a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

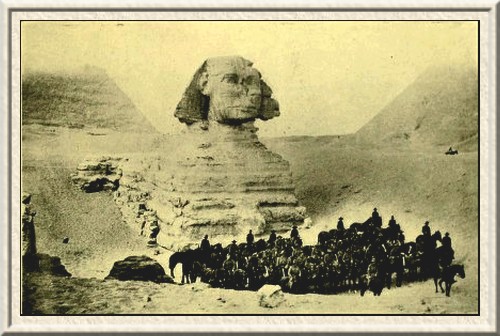

Title: Kitchener's Army Author: Edgar Wallace * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1400171h.html Language: English Date first posted: Jan 2014 Most recent update: Jan 2014 This eBook was produced by Roy Glashan. Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Cover of first book edition

Hark! I hear the tramp of thousand!

And of armed men the hum;

Lo! a nation's hosts have gathered

Round the quick alarming drum

Saying, "Come,

Freemen, come!

Ere your heritage be wasted," said the quick alarming drum.

"Let me of my heart take counsel:

War is not of Life the sum;

Who shall stay and reap the harvest

When the autumn days shall come?"

But the drum

Echoed, "Come!

Death shall reap the braver harvest," said the solemn-sounding drum.

"What if, 'mid the battle's thunder.

Whistling shot and bursting bomb,

When my brothers fall around me,

Should my heart grow cold and numb?"

But the drum

Answered "Come!

Better there in death united than in life a recreant—come!"

Thus they answered hoping, fearing,

Some in faith, and doubting some.

Till a trumpet-voice, proclaiming

Said, "My chosen people, come!"

Then the drum,

Lo! was dumb.

For the great heart of the nation, throbbing, answered, "Lord, we

come!"

—Bret Harte

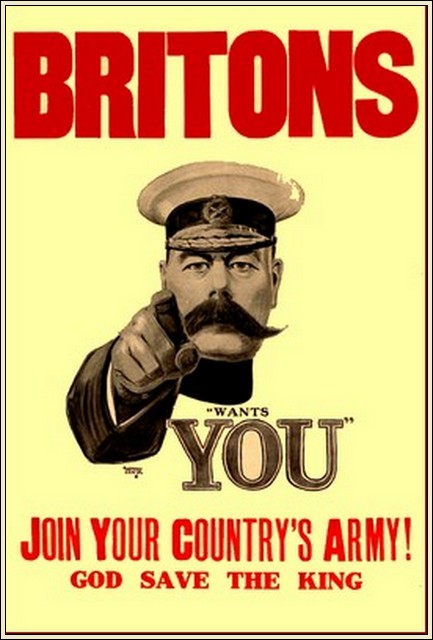

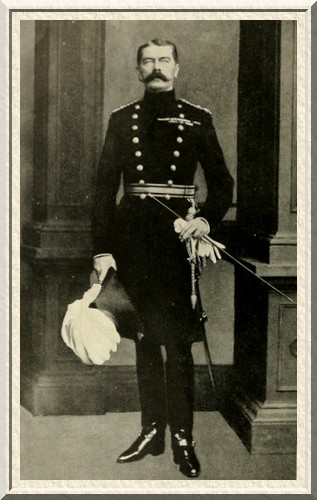

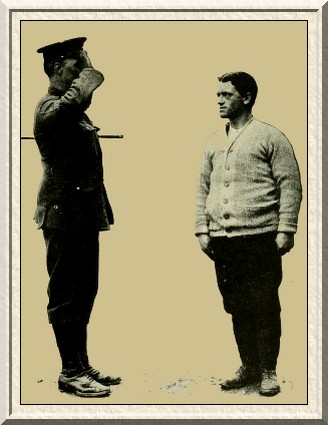

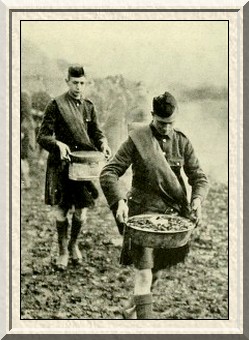

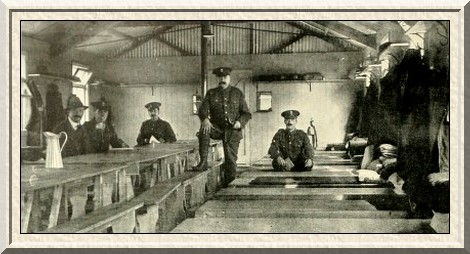

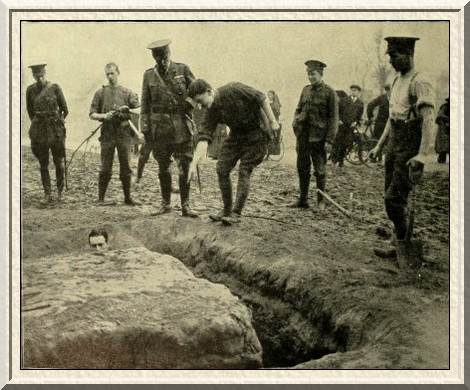

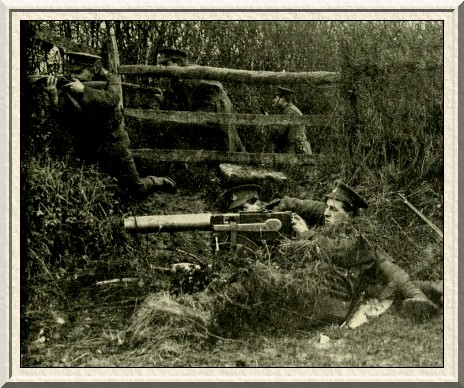

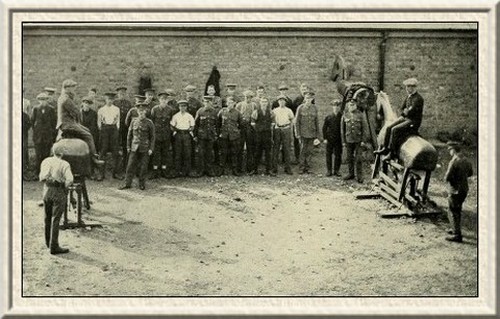

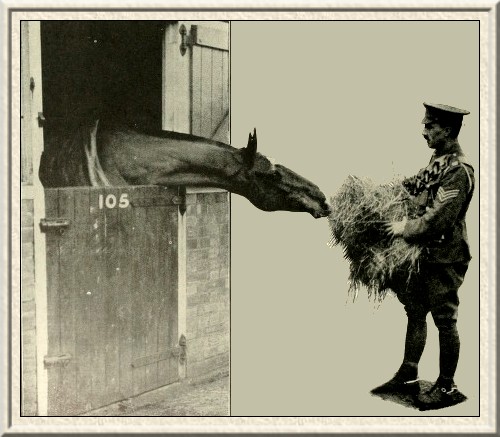

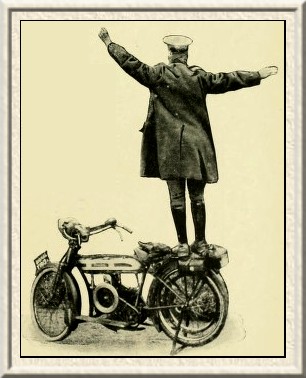

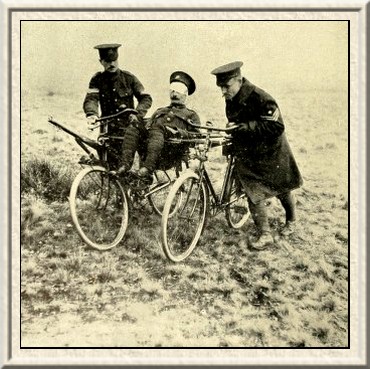

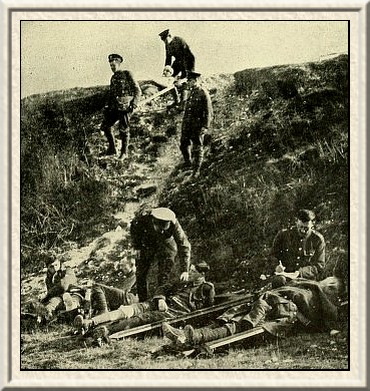

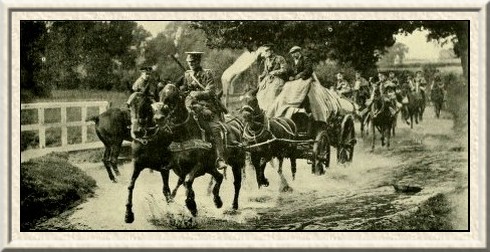

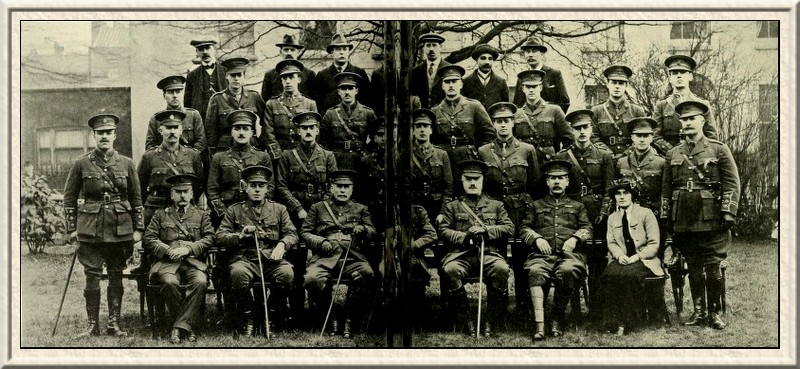

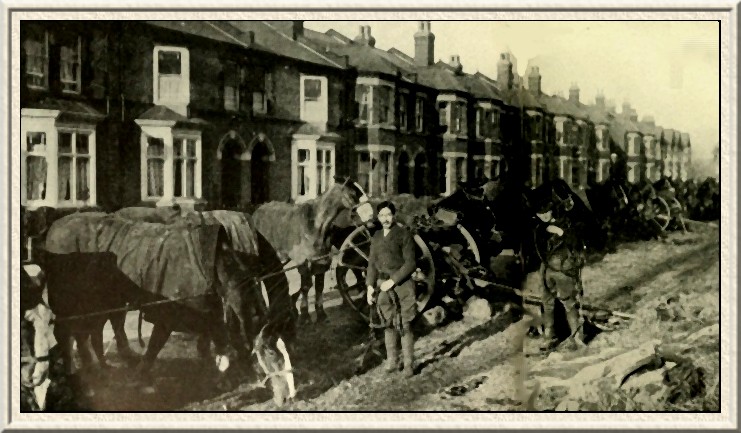

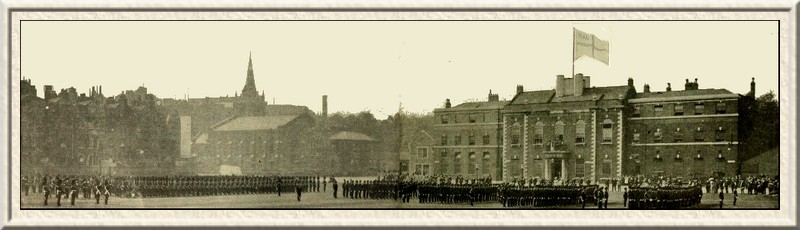

—Photograph 1—

Abundantly satisfied with the army he created.

Earl Kitchener of Khartum.

"KITCHENER'S ARMY!" a phrase which may well stand for a hundred years, and, indeed, may stand for all time as a sign and symbol of British determination to rise to a great occasion and to supply the needs of a great emergency. It is not my task here to discuss the military situation as it might have been, or to offer arguments for or against national service, nor yet to say whether the recruitment of the first few months of the war disposes of or makes inevitable a system of compulsory service. The purpose of this volume is to place on record in a permanent form a chapter of Britain's history of which the people of all ages who call these islands their home may indeed be proud.

The outbreak of war found all the nations concerned unprepared save one. Germany alone, which had been preparing, scheming, and planning for the day on which it would be at war, was ready in every department to the last button on the last service tunic. Germany, with huge reserves of men and stores and warlike material, swept resistlessly down through Belgium and secured for herself a momentary and, as it was thought at the time, an unchallengeable advantage. Russia was not ready, France was not ready, and most certainly Great Britain was not ready to deal with the huge numbers and the great masses which were instantly directed against the Allies.

At the time when the British Army was mobilising in England, and when Russia had no more than 300,000 men on the scene of action, Germany had concentrated forty-four Army Corps, divided into nine Armies,the smallest of which, under General von Deimling, was charged with the task of keeping strictly on the defensive behind the Vosges. The rest of this enormous mass was concentrated between Aix-la-Chapelle and Strasburg, and the eight Armies which were equipped and in the field days, indeed weeks, in advance of some of the Allies were, reading from right to left (that is to say, from north to south), the first army under von Kluck, the second under von Buelow, the third under von Hausen, the fourth under the Duke of Wurtemburg, the fifth under the Crown Prince of Prussia, the sixth under the Crown Prince of Bavaria, the seventh under von Heeringen, and the eighth army, which was merely temporarily formed, was known as the Army of the Meuse and was under von Emmich.

Von Emmich's Army was immediately ready for service the moment war was declared, and stationed, as it had been before the outbreak, a short distance from the Belgian frontier, it had during the later days of July been brought up to war strength by the secret additions of reserves, who had been personally notified and had been charged to keep their notification to themselves.

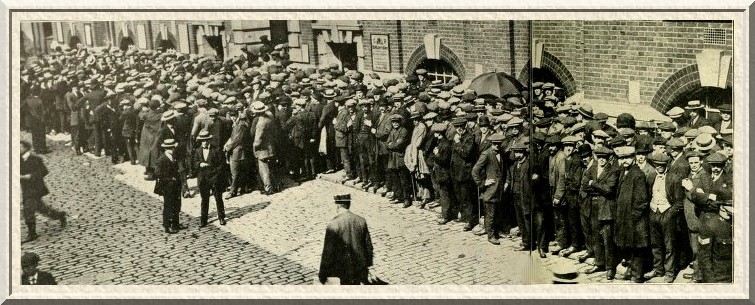

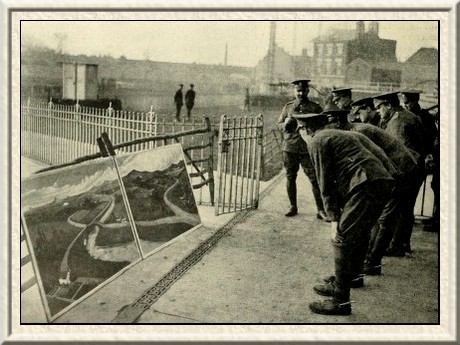

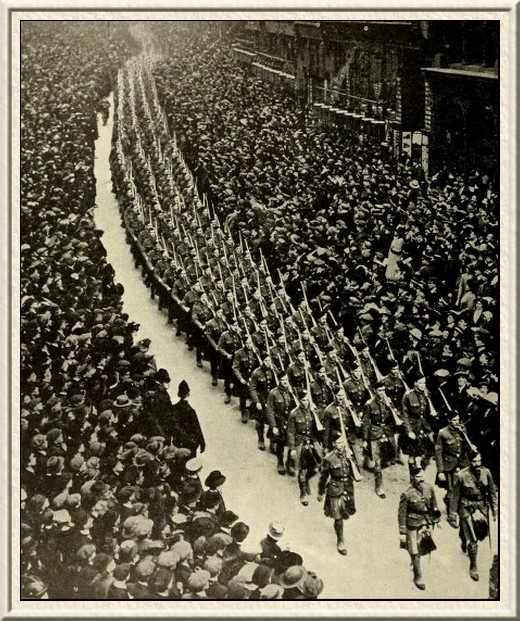

—Photograph 2— Lord Kitchener's appeal for recruits met instantaneous response from hundreds of thousands of Britain's sons. The photograph shows the Whitehall Recruiting Depot besieged by men eager to serve their country.

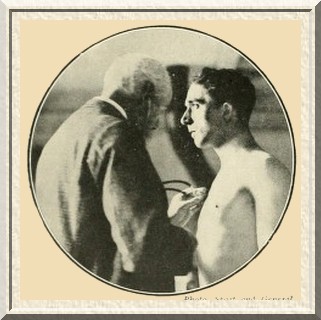

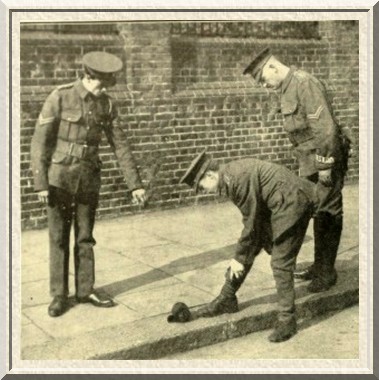

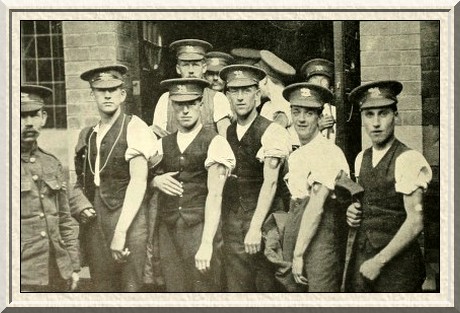

—Photograph 3— Before a recruit can be accepted he has to pass a very thorough medical examination.

The British Army Expeditionary Force, which immediately mobilised on the outbreak of war, was roughly 160,000 officers and men; but only a very small proportion of these was ready for war. When the Germans swept down through Belgium they found themselves opposed at Mons to two Army Corps only (80,000 men), which later at Le Cateau, were reinforced by a division, and were still further augmented in the early part of September by another Army Corps. Large as was this force from the point of view of a nation which has never engaged more than 160,000 men in any one battle formation since the wars of the Middle Ages, it was insignificant by the side of the great armies which were gathering on the Continent. A little table showing the comparitive sizes of the armies is instructive.

| Nation | Peace Footing | War Footing | No. of Guns |

| Austria | 500,000 | 2,200,000 | 2,500 |

| France (incl. Algerian Troops) | 790,000 | 4,000,000 | 4,200 |

| Great Britain | 234,000 | 380,000 | 1,000 |

| Germany | 850,000 | 6,000,000 | 5,500 |

| Russia | 1,700,000 | 7,000,000 | 6,000 |

As will be seen by the above table, the only advantage—and it was merely a relative advantage—which Great Britain possessed was the larger proportion of guns she had to the number of men under arms, but this advantage is neutralised by the fact that the Indian Native Army, which is not included in this table, possess no guns at all, and depend for their artillery upon the British Army. So whilst at first it seems that we have one gun to every 380 men, if we put in the 200,000 Indian native troops serving, the proportion is reduced to one in 580.

It may be said, and, indeed, has been said, that Great Britain, from the insularity of her position and the protection which her huge Navy and her narrow seas afford her, is not so greatly in need of an Army as was either of her great rivals, who have huge frontier lines to protect and must needs depend upon seas of armed humanity to protect their great industrial districts and their strategic positions.

This was largely true; but equally true was it that great armies have functions to fulfil other than the actual winning of battles. It was evident from the beginning that this war could only end when the whole of the map of Europe had been changed, when frontiers had been readjusted and territories acquired or lost by the belligerent Powers, and it was just as evident that, great as might be the influence which a naval Power might exercise in the course of the war, the settlement and the terms of peace would be dictated by the possessors of large land forces. It was evident, too, from the many signs which Germany gave us that she had aimed for many years to secure a world domination, and to impose her will upon the peoples of the earth. Necessarily, Great Britain, of all the countries in the world, stood in the way of her ambitious scheme, and, as inevitably, Germany had planned the overthrow of this country. Britain, however, could only be overthrown by a sequence of circumstances. The first was that she should not intrude herself in this war, but that she should leave Germany and Austria to finish their great antagonists, and establish themselves in Belgium and upon the North Sea, so that at the triumphant end of the war Germany should have a naval base from which she could in course of time operate against her great sea rival. It was evident, therefore, that to make her Navy doubly effective, it was necessary to destroy the enemy's land power.

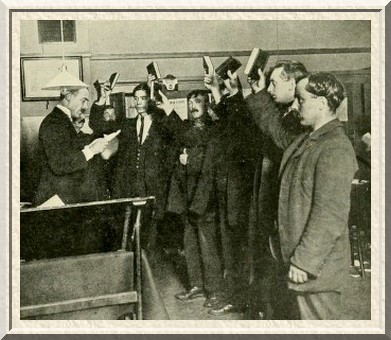

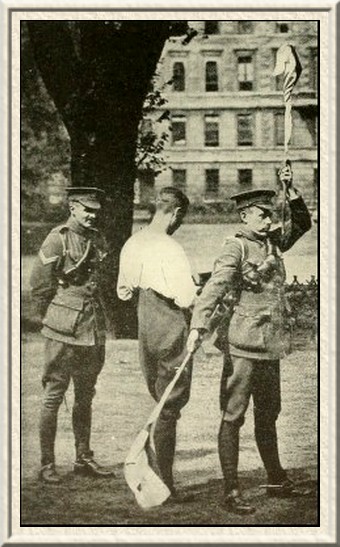

—Photograph 4— Recruits taking the oath at the Central Recuiting Depot, Whitehall.

Events did not turn out as Germany anticipated; and though, by her lightning mobilisation and the rapidity of her march past, she succeeded in obtaining initial successes and those with great loss she quickly found her advantages nullified by new and menacing forces which were rapidly coming into existence against her. Undoubtedly the greatest of these forces was the creation in Britain of a most unexpected Army. It denotes the machine-made character of German thought that our enemy did not believe in the existence of that Army, palpable as it was, until he received evidence of its excellence and its numbers on the field of battle.

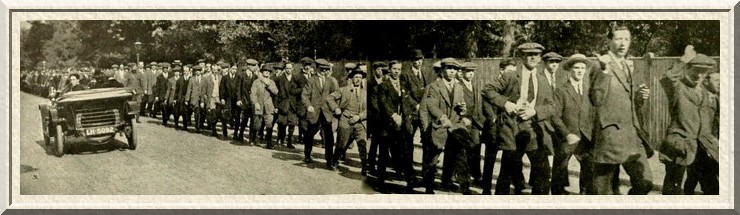

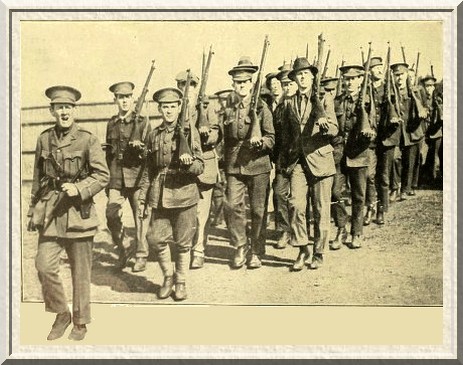

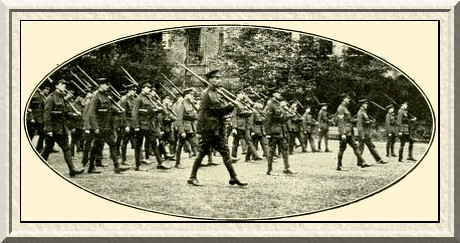

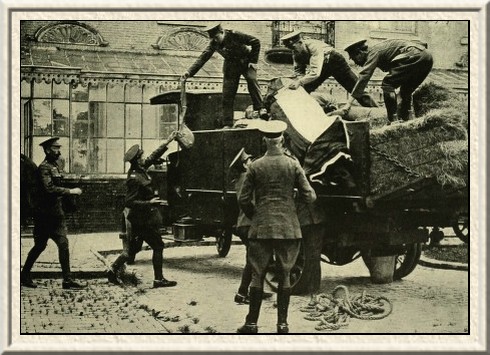

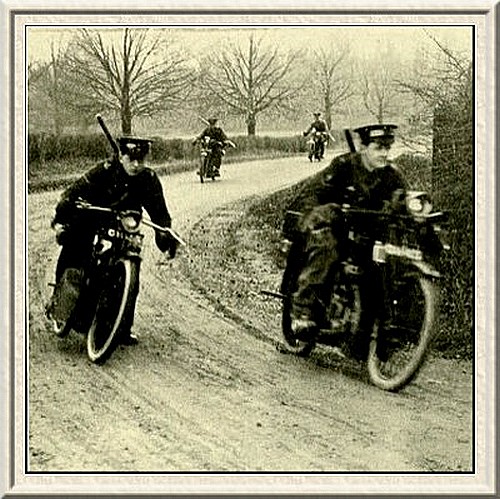

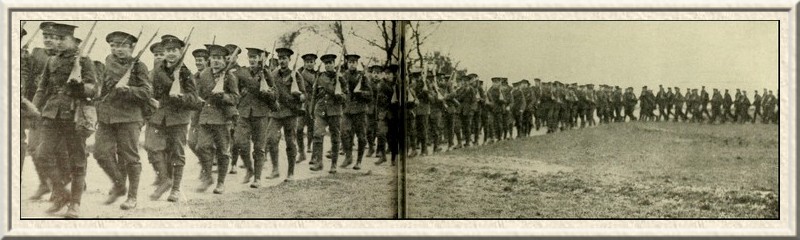

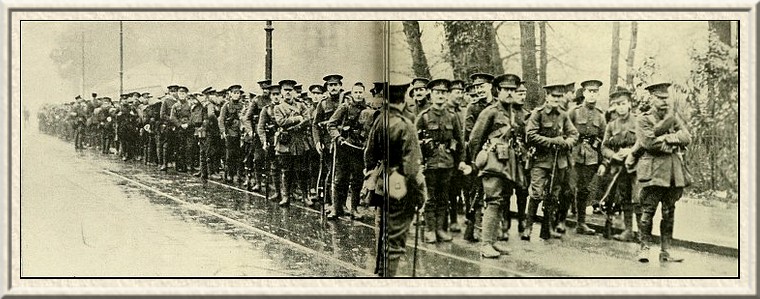

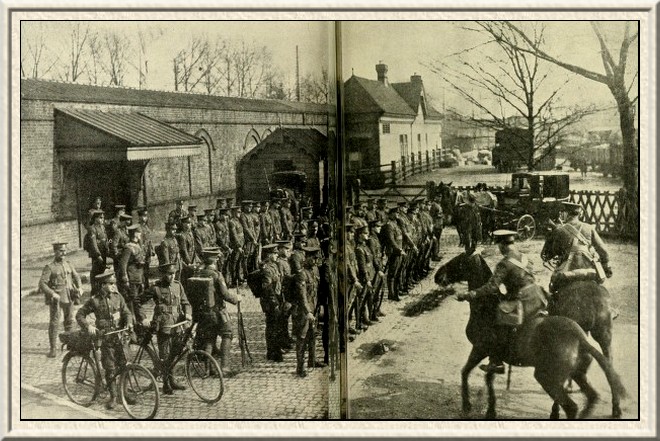

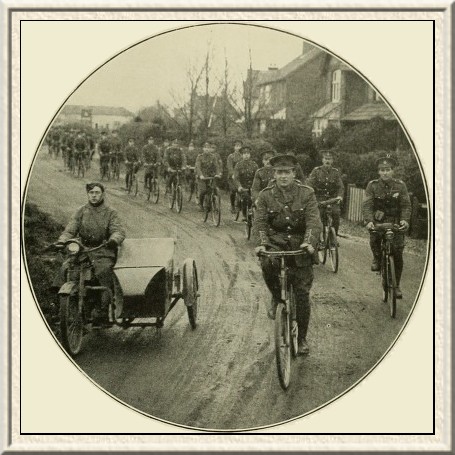

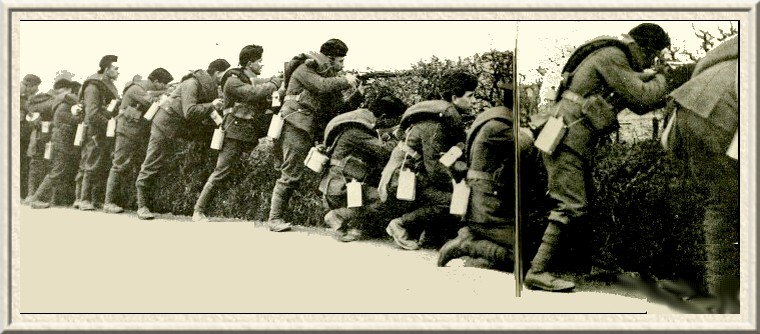

—Photograph 5— Recruits on their way from the recruitment offices to their training camps.

I have related all the circumstances which were responsible for the beginning of Kitchener's Army, and it only remains to add one very important fact, that the reader may appreciate to the full, the extraordinary accomplishment of those entrusted with the conduct of Great Britain's military affairs. To say that Great Britain was unprepared for this great war is to say that, whilst she was ready to believe that Germany, France, Russia, and Austria would some day or other be involved in a world conflict, she did not anticipate that she would be called upon to enter that field, or be asked or expected to organise great military forces to combat Prussian militarism upon land.She did not, indeed, realise that such a conflict could not be waged without Britain's power and Britain's place amongst the Powers being challenged, not only by one section of the belligerents, but by all.

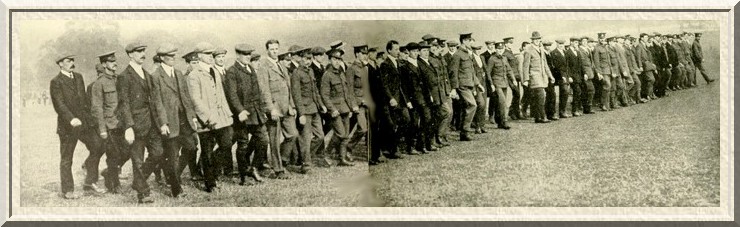

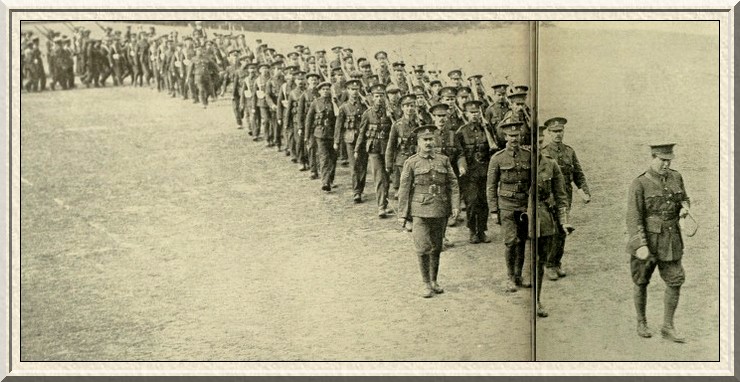

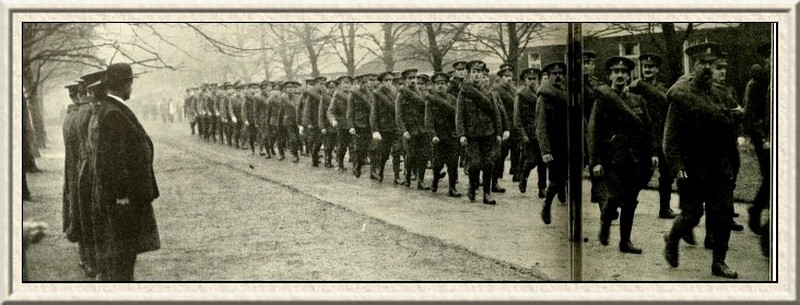

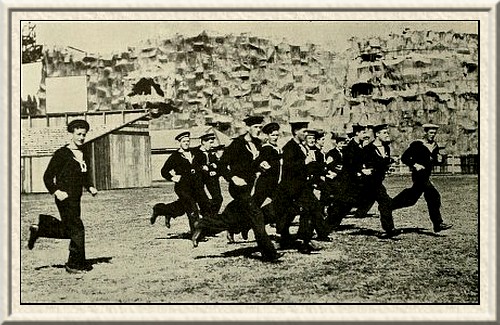

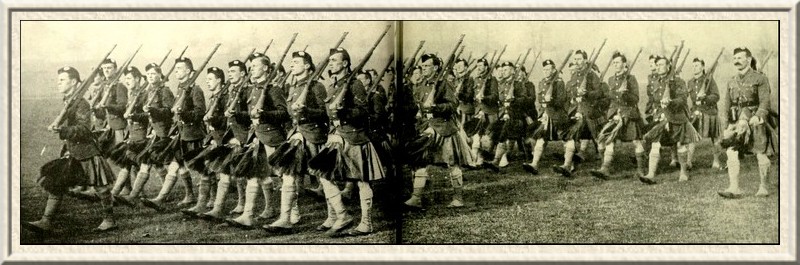

—Photograph 6— "H" Company of the Post Office Regiment marching in company formation in Regent's Park.

I have referred to the unreadiness of Great Britain to participate in so huge a conflict as that which raged through Europe in the summer and autumn of 1914, and by that I do not mean that our men were ill-trained or ill-equipped. All that is meant is that, while we had the clothing and equipment, arms and ammunition, guns and horses to furnish the British Army and its reserves, we had not supplies for larger forces than the number set down as Britain's normal war strength.

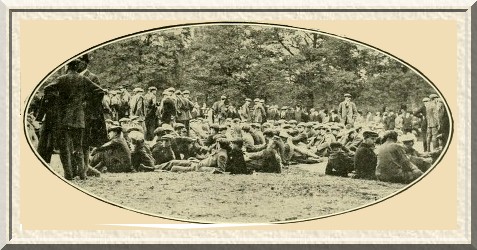

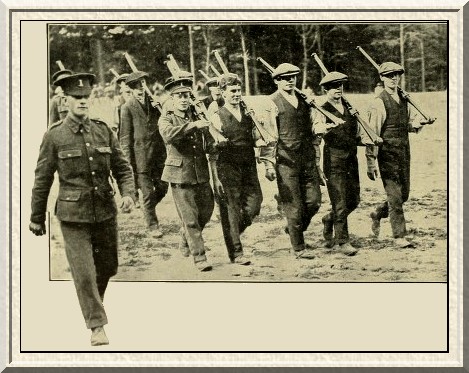

—Photograph 7— Raw recruits training in Kennington Park.

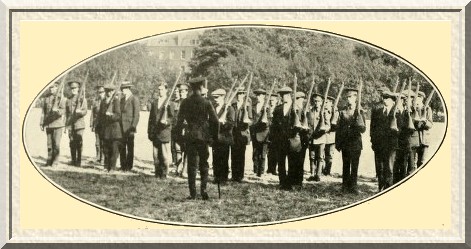

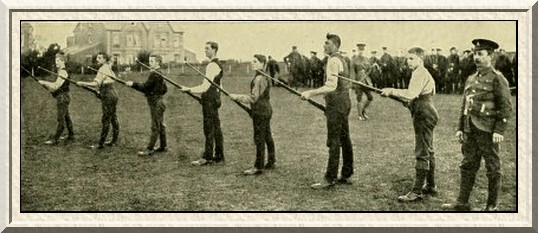

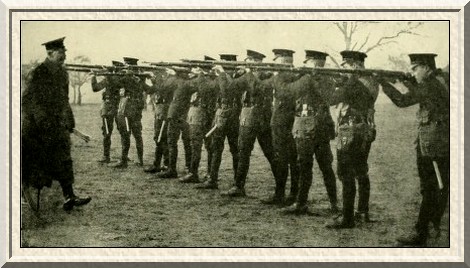

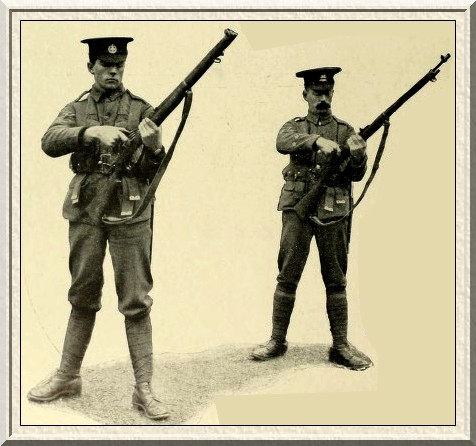

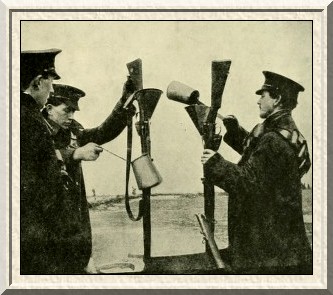

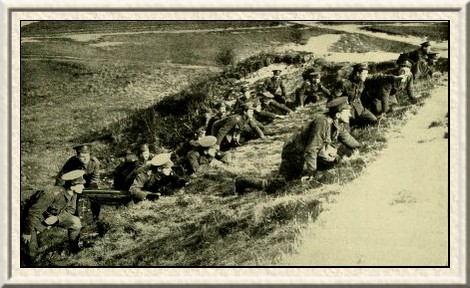

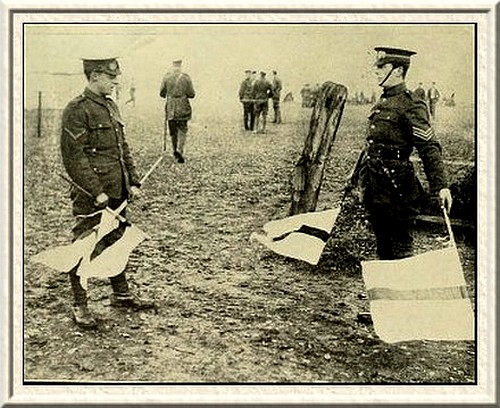

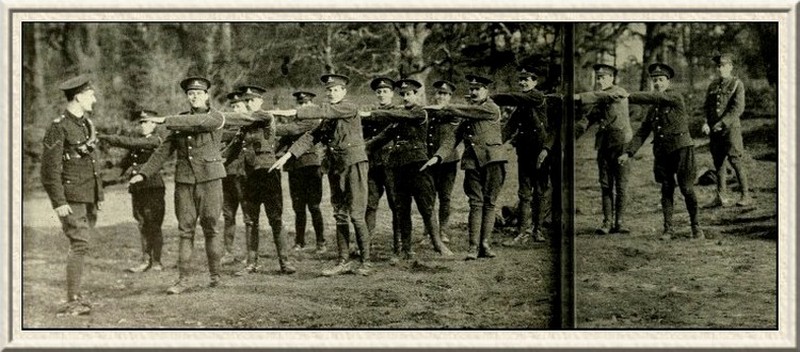

—Photograph 8— Recruits of the Lincolnshire Regiment being instructed in the use of the rifle.

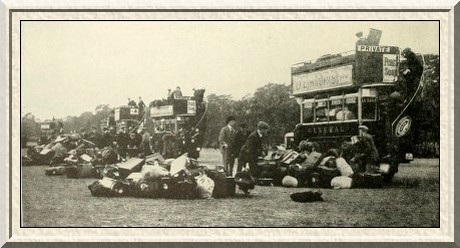

—Photograph 9— Men of the Public Schools Boys' Corps waiting to leave Hyde Park for their camp at Epson.

The task the Government set itself was a formidable, nay, a staggering one. It was in the first place to take 500,000 raw men from the streets, from the clubs, from the fields, from the villages, towns, and cities of Great Britain, and not only to train them in the art of war in the shortest space of time that it is possible to train soldiers, but also to prepare the equipment, the arms, and the munitions and stores of war. And so Kitchener's Army came into existence with a rush. It came into existence in the crowded streets of the great cities, in the peaceful villages up and down England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, where men came forth from office, warehouse, and factory, or tramped from their farms and their cottages to the nearest recruiting office; it came into existence on the decks of homeward bound steamers, where little côteries of young men, eager and enthusiastic, returning to their Motherland to give their services, had already joined themselves into parties for enlistment in certain regiments.

An observer watching the animated scene before one of the greatest recruiting centres of London in the early part of August might have witnessed a strange sight—a policeman grasping firmly the arm of a flushed and smiling young man, and leading him gently down the road, past his jeering companions to a point a quarter of a mile from the place whence he had been taken. For this young man had, with great temerity, dared to insinuate himself at the wrong end of the long queue which was waiting its turn to parade before the medical officer and to be examined that its fitness for army service might be certified. This young man could complain, as he did, that he had already been waiting for six hours, that he had journeyed from Canada at the first hint of war, and that he was most anxious to begin working at his new profession as soon as it was possible; but the unanswerable retort was that he was only one of thousands, and that the recruiting authorities were quite unable to cope with the rush of men which had followed the demand of Lord Kitchener and the Prime Minister for the first 100,000 men. The machinery of the peacetime recruiting office was not designed to pass thousands of men a day. To pass, as it did, a larger number of recruits for the Army in twenty-four hours than that particular office had passed in a year in normal times was an achievement in itself. In justice to the Chief Recruiting Officer, it cannot be said that his system broke down, but rather that it could not be accelerated beyond a certain speed; and recognising this, the Government established offices, not only in the principal centres of all the great towns of England, but in the outlying suburbs and in the villages and market towns which were accessible to would-be recruits. They came in such huge numbers it impossible to deal expeditiously with them as masses, though the actual examination and swearing-in of individuals proceeded as rapidly as humanly possible, but it was likewise impossible for a long time to house, clothe, and equip these huge numbers, which grew in size every day.

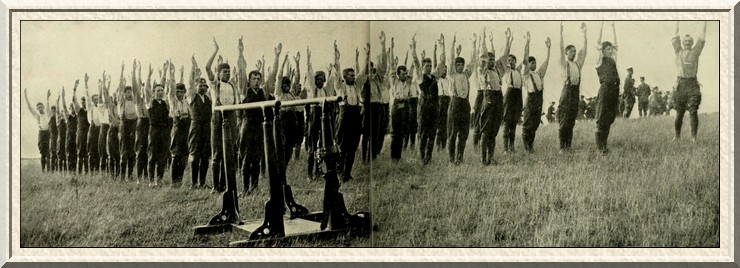

—Photograph 10— Swedish drill in the open. The Queen Victoria's Rifles training at Hampstead.

—Photograph 11— Another exercise of the London Regiment, the Queen Victoria's Rifles, at Hampstead.

We may imagine our recruit, patiently and cheerfully forming one of the long queue outside the chief recruiting office, shuffling forward at a snail's pace as the queue moved up, and as the men, in parties of six and seven, were released to the medical inspection room, reaching at last the long-desired portal and finding himself ushered brusquely into a large, square apartment, equipped with a weighing machine, a scale for measuring height, a wash-bowl for the medical officer's hands, and two tables, at one of which sat a clerk busily filling up t h e attestation forms, containing particulars of the recruit's physical appearance, his trade, relatives, and measurements.

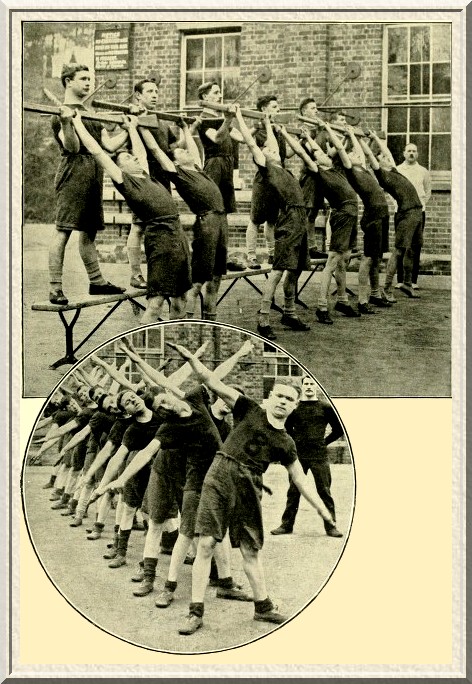

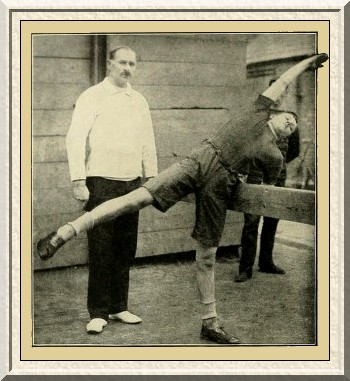

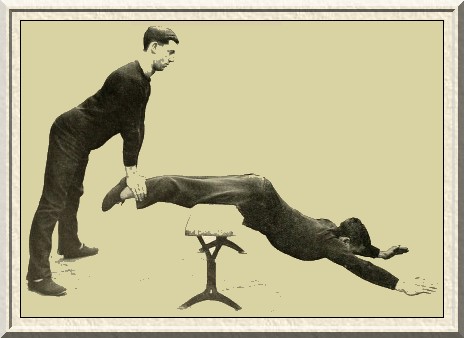

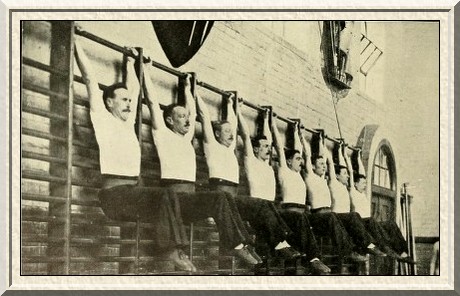

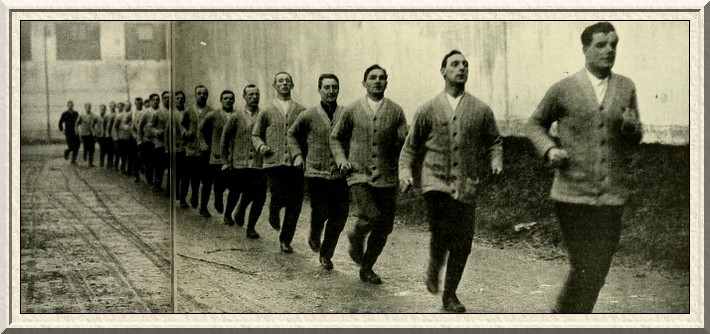

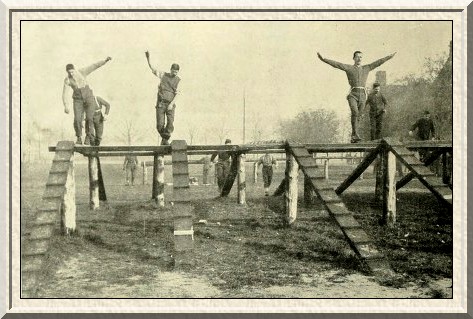

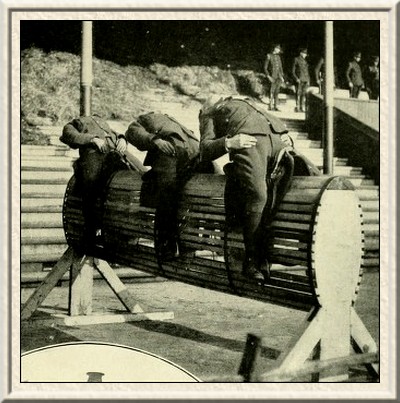

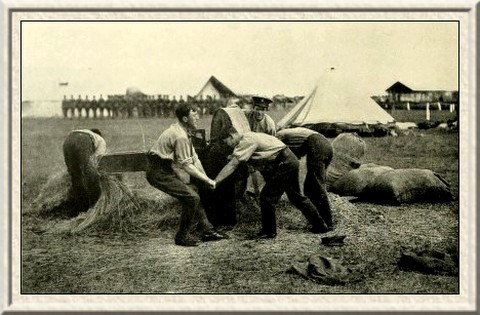

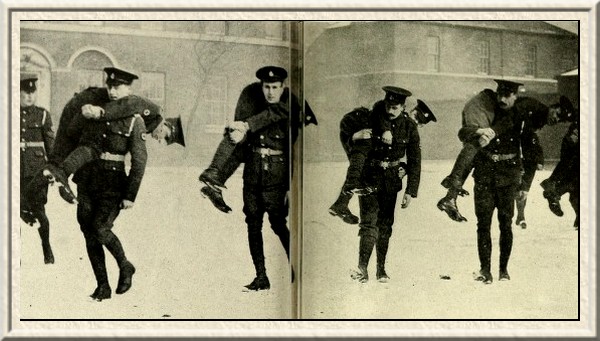

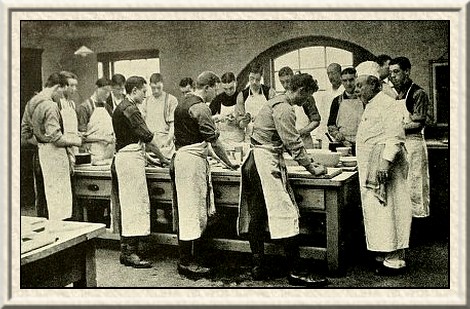

—Photographs 12 & 13— Developing the recruits' physique. The photographs show a squad of future gymnasium instructors for Kitchener's Army undergoing their training at the gymnasium, Aldershot.

In a few moments the would-be recruit is standing erect in nature's uniform. The examination is brief but thorough. Heart and lungs are tested by stethoscope and by judicious tapping. His chest is measured and his exact weight recorded. The recruit hops across the bare room, first on one leg and then on the other. His teeth are inspected, and then comes the crucial test of eyesight. A small card, containing a number of letters in various types, is placed on the wall opposite him, and he is asked to tell, first with one eye and then with the other, not only the names of the letters indicated, but he is also required to distinguish certain dots, their number, and their formation. A quick examination follows for varicose veins and other infirmities, and then with a curt nod he is dismissed to his clothing. The Medical Officer signs the attestation form, and the recruit is hurried into another room where half-a-dozen men who have also passed the medical officer are waiting their turn.

—Photograph 14— Non-commissioned officers of the new army undergoing training at the Headquarters' gymnasium, Aldershot.

"Swearing-In"

Presently the recruiting officer enters from his office, accompanied by an orderly, who distributes a number of New Testaments to the waiting recruits, who take them shyly or with that evidence of embarrassment which comes to self-conscious people who are doing unaccustomed things.

"Take the book in your right hand. You swear say after me, 'I swear."

"I swear," repeats the recruit.

"To serve His Majesty the King."

"To serve His Majesty the King," says the recruit, and the oath proceeds

"His heirs and successors... and the generals and officers set over me by His Majesty the King, his heirs and successors, so help me God!"

The book is kissed, and the raw civilian who came into the building on one side goes out at the other a member of the great army which is forming and part and parcel of that brotherhood of arms which "binds the brave of all the earth." He may have asked to be enlisted for some special regiment, and in the beginning, when the War Office called for recruits, it gave a number of friends who cared to come together the privilege of serving together in any regiment they chose, or, if they had no particular choice, in any regiment which the War Office desired to fill.

This was the very beginning. The long, waiting queues, the interested lookers-on, the hurry and rush of the recruiting office, the bustle and seeming indifference of the great city—this is the atmosphere in which the first Kitchener soldiers came to the Army. The broad doorway of the chief recruiting office was the gate to a land of strange and tragic adventure and it was with a light heart and a high hope that the young men of Great Britain passed through to the wonderful land beyond.

That was what one witnessed on the Thames Embankment in the heart of London; it was likewise seen in every great town and every small town throughout the kingdom. Birmingham, Manchester, Newcastle, Cardiff all the great industrial and manufacturing centres, no less than the smaller towns, established or enlarged their recruiting offices and daily sent their quota of new young soldiers to the depots. I shall have something to say later with reference to the wonderful organisation of these depots, and the way the rush of recruits was received, sorted out, and distributed over the country to various centres. It was all done on a well-organised plan, on lines in operation in ordinary times of peace. The civilian reader knows little or nothing of these matters. But I hope to make it clear to him what a marvellous achievement the collection, handling, and distributing of these crowding thousands was in reality. The military authorities had to deal with something they had probably never anticipated in their lifetime. They rose to the greatest emergency in our history.

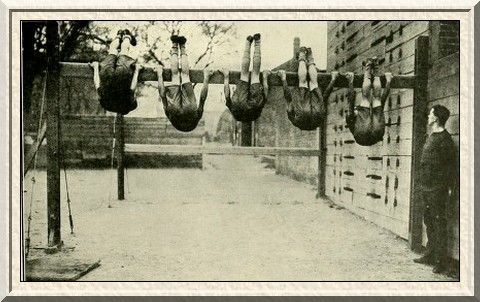

—Photograph 15— Under competent instructors Kitchener's recruits are taught many splendid exercises for the strengthening of the muscles.

—Photograph 16— A stretching position during physical exercises.

In the last weeks of August, Mr. Asquith in the House of Commons announced that the Government would ask for credit which would enable the new War Minister, Lord Kitchener, to raise a new army of 500,000 men. This was followed at a later date by the announcement that the first 500,000 would be supplemented by a second half-million. With that announcement began the formation of the Kitchener masses.

One million men! It was an extraordinary number to the Britisher, who never thought in hundreds of thousands. Men who had been discussing this grave and curious matter wherever they met together in railway trains, in the streets, in clubs, in the intervals between the acts at the theatre, asked one another the same question: "Where are we going to get them from?"

The upper and lower middle classes had come to regard the soldier as an individual who was exclusively recruited from certain social strata, just as he regarded wheat as a peculiar and necessary cereal which grew in the fields as a matter of natural course, and with the cultivation of which he himself was not immediately concerned. Volunteering and the Territorial movement he understood, and in this he himself had dabbled, but the Regular Army was apart and aloof from the understanding and from all participation by the thousands of young men occupying regular positions in commercial life or entitled to describe themselves as "independent." Certainly these latter never thought of the Army save as an institution to be viewed through the windows of an officers' mess-room. The average young man of Britain was wont to cheer enthusiastically stories of British heroism. He himself was immensely patriotic and honestly desired to serve his country as best he could. That he did not enlist was due not to his lack of patriotism, not to his failure to appreciate the extraordinary demands which were being made upon his country, but just from sheer failure to understand that he himself could be of any service in the ranks of the Army. Indeed, it would be fairer to reduce down the preliminary hesitation of the young men of England to a sense of modesty rather than to a desire to shirk.

—Photograph 17— A corporal instructs a recuit how properly to adjust his puttees.

—Photograph 18— With the public schoolboys at Epsom. Lieut. F.R. Foster, the famous cricketer, leading the company.

A few days after the announcement had been made in Parliament that the British Army was to be so enormously increased, there appeared on every public vehicle in London a neat placard to supplement the official posters which at that time were covering the windows of post offices and public buildings and were occupying large spaces in the columns of the daily Press. You saw this appeal in long blue and red strips fastened to the wind-screens of taxicabs; you saw it on a larger scale plastered to the sides of the motor-buses, so that no men could enter on his journey cityward without receiving an appeal which for a time he honestly regarded as being applied to somebody else!

It took some days for the leaven to work. But in these days the recruiting offices were crowded. A great throng surged into New Scotland Yard; enormously long queues filled with the youth of the City made their way to the recruiting office. One could not walk through a principal street without passing little self-conscious parties being marched down to the nearest railway station to entrain for the depot of some regiment.

But large as the crowd was, it was, generally speaking, made up of that class of which the rank and file of the Army had always been formed, with—here and there—a sprinkling of a better type of man, and although there was no perceptible response to the recruiting literature which was at this time flooding London—that is to say, in so far as it affected the higher grades of commerce—the appeal was working. You could not get away from it. It was flashed upon the screens of picture theatres; it appeared on some of the boards before the theatre doors; it was on the tram tickets; it was pasted on the windows of private houses; it appeared unexpectedly in the pulpit and on the stage; it was printed in neat little characters upon leaflets; it sprawled largely upon the gigantic posters with which private enterprise covered whole facias—"Your King and Country need you."

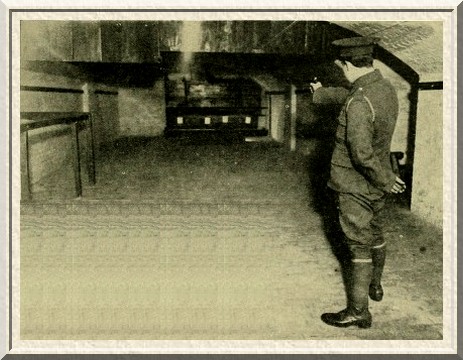

—Photograph 19— Practising revolver-shooting in the crypt of the Kennington parish church.

Young men came up from their homes to their offices, and on the journey they discussed the war, and they expressed their doubt as to whether the number required would ever be raised by voluntary effort. They even went so far as to say that if the worst came to the worst, they would enlist. But in the first few days of the war indeed, until after the British Army was engaged the youth of middle-class England took only an academic or enthusiastic interest in the war according to their temperaments, and never conveyed the impression that they themselves were needed in the actual prosecution of the war.

The Effect of the Great Retreat

But there came sudden enlightenment, which acted like an electric spark: the retreat from Mons, and the publication of a story in a newspaper which purported to be that of a great disaster to British arms. It was this that stirred the imagination and roused the conscience of our young manhood. It is true that the incident reported was not a disaster, though on first inspection it bore a resemblance to such. But the fact that it was published and that it should have received the cachet of the Censor, came in the nature of a shock.

—Photograph 20— Getting fit for the fray. New recruits in the first stages of military instruction.

This was on a certain Sunday in August. There was one day to think over this terrible news of defeated British soldiers straggling all over the countryside in France; of beaten units, the remnants of what had once been great regiments, coming wearily into the little towns of the north of France, to tell their harrowing story to a shocked correspondent. A whole Sunday in which men could walk up and down the front for it was summer time and the summer resorts were filled with flannelled young men who found pleasure in the mild exercises of a promenade and discuss this unbelievable thing, and there was time, too, for the real significance of the news to sink in.

You can only understand the seeming apathy of the nation in the early days of the war (though the superficial observer would see nothing to support the theory of apathy in the huge crowds before the recruiting office) by probing into the British mind, and understanding something of its hopes and beliefs. We had found ourselves allied to two great countries two great military nations, one of which was capable of putting seven million men in the field, and the other four million men. We had talked of the Russian "steam-roller" army, which would slowly move across East Prussia, spreading its millions like a cloud of locusts across the fertile lands of Silesia and East Prussia. We knew that the French were so ready for war that on the first trumpet-call three or four million men would stand to arms. But our people knew nothing of the intricacies and the difficulties of mobilisation. They knew nothing of political factors in warfare, that might keep an Army cooling its heels whilst new equipments were procured, or of the enormous distances over which Russian soldiery would have to cross before they could be concentrated on the enemy's front.

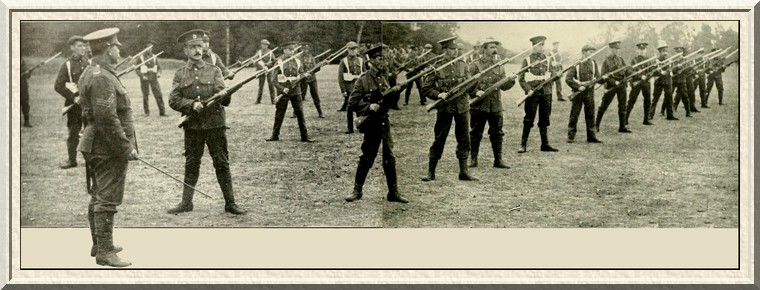

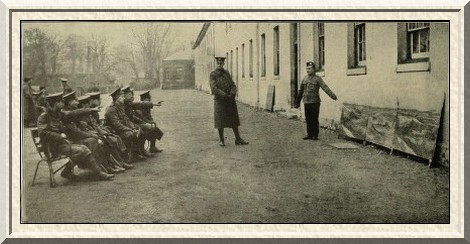

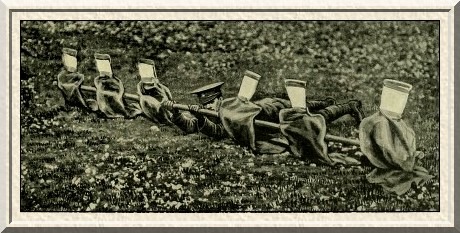

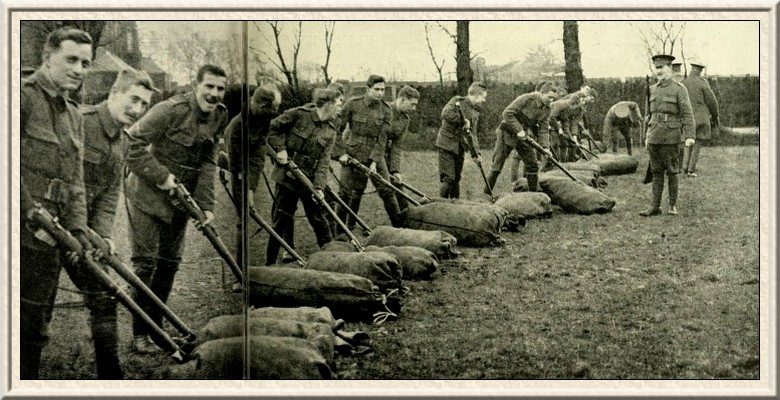

—Photograph 21— Recruits being taught the first movements of the bayonet exercise.

On that Sunday there was one question asked: Where are the French? Wherever they were, or whatever they were doing (and we know now how they were occupied), it was obvious they were not in a position at that moment to help this retiring British Army, battling from Mons to Maubeuge, from Maubeuge to Le Cateau, and fighting every inch of its way towards Paris.

That was a thought to ponder on; it gripped them hard. Monday morning took the great army of young men by train, by 'bus, by tram-car, or driving their own cars in many cases, to their offices and their businesses in the city. At every few yards they were confronted with the simple statement that their King and their Country needed them. Then, perhaps, the inspiration came in a flash that it was they themselves to whom this appeal was being made!

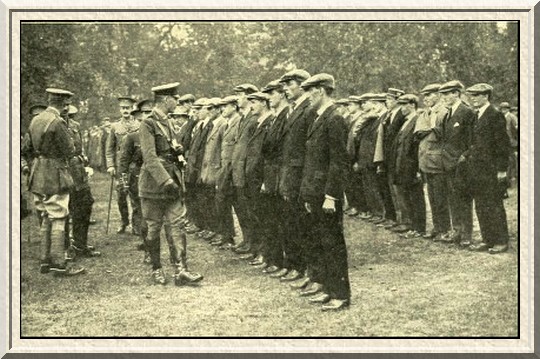

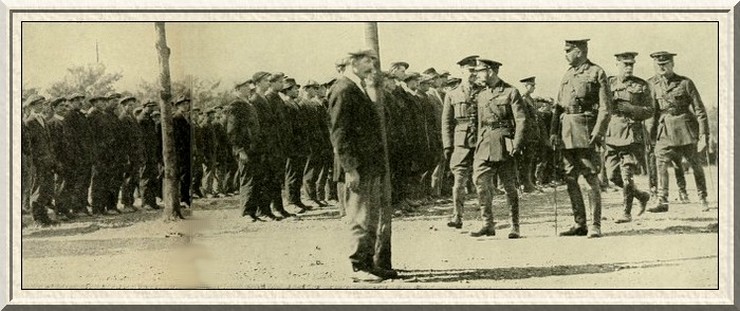

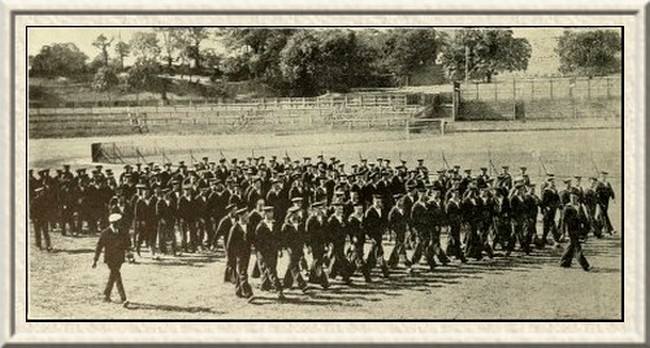

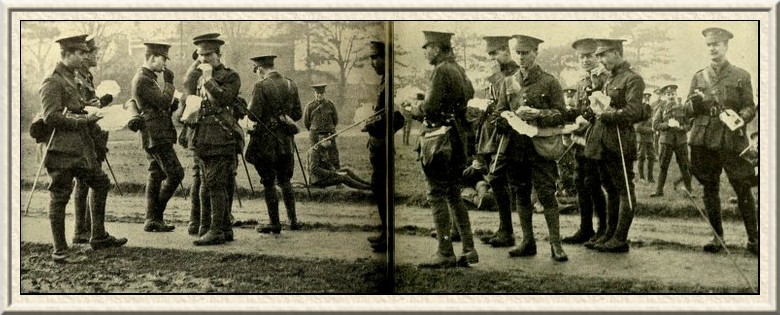

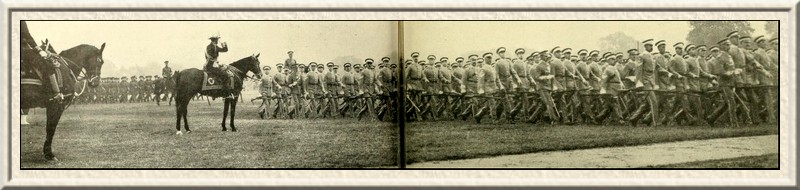

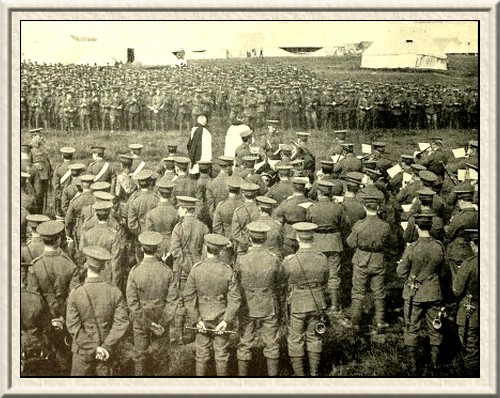

—Photograph 22— The Empire Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers being inspected in Green Park by Major-General C.L. Woollcombe.

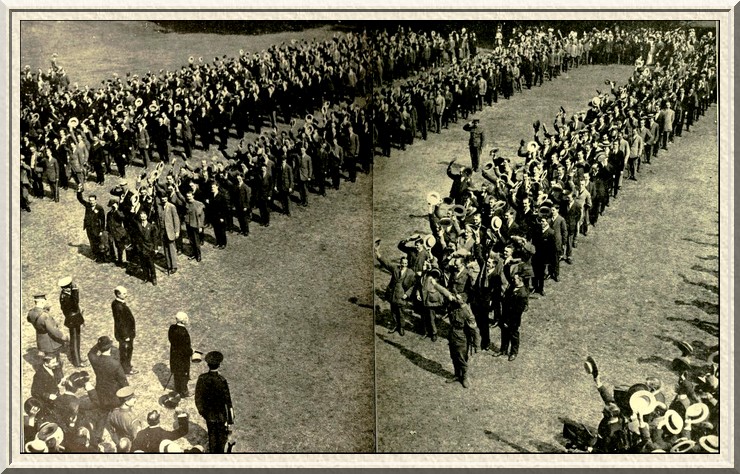

—Photograph 23— The late Field-Marshal Lord Roberts inspects units of Kitchener's Second Army in Temple Gardens.

Thousands of young men went to their offices on that Monday with their minds made up. The resolution had come. Grave employers, sitting in their private offices, received deputations—in some cases of nine or ten to twenty men—, who explained their position. In nearly every case the employer commended, encouraged, and sympathised, and did his part by rapidly improvising a system by which the dependents of his employees should not suffer by the heroism of their men. I know at least one employer who was dumbfounded. "Certainly, my young friend," he said to a score of young men who entered his room one after the other to say they meant to offer themselves. "Certainly, my young friend; do so; let me know the result, good luck." These young men went off to the recruiting office and never returned. This was what dumbfounded their employer. He had the vaguest idea of these things. He expected they would all come back and report themselves with a few days allowed them to clear up affairs, enabling him to make fresh arrangements to fill their places! He knows now Kitchener's new men were allowed no days of grace before taking up their training. New faces appeared in the recruiting queue, a new type of recruit began to elbow its way to the front, first in a trickling stream and then in a whole volume which made the normal river overflow into a dozen little subsidiary streams each making for one of the new emergency recruiting stations which were being opened all over the town. A new tone came to the tents, a new intonation, a suggestion of Public School and University. Kitchener's Army was gaining ground now at a tremendous rate, for it was taking to itself all that was best, physically and mentally, of English manhood.

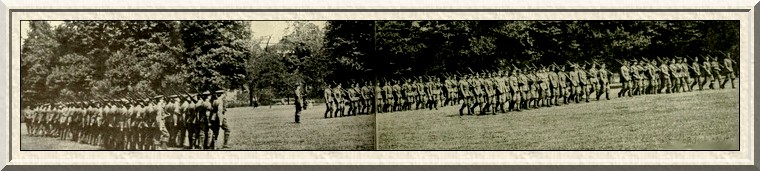

And now London began to see extraordinary sights. For playgrounds and open spaces, in which the voices of children had predominated, now resounded to the sharp, staccato words of command issued by drill- instructors. The patter of children's feet was gone, and in its place the tramp of marching men. Healthy young Britons in their shirt-sleeves wheeled and formed, advanced and retired, formed two ranks and four at a sharp order, and with head erect and chest expanded, went seriously to the business of preparing themselves for national defence.

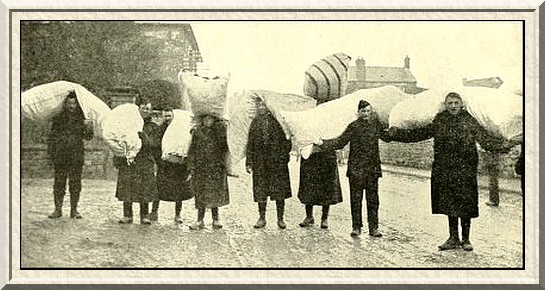

—Photograph 24— Recruits of the Lancashire Regiment carrying their beds through a Wiltshire village to their camp.

The great public parks and open spaces were filled; even in the paved churchyards of London, one saw these eager recruits at their work. On the sacred lawns of the Inns of Court, whence the pedestrians were warned in time of peace, squads marched and manoeuvred. You saw them swinging through the city, alert and cheerful, wearing their civilian garb, without arms, uniform, or equipment, shaking themselves into the mould in which heroes are cast.

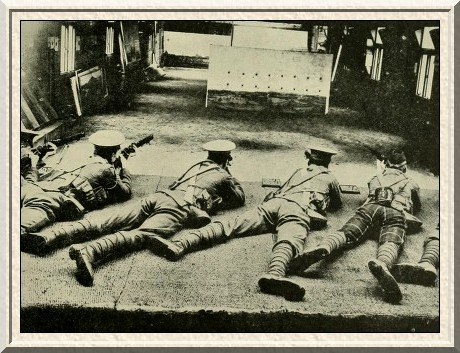

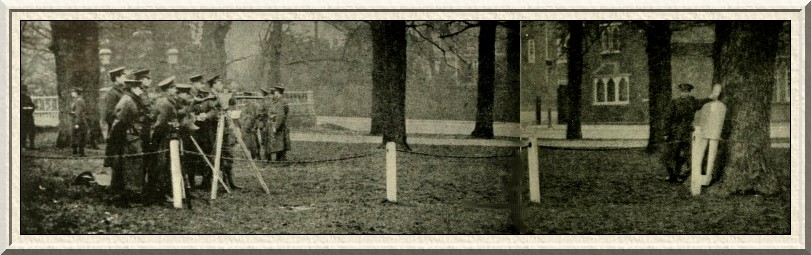

Day and night the work went on. Every miniature rifle range was commandeered by the military. New little ranges came into existence in the most unlikely spots. In some cases they were to be found in the gloomy crypts of churches; these offering, as they did, a great amount of quiet space, were utilised to train the men in firing and aiming. And even as the recruiting office absorbed its thousands, other thousands came; the congestion grew heavier, though now the streams of recruits moving into barracks had swollen until they were veritable rivers. Half the passengers by the trains which moved out of London north, east, south, and west were men of Kitchener's Army, men who, perhaps, a week before had been sitting in their offices waiting for such news of the war as they could secure from the newspapers, with no idea of themselves forming part of the great brotherhood which was engaged in thrusting back the enemies of civilisation, and who now had a deeper and a more real joy in the knowledge that they were assisting in the great and splendid work.

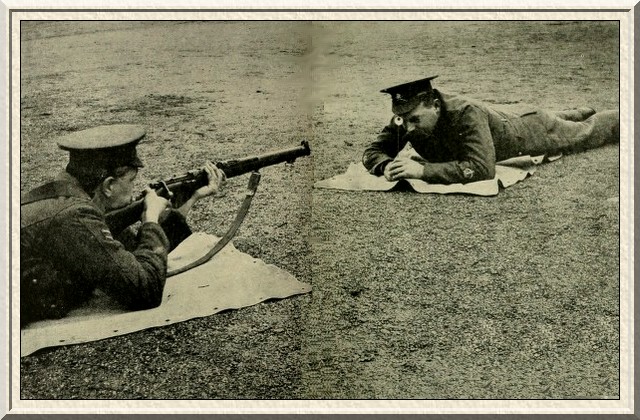

—Photograph 25— A recruit receiving instruction in rifle-shooting.

What the Employers Did

Some businesses were wholly denuded of managers, clerks, and employees. But though it might spell ruin to the patriotic employers, no obstacle was placed in the way of men enlisting; and, indeed, the employer realising, perhaps, that he himself was past the military age, prepared a sacrifice on his own part, and offered to the families of these patriots what compensation for the loss of their bread-winners it was possible for him in his circumstances to make.

This enormous influx of recruits was taken to the Army without any sensible disturbance of industry. It was carried out, too, and could only be carried out, with the hearty co-operation and help of the women of England. To the mothers and wives of Kitchener's new Army the nation owes a great tribute of gratitude. No record of the fine achievements which our young men accomplished would be complete unless reference were made to the magnificent spirit of the women of Britain, who sent their men to war without flinching.

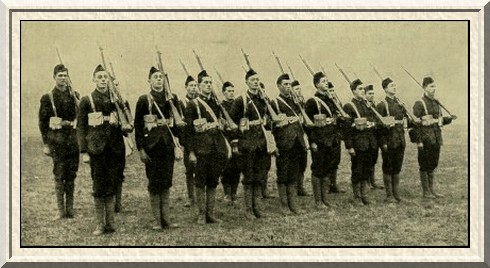

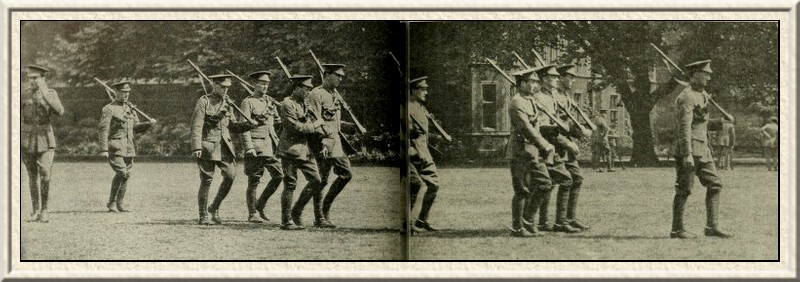

—Photograph 26— A squad of "A" Company, 8th Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment, "at the slope" at Wokingham.

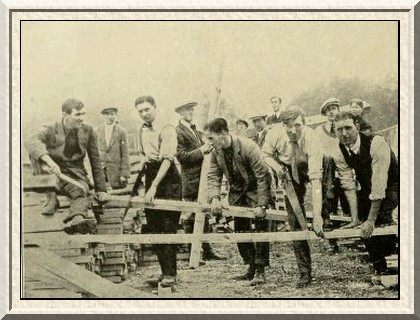

—Photograph 27— Recruits build their own huts. Cambridge University men busy with the saw.

It was brought about also by the sacrifice of our titled families and of landed proprietors, who not only gave their sons, their money, and themselves to the cause, but placed at the disposal of the military their lands.

All over England, in every private park, on every common, on every recognised camping-ground, were to be seen, in the late summer and the early autumn, the white tents of this new force, and the men themselves, split into squads and companies, were learning the rudiments of their craft near by.

"The Levelling-Up" Process

Our recruit, with his strange, new friends, who have come so suddenly into his life, but whose faces he will see for many a long day, not only in barrack and camp, but on the field and in the firing trenches before the enemy, marches through this new London, blazing crimson and blue with recruiting posters and cheery appeals to the laggard, to a railway station where hundreds of other small parties are filling the platforms and waiting their turn to shake the dust of London from their feet and begin the serious business of soldiering. Waterloo Station in those days was a remarkable sight. From Waterloo, Aldershot was fed; so, too, was Borden Camp on Salisbury Plain; so also, was Winchester, the great rifle depots and the headquarters of the Hampshire Regiment; Southampton, where a camp had been established; Devizes, the headquarters of the Wiltshire Regiment, and the great artillery camps at Okehampton might only be reached from this station. Waterloo was, the military station for all arms, and every train that drew out, whether on its way to Exeter, where the gallant Devons were mobilising, or towards Aldershot, that remarkable soldiers' town, was packed full of light-hearted but determined men, who had already settled down, and had taken to themselves the happy and buoyant spirit of their new profession.

Let us picture the position of the new recruit, who has come from a comfortable home, and has had a good education. He is now meeting for the first time, not the soldier confident, alert, and with that indefinable quality which every British soldier possesses of genial tolerance, but new, strange, raw elements, which, perhaps, more than any other, would, in ordinary times, jar on his nerves. He who has come a house in which his every need has has been anticipated either by a doting parent or by trained servants, finds himself on equal terms with the son of the charwoman, whose existence he had hardly noticed. The son of the charwoman recognises his new comrade, and is the more embarrassed of the two.

What is the logical development of this new mingling of elements? The Army experience teaches us that men in the Army level up, as men in all noble professions must do. Groups having a noble object, or an elevating object, or an object calling into play all the finest qualities of the race, must, in course of time, reach an average level a little lower than the highest, but certainly much higher than the lowest, intelligence in that group.

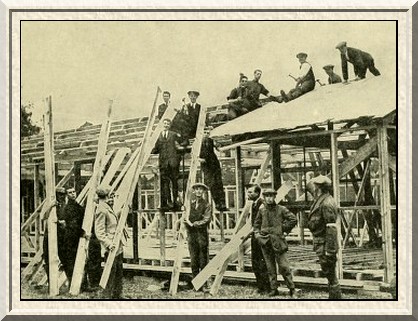

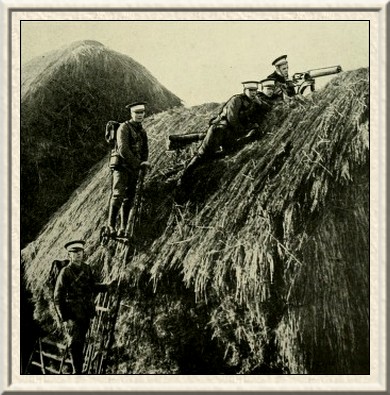

—Photograph 28— Men of "C" Company, 4th Batt., Royal Fusiliers, working on a roof.

It would be absurd to say that instantly, by the mere taking of an oath, these two incompatibles are going to be brought down to a common denominator, if the jumble of terms be allowed. They will each edge towards one another from the very first. The better-class man will unbend and unstiffen and get down as far as he can; the other, the more humble, will reach up to the best of his ability.

Some day, after hardships mutually endured, after privations commonly shared, these two will meet together on a common ground, man to man, and find something very admirable in one another, and learn to respect each other's "best."

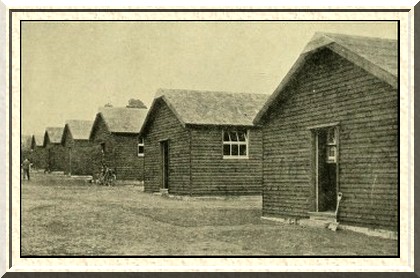

—Photograph 29— The finished hut. The temporary home of the recruit.

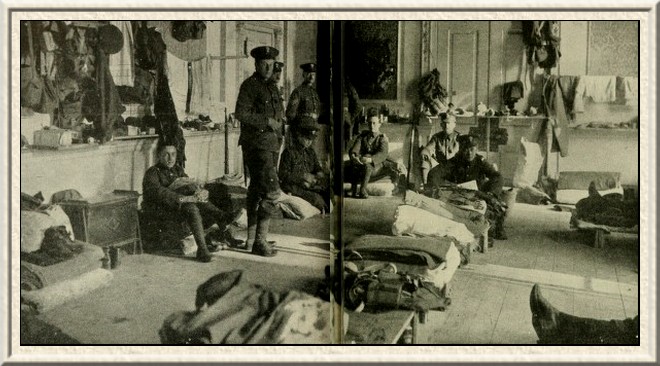

The Recruit In Barrack And Camp

Let us follow the fortune of the recruit when he has taken the oath of allegiance, and when, in company with perhaps fifty or sixty other men, he is marched through the streets of the town to the railway station which is to carry him to his depot. He has probably applied for a certain regiment, or, if he has not done so, perhaps a batch of soldiers are required for some particular corps.

Since they have no particular wishes they are earmarked for the regiment requiring recruits, and in batches of fifty and sixty are marched off to join their unit.

—Photograph 30— Men of the King's Liverpool Regiment at bayonet practice.

Fortunately, when the great rush was on the weather was warm—was, indeed, very hot, and the immediate inconveniences which the recruit was called upon to face were not of such a character as to unduly distress him. He arrived at his depot in some quiet little country town to discover the barracks crowded out, every available tent filled, the recreation rooms, libraries, and gymnasiums crowded with men; and he learned with dismay that there was no place for him to lay his head. A somewhat discouraging experience for the young patriot, fired with a desire to serve his country, but one which was borne with infinite good humour. A couple of blankets were handed to him, and he was told to sleep where he could. The weather, as I say, was of such a character that al fresco "lodgings" entailed no great hardship; and under the old trees of the barrack square, or on the sloping meadows behind the barracks the new- comer laid himself down and made himself as comfortable as he could, enjoying, perhaps for the first time in his life, a night under the stars.

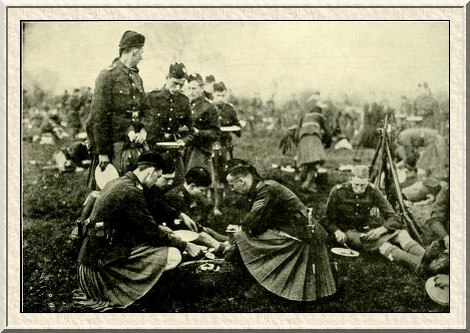

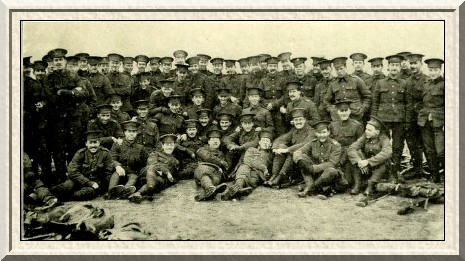

—Photograph 31— No. 13 Platoon, "D" Company, 5th Cameron Highlanders.

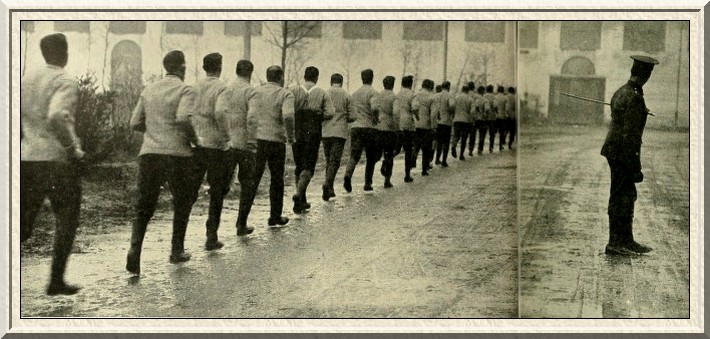

—Photograph 32— Inns of Court O.T.C. Infantry being instructed in slow marching at Lincoln's Inn Fields.

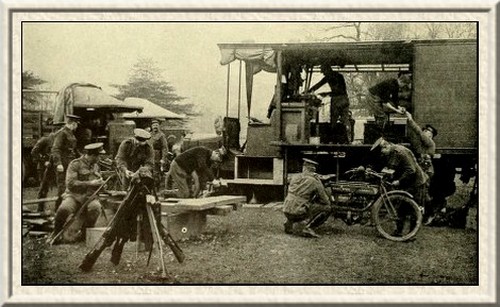

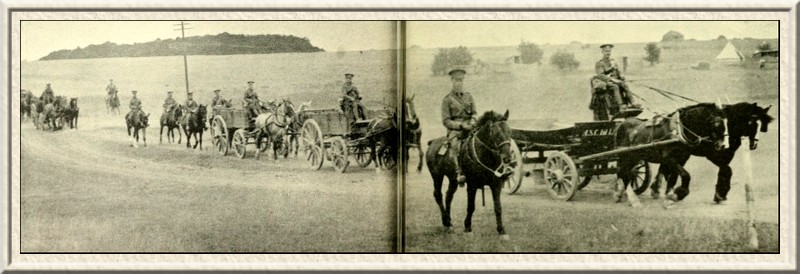

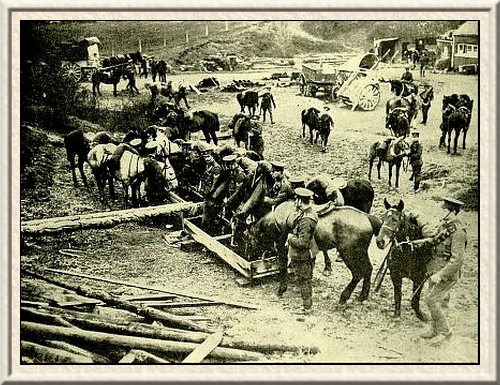

But all the time the authorities were working at top speed to relieve the congestion. The depot, crowded as it was, did not hold the newcomer for very long. The skeleton of the new battalion appeared upon some far-away down; a dozen great army transports dumped their canvas bags, their sacks of tent-poles and their floor-boards, and left them in charge of an Army Service Corps officer. Presently appeared an advance party of old soldiers, generally drawn, as far as was possible, from the regular regiments, and, failing those, from the Special Reserves which had had experience of camping out; and two long lines of white tents appeared, a great marquee for officers' mess, other marquees for stores. A quarter- master arrived on the spot, a small group of officers who surveyed the empty tents a little gloomily, a handful of non-commissioned officers, who drew from the big marquee store now becoming rapidly furnished with the stationery which is indispensable to army organisation their various "requisitions" and "returns," their books and their camp equipment. New lorries appeared, long trains of Army Service Corps wagons, filled with blankets, waterproof sheets, arms and ammunition; and then on top of these a few men, obviously old soldiers, chosen for the work, who were quickly promoted to the rank of Lance-Corporal or Corporal, and whose duty it was to find the first guard for the new camp.

And then the men began straggling in. They came in little parties of fifty and a hundred from the depot, which had fitted them with khaki, carrying their white canvas kit-bags containing spare uniform, boots, shirts, and such knick-knacks and extras as wisdom dictated. Some of them could cook; these were requisitioned at once by the Sergeant master-cook, on the look-out for likely regimental chefs. A great many, perhaps, in the early days could keep accounts; the quartermaster required some of these, the Commanding Officer others. The sprinkling of officers, keeping a sharp look-out for men of intelligence were not slow to distribute chevrons of promotion as the days went by. To the keen man in Kitchener's Army promotion came quickly.

The Steady Flow Of Recruits

Steadily men were coming in; every evening brought a fresh party, every morning found another line of tents extending farther back from the original line; and every day the gathering of troops upon the adjacent improvised parade-ground grew larger, until upon one fine morning four strong double companies stood to attention, and it was whispered abroad that the battalion was "full."

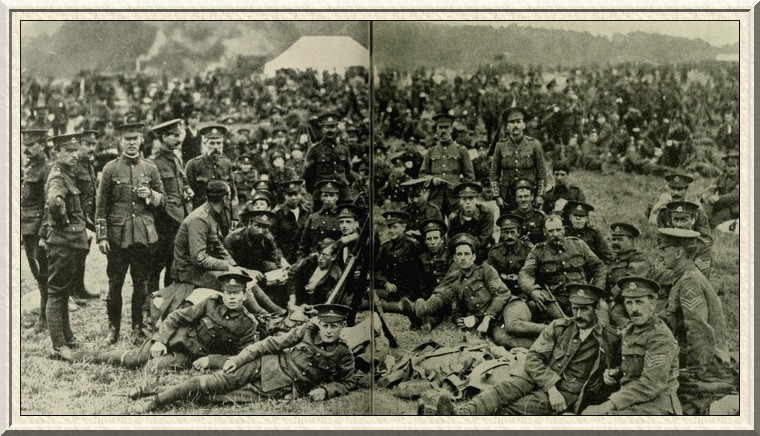

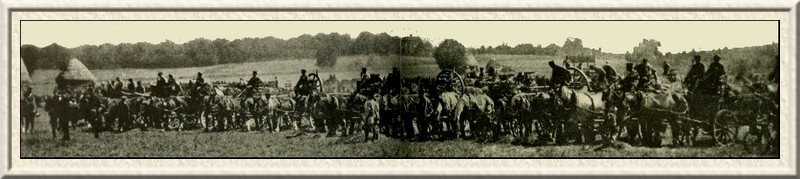

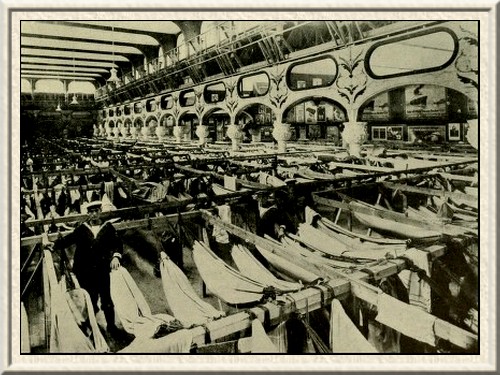

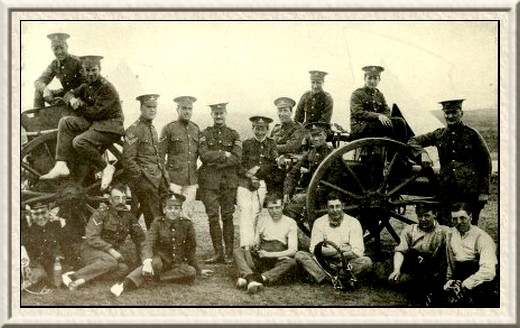

—Photograph 33— The new army in the making at Aldershot.

—Photograph 34— His Majesty the King, accompanied by Lord Kitchener, reviewing recruits at Aldershot.

All this time new officers had been arriving. In some cases they had travelled thousands of miles in order to lend a hand in constructing the Kitchener corps. In one case an officer travelled day and night for 4,500 miles, leaving his ranch he was farming at the foot of the Rocky Mountains in order to offer himself as a subaltern. He had been an officer and had retired, and now, at the first call of duty, he had returned, as thousands of others had returned, to the colours.

The battalion was indeed full, and had been full long before the men of that battalion had suspected it. For in another part of the country, and upon yet another open plain, the same process of building had been going on, with the help of men drawn in some cases from the first new battalion. New stores had been erected, new tent lines laid down, and new stragglers had appeared, and by the time the 1st Service Battalion had reached its full complement of men the second was half filled.

So this process went on. One battalion followed hard upon the heels of the other. On different ground, under different conditions, but bound together by the regimental badge they so proudly wore, the young battalion were getting fit.

It will be as well to describe something of the machinery for receiving and distributing the supply of recruits which comes in ordinary times, and which was utilised to such excellent purpose to dispose of the great rush of new soldiers after the outbreak of war and the issue of Lord Kitchener's call.

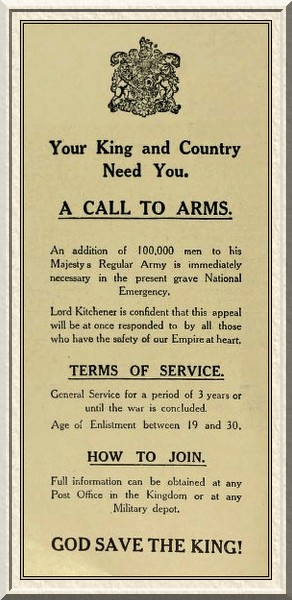

—Advertisement— The Start of Lord Kitchener's Army. The first advertisement issued by the War Office, August 8th, 1914.

The United Kingdom and Ireland are divided into a number of "commands." Taking them alphabetically, we come first to the Aldershot command, which includes a part of Hampshire and that portion of Surrey in which the Royal Flying Corps are stationed, at Brooklands. The Eastern command comprises Northamptonshire, Cambridgeshire, Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Huntingdonshire, Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire, Middlesex, Kent, Surrey, Sussex, and Woolwich. The Irish command takes in the whole of the troops in Ireland; the London (district) command includes the county of London and Windsor; the Northern command takes in Northumberland, Durham, Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Staffordshire, Leicestershire, and Rutland. Then there is the Scottish command. Warwickshire, Worcestershire, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Berkshire, Cornwall, Devonshire, Somersetshire, Dorsetshire, Wiltshire, and Hampshire are in the Southern command. The Western command takes in Wales and the counties of Cheshire, Shropshire, Herefordshire, Monmouthshire, Lancashire, Cumberland, Westmorland, and the Isle of Man.

In these commands the organisation was completed for the creation of three new armies, a number afterwards increased to six, and even then adaptable to increase. These were the armies to be fed through the gaping doors of the various recruiting centres, and it was left to the depots to make the first rough organisation of the fresh armies and to act as sorting boxes into which the new men were grouped.

In Great Britain and Ireland there are sixty-eight infantry depots, each designated with a number and generally referred to as the centre of a regimental district. These regimental districts take their numbers from a regiment which has its headquarters at the particular depot. Thus, the 1st Royal Scots (1st Regiment of Foot) is in Regimental District No.1; the Queen's 2nd Royal West Surrey Regiment is in Regimental District No.2; and so on.

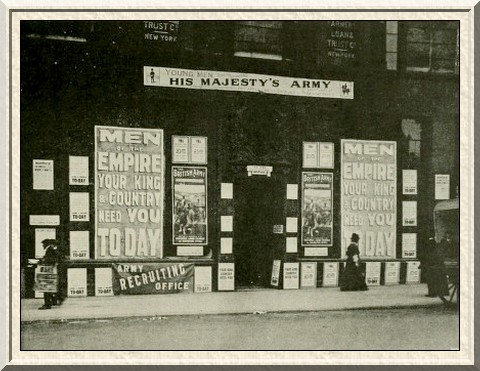

—Photograph 35— The fortune of war. The London Office of the Hamburg- America Line transformed into a British recruiting office.

In addition to these sixty-eight regimental depots, which are the homes of the corps, and in which most of the records are kept, there is a Guards' depot at Caterham, and a rifle depot at Winchester the Rifle Brigade being the one regiment in the British Army which does not boast of a number.

It was on this foundation that the new army began to build. If we take as an example one particular regiment, the reader will more easily understand how Kitchener's Army came into the forces. We will take the 50th Regiment, the Royal West Kents, with its headquarters and regimental depot at Maidstone. The 1st and the 2nd Battalions being regulars, the one with the Expeditionary Force and the other in India, we need not trouble about them. The 3rd Battalion was the Reserve battalion. That is to say, it was made up of militia, and, though primarily designed for home defence, could serve in case of emergency as the feeder to the Battalion at the Front, or, if necessary, could be employed en bloc in the field. The 4th Battalion you will find in the Army list marked with a small circle and a St. Andrew's cross. This is an indication that this battalion, which is Territorial, has volunteered and has been accepted for foreign service. The same mark is found against the 5th Battalion, and, as a matter of fact, both 4th and 5th are employed, and have been sent abroad in order to relieve first line troops which were sent from this country.

After the 5th, in normal times, we might find a record of a Cadets Battalion, but in time of war the Cadet units are dismissed in three short lines. Following the 5th we reach the 6th Battalion, and now we have come to the first of the new "Kitchener" battalions which have enlisted since the war.

After this follow the 7th Service Battalion, and then the 8th and the 9th. This regiment may be taken as a microcosm of the whole army. We have the two regular battalions, one of which is serving in India and one at the Front; we have the Special Reserve, which is probably in England and is being utilised either for home defence or to feed the 1st Battalion; we have the two Territorial battalions, that is to say, the volunteer corps, which have been mobilised and sent abroad in order to relieve first line troops; and we have four brand new regular battalions of that regiment, formed from the men who had taken their place in the queues at the recruiting offices to form part of the new and splendid force which had come forward at the nation's call.

Not all the regular infantry regiments stationed abroad returned, though in the majority of cases they were brought back to the field. But it is safe to say, so far as Kitchener's Army was concerned, that the first results of recruiting meant that, where one man stood in the field at the beginning of the war, he was reinforced by four others before the war had progressed very far.

How did the recruits to Kitchener's Army "shape"? In what manner did the recruit come to his own, and, from being a raw and awkward civilian, slow to move and slower to obey, develop into the smart, alert soldier? The story of his initial hardships and difficulties, of his extraordinary development, of the tragic comedy of his blunders, and of the gradual transformation which came to him, which developed him from an irresponsible civilian into a disciplined soldier of the King, will be told in the next chapter.

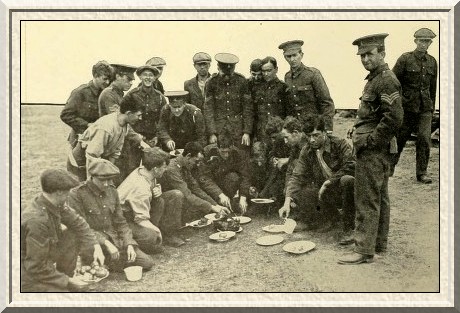

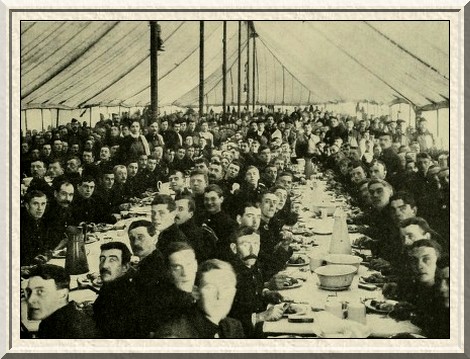

—Photograph 36— Kitchener's Army had nothing to complain about in the matter of rations; the above is a typically happy group at dinner-time.

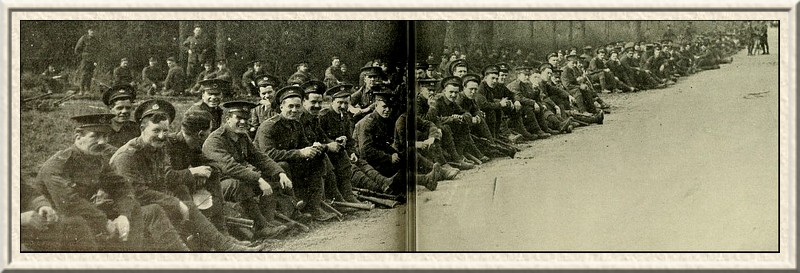

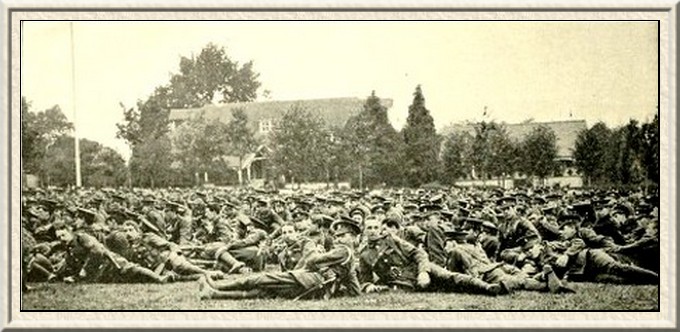

—Photograph 37— Men of the South Midland Brigade taking a welcome rest on a march.

The recruit passed from the depot in a very short space of time, to the battalion to which he was to be attached for the remainder of his service. As a rule three days sufficed to fit him with his suit of blue serge, to be replaced later by khaki, his boots, underwear, and overcoat.

Barrack accommodation was quite inadequate to dispose of the new battalions the more so since most of the permanent buildings, barrack rooms, etc., were requisitioned by the quartermaster for the safe storing of clothing and equipment. The buildings, therefore, were replaced by tent lines, and where these were insufficient, the remainder of the troops were billeted. In other words, the householders in a town or village were asked to provide sleeping accommodation for the men of Kitchener's Army, and were rewarded at the rate of ninepence per man per diem. For this they were asked to do no more than give him a place to sleep in, and allow him the use of their fire for cooking purposes. Our recruit might, and often did, find himself fallen upon pleasant places. There were pleasant stories of billeting landlords and landladies who provided Private Brown with his cup of tea in bed, and gave this lucky soldier the liberty of a warm bathroom at all hours of the day and night. The legends which surrounded the billets are numerous. There is the case of a fortunate soldier who journeyed to parade every morning in a most expensive motor-car, and was whirled home, when the parades were finished at night, in the same lordly conveyance provided by his host.

The average recruit was not so favoured, and upon his arrival with his new battalion, had to be content with tent accommodation. The method of "telling off" was simplicity itself. Upon arrival he and his fellows were formed up for inspection by the adjutant, and so many of the new men were allocated' to one company and so many to another. It was then left to the company sergeant-majors to dispose of the newcomers according to the accommodation available.

A great number of huts had to be hurriedly erected to accommodate the troops, more especially after the advent of almost the wettest winter on record. The canvas tent in many places had to be abandoned in favour of the wooden hut. Soon we had "Hut Towns" dotting the landscape all over the country.

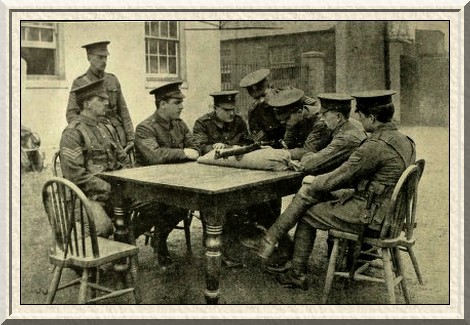

—Photograph 38— Kit inspection of a Kitchener's Army unit at Cambridge.

As an instance of how the welfare of the men was looked after the following story of Lord Kitchener is told. There had been complaints of faulty huts which had been too hurriedly built. He made a surprise visit to a certain camp, examined every completed hut; there were roofs which were not watertight, floors which were imperfect, and so on. Kitchener acted with characteristic promptitude, he would brook no imperilling of the health of the men. He instructed the commanding officer to find billets for the whole of the men at once, and they were not allowed to spend another night in the huts.

Under the guidance of a corporal the new recruit introduced to his future comrades. The round bell-tents, with their curtains rolled up to allow free ventilation, with their blankets neatly strapped at frequent intervals in the circle, were inviting enough, though the recruit could tell that he would find the boards which formed the floor of the tent a poor substitute for the mattress he had known in his civilian days.

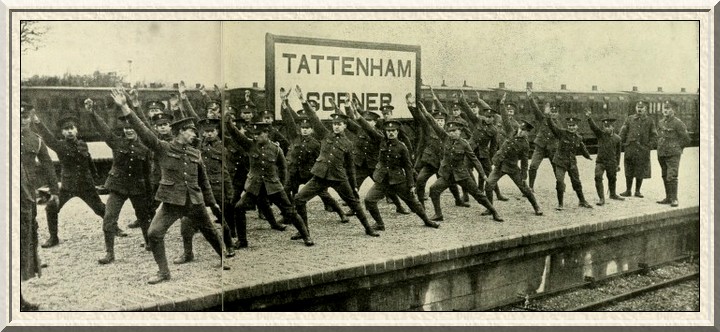

—Photograph 39— 1st Battalion of City of London territorials at Swedish drill on Tattenham Corner platform.

The First Night Under Canvas

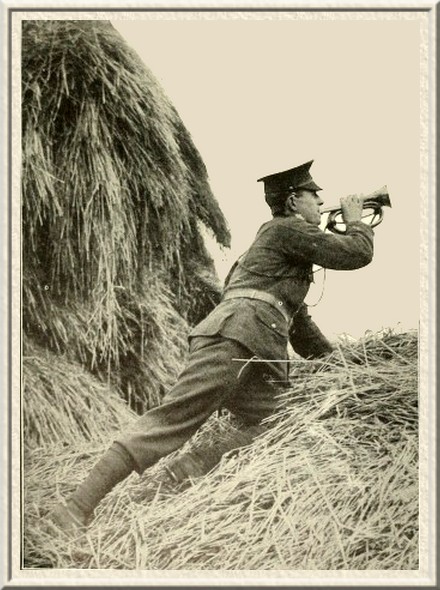

It was a restless night for the recruit, this first night under canvas in these strange conditions; a night, moreover, in which he realised the limitations of the human frame, as he endured the discomforts of sleeping on a wooden floor; in fitful, fluttering dozes the night passed. It was almost a relief when the long trembling call of the reveille blared through the tent lines, proclaiming the beginning of his day.

He went out into the raw morning air, and was astonished to find, even in the late summer, a white frost on the ground, and to discover also that the water which was brought to the camp by iron pipes from the nearest supply was very cold.

A quick wash and brisk rubbing with his hard towel, and life took on a new and cheerful interest. Me was consumed with curiosity as to what the coming day would hold. He remarked with awe and admiration the facility and ease with which the men of the regiment—many of them only his seniors by a few days—fell into the somewhat complicated routine of military service.

Comforted by a cup of coffee, which he ladled from the steaming dixies which the cook had prepared, he fell in to his first parade. By companies the regiment swung through the country lanes at a brisk march, varied now and again by a "double" (that is to say, a jog trot), and after this exhilarating little walk, lasting no more than half an hour, the companies came back to camp to eat a hurried breakfast, and to prepare for the more important work of the day.

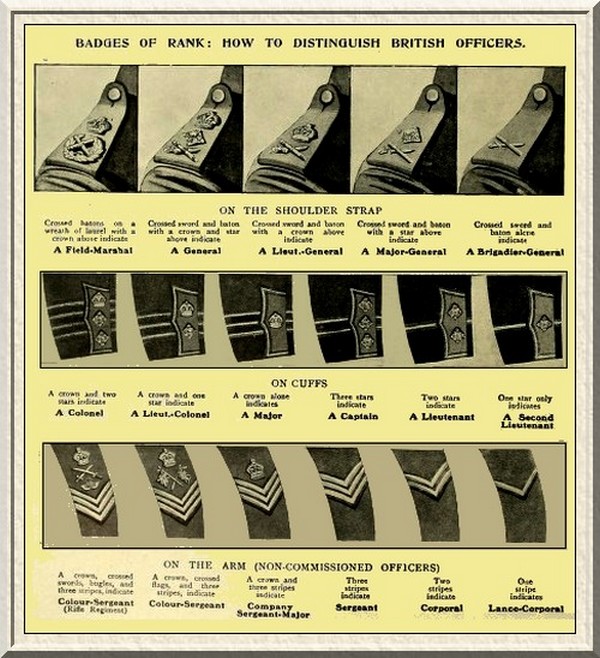

As yet he was very ignorant as to rank, and very dubious as to whether the youthful officer who came round in the morning to see that the tent flies were rolled up and that the blankets, were neatly folded in tidy heaps was a colonel or a sergeant-major. His stay in the depot had been a very brief one, a very crowded and somewhat chaotic experience, in the course of which he had neither the time nor the opportunity to acquire even a rudimentary military knowledge. But it was never long before the inquiring recruit found a guide, philosopher and friend. Searching helplessly round, and most anxious in his strange position to find some new acquaintance, he would come upon the inevitable old soldier who, from the height of seven years' service, would look down with a forbearing eye upon the struggling ignoramus, and, whenever possible, would lend a helping hand.

—Photograph 40— Men of the 17th Welsh Battalion, otherwise known as "The Rhondda Bantams" or "The Welsh Gurkhas", with the army boots which have just been served out to them.

One day I heard him patiently explaining, "That man there with one star on his cuff is a second lieutenant. He's as raw to the game as you are, but he's learning. Don't take much notice of what he tells you, because he doesn't know anything. If you want any advice—come to me."

An astounding and arrogant claim, but perfectly justified, as the recruit was to discover.

—Photograph 41— When Lord Kitchener inspected many thousand territorials on Epsom downs the weather was wintry in the extreme, but nevertheless the men looked cheery and fit as they marched to the parade ground.

"The other chap over there with one stripe on his arm—we call it a 'dog's leg' because of its shape—is a lance-corporal. The man with two stripes is a corporal; with three stripes, a sergeant. The man with the crown above his three stripes is the old colour-serjeant. We call him company sergeant-major now, but he's just about the same as ever."

—Photograph 42— Cambridge has been "occupied" by Kitchener's Army, and several colleges are full of soldiers. The photograph shows Trinity College in the hands of the military.

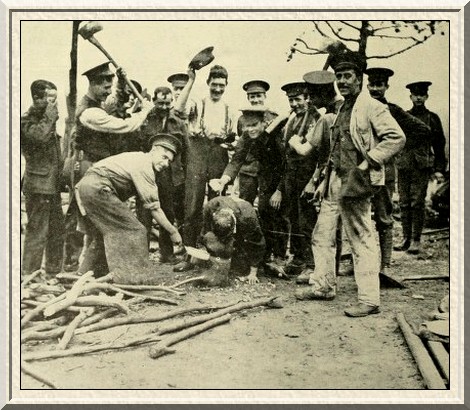

This the recruit learnt at breakfast-time—a breakfast which was surprisingly luxurious, consisting of tea, bread and butter, eggs, and just enough bacon to give flavour. This breakfast had come mysteriously from nowhere. Later he was to discover that at the far end of the camp things had been moving since before reveille, and whilst the battalion had been doing its little constitutional, there had been great breakings of eggs and splutterings of frying bacon, whilst steaming kettles had been bubbling over their wood fires, and the restless cooks had been working at top speed to provide a thousand hungry men with their breakfast.

Breakfast had hardly finished when the warning bugle sounded' and the tent orderly—he whose duty it was to draw rations and to clean up the tents—had only begun his work when the blue-coated figures fell in again in four long lines to answer their names and to undergo the trial of an inspection.

Our new recruit at first was painfully conscious of his awkwardness; how awkward he was he did not realise until he found himself in the unenviable position of right hand man of the awkward squad. It was not called the "awkward squad"; it bore the more euphonious title of the "recruits' first squad"; it included a surprising number of men who, unlike himself, perhaps, were not quite clear that their "rights" differed materially from their "lefts," but who, like himself, were anxious to be initiated into the mysteries, even if they did confuse their right foot with their left at times.

Beginning To Learn

Let us start at the beginning of the training. It was a business full of startling discoveries for the new Kitchener men. The recruit was taught the first position of a soldier, which, so far from being a matter of simple understanding, required very serious effort—Body erect, head up, feet turned out at an angle of forty-five degrees, chest out, shoulders back, arms hanging loosely to the sides with the hands lightly clenched a little behind the seam of the trousers." No, it was not simple. When he was asked to extend his chest, he protruded too much of that part of his anatomy which lies due south of the chest. In other words, he had a disposition to force into prominence that portion of his body upon which, according to Napoleon, the Army marches, but which in practice affords the greatest trouble, not to the commissariat department of the Army, but to the drill instructor.

—Photograph 43— A recruit being taught the regulation salute.

It was a strained and awkward position in which he found himself. He had been accustomed to allow his shoulders to slack forward, had developed on his back the suspicion of a hump, which in the Army is called "the boy." This phrase was a perplexing mystery to the recruit, and when he was placidly requested by the exasperated sergeant to "take the boy off his back," he looked round puzzled and bewildered. When the nature of the request had begun dimly to sink into his mind, when he came to realise that standing erect in the first position of a soldier was something of an achievement, the sergeant proceeded to explain other mysteries.

—Photograph 44— Body bent sideways and leg raised— one of the exercises our recruits have to perform.

For instance, when a soldier turns with his whole body, he does so upon scientific principles. The recruit, who had managed for many years to turn to the right or to the left regardless of any scientific rules on the subject, showed a not unnatural desire to dispense with the instructions imparted to him in making this movement. He was considerably surprised to discover how awkward he looked and felt when he shuffled to his appointed place, generally a few seconds after the remainder of the squad, who had already mastered the intricacies of the movement. He learned that, to turn right about, both knees had to be kept straight and the body erect while he swung round on the right heel and left toe, the left heel and right toe being raised. Then when the right foot was flat on the ground, the left heel had to be brought smartly up to the right, and brought into proper position without being stamped on the ground.

—Photograph 45— A strong dorsal exercise— forward lying, trunk bent forward, arms stretched upwards.

All this was very interesting to me as I looked on; it was equally interesting to watch the sergeant or corporal in charge of the squad showing the "young ideas" how they were expected to show respect deference to superiors in a perfectly mechanical yet picturesque style—in other words, how to salute. Possibly the instructor did not trouble to explain that when the soldier raises his hand to the salute he is merely carrying out the practice of the knights of old, who, as they rode in the lists past the enthroned queen of beauty, raised their hand politely, that their eyes might not be dazzled with her splendour. That, at any rate, was the beginning of the military salute, whether the sergeant explained it or whether he did not.

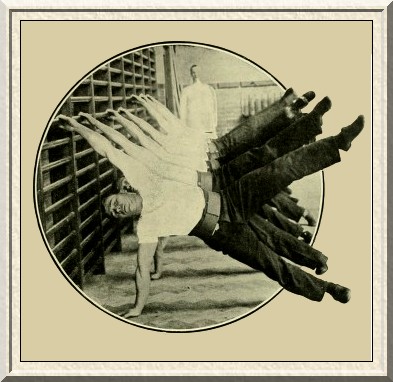

—Photograph 46— Swedish exercises. At the wall-bars—leg-raising.

—Photograph 47— 2nd Lieutenant Cyril Asquith, son of the Prime Minister, drilling with the Queen's Westminsters on Hampstead Heath.

—Photograph 48— Climbing the inclined rope—a difficult exercise.

"Saluting isn't as easy as it looks," remarked the man who knew. "You must swing your arm up stiffly in a line with your body, your elbows on a level with your shoulder; then you must smartly bend the arm and bring your palm to the head, so that the fingers of your hand rest an inch above your right eyebrow."

—Photograph 49— "Hands up!"—but never to the Germans! Recruits performing a drill which will bring them to fighting fitness.

—Photograph 50— Sitting on nothing is not as easy as to may appear.

—Photograph 51— The gymnastic feat of "downward circling" is one our soldiers have to learn.

Many recruits tried other ways of saluting, I noticed. One would bring his hand forward so that his palm blotted out his nose. Invited to try again, he would touch his hat like an ostler.

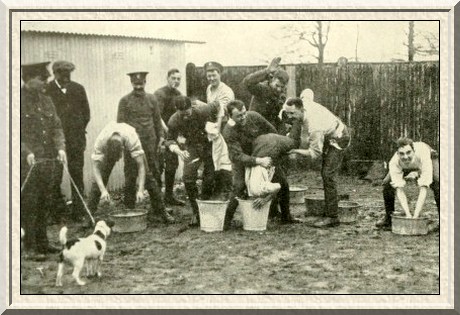

—Photograph 52— The lighter side of soldiering. The City of London Fusiliers assist a comrade to take a bath.

There was only one proper way, however, and he was hectored into it; after a painful ten minutes, the recruit was at last saluting mythical officers with great gravity and earnestness. He had at last come to the conclusion that he would receive no encouragement from the instructor in any attempt to introduce into the British Army a novel way of saluting.

—Photograph 53— After the doctor's visit— Welsh soldiers who have been inoculated against typhoid.

Brief as the time had been at the recruit's disposal since he rose that morning, he had been expected to do something which he hadn't done. This he discovered on the after-breakfast parade.

"Take that man's name, Sergeant," said the officer commanding the company; and the recruit indicated learnt that he was delinquent in some respect. Soon, to his shame, he was to learn wherein he had failed. A better-informed comrade on his right supplied him with the information.

"Not shaved," he muttered under his breath.

"But I only shave every other day," protested the recruit.

A sharp voice silenced him.

"Stop talking in the ranks!"

Apparently you must do nothing in the ranks but stand in the first position of a soldier. You must neither talk nor turn your head, nor shuffle your feet until the order to "stand easy" allows you to do so. If you find that a loose button or an unhooked collar necessitates the movement of your hands, you must step two paces from the ranks, confessing your shame to the world, readjust the deficiency, and step forward again into the level ranks which offers a comforting haven to you once more.

Nevertheless, the recruit in his desperation must make further inquiries.

"What will happen to me?" he asked in a whisper.

The old comrade, staring blankly to the front, and speaking without moving his lips, supplied the information.

"You'll have to parade at reveille to-morrow morning fully shaved, which means you'll have to get up half-an-hour before anybody else, my lad. And you have to shave every day whether you like it or not."

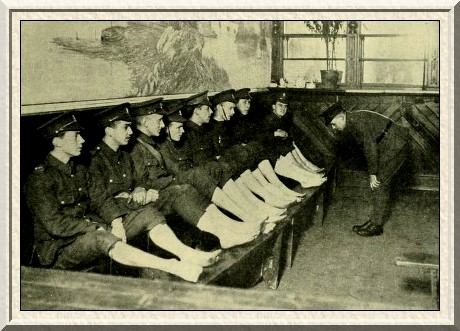

—Photograph 54— Recruits have their feet examined after a route march.

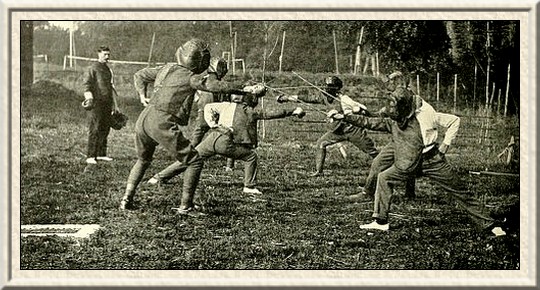

The inspection being over, the recruits were sorted into various squads. To the lowest of all, the recruits' squad, the new man had to make his way. Others farther advanced, and the envy of the battalion, were those already engaged in the noble exercise of bayonet drill; but for the young recruit neither rifle nor bayonet was yet available. His work consisted of a continuous succession of drills which had for their object the strengthening of his frame and the development of his physique.

—Photograph 55— Camp butchers with the Sportsman's Battalion (Royal Fusiliers) cut up the meat for dinner.

—Photograph 56— Making himself at home in a billet— A recruit cooking his dinner.

The recruit was not handed his rifle forthwith. Even if that were desirable, rifles were as yet too scarce to go round. It is true that toward the end of his awkward squad stage, one rifle, jealously and grudgingly loaned, was placed on a tripod before the squad, an object of veneration, and that one by one the men of the squad were allowed to take "sights" with it, but no more. So his time passed in a day made up of " heels raised... head bent... right bend... left bend... neck stretch.... What the deuce do you think you are doing, Private Clark, imitating Mr. Blooming Tree as Falstaff? Stick your chest out... That's not your chest!... Now we will try it again for the benefit of Private Clark... heels raised... head bent..."

Amusing for the squad, but a little trying for Private Clark, who went to bed that night and groaned as he turned his aching form on the unyielding boards.

In three days he would be as much an expert as the best of the squad.

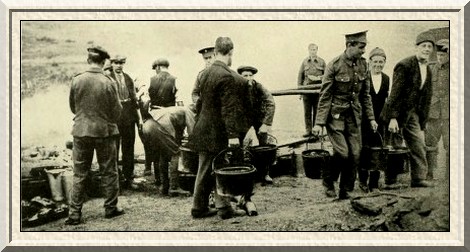

—Photograph 57— Men of the London Scottish at Kingsbury receiving rations from the seargeants.

Upon the regimental sergeant-major and the N.C.O.'s fell the principal burden of instruction. "Sergeant What's-his-name" had some better material than the "mud," which Kipling sings of, to work upon, but the recruit in his "grub" stage before he became even a chrysalis was something of a trial, only to be borne patiently, because of his enthusiasm. "Your right side, Private Smith, is the side you shake hands with," said a long-suffering sergeant to a more than usually obtuse private. "What side do you shake hands with?"

"I never shake hands, Sergeant," said the cheerful recruit. "I always say, 'What ho!'"

—Photograph 58— Carrying rations for distribution.

Physical Training

Time passes quickly when one is engaged in congenial occupation. Doubtless with his mind fully occupied with the new knowledge he is acquiring, a young soldier finds on the first morning of his training that the order to "stand easy" arrived much sooner than he expected. That he should not feel the effect of standing still for too long a period one of the greatest trials, I think, that a recruit endures the movements were varied by what might appear to the onlooker needless marches up and down the parade ground, in the course of which he learnt how to turn or wheel about whilst on the move. This latter process required less scientific effort, it being merely necessary that he should emphasise the change of his direction by a smart stamp of the foot. All this was quite simple compared with the drill which followed later in the day.

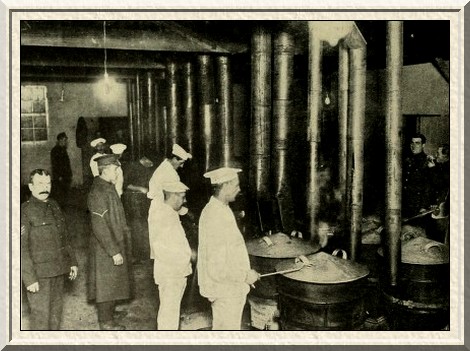

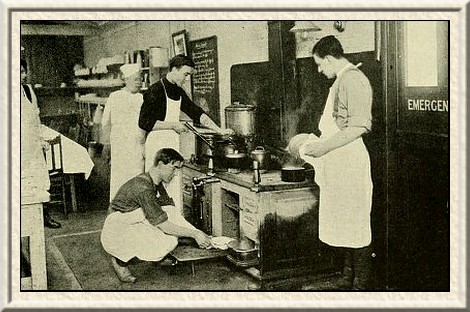

—Photograph 59— A camp kitchen at Aldershot.

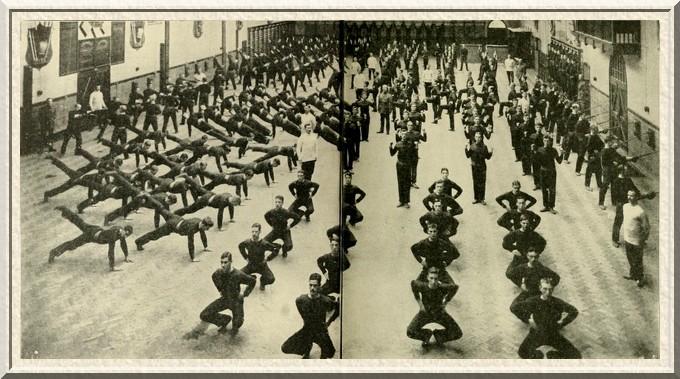

In ordinary times the young recruit goes through a course of physical training at the depot or regimental gymnasium. The minds which improvised the great Kitchener army did not hesitate at improvising gymnasia.

—Photograph 60— A model cookhouse on the Belton Park estate, Grantham. The kitchens are scrupulously clean and wonderfully equipped.

The course of physical drill was considerably changed, and only at Aldershot, where the large gymnasium offered facilities not so much for the recruit as for future instructors of gymnasia, was the old Army course maintained. The work or drill designed to improve the physique of the soldier was carried out in the open air.

The gymnasium work of a regiment is largely in the hands of the gymnasium sergeant (crossed swords over his three stripes indicates his calling). There were hardly enough of these N.C.O.'s to go round the 390- odd new battalions which came into existence in the first months of the war.

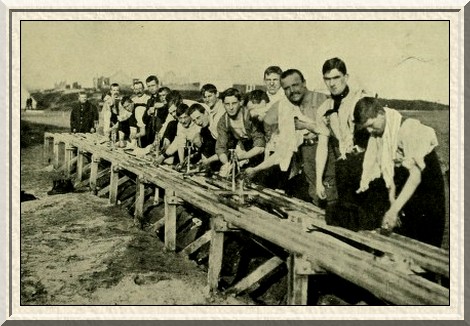

—Photograph 61— Recruits at their early-morning toilet.

Something less grand, therefore, than the palatial gymnasium at Aldershot had to serve, and something more ready-made than the expensive apparatus and contrivances with which that and other institutions are furnished had to be found. And it was quickly done. A visitor to Blackheath, drawing near to Greenwich Park in those days, would witness a startling and entertaining spectacle. A new use had been found for the bars which, in peaceful times, protect the lawns from the encroaching public. Here were admirable ready-made substitutes for the usual parallel bars! Here Kitchener's men became gymnasts, here they discovered what muscular development entailed. A man with sufficient courage to walk up to the mouth of a cannon would retire baffled and discouraged by reason of flabby muscles and stiff joints because of inability to perform balancing feats on a bar. He would flounder ignominiously on mother earth like an overturned fowl on the roadway; he would pick himself up, try again, and probably land on the crown of his head, to the delight of the interested spectators. When he had had as much as the instructor felt was good for him for the time being, he would be moved along elsewhere to undergo more gruelling.

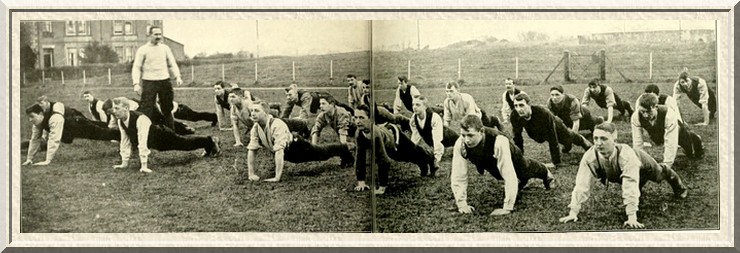

No apparatus this time; he was now to practise bodily contortions. He was invited to bend forward and outwards so that his hands could touch his toes or the ground. He had to follow the movements of his instructor in bending the trunk and neck backwards and forwards and sideways, this way, that way, and the next way, with endless variations and combinations of such-like exercises. Look at the illustrations of these exercises in this work, you men of civilian habits who have not joined Kitchener's army, and try what you can do.

—Photograph 62— The interior of the sergeants' mess at Grey Towers, Hornchurch.

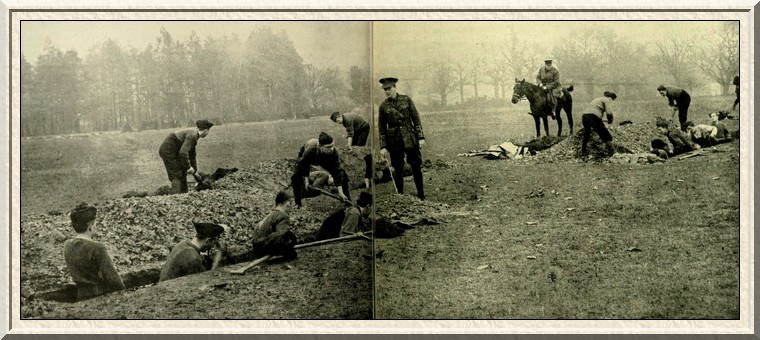

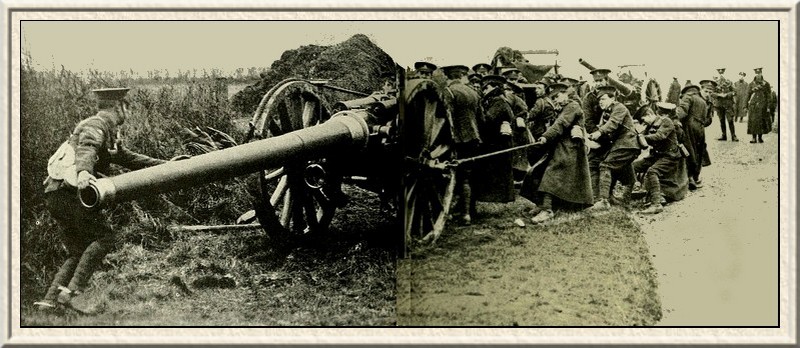

And this was only a small part in the training to develop the men's physique. The Army instructors mostly aimed at physical drill which could be carried out without any apparatus whatever. There was running drill, there was the marching, there was (later) bayonet exercise (a fine muscle- developer), trench digging, and so on.

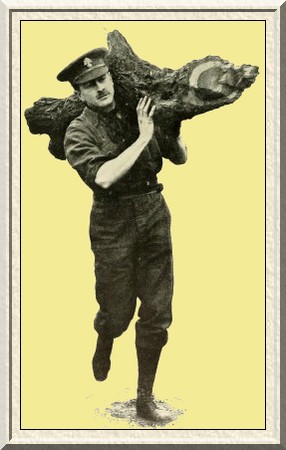

—Photograph 63— Private C. Armstrong, a Cambridge Blue, carrying a useful log for the fire.

In these early days the men who simply could not master the rudiments of their work from sheer weakness were treated with the greatest of leniency. One day the instructor noticed (hat a man lying at the far end of the line did not raise his legs as the rest of the squad were doing, and, thinking the man was exhausted, he did not admonish him. After ten minutes passed and the man was still lying on his back, the instructor walked to where the man lay—he was fast asleep.

"Where the dickens do you think you are?" asked the wrathful N.C.O. "Staying a week-end at the Ritz?"

"I was dreaming, Sergeant," replied the apologetic recruit.

"Do you think you'll beat the Germans by dreaming?" demanded the exasperated officer.

"That's just what I was dreaming!" replied the recruit triumphantly. "If you hadn't woke me up, the blooming war would have been over!"

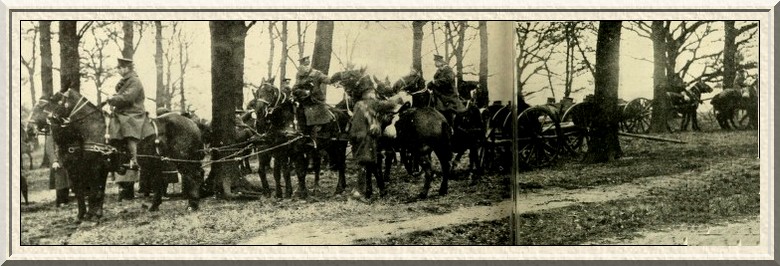

—Photograph 64— Awaiting the sergeant's command— men of the Royal Artillery ready for a trial of strength.

It was just about this time, when these methods of developing his bodily fitness became part of his daily life, that the new recruit began to commune with himself on the subject of the exactions the military life made on his physical endurance. Every new experience widens a man's outlook. He began to understand that the erect carriage, the steady step, the perfect balance and bearing of the men of a crack corps, is the outcome of much labour and training.

The very man who, in his civilian days, had taken pride in his supposed strength, and gloried in his elegant physique, was now confronted with humiliating experiences. Compared with the standards of endurance he had now to face, he had to admit to himself that his physical fitness was not so much to boast of after all. Watching his instructor raising himself upon his hands or, stretched on his back, lifting his stiffened legs until his extended toes were pointing to the blue heavens above—and all without any perceptible effort, the learner groaned to think he would have to follow the lead of the instructor to the bitter end.

For the amazing sergeant could go through all this a couple of dozen times. Not so the quaking recruit. After a second or third attempt his poor arms were aching, his legs groggy, and his nerves a bit wobbly. It was an embarrassing revelation to him; he learned for the first time of the lazy muscles which had never been called into play, of idle do- nothings that all his life had evaded their responsibility. In other words, he realised he had muscles in his body which he had never dreamt of. The discovery at first troubled him, and then braced him to further effort, enjoyed with growing relish.

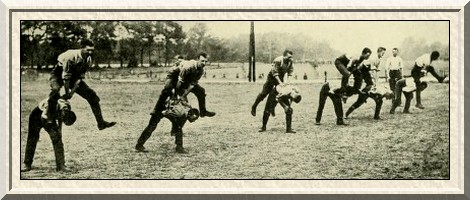

—Photograph 65— Kitchener's men at Aldershot at leap-frogging, an exercise which forms a part of their physical drill.

—Photograph 66— In the Footballers' Battalion many of the first-class players have enlisted, and they are as keen on getting fit for the field of war as they were for the field of play.

He quickly saw, too, what it was all leading up to—this physical drill, designed not merely to keep the men fit and well, but because it was necessary before a recruit could even begin to become an efficient soldier that his physique should be developed beyond the conditions in which the examining officer found it. It was all arranged to build up the physique necessary for the soldier life.

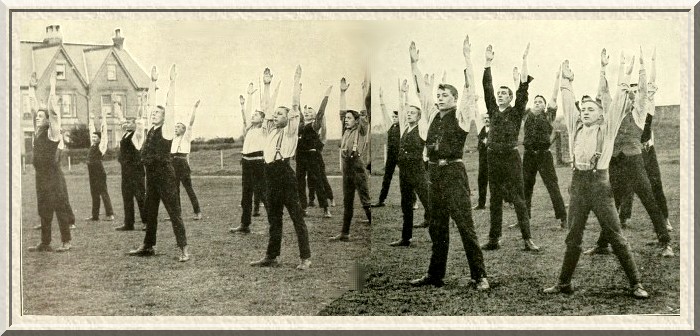

The physical training aimed at the co-ordinination of the body and nervous system; thus only can all-round fitness, muscular development, and stamina be acquired. Mothers and fathers of the young recruits were soon to see for themselves transformations were effected in their sons by this training by Swedish exercises in the open air, by the severe drilling, and by moral and physical discipline. The change was wonderful. A notable instance was one regiment, every member of which, after a few weeks' training, had to be measured for a new uniform, having outgrown the old.

—Photograph 67— The Footballers' Battalion training at the White City, London.

What Other Squads Were Doing

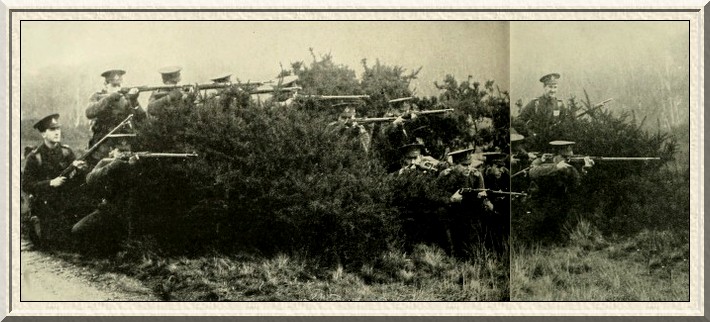

Whilst this physical drill was proceeding, a more advanced squad was elsewhere learning the more interesting part of the soldier's work. The supply of rifles in the early days was quite insufficient to arm the enormous numbers of recruits which were coming in. Some battalions, more fortunate than others, had sufficient rifles, at any rate, for the older recruits.

It was indeed a joyous day when the young soldier was regarded as sufficiently advanced in his profession to be entrusted with a rifle, and fell in upon parade to learn something of this strange instrument which was placed in his hands. He was asked the inevitable question :

"Why is the rifle placed in the hands of the soldier?" and, after a moment's thought, he answered, as inevitably :

"To protect my life."

The gorgeous opportunity, seized by successive generations of drill instructors, was once again snapped up.

"Your life," replied the instructor, with fine scorn, "who on earth bothers about your life? The rifle, my lad, is placed in your hands for the destruction of the King's enemies."

And that was the first lesson the recruit was taught, a real lesson of war; the first hint he received of the grim task which was his. There was never a recruit yet who did not carry away from that first instructor's drill a new sense of his responsibility to the State.

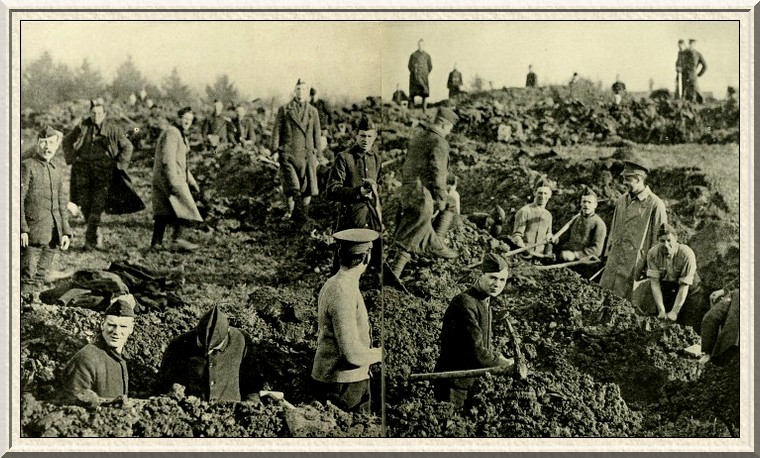

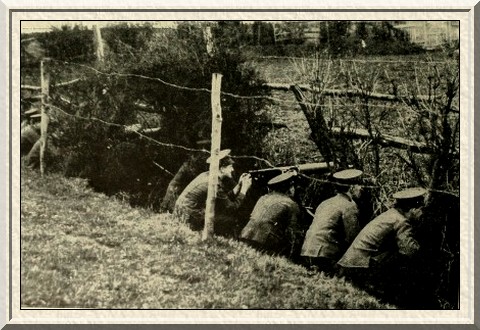

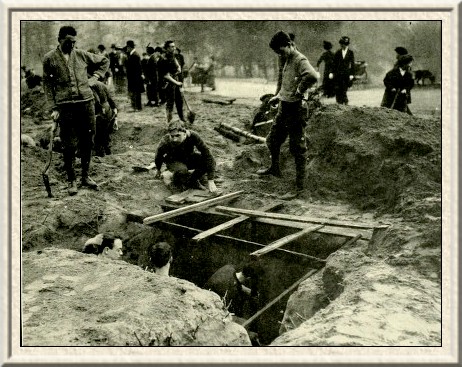

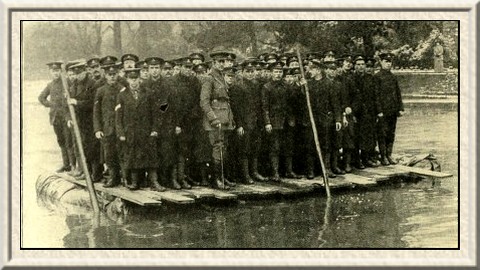

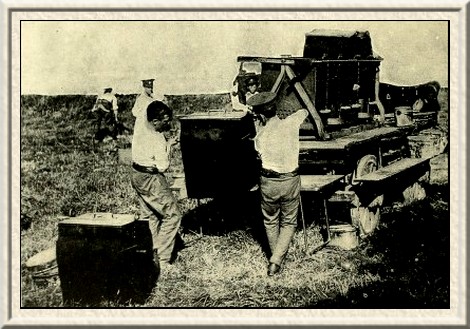

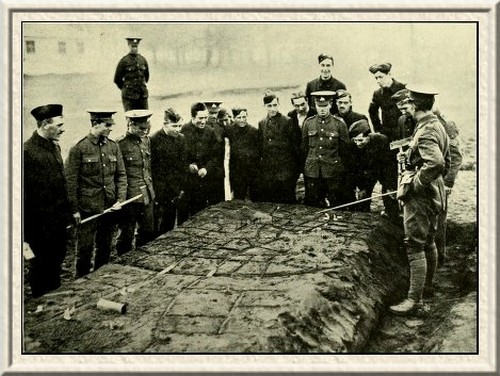

—Photograph 68— The Pioneer Battalion of Kitchener's Army (8th Battalion Oxfordshire and Bucks Light Infantry) trench-digging on the outskirts of Oxford.

The rifle is a strange instrument to handle. There are certain rites and ceremonies associated with its possession and carriage which the recruit had to learn. When for the first time he heard the command "Stand at ease," and then "Stand easy," what was more natural than that he should assume the attitude which, with the pictures beloved of youth still in his mind, he had come to think was not only natural but a little heroic? A watchful sergeant was ready to scorn this attitude. It was one which you may easily visualise.

The recruit would be standing legs apart, hands one over the other resting on the muzzle of the rifle. Now there are many reasons why a soldier should be forbidden to stand in this picturesque position; and in this particular case the reason was that, were the rifle by misadventure loaded, and, by a greater mischance, exploded, the recruit's hands, no less than any other portion of his person which came in the way of the bullet, would be shattered. The second (to the sergeant the important) reason is that the palm of the hand is inclined to perspire, and perspiration, which may get into the muzzle of the rifle, works such havoc as to drive the armoury sergeant mad.

Since the armoury sergeant is responsible for all the arms of the battalion, his point of view is of more consequence really than the view of the medical officer, who might be called upon to patch up all that remained of the too venturesome recruit.