a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

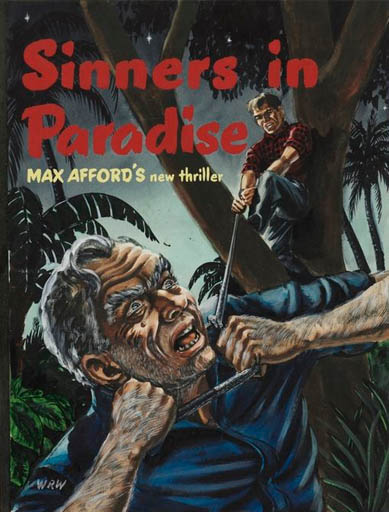

Title: Sinners in Paradise Author: Max Afford * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1501141h.html Language: English Date first posted: October 2015 Most recent update: November 2015 Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Part One.

Decision

Part Two. Dilemma

Part Three. Death

Part Four. Discovery

"You know, Robert," said Jane Morte reflectively, "I think there's something very odd about this ship."

Her husband, stretched out on a gaily coloured mattress on the sports deck, turned lazily.

"Odd, my dear?"

"Definitely. Don't you agree?"

Morte sat up, thin hands clasped about his knees. "I suppose you're still thinking of that poor invalid?"

"Surely," persisted Jane, "you must be curious about her?"

Robert shook his head. "Not me! I'm on holiday. I'm finished with mysteries."

"Ah!" Jane pounced on the word. "Then you do admit that Miss Harland is a mystery?"

Morte shrugged. Rising, he crossed to the ship's rail. From this elevated position he could see the folds of softly hissing foam, curving back in long furrows from the prow of the Medusa.

How different, he mused, from the setting of their first sight of Miss Harland, twenty-four hours ago.

August had ushered in a winter of blue skies and warm sunshine, but with the first days of September the weather had changed. Then came the rains, deluging and buffeting the city, converting the streets to shining mirrors and laying a leaden dullness over the waters of the harbour. It said much for the M.V. Medusa that even on such a day she contrived to look like a newly painted toy as she lay at anchor in Darling Harbour. A ten-thousand-ton freighter, fitted with every possible comfort, she was taking twelve selected passengers. At their first view of the ship, so clean, so trim, so obviously disdainful of the weeping skies she was so soon to leave, any qualms Robert may have held about this sudden enterprise vanished.

His publisher, Hammond, was there to wish them farewell. A personal friend of the Medusa's skipper, Hammond had been able to arrange almost last-minute bookings for the Mortes. Robert and Jane were early arrivals; it was almost an hour before the first of the other passengers made their appearance.

Then a long black car, luxurious to the point of ostentation, nosed its way to the wharf gates. A uniformed chauffeur alighted and held open the door. First to appear was a young man, broad of shoulder, lithe of step, and belted into a camel-hair overcoat. Raising an umbrella, the stranger assisted his companion from the car. This was a woman, befurred and bejewelled, a woman whose heavily made-up face merely emphasised her middle age. She walked stiffly on high-heeled shoes, clinging tightly to her companion's arm as they negotiated the gangplank. As they moved along the deck, Jane had turned to Hammond.

"Do you know those people?"

"Only by hearsay," the publisher had replied. "Mrs. Harriet Sheerlove and her nephew. Canadians—filthy with money and doing a world tour." Then, noting the expression on Jane's face, he added, "They won't worry you, Mrs. Morte." Robert remembered he had the impression Hammond was about to add something more; instead, he seemed to swing off at a tangent. "Captain Robertson tells me we're waiting for Miss Harland and Dr. Kingsley. This woman's a convalescent, I believe. Some months ago she was mixed up in a rather nasty car accident. It's played the very devil with her nerves. The skipper tells me she's taken the private suite with the glass sun-balcony."

It was then that the second car made its appearance. Leaning on the rail, closing his eyes against the glitter of the sun, Robert could recall every detail of their first glimpse of Leila Harland.

Leaning on the arm of a middle-aged man, a figure walked the dock slowly and hesitantly, as though every movement was painful. A small grey figure buttoned into a thick coat and muffled about the face with a silken scarf. Dr. Kingsley—for even at this distance the man's profession was stamped upon him—guided his charge solicitously up the gangplank.

They had cleared Sydney Heads two days later. A very quiet sailing.

That was twenty-four hours ago. Twenty-four hours in which their world was transformed from grey to blue, and soon the Queensland coast lay shadowy and vague on the far horizon. Robert had retired early that night. Next morning he rose with a feeling of freedom such as he had not known for years. He was on holiday, with nothing in his surroundings to remind him of the tedium of the typewriter.

But Jane, knitting industriously on the sun-deck on their first morning out, was not to be rebuffed by silence.

"Robert..."

He sighed a little. "Yes, dear?"

"Do you really believe Mr. Redmond is Mrs. Sheerlove's nephew?"

"I've never given it a thought, Jane."

Mrs. Morte wound a strand of wool in her fingers. "He's almost absurdly decorative, isn't he?"

Robert turned toward the far end of the deck, where Earl Redmond lay sprawled in the sun, naked except for a pair of abbreviated shorts. Even at that distance, the young man seemed conscious of scrutiny. He stirred, then, waving a brown hand, rose to his feet. This sudden friendly salute surprised Robert. Since coming on board, Redmond had made little effort to cultivate any society other than that of his aunt.

Now he was walking toward them. Morte noticed he was carrying a book, the dust-cover of which was very familiar.

Redmond grinned as he approached. "So we've got a real live author on board?" He waved the volume. "That steward guy down in the library gave me this. You know, it's kinda interesting."

"I'm glad you like it," Robert said civilly.

"Why not? I'm no highbrow," said Mr. Redmond candidly. "Me, I'm a sucker for this cheap blood-and-thunder stuff."

Jane said sweetly, "My husband has a very wide lowbrow clientele, you know."

"Guess I just can't wait to tell Hattie about this," Redmond said. "She collects celebrities. Back there in Toronto, our place was always knee-deep in them."

A shrill cry cut into the conversation. "Earl! You foolish, headstrong boy! Just you come and put on your robe at once. Do you want to catch your death by sunstroke?"

At the top of the companionway stood Mrs. Harriet Sheerlove, a thick towelling dressing-gown over her arm. Mrs. Sheerlove, her plump, aging body encased in green slacks, with a vivid yellow sweater outlining her ample breasts and thick arms.

"Earl!" she squeaked. "You come right here this minute!"

Redmond smiled with a flash of white teeth. "No, Hattie. You come here. I've made a swell discovery." Robert watched as Mrs. Sheerlove pattered obediently across the deck. The brilliant semi-tropic light dealt harshly with this woman, revealing the obviously dyed golden hair and pitilessly outlining the mask of rouge and powder.

Redmond thrust out an arm and drew her into the group. "What d'you know, Hattie? Mr. Morte here's written fifteen books."

"Really, now!" But the ejaculation was mechanical. Jane, watching carefully, had the impression that the woman was abruptly disconcerted. Then she smiled, and her next remark came a shade too quickly. "There, now! I always said you were a Personality, Mr. Morte! I said it to Earl the first few hours out—didn't I, Earl honey?"

Redmond was smiling. "You said you were sure the Mortes must be important, because they were so almighty high-hat to everyone."

"Earl!" His aunt wheeled on him. "You just love to embarrass me, Earl! I could have died right there and then about what you said to Dr. Kingsley last night."

"Gosh! When I was trying to be sociable—"

"Sociable!" Mrs. Sheerlove's plump face was pink. Again she faced the Mortes. "Do you know what he did? Went straight up to the doctor and asked if Miss Harland would join in a game of progressive ping-pong!"

Robert said mildly, "Scarcely a remark in the best of taste..."

"There—you see?" She flung this remark at her unabashed nephew, then addressed the Mortes again. "But the doctor took it so nicely. Just smiled and shook his head. But Earl should be downright ashamed, making fun of a poor invalid like that!" Abruptly, Mrs. Sheerlove veered off at a tangent. "Have you seen her this morning?"

Jane put down her knitting. "Only for a few minutes. As I came out on deck she was sitting behind the windows of the sun-balcony. But the moment she saw me she moved away."

Redmond said casually, "Kinda elderly dame, isn't she?"

"I can't tell you," Jane said levelly. "Her face and head were covered entirely by a grey silk scarf."

No one spoke. In the pause, the gentle throb of the engines and the rush of water beat strongly in their ears. The silence was broken by Mrs. Sheerlove, who held out the bathrobe almost appealingly.

"Earl, dear, do put this on," she begged.

"Nuts!" snapped her nephew. "For Pete's sake, Hattie—don't fuss so! If you want to nurse someone, get yourself a post with that Harland dame."

"Now, honey..." began Mrs. Sheerlove, but the young man cut her short.

"What's wrong with her, anyway? No one should be stuck away behind glass like a goldfish in a bowl. What that dame wants is open air and sunshine—and plenty of it."

A voice spoke from behind them: "Perhaps I am more qualified to judge than you, Mr. Redmond."

Dr. Ralph Kingsley had approached the little group so quietly that his appearance remained unnoticed until he spoke. Jane smiled and Robert nodded toward an empty deck-chair. Their acquaintance with this thin-faced, soft-spoken physician had begun on the previous evening, when they found him seated at their table. Kingsley apologised for the error, and later, in the lounge, this introduction led to further conversation. The Mortes had liked Dr. Kingsley on sight. There was about this man a quiet assurance that commanded respect, an authority leavened with gentle humour and good breeding.

Kingsley was smiling as he seated himself.

"I'm rather glad you brought up the subject," he said genially. "Because there's nothing at all sinister in my patient's seclusion. Quite recently she was concerned in a car accident which scarred her face. In consequence, she has had to undergo plastic surgical treatment. All this has left Miss Harland in a highly nervous condition. I prescribed this journey as a means of recuperation. Under the circumstances, a crowded passenger ship was impossible."

The Canadian coloured; then abruptly he rose and ran his fingers through his thick hair. "I'm hot as a bride's breath!" he announced. "I'm taking myself into the pool."

They watched him as he moved down the companionway. Mrs. Sheerlove, after a quick, nervous, almost apologetic nod to the others, followed him. Jane broke the silence.

"This trip takes five weeks, I believe?"

Robert looked at her in surprise. "Yes, but—"

"Oh, I'm not being irrelevant," she assured him. "But I'm just wondering if I can take five long weeks of Mr. Redmond!"

Kingsley produced a pipe and tobacco-pouch. "You're going to be spared that, Mrs. Morte. Those two people are leaving the ship at Paradise Island, in the Barrier Reef. They're staying a month before completing a tour of Australia."

Robert frowned. "Then this freighter is stopping off the Queensland coast?" And, as Kingsley nodded, he went on, "But surely that's most unusual?"

"Not with the Medusa." The doctor puffed for a moment. "Ever heard of Arthur Burton?"

"Of Burton and Skinner?" Robert nodded. "Of course. They're the largest firm of manufacturing engineers in this country."

"They also happen to own the Medusa. At the moment, she's laden to Plimsoll line with Burton cargo for Liverpool." A gust of wind scattered sparks, and Kingsley cupped his hands around the bowl of his pipe. "Burton and Skinner are holidaying on Paradise Island with Burton's daughter, his secretary, and some kind of foreign man-servant. We're laying off to pick them up." He paused and glanced at Robert in a half-puzzled way. "But surely you know all about these arrangements?"

Morte said drily, "My wife and I left in rather a hurry. I was writing up till the last minute. I was literally a writing-machine, geared to turn out so many thousands of words each day. Each hour of my time was planned to produce the maximum of writing energy—until a week ago."

"And then the machine broke down?"

"Oh, no," said Jane Morte suddenly. "Margaret Vane did that."

Kingsley's tone was puzzled. "I seem to have heard that name somewhere..."

"One of the best-known radio actresses in Australia," Morte explained. "Margaret Vane was playing lead in my serial, The Golden Serpent. A week ago the studio rang me to say that she'd had a complete mental collapse and had to rest for six months in a nursing home. As the serial was tailored for this woman's personality, it had to be stopped." Robert smiled. "It also meant that, for the first time in years, I was free from my most binding commitment."

The ship's bell chimed eight times and the sound roused the doctor.

"Ever been up this way before?" he asked.

Morte shook his head. "There's never been time. A visit to the North Queensland coast and the Barrier Reef Islands was something that was always just ahead."

The doctor shook his head slowly. "Don't expect too much, Morte. Oh, yes—the islands were glamorous enough once. But that was long before the place became a fashionable tourist resort."

Jane Norte asked casually, "You seem to know the coast, doctor?"

"Pretty well. I was stationed at Cairns during the war." He rose and picked up his sun-glasses: "And now I really must take a look at my patient."

The first of what was later—much later—to become known as the Curious Incidents in the Case occurred shortly after the conversation on the sports deck.

Robert had returned to their cabin alone to change for lunch. When Jane entered, she found her husband engrossed in a map of the Queensland coast, mounted behind glass on the wall. He turned at her approach.

"Have you noticed this, Jane? It's a regular pirate chart! Just look at these names. Silversmith Island—Anchorsmith—Blacksmith, Anvil, Hammer, Forge and Bellows! It's enough to make one believe in the stories of buried treasure-chests!"

"Talking of pirates and unpleasant people like that," said Mrs. Morte tartly, "we've had an invitation from Mr. Redmond. He's asked us for drinks in his cabin." She sat down on her bed. "I'm not going!"

"Why not?"

"First, because liquor before lunch always makes me sleepy, but mainly because I don't like the young gentleman's company."

Morte grinned at his reflection in the long mirror.

"In that case, I'll skip the invitation, too."

"You'll do no such thing," she retorted. "It's going to look much too pointed if we both ignore the man. After all, we are passengers on the same ship." She crossed and, rather surprisingly, kissed him.

"Run along, my dear, and enjoy yourself."

Morte found Redmond's cabin more or less a replica of their own comfortable quarters.

He was last to arrive. Mrs. Sheerlove, Dr. Kingsley and Captain Robertson were gathered in a group near the table. They nodded at his entrance. Redmond, in his dressing-gown, was surprised to find Morte alone.

"Where's your wife?" he asked. Robert murmured excuses regarding a headache and tried to ignore the sudden glint of malicious amusement which flickered in the Canadian's brown eyes. "Guess that's bad luck," he said casually. "Now, mister. What are you drinking?"

"A small whisky," Morte said. "And I mean small."

"And what do you want to kill it with?"

"Is there any soda?"

This request caused a mild complication. The host delved into the cabinet and clattered bottles impatiently. Then he straightened.

"Hattie, pet. What d'you know? I'm clean out of soda..."

"Make it water," began Robert, but the solicitous Mrs. Sheerlove gave a sharp squeak of protest. "No, no, no! There's plenty of soda. It's all in my cabin." She moved toward the door and they heard her pattering down the corridor.

An expression of impatience crossed Redmond's face. He reached for the water-jug and splashed Robert's glass. "Have this while we're waiting," he invited, and then raised his own drink.

"To crime!" he said.

He gulped the liquor almost in a mouthful. Captain Robertson, by contrast, sipped at his glass in a manner almost ladylike. In appearance, the skipper of the Medusa was a small, pink man, bald as an egg. As if in compensation, Nature had endowed him with the bushiest pair of eyebrows Robert had ever seen.

It was Kingsley who gathered Morte into the conversation. "We're still on the subject of the Barrier Reef Islands," he explained. "The skipper was telling me something about Paradise—the island we make some time tomorrow."

"Charming spot. Quite unspoilt. Well off the beaten track."

Later Robert was to become accustomed to Captain Robertson's staccato conversation, but now he had to strain to catch these telegraphic monosyllables. He drew his brows together and squinted at Robert.

"Paradise. Very well named. Wish we were staying there longer!"

"And just," inquired Morte, "how long do we stay?"

"That depends. Three days. Maybe a week. Owners' wishes, you know. Not mine." He turned to Kingsley. "Been there yourself, I believe?"

The other shook his head. "I know of the island only by hearsay. There was rather a nasty fatality there during the war. They flew the victim to Townsville for treatment. Unfortunately, he died on the way."

"Died?" It was Redmond. "Was this guy taken sick?"

Kingsley's answer came reluctantly. "Well, yes and no. He was poisoned. He trod on a stone-fish."

Behind him, Earl Redmond hooted in open scorn.

"Say, Doc—what the heck is this? Another fish story?"

Kingsley turned slowly. "No," he said clearly. "It happens to be true. During the war, Army Operations established a radar base on the island. This young chap was an operator. The personnel were warned about roaming the reefs barefooted. This lad ignored instructions...for the last time."

Captain Robertson cleared his throat. "Fact!" he grunted. "Stone-fish. Devilish things. Put your foot on it. Up come its spines. Pours poison into the wound."

Redmond said unsteadily, "What kinda dope is it?"

Dr. Kingsley shrugged. "Pathology has yet to find out. So far, we only know its effect. A paralysis of the entire nervous system which is proof against even powerful opium injections." His voice slowed. "And which kills within four hours."

And at that moment the telephone on the table shrilled abruptly. Earl Redmond took up the receiver.

"Yeah?"

With the ringing of the telephone, a silence had fallen in that sunny cabin, a hush threaded through with the living sounds of a moving ship. Robert, who was closest, could hear very faintly the thin metallic voice at the other end of the wire. Actual words he could not distinguish, but their effect upon Earl Redmond was alarming. He gave a sudden choked-off gasp and his mouth hung open, foolish, witless.

"No," he whispered, "it can't be...No..."

The colour had drained from his face. Then abruptly his knees folded under him.

The receiver, dangling from its cord, swung slowly backward and forward.

Dr. Kingsley leapt forward, with Captain Robertson half a step behind. As they bent over the unconscious man, some instinct prompted Morte to put the receiver to his ear. But the line was dead. Barely had he replaced the receiver when Mrs. Sheerlove entered. Several bottles were clasped firmly to her breast, and under one arm she hugged a carton of cigarettes.

"I just thought I'd step down to the bar—" The words died suddenly on her lips.

"Earl!" Her voice was shrill with anguish.

She had dropped on her knees, cradling the dark head in her lap, smoothing the chiselled features with trembling pudgy fingers. The tears streamed down her cheeks, furrowing the powder so that the face she turned to them was tragically ugly in its grief.

Harriet Sheerlove rose and stood with fingers pressed across her mouth, so that her next words were muffled. "It's sunstroke," she said huskily. "I knew it would happen."

"Yes, yes." Kingsley straightened. "But I can assure you that the sun had nothing to do with this. Judging by the way your nephew's pulse is racing, he's had a very bad shock." He spoke over his shoulder to Morte. "See if you can find any brandy in that cabinet."

Mrs. Sheerlove cried out impatiently. "Of course there is! Everything he wanted is there. I've never stinted him a single thing." Abruptly she seemed to realise the significance of the doctor's first words, and she stared at him with reddening eyes. "A nasty shock? But that's just plain silly!" She wheeled on the captain. "You said he was talking on the telephone!"

Robertson nodded. "Right! Most odd thing I've seen—" Then he stopped at a gesture from Kingsley. Robert, feeling among the stacked bottles, turned. Redmond had stirred, the head lolling drunkenly. A tongue flickered across his full lips and he swallowed.

"Where...Where is she?" he whispered.

Harriet Sheerlove was by his side in a moment. "I'm right here, honey-lamb."

Abruptly Redmond's white teeth flashed in a snarl; he thrust out an arm and almost pushed the woman out of the way.

"For God's sake leave me alone!" he snapped. "And stop pawing me!"

"Earl!" The woman was on her feet, brushing the tears from her face so fiercely that mascara smudged one cheek. "Earl, darling, you just don't know what you're saying! You're not well..." But the young man was struggling to his feel, ignoring her outstretched hand. He steadied himself against the table and faced the three men.

"Guess I made a prize monkey of myself." He essayed a tight smile. "Reckon I've been hitting the bottle too much."

Mrs. Sheerlove did not speak. Morte was suddenly conscious that his companions felt their presence an intrusion in that cabin. Kingsley broke the silence with a slight cough.

"All right now, Redmond?" And as the other nodded impatiently, he added, "If I were you, I'd rest up this afternoon. And I'd lock the liquor cabinet for a few days."

Captain Robertson grunted something about duties and the other guests took the cue rather thankfully. Morte, who was last to leave, closed the door firmly behind him, but not before they caught the beginning of a tearful tirade front within.

"Earl, darling—how could you? To speak to me like that...and right out in front of all those men..."

When Robert returned to his own cabin, he lost no time in retailing his story. By the time her husband had finished, however, Jane was sitting up and frowning.

"Of all the extraordinary things!" she announced. "Whatever do you make of it?"

"I'm waiting to hear your theory."

"Obviously some stupid practical joke."

"Stupid practical jokes don't cause men to faint," Robert pointed out. "Anyway, who'd be likely to do such a thing?"

"One of the officers, perhaps. Even one of the crew."

Somewhere the ship's bell beat out a single stroke. A water-glass vibrated in its container with the motion of the ship. As Robert did not speak, Jane prompted him. "Don't you agree?"

"No." His tone was sombre. "There's something you don't understand, Jane—something I don't understand myself. I haven't mentioned it to anyone else..." He had taken a cigarette from his case and he turned it over in his fingers. "You see, when Redmond answered that telephone I was closest to him. And I could hear the voice on the other end of the line. Not words—just the pitch of the tone." He raised his eyes.

"I'll swear that it was a woman."

Jane digested this information. "Could it have been Harriet Sheerlove's voice? She was out of the cabin at the time."

"If it comes to that," said Robert testily, "so were the entire ship's personnel." He snapped a lighter under his cigarette. "I tell you, Jane, that woman was almost beside herself with panic. And, in the name of fortune, why should Harriet Sheerlove want to play such a senseless trick?"

"All right," said Jane shortly. "Who else could it have been?"

Morte blew a thin spume of smoke. "Possibly Leila Harland.'

"Oh, no!"

"Jane—have you ever heard of a well-to-do family in Sydney named Harland?"

"No," she replied. "But that doesn't mean a thing." Her face lightened and she jumped from the bed. "Robert—we've both been so stupid! There's one certain method of tracing that telephone call."

"How?"

"Ask the switchboard operator," cried Jane triumphantly.

Morte grunted. "On this ship the inter-cabin phone service is automatic."

"Oh," said Jane, rather dashed.

From down the corridor, the musical chime of the dressing-gong rang clearly. Mrs. Morte padded across to the wardrobe and began to change.

"Jane..."

She turned from the mirror to see that familiar humorous twist to his mouth.

"I've been thinking," he went on. "A woman made that telephone call. Make no mistake about that! So if it wasn't Mrs. Sheerlove or Leila Harland, there's only one other person it could have been. You!"

"I almost wish I had thought of it," she confessed. "Mr. Redmond is so very keen on shocking people that it's more than time someone gave him a dose of his own medicine."

Neither Earl Redmond nor Mrs. Sheerlove made an appearance at lunch. Scarcely had the meal began, however, when Dr. Kingsley appeared. He paused at their table and suggested that the doctor might care to join them. Kingsley seemed pleased at the suggestion. The meal over, Jane returned to her cabin to write letters. When Kingsley left, Robert, feeling drowsy, wandered on deck.

On that lazy, sun-drenched afternoon, everything should have been conducive to slumber. Yet, curiously enough, Morte found himself suddenly clear-minded and alert. It was inevitable that his mind should revert to that perplexing incident of the morning.

On a cargo ship ten miles from land, a ship with a passenger-list composed of a handful of strangers, some unknown person had rung through on a telephone and shocked Earl Redmond into unconsciousness. Robert was equally certain of two things—first, that it was a woman's voice he had heard on the wire, and, second, that unless a sane world had turned topsy-turvy, there was no logical reason why it should have been Mrs. Sheerlove. This aging and foolishly devoted woman seemed the last choice on the ship to play such a senseless charade. Because, although he would never have admitted it to Jane, Morte was becoming increasingly certain that there was between these two a much more sentimental attachment than mere relationship.

So, with Harriet Sheerlove dismissed, who else remained?

Leila Harland?

Again why? Robert moved restlessly. Why should a convalescing invalid play such a completely insane joke on a stranger she had never even met?

Insane?

Robert sat up with a jerk that set his chair rocking. In that moment his questing mind fastened on a chance phrase of Kingsley's, uttered earlier in the day. "All this," the doctor had said when referring to his patient's unfortunate accident, "has left her in a highly nervous condition." And then that remark of Hammond's, muttered on the wet dock twenty-four hours ago. "It's played the very devil with her nerves..."

Could this be the work of a mind sick and unbalanced by neurosis following shock? In execution, the motive was, perhaps, feasible, but it was the result that made such a theory untenable. The chance ramblings of a partially demented female would never have inspired that scene in Redmond's cabin.

He rose, pushed aside his deck-chair, and walked to the rail.

Dinner that evening found Mrs. Sheerlove and Earl Redmond at their table in the saloon. And, while the woman seemed rather subdued her companion had obviously recovered his ebullience. Over coffee, he regaled his fellow passengers with tales of his prowess with the lasso. The Mortes gathered that Redmond's relatives owned wide tracts of land in his native country and that the young man was considered an expert with the rope. The promise of an early demonstration, however, met with such a marked lack of enthusiasm that the young man retired to his cabin in a mood bordering dangerously on the cantankerous.

Shortly after this, the first officer and Dr. Kingsley joined the Mortes at bridge. They played until close on midnight, when Robert, who had been stifling yawns throughout the last rubber, called a halt. They sought their cabin, where he fell asleep almost at once.

Jane was not so fortunate. She lay and stared into the darkness, listening to the throb of the engines.

Her thoughts, shuttle-like, spun to and fro, spanning the past and the future.

How would she find her home when she returned? Was she foolish to have let it to those tenants? Yet, at such short notice, decisions had to be made rapidly. If the war had spared their son, he would be married now and he and Vivienne could have taken the place over. For a moment her thoughts dwelt on Peter, lying alone in a New Guinea jungle grave.

Ten feet away, in his comfortable bed, Peter's father muttered something, turned restlessly, and settled again.

And, quite irrationally, Jane felt a sharp twinge of resentment. Really, it was too bad of Robert! Surely little good could come of this ruthless severing of threads so carefully woven over the past decade? And why did Margaret Vane have to fall sick just at this particular time?

She never knew just what had brought this woman into her mind. But the image of this middle-aged actress, having come unbidden, refused to be banished, and she found herself brooding on a portrait of this woman, hazily sketched by certain details Robert himself had mentioned.

"A delightful person, Jane. Not only has Mrs. Vane considerable talent, but the charm and poise that comes from genuine breeding."

"Mrs. Vane?"

"Oh, yes—she's married. With an eighteen-year-old daughter, I believe. I don't know her name, but I think they have a home somewhere in Vaucluse. And I rather fancy the husband is dead."

Jane had said, "For a professional actress, this woman's background seems rather indefinite."

And Robert had nodded. "She's reserved almost to the point of being reclusive. About her private life, I mean."

It was some months later, Jane recalled, that the spotlight of notoriety had fallen, blindingly if temporarily, upon this woman, and then in a manner pitifully tragic. Her daughter had been found, dead by her own hand, in a cheaply furnished flat in Kings Cross. Yet even this sad occurrence was somehow veiled in partial obscurity—its news value being confined to a small newspaper paragraph. Its only lasting effect was that Margaret Vane made fewer public appearances.

With a jerk that set the bed creaking, Jane awoke. She was trembling and her nightgown was damp with perspiration. It was almost five minutes before she turned her head to the illuminated travelling-clock on the table between their beds. It was close on three.

And then she heard the sobbing.

Jane sat up. She could no more have ignored the disturbing manifestation than she could have stopped breathing. Peering into the darkness, she strove to locate the sound. Then, softly, she rose, took dressing-gown and slippers, and moved out on to the deck.

Here the sobbing was nearer, clearer.

She listened again.

Jane's first assumption had been that this sad wailing came from the cabin of Harriet Sheerlove. Out here on deck she knew she was wrong. It seemed to emanate from the stern of the ship, and it was here, she remembered, that Leila Harland had her secret apartment.

She was almost abreast of the balcony before she noticed Miss Harland. And such was the woman's attitude that Jane was no longer in doubt as to the source of that sound. Kneeling on the floor, arms outstretched across the window seat, head buried face downward in its velvety texture, Leila Harland's attitude was the very epitome of grief and desolation.

Jane's first impulse was to step forward and address the woman gently. Yet she hesitated—first because it seemed almost indecent to intrude at such a time, and secondly...Jane blinked and looked again. What was so unusual about that crouching figure with the outstretched arms? She took a half-step forward; then her breath caught in her throat.

Hands...

Mrs. Morte drew a deep breath. It was not possible, yet to confirm her impression she forced herself to complete the pace to the window. Now she could see quite plainly the white gown stretched across the shaking shoulders, trailing down in billowing sleeves to the small tucks and ruffles about the wrists...

But of hands and fingers, of normal digits and joints and sinews, there was no sign—nothing except the blackness of the window-seat velvet on which those missing hands should have rested!

Jane could never remember very closely how she got back to her cabin.

Vaguely, she seemed to recall that the commonplace surroundings suddenly took on some tincture of her terror. She entered her cabin, groping like a blind person.

Robert was still asleep. His regular breathing and the cheerful ticking of the clock soothed her, so that she had almost stopped trembling when she slipped into the still-warm bed and drew the sheets about her. Two convictions were strong in her mind: now she was assured that, of all people on the ship, the author of that telephone call could never have been Miss Harland, so cruelly mutilated in the motor-car accident that even her personal physician had glossed over the details. Her other resolve was that this must be her own secret.

It was after seven o'clock and Robert's empty bed a tumble of sheets when she woke.

Then his voice sounded from outside.

"Jane...Jane! Are you awake?"

She sat up and pushed aside the curtains of the window. He was turning from the rail, a dressing-gown over his pyjamas.

"Come and look at this," he invited, and when she joined him it was to find that they were among the islands.

Jane nodded, drinking in the beauty of the scene, letting it flood into her mind, washing away the murky outlines of another, darker image which lay coiled there all night. Beyond the first island lay another, and beyond that a third, far off, dim-seen, hazy and unreal as a fantasy.

Kingsley had learnt it was possible they would sight Paradise Island in the late afternoon. Redmond, stretched out on a deck mattress, reached out a tanned arm for his cigarette-case. He spoke as he lit up.

"Anyone care to brief me on this new landing party?"

"They're very important people," Kingsley remarked.

Redmond stared at the sky. "So what? Everyone's important these days. That's democracy."

Kingsley merely pressed his lips together and turned away. When he spoke again, it was to address Morte.

"Did you know that we're staying for a few days on Paradise?"

Robert looked up. "I don't mind the break. But surely it's unusual? Isn't there a certain time schedule?"

"Not for freighters. And particularly for a freighter carrying its owners as passengers."

"Does this mean we stay on the ship?"

"It's a matter of choice," Kingsley assured her. "If you feel like a break, you'll find Paradise very comfortable. It's one of the few islands with individual bungalows—all very modern and up-to-date. The island lessee—chap named Ferrier—brought back the idea from Florida. That's probably why Arthur Burton and his daughter chose Paradise for their holiday."

"A daughter?" Redmond sat up. "What's her age?"

Kingsley said clearly, "Her age is twenty-two. Her name is Patricia. She is heir to half a million pounds."

Redmond winked. "Beat the drums," he announced. "Brother, it's a celebration—real sex-appeal coming on board at last!"

Harriet Sheerlove said gently, "Now, Earl, don't you be so tiresome." Then, in a valiant effort to change the subject, she added, "I'm most eager to see this Mr. Skinner." She raised her wide, grey eyes. "But he's so very, very old, isn't he?"

Kingsley nodded. "Old..."—there was so long a pause they believed he had finished until..."Old, and rather horrible."

Heads turned in his direction. "Horrible?" said Jane. "In what way?"

The doctor flushed almost as scarlet as Harriet Sheerlove. He said quickly, "That was a foolish remark. Please forget it."

But Redmond's dislike of the doctor was too keen to allow such an opportunity to pass. "Oh, no," he drawled. "You can't shy off like that, Doc. What's so horrible about this old character?"

The other said almost harshly, "I asked you to forget the remark..."

The latent animosity between these two, like a banked-down fire, threatened in that moment to flicker and flame into open conflict. Morte saw the doctor's hands tighten about the rail. Next moment they relaxed and he shrugged. His tone was quiet.

"It's no guilty secret, Mr. Redmond. I knew Eli Skinner some years ago. It was in a purely professional capacity. He suffers from a chronic cardiac condition."

Robert said, "What is he like?"

"Any other old man. Thin, a little shrunken. Anyhow, you'll be seeing him for yourselves very soon now."

He turned and stared fixedly across the water. A smudge on the horizon had resolved itself into a ship. The feather of smoke from the funnel rose straight and unwavering to join the thickening haze through which the sun gleamed redly. The atmosphere was becoming as oppressive as the silence, when Mrs. Sheerlove spoke brightly.

"Just fancy, Doctor! I didn't know that you attended millionaires!"

"Thank you for the implied compliment, Mrs. Sheerlove. But Skinner wasn't a millionaire then." His lips twisted slightly. "He was governor of one of our most dangerous jails!"

Earl Redmond gave a sudden throaty gasp and almost leapt to his feet.

"What pokey did the old guy run?"

Kingsley said imperturbably, "A prison named Greycliffe." He spaced the next words carefully. "No person ever escaped while he was in charge."

A polite cough took his attention. Kingsley turned. Mr. Rodda, first officer of the Medusa, stood at his elbow. "Excuse me, sir," he said, "But Dr. Sweetapple would like to see you in his surgery when you're disengaged."

This was the ship's doctor, a medico of such extremely youthful appearance that Jane, on seeing him, had immediately offered up silent prayers for a trouble-free voyage.

Kingsley nodded. "I'll come along right away." With a murmured apology, he moved off.

"That bird's going to run me ragged," Redwood muttered to no one in particular. But, surprisingly, Mrs. Sheerlove snapped at him.

"Oh, for pity's sake. Earl, behave yourself!" She stood up, balancing herself carefully. "I declare that I've developed a most agonising headache. If you want me, I'll be lying down in my cabin."

Turning, she gathered up her cushion, her unopened book and sun-glasses, her jar of sunburn cream, took up a cigarette-case and a silver lighter with her initials engraved, and, thus burdened, looked down at the young man.

"You'd better come inside, too, Earl."

Redmond did not move. "Go take an aspirin, Hattie," he grunted.

The woman stiffened. She wheeled away from him, an absurd defiant turn ignominiously defeated when the heel of those most inappropriate sandals slithered suddenly on the scrubbed deck.

Harriet Sheerlove tottered perilously, grabbed at thin air, dropped the cushion, tried to catch it, and lost her grip on the glass jar.

It crashed to the boards and a white froth spread wide across the planking.

"Oh, bother!" she exclaimed. Robert and Jane were on their feet. "Give me the cushion," Mrs. Morte said gently, and as the other made a weak protest she added, "I'm going in myself now."

She assisted Mrs. Sheerlove down the companionway and kept a firm hand on her arm until they reached her cabin. There Jane passed over the belongings. "You're sure you have everything?" and paused while Harriet made an inventory. Suddenly she gave a little squeak of dismay.

"Oh, dear! I've taken your cigarette-case."

She held it out, a slim silver object. But Jane shook her head. "It isn't mine. And Robert's case is tortoiseshell."

"Mine is of gold." Even in that moment, Mrs. Sheerlove could not keep the note of pride from her voice. "It was one of the first presents Earl gave me. He bought two of them," she added. "One a little larger, which he kept for himself. He was using it out there this morning."

Jane nodded. "This must belong to Dr. Kingsley. I'll return it to the doctor." She pushed open the cabin door. "Now, is there anything that you'd like? Can I call the stewardess?"

"No. She'd only fuss me." She entered and Jane followed, replacing the cushion on the chair, laying the book and sun-glasses on the table near the telephone. Mrs. Sheerlove kicked off her sandals and lay back on the bed. She closed her eyes and her reddening face contracted with a spasm of pain. "Don't blame me too much about Earl," she said. "It isn't what you think at all."

"What I think?"

"He's not my lover." Oh, God! thought Jane. Why do I get myself in these situations? The voice droned on. "You've seen him. Do you think he'd take the slightest interest in me...that way? Perhaps, in the beginning, I thought that he would..." She sighed deeply.

Jane looked down. Harriet Sheerlove lay with closed eyes.

But there was one other task to perform before Jane Morte could retire to her own suite.

Intent on returning the cigarette-case, she made her way to Dr. Sweetapple's cabin, where she hoped to find Kingsley. The half-open door revealed an empty apartment. She walked out on deck on her way to the smoke-lounge. Ahead she located her quarry.

Dr. Kingsley was moving in the direction of Miss Harland's private suite. She quickened her steps, treading the path of her previous expedition, and reached the edge of the cabin where some hours before she had taken shelter. Directly ahead was the glassed-in balcony. Now the sliding panes were tightly closed.

She saw that she was too late. Dr. Kingsley was already inside the room, talking with Miss Harland. The silken scarf was no longer swathed about her face; now it was wrapped turban-like about her head. The woman stood with her back toward the window, facing her companion, and, although the shuttered windows cut off every sound of their voices, the doctor's tight stance and serious expression hinted at a colloquy both earnest and important.

Now Kingsley was shaking his head, an obvious negation of some point in the discussion. Then Leila Harland moved—and Jane's head jerked back as surprise and a great secret relief flooded through her.

For in that sudden action the enigmatic Miss Harland had thrust out arms and laid urgent, demanding hands on the doctor's shoulders. Hands! Hands and wrists covered in long white gloves from elbow to fingertip, but hands, undeniably and with strong fingers that bunched the material of Kingsley's jacket in their tight, possessive grip. Jane watched as he shook his head for a second time, saw the woman's shoulders droop despondently as her hands fell away. The doctor moved out of her field of vision and Miss Harland followed.

But Mrs. Morte was scarcely conscious they had gone. The explanation was suddenly so simple and so natural that she marvelled at her obtuseness. The hands and fingers that the grey invalid had donned overnight were artificial—mechanical products of war-time ingenuity!

Thus relief and sympathy warred in Jane Morse's heart, and she was inside her cabin and crossing to her bed before she realised that she was still holding the cigarette-case.

When his wife had left the deck with Mrs. Sheerlove, Robert's first impulse had been to follow.

"Just stay put for a minute," Redmond said. "I've been waiting for a chance to get you alone, Morte. There's something we ought to talk about."

"Indeed?" said Robert, with sinking heart.

"Yeah...You're a kinda detective guy, aren't you? Even if it is only book-work. How would you like to untangle an honest-to-God, real mystery?"

"I'm listening," Morte said quietly.

"It's a damned odd business. That little show-down in my cabin yesterday. It just about scared hell outa me..."

"So you did recognise that voice on the telephone?"

Redmond nodded moodily. "I'm not kidding when I tell you it was the last person in the world I expected." He paused and chewed at his lip. "You see, it was my wife."

Robert said sharply, "Then you're married?"

"I was."

"Divorced, then?"

The other shook his head. "No, mister. It isn't as easy as that. There's so much here that doesn't make sense. It's crazy, I tell you. Such a thing just can't happen..."

"Then you must have been mistaken."

Redmond said darkly, "Not me, sir! You can't mistake a voice you've lived with for twelve months! Not Monica's voice with that cuts little lisp. And she called me Sailor." He tapped a tattoo-mark on his thick forearm. "No one else in the wide world knew that name. No one but Monica."

"I don't suppose it's possible your wife could have somehow followed you...stowed away in this ship...?"

And Earl Redmond said harshly, "I'll tell you why not!" Something choked in his throat so that the next words were husky and dry. "There's no such person as Monica Redmond now. Because she died...out in Canada...just six months ago!"

A flying-fish skittered across the water, turned from gun-metal grey to shining silver, and disappeared with a splash of foam. The sweat gathered on Redmond's chest.

"Well?" he panted.

Robert said in slow disgust, "Of all the damn-fool nonsensical jokes..." He jumped to his feet and began to walk away; but with a quick, cat-like spring Redmond barred his path.

"Listen, Morte! So help me, I'm telling you the truth! The plain, honest-to-God facts! Okay, it's crazy! That's why I haven't had the guts to mention it before. But I've gotta tell someone...before, maybe, I go nuts myself over this!"

Morte's cold eyes raked his companion, taking in the heaving chest, the twitching mouth, the sweat that dewed the forehead and the face suddenly sallow, lined, and old.

"Come over here," said Robert.

On the open deck the heat was unbearable. But near the rail a suggestion of a breeze stirred. The ship moved through a sea of grey oil, and, watching that thickening haze, Robert kept his eyes averted from Redmond's face as the man began to speak.

"We were married in Montreal—Monica and I. I'd known her quite a while—boy-and-girl sweethearts sorta stuff. You know the Gaspe Peninsula in the Gulf of St. Lawrence?" He paused as the other shook his head. "Well, there's a cute kinda fishing village there—place called Perce.

"And about half a mile out to sea there's a landmark. It's mighty well known in that locality. Huge steep rock jutting up, big as all get-out—they called it Rocher Perce. Well, we're having ourselves a little picnic one day down on the beach near here—and nothing will satisfy that girl but we get our pictures taken up on that old rock. Naturally, I do my best to talk her out of such a crazy idea...I talked to that girl till I was darn well tongue-tied, but it didn't make a scrap of difference. That was the way Monica wanted it and nothing would budge her. Told me I was too yellow to try the stunt."

Morte stole a side-glance at his companion. There's something wrong, he thought, something that doesn't ring true. But before he could analyse the fleeting impression, his companion was speaking again.

"I guess that morning is one of the things I'll always remember. We walked back to the village and I borrowed a coil of rope and a grappling-iron. I wasn't worried—not for myself. In the Rockies I'd climbed around with less equipment than this. Anyhow, we took a boat and rowed to the foot of the rock. I went up the easiest side—it took me quite some time and it must have been half an hour before I topped the rock and fixed the rope tight. I snaked it over the side and called to Monica.

"When she began to climb, I realised I'd been dead wrong to worry. She had guts and skill—she came up that rope, hand over hand, like the cute monkey she was. That's why I'll never fathom how it happened. She was about half-way up! I could see her face all sorta shining and happy. Then suddenly she screamed out something—screamed and fell. I couldn't believe it. I just stood there dumb watching her as she turned over and over, to land on those rocks fifty feet below."

The voice low and husky, choked and was silent. Morse said quietly, "I'm very sorry, Redmond..."

The other made a quick gesture. "Okay—okay—it's all in the past now." He stopped abruptly, peering up into Morte's face. "Or is it? That's what I want to know, mister! Is it?"

"That depends on whether your wife's body was ever recovered."

"Recovered?" The Canadian blinked at him. He said harshly, "What kinda guy d'you think I am? Think I'd just let her lie there?" The tone was impatient. "I told you, mister. On to the rocks below. I shinned down and picked her up. She was dead. I took her back to the mainland in the boat..." His mouth twitched suddenly. "That was swell! Bringing her back like that when we'd been married about a week before..."

Robert said gently, "Where was your wife buried?"

"Montreal. St. Stephens. Her parents came down after the accident."

The silence lengthened between them. Morte said at last: "Have you any enemies? People who might possibly have put through that telephone call, simulating your wife's voice, perhaps to upset you?"

"I've thought of that." The reply was moody. "First, it'd have to be someone on board this ship. I'd never seen or heard of anyone outside of Hattie." Redmond added: "And you've gotta remember that all this happened in Canada—thousands of miles away!"

He went on, with a soft savagery that made Robert glance at him quickly. "That god-damned telephone! It rang again; you know..."

Morte's glance became a stare. "You mean...?"

"I'll wager it was the same voice. It was early this morning, just after three o'clock. I just didn't have the guts to answer it. Just lay there sweating while it rang and rang! I couldn't take it any longer; so you know what I did?" The voice rose. "Cut the bloody cord with a pen-knife! That fixed it!"

Robert considered. "Wasn't that rather foolish? It might have been a passenger ringing you."

"At that hour of the morning? Who'd be likely to do that?"

"Your friend Mrs. Sheerlove."

"Hattie wouldn't ring. She'd come tapping at my door like always before."

Morte said, "So you want my advice?"

"Mighty badly!"

"Very well. Go straight to Captain Robertson and put all the facts before him."

The other laughed—a short, ugly sound. "Are you just playing dumb? Guess we don't need a crystal ball to know what would happen then? Either I'd finish up in the brig as a racing nut or else they'd trot out that guy Kingsley to psycho-analyse me. No, mister—if that's the best advice you have, I guess it's all been just a waste of breath."

"I'm sorry," repeated Robert, but the other waved a hand.

"Okay! You're just not as smart as I figured, that's all."

A spot of rain, large as a two-shilling piece, plopped audibly on the deck. A breeze sprang up suddenly, a chill breeze that caused Redmond to shiver. He began to massage his naked chest. "Between you and me, mister! Private information—top secret—get what I mean?" He turned and began to lope across the deck toward the companionway.

Robert made his way below.

During lunch the sun broke through again, glinting experimentally on the wet deck, flashing on steel and paint with a sheen that dazzled the eyes.

But the storm left a humidity that even the electric fans failed to alleviate. Robert and Jane went to their cabin, where she blamed her husband's restlessness on the atmosphere. He paced the floor, finally to fling himself down in an easy chair and reach for cigarettes.

"Robert..." Jane's voice, very quiet, cut into his thoughts. "Why not talk it over with me?"

"There's nothing much to talk about."

She came across and sat on the arm of the chair, ruffling his hair again. Presently she said, "Very well, I'll tell you. You're worried about Mr. Redmond."

Robert sat up. "Jane! Don't tell me you were eavesdropping?"

"Certainly not."

"Then how could you possibly know what he told me—"

Her eyes were bright with comprehension. "So this man told you something!"

Robert was silent.

"So it was something queer?" Jane sat down again on the arm. "So strange that you'll imagine I'll rush from one end of the ship to the other, shouting the story to everyone I meet?"

"Don't be absurd!" said Robert.

At that she sighed a little. "All right, darling. Be a stubborn mule."

Robert crushed out his cigarette and reached for another.

"All right," he said. "Let's see what you make of all this!" And, crossing to the window, hands thrust into pockets, he retailed the story heard from Redmond's lips. When he had concluded, she was silent for so long that he prompted her.

"Well?"

She said carefully, "The story might have been manufactured, but Redmond's fear was very real—too real to have been simulated?"

He snapped his fingers. "That's it exactly."

"So real, so very sincere, that the voice on the other end of that telephone was someone Redmond believed dead and buried." Jane saw him nod quickly. "But, darling, don't you see? That takes us right back to where we started. Even further back."

Jane Morte moved to the couch. "Just like twenty questions," she murmured. "Except that it should be so much easier. Because there are only three."

"Three questions?"

"No, no. Three women." She looked up. "Or, rather, four if you count the stewardess."

"But why should the stewardess want to scare Redmond?"

Jane shrugged. "Why should I? Or Mrs. Sheerlove? Or Leila Harland...?" But Robert saw her eyes narrow suddenly. Then she spoke very softly, almost to herself. "I suppose the woman really is dead?"

"Redmond saw her buried."

"Yet queer things can happen." Jane spoke slowly, her mind obviously two steps ahead of her words. "Fake burials—substitution of bodies. I've read about such things."

"No, Jane, it isn't ridiculous. But if we presume a fake burial in Canada, then we must accept the rest of the story. The expedition to the rock, the attempt at climbing, and the girl's disaster..."

"I agree."

"We must also accept the fact that she sustained certain injuries..."

Jane nodded, "Quite so."

He waggled the match-end in her direction. "Then you believe that this girl, recovering completely from these injuries, has somehow managed to stow herself away on this ship...?" He paused as Jane shook her head.

"I don't think she has recovered from her injuries. Nor do I believe that she stowed away." She contemplated her long fingers for a moment. "I think she came on board quite openly, just as you and I came."

Mrs. Morte was silent, so silent that Robert was about to regret his question. But she spoke a moment too soon. "Suppose when that poor girl fell, she took the force of the impact on her hands and face? Supposing she wasn't killed but shockingly mutilated? And supposing a skilful surgeon could restore her face, giving her an entirely different appearance, making her totally unrecognizable...?"

The match-stick snapped in Morte's fingers. "Leila Harland! But, Jane, the face perhaps...yes, it's possible! But there's nothing wrong with her hands..."

And Jane Morte said quietly, "Those hands are false, Robert. Artificial digits that can be removed overnight."

There and then she outlined her adventure on the moonlit deck and the surprising sequel of the morning. Robert shook his head. His voice was very gentle.

"A tragic thing, Jane—a bitterly tragic thing. And you say she seems a young woman?"

"Just a girl. That was what was so horrifying, I think. I'd pictured Miss Harland as a middle-aged spinster—yet I can't think why. But she isn't."

"You didn't see her face?"

"Only her figure," said Jane. "But she's young, Robert—I'm certain of that."

A tap on their door cut the sentence short. Jane gave her husband a quick, questioning glance, then crossed. As the door swung wide, Mrs. Sheerlove stood revealed.

"Is Earl with you?"

In answer, Jane gestured her inside and swung an arm around the room. Harriet Sheerlove blinked. "He's hiding, that's what it is. Just because I snapped at him this morning."

"I suppose you've tried the most obvious place—in his suite?" said Robert.

"Oh, of course!" She lowered her voice, glancing conspiratorially at the open door. "When he didn't come down to lunch, I knew what was the matter. I went straight to my cabin and rang through to him. But the line seemed dead." She blinked again, almost defiantly. "I thought, 'He's taken the receiver off the hook, I know'; so I went straight down to his cabin. It was empty. And, would you believe it, the receiver was on the telephone all the time! That wilful, foolish boy had cut the cord!"

Robert said, rather lamely, "The cabin steward will have something to say about that, surely?"

The plump chin set obstinately. "I don't care if he never speaks to me again...never! And I won't address a single word to him unless he apologises! I'm not even sure whether I'll pay for that telephone—"

From outside a deep voice hailed. "Paradise Island to starboard!"

There came the sound of quick footsteps in the corridor, and Robert said briskly, "Come up on deck, Mrs. Sheerlove. You'll probably find Redmond waiting for you." With a pettish toss of her head, the woman walked from the cabin, tossing a final remark over her shoulder.

"If he is out there, you tell him just what I said!"

It was a few minutes later that they joined Second-Officer Willis on deck and followed the direction of his pointing finger. In the amber glove of the afternoon, it was a smudge of purple shadow. Then Willis passed his binoculars to Robert, and through the lenses the island took on colour and shape.

The dinner-gong took them to the saloon; but the Mortes, who had a table near the window, could watch the island swim closer. Now they could see the white strip of sand marking the beach and dotted with small figures.

A few minutes later, Captain Robertson entered with Chief-Officer Rodda. Morte caught his eye and the skipper halted at the table.

"When can we go ashore, sir?"

Robertson grunted. "Whenever you please. Prefer you to stay, however. Burton party coming aboard. Matter of half an hour. Might like to meet them."

Robert and Jane moved out on deck, where three sailors were releasing the coil of wooden laddering from the rails.

Now the fringe of the island was twinkling with lights and muffled by distance, they could hear the regular thudding of an electric generator. Beyond the tracery of the tamarisks, bungalows shone as a string of bright windows. Faintly across the water came the sound of voices and a girl's light laugh.

Half-seen against the glow of the bungalow windows, Robert noticed a small knot of people advancing across the sand. Obviously the "Burton party" were on their way.

Jane plucked at her husband's sleeve. "We mustn't be caught peering," she said.

It was some ten minutes later that Second-Officer Willis tapped on their door.

When they reached the skipper's cabin, Mrs. Sheerlove, Dr. Kingsley, and Earl Redmond were already there. Robertson was conversing rather awkwardly with a big, florid-faced man whom they recognised as Arthur Burton. Both men glanced up as they entered.

"Mr. and Mrs. Morte," murmured the captain, in introduction.

Burton nodded and took Robert's outstretched hand in strong, soft fingers. The man behind the vast enterprise of Burton's Incorporated Industries had a massive head and the shoulders of a weight-lifter. His hair, greying, waved back from the broad temples in a thick mop, and beneath it the features, on the verge of being blurred by fleshiness, were still regular and well formed enough to mark him as both handsome and distinguished. The authority in that jutting chin and the bland assurance of wealth and success stamped him as individual in that tiny cabin.

"May I introduce my daughter?"

Patricia Burton was not beautiful—the red lips were a shade too thin, the chin dominant to the point of arrogance. But she had her father's colouring, eyes of deepest violet, and black hair that shone with secret and exciting lights. Her smile was delightful, full and frank and friendly.

"Stephen," she said.

He acknowledged their greeting rather unwillingly, Robert thought. Stephen Hawke was as blond as a newly minted coin, with butter-yellow hair, eyebrows so fair as to be almost indistinguishable against his pleasant tanned face and the suggestion of a moustache on his long upper lip. Morte liked him on sight. There was something about his compact, stocky body, some expression on those serious, regular features, that suggested a stubborn dependability.

"This is Father's right-hand man," Patricia was saying. The young secretary gripped Robert's hand and muttered something to Jane. He seemed unnaturally shy and dropped into the background the moment introductions were over. A short and slightly awkward pause. The first officer was handing around drinks. The silence was broken by Earl Redmond.

"Miss Burton..."

She looked at him, eyes cool and appraising.

"Where's the rest of your party?"

A voice spoke from the doorway. "Here I am."

Every head turned. Elihu Skinner stood blocking the entrance, leaning on an ebony stick gripped in clawed and crippled hands.

He was old. That was their first impression. Old and yellow and lined. And thin to the point of obscenity, shrunken in his dark, rumpled clothes like a chrysalid prematurely dead in its cocoon. The face was a mask of protuberances—brown, cheekbones, chin—and over these, tightly drawn, the parchment of his skin glistened faintly in the light. Under those jutting brows, sunken deep, were small, shrewd, acquisitive eyes, the coldest, bleakest, deadest eyes Robert Morte had ever seen.

He stood there, purpling fingers clawed, head thrust forward like some aged vulture. And his scrawny vulture's throat worked as he spoke.

"I don't like my cabin, Arthur."

Burton said civilly, "What's wrong with it?"

"I asked for a deck cabin. I find that I'm amidships." Those small toad-like eyes had never left his partner's face.

"But you have a deck cabin, Arthur—so I've changed places with you. I'm having Vincente make the change now."

Burton said suavely, "Do just as you like, Eli."

The heavy stick scuffled, seeking hold on the polished floor. Without the slightest sign that the other people existed, the old man turned and limped away.

Very deliberately Arthur Burton took a pigskin case from his pocket and extracted another cigar. He pricked the end with careful fingers, keeping his eyes lowered as he spoke. "That was my partner." The tone was detached, a board-meeting voice underlining dull but necessary details. "He is far from well and often in considerable pain. Since we are all to be passengers on a long voyage, it might be well to keep this in mind."

Captain Robertson stepped forward and struck a match. Cigar in mouth, the big man leaned forward.

"Stephen and I are going ashore, Daddy. Are you coming with us?"

"Not yet, my dear." Burton's eyes rested for a moment on the secretary. "And I'm afraid you can't have Stephen for a while. I need him here."

"But it's quite late—"

Hawke turned. "Run along. Pat. I'll join you just as soon as I can." He faced his employer. "Mr. Skinner wanted to see that Blandings correspondence, sir. I've brought it along in my briefcase. It's in my cabin."

Miss Burton's lips set mutinously. "Stephen," she said, "you promised—" She stopped as though realising they were not alone.

Earl Redmond spoke into the silence. "Reckon I'll go ashore myself tonight. I'll just slip up to my cabin and pack a few duds." He brushed past Harriet Sheerlove as though she did not exist and threw open the door, almost colliding with a man who stood waiting, on the threshold.

"Martino!" exclaimed Hawke.

The newcomer jerked his head. He was a swarthy, powerfully built man, with a wide mouth that was too ready to break into a mechanical smile. Servility cloaked him, plain in the stoop of his shoulders, the quick, indecisive movements of his hands, the shuffling feet. Stephen Hawke's voice was sharper this time.

"What is it, Martino?"

"It is Mr. Skinner—he sends me to talk to Mr. Burton." The averted head showed only a glimpse of white eyes and whiter teeth. "He waits in his cabin. And he says to tell you it is business."

Arthur Burton ground his cigar carefully into an ash-tray. "We'd better go, Stephen. The sooner we get this over, the quicker we can get ashore." His glance took in the room. "My daughter's using the launch, but there's room for several others."

Robert looked at Jane, who shook her head. "I think we'll wait until morning." But Mrs. Sheerlove, her eyes on the stocky Mr. Hawke, took an eager step forward. "If there's a tiny corner for me," she said archly, "I'd be ever so grateful." She moved to the door. "I won't be long. I've been packed all day!"

Patricia Burton followed her out, her father and his secretary close on her heels. The door closed behind them.

In their cabin a few minutes later, Jane began to pack a suitcase. Robert himself lounged near the window, staring out across to the island. The tropic night had enveloped it, thick, warm, and soft.

He looked up as Jane, who had been roaming the cabin and doing a last-minute inventory, halted with an exclamation. "Oh, dear! This cigarette-case!"

She was holding it in her hand. "It's Dr. Kingsley's," she added, and went on to explain the incident of the morning. "The poor man is probably searching everywhere for it." She passed the case across. "Take it to his cabin, Robert."

"You'd better come with me, Jane. After all, you found it."

The door was standing ajar as they approached. Robert gave a tentative tap which set the door swinging wider. It revealed an empty apartment.

"We'll go in and wait for him."

It was a cabin much larger than their own. Under the window a small aquarium had been built, laced with sea-grasses.

On a small table beside the bed, books leaned against the telephone, but these were half-hidden by a large framed photograph. It showed a handsome woman of middle age sitting in a garden chair. Behind her, lawns and flowering beds stretched to the walls of an old half-timbered cottage with low doorways and diamond-paned windows.

"That's an English cottage, surely?" Jane said.

Robert crossed to her side. "Yes. I wonder who the woman could be?"

"Wife...a sister...a friend, perhaps." She leant closer, studying the face. The broad forehead, the steady wide-set eyes, the repose of the mouth. "Robert, she reminds me of someone we know."

He shook his head. "A complete stranger to me, Jane."

"Yes, but..." She frowned. "It must be some chance resemblance somewhere. Perhaps if we knew her name..."

"Her name was Linda."

They turned. Dr. Kingsley stood in the doorway. As though sensing their embarrassment, he went on, "Please don't feel you are intruding." He came in and closed the door. "I only wish you could have known my wife when she was alive. Linda was a charming and lovely person..." He gestured to a chair. "Do sit down, Mrs. Morte."

Jane obeyed. "Actually we came to return some of your property," she said, and glanced at Robert, who produced the cigarette-case and handed it across. "Mrs. Sheerlove found it on deck this morning."

Kingsley turned the case over in his fingers. "It's a lovely thing," he said, "but honesty compels me to admit it isn't mine." He paused and snapped open the case, glancing inside the lid. He held it up. "You see?"

Robert leaned forward, peering at the inscription engraved inside the lid. Seven words:

"To Kathie with love and affection. Ronald."

He straightened. "We never thought to look inside. It must belong to one of the crew."

Kingsley shut the case and handed it to Jane. "You say Mrs. Sheerlove found it?"

"This morning on the sports deck. Just after we sighted the islands..." Jane pondered for a moment. "It seems rather a valuable thing to belong to a seaman."

Morte took the case from his wife. "I'll hand it over to the purser in the morning."

Kingsley seemed anxious to detain them. He sat down on the wide settee. "Well, what do you think of the Burton party?"

Jane Morte said cautiously, "The girl seems very nice. And the young man very shy." She hesitated before her next words. "I don't quite know about Mr. Burton."

"And Mr. Skinner?"

"Horrible." Jane nodded. "Like a bird of prey."

Robert looked at Kingsley. "I notice he didn't recognise you, Doctor."

"Why should he?"

Robert said mildly, "You said you knew him."

"That must be close on ten years ago now. During that time the old chap has probably had a dozen doctors. It's too much to expect that he'd remember one obscure G.P. Ten years..." he said softly. His eyes moved to the photograph. "That was when I met Linda. I had a practice in a Melbourne suburb. One day I felt I could stand it no longer. On an impulse, I wrote for an appointment of ship's doctor—and a week later, somewhat to my surprise, I was accepted. The ship travelled from Melbourne via Cape Town and Las Palmas..." He paused momentarily and his eyes softened. "On that ship was a passenger returning to England. We formed a strong friendship and I learnt that her home was near Sevenoaks, in a tiny village called High Weald. I was invited to call on her. That was in early April...

"You see the garden in that picture? It was there I asked her to be my wife. We were married three weeks later. Then came the war. Linda and I came back to Australia, and, like so many other men in my profession, I found myself in the Army. I became Major Kingsley...

"But I knew that Linda's heart was back in England. Not that she was unhappy in Australia—she was content to be wherever I was. You see, we were still very much in love with each other—that was why her death was such a sad and bitter blow to me."

Jane said gently, "Was it a war accident?"

"No." The doctor's voice was very steady. "She contracted an illness..." They had the impression he was about to add something more; but he was silent, contemplating the burning tip of his cigarette. Then he spoke again. "I must catch Mr. Rodda," and he glanced at his wrist-watch. "There are certain arrangements I'd like to make regarding my patient."

"Then Miss Harland will be joining us on the island?" asked Robert.

"I'm afraid that's quite out of the question. The chief officer has a portable radio. If I could borrow it for my patient, she could listen to the concert broadcasts."

"She's fond of music?"

"As a young girl, Miss Harland studied in Paris. Before the accident she gave a series of quite successful concerts in London."

Jane said, "I didn't realise that she was a singer."

"Oh, no." The doctor crushed out his cigarette. "She was quite an accomplished artist on the piano."

"Piano?" Jane's voice was high. "Oh, but how terrible, Doctor!"

"Terrible?" Kingsley's expression was puzzled. "It isn't as serious as that. Naturally, she'll resume her studies when she's recovered. The injuries were confined to her face. The hands, mercifully, were completely undamaged."

Robert closed the door of their cabin and stood with his back against it. "So there we are, Jane. Right back where we started!"

"Assuming, of course, that Dr. Kingsley was telling the truth!"

"Why should he lie?"

"Because," said Jane firmly, "this so-called patient is Redmond's wife."

Robert shook his head. "You haven't an atom of proof..."

"There was the telephone call."

But her husband was following out his own line of thought. He spoke with decision. "No, Jane. I'm certain Kingsley wasn't lying."

Jane paused and looked up. "But, Robert...what other explanation can there be?"

He crossed and patted her shoulder. "It was night when you saw Miss Harland. You were over-tired, nervy."

Jane was silent, her mind reviewing each small detail of that clearly etched passage along the deck. Could he be right? Had she been deluded by some mirage induced by half-light and raw nerves? She rose and pulled the suitcase toward her.

"I'm going to finish this packing," she said shortly.

Robert grinned and moved out on to the deck. He felt unaccountably restless—restless and suddenly depressed.

The desire for company, for human companionship which could banish this dark discontent, was strong upon him as he mooched, hands thrust into pockets, along the deck. Unconsciously he found himself moving in the direction of Kingsley's cabin, with its lighted window shedding a bar of bright amber across the water. And where the window-light stained the deck he halted and peered through.

He had expected to find the cabin empty, but beyond the window a shadow moved to and fro. Then the doctor came into view, crossing to an overnight-bag opened on the bed, obviously engaged in a similar task to Jane's. And he had almost finished, for even as Morte watched, Kingsley stood irresolute, giving a last final look around the cabin. His roving glance rested on the framed photograph on the table by the bed—the smiling woman in the English country garden.

Ralph Kingsley moved forward and took up the picture with gentle hands. Carefully, almost reverently, he removed the print from its frame and pressed it to his lips. Then, holding the print between thumb and finger, he produced his cigarette-case, ignited the lighter, and held the flame to one corner of the photograph.

Robert Morte stood on the beach of Paradise Island.

Two hours had passed since the Mortes had left the Medusa. Breakfast over, they had climbed down into the waiting launch. On arrival, Mr. Willis, who had accompanied them across, had shown them to their bungalow. This was a twin-roomed unit, sitting-room, small bedroom and shower annexe. It was all as spotless as a Dutch interior and Jane had pronounced herself as delighted. From the sitting-room she could see a number of such dwellings, spaced some fifty yards apart and shadowed by the giant mango trees which fringed the island.

While his wife unpacked, Robert took his first stroll on a coral island. Within the reef that would be bared at low tide, he saw Miss Burton and Stephen Hawke. Both were in swimming costume, brown as berries and stretched out on a painted raft which undulated with the gentle swell.

Suddenly Robert felt a chill. He turned slowly.

Not a dozen feet away, Elihu Skinner, dressed from head to foot in thick black serge, stood watching him.

"Good morning," he said civilly.

Eli Skinner did not move. "Come here."

Morte hesitated, not so much questioning the command as surprised at the tone. Ice and steel were in that cracked voice. He approached the old creature. Skinner spoke again.

"Take off those glasses!"

For a long moment, Robert stared unblinkingly at that mottled, shrunken mask.

"I think you've forgotten two things, Mr. Skinner. My position and your courtesy!"

Abruptly the lean throat worked as he gave a rusty chuckle.

"No offence meant, my friend. And I never had any manners. But I like to see a man's eyes when I'm talking to him." He waved a veined hand. "Keep your glasses on—I've got my answer! You've got guts, Morte. Guts...and honesty!"

Robert did not speak, for the simple reason he could think of nothing to say. Eli Skinner nodded.

"I summed you up last night, my friend, back there in Robertson's cabin. Judgment of men—I've risen by that quality. And I pride myself I'm never wrong."

Robert said quietly, "If I'm listening to you, Mr. Skinner, it's because I'm trying to fathom what the deuce you're up to."

Those obsidian eyes had never left his face. "I want you to come to my bungalow in an hour's time."

"Ridiculous!" In the desire to take a stand against this peremptory old despot, Robert made the first excuse that came into his mind. "My wife and I plan to explore the reef this morning."

"The reef isn't uncovered until late this afternoon."

Those two men, so dissimilar in every way, faced each other across the blazing sand. The thought flashed through the younger man's mind—What is it that runs through those clotted and twisted veins? Not blood but ice-water, surely? Those twisted lips curled. The stick dug deeper into the sand as Eli Skinner put full weight on it and turned away.

"In my bungalow. In one hour's time. I'll expect you."

"Of course," said Patricia Burton thoughtfully, "there's always murder."