a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Emu's Head Author: Carlton Dawe * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1900191h.html Language: English Date first posted: February 2019 Most recent update: February 2019 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Prologue 1.

Prologue 2.

Chapter 1. - At The Sign Op The “Emu’s Head”

Chapter 2. - A Daughter Of The Tap-Room

Chapter 3. - A Fatal Moment

Chapter 4. - The Arrival Of Cousin Edith

Chapter 5. - A New Experience

Chapter 6. - Introspection

Chapter 7. - I Love You

Chapter 8. - The Robbery

Chapter 9. - The Result

Chapter 10. - Mr. Logan’s Solicitude

Chapter 11. - Delilah

Chapter 12. - Husband And Wife

Chapter 13. - Gone!

Chapter 14. - The Redemption Of Kitty

Chapter 15. - Delilah Pays

Chapter 16. - The Cipher

Chapter 17. - Morgan’s Last Jaunt

Chapter 18. - Hall’s Plant

Chapter 19. - Into The Great Beyond

Chapter 20. - Which Concludes The Chronicle

It was a wild night in mid-July. The wind howled through the great streets with indescribable fury, driving the drenching rain with unexampled force into the faces of all belated wanderers. The gas-lamps flared dismally in the cheerless scene; no passing cab nor vehicle of any description enlivened the monotony of the patter-patter of the great drops, or the hoarse screamings of the wind; all windows were securely fastened, and blinds snugly drawn, so that if any light pervaded a chamber no ray of it could escape out into the awful night. Scarcely a human being was to be seen. Even the midnight prowlers had sought protection from the cruel storm, owning the presence of a fiend more pitiless than themselves. The city of Melbourne was given up to darkness and the tempest.

As George Vincent, hurrying from the neighbourhood of the Carlton Gardens, entered Stephen Street, or, as it is now called, Exhibition Street, and beheld the long stretch of dim gas-lamps before him he thought he had never gazed upon a more melancholy scene, and, with something like a feeling of awe, plunged into it. He felt like one of those heroes of fairy lore who make strange journeys into wild and fearful lands; for is there not something awe inspiring in a silent, sleeping city? Like a brave knight, however, he charged the dreadful passage, and a determined struggle ensued between him and the angry elements. Great Boreas! how the night roared, how the rain hissed as it pelted down upon him! Whew! Was ever such a night for gods or men? His umbrella was blown to pieces in a twinkling, and it seemed as though a hundred fiends were trying to drag the great-coat from his back. But, failing in their endeavours, they, being mischievous imps, blew it up ’round his legs, so that before he had gone many yards he was wet through to the knees. This not being in accordance with his idea of the fitness of things, he looked about him for a temporary shelter. Just here Little Lonsdale Street crosses Stephen Street and continues its narrow way westward, so that when he emerged upon the former thoroughfare he took half-a-dozen quick paces up it and thus gained a moment’s respite from the drenching storm.

As he stood listening to the furious wind which went screaming by, and watching the great drops pelt down upon an adjacent lamp, he was suddenly startled from his reverie by hearing a noise which certainly seemed more of the earth than heaven. Knowing, however, the reputation of the quarter thereabouts, he doubted not but that it was merely another drunken brawl—a thing which concerned him not; and so once more he began to contemplate his friend the lamp, wondering how long the great drops would take to beat in its quivering panes.

“Help—help!”

There was no mistaking the sound this time. It came down the dim thoroughfare on a great burst of wind, shrieking as it passed away into the night. In a moment the young man had quitted his shelter and was bounding up the street, towards the spot whence the voice had issued. About fifty yards up he struck a narrow lane on his right, a black, grim-looking passage in which a solitary lamp flared dismally, thus accentuating the surrounding darkness. Here he stood still a moment, straining his eyes and ears.

“Help—police!”

There was no doubt of it now. In the feeble glare of the light, full thirty yards up the lane, he distinguished the outlines of several figures, and, guessing that murder was at work, he bounded forward with the cry of “Police!” Those dim figures were immediately seen to stand upright, then turn about, and, like the evil spirits that they were, disappear into the darkness.

George Vincent looked about him in amazement, and had he been living in any but this most enlightened age he would, undoubtedly, have believed himself the sport of some strange hallucination, for, as far as he could see, there was no trace of the beings whom he had most certainly seen. Then there was the cry, too. Surely no immortal had ever shrieked for the police: one never couples the two. And yet he had distinctly heard that cry. He peered intently into the darkness, for like all such places the lane was badly lighted—it needs all our gas to keep good the respectable—but he could see nothing. There was an offensive odour about the place, however, which did not escape him, and this, coupled with the dangerous reputation of the locality, impressed him with the advisability of retiring while he possessed a sound skin. And this admirable thought he was about to put into execution when he heard a groan issue from the darkness to the left of him. In a few strides he had reached the spot, and, stooping low, discovered a man stretched out on his back. His first thought was to shout loudly for help, but fearing that he might bring an undesirable crowd about him, he took the man’s hand in his and asked him what was the matter.

“Who are you?” asked the man, starting up with a piteous moan.

“A friend.”

“They’ve murdered me,” groaned the poor wretch in a weak, terrified tone. “Take me down the lane—anywhere—anywhere out of this! They’ll be at me again in a minute.”

Vincent, thinking this an excellent idea, prepared to lift the man in his arms, but the poor fellow’s groans stopped any such charitable intentions.

“No, no,” he sobbed, “no—I couldn’t stand it. Drag me. Send for the police, quick. It was Flash Jim that did it, curse him. But,” added the man with a ghastly sort of chuckle, “he didn’t get it, he didn’t get it.”

This exertion brought on a severe fit of coughing, which almost precipitated him upon that journey from which no traveller returns; but after he had successfully repulsed the attempt to hurry him into eternity, Vincent seized him beneath the arms and dragged him down the lane towards the street. He, however, had not accomplished more than half the distance before the injured one began to groan so loudly that the Good Samaritan was forced to stop through pity. Propping him up against the wall, the young man interrogated him once more as to his condition.

“I’m clean done for,” gasped the man. “They’ve cooked me this time.”

“Where are you hurt? Let me see what I can do for you.”

“I am hurt all over. You can do nothing.”

“Then let me run for help.”

“No, no—for God’s sake don’t leave me—don’t, or they’d be on me again and get it after all.”

“Very well then. I will stand by you till assistance arrives. The police are sure to be along presently.”

“D—the police,” said the dying man faintly.

“As you please,” said George, smiling in spite of his surroundings. “Yet, if I mistake not, you called for them just now?”

“Yes, yes, of course—but that was only to frighten Jim; because I hate ’em as much as he does. If I hadn’t done that he’d a-murdered me, the dog, and got it as safe as eggs.”

“Got it,” repeated the young man, his interest aroused in this indefinite statement, for “it” must have been of considerable importance to incite men to murder, “got what?”

“Look here, mate, you ain’t a trap?”

“No.”

“Nor a D?”

“No.”

“You’ll swear to it?”

“I will. I am merely a private citizen. I was on my way home, but, stepping up the street to escape the rain, I heard your cry—and here I am.”

“You are too late, mate.”

“Don’t say that. You may not be as badly injured as you imagine. If I could only get you out of this—”

“No, no—don’t leave me,” exclaimed the man piteously. “Don’t, if you’re a Christian. Jim’s a devil, he is, and would be on me in a second; but the cur won’t come with you here. Curse the rain,” he went on, shaking his fist at the dark sky, “why don’t it stop? As if it wasn’t bad enough for a man to die, without getting wet to the skin. Look here, mate, I don’t know who you are, but you seem straight enough, and if you’ll stand by me I’ll make your fortune. I couldn’t make my own because I couldn’t read the infernal thing, but it’s there all the same; and old Ben, before he set out on his last job, gave it to me; and Flash Jim knew I had it, but I swore I hadn’t; and to-night, like a fool, I showed it—showed it, after keeping it dark all these years—and that’s why they have done for me, curse them, curse them!”

Vincent listened to this strange talk, fully believing the man was wandering in his mind.

“I wish you would let me get some help,” he said; “or else allow me to move you.”

“No, no,” replied the man, in a low, husky voice, so low, indeed, that the young fellow had to bend over him to catch the words, “I couldn’t stand being moved. They’ve cut me somewhere about the neck, and I should choke if you touched me. But don’t be in a hurry, mate. I shall be gone in a minute, and then you can kick me down the gutter if you like. Tell me, are you rich?”

“I am anything but that.”

“That’s good to begin with,” whispered the dying man huskily. “It’s a fortune, you see, and it’ll be the making of a poor man. ‘Take it, Billy,’ said old Ben, ‘and guard it well. If I go first it’s yours, if you go it’s mine.’ That’s what old Ben said to me, mate, and you see I’ve stuck to it ever since. Just put your hand in my breast pocket, will you?” The young man did as he was bidden and extracted a pocket-book therefrom, which he held before the eyes of the dying man. “Yes, yes, the fortune’s there. But not a word to the traps, mind, not a word to the traps.”

Vincent slipped the book into one of his own pockets, and just at that moment a couple of lanterns flashed in the entrance to the lane.

“Help!” shouted the young man.

“Who is it?” whispered the dying man, “the traps?”

“Yes.”

“Not a word, mind, not a word.”

“What’s the matter here?” asked one of the policemen as the two rushed up.

“Murder.”

“Murder, eh?” They turned their lanterns full on the figure which Vincent had propped against the wall, and he saw a man of about fifty years of age, respectably dressed, though the clothes were now disarranged and dirty, and sodden with rain. It was a well-cut face he saw, and one which might have been handsome before age and dissipation had set their marks on it; but it was livid and ghastly now, and as he watched he saw the haggard eyes look up into the light with a defiant glance. Then the jaw dropped: the man was dead.

One of the constables here ran off for a stretcher, and while he was gone Vincent told the other that which we have already narrated, though he forgot to mention aught concerning the dead man’s pocket-book. The constable then explained that it would be necessary for him to re-state his story in the presence of the inspector, and the young man, nothing loth, accompanied the two officers when they bore away the body.

In the presence of the inspector and the two policemen George Vincent repeated his narrative; told minutely how he stood watching the lamp, how he heard the cry, how he rushed up and saw the figures hurry off; but, strange to relate, he again forgot to mention the dead man’s gift.

Mr. George Vincent, whom we have already had the pleasure of introducing, though under anything but conventional circumstances, was the only son of Mr. Samuel Horatio Vincent, a gentleman who at one time owned a considerable reputation as an architect in the city of Melbourne; but like too many gentlemen who enjoy fair reputations, Mr. Vincent was inclined to presume, and for such presumption he was fated to pay dearly. As a cat may be killed with care—and we believe no one will attempt to dispute this statement—so may a man’s reputation perish by indulgence. Being a person of illimitable ideas, which he ever strove to indulge to the top of their bent, Mr. Vincent soon found that the consequences attached to such large notions were like the notions themselves—infinite. A fine house in South Yarra, in which he entertained royally, horses, carriages, servants,—all these needed money. It was the same old story. Mr. Vincent got the money and the Jews his property. It was rather a come-down for this estimable family, but luckily, before the final catastrophe, the two daughters married fairly well, so that there were only husband and wife, with the boy George, then a lad of seventeen, to provide for. From South Yarra these three migrated to the wilds of Prahran, and though Master George experienced much sorrow in leaving the grammar school for an office, he was yet old enough to know that there was no gainsaying necessity.

Mr. Vincent, however, instead of regarding his fall as the dire calamity his friends insisted upon making it, looked upon it as a positive godsend, one of those blessings which come in the guise of curses, for it relieved him of innumerable embarrassments, and allowed him to dabble in matters more congenial to his tastes. As he had lost through speculation, while neglecting his own trade, to speculation he turned, resolved to win back fame and fortune or—or go bankrupt again if he could get the chance. Consequently he promoted banks, building societies, mining companies, irrigation schemes—in fact, there was no company of any importance in which Mr. Samuel Horatio Vincent had not his little finger. People quite believed that he was well on the way to fortune once more—for there is no way of making a fortune equal to that of handling other people’s money—but before that belief was wholly realised, Mr. Samuel Horatio Vincent gave up the ghost. Indeed, when they came to reckon up his personalty, his sole fortune consisted of one hundred and seventy-five pounds. Nevertheless, the good man had built up a considerable reputation, and if his premature demise did not quite paralyse the money market, it was known to affect several tradesmen in the neighbourhood of Prahran.

George was in his twenty-third year when his father died, and when we meet him, five years after, he was still in the same dingy office, slaving away for a stipend of three pounds a week, which, as far as he could see, was likely to remain at that figure for some time to come; for his master, Mr. Bash, was one of those good people who always think more of the spiritual than the material welfare of a man. Perhaps he might one day rise to three pounds ten; perhaps again he might recede. When man depends for subsistence on the caprices of his fellow man, he must live in constant terror of the worst. Whenever he approached Mr. Bash on the subject of a rise, that good man seized the opportunity of delivering a homily on the follies of youth and the evil of luxurious living, and when the young man somewhat flippantly replied that he should like to have the chance of living luxuriously, Mr. Bash answered, with a look of horror, that it would profit him nothing if he gained the whole world, and lost his everlasting soul.

And so he went back to his desk, and wondered if he were doomed to pass the rest of his life in this deadly dull routine. Was he for ever to be shut in by four walls, taking stock and casting up accounts? Never! And he chewed his pen till his teeth ached. But the grim walls still surrounded him, and the ponderous ledgers grinned at him as they sat on their dingy shelves. “Ha, ha,” they seemed to say, “you belong to us, you belong to us. You may fret and you may fume, but escape us you never shall.” Intolerable! Better be a counter-jumper at once. One may have to measure calico all one’s life, truly, but it must be a pleasure to measure calico for some people. And when your customer is young and chatty, and she turns up those pretty eyes of hers and asks you how much a yard, do you not feel your fingers tremble so that you cut her off a good three inches too much? Believe me, my brothers, there is something extremely fascinating in the life of a counter-jumper. At least, so George Vincent thought. To him there was something fascinating in everything but clerkship, for such a business gives a man no chance. A counter-jumper may save up till he purchases a little shop of his own; then see how handy a wife comes in. But what use can the poor clerk make of his better half? Not that George contemplated matrimony—oh, dear no! Though once he had crossed Brander’s Ferry with a young girl whose beauty had impressed him not a little. He had thought much of her soft eyes and fair face, more, in fact, than he would admit even to himself; and when, some three weeks after, he met her on the public crossing, he thought she was an old friend and raised his hat, but she, blushing vividly, hurried on with averted face. That was the last George saw of his divinity, and though for a long time after, whenever he thought of matrimony, he used to conjure up those sweet eyes and that fair face, he had now almost forgotten the lady’s existence.

Sometimes he used to think he would not mind grinding away at his desk if there were only something to hope for; but the eternal getting up and going to business, summer and winter, in rain or shine, with no hope of improvement or advancement, nothing to which he might look forward in all the years that were to come—this, this was the thing which angered him beyond endurance. Could any life be worse than that of clerkship? Was it a fit occupation for a full-grown, able-bodied man; a man who had ambition and hopes, and whose hands used to itch for something weightier than a pen? He sighed for the vanished Ballarats and the warlike stockades. He would have welcomed any change, from gold-digging to fighting. And yet he could not see how he was to avoid that fatal pen, those grinning ledgers. He grew peevish, irritable, almost misanthropic; and it is certain he developed a turn for sarcasm and cynicism which was not becoming in one so young. He had no friends, that is no intimates, and though people liked him well enough, they always sneered at his imaginary grievances, which, coming to his knowledge, was never known to sweeten his disposition. And thus he lived, and thus he thought, and in this frame of mind was he when that adventure befell him which opens this chronicle.

As he left the police quarters he made hurriedly for his hotel (having long since tired of boarding houses), pressing his hand every now and again to his pocket to feel if the murdered man’s gift were still there. It is true he was all aglow to know what that pocket-book contained, and yet, as became one who had gained a reputation for cynicism, he slackened his pace at different intervals with an exclamation of annoyance, for in spite of himself his heart and legs would run away with him. It was now about three o’clock in the morning. The rain had ceased falling, and the broken clouds scampered like mad things across the face of a sickly moon. Here and there he beheld a crouching figure slink away in the darkness, and a policeman at the corner bade him a cheery goodnight, but beyond that the city lay as quiet as a dead thing. At the corner of Bourke and Russell Streets he stood for a moment at the coffee-stall to imbibe a cup of that warm, if somewhat thick, liquid, which masquerades as the berry of Mocha, for he was thoroughly wet and cold. He did not imagine, though, that the little man who came up and ordered a similar drink had followed him every step from the police barracks. The coffee finished, Vincent hurried on to his hotel, which he entered by means of a latch-key, closing the door behind him. The little man before mentioned watched this proceeding from the other side of the street, and then, apparently satisfied, returned whence he had come.

Vincent had, in the meantime, clambered to his room, and though absolutely burning to know what the dead man’s book contained, he yet withdrew it leisurely from his pocket and carefully began to undress. This proceeding he almost dawdled over, wet as he was, for he was of a curious temperament and really loved to sting his impatience. But it is in the nature of things that they shall end, so, notwithstanding his obstruction, the feat of undressing was at length accomplished, and, seizing the book, he jumped into bed. Placing his candle on the table beside him, he began to examine the curiosity from the outside. It was a pocket-book without leaves—one of those little flat receptacles which fold over like a book, in which men carry their cards, letters, or bank-notes if they have any. It was rather old and dilapidated, though it had once been of blue satin embroidered with a spray of flowers; but what colour it might now be called, or what flowers the embroidery was supposed to represent, no man might say. It was encircled with a piece of dirty string, and this, with much precision, Mr. Vincent untied. Then he calmly scrutinised the twine till his impatience almost choked him, and he was at length constrained to open the book itself, the inside of which was of frayed red silk, and in one corner bore the two letters W. J.

The first article he extracted was an old newspaper account of the death of Ben Hall, with these words underlined, perhaps by W. J.’s own hand. “Hall’s last exploit will be too fresh in the minds of our readers to need recapitulation, but it is a singular thing that none of his gang should have known what became of the vast treasure he took from the Mount Marong Escort.”

Mr. Vincent pricked up his ears as he read these words, and sitting up in bed began to show a little more interest in the little old pocket-book. Paper after paper he turned out, but they proved of no consequence, being scraps of Ben Hall’s doings, three or four mysteriously worded advertisements which had evidently been inserted in the agony column of some newspaper, a letter from “your pal Jim,” and an old telegram addressed to one Williams, which contained three words, the meaning of which was quite beyond Mr. George Vincent’s comprehension. This was all. It must be confessed, a feeling of the most acute disappointment took hold of him. He uttered something very like an oath and crushed the little book in his hand, preparatory to hurling it into the grate. As he did so, however, he thought he felt some paper crumble beneath his hands, and carefully straightening out the little article again, he found this thought to be perfectly correct. In a moment he had torn the lining asunder, and there, sure enough, was a piece of soiled yellow paper. With something very like a thrill of expectation, though he would not have owned to it, he cautiously unfolded the crumpled curiosity. It was stained with age, dirty with finger-marks, and sadly frayed at the edges; indeed, its whole form bore eloquent testimony to having weathered many a stormy period. Yet it was none of these things which riveted his attention. He saw the following curious arrangement of letters:

This, to be sure, looked a very formidable thing, and for the moment he thought he had stumbled upon some ancient writing; but, quickly catching the first idea, he, with the aid of a pencil and a piece of paper, soon had, as it were, the letters on their feet. Then he read them over, first one way and then the other, full twenty times. He formed words easily enough, and thought he had the answer in his head quite half-a-dozen times; but the words were so disjointed that he could make neither head nor tail of them. Yet he firmly believed that he had stumbled on a cipher which, the key once being found, would enable him to bid a long adieu to goose quills and grinning ledgers. He, moreover, had no doubt that it referred to the plant of Hall’s—perhaps this very Mount Marong Escort—and he understood now the terror and anger of the dying man, who, knowing its value was yet unable to realise it. For years, no doubt, he had carried this scrap of paper about with him, puzzling over its contents, yet afraid to take anyone into his confidence. A fortune in his hands, perhaps, and he knew it. Construct those forty-two letters into the proper words, and he might have the secret which would make him rich for life. Yet he had failed to do so, and that paper which he had guarded with his life had at last been the means of his death; for that it was to secure this writing Flash Jim had murdered him, Vincent doubted not.

As the young fellow lay back on his pillow thinking it all out, he pictured Hall and his gang sticking up the Mount Marong Escort, which he knew had been a rich prize; and then that wily one, who so soon after met a violent end, stealing away and burying the greater part of the treasure against a rainy day. And he thought again of the letters, and the good news they might tell if he could only put them together; and he took up the small piece of paper for the twenty-first time, intending to re-peruse it, when his candle suddenly spluttered and went out. For a long time he lay staring up into the darkness, picturing it with imaginary scenes from the life of the late lamented Mr. Benjamin Hall: and even when he fell asleep, he dreamt all night of letters in cipher and the Mount Marong Escort.

The diggings at Dead Man’s Flat had been in full swing for close on five months, and during that time hundreds upon hundreds of men had come and gone, some departing with their pockets full of the precious metal, others poorer than when they arrived. This is the fate which clings to all such places—nay, is it not the fate of every phase of life? The man in the hole a few feet from you may find a deposit which will make him rich for life, while you work day after day, barely gaining enough to keep the breath in your body. This is the sort of fate which, cur-like, worries poor humanity. The rich man’s horses splash the poor man’s ragged coat; the shop windows gleam none the less temptingly because countless hungry eyes glare in upon them; the rich feed none the less sumptuously because the thousands starve. This, again, is the fate which it seems necessary the children of men should suffer.

There were rich and poor at Dead Man’s Flat, as there are in every community, but there was this difference—the rich man never splashed the poor, never flaunted his riches, which, somehow, made poverty endurable. Indeed, it would have been somewhat difficult to say who were the rich and poor of that busy place, for no one but the men themselves knew their own monetary value. A large felt hat, a pair of big boots (if you could afford them), coarse trousers, and a Crimean shirt, and you had the millionaire or beggar of Dead Man’s Flat—though it would be ten to one the beggar was the sprucer of the two. This, however, as most of us may know from personal experience, is a state of things not confined to any particular locality.

At one time it was thought a new Ballarat or Bendigo had been discovered in this grimly-named place, and men rushed from all parts of the country to participate in the hunt for the yellow metal. Clerks flung aside their pens, barristers their briefs, and even clergymen their prayer-books. The ships in port were deserted by their crews; there they lay upon the waters month after month, with never a soul to man them, in spite of the bribe of high wages. The British squadron lost every man it allowed to step on shore, and numerous stories were told of the blue-jackets letting themselves over the side in the darkness, and, spurning the danger from sharks, strike out for the promised land; even the upright guardians of the law cast aside their helmets and batons for the slouch hat and the pick and shovel. Oh, they were mad days, when every man, woman, and child had the gold fever fierce upon them; when the pick and shovel were the only implements worth owning, and when he who had no wealth but that of health and courage, set out on his long tramp to the El Dorado. They were strange times, too, and men went about with their lives in their hands; for, what with the convict blood and the blackguardism of California, things were not always too carefully regulated in those mixed masses of humanity. Yet they were man-making epochs, too, and to them Australia owes that sturdy self-reliance which is so conspicuous in her sons. Accustomed to a life of adventure, and inured to hardships consequent upon the opening up of a new country, they have none of those effeminate qualms which the more ancient nations so assiduously cultivate. Their fathers roughed it before them, and they too have had their share of toil. They have the man’s strength with the disdain of trivialities; will take the best that comes and hope for better luck in the future. These men will stand firm in a crisis—ay, and fight, too, when their country needs them.

Dead Man’s Flat was now an irregular mass of white canvas tents, dotted here and there with a more substantial hut of bark, while away on the top of the hill, surrounded by a strong fence of saplings, stood a large slab and zinc building, which was used as court-house, police barracks, and hospital. Here the diggers had to come to get their “miner’s right,” or license, before they were allowed to peg out a claim, or, in other words, to work; for without that government certificate a man was liable to have his claim “jumped” at any moment, his hoardings confiscated, and himself fined. At the foot of the hill above-mentioned a great creek pursued its irregular course, supplying the miners with plenty of water for their pans and cradles, and like the roar of thunder afar off was the noise of those rocking cradles when the whole camp was in full swing.

To the right of this creek, and stretching away for many miles in the distance, was the rich plain of Dead Man’s Flat—rich in two ways; first, because of its alluvial deposits, and secondly, on account of its well-grassed and well-shrubbed surface. This second reason, however, was of little moment to the thousands who swarmed the diggings. They cared not how many sheep and cattle it would raise, or how much good corn might bend its graceful head to every breeze. They had come to work for gold, and to the gold-digger there is no colour but yellow. So they clung to the banks of the great creek and hollowed them out for miles, till one looking at them from a distance saw nothing but thousands of little mounds. Yet to thread those little hillocks, even in broad day, was a work of no small danger and difficulty, for every mound represented a hole from six to twelve feet deep, and often more, which any false step might precipitate you into, much to the danger of life and limb. To attempt such an undertaking at night was proportionately serious, though the less honest of this mixed community had many a time blessed the darkness and the danger of the road; and , many an upright man had trudged off to his claim in the morning only to find that it had been worked out during the night, and that whatever gold it might have yielded had gone into the pockets of another. But honesty, unlike justice, is not always blind. It was rarely robbed a second time, being quick to perceive how much more profitable it was to work out the hole before it left it for the night.

This, however, was but one of the lesser trials to which the good were subjected, for the righteous have many grievous burdens to bear in this world of ours. It was not only that a man had first to find the gold, but it was invariably a greater bother to him, once he had found it, than the want of it had hitherto proved; for if it once became known that he had such and such a sum in his possession, the rascals of the community (and you will find them hanging to the skirts of all classes) at once made it their object to relieve him, in one way or another, of his burden. A revolver in his belt by day, a revolver beneath his head at night. In fact it might be said that he ate, slept, and worked with a revolver in one hand.

Now such a life might be termed exceedingly exciting, and it undoubtedly was, but it was an excitement of which a man might easily tire. It was better to get rid of the cursed stuff than live in a perpetual torment, and if the digger were a sociable fellow he would make tracks for the nearest grog shanty, and flaunt his riches like a king. There was nothing mean about the digger of those days either. The gold was easily won and easily spent, and he would treat a bar-full of loafers to the best of wine, and then play skittles with quart bottles of champagne in the place of ninepins. They were indeed flourishing times for the genial Boniface, and many a man who is now rolling in riches has good cause to think kindly of the grog shanty his father kept in the early days. The digger, like the proverbial sailor, was generous to a fault. “Here,” he would say, “a dozen of your best champagne, and take it out of that,” and to the smiling landlord he would toss a bag of gold-dust which would pay for the wine full twenty times. And whenever a theatrical company appeared at that out-of-the way spot, they were sure of a golden welcome, for the diggers would throw bags of gold-dust at their favourite performers in lieu of bouquets. But after all there is nothing strange in this. The system is still adhered to in many theatres, only the gold is now become solid, and people are more polite—they do not heave their gold like diggers, they present it like gentlemen. One night, so the story goes, a company playing at Dead Man’s Flat put up the tragedy of Hamlet but that sombre piece not proving to the taste of the audience, they rebelled when it was half through, stopped the performance, and unanimously demanded a song and dance. And when Hamlet, the Ghost, and Ophelia did a breakdown, the little bags of precious dust flew in a shower upon the stage, proving that all concerned were, or should have been, satisfied.

Oh, yes, there was much fun even on Dead Man’s Flat, for there were some jovial boys among that miscellaneous crowd. True the fun was not always dignified nor the humour superfine, but it made men happy, lightened their irksome burdens, and kept them in touch with the human world. It was a bad thing, that gold-fever, worse than many people imagine, and to free men from it, even for an hour, was an inestimable boon But are we ever free of it, and need we go up the country to Dead Man’s Flat to see it? Methinks any great modern city can show more of this most hideous of diseases in one day than such insignificant places as Dead Man’s Flat can in a lifetime.

The town, proper, of Dead Man’s Flat lay about a mile from the centre of the diggings, though the latter really stretched from the town full five miles down the creek. Some years before the opening of our narrative there had been a Rush in this part of the country, and this township of which we speak was left as a memento of it. It was the usual one-street village with half-a-dozen public-houses, a couple of weatherboard chapels, and sundry other habitations of slabs, zinc, or weather-boards, with here and there an ugly box of German brick. These were all left standing after the first Rush, and when the diggers forsook the place these inelegant edifices fell into general neglect. It was a dull look-out for Dead Man’s Flat in those days, and the inhabitants who had known it for the few weeks in which it had flourished, were never tired of singing the glories of the happy past. It was like the Greeks of the present time reviewing the days of old, or the modern Roman contemplating the fact that his townsmen were once the masters of the world—at least, this is how it would have appeared to the old inhabitants, though to the ordinary observer it may have suggested no such thoughts.

Dead Man’s Flat, however, struggled on in obscurity for many years, till one day a new vitality was infused into its almost lifeless body. A party of fossickers, after vainly seeking fortune among the ruins of the old diggings, which were above the town, went further down the creek and there struck the rich alluvial deposits, the fame of which was soon to bring thousands of eager workers from all parts of the country. Then the light of joy was once more seen in the eyes of the old inhabitants, and in a fortnight the population rose from one hundred and sixty to ten thousand. Coaches and traps rattled into the old town every hour of the day, and those who had been rich enough to ride reported that hundreds more were tramping in their wake. Oh, there was some life in the old place then, the house of mourning was changed to one of revelry. A dozen new buildings went up every day, and though they might not have been as durable or picturesque as a Norman tower, they certainly added to the extent and variety of the city.

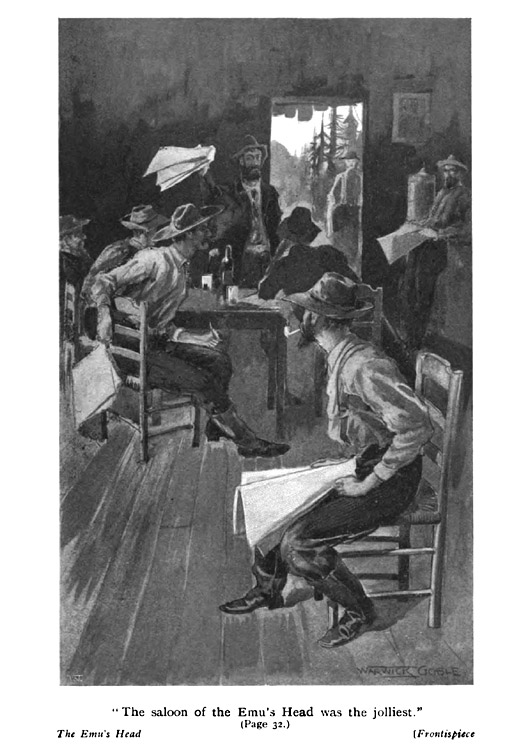

But of all the jolly places in Dead Man’s Flat, the saloon of the Emu’s Head was the jolliest, and to this cheerful rendezvous the diggers trooped of a night to drink, smoke, and yarn, and, if they felt so inclined, gamble away their hard-earned gold. Mr. Peter Logan, the worthy gentleman who ruled this abode of Bacchus, had no objection. He had a nice little room there at the back of the bar, nice and quiet-like, and he would even take a hand himself, if the gentlemen had no objection. At first the gentlemen had none, but when Mr. Logan invariably rose with their little bags of gold bulging out his pockets, they grew suspicious, and at last decided that they would no more admit him to their play, telling him that he was much too clever for them. At this Mr. Logan laughed good-humouredly, confessed they didn’t know much about cards, and then asked them if they had any orders to give. A more fastidious person than the rotund Boniface might have felt and shown annoyance at these covert reflections on his honour, but your good landlord never quarrels with your good patron; besides, Mr. Logan’s patrons would have taken him up, if he had made himself objectionable, and tossed him from the room without a moment’s hesitation.

Mr. Peter Logan, at the time our chronicle opens, was between forty and fifty years of age, fat, red of face, with that hard look about the mouth which comes of a hard life. He was, however, or had been, a man of some presence, and though he may never have been distinctly handsome, he yet bore traces of past good looks. But Mr. Logan, like many more unfortunates, had run to fat. The friends of our boyhood, the sweethearts of our callow days—where and what are they now? He, poor fellow, has developed an enormous waist, and grunts like a hog when he stoops to lace up those confounded boots; while she, poor thing, her delicate profile gone beneath a shapeless growth, pants and fumes as she struggles to encircle with a twenty-two inch stay a good thirty inches of solid flesh, not counting the hips—which have expanded enormously. Such is the fate to which the decently covered youth may look forward. Her arms are plump now, her breast full; she is a picture-girl. But wait till she is married a few years. Yet, no, no! We cannot even bear to contemplate the cold-blooded, heartless ways of that inexorable tyrant—Time.

Mr. Logan had certainly run to fat, though why he should have done so he could not tell you, because, as he would explain, as a boy he was nothing better than a skeleton. This is one of the little weaknesses of all stout people. They are eternally cramming down your throat that, once on a time, they were mere shadows of men and women. I never meet my friend Jones without he complains bitterly of his lot. “And yet,” he wails, “there was a time when I was as thin as a lath, and had an arm like a candle.” Poor old Jones! I never yet called on Mrs. Robinson, who turns the scale at fifteen stone, without hearing her remark, in a casual sort of way, that she wore an eighteen-inch corset on the day of her marriage. Now it is my private opinion that she and Jones were always inclined to obesity, and I likewise believe that Mr. Logan was doomed from birth to carry more than his just portion of flesh, for I never met anyone who ever knew him when he wasn’t “stoutish.” Anyway, as he stands in the far corner of his bar to-night, his shirt-sleeves rolled up to his fat elbows, no collar on his fat neck (Mr. Logan never wore a collar—he hadn’t room for one), and a big cigar stuck in his mouth, which he occasionally withdraws from that sweet receptacle with his left hand, the third finger of which is missing, though the other three are profusely bedecked with jewels, he looks the strangest mixture of man and beast that one could wish to see. How he ever induced that dashing woman over yonder to marry him is a thing none of his patrons can comprehend. But that by the way. At present he is deep in conversation with a somewhat shaggy-looking individual, who every now and again sweeps the saloon with a quick glance from a pair of hard black eyes.

The fun, however, continues with undiminished vigour; songs are sung, jokes cracked, and occasionally some inebriate lurches into the middle of the floor and begins a step-dance, which is invariably wound up by a breakdown of the right sort; for someone, equally drunk, unexpectedly launches into him, and both go sprawling to the floor. Others, the more dashing of the assembly, fellows who tidy themselves up before they come out for the night, who have lady mothers and sisters in different part of the country, or who, perchance, were somebodies away in England, once on a time (for all classes and conditions meet on the Australian gold-fields), these, I say, lounge over the bar, making violent love to the pretty landlady. But she takes their pleasantries good-naturedly, laughs when they laugh; though she brings them sharply up if they attempt undue familiarities. But they all like her, and will put up with anything she says or does, for is she not singularly attractive, and does not the poet tell us that beauty will draw men by a single hair? And she is decidedly pretty, or, rather, handsome. There is not another woman like her in the place, and if you were to question the diggers they would declare to a man that she was the finest woman they had ever set eyes on. And she was the sort of woman for whom such men might be expected to possess unbounded admiration. Tall and strong; a figure as firm and upright as an athlete’s; yet splendidly symmetrical—a woman all over. A clear fresh face, dark but wonderfully sweet; a full mouth, capable of the sweetest and most contemptuous of expressions; two great brown burning eyes. Such was Mrs. Catherine Logan, or, as she was familiarly termed (behind her back), “Kitty of the Emu’s Head”—for such was the title of a ballad which some poetic digger had penned in her honour.

How such a woman had ever condescended to link her life with Mr. Peter Logan was, as we have said, the greatest puzzle to her numerous admirers; and more than one drunken man had put the question to her, only to be snapped at for his pains, and laughed at by his companions. Logan was not a half-bad sort of fellow, everybody admitted that, and if he was fat and coarse-looking, that was merely a misfortune which might befall any man; yet there was something indescribable about him which made the match seem ludicrous, and no one could look at husband and wife without wondering how the two ever came together. Woman’s perversity, they supposed. No one yet had ever been able to account for the ways of the sex; and they could no more understand this union than the ordinary person can understand why the delicately-nurtured young lady should be depraved enough to elope with her groom.

The dandies of the diggings swarm about her to-night as usual; they open the bottles for her, and beg to be allowed to come behind the bar and wash up the glasses, but to all these entreaties she turns a deaf ear, nor does she seem to know that they are paying her the most extravagant compliments. She seems pre-occupied, ill at ease, and every moment she can spare from her duties her eyes flash towards the door. She evidently expects someone, and presently that expectation is gratified. The door swings back and a young man enters the saloon. The woman’s eyes emit a glad light, and her hand trembles so that the neck of the bottle rings on the rim of the tumbler.

The young man, in the meantime, after passing a word or two here and there with some acquaintances, makes his way towards the bar and smilingly acknowledges the handsome landlady’s salutation.

“So you have come?” she said. “I thought we were never going to see any more of you.”

“Why,” he laughed, “it is only four days since I was here last.”

“Four days,” she repeated reproachfully, turning the full strength of her wonderful eyes upon him.

“You see,” he went on a little confusedly, “after a hard day’s work a fellow naturally requires a little rest, and I do work down on the Flat there, and no mistake.”

“If you cared to come,” she replied, “you would not make these excuses.”

He laughed a little oddly. “Of course I care. Why shouldn’t I?”

“Why should you?” There was a suddenness about this question which made it almost embarrassing.

“To see you,” he answered boldly.

She looked at him with a peculiar, earnest expression; a quick, piercing look, as though she would read every page of his heart.

“George,” she said sadly, yet half-savagely too, “you should never trifle with a woman,”

“I am not trifling,” he replied. “If I did not come to see you, pray tell me what was the attraction?”

“How should I know?”

“You do not suppose it was Logan?” he laughed.

“No, Mr. Vincent, I do not.” She too laughed as she spoke, and turned away with a quivering smile about the corners of her pretty mouth; but as she looked down into his handsome face, those starving eyes of hers devoured his every feature.

Mr. Vincent, for he it was whom we last saw studying the murdered man’s cipher in bed, turned his back upon the bar, lit his pipe and began to look about him. He is three years older now than he was on the night of that memorable storm in Melbourne. He has flung aside the pen for independence and the open air. No longer the slave of a dingy desk, the sport of grinning ledgers, he now roams the country at his own sweet will, and though he finds the life extremely hard at times, he yet resolutely rejects the temptation to take up his perch once more on the top of an office stool. He has determined to see what fate may have in store for him, and though he feels that the pen will inevitably fall into his hand, and that he shall end his days dozing over ledgers, he tries to forget that there is any age but youth, or that the trade of clerkship exists except as a nightmare in his own imagination.

It is a good two years since he cast aside the “inky cloak” to go into the country, for from the night when he first tried to unravel Hall’s cipher his office became worse than a dungeon. It was stifling, unbearable; and one day he jumped from his stool, flung his pen at the shelves of grinning ledgers, put on his hat and walked out. Since then he had endured much, seen much, and if his heart ever upbraided him for his rashness, his determination trampled the softer feeling out. And so when the Rush broke out at Dead Man’s Flat, he shouldered his swag and moved on with the tide; and this is why we find him to-night in the bar of the “Emu’s Head.” His new life, however unsuccessful it may have been from a social or monetary point of view, was a great success physically. His usually pale face was now splendidly bronzed, his eyes and brain were clear, his frame strong. Those fingers which used to itch for something more formidable than a pen, were now broad and hard as leather, and when he took you by the hand in his hearty way, you felt them twine round your own like strips of supple steel.

“George.”

“Well?”

He turned hastily round. The landlady was in her place again.

“You were dreaming?”

“Was I?”

“Yes. What was it about?”

“Why, you, of course.”

“Oh, of course. But I have something to tell you. My cousin Edith is coming up to-morrow.”

“Is she indeed? And who is cousin Edith?”

“Don’t be flippant, George. Cousin Edith is an orphan—the child of my mother’s sister.”

“Oh! Is she pretty?”

“Pretty! That’s all you men think of.”

“How could I think of anything else?” he said, looking up into her face.

She blushed, but answered quietly, “Yes, I should say she would grow very pretty.”

“Is she a baby?” he asked with a comical look of consternation.

“No,” she laughed, “not quite. She was fifteen or sixteen when I last saw her, and that’s nearly five years ago. Dear me, how the time flies. How old I must be getting.”

Mr. Vincent could not ignore such a palpable invitation, so looking her straight in the eyes he said something which made her flush and tremble all over.

“Go along,” she said. “I know you don’t mean a word of it.”

“I swear to you—” he began.

“Hush, George,” she said earnestly, “you should not fill a woman’s heart with words you do not mean.”

“Well then,” he said, trying to laugh it off, for he had seen how seriously the woman had taken his banter, “we’ll say I was only joking. Come now, tell me more of cousin Edith.”

“No. I shall be jealous of her.”

“But am I not your devoted slave? You do not doubt my allegiance to your majesty’s person? Look at Logan, how he scowls at me. I believe he would take me on if he thought he could give me a licking. How do, Pete?” he cried as he caught the landlord’s eye at that moment. “Poor old chap, he looks a bit off colour,” he continued, turning to the wife.

“I think he has been a little upset these last few days.”

“That won’t do,” said the young man, laughing. “He’ll be losing some of his superfluous if he doesn’t watch it. Who’s the friend?”

“I don’t know. Smith he calls him, but whether that’s his real name or not, I know no more than you.”

“It’s a safe one, any way. I don’t think much of his looks.”

“No; he is not a beauty. He came here two days ago and claimed immediate friendship with Pete, At first my husband seemed a little flurried over his arrival, but soon they were chatting away with apparent pleasure and interest. Ever since then they have been as thick as thieves.”

“Pete doesn’t seem to be very particular.”

A look of unutterable disgust curled itself round her pouting lips, but she said nothing. Vincent, thinking he trod upon dangerous ground, got off with no little alacrity.

“Come,” he said abruptly, “tell me some more about cousin Edith.”

“I have nothing to tell you beyond the fact that her mother has just died, that I am her nearest relation, and that she is coming to me.”

“Do you think she will like this sort of life?”

“I should think not. She was brought up very genteelly, I believe. Her father was a civil servant, or something of that sort. Mother used to say that they lived in very good style once.”

“I’m afraid she won’t like this place.”

“Then she must lump it,” said Mrs. Logan flippantly, and bounded away to attend to the wants of a noisy customer.

“Poor child,” thought George, thinking of the cousin Edith, “if she has been brought up like a lady, what a hell to come to.” And turning, he surveyed the crowded saloon with his first feeling of repugnance. After all, he had lost much in quitting the ways of civilised men and women, and though he flirted hard with the handsome landlady, for he admired her greatly both as a woman and a beautiful creature, he yet confessed to himself that she was scarcely a proper guardian for a delicately nurtured girl, nor was the “Emu’s Head” a house into which he would have cared to see anyone enter whom he respected. Still, it was no affair of his, and it was deuced good of Kitty to give the luckless girl a shelter. Besides, the girl might not be so fastidious as he imagined, and might revel in the vulgar pomp and glitter of the place, the admiration of the dandy diggers. She would be married in a month—or gone to the dogs.

Here his further ruminations came to a sudden and ungallant close, for he speedily lost all thought of the girl in listening to a dozen diggers, who, all speaking at once, were discussing the origin of the name Dead Man’s Flat.

“It took its name,” one of the men was saying in a loud, authoritative tone, like one who knows all about it, “from Dead Man’s Creek, the creek what runs through this here diggins.”

George smiled as he listened, for the gentleman who was holding forth with such authority was his mate, Phil Thomas, an honest enough fellow in every respect and an excellent worker, but too fond of company and the social glass ever to be aught but a rolling-stone.

“And how was that?” asked one, evidently a new arrival.

“Well,” said Phil, twisting his pipe from one corner of his mouth to the other, “it happened before the first rush, you see, which was a good twelve year ago, and came about in this way. A party of prospectors discovered the body of a man about half a mile up the creek, and it was while they were a diggin’ of his grave that they turned up a nugget weighing close on two pound. That was the beginning of the first rush, mates, and that’s how the place got to be called Dead Man’s Flat.”

“Nothing of the sort,” exclaimed an old fellow who had just come up in time to hear this speech, “that’s nothing like it, Phil.”

“Well, Tommy,” answered the worthy Phil, “I bow to you, old boy, but I stick to my own story.”

“You’d stick to anything you laid your hands on,” replied the old man sourly “But I’ve lived here off and on for the last fifteen year, and we, at least, called this place Dead Man’s Flat for an entirely different reason.”

“Then let us hear your version, Tommy. It isn’t a matter of much consequence, any way.”

“Then let me tell you,” said the old fellow seating himself, while the crowd about him increased, and even the landlord and his companion drew a little nearer, all eyes and ears, “that it was called Dead Man’s Flat because it was here a party of bushmen strung up Jack Morgan—one of Ben Hall’s early pals. And I’ll tell you how it was, too. Morgan was a desperate, bloodthirsty fellow, and he actually had the ordacity to stick up, single-handed, half-a-dozen bushmen. Now some bushmen is pretty tough in their ways, and one of ’em, instead of obeying Jack’s cry to throw his hands up, drew his revolver; but, before he could shoot, Jack downed him like a dingo. This raised the other fellows’ blood. They rushed at Morgan, and before he had time to say his prayers the rope was round his neck and he was swinging from a branch of the big gum what’s standing by the road to this very day. And that’s why we called the place Dead Man’s Flat,” added the old man emphatically, “for we left Morgan swinging till the crows had done their duty.”

“Well, we won’t quarrel about how it got its name,” said the man Phil. “But were you really one of the bushmen who lynched Jack Morgan?”

“I were,” said Tommy, “and any one of us would have been a match for him—or Ben Hall either,” the old man added defiantly.

“Did Hall’s gang infest these parts?” asked Vincent, interested in spite of himself.

“Ay, that they did,” said old Tommy, “once or twice. Don’t you know that it was only three mile from this very town that they stuck up the Mount Marong Escort?”

“The Mount Marong Escort!” involuntarily exclaimed the young fellow. Then he looked about him with a smile of apology, and wondered if people would understand his exclamation. Of course not; how foolish of him! Yet, when he encountered the eyes of Mr. Peter Logan, who with his companion, Smith, had advanced to within easy earshot of the old man, he saw something so strange in them that he regretted not having kept his tongue between his teeth.

“Yes, the Mount Marong Escort,” repeated the old fellow, “and a tidy haul it was. Over six thousand ounces of gold, gentlemen—twenty-five thousand pound, if it was a penny. That’s the way Ben Hall and his gang did bushranging in those days.” There was a ring of pride in the old fellow’s voice as he spoke, and he surveyed the listening assembly with a look which plainly asked the question, What do you think of that?

“That must have set them up for life, once they got clear away with it?” It was Vincent who spoke, his voice quivering, notwithstanding his seeming indifference.

“That’s just it,” said the old fellow; “did they get away with it? The gang never got anything but a few hundred pounds between them, because when they were broke up, and Ben himself killed, they said that it was believed that he and his lieutenant, Billy Jackson, had planted it somewhere.”

George immediately bethought him of the letters W. J. in the murdered man’s pocket book, and he also recollected that the man had repeated some of “Old Ben’s” words; old Ben, of course, being no other than this same Ben Hall.

“And was this Billy Jackson killed with Hall?”

“No. He, with Flash Jim, Snaky Steve, and one or two others, escaped. They fetched him up, though, near the Queensland border—somewhere on the Darling, What became of Jim Regan, or Flash Jim, as they used to call him, nobody knows but I guess he’s gone under long ago.”

“Then it must have been within the last three years, for three years ago, this winter, Flash Jim and another murdered Billy Jackson in Little Lonsdale Street, Melbourne.”

“How do you know that?” It was Logan who asked the question, suddenly, almost fiercely.

“Because,” said George, turning to answer him, “I—I—knew the fellow who ran to his assistance!”

“Was it you?”

“Well, yes, it was.” All eyes were instantly turned on Vincent, who, it must be confessed, bore himself with no little modesty, considering the greatness which was thus thrust upon him; for to have been mixed up in any way with Hall or his gang was to become, in the eyes of the diggers, a person of consequence.

“But come, mate,” said old Tommy, who did not like the interest centred in anyone but himself, “How did you know it was Billy Jackson?”

“I did not know till this moment. He spoke of Flash Jim; he said Flash Jim had done it. He called himself Billy; he also spoke of ‘Old Ben.’ ”

“That’s him, sure enough,” cried Tommy. “Killed by his own pals.”

“Did he tell you why Flash Jim had murdered him?” It was Logan who spoke.

Vincent glanced up at him, and was startled by the strange look in the man’s face. It was paler than he had ever noticed it before, and there was an eagerness in the eyes which gave to them a singularly inhuman expression. The whole story trembled on the young man’s tongue, but that one sharp glance at the landlord restrained him—he knew not why.

“No,” he replied, “the man died when the police came up.” Logan and his friend Smith exchanged a series of deep meaning looks which did not altogether escape Vincent’s prying eyes, for he was wide awake now, and, fearful lest he had said too much, thought once more of the cipher which had lain so long neglected in the bottom of his trunk.

“Well, that’s a mighty queer story you tell, mate,” said the old man, Tommy, rising and preparing to go, “and I shouldn’t be surprised if Stephen Jones wasn’t the one who helped Jim Regan to do away with Billy; for Snaky Steve, as they used to call him, was notorious for his villainy. I wonder what old Ben would say if he heard the yarn. Fancy a man’s pals turning on him like that; but it’s just what Stephen Jones would have done. Poor old Billy—he was the best of the crowd. It’s a pity he didn’t give you the secret, though. There’s thousands of pounds lying hid somewhere within twenty miles of this place, or I’m a Dutchman.”

“Perhaps Jackson did not know the secret; in fact, he could not have known it, or he would never have left the gold lying idle.”

“That’s so. Ben was a mighty ’cute ’un. Good-night, gentlemen; good-night,” and the old fellow wobbled off.

“Now then, gentlemen,” cried Logan, “time’s up, please.” Then, beckoning Vincent to him, he said, “we’ll have a glass together when they’re gone. Will you join us, Sam?” This to the gentleman who rejoiced in the honest patronymic of Smith. Mr. Smith said he would be delighted, and then the crowd began to file out, the man Phil singing a charming panegyric on the late lamented Mr. Benjamin Hall, the last verse of which ran as follows:

“Now Ben he was as nice a man

As one could wish to see,

And would have graced a silken rope

And dangled handsomely!

But fate ordained the rifle’s roar,

Should prove his parting knell,

And so he robs on earth no more,

But bails them up in h—, h—, h—!

But bails them up in h—!”

George made his way into the private parlour at the back of the bar, and was immediately joined by Mr. Smith, who at once began to ask him sundry commonplace questions in reference to the diggings.

“You’re a stranger, eh?” asked the young fellow.

“Yes,” said the man with a queer smile, “that is, not altogether, though it’s many years since I passed through this district.”

“Before the first rush?”

“Yes. You see, I come from the New South Wales side.”

“This was rather an out-of-the-way place to fetch in those days, wasn’t it?”

“Well it was, rather—but I had to pass through on my way to the Mount Marong Gold-fields.”

“So, you were at Mount Marong?”

“Oh, yes,” replied the man with just a little hesitation.

“When Hall stuck-up the escort?”

“Yes, sir. Some of my hard-earned dust, that I was sending across to the missis in Sydney, was among the swag. Oh, he was a terrible fellow, was Ben Hall.”

“Who’s talking about Ben Hall?” asked Mr. Logan, entering at that moment with a bottle of whiskey and some glasses, “Who’s taking old Ben’s name in vain?” And then, with a broad grin, he sang the last two lines of the exquisite stanza which concluded the preceding chapter; while Mr. Smith, who seemed immensely tickled by the relation of Ben’s doings in the nether world, pronounced the final word with wonderful verve.

“This gentleman was telling me,” said Vincent, when the hilarity had somewhat subsided, “that he was at Mount Marong when Hall stuck-up the escort.”

“No, were you, Sammy?” asked the landlord, a broad smile illumining his fat face, “were you though?”

“I was,” said Mr. Smith, “and what’s more, Peter, I sent my savings by that particular escort.”

“That was a bit of bad luck,” said Logan with a grin, “a bit of awful bad luck. Say when, Mr. Vincent,” he added, pouring out the whiskey.

“Thank you,” said George.

“Lord, man,” laughed the landlord, “that’s not half a tumbler. You wouldn’t have done for Forest Creek, I can tell you.”

“Nor Mount Marong either,” added Mr. Smith.

“Talking about Mount Marong,” exclaimed the landlord, as though the mention of that name had brought back to him a sudden recollection of the place, “that was a queer sort of yarn you told to-night.”

“Very pe-culiar,” added Mr. Smith, dipping his ugly face deep into his tumbler.

“What, you mean that about the murder of Billy Jackson in Little Lonsdale Street?”

“Yes. I suppose it was Jackson?” queried the landlord.

“I guess as much,” replied the young man, “especially after what old Tommy has told us to-night.”

“Tommy’s a gibbering old jackass,” cried Logan impetuously, “and knows no more of Ben Hall than a cuckoo. Why,” he continued in an aggrieved and personal tone as he handed round a box of cigars, “if you’d listen to him he’d make Hall out a regular hero, when in reality he was the most infernal scoundrel that ever took to the bush.”

“He was,” repeated Mr. Smith with a slow shake of his head, “he was a sad blackguard, was Ben.

“ ‘And so he robs on earth no more,

But bails them up in—’ ”

“Hero!” exclaimed the landlord, cutting short this vocal outburst, “he hadn’t the decency of a common pickpocket.”

“One does not expect decency in a bushranger,” said Vincent with a smile.

“Well, perhaps not,” replied Logan in a gentler tone, “but I can’t bear to think that even a bushranger should turn on a pal.”

“Nor me,” said Mr. Smith, “nor me.”

“That’s right enough,” said George; “but in what way did Hall turn on his pals?”

“Did you ever hear how they stuck-up the Mount Marong Escort?” asked the landlord.

“I can’t say that I have. All I know of Hall has been picked up in the most casual manner.”

“Well,” replied the worthy Boniface, “I guess I’m getting on twenty years older than you, and I remember the occurrence as though it was only yesterday.”

“And me,” said Mr. Smith, stealing a swift glance at his companion, “and me.”

“It happened not five miles down the creek,” continued the landlord. “We’ll walk there one Sunday if you like, and I’ll show you the very spot.” George said he would go with pleasure, and Mr. Smith also expressed a desire to make one of the party declaring it would be quite an interesting event. The landlord smiled, and continued. “It was usual for the Escort to leave Mount Marong at the beginning of every month, but previous to the setting out of this one, the turn-over at the diggings had been enormous, and this, it is believed, came to Hall’s knowledge. So he got his gang together, and when the Escort came up they blazed away at it like a set of devils. Five troopers were killed outright, and three more dangerously wounded; two of Hall’s fellows dropped with bullets in them, and even old Ben himself had a bit of his cheek shot away.”

“No, his ear, Peter,” contradicted Mr. Smith.

“Yes, Sammy, I believe you’re right, though it’s so long ago since I read of the affair that I’ve almost forgotten it. But all the same, might I enquire who’s telling this story, you or me?”

“You, Peter.”

“Oh, I thought you were,” said Mr. Logan sarcastically. “Well,” he continued, “the bushrangers got the gold, over six thousand ounces, and how much do you think that thief Hall gave to the gang?”

“I couldn’t say.”

“Of course not,” exclaimed Mr. Smith hurriedly, “nor you neither, Peter.”

“I can’t say for certain,” replied Mr. Logan, with a slight embarrassment, which he endeavoured to hide by pulling furiously at his cigar, “but I know what I read, Sammy.”

“Of course,” said Mr. Smith, “you naturally would. Here’s to you, old pal,” and he drank a health to the genial Peter. But the look which passed between them did not altogether escape Mr. Vincent. He had suddenly grown extremely suspicious of these two men, and watched them closely. Interest in everything that concerned the outlaw, Hall, once more revived, and he was anxious to again peruse the cipher he had despised so long. Moreover, he had not forgotten the strange look in Logan’s face that night, when he told of the murder in Melbourne; besides which, he remembered the story Kitty had related of her husband’s strange behaviour on the occasion of Smith’s first appearance at the “Emu’s Head.” These things he ran rapidly over in his mind, thinking less favourably of Logan and his friend as he did so. Who they were he had not the remotest idea, but that they were what they would seem to be, he doubted.

“You were speaking of the division Hall made of the booty,” said Vincent, ejecting huge clouds of smoke from his mouth, which, like a veil, partially screened his somewhat anxious face.

“Was I?” asked the landlord, trying to look unconscious of any such intention.

“Of course you was, Peter,” said Mr. Smith.

“Oh, of course,” replied Logan, smiling affably. “I remember reading a full account of it at the time. They said he only gave the members of his gang a hundred quid a piece. Is that what you would call honour among thieves?”

“No, Peter, it is not,” said Mr. Smith, shaking his head sadly.

“Do you mean to say he kept the rest?” asked Vincent.

“Every blessed farthing.”

“But it was a wonder his gang allowed him.”

“They were afraid of him.”

“And what is he supposed to have done with all that gold?”

“Hid it—planted it,” exclaimed the landlord fiercely, “that’s what he done with it.”

It was strange how the worthy host came out with his vulgarisms when excited.

“But he could not very well hide such a quantity of gold without some sort of aid? May he not have taken it away with him?”

“Not he—because he was shot soon after, over the border there,” and he waved his hand towards the New South Wales side.

“Did you ever hear what became of the rest of his gang?”

“No,” said the landlord, a little nervously, “no, I can’t say that I did. But I suppose that was Billy Jackson you saw that night in Melbourne.”

“No doubt. He said a certain Flash Jim had done it. Who was this Flash Jim?”

Logan was too busy pulling at his cigar to reply, but Mr. Smith answered for him.

“Flash Jim was the gentleman of the gang. He wasn’t much of a fighting man, and didn’t particularly care for the smell of powder, or the sight of a trooper, but they say he used to do all Ben’s spying; go into the towns and do the gentleman, you know; pick up all the information he could, and keep the gang well posted with the movements of the police.”

“I suppose he was brave enough to attack an unarmed man?”

Smith laughed curiously, and Logan took a long pull at his tumbler.

“I daresay he would have preferred a mate even then,” said Smith with a cheerful chuckle.

“He had one the night he murdered Jackson, for I saw two men.”

“Did you?” Messrs. Logan and Smith put the question at the same moment.

“Would you know ’em again?” asked the landord,

“Bless you, no. I only saw their figures in the distance—caught a glimpse of them as they dashed away under a lamp.”

“It was a pity you didn’t see their faces.”

“It was,” repeated Mr. Smith. “Such rascals deserve no mercy.”

“They’ll chum with Jack Ketch before long, never fear.”

Mr. Smith shook his head as though thoroughly convinced that sooner or later they would come to a violent end.

“But this man,” said the landlord, returning to the subject of the murder, “didn’t he say anything before he died?”

“Oh, yes, he said a great deal.”

“Ah!”

They both leant forward eagerly.

“A great deal about this Flash Jim—whom he stigmatised as a coward of the first water.”

“Did he now?” laughed Mr. Smith.

Logan took another drink, seeming moody and pre-occupied.

“Is that all he did?” he asked somewhat sullenly.

“Well, he did talk some rubbish about a fortune, which went in at one ear and out the other. He died as the police came up.”

“Now, if he had only told you how to find that fortune?” suggested Logan with an insinuating smile.

“If he had,” replied the young man, “I should not be here now. Besides, if it really was Hall’s lieutenant, is it likely he would have let a fortune lie idle?”

“But he couldn’t have known where it was.”

“Then how could he have told me?”

“Of course,” said Mr. Smith, looking hard at the landlord, “it stands to reason that if Billy Jackson had known where Ben’s plant was, he would have unearthed it long ago; and if he didn’t know, how could he possibly tell this gentleman?”

“It’s my opinion,” continued Mr. Smith impressively, “that Hall never had no plant; or if he had his own friends must have collared it years ago.” And having thus delivered himself, he solemnly struck a match and proceeded to re-light his cigar.

“That’s my own opinion, Sammy,” said the landlord.

“And mine,” echoed Vincent.

“What’s that?” asked Kitty, entering at that moment with the books and the money.

“Nothing that you would understand, old girl,” said Logan with a smile.

“If it’s within range of your intellect, it’s not beyond the reach of mine,” she replied,

“Bray-vo!” said Mr. Smith. “You’ve got your match there, Peter.”

“She doesn’t mean it,” replied Logan. “You’ve got to let them talk a bit, you know, to make up for their other deficiencies.”

“Deficiencies,” echoed his wife, “I’d like to know where you’d be if I didn’t look after you?”

“In quod,” suggested Smith with a chuckle,

Logan laughed.

“Perhaps,” he said. “Anyway, Kit,” he continued, “you’re the Queen of Dead Man’s Flat, ain’t you? and you know I worship the very ground you tread on?”

“You’re drunk,” she cried disdainfully, the blood rushing to her face.

“Not drunk, Kit,” he laughed, “but hoping to be, my girl, hoping to be,” and lifting his glass he drained it with a gesture of bravado.

Mr. Smith chuckled and likewise took a lengthened dip into his tumbler,

“I think I shall be toddling,” said Vincent, rising. He had no wish to participate in the family brawl. He felt extremely sorry for her, for he knew the man’s coarseness was a constant shock to her more sensitive nature. And yet it was what she might have expected from such a union, though how it ever came about was none the less a puzzle to him.

“What, so soon?” asked the landlord.

“Well, you know, I have a good mile to tramp.”

“Of course. I had quite forgotten that. Why don’t you come into the town to live? Why not put up here with us?”

“Too far from work, Pete. Good-night.”

“Good-night. Oh, Kitty, would you mind seeing Mr. Vincent to the door?”

She nodded acquiescence to the suggestion.

“Pray don’t let me trouble you, Mrs. Logan,” began the young fellow.

“It’s no trouble,” she said, looking straight into his eyes. Then, without another word, they quitted the room together.

As soon as the door had closed upon them, Messrs. Logan and Smith stared significantly at each other for the space of twelve seconds. Then Mr. Smith broke the silence.

“It’s him,” he whispered, emphasising the objective case.

“Sure enough,” answered Logan, in the tone of a stage conspirator.

“I wonder if old Billy gave him the paper?”

“Devil a doubt.”

“But he can’t have read it, Peter?”

“I think not. He’s pretty green.”

“Perhaps not so green as we imagine; perhaps old Billy said a sight more than he would have us believe. Anyway, he can’t suspect that—”

“No. But I’ll tell you what, mate,” a low, hard look came into Logan’s fat face as he spoke, “we must get that paper.

“We must,” repeated Mr. Smith, putting his shaggy brows together and peering from under them with his glittering eyes. “And that young fellow’s got it.”

“We must be friends with him, Sammy.”

“Yes. Now, if we could only get the missis—” suggested Mr. Smith with a knowing leer.

“You think he’s gone there, eh?”

“You hit it first pop. But she’s a pretty hard girl to drive, isn’t she?”

“A devil, mate, a she-cat, that’s what she is. Get her back up and she wouldn’t stop at putting a bullet through you.”

“Well, we must wait. It’s not the first time we have had to do it. A fortune like this is worth both waiting and working for. Twenty thousand pound if it’s a penny.”

“Yes, Sammy,” said Mr. Logan, in a thoughtful sort of way, “twenty thousand pound. Ten thousand each, and America. What do you think of it, old pal?”

“It makes my mouth water. But the missis?”

“Wait,” said Mr. Logan impressively. A look of confidence wreathed Mr. Smith’s face into an ugly smile. Then the two worthies pledged each other in silence.

* * * * * * * * *

In the meantime George and Kitty were wending their way through the dark passage which led to the front door, he stumbling, she speaking no word; though he could tell by the short gasps which ever and anon rose from her throat that she was strangely excited. On he stumbled, however, and in stretching forth his hands to grope his way, his right hand accidentally encountered hers.

“I had better lead the way,” she said, and her hand tightened in his. It was a firm hand, strong and yet well-covered, and as her palm pressed his he felt it burn.

“You seem a bit upset,” he said. “You are not yourself to-night.”

“Do you think so?” She laughed a low, hysterical little laugh.

“I do. What’s the matter?”

“What right have you to ask?” she said almost fiercely. “What do you care?”

“Of course I care. Aren’t we old friends?”

“Friends!” she laughed disdainfully “Yes, I suppose so.”

“Kitty,” he whispered, so low that it seemed like a soft sigh.

She stopped and took his hand in both of hers.

“Well?” she said.

He could not see her face, but he knew by the intense whisper, the hard way her breath came, the pressure on his hand, that she was more than a friend to him then. The next moment he had taken her in his arms and was kissing her passionately. “Oh, George, George,” she murmured reproachfully. And yet that was the happiest moment of her life, and as she nestled for that brief space on his breast she felt as though the heavens had opened to her.

But he, misunderstanding that tone, withdrew his arms from about her and stepped back.

“You are right,” he said, in a low, hurried voice. “I am an infernal scoundrel. Forgive me, won’t you?”