a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

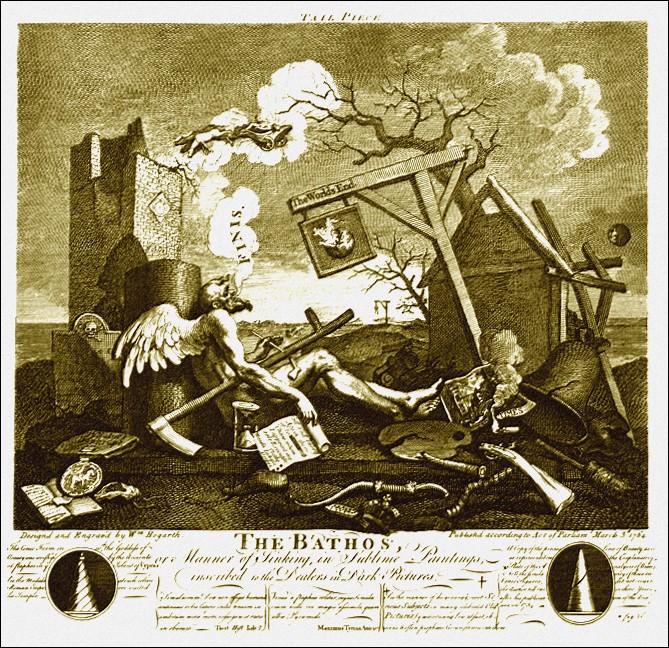

Title: William Hogarth: The Cockney's Mirror Author: Marjorie Bowen * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1402611h.html Language: English Date first posted: Sep 2014 Most recent update: Sep 2014 This eBook was produced by Colin Choat. Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

To A. L. L., Summer, 1936

The word cockney—cock-a-neg—cock's egg—first meant a fool, a grotesque, and, secondly, an inhabitant of London; it may, therefore, be fairly used to designate the world from which William Hogarth drew his material.

Terra-cotta Bust of Hogarth

Louis François Roubillac (1695-1762)

THIS volume is the result of years of study and of the author's admiration for the genius of William Hogarth; it is offered as a tribute to one of the greatest of English painters, in the hope that it may prove of some interest both to those who are well acquainted with this artist and his period and to those to whom nothing but his name and a few of his more famous works are familiar; if much attention is given to the background of the subject, it is because it is felt that a full understanding and appreciation of this artist's work cannot be arrived at without a fair knowledge of eighteenth-century London.

This study, for the sake of clarity and a continuous narrative, is divided into four parts; the first gives the background of William Hogarth's life and pictures, the second recounts his career and character and his attitude to his own genius, the third gives the stories, actors (real or imagined) of the principal pictures and prints, and the fourth describes and analyses the work from the point of view of aesthetics.

No attempt at a complete bibliography of the subject, nor a complete catalogue of William Hogarth's works, can be made in a work of this pretension; a short list of the principal authorities for the life is given and a short list of the more important paintings and engravings.

In the édition de luxe of William Hogarth by Austin Dobson, with a preface by Sir Walter Armstrong, London, 1902, is an exhaustive bibliography, together with two catalogues, one of paintings and one of prints, the whole comprising 128 pages; to this the reader in search of further information is referred.

Minute descriptions of all William Hogarth's satirical prints are to be found in: Catalogue of Prints and Drawings in British Museum, Division I. Political and Personal Satires, Vol. II, 1873—Vol. III (2 parts), 1879, London.

Where the pictures referred to are in private collections the present owners have been given as far as possible; it has not, however, been easy to trace all of these; in such cases the names given are those supplied in the lists given by Austin Dobson, either in his William Hogarth or in the article under that name in the Dict. Nat. Biography.

Grateful acknowledgements are made to the National Gallery, London; the Tate Gallery, London; the National Portrait Gallery, London; the National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh; the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin; the City of Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, Bristol; the Governors of the Foundling Hospital; to the Department of Prints and Drawings, British Museum; to J. Pierpoint Morgan, Esq., by whose courtesy The Lady's Last Stake is reproduced; to J. L. B. Williams, Esq.; to the Minneapolis Institution of Arts; to the Borough Council and Libraries Committee of Camberwell; the Curator of the South London Art Gallery; and to Mrs. Norah Richardson, Andover, Hants.

M. B.

16, QUEEN ANNE'S GATE

LONDON

December, 1935

THE SCENE

London 1697-1764

THE PAINTER

William Hogarth

THE CHARACTERS

Introduction

The Moralities

Satirical Genre Pictures

Tickets; Small Engravings; Symbolical Pictures

Satirical Portraits

Portraits

Genre Pictures

The Peep Show

THE WORKMANSHIP

'The Line of Beauty and of Grace'

AUTHOR'S NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON, in the early eighteenth century, comprised the ancient Roman capital, 'the city,' the old Borough of Southwark with a collegiate church, the City of Westminster with the seat of government and another great collegiate church, to which had once been attached a palace; it was surrounded by large, prosperous villages, interspersed with fields and seats of the nobility and gentry; some of these, such as Knightsbridge, Kensington, Paddington and Islington, were slowly being incorporated with the capital, while others, further afield, remained completely detached.

The straggling boundary of this London measured no more than a dozen miles, and the number of inhabitants was 'variously guessed at;' in 1739 the city proper was believed to contain 725,903 souls, some thirty years later a million people, it was supposed, inhabited London, Westminster and Southwark, if generous margins were allowed in the directions of Greenwich and Chelsea; in the absence, however, of any proper census of the population, no one could give with exactitude the number of Londoners; it was, at least, obvious that the city was grossly overcrowded and contained too large a proportion of the seven millions who—according to the same rough computation—inhabited the British Isles.

London was not only the home of the King, the seat of Parliament, a great Port, and one of the most considerable centres of the world's trade, it was the focus of the life of the country, the headquarters of art, of ambition, of learning, of enterprise, and also of luxury, folly, roguery and crime, the focus in a vivid and definite sense.

Bad roads and the extreme difficulty of transport, the dangers and discomforts of travel, isolated the capital in envied splendour and concentrated on the banks of the Thames between Chelsea and the Tower nearly all that was notable in every walk of life; there were few men who aspired to success who did not, sooner or later, make their way, often penniless and on foot, to London; there were few women, eager to exploit their charms, who did not try to find their market in London.

In the capital might be found whatever excitement, whatever novelty, whatever luxury the age afforded, and there might be caught those glimpses of the famous and the infamous, the royal Prince in his gilded coach, the criminal in the filthy pillory, that added zest and colour to life.

The country towns and villages were self-contained communities, where many lived and died contentedly; the manor houses sheltered generations of esquires, who never went further than the nearest country town; but peasants and country gentlemen alike thought with pride and awe of London, where, should they ever venture there, they were jeered at as boobies and Hodges by the smart Cockneys.

Some, however, came, and some stayed and contrived a livelihood out of the manifold activities of the capital.

Soon after King William had driven in state through packed streets of well-dressed people to give thanks for the Peace of Ryswyck in the huge, as yet unfinished, Cathedral of St. Paul's, one of these country adventurers, Richard Hogarth, a hedgerow schoolmaster from Westmorland, was living in Bartholomew's Close.

He had not met with much success in London; the classes he held in Ship Court, Old Bailey, were not sufficiently profitable even for a meagre livelihood, and the poor scholar eked out his means by writing Latin Dictionaries and Grammars and by correcting proof-sheets for the booksellers.

In his modest home was born, November 10th, 1697, his only son, William, named after the King; two daughters, also loyally named after the sister Queens, Mary and Ann, completed the little family that Mr. Hogarth found such difficulty in maintaining in decency. Not only was his classical learning an ill-paid commodity, but he found it far from easy to obtain his dues from the printers for whom he worked. He was, however, of robust, prudent, hard-working North-country yeoman-stock, and, despite all handicaps, he contrived to set up his daughters in a haberdasher's shop in Smithfield, and to apprentice his son, who had shown an inordinate liking for drawing, to Mr. Ellis Gamble, a silversmith, who resided at the Sign of the Golden Angel, Cranbourn Street, in the modish locality of Leicester Fields.

The boy had been taken from school because he covered his copy-books with ornaments, but he soon fretted at the drudgery of engraving heraldic designs on silver plate, and by the time he was twenty years old and out of his indentures he was looking about for some way of escape from a career as an engraver of silversmith's work.

He was full of zest for life and impatient of laborious toil, so set aside, as too difficult, his first plan of becoming a copper-plate engraver—a profession demanding the most delicate technical skill. Nor did the prospect of being a mere copyist appeal to him; he had already filled notebooks with jottings of odd characters and incidents that had taken his fancy and he believed that continued practice of this kind would give him all the proficiency that he required in his art, without the necessity of resorting to that long drudgery which was usually considered essential to success in any branch of graphic art.

In the spring of 1720 William Hogarth engraved two show-cards, one for himself, one for his sisters.

He was prepared to work for booksellers, printers, to produce book plates, shop cards, lottery and entertainment tickets, lids of snuff boxes—indeed to undertake any branch of hack copper-plate engraving whereby he could earn his living.

His own card was conventional in design, but competent in execution; two figures, two putti and two swags of fruit and flowers, all in the neo-classic style, enclosed the enscrolled name W. Hogarth; underneath, on a tablet surrounded by a heavy ornamentation, was the date, April, 1720.

The Misses Hogarth's pretensions were even more modest; they announced that they sold dimities, suits of fustian, ticken and holland, ready-made frocks, flannel waistcoats and 'drawers for Bluecoat boys.'

Mr. Richard Hogarth's children were thus provided for in the humblest walks of commerce; the son had early discovered from his father's example the financial uselessness of 'classical qualifications' and was resolved to make his way by more practical means, and there were no pretensions about the daughters, jolly, sensible girls, with round faces and dark eyes.

The family came, as far as can be known, of pure English stock, free from any admixture of Latin or Celt; they were good-humoured, pugnacious, honest, cheerful, full of common sense and resource, hard-working but fond of decent pleasures and simple fun; William's uncle, Thomas Hogarth (Hogart—Hog garth, swine herd), was a noted wit and comic poet in his native place, Troutbeck, near Windermere, which he never left; he produced 'a mass of poetry,' or rather satirical verse, most of which was rather too lively for general circulation.

William had this same gift of satiric comedy, a quick eye for the absurd, a quick pencil to note it down, a zest for 'shows' from Punch and Judy to a Drury-Lane tragedy, a gift for mimicry, an insatiable curiosity as to the scene in which he found himself.

He was a little, thick-set fellow, fond of fine clothes, clean, neat, plain, with a snub nose and commonplace features, inclined to strut, ready to quarrel, but just, affectionate, a friend to animals, scrupulous in 'paying his way,' industrious, despite a love of leisure and amusement, and fiercely patriotic.

His stock, like his qualities, was plebeian, but he was by no means boorish or rough; to native shrewdness he added Cockney sharpness, the polish the town quickly gives to country wits, and he had been at school long enough to save himself from the charge of illiteracy, while from his father he had received sufficient tincture of classical learning to enable him to understand and use a Latin tag at need, though his spelling of his own language always remained erratic.

Of general culture he had none and his reading had been limited to a few of the most easily accessible English books, such as Gulliver's Travels, Mother Bunch, Robinson Crusoe, the Arabian Nights, but he had been well-disciplined by a long apprenticeship to a difficult craft and his mind was alert and lively enough to find a continual zestful delight in the scene about him; this scene was London and it changed little during the sixty-seven years that William Hogarth lived amid it, nor did he, save for the briefest periods, ever leave the city where he was born.

While, then, the cheerful, pug-nosed ex-apprentice is setting up in business to earn an honest living as a modest copper-plate engraver, while his two young sisters are bustling among their lacets and tapes, their flannels and cambrics, let us, in the manner of the leisured 'ambulator' of the period, survey this scene; without some close acquaintance with it we shall not be able to understand either William Hogarth or his work.

To the middle of the eighteenth century all the great changes lay ahead; the commercial inventions that gave the country her sudden supremacy in European trade were as yet undreamt of; James Brindley had not cut his canals, or MacAdam laid down his roads; the mineral wealth of the country was unexploited, even two-thirds of all iron used was imported; charcoal was still used for smelting, the manufactured goods were made by hand in cottage homes, the high cost of transport—Manchester to Liverpool, forty shillings a ton for goods—kept enterprise and industry at a standstill; the use of water power covered the country with water-mills; the post was expensive and uncertain, it was a Government Service, remodelled in 1710; the charge was 3d. up to 80 miles, to Edinburgh or Dublin 6d.; the mail left the capital three times a week.

Large tracts of England, Wales and Scotland were wild, bleak, uncultivated, sparsely inhabited, difficult and dangerous to cross; a Cockney would have been as utterly lost on Yorkshire moors, Welsh hills or Scottish valleys as if he had been in Siberia or Tibet; such centres as the provincial gentry made for themselves, Chester, York, and Shrewsbury, were isolated from one another and from London; the country towns were self-supporting.

There was much unemployment, resulting in hordes of beggars; this evil arose from the gradual enclosure of the common lands by the landowners, who held all parliamentary power, from the conversion of arable land into pasturage for sheep, to supply the lucrative wool trade, and from the seizure of the Guild funds by Edward VI. Voteless, despoiled and plundered, the peasant's only hope was in the clumsy Poor Laws of Elizabeth and Charles II, which fed the destitute workers in sickness, old age or unemployment, on condition that their wages were fixed by the magistrates; as these were also their employers, the English labourer was in reality a slave, with no rights, freedom or privileges—a slave over whom there was no one to agitate or to sentimentalize.

The opulent seats of the nobility, who were enriched by the Church spoils seized at the Reformation and consolidated in their wealth and splendour by the Revolution of 1688, broke at intervals the waste lands or the cultivated fields and pastures and dominated with accepted arrogance the little town or the humble village.

Between these great gentry and the peasants was the sturdy yeoman-farmer class, which usually supplied the artizan and the craftsman, the carpenter, the saddler, the farrier, the sign and coach painter, the little shopkeeper of the provincial towns—sometimes an apothecary's apprentice or a lawyer's clerk.

This class was seldom submerged into the peasantry, but even more rarely scrambled into the gentry; the country was intensely class-conscious, and only in those circles in London where the intellectuals had formed their own societies was there any manner of freedom of thought, liberty of speech or sense of true values.

Arrogance on the part of the moneyed Whig gentry (aristocrats many of them were not), servility on the part of the middle-class traders, who lived on them, fear and ignorance on the part of the peasantry, divided the population into distinct strata; only great talent or peculiar force of character enabled a man to rise from the station in which he was born.

The practice of the fine arts was regarded as the province of those below gentility; the nobleman was the patron of the artist in the same sense as he was the patron of the jockey or the prize-fighter.

The Church was in a stagnant state; the particular brand of Protestantism that resulted from the Revolution of 1688 was interpreted as a cosy materialism by some, as black Puritanism by others; all spirituality had left a creed that was too comfortably endowed with worldly goods, all vigour had left a movement that had achieved its purpose; neither saints nor scholars adorned a Church where the fat posts went to the younger sons of wealthy houses, and where the routine work was done by despised, underpaid curates.

The Roman Catholics were oppressed by gross penal laws, and the abortive rebellion of 1715 had rendered them subject to still further distress and persecution.

Nor, in the early years of the eighteenth century, had those scenes of 'enthusiasm' in which the starved instincts of the people found vent, that mixture of inspiration and charlatanism, which was directed by men like Whitfield and the Wesleys, begun to disturb the hard materialism of the age under which lay the deep wells of sentimentality soon to be tapped by the genius of Samuel Richardson and the school of 'sensibility.'

The Government was settled; that is, some sort of a compromise had been made between what the majority wanted and what they could with safety obtain; a corrupt and incompetent oligarchy ruled a people who revelled in their traditional 'freedom.'

A German Prince had reluctantly accepted the Crown of Great Britain and been as reluctantly endured; expediency and a common dislike were all that linked the first two Georges and their people. The arrangement, however, under the adroit management of Sir Robert Walpole, first 'Prime Minister,' worked well enough to satisfy those with money and influence—those without either were not considered by anyone.

The Lords and Commons, sitting with ancient ceremonial at Westminster under the beams that had been shaped by Richard II's carpenters, and that had roofed over the trial of Charles I, gave the nation that air of British liberty and independence which was popularly supposed to be the envy and despair of foreigners. In reality Parliament represented only a portion of the people, the wealthy landowners, who were elected by one system of bribery and held their seats and gave their votes by another.

Sir Robert was a realist and, as such, was able to handle very efficiently the complex organization of corruption on which the country was run.

When William Hogarth first surveyed the English scene, there had been peace, since the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) had clipped off the grandiose ambitions of Louis XIV and the fallacious hopes of the House of Stuart, but Great Britain maintained an efficient fleet, largely manned by outcasts, pressed men and those too desperate and wretched to object to what was considered the hardest life in the world, and a small regular army recruited from peasants, officered by aristocrats, freshly laurell'd from Marlborough's bloody victories.

It was understood that, at a crisis, these native forces would be assisted by such mercenaries as might be hired from one of His Majesty's fellow-Electors, several of whom paid for their pleasures by trafficking in the bodies of their subjects.

With this rough machinery of government, functioning fairly well, with what was regarded as 'peace and prosperity' ruling over the land, the average Englishman enjoyed himself as well as a poor human being might in an imperfect world.

He could not miss what he had never known, and custom made him oblivious of the horrors that surrounded him; only the very observant, the very sensitive, the highly intelligent, noticed the cruelty, the filth, the disease, the gross vices, the repulsive coarseness that disfigured almost every aspect of life.

The brutal crimes resultant from an unpoliced society, the brutal punishments meted out by old laws no one troubled to reform, the grotesque medley of Puritanical restraints and cynic licence in manners and morals, did not disturb those who, born into this scene, tried to find their place in it, and who tried, perhaps, to fish up some prize from these filthy waters. Here and there some moralist stood aside, shocked and dismayed, here and there some saintly soul retired unspotted from the world, some philosophers sighed, some reformers wept, the gentle, the tenderhearted suffered and did what they could—but none of these was heeded by the greedy, harassed press intent on profit or pleasure or the mere necessaries of existence.

The beginnings of great movements for the betterment of humanity were daily broadening, but were as yet unnoticeable to the casual eye.

The age was grossly brutal; the amusements of the average male consisted in watching or taking part in a display of ferocity, prize-fighting, cock-fighting, bull-baiting, combats with quarterstaffs, cudgels or broadswords. The lower classes settled trivial disputes by hand-to-hand fights, which there were no police to interrupt, the upper classes went armed with swords and pistols, which they were always ready to use, either in self-defence or in 'affairs of honour.' Honour among the gentlefolk became fair play among their social inferiors; it represented one of the most respected virtues of the age. Punishments were shockingly severe, the state of the hospitals, prisons, orphanages and lunatic asylums, was appalling; all this was regarded callously by everyone save a few humanitarians, like Captain Coram.

Flogging was universal; children, criminals, vagabonds, apprentices, soldiers, sailors, were flogged 'within an inch of their lives' upon the least pretext; a man might be pressed to death for refusing to plead, a woman burnt alive for murder of husband or employer (treason), a child hanged for theft, a debtor left to starve in prison; drinking was incessant among all classes; the taxed spirits and wines, the native beers, were sold freely at all hours; it was said that in the lower streets of London taverns were in the ratio of one to three houses; much of the foreign stuff was smuggled; a large portion of the general public connived at this.

The gentlemen and their women-folk saw no offence to manners in constant drunkenness, the middle classes consumed the strong English ale without stint, the poorest could afford gin, cheap enough and powerful enough for a man to be able to lay himself out unconscious for the expenditure of twopence.

Crude rum from Jamaica was supplied to the Navy in generous quantities and helped to destroy the health and morale of the pressed, flogged sailor.

All foreigners were struck by the drunkenness and brutality of the English people, their ferocious prejudice against all strangers, their lack of refinement. In the practice of hard drinking the English had no rivals, save possibly among the habitués of some of the small German Courts, and the ruffianly behaviour permitted in the London streets had no parallel in any other capital.

It was no individual person's fault that these streets were cobbled, with gutters full of filth in the centre, that springless carts and carriages jolted over them with harsh rattlings, that wandering hawkers kept up a continuous shouting, that fights were frequent, that a shower of rain sent spouts of water off the pipeless roofs, that unrepaired pavements caused puddles too wide to jump across, that at night the few oil lamps cast only sufficient light to throw misleading shadows; but the brutal licence permitted to the vagabond and the ruffian was a bitter commentary on the temper of the times.

London was not safe after dark; not only did the sneak thief swarm, not only might the link boy hired to light the way be an accomplice of a footpad, but parties of young men of the better classes roamed about, bringing into contempt the ill-paid watchmen who alone represented law and order by their unavenged assaults upon them and indulging in violent pastimes that included savage attacks upon life and property.

Only those who could afford armed servants could venture abroad after dark, when the streets were infested with young rakes ready to beat a man to death, to roll a woman downhill in a barrel, to use sword, pistol or knife against the harmless and the defenceless passer-by, to smash windows and damage property by way of a frolic.

Coffee-houses were the scenes of more civilized forms of masculine amusement; these were used by various classes and served as clubs as well as eating-houses; here politics were discussed and the meagre newspapers of the day read; these last often contained offers of rewards for escaped negro slaves with collars on their necks or notices of slaves for sale.

Among the pleasanter diversions of the people were cricket and bowls, played on inn greens and village commons, football played in the streets, skating or sliding on ice, foot races and horse races.

Hunting, shooting and fowling were the luxuries of the well-to-do; all classes enjoyed bear-baiting, cock-fighting and such spectacles as 'a mad bull dressed up with fireworks all over him,' bulls with cats tied to their tails, wild bears and 'he-tigers;' they enjoyed the sight of all these being 'baited to death.'

All the education the poorest classes could hope for was from the charity schools, which could deal only with a small proportion of the destitute, the lower-middle classes had to rely on the dame-school or the hedgerow pedagogue; for those who could afford a little more there were grammar schools, private schools, the public schools, Westminster, Winchester, Harrow, St. Paul's, Eton, the City schools; for the wealthy the private tutor, the Continental tour, the University.

After reading, writing, elementary arithmetic, nothing was taught save the classics; to be a good Latinist was to be considered at the height of learning and culture.

Penmanship was highly valued and often carried to the perfection of a fine art.

The Universities of Oxford and Cambridge were in a state of mental and moral stagnation; the two towns were small copies of London; there were sports, fights, drunken orgies, dirt, brawls, a little work, a good deal of idleness; in many respects the University towns were worse than the capital, as they contained so many lawless young men with little to do, money at their disposal and high opinions of themselves as the future rulers and judges of the land.

There is little to be said about the position of women; the laws largely delivered them and their property to the men, who on the whole did not abuse their power; the Englishman's love of home and of family life persisted through all the distractions of the age.

The aristocracy and the moneyed classes might drink, gamble and riot away health and peace of mind, but the humbler citizen could usually show a pleasant interior to his house.

The home, when domestic necessaries were hand-made and most were made within the household, provided sufficient interests for most of the women, who had only received the scantiest amount of 'book learning,' and who were usually satisfied with the formula of a religion that, to simple minds, seemed to supply all spiritual needs.

For the woman who had no taste for domesticity or piety, there was little scope; a few daring bas bleus protected by birth and means, a few cultured great ladies with position and leisure, might venture to be original in their mode of life, to express individuality in word and action, but for the rest a woman's safety and happiness depended entirely upon her compliance with convention.

Not only an illicit love affair, but the suggestion of one did literally 'ruin' a woman.

Since, even if she owned property, some male never failed to get it by marriage, and it was impossible for her to earn more than the meanest sums at the meanest labours, a woman who broke with her family soon found herself in the position of an outcast and a criminal; the 'dishonoured' woman was treated with a more brutal contempt than that meted out to the vilest and most wretched of the opposite sex.

It was a paradox in the manners of the age that the man who made the seduction of innocent young women one of his sports was excused, no matter what trickery he employed to gain his end, while his victim, however deceived, trapped or forced, was considered forever 'lost;' her only escape from sinking to the utmost degradation was, as Oliver Goldsmith observed, 'to die.'

On the other hand, there was no lack of willing damsels to swell the ranks of 'the votaries of pleasure' and to risk Bridewell, the cart, the lazar-house, for the sake of ease and luxury; the vast underworld of London was peopled with women as clever, as vile, as cruel, as coarse as the men whom they served, and the horribly frequent spectacle of the depths to which women could sink no doubt helped to enforce the severe line of demarcation between the protected, respected woman and her 'fallen' sister.

The morality of the women of the upper classes was, as always, a thing apart; they were expected only to keep up appearances; no great courtezans set the tone of the Court or society, no actress or singer of genius broke all conventions and was a focus of brilliant manners; there were no salons, but many of the aristocratic ladies were cynically Unmoral.

Among the middle classes the female standard was high, but far too self-consciously 'virtuous;' the emphasis given to the value of chastity and its attendant graces, decorum and prudery, put all other qualities in the shade; the 'good' woman was the constant wife or the spotless spinster; no variation was allowed on this theme; the age that romanticized and sentimentalized the 'erring' woman had not arrived, there was no social reformer to pity, no poet to celebrate the woes of the Jennys and Molls who traipsed the London streets and perished in Bridewell or the hospital.

If prostitutes had never been in greater numbers or more openly flaunting, never had they been treated with more harshness; when one false step sent a woman down to the gutter and the jail, female character became, on one hand, timorously rigid and hypocritical, on the other, cynically hardened and debased.

The dress of both sexes was highly fantastic; the era of commonsense, of democracy, had not dawned; the cavalier costume that had triumphed at the Restoration had evolved into very elaborate, costly fashions, which included the use of expensive materials, broadcloth, velvet, satin brocade, fine linen, and such adornments as elaborate hand-embroidery, buttons, buckles and clasps of precious metals and stones. Many of these were foreign, taxed, and smuggled. The main characteristics of the period were, however, the powdered hair or wig, and the hoop or farthingale. During the period of which we treat these had not become so ugly and grotesque as they did during the last quarter of the century; indeed, the dress of the upper classes was rich and becoming, the male fashions being in particular attractive, elegant and graceful.

As all these clothes were hand-cut, hand-made and hand-embroidered, lace and embroidery being the result of patient stitching, and ornaments the result of skilled individual craftsmanship, the complete costume had great beauty and distinction; even when old and damaged, the hand-woven, hand-dyed stuff was pleasing in its faded shades. No one was, in the modern sense, cheaply dressed, since it was impossible to obtain the 'imitation,' 'slop' article; even the humblest garment was the result of someone's personal labour, since mass production was unknown.

The lower classes dressed in a modification of the Puritan style, plain, warm, sensible garments, with short, unpowdered hair; this sharp difference in attire helped to distinguish most clearly one class from another; clergy, lawyers, doctors had their peculiar, unmistakable garb, while officers of both services wore their elaborate uniforms on all occasions.

The manner in which the people lived was on the same lines as their clothes, rich and fantastic, elegant and graceful, where there was money, useful and plain where there was little, squalid where there was none.

Certain inconveniences were suffered by all classes alike; the houses were as dark, as shut in as the streets; anyone who wanted air and space had to go into the country. Not only was daylight recklessly excluded, but artificial illumination was poor. Wax candles, oil-lamps for the rich, mutton candles for the thrifty, rush-lights for the poor, all gave a beautiful light from a pictorial point of view, but these lovely, becoming rays, these entrancing shadows, were inconvenient, tiresome, labour-making and dangerous. In the winter, and after the sun had set, life moved in a twilit atmosphere, deepened in London by the constant pall of smoke from the coal fires and the fogs of the river valley.

The rooms were low, draughty; the furniture stiff, uncomfortable; carpets and tapestries were articles of luxury, as were china and silver; pewter and wood sufficed children, servants, and many modest households.

The labourers lived in hovels of mud, with unglazed windows rudely shuttered at night; they slept in lofts reached by ladders; in London entire districts of slums rotted amid filth and decay; sanitation of the crudest rendered the palace inconvenient and the mean dwelling dangerous; though some care was taken of personal cleanliness, general cleanliness in street, public place, hospital, prison, barracks or asylum, was utterly neglected.

Personal service was cheap, even if notably inefficient, and the wealthy obtained ease and luxury by means of a large number of servants under the direction of a majordomo or steward; these had a bad name for dishonesty, idleness and insolence.

A galaxy of brilliant men had adorned the reign of Anne, and in that of George I literature flourished with many famous names; native pictorial art was ignored, while huge quantities of Italian pictures and statues were imported to adorn the mansions of the wealthy; the school of English portraiture was in its infancy, the school of English landscape-painting was yet to be; native music had been silent, since Purcell died, and a swarm of foreign musicians and singers fattened on the fees of the English dilettanti. Drama was at a low ebb; turgid tragedies, mutilated versions of Shakespeare's plays, licentious comedies, were presented at the famous London theatres; among the actors were men of high character and talent, who were respected and courted, but David Garrick was the first to raise his profession above reproach, and charming, clever, witty as the actresses might be, none of them was admitted to the station of a gentlewoman nor escaped sneers, unless she married into the peerage, which unprecedented success was achieved by Lavinia Fenton.

A great excitement of daily life was the lottery; there were several of these and the most important (authorized 1709) was run by the State; the prizes offered by this often amounted to nearly forty thousand pounds.

Gambling of one kind or another was universal and unrestricted; it filled all ranks of life with black uncertainty; the possibility of ruin, sudden and unexpected, was in every home, cards led to cheating, quarrelling, duelling, murder, suicide.

This last crime rose to appalling frequency towards the middle of the century; neither the ignominy of burial with stake through the breast on the common highway, nor fear of the hell threatened by the Church, could prevent those excited by drink, ruined by vice, exhausted by self-indulgence, tortured by disease and the horrors about them, from leaving the terrible bewilderment of life by means of the rope, the knife or the river.

During the period that we shall consider—1720-1764—there was no great outward change in England, though there were from year to year the usual variations in taste, fashion and fancy, and though the period covers a rebellion, two wars, the rise of the English school of portraiture and the rule of three Kings with their changes of ministers; all these ministers were, however, Whig, a fact which gave a uniform tone to public life.

When William Hogarth died in 1764, the industrial revolution, which had been so long gathering force unseen, was beginning to advance quickly; within a few years the inventions of Arkwright, Hargreaves and Watt were to mark the beginnings of a great upheaval in the national life, and, across the Channel, the philosophes were beginning those speculations that preluded and influenced the gigantic changes in the history of mankind known as the French Revolution. But during the life of Hogarth such things were, undreamt of; the ideals of the democrats of 1789 were as little suspected as the invention of gas lighting or of the steam engine.

This being our period, and this a rough sketch of the general conditions of the country, let us return to London and consider it as it was when William Hogarth set up in business there.

Leicester Fields and Covent Garden formed the centre of London's intellectual life, so that it was in the very heart of the artistic metropolis that the young engraver served his apprenticeship to Mr. Ellis Gamble.

Setting out from this favoured district, our 'ambulator' could proceed eastward to the City proper, by way of Lincoln's Inn and Fleet Street; beyond the confines of Roman London and the Tower a long row of houses lined the river bank to Wapping, Rotherhithe and the Docks, with Bow inhabited by porcelain-workers and scarlet-dyers. Northwards from Leicester Fields was the fashionable district of Soho, St. Giles's and Bloomsbury, which ended abruptly in the three-sided Queen Square, left open on the fourth side for the sake of the rustic view towards the heights of Hampstead and Highgate.

Gray's Inn, Smithfield, and as far as Moorfields, were a densely populated district, west from Covent Garden were Piccadilly, the smart mansions of Saint James's Square and the valley where the Tyburn brook flowed from the village of Marylebone to the Thames at Westminster, which city was reached southwards from Leicester Fields by way of Charing Cross and Whitehall. Westminster straggled out in riverside houses, flanked by marshy fields, nearly as far as the village of Chelsea.

On the Surrey side of the Thames was the city of Southwark, which spread into a rough, unpoliced district—the remains of old Alsatia or thieves' Paradise (which lost the rights of sanctuary in the reign of William III)—and stretched inland to Saint George's Fields, across Lambeth Marsh, toward Rotherhithe in one direction, toward the market-gardens of Battersea, where Lord Bolingbroke lived in retirement, in the other.

If we make, with our 'ambulator,' who is a gentleman of leisure, a close inspection of these districts, we shall have a clear idea of the scenes amid which William Hogarth lived for nearly seventy years and which formed the material of his art.

A stranger, taking the 'ambulator' for his guide, would, first, have been told of the great size, wealth, and splendour of the City; it had two-thirds of the whole trade in England and one-seventh of the people, a Cathedral, two collegiate churches, seventy-four other churches, nearly as many meeting-houses for Dissenters, three choirs of music, three synagogues, seven Popish chapels, thirteen hospitals, four pest-houses, three colleges, one hundred and thirty-one charity schools, the finest of which in a circuit of ten miles was the Foundling Hospital in Lamb's Conduit Street, fifteen meat markets, two cattle markets, twenty-five other markets, fifteen Inns of Court, and twenty-seven prisons.

Besides these signs of wealth and splendour there were other evidences of prosperity, in the form of over twenty squares, three stately bridges, London, Westminster, and Blackfriars, a Guildhall, an Exchange, a customs-house, two Bishop's palaces (London and Ely), and three royal palaces, St. James's, Somerset House, and Whitehall, besides the noble ruins of the Savoy.

Among the conveniences of the capital were the one thousand hackney coaches plying for hire, the sedan-chairs, which were also easily obtained, and the number of expert watermen with their wherries ready to convey the citizen or the visitor up or down the river, which was the High Street of the capital.

The seven gates that still stood were demolished in 1760, with the exception of Newgate, and a handsome arch had, since 1670, marked the boundaries of the City by the buildings and gardens of the Temple.

There were three artillery grounds; the artillery itself was kept at the Tower, where were also the armoury, the regalia, the Mint, and, a cause of great pride to Londoners, the menagerie of strange beasts and birds.

Most of the notable buildings of the City were new at this date, the Mansion House, the General Post Office, the Mad House in Moorfields, new London Bridge with the handsome Gate House, the Bank of England; the Exchange dated from 1669 and Saint Paul's, 'the finest Protestant church in the world,' had not been long completed.

Other much admired buildings 'in the modest taste' were Doctors' Commons, Surgeons' Hall in the Old Bailey, and Physicians' College in Warwick Lane.

Southwark contained six parishes and was 'inferior to few cities in England;' much of its ground was, however, covered with warehouses and tenements; there were two famous hospitals, St. Thomas's, and that endowed by the bookseller Thomas Guy, who made a fortune out of Bibles and by speculating in South Sea stock.

Southwark felt great pride also in a new Magdalen House, and an obelisk in St. George's Fields, which was nobly surrounded with lamps.

Westminster boasted the Abbey, the School, the Hall 'without one pillar to support it'—and the new Buckingham House, as well as the two ancient palaces and St. James's Park. Somerset House, built by Inigo Jones, still stood, and was used for Government offices; the noble bridge was begun in 1738 and completed in 1750; it had several watch-houses, twelve watchmen, and thirty-two lamps, each with three burners.

Several fine churches were particularly pointed out to the attention of the stranger, St. Margaret's, St. Martin's-in-the-Fields, St. Paul's, Covent Garden, St. Mary's-le-Strand, Saint Giles's, St. George's, Hanover Square, but the greatest 'curiosity' was the British Museum, lodged in Montague House, Bloomsbury, which was to serve as a library for studious gentlemen and as a gallery for objets d'art and the Cotton and Harleian MSS., together with the Sloane collection and the libraries of the Kings of England from Henry VII.

There were, also, some antiquities and a set of paintings by Van Dyck; the public were admitted in batches on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays during the summer months, fifteen people at nine, fifteen more at eleven, and another fifteen at one o'clock.

The villages surrounding London were of great interest to both the Cockney and the stranger and the objects of frequent jaunts and excursions; they were as old as London itself and self-contained, with church, usually rebuilt in the classic style, green, inn, and in many cases with a manor, a charity school or alms-house.

Chelsea was famous for the Hospital for Old Soldiers, the Physic Garden with two thousand different plants, Saltero's coffee-house, and the seat of Sir Robert Walpole, which contained a collection of pictures supposed to be the finest in the country.

Hammersmith was notable for its handsome estates, Hampstead was a favourite district for retired merchants and boasted an assembly room, a meeting-house, and a church; Kensington consisted of 'genteel houses,' several boarding-schools, many inns, and the palace built by William III; the Gardens, with the Serpentine lake, were much admired and were open to the public when the Court was not in residence, as were the State apartments with the collection of 'sacred and profane' pictures.

On the other side of this royal Park was the pleasant village of Paddington, surrounded by fields—the residences here also were 'genteel.'

For longer, more ambitious excursions, better made by water, were Kew and Richmond. The former was rendered very attractive by the royal gardens gradually laid out during many years by Sir William Chambers, the King's architect. Most of the marvels, however, with which he adorned the gardens were erected only towards the close of our period, 1758-1761.

Round this part of the river in Chiswick—Mortlake, Brentford, and Richmond—stood, amid the scenes of pastoral loveliness, the elegant houses of the wealthy and fastidious.

In Chiswick were two manors, a charity school, and the luxurious seats of several noblemen, the most splendid of which was the Palladian mansion of the Earl of Burlington, which possessed beautiful grounds and a costly collection of pictures.

Brentford, on the great thoroughfare to the West, was a busy market town, and many charming villas stood on the fine rising banks opposite Kew.

Richmond was reckoned 'the finest village in the British Dominions and the English Frascati'. The old palace of Sheen had gone, but on the site was a plain mansion built by the Duke of Ormond on land given him by William III; on the Duke's attainder this had escheated to the Crown. During the mid-eighteenth century this modest palace was beautified by additions of dairies, canals, temples, groves of trees, altars, pavilions and summerhouses in the artificial taste of the time.

There was a labyrinth, a Merlin's cave, a hermitage or Gothic ruin; all this was added under the direction of the energetic Queen of George II, Caroline of Anspach.

About the palace were cornfields, a heath of broom and furze, which sheltered hares and pheasants, pasture lands and forest walks.

Along the river front were mansions occupied by the Princes and Princesses, and round the spacious Green were elegant residences of 'persons of distinction,' among whom were Sir Charles Hedges, who had a magnificent villa boasting 'the longest and highest hedge of holly that ever was seen,' grottos, vistas, a decoy and 'a stone-house,' where the first English pineapple grew, and Mr. Heidegger, Master of the Ceremonies to George II and the ugliest man in the Kingdom.

Beyond the Duke of Cumberland's house was the Deer Park, and on the other side of the Green the village 'ran up a hill' to the celebrated view, 'the most rich, polished, luxuriant that any country can produce.' It was considered remarkable that the river should be tidal at Richmond, sixty miles from the sea, and it was declared that this was a greater distance than the tide was carried up any other river.

Sir Robert Walpole had another fine seat in the great Park, the finest, save Windsor, round London, and across the river was the bridge, not replaced by the admired structure in classic taste until the last quarter of the century.

Further on were other fine buildings, Ham House, belonging to the Earl of Dysart, and Marble Hill, belonging to the Earl of Buckingham.

Amid these 'delightful seats,' built in a classic style that contrasted piquantly with the delicate landscapes, were the modest but cosy retreats of the intellectuals, who, like Mr. Pope at Twickenham, lived in a rural retreat but yet under the shadow of the noble patron.

It is well to complete our brief survey of eighteenth-century London with some account of those two great places of entertainment, Vauxhall and Ranelagh, which for many years were of such importance in the social life of the capital and supposed to be responsible for much of its folly and immorality.

Ranelagh was situated at Chelsea, convenient for water travel and open from April to July; for a shilling it was possible to reach the pleasure gardens by hackney-coach from Hyde Park Corner, along a lamp-lit road.

The price of admission was half a crown, and the company who paid to enter were 'genteel and polite,' while the entertainments were of a very refined order—at least, according to the claims of the proprietors.

On the death of the Earl of Ranelagh, his mansion and park had been purchased by a company which converted them into a pleasure resort; this work was completely finished by 1740.

The main attraction was the Rotunda, built of wood in the interests of economy; this building was of the Doric order, and its handsome porticoes, galleries, arcades, fluted pillars with plaster of Paris termini were much admired, but the greatest marvel was the fireplace structure that rendered the whole building very warm and comfortable and could 'not smoke or become offensive;' it had four 'faces,' stood in the centre of the hall and was supported by eight pieces of cannon filled with lead. About seven in the evening a number of candles in glass lamps were lit in this Rotunda and a concert began; there was a large orchestra and famous singers were employed; fifty-two boxes, including one for the King, accommodated the audience; red baize benches were provided for those who could not crowd into these loges, which were adorned with droll paintings and opened at the back on to the gardens.

On the plaster of Paris floor was a mat 'to prevent people from catching cold,' the ceiling was painted olive colour with a rainbow across it, and 'no words could express the grandeur of the sight' when the twenty chandeliers, each containing thirteen candles, were lit.

Breakfasts were at first taken here, but later forbidden by Act of Parliament; masquerades were, however, permitted, and these were the scenes of much licence and intrigue, since everyone, masked or disguised, roamed about freely bent on pleasure; so notorious became these carnivals that they also were in time suppressed.

The gardens were lit by lamps, contained well-laid-out walks and convenient little temples and pavilions; there was a canal, flower-parterres, grottos, and a pipe that drained all 'foul waters' into the Thames.

These gardens might be visited during the day at the cost of one shilling, but 'for reasons too obvious to be pointed out' no intoxicating liquors were sold at Ranelagh at any time; it is not clear whether they might be brought in or not.

A large amphitheatre had been erected for servants to wait in, so that they might be unseen, yet handy when required; in short, nothing had been forgotten that might induce the comfort and enjoyment of the visitors to Ranelagh.

Vauxhall was an older place of entertainment than Ranelagh; as early as the reign of Charles II, Sir Samuel Moreland had, on this spot (the south side of the Thames, in Lambeth), a curious hall lined with looking-glass, having on the roof a Punchinello holding a dial and surrounded by fountains, which was much visited by strangers.

This property was bought by a Mr. Jonathan Tyers in 1730, and he proceeded to advertise it as a ridotto al fresco.

This was so successful a venture that the gardens were increased in size and beauty and considerable attractions offered to the public, who could easily reach Vauxhall by water. The season was from May to August, the cost of admission one shilling. Roubiliac's statue of Handel adorned one of the neat gravel-walks, there was a fine organ in the concert hall, and for one guinea a silver ticket entitling the bearer to admission to the season's music might be obtained.

In fine weather the orchestra was placed in 'an edifice of Gothic construction, of wood and plaster, richly carved and painted white and bloom colour;' this was set in a grove of trees said to be more than a century old; these outdoor concerts began at eight and, by law, ended at eleven.

A more vulgar but equally popular amusement was known as the Day-Scene or Tin Cascade.

A painting of an extensive landscape was exposed in a large timber-room and at nine o'clock in the evening a bell was rung, upon which the curious of both sexes 'flocked in a rapid crowd' to witness an 'eye trap.'

This was a moving picture; a landscape in perspective with a mill and a miller's house was displayed and the water was seen flowing down a slope, turning the wheel of the mill, 'rising in foam at the bottom and gliding away.' A realistic sound of falling water helped the trick, which was shown for about a quarter of an hour.

The concerts usually ended with glees or catches, in which the audiences joined; refreshments were served at little tables under the trees and royalty was sheltered by a pavilion, lit by wax lights and adorned with paintings by 'the ingenious Mr. Hayman;' the subjects of these were the historical plays of Shakespeare.

Two thousand glass lamps lit the groves and walks, and bad weather was provided against by a Rotunda, a choice mixture of Gothic and Ionic styles, which was lined with mirrors, lit by chandeliers and adorned with 'bustos of eminent persons.'

The acoustics of this building, nicknamed 'the umbrella,' were excellent; it had fourteen sash-windows and a number of statues—a complete Olympus in plaster of Paris.

The outdoor walks were paved with clinkers brought specially from Holland, so that no 'gravel nor sand should stick to the feet of the company;' these paths led round several alcoves decorated with paintings, some, later in the century, from designs by Hogarth himself (four afterwards painted by himself as the Four Times of Day), others from sketches by the popular and energetic Mr. Hayman.

Some of the subjects were ordinary enough, others were lively and topical.

The New River Head was after Hogarth's design (Evening), probably painted by Hayman; it was described as:

'A family going a walking, a cow a milking, and the horns fixed archly over the husband's head.'

Two others depicted scenes from Pamela, there was another from The Merry Wives of Windsor, one from Molière's Le Médecin malgré lui (The Mock Doctor), and a brisk study entitled 'A Sea Engagement between the Spaniard and the Moars' [sic] (Battle of Lepants) [sic]; others showed fashionable pastimes, leap-frog, blindman's buff, sliding on the ice, quadrille, kite flying, card houses, tea-drinking, shuttlecock, hunting the whistle, cricket, see-saws, hot cockles, bob-cherry, and playing on bagpipes and hautboys.

Sometimes these genre pictures were given a peculiar point, as in those entitled:

One piece had the charming title:

A Northern Chief with his Princess and her favourite Swan, placed in a sledge and drawn on the Ice by a Horse.

There was also Fairies Dancing on the Green by Moonlight, and patriotic pieces were added from time to time—Black-eyed Susan taking Leave of Sweet William on board one of Fleet in the Downs, in 1740 The Taking of Porto Bello, in 1742 The Capture of the San Josef by Captain Tucker in The Fowey, and in 1761 The Taking of Montreal by General Amherst.

There were several curiosities in the grounds, where nightingales and thrushes sang in the venerable trees, a hermit's cell lined with cockle-shells, the statue of Handel (caricatured elsewhere as a pig, 'the tomb of meat and drink') as Orpheus, and some much-admired Gothic ruins of painted canvas stretched over wooden frames; some of the vistas were closed by large cloths, on which were painted scenes that were thought 'to improve on nature.'

There were also musical bushes, which, by some mechanical contrivance, emitted melodious sounds—these were, unfortunately, soon ruined by the damp. There was a seated statue of Milton, who appeared to be listening to this 'vocal forest;' it was cast in lead and placed on an eminence.

Obelisks, ha-has, Chinese gardens, wildernesses, singing Savoyards in native costume, added to the delights of Vauxhall, among which were also reckoned 'our lovely countrywomen who visit these blissful bowers.'

Refreshments were not expensive considering the free attractions the visitor enjoyed, and in contrast to Ranelagh wine could be bought; the most costly item that could be purchased was Champagne at 10s. 6d. a bottle, Burgundy was next at 7s. 6d., Claret and Old Hock were 6s. each, Madeira 5s., and the cheapest wine was Red Port or Lisbon at 2s. 6d. a bottle. Rhenish was 3s. and Sherry 3s. 6d.; these wines were all drunk sweetened, and enough sugar to flavour a bottle might be purchased for 6d.

For 1s. you might have a bottle of cyder, or two pounds of ice, or a plate of ham, or collared beef, or a potted pigeon, or a tart, or a plate of olives, or a plate of anchovies; a chicken was 3s., but for 6d. there was a choice of a quart mug of beer, a lettuce, a cucumber, or a jelly.

Wax lights ran up the bill Is. 4d. and a lemon was not to be had for less than 3d., custards and cheese-cakes were 4d. each, but a 'heart' cake or a Shrewsbury cake was only half that price.

The only items that cost 1d. were slices of bread or biscuits; portions of cheese or butter cost 2d. each.

About a thousand people enjoyed this sumptuous pleasure place every night, but it could at a pinch provide food and amusement for seven thousand, as was proved when there was a regatta on the Thames or a visit from a royal personage.

This, in rough outline, was the world over which the first two Georges reigned, where the Wesleys and George Whitfield preached, where Lovelace pursued Clarissa, where Mr. B. pursued Pamela, where that damsel's mock brother, Joseph Andrews, came to seek his fortune, where William Collins wrote his odes and Swift his pamphlets, where Sterne (writing in 1740) first used the word 'sentimental,' where Gray composed his elegy, where Horace Walpole built the absurd Strawberry Hill and wrote some of the wisest, wittiest commentaries that have ever been made on the affairs of men. This London raved over the sublime nonsense of Ossian and enjoyed the neat couplets of Alexander Pope. From this London General Wolfe went to capture Quebec and to this London came Samuel Johnson and his pupil, David Garrick; here perished the grotesque Richard Savage and here Margaret Woffington delighted the town here the fashionable world languished and raved over the singing of Italian eunuchs and went into raptures over the painting on a porcelain tea-cup, and here the people rushed to pelt to death a wretch fastened in the pillory for a minor offence or to see a woman hanged for picking pockets.

It was the world of Gay's Beggars' Opera, of the Lorenzo who poured out his Night Thoughts to the profit of Dr. Edward Young, the world to which Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough came to make their fortunes.

For most of its inhabitants it was a sour, dreary world, hypocritical, brutal, becoming, as the century advanced, more and more laced with 'sensibility' and 'sentiment,' which took the place of nobility, heroism, serenity and true courage; in the same manner, 'enthusiasm,' often scarcely distinguishable from hysteria, took the place of genuine religious feeling.

It was a bitter age, coarse, heartless, tinged with despair; science was asleep, scepticism, bigotry and superstition went side by side, pleasures were mostly lewd and vulgar, idealism was almost eclipsed by materialism—only in music and (occasionally) in verse did the human spirit utter pure and lofty thoughts.

Taste was at a low ebb and expressed itself in a profusion of gaudy, senseless ornament; the filth amid which most men lived tainted their outlook, nothing pleased so much as the bawdy joke, the incessant turning over of the bestial and the indecent aspects of life.

Noblemen affected fine manners and a patronage of the arts, but the former were skin-deep and the latter founded on ignorance; nowhere was that truly civilized elegance which had flourished in Italy during the Renaissance, and which was being sedulously cultivated in eighteenth-century France—a country that the English nobleman unskilfully aped and at which the English commoner unskilfully mocked.

Such as this world was, it offered rich and varied material to a satirist, to a student of manners, to one sensible of the violent, horrible and moving drama of humanity.

WHEN, in 1720, William Hogarth set up in business for himself as an engraver, he had great ambitions to succeed as a painter; he was also under the necessity of earning his living and so was forced, as most men of talent and genius have been forced, to seek to combine the exercise of his gifts with the earning of an income.

He knew his way about his world; he had early made acquaintance with some of the lively and interesting professional people who lived in the heart of London and he had visited the studios of successful painters; those embryo 'academies' where students pooled their resources in order to pay for a room and a model were not yet in existence, but the workshop of a painter who took pupils was a good drawing school; there was some showy stuff to be seen in London, notably the grand staircase painted by Verrio for the Bluecoat School. The eager young man may have frequented the studio of Sir Godfrey Kneller, or received some instructions from such painters as Francis Hoffman or Samuel Moore.

William Hogarth had also studied such smaller works of art as came his way and been in particular impressed by the engravings of the Lorraine master, Jacques Callot (1592-1635); drudgery was hateful to him, and in his itch to be at the business of creative work he could hardly be brought to believe that the long, weary toil at technique that was considered needful to excellence in painting was really necessary.

So, shirking systematic study, he continued to fill sketch books with drawings of the people whom he saw round him and to store his mind with the genre pictures that the life of the great city was always affording.

He was sufficiently accomplished as an engraver to be able to obtain constant employment; in the days of his better fortunes he often used to relate with zest:

'I remember the time when I have gone moping into the City with scarce a shilling in my pocket; but having received ten guineas there for a plate, returned home, put on my sword and bag wig, and sallied out again with the confidence of a man who has ten thousand pounds in his pocket.'

The best of these engravings on plate that have survived is that of the arms of the Duchess of Kendal.

He had a more interesting occupation than that of emblazoning heraldry on silver vessels; though his technique as a copperplate engraver was not good, it was considered adequate for the rough book-illustrations then used—he found, therefore, he could get employment from the booksellers; some of his plates were from his own designs, some from those of hack draughtsmen; they had little to distinguish them from any other production of this type and consisted partly of ornament and partly of scenes from the work in hand.

In 1723 appeared The Travels of Aubrey de la Mottraye, the next year, a version of The Golden Ass (The New Metamorphosis), in 1726, headpieces to Roman Military Punishments, and in 1726, Hudibras; these were all illustrated by William Hogarth.

His dealings with that ill-reputed tribe, the booksellers, were no more satisfactory than had been his father's, and, after quarrelling with them, the artist published at his own expense in 1726 some plates illustrating Hudibras. He also issued in 1724 a plate variously entitled Burlington Gate, The Taste of the Town and Small Masquerade Ticket, and also a satire on William Kent's unhappy altar-piece for St. Clement Danes Church.

These were not his first essays in satire; in 1721 he had engraved for the booksellers Who'll Ride? (South Sea Bubble) and The Lottery—these were clumsy, elaborate squibs in the style of Jacques Callot and have an entirely local and topical interest. They showed, however, considerable talent and much technical skill, and it is difficult to believe that they come from the same hand as that which touched in the little plate The Rape of the Lock (prior to 1720) with its pretty, insipid little figures.

Hogarth found that his old enemies, the booksellers, pirated his plates, as there was no law of copyright, so that, work as hard as he would: 'until I was near thirty,' he wrote afterwards, 'I could do little more than maintain myself; but even then I was a punctual paymaster.'

The desire to paint still animated the young engraver; the grand paintings in Greenwich Hospital and in Saint Paul's Cathedral 'ran in his head,' and when the painter of them, Sir James Thornhill, opened a little Academy for study at the back of his house in Covent Garden, the eager tiro seized the opportunity of making the acquaintance of the master.

Thornhill, who came of good family and had been knighted in 1720, was a pupil of Thomas Highmore, Serjeant-Painter to William III and uncle of the well-known portraitist, Joseph Highmore. Thornhill was acknowledged head in England of that 'grand' or 'historical' school of painting, which, founded on bad Italian and Flemish models, was then regarded with awe and reverence; he had been employed by Queen Anne to complete the schemes of decoration begun under Charles II, James II and William III by Antonio Verrio and his assistant, Louis Laguerre, whose 'sprawling' figures provoked the mockery of Pope.

There was, in truth, nothing but the size that was 'grand' about this school of painting, the matter was nearly always some stale and usually misunderstood classic subject, the models vulgar, the grouping coarse, the colouring harsh and the execution slovenly, while a touch of absurdity was given to the medley by the introduction of crude allegories, which showed bewigged and buskined notables posing on clouds or being hauled up to Olympus by fleshly Virtues. This school of painting had been steadily declining since Sir Peter Paul Rubens designed the Ceiling of the Banqueting Hall at Whitehall Palace, and under Verrio touched its nadir.

The contemporary architects were partly in fault; the huge waste spaces in their interiors invited this kind of 'filling up;' the King's staircase at Hampton Court is an example of this; atrocious as Verrio's paintings are, this vast, open, badly lit stairway would be intolerable were the walls left blank.

Thornhill's work was no worse than that of Verrio or Laguerre and had merits within the limits of its own strict conventions; Sir James was also deeply interested in his art and began his Academy with a sincere desire to further painting in England. There was little, however, that he could do for William Hogarth, who did not dare venture on the 'grand' style and would have found no employers if he had done so, and whose prospects as a painter were dubious for two reasons.

The first was his own dislike of becoming a hack portrait-painter, the only branch of the art that promised a livelihood, and the second was the fact that all the encouragement given to painting in England in the first half of the eighteenth century went to productions of the foreign school, mostly to those by defunct masters.

Hogarth's dislike for the 'phiz mongers' and his contempt for the dilettante were completely justified, though he persuaded but a few of his contemporaries to admit as much and was not quite sure of his own ground; it is difficult to be in a very small minority and to be entirely self-confident, and Hogarth based his judgment more upon instinct than upon knowledge; though his hits went home, they were often made in the dark.

Portrait painting had been declining since the period of the glory of Van Dyck; with Peter Lely the mass-produced pictures were in full vogue; what more obvious box of tricks could be displayed than the famous 'Beauties' where every lady has the same huge eyes, the same silken ringlets, the same tender, doll-like features with pearl and rose complexion?

No one could imagine a company of real people all as alike as these women are, but as the absurd convention was pretty and flattering, it was permitted, and the artist turned his studio into a factory where the drapery man and the dauber who dashed in wigs, hands and armour worked at the rate of 10 per cent of the painter's price.

This practice was continued by Hudson, the Highmores, the Richardsons, by Allan Ramsay, by painters of lesser note down to those journeymen-artists who wandered the country painting the well-to-do provincials, as the Primrose family was painted, with as many accessories, pet lambs, and pearls, as the artist could 'throw in' after he had been paid so much per head.

Hogarth, with his keen tendency towards realism, saw that his only chance as a portrait painter was to turn out these flattering figures with conventional details put in by the drapery man, and his spirit revolted against the prospect.

Yet any other style of painting was slain before its birth by the cognoscenti, who were in reality a combination of the fools who bought 'old masters' and the knaves who sold them; Hogarth was an artist full of originality and individuality and was faced with two very formidable obstacles, a deep-rooted fashion and a strong trade-interest.

The upper classes were all bitten by the mania for Italian painting, 'antique' statues and objets d'art or virtu; with some the taste was genuine and founded on a sense of civilized beauty, with more it was a custom; a great house was not considered furnished without its gallery of old masters and even more modest mansions had to boast a few foreign canvases if their masters were to claim any ton at all. Every lordling or esquire, fresh from Eton or Oxford, being bear-led by some pedagogue round Europe, was expected to return with trophies in the shape of 'old masters,' vases, bustos, or cameos—anything from a Raphael to a bit of trumpery as long as it came from abroad.

Naturally, this taste brought with it a crowd of profiteers, copyists, dealers, forgers, sham antiquaries, sham critics, and a swarm of sham enthusiasts, parasites on my lord's establishment, who praised his so-called Correggios to flatter his taste and opulence, or hangers-on of fashionable coteries, who raved over the last so-called Michael Angelo to be auctioned, merely to be dans le mouvement.

All these powerful people composed a very formidable array in the path of the poor native artist who had neither money nor influence and who was far too independent to seek out and cringe before a patron; he was, besides, secretly intimidated, despite his obstinacy, courage and self-confidence, by the sheer weight of public opinion.

The Academy was not a success; admittance to the sessions was free, and Hogarth thought that students stayed away because they 'would not put themselves under an obligation.' He continued, however, to think well of the scheme and to do all in his power to forward it; The Life School may be a painting of this Academy. Meanwhile he was intent on his own business, and, refusing to be a portrait manufacturer, turned out a number of small groups or conversational pieces, which sold very well, though at a modest price.

These were considered something of a novelty, but both the Dutch and French schools had exploited the idea, which consisted in showing a family or group of friends engaged in some pursuit and gathered in some scene that united them in a harmonious composition; Johann Zoffany, who did not come to London until the last years of Hogarth's life, brought this method of portraiture to perfection; there was a rigid grace, a conventional propriety about these little paintings by Hogarth that was quite foreign to the temperament of the artist, but that possesses a certain charm not wholly due to a 'period' interest.

Far more important was the fact that pictures such as The Cock Family, The Jones Family, or The Misses Cotton and their Niece were teaching the painter the technique of his art. One of these pieces took the form of scenes from The Beggars' Opera, the burlesque that was 'making Gay rich and Rich gay,' and included portraits of Lavinia Fenton and her future husband and present lover, Charles Paulet, third Duke of Bolton, who had lost all his places on account of his persistent opposition to Sir Robert Walpole; he was sixty-six years of age when the death of his Duchess (1751) enabled him to take the uncommon step of marrying a mistress who was also an actress.

William Hogarth's association with Sir James Thornhill brought about one very fortunate result for himself; he gained the respect, admiration and love of Jane, the knight's handsome daughter, a good, charming and stately young woman with blonde tresses, a fine complexion and a comely figure; her father had been handsome in a flamboyant style as his own self-portrait shows.

More important, her virtues were such as most fitted her to be the wife of a man of genius; she was patient, self-controlled, cheerful, unselfish, constant and firmly convinced of the greatness of her husband; throughout a married life of thirty-five years this admirable lady conducted herself in such a manner as to satisfy completely her pugnacious, opinionated husband, who, conscious of genius and often disappointed and thwarted, was not always either easy or good-humoured. Nor could he give his wife, born his social superior, the establishment to which she had been used as the only daughter of the Serjeant-Painter to His Majesty, who was besides a gentleman of position, who had recently bought back an imposing family seat in Dorset and was a Member of Parliament for Melcombe Regis (1722-34).

But Jane Hogarth was happy in the marriage to which she devoted her entire life, for her long widowhood was dedicated to her husband's memory; she knew sufficient of the art of painting to admire his superb technique and she was deeply in sympathy with his honest, bold, generous and slightly eccentric character.

Lady Thornhill approved a choice that must have seemed astonishing enough on the part of her handsome girl, for the young painter, though spruce and well-behaved, was lain to ugliness in his person and had no pretension to gentility.

It was, obviously, no match to suggest to Sir James, so one March morning in the year 1729 the determined young woman left her father's fine house in the fashionable Covent Garden district and proceeded to the village of Paddington, where she was married clandestinely to her resolute suitor in the pleasant little church on the Green.

There was nothing flighty, romantic or impulsive in this action, which was coolly and confidently decided upon and never repented of on either side; it showed that the unknown painter whose prospects seemed so poor had great trust in himself and that his chosen wife had a great trust in him; meanwhile the deceived father angrily refused any provision for the runaway daughter and William Hogarth had to support his Jane as best he could by engraving on plate, by book illustrations and conversation pieces.

He was over thirty years of age and still reaching out for complete self-expression; after ten years of work that was largely drudgery he had not 'found' himself.

The grand style continued to excite his ridicule and, secretly, his baffled envy; he felt that he could have achieved these great canvases of sacred or mythological subjects, if anyone had trusted him to execute them, yet he loathed them, for he had no interest in this false world created by the painters and a passionate interest in the world about him—that London, where he had been born, and where he always intended to live with his charming and devoted Jane.

There is no doubt that he would have felt less puzzled contempt for the historical style, if he had understood something of its traditions and purpose.

As Sir Joshua Reynolds, long after Hogarth's death, severely remarked: 'Hogarth...was entirely unacquainted with the principles of this style...and was not even aware that any artificial preparation was at all necessary.'

The famous President of the Royal Academy, who spoke thus, was no great exponent of this style himself, and it is not clear what he meant by 'artificial preparation,' unless he meant a journey to Italy to study the masterpieces of this school, which had been glorious in the days of Michael Angelo, Correggio and Raphael.

Such expensive study was always beyond William Hogarth, nor is it likely that, had he been able to undertake it, he would have changed his tastes or his opinions; the streets of Rome and Parma would have afforded him so much rich material for his sketch-book that probably he would have had little time for the sublimities of the Sistine Chapel, or for what another adverse criticism of the grand style termed Allegri's 'hash of frogs' on the ceiling of the Duomo, Parma.