a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Forsaken Inn Author: Anna Katharine Green * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1700621h.html Language: English Date first posted: July 2017 Most recent update: July 2017 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Chapter 1. - The Oak Parlor

Chapter 2. - Burritt

Chapter 3. - A Fearful Discovery

Chapter 4. - Questions and Answers

Chapter 5. - An Interim of Suspense

Chapter 6. - The Recluse

Chapter 7. - Two Women

Chapter 8. - A Sudden Betrothal

Chapter 9. - Marah

Chapter 10. - At the Foot of the Stairs

Chapter 11. - Honora

Chapter 12. - Edwin Urquhart

Chapter 13. - Before the Wedding

Chapter 14. - A Cassandra at the Gate

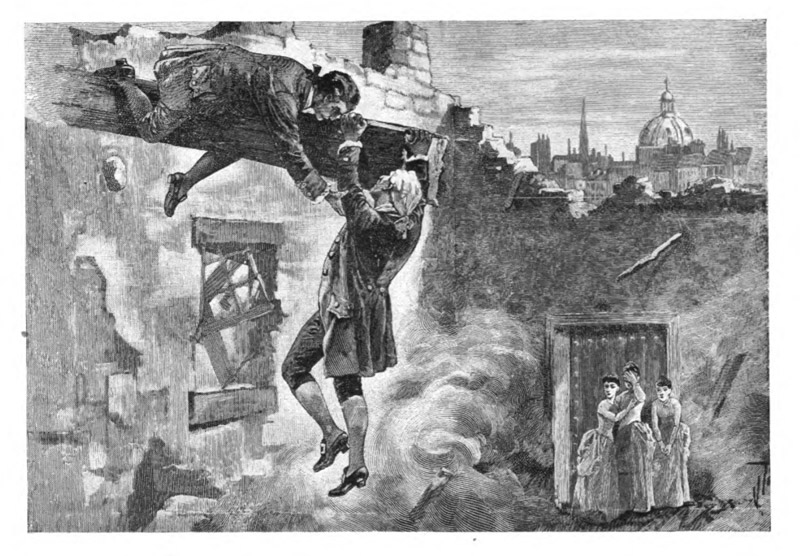

Chapter 15. - The Catastrophe

Chapter 16. - A Dream Ended

Chapter 17. - Strange Guests

Chapter 18. - Mrs. Truax Talks

Chapter 19. - In the Halls at Midnight

Chapter 20. - The Stone in the Garden

Chapter 21. - In the Oak Parlor

Chapter 22. - A Surprise for Honora

Chapter 23. - In the Secret Chamber

Chapter 24. - The Marquis

Chapter 25. - Mark Felt

Chapter 26. - For the Last Time

Chapter 27. - A Last Word

I WAS riding between Albany and Poughkeepsie. It was raining furiously, and my horse, already weary with long travel, gave unmistakable signs of discouragement. I was, therefore, greatly relieved when, in the most desolate part of the road, I espied rising before me the dim outlines of a house, and was correspondingly disappointed when, upon riding forward, I perceived that it was but a deserted ruin I was approaching, whose fallen chimneys and broken windows betrayed a dilapidation so great that I could scarcely hope to find so much as a temporary shelter therein.

Nevertheless, I was so tired of the biting storm that I involuntarily stopped before the decayed and forbidding structure, and was, in truth, withdrawing my foot from the stirrup, when I heard an unexpected exclamation behind me, and turning, saw a chaise, from the open front of which leaned a gentleman of most attractive appearance.

“What are you going to do?” he asked.

“Hide my head from the storm,” was my hurried rejoinder. “I am tired, and so is my horse, and the town, according to all appearances, must be at least two miles distant.”

“No matter if it is three miles! You must not take shelter in that charnel-house,” he muttered; and moved along in his seat as if to show me there was room beside him.

“Why,” I exclaimed, struck with sudden curiosity, “is this one of the haunted houses we hear of? If so, I shall certainly enter, and be much obliged to the storm for driving me into so interesting a spot.” I thought he looked embarrassed. At all events, I am sure he hesitated for a moment whether or not to ride on and leave me to my fate. But his better impulses seemed to prevail, for he suddenly cried: “Get in with me, and leave mysteries alone. If you want to come back here after you have learned the history of that house, you can do so; but first ride on to town and have a good meal. Your horse will follow easily enough after he is rid of your weight.”

It was too tempting an offer to be refused; so thankfully accepting his kindness, I alighted from my horse, and after tying him to the back of the chaise, got in with this genial stranger. As I did so I caught another view of the ruin I had been so near entering.

“Good gracious!” I exclaimed, pointing to the structure that, with its projecting upper story and ghastly apertures, presented a most suggestive appearance, “if it does not look like a skull!”

My companion shrugged his shoulders, but did not reply. The comparison was evidently not a new one to him.

That evening, in a comfortable inn parlor, I read the following manuscript. It was placed in my hands by this kindly stranger, who in so doing explained that it had been written by the last occupant of the old inn I was so nearly on the point of investigating. She had been its former landlady, and had clung to the ancient house long after decay had settled upon its doorstep and desolation breathed from its gaping windows. She died in its north room, and from under her pillow the discolored leaves were taken, the words of which I now place before you.

January 28, 1775.

I do not understand myself. I do not understand my doubts nor can I analyze my fears. When I saw the carriage drive off, followed by the wagon with its inexplicable big box, I thought I should certainly regain my former serenity. But I am more uneasy than ever. I cannot rest, and keep going over and over in my mind the few words that passed between us in their short stay under my roof. It is her face that haunts me. It must be that, for it had a strange look of trouble in it as well as sickness; but neither can I forget his, so fair, so merry, and yet so unpleasant, especially when he glanced at her and—as I could not help but think before they went away—when he glanced at me. I do not like him, and the chills creep over me whenever I remember his laugh, which was much too frequent to be decent, considering how poorly his young wife looked.

They are gone, and their belongings with them; but I am as much afraid as if they were still here. Why? That is what I cannot tell. I sit in the room where they slept, and feel as strange and terrified as if I had encountered a ghost there. I dread to stay and dread to move and write, because I must relieve myself in some way—that is, if I am to have any sleep to-night. Am I ill, or was there something unexplained and mysterious in their actions? Let me go over the past and see.

They came last evening about twilight. I was in the front of the house, and seeing such a good-looking couple in the carriage, and such a pile of baggage with them that they had to have an extra wagon to carry it, I ran out in all haste to welcome them. She had a veil drawn over her face, and it was so thick that I could not see her features, but her figure was slight and graceful, and I took a fancy to her at once, perhaps because she held her arms out when she saw me, as if she thought she beheld in me a friend. He did not please me so well, though there is no gainsaying that he is handsome enough, and speaks, when he wishes to, with a great deal of courtesy. But I thought he ought to give his attention to his young and ailing wife, instead of being so concerned about his baggage. Had that big box of his contained gold, he could not have looked at it more lovingly or been more anxious about its handling. He said it held books; but, pshaw! what is there in books, that a man should love them better than his wife, and watch over their welfare with the utmost concern, while allowing a stranger to help her out of the carriage and up the inn steps?

But I will not dwell any longer upon this. Men are strange beings, and must not be judged by rules that apply to women. Let me see if I can remember when it was that I first saw her face. Ah, yes; it was in the parlor. She had taken a seat there while her husband looked through the house and decided which room to take. There were four empty, and two of them were the choicest and airiest in the inn, but he passed by these and insisted upon taking one that was stuffy with disuse, because it was on the ground floor, and so convenient for us to bring his great box into.

His great box! I was so provoked at this everlasting concern about his great box, that I ran to the parlor, intending to ask the lady herself to interfere. But when I got to the threshold I paused, and did not speak, for the lady—or Mrs. Urquhart, as I presently found she called herself—had risen from her seat and was looking in the glass with an expression so sad and searching that I forgot my errand and only thought of comforting her. But the moment she heard my step she drew down the veil which she had tossed back, and coming quickly toward me, asked if her husband had chosen a room.

I answered in the affirmative, and began to complain that it was not a very cheerful one. But she paid small attention to my words, and presently I found myself following her to the apartment designated. She entered, making a picture, as she crossed the threshold, which I shall not readily forget. For in her short, quick walk down the hall she had torn the bonnet from her head, and though she was not a strictly beautiful woman, she was sufficiently interesting to make her every movement attractive. But that is not all. For some reason the moment possessed an importance for her which I could not measure. I saw it in her posture, in the pallor of her cheeks and the uprightness of her carriage. The sudden halt she made at the threshold, the half-startled exclamation she gave as her eyes fell on the interior, all showed that she was laboring under some secret agitation. But what was the cause of that agitation I have not been able to determine. She went in, but as she did so, I heard her murmur:

“Oak walls! Ah, my soul! it has come soon!”

Not a very intelligible exclamation, you will allow, but as intelligible as her whole conduct. For in another moment every sign of emotion had left her, and she stood quite calm and cold in the center of the room. But her pallor remained, and I cannot make sure now whether this betokened weary resignation or some secret and but half recognized fear.

Had I looked at him instead of at her, I might have understood the situation better. But, though I dimly perceived his form drawn up in the empty space at the left of the door, it was not until she had passed him and flung herself into a chair, that I thought to look in his direction. Then it was too late, for he had turned his face aside and was gazing with rather an obtrusive curiosity at the old-fashioned room, murmuring, as he did so, some such commonplaces to his wife as:

“I hope you are not fatigued, my dear. Fine old house, this. Quite English in style, eh?”

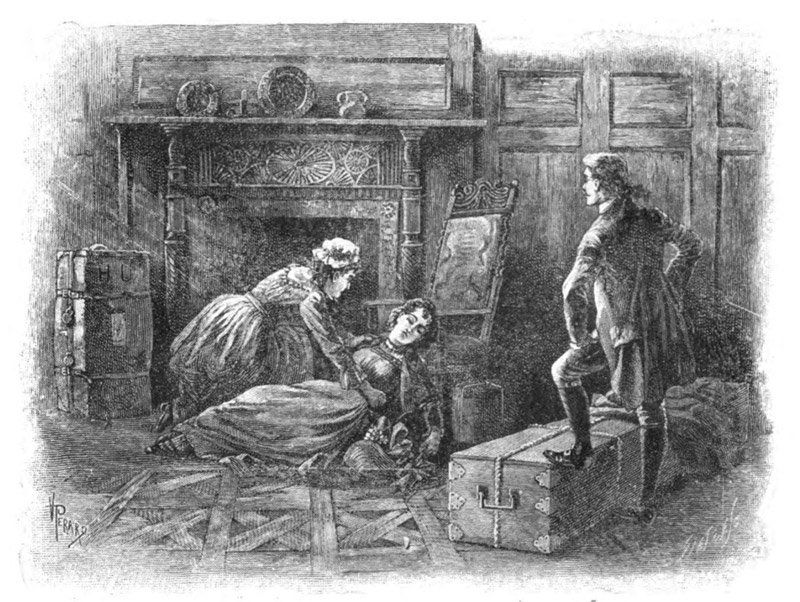

To all of which she answered with a nod or word, till suddenly, without look or warning, she slipped from her chair and lay perfectly insensible upon the dark boards of the worm-eaten floor.

I uttered an exclamation, and so did he; but it was my arms that lifted her and laid her on the bed. He stood as if frozen to his place for a moment, then he mechanically lifted his foot and set it with an air of proprietorship on the box before which he had been standing.

“Strange and inexplicable conduct,” thought I, and looked the indignation I could not but feel. Instantly he left his position and hastened to my side, offering his assistance and advice with that heartless officiousness which is so unbearable when life and death are at stake.

I accepted as little of his help as was possible, and when, after persistent effort on my part, I saw her lids fluttering and her breast heaving, I turned to him with as inoffensive an air as my mingled dislike and distrust would admit, and asked how long they had been married. He flushed violently, and with a sudden rage that at once robbed him of that gentlemanly appearance which, in him, was but the veneer to a coarse and brutal nature, he exclaimed:

“— you! and by what right do you ask that?”

But before I could reply he recovered himself and was all false polish again, bowing with exaggerated politeness, as he exclaimed:

“Excuse me; I have had much to disturb me lately. My wife’s health has been very feeble for months, and I am worn out with anxiety and watching. We are now on our way to a warmer climate, where I hope she will be quite restored.”

And he smiled a very strange and peculiar smile, that went out like a suddenly extinguished candle, as he perceived her eyes suddenly open, and her gaze pass reluctantly around the room, as if forced to a curiosity against which she secretly rebelled.

“I think Mrs. Urquhart will do very well now,” was his hurried remark at this sight. He evidently wished to be rid of me, and though I hated to leave her, I really found nothing to say in contradiction to his statement, for she certainly looked completely restored. I therefore turned away with a heavy heart toward the door, when the young wife, suddenly throwing out her arms, exclaimed:

“Do not leave me in this horrible room alone! I am afraid of it—actually afraid! Couldn’t you have found some spot in the house less gloomy, Edwin?”

I came back.

“There are plenty of rooms—” I began.

But he interrupted me without any ceremony.

“I chose this room, Honora, for its convenience. There is nothing horrible about it, and when the lamps are lit you will find it quite pleasant. Do not be foolish. We sleep here or nowhere, for I cannot consent to go upstairs.”

She answered nothing, but I saw her eyes go traveling once again around the walls, followed in a furtive way by his. Whereupon I looked about me, too, and tried to get a stranger’s impression of the place. I was astonished at its effect upon my imagination. Though I had been in and out of the room fifty times before I had never noticed till now the extreme dismalness and desolation of its appearance.

Once used as an auxiliary parlor, it had that air of uninhabitableness which clings to such rooms, together with a certain something else, equally unpleasant, to which at that moment I could give no name, and for which I could neither find then nor now any sufficient reason. It was paneled with oak far above our heads, and as the walls above had become gray with smoke, there was absolutely no color in the room, not even in the hangings of the gaunt four-poster that loomed dreary and repelling from one end of the room. For here, as elsewhere, time had been at work, and tints that were once bright enough had gradually been subdued by dust and smoke into one uniform dimness. The floor was black, the fireplace empty, the walls without a picture, and yet it was neither from this grayness nor from this barrenness that one recoiled. It was from something else—something that went deeper than the lack of charm or color—something that clung to the walls like a contagion and caught at the heart-strings where they are weakest, smothering hope and awakening horror, till in each faded chair a ghost seemed sitting, gazing at you with immovable eyes that could tell tales, but would not.

There was but one window in the room, and that looked toward the west. But the light that should have entered there was frightened, also, and halted on the ledge without, balked by the thick curtains that heavily enshrouded it. A haunted chamber! or so it appeared at that moment to my somewhat excited fancy, and for the first time in my life, here, I felt a dread of my own house, and experienced the uncanny sensation of some one walking over my grave.

But I soon recovered myself. Nothing of a disagreeable nature had ever happened in this room, nor had we had any special reason for shutting it up, except that it was in an out-of-the-way place, and not usually considered convenient, notwithstanding Mr. Urquhart’s opinion to the contrary.

“Never mind,” said I, with a last effort to soothe the agitated woman. “We will let in a little light, and dissipate some of these shadows.” And I attempted to throw back the curtains of the window, but they fell again immediately and I experienced a sensation as of something ghostly passing between us and the light.

Provoked at my own weakness, I tore the curtains down and flung them into a corner. A straggling beam of sunset color came in, but it looked out of place and forlorn upon that black floor, like a stranger who meets with no welcome. The poor young wife seemed to hail it, however, for she moved instantly to where it lay and stood as if she longed for its warmth and comfort. I immediately glanced at the fireplace.

“I will soon have a rousing fire for you,” I declared. “These old fireplaces hold a large pile of wood.”

I thought, but I must be mistaken, that he made a gesture as if about to protest, but, if so, reason must have soon come to his aid, for he said nothing, though he looked uneasy, as I moved the andirons forward and made some other trivial arrangements for the fire which I had promised them.

“He thinks I am never going,” I muttered to myself, and took pleasure in lingering; for, anxious as I was to have the room heated up for her comfort, I knew that every moment I stayed there would be one less for her to spend with her surly husband alone.

At last I had no further excuse for remaining, and so with the final remark that if the fire failed to give them cheer we had a sitting room into which they could come, I went out. But I knew, even while saying it, that he would not grant her the opportunity of enjoying the sitting room’s coziness; that he would not let her out of his sight, if he did out of the room, and that for her to remain in his presence was to be in darkness, solitude and gloom, no matter what walls surrounded her or in what light she stood.

My impressions were not far wrong. Mr. and Mrs. Urquhart came to supper, but that was all. Before the others had finished their roast they had eaten their pudding and gone; and though he had talked, and laughed, and shown his white teeth, the impression left behind them was a depressing one which even Hetty felt, and she has anything but a sensitive nature.

I went to the room once again in the evening. I found them both seated, but in opposite parts of the room; he by his great box, and she in an easy chair which I had caused to be brought down from my own room for her especial use. I did not look at him, but I did at her, and was astonished to see, first, how dignified she was; and next how pretty. Had she been happy and at her ease, I should probably have been afraid of her, for the firelight, which now shone on her wan young cheek, brought out evidences of character and culture in her expression which proved her to be, by birth and training, of a position superior to what one would be led to expect from her husband’s aspect and manner. But she was not happy nor at her ease, and wore, instead of the quiet and commanding look of the great lady, such an expression of secret dread that I almost forgot my position of landlady, and should certainly, if he had not been there, fallen at her side and taken her poor, forsaken head upon my breast. But that silent, immovable form, sitting statue-like beside his big box, smiling, for aught I knew, but if so, breathing out a chill that forbade all exhibition of natural feeling, held me in check, as it held her, so that I merely inquired whether there was anything I could do for her; and when she shook her head, starting a tear down her cheek as she did so, I dared do nothing more than give her one look of sympathetic understanding, and start for the door.

A command from him stopped me.

“My wife will need a slight supper before she goes to bed,” said he. “Will you be good enough to see that one is brought?”

She roused herself up with quite a startled look of wonder.

“Why, Edwin,” she began, “I never have been in the habit—”

But he hushed her at once.

“I know what is best for you,” said he. “A small plate of luncheon, Mrs. Truax; and let it be nice and inviting.”

I courtesied, gave her another glance, and went out. Her countenance had not lost its look of wonder. Was he going to be considerate, after all?

The lunch was prepared and taken to her.

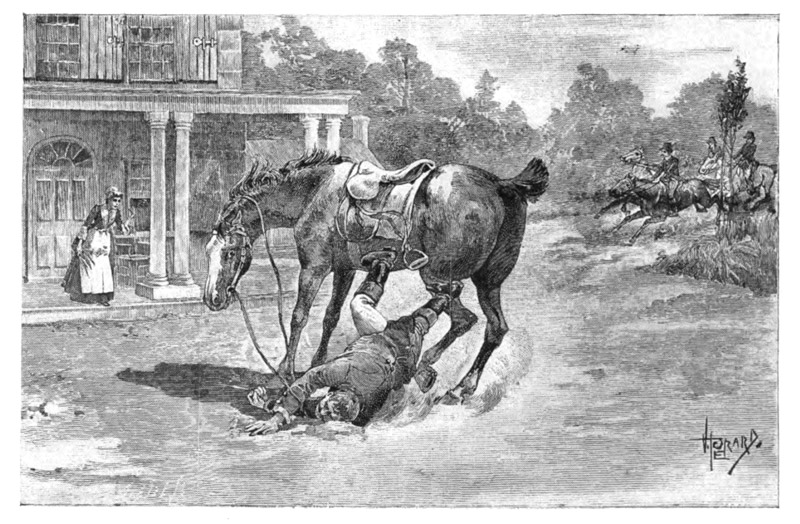

Not long after this the inn quieted down, and such guests as were in the house prepared for rest. Midnight came; all was dark in room and hall. I was sure of this, for I went through the whole building myself, contrary to my usual habit, which was to leave this task to my man-of-all-work, Burritt. All was dark, all was quiet, and I was just dropping off to sleep, when there shot up suddenly from below a shriek, which was quickly smothered, but not so quickly that I did not recognize in it that tone which is only given by hideous distress or mortal fear.

“It is Mrs. Urquhart!” I cried in terror, to myself; and plunging into my clothes, I hurried down stairs.

All was quiet in the halls, but as I proceeded toward their room I perceived a figure standing near the doorway, which, in another moment, I saw to be that of Burritt. He was trembling like a leaf, and was bent forward, listening.

“Hush!” he whispered; “they are talking. All seems to be right. I just heard him call her darling.”

I drew the man away and took his place. Yes; they were talking in subdued but not unkindly tones. I heard him bid her be composed, and caught, as I thought, a light reply that ought to have satisfied me that Mrs. Urquhart had simply suffered from some nightmare horror at which she was as ready to laugh now as he. But my nature is a contradictory one, and I was not satisfied. The echo of her cry was still ringing in my ears, and I felt as if I would give the world for a momentary peep into their room. Influenced by this idea, I boldly knocked, and in an instant—too soon for him not to have been standing near the door—I heard his breath through the keyhole and the words:

“Who is there, and what do you want?”

“We heard a cry,” was my response, “and I feared Mrs. Urquhart was ill again.”

“Mrs. Urquhart is very well,” came hastily, almost gayly, from within. “She had a dream, and was willing that every one should know it. Is not that all?” he said, seemingly addressing his wife.

There was a murmur within, and then I heard her voice. “It was only a dream, dear Mrs. Truax,” it said, and convinced against my will, I was about to return to my room, when I brushed against Burritt. He had not moved, and did not look as if he intended to.

“Come,” said I, “there is no use of our remaining here.”

“Can’t help it,” was his whispered reply. “In this hall I stay till morning. When I see a lamb in the care of a wolf, I find it hard to sleep. There is a door between us, but please God there shan’t be anything more.”

And knowing Burritt, I did not try to argue, but went quietly and somewhat thoughtfully to my room, vaguely relieved that I left him behind, though convinced there would be no further need of his services.

And so it was. No more sounds disturbed the house, and when I came down, with the first streak of daylight, I found Burritt gone about his work.

Breakfast was served to the Urquharts in their own room. I had wished to carry it in myself, but I found this inconvenient, and so I sent Hetty. When she came back I asked her how Mrs. Urquhart looked.

“Very well, ma’am,” was the quick reply. “And see! I don’t think she’s as unhappy as we all thought last night, or she wouldn’t be giving me a bright new crown.”

I glanced at the girl’s palm. There was indeed a bright new crown in it.

“Did she give you that?” I inquired.

“Yes, ma’am; she herself. And she laughed when she did it, and said it was for the good breakfast I had brought her.”

I was busy at the time, and could not stop to give the girl’s words much thought; but as soon as I had any leisure, I went to see for myself how Mrs. Urquhart looked when she laughed.

I was five minutes too late. She had just donned her traveling bonnet and veil, and though I heard her laugh slightly once, I did not see her face.

I saw his, however, and was surprised at the good nature in it. He was quite the gentleman, and if he had not been in such a hurry, would have doubtless made, or endeavored to make, himself very agreeable. But he was just watching his great box carried out to the wagon, and while he took pains to talk to me—was it to keep me from talking to her?—he was naturally a little absentminded. He was in haste, too, and insisted upon placing his wife in the carriage before all his baggage was taken from the room. And she seemed willing to go. I watched her on purpose to see, for I was not yet satisfied that she was not playing a part at his dictation, but I could discover no hint of reluctance in her manner, but rather a quiet alacrity, as if she felt glad to quit a room to which she had taken a dislike.

When I saw this, and noted the light step of her feet, I said to myself that I had been a fool, and lost a little of the interest I had felt for her. Nor did I regain it till after they had driven away, though she showed a consideration for me at the last which I had not expected, leaning from the carriage to give me a good-by pressure of the hand, and even nodding again and again as they disappeared down the road. For the fear which could be dissipated in a night was not the fear with which I had credited her; and of ordinary excitements and commonplace natures I had seen enough in my long experience as landlady to make me unwilling to trouble myself with any more of them.

But when the carriage and its accompanying wagon had quite disappeared, and Mr. and Mrs. Urquhart were virtually as far beyond my reach as if they were already in New York, I became conscious of a great uneasiness. This was the more strange in that there seemed to be no especial cause for it. They had left my house in apparently better spirits than they had entered it, and there was no longer any reason why I should concern myself about them. And yet I did concern myself, and came into the house and into the room they had just vacated, with feelings so unusual that I was astonished at myself, and not a little provoked. I had a vague feeling that the woman who had just left was somehow different from the one I had seen the night before.

But I am a busy woman, and I do not think I should have let this trouble me long if it had not been for Burritt. But when he came into the room after me, and shut the door behind him and stood with his back against it, looking at me, I knew I was not the only one who felt uncomfortable about the Urquharts. Rising from the chair where I had been sitting, counting the cost of fitting up that room so as to make it look habitable, I went toward him and met his gaze pretty sharply.

“Well, what is it?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” was the somewhat sullen reply. “I don’t feel right about those folks, and yet—” He stopped and scratched his head—“I don’t know what I’m afraid of. Are you sure they left nothing behind them?”

The last words were uttered in such a tone I did not know for a minute what to say.

“Left anything behind them!” I replied. “They left their money, if that is what you mean. I don’t know what else they could have left.”

Notwithstanding which assertion, I involuntarily glanced about the room as if half expecting to see some one of their many belongings protruding from a hitherto unsearched corner. His gaze followed mine, but presently returned, and we stood again looking at each other.

“Nothing here,” said I.

“Where is it, then?” he asked.

I frowned in displeasure.

“Where is what?” I demanded. “You speak like a fool. Explain yourself.”

He took a step toward me and lowered his voice. Every one knows Burritt, so I need not describe him. You can all imagine how he looked when he said:

“Did you see me handling of the big box, ma’am?”

I nodded yes.

“Saw how I was the one to help carry it in, and also how I was the one to first take hold on it when he wanted it carried out?” I again nodded yes.

“Well, ma’am, that box was a heavy load to lift into the wagon, but, ma’am”—here his voice became quite sepulchral—“it wasn’t as heavy as it was when we lifted it out, and it hadn’t the same feel either. Now, what had happened to it, and where is the stuff he took out of it?”

I own I had never in my life felt creepy before that minute. But with his eyes staring at me so impressively, and his voice sunk to a depth that made me lean forward to hear what he had to say, I do declare I felt as if an icy breath had been blown across the roots of my hair.

“Burritt, you want to frighten me,” I exclaimed, as soon as I could get my voice. “The box seemed heavier to you than it did just now. There was no change in it, there could not be, or we should find something here to account for it. Remember you did not sleep last night, and lack of rest makes one fanciful.”

“It does not make a man feel stronger, though, and I tell you the box was not near so heavy to-day as yesterday. Besides, as I said before, it acted differently under the handling. There was something loose in it to-day. Yesterday it was packed tight.”

I shook my head, and tried to throw off the oppression caused by his manner. But seeing his eyes travel to the window, I looked that way too.

“He didn’t carry anything out of the door,” declared Burritt, at this moment, “because I watched it, and I know. But that window is only three feet from the ground, and I remember now that at the instant I first laid my ear to the keyhole, I heard a strange, grating sound just like that of a window being lowered by a very careful hand. Shall I look outside it, ma’am?”

I replied by going quickly to the window myself, lifting it, which I did with very little trouble, and glancing out. The familiar garden, with its path to the river, lay before me; but though I allowed myself one quick look in its direction, it was to the ground immediately beneath the window that I turned my attention, and it was here that I instantly, and to the satisfaction of both Burritt and myself, discovered unmistakable signs of disturbance. Not only was there the impression of a finely booted foot imprinted in the loose earth, but there was a large stone lying against the house which we were both confident had not been there the day before.

“He went roaming through the garden last night,” cried Burritt, “and he brought back that stone. Why?”

I shuddered instead of replying. Then remembering that I had seen the young wife well and happy only a few minutes before, felt confused and mystified beyond any power to express.

“I will have a look at that stone,” continued Burritt; and without waiting for my sanction, he vaulted out of the window and lifted the stone.

After a moment’s consideration of it he declared:

“It came from the river bank; that is all I can make out of it.”

And dropping the stone from his hand, he suddenly darted down the path to the river.

He was not gone long. When he came back, he looked still more doubtful than before.

“If I know that bank,” he declared, “there has been more than one stone taken from it, and some dirt. Suppose we examine the floor, ma’am.”

We did so, and just where the box had been placed we discovered some particles of sand that were not brought in from the road.

“What does it mean?” I cried.

Burritt did not answer. He was looking out toward the river. Suddenly he turned his eyes upon me and said in his former suppressed tone:

“He filled the box with stone and earth, and these were what we carried out and put into the wagon. But it was full when it came, and very heavy. Now, what was it filled with, and what has become of the stuff?”

It was the question then; it is the question now.

Burritt hints at crime, and has gone so far as to spend all the afternoon searching the river banks. But he has discovered nothing, nor can he explain what it was he looked for or expected to find. Nor are my own thoughts and feelings any clearer. I remember that the times are unsettled, that the spirit of revolution is in the air, and try to be charitable enough to suppose that it was treasure the young husband brought with him, and that all the perturbation and distress which I imagine myself to have witnessed in his behavior and that of his wife were owing to the purpose that they had formed of burying, in this spot, the silver and plate which they were perhaps unwilling to risk to the chances of war. But when I try to stifle my graver fears with this surmise, I recall the fearful nature of the shriek which startled me from my sleep, and repeat, tremblingly, to myself:

“Some one was in mortal agony at the moment I heard that cry. Was it the young wife, or was it—”

April 3, 1791.

IT is sixteen years since I wrote the preceding chapters of this history of mystery and crime. When the pen dropped from my hand—why did it drop? Was it because of some noise I heard?

I imagine so now, and tremble. I did not anticipate ever adding a line to the words I had written. The impulse which had led me to put upon paper my doubts concerning the two Urquharts soon passed, and as nothing ever occurred to recall this couple to my mind, I gradually allowed their name and memory to vanish from my thoughts, only remembering them when chance led me into the oak parlor. Then, indeed, I recollected their manner and my fears, and then I also felt repeated, though every time with fainter and fainter power, the old thrill of undefined terror which stopped my record of that day with the half-finished question as to who had uttered the shriek that had startled me the night before. To-day I again take up my pen. Why? Because to-day, and only since to-day, can I answer this question.

Sixteen years ago! which makes me sixteen years older. My house, too, has aged, and the oak parlor—I never refurnished it—is darker, gloomier, and more forbidding than it was then, and in truth, why should it not be? When I remember what was revealed to me a week ago, I wonder that its walls did not drop fungi, and its chill strike death through the man or woman who was brave enough to enter it. Horrible, horrible room! You shall be torn from my house if the rest of the structure goes with you. Neither I nor another shall ever enter your fatal portal again.

It was a week ago to-day that the coach from New York set down at my door a stranger of fine and quaint appearance, whose white hair betokened him to be aged, but whose alert and energetic movements showed that, if he had passed the line of fourscore, he had still enough of the fire of youth remaining to make his presence welcome in whatever place he chose to enter. As had happened sixteen years before, I was looking out of the window when the coach drove up, and, being at once attracted by the stranger’s person and manner, I watched him closely while he was alighting, and was surprised to observe what intent and searching glances he cast at the house.

“He could not be more interested if he were returning to the home of his fathers,” I murmured involuntarily to myself, and hastened to the door in order to receive him.

He came forward courteously. But after the first few words between us he turned again and gazed with marked curiosity up and down the road and again at the house.

“You seem to be acquainted with these parts,” I ventured. He smiled.

“This is an old house,” he answered, “and you are young.” (I am fifty-five.) “There must have been owners of the place before you. Do you know their names?”

“I bought the place of Dan Forsyth, and he of one Hammond. I don’t know as I can go back any further than that. Originally the house was the property of an Englishman. There were strange stories about him, but it was so long ago that they are almost forgotten.”

The stranger smiled again, and followed me into the house. Here his interest seemed to redouble.

Instantly a thought flashed through my brain.

“He is its ancient owner, the Englishman. I am standing in the presence of—”

“You wish to know my name,” interrupted his genial voice. “It is Tamworth. I am a Virginian, and hope to stay at your inn one night. What kind of a room have you to offer me?”

There was a twinkle in his eyes I did not understand. He was looking down the hall, and I thought his gaze rested on the corridor leading to the oak parlor.

“I should like to sleep on the ground floor,” he added.

“I have but one room,” I began.

“And one is all I want,” he smiled. Then, with a quick glance at my face: “I suppose you are a little particular whom you put into the oak parlor. It is not every one who can appreciate such romantic surroundings.”

I surveyed him, completely puzzled. Whereupon he looked at me with an expression of surprise and incredulity that added to the mystery of the moment.

“The room is gloomy and uninviting,” I declared; “but beyond that, I do not know of any especial claim it has upon our interest.”

“You astonish me,” was his evidently sincere reply; and he walked on, very thoughtfully, straight to the room of which we were speaking. At the door he paused. “Don’t you know the secret of this room,” he asked, giving me a very bright and searching glance.

“If you mean anything concerning the Urquharts,” I began doubtfully.

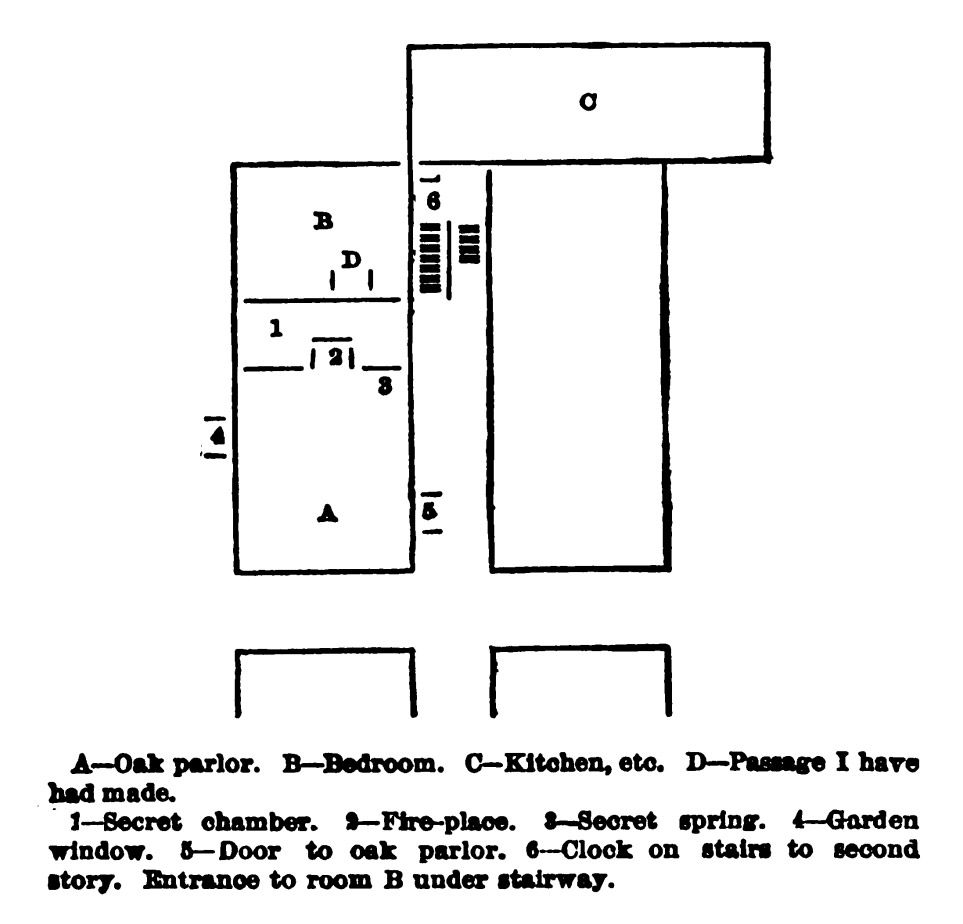

“Urquharts!” he carelessly repeated. “I do not know anything about them. I am speaking of an old tradition. I was told—let me see how long it is now—well, it must be sixteen years at least—that this house contained a hidden chamber communicating with a certain oak parlor in the west wing. I thought it was curious, and—Why, madam, I beg your pardon; I did not mean to distress you. Can it be possible that you were ignorant of this fact?—you, the owner of this house!”

“Are you sure it is a fact?” I gasped. I was trembling in every limb, but managed to close the door behind us before I sank into a chair. “I have lived in this house twenty years. I know its rooms and halls as I do my own face, and never, never have I suspected that there was a nook or corner in it which was not open to the light of day. Yet—yet it is true that the rooms on this floor are smaller than those above, this one especially.” And I cast a horrified glance about me, that reminded me, even against my will, of the searching and peculiar look I had seen cast in the same direction by Mr. Urquhart sixteen years before.

“I see that I have stumbled upon a bit of knowledge that has been kept from the purchasers of this property,” observed the old gentleman. “Well, that does not detract from the interest of the occasion. When I knew I was to pass this way, I said to myself I shall certainly stop at the old inn with the secret chamber in it, but I did not think I should be the first one to disclose its secret to the present generation. But my information seems to affect you strangely. Is it such a disturbing thing to find that one’s house has held a disused spot within it, that might have been made useful if you had known of its existence?”

I could not answer. I was enveloped in a strange horror, and was only conscious of the one wish—that Burritt had lived to help me through the dreadful hour I saw before me.

“Let us see if my information has been correct,” continued Mr. Tamworth. “Perhaps there has been some mistake. The secret chamber, if there is one, should be behind this chimney. Shall I hunt for an opening?”

I managed to shake my head. I had not strength for the experiment yet. I wanted to prepare myself.

“Tell me first how you heard about this room?” I entreated.

He drew his chair nearer to mine with the greatest courtesy.

“There is no reason why I should not tell you,” replied he, “and as I see that you are in no mood for a long story, I shall make my words as few as possible. Some years ago I had occasion to spend a night in an inn not unlike this, on Long Island. I was alone, but there was a merry crowd in the tap room, and being fond of good company, I presently found myself joining in the conversation. The talk was of inns, and many a stirring story of adventure in out-of-the-way taverns did I listen to that night before the clock struck twelve. Each man present had some humorous or thrilling experience to relate, with the exception of a certain glum and dark-browed gentleman, who sat somewhat apart from the rest, and who said nothing. His reticence was in such marked contrast to the volubility about him that he finally attracted universal attention, and more than one of the merry-makers near him asked if he had not some anecdote to add to the rest. But though he replied with sufficient politeness, it was evident that he had no intention of dropping his reserve, and it was not till the party had broken up and the room was nearly cleared that he deigned to address any one. Then he turned to me, and with a very peculiar smile, remarked:

“ ‘A dull collection of tales, sir. Bah! if they had wanted to hear of an inn that was really romantic, I could have told them—’

“ ‘What?’ I involuntarily ejaculated. ‘You will not torture me by suggesting a mystery you will not explain.’

“He looked very indifferent.

“ ‘It is nothing,’ he declared, ‘only I know of an inn—at least it is used for an inn now—which has in its interior a secret chamber so deftly hidden away in the very heart of the house that I doubt if even its present owner could find it without the minutest directions from the man who saw it built. I knew that man. He was an Englishman, and he had a fancy to make his fortune through the aid of smuggled goods. He did it; and though always suspected, was never convicted, owing to the fact that he kept all his goods in this hidden room. The place is sold now, but the room remains. I wonder if any forgotten treasures lie in it. Imagination could easily run riot over the supposition, do you not think so, sir?’

“I certainly did, especially as I imagined myself to detect in every line of his able and crafty face that he bore a closer relation to the Englishman than he would have me believe. I did not betray my feelings, however, but urged him to tell me how in a modern house, a room, or even a closet, could be so concealed as not to awaken any one’s suspicion. He answered by taking out pencil and paper, and showing me, by a few lines, the secret of its construction. Then seeing me deeply interested, he went on to say:

“ ‘We find what we have been told to search for; but here is a case where the secret has been so well kept that in all possibility the question of this room’s existence has never arisen. It is just as well.’

“Meantime I was studying the plan.

“ ‘The hidden chamber lies,’ said I, ‘between this room,’ designating one with my forefinger, ‘and these two others. From which is it entered?’

“He pointed at the one I had first indicated.

“ ‘From this,’ he affirmed. ‘And a quaint, old-fashioned room it is, too, with a wainscoting of oak all around it as high as a man’s head. It used to be called the oak parlor, and many a time has its floor rung to the tread of the king’s soldiers, who, disappointed in their search for hidden goods, consented to take a drink at their host’s expense, little recking that, but a few feet away, behind the carven chimneypiece upon which they doubtless set down their glasses, there lay heaps and heaps of the richest goods, only awaiting their own departure to be scattered through the length and breadth of the land.’

“ ‘And this house is now an inn?’ I remarked.

“ ‘Yes.’

“ ‘Curious. I should like nothing better than to visit that inn.’

“ ‘You doubtless have.’

“ ‘It is not this one?’ I suddenly cried, looking uneasily about me.

“ ‘Oh, no; it is on the Hudson River, not fifty miles this side of Albany. It is called the Happy-Go-Lucky, and is in a woman’s hands at present; but it prospers, I believe. Perhaps because she has discovered the secret, and knows where to keep her stores.’ And with a shrug of his shoulders he dismissed the subject, with the remark: ‘I don’t know why I told you of this. I never made it the subject of conversation before in my life.’

“This was just before the outbreak in Lexington, sixteen years ago, ma’am, and this is the first time I have found myself in this region since that day. But I have never forgotten this story of a secret room, and when I took the coach this morning I made up my mind that I would spend the night here, and, if possible, see the famous oak parlor, with its mysterious adjunct; never dreaming that in all these years of your occupancy you would have remained as ignorant of its existence as he hinted and you have now declared.”

Mr. Tamworth paused, looking so benevolent that I summoned up my courage, and quietly informed him that he had not told me what kind of a looking man this stranger was.

“Was he young?” I asked. “Had he a blond complexion?”

“On the contrary,” interrupted Mr. Tamworth, “he was very dark, and, in years, as old or nearly as old as myself.”

I was disappointed. I had expected a different reply. As he talked of the stranger, I had, rightfully or wrongfully, with reason or without reason, seen before me the face of Mr. Urquhart, and this description of a dark and well-nigh aged man completely disconcerted me.

“Are you certain this man was not in disguise?” I asked.

“Disguise?”

“Are you certain that he was not young, and blond, and—”

“Quite sure,” was the dry interruption. “No disguise could transform a young blood into the man I saw that night. May I ask—”

In my turn I interrupted him. “Pardon me,” I entreated, “but an anxiety I will presently explain forces another question from me. Were you and this stranger alone in the room when you held this conversation? You say that it had been full a few minutes before. Were there none of the crowd remaining besides your two selves?”

Mr. Tamworth looked thoughtful. “It is sixteen years ago,” he replied, “but I have a dim remembrance of a man sitting at a table somewhat near us, with his face thrown forward on his arms. He seemed to be asleep; I did not notice him particularly.”

“Did you not see his face?”

“No.”

“Was he young?”

“I should say so.”

“And blond?”

“That I cannot say.”

“And he remained in that attitude all the time you were talking?”

“Yes, madam.”

“And continued so when you left the room?”

“I think so.”

“Was he within earshot? Near enough to hear all you said?”

“Most assuredly, if he listened.”

“Mr. Tamworth,” I now entreated, “try, if possible, to remember one other fact. If each man present told a story that night, you must have had ample opportunity of noting each man’s face and observing how he looked. Now, of all that sat in the room, was there not one of an age not exceeding thirty-five, of fair complexion and gentlemanly appearance, yet with a dangerous look in his small blue eye, and a something in his smile that took all the merriment out of it?”

“A short but telling description,” commented my guest. “Let me see. Was there such a man among them? Really, I cannot remember.”

“Think, think. Hair very thin above the temples, mustache heavy. When he spoke he invariably moved his hands; seemed to be nervous, and anxious to hide it.”

“I see him,” was Mr. Tamworth’s sudden remark. “That description of his hands recalls him to my mind. Yes; there was such a man in the room that night. I even recollect his story. It was coarse, but not without wit.”

I advanced and surveyed Mr. Tamworth very earnestly. “The man you thought asleep—the man who was near enough to hear all the Englishman said—was he or was he not the same we have just been talking about?”

“I never thought of it before, but he did look something like him—his figure, I mean; I did not see his face.”

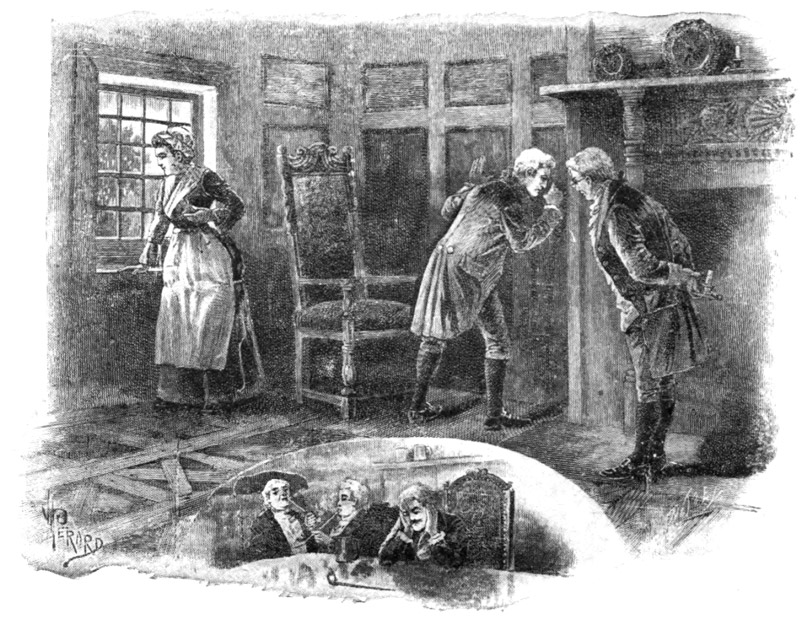

“It was he,” I murmured, with intense conviction, “and the villain—” But how did I know he was a villain? I paused and pointed to the huge mantel guarding the fireplace. “If you know how to enter the secret room, do so. Only I should like to have a few witnesses present besides myself. Will you wait till I call one or two of my lodgers?”

He bowed with great urbanity. “If you wish to make the discovery public,” said he, “I, of course, have no objection.”

But I saw that he was disappointed.

“I can never confront the secret of that room alone,” I insisted. “I must have Dr. Kenyon here at least.” And without waiting for my impulses to cool, I sent a message to the doctor’s room, and was rewarded in a moment by the appearance at the door of that excellent man.

It did not take many words for me to explain to him our intentions. We were going to search for a secret chamber which we had been told opened into the room in which we then found ourselves. As I did not wish to make any mystery of the affair, and as I naturally had my doubts as to what the room might disclose, I asked the support of his presence.

He was gratified—the doctor always is gratified at any token of appreciation—and perceiving that I had no further reason for delay, I motioned to Mr. Tamworth to proceed.

How he discovered the one movable panel in that old-fashioned wainscoting, I have never inquired. When I saw him turn toward the fireplace and lay his ear to the wall, I withdrew in haste to the window, feeling as if I could not bear to watch him, or be the first to catch a glimpse of the mysterious depths which in another moment must open before his touch. What I feared I cannot say. As far as I could reason on the subject, I had no cause to fear anything; and yet my shaking frame and unevenly throbbing heart were but the too sure tokens of an excessive and uncontrollable agitation. The view from the window increased it. Before me lay the river from whose banks sand and stone had been taken sixteen years before to replace—what? I knew no more this minute than I did then. I might know in the next. By the faint tapping that came to my ears I must—and it was this thought that sent a chill through me, and made it so difficult for me to stand. And yet why should it? Was not that old theory of ours, that the Urquharts had brought treasure in their great box, still a plausible one? Nay, more, was it not even a probable one, since we had discovered that the house held so excellent a hiding place, unknown to the world at large, but known to this man, as Mr. Tamworth’s story so plainly showed? Yes; and yet I started with uncontrollable forebodings, when I heard an exclamation of satisfaction behind me, and hardly found courage to turn around, even when I knew that an opening had been effected, and that they were only waiting for my approach to enter it.

And it took courage, both on my part and on theirs; for the air which rushed from the high and narrow slit of darkness before us was stifling and almost deadly. But in a few minutes, after one or two experiments with a lighted candle, Dr. Kenyon stepped through the opening, followed by Mr. Tamworth, and, in a long minute afterward, by myself.

Shall I ever forget my emotions as I looked about me and saw, by the lamp which the doctor carried, nothing more startling than an old oak chest in one corner, a pile of faded clothing in another, and in a third—Heavens! what is it? We all stare, and then a shriek escapes my lips as piercing and terror-stricken as any that ever disturbed those fearful shadows; and I rush blindly from the spot, followed by Mr. Tamworth, whose face, as I turn to look at him, gives me another pang of fear, so white and sick it looks in the sudden glare of day.

Worse than I had thought, worse than I had dreamed! I cannot speak, and fall into a chair, waiting in mortal terror for the doctor, who stayed some minutes behind. When his kindly but not undisturbed countenance showed itself again in the gap at the side of the fireplace, I could almost have thrown myself at his feet.

“What is it?” I gasped. “Tell me at once. Is it a man or a woman or—”

“It is a woman. See! here is a lock of her hair. Beautiful, is it not? She must have been young.”

I stared at it like one demented. It was of a peculiar reddish-brown, with a strange little kink and curl in it. Where had I seen such hair before? Somewhere. I remembered perfectly how the whole bright head looked with the firelight playing over it. Oh, no, no, no, it was not that of Mrs. Urquhart. Mrs. Urquhart went away from this house well and happy. I am mad, or this strand of gleaming hair is a dream. It is not her head it recalls to me, and yet—my soul, it is!

The doctor, knowing me well, did not try to break the silence of that first grewsome minute. But when he saw me ready to speak, he remarked:

“It is an old crime, perpetrated, probably, before you came into the house. I would not make any more of it than you can help, Mrs. Truax.”

I scarcely heeded him.

“Is there no bit of clothing or jewelry left upon her by which we might hope to identify her?” I asked, shuddering, as I caught Mr. Tamworth’s eye, and realized the nature of the doubts I there beheld.

“Here is a ring I found upon the wedding finger,” he replied. “It was doubtless too small to be drawn off at the time of her death, but it came away easily enough now.”

And he held out a plain gold circlet which I eagerly took, looked at, and fell at their feet as senseless as a stone.

On the inner surface I had discovered this legend:

E. U. to H. D. Jan. 27, 1775.

Never have I felt such relief as when, upon my resuscitation, I remembered that I had put upon paper all the events and all the suspicions which had troubled me during that fatal night of January the 28th, sixteen years before. With that in my possession, I could confront any suspicion which might arise, and it was this thought which lent to my bearing at this unhappy time a dignity and self-possession which evidently surprised the two gentlemen.

“You seem more shocked than astonished,” was Mr. Tamworth’s first remark, as, mistress once more of myself, I led the way out of that horrible room into one breathing less of death and the charnel house.

“You are right,” said I. “Mysteries which have troubled me for years are now in the way of being explained by this discovery. I knew that something either fearful or precious had been left in the keeping of this house or grounds; but I did not know what this something was, and least of all did I suspect that its hiding place was between walls whose turns and limitations I thought I knew as well as I do the paths of my garden.”

“You speak riddles,” Dr. Kenyon now declared. “You knew that something fearful or precious had been left in your house—”

“Pardon me,” I interrupted; “I said house or grounds. I thought it was in the grounds, for how could I think that the house could, without my knowledge, hold anything of the nature I have just suggested?”

“You knew, then, that a person had been murdered?”

“No,” I persisted, with a strange calmness, considering how agitated I was, both by my memories and the fears I could not but entertain for the future; “I know nothing; nor can I, even with the knowledge of this discovery, understand or explain what took place in my house sixteen years ago.”

And in a few hurried words I related the story of the mysterious couple who had occupied that room on the night of January 27, 1775.

They listened to me as if I were repeating a fairy tale, and as I noted the sympathizing air with which Dr. Kenyon tried to hide his natural incredulity, I again congratulated myself that I had been a weak enough woman to keep an account of the events which had so impressed me.

“You think I am drawing upon my imagination,” I quietly remarked, as silence fell upon my narration.

“By no means,” the doctor began, hurriedly; “but the details you give are so open to question, and the conclusions you expect us to draw from them are so serious, that I wish, for your own sake, we had heard something of the Urquharts, and your doubts and suspicions in their regard, before we had made the discovery which points to death and crime. You see I speak plainly, Mrs. Truax.”

“You cannot speak too plainly, Doctor Kenyon; and my opinion so entirely coincides with yours that I am going to furnish you with what you ask.” And without heeding their looks of astonishment, I rang the bell for one of the girls, and sent her to a certain drawer in my desk for the folded paper which she would find there.

“Here!” I exclaimed, as the paper was brought, “read this, and you will soon see how I felt about the Urquharts on the evening of the day they left us.”

And I put into their hands the record I had made of that day’s experience.

While they were reading it, I puzzled myself with questions. If this body which we had just found sepulchered in my house was, as the initials in the ring seemed to declare, that of Honora Urquhart, who was the woman who passed for her at the time of the departure of this accused couple from my doors? I was with them, and saw the lady, and supposed her to be the same I had entertained at my table the night before. But then I chiefly noted her dress and height, and did not see her face, which was hidden by her veil, and did not hear her voice beyond the short and somewhat embarrassed laugh she gave at some little incident which had occurred. But Hetty had seen her, and had even received money from her hand; and Hetty could not have been deceived, nor was Hetty a girl to be bribed. How was I, then, to understand the matter? And where, in case another woman had taken Mrs. Urquhart’s place, had that woman come from?

I thought of the low window, and the ease with which any one could climb into it; and then, with a flash of startled conviction, I thought of the huge box.

“Great heavens!” I ejaculated, feeling the hair stir anew on my forehead. “Can it be that he brought her in that? That she was with them all the time, and that the almost hellish tragedy to which this ring points was the scheme of two vile and murderous lovers to suppress an unhappy wife that stood in the way of their desires?”

I could not think it. I could not believe that any man could be so void of mercy, or any woman so lost to every instinct of decency, as to plan, and then coolly carry out to the end, a crime so unheard of in its atrocity. There must be some other explanation of the facts before us. Why, the date in the ring is enough. If that speaks true, the marriage between Edwin Urquhart and the gentle Honora was but a day old, and even the worst of men take time to weary of their wives before they take measures against them. Yet, the look and manner of the man! His affection for the box, and his manifest indifference for his wife! And, lastly, and most convincing of all, this awful token in the room beyond! What should I, what could I think!

At this point in my surmises I grew so faint that I turned to Dr. Kenyon and Mr. Tamworth for relief. They had just finished my record of the past, and were looking at each other in surprise and horror.

“It surpasses the most atrocious deeds of the middle ages,” quoth Mr. Tamworth.

“In a country deemed civilized,” finished the doctor.

“Then you think,” I tremblingly began—

“That you have harbored two demons under your roof, Mrs. Truax. There seems to be no doubt that the woman who went away with Mr. Urquhart was not the woman who came with him. She lies here, while the other—”

He paused, and Mr. Tamworth took up the word.

“It seems to have been a strangely triumphant piece of villainy. The woman who profited by it must have had great self-control and force of character. Don’t you think so, doctor?”

“Unquestionably,” was the firm reply.

“You do not say how you account for her presence here,” I now reluctantly intimated.

“I think she was hidden in the great box. It was large enough for that, was it not, Mrs. Truax?”

I nodded, much agitated.

“His care of it, his call for a supper, the change in its weight, and the fact that its contents were of a different character in going than coming, all point to the fact of its having been used for the purpose we intimated. It strikes one as most horrible, but history furnishes us with precedents of attempts equally daring, and if the box was well furnished with holes—did you notice any breathing places in it?”

“No,” I returned; “but I did not cast two glances at the box. I was jealous of it, for the young wife’s sake, though, as God knows, I had little idea of what it contained, and merely noticed that it was big and clumsy, and capable of holding many books.”

“Yet you must have noticed, even in a cursory glance, whether its top or sides were broken by holes.”

“They were not, but—”

“But what?”

“I do remember, now, that he flung his traveling-cloak across it just as the men went to lift it from the wagon, and that the cloak remained upon it all the time it was in their hands, and until after we had all left the room. But it was taken away later, for when I went in the second time, I saw it lying across the chair.”

“And the box?”

“Was hidden by the foot of the bed behind which he had dragged it.”

“And the cloak? Was it over the box when it went out?”

“No; but I have thought since we have been talking, that the box might have been turned over after its occupant left it. The holes, if there were any, would thus be on the bottom, and would escape our detection.”

“Very possible, but the sand with which we supposed the box had been filled would have sifted through.”

“Not if a good firm piece of stuff was laid in first, and there were plenty of such in the secret chamber.”

“That is true. But Burritt, you write, was listening at the door, and yet you mention no remarks of his concerning any noises heard by him from within. And noise must have been made if this was done, as it must have had to be done after the tragedy.”

“I know I do not,” was the hurried reply. “But Burritt probably did not remain at the door all the time. There is a window seat at the end of the corridor, and upon it he probably lolled during the few hours of his watch. Besides, you must remember that Burritt left his post some time before daylight. He had his duties to attend to, some of which necessitated his being in the stables by four o’clock, at least.”

“I see; and so the affair prospered, as most very daring deeds do, and they escaped without suspicion, or rather without suspicion pointed enough to lead to their being followed. I wonder where they escaped to, and if in all the years that have elapsed, they have for one moment imagined that they were happy.”

“Happy!” was my horrified exclamation. “Oh, if I could find them! If I could drag them both to this room and make them keep company with their victim for a week, I should feel it too slight a retribution for them.”

“Heaven has had its eye upon them. We have been through fearful crises since that day, and much unrighteous as well as righteous blood has been shed in this land. They may both be dead.”

“I do not believe it,” I muttered. “Such wretches never die.” Then, with a renewed remembrance of Hetty, I remarked: “Curses on the duties that kept me out of this room on that fatal morning. Had I seen the woman’s face, this horrid crime would at least been spared its triumph. But I was obliged to send Hetty, and she saw nothing strange in the woman, though she received money from her hand, and—”

“Where is Hetty?” interrupted the doctor.

“She is married, and lives in the next town.”

“So, so. Well, we must hunt her up to-morrow, and see what she has to say about the matter now.”

But we soon found ourselves too impatient to wait till the morrow, so after we had eaten a good supper in a cheerful room, Dr. Kenyon mounted his horse, and rode away to the farm house where Hetty lived. While he was gone, Mr. Tamworth summoned up courage to re-enter that cave of horror, and bring out the contents of the oak chest we had seen there. These were mostly stuffs in a more or less good state of preservation, and all the assistance they lent to the understanding of the tragedy that mystified us was the fact that the chest contained nothing, nor the room itself, of sufficient substance to help the wicked Urquhart in giving weight to the box which he had emptied of its living freight. This is doubtless the reason he resorted to the garden for the sand and stone he found there.

Dr. Kenyon returned about midnight, and was met at the door by Mr. Tamworth and myself.

“Well?” I cried, in great excitement.

“Just as I supposed,” he returned. “She did not see the lady’s face either. The latter was in bed, and the girl took it for granted that the arm and hand which reached her out a silver piece from between the bed curtains were those of Mrs. Urquhart.”

“My house is cursed!” was my sudden exclamation. “It has not only lent itself to the success of the most demoniacal scheme that ever entered into the heart of man, but it has kept its secret so long that all hope of explaining its details or reaching the guilty must be abandoned.”

“Not so,” quoth Mr. Tamworth. “Though an old man, I dedicate myself to this task. You will hear again of the Urquharts.”

May 5, 1791.

HOW fearful! To hear a spade in the night and know that this spade is digging a grave! I sit at my desk and listen to hear if any one in the house has been aroused or is suspicious, and then I turn to the window and try to pierce the gloom to see if anything can be discerned, from the house, of the grewsome act now being performed in the garden. For after much consultation and several conferences with the authorities, we have decided to preserve from public knowledge, not only the secret of the room hidden in my house, but of the discovery which has lately been made there. But while much harm would accrue to me by revelations which would throw a pall of horror over my inn, and make it no better than a place of morbid curiosity forever, the purposes of justice would be rather hindered than helped by a publicity which would give warning to the guilty couple, and prevent us from surprising them in the imagined security which the lapse of so many years must have brought them.

And so a grave is being dug in the garden, where, at the darkest hour of night, the remains of the sweet and gentle bride are to be placed without tablet or mound.

Meanwhile do there hide in any part of this wicked world two hearts which throb with unusual terrors this night? Or does there pass across the mirror of a guilty memory any unusual shapes of horror prognostic of detection and coming punishment? It would comfort my uneasy heart to know; for the spirit of vengeance has seized upon me, and my house will never seem washed of its stain, or my conscience be quite at rest as to the past, till that vile man and woman pay, in some way, the penalty of their crime.

That we know nothing of them but their names lends an interest to their pursuit. The very difficulty before us, the hopelessness almost of the task we have set ourselves, have raised in me a wild and well-nigh superstitious reliance on Providence and the eternal justice, so that it seems natural for me to expect aid even from such sources as dreams and visions, and make the inquiry in which I have just indulged the reasonable expression of my belief in the mysterious forces of right and wrong, which will yet bring this long triumphant, but now secretly threatened, pair to justice.

Dr. Kenyon, who is as practical as he is pious, smiles at my confidence; but Mr. Tamworth neither mocks nor frowns. He has shouldered the responsibility of finding this man, and has often observed, in his long life, that a woman’s intuitions go as far as a man’s reasoning.

To-morrow he will start upon his travels.

June 12, 1791.

It is foolish to put every passing thought on paper, but these sheets have already served me so well that I cannot resist the temptation of making them the repositories of my secret fears and hopes. Mr. Tamworth has been gone a month, and I have heard nothing from him. This is all the more difficult to bear that Dr. Kenyon also has left me, thus taking from my house all in whom I can confide or to whom I can talk. For I will not place confidence in servants, and there are no guests here at present upon whose judgment I can rely concerning even a lesser matter than this which occupies all my thoughts.

I must talk, then, to thee, unknown reader of these lines, and declare on paper what I have said a thousand times to myself—what a mystery this whole matter is, and how little probability there is of our ever understanding it! Why was it that Edwin Urquhart, if he loved one woman so well that he was willing to risk his life to gain her, would subject himself to the terrors which must follow any crime, no matter how secretly performed, by marrying a woman he must kill in twenty-four hours? Marriages are not compulsory in this country, and any one must acknowledge that it would be easier for a strong man—and he certainly was no weakling—to refuse a woman at the nuptial altar than to undertake and carry out a scheme so full of revolting details and involving so much risk as this which we have been forced to ascribe to him.

Then the woman, the unknown and fearful creature who had allowed herself to be boxed up and carried, God knows, how many fearful miles, just for the purpose of assuming a position which she seemingly might have obtained in ways much less repulsive and dangerous! Was it in human nature to go through such an ordeal, and if it were, what could the circumstances have been that would drive even the most insensible nature into such an adventure! I question, and try to answer my own inquiries, but my imagination falters over the task, and I am no nearer to the satisfaction of my doubts than I was in the harrowing minute when the knowledge of this tragedy first flashed upon me.

I must have patience. Mr. Tamworth must write to me soon.

August 10, 1791.

News, news, and such news! How could I ever have dreamed of it! But let me transcribe Mr. Tamworth’s letter:

To Mrs. Clarissa Truax,

Mistress of the Happy-go-lucky Inn:

Respected Madam: After a lengthy delay, occupied in researches, made doubly difficult by the changes which have been wrought in the country by the late conflict, I have just come upon a fact that has the strongest bearing upon the serious tragedy which we are both so interested in investigating. It is this:

That every year the agent of a certain large estate in Albany, N. Y., forwards to France a large sum of money, for the use and behoof of one Honora Quentin Urquhart, daughter of the late Cyrus Dudleigh, of Albany, and wife of one Edwin Urquhart, a gentleman of that same city, to whom she was married in her father’s house on January 27, 1775, and with whom she at once departed for France, where she and her husband have been living ever since.

Thus by chance, almost, have I stumbled upon an explanation of the tragedy we found so inexplicable, and found that clew to the whereabouts of the wretched pair which is so essential to their apprehension and the proper satisfaction of the claims of justice.

With great consideration I sign myself,

Your obedient servant,

Anthony Tamworth.

August 11, 8 o’clock.

I was so overwhelmed by the above letter that I found it impossible at the time to comment upon it. To-day it is too late, for this morning a packet arrived from Mr. Tamworth containing another letter of such length that I am sure it must be one of complete explanation. I burn to read it, but I have merely had time to break the seal and glance at the first opening words. Will my guests be so kind as to leave me in peace to-night, so that I may satisfy a curiosity which has become almost insupportable?

Midnight.

No time to-night; too tired almost to write this.

August 12.

The packet is read. I am all of a tremble. What a tale! What a— But why encumber these sheets with words of mine? I will insert the letter and let it tell its own portion of the strange and terrible history which time is slowly unrolling before us.

To Mrs. Clarissa Truax,

of the Happy-go-lucky Inn:

Respected Madam: Appreciating your anxiety, I hasten to give you the particulars of an interview which I have just had with a person who knew Edwin Urquhart. They must be acceptable to you, and I shall make no excuse for the length of my communication, knowing that each detail in the lives of the three persons connected with this crime must be of interest to one who has brooded upon the subject as long as you have.

The person to whom I allude is a certain Mark Felt, a most eccentric and unhappy being now living the life of a recluse amid the forests of the Catskills. I became acquainted with his name at the time of my first investigation into the history of the Dudleigh and Urquhart families, and it was to him I was referred when I asked for such particulars as mere neighbors and public officials found it impossible to give.

I was told, however, at the same time, that I should find it hard to gain his confidence, as for sixteen years now he had avoided the companionship of men, by hiding in the caves and living upon such food as he could procure through the means of gun and net. A disappointment in love was said to be at the bottom of this, the lady he was engaged to having thrown herself into the river at about the time of the marriage of his friend.

He was, notwithstanding, a good-hearted man, and if I could once break through the reserve he had maintained for so many years, they thought I would be able to surprise facts from him which I could never hope to reach in any other way.

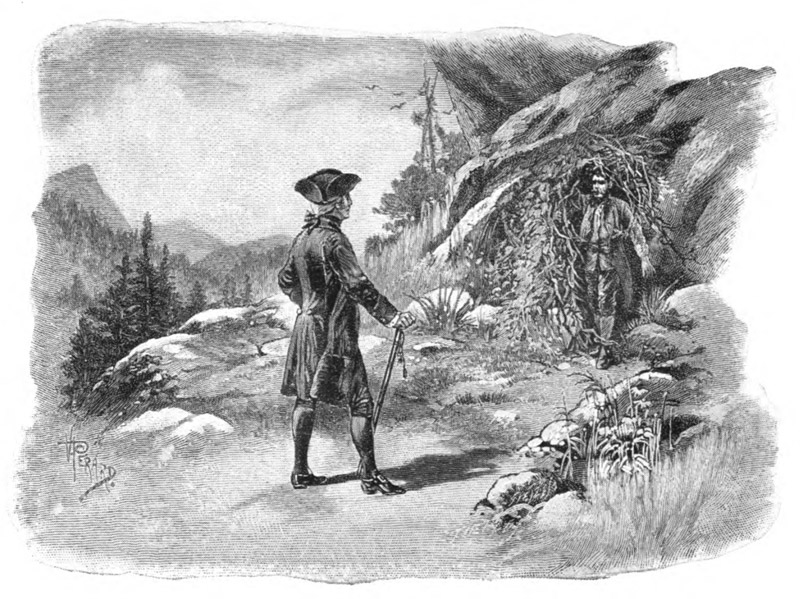

Interested by these insinuations, and somewhat excited, for an old man, at the prospect of bearding such a lion in his den, I at once made up my mind to seek this Felt; and accordingly one bright day last week crossed the river and entered the forest. I was not alone. I had taken a guide who knew the location of the cave which Felt was supposed to inhabit, and through his efforts my journey was made as little fatiguing as possible. Fallen brambles were removed from my path, limbs lifted, and where the road was too rough for the passage of such faltering feet as mine, I found myself lifted bodily, in arms as strong and steadfast as steel, and carried like a child to where it was smoother.

Thus I was enabled to traverse paths that at first view appeared inaccessible, and finally reached a spot so far up the mountain side that I gazed behind me in terror lest I should never be able to return again the way I had come. My guide, seeing my alarm, assured me that our destination was not far off, and presently I perceived before me a huge overhanging cliff, from the upper ledges of which hung down a tangle of vines and branches that veiled, without wholly concealing, the yawning mouth of a cave.

“That is where the man we are seeking lives, eats, and sleeps,” quoth my guide, as we paused for a moment to regain our breath. And immediately upon his words, and as if called forth by them, we perceived an unkempt and disheveled head slowly uprear itself through the black gap before us, then hastily disappear again behind the vines it had for a moment disturbed.

“I will encounter him alone,” I thereupon declared; and leaving the guide behind me, I pushed forward to the cliff, and pausing before the entrance of the cave, I called aloud:

“Mark Felt, do you want to hear news from your friend Urquhart?”

For a moment all was still, and I began to fear that my somewhat daring attempt had failed in its effect. But this was only for an instant, for presently something between a growl and a cry issued from the darkness within, and the next moment the wild and disheveled head showed itself again, and I heard distinctly these words:

“He is no friend of mine, your Edwin Urquhart.”

“Then,” I returned, without a moment’s hesitation, “do you want to hear news of your enemy?—for I have some, and of the rarest nature, too.”

The wild eyes flashed as if a flame of fire had shot from them, and the head that held them advanced till I could see the whole bearded countenance of the man.

“Is he dead?” he asked, with an eagerness and underlying triumph in the voice that argued well for the presence of those passions upon the rousing of which I relied for the revelations I sought.

“No,” said I, “but death is looking his way. With a little more knowledge of his early life and a little more insight into his character at the time he married Honora Dudleigh, the law will have so firm a hold upon him that I can safely promise any one who longs to see him pay the penalty of his evil deeds a certain opportunity of doing so.”

The vines trembled and suddenly parted their full length, and Mark Felt stepped out into the sunshine and confronted me. What he wore I cannot say, for his personality was so strong I received no impression of anything else. Not that he was tall or picturesque, or even rudely handsome. On the contrary, he was as plain a man as I had ever seen, with eyes to which some defect lent a strange, fixed glare, and a mouth whose under jaw protruded so markedly beyond the upper that his profile gave you a shock when any slight noise or stir drew his head to one side and thus revealed it to you. Yet, in spite of all this, in spite of tangled locks and a wide, rough beard, half brown, half white, his face held something that fixed the attention and fascinated the eye that encountered it. Did it lie in his eyes? How could it, with one looking like a fixed stone of agate and the other like a rolling ball of fire? Was it in his smile? How could it be when his smile had no joy in it, only a satisfaction that was not of good, but evil, and promised trouble rather than relief or sympathy? It must be in the general expression of his features, which seemed made only to mirror the emotions of a soul full of vitality and purpose—a soul which, if clouded by wrongs and embittered by heavy memories, possessed at least the characteristic of force and the charm of an unswerving purpose.

He seemed to recognize the impression he had made, for his lips smiled with a sort of scornful triumph before he said:

“These are peculiar words for a stranger. May I ask your name and whose interests you represent?”