a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Ranch on the Beaver Author: Andy Adams * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1900121h.html Language: English Date first posted: January 2019 Most recent update: January 2019 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Drawn by Edward Borein

Chapter 1. - The Ranch on the Beaver

Chapter 2. - The Unexpected

Chapter 3. - The Big Drift

Chapter 4. - The Spring Round-up

Chapter 5. - The Home Round-up

Chapter 6. - Between the Millstones

Chapter 7. - The Mill Runs On

Chapter 8. - Keeping the Powder Dry

Chapter 9. - Frontier Days

Chapter 10. - The Hundredth Sheep

Chapter 11. - Seedtime and Harvest

Chapter 12. - My Kingdom for a Horse

Chapter 13. - The Sower

Chapter 14. - The Old Campground

Chapter 15. - Guests

Chapter 16. - The Value Of Friendship

Chapter 17. - Free Grass

Chapter 18. - The Spring Campaign

Chapter 19. - Hunting The Mustang

Chapter 20. - Bread Upon The Waters

Chapter 21. - The Iron Trail

Chapter 22. - The Acorn And The Oak

Caught him by the horns the first throw

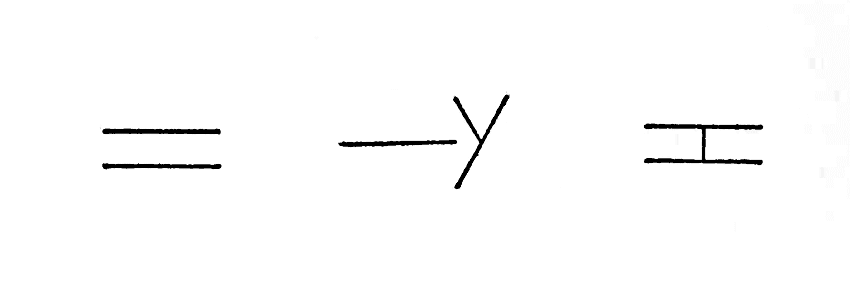

Cut a Two Bar Beef, an animal which had fallen to the brothers when a yearling

All the old tricks came into play

The Lazy H

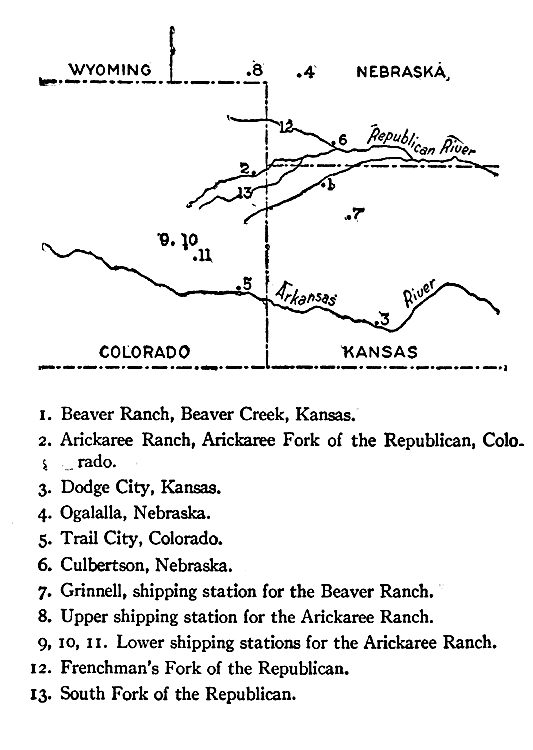

Among the sand-dunes in Northwest Kansas several rivulets unite and form Beaver Creek. The Creek threads its way through dips in the plain, meanders down meadow and valley, and is finally lost in confluence with the Republican River. The farthest western settlement on the Beaver was the ranch of Wells Brothers.

The only landmark in the country was the Texas and Montana cattle trail. This trace passed some six miles to the eastward of the original homestead of John Wells, a Union soldier, who had preempted it some years before. Exiled on account of health, after a short residence on the Beaver his death followed, leaving two healthy, rugged sons, Joel and Dell Wells.

At the beginning of this chronicle, in the fall of 1887, Joel, the elder of the boys, had reached the age of eighteen, while Dell was some two years younger. The most marked feature of the latter was a shock of red hair; he was slender in figure, talkative and boastful, and without a thought or care for the future. The older lad was the reverse of his brother; quiet, cautious, spare in his words, sure in his every move and action, which marked him apart from a youth of his years. The concerns of life, a sickly father, a thoughtless brother, the struggle for mere existence on a homestead, without neighbors, had aged the boy almost into manhood. Otherwise, auburn-haired, with a frank countenance, the elder one showed all the family marks of his younger brother.

An incident changed the lives of the boys. Two summers before, when on the point of abandoning the little homestead, a man, Quince Forrest by name, from the cattle trail, reached their home, accidentally wounded from a pistol shot. The sod shack of the settler was transformed into a hospital, and the lads lent every aid in caring for the wounded man. Forrest, himself a Texan, had a wide acquaintance amongst the drovers, had been a trail boss himself, and knew the ins and outs of the cattle trace. Confined to the homestead for some two months, he levied on the passing herds, summoned every foreman to his cot in a tent, and established a friendship between the trail men and his benefactors.

The pleadings of the wounded man readily secured for the boys the nucleus of a herd. The long march from Texas had rendered many of the cattle footsore; there were strays in every herd, all of which contributed to stock the new ranch. Every trail foreman, under the pretext of founding a hospital, left his strays and cripples on the Beaver. At the end of that year’s drive of cattle into the Northwest, the brothers had secured a snug little herd of fully five hundred head.

The boys, in their new occupation, took root from a vigorous winter that followed. With the coming of spring, anxiously they looked forward to the arrival of the Texas herds, en route north. The latter were delayed by drouth, but finally came like an army with banners. Among one of the early herds to arrive was a young man stricken with malaria, who found a haven at the little ranch on the Beaver.

Jack Sargent proved himself a worthy successor to Quince Forrest. A drouthy year, the trail drovers dropped on the Beaver range an unusual flotsam of stricken and stray cattle. After his recovery, Sargent remained with the brothers, acting as their foreman. Born to the occupation of cattle, a Texan, his services soon became invaluable. There was no detail of a ranch in which he was not a capable man.

The drouthy summer doubled the holdings of the brothers and they made new acquaintances, among whom was the drover, Don Lovell, employer of Forrest. The old cowman proved his friendship that fall by inviting Joel Wells to come to Dodge City, a trail market to the south, where the boy bought a small herd of cattle on credit. The terms called for a factor in the sale of the cattle when matured into beef, with a trusty man, an employee of the seller, who remained with the cattle until they were consigned to a commission firm, the agent in the sale, at an established market.

This mutual agreement added another man to the ranch, Joe Manly, from the Pease River, in Texas, where the cattle were bred. Manly was a languid, lazy Texan, true to his employer, and never seen to good advantage except on horseback. This, however, was peculiar to the Texans, a pastoral people, who were masters in the occupation of ranching. Thus manned and mounted, the brothers met the second winter, which proved to be a mild one.

The occupation of the boys, maturing beef, was in a class by itself. Texas bred the cattle, but the climate interfered with their maturity into marketable range beeves. It required the rigors of a Northern winter to mature a Texas steer into the pink of condition for the butcher’s block. Two winters in the North were better than one. Hence the cattle trail into the upper country, where maturity brought its certain reward. If above three years of age, a single winter might mature them; if younger, two winters; ‘double-wintered’ was the rule. Nature provided a day of maturity, usually the fall after reaching four years old, when the range finished every hoof prime for market. Therefore two-year-olds were preferred in stocking Northern ranges, where the severity of the climate rounded them into beeves.

Restocking their ranch became a question with the brothers. Kansas, in fear of fever, had quarantined against Texas cattle. A new trail, through Colorado, afforded the needful outlet to the North. The boys had contracted, on the same terms, from Manly’s employer, a Mr. Stoddard, at Ogalalla, Nebraska, for a second herd, which was then under herd on the Republican River and within a few days’ drive of the Beaver. After the shipping season was over, their financial standing enabled the brothers to buy still another herd, at Trail City, in Colorado, on the new trail. This contingent was held in voluntary quarantine by the new owners, in fear of fever among their own wintered herd, until after the first frost, when restrictions were lifted and both herds trailed in to the home range on the Beaver. All told, the ranch faced its third winter with a holding of nearly eight thousand cattle.

It was no easy task. The original range, claimed three summers before, had been extended down the Beaver fully five miles below the old trail crossing. The water controlled the herd; range north or south of the creek was a matter of no concern, the cattle ranging out as far as five miles in the summer and not to exceed ten in the winter.

The pride of the ranch was its equipment of horses. The remuda — a word adopted from the Spanish, meaning the relay mounts — now numbered over a hundred head. The buying of through horses, unacclimated ones, a year in advance of their needs, had proved its wisdom during the beef-shipping season just passed. During that brief period, tense as an army on the march, the rule was frequently four changes of mounts daily. A half-mounted man was useless, and a strong remuda was a first requisite on a beef ranch.

‘This ranch has horse-sense,’ said the solicitor for the commission house, on his second visit. ‘That’s a big point in your favor. You’re mounted until the day, the month, and the end of the year. In ranching, horses are to the cattle industry what marine insurance is to ships putting out to sea. Your horses are your only guarantee.’

The rapid expansion of the Wells Ranch kept a number of horses constantly under saddle. During the idle months, even when working a small outfit, a daily change of mounts was necessary. Only in winter work were a few horses corn-fed, while the remainder, subsisting the year around on grass, were used only during the rush of summer months, and by men who knew the limits of endurance of a range horse. ‘Never tire a grass horse’ was a slogan of the range.

In meeting the requirements of the coming winter, two new line-camps were established, one on the lower end of the range, and the other, an emergency camp, south on the Prairie Dog. They were rough shelters for man and horse, and were known as the ‘Dog House’ and ‘Trail Camp.’ An extra amount of forage had been provided at headquarters, the other camps liberally supplied, and before winter set in, a car of corn would be divided among the various camps.

Necessarily, the new shelters were located during the haying season. Joel and Manly selected the sites, placing Trail Camp on the Beaver, six miles below the old Texas and Montana trail crossing, it being simply a matter of shelter and convenience to meadows. Dug-outs were the order for men and horses, and a creek bluff, facing the sun by day, with running water, met every requirement. In locating the camp on the Prairie Dog, a careful study of the topography of the country governed the site. The latter outpost was intended only as a relay or emergency shelter, in case of a winter drift, and was not meant for regular occupancy. It might be called on to bunk half a dozen men and the stabling to shelter double that number of horses.

The site was important. ‘Allowing the bulk of the cattle to range above headquarters,’ said Manly, summing up the situation, ‘your emergency camp must occupy a strategic point. The lay of the land will govern any possible drift crossing to the Prairie Dog. Whether a storm strikes out of the North or Northwest, the cattle will take advantage of any shelter, and the first arroyo they reach will carry them down to the main creek. My idea is to locate your camp at the mouth of the first arroyo east of the sand-hills.’

Joel and Manly had halted on the crest of the southern divide, between the Beaver and the Prairie Dog. ‘The only arroyo that puts into the Prairie Dog,’ said Joel, indicating the direction, ‘holds almost a due south course. For the last few miles it’s just a big dry wash. Old buffalo trails run down it to the main creek. The mouth of the wash is almost due south from headquarters. I led a drift down it two winters ago. Struck the wash about midnight.’

The site was miles distant and Manly had never seen the ground. ‘The mouth of that dry wash,’ said he, as if he had camped there, ‘is the ideal point for your dug-out. It’s a wonder some buffalo hunter didn’t make his headquarters there.’

‘There are thousands of old buffalo skulls along the Prairie Dog and around the mouth of that wash. Dell and I used them for seats around our camp-fire.’

‘I thought so. The buffalo faces the blizzard, drifting before it strikes. Cattle, caught out in a storm, drift with the wind until it breaks. Nature intended the buffalo to face the storm, and clothed his fore parts accordingly, but gave the cattle the instinct to drift.’

‘Another advantage,’ suggested Joel, ‘in case a storm strikes in the evening and we cross the divide at night, the arroyo will pilot us into camp. We can find it the darkest night that ever blew. Let’s locate the dug-out and stable to-day, and either one of us can bring the haying outfit over later.’

The brothers were fortunate in able assistants. In knowing the inner nature of cattle, their deeps and moods, the Texan stood in a class by himself.

In reading the topography of the surrounding country, Manly was able to tell that cattle adrift would concentrate at a given point. The sand-dunes on the right would turn a cattle drift from the Upper Beaver, and, as did the buffalo, the drifting herd would instinctively cross at the same landmark. It was not in wearing a sombrero or leather chaps or gaudy neckerchief that one qualified as a cowman, but in that sure knowledge of every act, mood, and whim of the cattle of the range.

Joel’s earnestness kept his outfit at concert pitch. ‘One of our sponsors was a soldier,’ said he, ‘and always used military terms in fortifying to meet a winter. This work of building dug-outs, getting in supplies, pickling beef, and the like, he would call bringing up the ammunition and looking after the lines of entrenchment. He believed in strong reserves, in seeing that the firing line lacked for nothing, and then he expected a man to hang and wrestle like a dog to a root. He claimed the only safe way to hold cattle in the winter was to do your sleeping in the summer.’

The new men were selected with care. All four were Texans, two of whom had weathered winters in the North, young, rugged fellows, horsemen of steel, tireless, undaunted, immune to hunger, fair or foul weather, so long as horse or mount of horses could respond to the call of duty.

The new men were coached daily. ‘One extreme follows another,’ said Joel, ‘and last winter let us off easy. We may never see another as severe as our first, but I’m counting on some sure-enough winter this coming one. If it happens to be only dry and cold, there’s nothing to fear, but sleet and wind are to be dreaded.’

‘Wind especially,’ emphasized Sargent, the foreman, nodding to the new men. It not only asks about your summer’s wages, but it searches your very soul for the sins of your ancestors. It ranges from a balmy zephyr up to a blue-cold wind that will shake a horse off his feet. If your hat blows off on the Beaver, wire your friends in dear old Texas to pick it up. These plains are surely some windy in winter.’

The winter outfit numbered eight all told. In addition to those already mentioned were two brothers, Bob and Verne Downs, who were stationed at headquarters. They were utility men, either one of whom could cook, wrangle horses, take out a wagon, or make a hand in the saddle. They had proved themselves on the trip up from Trail City and at the isolation camp in the sand-hills, where the last herd was held in voluntary quarantine. Dale Quinlin had come in with the same cattle, while Reel Hamlet had been dropped early in the fall with the Stoddard herd. All four were valuable additions to the line-riders of the previous winter.

Joel and Bob Downs would ride from headquarters, though the other two knew the lines equally well. Substitutes might be called for, as Manly had reports to send out or mail was expected, while some one must visit the ranches on the Republican River to the north. For mutual advantage cowmen were forming local associations, and with the increased number of cattle on the Beaver, the brothers were awake to the importance of protecting their every interest. By thus joining with some valid organization, which published an annual pass-book, giving a list of its members, the location of their, ranges and brands in detail, the members would be mutually protected. No animal could drift so far but a comparison of pass-books, represented in a national association, would reveal its owner.

One evening, near the close of November, Dell and Sargent rode into headquarters from the north. The latter, when crossing the divide, reined in his horse and voiced the belief that he had scented smoke. On reaching the ranch, a general inquiry among those afield that afternoon failed to confirm the report.

‘It was a vagrant breeze,’ admitted the foreman. ‘Still there is no mistaking the smell of burning grass. Hunting parties in the sand-dunes may have been careless with fire. Or some fool might have set the prairie afire just to see it burn.’

Joel tensed rigid at the report. ‘North on the Republican they burn fire-guards to protect the range,’ mused the boy. ‘If the Beaver Valley was to burn—’

‘There’s a world of dry grass to the west, frost-killed into tinder,’ continued Sargent. ‘Let’s ride out on the divide after dark.’

Nightfall confirmed the danger. Under a low horizon the harbinger was marked on a wide front, a mere glow in places, but clearly distinct on the flanks. The distance was unknown, but the night air was tainted with the fumes of burning prairie.

‘Joe,’ Inquired the foreman, on returning, ‘how are you on fighting a prairie fire? Wear any medals?’

‘I’m the best what am,’ answered Manly. ‘Lead me to it.’

‘You’re there now. This outfit moves at daybreak to fight fire.’

‘You mean back-fire?’

‘Of course; back-fire against the big blaze.’

A general consultation followed. There was permanent water in the Beaver, several miles above The Wagon, an outpost established the winter before, where a camp could be located. The remuda must be taken along, a commissary outfitted, as if it were the beef-shipping season. An old plough was unearthed, the mowing machine was called into service, with water barrels in each wagon.

‘Lucky thing that our corn is all freighted in,’ said Joel. ‘How many sacks shall we take along?’

‘Only enough for two teams, say three days’ supply,’ answered Sargent. ‘By that time the fire will beat us, or we will beat it. Nothing but backfiring or a heavy rain can stop the flames.’

‘And here’s where you young fellows can cut out sleeping altogether,’ said Manly. ‘When you fight fire, you don’t sleep any until it’s all over. Hardly worth while taking blankets along.’

A restless night passed. Fortunately the teams were in hand, and an hour before daybreak two wagons moved up the valley under emergency orders.

Dell took the lead. ‘Follow the old wood road to Hackberry Grove,’ urged the foreman. ‘Touch at The Wagon and lighten ship of the corn. We’ll bring the guns and everything else that’s overlooked. Shake out your mules; unless this range is saved, you have no other use for teams. Roll those wagon wheels.’

Dawn came begrudgingly. Heavy smoke-clouds, hanging low, filled the Beaver Valley, somber as a shroud. The remuda was even difficult to locate in the uncertain light of early morning.

It was an odd cavalcade that moved out from headquarters. Two carried axes and a third a scythe, while rolls of gunny-sacks were tied to every saddle cantle. The entire remuda, over a hundred strong, was taken along. Not a man was left behind.

‘We’re off!’ sang out Sargent, swinging into the saddle. ‘We don’t know where we’re going, but we’re on our way. You lads with the axes shake out your horses and skirmish some wood at the Grove for camping. Don’t spare your horses, because the remuda will be right at your heels. Jingle your spurs.’

Nothing but the fear of fire would have justified the pace. The axemen were lost to sight before the saddle horses could be swung into action. Three horsemen whirled their ropes at the rear and along the flanks of the flying squadron. Calves sprang from their beds in the tall grass and fled, followed by frantic mothers. The older cattle, sedate in manner, beheld the apparition with wonder, stood firm or turned tail, distance governing, while the bulls bellowed their defiance. Surely a strange disturbance in a peaceful valley!

The wagons were overtaken at the Grove. Joel and the foreman pushed on to select a camp above. The Wagon, a former camp, was passed without a glance. Pools were known to exist up the creek, though one month was no guarantee for another, and water, in quantity, was essential to the work in hand.

A known pool — a long pond — afforded the required water. The site was only a mile above the old line-camp. The two scouts dismounted from badly spent mounts and slackened cinches.

‘I want Manly’s idea of the plans,’ said Sargent. ‘If we can burn a lane to the sand-dunes, and north to the divide between here and the Republican, it ought to check the course of the fire. So much depends on the wind fanning the oncoming flames. It might jump a mile in a strong wind and be unable to cross a ploughed furrow in a calm or in damp grass. With any breeze, a prairie fire runs wild during afternoon and evening hours.’

Joel admitted that to him fighting fire was an unknown task. ‘We used to notice fires in the spring, north and south, but never in the west in the fall. Jack, I want you to take full charge.’

‘Burning the range in the spring is a good idea. It gives the cattle fresh grass. I wish Manly would make haste.’

‘If I catch your idea,’ bluntly said the boy, ‘backfiring means to burn against a fire beyond control.’

‘That’s it. Meet it, burn into it, against the wind. Widen the breach, if possible, miles wide, but hold your back-fire safely under control. For that reason we must burn by night, widen the burnt lane, keeping your own fire in hand. If Manly agrees, we’ll start our back-fire from this pond. We don’t need this range this winter, and it will give us early grass.’

Manly rode up in advance of the others. The foreman’s plans were adopted. ‘You and Joel take the plough and work south into the sand-hills, and I’ll take the mower and work out toward the divide. Cut the ground into sections, from a quarter to a half-mile in length, and leave the last mile unburnt. Never let your fire get away from you on the flanks. Give us two or three days and we’ll know where we stand.’

Camp was made. The men were divided into two squads. The mules were refreshed and things set in readiness. Both crews would work out from the same camp, at least for the first day and night. The one who best knew the work led the way, the others eagerly attentive.

The foreman took charge to the north, assisted by the Downs brothers, while Dell brought up the rear with horses under saddle. Old hand hay rakes cleared outward, to be burnt later, the swath of the mower’s sweep. At first, at every few hundred yards a notch was cut to the depth of a few rods, on the side where later the torch would be applied. By firing the indent first, the flames would feed in various directions, presenting an uneven front.

The work was slow and tedious. On the one hand lay the home range, on the other a menace of desolation, admitting of no hasty or uncertain step. Where the grass grew rankly as many as three swaths were cut down in forming the base of the fire-line.

‘I’m cropping the grass to its roots,’ said Sargent to his helpers. ‘Rake the ground to the last straw, and we can whip out any loose fire in the stubble. Dell, tramp down those heavy fronts of sedge and blue-stem with your saddle horses. Tramp it down for a full rod, so the fire will feed slowly. Slight nothing, lads, if we expect to take the wagons home.’

By early evening, the foreman had laid a deadline of fully five miles, while the plough had gathered a double furrow of nearly the same distance to the south. Mounting their horses, both crews hastened back to camp, where hunger was satisfied for the moment and fresh mounts secured.

‘What’s the word?’ inquired Manly, as every possible straw of the situation was carefully thrashed over.

‘We ought to get a lull in the wind between sunset and dark,’ suggested Sargent. ‘The sun will set in a few minutes. This breeze is a trifle strong for narrow base-lines. Fill the canteens and soak the gunny-sacks. Everything that is worth while, and will burn, should be in the wagons. Joel, suppose you hang around camp for half an hour, and, in case the fire jumps the dead-line on us, run these wagons over on the burnt ground. You can snake them out of danger from the pummel of your saddle. Now, that’s about all, except to apply the torch.’

Every man awaited the word with impatience. The older men walked through the heavy grass; it crushed brittle in their hands and fairly crunched underfoot.

‘There ought to be moisture in the air within an hour,’ suggested Manly.

‘Not unless the wind falls,’ answered the foreman. ‘This is some dry country. Feel the heat in this dry grass.’

‘She’s lulling,’ announced Dell. ‘Can’t you feel it?’

Still the word was withheld. Sargent walked up the dead-line alone, but hurriedly returned.

‘Fire the margins of the pond first and apply the torch north and south,’ said he quietly. ‘Try and make it back to the wagons by daybreak. Keep your horses safely in hand.’

Matches flashed at the word and tiny flames sprang up. The men had wrapped torches of long grass, could make others as needed, and the backfire opened promisingly.

A lazy breeze lingered. ‘Just enough air to make it feed greedily,’ observed the foreman, who had remained with Joel at the camp. ‘We ought to burn a fire-guard a mile wide to-night. Your side is burning like the flame of a lamp; mine is lapping it up in eddies.’

He mounted his horse. ‘These boys of mine are liable to overrun the trail, like young hounds. I must overtake them. Your men have old heads.’

Within an hour the back-fire was a mile wide. By midnight it had covered a front of over five times that distance, a slight semicircle, eating in slowly.

Late in the night, Sargent called his boys together. ‘We’ve burnt our limit,’ he announced. ‘We have barely a mile yet of dead-line cleared. It will take several hours to get the team back on the job. Let’s double-team and burn a second and third counter-line, a quarter of a mile apart, entirely back to the creek. Fire it just wide enough so that it will consume itself before morning or before the sun rises to-morrow. Wrap up a gunny-sack full of torches so we won’t have to dismount. Notice the fire to the west; ten or twenty miles nearer than last night. It’s spreading north of the Republican; see the low horizon line.’

Dell and Verne Downs took the inside circle, swinging low from their saddles and applying the torch about every fifty yards. The outer line was fired almost entirely by Bob Downs, who rode leisurely to the rear of the inner line, frequently dismounting to apply a match and renew his torch. The foreman covered both lines, as the firing must be finished fully an hour before daybreak.

When the task of the night was nearly finished, Sargent located Bob Downs. ‘I’m on my way back to our own flank,’ said he. ‘The unexpected might happen; the wind might whip around to a new quarter and catch us asleep. Now, have our team on the ground at sunup and fresh horses for every man. We’ve got a good fight started, and excuses are out of order. If you can think about it, you might bring me a can of tomatoes and a cold biscuit.’

Manly’s crew also burned back-circles to the creek. Opposite camp, where the torch was first applied, the fire had eaten its way only a few hundred yards, fighting against random breezes. Under any favorable air pressure, the interstices between the circles would burn out within a few hours.

Dawn found every man in the saddle. On arriving on the northern flank, two strangers were present. ‘These lads are from the Republican,’ explained Sargent. ‘They saw our light and have come over to lend a hand. They report a fire-guard, burnt a mile wide, north of the river. That was the glow that we saw last night.’

Turning to the men the foreman continued: ‘Follow this fire-guard down to the wagons. Skirmish something to eat and a change of horses. One of you report to Joel Wells, over south, and the other return here. You didn’t aim to sleep any, did you?’

‘They’ve quit sleeping over on the Republican,’ admitted one of the tired men, lifting himself heavily into the saddle. ‘This fire-guard will take us to camp, you say?’

‘That comes near being neighbors,’ observed Sargent, once the lads were out of hearing. ‘The ranches on the Republican are in the same boat with us. It’s a common fight and calls for all hands.’

Extending the fire-guards on the Beaver was merely a repetition of the day before. The commissary, the base, must be brought up to the front. Near the middle of the afternoon, Dell and Verne Downs were dispatched with the team to bring up a wagon, a barrel of water, and a fresh relay of horses.

They returned before dark, to find everything in readiness to apply the torch on a new five-mile front to the north. The south, the ploughed, line had made similar progress, with its commissary also in hand.

By midnight the Beaver back-fire was fully eighteen miles in length, while a similar one on the lower side of the Republican snailed out to meet its neighbor on the south. Another night and they would surely meet.

‘I don’t like the looks of that wild fire on our west,’ admitted the foreman, when his boys gathered at midnight at the extreme limit on their flank. ‘You don’t notice it now, but early this evening, while the grass was dry, she threw up a red tongue that was far from friendly. It may be forty miles away and it may be only thirty. In the afternoon, when the wind lends a hand, she steps out some.’

‘It’s reported that the fire started near the Colorado line,’ said a boy from the Republican. ‘It seems that it got away from campers.’

‘More than likely,’ agreed Sargent. ‘Now, you boys burn your circles a trifle wider to-night. The ones you laid last night burnt out in four hours. I’m going back to the Beaver and lay a new line of back-fire to meet your outside circle. That’s you. Bob, and the boy from up-country. Bear in mind, lads, this byplay is to save the cows on the home range. I’ll pick you up before daybreak.’

The foreman rode hard, hugging the fire-line, broken and jagged like saw-teeth. On reaching the creek, he rode up its bed, through the fire, and was soon dropping matches to throw a signal to his own men.

On meeting the latter, Dell and his partner were detailed, after firing their line to the creek, to bring up half of the remuda.

‘Another day will finish it,’ said the foreman, ‘when we can send everything back to safety. We’re working now without rhyme or reason, without day or date, and at the mercy of the elements. We must keep things in hand. We may have to run ourselves. This isn’t a fire in the kitchen stove.’

It was daybreak when the saddle horses reached Sargent’s wagon. ‘You fellows come through on time — like an ox train,’ admitted the foreman, who had leisurely returned to his post. ‘You must have split the remuda on a guess.’

‘The other boys had hobbled the bell mare,’ said Dell defensively, ‘and we made a running cut in the dark. On time, are we? These twenty-four-hour shifts cover a lot of ground. I could fall out of this saddle and never wake up.’ ‘

‘It’s the making of you, son. You’re a coming cowman. I’ll put you on the mower this morning, and that will shake you up. A mowing machine is the very trick to keep a sleepy boy awake.’

An early start was fortunate. By ten o’clock a stiff breeze was blowing out of the north. An hour later it was veering to the west. At this instant it was discovered that the men from the Republican were burning out the approaching fire-guard a mile wide, the fire following the ploughs.

‘That calls for the torch,’ announced the foreman. ‘Wet your gunny-sacks and burn slow but sure. Those men must know something.’

They did. A courier arrived with the information that two ranges, north of the Republican, were burnt the day before. That the flames jumped a fire-guard a mile wide; that if the wind veered farther to the west, under any pressure of air, the flames were due to sweep down the divide that afternoon.

‘Throw caution to the winds,’ pleaded the messenger. ‘Burn now; apply the torch. Fight fire with fire.’

‘Is that the word?’ inquired Sargent.

‘It’s the only chance.’

‘How soon will your ploughs meet our mower?’

‘By noon, easily.’

‘Verne, round up the remuda and tramp down any tall grass. Neighbor, catch a fresh horse and lend the boy a hand. Flatten out those strips of blue-stem grass.’

It was tense work. Some sixty saddle horses were sent in a gallop over the dangerous spots, doubling back and forth where necessary. The foreman brought up the rear, whipping out numerous fires, any one of which would have laid waste the home range.

The indents, cut into the lee side of the fire-guard, proved valuable, allowing the flames to run in three directions. By early noon the fire-line across the divide was finished. The burning crews met; the face of every man and boy was soot-stained; every canteen was drained.

‘Our wagon will be here directly,’ announced the Beaver foreman. ‘We had half a barrel of water left this morning. This is a dangerous point on the line. Let’s burn some back-circles and widen this fireguard at least a mile.’

Dell arrived with the wagon. ‘A band of fully forty antelope crossed the fire-guard back about a mile,’ he announced. ‘If I hadn’t been in such a hurry, I might have shot one.’

‘Those antelope, moving, indicate danger,’ announced Tony Reil, an old ranchman from the Republican. ‘Better make things secure.’

‘Just my idea,’ agreed Sargent. ‘Unload this water barrel. Knock the lid of a crate of tomatoes and give every one present a can. Dell, take a saddle horse with you and cache the wagon alongside the pool at our first camp on the Beaver. Pick up all the loose stock and tie in with Joel and Manly. Report that this end of the line will win or lose this afternoon. I’ll keep the carbine and the axe.’

He turned instantly. ‘Bob, you and Verne drift up a passel of cattle, with bulls among them.’

‘That’s the talk,’ sanctioned Reil, the cowman.

‘Son,’ continued the Beaver foreman, addressing the first volunteer helper, ‘will you please take charge of our remuda. You’ll find a lagoon on the left, about two miles down the divide. Water the saddle horses and hold them within signaling distance. Anything else?’

The question was addressed to Tony Reil. ‘Empty that crate of tomatoes into this water barrel. We must be here until late, and we may be here in the morning. Now, let’s you and I thread this back-fire and ride out a distance, just to see what we can see.’

‘Fellows, burn back-circles,’ urged Sargent, as they rode away.

In the short buffalo grass the back-fire was easily threaded. A curtain of smoke hung like a pall over the divide. Whirlwinds threw up, high above the horizon, spirals of smoke. Balls of fire shot upward. A thousand antelope were in sight at a time, sullenly moving down the watershed.

The two men only ventured out a few miles. The wind was fair in the west. The old cowman looked at his watch. ‘Coming up thirty minutes late today,’ he commented. It jumped the fire-guard on Hillerman’s range yesterday just at two o’clock. By sundown it took fighting to save the hay and stabling. An hour earlier, neither one would have been saved.’

A shower of ashes fell. ‘There’s a hint,’ observed the foreman. ‘Let’s drop a few matches on our way back. It’s only a question of time now.’

The detail of cattle were in sight. Sargent met them and shot an old bull. ‘Kill a couple more,’ said he, handing the carbine to Bob Downs, ‘and stampede the others to safety. I’ll split this one and have a pair of drags ready, if the fire jumps. This is our last card.’

It was a harsh but sane precaution. Within an hour a steady rain of ashes was descending. Tongues of fire were visible above the black line, rolling forward, and dipping to an end in clouds of smoke. The air was fairly filled with charred debris. A palm held forth was quickly covered with ashes; every one whipped it from his hat; clothing took fire. An oppressive feeling gripped every heart. The horses trembled.

The foreman distributed his men along the danger-line, only a dozen all told. It seemed hopeless. Small fires broke out across the fire-guard, when watchful horsemen dismounted and whipped them out with wet gunny-sacks. One assumed dangerous proportions, in the midst of which Manly and his men arrived and the blaze was smothered. From the lower end of the line the danger was apparent on the divide, and every one had hurried to the scene.

And not a moment too soon. Apparently, as the wind-swept fire met the counter-blaze, great tufts of grass, blazing like rockets in midair, were lifted and carried over a mile, far over the fire-guard, and igniting a front fully a thousand yards wide. Fortunately it happened between sunset and dark, the wind lulling with the evening hour.

The remuda was signaled up. Orders rang out. ‘Bob, take fresh horses and split those cattle that you killed. Take half the outfit and make a fight from the lower flank. Let the back-fire run. Jump onto this front blaze.’

Detailing Joel and Dell to his assistance, Sargent rode to the first animal killed. Ropes were noosed around the pastern joint, fore and hind foot, and from the pommels of saddles the split carcasses were fairly floated astride the burning front. Ropes were lengthened to about thirty feet, allowing the horses to straddle the fire, the drag, flesh-side down, smothering, crushing the blaze. Horsemen followed closely, dismounted, and whipped out rekindling flames.

With the falling of darkness the fire was making a headway of fifty feet a minute. But once the flanks were turned, leaving the rear to exhaust itself, a shout went up, answered down the slope, now a hand-to-hand fight.

‘Take my rope,’ said the foreman to Dell. ‘I’m going around to see how Bob’s making it. Keep your rope out of the blaze and veer your horse away from the fire in gusts of wind. Be careful and don’t singe him. Swing well out from the blaze. Who’s handling the other half of this beef?’

‘Joel and Mr. Tony from the Republican.’

‘Good men at a fire. Shift horses often on those drag-ropes. I’ll be back directly.’

Down the slope the fire was equally well in hand. ‘Girls, you’ve got her whipped,’ announced Sargent. ‘These drags are just about what the doctor ordered. Look back west. The big show’s over. Nothing more to burn unless we give our consent. She’ll die out in the sand-dunes.’

Before midnight the fire that had jumped the guard was crushed out. A few thousand acres of the Beaver range were lost. Westward, as far as the eye could see, a prairie fire, with a hundred-mile front, was smouldering to a quiet death. The back-fire had accomplished its ends.

‘If you boys will go down to our wagons,’ said the Beaver foreman to the men from the Republican, as they sat their horses surveying the field, ‘we’ll put on the big pot, kill a chicken, and churn. There’s water there, and we’ll wash our smutty faces and pull off a big sleep.’

‘There’s water in the river,’ said Tony Reil, reining away. ‘Drop over sometime.’

‘What next?’ inquired Joel.

‘Take the remuda back to camp. If the boys are sleepy, stand them up against the wagons and let them have a little nap. I want to hang around here an hour or so to make sure the fight is won. I’ll be in early in the morning.’

The foreman was late in reaching the wagons. There was no longer any danger to the westward; where the fire had jumped the guard at dawn every margin was critically examined. Fire was found smouldering here and there, some of which might have rekindled to a blaze. Every trace, even of smoke, was whipped out on the home side of the fire-guard.

The camp was a desolate sight. The wagons were cached on the burnt ground, and the men had unsaddled over the line, in rank grass. They lay about, as if they had fallen in an Indian massacre. A number of men from the Republican River, compelled to return for their mounts, were among them. Sargent seemed immune, an iron man, fully familiar with the sleep of exhaustion, and merely rode by to satisfy himself, dismounted and kindled a fire.

It was noon before many of the men awoke. ‘Let me have four hours’ sleep,’ said the foreman to Joel, the first one to awake, ‘and this afternoon we’ll ride south into the sand-hills. I want to see the end of the back-fire. If it looks safe, we’ll camp to-night at The Wagon and go home in the morning. Better send a wagon out and gather any plunder that we abandoned north of here. Let them take a keg of water along and drown out any smouldering fires. Call me promptly. I’ll be asleep in that heavy grass across the creek.’

* * * * * * * * * *

December passed without a move on the part of the cattle. Several light snows fell, storms threatened, each passing away with an angry horizon, but leaving the herd contented. Joel met Manly each morning, and Sargent during the evening ride, when every phase of the weather was discussed.

‘What do you think of the weather?’ became a standing inquiry on the part of Joel, when meeting either one on the line.

‘I’m not even the son of a prophet,’ was Manly’s evasive answer. ‘Try it yourself, and you’ll find out that you’re earth-born; that you lack the gift of prophecy.’

‘You never ask my opinion on a cow or horse,’ replied the foreman, when pressed with the regular question, ‘and don’t try and flatter me into turning weather prophet. Possibly the mantle of the prophet Joel has fallen on your shoulders; he was a range man. You try it this winter. It always makes me out a liar.’

The boy knew his limitations and avoided all nonsense. ‘Manly will have to go to the railroad with his monthly report, and the very first chance I want to go to the Republican. We both can’t leave at once. I wish we knew ‘

‘Turn weather prophet,’ insisted Sargent. ‘Forecast a bad storm, and if it doesn’t come, we’ll hail you as a good prophet. We’ll ride the lines just the same, anyhow.’

Early in the year, Manly went to the railroad with his December report. It was flattering in the extreme; typical of the pastoral contentment which reigned on the Beaver. Two days were allowed for the round trip, which, under normal conditions, was ample time. On this particular trip. Manly started at dawn, and as the day wore on an uneasiness was felt, not only by the courier afield, but by those remaining behind. Every hour carried the harbinger of a change of weather; and even when the riders parted on the lines at evening, it was still an open question what the day might bring forth.

This time the expected happened. The day ended as balmy as a spring morning. The cattle were ranging out on the watershed to the north and to the burnt country above the upper line camp. When the patrols returned to their respective quarters, only a few scattering bunches of cattle were in sight, all of which was well north of the Beaver.

With the falling of darkness, a change in the weather could be sensed. Within an hour after nightfall, a wind swept out of the north, raw to the freezing point, and every man in the outfit, absent or present, was aware of the task that confronted them. The different camps were alert to the necessity of the hour. Quinlin was serving as a substitute at Trail Camp, and before ten o’clock that night, Dell and Sargent rode into headquarters, bringing their relay horses and blankets.

‘What do you think?’ hailed Joel, busy outfitting a wagon, as the others dismounted.

‘I think we’ll play in big luck if we head the drift on the Prairie Dog,’ answered Sargent. ‘The storm struck early, and out on these flats the cattle must drift until they strike shelter. If they cross this valley, it’s good-bye, Irene, I’ll meet you on the Prairie Dog — possibly, perhaps. Unlash this bedding; my fingers are all thumbs from this cold.’

Sleep was out of the question. Dell and Verne Downs were to bring the wagon in the morning. ‘Pilot the commissary in to the emergency camp,’ said Joel to his brother, ‘and then ride for the Upper Prairie Dog. If the cattle are adrift, the rest of us will ride to their lead; if they’re moving broadside, we’ll turn in the flanks. If they’re bunched, we’ll turn them at the new Dog House, at the mouth of the dry ravine. Once you sight cattle, it will give you a line on the situation. And be sure and start your wagon an hour before daybreak.’

The start was made at midnight, with every extra horse under rope. Sargent took the lead, and with the wind at their backs the trio defied the elements. Bob Downs bringing up the rear.

‘Do you suppose those fellows at the lower camp will know enough to start to-night?’ insisted Joel, mounting his horse. ‘Manly’s gone, you know.’

‘If they’re cowmen, they will,’ answered the foreman. ‘The cattle won’t wait until morning.’

A sifting frost filled the air. Under an ordinary saddle gait, the horsemen would cross to the emergency camp in four hours. But as they neared the divide, the storm struck without mercy, the led horses crowded those under saddle, and the only relief was to shake mounts into a long gallop. On reaching the southern slope, a lull in the storm was noticeable, the dry wash was entered as if it were day, and an hour before schedule time the horses were under shelter and the men had kindled a fire in their own Dog House.

‘The wind has held from the same quarter,’ announced Sargent, ‘which is in our favor. We’ll turn any possible drift before noon.’

A breakfast was prepared from the emergency stores. Coffee is a staple in every cow-camp, and once the men were warmed up, fresh horses were saddled to await the dawn. Conjecture was riot as to whether the cattle were drifting or not, when Hamlet and Quinlin rode up and hailed the dug-out. They were benumbed in their saddles, having quartered the storm, but once the comfort of the shack and its bounty was theirs, the situation became known.

‘Cattle adrift?’ repeated Hamlet. ‘Why, Dale and I have run amuck drifting cattle every hour. We left our dug-out at ten o’clock. You fellows must have left before sundown.’

‘We’ve been here a little over an hour,’ said Joel, watch in hand. ‘You’re sure that the cattle are drifting?’

‘The creek bed’s full of them,’ answered Quinlin. ‘We struck it several miles below and had to grope our way up here.’

‘Come on,’ urged Sargent; ‘dawn will be here within half an hour. Once you fellows get warm, ride your own end of the line. Bob and Joel will go west, and I’ll ride south a few miles, in case any cattle have crossed the Prairie Dog.’

Daybreak found Sargent miles out on the flats, leading to the next divide south, without an animal in sight. An hour later the sun flashed forth, for a brief moment, but the sifting frost blinded the lone horseman. Satisfied that human vision was of little use in the present glare of icy sheen, he turned westward in the hope of picking up any possible trails. Meanwhile Joel had cut the spoor of drifting cattle, and while running it out, was overtaken by the foreman.

‘We’ll head this drift within an hour,’ consolingly said Sargent, on overtaking Joel. ‘Every hoof ought to be found over the next divide. There’s nothing adrift now but new, through cattle.’

On reaching the divide, a surprise awaited the pair. Within a mile, over the crest, a lone horseman had turned the drift of fully five hundred cattle. Shaking out their horses, the two rode to his assistance, conjecture running wild as to who it might be at such an early hour in the morning.

Sargent’s reasoning faculties, rather than his vision, solved the mystery. ‘It can’t be any one but old man Manly,’ said he, shouting into Joel’s ear. ‘That old boy couldn’t sleep in a warm bed, knowing that these cattle might be adrift. I can almost make out his horse. Yes, it’s old Joe!’

He was found, benumbed, speechless, bordering on a stupor, and unable, without assistance, to dismount. He was fairly dragged from his horse, rubbed with snow, raced around in a circle, the twinkle in his eye the only symptom of life. On recovering, it was learned that he had left the station, timing himself so as to reach the Prairie Dog at daybreak. He had come up the trail, riding into the eye of the storm, and only quartering it after turning westward. He reported the one in hand as the only drift, and was sent direct to the emergency camp.

Before noon, the lead of the drift was returned to the Prairie Dog. The wagon had arrived early, and with all hands in the saddle, the flanks were turned in, the country scouted far and wide, and by evening every hoof was bedded under the bluff banks of the creek. The cattle had reached the Prairie Dog, covering about the same front as their winter range on the Beaver, and were left scattered for the night.

Three days of raw weather followed. The wind continued from the north, lulling with a falling temperature at night, and of a necessity the line was held on the Prairie Dog instead of on the home range.

‘What’s the difference?’ said Sargent, pleading for delay before starting the drift homeward. ‘The corn tastes just as sweet to the horses here as at home. We have our own Dog House, and even if we do sleep a little cold, it’ll make us get up earlier. When it warms up, the cattle will want to go home. As long as we know where the teepee is, and have the cattle in hand. I’d as lief be lost as found.’

The Dog House was a comfortable shelter. ‘I know it’s not good manners,’ said Manly to Joel, ‘to complain of your chuck, but the architect who planned this emergency camp entirely overlooked the comforts of a guest-room. Here I must sit on a sack of corn or on buffalo skulls. At my sunny home on the Pease River, we wouldn’t treat a Mexican horse wrangler this way. And I’m your only guest.’

‘Verne,’ said Sargent austerely, ‘to-morrow rack up more of those buffalo seats. Build a little platform of skulls at the corner of the fireplace, for the guest of honor. Build it high enough so that Colonel Joe can issue orders from a throne of skulls. Let no one, for a moment, lose sight of the fact that Joe’s our guest, from the far, sunny South.’

A second storm, accompanied by sleet, followed, not severe enough to drift the cattle, but compelling the outfit to remain a week afield. The weather faired off the third day, when the wintered cattle, led by cows, began the homeward drift. Coming voluntarily on the part of the herd, it was looked upon as a good omen.

‘There’s the advantage of a few cows,’ said the foreman to Dell, when the homeward drift was noticed. ‘As long as there is a cow present, a steer is always quiet and contented or willing to be led by the horn. A cow will go back to the same spot, year after year, to give birth to her calf, while a steer is a roving rascal. A bell mare has just the same influence over saddle horses. A mare and colt will hold a remuda of horses better than a wrangler. But the moment one gets out of hearing of the bell, he’s a gone gosling and will nicker like a lost child.’

All signs fail in bad weather. One week after the first storm struck, and only a few hours later at night, the harbinger of a blizzard turned the homeward drift to the shelter of the Prairie Dog. The change was sensed within the dug-out, the entire outfit turning out and noting every phase of the situation.

‘Farewell, Beaver, farewell. Prairie Dog,’ lamented Sargent. ‘We love you, but we must leave you!’

‘This is more than we bargained for,’ said Joel; ‘and we have no emergency camp to-morrow morning.’

‘We can make the railroad our next base of checking the drift,’ suggested Manly. ‘Better load the wagon now and start a few hours before daybreak. The cattle are adrift this minute.’

It required stout hearts the next morning to take out a wagon and defy the elements. That the major portion of the herd was adrift there was no question neither was there a moment’s hesitancy to saddle and try and ride to the lead. Four o’clock in the morning was the hour agreed upon, and, leaving Bob Downs and Quinlin to hold the line on the Prairie Dog, men and horses humped their backs and took the storm. It was possibly not so cold as the first one, but the velocity of the wind was more severe, enough to whip the cattle into a trot across the flats and exposed places. Given a seven hours’ start, there was little hope of overtaking the drag end of the herd under thirty miles. The cattle were off of their home range, away from known shelters, and those instincts of life which taught them to flee from an enemy also warned them to drift with a blizzard.

An outline on the herd, after the first storm, revealed about half the cattle on the Prairie Dog. The latter line was covered by Quinlin and Downs at dawn, the trial of the morning being to turn a second drift from the Beaver. Among the latter were hundreds of brands, unknown to the detailed men, but, given the advantage of light, the drift was checked, two thirds of the cattle coming down the dry arroyo, and turning in to shelter above and below the dug-out. While patrolling the line, the detail was joined by two horsemen from the north, who reported themselves as belonging to an outfit from the Republican River, then encamped at Wells Brothers’ ranch on the Beaver. The men from the Republican predicted that the present would be remembered, for years to come, as ‘the big drift of January, ’88.’

Meanwhile, the main outfit had held together until dawn. Again leaving Dell to pilot the wagon and saddle stock, a quartet of horsemen gave free rein to their best mounts and rode on with the storm. Trails of drifting cattle were seen, stragglers were passed, the railroad reached, with no knowledge of the extent of the drift. Without a halt a wide circle was made to the south, hundreds of cattle were caught, moving with that sullen stride which knew no relief until the storm abated.

‘What do you think?’ inquired Joel of Manly, on meeting at noon.

‘We may have the lead in hand, and again we may not,’ replied the latter. ‘One thing sure, we have reached our limit away from the wagon. We must make it back to camp before dark. And it’s going to be slow work, drifting cattle against this wind.’

Dell joined them in the middle of the afternoon. He reported having camped the wagon about a mile north of the railroad. A dry creek bed had been found which would afford shelter for the cattle, fuel had been gathered, as the night must be weathered in the open.

The back trail required patience. The herd had split into contingents, and to pick up and turn them homeward was no light task. The main herd turned a dozen times, but the men dismounted and fought them until the cattle yielded, facing the storm in preference to the mastery of man. Toward evening, the sun burst forth for an hour, and with the scattered bunches under herd, now numbering over a thousand head, five horsemen lined them out for camp. It was dark before the hungry herd bedded down, Dell and Sargent taking the first watch on guard.

‘How do you like it out West?’ inquired Sargent of his bunkie, as they met on the beat. ‘Do you think we’ll ever see The Wagon again?’

‘You ought to have been with us two winters ago,’ chattered Dell, his voice quivering. ‘There was a winter with whiskers on it. Talk about cold!’

The herd was bedded in the bend of a dry creek, and one man awake until midnight was sufficient patrol. Fortunately there was but little snow, tarpaulins were spread about the fire, tired men snuggled into their blankets, and the night blotted itself out.

It was fully thirty miles to the emergency camp, and a start was made with the dawn. The necessity of grazing the cattle was urgent, and scarcely one third of the distance was covered by noon. The wagon had taken the lead, dinner was waiting, and without a halt mounts were changed and the snail’s pace of the cattle was maintained. The wagon was excused, and after a final change of horses for the day, Dell followed with the saddle stock.

When darkness fell, some five miles to the south, the cattle were freed for the night. The weather had faired off, and on reaching camp the men from the Republican were still present. Reports were compared, and from the figures at hand, random as they were, it was openly admitted that the brothers had lost cattle during the present drift.

‘Well, suppose we have lost some,’ said Manly, ‘there’s still a grain of comfort; we did all we could. And they say that angels can do no more. It simply means that we must cover the spring roundups.’

‘In the winter of eighty-five and six, cattle drifted from the Niobrara down on to the Republican,’ remarked one of the men from the latter river.

‘You’ll have to go south to the Arkansaw River,’ suggested Manly to Joel. ‘Throw out your drag-net and throw it wide.’

Another day was lost on the Prairie Dog. The recovered cattle were brought in, the flanks turned closer, and toward evening the entire holdings, covering a ten-mile front, were started north. Camp was abandoned the following morning, the weather having moderated, many of the cattle not being overtaken before noon. Once the general drift was safely within the original, outer lines on the Beaver, the cattle were abandoned, and every one touched at headquarters before continuing on to their respective camps.

The outfit from the Republican had made a stand on the Beaver. Without molesting the home cattle, they had picked up nearly a thousand of their own, holding them under herd and penning at night in the old winter corral. A willing hand was lent them the next morning, and such cattle as had crossed to the Prairie Dog were gathered, the outfit starting home without the loss of an hour. Three storms had struck within a week, and no one could tell what a day might bring forth.

Joel was impatient to get a line on their own cattle. He and Bob Downs made several range counts, with the cattle scattered for twenty miles along the Beaver. Making due allowance for several hundred unclaimed strays among their own, the lowest possible count showed a thousand cattle short.

‘That would be about my guess,’ languidly agreed Manly, when informed of the count. ‘For the present, we’re short about that many.’

Joel drew a grain of comfort from Manly’s unconcern. ‘What are you going to say to Mr. Stoddard?’

‘I’ll write him that storms struck us in one-two-three order, and that we surprised ourselves by the good fight we put up. We weren’t caught asleep; no storm slipped up on the blind side of this ranch. I’ll tell my old man that you boys are planning to be represented at every round-up next spring where there is any possibility of a single Lazy H or Y being astray. I’d better suggest to Uncle Dudley letting me stay here until after the round-ups are over. What do you think?’

‘I wish you would,’ urged Joel. ‘We’ll need you then more than ever. You see, we never had occasion to go on the round-up. And don’t let Mr. Stoddard get uneasy. You feel sure, don’t you, that we’ll bring the missing cattle back?’

‘Bring them back!’ repeated Manly deridingly. ‘Well, we’re just about the boys who can bring home the bacon.’

The winter of 1887-88 is marked in range history by its vast cattle drifts. No section, north or south, was exempt from the rigors of the storm king. Even in the Texas Panhandle, drifting cattle lodged against the fenced lines of railways to such an extent that ranch outfits were rushed by rail to relieve the congested points. The cattle were held against the wire fences by the merciless winds, and nothing but prompt action, requiring hundreds of men and horses, saved the day.

The ranch on the Beaver was sorely tried. A second drift occurred the following month, and a third one during the latter part of March, both being turned on the Prairie Dog. Fortunately the drifts reached the latter creek during the hours of light, and were held by a patrol in patient waiting. Every man in the Beaver outfit was called to the saddle, and nothing but sleepless vigilance prevented a further drift from the home range. Thousands of strays came down from the north, and were held the same as if owned on the Beaver. Possibly some neighbor to the south, in observing the golden rule, was doing likewise. On the range it was possible to cast bread upon the waters.

Joel made several trips to the Republican.

Membership was secured in a cattle association to the north, and another in the south, both being State organizations. The Nebraska cattle men would be represented in all round-ups in Kansas, and it was a matter of economy with Wells Brothers to hold membership in each association.

‘We’re going to outfit two wagons,’ announced Joel to the line riders in council. ‘All our neighbors on the Republican will send men and horses, will share in the commissary expense, and in the wages of cooks and wranglers. I agreed to furnish a wagon and team, and we’ll have about thirty men and over two hundred saddle horses. If any of our cattle get through that drag-net, it’s because our eyesight’s poor or we can’t read brands. What do you think, Don Jose?’

‘You seem to have the lesson before school takes up,’ answered Manly.

Spring came early, the lines were abandoned, and the men at the outposts returned to headquarters. The herd had wintered strong, only a slight winter-kill among the old cows, and the ranch rested in contentment. The round-up for western Kansas was not yet announced, the first of June being about as early as the cattle would shed their winter coats, the brands be readable, the grass be capable of sustaining mounts, and admit of beginning the work. A month or more of idleness confronted the ranch, and Sargent, urged by Dell, revived the subject of hunting the wild horses at the outer lakes, over the line in Colorado. The presence of a band of mustangs became known, the fall before, while holding a new herd in quarantine.

‘I’m laying for you fellows with a green elm club,’ announced Joel, addressing his brother. ‘The lines of entrenchment were broken last winter, and our reserves of horses are not going to be wasted in hunting mustangs. With over a thousand cattle adrift, not a saddle will be cinched, not an ounce of horseflesh will be spent on any side issue. Gathering our cattle astray is the next big play coming up, and it calls for all hands and the cook. There’s a fine old man down on the Pease River who comes first. His interests don’t call for any wild-horse hunting this spring. Now, take your medicine like nice little boys, or haul wood for next winter, anything to take the wire edge off you.’

‘After those few remarks,’ said Sargent, bowing, ‘hunting the mustang, for the present, is a closed incident. Dell, I’m sorry we left The Wagon. It seems that our ability is not appreciated at headquarters. Picking wild flowers is all that is left us now.’

‘Some medicine talk,’ observed Manly, as Joel walked away. ‘And to the point. Save your horses is good advice. If we have wet weather during the spring round-up, that will take the starch out of you two.’

Early in May, notices of the round-ups began reaching headquarters. Work was to begin the 25th of the current month, in the association covering western Kansas, and in which the brothers held an active membership. Their mail multiplied; no less than half a dozen pass-books reached them, from members of similar organizations to the northwest, even from Montana. Letters poured in from cattle men in Wyoming and Nebraska, conferring power of attorney on Wells Brothers, to gather any cattle adrift, in the brands given and within the territory of their home association.

‘Do you understand this?’ inquired Joel, handing a power of attorney to Sargent.

‘Simple as sifting meal,’ answered the latter. ‘This cowman is unable to send men to the round-up in western Kansas. Instead, he authorizes you to gather his cattle, if any are found astray in the territory of your organization. You’ll have to furnish each of your men with a list of brands, not only of your own, but also those for which you hold authority to gather. Carry this document with you on the round-up, and when you claim a stray, do it on the written authority of its owner. This is just a detail, a side issue, in rounding out your education as a cowman.’

‘There are so many brands and a half-dozen powers of attorney,’ said Joel, hesitating.

‘Start a little book for each of your men,’ explained the foreman. ‘Give a list of your own brands on the first page. On the next one give the names of the cowman or company from whom you hold written authority, and a list of his or its brands. As fast as power of attorney is given you, add another page to your book.’

‘We have authority to gather over forty brands already.’

‘That’s nothing. Any man worth sending out on a round-up ought to keep a hundred brands in his mind. They’re as easily remembered as saddle horses.’

‘But why should so many come to us?’ queried the boy.

‘Exactly. Yours is the extreme northwest range in your association; it’s marked so on the map. Those powers of attorney come to you on account of your location. If you gather cattle, report to their owner. He may send for the strays, or he may authorize you to ship them on his account. It’s an easy word to spell.’

Joel hesitated. ‘It means a lot of work, and—’

‘Read the rules of the different cattle associations. Some make a fixed allowance for gathering and shipping expense. No cowman is so hidebound that he expects you to incur expense without allowing for it. You ought to be able to cover all your round-up outlay, in gathering stray cattle for others.’

The boy was apt. ‘Oh, well, if they allow us the expense of gathering and shipping,’ said he, ‘that’s a cow of a different color.’

‘Expense follows like feed-bills in shipping. Suppose you gather a carload of beeves for this man on the Niobrara River, you summer and ship them for him, is he going to complain of your expense bill? Not if he’s white. And what will it cost you? You must attend the round-ups, anyhow.’

‘I have the idea,’ said Joel, rising. ‘We’ll make out our brand-books to-night, when all the boys are in camp.’

‘Let each one make out his own. Then it’s his own writing, and he ought to be able to read his own brands. No other man can read my writing, and my brands look like quail tracks, or bear traps, or a lost bit of rope.’

An active week followed. The remuda was gathered and every horse put into trim. Joel made a hasty trip to the Republican, summoning the neighbors to the north to meet at their ranch, on or before the fifteenth day of May. Under orders of the home association, the work would begin in two divisions, and on the extreme ends of the range, tributary to the Arkansas River. This would require the brothers to send men on each division, and to be represented in a manner that admitted of no weakness on the outer, skirmish line. The spring round-up was held for the purpose of gathering the winter drift, and the ranch on the Beaver was conscious of having over a thousand cattle astray.

‘Our neighbors are all ready,’ reported Joel on his return, ‘and will be here on the dot. Allowing six from our ranch, it looks like we might have fifty men with our two wagons. We’ll provision and outfit at Grinnell, from which place each outfit will start to join its division. Every one seems anxious for a clean round-up.’

They came like an army of invasion. Two men arrived from the Arickaree, in Colorado, five days in advance of the day set, their blankets and camp kit on a pack-horse. Every day added to the numbers, and on the evening of the 14th, the wagon from the Republican came in, the numbers totaling fifty-eight men, four of whom were cooks and wranglers. The men were mounted, with from six to eight horses each, numbering over three hundred head, the pick of the ranches and fit for the coming work.

The outfits were made up at the railroad. Sargent was elected captain over the wagon on the western division. Dell and Hamlet accompanied it, and started for Trail City at once. The other wagon bore off to the east, crossing the old Texas and Montana cattle trail, and expecting to strike the river fully fifty miles northeast of Dodge. The spring round-up would thus cover, in its meanderings, nearly two hundred miles of the Arkansas Valley.

Quinlin and Verne Downs were left at headquarters. The other three, Joel, Manly, and Bob Downs, joined the wagon from the Republican, and on parting at Grinnell, the six drew aside for a final conference. Two extra powers of attorney awaited them at the station, and, while copying the brands into each one’s book, Manly suggested to those going west a few timely hints.

‘Now, you fellows lay low and shine only when there’s work to do. When the captain on your division calls for men to rope a steer, night-herd, or ride on the outside circle, be the first to volunteer. Let your work speak for itself, and in no time it will leak out that those — Y boys are cowmen. When you claim a cow, claim her for keeps. If any one cuts a steer back on you, don’t argue; go to your captain and lodge your grievance. He’s liable to be some old cowman, square and white, and he’ll see that you get your due. There’s always a lot of smart men at a round-up, claiming everything, and this one ought to bring every mother’s son to the front. The only way to fade those fellows is to show them that you are the real thing, and that they are only Sunday men. Now, get these brands straight, and overtake your wagon.’

Aside from their own, the boys from the Beaver carried authority to gather sixty-three alien brands. Each trio read and re-read them, memorizing the names of the owners and the ranges, and before the different rendezvous were reached, each one had his work perfect. Gathering so many brands might provoke comment, but with written authority, properly attested, there was nothing to fear.

The general meeting-points were of marked interest to Joel and Dell Wells. This was their first round-up; they were thrown in contact with men from other States, many of whom had started in a small way, and a touch with their kind served to broaden the brothers. Men from the mountains joined the western division, which numbered at starting over two hundred and fifty men and nearly two thousand horses. On the eastern division, the number of men and horses was slightly larger. It was the round-up following a severe winter, and calling for the best in men and mounts.

It was reasonable to suppose that all cattle adrift from the Beaver would lodge on the Smoky and Arkansas Rivers. The bulk of them ought to be found on the former watercourse, but, in consequence of the heavy drift, the entire range of the home organization would be covered.

The work began on time. In fact, the afternoon before the date set, an outside circle swung around, drifting every hoof into the valley. The night before beginning the work, captains over divisions were selected, with captains over wagons to execute general orders, twelve on the eastern and ten on the western. Each division would move to a meeting-point, work governing the pace, and carrying the cut of strays with it. The outside circle, an advance guard, led the work, shaping up the cattle, so that on the arrival of the main body, there was nothing to do but cut out all strays and move on. The strays were driven by a detail, like trail cattle, often missing a round-up and only joining the main camp at night. Each wagon had its own horse wrangler and cook, who moved ahead to noon and night camps, and answered to the orders of its own captain. All details of men were made from each wagon, and the rapidity with which a perfectly organized round-up handled cattle seemed marvelous. Ten thousand cattle was a small morning’s work.

Each man cut his strays into a common herd. As the work progressed, this contingent was added to daily. On reaching home ranges, all strays were claimed. This required a morning hour, and every owner must serve notice where and when he would claim his strays, and the right of every man to pass on the same was granted. The brand governed ownership, from which there was no appeal.

The round-up numbered hundreds of Texans. From the moment of reaching the meeting-points. Jack Sargent and Joe Manly began seeking out old friends. In cattle countries the Texan transplants readily, clannish to the core, noticeable by his saddle poise, accuracy of eye, and the ease with which he does his work. All those from the Beaver, including the boys, were marked by their manners, of fair play, a willingness to lend a hand, which won them friends from the first hour. During the initial day’s work, at a captain’s request. Bob Downs roped and tied steers, to examine the brands, as willingly as he would have answered civil questions. Manly was asked to referee a number of brands, and no one questioned his decisions.

Allowing one for detail duty, two —Y men were in the thick of every round-up. It mattered not how a cow passed, the trained eye caught the brand, and whether it was one in a thousand, or more, the men claimed their own. The first day was gratefully disappointing, not a stray from the Beaver being found, with only seven head of alien cattle gathered. The day’s work was too far to the eastward to catch any home drift, and few were to be expected until the main round-up reached the big bend of the Arkansas River, below the old trail market of Dodge City.

The beginning of work on the western division was advanced a day. The quarantine grounds at Trail City were covered with cattle; through herds were expected soon, and an isolated range must be granted to trail cattle, direct from Texas. A local round-up, over the line in Colorado, in advance of beginning the work in Kansas, met the requirements. Twenty-five miles of the valley was covered in an immense circle, making four big round-ups, and at evening the Kansas cowmen crossed the line with over two thousand cattle.

Every stock association, to the north and northwest, had inspectors in each division. Even the Texas Panhandle was represented on the western end, not that cattle would drift north, but trail herds often carried stock astray, and the calling of the rustler was a reality. Sargent took the Texas inspector under his wing, made him welcome at his wagon, loaned him horses, and to outsiders, the range expert from the Panhandle passed as a — Y man. He was a quiet fellow, attracted no attention, yet with an eye and memory for brands which fully qualified him for the task.

The western division moved down the river like companies of cavalry. The eastern one marched up the same stream, each crossing the river as occasion required, and on the afternoon of the 31st, well above Dodge City, the details working on the outside circle, moving in advance, hailed each other. That night the divisions camped like opposing armies, and in the morning the two cuts of strays gathered were thrown together, numbering over seven thousand, and a general reassortment began. All cattle belonging on the Arkansas River or to the south would be cut out and sent to their ranges, as the next move was north to the Smoky River. The work required a full half-day. A dozen disputes arose over ownership, the captains laboring honestly to mete out justice, but the leaven of human greed, if not common theft, was present.

Cattle rustlers dreaded a round-up. It bared their work to an open inspection, and some one must answer, either in person or by proxy. A rustler might do his work by night, but the light of day formed the working hours of the round-up.

‘What do you claim that beef on?’ inquired the Panhandle inspector, whose name was Vance, of a man in the eastern division.

‘He’s a “Crescent eight” beef,’ loftily answered the one addressed. ‘Belongs to an old friend of mine in the Indian Nation.’

‘Have you authority to gather the brand?’ inquired Vance.

‘Worked for him once; don’t need any authority.’

‘You ought to carry a power of attorney,’ insisted the inspector.

‘Who says so?’ sneeringly inquired the claimant.

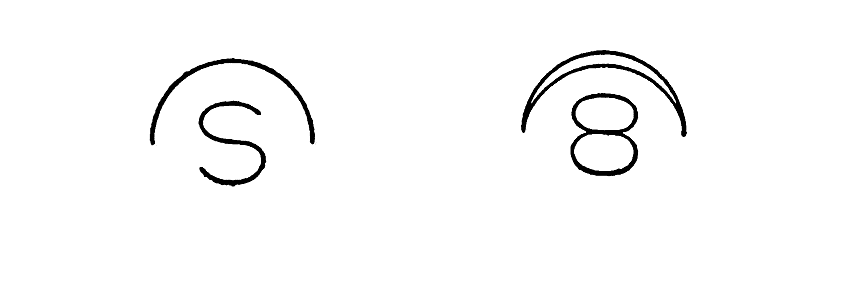

‘I’ll look at your authority and you may look at mine,’ answered Vance, shaking out a rope. ‘My claim is that the beef was once a “Half Circle S.” We’ll throw him and see. You may be right, and then again the brand may have been tampered with.’

‘You’ll throw no steer of mine,’ threateningly said the man.

‘Oh, yes, I will,’ replied Vance, smiling; ‘and what’s more. I’ll clip the brand. If he’s your beef, I want you to have him.’

Without a further word, the inspector cut out the beef, an immense animal, caught him by the horns the first throw, while Hamlet heeled him, the dexterity of their work calling for applause. The big fellow was eased to the ground, hog-tied, when Vance dismounted, unearthed a clipper, and bared the brand until he who cared might read. That the original brand had been tampered with, altering the letter ‘S’ into the figure ‘8,’ and changing a half-circle with an upper, outside curve, into a crescent, was too crude to pass inspection. .

‘I’ll take the beef,’ simply said Vance. ‘Turn him loose, Reil.’

In range parlance, it was the rustler’s move. ‘One moment,’ said he, pleading for time. ‘I’m not claiming that steer for myself, but for an old friend, a man I once worked for—’

‘You carry authority from your friend?’ questioned the captain of the eastern division.

‘There’s no occasion to. I’ll write him—’

‘The beef is yours, Mr. Vance,’ interrupted the captain.