a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Sketch of the History of Van Diemen's Land. Author: James Bischoff. * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1401091h.html Language: English Date first posted: March 2014 Date most recently march 2014 Produced by: Ned Overton. Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Production Notes:

A special character in this work, ![]() , has been interpreted to mean

"per", and is rendered here as [per].

, has been interpreted to mean

"per", and is rendered here as [per].

The font size of the Note to Chapter V. and the Appendix have not

been reduced.

The map of Van Diemen's Land [by J. Arrowsmith] is available

online from Trove as Map No. nk2456-173.

VAN DIEMEN'S LAND COMPANY'S ESTABLISHMENT AT CIRCULAR

HEAD.

BY

LONDON:

JOHN RICHARDSON, ROYAL EXCHANGE.

____

1832.

G. WOODFALL, ANGEL COURT, SKINNER STREET, LONDON.

{Page iii}

TO

GOVERNOR OF THE VAN DIEMEN'S LAND COMPANY.

my dear sir,

I cannot allow the following Sketch to go forth to the Proprietors of the Van Diemen's Land Company and to the Public, without making some, though very inadequate, acknowledgement of the obligations which are due to you for your constant and unwearied attention to the interests of that Company from its commencement. Your time has on all occasions been devoted to them; your experience and excellent judgment have greatly contributed to encourage Edward Curr, Esq., the chief agent in Van Diemen's Land, in his arduous duties, than whom few men have had to contend against greater trials, but they have been surmounted by his prudence, firmness, and talent. He has invariably met with the support of yourself, Joseph Cripps, Esq., Deputy-Governor, and the Directors, which has enabled him to overcome many difficulties, and, by unremitting steadiness and perseverance, to place the concerns of the Company in their present satisfactory condition.

The advantage of your advice and exertion has been equally felt at home; you preside over a Court of Directors, not surpassed in weight and respectability by any in London, drawn together by the large stake they individually hold, and by the confidence placed in them by the Proprietors. The prosperity of the Company has been their only object, private feeling and private interest have invariably given way to the general good, every question has been discussed with candour, and the good humour and those friendly feelings which prevail, render the meetings of Directors pleasant and efficient. To yourself the Company is much indebted. May you long live to witness the harmony and the increasing success of these exertions.

I cannot close this address without also expressing my sincere and heartfelt thanks for the kindness and attention invariably received from yourself, Mr. Cripps, and the Directors, for the generous confidence placed in me, and the assistance so cheerfully and effectually rendered to me in the important and sometimes difficult duties of my office: these have made an impression which no time can efface. I have the honour to remain, with great regard and respect.

My dear Sir,

London, 7th April, 1832.

{Page vii}

In order to make the Proprietors of the Van Diemen's Land Company acquainted with the country in which they have invested their properly, it has been thought desirable to give a brief Sketch of the History of that interesting island, to point out some of the difficulties against which early settlers have had to contend, the manner in which they have been surmounted, and the prosperity which has resulted from their industry and perseverance, that by comparing themselves with other colonists, the Proprietors may be enabled to form a just estimate of their prospects, not only from produce which forms annual income, but from the increased and increasing value of their permanent investment in land.

The review of the annals of Van Diemen's Land has been a matter of no difficulty, being a compilation from very few books, to which is added information derived from private letters and from individuals who have visited the colony. The Compiler, not having been there himself, is indebted altogether to the accounts of others. It has required no research amongst ancient and valuable manuscripts deposited in college libraries and the British Museum, no knowledge of ancient language, or indeed of any language, save his native tongue, for the space of time which this History embraces is confined to the life of man. Fifty years have scarcely elapsed since our great navigator. Captain Cook, visited the Southern Ocean, made known to the world the accession of its immense continent, with numerous beautiful and fruitful islands, and the British settler who first set foot in Van Diemen's Land, A. Riley, Esq., a respectable London merchant, is yet amongst us.

We are still in the dark as to many most essential points in natural history; the visiters to and writers upon Australia have not possessed that scientific knowledge which has enabled them to give a philosophical account of the character and properties of its productions. A rich field is here open for science; the peculiar nature of the animal world so totally different in some particulars from that of Europe, has not been sufficiently studied by the anatomist; the properties of the vegetable have not yet undergone the searching analysis of the chemist, and the mineral world has not been laid open to the geologist. Still, however, much valuable information is given in the works of Curr, Evans, Widowson, the anonymous writer of "The Picture of Australia," and of "An Account of Van Diemen's Land," lately published at Calcutta; to which must be added, "The Van Diemen's Land Anniversary, or Hobart Town Almanac." From these books, the Compiler of the following sheets has made copious extracts; but if the Proprietors wish to become thoroughly acquainted with the subject, each should supply himself with those publications, it being impossible by any extracts to do justice to them.

After this brief and imperfect History of the Island, the Compiler has given some account of the present system of carrying into effect secondary punishment by sentence of transportation, comparing it with the manner in which convicts were formerly treated, in order to shew that it has now not only become an incentive and a premium to crime at home, but places the criminal in a much better situation than the honest, industrious, but poor emigrant. And in conclusion, the Compiler has given some account of the establishment and progress of the Van Diemen's Land Company, adding an Appendix containing extracts from Parliamentary Papers, giving much interesting information respecting the Aborigines of Van Diemen's Land.

{Page x}

| Dedication Preface Discovery—History—Stores—Riven—Lakes—Character—Surfuce—Soil—Climate Natural Productions—Progress of Cultivation—Aborigines Difficulties of first Settlers—Sheep, Cattle, Horses—Table of Population—Live Stock—Acres of Land under Cultivation—Wool imported into Great Britain from Australia—Fisheries—Commerce—Table of Imports from and Exports to Van Diemen's Land—Gardens—Hobart Town—Launceston—Roads—Ports—Towns—Mountains. Convict Labour and Emigration—Prospects of Proprietors and Settlers. History of the Van Diemen's Land Company—Object—Particulars of the Charter and Act of Parliament, and Extracts from Annual Reports. Van Diemen's Land Company's Report in the year 1832, Note to Chap. V.—Journeys in the Interior Appendix.—Treatment of the Aborigines |

Van Diemen's Land,

by J. Arrowsmith.

[NLA Map No. nk 2456-173.]

[Click on the map to enlarge it.]

{Page 1}

A

SKETCH,

ETC.

Discovery—History—Shores—Rivers—Lakes—Character—Surface—Soil—Climate.

"The existence of New Holland and Van Diemen's Land was not known, with anything like certainty, till long after the discovery of America, of the passage around the Cape of Good Hope, and of the islands in the Indian seas, as far as Timor, Ceram, and some parts of the coast of New Guinea. There are some disputes, or at least obscurities, as to the time of the original discovery and the nation that made it. The French writers on Australian voyages, the president De Brosses and the Abbé Prévot, claim the merit for a countryman of their own. Captain Paulovier Gonneville, who sailed from Honfleur in the month of June 1503, was caught in a furious tempest off the Cape, lost his reckoning, and drifted in an unknown sea, from which he escaped by observing that the flight of birds was towards the south; and following them. Gonneville lived six months on the land, to which he gave the name of Southern India; and during the time, he occupied himself in refitting his vessel, and at the same time carried on a friendly intercourse with the natives, whom he mentions as having made some advances in civilization. Now all the more recent voyagers who have visited the north coasts of New Holland and had a sight of the natives, (we can hardly call it intercourse,) represent them as being without the very first elements of civilization, and so treacherous and cruel in their dispositions, that no friendly terms could be kept with them. These considerations, and the additional one that, from the French captain's account, the people on whose island he lived were very like the inhabitants of Madagascar, render it almost certain that that was the island on which he spent the six months." *

[* Picture of Australia.]

Portugal next claims the discovery. It is stated, that in the Library of the Carthusian Friars at Evora, there exists an authentic manuscript atlas of all the countries in the world, with richly emblazoned maps, made by Ternao Vaz Dourado, cosmographer in Goa, in 1570. In one of the maps is laid down the northern coast of Australia, with a note: This coast was discovered by Ternao de Magathæus, a native of Portugal, in the year 1520.*

[* East India Magazine.]

"It is probable, that in the early part of the sixteenth century, the Dutch or the Portuguese, in their way to or from the Spice Islands, may have discovered part of the coast; and in an old French chart, dedicated to the King of England, with an English copy, date 1542, in the British Museum, a portion of coast to the south of the Spice Islands is laid down and named Great Java, but whether it be New Holland or New Guinea is not known. The position of some of the coasts certainly gives it a resemblance to the north-east of New Holland, which could hardly be the result of accident

"In 1605, the Duyfhen, Dutch yacht, sailed from Bantam, in Java, for the purpose of exploring New Guinea; and from the account given, both of the country and the people, (who killed part of the crew,) it is evident that the main land of New Holland, to the south-west of Cape York, was seen in 1606.

"But the first certain discovery was of the west coast, by the Dutch, in 1616. The French expedition of discovery, sent out in 1801, found upon Dirk Hartog's Island, off Shank Bay, in latitude about 25° S., a pewter plate, which settled the point. It bore two inscriptions by different persons, and at different times. The first was, '1616, on the 25th of October, the ship Endraght, of Amsterdam, arrived here, Captain Dirk Hartog, of Amsterdam.' The second inscription was to this effect: '1697. on the 4th of February, the ship Geelvink, of Amsterdam, arrived here, Wilhelm de Vlaming, Captain-Commandant,' and mentions two other vessels with her." *

[* Picture of Australia.]

The island of Van Diemen's Land was first visited in the year 1643, by the Dutch navigator Abel Jansen Tasman, who gave its name in honour of Anthony Van Diemen, at that time Governor-General of the Dutch possessions in the East Indies. Captain Furneaux, in the Adventure, who accompanied Captain Cook on his second voyage round the world, visited it in 1773; he is supposed to have been the first Englishman who set foot In the island, and gave the name of his ship, 'Adventure', to the bay he entered.

Van Diemen's Land lies between the parallel of 40° 20" and 43° 40" south latitude, and between the meridian of 144° 30" and 148° 30" east longitude; its extent, from north to south, is about 200 miles, and from east to west, about 160 miles, containing an area of about 15,000,000 superficial square acres of land, or having a surface about equal to the size of Ireland.

Captain Cook touched at Van Diemen's Land on his third voyage in 1777; he cast anchor in Adventure Bay, and took in wood and water. He, however, supposed it to be the most southern part of New Holland; his expression is, "I hardly need say, that it is the southern point of New Holland, which, if it doth not deserve the name of a continent, is by far the largest island in the world." *

[* Cook's Voyages.]

"Dr. Bass, in 1798, discovered that Van Diemen's Land was an island, separated from New Holland by a strait now bearing his name.

"Lieutenant Bowen landed on the east bank of the Derwent in 1803, and first took possession of the island.

"Colonel Collins, the first Lieutenant-Governor, arrived in 1804, established himself on the west side of the river Derwent, and formed a settlement, giving it the name of Hobart Town; the limits of three counties were defined, viz., Northumberland, Cornwall, and Buckinghamshire.

"Colonel Patterson arrived in the river Tamar, from Sydney, in the same year, and pitched his tent on a plain on the west bank of that river.

"Lieutenant-Governor Collins died, at Hobart Town, in 1810, and from that time till 1813, the government of the colony was administered by different military officers, as they successively had the command.

"The second Lieutenant-Governor, Colonel Davey, arrived at Hobart Town in 1813; the ports were then first opened to commerce, and put upon the same footing as those of New South Wales, merchant ships having been prohibited from entering the harbours." *

[* Van Diemen's Land Almanack.]

The third lieutenant-Governor, Colonel Sorell, was appointed in 1817, a man of liberal and enlightened mind, eminently qualified for developing the character and resources of the island. Under his government, the nature of the country, the fertility of the soil, and its various capabilities and products were made known; and, in 1819, the emigration of free settlers from England first commenced. That may indeed be considered the period from which its prosperity took its rise; since then the beneficial effects of industry and capital have been displayed; Englishmen are now established on lands which had recently been the range of the kangaroo, and the hunting ground of the wretched savage, who, without domicile, wandered about in precarious search of food; forests are now brought under cultivation and stocked with herds of cattle and flocks of sheep. A great portion of the island already answers the beautiful description of the poet:

"On spacious airy downs and gentle hills

With grass and thyme o'erspread, and clover wild,

Where smiling Phœbus tempers every breeze,

The fairest flocks rejoice."

dyer's fleece.

Under the government of Colonel Sorell, roads were cut through the woods from the south to the north extremity of the island, from Hobart Town to Port Dalrymple, as well as between other chief settlements in the interior.

The present Lieutenant-Governor, Colonel Arthur, succeeded Colonel Sorell, in 1824; a man in every way well qualified to pursue the judicious plans of his predecessor. Devoting all the energies of a strong and enlarged mind to advance the permanent prosperity of the colony placed under his charge, he has visited different parts of the island, caused roads and bridges to be constructed, and has divided the settled part of the country on the east side of the island into nine police districts, viz., Hobart Town, Norfolk, Richmond, Clyde, Oatlands, Oyster Bay, Campbell Town, Launceston, and Norfolk Plains.

Till this period the island of Van Diemen's Land, though having a lieutenant-governor, was under the government of New South Wales; but, in 1825, it was, by royal proclamation, declared independent thereof, the lieutenant-governor acting from orders transmitted to him from the colonial department.

Respecting the general character of the island, much valuable information is given in the Hobart Town Almanack for 1831, published by Dr. Ross. These animals are equally interesting to the inhabitants of Van Diemen's Land and to Europeans at home. The following particulars are extracted from that work:

"The general character of the surface of Van Diemen's Land is hilly and mountainous, the hills being mostly covered with trees to the height of between three and four thousand feet, where the difference of climate in that lofty and exposed region checks vegetation, and exposes to the eye, as the mountains rise upon the horizon, a comparatively naked and weather born barren aspect, being for five or six months in the year, from April till October, more or less covered with snow.

"This hilly character of the country, especially on the southern side of the island, admits but of little interruption. The hills are not only frequent but continuously so, the general face of the island being a never ending succession of hill and dale: the traveller no sooner arrives at the bottom of one hill than he has to ascend another, often three or four times in the space of one mile, while at other times the land swells up into greater heights, reaching along several miles of ascent. The level parts, marshes or plains, as they are called in the colony, giving relief to this fatiguing surface, are comparatively few. The reader, however, must not conclude either that the hills of the island are all sterile or the plains all fertile; on the contrary, though most of the large hills and mountains are either too steep and rocky, or too thickly covered with timber, to admit of cultivation, a large proportion of the more moderately sized hills and gentler undulations are thickly covered with herbage, presenting to the view an agreeable succession of moderately wooded downs, and affording excellent pasture for sheep and cattle. Altogether, and on the most liberal computation, the productive surface of the island cannot fairly be estimated at more than one-third. To one accustomed to the moist climate and plentifully watered countries of England, Scotland, and Ireland, Van Diemen's Land, at first sight, may present a dry and unproductive appearance; but upon a nearer acquaintance, it will put on a more inviting aspect." *

[* Hobart Town Almanack.]

"The shores of Van Diemen's Land are much more bold in their general character than those of New Holland, and at some points they afford scenery as grand as can be found in any part of the world. One of the most remarkable characteristics of the seas around Australia is the numerous islands with which they are studded, and the small elevation of most of them above the level of the sea. On the shores of Van Diemen's Land these islands are sometimes of a different character, being pyramids of rock presenting a columnar or basaltic appearance; on the south, some of them also partake of the high and cliffy nature of that coast. In glancing over a correct chart of the Australian seas, there are several places where the formation of islands is more than ordinarily conspicuous. Bass's Straits is full of them, and soundings are met with, at no very great depths, in all the channels. These islands indicate the continuation or a submarine ridge from the termination of the eastern mountains of Van Diemen's Land at Cape Portland to the high land of Wilson's promontory in New Holland; and probably this is the only place at which New Holland can be traced as having a geological connexion with any other land, unless indeed we consider that there is a similar connexion between Cape Grim on the south entrance to Bass's Straits, and Cape Otway on the north-west of the coast Such a connexion, though not quite so continuous as the former, may be traced by Hunter's Islands on Van Diemen's Land coast, to King's Island in the middle of the channel."

"The principal harbours are in the Derwent and the Tamar, to which must now be added Circular Head and Woolnorth, a very good channel having been recently discovered there, which will admit a vessel of 500 tons burden, and nothing else was wanted to make the harbour safe and desirable.

"Around Van Diemen's Land the winds are generally from the west and south, and the ports, more especially the Derwent, are accessible at all seasons.

"The two principal rivers, the Tamar in the north, and the Derwent in the south, overlay each other, the remotest source of the Derwent being within fifty miles of the north coast, and that of the Macquarrie, the most remote branch of the Tamar, being not more than forty miles from the tide-way in the Derwent and Coal rivers. The country midway between the mouths of the two rivers, is not what can, strictly speaking, be called mountainous, though it is considerably elevated. One of the most remarkable of its characteristics is, that between the sources of the Macquarrie, which runs to the Tamar, and those of the Jordan, which runs to the Derwent, there is a salt plain. In that plain there are three pools or hollows which are filled with water during the rainy season, but which are dried up by evaporation when the rains are over; and so strongly is the water of these hollows, and consequently the soil over which it flows and through which it percolates, impregnated with salt, that a considerable quantity is collected every season for domestic purposes.

"As the entrance of the river Tamar is approached, the country becomes fertile down to the water's edge, and forms a pleasant contrast to the dry and sandy shores of New Holland. The estuary of the Tamar is navigable much further into the interior than any of the rivers in New Holland: it winds considerably, and there are some banks in it, but the tide rises fifteen feet at Launceston, which is forty-three miles from the sea. The land on the banks of this river is in many places very good, and in general is well wooded.

"The branches of the Derwent indicate an extensive valley or series of smaller valleys connected with that river. The breadth from the most easterly sources of the Jordan to the western mountains, is not less than eighty miles in a straight line; and the length from the remotest source to Hobart Town, is about 150, so that that river drains an extent of 12,000 square miles of country, and though there be occasional mountains and unproductive places, the general character of that extensive district is fertility. At Hobart Town, the valley of the Derwent may be said to terminate, for though the entrance be full forty miles further before the open sea is reached, the heights connected with Mount Wellington close up the valley on the west, and the Coal River Comes near to the Derwent on the east.

"The fresh water which gets the name of Derwent, is not the principal branch, but one that comes from the western mountains; the one which is, as it were, the main stem of the river is the Ouse, which rises about forty miles from the north coast, and the same distance from the west.

"About the parallel of 42 degrees south, there are a number of lakes, the largest is Lake Arthur, estimated at about fifteen miles long and five broad; that lake is the source of the Shannon, the first branch that fells into the Ouse on the east side. The Clyde and the Jordan arc the other principal branches on the east side; they both originate in lakes and marshes, and the plains through which they pass, more especially those on the Jordan, are very fertile and beautiful.

"The Macquarrie, which has its source near those of the Clyde and the Jordan, is the largest branch of the Tamar. The grounds through which it passes are in general rich, as are also those on the banks of the South Esk, which rises in the eastern mountains near Tasman's Peak, and flows towards the north-west. The North Esk is the other principal branch of the Tamar: it joins the South Esk at Launceston, and is a romantic little river, but its course is too precipitous and is not available for the purposes of navigation." *

[* Picture of Australia.]

The rivers and streams which intersect the island in every direction on the north-west quarter of Van Diemen's Land, are frequent; the Avon, Mersey, Don, Forth, Leven, Blythe, Emu, Cam, Inglis, Detention, intervene betwixt the Tamar and Circular Head; and between that and Cape Grim Head, are Dutch River, Montague, Harcus, and Welcome. All these, rising far in the interior of the island, empty themselves into Bass's Straits, whilst the Hellyer and the Arthur rising the Surrey Hills, fall into the Indian Ocean, on the western coast. Some of these numerous streams will probably serve for internal navigation, they are of infinite use in fertilizing the large extent of country through which they pass; but the navigation at their mouths is interrupted in general by bars, over which vessels drawing more than four feet water cannot pass. The principal harbours on the north-west coast of the island are Emu Bay, Circular Head, and Woolnorth.

"Few, if any, attempts have yet been made to classify or analyse the mineral productions composing the superficial strata or subsoil of the island. Limestone is almost the only one that has yet been brought into general use; this requisite of civilized life has been found in abundance in most parts, with the exception of the neighbourhood of Launceston, to which place it is usually imported from Sydney, as a return cargo, in the vessels that carry up wheat to that port. Marble of a white mixed grey colour, susceptible of a good polish, has frequently been found, though never yet dug up or applied to use. Iron ore is very general, of a red, browti, and black colour; in one or two instances it has been analysed, and found to contain eighty per cent of the perfect mineral; it also occurs, though more rarely and in smaller quantities, under the form of red chalk, with which, mixed with grease, the Aborigines besmear their heads and bodies. Indications of coat have been found all across the island. Of the various species of the argillaceous genus, basalt is by far the most abundant, indeed it would appear to be the chief and predominant substratum in the island; all along the coast it presents itself in rocky precipitous heights, standing on its beautiful columnar pedestals; of these. Fluted Cape at Adventure Bay is perhaps the most remarkable, so called from the circular columns standing up close together, in the form of the barrel of an organ. Circular Head, which gives the name to the Van Diemen's Land Company's establishment, is another remarkable instance of the singular appearance which this species of rock puts on, resembling different artificial productions of man. That curious rock stands like a huge round tower or fortress, built by human hands, which stretching out into the sea, as if from the middle of a bay, is joined to the land by a narrow isthmus, and has a small creek on each side. In some parts, both on the coast and in the interior, the columns stand in insulated positions, springing up from the grass or the ocean, like obelisks or huge needles, and presenting a singular appearance to the eye. As basaltic rock has the power of acting on the magnetic needle, and occurs in such large masses, it in some measure accounts for the variations which travellers, depending upon the guidance of the pocket compass, when in the bush, sometimes experience. Argil also appears in the form of excellent roof slate; and in that of mica, it is in large masses. Excellent sandstone, for building, is found in every part of the island. Flints, in great plenty, are scattered upon the hills. Other rare species of the silicious genus have been found in different parts of the island, especially in those which appear to have been washed, in former times, by the ocean, and which have been deposited in certain ranges or linear positions, by the lashing of the waves and the subsiding of the waters; of these may be mentioned, though found generally in small pieces, hornstone, schistus, wood-opal, bloodstone, jasper, and that singular species called the cat's-eye, reflecting different rays of light from the change of position.

"Of the metallic ores, besides iron, which is most abundant, specimens of chromate of iron, of red and green copper ore, lead, zinc, manganese, and some say of silver and gold, have occasionally been found, but the latter, we think, is not to be relied on.

"Petrified remains of wood and other vegetable productions, entirely converted into silicious matter, and capable of the finest polish, are occasionally met with.

"According to the latitude of Van Diemen's Land, it ought to enjoy a climate equal to that of the southern parts of France or the northern parts of Spain and Italy, along the coasts of the Mediterranean; but the general temperature of a country is affected by other circumstances besides that of latitude, and geographers have generally agreed that the great extent of uninterrupted ocean round the south pole, compared to that of the northern hemisphere, where land so much more abounds, makes a difference in the climate equal to several degrees of latitude. It would appear that this difference is scarcely sensible, under the fortieth degree of latitude; for while the summer heats of Buenos Ayres, the Cape of Good Hope, and Sydney, are as great as at Gibraltar, Tunis, or Charleston, or Bermuda in America; Patagonia, New Zealand, and Van Diemen's Land have a temperature almost as cold in the summer season as that of London, Brussels, or at least Paris and Vienna. While, therefore. Van Diemen's Land has a portion of the sun's rays and a length of day equal to that enjoyed by the inhabitants of Rome, Constantinople, or Madrid, in the mildest winter, its summer heats are so moderated as to be not only congenial, but delightful, to a person who has lived to maturity in an English climate, and whose system has been habituated to it; however warm the middle of the day may be, it is invariably attended by a morning and evening so cool, as completely to brace the body and counteract any enervating effects that the meridian beat might have occasioned; and while the summer heat is thus moderated, the inclemency of winter is dissipated by the equality of temperature diffused from the extent of ocean surrounding its insular position.

"Except on the days when rain actually falls, which, on an average, do not exceed fifty or sixty in the year, the sky is clear and the sun brilliant, the atmosphere is consequently, for the most part, dry, pure, and elastic, which renders the system in a great measure insensible to the sudden changes of temperature that so frequently occur. In the winter, the frost at night, except in the higher regions of the interior, or in some deep dell, where the sun's rays scarcely ever reach, is never so severe as to withstand the heat of the ensuing day. Sleet or snow generally falls once or twice a year, but never lies on the ground above a day or two, except on the tops of the mountains or in the central parts of the island, where it has been known to continue for a week or ten days.

"In so clear a sky, as might be supposed, the serenity of the starlight and moonlight nights calls forth the notice and admiration of every one susceptible of the charms of nature; few parts of the globe are more favourable for obtaining a knowledge of the constellations, or for alluring the young to the delightful science of astronomy. A summer's morning, at all times beautiful in the country, is peculiarly so in Van Diemen's Land. In such a climate, and with the active life which settlers in a new colony must necessarily lead, the health of the inhabitants, as might be supposed, is of the best kind.

"On the whole, it may be fairly estimated from all the experience that the present young state of the colony affords, that the chances of life and longevity are twenty per cent, better in Van Diemen's Land than in England." *

[* Van Diemen's Land Almanack.]

A book was published at Calcutta, in 1830, giving an account of Van Diemen's Land, principally intended for the use of persons residing in India, and shewing the advantages it holds out to them for their residence; the following is extracted from that work.

"Its climate seems so well adapted to the renovating of the constitution of those who have suffered from their residence in India, that it only requires to be pointed out, and the easiest manner of getting there made known, as also the cheapness and comfort of living, when there, to turn the tide of visitors to the Cape and the Isle of France, towards its shores.

"Many, also, who have saved what would only afford a bare existence in England, or indeed any part of Europe, might, with the addition of their pension, live with the greatest comfort in this country; but are deterred from making the experiment, from the little faith that can generally be put in the publications on emigration; and from the want of correct information on points having a direct reference to their own peculiar circumstances and previous habits of life." *

[* An Account of Van Diemen's Land.]

{Page 22}

Natural Productions—Progress of Cultivation—Aborigines.

The natural productions of the island are well described by Mr. Widowson in his work containing much valuable information. The following is extracted chiefly from it.

"The stringy bark is perhaps one of the most useful trees in the island; it is found in low swampy places, and grows from forty to seventy feet high; it is a hard straight grained wood, and principally used in building and fencing; the bark, which serves as a covering for splitters and sawyers is easily separated from the wood in immense large strips.

"The blue gum is found in greater abundance; it is a loose grained heavy wood and grows to an immense size. The lesser trees have been frequently used for masts for small vessels, and are found to answer well; the greater number of colonial boats are built of blue gum; the oars are made of the same wood, but they appear to retain their natural moisture for years, as they sink instantly when dropped into the water. This wood is also used for building purposes, but requires to be particularly well seasoned; when dry it is extremely tough and durable.

"The peppermint, so called from the leaves imparting to the taste that flavour, grows every where throughout the island. This tree is of very little use except for shingles; in the forests, it may be sometimes seen rearing its lofty head conspicuously above the rest to a surprising height.

"The black and silver wattle (the mimosa) are trees used in house-work and furniture; but from their diminutive size are not much sought after. The bark of the former is exported to England in large quantities. The mimosa bears immense branches of yellow flowers, in the spring they have a most beautiful appearance, and would form a delightful contrast to an English chestnut.

"The ground saplings grow in clumps resembling our ash-poles in form, and may be easily converted to the same uses.

"Huon pine is by far the most beautiful wood found in the island; it is very superior both in colour and substance to the Norway deal, but is scarce and difficult to be had.

"Adventure Bay pine is found at the extremity of the deep bay of that name; it is a species of pine adapted for house-work and furniture, but is not common.

"The light wood found by the sides of creeks and swamps, grows larger in the top than any tree of the same size; the wood is extremely hard and light. Mill-wheel shafts and cogs are made from this wood, and found to answer better than any other kind.

"The cherry-tree is a small diminutive plant found on rocky hills and poor land; it is more used for the fire than any thing else. Gunstocks are made of it, but they do not last long. Honeysuckle is found in various parts: the cherry, the oak, and the honeysuckle are companions.

"The trees and forests of Tasmania (with but one exception, the mimosa) rather diminish than add to the beauty of the country; where they are thinly spread, the tops grow extremely ugly, and bear not the slightest resemblance to the worst of our oak and elm. Two or three of the larger kinds of tree shed their outward bark instead of leaves, and slips forty or fifty feet long are seen hanging down from the top to the bottom, presenting a most unsightly appearance.

"The mimosa is by far the most beautiful and indeed the only tree to which nature seems to have given the appearance of ornament. All the native trees of Van Diemen's Land, are evergreen.

"The shrubs of Tasmania are very numerous, and some of them beautiful; a few have been transplanted from the forests and scrubs to the pleasure grounds of the wealthy.

"The tea-tree grows in wet situations, and in clusters along the banks of rivers and mountain streams; the leaves infused, make a pleasant beverage, and with a little sugar form a most excellent substitute for tea. The natives select their spears from among the straightest and largest sticks of the tea-tree. Of fruits there are none indigenous in the island worth noticing. The native cherry, currant, cranberry, or any other are as ungrateful as the crab of England. The musk-plant, the cotton plant, the native myrtle, the human and others are the common shrubs of the country; the currogong is sometimes found, its inner bark may be manufactured into ropes.

"The native grasses of the island very for exceed those of any other country, and if properly cultivated, would unquestionably be most productive." *

[* Widowson's Present State of Van Diemen's Land.]

"Though some of the quadrupeds of Van Diemen's Land and New South Wales have their teeth so constructed as to feed only on grass, others have teeth adapted for the gnawing of bark, and others again have canine teeth, and live upon animal food. They differ in one striking particular from all the quadrupeds of the other parts of the world, with the exception of one or two genera, which are not very extensively diffused, being confined to America and the south-east of Asia. The peculiarity of the Australian quadrupeds, which may be taken as their distinguishing characteristic, is the attachment of a sack or pouch of the cuticle to the abdomen of the female, which partially in all instances and entirely in most covers the teats and opens anteriorly. Into the pouch the young are received in a small formless and embryo state, and they remain fixed to the teats till they are perfectly formed and have acquired 8 size proportionate to that of the parent animal, at which time they are detached, and the teat, which had previously been extended, slender and probably reaching the stomach of the young animal, becomes shortened, so that the young can then suck milky nutriment like other mammalia.

"From this peculiarity in their formation, the whole class have received the name of 'marsupiata,' or pouched animals, without reference to the structure of their teeth, or the habits of the genus or species." *

[* Widowson's Present State of Van Diemen's Land.]

"Kangaroos, of which there are three or four varieties, constitute the grazing animals. Their characters, (and excepting size and colour, their appearance,) are in all the species and varieties nearly the same. The head is small, the month destitute of canine teeth, the eyes large, and the ears erect and pointed. The fore part and fore legs of the animal are small, the latter being divided into five toes armed with strong claws. Towards the hind quarters the whole of the race get comparatively thick and strong, and the hind legs are long, powerful, and remark. ably elastic. The hind feet are singularly formed, they terminate in three toes, the central one remarkably long, and armed with a claw. The bottom of the feet is covered with an elastic substance, more abundant and yielding more readily to pressure than that found on the foot of almost any other animal. Some idea of the power of a kangaroo's hind leg may be formed from the fact that the elasticity of the two legs is sufficient, without any fulcrum, to throw an animal, weighing between two and three hundred weight, a distance of sixty, or, it is said, sometimes even ninety feet at a single bound, and that the instant the feet touch the ground, the animal is elevated to another leap. The tail is large and very muscular." *

[* Picture of Australia.]

"There are three or four varieties of kangaroos; those most common, and which furnish sport in the chase, are denominated the forester and brush kangaroo. They grow to an immense size, and have been known to weigh twelve stone. Kangaroos frequently herd together; they are remarkably swift, and bound from fifteen to twenty feet at first starting.

"The brush kangaroo is much smaller and frequents the scrubs and rocky hills.

"The wallabee is not very common, although found in abundance near the mountains; they seldom weigh more than twenty-five or thirty pounds, and are much superior in flavour to any others of the kangaroo species.

"There are two kinds of opossums, the large or grey, and the ring-tailed; they are both very harmless, and in shape not unlike the pole-cat They live in the hollow of trees, and feed upon the leaves of the peppermint and young grass. The skins of these animals are very beautiful.

"The kangaroo rat is a small inoffensive animal, and perfectly distinct from the ordinary species of rat, indeed it may be called the kangaroo in miniature; it is about the size of a wild rabbit, and bounds exactly like a kangaroo.

"The bandicoot is as large as a rabbit. There are two kinds, the rat and the rabbit bandicoot, they both burrow in the earth, and live upon roots and plants. The flesh of the latter is white and delicious.

"The opossum mouse is about the size of our largest barn mouse, it is a fac simile of the opossum; when caught it soon becomes very tame like the rest of the animals in the island. Manna is the food they exist upon, they are exceedingly pretty, and their skins impart the most agreeable aromatic scent.

"The native porcupine or echidna is not very common nor so large as that found in America. It appears to be a species of animal between the porcupine and hedge-hog; it is quite harmless.

"The only animals that can be termed carnivorous, are the small hyena, the devil, and the native cat. The hyena, or as it is sometimes called the tiger, is about the size of a large terrier. It frequents the wilds of Tasmania, and is scarcely beard of in the located districts. "When sheep run in large flocks near the mountains, these animals destroy a great many lambs. The female produces five or six at a birth: the skin resembles the striped hyena.

"The devil, or as naturalists term it, 'dasyurus ursinus,' is very properly named, if it is meant as a designation for the most forbidding and ugly of the animal creation. It is as great a destroyer of young lambs as the hyena, and, generally speaking, is as large as a middle sized dog. The head resembles that of an otter in shape, but is out of proportion with the rest of the body; the mouth is furnished with three rows of double teeth; the legs are short with the feet similar to the cat, being covered with a tough skin free from hair; the skin resembles the sable in colour; the tail is short and thick; it is generally found in the clefts of rocks contiguous to the mountains, or on stony hills; the head appears to be full of scabs, as though the animal was diseased; they are very slow on their legs, are taken in small pit falls, and killed by dogs.

"The native cat resembles our pole-cat or weazel as to its mode of living. It is between the size of the two, and infests the hen-roosts, and is a great destroyer of all kinds of poultry. They are found in hollow trees and under dead timber: their skins are either grey or black spotted.

"The feathered tribes of Van Diemen's Land are numerous. The sea and other water-fowl consist of gulls of various kinds, boobies, noddies, shags, gornets, cormorants, pelicans, black swans (very abundant), the musk-duck, and all kinds of the duck tribe. The land birds, generally speaking, are all of them curious and beautiful. The numbers of various kinds of parrots and parroquets, clothed in the most beautiful plumage, are almost beyond description. The cockatoos are as great destroyers of corn, during the seed time and harvest, as crows are in England.

"Tasmania may be said to be entirely without singing birds, although the parroquets sing admirably when taught and rendered tame. The tribes of small birds are various, but very unlike any birds seen in England. The crows are similar to those in England, with the exception of white eyes. There are two kinds of magpies, the one completely black, the other like ours, but differently marked: neither is so mischievous or destructive.

"The birds of prey are, the eagle, owls, bats, and the different kinds of hawks, which are much like those in England. Many of the large hawks are perfectly white.

"The pigeons are by far the most beautiful birds in the island; they are called bronze winged pigeons. They are more like the partridge than the pigeon, and much more delicious to eat. The wings are beautifully variegated with gold-coloured feathers. They are wild, though easily shot off the stubble, where they feed in large quantities. There are smaller kinds of pigeons, and a beautiful species of dove, whose cooing is a melancholy tone."

"The birds that may be called game, are very numerous, with the exception of the emu or native ostrich, they very much resemble the latter bird, and are nearly as large. They leave the mountains to feed in the plains, and are sometimes caught by the kangaroo dogs. They are exceedingly swift, and, like the ostrich, have no power to raise themselves from the earth.

"The quail, of which there are three kinds, are far more numerous, in many parts of the island, than the partridge in England. They are much larger than the quail of any other country, and afford to the sportsman capital shooting.

"Snipes are found in great abundance, from September to March, in the lakes and wet valleys. They are precisely like the snipe of England, but not near so wild. Wild ducks and widgeons are also found in all the principal fresh water rivers.

"The bittern is rare and not frequently met with. Plovers are not numerous. There are two kinds, the golden and silver plover. The baldcoot, and a large bird called the native hen, and the heron frequent the lakes.

"The coast and harbours abound with various kinds of fish; few, or any of them, are known in Europe. The market of Hobart Town is principally supplied from the Derwent, with small rock cod, flat-heads, and a fish called the perch, and various others. Sharks and porpoises are common in the river, within a mile or two of the town, and several large black whales have been killed in the harbour.

"Of the several kinds of reptiles, none are so common as the snake; they-vary in size from one to six feet long. At the sight of a man, they generally make their escape into holes in the ground or beneath old trees.

"Centipedes, scorpions, and a small kind of lizard and frogs are to be seen, but not very commonly.

"The insects are not so numerous or so annoying as in most other countries. The ant, the mosquito, and a common green fly are chiefly seen. The mosquito does not sting so severely as in hotter climates." *

[* Widowson's Present State of Van Diemen's Land.]

The immediate neighbourhood of Hobart Town was the first part of the island brought under cultivation; and in order to induce emigration, grants of land were given by General Macquarrie, Governor of New South Wales, almost indiscriminately, to those who applied for them. The advantage of roads, and consequently the facilities of sending produce to Hobart Town, confined the settlements almost exclusively to a northern direction, which on that line passes through what was supposed to be the best land in the island; and as cultivation extended north from the Derwent to the Tamar, the quality of the land improved and the climate became milder; but till the late discoveries, which have been made by Mr. Hellyer and Mr. Fossey, the character of the whole surface of the island was supposed to be good. Mr. Widowson, who published his work on the present state of Van Diemen's Land so late as the year 1829, commences his introduction by the following account.

"Of all our ultra-marine possessions, vast and valuable as many of them are, no one excites so much interest, in the proper sense of the word, as our different settlements in New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land. They are not rich in mines, sugar-canes, cochineal, or cotton, but they are blessed with a climate, which, though different in different places, is yet, on the whole, favourable to the health, comfort, and industry of Europeans. They exhibit an almost endless extent of surface, various as to aspect and capability, but taken together, suited in an extraordinary degree to the numerous purposes of rural economy, the plough and spade, the dairy and sheep walk. The emigrant has not to wage hopeless and ruinous war with interminable forests and impregnable jungles, as he finds prepared by the hand of nature extensive plains ready for the ploughshare, and capable of repaying manifold in the first season." *

[* Widowson's State of Van Diemen's Land.]

Such, though perhaps stated in too glowing terms, was the character of the country between Hobart Town and Launceston, having extensive plains lightly timbered, upon which sheep might be immediately placed; but greater experience has shewn that such is not a faithful picture of those parts of Van Diemen's Land which have been lately explored.

The first difficulties experienced by settlers, even in that part of the island which best deserved the eulogium given to it, arose from those who had prior possession, the Bushrangers and the Aborigines. The Bushrangers were convicts who escaped from penal settlements, or from individuals to whom they had been assigned, formed themselves into banditti, and as Mr. Curr expressed it, "ranged the woods of the island, and for a period of six years committed the most cruel and daring robberies. Their leader, Michael Howe, was a notorious character, who was, after a long warfare, killed in October 1818, and who might be properly called the last of the Bushrangers." * From that period, little inconvenience has arisen from the ravages of banditti, though convicts have occasionally escaped and resorted to plunder and to concealment in the woods. The Aborigines have, however, continued their depredations upon the property of settlers, and some murders have very lately taken place. This is a subject which must occasion grief and distress to every man of common feeling. The original possessors of the land must have regarded the European settlers as invaders or uninvited, obtrusive guests; and the occupation of land and encroachment upon their hunting grounds, could be alone justified, by the hope that these degraded and wretched savages might be taught the arts of civilized life, and from a state of misery and precarious subsistence advanced to comfort and happiness. These objects ought to have been kept in view and perseveringly followed, and so far as it has been in the power of government at home to instruct, and the colonial government to follow their orders, every effort has been made to conciliate and civilize the Aborigines. Unable, however, to draw distinctions, they have regarded all white men as their enemies, and have visited the innocent with that cruelty and resentment which a savage must naturally feel for injuries received. Finding that all efforts to conciliate failed, it was at length determined to endeavour by one general effort on the part of the military and the settlers to surround the natives, to drive them to a corner of the island, where there was sufficient space allowed for their hunting and fishing, and then to prevent them from going to the located districts. This plan also has not succeeded; the savage was too well acquainted with the nature of the country, and eluded his pursuers; but since that time, a gentleman, Mr. G. A. Robinson, has nobly volunteered to visit the different tribes, and personally to risk his own life, by throwing himself unarmed amongst them, and endeavouring to induce them to accompany him to one of the islands in Bass's Straits, which will be assigned to the natives and to them alone. The various instructions and proceedings relating to this subject were printed by order of the House of Commons, 23d September, 1831, and as it must be interesting to every proprietor of this Company, it has been thought best, after giving an account of Captain Cook's first interview with the natives, so that their original character and disposition may be in some measure known, to give in an Appendix, ample extracts from those parliamentary papers.

[* Curr's Account of Van Diemen's Land.]

Captain Cook gives the following account of his first interview with the natives.

"We were agreeably surprised at the place where we were cutting wood with a visit from some of the natives, eight men and a boy. They approached us from the woods without betraying any marks of fear, or rather with the greatest confidence imaginable, for none of them had any weapons except one, who held in his hand a stick about two feet long and pointed at the end.

"They were quite naked and wore no ornaments, unless we consider as such, and as a proof of their love of finery, some large punctures or ridges raised on different parts of their bodies, some in straight and others in curved lines.

"They were of the common stature, but rather slender, their skin was black and also their hair, which was as woolly as any native of Guinea, but they were not distinguished by remarkably thick lips nor flat noses; on the contrary, their features were far from being disagreeable. They had pretty good eyes, and their teeth were tolerably even, but dirty; most of them had their hair and beards smeared with a red ointment, and some had their faces also painted with the same composition.

"They received every present we made them without the least appearance of satisfaction. When some bread was given, as soon as they understood that it was to be eaten, they either returned it or threw it away without even tasting it. They also refused some elephant flesh both raw and dressed, which we offered to them: but upon giving some birds to them, they did not return these, but easily made us comprehend that they were fond of such food. I had brought two pigs ashore, with a view to leave them in the woods. The instant these came within their reach, they seized them as a dog would have done, by the ears, and were for carrying them off immediately, with no other intention, as we could perceive, but to kill them.

"Being desirous of knowing the use of the stick which one of our visitors carried in his hand, I made signs to them to shew me, and so far succeeded that one of them set up a piece of wood as a mark and threw at it, at the distance of about twenty yards: but we had little reason to commend his dexterity, for after repeated trials, he was still very wide from the object Omai,* to shew them how much superior our weapons were to theirs, then fired his musket at it, which alarmed them so much, that notwithstanding all we could do or say, they ran instantly into the woods; one of them was so frightened that he let drop an axe and two knives that had been given to him. From us, however, they went to the place where some of the Discovery's people were employed in taking water into their boat. The officer of that party, not knowing that they had paid us a friendly visit, nor what their intent might be, fired a musket in the air, which sent them off with the greatest precipitation: thus ended our first visit with the natives.

[* A native of the South Sea Islands, who accompanied Captain Furneaux, and came with him to England.]

"The morning of the 29th January (1777) was ushered in with a dead calm, which continued all day and effectually prevented our sailing. I therefore sent a party over to the east side of the bay to cut grass, having been informed that some of a superior quality grew there. Another party, to cut wood, was ordered to go to the usual place, and I accompanied them myself. We had observed several of the natives this morning sauntering along the shore, which assured us, that though their consternation had made them leave us abruptly the day before, they were convinced that we intended them DO mischief, and were desirous of renewing the intercourse. It was natural that I should wish to be present on the occasion. We had not been long landed, before twenty of them, men and boys, joined us without expressing the least sign of fear or distrust. There was one of this company conspicuously deformed, and who was not more distinguishable by the hump on his back, than by the drollery of his gestures and the seeming humour of his speeches, which he was very fond of exhibiting, as we supposed Tor our entertainment. Some of our present group wore loose round their necks three or tour folds of small cord, made of the fur of some animal, and others of them had a narrow slip of kangaroo skin tied round their ankles.

"After staying about an hour with the wooding party and the natives, as I could now be pretty confident that the latter were not likely to give the former any disturbance, I left them, and returned on board to dinner, where, some time after. Lieutenant King arrived. From him I learnt that I had but just left the shore, when several women and children made their appearance, and were introduced to him by some of the men who attended them; he gave presents to all of such trifles as he had about him. These females wore a kangaroo skin, in the shape as it came from the animal, tied over the shoulders and round the waist; but its only use seemed to be to support their children when carried on their backs, for it did bot cover those parts which most nations conceal, being in all other respects as naked as the men and as black, and their bodies marked with scars in the same manner. But in this they differed from the men, that, though their hair was of the same colour and texture, some of them had their heads completely shorn or shaved: in others, this operation had been performed only on one side, while the rest of them had all the upper part of the head shorn close, leaving a circle of hair all round, somewhat like the tonsure of the Romish ecclesiastics. Many of the children had fine features and were thought pretty; but of the persons of the women, especially those advanced in years, a less favourable report was made. However, some of the gentlemen belonging to the Discovery, I was told, paid their addresses and made liberal offers of presents, which were rejected with great disdain, whether from a sense of virtue or the fear of displeasing the men, I shall not pretend to determine. That this gallantry was not very agreeable to the latter is certain, for an elderly man, as soon as he observed it, ordered all the women and children to retire, which they obeyed, though some of them shewed a little reluctance." *

[* Cook's Voyages.]

Such is the account given of the Aborigines by Captain Cook. The documents printed in the Appendix shew the cruel and inhuman manner in which these poor savages have been since treated, and the measures which it is now deemed necessary to adopt, in order to put a stop to their ravages, and to protect the persons and properties of settlers.

{Page 43}

Difficulties of first Settlers—Sheep, Cattle, Horses—Table of Population—Live Stuck—Acres of Land under Cultivation—Wool imported into Great Britain from Australia—Fisheries—Commerce—Gardens—Hobart Town—Launceston—Roods—Ports—Towns—Mountains.

The two difficulties with which the settlers in Van Diemen's Land have had peculiarly to contend, are the Bushrangers and the Aborigines. Another, which is common to all distant settlements, is the communication with the mother country or with others whence they could obtain supplies until they were able to cultivate their lands to produce sufficient food for their wants: the consequence was, that early settlers suffered severely from famine.

The year 1819 may be considered the period from which the colony of Van Diemen's Land has risen to consequence and wealth, but even at that time there was some stock in the island of sheep, cattle, and horses; and though free emigration had not been encouraged, various individuals had settled there, and large districts of land had been granted. A commission of enquiry was established by government in that year, in order to ascertain the actual state of the colonies of New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land, and reports were drawn up by Commissioner Bigg, and printed by order of the House of Commons in the years 1822 and 1823. These reports give the most, authentic account of the state of the infancy of the colonies when Colonel Sorell was the lieutenant-governor of Van Diemen's Land.

From these official reports it appears, that the breed of sheep was then in the lowest state. The following extract from Commissioner Bigg's Reports will best shew the nature of the flocks, and the anxious attention given to them by the lieutenant-governor.

"The breed of sheep now prevailing in Van Diemen's Land was derived from a flock imported by Colonel Paterson from New South Wales. These sheep were of the Teeswater breed, and have since received a slight admixture with the sheep of the Leicester breed and with a few that have been imported from Bengal. Of the latter there are few remaining, and the traces are nearly extinct From the access that the sheep of these settlements have had to new pasturage, they have thriven rapidly and as quickly increased in number.

"By the return made of New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land, the muster of 1818, the number of sheep is stated to have amounted to 127,883. In 1819 it is stated to have been 172,128; and by the return made to the muster 1820, the number of both settlements is stated to have amounted to 182,468.

"From the statement made by Mr. Deputy Commissary-General Hull, the returns given in at the annual muster, especially of the number of ewes, are not to be depended upon. The general embarrassment of the settlers, and the wish to swell the amount of their property, as well as to entitle themselves to a share of the supply required for the king's stores, all operate to give a delusive character to these returns. The state of the flocks will, however, in some measure account for the rapidity of their increase: it was the custom to allow the sheep of all ages and sizes to herd together in the same flock, and the lambs were allowed to breed before they had attained the age of seven months. Little improvement has taken placp either in the size or in the fleeces of the sheep of Van Diemen's Land; nor did it appear likely to take place under the management of the present proprietors and as long as their attention was devoted to the single object of supplying the stores with meat.

"Lieutenant-Governor Sorell had for some time been impressed with the necessity of making some effort to improve the value of the wool; and after communicating with Mr. M'Arthur upon the best means of effecting it, Governor Macquarrie sanctioned an agreement by which that gentleman delivered, at Sydney, 300 lambs of the improved Merino breed in exchange for a certain quantity of land in New Sooth Wales. The lambs were embarked in a large vessel that was destined for Van Diemen's Land, and every care was taken for their security and preservation during the voyage. In consequence, however, of their long detention at Sydney after their embarkation, on account of some private business of the captain and of the great number of lambs that were put on board and necessarily confined between the decks, ninety-one died on the passage, 209 were landed, and of them twenty-four died soon afterwards.

"A distribution of 181 lambs, valued at seven guineas each, took place at Hobart Town in the month of September, 1820, to the individuals whom Lieutenant-Governor Sorell considered most capable of giving attention to the improvement of their fleeces, and the number appropriated to each individual was also regulated by him, on due consideration of the application that was made to him and the character of the applicants. Securities were likewise given from each person for the repayment of the value of the lambs thus distributed, and amounted to £1330 7s. 8d." * This may be considered the commencement of attempts to improve the fleeces in Van Diemen's Land, and to make the growth of wool important.

[* Bigg[e]'s Report, January 10, 1823.]

It is stated in Commissioner Bigg's Report that the breed of cattle prevalent in Van Diemen's Land, was derived from an admixture of the Bengal and the English breeds.

The ordinary weight of the cattle at three years old was about 470 pounds: they were much used for draught and all agricultural purposes. The number of cattle returned at the muster 1820. amounted to 28,838.

The number of horses was not stated in that report; but the deputy surveyor, Evans, states the number in that year to have been 411.

The land cultivated for wheat in 1820 appeared to be 9275 acres.

| In 1820 Hobart Town contained | 1 | house with three Stories. |

| 20 | houses with two Stories. | |

| 72 | do. with ground floor. | |

| 10 | out-houses. | |

| ——— | ||

| 103 | total. | |

| ——— | ||

| Launceston contained | 78 | houses. |

Having thus shewn what Van Diemen's Land was in 1820, by reference to the maps of the island hereto annexed, just published by Mr. Arrowsmith, and the following statistical tables, the proprietor will see the rapid advance made in the island, and the progress towards more extended cultivation. In this table the population and stock of the Van Diemen's Land Company is not included, as it appears in the annual report.

The whole white population in the island, including convicts in the prisoners' hulk and in chain gangs, is estimated at 20,735.

The number of the Aborigines is uncertain, but is estimated at 500.

The foregoing tables are formed from information contained in the Van Diemen's Land Anniversary and Hobart Town Almanack for the year 1831.

The chief article of exportation, in Value, from Van Diemen's Land is wool; the rapid increase in the quantity produced, together with the equally rapid improvement in the quality of the fleece,-must make that article the most important and, properly speaking, the staple commodity of the colony. Its growing importance to our manufacturers at home is equally great, the felting properties superior to the wool of other countries, and the peculiar softness of the texture make it very valuable to the cloth manufacturers, while the length of staple, combined with that softness, makes the heavier fleeces peculiarly adapted for the fabrics made from fine worsted. Every year adds to the value which the Australian colonies become to the mother country; and when it is considered, that a few merino sheep were introduced from Spain into Germany in the year 1780, and that wool was first imported from thence in 1809, it may be fairly estimated, that in the course of a few years we shall get our supplies of wool altogether from British soil. The following Table shews the rapid increase of importation, both from New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land.

Official Return of Quantities of Sheep's and Lamb's Wool, imported into Great Britain from New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land, in each Year since 1821, shews its rapid Increase from both Colonies, but particularly from Van Diemen's Land:

| Year. | Quantities imported from

New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land. |

|

| lbs. | ||

| 1821 | 175,433 | |

| 1822 | 138,498 | |

| 1823 | 477,261 | |

| 1824 | 382,907 | |

| 1825 | 323,995 | |

| 1826 | 1,106,302 | |

| New South Wales. |

Van Diemen's Land. |

|

| lbs. | lbs. | |

| 1827 | 320,683 | 192,075 |

| 1828 | 967,814 | 528,845 |

| 1829 | 913,322 | 925,320 |

| 1830 | 973,330 | 993,979 |

| 1831 | 1,134,134 | 1,359,203 |

The next article of importance to the commerce of Van Diemen's Land is oil. The following extracts give much information upon that and other productions.

"The sperm whale abounds in the Australian seas, particularly in Bass's Straits, the oil of which fetches a high price in the English market; and it must be evident to every one, that if the merchants of London find it to their advantage to equip vessels there at a very heavy expense for such a distant speculation as a three years' voyage to the southern fishery, how much more profitable it would be for the mercantile people of Van Diemen's Land to enter into the trade, when they have the fish at their very doors? There would be no necessity for the ships keeping the sea so long to their great detriment, as they would have a port at hand to which they might resort, and there deposit their oil, refit, and take in fresh supplies. The capital required would also be much less, from the smaller size of the vessels, and the return being so much quicker, a ready sale being found on the spot, should the adventurer not be able to wait even so long as to send it to the English market. Having a valuable article to offer in return for these imports, and furnishing freight to vessels which are now obliged to go elsewhere in ballast to seek it, would tend much to increase the trade of the colony by attracting vessels, and to the benefit of the settlers by reducing the prices of articles from the greater importation caused by it.

"The whale which yields the black oil is extremely numerous all round the island, coming up even into the harbour, where the inhabitants may witness the animating spectacle of these huge monsters killed by the boats' crews belonging to the port One female went up as far as New Norfolk, twenty-four miles above Hobart Town, it is supposed for the purpose of calving, and was killed there.

"Seals are very numerous on the coasts and islands, and their skins are sent to England. No use whatever is made of the oil which this animal yields so abundantly, the carcases being generally left to rot by the fishermen. The skins of kangaroos and other animals, such as those of the opossum, tiger-cat, and platthypus, or ornythorhyncus * paradoxus, are exported, but in such trifling quantities as to be scarcely worth mentioning. The skin of the kangaroo answers, as well as kid skins, for the upper leathers of shoes, and is of a very soft, pleasant wear. Till lately, scarcely any attention was paid to the hides of the cattle that were slaughtered out of the towns; and even now very little care is bestowed upon them. Great quantities are consumed by the settlers themselves in making a rude sort of rope, by cutting the hide up into strips; and what are not so used, are generally thrown aside to rot. The curing of hides, and salting of beef for exportation are very worthy of attention on the part of the settlers. The herds of cattle are increasing so rapidly, and in many places are allowed to stray so much at large over the country, as to be almost valueless to the proprietors: it would be worth their while to slaughter very extensively, for the purposes mentioned. Few attempts have been made to salt beef for exportation; but were it properly done, India, the Mauritius, (and Swan River for some time,) would afford an extensive market, in supplying the navy and merchantmen. The latter generally bring a sufficiency of salt provisions for the voyage out and home; but were they sure of obtaining them good in India, it cannot be doubted but that they would be glad to avail themselves of the additional quantity of room, obtainable by only taking enough for their outward voyage. Some trials, in a small way, have been made in salting beef, which did not stand the changes of climate. There can be no doubt but that this must have arisen either from the method of curing pursued in England not being properly understood in the colony, or from the nature of the salt made use of. There is nothing in the climate to prevent meat being cured just as well as in any part of the world. Hams and bacon are cured in considerable quantities; and were proper attention paid to the English methods of doing it, they ought to furnish a considerable article for export to India, as well as cheese, the making of which is beginning to be more attended to in this colony.

[* The ornythorhynchi appear to blend several of the characters of the quadruped and the bird, and in one of the species even of the fish; they are four footed animals about twenty inches long, terminating at the head in a bill like that of a duck, and at the other end in a tail not unlike that of a seal.]

"The corn of Van Diemen's Land is particularly fine and heavy. Large quantities are exported annually to Sydney; and a few trials have been made of sending it, as also flour, to the Isle of France, where they have sold very well. Barley grows very luxuriantly; but from the little pains hitherto bestowed in keeping the seed free from admixture of other grains, it cannot be extensively used in brewing of malt liquor; to which, probably, may be attributed the slow progress in this branch of trade, as the brewers are obliged to purchase foreign barley at a high price. There are, however, five breweries established in Hobart Town, producing very good beer and ale. Imported hops are made use of at present; but attention is given to the growth of this very necessary article, to the raising of which the climate is found extremely favourable. It is to be hoped that at some no very distant period, beer may also afford an export to our Indian settlements, to which the voyage from hence is so much shorter than from England. The distance is now performed in two months, even in winter; and as the usual state of the winds, &c. become better known, it will, no doubt, be done in less time. There is but one distillery now at work in the island.

"The bark of the mimosa, or, as it is called in the colony 'the wattle tree' is found to answer extremely well in tanning leather, and to yield a very powerful extract for the same purpose. Of the latter not much is made, but great quantities of the bark are sent to England, the character of it becoming better understood. A small portion of the extract was also sent; but from ignorance of the mode of manufacture, it was boiled in iron vessels; so that, although of very great strength, it did not answer, from its imparting a colour to the leather and rendering it brittle. Time and experience will enable the colonists to manufacture it in a proper manner.

"Leather is tanned to a considerable extent in various places, and a great deal is consumed in the making of shoes, which are found very durable. A good deal of glue and parchment is also made. Hats are manufactured in Hobart Town; they have not, however, so good tax appearance as those sent from England.

"There is a considerable manufactory of salt in Brune's Island; but a great deal is still imported from England.

"The demand for soap is largely supplied by the manufactory of this article in Hobart Town. The barilla used is found on the islands in Bass's Straits, and the eastern coast of the island; and some little of the last-mentioned produce has been exported. It only requires command of labour and capital to develops the great resources which the island possesses within itself." *

[* An Account of Van Diemen's Land, printed at Calcutta.]

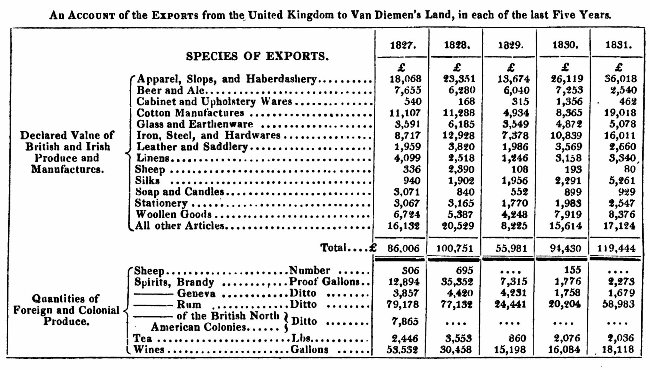

The above extracts shew the capabilities of Van Diemen's Land for general trade; considerable commerce has been carried on with the East Indies, the Mauritius, New South Wales, and the Brazil; the most important is, however, with the mother country, and the following, official Table of the quantities of the principal articles imported from thence, and the Table of the declared value of British and Irish produce and manufactures, together with the quantities of foreign and colonial produce exported in the last five years, viz. the years 1827, 1828, 1829, 1830, and 1831, shew the growing importance of the trade with Van Diemen's Land, as well as respects the raw materials imported from thence, so essential to our national industry, as the increasing demand for our manufactures. It is indeed to our own colonies and to distant markets that the British merchant must look for the consumption of the chief fabrics of Great Britain, the demand for which will be reduced by the extension of manufactures on the continent of Europe.

An Account of the Quantities of the principal Articles Imported into the United Kingdom from Van Diemen's Land, during the last five years.

An Account of the Exports from the United Kingdom to Van Diemen's Land, in each of the last Five Years.

[Click on the table to enlarge it.]