a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Oh, Shoot! Confessions of an Agitated Sportsman Author: Rex Beach * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1800931h.html Language: English Date first posted: October 2018 Most recent update: October 2018 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Chapter 1. - Geese

Chapter 2. - The Chronicle of a Chromatic Bear Hunt

Chapter 3. - The San Blas People

Chapter 4. - On the Trail of the Cowardly Cougar

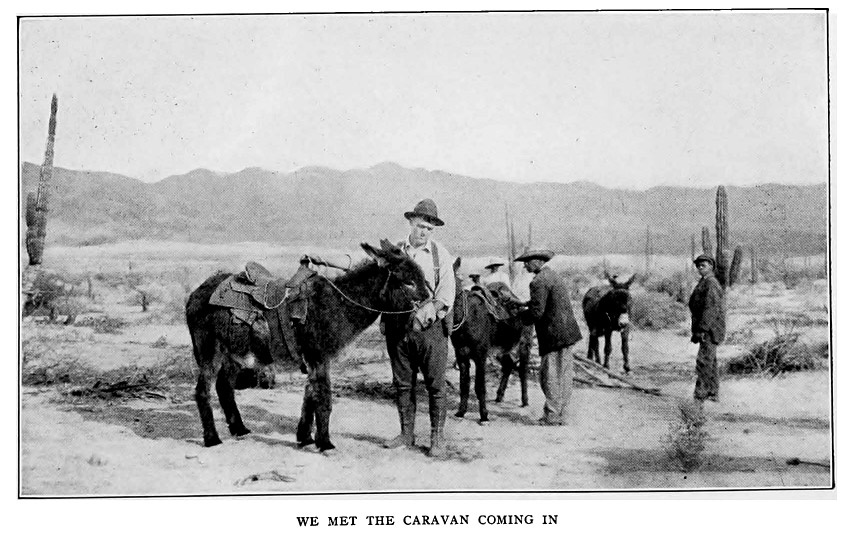

Chapter 5. - Messing Around in Mexico

Most men enjoy hunting, or would if they had a chance, but there is a small, abnormal minority who are hopeless addicts to the chase. To them the fiscal year begins with the opening of the deer season or the start of the duck flight, and ends when “birds and quadrupeds may no longer be legally possessed.” They are the fellows who wrap their own fish rods, join outing associations, and wear buckskin shirts when they disappear into the trackless wastes of Westchester County for the club’s annual potlatch and big-game lying contests.

To this class I belong. I offer what follows not as an excuse, but as a plea in extenuation. It is a feeble effort to paint the optimistic soul of a sportsman, to show how impossible it is to prevent him from having a good time, no matter how his luck breaks, and, in a general way, to answer the question, “Why is a hunter?”

There is no satisfactory answer to that query; hunters are merely born that way. Something in their blood manifests itself in regular accord with the signs of the zodiac. In my case, for instance, when autumn brings the open season, I suffer a complete and baffling change of disposition. I am no longer the splendid, upright citizen whose Christian virtues are a joy to his neighbors and an inspiration to the youth of his community. No. I grow furtive and restless; honest toil irks me. I begin to chase sparrows and point meadow larks and bark at rabbit tracks. I fall ill and manifest alarming symptoms which demand change of climate and surcease from the grinding routine. I sigh and complain. I moan in my sleep and my appetite flags. I allow myself to be discovered dejectedly fondling a favorite fowling piece or staring, with the drooping eyes of a Saint Bernard, at some moth-eaten example of taxidermic atrocity. The only book that stirs my languid soul is that thrilling work, Syllabus of the Fish and Game Regulations.

So adept have I become at simulating the signs of overwork that seldom am I denied a hunting trip to save my tottering health. Mind you, I do not advocate deceit. I abhor hypocrisy in the home, and I merely recount my own method of procedure for the benefit of such fellow huntsmen as are married and may be in need of first aid.

I was suffering the ravages of suppressed desires, common to my kind, when, several autumns ago, a friend told me about a form of wild-goose shooting in vogue on the outer shoals of Pamlico Sound, North Carolina, and utterly stampeded my processes of orderly thought.

“They use rolling blinds on the sand bars,” he told me. “They put down live decoys, a couple hundred yards away, then, when the geese come in, they roll the blind up to them.”

I assured him that his story was interesting but absurd. Having hunted Canada honkers, I knew them to be suspicious birds, skeptical of the plainest circumstantial evidence and possessed of all the distrust of an income-tax examiner.

“You don’t move while they’re looking,” my informant told me. “When they rubber, you hold your breath and, if religiously inclined, you pray. When they lower their heads, you push the blind forward. A goose is a poor judge of distance, and you can roll right up to him if you know how.”

I didn’t believe him; but the next day I was en route to North Carolina, and I have been back there every year since. I have shot from rolling blinds, stake blinds, and batteries. Sometimes I have good luck, again I do not. But nothing destroys my enjoyment, and every trip is a success. Once I am away with a gun on my arm, I become a nomad, a Siwash; I return home only when my sense of guilt becomes unbearable and when the warmth of my wife’s letters approaches zero.

And I have done well down there. At first, I went alone, traveled light, and spent little money. Now I take friends with me; I keep a well-equipped hunting boat there the year round; I stay a long time, and I spend sums vastly larger than I can afford. A brace of ducks used to cost me perhaps ten dollars, in the raw; now they stand me several times that, exclusive of general overhead. It shows what any persistent sportsman may accomplish even with a poor start. Perhaps no habitual hunter pays more for his entertainment than I do, and, figuring losses in business, time wasted, etc., etc., I truthfully can say that I enjoy the sport of kings.

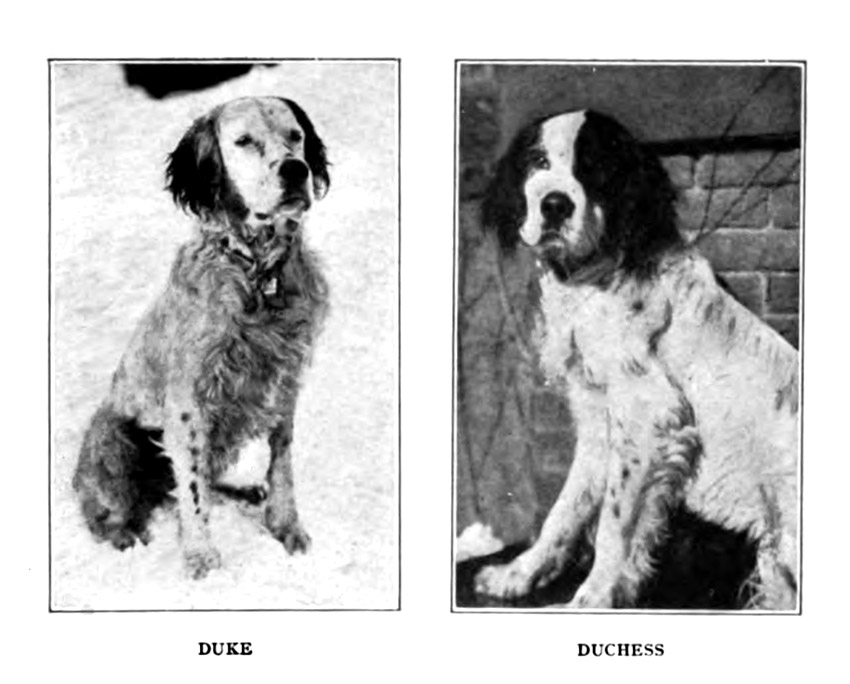

This year there were five of us in the party—Maximilian Foster and Grantland Rice, fellow scribes, and Duke and Duchess, two English setters of breeding that we took along to investigate the quail resources of the country.

Max had made the trip once before; so he needed no urging to go again—only an excuse. We hit upon a good one. He is an abandoned trout fisherman and he ties his own flies. Feathers are expensive and hard to get. Why not lay in a good supply? It was the best we could think of at short notice; so he went home to try it out.

There was every reason why Grant should remain at his desk, but we argued that there might well be problems of trajectory involved in goose shooting which would revolutionize the golf industry if thoughtfully studied. Who could better investigate this promising field than a recognized golf paranoiac like him? We had only to suggest this line of thought; Grant rose hungrily to the bait and darted with it into the uptown Subway. He argued where it would do the most good, and to such effect that he promised to follow us a week later.

Now, a word about Duke and Duchess. In my time I have owned many dogs, for a dog is something I lack the force of character to refuse. Anybody can give me any kind of dog at any time, and I am grateful—to the point of tears. That is how these two came to our house—as gift dogs—and they made me very happy for a while, because I had always wanted a pair of setters. Frankly, however, they abused their welcome, for there has seldom been merely a pair of them. I have presented setter puppies to my relatives and to my friends. I am now preparing a gift list of my business acquaintances and fellow club members, but I am slowly losing ground, and my place grows more and more to resemble a Bide-a-Wee Home.

I had never been able to hunt over this pair, for whenever I was ready for a trip, household duties prevented Duchess from going along, or else I foresaw the necessity of taking with me a large crate in which to ship back her excess profits. This time, however, conditions appeared to be propitious, so Max and I decided to do upland shooting while waiting for Grant to join us, and then wind up our hunt with a gigantic offensive against the ducks and geese. After watching Duke and Duchess point some of my pigeons and retrieve corncobs, Max and I decided they were natural game sleuths and could detect a bird in almost any disguise. If a quail hoped to escape them, it would have to wear hip boots and a beard.

Time was, not long ago, when travel was no great hardship. But all that is changed. Government operation of the railroads worked wonders, even during the brief time we had it. For instance, it restored all the thrill and suspense, all the old exciting uncertainty of travel during the Civil War wood-burning days. No longer does one encounter on the part of employees that un-American servility which made travel so popular with the parasitic rich. Real democracy prevails; train crews are rough, gruff, and unmannerly, and even the lowly porter has learned the sovereign dignity of labor—and maintains it. Nor is there now any difference in the accommodations on the jerkwater feeders and the main lines, all that having yielded to the glorious leveling process. Train schedules are ingeniously arranged for the benefit of innkeepers at junction points, and the last named are maintained for the purpose of allowing one train to escape before another can interfere with it.

Having missed connections wherever practical, and taken the dogs out for a walk in several towns of which we had never heard, Max and I arrived, in due course, at Beaufort, only twelve hours late. We were a bit weak from hunger and considerably bruised from futile attempts to battle our way into the dining car, but otherwise we were little the worse for the journey.

The guides were waiting with the boat, but they bore bad news.

“There’s plenty of geese on the banks,” Ri told us, “but we’ve had summer weather and the tides are so low there’s no shooting.”

Seldom does a hunter make a long trip and encounter weather or game conditions that are anything except unparalleled. I have learned long since to anticipate the announcement that all would have been well had I arrived three weeks earlier or had I postponed my coming for a similar length of time; therefore we ignored Ri’s evil tidings, pointed to Duke and Duchess, and forecast a bad week for any quail that were unwise enough to remain in the county.

Both Ri and Nathan are banks men, born and raised close to the Hatteras surf; they know nothing of quail hunting, so we blueprinted it for them on the way to the dock.

“High-schooled dogs like these are almost human,” we explained. “They are trained to pay no attention to anything except game birds, but, with respect to them, their intelligence is uncanny, their instinct unerring. They will quarter a field on the run, pick up the scent of a covey, wheel and work up wind to a point. When they come to a stand, you know you’ve got quail. You walk up, give them the word to flush; then they retrieve the dead birds and lay them at your feet without marring a feather. It’s beautiful work.”

While we were in the midst of this tribute, Duke, whose leash I had removed, squeezed out through the picket fence of a backyard with the palpitating remains of a white pullet in his mouth. He was proud; he was atremble with the ardor of the chase; the irate owner of the deceased fowl was at his heels, brandishing a hoe.

I settled with the outraged citizen; then I engaged Duke in a tug of war for the corpus delicti. It was a strictly fresh pullet; there was nothing cold storage about it, for it stretched. Meanwhile, Max explained how to break a dog of chicken-stealing.

“Tie the dead bird round his neck where he can’t get at it. That will cure him.”

“But why cure him?” Ri inquired, earnestly. “Seems like you’d ought to encourage a habit of that kind. Them dogs is worth money!”

Duke and Duchess were much interested in the boat. While we unpacked, they explored it from end to end; then Duchess went out on deck, tried to point a school of mullet, and fell overboard. Nathan retrieved her with a boat hook; she came streaming into the cabin, shook herself thoroughly over my open steamer trunk, then, unobserved, climbed into my berth and pulled the covers up around her chin. She has a long, silky, expensive coat, and it dries slowly; but she liked my bed and spent most of a restless night trying to blot herself upon my chest.

I did not sleep well. No one can enjoy unbroken repose so long as a wet dog insists upon sleeping inside the bosom of his pajamas. I arose at dawn with a hollow cough and all the premonitory symptoms of pneumonia, but Duchess appeared to be none the worse for her wetting, and we felt a great relief. It would have been a sad interruption to our outing had either dog fallen ill.

That day, while the boat was being outfitted, Max and I hired an automobile and went out to start a rolling barrage against the quail. The dogs were shivering with excitement when we put them into the first field, but they had nothing on us, for few thrills exceed that of the hunter who, after a year indoors, slips a pair of shells into his gun and says, “Let’s go.”

But within a half hour we knew we had pulled a flivver. Out of the entire state of North Carolina we had selected the one section where big, inch-long cockleburs were too thick for dogs to work. Nothing less than a patent-leather dachshund could have lived in those fields. In no time Duke and Duchess were burred up so solidly they could hardly move. They were bleeding; their spun-silk coats were matted and rolled until their skins were as tight as drum heads; their plumy tails were like baseball bats, and they weighed so much that their knees buckled and they looked as if they were about to jump.

They put up a covey or two, but it became a question either of removing their coats in solid blankets, as a whale is stripped of its blubber, or of patiently freeing them, one burr at a time—an all-day task—so we went back to the car and sought a snipe marsh.

Snipe marshes are wet, and the mud is usually deep, dark, and sticky. One either stands or sits in it, and to get the fullest enjoyment from the sport one should forget his rubber boots. This we had done; hence we were pretty squashy when we got back into the automobile about dark. We slowly froze on the way to town, but before we had hoarsed up too badly to speak, we agreed that it had been a great day.

I picked burrs most of that night. Along toward morning, however, I realized that it was a hopeless task. I had hair all over the cabin; my fingers were bleeding, Duke and Duchess were upon the verge of hysteria, and whenever we looked at each other we showed our teeth and growled. So I decided to clip them. But it is no part of a vacation to shear a pair of fretful canines, size six and seven-eighths, with a pair of dull manicure scissors. Breakfast found those dogs looking as if they had on tights. I was haggard, but grimly determined to enjoy another day in the glorious open if only I could stay awake.

It was no use trying to hunt here, however; so I gave the word to up anchor and hie away out of the cocklebur belt.

So far as I can discover, a boat owner has one privilege, expensive but gratifying; he can, when the spirit moves him, say, “Let us go away from here,” and sometimes the boat goes. I voiced that lordly order, ran Duchess out of my bed, and lay down for a nap. But not to sleep. Ri and Nathan began an intricate and noisy job of steam fitting in the engine room. Now and then the motor joined them, only to miss, cough, and die in their arms. By and by I heard echoes of profanity; so I arose to investigate the nature of the difficulty.

Max was frowning at the engine; Ri was massaging its forehead with a handful of waste; Nathan was spasmodically wrenching hisses out of it with the starting bar. He raised a streaming face to say:

“She never balked on us before,”

Ri agreed:

“She never missed an explosion coming over.”

“Sure you’ve got gas?” I hopefully inquired. This is my first question in cases of engine trouble.

They were sure; so I returned to my bunk and ran Duchess out of my warm place. Had they answered my inquiry in the negative, I could have instantly diagnosed the case, but when an engine has gasoline and still refuses to run, I delve no deeper. I respect its wishes.

Another half hour passed; then I went forward and asked if there was plenty of spark. This is my second question, and it leaves me clean. But there was spark enough, so I effaced myself once for all and again disturbed Duchess just as she had made an igloo of my bedclothes. This time I dozed off, lulled by sounds which indicated that Nathan has begun a major operation of some sort, with the others passing instruments and counting sponges.

Running footsteps roused me. Max was removing a fire extinguisher from its rack when I opened my eyes. He was calm; nothing to worry about except a small conflagration under the engine-room floor. If we worked fast, we might save a part of the ship, and wasn’t it fortunate that we were still tied up to the dock?

Contrary to expectations, we managed to put out the blaze, after which we found that all our motor needed was a cozy little fire in its living room to take the chill out of the air, for when we turned it over it went to work in the most cheerful spirit.

That afternoon we hunted farther up the sound, but what quail we raised were in impossible thickets and the snipe on the marshes had gone visiting over the week end. As we pulled out at daybreak on the following morning, we ran aground on a falling tide and stuck there.

Some trips seem to have a jinx on them. John W. Jonah appears to keep step right up to the finish. After laboring long and blasphemously in a vain effort to get afloat, the unwelcome suspicion entered our minds that this was such a one.

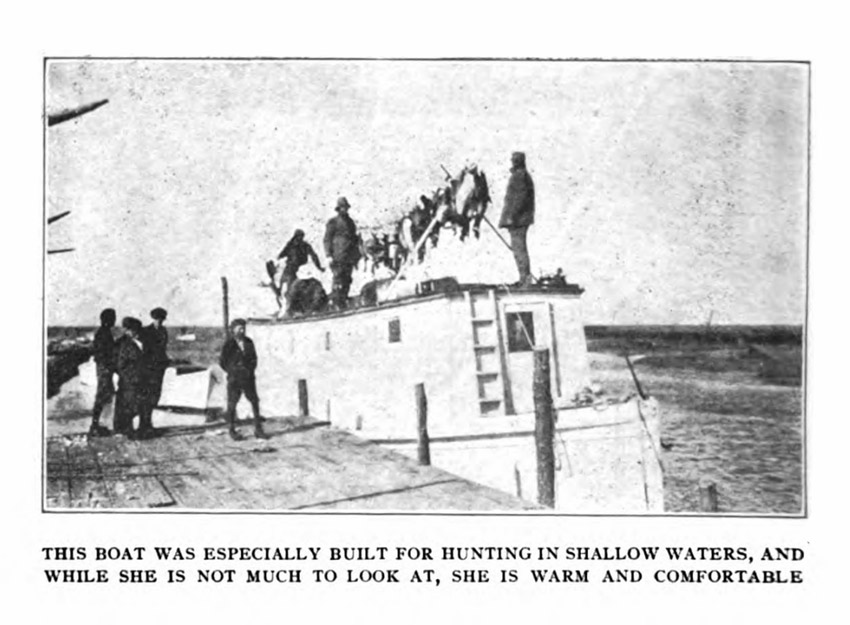

I had built this boat especially for hunting in these shallow waters, and while she is not much to look at, she is warm and comfortable, and it is Ri’s boast that she is the only fifty-foot craft in existence that can navigate on a heavy frost or a light dew. But that is an exaggeration, as we discovered when, finally, we were forced to go overboard, regardless of the weather, and boost her off by main strength. Then we learned that she had been cunningly designed to draw just enough water so as to thoroughly wet us, regardless of the height of our waders. But the experience benefited our colds; it did them a world of good and practically renewed their youth.

Max and I tested out the game resources of several sections of that shore on the way to Ocracoke, but instead of shipping quail home to our expectant friends, we had hard work to get enough to keep body and soul together, and those few, of course, we could neither taste nor smell—our colds were doing so well. Always there was some good reason why we had shot nothing today but had high hopes for the morrow; Duke and Duchess began to regard the whole expedition as a hoax on them, and spent their time collecting ticks for me to remove during the evening. Nevertheless, the open life was having its effect upon Max and me. We had arrived soft, pallid, gas-bleached, our bones afflicted with city-bred aches and pains; after a week spent on waist-deep sand bars, in damp marshes and draughty fields, we were practically bedridden.

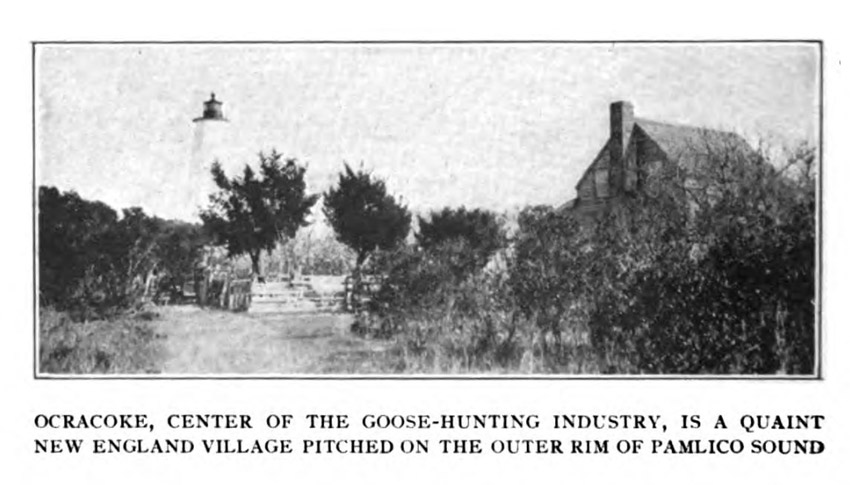

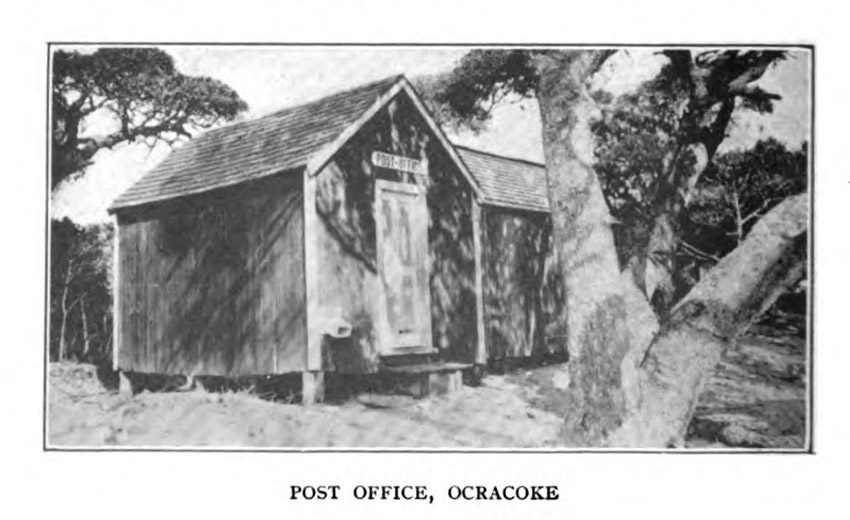

Ocracoke, center of the goose-hunting industry, is a quaint New England village pitched on the outer rim of Pamlico Sound, and it hovers around a tiny circular lagoon. The houses are scattered among wind-twisted cedars or thickets of juniper and sedge, and most of them possess two outstanding adjuncts—a private graveyard and a decoy pen. All male inhabitants above the age of nine are experts on internal-combustion engines, for motor boats are everywhere except in the back yards. Of distinctive landmarks there are four—one lighthouse, one colored man, and two Methodist churches. Ocracoke has tried other negroes, but likes this one, and as for religion, it will probably build another Methodist church when prices get back to normal.

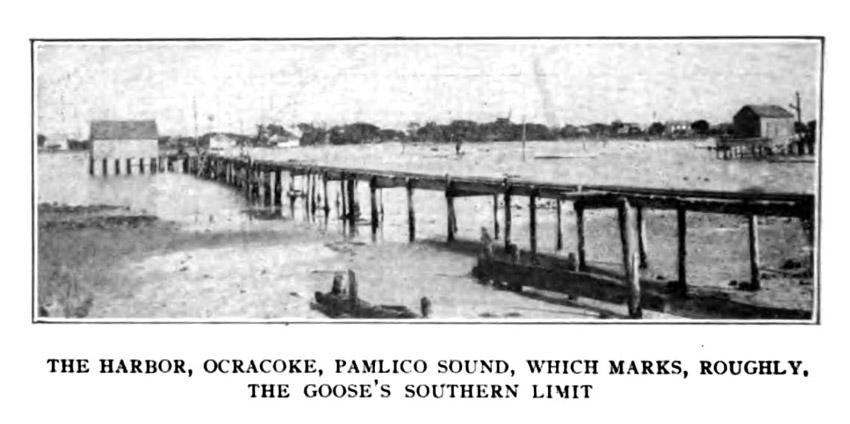

Now, for the benefit of any reader genuinely in quest of information, a word as to the kind of hunting here in vogue and the methods involved. First, understand that this stormy Hatteras region is the Palm Beach of the Canada goose and his little cousin the brant. Ducks winter all along the Atlantic coast, but Pamlico Sound marks, roughly, the goose’s southern limit. Here each wary old gander pilots his family; here he and his mate watch their young folks make social engagements for the following season.

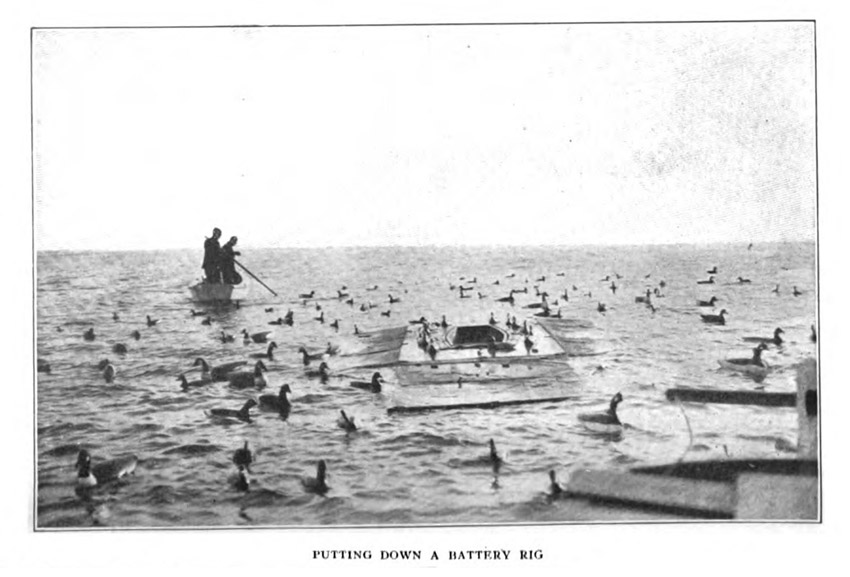

There is no marsh or pond shooting, for the wild fowl frequent the shallow waters of the sound and it is necessary to hunt from rolling blinds, stake blinds, or batteries. The rolling blind I have described—it is used only on cold, drizzly days in the late season when the geese have chilblains and gather on the dry bars to compare frost bites. A stake blind resembles a pulpit raised upon four posts, and is useful mainly in decoying inexperienced Northern hunters. Green sportsmen stool well to stake blinds, for they are comfortable, but a wise gunner shies at them as does a gander. He knows that the real thing is a battery.

This latter device may be described as a sort of coffin, but lacking in the creature comforts of a casket. It is a narrow, water-tight box with a flush deck about two feet wide, to three sides of which are hinged large folding wings of cloth or sacking stretched upon a light wooden framework. It is painted an inconspicuous color; heavy weights sink it so low that its decks are awash. The sportsman lies at full length in it, and his body is thus really beneath the level of the water. When it is surrounded by a couple hundred dancing decoys, the hunter is effectually hidden from all but high-flying birds. To such as fly low, the rig is a snare and a delusion; not unless they flare high enough to get a duck’s-eye view do they see the ace-in-the-hole, and then it is usually too late.

Battery shooting requires some little practice and experience. One must begin by learning to endure patiently the sensations of ossification, for to rest one’s aching frame even briefly by sitting up, or to so much as raise one’s head for a good look about, is a high crime and a misdemeanor. It completely ruins the whole day for the guides, who are comfortably anchored off to leeward in the tender, and affords them the opportunity of saying, later:

“You can’t expect ’em to decoy to a lump. If you’d of kep’ down, you’d of got fifty birds to-day.”

And that is not the only discomfort. All batteries are too small, and some of them leak in the small of the back. If the wind shifts or blows up, they sink before the guides arrive. For years I tried to adapt myself to the existing models, but failed. I fasted until my hips narrowed to an AA last; I wore the hair off the top of my head; my body became rectangular, and still I did not fit. I have had rubber-booted guides stand upon my abdomen and stamp me into my mold, as the barefoot maidens of Italy tread the autumn vintage, but, no matter how well they wedged me in, some part of me, sooner or later, slipped. The damp salt air swelled me, perhaps; anyhow, I bulged until from a distance I looked like a dead porpoise, and the ducks avoided me.

Tiring of this, I had a large box built. I equipped it with a rubber mattress and pillow, and now I shoot in Oriental luxury. But, even under favorable conditions, to correctly time incoming birds, to rise up and “meet them” at precisely the right instant, is a matter of considerable nicety. One must shoot sitting, which is a trick in itself, especially on the back hand, and ducks do not remain stationary when surprised by the apparition of a magnified jack-in-the-box. They are reputed to travel at ninety miles an hour, when hitting on all four, but that is too conservative. Start the goose flesh on a teal’s neck, for instance, and he will leave your vicinity so fast that a load of shot needs short pants and running shoes to overtake him.

I have lain in a double box alongside of experienced field shots and picked up many valuable additions to my vocabulary of epithets. I have seen nice, well-bred, Christian gentlemen grind their teeth, throw their shells overboard, and send for better loads, even smash their guns in profane and impotent rage. That is, I have seen them perform thus when I myself was not stone blind with fury.

We shot for a couple of days, off Ocracoke, while we were waiting for Grant, but the weather was warm and we had little luck; then the bottom fell out of the glass and, in high hopes of a norther, we ran up the banks to our favorite hunting grounds. As we pulled into our anchorage, the bars were black with wild fowl; through our field glasses we could see thousands, tens of thousands, of resting geese; up toward Hatteras Inlet the sky was smudged with smoky streamers which we knew to be wheeling clouds of redheads. Before we had been at rest a half hour, the wind hauled and came whooping out of the north, bearing a cold, driving rain; so we shook hands all around. All that is necessary for good shooting on Pamlico is bad weather. It looked as if we had buried our jinx once for all.

Our party had grown, for we had picked up the hunting rigs at Ocracoke—they were moored astern of us, launches, battery boats, and decoy skiffs streaming out like the tail of a comet. All that day and the next we watched low-flying strings of geese and ragged flocks of ducks beating past us, while we told stories or conducted simple experiments in probability and chance. In the latter I was unsuccessful, as usual, for I simply cannot become accustomed to the high cost of two small pair.

The second morning brought a slight betterment of conditions; so we set out early, Max in search of shelter behind a marshy islet, while I hit for the outer reefs. After several attempts, Ri finally found a spot where a mile of shoals had flattened the sea sufficiently to promise some hope of “getting down.”

While we were placing the battery, Grantland Rice arrived in a small boat from Ocracoke. He was drenched; he had been four days en route from New York, and he was about fed up on rough travel. Through numb, blue lips he chattered, “You’re harder to find than Stanley.”

I directed him to the houseboat and told him where to obtain comfort and warmth— third bureau drawer, left-hand corner, but be sure to cork it up when through—then explained that Max had put down a double box and was waiting for him.

“The weather to kill geese is weather to kill men,” I assured him. “You’re in luck to arrive during a norther like this.”

“Any nursing facilities aboard the boat?” Grant wanted to know.

I assured him with pride that we were equipped to take care of almost anything up to double pneumonia, and that if worse came to worst and his lungs filled up, we could run him over to the mainland, where he could probably get in touch with a hospital by mail.

My battery managed to live, with the lead wash strips turned up, but the gale drove foam and spray over me in such quantities that I was soon numb and wet—the normal state for a battery hunter. Members of the Greely expedition doubtless suffered some discomforts, and the retreat from Serbia must have been trying, but for 100-per-cent-perfect exposure give me a battery in stormy winter weather.

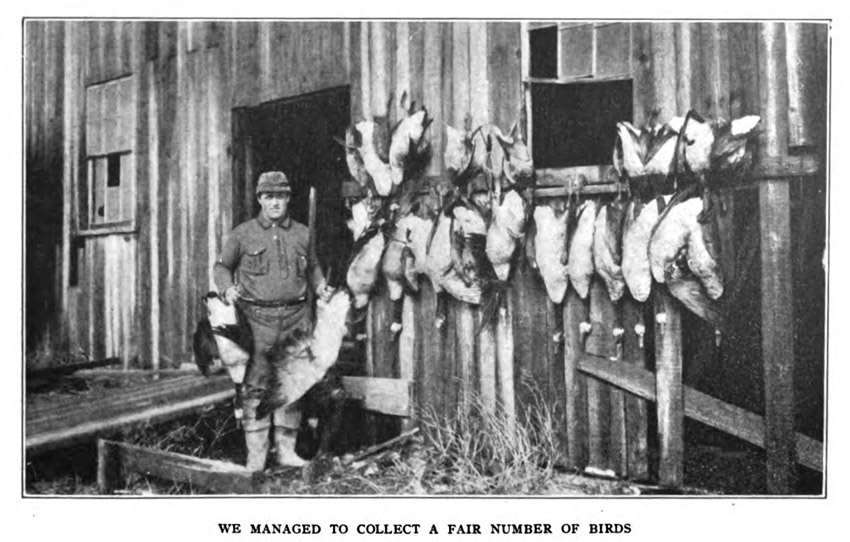

However, I managed to collect a fair number of birds before dusk, when, in answer to my feeble signals, the guides rescued me. They seized me by my brittle ears, raised me stiffly to my heels, then slid me, head first, into the tiny cabin of the launch, as stokers shove cordwood into a boiler. By the time we got back to the boat I could bend my larger joints slightly and I no longer gave off a metallic sound when things fell on me.

The other boys had not fared so well. They had been drowned out, their battery had been sunk without trace, and they had nothing to show for their day’s sport except a clothes line full of steaming garments and a nice pair of congestive chills. Otherwise it had been a great day, and we looked forward to more fun on the morrow.

But how vain our hopes! As usual, the weather was unparalleled. Once again it surprised the oldest inhabitants. That night the wind whipped into the south, drove all the water off the bars, then fell away to a calm, and the temperature became oppressive. The wild fowl reassembled in great rafts where we could not get at them; we lay in our batteries, panting like lizards and moaning for iced lemonade, while the skin on our noses curled up like dried paint. The only birds we got were poor half-witted things, delirious with the heat.

Such conditions could not last—the guides assured us of that—and they didn’t. The next day it rained, and a battery in rainy weather is about as dry as a goldfish globe. Now, a strong man with an iron will may school himself to lie motionless while he slowly perishes from cold, for after the first few agonizing hours there is comparatively little discomfort to death by freezing, but I defy anybody to drown without a struggle.

But why drag out the painful details? We had not interred our jinx. One day a hurricane blew out of the north and piled the angry waters in upon us, the next it shifted, ran the tides out, and left us as dry as a lime burner’s boot; the third it rained or fogged or turned glassy calm. Grizzled old veterans from the Hatteras Life-saving Station rowed out to tell us that such weather was impossible and threatened to ruin their business, but what could you expect under a Democratic administration?

One morning, Ri outlined a desperate plan to me, and I leaped at it. Away inshore, across miles of flats, we could see probably a million geese and twice that many ducks enjoying a shallow footbath where no boat could approach them.

“Let’s leave the launch outside, wade our rig up to their feedin’ ground, and dig it in. It ‘ll take a half day of hard work, but there’s goin’ to be a loose goose flyin’ about three o’clock, and you can shoot till plumb dark. We’ll leave the box down and wade back.”

It sounded difficult, so we tried it, towing the empty battery behind us. The big decoy skiff dragged like an alligator, but we poled, waded, shoved, and tugged until we came to where the bottom was pitted and white with uptorn grass roots. Here we dug a hole deep enough to sink the box—no easy job with a broken-handled shovel—put out our stools, and then the men shoved the empty boat away.

Tons of wild fowl had gone out as we came in, but soon after I lay down they began returning. First there came a pair of sprigs, then a pair of black ducks. The black mallard is my favorite—he is so wary, so wise, and so game. He can look into the neck of a jug, and he fights to the last. When the hen dropped, the drake, as usual, flared vertically. Upward he leaped in that exhibition of furious aerial gymnastics peculiar to his breed; then, at the top of his climb, he seemed to hang motionless for the briefest interval. That is the psychological instant at which to nail a black duck. As he came down, fighting, I was up and overboard after him. The water was shallow, but I splashed like a sternwheeler, and I was wet to the waist before I had retrieved that cripple.

Next I glimpsed a long, low line of waving wings approaching, and flattened myself to the thickness of a flannel cake, thrilling in every nerve. Never did twenty geese head in more prettily. They had started to set their pinions, and I was picking my shots, when one of the decoys, a young gander in the Boy Scout class, cracked under the nervous strain and began to flap madly. He flared the incomers, and I failed to get more than two.

I made haste to gather up the dead birds and lay them on the battery wings; then I moved the shell-shocked gander to the head of the rig. But before I could get him anchored, distant honks warned me, and I ran for cover. Of course, I tripped over decoy lines—everybody does. I did Miss Kellerman’s famous standing, sitting, standing dive, but there was still a dry spot between my shoulder blades when I plunged kicking into the battery. I was too late, however, and the flock went by, out of range, laughing uproariously at me.

Then up from the south came a rain squall, and I stood with my back to it, shivering and talking loudly as tiny glacial streams explored parts of my body that are not accustomed to water. During the rest of the afternoon, cloudbursts followed one another with such regularity that my battery resembled a horse trough, and when I immersed myself in it it overflowed. But between squalls the birds flew. When a bunch of geese pitched in at my head and I downed five, I fell in love with the spot and would have resisted a writ of eviction.

When the guides appeared at dark I had a pile of game that all but filled the tiny skiff which they had thoughtfully brought along. By the time we had loaded it with the dead birds and the crate of live decoys it was gunwale deep, so we set out to wade back to the launch, towing it behind us.

Night had fallen; fog and rain occasionally obscured the gleam of our distant ship’s lantern. Other lights winked at us out of the gloom, and although they were miles away, nevertheless they all looked alike; so, naturally, we got lost. We headed for first one then another twinkling beacon, and altered our course only when the water deepened so that we could proceed no farther without swimming.

I have been successfully lost where you would least expect it, but never before had I been lost at sea with nothing whatever to sit down upon except the ocean, and after an hour or two I voted it the last word in nothing to do. I can think of no poorer way of spending a rainy December night than chasing will-o’-the-wisps round a knee-deep mud flat the size of Texas, with an open channel between you and the shore.

I presume we waded no more than twenty-five miles—although it seemed much farther —before we found the launch and collapsed over her gunwale like three wet shirts. Then, just to show that things are never as bad as possible, the engine balked.

I asked if there was plenty of gas and if the spark was working, and, receiving the usual affirmative answer, I dissolved completely into my rubber boots. Ri was probably quite as miserable as I, but he began to scrub up for the customary operation. He removed the motor’s appendix, or its Fay and Bowen, and ran a straw through it, the while we could see frantic flashes of the houseboat’s headlight.

I felt an aching pity for Max and Grant. What a shock to them it would be to find us in the morning, frozen over the disemboweled remains of our engine, like merrymakers stricken at a feast of toadstools. They were men of fine feelings; it would nearly, if not quite, spoil their whole trip, even though they divided my dead birds between them.

But the machine made a miraculous recovery, and at its first encouraging “put” a great warmth of satisfaction stole through me. After all, it had been a wonderful day.

Human endurance, however, could not out-game that weather. The evening finally came when the boys announced that their time was up, so, after supper, we sent the small boats up to Ocracoke on the inside and fared forth into the dark sound.

As we blindly felt our way out from our anchorage, we ran over a stake net, picked it up and wrapped it around our propeller, and grounded helplessly on the edge of the outer bar. There we stuck. Examination showed a very pretty state of affairs. The net with its hard cotton lead line had wedged in between the propeller and the hull, and disconnected the shaft—a trifling damage and one that could have been repaired easily enough had we possessed a deep-sea diving outfit or a floating dry dock. But, search our baggage as we might, we could find neither. That’s the trouble about leaving home in a hurry, one is apt to forget his dry dock.

Just to show us that he was still on the job, old J. W. Jinx arranged a shift in the wind. It had been calm all day; now a gale came off the sound and held us firmly on the reef. Pamlico began to show her teeth in the gloom, and with every swell we worked higher up on the bar and the boat bumped until our teeth rattled. We were several miles offshore, without any sort of skiff; it began to look as if we had about run out of luck and might have to hunt standing room somewhere in the surf. However, a yacht had made in near by on the day before, and, thanks to our searchlight, we managed to get a rise out of her. She sent a launch off, and it finally towed us back to shelter.

By this time it was midnight and the duties of host rested heavily upon me. I could with difficulty meet the accusing eyes of my guests, and, although I had exhausted my conversational powers, I hung close to them for fear of the cutting, unkind things they would say if I left them alone.

The next morning, Mr. Scott, owner of the neighboring yacht, prompted by true sportsman’s courtesy, towed us back to Ocracoke, and as we went plunging down the sound in a cloud of spray we realized that the weather had hardened up and the birds were beginning to fly. The sky was full of them; we could hear the noise of many guns—a sound that brought scalding tears to our eyes.

I simply could not bear to leave just as the show had begun; so I reread my wife’s last letter, and, finding it only moderately cool, I took the bit in my teeth and declared it my intention to stick long enough to change defeat into victory, even if I had to sleep in the woodshed when I got home.

“Better stay on for a few days,” I urged the boys. “It will be dangerous to sit up in a battery to-morrow; the birds will knock your hats off. A blind man could kill his limit in this weather.”

I had not read their mail, but I understood when they choked up and spoke tearfully about “business.” While I pitied them sincerely, a fierce joy surged through my own veins; nothing now could hinder me from enjoying a few days of fast, furious shooting. The birds were pouring out of Currituck; there would be redheads, canvasbacks, teal— every kind of duck.

As we tried to work the house boat into the lagoon at Ocracoke, where we could get her out on the ways and count the fish remaining in that fragment of net, an Arctic tornado hit us and blew us up high and dry on a rock pile. It was a frightful position we now found ourselves in, for we had such a list to port that the chips rolled off the table—and we all felt lucky.

But the storm had delayed the mail boat and my companions were forced to remain over another day. The courage with which they bore this bitter disappointment was sublime; they sang like a pair of thrushes as they feverishly unpacked.

Conditions were ideal the next morning and we were away early. Having put down my rig in shallow water, where I could wade up my own birds, I sent the launch back to the village. This promised to be a day of days, and I wanted to get the most out of it.

Almost immediately the ducks began flying, and several bunches headed in towards me. I was puzzled as to why they changed their minds and flared, until a cautious peep over the side showed a small power-boat threshing up against the wind. It had already cost me several good shots, but there was nothing to do except wait patiently for it to pass. However, it did not pass; in spite of my angry shouts and gesticulations it held its course until within hailing distance. Then the man in the stern bellowed:

“Telegram!”

Now, mail is bad enough on a hunting trip, but telegrams are unbearable, and I distrust them. Nobody ever wanted me to stay away and enjoy myself so urgently as to wire me; therefore I openly resented this man and his mission. By the time he had handed me the message I had made up my mind to ignore it, reasoning rapidly that it could by no possibility be of importance, and if it were—as it probably was—I could do nothing about it before the mail boat came that night. Hence it was futile to permit my attention to be distracted from the important business of the moment.

I thanked the man, then urged him, for Heaven’s sake, to beat it quickly, for, in the offing, flocks of geese were noisily demanding a chance to sit down with my decoys, and just out of range ducks were flying about, first on one wing then on the other, waiting for him to be gone.

But that telegram exercised an uncanny fascination for me. I lacked the moral courage to destroy it, although I knew full well if I kept it on my person I would read it—and regret so doing. Things worked out just as I had expected. I yielded and—my worst apprehensions were realized. The message was from my wife, but beyond that fact there was nothing in its favor, for it read:

Your secretary has forged a number of your checks and disappeared. Total amount unknown, as checks are still coming in. Presume you gave him keys to wine cellar, for they, too, are missing. Wire instructions quick. Am ill, but stay, have a good time, and don’t worry.

I stared, numb and horror-stricken at the sheet until I was roused by a mighty whir of rushing pinions. Those ducks had stood it as long as possible and were decoying to me, sitting up. Through force of habit my palsied fingers clutched at my gun, but, although the birds were back-pedaling almost within reach, I scored five misses. Who can shoot straight with amount of loss unknown and certain precincts unheard from? Not I. Those broadbills looked like fluttering bank books.

And the keys to the wine cellar missing! That precious private stock, laid in for purely medicinal purposes, ravaged, kidnaped! A hoarse shout burst from my throat; I leaped to my feet and waved frantically at the departing boatsman, but he mistook my cries of anguish for jubilation at the results of my broadside, waved me good luck, and continued on his way.

As I stood there striving to make my distress heard by that vanishing messenger, geese, brant, ducks, and other shy feathered creatures of the wild poured out of the sky and tried to alight upon me, or so it seemed. They came in clouds and I shooed them off like mosquitoes. One would have thought it was the nesting season, and I was an egg.

I read again that hideous message as I undertook to reload, but I trembled the trigger off and barely missed destroying my left foot—my favorite. Never in the annals of battery shooting has there been another day like that. Those ducks reorganized and launched attack after attack upon me, but my nerve was gone, and the most I could do was defend myself blindly.

I did spill blood during one assault, and I was encouraged until I found that I had shot one of Ri’s live decoys. Beyond that, the casualties were negligible, and when the guides came to pick me up they had to beat the blackheads out of the decoys with an oar.

As we pulled out of Ocracoke at dawn the next morning, the town was full of dead birds, and visiting sportsmen with eager, feverish eyes were setting forth once more for the gunning grounds. But we hated them. Flocks of geese decoyed to the mail boat whenever it hove to or broke down, and we hated them also.

Upon my arrival home I found a wire from Ri reading:

Too bad you left. Nathan killed fifty birds the next day and he can’t hit a bull with a spade.

However, take it by and large, it was a fine trip and a good time was had by all, which proves what I set out to demonstrate in the beginning—viz., you can’t explain a hunter; you can only bear with him and allow nature to take its course.

The biography of the average big-game hunter is a bitter hard-luck story. As compared with his work, the twelve labors of Hercules were the initiatory stunts of a high-school sorority. If this were not so, we would have no game left. The “big-horn” and the Alaskan grizzly would soon be quite as extinct as the dodo.

When Fred Stone and I determined to go bear hunting we chose Alaska, for several reasons. First, it was farther away than any other place we knew of, and harder to get to than certain suburbs of Brooklyn. Secondly, there are lots of bears in Alaska—black, white, gray, blue, brown, and the combinations thereof; enough to match any kind of furniture or shade of carpet. And I had been kindly but firmly informed that my trip would not be considered a success at our house unless I brought back a mahogany-brown skin, shading to orange, for the living room, and a large pelt not too deeply tinged with ox-heart red, to match the dining room rug. Fred was told likewise that the boss of his bungalow would welcome bear rugs of a French-gray or moss-green tint only.

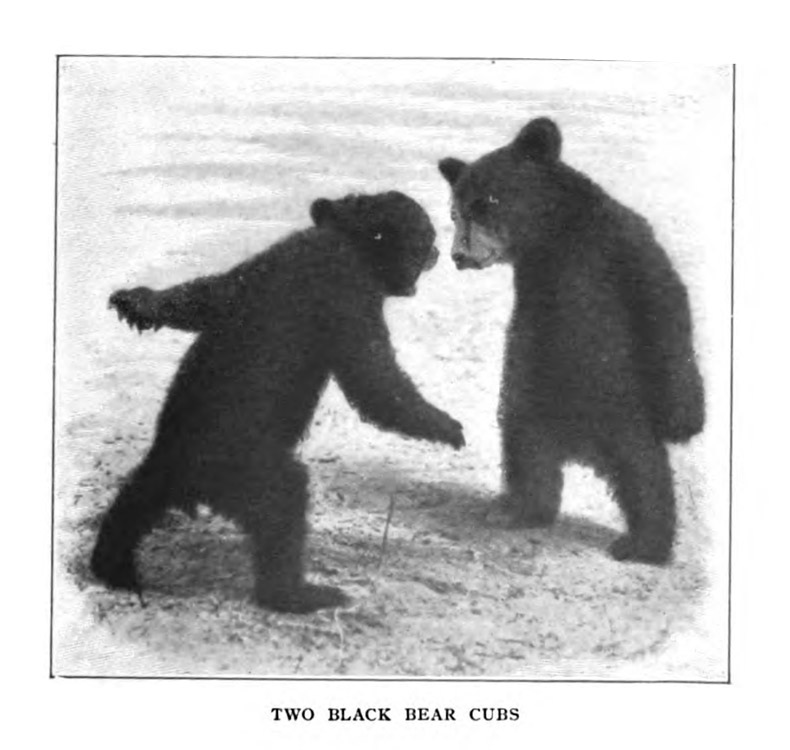

We began to hunt immediately upon leaving New York, and had secured some fine specimens before reaching Chicago, but we killed most of our bears between St. Paul and Billings, Montana.

It was while dashing through the Bad Lands that Fred suggested bear dogs. “Great!” said I. “They’ll save us a lot of work and be fine company in camp.” Accordingly, we wired ahead for “Best pair bear dogs state of Washington,” and a few hours after our arrival at Seattle they came by express. They were a well-matched pair, yclept Jack and Jill, so the letter stated; both were wise in their generation and schooled in the ways of bear.

“They are a trifle fat,” we read, “but they will be O. K. if you cut down their rations. Both are fine cold trailers. Kindly remit hundred dollars and feed only at night.” We were informed that in Jill’s veins coursed the best blue blood of Virginia, and that, although she was no puppy in point of years, her age and experience were assets impossible to estimate. This rendered me a bit doubtful, for Alaska is not a land for fat old ladies, but Fred destroyed my misgivings by saying:

“Take it from me, she’s all right. We don’t want any debutante dogs on this trip.”

Jack was more my ideal. He had the ears of a bloodhound, the face of a mastiff, and the tail of a kangaroo, while his eyes were those of a tragedian, deep, soulful, and dark with romance. When he gave tongue, we decided he must have studied under Edouard de Reszke.

One day in Seattle sufficed to augment our outfit with ammunition, fishing tackle, and a mosquito tent. I have long since learned not to carry grub into the north.

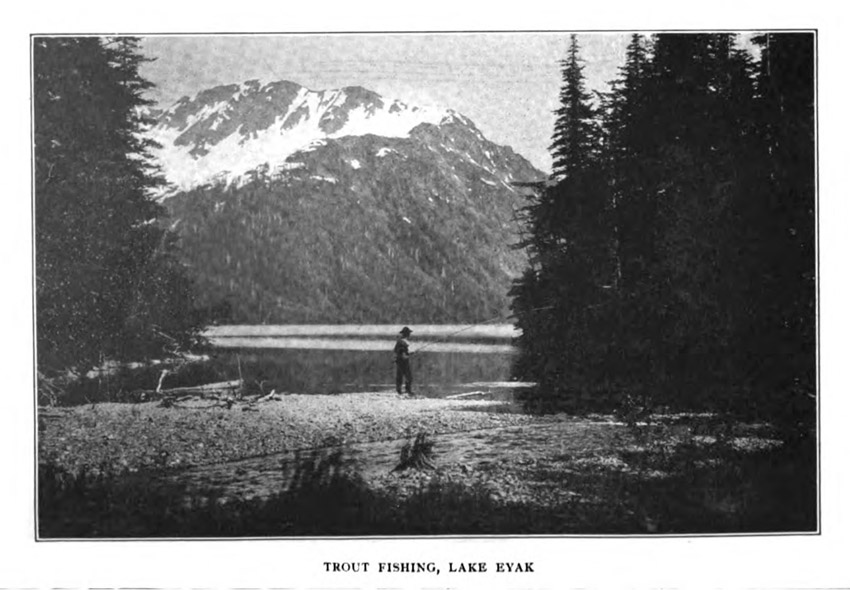

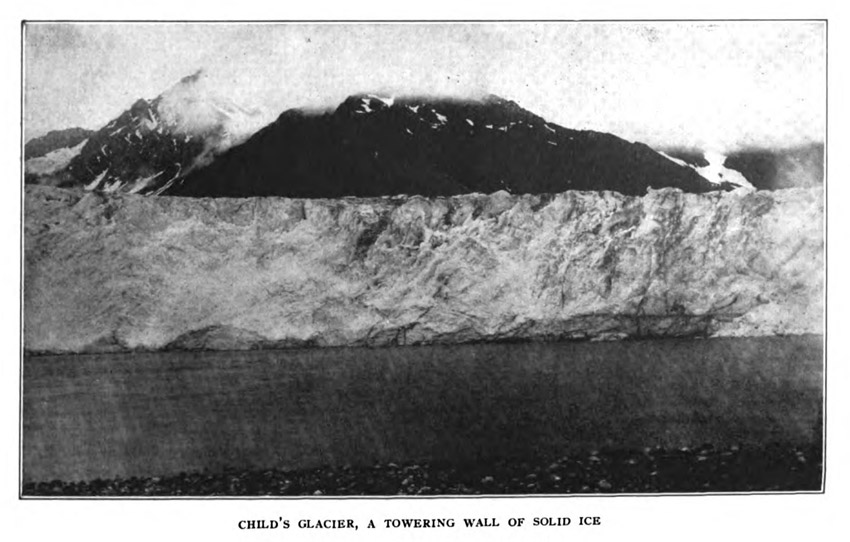

Two years before, at the height of the salmon season, I had made a trip through the Copper River delta in a wheezy, smelly fish boat, and while tidebound, with the north Pacific pounding on the sand dunes to seaward, I had gazed across thirty miles of flats up into a gap of the great Alaskan range towards long, low-lying streaks of white which slanted down out of hidden gulches on opposite sides of the valley, appearing to close the course of the river.

“Glaciers!” announced the smelly captain of the smelly fish boat.

“Live glaciers?” I queried.

“Sure! On still days you can hear them ‘working’ clear out here. Chunks drop off the size of a mountain, and splash out all the water in the river. There ’ain’t any white men ever been up there.”

I spoke later with the smelly engineer, who was an old-timer in the country.

“They come together, they do, buttin’ one another like a pair of rams, grindin’ and squeezin’ to beat the band.”

“But how does the river get through?” I demanded, skeptically.

“I don’t know. Maybe it jumps over.”

The smelly deck hand shed even a dimmer light on that mysterious valley by informing me that, in order to pass those glaciers, one had to work along a perpendicular face of ice, chipping footholds and clinging with fingers and toes to dizzy heights above the river.

My informants united on but one statement: there were a great many bears up near those glaciers, for it seemed there were rapids of some sort where the animals came to fish during the salmon time; so many of them, in fact, that the banks were seamed with trails and the rocks worn smooth by their feet.

I still had some eight thousand Alaskan miles to do that summer, so I could stay there no longer, but the determination to see those glaciers at close range and to examine those bear tracks had grown upon me steadily. I had told Fred of them, and it was thither we were heading now. Hence the mosquito tents, the ammunition, and the soulful bear dogs.

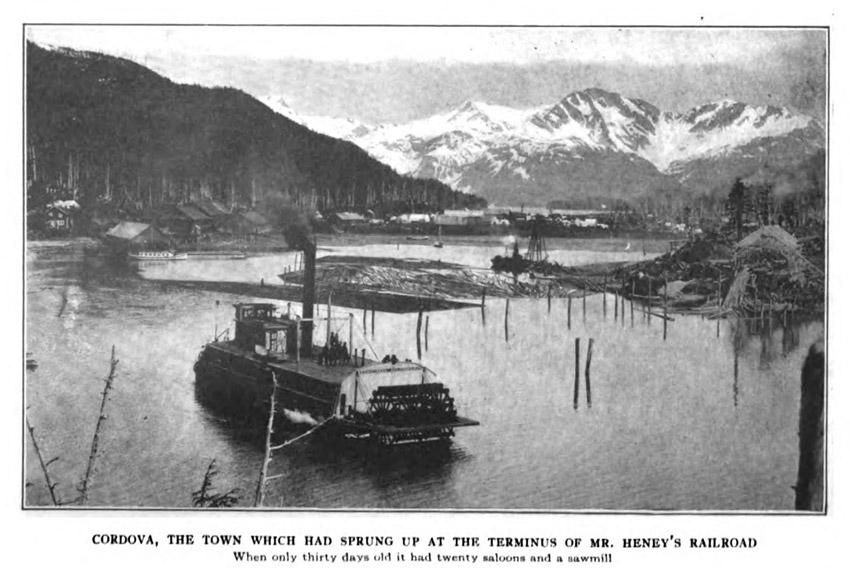

For five days we plowed northward on a typical ratty Alaskan steamer, a thing of creaks and odors and vermin. On a drizzly May morning we docked at Cordova, the town which had sprung up at the terminus of Mr. Heney’s railroad. The road was not really Mr. Heney’s, but belonged to the Morgan-Guggenheim interests, being destined to haul copper from their mines two hundred miles inland. Mr. Heney was building it for them, however, and everybody looked upon it as his personal property. It was hours before breakfast time when we arrived, but “M. J.” himself was at the dock, for a purser on one of his freight steamers had apparently mislaid a locomotive or a steam shovel or some such article which Mr. Heney wished to use that morning, and he had come down to find it. He was not annoyed—it takes something more than a lost, strayed, or stolen locomotive to annoy a man who builds railroads for fun rather than for money and chooses a new country in which to do it because it offers unusual obstacles.

He welcomed us, drippingly, with a smile of Irish descent which no humidity nor stress of fortune could affect.

“I’m sorry you didn’t arrive yesterday,” he said, “for it looks as if the fall rains had set in.” It was the 21st of May and this was no joke, for Cordova is known as the wettest place in the world.

“Bear?” said Mr. Heney. “Yes, indeed. We’ll see that you get all you want.” And from that moment until we left Alaska with our legal limit of pelts he made us feel that the labors of his fifteen hundred men, the building of his railroad, and the disbursement of millions of dollars were, as compared with our comfort and our enjoyment, affairs of secondary importance. And when we described to him the tints of our wall paper and rugs we got the impression that, whether we needed bears lavender, bears mauve, or bears cerise, it was thenceforth a religion with him to see that we found them.

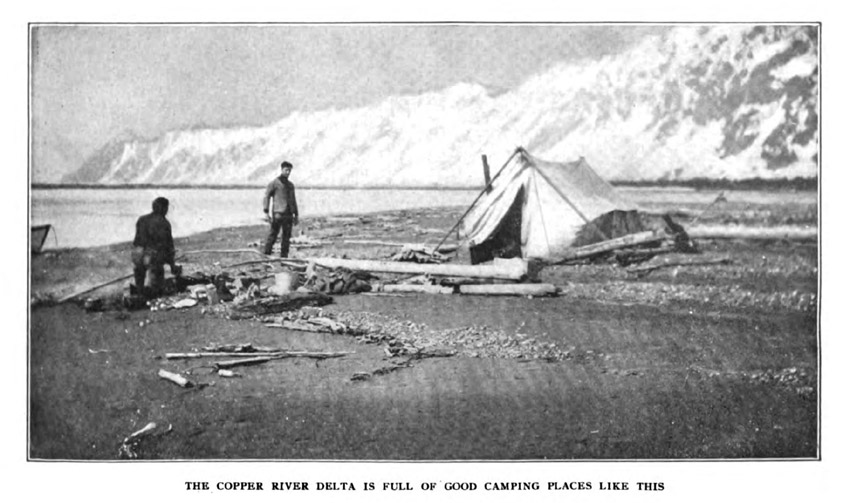

As to guides, there were no regular guides in this neighborhood, since there were no tourists—every resident had to earn his money honestly. But there were fellows about who knew the woods—Joe Ibach, for instance. He had just come in from a prospecting trip and might care to go a-bear hunting. So we descended upon Joe. Certainly he’d go. He didn’t care to guide, however, as he had never “gid” any, but he’d show us a lot of bears, and carry the outfit, and row the boat, and do the cooking, and chop the wood, and build the fires, and perform the other labors of the camp. As for regular guiding, though, he guessed we’d have to see to that ourselves until he learned how. When we spoke about wages, he said he didn’t think that sort of thing was worth money, showing conclusively that he was not a real guide. He had a long, square jaw and a steady eye, which looked good to us, so we agreed to do the guiding if he would do the rest of the things he had mentioned—and see that we did not get lost. As to those mysterious glaciers towards which I had been working these two years, Mr. Heney said we could not reach them yet. The Copper River delta was full of rotten ice, and the banks were so choked with snow that it was impossible to take an outfit up before the slews cleared. Out at Camp Six, however, a number of bears had been seen, one in particular so large that no day laborer could look upon his tracks and retain a sense of direction. Only the section bosses could stand their ground after one glance at his spoor.

We were installed at Camp Six by 5.30 on the following afternoon and had unchained our dogs. At 5.49 Jack had found a porcupine. A man came running to inform us that he was “all quilled up,” and so he was; his nose, lips, tongue, and throat were white with the cruel spines.

“Get them out quick, or they’ll work in,” we were advised, and somebody produced a pair of tweezers, with which we fell to. But Jack suddenly developed the disposition of a wolf and the strength of a hippopotamus. Followed a rough-and-tumble which ended by our getting his shoulders to the mat on a “half Nelson” and hammer-lock hold. Those quills which we did not remove from the dog with the tweezers we pulled out of each other after the scrimmage.

At 6.15 Jill notified us plaintively that she had discovered a brother to Jack’s porcupine and had taken a bite at him. By the time we had pulled the barbs from her nose our supper was cold.

“Well, it’s a good thing for them to get wised up early,” Fred remarked, wiping the blood and sweat from his person. “They’ll know enough not to tackle another porcupine. They’re mighty intelligent dogs.”

We were still eating—time, 6.44—when a voice outside the mess tent inquired, “Whose dog is that with his nose full of quills?”

We looked at each other and Joe commenced to laugh.

“Are there any dogs besides ours around this camp?” I inquired of the waiter.

“No, sir.”

It was nearly midnight before Jill ran down her second victim and raised us from our slumbers by her yells, but by that time we had become so dexterous with the pincers that we could feed each other soup with them, so we were not long in getting back to bed.

The next day it rained. It rains every day in this country, but nobody minds it. In fact, the residents declare they don’t like sunshiny weather, asserting that it cracks their feet. One Cordovan had undertaken to keep a record of the sunshine, on the summer previous, but had failed because he had no stopwatch.

Before setting out Fred called my attention to Joe’s rifle.

“It looks like an air gun,” said he. “It wouldn’t kill a duck.”

Joe yielded the weapon up cheerfully for examination, and it did indeed look like a toy. Its bore was the size of a lady’s lead pencil, it was weather-beaten and rusty, and the stock looked as if it had been used to split kindling.

“She’s kind of dirty now,” the owner apologized, “but I’ll set her out in the rain to-night, and that will clean her up.”

My experience with Alaskan grizzlies has shown me that they are hard to kill and will carry much lead, hence in close quarters a bullet with great shocking power is more effective than one which is highly penetrative; but when we suggested adroitly to Joe that he use one of our extra guns instead of this relic, he declined, on the ground that his old gun was easier to carry.

We splashed through miles of muskeg swamp toward the forest where the big bear had been seen. We sank to our knees at every step; low brush hindered us; in places the surface of the ground quaked like jelly. We were well into the thickets before the dogs gave tongue and were off, with us crashing after them through the brush, lunging through drifts, tripping, falling, sweating. For ten minutes we followed, until a violent din in the jungle ahead advised us that their quarry was at bay.

Joe took his obstacles in the manner of a stag, finally bursting through the brush ahead of us with his air gun in his hand, only to stop and begin to swear eloquently.

“What is it?” I yelled, hip deep in a snowdrift.

“Have you got them pinchers handy?” came his answer.

For five days we combed those thickets and scoured the mountain sides without a shot, for those educated bear dogs got lost the moment we were out of sight, and made such a racket that we were forced to take turns retrieving them. They were passionately addicted to porcupines. No sooner were they through with one than they tackled another, and when not wailing to be “unquilled” they “heeled” us, ready to climb up our backs at the appearance of any other form of animal life.

“If we saw a bear they’d run between our legs and trip us up,” declared Joe, disgustedly.

Deciding, finally, that this section was too heavily timbered to hunt in without canine assistance, we sought more open country, and the next high tide found us scudding down the sound in a fast launch towards an island which for years had been shunned because of its ugly bears. Not a week before a party of native hunters had been chased into camp by a herd of grizzlies, hence we were in a hurry.

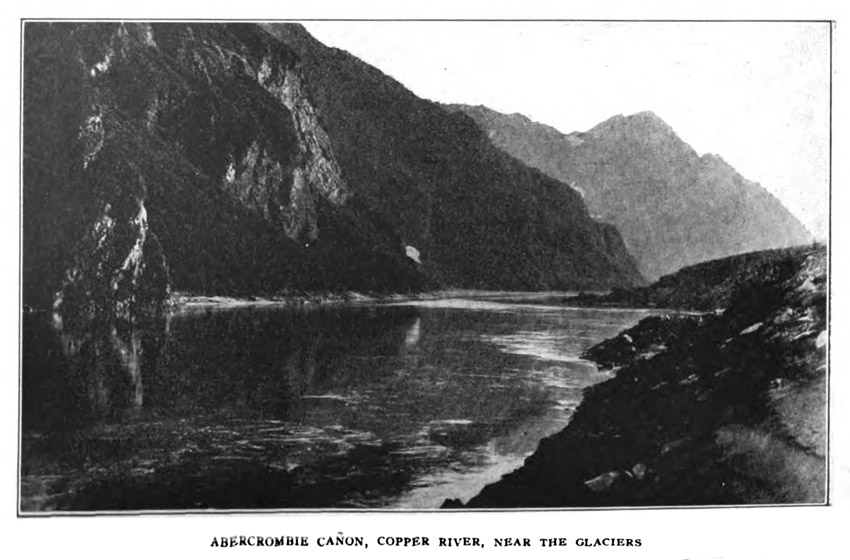

We skimmed past wooded shores which lifted upward to bleak snow fields veiled by ragged streamers of sea mist. Into a shallow, uncharted bay we felt our course, past cliffs white with millions of gulls, under towering columns of rock which thrust wicked fangs up through a swirling ten-mile tide and burst into clouds of shrieking birds at our approach.

We anchored abreast of two tumble-down shacks, and, as the afternoon was young, prepared for exploration. Ahead of us, rolling hills rose to a bolder range which formed the backbone of the island. The timbered slopes were broken by meadows of brilliant green, floored, not with grass, but with oozy moss.

“We’ve got three guns in the party,” said Joe, noting the preparations of Little, the owner of the launch, “so I’ll take the camera instead of my rifle. If we see a bear, them dogs can’t trip up more than two of us, which will leave one man to shoot and one man to use the machine.”

For hours we tramped the likeliest-looking country we had seen, but the wet moss showed no scars, the soft snow gave no evidence of having been trod, so I suggested that we divide, in order to cover more territory. Fred and Little, escorted by Jack and Jill, headed towards the flats, while Joe and I turned upward towards the heights.

Far above timber line we found our first sign, and farther on more tracks, all leading down the southern slope and not in the direction of our launch; so away we plodded, over crater lakes half hidden and choked with fifty feet of snow, skidding down crusted slopes, lowering ourselves hand over hand down gutters where the snow water drenched us from above. In time we left the deeper snows for thick brush, broken by open patches, and a ten-o’clock twilight was on us when we spied a fresh track. The moss had slipped and torn beneath the animal’s weight, and the sharp slashes of the claws had not yet filled with seepage.

“He’s close by,” said Joe, shifting the camera. “Gee! I wish I’d brought my gun instead of this thrashing machine,” and for the first time I realized that I had a new, small-calibered rifle with me, and had selected this day to try it, not expecting to have to rely upon it.

At a half run we followed down the trail, for there was no difficulty in picking it up wherever it crossed an open spot; but, without warning, the hillside ahead of us dropped off abruptly and we emerged upon the crest of a three-hundred-foot declivity choked with devil clubs and underbrush, the tops of the spruce showing beneath us. Joe altered his course towards the right when I saw, over the edge and not thirty feet away, a grizzled scruff of hair looking like the back of a porcupine.

“There he is!” I called, sharply. “Look out for yourself!”

I stepped to the edge of the bluff, for after my first glimpse that angry fur had disappeared—and looked down directly into the countenance of the largest grizzly in the world! Halted by our approach, he had paused just under the crest.

I have seen several Alaskan bears at close range, but I never saw one more distinctly than this, and I never saw a wickeder face than the one which glared up at me. His muzzle was as gray as a “whistler’s” back, the silver hairs of his shoulders were on end like quills, while his little pig eyes were bloodshot and blazing.

“What luck!” I thought, wildly, as the rifle sights cuddled together, but in that fraction of a second before the finger crooks, out from the brush behind him scrambled another bear, a great, lean, high-quartered brute of cinnamon shade, appearing, to my startled eyes, to stand as tall as a heifer.

Now, I never happened to be quite so intimate with a pair of grizzlies before, and since that moment I have frequently wondered how they happened to impress me so strongly with the idea of a crowd. The woods seemed suddenly filled with bears, and involuntarily I swept the glades below to see if this were a procession, or a bear carnival of some sort. That instant’s weakness cost me the finest pelt I ever saw, for at my movement bear number one leaped, and as I swung back to cover him I saw only a brown flank disappearing behind a barrier of projecting logs. At that distance I dared not take a chance on other than a head shot, so I jumped back, peering through the brush at our level, hoping to see him as he emerged.

Joe rushed forward to the edge of the hill, as if about to assault the cinnamon with his camera, and stepped directly between me and where I expected bear number one to show.

“Shoot! Shoot! Give it to him before he gets up here,” he yelled, hoarsely.

“Get out of the way!” I shouted, with my eyes glued upon the vegetation at his back.

He was still screaming: “Shoot! Shoot!” when his voice rose to a squeak, for up through the undergrowth lunged the big cinnamon, nearly trampling him. The bear rose to its hind legs and snorted, while Joe did a brisk dance, side-stepping neatly from underneath his photographic harness and fairly kicking himself up and out of his rubber boots. Before either footgear or camera had ended its flight he had sized up the dimensions of every spruce tree within a radius of forty rods, and was headed for the most promising.

I dare say my own movements were purely muscular at the time. I got out of Joe’s way in time to avoid being badly trampled, only to glimpse through my sights a brown rump over which the brush was closing, and remember deciding that with five shots in an untried weapon I didn’t care to chance a tail shot, especially with that other big gray bear concealed within forty feet—and more especially since Joe had staked the only available tree.

In the days which followed I cursed myself bitterly at the memory of those white-hot seconds.

“Gosh ‘lmighty! If I’d only had a six-shooter!” panted Joe, regarding me with disgust. “Why didn’t you give it to him?”

“I wanted to get the big one first,” said I.

“The big one! You never saw a bear any bigger than that one, did you?”

“Yes; I tried to get a shot at the old gray one.”

“Do you mean to say there was two of ’em?”

“I do! And the big one was in yonder all the time. He may be there now, for all I know.” As Joe picked up the camera he said, very quietly:

“I guess your eyesight was a little bit scattered. You ’ain’t seen any bear for quite a spell, have you?”

I resented the innuendo, and began to declare myself vigorously, when he interrupted: “Come on! Let’s get after them,” and away we went up the mountain side, running until we were breathless, guided plainly by great patches of torn moss and heavy indentations. We ran upgrade until I stumbled and staggered from exhaustion; we ran until my legs gave out and my lungs burst; we ran until I feared I should die at the next knoll; and we kept on running until I feared I might not die at the next knoll. Up, up, and up we went, until, two hundred yards above, a moving spot amid the timber halted us.

“G-g-give it to him!” gasped Joe. But the sights danced so drunkenly before my eyes that it is a wonder I did not shoot myself in the foot or fatally wound my guide. Then we were off again across sink holes scummed over with rotten ice into which we broke, up heartbreaking slopes, and through drifts where we wallowed halfway to our waists. In time the tracks we followed were joined by others, at which Joe wheezed:

“By g-gosh! You—were—right; there was —two! Come on!”

But, having righted myself in his eyes, I petered out completely. My legs refused to propel me faster than a miserable walk, so I turned the gun over to him and he floundered away, while I flopped to my back in the center of a wet moss patch and hoped a bear would come and get me.

Ten minutes later I heard him empty the magazine, but as he reappeared I knew the shots had been long ones.

“Say! That old gray one made the brown feller look like a cub,” said he, and we were miles away from the scene before he broke our silence to remark:

“You were wise not to shoot. If I’d ’a’ known that big one was so close to me I’d ’a’ tore my suspenders out by the roots and soared up over the treetops.”

Stone and Little, having covered the flats unsuccessfully, were rowing into the mouth of the creek when we slid down the bluff above the launch, but at my recital of our adventure Fred went violently insane and was for setting out for the scene of our encounter at once. Eventually he was calmed and we rolled up for a few hours’ rest on the floor of the launch.

I was half roused by the coffeepot sliding off the stove into my face. A few minutes later the ashpan emptied its contents over me, and I awoke under a bombardment of dishes, oil cans, and monkey wrenches, to find the boat on her beam ends in the mud, with every movable thing inside of her falling upon us. Little was swearing softly in his underclothes and bare feet.

“The tide is out and she’s standing on her hands,” he explained. “Confound a round-bottomed boat, anyhow! “

We stood on the starboard wall of the cabin to dress, then walked ashore where there had been eighteen feet of water on the night previous, to cook our breakfast in the rain.

Up the hills again we went, determined to see at last what was in those bear dogs of ours. For five miles we trailed our game, across snow fields where their tracks were knee-deep, over barren reaches where it took all our skill to pick up the signs, until, without warning, the dogs gave tongue and went abristle. They were off, with us after them, the woods ringing to their music, the bears just out of sight through the timber.

It was during the next hour that I proved to my own satisfaction that a two-hundred-pound man, considerably out of condition, can’t outrun a bear. Perhaps it is because the bear knows the country better.

Half a mile after I had quit running I found Fred panting and dripping on the other side of a stream.

“Where’s Joe?” I called.

“At the rate he was going when I lost sight of him, he’ll be due in Nome about noon, if his boots hold out,” Fred answered, sourly. “Where’s Little?”

“Fallen by the wayside. How did you cross the creek?”

“I didn’t! I ran through it. I’m wet to the ears.”

“Those are nice bear dogs of ours,” I ventured, at which my companion’s remarks were of a character not to be chronicled.

‘“Kindly remit hundred dollars and feed only at night,” he quoted. “Say, if those laphounds ever crab another shot for me I’ll—”

“And I’ll do the same,” I declared, heartily; and we shook hands over the compact.

We found Little at camp, clad in a pair of bath slippers, drying out his clothes, but Joe did not show up until nearly ten that night, and then he came alone.

“Did you kill those college bear dogs?” we inquired, hopefully.

“I couldn’t get close enough,” he said.

“Did you get a shot at the bears? “

“No! About twelve miles back yonder those two picked up five more. Your eighty pounds of Mother Goose dog had four tons of bear on the hike when I quit. It looks like they’re heading toward the north side of the island, and if we take the launch around to Big Bay to-night we may be able to pick them up to-morrow.”

It was high tide when Jack and Jill appeared on the bank, and as Joe boosted them over the rail they beamed upon us as if to say:

“This has indeed been a glorious day, and we’ll make this bear hunt a success if it takes all summer.” We forbore to saddle them with what lay upon our souls.

We anchored in Big Bay as a three-o’clock dawn crept over the southern range, only to be awakened a few hours later by another avalanche of pots and pans. The launch was doing her morning hand stand, and I found a streamlet of cylinder oil trickling down my neck. Fred had been assaulted from ambush by a sack of soft coal, while the cupboard had hurtled a week’s grub into the midst of Little’s dreams. Joe alone was unconscious of his bedfellows, which comprised the rest of our cargo; he was slumbering on his back, snoring like a sea lion at feeding time.

A mile of tide flats glistened between us and the shore; on every hand the hills were white with desolate snow. Having dressed stiffly, propped at various angles, we ate a cold breakfast, for the stove would not draw, and had it drawn we could not have held the coffeepot against it; then Joe and I lowered ourselves into the slime overside, for Little had decided to stay with the launch until high tide, while Fred’s heels were blistered so that he could not wear his boots. We went without the dogs.

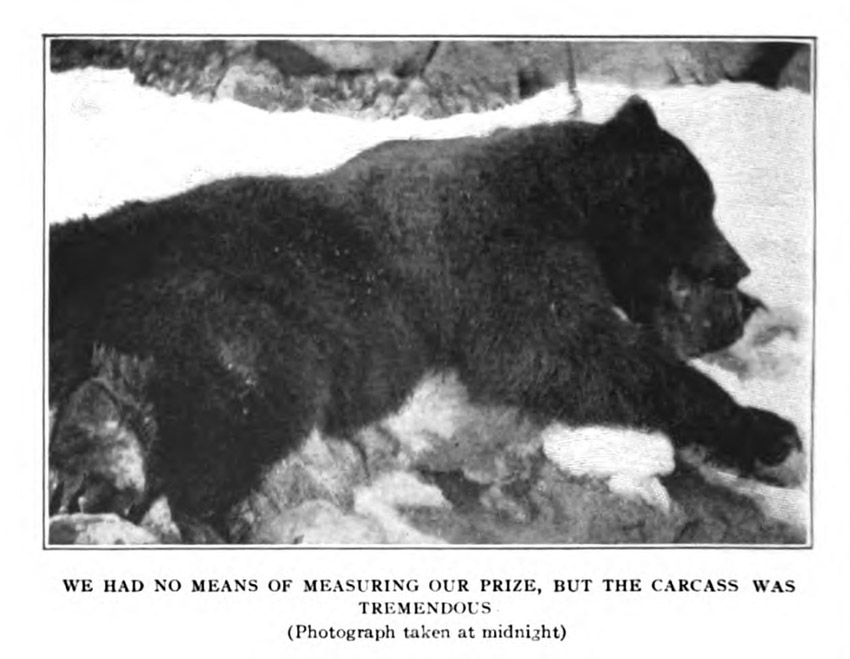

At nine that night I staggered wearily out from the timber onto the beach. A mile of mud lay between the bank and the water, and two miles beyond that I sighted the launch. Fred and Little heard my shots, and by the time I had reached the low-water line they were under way. Out another half mile into the creeping tide I waded, until it was up to the tops of my boots. I was utterly exhausted, my feet were bruised and pounded to a jelly, every muscle in me ached. For fourteen hours Joe and I had shoved ourselves through the snow, in places waist deep, crossing cañons, creeping up endless slopes until we had traversed the island and the open sea lay before us. Snow, snow, snow everywhere, until our eyes had ached and our vision had grown distorted.

We had found the tracks of those seven bears, but they were miles away and headed toward the west, whither we could not follow. We had become separated later and I had come home alone, ten miles as the crow flies, across the most desolate region I ever saw.

I had followed a herd of five bears several miles, but had abandoned the chase when it grew late. One track I measured repeatedly from heel to toe of the hind foot. It took my Winchester from the shoulder plate clear up two inches past the hammer.

Two hours after I was aboard we heard Joe’s air gun popping faintly. He, too, had followed those five bear tracks, holding to them an hour after my trail had sheered off. We had covered better than thirty miles of impossible going and were half dead.

The next day found us back at the cabins; for the north side of the island was too killing, and as Little had business to attend to, he left us, promising to send the launch back in ten days. Then followed as heartbreaking a week as I ever endured. Every morning we were off early, to drag ourselves in ten, twelve, perhaps fourteen hours later, utterly exhausted. Every noon we stopped to dry out over a smoky fire, for an hour’s work on the slopes threw us into a dripping perspiration, which the chill wind discovered at the first breathing spell.

Our feet were constantly wet from the melting snow, and the rain did what remained to be done. We stood barelegged and shivering in the snow, our feet on strips of bark, the while we scorched our underclothes and swore at the weather. Finally, on one particularly drenching morning, Fred and I struck and declared for rest. Our feet and ankles were so swollen that we hobbled painfully, while our systems yelled for sleep.

About noon Joe said this idleness palled on him and he guessed he’d take a little trip. If he didn’t get back that night we needn’t worry, as he intended to follow any trail he struck until he got a shot, if he had to sleep out in the rain for a week. He took no grub, his outfit consisting, as usual, of the hand ax at his belt and the popgun between his shoulder blades

“It’ll be just our luck for him to get a bear to-day,” said Stone. “It’s the first time in ten days we’ve laid off.”

“Maybe so,” said I, “but if he shoots a bear with that child’s gun and the animal happens to find it out, it may go hard with him.”

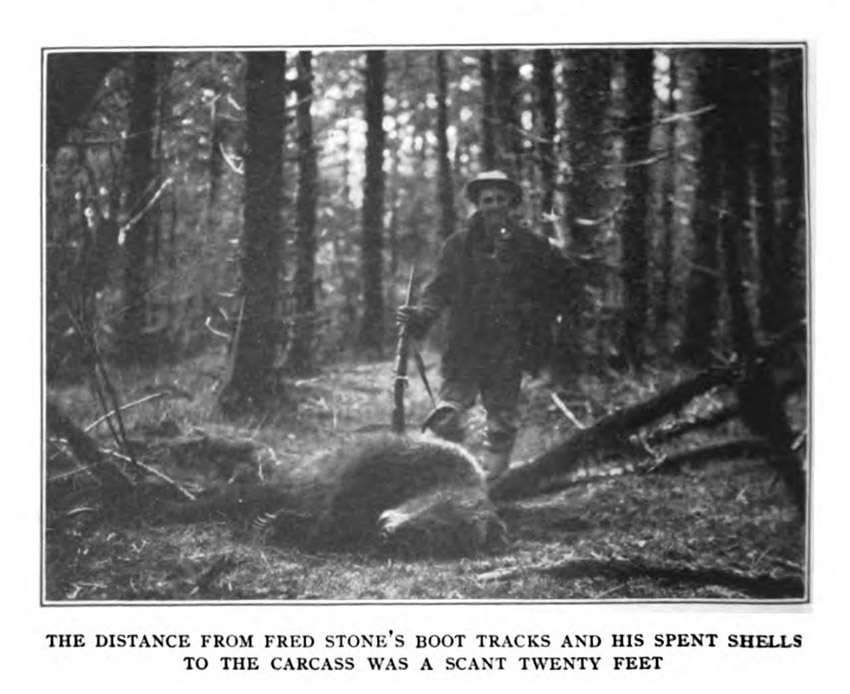

Two hours after dark we heard a voice outside the cabin:

“Hey! What do you think of this?”

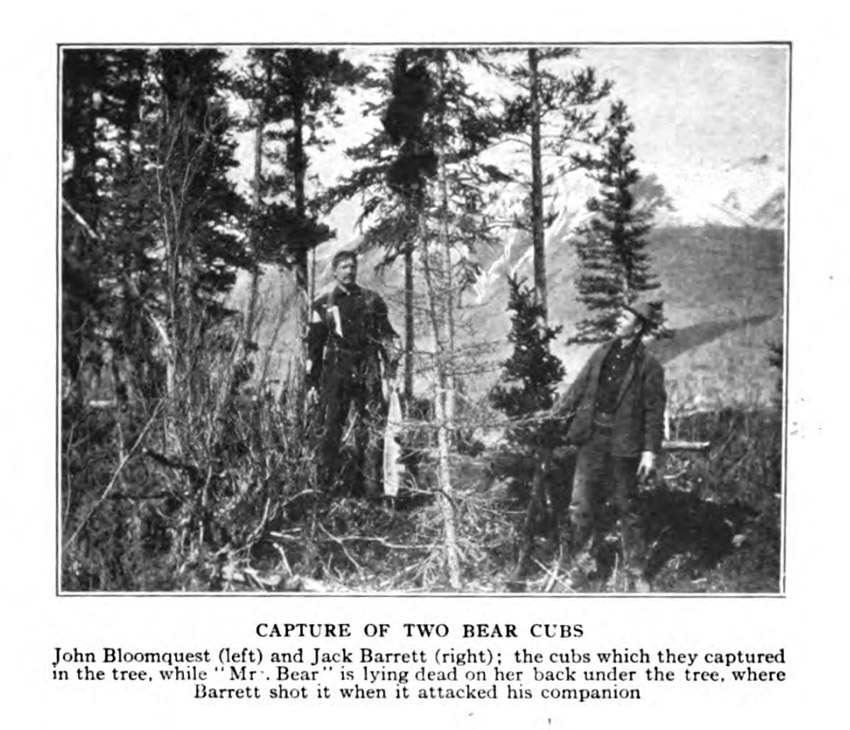

We hobbled out in our sock feet as Joe flung from his shoulders a great brown skin the ends of which dragged on either side. The fur was deeper than a man’s wrist, the ears were a foot apart, the nose was curled in a ferocious snarl above the long yellow teeth.

“See here!” He held up a cub skin. “There was two other little fellers, but they got away.”

“What did I tell you?” Fred groaned. The fire of a consuming envy burned within us as we bombarded Joe with questions.

It seems he had struck a trail on the other side of the range, and although it was twenty-four hours old he had followed mile after mile, running most of the way to cover, before dark, the distance it had taken the mother and the cubs two days to go. It was growing dark when he overtook them, high up on a mountain side covered with patches of gnarled spruce and wind-flattened bushes.

“When I see I was close to ’em I made a circuit up the hill so’s to head ’em off,” he explained; “but I underjudged her, and she must have snuffed me.” He had told the first part of his story graphically, but at this point he closed his narrative in a sudden, matter-of-fact way.

“Go on,” we demanded, beside ourselves.

“Well, that’s all. Just as I scrambled up where I could get a peek I seen her right on top of me, coming full tilt, r’aring up on her hind feet every few jumps for a look. She must have snuffed me.”

“Yes, yes. Hurry up!” we chorused.

“Her nose was curled up just the way it is now and she was roaring something fierce. She was so close I seen her eyes blazing and all her hair on end, but those cubs—say, you’d ’a’ laughed at them cubs. They was snarling like dogs and all headed for my legs.”

“Good Lord!” I ejaculated, sizing up the skin, which was fully ten feet long as it lay, “she must have looked as tall as a house.”

“Yes, she looked pretty tall,” Joe agreed. “Have you got anything to eat handy?” But we forcibly gouged the rest of the story from him.

“Well, she was so close on to me that I knew I had to get her—so I—did. But you’d ’a’ laughed at them—”

“Where did you hit her?” we demanded.

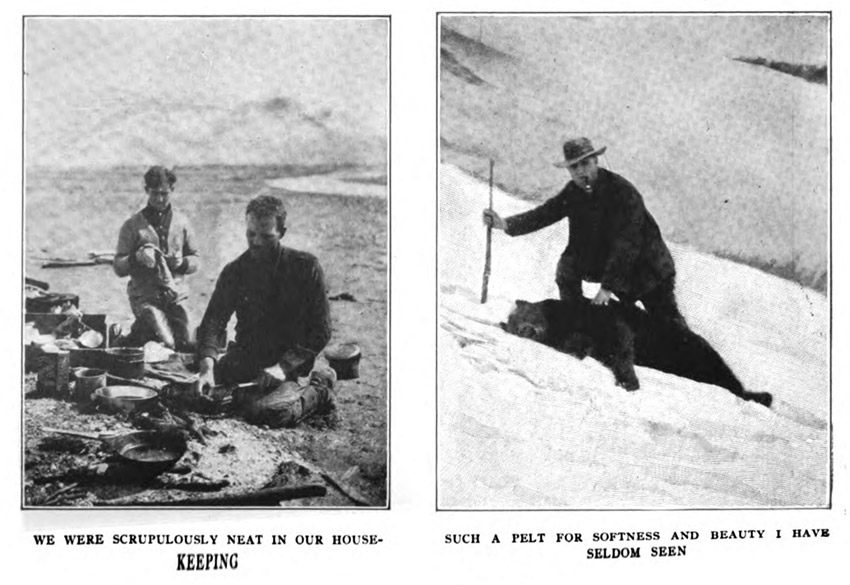

“Oh, in the eye. See!” He laid his finger on a tiny hole half an inch back of the half-inch eye, which was still fixed in an ugly stare, He apologized as he did so. “You see, my footing wasn’t very good and I was half dead from running, or I’d have shot better and got her the first time.”

“Then you had to shoot again?”

“Oh yes; twice more. She fell at the first crack, and that give me time to reload. When she riz up again I tried for her heart, but she throwed up her forearm, and all I did was to break her leg. Look! That give me a chance, though, for when she jumped at me the next time her leg give out and throwed her off, so I sidestepped her. But those cubs! Say, they was the funniest things!” He began to laugh. “I wanted to catch ’em, but they was too big. They was snarling around my feet all the time and I was kicking at ’em so’s to get a shot at the old one. I had to knock this one down finally, which give me time to wallop the old lady in the neck. If I hadn’t been so tired I’d have run down them other two, but they was too fast for me. I chased ’em half a mile, but somehow I couldn’t get up to ’em. It’s too bad she snuffed me.”

Joe had returned, skinned the two carcasses, and packed the hides in through the deep snow, although the mother’s pelt alone was a heavy burden for a strong man on good footing.

The cabin walls were not large enough to hold the skin, so our guide stayed in camp the next day to flesh and salt it, while Fred and I made another unsuccessful journey, covering twenty-five miles of the territory where Joe had been.

Three days later, when Little sent back the launch, we were ready to quit in disgust and head towards the Copper River glaciers, for the bears seemed utterly to have forsaken this island. We could find no fresh signs, we could discover no indications as to where they were feeding.

A mile from the mouth of the bay we ran hard aground, and a falling tide left us high and dry, but held upright this time by the cabin doors, which we had removed and used as props.

“I’m going over into those woods where Little and I went the first day,” Fred announced, and Joe went with him, while I, disheartened, went fishing in the channel.

Having drifted opposite the mouth of a tiny creek without a strike, I rowed ashore and wandered aimlessly back into the open flat through which the stream meandered. It was the first time since landing in Alaska that I had been without my gun, and within three hundred yards from the shore I encountered fresh bear tracks. As I regarded them, a movement at my back caused me to whirl, and there, where I could have hit him with a stone, was my bear observing me curiously.

We looked each other over for several moments. We were both blonds, although his fur was a bit lighter than mine. When I moved, his hair rose; when he moved, my hair did the same. He was much the larger of the two. I matched him up with my dining-room rug, and he went all right. I must likewise have harmonized with some color scheme of his, for he took a step towards me.

Remembering that my hunting knife was in the gunwale of the skiff and my rifle halfway across the bay, I closed the interview and went after them. It was a nice cool day and I hurried a bit. I felt light in the body and strong in the legs, which provoked in me a sudden disposition to disprove my previous theory that a two-hundred-pound man out of condition cannot outrun a bear. You see, this was the first bear I had encountered which really matched my furniture, and—in fact, there were sundry reasons why I increased my normal speed of limb.

To stroll means to advance carelessly. I strolled up to the skiff so carelessly that I nearly broke a leg getting into it, then headed for the launch. Perhaps a rear view had convinced the bear that my hair was too stiff, or that I was not sufficiently well furred for his use; at any rate, he did not pursue me, and in fifteen minutes I was back again and had taken up the trail. Two hours later I stumbled out of the woods, sweaty, smelling of blood, and supremely proud of a wet, heavy skin which dragged upon my aching shoulders, its points trailing on the ground behind me.