MAN!"

XII. THE KING NARRATES TO THE COURT PARASITES

THE PARABLE OF THE TREES

XIII. OLD HUMANITY

XIV. THE FLIGHT FROM THE PALACE

XV. THROUGHOUT THREE CHANGES OF THE SEASONS

XVI. CUNNING LITTLE DICK

XVII. IT WAS CHRISTMAS THROUGHOUT ALL THE

LAND

KING SASSAFRAS reigned over the kingdom of No-land. He was crowned in the snow season; and one of the leading papers of the capital, in its enthusiastic comments upon the imposing ceremony, poetically remarked that the soft flakes of snow which floated dreamily in the air and kissed the earth during the day, were white-winged heralds of welcome sent expressly from heaven to greet the Lord's elect. They were sure indications also, it was said, that the reign of the new King would be a reign of purity and love. A copy of these sentiments, printed upon white satin in letters of gold, was presented to the King, and he read them with a certain kind of pleasure, although he seemed at the same time to be inwardly disturbed by the extravagant praise which was lavished upon his personal virtues and qualifications—being doubtful, perhaps, whether it was deserved. But the sentiments expressed and the similes drawn were decidedly pretty and graceful, and as the writer was satisfied with his work, it is to be hoped his readers also were.

As no further reference will be made to the ceremony of the coronation, let it be here briefly stated that, gorgeous and solemn as it was, the King's thoughts frequently wandered from the brilliant scene of which he was the principal figure. The myriad facets of light, the silks, the laces, the thousands of eyes that gazed worshipfully upon his person, faded from his sight as utterly as if they had no existence, and in their place there came:

A white-robed wood, bathed in sweet air. A cottage in the distance, covered with ivy, whose every snow-rimmed leaf, with its feathery tip, was a marvel of beauty. Nests in the chimneys, with birds peeping out—gratefully, for good store of food was theirs. A modest and beautiful young maid; a grave-visaged man; an old woman with white hair; and, strangest of all, three little girls, armed with violins and bows, playing quaint old tunes with wonderful grace.

Clang! The trumpet's blast blew these fancies into nothingness, and precious stones and silks and laces reigned again.

No-land was a vast territory, and its inhabitants numbered maul millions. Sassafras was the first! king of that name, and he came to the throne when he was twenty years of age. There were substantial rejoicings, of course, upon the occasion, and in all the towns and cities and even villages of No-land the new King's subjects made merry and feasted for a week. All the subjects, that is, except those who did not believe in kings and queens; but even they assembled in their way and in their places, and extracted grim satisfaction from the feast of the future, which they painted in colours hard and fast and warranted to wash. Generally, however, the people, being worked into a state of enthusiasm, were red-hot with excitement; guns and cannon were in the same condition; triumphal arches were erected; loyal dinners were loyally eaten; loyal speeches were loyally spoken; mayors, lord mayors, and councillors were in their glory, and each frog thought himself an ox; children were dressed in their Sunday clothes and taken out to sec the sights; the theatres were thrown open free to the people, who behaved as the people generally do on such occasions, with much gentleness; and at night the streets were flooded with light. Just before that time the doctors of No-land had been complaining that things were very bad, and were shaking their heads at each other with ominous looks, being depressed by the healthfulness of the people. But the feasting indulged in by the new King's subjects on his accession to the throne brought on dyspepsia and other ailments, and for many weeks after that event the doctors' pockets were filled with guineas. Then they had hopes of their country, and with cheerful looks declared that the reign of the first Sassafras had commenced most auspiciously.

The father of Sassafras had been a hypochondriacal valetudinarian, and being entirely wrapped up in himself (as most such characters are, whether high or low in station), bestowed no care and but little thought upon his son. Losing his health in the pursuit of pleasure, in which all his intellect was engaged and all his moral and religious affections were buried, he hobbled for years after his lost treasure in precisely the very places where it was not to be found, and growing year after year more querulous and infirm and selfish, he often for months together forgot that he had a child. His forgetfulness was a gain to Sassafras who, being given into the charge of a number of tutors and time-servers, found life more pleasant than it would have been to him had he been doomed to endure the caprices of his royal father. With this retinue he passed his time until the arrival of the day when the people went into mourning for the death of the King, and wept, and wore crape, and gazed dolefully at each other, because a ruler who had many vices and no virtues had passed away from among them. At the time of the King's death—the immediate symptoms preceding which were so sudden that he was maddened and confounded when he was told he had but a few hours to live—the heir-apparent was abroad, travelling by command of the King; but the news came to him by wire and courier, and he hastened home, shortly after reaching which he was crowned and made king, to every one's satisfaction apparently but his own. Those who were about him at that period were glad to be relieved of an awkward responsibility, for they found him difficult to manage. This is not surprising, for even during his calm-hood his tutors and time-servers had had no easy time of it. Young as he was, he had a mind of his own, in which, by some means, notions and ideas not exactly in accordance with his royal station found place. Gentle he was by nature, but he was also rebellious of restraint. Being a very exalted baby, the greatest possible fuss had been made with him from his birth; but even as a baby he seemed to wonder at the oppressive attention which was bestowed upon him. As he grew, this wonder changed into inward rebellion; and from the time that he began to think of things, he chafed and fretted at not being let alone. On one memorable occasion during his boyhood he entered a vigorous protest against this.

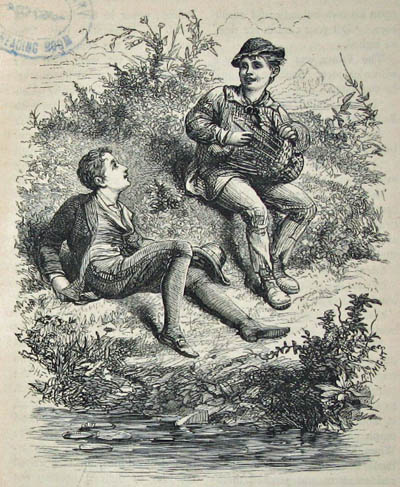

He had planned a truant run into the woods, being animated by an eager desire to climb one particular old elm-tree, through the branches of which, in the summer, the clouds could be seen sailing like fairy ships on a white and blue sea, and among which the birds built their nests and flitted merrily in the sunlight. In the winter the fairy ships sped swiftly onwards before the driving wind, and the birds made themselves warm and snug in their nests. The Prince longed to sit among the higher branches of this tree, with his back against the trunk, and watch the clouds and the birds, and idly muse upon goodness knows what. On a fine summer morning he escaped from the palace as he had designed, and he ran into the forest; but just as he was about to climb the old elm, having selected the particular branches in which he would sit and be enthroned, his tutors and time-servers came running after him, and he had not time to get out of their reach. He was desperately angry.

"Hands off!" he cried, shaking himself free from them.

They stood about him, almost breathless with the run they had had.

"Why," exclaimed the Prince, "should I be surrounded in this manner, and be dogged and watched as if I were a slave? Am I a slave?"

They raised their hands in astonishment, and their voices also.

"A slave, your Royal Highness!" they cried. "You! It is we who are slaves—your slaves, ready to lay down our lives for you."

"Then," demanded the Prince, "why don't you go away and let me climb this tree? See there! Those two branches with their arms folded, looking down upon us. If you look attentively at them, you will see two queer brown faces bending towards us. They are like twin brothers embracing. You don't see anything of the sort? No, that is because you don't care to. But you can't help seeing in what fantastic fashion their twisted limbs are made into the shape of an S, the initial of my name. Nature might have made the symbol for me—nay, nature has! See those peeps of the sun, and that bright cloud which dyes with heaven's light the feathers of the birds flying beneath it. See how the sunbeams are laughing. I want to climb into those branches and make my throne there. Why don't you go away and let me, if you are my slaves?"

"Your Royal Highness," they answered, in piteous tones, "you must not—you must not! You might break one of your royal limbs—"

"No, I won't; you watch now!" And Prince Sassafras darted from among them. But before his lithe body could embrace the trunk, his tutors and time-servers threw their arms about him, and besought him to be reasonable. As they formed a circle around him, his breast heaved with passion, and his eyes were filled with indignant tears.

"You mock me!" he cried. "Who is the slave—you or I? I can't move; I am tied down! Other boys climb trees, and don't break their limbs!"

Forward came the Court Statistician, all the wrinkles in whose face formed figures of =, and produced a book from which he read how many boys in the kingdom of No-land climbed trees annually, how many met with accidents, and what the percentage of the one to the other was.

"Bother!" exclaimed the Prince, putting his fingers in his ears. "I don't want to hear it—I won't hear it! I want to climb this tree."

"The hopes of the nation are centred in you—" they pleaded.

"I don't believe it," he exclaimed, interrupting them.

"The eyes of the world are upon you—"

"Why don't they turn their eyes away, then? What is it to them? I don't want them to stare at me so; I want to be let alone. The eyes of the world won't see me climb the tree, if you will let me."

"We dare not allow your Royal Highness to run the risk."

"O," he said, with sarcastic emphasis; "you dare not allow me And I am not a slave!"

"You are our most gracious prince and master." And they bowed and fussed about him most obsequiously.

"O, I am, am I? Well, one day you shall see"—they inclined their heads eagerly; he gave them a queer look—"Well, you shall see what you shall see!"

And the Prince laughed at their eager air, and then grew thoughtful, and returned with them to the palace.

Being endowed with the delicate cunning which is often a special attribute of sensitive young natures, and of quiet shy women as well, he was not to be so easily thwarted as they imagined; and, pitting his wit against theirs, he proved himself more than a match for the wily old courtiers, deeply steeped as they were in world wisdom. They kept a strict watch upon him, and he knew it; and they did not know that he knew it. He bided his time patiently; and one day he was missing. They hunted for him here and there, but although they thought they were acquainted with every nook and corner in the woods and palace, they could not find him. They searched for him under the beds and in the cupboards, and up the trees and in the summerhouses, and in every place where it was possible for him to hide himself; they turned the palace inside out, to speak figuratively, and the grounds about the palace outside in; they questioned the sentries and the cooks and the gardeners; they locked up one old woman and three small boys for not giving satisfactory replies to unintelligible questions; and all to no avail. In a certain corner in a certain closet they might have found the suit of clothes the Prince had worn the day before—for he had taken the precaution to array himself in the plainest garments he could get together—but they certainly would not have found him. Where was he?

He had made his way, by devious paths, so that he might not be tracked, to a quiet hollow near the base of a flower-clad hill, in the crown of which a pretty stream had birth, the silver water-threads of which danced down the sides most unmathematically and erratically. Once or twice he had lingered on the road, to listen to the whisper of the corn which was ripening in the fields, and to watch the bees as, with their dusky belts of burnished gold, they flew, honey-laden, to their hives, humming hymns of gladness in praise of bounteous nature. Summer's sweetest breath was here, and the wondrous colours of a myriad delicate flowers were made more beautiful by contrast with the tufts of bright green moss which dotted the course of the silver stream, and drew life from its laughing spray. Here the water-beads ran swiftly; here they stole slyly; here they flashed merrily: as if they were being pursued, and were fearful lest they should be caught; or as if they were stealing to where their lovers were sleeping; or as if, with their glistening eyes, they were speeding to the embrace of beloved companions; or as if, with their fresh lips bubbling with joyous delight, they were running to kiss the wild flowers that grew at the foot of the hill, and to breathe new life and beauty into them. In this retired spot there were no trees; but there were masses of wild forget-me-nots and other flowers as beautiful, to charm the senses of the truant Prince. Roaming about this lovely retreat—now stooping to kiss his own lips in the sparkling stream, and to taste its sweet waters; now pausing to listen to the melody of the birds; now gazing with heart-worship at the light and colour which surrounded him, and with full soul drinking in the beauty of nature's most wondrous works—the Prince came suddenly upon a lad of about the same age as himself, Robin was this lad's name; poorly-clad was he; with a sunburnt face, and with eyes afire with light caught from nature's smiles.

"Hallo!" cried Robin.

"Hallo!" responded the Prince; and sat him down, and looked at the exquisite tints of the leaves and petals, and then looked up at the skies, and wondered whether the flowers drew their colour from the clouds. The lads fell into conversation, and the Prince, who was a cunning questioner, learned in a very short time a great deal concerning Robin.

"So your father is a woodman?" said the Prince, stretching himself lazily on the ground, and peering into a tangle of wild forget-me-nots, whose thousand blue eyes peered up into his own.

"Yes," answered Robin; "he cuts wood for the King."

"Has he got a large house?"

"It ain't a house; it's a cottage. But it's large enough, and better than some. There's a garden, and plenty of beans and taters; and mother's a good tin t And there's a litter of pigs."

"Ah," said the Prince, with a sudden and unaccountable interest in the litter of pigs, "and what do they do?"

"They squeak, they do—except the big uns."

"And they?"

"They grunt, they do!" And Robin laughed at his own wit.

The Prince reflected upon this information, and not finding the subject profitable, dismissed the pigs from the conversation.

"Have you got woods and grounds?"

"Yes, surely; all, these." And Robin made a comprehensive sweep with his arm, as though all the hills and woods were as good as his.

"Is your father happy?"

"There's something 'd make him happier."

"What's that?"

"Two shillin' a week more."

"If he had that, he'd be quite happy?"

"Ay, as happy as the day is long."

"And you—you are not watched and surrounded and dogged by spies, are you?"

"No, indeed!" said Robin, with a stare. I should like to catch "em at it!"

"And if you want to climb a tree, you can, eh?"

"I should think so! I say, did you ever go birds'-nesting?"

"No," replied the Prince; "is it nice?"

Robin's blithe laughter ran along the hill, and met the dancing water-beads, which rippled into the stream with it.

"Nice There ain't nothing in the world like it. But you've got to be careful, you know, sometimes. Some places you mustn't go into; and they're the best! Some trees you mustn't climb; and they're the best! Then you've got to look about you. Such fun!"

"And go elsewhere, eh?"

"Not a bit of it," chuckled Robin. "Can't get such fun out of elsewhere. No; go into them places that you mustn't go into—when nobody's looking! Climb them trees that you mustn't climb—when nobody's looking. Get them birds'-nests—when nobody's looking! And run home with them—when nobody's looking!"

And Robin rubbed his hands, and looked about him blithely, as though he were doing all these delightful things.

"And to whom do those trees belong, Robin?"

"They're in the King's ground, but the King he don't mind a bit. He ain't mean enough!"

Prince Sassafras laughed at the idea of this common boy outwitting the attendants, who were always on the watch with dogs and guns; but his laughter changed to sighs as he thought, "O, if I might do this! If I might go birds'-nesting in one of my own trees!"

Said Robin, "Never went birds'-nesting! Ho, ho! Did you ever hear the larks sing when they get up of a morning?"

"No," sighed the Prince, "I am not out of bed early enough.. It must be beautiful!"

"It's just jolly, that's what it is. Did you ever go nutting?"

"No," sighed the Prince.

"Nor blackberrying?"

"No," sighed the Prince.

Robin stared at the Prince with a mixed feeling of pity and contempt; and the Prince, keenly alive to his own shame, hung his head. Robin gave him one more chance.

"Did you ever get up in the night and steal the pickles and the jam?"

"No," murmured the Prince, tears of humiliation coming into his eyes.

Robin, with a disdainful shrug of his shoulders, fell-to upon his work, with the evident conviction that further conversation would be wasted upon such a creature as Prince Sassafras. He was making a basket of reeds and grasses, and was twining wild flowers about it to give it variety of colour, and the Prince, desirous of redeeming his character, suggested certain alterations in the arrangement of the flowers. He had a good eye for colour and harmony of design, and Robin condescended to profit by his suggestions. The basket being finished, Robin held it out at arm's length to admire it. The Prince asked whom it was for.

"It's for Bluebell," replied Robin.

And, inspired by the name, be sang, "Bluebell! Bluebell!" to many kinds of airs, sweet and rough; and whistled, "Bluebell! Bluebell!" to the birds and the trees and the dancing stream.

"Bluebell!" echoed the Prince inquiringly.

"My little sister. Mother says she's the darlingest darling as ever drawed breath, and father says she's the prettiest pretty as ever opened a pair of blue eyes. And I say, Bluebell! Bluebell!" And he sang and whistled again.

"She is the same as you are, I suppose?" said the Prince.

"What do you mean?"

"Why, her clothes, now—something like yours?"

"Something like," was the reply.

"Hm!" said the Prince reflectively, and with no intention of giving pain. "Bluebell can't be very well dressed, then."

Robin, who was more familiarly known as Ragged Robin, for the reason that he was always tearing his clothes among the briers and brambles, looked down upon his common jacket and trousers, and for a moment a shadow of discontent rested on his face; but a sunbeam saw it, darted down, caught it in its embrace, and dissolved it. The Prince saw the shadow appear and disappear; and be said aloud, but in a musing tone, as though he were speaking to himself.

"Ah, now I know what sunbeams live on."

"On what?" inquired Robin.

"On shadows," replied the Prince.

Robin laughed.

"Why do you laugh?" continued the Prince. "Because sunbeams live on shadows? I saw a sunbeam just now swallow a shadow from off your very face."

"I didn't see it," grinned Robin.

"I daresay not," observed the Prince philosophically; "we often don't see what's right under our noses."

From right under the Prince's nose Robin plucked a flower.

"Look here," he cried; "what is this?"

It was a small flower, with a green cup, and with its inner covering shaped like a wheel; but its petals were glowing with the loveliest dyes of the loveliest sunset. Prince Sassafras was enchanted with its rare beauty.

"What is it?" repeated Robin.

"A flower," replied the Prince, in a helpless tone, for he knew that that was not the answer expected from him.

"Any numskull could see that," exclaimed Robin. "But what is its name, and what is it good for?"

"I don't know," stammered Prince Sassafras.

"Don't know your poor relations!" (Which reproach, as botanists will know, had a deeper significance than either Sassafras or even Robin was aware of.) "The pretty pimpernel! Why, this is the poor man's weather-glass! In the morning, when it is going to rain, it folds itself up in its green cup, and you can't see a bit of its golden colour. Don't know the pimpernel! You're a wiseacre, you are, with your shadows!"

The Prince felt the justice of Robin's rebuke, and acknowledged the wit of the retort.

"You are wiser than I am," he murmured.

"You're a queer one," said Robin, perplexed by these variable moods. But, his thoughts reverting to a subject which had given him pain, he cast envious eyes upon the Prince's clothes, which, although they were the commonest the Prince could find, were grand in comparison with those of his companion. Then Robin looked down upon his own hobnails and corduroys. "But your clothes are fine," he sighed.

The Prince was inspired by a whimsical idea.

"Shall we change?" he suggested.

"I don't mind," said Ragged Robin, with sparkling eyes.

"And, without more ado, the boys stripped to the skin.

"I think I'm as fine as you," said Robin, "without the clothes."

"Finer," assented the Prince, comparing himself with Robin critically. "You are better shaped, and stronger too. I wish I had such a chest as yours."

"And I'm as white as you are!"

"Quite as white—except your hands and face."

"Blame the sun for that," remarked Robin sententiously,

Then they donned each the other's clothes, and each went his way. Prince Sassafras walked straight to the old elm-tree, and climbed it, and clapped his hands in triumph as he sat on his throne. When he clapped his hands, the birds flew out of their nests in sudden alarm, and perched themselves on far-off branches. The old birds solemnly watched him, with their heads set rakishly on one side, and he, sitting very still, watched them. Then, without moving his limbs, he began to whistle and chirrup softly; and the birds, after much listening, questioned each other in melodious notes, and, deciding that he was not an enemy, returned to their homes, and peeped at him through lacework of moss and twig. All this was very delightful to the Prince; never in his life had he spent so pleasant a day. The earth, the air, the clouds, the tree in which he sat, were filled with marvels, and his mind became attuned to the grand works by which he was surrounded. The day grew drowsy, and the hum of insect life sounded in his ears like a hymn. Suddenly his reverie was disturbed by a great commotion below. He looked down, and beheld a number of his attendants and timeservers in anxious consultation. They were dirty and dusty, and their faces had lengthened considerably during the last few hours. Altogether they were in a sad plight.

"They have been looking for me," said the Prince, chuckling.

As they stood debating and stretching out their fingers in all directions, one of the party who was especially obnoxious to the Prince, and who, being much heated, was wiping his bald head, suddenly shrieked very loudly, and clapped his hand to his head. The others thought he had been attacked by an idea, and they waited for him to deliver, holding out their arms and inclining their bodies, in the attitude of persons who expected to catch a prize. But something more tangible had caused his alarm. The Prince, finding a marble in the pocket of Robin's trousers, had dropped it on to the tune-server's bald pate. The unfortunate attendant looked down for the cause, and then looked up to heaven, and in this way the Prince was discovered.

"Come down," they cried wrathfully, "Come down, you young ruffian! How dare you sit in the Prince's tree?"

For so they had dubbed it from the day he had first tried to climb it. He had, in a measure, made it sacred in their eyes by his notice, and they had even debated the advisability of hedging it round with gilt palings, as being immeasurably superior to the other trees, and as being a kind of historical landmark.

"Go away, you old stupids!" the Prince called out in reply, making his voice very rough, so that they should not recognise it. "Don't you see that I am enjoying myself!"

They shook their fists at him, and he shook his at them. He was prodigiously elated. The birds hopped out of their nests, and observed the disturbance. They chattered about it, and gave opinions. The younger ones, with youthful enthusiasm, would have sided with the Prince, as their sympathies were with him, but the older and wiser birds said, "No; let us stand aside and arbitrate."

"If you don't come down," bawled the attendants, "we'll put you in the stocks!"

"If I don't come down," bawled the Prince, "I can't for the life of me see how you will manage it."

They gasped at him, and at each other, and one bolder than the rest commenced to climb the tree. Prince Sassafras broke wood from the branches, and threw the pieces at him so vigorously, and with such good aim, that he was glad to get safe to earth again.

"Ha! ha! ha!" laughed the Prince; and a scaly old jackdaw, who had not laughed for ever so many years, flew out of his nest, and echoed feebly, 'Ha! ha ha!' after the fashion of doddering old lunatics who strive to ape youth.

The attendants were more and more furious.

"Read the Riot Act!" they cried.

In accordance with that wisdom for which they were celebrated, and which provided for the fitness of all things, the time-server with the weakest voice read the Riot Act elaborately. That part of it which impressed his hearers most powerfully was contained in the word Whereas. Whenever he came to that magic word, he piped it out with a mighty effort at the top of his voice, and those who surrounded him—who had always suspected that Whereas was the fount of justice, and now were sure of it—bowed their heads worshipfully as to a talisman which contained the pith of all law. Prince Sassafras listened with profound attention until the reading was completed.

"Hear, hear," he said, clapping his hands in applause. "Now I will come down. The moral force that lies in Whereas has conquered me, and I'm getting very hungry."

Down he scrambled, hand under hand, as active as a squirrel, and as though he had been accustomed to climb trees all his life. Down he plumped in the midst of his attendants, and raised such a dust that they ran a few paces away to save their eyes. He leaned his back against the tree, and looked at them jauntily. As they advanced towards him with wrath in their countenances, with the intention of seizing him and treating him roughly mayhap, he spoke to them in his natural tones, and bade them be careful, for he was rather tired.

"It is the Prince!" they cried, in amazement.

Their manner was so comical that the Prince laughed long and blithely, and the doddering old jackdaw made such an effort to renew its youth that it shed its last feather, and almost shook itself into a fit.

"And in these clothes!" they exclaimed, as they surrounded him. "He has been waylaid and robbed!"

The Prince held up his hobnailed boots for inspection, and then walked slowly up and down among them, to give them the opportunity of admiring the easy fit of his corduroys. There were no bounds to their indignation.

"Where is the robber?" they shouted. "Can your Royal Highness describe his person?" They glared about in such a state of excitement, that one might have fancied they were going to lay violent hands on one another.

"It was a nut," said the Prince.

"A nut!"

"A nut, that fell upon my head as I was walking along. It hurt me, too."

"Surely, your Royal Highness," said the attendant upon whose bald pate the Prince had let the marble fall, "surely they drop about to-day. It must have been a nut that fell upon my head." He rubbed the sore place as he spoke.

"Thank your stars it was not such a nut as mine. Listen." And the Prince illustrated his words with appropriate action. "Down dropped the nut. I picked it up, and cracked it—you know how fond I am of nuts! But when the cracked shell was between my teeth, I felt that something living was inside. I spat it out quickly, and the kernel rolled from the shell, and looked at me, in the shape and likeness of a man. And as it gazed at me I became fascinated by its beauty, and it grew and grew until it was as high as my knee; and there it stopped growing. It was dressed in the brightest green and scarlet, and its eyes were rimmed with purple. It claimed a distant kinship with me, and said, indeed, that it was one of my neglected poor relations—which I could scarcely credit, so far as regards the plea of poverty, when I looked at the creature's beautiful clothing. But these things want searching into, my lords; and it saddens me to think that many of us die, and have been blind through all our lives. It told me so many wise things, and taught me so many strange lessons, that I was as one entranced. I remember no more about it except its name, which some of you may know. It was Pimpernel."

"Pimpernel! Pimpernel!" they mused, and questioned one another, but no one had heard of such a creature. "One of your Royal Highness's poor relations, indeed! Are they not all provided for? This Pimpernel is a beggar—an impostor! But we will find him. Call out the guards, and let the woods be searched."

"Shut up the bell-shaped flowers!" shouted the Prince, mimicking them. "Place a sentinel at every tree, and build a fence of forget-me-nots around the forest."

Some were actually about to see to the carrying out of these orders, when he called to them.

"Hold! I was but jesting! As you love me, do not make a fuss."

They clustered about him at this adjuration. As they loved him! Two Grand Old Sticks, with white heads, giggled with delight, like a couple of foolish schoolgirls, at the ecstatic honour of being thus appealed to.

"Do not heed what I have said. No one is to blame but I, I give you my honour, so let no word be said. Regard this as a freak, and let it be a close secret between you and me. Do you understand? Mum! If you break my confidence," he added, with a malicious twinkle, "I'll cut down all your salaries when I am King. Now, then, let us pledge each other. Take the word from me. Mum!"

They stood before him with their fingers on their lips, and took the oath. Mum!

"'Tis well," said the Prince, quoting from the last original drama; "let me rest a while."

His back was still against the tree, and he looked about him with regret that so glorious a day was nearly at an end. Directly in front of him, but at some distance on an eminence, was the west wing of the palace, behind a fretwork of trees. The sun was setting, and massed troops of fiery shadows were invading the palace, and as they passed the windows glared out with threatening eyes.

"How beautiful!" sighed the Prince.

His attendants urged him to depart.

"We are ashamed to see your Royal Highness in such mean attire."

"And yet I enjoy," he said. "Look above you at the clouds. What lovely fancies dwell in them! Here are an angel's wings, stretched forth beneficently, blessing mankind in fustian and silk. See their feathery tips, and the pale purple folds that hide the body of the glorious being. Here is a great hill, with a many-turreted castle built on its peak. The landscape opens—the hill grows smaller, the castle larger. A forest of pollards rises up beyond it, overshadows it, dissolves it. The airy trees and land melt into a lake, on the bosom of which are reflected the colours of a myriad sapphires and rubies, and the soft glow of many-tinted pearls which lie beneath. See—night is coming; the shadows creep into the lake's breast. Weeping willows rise on either bank—rise and overlap the water. They bend towards each other, from the opposite banks, with melancholy gracefulness. Is it not beautiful?"

They gazed above and around, and then at one another. They saw none of these things. Their unsympathising looks chilled the Prince.

"There go my fancies," he said bitterly, pointing to some butterflies that were flying home. "And here is a troop of caterpillars, creeping, O, so slowly and lazily up the old elm. Come, let us creep to the palace, caterpillar-like!"

THIS was but the beginning of the Prince's truant-playing. A second time he evaded his attendants and time-servers, and they did not discover him until near the close of day. Again he pledged them to secrecy, and then they were to a certain extent in his power. Then he played them a trick. He knew that they were curious to find out where he went to, and that they had laid plans to follow him.

"It really must be seen into," they said to one another, "for our own sakes as well as his. Youth is ever rash."

"His Royal Highness is so cunning," cried one.

"We must use stratagem," said another, with his finger to his nose; "if we can't find out by hook, we must by crook."

But neither hook nor crook was of use to them, as it turned out. Prince Sassafras stole away one day, and knowing that they were following him, he led them a pretty dance. He played them a pretty trick, too. He came to a morass, and jumped across it. They, not aware that the ground was soft, jumped as he jumped, but not being so lithe, stuck in the middle. Then, as they were floundering in the mud in their silk stockings and dandy pumps, he turned upon them, and laughed heartily at their comical appearance. They were in a nice plight!

On the next occasion, he knowingly threatened to tell upon them if they did not let him have his way, or if they betrayed him.

"In which case," he said saucily, "I should say you will be discharged for not taking better care of me." With this fear upon them, they concealed his delinquencies, grating at the same time under the burden of the fear that they we between two stools. For, supposing that one day the Prince should fail to present himself, and supposing that any accident should happen to him while he was out of their sight, the whole country would rise against them for having betrayed their trust. Fortunately for them, however, nothing of this sort occurred.

"If you keep faith with me," said Prince Sassafras to them, one day, when they were in a more that usually terrible pucker, "I will keep faith with you. Always after I have enjoyed my run, you will find me under the dear old elm. Come, now; is it a bargain?"

They had no choice, according to their notions, but to enter into this compact.

"After all, you know," he said, "I have somewhere read that boys will be boys."

"But your Royal Highness is Prince," they urged.

"And not a boy?" was his reply. "Well, I don't understand that."

They tried to make him understand it; but they could not beat it into his obstinate head.

"Tell us, at least," they begged, "where your Royal Highness goes to."

"No, I will not tell you; I go to different places, and I choose to keep their whereabouts to myself." He answered them very independently, for he saw that he had them in his power.

"What does your Royal Highness do when you are out of our sight?"

"Nothing wrong, I assure you. Nothing wrong, on the honour of—a Prince!"

After that, of course, there was nothing more to be said. The honour of a boy they might have doubted, but they did not dare to doubt the honour of a prince. So they were compelled to assume an appearance of content, although they were far from easy in their minds.

It was with Ragged Robin, and at Ragged Robin's home, that he spent his stolen hours. His station was not known; it was supposed that he lived in the neighbouring town; and it was plainly seen that his circumstances were better than those of Robin's parents. When he was asked his name, he hesitated a moment, and then said it was Myrtle; so as Myrtle he was known to them. He became a great favourite with them, as much because of his blithe cheery manner and handsome face as because he made them small presents occasionally. They were simple country people, happy enough in their way, and contented with their station in life. One thing certainly would have made Robin's father as happy as the day was long, as Robin had said, and that was the two shillings a week more which Robin had spoken of. It was his only grievance, and he spoke of it invariably as if two shillings a week more would set everything in the world right that happened to be wrong. Perhaps it may be recognised that the burden of his grievance is not an uncommon one. Their home was exactly as Robin had described it—very small, very humble, and very pretty. Bluebell, a child of about eight years of age, was the prettiest and most engaging creature that Sassafras had ever seen, and deserved all the praises that Robin had bestowed upon her. She and Sassafras became great friends; and when the fond mother had sufficient confidence in Sassafras, she allowed him to take her blue-eyed darling for a ramble in the woods. He learned a great deal from these poor people, and was entirely happy in the society of his humble friends. The hours he spent with them were the brightest in his boyhood's life.

Near to their cottage lived two friends of theirs—an old woman and her son; he known as Coltsfoot, she as Dame Endive. Proud, indeed, was this old woman of her son; and she had every reason to be, for Coltsfoot was of a rare type: a grave and thoughtful man, too serious for his years in the opinion of some, but earnest, whole-souled, and with fine susceptibilities. If Ragged Robin was learned in the life of the woods, and spoke of their inhabitants as one does of familiar companions, Coltsfoot war learned in the higher life of human creatures. He had studied deeply among them, and was wiser than he who gains knowledge from books. More than this: he did not learn by rote. The eyes of his mind were open wherever he walked; he was a just man, with a tender heart. He was a poor schoolmaster, and he worked among the poor, and was regarded by them with respect and admiration; with affection also, for he had in his studies gained some knowledge of medicine, and he administered to the sick without a fee, where to pay one would have been a hardship. Many and many a night did he sit by the bedside of a sick neighbour, and cheer body and soul by his kindly words and deeds; and when his task was done, he would put aside the offered reward with a gentle hand, and say, "Nay, neighbour; another time, when you are better able to afford it;" well knowing that that time would never come. His was the unclouded charity which springs from an unselfish compassionate nature.

Between Coltsfoot and Sassafras an intimacy sprang up, which ripened into friendship. Coltsfoot was attracted by the bright wit and lively fancy of Sassafras, and Sassafras was not long in discovering that here was a man of a higher order than those among whom he was accustomed to move.

"You know a great deal," said Sassafras; "and yet you are not very old."

"I am more than thirty years of age," replied Coltsfoot.

"How did you learn all you know?"

"I taught myself chiefly, I think," said Coltsfoot, with a smile.

"One can do that, then?"

"Surely; and if you read the history of men, you will find that that kind of teaching seems to bear the best fruit." He said this candidly, not as a boast, for he was not vain-glorious, but as the sober truth.

"Then to be born great—" mused Sassafras.

"Do you mean, to be born rich and in a high position?"

"Yes; to be born great, in that way, does not make one great?"

"Unfortunately, no."

"Why unfortunately?" pursued Sassafras.

"Because those who are born thus have so much power for good in their hands that, if they were really great, the world would be better than it is."

"It is not a good world, then!" sighed Sassafras.

He was young; his mind was pliable and amenable to kindly influence, his nature was susceptible and tender; not to be wondered at, therefore, that out of his regard and admiration for Coltsfoot, he was ready to accept Coltsfoot's views without question; ready, indeed, to accept them in a more exaggerated sense than Coltsfoot intended.

Coltsfoot laid his hand kindly on Sassafras's head.

"It is a good world," he said, with somewhat of seriousness in his tone, as though he wished to impress Sassafras, "a good world, in every sense; but there are many wrongs and injustices in it which are allowed to exist, and which might with ease be removed by those who are born to greatness." His words sank into Sassafras's heart. "But in the mean time," Coltsfoot continued, with a sweet and serious smile, "we will go on and work, and not lose heart because things are not as we wish them to be."

"You are never idle," said Sassafras.

"Do you think man was born to be idle? Have you not heard that work is God's heritage to man?"

"No."

"It is; and the best and sweetest heritage. The idle man is like a weed in a field."

"Then one who does not work—"

"Fulfils not his mission. The world would benefit by his absence."

Thought Sassafras: "I wonder what some of my time-servers would say to this? Read the Riot Act, perhaps."

Such conversations as these were not uncommon between Sassafras and Coltsfoot; and they led the Prince into new fields of thought. What he saw, also, in his wanderings with Coltsfoot stirred him strangely. He had been taught to believe—not directly, not in plain words, but insidiously and by false inference—that the poor were of a different order from that of which he was the chief ornament. He expressed this to Coltsfoot, not as his own opinion, but as he heard it.

"Come with me," said Coltsfoot.

And the Prince and the poor schoolmaster went together into the houses of the poor, and Coltsfoot showed Sassafras the virtues and the good that were in their lives. Had the Prince been of Coltsfoot's age, Coltsfoot would probably have shown him more of their vices, so that whatever judgment he formed might have been formed upon a thoroughly correct basis; but Sassafras was a boy, and Coltsfoot (apart from his consideration for Sassafras's tender years) was anxious to show the best side of those he loved and compassionated. Yet he did not utterly conceal their vices; he spoke of them with gentle words of commiseration, saying how, in many instances, the poor were like creatures walking in the dark, being, in most instances, judged by a higher standard than that up to which they were educated, or were like helpless flies attracted by the glare of lights.

It was while the Prince's mind was filled with the theme that he said to his time-servers:

"What do you think of the poor?"

They shrugged their should as they were wont to do at any subject that was indifferent to them and answered carelessly:

"They are an ungrateful class."

"Why ungrateful?" questioned the Prince. "For being allowed to live?"

They evaded explanation by remarking, "Your Royal Highness is too young to understand these matters."

With this he was forced to be satisfied, for they would return him no other answer. In truth, they were puzzled and perplexed by his whims and whams, as they termed them; strive as they might to educate him in the right way, he refused to think as they bade him. To them it was inexplicable that he would not follow them blindly through the path of roses, but would bother his head about the nettles. This suggestion concerning the roses came from the Court Poet, and was highly praised by all but the Prince.

"You have forgotten the thorns," he said.

"They are not for your Royal Highness," was the answer he received.

"If weeds and thorns exist," he remarked sagely, "they must he minded."

"It will be our pleasure and duty," they said, "to clear them from your Royal Highness's life; they shall not touch your sacred person."

"My sacred person," he repeated, under his breath, and trembled at the words. To him they sounded like profanity.

Still he persisted, and was then told that it was not seemly in him to allow his mind to be thus disturbed.

"These things are not for princes," they said.

After his usual fashion, he flew from one to another for counsel and assistance. In some rare way there had come to this young Prince an intense and earnest desire to know the rights and wrongs of things, and he found himself battling in a sea of doubt because of the conflicting views that were presented to him. He asked Coltsfoot about the "divine right," which he said he had heard was the especial attribute of kings; and Coltsfoot showed him, first, not only the folly but the blasphemy of the term, if taken (as it is too often taken) in its literal sense; and next, to what great ends it might be used, if rightly understood. Raising some up, and bringing some down, Coltsfoot brought all persons on a level, so far as regards the laws and principles of humanity and morality and the proper living of life. Coltsfoot saw that Sassafras was in doubt as to his opinions, and without in the least suspecting the lad's exalted station, he opened his heart and mind to the lad whom he had learned to love. He implanted in the lad's soul the purest seeds of honour and religion, and did his best to lay the foundation for a good life.

These conversations occurred when the snow was falling, early in December, and Coltsfoot, who never missed an opportunity of enriching the lad's mind, told him wonderful things concerning the soft flakes: how that each crystal was of the most exquisite shape and form, transcending in beauty the finest and most elaborate work of man's hands; how that, as it lightly covers the earth, it keeps the soil beneath it warm, protecting it from the nipping cold which would destroy the treasures sleeping in its breast; and many other particulars which need not be set down here.

"But for the snow," said Coltsfoot, "we should have no primroses."

"And until to-day," said Sassafras regretfully, "I have looked upon it with a careless eye."

"The fashion is a common one," observed Coltsfoot; "many men grow blind by looking at the sun, and never see the beauty of the stars."

"Nor feel the peace that is in them," added Sassafras. "I have sometimes thought, as I have gazed at them from my window on a still night, that I should like to pass away into the depths where they lie, and float among them in eternal peace."

"The nights are not always still," responded Coltsfoot: "storms come and wild winds; the clouds are tossed and whirled on the wings of the wind; and if a star is visible, it hangs disconsolately and drearily in the heavens, like a soul in doubt."

Sassafras in a timid tone repeated a few lines of a poem he had composed, but had never had courage to show his friend:

"I stood upon a dark and dreary shore,

And voices rose upon the viewless air,

And sighed, 'Ah, nevermore shalt thou know peace!

Evermore shalt thou be tossed on this dark shore,

Till death shall claim thee for its own;

And then, thou scornful doubter, what shall be

Thy after to mortality?'"

Coltsfoot suspected the authorship, and notwithstanding the boyishness of the effort, listened thoughtfully to the lines; he traced in them the doubts and yearnings of a young sensitive soul, and with a peculiarly sweet smile, he said:

"You sigh for peace. Well, peace will come to all of us to-morrow."

"To-morrow?"

"Yes, for to-morrow all of us must die."

"And then?" asked Sassafras, with eager yearning.

"A new birth," replied Coltsfoot, passing his arm around Sassafras with a kind and affectionate motion, "to be believed in as we believe in the wisdom which designed this wondrous work, the world; to be worked for, so that we may fit ourselves for it, with faith and cheerfulness and good intent."

Scarcely a week after this conversation, orders came to the palace that the Prince was to set forth on his travels early in the ensuing year. His tutors and time-servers were delighted. "No more truant-playing then," they said to one another; for the Prince's truant holidays had grown so frequent lately as to cause them more trouble and anxiety than ever. Sassafras was not pleased at the idea of leaving his friends, but he knew that it would be vain to resist. He made up his mind that he would see them once more before he left; but day after day passed, and he found no opportunity to escape. At length the opportunity came; or rather he made it, and, singularly enough, on Christmas-day, which happened to fall that year on the Sabbath.

HE met Coltsfoot on his way. Coltsfoot had a bundle in his hand, and a bunch of winter roses.

"I was coming to you," said the Prince. Coltsfoot nodded and smiled. "I would not go away without seeing you once more, and bidding you good-bye." The Prince's lips quivered as he uttered these words.

"Good-bye!" echoed Coltsfoot. "You are about to leave us, then?"

"Yes. I am to be taken from those I love best in the world; I am to be torn from the scenes and the friends that are dearest to me. Pitiless fate! Should I not be content here to live and die?

"Why does not the world stand still," said Coltsfoot, in a tone of gentle reproof, "and why does not old Time stop the running of his sands to prolong our happy moments? Why are we not always young? why are the skies not always bright? why do the flowers wither and die? why is it not for ever summer?"

"I understand you," answered the Prince. "You think me weak for complaining. I do not ask for these impossibilities. Nature must run her course—seasons must change, flowers must die. But they will come again, and I shall not be here to welcome them. Summer's sweet breath will kiss these dear woods before many months are passed, and I shall be far away."

"Your regrets are natural," responded Coltsfoot, "but you must not magnify them into wrongs. I shall miss you, dear lad, for I have grown to love you!" The Prince raised his face, now flushed with pleasure at the declaration, eagerly to the more sober face of Coltsfoot. "Now is there not balm in Gilead? Is there not comfort in the thought that we have fairly won love and respect, and that we hold a place in the hearts of friends whose faces we may never look upon again?"

"Do not say that!" cried the Prince, covering his eyes with his hands. "O, do not say that!"

"Nay, nay, nay! Life has its duties, and we must perform them with cheerful minds. Life has its griefs, thank God! and we must bear them with resignation. Yes, thank God that life has its sorrows. There is sweetness in them, believe me. Suffering is the mother of compassion. Hearts might be stone but for pity; life would be harsh without charity. Think—think, dear lad! and be grateful for everything in which there is no shame."

"Your words strengthen me," murmured the Prince.

"Then," continued Coltsfoot, "is it in this place only that summer is to be found? What spot is there in the world upon which the sun does not shine? Dear lad, summer is not here or here—he lightly waved his hand to the south, to the west—summer is here." He placed his hand on his companion's heart. "Ah, we are not grateful enough. We do not know how happy is our lot, in comparison with the lot of others. How often have I been shamed into humbleness by the contemplation of the lives of those who are not blessed as I am blessed!" They were walking in the woods towards a village; the trees were lightly covered with snow, which had fallen during the night; the air was keen and fresh and sweet. "If a multitude of people were before me on this fair Christmas-day, I should be tempted to preach them a sermon in six words: Be humble; be grateful; be charitable. And should these few words bear fruit, the sermon would be long enough and good enough. You cannot remain with me much longer, I suppose, today?"

"I have come to spend the day with you," replied the Prince, "if you will let me."

"You may?"

"Yes, I may, as it is the last day we shall have together for a long time. But I will come back."

"You will come back a man. I shall be always here, I think. My way of life is marked out for me, and it lies within a small circuit."

Thus conversing, they arrived at the village, and halted at a small cottage, which bore signs of decay. The doorway was so low that Coltsfoot, who was a six-foot man, had to stoop his head upon entering; a little girl, who looked like a wise little woman, and yet was not more than six years of age, was sitting in a low chair, hushing a baby to sleep. The baby may have been three months old, and the nurse might have been her mother, so womanly were her ways. Another little girl, two or three years younger than the nurse, was also in the room, which was clean and very poorly furnished. A few paper pictures, cut from cheap prints, were pasted on the walls, and three violins were hanging in a corner. The children looked at Coltsfoot, and smiled a welcome, staring bashfully at Sassafras.

"Well, little ones," said Coltsfoot, "and how is mother this morning?"

"She is a little better," answered the eldest girl "so she said."

"That is good," he said, rubbing his hands cheerily. "Here are some winter roses for you."

A thin voice from an inner room, which was the only other room in the cottage, asked who was there.

"It is I," called Coltsfoot; "I will come in presently and see you. Well, pet, and what have you to say?" This to the second little girl, who was climbing on to his lap. The baby was asleep by this time, and was lying in a cradle. The eldest child, being released from her burden, was arranging the flowers in a broken jug, and admiring them with eyes too sadly bright for one so young.

"We've got a pum-pudden for dinner," said the child on Coltsfoot's lap.

"Ah, that's a fine thing," responded Coltsfoot, kissing her, and setting her down. "Go and shake hands with the young gentleman, and tell him your name."

"I'm Lucerne," she said, standing by the Prince's side, and gazing up at him.

"And baby's name is Daisy," added Coltsfoot, "and our little mother here is Iris."

Iris calmly shook hands with Sassafras, and then resumed her duties.

"Our little woman," continued Coltsfoot tenderly, "does everything in the house, and is quite wise. She can scrub and cook and mend clothes; and she can do something cleverer than all these—she can play the fiddle."

"And so can I," put in Lucerne.

"And so can Lucerne," Coltsfoot assented; "and I shouldn't wonder, when Daisy gets to be as much of a little woman as her sisters, that she will play the fiddle also. Now I'll go and see mother."

He went in to the sick woman, and remained with her for a few minutes, Sassafras in the mean while making friends with Iris and Lucerne. When Coltsfoot and the Prince left the house, they left sunshine behind them. On their way, Coltsfoot related the story of these poor people. It was simple enough. The father had died nine mouths ago, leaving his family destitute.

"That was surely wrong," observed Sassafras.

"Undoubtedly; but you must not blame the man. He worked from morning to night, and earned the barest pittance for his brood. He had no extravagances and novices; he was not even a beer-drinker. In this respect, he was useless to the State, and useless to those voracious creatures who distil and brew, and whose appetites grow by what they feed on."

Sassafras did not understand these allusions, and Coltsfoot continued:

"The breadwinner being gone, the wife was left helpless. It is a mystery to me how some poor persons manage to live. They have nothing, and can earn nothing, and yet they manage to rub on some how. Deep in the earth lies the gold, hidden in darkness; and precious stones are found in roughest places. So among the poor and in the roughest places, there must be running veins of sweet humanity, which are never idle and never worked out. There can be no other solution to the mystery. The woman did some little work, until she was near her confinement with Daisy. Then things began to look very bad indeed, and Heaven knows how matters might have ended, but for a certain little fairy in that house whose name is Iris."

"Iris! that child!" exclaimed the Prince. "Why, what could she do?"

"Iris, that child, did a brave and wise thing. Her father had taught himself the violin, and she, young as she was, had learnt from him how to handle the bow. You saw her father's violins hanging on the wall; the wife had parted with nearly everything, so that the partnership between the bodies and souls of her children should not be dissolved, but with a weak womanly tenderness she clung to her dead husband's violins as though they were living Creatures, determining that they should be the last things to go for bread. In the dead of night she may have fancied she heard their strings vibrate, speaking to her of old times—they had loved each other, this man and woman and perhaps the strings of her heart were touched responsively.

"Iris, one morning in the spring, took a violin from the wall, and quietly went out of the house. I saw her that morning; she was playing in a byway, where but few persons passed. 'Why, Iris!' I cried. She opened her right hand, and showed me a few coppers which, even in that but little frequented place, the charitable poor had given to her as they passed. Then I understood it all; the little six-year-old maid had taken upon herself the duties of breadwinner, but was not yet bold enough to stand where many people were. That courage came soon, and she taught Lucerne to play a little; and day after day the two mites go out, and play the old tunes their father played, while their mother lies sick at home. The people have grown very fond of them, and give, out of their small store. When Daisy grows up into a woman of two years old, I have no doubt she will go forth with her sisters to fight the battle, armed with violin and bow. Already Iris gives her the fiddle to nurse, instead of a doll. And now you have the history of that humble household. Maybe you may find some heroism in it."

They had dinner at Ragged Robin's house, Coltsfoot's mother being of the party. A happier group was never assembled beneath a roof. The fare was plain and sweet, the walls rang with merry laughter, and the entire absence of ceremony contributed vastly to the Prince's enjoyment.

"I think," he whispered to Coltsfoot, "that the poor have many pleasures which the rich do not taste."

Coltsfoot smiled; he was satisfied that his young friend was learning good lessons in a good way. The family wished Coltsfoot and Sassafras to remain with them the whole of the day; but Coltsfoot said that they had many things to see, and that they would return in the evening. In accordance with Coltsfoot's wish, Sassafras had not told them that he was about to leave them.

"Wait until to-night," Sassafras said; "it might spoil their pleasure to know too soon. They have but few holidays."

"Then you really think," asked Sassafras, "that they will be sorry to lose me?"

"I am sure so;" replied Coltsfoot.

Sassafras found some consolation in this; it sweetened his grief. Coltsfoot took him into the City, where he witnessed many strange scenes, and where he saw the poor and helpless in their best and worst aspect. Wherever he went he met with touches of humanity which brought sweet light into the darkest places—wherever he went he saw the poor helping the poor. Coltsfoot was welcomed everywhere, even in the worst of places, for all recognised in him a friend. They walked through a nest of bad narrow thoroughfares, a very maze of shrunken diseased courts and lanes, in which it was almost impossible for virtue not to lose its way. Sassafras was frightened at the sights and sounds which greeted him: he clung closely to Coltsfoot, who conducted him safely through these hotbeds. Swarm of children were there, learning; swarms of men and women were living the lives they had been brought up to in their childhood; doing their duty, as one bitter cynic among them said, to the best of their ability in that sphere of life in which it had pleased God to place them.

"There is nothing to fear," said Coltsfoot; "they will not harm us."

"Where do all these people live?" asked Sassafras.

"In cellars," replied Coltsfoot, "in garrets, in rooms where heaven's light is veiled, huddled together like rats, clinging to each other for warmth like vermin. O, that I were a ruler, if only to accomplish one task!"

"What task?"

"To sweep away these nests of corruption—to purify the streets. Sewers breed rats. But these living things are human creatures, God help them! Dear lad, I have my doubts as well as you. Sometimes when I visit these places, knowing that they have existed for scores of years, knowing that they will exist for scores of years longer, knowing that thousands and thousands of helpless babes will be born here and educated to lives of infamy, I doubt whether under such circumstances man can be held responsible for crime, and I am driven against my reason to ask whether civilisation is a curse or a blessing. Only to you, dear lad, would I express these doubt; for I know the danger that lies in them?"

These words were as painful for Sassafras to hear as they were to Coltsfoot to utter, but they were prompted by indignant pity, and Coltsfoot could not restrain the utterance of them.

They emerged into the wider thoroughfares, and—in the brighter aspect of the space in which they now moved, and the brighter prospect of pleasant hours presently to be spent with Bluebell and her kindred—were striving to shake from their minds the dust of melancholy which the scenes they had witnessed had engendered, when a babel of voices and sounds of hurried steps in their rear caused them to turn. Some twenty men and women, with alarm and pity on their faces, clustered about Coltsfoot and Sassafras, and began to speak all at once.

"I tell you he is a doctor. I tell you he isn't. He is; he isn't. Well, ask him. He's a good sort anyway, and is likely to know something about it."

Coltsfoot held up his hand, to stop their unintelligible babble.

"I am not a doctor according to the law," he said, "but I have some knowledge of medicine."

"There! there didn't I tell you so?" exclaimed those who were right to those who were wrong.

"But what special thing is it," continued Coltsfoot, "that you say I am likely to know something about?"

"Death," said a man, stepping forward. "That special thing."

"Explain yourself."

"You know Death when you see it," demanded the man somewhat

"I do," replied Coltsfoot gravely.

"So do I; these ignorant cattle don't. The woman's dead," said I, with half a look at her. "But they wouldn't believe it. So they run after you, to prove me a liar."

Before the man's last words were uttered, Coltsfoot, with Sassafras by his side, was retracing his steps towards the narrow courts and lanes. The mob of men and women, the numbers of which had by this time considerably increased, led the way into one of the foulest of the thoroughfares, the entrance to which was arched; the rookeries it contained were of the vilest character, and were fit only for vermin to breed in. In a garret, in one of these dens, lay a woman on the ground—a woman so thin and emaciated as to cause sighs of compassion to escape from the breast of Sassafras. Coltsfoot knelt by the side of the woman, whose only covering was a brown gown, torn, tattered, faded—fit for a dung-heap.

"She is dead," said Coltsfoot.

The man who had first pronounced her so cast a look of triumph at the doubters.

"What was her complaint?" asked Sassafras, in a whisper to Coltsfoot; "but his whisper was heard, and the question answered by the man, who lifted the woman's bare arm, and ran his hand along the sharp bones.

"Starvation, my boy," replied the man; "that was her complaint. A pretty time of the year to die of that disease, eh?"

"It is true, I am afraid," said Coltsfoot, answering Sassafras's eloquent look of pity. "But what is this? A child?"

Truly, his eyes had lighted on a child, a baby of six months, who was asleep in a corner of the room. The baby was covered by a piece of rough sacking.

"Ah," said a woman, "this is Dick—little Dick."

Coltsfoot took the child in his arms, who, for a wonder, was clean; this was clearly to be seen, for when Coltsfoot let the piece of sacking fall to the ground, the child was discovered to be perfectly naked.

"Give him to me," said the woman, and as she relieved Coltsfoot of his burden, "the baby opened his eyes, and gazed upon the group, and upon the body of his dead mother lying on the ground.

"Little Dick!" exclaimed the woman tenderly. "Cunning little Dick! I'll take care of him tonight, sir."

With sad hearts, Coltsfoot and Sassafras walked away from the fevered thoroughfares towards the country-lanes.

"Cunning little Dick!" mused Coltsfoot. "Poor naked little mortal! If you happen to see him when you return from your travels, what will he have grown into? But I know—alas I know."

He would have been filled even with a deeper sorrow had any foreshadowing fallen upon him of another Christmas night in the years to come, when he and Sassafras and Cunning Little Dick met for the second time, in another place, and under other circumstances.

Night stole upon them as they walked.

"Come," said Coltsfoot, with an affectionate pressure of his companion's arm, "let us banish melancholy thought. We are in a purer air now."

THE heavens were full of stars, which shone brightly through the frosty air. Sounds of music fell upon their ears, and as their way lay in that direction they walked towards it.

"Can you guess who are playing?" asked Coltsfoot, with a bright smile, stepping briskly along.

A little crowd of persons stood around the players, and Sassafras, peeping through, saw Iris and Lucerne with their violins at their shoulders. The little girls bore a great resemblance to each other, but the expressions on their faces were not at all alike. The face of Iris was grave, and she drew her bow across the strings with a thoughtful and serious air; her little body moved slowly and soberly in response to the music. Lucerne's face, on the other hand, was full of smiles and sparkles; her eyes, her feet, her body danced to the music, and she swayed this way and that with graceful joyous motion.

"You see," said Coltsfoot, in explanation, "Iris has the cares of a family upon her; responsibility makes her serious and grave."

The air being finished, the children stood in quiet expectation of reward. They were not disappointed; a good many gave, the gifts being very small. One woman, putting a halfpenny into her baby's hand, caused the little one to bend over to Iris, and directed the gift; and when Iris kissed the baby, the woman herself stooped down to the tiny breadwinners, and kissed them in her motherly way.

"A better scene than the last," said Coltsfoot.

He did not make himself known to the children, but he and Sassafras followed them quietly out of the street. When they reached a retired spot, Iris paused, and tucking her violin under her arm, proceeded with a business air to count their gains. She nodded and nodded again with satisfaction, and then the two children, with their arms round each other's necks, walked home singing softly.

"I should like to say good-bye to them," said Sassafras wistfully; "I may never see them again."

"Don't say good-bye," replied Coltsfoot, "it makes children sad. Wish them a merry Christmas instead. Besides, we shall see them again. They are coming to the cottage to-night."

Sassafras ran after the children, and embraced them, and when he went away left good wishes behind him, and something more tangible, which he slipped unobserved into Iris's pocket. As he and Coltsfoot entered the lane in which Ragged Robin and Blue bell lived, sounds of merriment floated towards them. Ragged Robin's loud laugh could be plainly heard, and when they were closer to the house, Bluebell's sweeter voice greeted them. She was singing a simple song of the season, and Sassafras and Coltsfoot listened outside until the last line was sung, and then clapped their hands in applause, and cried, "Bravo! Bravo!"

All the family rushed to the door, and also some neighbours who had been invited.

"Here they are—here they are!" they shouted; and they had a scramble and a race along the narrow lane after Coltsfoot and Sassafras, who pretended that they wanted to run away. The wrens, in their warm nests in the chimneys, must have been astonished at the noise which awoke them, and as they raised their heads lazily from their beds of brown moss must have looked at each other with an air of, "What's all this about?"

The Christmas party returned to the house in a merry cluster, filling the air with their laughter. Some of the older wrens, who were well acquainted with them, doubtless thought to themselves:

"Ah, that's Ragged Robin's Ho! ho! ho! harsh, and wild, and unruly; and that's his father's creak, like a door with rusty hinges; and that's his mother's cackle, He! he! he! and that is Bluebell's tender voice—her laugh is like music—let us listen a little longer to it; and that's Coltsfoot's Ha! ha! ha!—why, he laughs likes boy tonight; and that's Sassafras's voice, low and soft. What makes it so sad and pensive? He is generally very merry. Ah, if they knew what we know, they wouldn't make so free with him!"

For these discreet old wrens had friends and relations living in the warm chimneys of the King's palace, and were in the habit of visiting them very often—being but flighty creatures, as you may guess; and there they had seen Myrtle in his proper form of Prince Sassafras, and consequently knew of the deception he was practising upon Robin, and Coltsfoot, and Bluebell, and the rest. They chattered about it among themselves.

"What does he do it for?" they asked of one another, without being able to furnish a sufficient explanation.

"It is perfectly inexplicable," said one old wren, who had been born in the royal chimneys—indeed, in the very chimney of the bedroom where Sassafras slept—and whose courtly airs were a sight to behold; she never came to dinner with her feathers ruffled! "It is perfectly inexplicable! I can't make it out. A Prince, who is in the enjoyment of every luxury, and who has his drawers filled with silks and laces and furs, to associate on terms of familiarity with such common persons as Ragged, Robin and his family! With Ragged Robin, who hasn't a second pair of breeches to—"

"Hush! hush!" interrupted a staid old wren who looked after the proprieties.

"To his common legs," continued the court wren, in a stately way; "and with a person like that Coltsfoot, who teaches abc to a lot of dirty ragged brats, and gives medicine and trash to a parcel of old women! Our Prince to associate with such-like! I don't know what we're coming to!"

But an equally outspoken old wren, who had been born in the cottage chimney and who had lived a happy life there, resented this with spirit.

"And pray, madam," she cried to the court wren, "who are you that you should think the Prince demeans himself by coming to us for a few hours now and then? And who are you that you should try to take away the character of honest Robin and our good Coltsfoot? Let me tell you that the Prince is never so happy as when he is with us; I have heard him say so as we were taking away our dinner which he spread on the sill for us."

The court wren cocked her head disdainfully, and looked straight before her into vacancy, as though there were no such bird in existence as the cottage wren. But the cottage wren was not to be put down in this way.

"You!" she continued, "with your stuck-up ways and your grand airs! Who are you, I should like to know! Because you happen to be hatched in a royal chimney, you think yourself of more consequence than your betters!"

In short, they had a desperate quarrel, which was not confined to themselves. All the other birds joined in, and such a chattering and a whistling were heard in the royal chimneys, that it was a mercy something dreadful did not occur to the walls. The upshot of it was that a breach occurred in their friendship, and for eight whole days the cottage wrens and the court wrens were not on speaking terms. It must be confessed that when the quarrel was patched up, it was the cottage wrens who had to eat humble pie; they could not resist the only opportunity they had of hearing the delicious bits of fashionable scandal which the court wrens always had on the tips of their tongues.

Well, these cottage wrens heard Ragged Robin and the rest making merry on this Christmas night, and made their remarks on what was going on. But they did not see everything. The best room in the cottage was lighted up by means of wooden hoops, which were suspended flat from the ceiling, and around the rims of which were stuck Christmas candles of all colours. There were holly and mistletoe on the walls, and on the mantelpiece, and over the door, and in the passages, and hanging everywhere from the ceiling, so that there were plenty of opportunities. How many kisses were given it would be impossible to say, for nobody stood on ceremony, and least of all Bluebell, who was fond of being kissed. So the night passed merrily until it was time for Sassafras to leave, and "good-bye" had not been said. Coltsfoot saw that Sassafras could not say the word before strangers.

"Let us walk together down the lane," he said. "Come, Bluebell, take Myrtle's hand; come along, Robin; we four will be enough."

He whispered to Sassafras that he would tell the mother and father. They walked down the lane, and at the foot of it Sassafras bade good-bye—to Ragged Robin first, who, when he understood that he was about to lose his friend, fairly blubbered, and ran off to hide his grief.

"Going away!" exclaimed Bluebell. "Where to?"

It was a difficult matter to make the little maid understand why it was imperative that Sassafras should go away to foreign countries; she thought one country was enough to live in, she said. But the word had to be spoken, despite her ignorance of necessary things.

"I will never forget you, Bluebell," said Sassafras, "and I want you to think a little of me when I am away, and to love me a little."

"I'll love you always—always," said the little maid, her tears flowing freely, for these young tender hearts are easily touched, and suffer more than we are aware, "and I'll think of you day and night."

"Here is a little present for you that I want you to wear, so that you can't forget me if you try to."

"He produced a very thin and slender gold chain, of trifling value, at the end of which a small gold heart was attached. He placed the chain round her neck, and kissed her; the picture of her pretty child's face raised to his, with the tears swimming in her eyes, and her soft red lips asking for another kiss, recurred to him many and many a time during the years of his travels, and he loved to linger on the memory. The stars were glittering above and around them, and in his memory he never saw Bluebell's face with the daylight shining on it, but always in a framework of stars on such a soft, clear, tender night as this was.

"And now, dear lad," said Coltsfoot, with a strong firm grasp of the Prince's hand, "good-bye, and God bless you!"

"Good-bye," sobbed Sassafras; "I never shall forget what you have shown me this day."