a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Wide Horizons: Wanderings in Central Australia Author: Robert Henderson Croll * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1403041h.html Language: English Date first posted: November 2014 Most recent update: November 2014 This eBook was produced by: Colin Choat Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

TO

MY WIFE

WHOSE PATIENCE

MADE THESE WANDERINGS POSSIBLE

Endpaper — Designed by J. A. Gardner

My thanks are tendered to the proprietors of the Argus and the Australasian, the Herald, Stead's Review and Walkabout, all of Melbourne, in whose journals much of this matter first appeared. I am grateful, too, to that excellent institution, the Australian National Travel Association, and to my friends Mr Frederick Chapman, A.L.S., Hon.F.R.M.S., F.G.S.(Vic.), Professor S. D. Porteus of Hawaii, Mr H. R. Balfour, Mr S. R. Mitchell and Mr E. S. Lackman, for so generously lending photographs for reproduction. The map entitled "The Mantle of Safety" was kindly supplied by the Australian Aerial Medical Services; the end-paper is designed by Mr J. A. Gardner, one of the two artists with whom my latest trip to Central Australia was made.

R. H. C.

Impressions of that immense country generally referred to as the Inland vary markedly with each visit. I have had four trips into the centre of it and have gathered just about enough knowledge to show me the folly of being dogmatic. Its very size makes judgment hazardous. A cattle-station there may be greater than a European country; one in the north-west contains nine and a quarter million acres. I came one day to a more southern station the area of which was several thousand square miles. "Where are your men?" I asked. "Down the paddock," returned the manager. "Whereabouts?" I continued. "About seventy miles away!" was the staggering reply. Another man, the lessee himself this time, told me that his front gate was, in a direct line, eighty miles from his front door.

In those vast spaces the observer, if he is not altogether egoist, feels himself reduced to the insignificance of an ant. Kipling has said that an admiral knows a midshipman much as the Almighty knows a black beetle. Stand on one of those seemingly boundless gibber plains, the horizon of the whole circle as unbroken as if you were far out on the ocean, stand there if you wish to know your own proportion in the scale of the visible world.

England and Wales together contain less than 60,000 square miles, France has 213,000, all Germany is no more than 184,000; our Northern Territory alone has 523,000 square miles. In area the closest match for Australia, as a whole, are the United States of America with their 3,027,000 square miles to the Commonwealth's 2,975,000.

Who then is going to say he knows all Australia sufficiently well to write with authority about its scenery, its life, its past, its future? Certainly not the visitor from abroad, the typical tourist who remarks, "Paris? Yes, we did Paris. We spent ten hours in Paris!"

So, despite my six months' residence in the Inland and the travelling I have done there, I claim no more for these notes than that they are first-hand impressions by one who has moved much about his native land, loving it more the more he sees of it, hoping that some day this "last Sea-thing dredged by Sailor Time from Space" will solve all its problems, not the least being the effective settlement of the great spaces of Central Australia.

ROBERT HENDERSON CROLL.

I First

Impressions

II Old Man River

III The Train and the Alice

IV Transport Problems

V Opal

VI Mica

VII Henrietta and the Artists

VIII Far Back

IX The Ameliorator

X Fact, Myth, Legend, Gossip

XI Some Notes for the Tourist

XII What of the Future?

XIII Hermannsburg

XIV Hunting the Relics

XV The Living Aboriginal

XVI A Note on the Half-caste

XVII The Quick and the Dead:

Some History and a Suggestion

Illustration 1

Uncivilized

Illustration 2

Close View of a Gibber Plain

Illustration 3

Red-gums in Bed of the Todd River, Alice Springs

Illustration 4

The Dry Bed of the Finke River

Illustration 5

The Finke In Flood Near Hermannsburg

Illustration 6

A Glimpse of Palm Valley

Illustration 7

Section of the Macdonnell Ranges, Near Alice Springs

Illustration 8

Heavitree Gap and Railway (Todd River), Alice Springs

Illustration 9

Alice Springs and the Wall of the Macdonnell Ranges

Illustration 10

Crossing a Dry Lake-bed

Illustration 11

Post Office and Commonwealth Savings Bank at Coober Pedy

Illustration 12

Kangaroos in Action

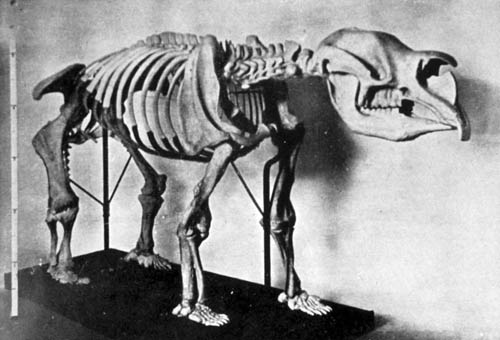

Illustration 13

Restoration of a Diprotodon Skeleton

Illustration 14

The Dingo

Illustration 15

The Brolga (Native Companion)

Illustration 16

Pool in the Finke at Henbury Station

Illustration 17

Vertical Strata, Finke River Cliff, Near Hermannsburg

Illustration 18

A Claypan Near Oodnadatta

Illustration 19

The "Mantle of Safety"

Illustration 20

Cobbers

Illustration 21

Camels in Harness

Illustration 22

Residual Hills, and the Gibber Resulting from Their Detrition

Illustration 23

Standley Chasm

Illustration 24

Glen Helen Gorge (Finke River)

Illustration 25

Processional Caterpillars on a Walkabout

Illustration 26

Mulga-ants' Nest

Illustration 27

Mulga Killed by Drought

Illustration 28

The Wilderness Blossoms

Illustration 29

Feed Aplenty

Illustration 30

Clearing Railway After Dust-storm (Near William Creek)

Illustration 31

A Dwelling at Hermannsburg

Illustration 32

The Author and Some Tribal Relatives (A Bultara Group)

Illustration 33

Yarumpa the Honey-ant

Illustration 34

Professor Porteus and Author in a Tributary of The Finke

Illustration 35

A Group Of Luritjas

Illustration 36

Corroboree Dress

Illustration 37

"Black, but Comely"

Illustration 38

"Civilized!"

My first Inland trip was made in 1929, my latest (I will not say last) in 1934. Between those I managed to squeeze in a shorter journey, as far as Marree, in 1930, and another, the longest of all, in 1933. I have seen the land resting in the arms of a five years' drought and I have seen it working overtime in production after satisfactory rains. To take the experiences of a single visit as typical of Central Australian conditions is to accept a solitary brick as a picture of the house it was taken from. Read the accounts by the early explorers: where one found a sandy or stony desert and lost his cattle through want of feed, the next lost his beasts in amazing growths of herbage. The term "desert" has been too freely applied to much of this country. No place is a desert (in the generally accepted meaning of that word) which will produce a plentiful vegetation after rain, and a great deal of the Inland, given moisture, is amazingly prolific.

In 1929 Professor Porteus and I saw what a practically rainless five years could do. The sight was a dreadful one. It was, as I remarked at the time, as though Life had taken one look at the place and gone away again. Porteus, fresh from the lushness of Hawaii, thought it would be well if rain never fell here again, for then no one would be tempted to stay in such a spot. We counted eighty-four dead cattle on the margin of a small depression which had once contained water. Each carcass was complete save that hollow sockets represented the eyes—it was a desiccated hide containing a skeleton.

The crow, ever hungry, ever crying his woes aloud, seemed to proclaim himself the only creature to survive. "What that pfella crow eat?" I inquired of an Arunta native. "Eatem bone!" came the response.

But even in those appalling conditions the white settlers hung to their holdings, their diet mostly hope. Apart from the fact, the all-important fact, that rain will assuredly come again and with it probably prosperity, apart from this and the even more pregnant matter that to desert the holding may be to abandon every penny of one's capital, there is frequently a genuine affection (that is not too strong a term) for this stern land, an affection the basis of which is difficult indeed to define. Those limitless plains, the changing mirage for ever playing on their edges, the scarlet sand-hills against the powdered blue of the great mountains, the thousand-mile rivers of sand, the clarity of the air, the amazing sense of space—these produce that strange fascination which many a visitor, no less than the permanent resident, has felt and must continue to feel. Professor Gregory, in his Dead Heart of Australia, confesses to knowing it: a winter never passes but I personally am restless under the urge to return.

On that 1929 trip I summarized my first impressions as I gazed at the scene. We stood on the bank of a dry river. "The last time we had rain enough to see it run," said the local man, "was in 1921. I dug a tank then. It's still empty!"

Seven years of drought!

I looked round at the loose red sand which rose and fell in billowy ridges, like waves, until it merged into the skyline. I noted the few stunted ashen-grey bushes which punctuated these blank pages where seemingly no living thing had written a single other character, and I marvelled that man had ever bothered to come to so obvious a desert.

Red-Gums in Bed of the Todd River, Alice Springs

"Does anything ever grow here?" I asked. The question was purely rhetorical, but it brought a reply. "Grow here!" It was a younger man who spoke. "Grow here!" He waxed suddenly enthusiastic. "I've seen it in a good year with herbage that high" (he hit his thigh). "Beautiful! You'd have wanted to get down and have a feed of it yourself!"

And those extremes seem fairly to represent the so-called "dead heart."

It had been raining at Quorn, that sturdy little town where the Central Australian railway leaves the east-west line, but from there on to Oodnadatta the land was a waste. For hundreds of miles the plains lay bare as a sandy beach at low tide, or at best stippled with dust-coloured spinifex or its like. It was then that my professorial friend from abroad remarked that men should not be encouraged to try to settle here at all.

The outlook certainly justified the thought. But this country is such a mass of contradictions that one can understand a man, once in it, being reluctant to leave. The gambling element, so strong in most of us, comes into play. At the moment of writing, despite the fact that feed had disappeared altogether from such a huge stretch of country, fat cattle were being entrained at Alice Springs, itself as dry as a bone, and certain graziers were doing well out of the prices the animals were bringing. Their good fortune lay in the fact that a smart fall of rain had occurred some sixty odd miles east of "the Alice" and their properties were lucky enough to share it.

Outside that area the tale was one of ruin and despair, of herds destroyed, of living made almost impossible. The loss in cattle must have been enormous. The Finke River Mission had 3000 head at the beginning of the drought; at the end it had a dwindling 200. On a small flat near one of the rare springs lay numbers of carcasses. Queer, ghastly things they were, which had once been cattle. A moistureless air had mummified them.

On the Rudner Plain, out towards the Glen Helen Gorge, a grim humorist had lifted a horse and leaned it against a tree, where it stood like a figure from an Australian Dance of Death. Its grinning head was twisted round as if it watched you; but there were no eyes in the sockets which stared so fixedly across the sandy wastes.

The crows must have fed full earlier in the drought; now they looked as ravenous as the rest of the living things in this rainless region, including man.

"Hangry!" said a naked Luritja, passing his hand across his stomach. He meant hungry. It was his one English word.

They tell you tales here of how the herbage grows when the rain comes, of how the Finke rose in 1924 and all but swept away the Hermannsburg Mission buildings, of the natives waxing fat on euro and wallaby and rabbit (the rabbit has come as far as this); and you watch the shifting sands where no wild thing moves, you gaze at the depression which is the dry bed of the river, and you wonder if it can be true.

Bright day succeeds bright day, the nights are fresh, the dawns as lovely as one could wish, the sunsets a rich yellowing of the cloudless horizon. Every morning the south-east wind goes about its business of making sand ridges, the Hermannsberg glows red in the sun; there is no suggestion that rain has ever fallen in this wilderness.

And, to complete the picture, across the Missionary Plain comes, slow pacing, a train of forty camels with tinkling bells and Mahomet Ali leading the way.

But the long-delayed rain must come at last and Old Man River be alive again. I caught myself singing at the thought of it:

Ol' Man River,

That of man River,

He must know somethin',

But don't say nothin',

He just keeps rollin',

He keeps on rollin'

Along!

Yes! the Finke is running! And what does that mean to most of the seven million (or so) inhabitants of the continent it runs in? Nothing at all, for Australians generally do not know that such a river exists.

Yet it is the largest watercourse in Central Australia and its behaviour is of vital interest to those white people who have settled near it, to say nothing of many native tribes. The Arunta nation called it Larapinta, meaning "flowing water," and Baldwin Spencer suggested that a fitting name for Central Australia would be Larapinta Land.

J. J. Waldron, who did a great deal of exploratory work in that region, estimates the length of the Finke as at least a thousand miles, but states that the whole of its course has never been followed. Surely no more extraordinary stream exists. The geologist may know the reason, but to the layman it is hard to understand why a river should run at a chain of mountains instead of from it. The Finke is like the Irishman of legend—wherever it sees a head it hits it! Rising to the north of the Macdonnell Ranges, that great east to west barrier, the Finke accepts the challenge, hurls itself at the most formidable parts and eventually emerges on the south side through gorges of great beauty which it has cut in passing.

Then it wanders off into the wilderness and, as an aviator reported recently, "when last seen it was heading for Lake Eyre."

When I first stood in the bed of the Finke at Hermannsburg it held everything a river should have, except water. No Sahara was ever drier than this wide, irregular depression paved with sand and stones. On the high banks and on scattered ridges grew some fine red-gums. Flood-marks showed here and there, but not a drop of moisture—the last rain had fallen years before! The nearest water was five miles away at the Korporilya Spring. It doubtless supplied the few small birds which twittered in the trees, and the crows which cawed perpetually about the mission station.

"You eatem crow?" I asked one of the Arunta tribe. "Aua," he replied, signifying that he did, when he could catch them. They looked anything but edible; I felt like the American who said he could eat crow but he "didn't hanker arter it."

It was from the bed of the Finke, where I was watching the ceremonial dances of a group of naked Luritjas, that I was suddenly transported to childhood days in a Victorian country town. Through the monotonous chant of the old men, and the clack of the sticks and stones with which they were beating time, came breaking in the liquid "tip-tip-top-of-the-wattle" of a Crested Bell-bird's song.

At the famous Glen Helen Gorge, too, the magic carpet of memory operated once more at the call of a bird. The Finke has formed a deep brackish pool there by the foot of tall cliffs—so deep that even a five years' drought could not exhaust it. A bunch of reeds grows at the edge and, as we paused, a Reed Warbler gave voice, at our very feet, to that wild, compelling song of his, all rapture, that may be heard any spring by the Henley lawn on the Yarra near Melbourne.

A third bird-note was also a home voice in strange surroundings. That wonder-spot of the Centre, Palm Valley, is, we are told, a reminder that once upon a time climatic conditions were very different in the heart of Australia from what we know to-day. Exploring its delightful groves and luxuriating in its pools of fresh water under tropical growths we saw the flutter of a wing and next moment came the melody of Harmonica, the grey thrush of our Victorian bush, or a very close relative.

To reach that valley we followed the Finke in its cutting through the James Range and later, on camels, travelled down its bed for a good many miles. Save in the Valley, nowhere was there water; but in the long windings between the hills were numberless places suitable, it would seem, for embankments to conserve supplies of the precious liquid when rain actually came and the river was a river in something more than name. Water conservation is surely the cure for most of the serious troubles of the Centre.

Our camels paced solemnly along, making us marvel at the toughness of their lips and tongues as they snatched mouthfuls of thorny bushes, and slowly the panorama unfolded of sand and stones under high cliffs weathered into the quaintest shapes. Here was mulga, there a hillside of spinifex with good samples of eucalypts, their size suggesting that somewhere below the arid surface lay nourishment to their liking. At the entrances to gullies between Palm Valley and the Glen of Palms were occasional sentinels or groups of Livistona Mariae, the palm peculiar to these regions, and the smaller Zamia palm frequently hung from rocky crevices. A few fig-trees made a change of green at a crossing.

Occasionally a bird would call or be seen. Commonly it was the Mudlark, but now and then it was a parrot, hard to identify, a Willy Wagtail (the "titchi-ritchi-ritchi-ra" of the natives) with all the impudence of his southern relatives, or a hawk. Once we flushed a pair of quail, but bird life was not plentiful and of euro or kangaroo or wallaby we saw little trace. The noticeable tracks were those of the large goanna called by the natives pirinti. At a spring we saw the backbone of one of these reptiles—all that had been left by the blackfellow who had eaten him.

By the Lartna-tree near the Willy Wagtail Spring we passed a night that I shall long remember. A lengthy search for water had ended happily at this pool. The camels, hobbled, had been turned loose to pick up what they could; the little fire of Terence, an Arunta man, glowed in the young dusk; behind us stood, in solemn grandeur, grotesque peaks and turrets, their crests warm-red in the last of the sunset; before us rose a hillside which changed from grey to gold as the moon climbed up and flooded the heavens with soft light. The earth was warm and dry, the air crisp and cool; the tinkling camel-bells made a lullaby; we slept till the dawn came up even more beautiful than the night.

But the rain has come, and where our camels made their broad tracks on the windblown drift the welcome waters are racing, while along the banks the green herbage is rushing astonishingly to its full stature. The cattleman is rejoicing, despite his depleted herds, for here is his means of living restored to him, and the blackfellow will no longer know hunger with the immediate reappearance (miraculous beyond belief) of fish and frogs and other vanished game. Moreover he may now defy the dreaded scurvy which took such a toll one year owing to the absence of vegetable foods.

Old Man River don't say nothin' but he certainly does know somethin'. When the Finke moves he works miracles.

When Professor Porteus and I made our first trip we used the railway as far as Alice Springs, roughly a thousand miles north of Adelaide, before hiring a motor-truck to take us some ninety miles west. That meant a South Australian train as far as Quorn, a comfortable little town sitting at the foot of the Flinders Range, and there changing into a Commonwealth train, which completed the journey in another two days and three nights of continuous going. Our fellow passengers were an education in this new world of the Inland. A brown-faced constable of police was returning from a vacation spent at the distant seaside—we learnt that his "beat" covered many hundreds of miles and that a single case might keep him away from headquarters and in the field for two or three months at a time a couple of prospectors had been to the city to float a silver-lead proposition—the only trouble being that the mine was 300 miles from the nearest water; a Catholic priest was taking this 2000 mile route to Darwin—the "top end" as Darwin is always named in the Centre; several doggers dropped off at lonely stations to resume their pursuit of the dingo—7s. 6d. apiece is paid for scalps; late one night we delivered a sleepy schoolboy to his parents—the lad had come some 900 miles to be at home for the holidays; cattlemen talked of droughts and good seasons, opal gougers of the luck of that calling, mica miners spoke of the getting of their curious mineral and the difficulties of its carriage from the Jervois Range, and elsewhere, to the railhead—it was truly a new world we had entered.

We passed through Marree (Hergott Springs), still largely the home of the camel, we reached the Lake Eyre basin, that vast depression which is lower than sea-level, then we started to climb towards the blue Macdonnell Ranges, standing, an east-west barrier 300 miles long, right across the fairway. Heavitree Gap, cut by the Todd River, lets the traffic through, and two miles to the north of the Gap is Alice Springs. The Alice is only a few miles from the Tropic of Capricorn but the snug little township, cuddled by the hills about it, is some 2000 feet above sea-level, so knows frosts as well as a tropical sun. I have seen the water frozen there in May and I recall the experience of one of my friends who, camping in that neighbourhood, put his false teeth in his quart-pot for the night and found them in the morning grinning at him through a couple of inches of ice.

The Dry Bed of the Finke River

The Finke In Flood Near Hermannsburg

I fell in love with the Macdonnells. The best season in which to see them is winter. Here is a note written on the spot in that season (May 1934), a note which does all too little justice to their rare charm:

For early morning beauty I am prepared to

uphold the claim of the Macdonnell Ranges against the rest of the

world. It is true that I have not seen the rest of the world, but I

feel in this matter much as the old physician did about the

strawberry: "Doubtless God could have made a better berry, but

doubtless He never did." Looking up from my writing for another

view before the splendour fades, my first impression becomes

conviction that surely nothing better than this has been

created.

We are camped on a flat between the public well and the railway

line. Behind us, to the north, lies the township of Alice Springs,

capital of Central Australia, about half a mile away. Roosters are

crowing there, and a drift of white smoke from the first of the

breakfast fires is spreading slowly down the valley of the Todd,

scarcely moving, and keeping very low. Fine white-stemmed gums in

the middle distance add greatly to the value of the picture.

But it is to the south that we turn with assured expectation, for

we have been here now five days, and no morning yet has

disappointed us. Some two miles away is the great wall of rock

pierced by the gateway known as Heavitree Gap, and ending, from

this aspect, with the abrupt peak of Mount Gillen. It is Gillen who

first sees the sun. The flat is still in shadow, there is no hint

of colour at our level, when Gillen suddenly flushes

pink—like the Sultan's turret he has been caught in a "noose

of light." Rapidly the glow extends. Between looking down and

looking up, the crest of the range has reddened from end to end and

the pure tone is flowing downwards to the base. Now the whole line

of the mountain is rose-pink, shining as if lighted from

within.

Not a breath of air is stirring. The trees stand as if asleep. In

keeping with the peace of the scene a Jackeroo Bird, the mellowest

singer of them all, pipes a few perfect flute calls, and a near-by

magpie croons quietly as if for his own private ear.

A crow strikes an unexpected note of humour. Crows are everywhere

about the outskirts of the town, white-eyed, well groomed, always

hungry. A capable musician should compose the Song of the Crow: it

is astonishing the variety of notes the bird has. This one is

apparently attempting a rendering of "Hark, Hark the Lark!" He gets

as far as "Ar-cark-ca-cark," but wisely stops at that. My sympathy

goes out to a bird with such ambitions and such a voice!

One of the taller trees has caught the light and all at once our

shadows lie stretched on the ground before us—the sun is

here! From far away comes the noisy gossip of a large flock of

Galahs. Louder it grows until they are passing right above us,

heading, every morning, towards the Gap. When they fly high their

wings fairly twinkle and they flutter like pink petals against the

blue. Almost invariably a few drop lower to examine us and, as they

settle, the dead bough they have chosen seems suddenly to have

flowered. With much arching of crests and sotto voce remarks

they stay for awhile, then, as one bird, they depart. We thought

Galahs could not fly without shrieking, but sometimes an alarm call

is sounded, the babel is hushed instantly, and the flock swoops low

between the trees, travelling fast and silently for some

distance.

Bird life is fairly plentiful, though this has been a dry season in

the Centre. Black Cockatoos flap heavily along, creaking like rusty

gates, a Whistling Eagle calls not unmusically, and sails by on

steady wing, the Crested Bell-bird, most ventriloquial of singers,

defies you to say whether he is near or far, those handsome

creatures the Ulbujas, better known as the Port Lincoln Parrots,

display their sleek dark heads and golden collars as they feed in

the higher branches, Babblers make strange cat-calls, hopping

distractedly about as they do so, trim Soldier-birds come

fearlessly for scraps, and Red-eared Finches wheeze in their funny

asthmatic way, often alighting within a few feet of us.

A soft tinkling comes from the rear. We turn to see a luminous

cloud against the eastern light, the dust raised by the sharp

hooves of the town herd of goats. Very picturesque they

arelong-horned and long-bearded Billys, sedate matrons, frolicsome

kids—of every age and every colour. Marching placidly with

them are a few sheep and, moving them on as they would pause to

snatch a mouthful here and there, are two aboriginal women, walking

with the ease and grace of carriage for which these people are

famous. They call to their charges and to their three dogs in

rapid, soft Arunta, and the herd passes, in a golden haze, to feed

somewhere to the west and return at sundown.

The Alice is awake. Domestic sounds come from

the dwellings to remind us of the homes we have left a thousand

miles away. To close the eyes for a moment is to forget that the

city is no longer with us; to open them is to see a team of camels

stalking solemnly past.

But the range—the range is the thing! You turn to find that

the warm glory has gone; a new tone has taken its place. The whole

long line of hill has come forward a step; every detail of rock and

tree is now so plain in the clear air that you doubt the knowledge

that they are so far away. Presently the colour will change again

and towards the end of what, to Alice Springs, is a typical winter

day, bright and sunny, the bold escarpments will take on a faint

powdered blue which grows deeper and richer until they are no

longer a definite mountain chain, but merely a sombre line at which

the stars cease.

Only one thing is more beautiful than the fading light of evening:

it is the miracle of the morning.

Good as the travelling is on the homely and friendly Commonwealth train, where the officials treat you as a long-lost brother, yet the best way to make intimate contact with the Inland is by motor-car. With it you may stop where you like and as long as you like and, best of all, you may see the folk of the solitary stations in their home surroundings and are afforded opportunity really to know a people who are surely the most hospitable in the world. Naturally you halt your car at each one of these outposts. Until that first unfortunate gold rush to The Granites drew a host of undisciplined people along the tracks—people who thought it proper to shoot at every creature that moved and whose general behaviour was, to put it mildly, boisterous—until the back-country people had that experience they welcomed all who passed. To-day the memory of the sorry invasion is dying and again the traveller is esteemed. I have called at a house intending to stay an hour and have found myself still there at the end of the next day. The people are kindness itself and there are often evidences of culture which one does not expect to see so far removed from towns. Good pictures on the walls, nice china and glassware, a library that would be notable in any city home—these are no unusual objects where difficulties of carriage alone would seem to forbid the possibility of their presence.

But the train is by far the easier way, if only because it provides meals and beds and no difficulties. In the car you must carry extra water, extra petrol and much food and be prepared to sleep in the open. Rivers whose dry beds are full of sand and stones, and sandy ridges rising one behind the other in quick succession, are obstacles which compel respect and occasionally beat the car completely. The country is so big, too. Very few people, including the native-born Australians, seem to realize its size and that in it one may easily be hundreds of miles away from the next human being.

Most Australians, of course, live on the edge; they know little or nothing of the interior. It is so vast that the quoted figures are difficult to grasp. To say that twenty-five Englands could be dropped into the Commonwealth without occupying all the room is impressive enough, perhaps, as is the equally true statement that Australia is of almost the same area as the United States. But those assertions evoke only a mild wonder. They produce much the same effect as is gained by saying, what is also true, that there are cattle-and sheep-stations which contain 10,000 square miles of country, or that on one of these stations 160,000 sheep are shorn.

It will be remembered that Mrs Aeneas Gunn records in that splendid book We of the Never Never that as her station home on the Elsey was first sighted by her "we had left our front gate forty-five miles behind us." The word "gate" is used metaphorically. One may travel many hundreds of miles over leased or freehold country without encountering a fence. To the passer-by there are two prime mysteries—how the proprietors know their boundaries, and how the stock on adjoining runs are kept separate. There is a key, to each of these conundrums, and every bushman possesses it.

A motorist who departs from the beaten track in the Inland does so with a certain amount of risk. In a journey of 4000 miles, which embraced some unusual places, we calculated that eighty per cent, at least, of the going might be classed as good. But in the remaining twenty per cent were some bad patches. A breakdown fifty or a hundred miles from the nearest house may be very serious. One can easily understand why some routes are labelled on the maps "Two-car tracks." Safety first would be one way of translating that; elaborated, it means that two cars would probably get through where one might stick.

A car driven by a Sydney woman, whose sole companion was her daughter, came to a full stop at the Arthur River in the Jervois Range. Nothing would make it go. A lonelier spot could hardly have been chosen. The girl, with great courage, set out on a walk of thirty miles to the nearest house, accompanied only by a dog. Strangely, in that unpeopled place, she met a man. He was a blackfellow, an aboriginal who—we were told on passing through—had escaped from an island prison in another State and had wandered thus far inland. Whatever had been his misdemeanour it could not have been of a very harmful character, for he took the girl in charge and proved a veritable good Samaritan. She arrived at her destination and a car was sent out which retrieved the other.

The owner was lucky. The Arthur River is notoriously difficult to cross. There is a double channel and, as we saw it then, it was waterless and deep in sand. A steep descent, a smart dash across a short channel, an equally steep pull out, and we found ourselves on a narrow neck overlooking the next and much wider river bottom. It was most discouragingly strewn with discarded coco-nut matting and narrow strips of wire-netting, the relics of struggles by other cars to traverse this slough of despond. Moreover, to depress us further, a serviceable double-seater car stood melancholy, deserted, about two-thirds of the way across. We tried to take the sand in a rush, using some of the old netting at the first of it, but within a few more yards the wheels were whizzing round without progress. Our two cars held eight people; with seven pushing and one at the wheel, we made the other bank. Then we repeated the operation—no easy one—with the second vehicle.

Section of the Macdonnell Ranges, Near Alice Springs

Our most serious trouble was the breaking of an axle. That would be the end in most cases, but our driver had come prepared with spares. Moreover, he was an expert mechanic. Thoughtfully—or so we said—he had contrived that the smash should occur at the end of the day. We camped and he went to work, with assistance from others. By ten o'clock next morning we were on the road again. Forlorn indeed is the picture of a car, its fires extinct, its owners departed, standing on a wide gibber plain or in a belt of river sand or "bull-dust." We were to see several such derelicts, and each evoked speculation. Occasionally we were able to learn something of the history of the breakdown. For instance, the Ford that waited dustily on the side of a western Queensland track had been used in an attempt to convey a group to a dance at the distant township, but had acquired incurable tyre trouble. How the would-be revellers fared we could not discover, but we were told at the township that a rescue party was going out to recover the car "some day."

Irrecoverable was a weary-looking trailer from which most of the detachable parts had been taken. It was a depressing sight. Curiosity about it could not be satisfied. Nor was there any hint of the cause of the fire which had destroyed a large motor-car at a spot even more remote from human habitation. Whatever the cause, no one could suspect deliberate intent when the immediate penalty must be a desperately long tramp over dry plains before food and shelter could be reached. Perhaps the most likely vehicle to be rescued ultimately was a two-ton truck which had incautiously run into the overflow of a bore and become bogged. It appeared to be in excellent condition.

These casualties recalled that East and West sometimes meet in Central Australia. There are occasions when the camel, so early man's beast of burden, may be seen yoked to a motor-car, almost the latest of human devices in travel. Australia presses most forms of carriage into the service of His Majesty's mails. A line of cattle-stations on a certain inland river still greets a monthly mail borne on the backs of camels, which travel some 400 miles on each journey. Other parts rejoice in an air service. But the motor-truck and the motor-car are perhaps now the most used means of transport, replacing many a slow-moving camel team, which could cover no more than about thirty miles a day. That is all to the good, but the camel, which nothing short of flood can stop, has his revenge when that worst enemy of the internal combustion engine, the shifting desert sand, decides that the car shall not prevail for once. Then it is that the mailman is lucky if he can obtain the help of one or more of the ungainly beasts to haul him and his helpless car across the dry creek or over the sandy ridge.

On another car trip, this time with my friend S. R. Mitchell, well-known as a geologist, and a young friend of his named Ray Golland, we drove from Melbourne to Broken Hill and so to Marree. Some of the minor incidents of that journey have fixed themselves firmly in my memory.

We had come through the Flinders Range to find ourselves at Parachilna, a station on that great railway line which begins in Adelaide and ends under the shadow of the Macdonnell Ranges at Alice Springs. Swinging round, we headed for Marree, for there I had to catch train back to the greener south, while my two companions took the Birdsville track for Mulka. There had been no rain for many months. Sand alternated with gibber; vegetation was represented by occasional starved-looking trees. Coming as we had by dry back-country tracks where settlement was far to seek, we carried supplies of water against emergency, so the fact that the creek we reached at nightfall had no sign of moisture did not deter us from camping. We spread our sleeping-bags in its very bed. Above us was the bridge supporting the railway. It supported more than that; every space between the sleeper ends held a nest, some with eggs, some with young ones, while the parent birds flew twittering about protesting at our presence. With the falling of the night peace came again to the little colony, and our camp-fire seemed the only living thing in that immense area of earth and sky.

Heavitree Gap and Railway (Todd River), Alice Springs

The quiet was remarkable. Only when the city man reaches such solitudes does he realize that his customary life is spent amid ceaseless noise. The wounds of sound were healed by silence; we found ourselves instinctively speaking in low tones, adjusting ourselves to the surroundings. But from far and far away, scarce heard, there rose a murmur, so low as to suggest rumour rather than reality. We sat expectant, but it died away. Again it came, this time as a singing, a faint, faint singing in the rails overhead. "A train!" said someone. Content as we had been, here was an event, and we hurried out to see it. The railway there is as straight as a spear for more miles than the eye can follow. For long the noise gathered and grew before anything was visible, then a little eye opened and grew greater till it shone as a mighty headlight blinding us to what was behind it. With a roar the train passed by, and the rails fell gradually quieter till at last even the faint whispers ceased. We wondered what the nesting birds had thought of it! Doubtless they had grown accustomed to this recurring wonder. No sound came from their homes as we made our beds and settled to sleep.

Morning saw the miracle repeated which for us had never staled in these wide spaces of the interior. This time it was more impressive than ever. Stars were still showing as we woke, but the east was even then full of the promise of the dawn. A low haze made the surface of the earth a nebulous thing, a mystery; above it hung a small clear pool of light, the harbinger of the sun. But he was far below the horizon as yet, and we were to see, before he appeared, the preparations made for his advent. The green of emeralds and the glory of cloth of gold were spread before him, the colours so pure and fresh as to be the eternal despair of any, even the greatest, of our artists. Then royally he came, and at once, fully and wholly, the day was with us. Under that searching light the mists vanished and the land stood once more revealed as a desert. But that it is no true desert has been told by many, and we also were to be given proof that this sandy waste is a potential garden. Twenty-four hours after we left, the rain came; a fortnight to the day my companions returned to the same camping spot. The creek had subsided, the bed was as dry as before, but in the blackened ring which marked where our fire had been stood a plant, eighteen inches high, in full flower. Nature has to hurry here if the species is to be perpetuated.

By midday, after a pause to extract from a tyre what was surely the only headless bolt lying on the track in the whole 2000 miles between Adelaide and Darwin, we saw Marree on the plain, and drew up to a civilized meal, a meal eaten at a table. There is little of the typically Australian in one side of Marree, for that portion is altogether Afghan. Camel-breeding and the carriage of goods by camel were for very many years the two industries of this township, once known as Hergott Springs. It is said that in its best days, before the motor-truck spoilt the carrying business, there were some 1500 camels about the place, and that a good beast was worth more than £100. Now they are, if not exactly a drug in the market, at least very easily obtainable. Indeed, they are running wild—"wild as rabbits," said the half-caste with whom I travelled on the homeward trip. He added that the authorities had found the strays such a nuisance that they had recently rounded up eighty of the big animals in a corner and shot the lot! In the main street of Marree I stood and gave a soured blessing to my friends as they turned the car on to the Birdsville track, hastening to overtake the mailman on his fortnightly trip. At a certain point he was usually assisted by camels to cross some bull-dust, and they hoped to share the assistance. They were too late, but they managed the crossing unaided.

I watched till their dust died down, then turned to the comfortable two-story hotel for dinner and bed. "At one stride came the dark," said Coleridge of the tropics, and twilight was very short here. By nine o'clock I was ready for sleep; the homeward train left very early next morning. I approached the landlord, "I'll do your room," said he, grasping what looked like a spray pump with a tin canister attached, and preceding me up the stairs. My bedroom, I noticed, had fine-mesh netting on the windows. Closing the door, mine host proceeded to spray, methodically and thoroughly, the walls and ceiling till the air was full of the highly volatile substance used. "There!" said he. "You'll have no mosquitoes now!" He was right. When he called me in the pitch black of earliest morning I had slept undisturbed, though this had been described to me in Melbourne as the worst place in the world for mosquitoes. Across rails and tripping wires I stumbled, burdened by a suitcase and a swag loaded with aboriginal implements, till the station loomed up, a still darker patch in the general blackness. Slowly, very slowly, the official world awoke. But there was still no glimmer of daybreak when the train rattled out of the yard. There was also no light in the carriage, so for many miles my two neighbours were no more to me than voices.

The gloom in which we sat gave us perfect conditions under which to watch the coming of the day. A thinning of the shadow on the eastern edge of the world was the first sign. An horizon became indicated. We grew aware of dark shapes of trees or little hills. The light extended upward, and the lower stars, brilliant till now, began to fade. Colour crept in, the faintest of pale ambers, so delicate as to be barely visible. It spread and deepened, and the sky above was, quite suddenly, a clear blue-green. The changing was so subtle that one knew it only in result and never by seeing the actual movement. Now the land was wholly in view, but with every harshness removed, a certain unreality, a soft greyness, wrapped tree and rock and level space. Even as we dwelt upon it, that, too, changed, and there was the sun, smiling upon a new earth. His coming seemed instantaneous; one moment he was out of sight, the next full-risen. It was then I knew what Kipling's soldier meant when he said: "the dawn comes up like thunder." What did the day matter after that? The south-easterly blew, the sand came filtering in to rob us of comfort, two passengers passed a convivial bottle round, each in turn drinking from its neck till some of the company were merrier than wise—these things were the ordinary incidents of daylight. We had seen the dawn!

No matter the mood in which you approach the amazing vastness of Central Australia you will not be human if that mood is not dominated by expectancy. After my four long trips I am still unsatisfied, still eager, still prepared for wonders.

The wonders do not always arrive: but what of that? Carlyle was not so much disturbed by the actual crowing of the cocks as by the waiting for them to crow. Anticipation and retrospect provide many of the keenest of our emotions. Always on the wide plains, their edges lost in the lakes of mirage, one knows that strange things are imminent, and even in their absence there is but little disillusionment; the sense of being is so keen that it carries over as reality.

But the natural wonders are truly many, wonders intruding themselves unexpectedly into an ordinary journey, and wonders to be deliberately sought out. This great island-continent was cut off from the rest of the world ages ago; the primeval creatures remain unchanged by intrusion and interminglings, remain at a stage in evolution long past and lost in every other land. Australia has been called a museum of living fossils and assuredly her most distinctive native creatures give colour to the term. The platypus, for instance, Nature's most freakish production, has the bill of a duck, lays a soft-shelled egg like a reptile's, has fur like a cat and suckles its young. One understands the state of mind of the new settler from overseas who described his first platypus as possessing a beak like a bird and "feathers like a 'possum."

You are unlikely to see this shy and mainly nocturnal animal on a trip to Central Australia; but kangaroos and wallabies, emus and bustards (known as wild turkeys), cockatoos and gaily feathered parrots in screeching flocks will be common sights, and at night the dingo, the native dog whose origin troubles the scientist so much, may perhaps be heard in high-pitched ululations, now near, now far, giving character to the lonely plains or the mulga forest. A characteristic of the dingo is that it does not bark.

It is a long road to the Inland from where the cities, and indeed most of Australia's population, are distributed along the coastline.

Varied as that long coastline is, it has nothing quite in keeping with the astonishing gaps and chasms which break the line of the Macdonnells and which are attracting more and more attention from tourists. With Alice Springs as a base, several of these great fissures may readily be visited—Standley Chasm is perhaps the most remarkable of them all. On our first visit, Professor Porteus and I found that this water-worn crevasse was still unnamed. We acted as godparents and called it Standley after the Mrs Standley who had been in charge of the half-caste home at the Jay River and had been the first white woman, we were told, to venture up this wild gorge. The naming was duly accepted by the authorities.

On the Inland way has been passed, but far out of sight over the western horizon, one of the greatest single stones in the world—Ayers Rock. It is a pebble lying all alone on the floor of a sandy desert, a pebble one and three-fifths of a mile long, seven-eighths of a mile wide and 1100 feet high. On the western side, too, are the Henbury Craters, deep holes created by a fall of meteorites in the far-off times before the white man came to those solitudes.

To visit places such as these needs special conveyance. Some may be reached by car, but to others the only way is by camel. The motor-car has done much to cut down distance in the Centre as elsewhere, and it was by car that we approached one of the strangest of settlements, a village of troglodytes which the aborigines have named Coober Pedy, "Coober" being, their word for "white fellow," and "Pedy" for "a hole in the ground." The map-makers call it the Stuart Range Opal Fields. The blackfellow title is the more descriptive, for here every one lives in a dug-out.

This was my second visit. I had been unfavourably impressed on the first occasion; this time I was accompanied by two artists, an oil painter and a water-colourist, who had also been there before and who assured me that I would live to repent my first judgment. They were right.

From our own little State of Victoria, down in the south-east corner, we had come to Coober Pedy by way of Port Augusta, a brisk town at the head of Spencer Gulf in the neighbouring State of South Australia. Here the east-west railway line begins in earnest its 1500 mile journey to Perth, the most westerly of the Australian capitals. One section of this line, by the way, crosses the Nullarbor Plains, a perfectly straight and perfectly level stretch for 300 miles. We followed this iron route for some 200 miles, then turned north, through cattle-station after cattle-station ("ranches" in America) whose unfenced boundaries cause the traveller to wonder what keeps the herds from mixing and how an owner identifies his beasts. Perhaps there is an explanation in the cryptic remark of a cattleman to whom I put that problem. "Well," said he, "it is not considered polite to visit your neighbour when he is mustering and branding!"

A seemingly limitless gibber plain gave us warning, with our local knowledge, that we were on the final stage of this portion of our journey. It is idle to look for the hills of the "Stuart Range;" you will find that this plain is the upper level and that the opal field lies in a valley carved out of the plateau. You go down to Coober Pedy, not up. It was dark when we reached the edge of the declivity on this latest occasion, but we knew the way and down we plunged, past the mouths of silent dug-outs in which never a light showed, past the one and only store, equally dark, round the dim bulk of a hill to the right, its curved summit outlined by the stars, and so to a fiat near the tank which the Government has provided as a water-supply.

But what was this! A row of lights shone, low down, a few hundred yards away, and there was a murmur of soft voices. Now Coober Pedy goes to bed with the fowls, so this was truly remarkable. The riddle was soon solved. Silently as a shadow falls, a man stepped out of the darkness into the circle of our firelight. He was an aboriginal: the tribe which at one time owned this as a hunting ground was on a "walkabout" and was revisiting its old haunts. For the next few days we were to see much of these poor dispossessed people, recipients now of the white man's bounty, beggars where formerly they were lords of the countryside.

Coober Pedy has no trees. That is one reason why there are no houses. Even firewood does not exist, unless the roots and tiny shrubs used by the aborigines may be so classed. We had carried wood many miles on the back of our car and had included every old discarded rubber tyre we could find along the track. Tyres produce a cheerful blaze. The month was May, beginning our Austral winter, and the nights were sharp with frost.

So we woke next morning to a tonic atmosphere, an air cold, dry and invigorating. Despite the dear skies there was no dew. Never have I changed an opinion so swiftly, or with such good cause, as when I looked round. The sun was just beginning to show behind the eastern bank; the valley was filled with a level light which transformed the torn earth until it appeared to have "suffered a sea change, into something new and strange." Every shade of soft pastel tone was represented in the dumps marking the shallow workings—pale mauves and pinks and creams and the faintest of blues and yellows, each taking its share of the light and returning it beautified tenfold. The grey-green hills sat all about "like giants at a hunting, chin upon hand," a worthy setting to a lovely scene.

There and then I recanted. I learnt, in a flash, why Stevenson could write of his Scottish moor:

Yet shall your ragged moor receive

The incomparable pomp of eve

And the cold glories of the dawn...

See Coober Pedy at dawn or at sunset if you would know the vivid charm of a strange place. The merciless light of midday reveals only too clearly the general bareness, the absence of vegetation, the scars and wounds inflicted by man in his endless search for wealth.

Alice Springs and the Wall of the Macdonnell Ranges

To our camp-fire at night came some of the old men who had drifted about many countries of the world in their more vigorous days and had now come to anchor in this harbour of hope—for to-day, if We may believe them, the place produces more hope than it does payable opal. We learnt much as they talked. Originally cattlemen found opal here as an outcrop. They worked it quietly, selling where they were little known and so keeping the field to themselves for a lucky period. When others followed their tracks the guide to the wealth below was still outcrop; later it was to be the "floater"—a piece of opal, commonly bleached to the whiteness of milk, lying loose upon the surface. Obviously these easily-moved fragments could not be altogether reliable guides, but they were better than to-day's complete absence of signs. "Now it is all stabbing in the dark," said one of our old gouger friends. "All guesswork; and you're either on it or off it—there's no in-between."

Anywhere you try in this 600 square miles of field might be good; every inhabitant assured us that there is still much virgin ground to test, and finds are still to be made. From a shallow hole one man had recently taken £200 worth of opal; on the other hand two men, working as partners, had sunk shafts aggregating 1700 feet and had put in 163 feet of drives, and for all that work, occupying many months, their return had been not more than £20. Opal, like gold, is sold by the ounce; but, unlike gold, there is a very wide range of values. "You might get threepence an ounce or you might get £50"—and we were not left in doubt that the highest-priced stuff is rarely found. It must have fire and clarity and pattern.

The deepest shaft in Coober Pedy is about sixty feet. The deeper it is found the more likely the opal is to crack and lose beauty as it comes to the light. Old Hungarian Joe, his tongue armed with the slang of the world, waved his pipe excitedly from the far side of the fire, as he told tales of the mines of his native country. There they sank hundreds of feet for the opal and took years to bring it to the surface, acclimatizing it, as it were, by resting it at various upward stages. Otherwise it would bleach and crack on exposure to the sun. With such generally shallow workings at Coober Pedy a man could work alone, and customarily did so, but occasionally there was a partnership. Sometimes a man would haul for another for the privilege of "lousing the dump," an inelegant but extremely expressive way of saying that he is allowed to take away any of the opal which has been unintentionally thrown out with the "potch" and worthless earth.

"Potch," by the way, suggests opal in the course of formation—"unripe opal," as someone called it. It is often charged with fire and shot with lovely blues and greens, but these do not gleam in shadow as true opal does.

The opal here is not the rarer "black" variety, which Americans purchase so readily when they visit Australia. That is obtained mainly from a smaller field, Lightning Ridge, in New South Wales. The buyers come from the capital cities, sit in the dug-outs and appraise the worth of the stuff offered, giving, of course, very little of the price at which they will eventually sell in their shops. I have seen a bespectacled elderly buyer bent over a table in his cave, gems spread before him, a pair of scales dimly seen at his side, the whole suggesting the old-world picture of The Miser.

Our friends told us that good finds are seldom made—but the buyers continue to visit! There are more discoveries, perhaps, than are confessed in a place where so many of the inhabitants are in receipt of aid from the Government in the form of "sustenance" or the old-age pension, aid liable to be withdrawn should there be any other source of income.

Sea-shells are a curious product of this inland village. The nearest coastline to-day is some four hundred miles away, but the gouger's pick crashes into rich evidence that once this was ocean bed. A "sea change" indeed—no more arid scene could be imagined, but under that usually drought-stricken surface lie beaches once restless with the waves of ocean. How long ago? Who knows? The transformation of the shells into opal suggests periods which to man are vast indeed, but which to Nature are as yesterday. Farther inland, about the east side of Lake Eyre, are deposits of bones, all that remains of that giant herbivorous beast the diprotodon, long extinct, which once roamed in forests where now vegetation is unknown. And in the dry centre of the continent, surrounded by a wilderness which has none but desert plants, is a glen of palms; palms found nowhere else in the world, the final vestige of a tropical period.

Change, change, and ever change, but Nature, whose motto is Ohne hast, ohne rast, does her work so quietly that we think she sleeps, or that the end of change has come because Man has arrived.

To-day there are not more than forty persons on this field where formerly there were hundreds. The depression caught the gem trade early and it has not thoroughly recovered. Most of the people are elderly—"it is too costly to move away" we were often told. A few women remain and perhaps half a dozen children, their education carried on by the government system of correspondence tuition. The mother of a family of three has succeeded in establishing a community library—reading matter is more precious here than opal—and keeps it supplied by contact with Adelaide and Melbourne.

It is rash to fall ill. The nearest doctor and the nearest hospital are 400 bad bush miles away. At the time of my latest visit there was no telegraph or wireless; if a man became sick he had to rely upon the resources of the community medicine-chest and the layman knowledge of his mates. I ricked my back and was taken to the medicine dug-out in search for plasters. I had not seen the place before. "What are those boards?" I asked, indicating a neat pile. "They are for coffins," was the reply. In the absence of a magistrate or other law official the burial takes place first; the certificate of death comes later. The little cemetery holds half a dozen graves.

When times were better a meeting was called to secure erection of a hospital. Sufficient money was obtained to get the necessary dressed timber from the far-away city; it duly arrived, but no more money was forthcoming and enthusiasm had died. Gradually that timber melted away—most of it to line dwellings or prop up drives in the mines. To-day there is no trace of it above ground.

Looking up from our camp on the flat we see cuttings in the hillsides and know them to be homes. A drive straight-in leads to a room hollowed out of the earth, a curious soft pigmented earth which hardens by exposure to the air, so the ceiling requires no supports. Wood, as already said, is scarce: when a shelf or a couch or a seat is needed the wall is cut away down to the required height, leaving the piece of earthern furniture projecting. Light, the fierce white daylight of Coober Pedy, comes in from the doorway; a protected airway opening through the hilltop, or hillside, gives ventilation. As I wandered across a hill one day I saw a can standing on end. I walked over and looked into it, to be rewarded with a puff of smoke in my face. I was gazing down a cave-dweller's chimney!

The one official is the postmaster. He is also the representative of the Commonwealth Savings Bank. His duties consist in the main of selling stamps, making up the weekly mail and handing out the postal articles when the mail coach concludes its long journey on Saturday night or Sunday morning. His uniform appears to be composed of a sleeveless sweater and a pair of trousers. Obliging, cheerful, he is at your service whenever you can catch him, but that is when he is not away sharing the general occupation of the inhabitants. Like all the people of the back country these Coober Pedy folk are the soul of hospitality and the postmaster is no exception. His post office and bank are a dug-out, which, however, boasts a padlocked gate at its entrance. Thus, and by formal notices posted outside, does it proclaim itself a government institution.

It is said that a second reason for the dug-out as a residence is that the flies do not venture into its shadowed coolness. The old query, "Where do the flies go in winter?" is answered here. I have known plagues of the small house-fly in many places, but nowhere to equal what we found in Coober Pedy. From the first warm ray of sunshine in the early morning to well into the evening dusk they buzzed and crawled and bit. No mere waving of hands would disturb them from your face; you must literally pick them from your eyes. I had to write articles for a Melbourne newspaper; it was impossible in the open till I had placed a large gossamer veil over my head and tucked the ends well into the neck of my shirt all round. That left only my hands bare and I could work.

One of our party wrote a song about the flies of Coober Pedy. As it was produced while the insects were at their busiest it cannot appear in print. A line stated, cryptically, "There's not a single fly in Coober Pedy." The refrain explained that why there was not a single fly was because each and every one of them was married—and had a large family. The torment ceases, or at least is modified, they told us, with the advent of the severer frosts.

We had grown accustomed, as we had travelled over the seemingly endless plains, to the constant mirage on the horizon; constant yet ever-changing as we approached it. Sheets of placid water, with tree-clad edges, with bays and promontories and islands, with every sign of permanence, would dissolve into thin air, only to reappear in an altered form farther on. Lake Cadabirrawirracanna, a dry depression to the east of Coober Pedy, we named the Mother of Mirages, for every morning she presented us with a fresh deception. The most imposing was a sea on which floated two great battleships, the one stern on, the other presenting a side view. Even as we watched, these monsters wavered and passed, the sea rolled up as if the Resurrection trump had blown, and only the sandy waste remained—a stage from which the scenery had been completely withdrawn.

But the old men are sitting at the camp-fire this fine night and we listen to their tales. The oldest, Joe the Squeaker, is thin and dark, active despite his seventy years, perpetually smoking or waving his pipe to emphasize his points. His accent is markedly foreign; his speech is larded with strange oaths gathered in three continents and enriched by accretions gained in mining and cattle camps all over Australia. "By crabbie!" he will explode, and leave us in doubt as to what slang word he is parodying. As he warms to a subj ect his eyes light up, he rises and tramps restlessly about and his speech comes in a torrent of mixed slang hard to understand. He had struck it rich on a couple of occasions but had got no farther from Coober Pedy than a township where a hostelry was happy to welcome a digger with a pocketful of high-grade opal. "A feller was dere mit one of dose aerplanes," he remembered. Then, with vigour: "Had a few whiskies and I vent up. T'ought it would be a horrible feelin', but Lord! I vas too shick, too bletty full! You don't kit your aunt any more mit dem t'ings! One foot on de ole terry firma is goot enough for me—and de other not too bletty high!" It was on that bout that he found himself one night so shickered that he lost his way and slept where he lay down. "I yoke der nex' mornin' and a death adder he lie alongside me! By crabbie; he vake me up!"

Post Office and Commonwealth Savings Bank at Coober Pedy

So he came back to the field again—"only one store, only one butcher, only one everyt'ing!" as he summed it up. He spoke of a digger as having wasted his all on "slow horses" and added: "He's had more breakfas' times than what he's had breakfasts."

Joe's mate, sitting quietly on the other side of the cheerful blaze, is as reserved as Joe is boisterous. We are to learn that he has a passion for statistics and for accuracy of statement. He reads everything, but prefers serious books. He tells us the latitude and longitude of Coober Pedy, its distance from various better-populated parts, its height above sea level, its rainfall and its extremes of temperature; he branches off to recall the length of Australia's longest water-pipe line, mentions the year of its construction and the name of its engineer; he corrects, courteously but firmly, certain long-cherished beliefs of ours—his memory seems inexhaustible and infallible.

He, too, has travelled much. He has been completely round Australia by sea, and once he walked the 900 thirsty miles from Darwin to Alice Springs. With humour he spoke of his own early follies, with tolerance of those of others. Once in hospital in Darwin, just conscious after a severe bout of fever, he heard the doctor remark: "Well, God and I often have a struggle for a man: I've beaten Him this time!"

And so the talk drifts on. The discarded motor tyres we had retrieved along the track, and now burnt to save our firewood, have become circles of white ash, the full moon is high above us, and the soft chatter of our aboriginal neighbours has long since died away, but the flood of reminiscence has not spent itself. We warm our guests with coffee, and reluctantly we watch them go their several ways, each following his tiny path between the dumps to his lonely cave.

Steadily the dug-outs are emptying at Coober Pedy and the little graveyard is becoming fuller. At its present rate of decline this quaint settlement will soon be no longer a local habitation but only a name, a memory on the tongue of the present generation and a mere tale for posterity.

It is said that few Australians take to the sea, that the call which drew our forefathers round the watery world has but little appeal for us. That may be so, but the implication that the spirit of adventure has died in our generation is wholly false. Travel into the remote heart of this immense continent and you will find that our division of the "legion that never was listed" has merely turned its face landwise and is as busy as ever in its pursuit of the unknown.

Mining, of course, is one of its most notable manifestations. Opal attracts many; gold still more. The wilderness is being earnestly combed for gold and numberless "shows" will be bested in country so remote from settlement that the prospector literally takes his life in his hands in going there. The horse and the camel, particularly the camel, serve him well, and if he finds a payable field, the motor-truck will soon mark a track across the gibber and over the sandhills.

It was by such a track that we went to the mica mines in the Jervois Range, north-east of Alice Springs and not far from the western edge of Queensland. The visit was part of a long excursion which, at a respectful distance, circled Lake Eyre. These mines have long been worked, but the way is still far from being the easiest in the world to follow. The drivers, coming in with their loads to the railhead, are constantly seeking better river-crossings, safer or easier or shorter routes, and at times there is a confusion of pads to choose from, not all of them usable. It was easy enough while we were running along the great overland telegraph line, ant-hills punctuating the plain on either hand, but presently it was a course from well to well, from station to station, on sandy or red-soil plains or acres of white quartz pebbles. The season was good and occasionally the Mitchell grass rose about us six feet high. The Tropic of Capricorn was crossed and, contrary to all expectation, we were glad that night to wear overcoats as we sat about the campfire and gladder still to roll rugs about us as we curled up in the sleeping-bags.

Wonderful nights of stars they were, but cold, for the tableland is some 2000 feet above sea-level.

Finches swarmed at every well, each waterhole had its pair of Whistling Eagles, and the Kite, that friendly Autolycus of the back-blocks, hovered over all the station yards. The Galah seemed to be ever with us and so was his friend the Corella. One morning, waking at "piccaninny daylight," I smiled to recall Louis Esson's excellent definition of the bush day as "magpie to mopoke," for those two birds were calling together. They had overlapped; it was dark enough for one, and light enough for the other.

Occasionally a "turkey" (the Australian bustard) would stop eating grasshoppers to give us a haughty glance, both suspicious and disdainful; the Native Companion and the emu gazed with more curiosity than fear; and kangaroos seemed to regard the car as a pacing machine, for they would race parallel, or just in front, for miles.

Scraps of mica had become common along the track, sparkling at us as we passed, and presently there showed, well ahead, the collection of tents marking the Mica King Mine. It is the centre of what is surely the most remarkable landscape in the world. Everywhere were thousands of bright eyes watching us, myriads of heliographs flashed and winked and flashed again, the whole countryside was brilliant with quivering lights. Countless shining points were in the dust at our feet, on the floor of the valley stretching before us, and scattered along the opposing hillside; as the wind blew they trembled and shivered until the earth seemed alive.

Mica is obtained in "books," the layers (or leaves) of which are as thin as paper. It fractures easily; the camp was surrounded by the remains of broken and discarded sheets. Just as with paper, these fragments shook in every breeze and their glass-like surfaces threw back the sun in dazzling fashion. The Cock-eyed Bobs or Willy Willies (the Burramugga or Rooba-roobara of the aborigines) roar down the valley, flatten the tents, and pick up the loose mica to give a remarkable exhibition as the stuff is whirled sparkling into the heavens. "Jewelled in every hole," quoted someone. We were told that for hours after the passing of a whirlwind the flimsy sheets keep dropping slowly back to earth. Often the kites, ever watchful, dive at these floating scraps as possible food. "The finest thing we have about the place. They clean up all the scraps, bread, meat, anything," was the comment of the camp on the kites.

Restoration of a Diprotodon Skeleton

An open cut shows the original workings. From it goes down a slanting shaft which swallows greedily the blood-woods and other trees used to timber the drives. Two sturdy citizens, appropriately clad—that is with as few garments as need be—were handling the windlass, lowering the timber and raising the ore. From the crest of the ridge where they worked, the view stretched to infinity save on the western side where the main body of the Jervois Range formed the horizon.

We found this camp of the Mica King a home away from home. All but two of its denizens were from Melbourne. It was an instructive sight to see our public school lads, as several of them were, adapting themselves completely to such novel and difficult conditions.

Seated in a group apart, a tiny fire smouldering in the centre, were about a dozen blackfellows. Each was armed with a knife with which he cut flaws and imperfections from the sheets of mica. (All the waste mica, by the way, is destined eventually to be ground up into face powder. Looking at the wilderness about us, so far removed from any of the graces of civilization, it was hard to picture it in connexion with the dainty toilet-tables and daintier cheeks of Beauty.) These natives declared themselves, so far as one could understand their pidgin, to be of the "Louera" tribe, seemingly a division of the Arunta. Bearded, grave, their lithe legs doubled under them, they discoursed seriously as they did their job. They were just as willing as white people to knock off work to be photographed.

A baby kangaroo, still shaky on its little legs and bleating much like a very young lamb, was the well-protected pet of the camp, and a perfectly naked black boy, of about five years of age, a model of symmetry, seemed to share its popularity. The aboriginal mother of this small youth was camped in a dug-out half way up the hillside. We visited her in time to witness the family ablutions. The tableau presented could have passed for the advertisement of a well-known brand of soap. The boy stood by, a picture of shining cleanliness, while his sister, a few years older, knelt over a basin, her head and neck a mass of lather, the victim of a furious assault by the mother, who rubbed and scrubbed with vigour. Like all children in such case she protested as noisily as she dared, but the generous masses of the soap prevented any effective outcry. We were told that these youngsters were scrubbed regularly and at very frequent intervals.

Reluctantly we left this place of many interests (the camp's second name is surely Hospitality!) and turned our cars to the Queensland road. The Jervois Range, full of scenery which assuredly will someday attract the tourist, lay before us and then the long stock-route facing homewards.

Allow me to interpolate a chapter of sidelights on a journey made with two artist friends, they in search of landscapes, I on the track of fresh material for articles as well as fresh study of the aboriginal. They had no occasion for haste, and I was in the happy position of the retired man whose office cares were over, so we made progress in a proper way, that is, leisurely. We took about a month to reach Alice Springs, a journey commonly accomplished in a few days. With rich humour they assured me that they had hurried on my account! My retort was that I would advise any one desiring a foretaste of Eternity to go on a long trip with artists.

It was a delightful three months that I spent in their company and I left them with reluctance when I was recalled to Melbourne to organize the Art Exhibition for the Victorian Centenary Council. They were then busy, a couple of miles from Hermannsburg, putting the Krichauff Range and the Macdonnells on to canvas and surrounded by a horde of young aborigines from the Finke River Mission Station.

We had many adventures, the most startling one occurring when we had been barely a week in the field.

It was a lovely day. Young Winter was trying what he could do as a maker of charming weather, and his experiment had turned out a success. Sun and clouds combined to cast attractive patterns on the landscape, and a mild dash of rain brightened everything. Even Henrietta, our caravan, was affected. She fairly purred along the road and, for once, required no driving.

We were in South Australia, bound for the still distant Macdonnell Ranges. At our right was a railway line with which we were running a parallel course. Soft green hills drooped down to us on either hand, magpies warbled, a great flight of Galahs rose for a few minutes from their feeding and floated like a rosy cloud a few feet above the ground—never was there a more peaceful scene.

The two artists, as they sat beside me, broke into snatches of song, and my thoughts ran back home. There, in that far-away suburb of Melbourne, my son and I would often turn on the wireless before breakfast to enjoy a laugh at the "crooners." Some of their songs had evidently revenged themselves by lingering in my consciousness, for now I found myself, without at first realizing the fact, singing:

La-a-azy Bones, lyin' in the shade,

How do you expect to get your corn-meal made?

But, while I had the tune, I found that I could not recall any more of the words. That made it suddenly desirable. I appealed to the others, but they declared they had never heard of the song. "Well, it goes like this" said I—and the next moment Henrietta rose up like a startled horse, took a desperate dive with two wheels in the air and crashed over on her side.