a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: A History of Geographical Discovery in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Author: Edward Heawood. * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1305581h.html Language: English Date first posted: October 2013 Date most recently: October 2013 Produced by: Ned Overton. Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Production Notes.

Where noted, click on a map to enlarge it. The illustrations have been numbered. The font size of the Appendix has not been reduced.

CAMBRIDGE GEOGRAPHICAL SERIES

General

Editor:—F.H.H. GUILLEMARD, M.D.

FORMERLY LECTURER IN GEOGRAPHY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF

CAMBRIDGE

A HISTORY

OF

GEOGRAPHICAL DISCOVERY

IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

London: FETTER LANE, E.C.

C.F. CLAY, Manager

Edinburgh: 100, PRINCES STREET

Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO.

Leipzig: F.A. BROCKHAUS

New York: G.P. PUTNAM'S SONS

Bombay and Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd.

All rights reserved

LIBRARIAN TO THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY

Cambridge:

at the University Press

1912

Cambridge:

PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A.

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS

{Page v}

The period dealt with in this book lies for the most part outside what has been well termed the Age of Great Discoveries, and has in consequence met with less attention, perhaps, than it deserves. While the main episodes have formed the theme of many and competent writers, few attempts have been made to present such a connected view of the whole course of Geographical Discovery within the limits here adopted as might bring out the precise position occupied by each separate achievement in relation to the general advance of knowledge. It is this task which has been attempted in the present volume. The reasons which give a certain unity to the period are discussed in the following pages, but it may be briefly characterised here as that in which, after the decline of Spain and Portugal, the main outlines of the World-map were completed by their successors among the nations of Europe.

In dealing with so wide a field, both as regards time and space, the arrangement of the subject-matter presents considerable difficulties. To take the major portions of the world in turn, and trace the course of discovery for each from beginning to end, would, it was thought, lose much by failing to bring out what may be called the general perspective of the story. Successive periods were marked by more or less definite characteristics all the world over, and both the aims and methods of discoverers changed with the times. On the other hand a strict chronological arrangement of the whole material would have its own disadvantages, and a compromise between the two methods seemed to offer the only suitable solution. For each part of the world the whole epoch has therefore been broken up into periods, possessing a general unity in themselves, and sufficiently prolonged to escape the drawback of frequent interruptions of the story.

Whilst original sources of information have been consulted as far as possible, it is obvious, in view of the extent of the field, that this could not be done universally, in a text-book that does not, primarily at least, profess to present the results of original research. The contributions of so many previous workers in the field have been drawn upon that it is impossible to acknowledge the indebtedness in each separate case; more especially as the narrative is based on notes collected during a long series of years. A few of the more particular obligations must however find expression. Of earlier dates, works like Burney's classical collection of South Sea voyages, Southey's History of Brazil, Müller's and Coxe's accounts of Russian North-East voyages, and Barrow's History of Voyages into the Arctic Regions, have of course been consulted; while, of more recent times, Markham's Threshold of the Unknown Region, Ravenstein's Russians on the Amur, Parkman's and Winsor's historical works on North America, and Theal's on South Africa, Bryce's History of the Hudson Bay Company, Burpee's Search for the Western Sea, Conway's No Man's Land, Nordenskiöld's Voyage of the Vega, and many others, have furnished useful indications. The publications of the Hakluyt Society, with the valuable introductions supplied by the several editors, have also been an important source of information.

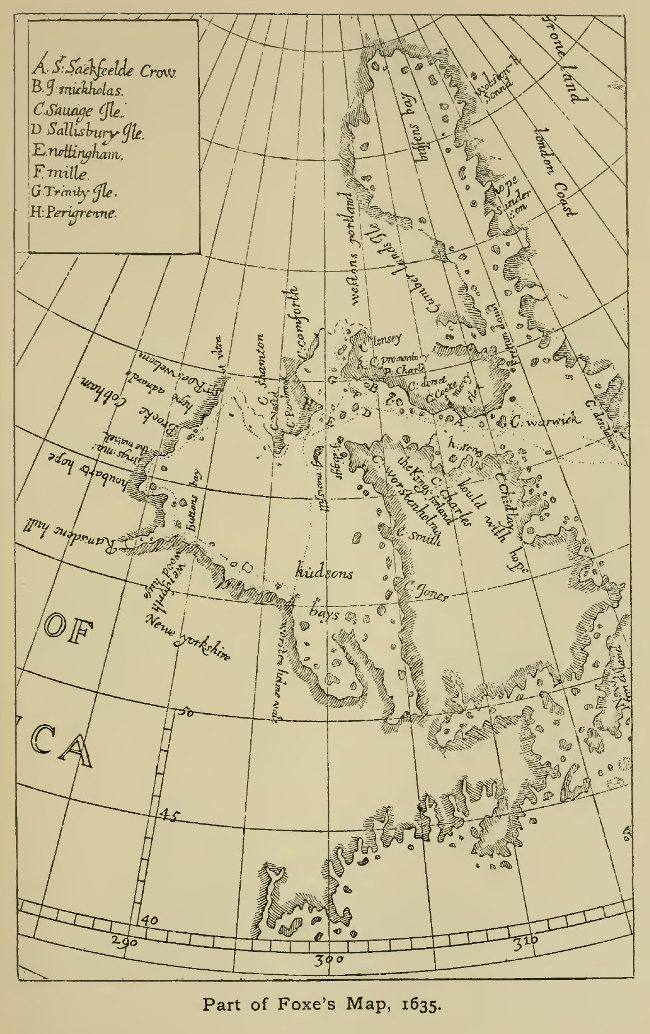

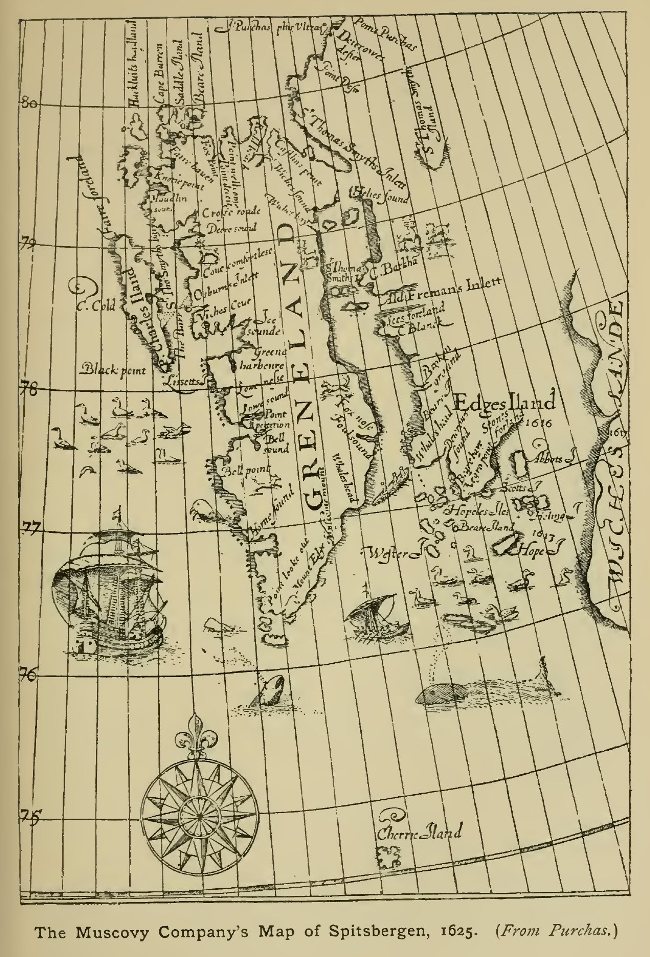

As regards the illustrations, special thanks are due to Mr Kitson, and his publisher Mr Murray, for permission to utilise the chart of Captain Cook's routes, and the portrait of the navigator, given in the former's Captain James Cook (which appeared, unfortunately, after the chapter dealing with Cook's voyages was written); to Sir Martin Conway for similar permission to use the reproduction of the Muscovy Company's Map of Spitsbergen given in his No Man's Land; and to Mr H.N. Stevens for supplying gratuitously for reproduction a facsimile of Foxe's Arctic Map. To Mr Addison, draughtsman to the Royal Geographical Society, I am indebted both for the actual drawing of the chart of Cook's routes, and also for useful advice in regard to the preparation of the other hand-drawn maps, for which I am myself responsible.

The Index has been made as complete as possible in the hope that it may serve as a guide, not only to the contents of the book, but also to sources of further information. Thus even where mere mention of a place is made in the present work, it is felt that the reference may be of use to students desirous of tracing the fortunes of such a place, or the course of European intercourse with it, in the narratives of the travellers themselves.

In deference to modern usage, such forms as Hudson's Bay, the Straits of Magellan, have been discarded, though at a certain expense of picturesqueness, and, in the second case, even of strict accuracy.

In conclusion, my warmest thanks are due to the Editor of the series, Dr F.H.H. Guillemard, not only for the great interest he has taken in the book from the outset, but for his unstinted aid in proof-reading, and for his many valuable suggestions, which have eliminated not a few inaccuracies.

EDWARD HEAWOOD.

1 SAVILE ROW, W.

August, 1912.

| INTRODUCTION | |

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | THE ARCTIC REGIONS, 1550—1625 |

| II. | THE EAST INDIES, 1600—1700 |

| III. | AUSTRALIA AND THE PACIFIC, 1605—42 |

| IV. | NORTH AMERICA, 1600—1700 |

| V. | NORTHERN AND CENTRAL ASIA, 1600—1750 |

| VI. | AFRICA, 1600—1700 |

| VII. | SOUTH AMERICA, 1600—1700 |

| VIII. | THE SOUTH SEAS, 1650—1750 |

| IX. | THE PACIFIC OCEAN, 1764—80 |

| X. |

RUSSIAN DISCOVERIES IN THE NORTH-EAST, 1700—1800 |

| XI. | THE NORTHERN PACIFIC, 1780—1800 |

| XII. | THE SOUTHERN PACIFIC, 1786—1800 |

| XIII. |

THE FRENCH AND BRITISH IN NORTH AMERICA, 1700—1800 |

| XIV. | SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE AMERICA, 1700—1800 |

| XV. | ASIA, AFRICA, AND ARCTIC, 1700—1800 |

| CONCLUSION | |

| SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES | |

| INDEX | |

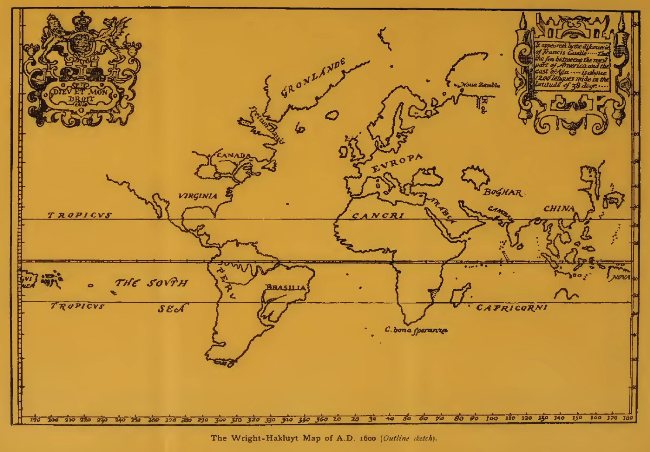

1. The Wright-Hakluyt Map of A.D. 1600. (Outline Sketch)

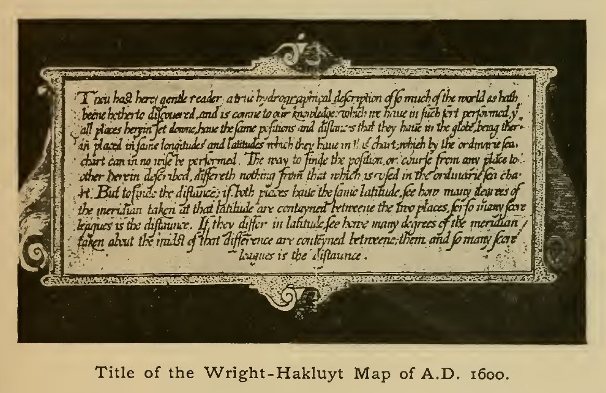

2. Title of the Wright-Hakluyt Map of A.D. 1600. (Facsimile)

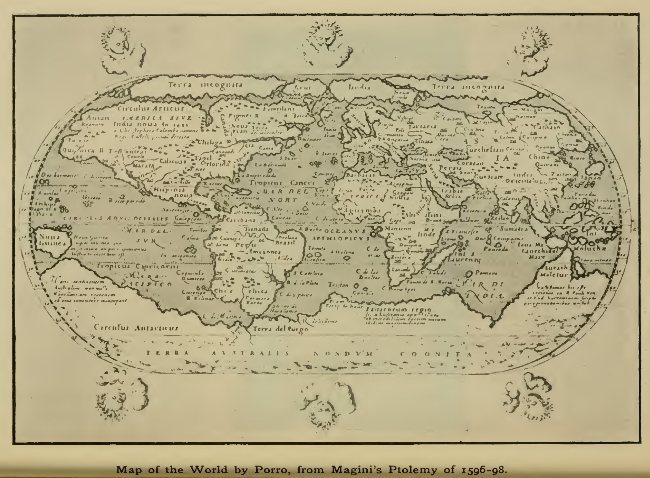

3. Map of the World by Porro, 1596—98. (Facsimile)

4. Novaya Zemlya, showing entrances to Kara Sea. (Sketch-map)

5. Boats' Adventure with a Polar Bear. From De Veer's narrative of Barents's Voyages. (Facsimile)

6. Part of Hondius's Map of 1611, showing Barents's Discoveries. (From the facsimile published by the Hakluyt Society)

7. Sir Martin Frobisher. From Holland's Heroologia, 1620

8. Hudson Bay and its approaches. (Sketch-map)

9. Part of Foxe's Arctic Map, 1635. From North-West Foxe

10. The Muscovy Company's Map, 1625. From Purchas his Pilgrimes. Reproduced from Sir Martin Conway's No Man's Land by permission of the author

11. Van Langren's Map of Eastern Asia. From Linschoten's Itinerarium, etc., 1595—96. (Outline Sketch)

12. Sir Thomas Roe. From the Portrait in the National Gallery

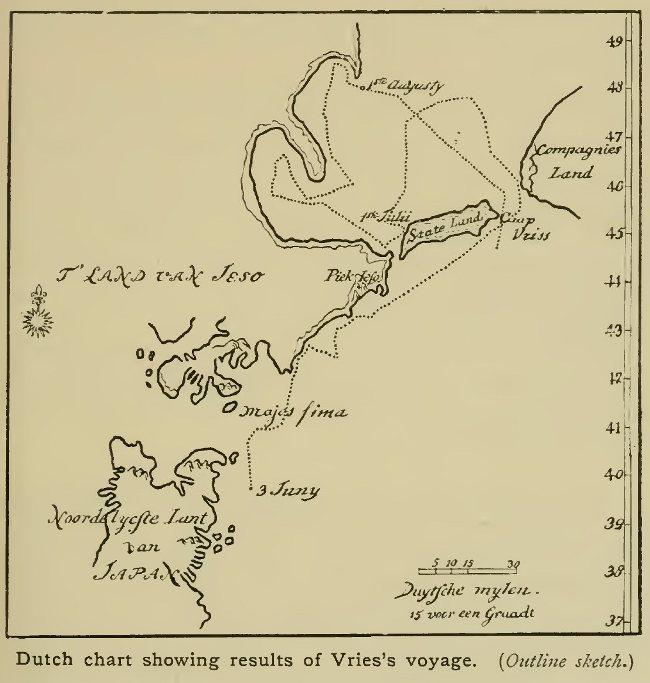

13. Dutch Chart showing results of Vries's voyage. From the copy in Leupe's edition of the voyage, 1858. (Outline Sketch)

14. Dutch Chart of Tasman's Discoveries. From the copy in Swart's edition of his Journaal, 1860. (Outline Sketch)

15. Samuel de Champlain. From Shea's copy of the portrait by Hamel (after Montcornet) in the Parliament House at Ottawa. (By permission of Mr Francis Edwards)

16. The Bison as figured by Hennepin. From his Nouvelle Découverte, 1697. (Facsimile)

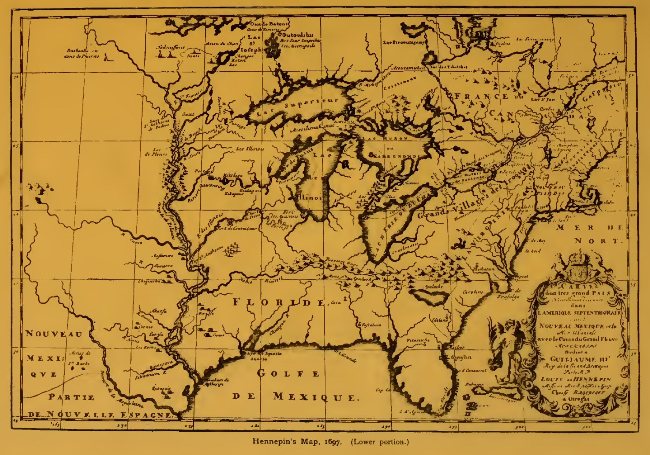

17. Hennepin's Map, lower portion. From his Nouvelle Découverte, 1697. (Facsimile)

18. Sketch-map of the Upper Amur Region

19. The Rhubarb of China. From Kircher's China Illustrata, 1667

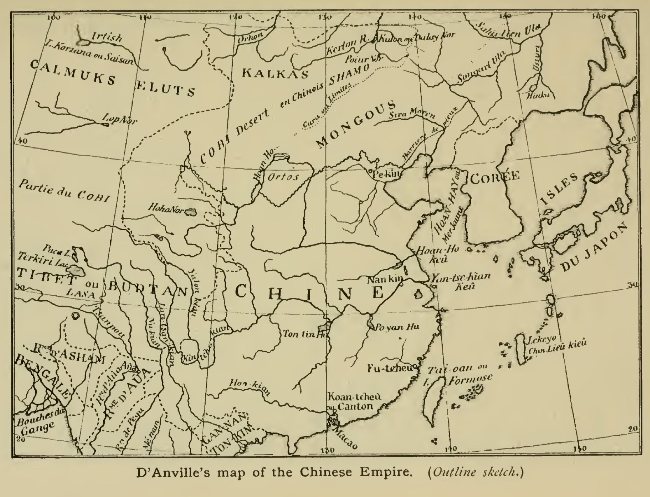

20. D'Anville's Map of the Chinese Empire. From his Atlas. (Outline Sketch)

21. Western Portion of Ludolf's Map of Abyssinia. From his Historia Æthiopica, 1681. (Facsimile)

22. Evolution of Central African Cartography in the 16th century. (Sketch-maps)

23. African Elephant. From Labat's Nouvelle Relation de l'Afrique Occidentale, 1728

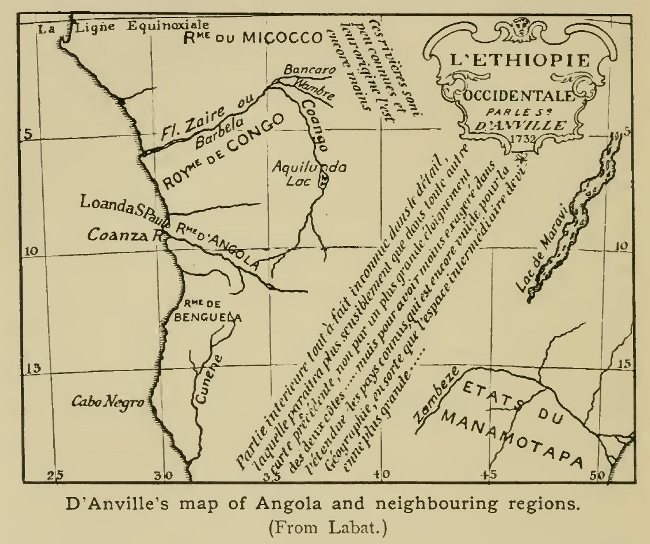

24. D'Anville's Map of Angola, etc. From Labat's Relation de l'Ethiopie Occidentale, 1732

25. The Galapagos, by Eaton and Cowley. From Hacke's Collection of Original Voyages, 1699

26. William Dampier. After an Original in the British Museum

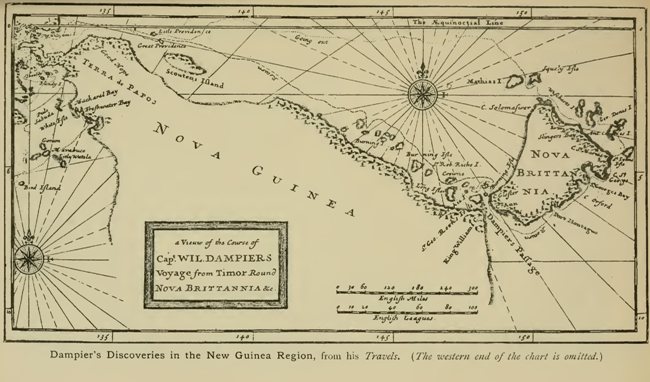

27. Dampier's discoveries in the New Guinea Region. From the chart in his Travels. (Facsimile)

28. Surrender of Tahiti to Wallis. From Hawkesworth's Voyages, 1773

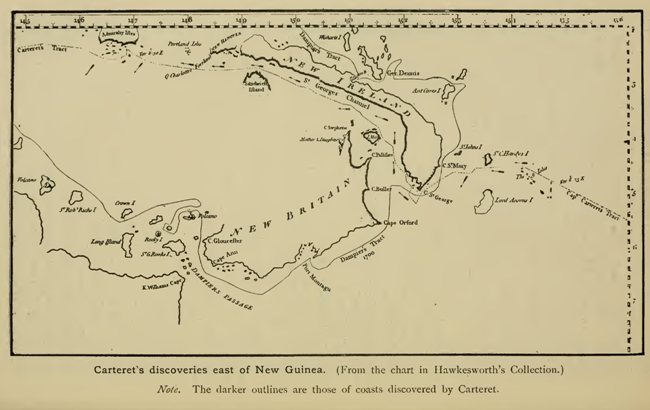

29. Carteret's discoveries East of New Guinea. From the chart in Hawkesworth's Voyages

30. Captain Cook. From a negative lent by Mr Murray of the Portrait in Greenwich Hospital; reproduced by permission of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty

31. Sir Joseph Banks. From the Portrait in the National Gallery

32. Cook's Chart of the East Coast of Australia. From Hawkesworth's Voyages. (Outline Sketch)

33. The Resolution. From a drawing in the possession of the Royal Geographical Society

34. The Resolution among Icebergs. From the narrative of Cook's Second Voyage

35. The Sea Otter. Drawing by Webber, in the narrative of Cook's Third Voyage

36. Cook's Routes. Based, by permission, on the Chart in Kitson's Captain Cook

37. Sketch-map of North-eastern Siberia

38. Sketch-map of North-western Siberia

39. The Bering Strait Region. From Müller's Map of 1754—58. (Outline Sketch)

40. Loss of boats at the Port des Français. From the Atlas to La Pérouse's voyage

41. La Pérouse's routes in the seas north of Japan. (Outline sketch of his chart)

42. Captain George Vancouver. From the Portrait in the National Gallery

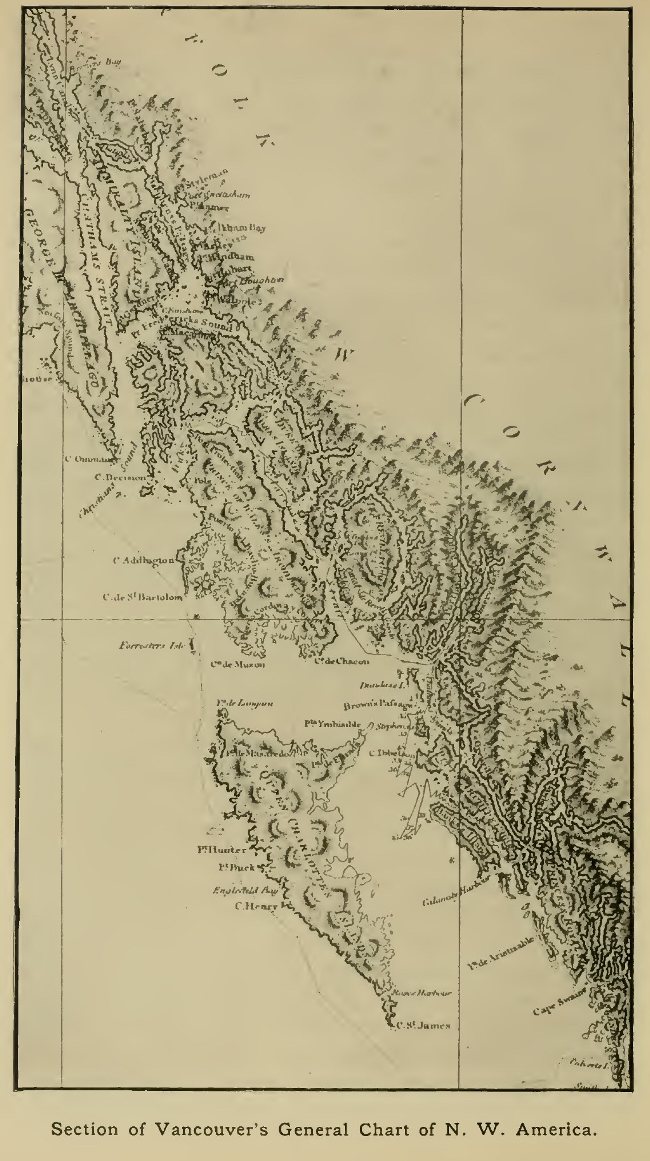

43. Section of Vancouver's General Chart of N.W. America. From the Atlas to his Voyage

44. Governor Arthur Phillip. From the Portrait in the National Gallery

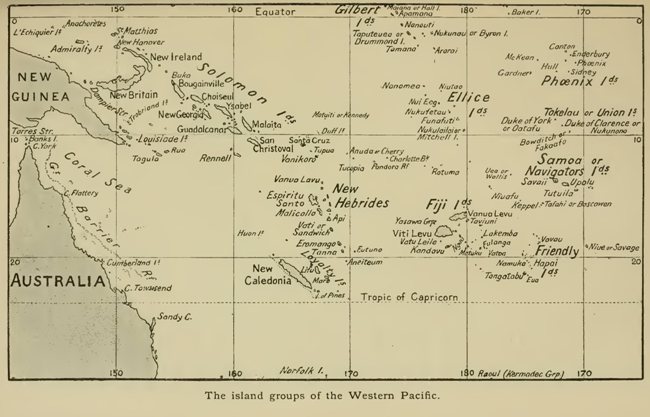

45. The Island Groups of the Western Pacific. (Sketch-chart)

46. Captain William Bligh. From the Portrait by Dance in the National Gallery

47. The Great Slave Lake in Winter. From Hearne's Journey to the Northern Ocean

48. Alexander Mackenzie. From the engraving by Condé, after Lawrence, in his Voyages

49. Western Portion of Mackenzie's Map, showing his routes. From his Voyages. (Outline Sketch)

50. Kentucky and its approaches. (Sketch-map)

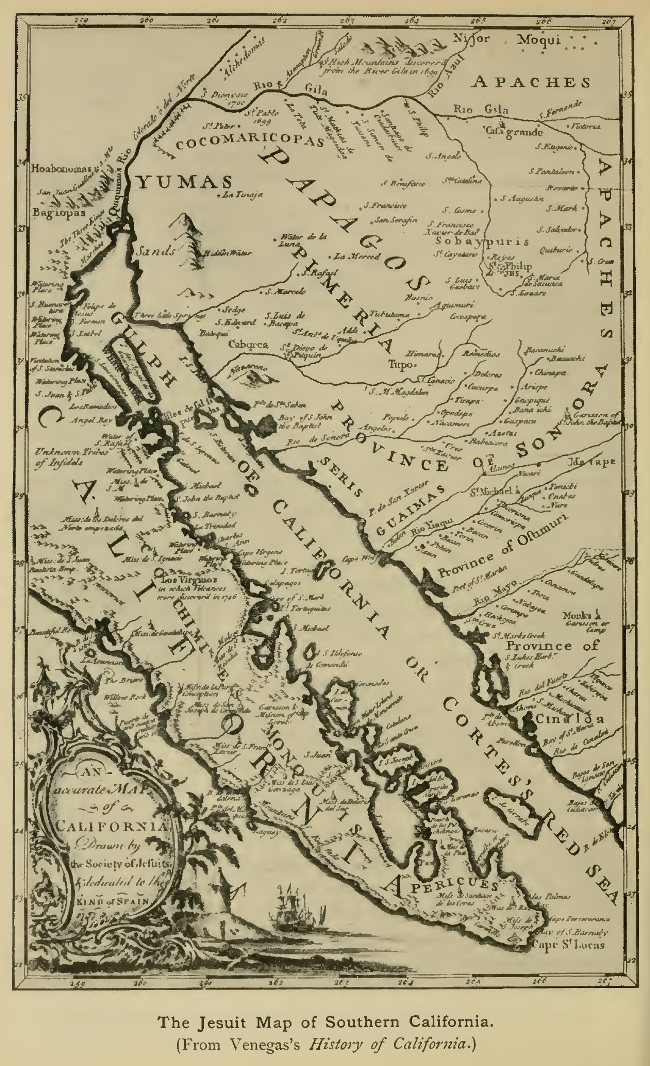

51. The Jesuit Map of Southern California. From Venegas's History of California. English edition, 1759. (Facsimile)

52. The Jesuit Map of Paraguay, by D'Anville. From the Lettres Édifiantes et Curieuses. (Outline Sketch)

53. Don Felix de Azara. From the Portrait in the Atlas to his Voyages

54. Renat's Map of Central Asia, 1738. From a facsimile in Petermanns Mitteilungen, 1911. (Outline Sketch)

55. View of Punakha, Bhutan. Sketch by Lieutenant Davis in Turner's Embassy

56. Carsten Niebuhr. From the Portrait in his Reisebeschreibung, Vol. III, 1837

57. James Bruce. From the Portrait in the National Gallery

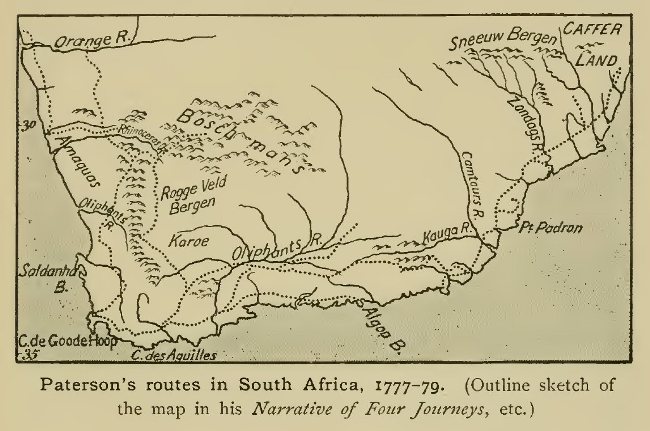

58. Paterson's routes in South Africa. From the Map in his Narrative of Four Journeys, etc. (Outline Sketch)

59. Constantine John Phipps, Earl of Mulgrave. From the Portrait in the National Gallery

{Page 1}

The closing years of the sixteenth century formed an important turning-point in the history of the world, and, as a natural consequence, in the more special field of geographical discovery also. A hundred years had elapsed since the great events which gave to the latter end of the fifteenth century its unique influence on the story of the nations—the discovery of America, and the first voyage to India round the Cape of Good Hope. During that interval Spain and Portugal, the pioneers in the new movement towards world-wide empire and commerce, had attained a degree of expansion unknown since the days of the Roman Empire, and, in virtue of the famous Bull of Pope Alexander VI, had practically divided the extra-European world between them. Fleet after fleet had been despatched from their shores, straining to the utmost the too scanty resources of the two nations, reinforced though they were by the riches of Peru, and the spices and other valuable commodities of the East. Meanwhile, other nations were standing forth as possible rivals, and the arrogant claims of Spain and Portugal to exclude all others from the world's commerce did but hasten the downfall of their supremacy.

In the hope of securing a share in the East Indian trade the English long expended their energies on fruitless efforts to open a route by the frozen North, though the bold exploits of Drake and others brought them into actual collision with Spain on the ground claimed by her as her exclusive property. Private adventurers also made their way to the East, but it was not until the nautical supremacy of Spain had been broken in 1588 by the defeat of the "Invincible Armada", that the equal rights of all to the use of the maritime highways were vindicated. It was, however, not the English, but the Dutch who were the first to avail themselves of the new opportunities. After the voyages of the Portuguese had made Lisbon the chief entrepot of the valuable Indian trade, Antwerp and Amsterdam rose to importance as centres of distribution of Indian goods over Northern Europe. Rendered desperate by Spanish oppression, the seven northern provinces of the Netherlands in 1580 declared their independence, and in retaliation Philip II, under whom the whole dominions of Spain and Portugal were then united, took the short-sighted step of forbidding the Amsterdam merchants to trade with Lisbon. Threatened with ruin, they were of necessity driven to more determined efforts to obtain an independent trade with the East, and though they too, for a time, made the mistake of searching for a northern route, they soon boldly resolved to enter into open competition with the Portuguese, and in 1595-96 the first Dutch fleet sailed for India. An English expedition had, it is true, made its way to the East in 1591, but it proved unsuccessful, and it was not until 1599 that systematic steps for a direct trade with India were taken by the formation of the English East India Company.

With the change thus brought about in the distribution of material power among the nations of Europe, it was natural that geographical discovery should also in future follow a different course. Whereas the great discoveries of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had been almost entirely the work of Spain and Portugal, with the beginning of the seventeenth the energies of both nations became suddenly paralysed, and after the first decade of the new century no more great navigators set sail from their shores. Their place was taken by the Dutch, French, and English; the Dutch especially—who, as already stated, had gained a start on the English in the matter of Eastern trade—leading the way, during the early part of the new period, in the path of maritime discovery. But although the French lagged somewhat behind, as compared with the Dutch and English, in the prosecution of Eastern enterprises, they were destined to play an important part in the exploration of the New World, especially in North America, to which their view had been directed from an early period, even in the sixteenth century. By a curious coincidence the Russians were simultaneously entering upon a new period of activity in the broad regions of northern Asia. It was to these four nations therefore that the principal work in completing the geographical picture of the world in its broad outlines was now to fall.

Before proceeding to describe the course of discovery under the new order of things, it will be well to take a rapid survey of the state of knowledge of the globe existing at the close of the sixteenth century, and of the ideas which then prevailed respecting the still unknown portions.

As regards the knowledge of the general distribution of land and water, a marked improvement had taken place during the latter half of the century. America, after the voyage of Magellan across the Pacific, had slowly taken its fitting place as an independent division of the land, being now regarded neither as an insular mass of comparatively small area, as had been supposed by the mapmakers of the opening years of the century, nor as stretching across the North Pacific in a comparatively low latitude to join the eastern parts of Asia, as had been shown on maps dating from the middle of the century. The idea of a narrow strait separating the two continents in the far north was already gaining ground, though based apparently on a quite insufficient foundation.

Much less had been done to clear up the uncertainties respecting the supposed Great Southern Continent, which had from very early times appealed to the imagination of philosophers, and the investigation of which was the most important piece of geographical work remaining to be done. Even before the voyage of Magellan, geographers had a strong belief in the existence of land beyond the southern ocean, and this was greatly strengthened by the passage of that navigator through the strait which bears his name, as it was naturally imagined that the land to the south of the strait formed part of a great continental mass. Whether or not the ancient and medieval geographers had to any extent based their ideas on vague rumours of Australia which may have reached the countries of southern Asia, is a question which cannot be answered; but it has been held with some show of reason that statements of Marco Polo, Varthema, and other travellers, point to a knowledge that an extensive land did lie to the south of the Malay Archipelago. It is an almost equally difficult matter, and one which concerns our present subject more nearly, to decide whether the indications of a continental land immediately to the south of the Archipelago, to be found in maps of the sixteenth century, were based at all on actual voyages of European navigators. The influence of the writings of former travellers and investigators is still seen in many of these maps. Thus the term "Regio Patalis", which occurs on many of the earlier maps as the designation of a southern land, is known to have been borrowed from early writers. In the maps of the Flemish school of cartographers—Ortelius, Mercator, and others—a continental land is vaguely shown, but the details respecting it are merely borrowed from Marco Polo. A special point, however, about these maps is that New Guinea is correctly shown as an island separated by a narrow strait from the main mass of land, although it is stated in one at least that their relation was still uncertain.

An apparently stronger argument for the view that Australia had been reached during the first half of the century is supplied by a series of manuscript maps by a French school of cartographers (of which the best known representative was Pierre Desceliers), the earliest possibly dating from 1530. They all show, immediately to the south of Java, and separated from it only by a narrow channel, a vast land bearing the name Jave la grande. The details inserted on the coast line, though fairly full, are of little use for purposes of identification; but from some slight resemblance of the contours to those of Australia, and from the vast size of the land portrayed, it has been held that the maps in question prove that an actual discovery had been made.

The unsupported evidence of these maps—which in other outlying parts of the world contain many hypothetical details—can, however, be hardly said to justify any positive conclusion, and it may even be possible that some rough sketch of Java (then commonly known by Polo's designation "Java major") may have been used to supply the outline and terminology of the supposed continental land.[1] However this may be, it is certain that such a discovery was not generally known, and we may consider that to all intents and purposes the work of exploration in this direction had to start from the beginning in the period with which we have to deal. Elsewhere, though vast tracts remained a blank on the maps, the work of discovery did not set out, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, with quite such a clear field. We will take the various quarters of the globe in order, and note briefly the extent of knowledge possessed at the time with respect to each, and the chief tasks still to be accomplished.

[1 The recently discovered Carta Marina of Waldseemüller (1516) has a representation of Java which may be regarded as a first step towards the Great Java of the French maps.]

The extensive exploration of Europe may be said to have been completed by the close of the sixteenth century. Such fantastic forms as had been given to the northern parts of the continent, including the British Islands, in maps of the early part of the century, and even in the famous map of Olaus Magnus of 1539 (though this showed a great improvement on its predecessors), had given place to more correct outlines, thanks principally to the English voyages of Willoughby, Chancellor, Burroughs and others, and the Dutch voyages of Nai, Tetgales, and Barents in 1594-96. The copies of Barents' own map, published at Amsterdam in 1599 and 1611, show well the advance that had been made in the previous half-century (see p. 26). Russia too, though still imperfectly known to the rest of Europe, had been rescued from the obscurity hitherto enveloping it by the work of Von Herberstein (1549), as well as by the travels of Giles Fletcher, Queen Elizabeth's ambassador to the Czar (1588), and of Anthony Jenkinson and other agents of the British Muscovy Company.

The knowledge of Asia attained before the end of the sixteenth century may be considered under three heads. Firstly, that acquired by medieval travellers before the voyage of Vasco da Gama; secondly, that due to the voyages of the Portuguese and others by the sea route to India; and thirdly, the somewhat vague information respecting northern Asia acquired by Russian and Finnish merchants and voyagers during the course of the century. The first of these sources had supplied more or less detailed information respecting the whole of Asia south of Siberia, but the absence of accurate maps or scientific description caused much confusion of ideas with respect to it. For the southern and south-eastern countries, especially the coast-lines, this information was now superseded by the results of recent voyages, though, as we have seen, the statements of the early travellers continued to exercise a powerful influence with map-makers and cosmographers in Europe, if not with the voyagers themselves. For the whole of Central Asia, however, as well as the interior of China, the writings of Friar Odoric, Willem de Rubruk, Marco Polo, and the early missionary friars, remained the only sources of knowledge, and could at best present a most imperfect picture of those vast regions. In the south and east the Portuguese voyages (recorded in the history of De Barros and the poems of Camoens) had before the close of the sixteenth century re-opened to the world a knowledge of the whole coast-line as far as the north of China and the Japanese islands. The greater part of the Malay Archipelago had become well known, including the northern coasts of New Guinea: but whether the southern coast of the great island had been explored is uncertain, the statement by Wytfliet that a strait existed between it and a land to the south being possibly based only on Mercator's theoretical representation. Some information had also been supplied regarding the various kingdoms of India and Indo-China by the travels of Duarte Barbosa, Caesar Frederik, Gasparo Balbi, Ralph Fitch, Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, and others, some of these having reached India overland, and thus contributed to a better knowledge of the countries of western Asia. The extensive travels of Fernão Mendez Pinto, though not published till the beginning of the next century, were carried out during the sixteenth, and, in spite of much exaggeration on the part of the traveller, threw considerable light on the state of the East in his time. Lastly, in Northern Asia, the newly awakened enterprise of Russian and other merchants had begun to make known the western parts of Siberia, including the coasts of the Arctic Ocean as far as the mouth of the Yenesei. The state of knowledge of this region at the beginning of the new century is shown by the map by Isaac Massa published in Holland in 1612. But the great advance of fur-hunters and of others across the wilds of Siberia was only just beginning, and the discovery and conquest of that vast region belongs almost entirely to the period dealt with in the following pages.

In Africa, the end of the sixteenth century marks the close of a period of activity, to be followed by nearly two centuries of stagnation, so far as geographical discovery is concerned. The entire coasts were of course known, and in places, such as Benin, the acquaintance with the lands immediately in their rear was closer than was the case in our own times until quite recent years. There is no doubt, too, that some knowledge of the interior was possessed by the Portuguese at the time we are treating of, though to determine exactly the extent of that knowledge is a task of great difficulty, if not impossible, with the limited material we now possess. From the fact that maps of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries show the African interior filled in with lakes and rivers such as are now known to exist there, it has even been imagined that the Portuguese of those days possessed an intimate knowledge of Central African geography, rivalling that due to the explorers of the nineteenth century. It is necessary briefly to examine the basis of this idea, which we shall find a very unsubstantial one. The earlier cartographers of the sixteenth century (Waldseemüller, Ribeiro, and others) merely followed Ptolemy's account, and made the Nile rise from two or more lakes lying east and west a long way south of the Equator. In course of time, however, the vague information gleaned by the Portuguese on the east and west coasts seems to have been combined with the older conjectural geography. From Congo and Angola on the west, and Mozambique, Sofala, and Abyssinia on the east, rumours of lakes and empires reached the ears of travellers, and when these were put down on the maps with considerable exaggeration of distances, the whole interior became filled with detail, and names heard of from the opposite ends of the continent became confusedly mixed in the centre of it. The maps of Mercator (1541 and 1569), Gastaldi (1548), Ramusio (1550), and Ortelius (1570) are among the earliest examples of this type, all showing the Nile as rising from two great lakes lying east and west, south of the Equator. The well-known map of Filippo Pigafetta (1591), based on the accounts of Duarte Lopez, was evidently evolved in much the same way, though the lakes there appear north and south of each other. In all these maps the greater part of the geography represented is unmistakably Abyssinian (see sketches on p. 150).

In other quarters the knowledge of the Portuguese was probably confined to the districts closely adjoining their colonies of Angola, Mozambique, and Sofala. Behind the two last named, expeditions had been pushed to a considerable distance, and Portuguese envoys had reached the country of the celebrated chief known as the Monomotapa, south of the central Zambezi. The power of this potentate became greatly exaggerated and he was supposed to rule over an empire equal to those of Asiatic monarchs. The Portuguese writers were acquainted with the famous ruins at Zimbabwe, which place the Jesuit priests are even supposed to have visited; but this appears doubtful, as the name Zimbabwe was then applied to the residence of any important chief. The gold-producing region of Manica had certainly been visited before the end of the sixteenth century, and ruined forts now existing prove that the Portuguese occupation extended to the Inyaga country, a little further north, and was not confined to the Zambezi valley. On that river itself their knowledge seems to have extended about to the site of the present post of Zumbo, at the confluence of the Loangwa.

In South America, discovery had made vast strides during the century following the first arrival of white men. Within the first 50 years the whole contour of the coasts had been brought to light, though as the passage round Cape Horn had not been made before the close of the century it was still supposed by some that Tierra del Fuego formed part of a great southern continent. Before the new century began, the range of the Andes, with the important empires occupying its broad uplands, had been made known by the conquests of the great Spanish captains, while explorers of the same nation had also traced the general courses of the three largest rivers of the continent. By the voyage of Orellana in 1540-41, followed twenty years later by that of the tyrant Aguirre, almost the whole of the course of the Amazon had been laid down. In the system of the Plata the Spanish governors Mendoza and Alvar Nuñez had ascended the Paraguay, penetrating almost to the frontiers of Peru, besides forcing a way from the coast to the upper Paraná. Of the Orinoco, the shortest of the three, less had been explored, as the cataract of Atures had turned back more than one adventurous voyager. Its western tributary, the Meta, had, however, been ascended for some distance, and the wide plains at the eastern foot of the Andes of New Granada, about which our information is even at the present day far from perfect, had been traversed again and again by searchers after the fabulous city of "El Dorado"—the Golden Monarch. These included German adventurers like Georg von Speier, Nicholas Federmann, and Philip von Huten, as well as Spanish captains like Hernan Perez de Quesada and Antonio de Berrio. Under the latter the site of the city changed its locality, and the southern tributary of the Orinoco, the Caroni, became the imagined channel of access to its fabled lake; but little success attended his efforts to penetrate in this direction. Nor did much increase of knowledge result from the voyages of Ralegh and other Englishmen to the same regions. In spite of all this activity vast tracts of forest, especially in the Amazon basin, remained unexplored, and the whole southern extremity of the continent was entirely neglected whilst, even where travellers had penetrated, the geographical knowledge obtained was often of the vaguest, and imaginary delineations of lakes and rivers long filled the maps.

In North America much less progress had been made in the work of discovery. While the coasts facing the Atlantic up to the threshold of the Arctic regions had gradually been surveyed by voyagers of various nations, and a few had pushed up the remote Pacific coasts as far as Lat. 42° N., the whole of the northern and north-western shores—the former by reason of their icy barrier, the latter because of their distance from Europe—still remained unknown, though, as already stated, ideas of the existence of a strait separating north-west America from Asia began to be current about this time. The whole of the northern and central interior, too, remained a blank on the map, and only on the confines of the Spanish viceroyalty of Mexico had any progress in land exploration been made. The example of the wealth of Mexico had led adventurers to roam the wide plains of the southern United States in search of fortune, and the expeditions of De Soto, Coronado, and others had made known something of the lower Mississippi and its tributaries, and of the more western regions up to the Grand Cañon of the Colorado. But the absence of rich empires in this direction soon caused these efforts to be abandoned. In Florida, unsuccessful attempts at a settlement had been made by French protestants, and further north, in Virginia, the first beginnings of the English settlements destined to grow in time to such vast proportions were in existence. Still further north, off the coasts of Newfoundland, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and English ships frequented the banks in large numbers for the sake of the fishery, and the French under Cartier had already led the way in discovery by the ascent of the St Lawrence beyond the present site of Quebec, soon to be the scene of colonising efforts on the part of their countrymen. A wide field for discovery was thus open in eastern North America, and the coming century was to witness a well-sustained activity, leading to a great enlargement of the bounds of geographical knowledge.

In the wide domain of the Pacific Ocean much remained to be done, though fairly correct ideas as to its nature and extent had become current. Since the voyage of Magellan many Spanish navigators had crossed from the coast of America to the islands of the Eastern Archipelago, to which this was their regular route, owing to the division of the world between Spain and Portugal, the return voyage being made across the North Pacific in fairly high latitudes. From Callao in Peru Mendaña had twice crossed the ocean in about 10° S., discovering the Solomon and Santa Cruz groups and supplying apparent confirmation of the ideas then current as to the existence of a southern continent. On the second voyage he had been accompanied by the celebrated navigator Quiros, whose own chief work fell within the new century, and will be dealt with in the following pages. Other Spanish navigators had crossed the ocean north of the Equator from Mexico to the Philippines, and it has been supposed that Gaetano—the pilot who accompanied one of these, Villalobos, in 1542—afterwards made a voyage to the Sandwich Islands. But this discovery, if made, was carefully kept secret, and had no influence on the subsequent history of Pacific exploration. The Englishmen Drake and Cavendish had likewise crossed the Northern Pacific, and just at the close of the century the Dutch expedition under Van Noort had followed in the tracks of Magellan and for the fourth time effected the circumnavigation of the globe—but this belongs rather to the new than to the old period. In most of these voyages certain definite routes had been followed, which missed many of the most important groups of islands. The information brought home with respect to those seen was very vague and fragmentary, and for the most part they can with difficulty be now identified. Both in the north and south, vast expanses of ocean remained untraversed, and the exploration of these, especially in the south, was one of the principal tasks of the coming century.

The Wright-Hakluyt Map of A.D. 1600 (Outline

sketch).

Click on the map to enlarge it.

In the Arctic regions some advance had already been made before the close of the sixteenth century, the new period having in fact been ushered in by the early enterprise of the English and Dutch in this quarter, from about 1550 onwards. In dealing with this part of the world it will be advisable to go back to about that date, so as to give a more connected account of the progress achieved; and it is unnecessary to enter into the subject here.

Title of the Wright-Hakluyt Map of A.D. 1600.

The state of knowledge respecting the world in general at the close of the sixteenth century is well shown by the map prepared under the superintendence of Edward Wright, the Cambridge mathematician, to whom the projection now known as Mercator's is held to be really due. This map, finished in 1600, and sometimes found inserted in the edition of Hakluyt's famous collection of voyages completed in that year, is the earliest English example of that projection. It differs from many maps of the time in its careful discrimination between actual discovery and conjectural geography, the latter being almost entirely excluded. Thus no trace is seen of the hypothetical southern continent, apart from a slight indication of land in the position of northern Australia. The recent Arctic discoveries are well shown, and it has been thought that John Davis had some share in its preparation. The strait which bears his name is correctly drawn, as well as the discoveries of Barents in Spitsbergen and Novaya Zemlya. In the Far East, too—whence, as we shall see later, Davis had recently returned—the map gives a very correct representation of the Archipelago, Japan, etc. North of the Pacific a wide blank occurs between the coasts of Asia and America, the conjectural connection between the two, and the equally doubtful Strait of Anian shown on so many maps of the period, being alike omitted. Another type of map, current about this time, is represented by that of Ortelius, a reduced copy of which, prepared by Girolamo Porro for Magini's Ptolemy of 1596, is here reproduced from the Italian version of 1598. It will be noticed that the supposed southern continent here takes a prominent place.

Map of the World by Porro, from Magini's Ptolemy of

1596-98.

Click on the map to enlarge it.

{Page 14}

In the remarkable outburst of maritime enterprise which followed the discovery of America, it was the equatorial regions, with their real or supposed wealth in the precious metals and other valuable commodities, which above all stimulated the energies of such nations as, by their political influence or favourable geographical position, had been called upon to take part in these adventures. But, side by side with this principal current of activity, there had begun to flow, in the course of the sixteenth century, a subsidiary stream of enterprise in the direction of the inhospitable North—a stream which, though at first but feeble in comparison, was destined to lead to results of great importance for the widening of the geographical horizon. And as it was the more southern peoples of Western Europe who had gained the chief glory and profit from the earlier quest, so it was the hardy seamen of the north who, as an equally natural result of geographical position, carried off the laurels in the still more arduous task of seeking new routes through the frozen Arctic seas.

The first beginnings of enterprise in this direction belong to still earlier times than the search for a route to the Indies, and are in fact to a great extent lost in obscurity. Long before the Venetian and Portuguese navigators began to venture into the unknown wastes of the Atlantic, the seamen of the north had carried out voyages unsurpassed for their daring even by the more fruitful exploit of Columbus. Before the end of the tenth century the most northern point of Europe seems to have been rounded by Other in the voyage narrated by him to our King Alfred, while in the following century the Norsemen (who had already colonised Iceland) found their way to the distant shores of Greenland, where, according to the story, two separate settlements were founded and existed for some centuries. They even appear to have reached some part of Eastern Canada or Newfoundland. The supposed voyages of the Venetian noblemen, Niccolo and Antonio Zeno, in the fourteenth century, have been proved almost with certainty to have been mainly, if not entirely, fictitious; but that some glimmering of knowledge of these northern regions was possessed by the cartographers of the following century is shown by various maps that have come down to us, especially that of Claudius Clavus, the "earliest cartographer of the North." The rising spirit of maritime adventure found its first outlet in England in the voyages of the Cabots, father and son, though those of Sebastian, the son, have not yet been satisfactorily elucidated, and the idea once held that they reached as far north as the mouth of Hudson Strait rests on no sure foundation. The arguments put forward by Robert Thorne in 1527, as to the feasibility of a north-west passage, led to no immediate result, and it was some years later that the English merchants took the first important step towards securing a share in the benefits of distant trade, from which the jealousy of their continental rivals had hitherto excluded them.

Mainly through the agency of Sebastian Cabot, an association was formed for "the discovery of lands, countries, and isles not before known to the English", and this received a royal charter in 1549.[1] At this time the thoughts of the merchants were directed chiefly to the opening up of trade with the East by way of Northern Russia, and for this purpose an expedition of three ships was fitted out in 1553 and despatched under the command of Sir Hugh Willoughby, with Richard Chancellor as "pilot-major." It was furnished with "letters missive" from King Edward VI to the potentates of the regions likely to be visited, and sailed from Ratcliffe on the Thames, full of high anticipation, on May 10, 1553. But it was doomed to meet with disaster. After sailing along the coast of Norway the ships encountered boisterous weather, and two of them, the Bona Esperanza and Bona Confidentia (the former Willoughby's own ship), were driven hither and thither, and though they sighted land in the latitude of 72° (probably on the south-west coast of Novaya Zemlya), were finally forced to take refuge in the haven of Arzina [2] in Lapland, where the whole of the crews perished miserably of cold and hunger. The third ship—the Edward Bonaventure, with Chancellor for captain, became separated from the others and succeeded in reaching the mouth of the Dwina in the White Sea, whence Chancellor and some of his companions travelled inland to Moscow, and were well received by the Emperor Ivan Vassilivich, thus paving the way for future trade relations between Great Britain and Russia. On his return Chancellor wrote a short account of the country and the manners and customs of its people—the earliest first-hand information on the subject which reached this country. He was drowned when returning from a later voyage in 1556.

[1 In the successive charters granted to this association of merchants, the title given to it varies considerably, giving rise to some confusion. It was for a time most generally known as the "Company of Merchant Adventurers", but this gave place in an act of parliament of 1556 to "The Fellowship of English Merchants for Discovery of New Trades", while the more commonly used title was that of the Russia or Muscovy Company.]

[2 The Varzina river debouches on the north side of the Kola peninsula in about 38½° E. It is already shown on Ortelius's map of Europe.]

In 1555 a second voyage was made, and trade definitely established, while in 1556 the Company despatched Stephen Burrough, in the pinnace Searchthrift, to explore still further east in the direction of the river Ob. Burrough reached Vaigatz Island on July 31, and soon afterwards entered the Kara Strait between that island and Novaya Zemlya, which has been sometimes known, from him, as Burrough Strait. He was unable however to advance any distance into the Kara Sea, but turned back on August 5, wintering at Kolmogro at the mouth of the Dwina.

Novaya Zemlya, showing entrances to Kara Sea.

The success of the trade with Russia diverted the energies of the merchants from the search for a north-east passage for some years, and it was not until 1580 that any serious attempt was made to prosecute discovery in this direction, attention having meanwhile been once more directed to the north-western route. Yearly voyages were however made to Kolmogro, and agents were regularly established in Russia to buy up commodities in readiness for the arrival of the ships, while some made their way on behalf of the Company as far as Persia and Central Asia. Hakluyt prints the commission issued in 1568 (given as 1588 by a misprint) to three servants of the Company—Bassendine, Woodcocke, and Browne—to explore eastwards beyond the Pechora, but nothing is known of the result. In 1580 the Company determined to renew their efforts for the discovery of a north-eastern route to Cathay, and commissioned two captains, Arthur Pet of Ratcliffe and Charles Jackman of Poplar, to sail for that purpose, in the barks George and William of London, the former of 40, the latter of 20 tons only. In spite of the ill-success of Burrough's attempt, it was still hoped that by passing through the strait between Vaigatz and Novaya Zemlya, a passage might be found to China in a generally eastward direction, as indicated on a chart which had been drawn by William Burrough. With our present knowledge of the difficulties to be encountered—difficulties so great that the wished-for passage was not made until three centuries after Pet and Jackman's time—we can only wonder at the sanguine spirit which regarded it as possible that China could be reached, in the small and frail vessels employed, during the same summer in which they set out, or at worst after one winter had been spent on the northern coast of Asia.[1] It was only in case the land should be found to extend to 80° N., or even nearer the Pole, that the impossibility of the passage was thought probable. In such a case, after as much of the coast as possible had been explored during the first summer, the explorers were recommended to winter in the Ob, and ascend it the next summer to the "City of Siberia." In any case all possible care was to be taken to enter into friendly relations with the inhabitants, and lay the foundations of future trade. A point to be specially kept in view, either on the outward or return voyage, was the examination of "Willoughby's land", and its relation with Novaya Zemlya. Notes for the guidance of the voyagers were also supplied by William Burrough, Dr Dee, and Richard Hakluyt, the last dealing particularly with the commodities to be taken as specimens of English wares, and the points on which information was needed in regard to the countries visited.

[1 A representation of the northern coast of Asia current about this time, as seen in Mercator's map of 1569, was still to a large extent based on the old classical writers. It showed one decided promontory—Cape Tabin—running up into the Arctic Sea, but, beyond this, little further hindrance to a voyage to China in latitudes far lower than the reality. Cape Tabin still appears in the map of Barents's discoveries drawn by Hondius for Pontanus's History of Amsterdam (1611), of which a portion is shown on p. 26.]

Although the amount actually accomplished fell very far short of these expectations, the two captains made a determined fight against heavy odds, and only turned back after trying every means in their power of pushing east across the Kara Sea. The ships separated, after passing the "Wardhouse" (Vardoe), owing to the bad sailing of the William, but a rendezvous was arranged at Vaigatz. The first land sighted by the George seems to have been the south-west coast of Novaya Zemlya, but after vainly searching for a passage Pet went south and explored the mainland coast east of the Pechora, a part of which he took to be the island of Vaigatz. Going north again a meeting was happily effected with the William, and the two ships entered the Kara Sea either through Yugor Shar, the narrow strait between Vaigatz and the mainland, or through the broad opening north of Vaigatz already discovered by Burrough.[1] They were constantly beset by ice and baffled by fog, till at length, after vain endeavours to make headway, the navigators turned their faces homewards, only escaping from the ice with much difficulty. Further dangers were encountered on the shoals of Kolguev Island, and the ships again separated, the George safely reaching Ratcliffe on December 26, 1580, while Jackman, in the William, after wintering on the coast of Norway, set out in the following February towards Iceland in company with a Danish ship, and was never again heard of.

[1 It has been generally held by English writers that the passage was made by Yugor Shar, which has therefore been often known as Pet's Strait, but reasons were put forward by Baron von Nordenskiöld for supposing that the route was to the west and north of Vaigatz.]

Pet and Jackman deserve great credit for the boldness with which they fought their way through the ice-pack of the Kara Sea, as well as for their judgment and resource in availing themselves of any opening which promised to afford a passage. The difficulties of this navigation have baffled many a voyager even in modern times, and it is no matter for surprise that with their small advantages they were unsuccessful in pushing further east. Little serious effort in this direction seems to have been made by the Muscovy Company for some years after this, though a rumour was current about 1584 that an English vessel had previously been lost at the mouth of the Ob, and its crew murdered; while information obtained in that year by Anthony Marsh, one of the Company's factors, points to a knowledge on the part of the Russians at this time of Matyuskin Shar, the strait between the two large islands of Novaya Zemlya.

The search for the north-east passage was now taken up with much zeal by the Dutch, whose heroic attempts to open up the much desired route must now be spoken of, before recurring to the efforts of the Muscovy Company. The first Dutch voyage to the extreme north of Europe seems to have been made in 1565, when a trading post was established at a spot to which the name Kola was given. It is but little after this that we first meet with Olivier (or Oliver) Brunei, a man who took no small part in the further prosecution of Dutch northern enterprise, though himself a native of Brussels. Having undertaken a voyage from Kola to Kolmogro on the White Sea, he was made prisoner by the Russians, apparently at the instigation of the English, and remained so for several years. Being at last liberated through the good offices of the Anikieffs, Russian merchants associated with the Strogonoffs, he made several journeys of exploration on their behalf in the direction of the Ob, visiting Kostin Shar on one occasion. He helped to establish mutual trade relations between Holland and Russia, and eventually secured the support of the famous merchant De Moucheron for a voyage of discovery. Brunei set out in a ship of Enkhuysen in 1584, but met with no success, being baffled in an attempt to pass through Yugor Shar, and losing his ship, with a cargo of furs, etc., in the mouth of the Pechora. He is said to have afterwards entered the service of the King of Denmark, and possibly took part in the voyage of John Knight to Greenland in 1606.

The town of Enkhuysen, which thus had the honour of leading the way in the Dutch voyages of northern discovery, was not long in organising another attempt in the same direction. Among its citizens were several men who had interested themselves in geographical and commercial matters, including the famous Linschoten (whose long residence in the East Indies made him the foremost authority on all matters connected with the eastern trade of the Portuguese) and Cornelis Nai, an experienced seaman. The Middelburg merchant De Moucheron continued to turn his thoughts to the north-eastern route, and the divine and geographer Peter Plancius was a zealous advocate of further enterprise. He did much to improve his countrymen's knowledge of navigation, and among his pupils were Willem Barents and Jacob van Heemskerk, each destined to play an important part in northern discovery. Both were capable seamen, especially Barents, who seems, like John Davis in England, to have been well versed in the science of navigation.[1] In 1594 two vessels were fitted out—the Swan, commanded by Cornelis Nai, and the Mercury, by Brant Tetgales, both natives of Enkhuysen. With Tetgales Linschoten went as commercial agent. At the same time the merchants of Amsterdam decided to take part in the enterprise, and fitted out a third vessel—also named the Mercury—and this was placed under the command of Barents,[2] with whom a small fishing-boat from Terschelling also sailed. The plans laid down by the Amsterdam adventurers differed from those of the men of Enkhuysen, the former considering that a route round the north coast of Novaya Zemlya would offer the greatest prospects of success, while the latter adhered to the idea of entering the Kara Sea through one of the straits separating the several islands. As we have seen, some knowledge of Matyuskin Shar seems to have been gained by the Russians before this date, but the greater part of the coasts of the northern island were certainly unknown, so that the attempt to sail round its northern end betokened great hardihood, though quite justified by the measure of success now and subsequently attained by this route.

[1 Either he, or a contemporary of like name, was author of a sailing directory for the coasts of the Mediterranean.]

[2 The full name of the navigator was Barentszoon, contracted by the Dutch to Barentsz, but the form Barents may conveniently be retained in English. Nai is sometimes spoken of merely as Cornelis Corneliszoon.]

Almost the whole of the voyage was made independently by the two parties, though all the vessels met at a rendezvous at Kildin, in Lapland, towards the end of June. On the 29th, Barents sailed for Novaya Zemlya, which was sighted on July 4 in 73° 25' N., and followed northward to Cape Nassau, which was reached on the loth. Now began a heroic struggle to advance through the ice, which was here encountered in great quantities. It has been calculated that the various courses run by Barents on this coast make up a total of over 1600 nautical miles, the furthest point reached (July 31) being near the Orange Islands. The men now grew discouraged, and seeing but slight probability of accomplishing the object of the voyage, Barents reluctantly agreed to turn back. On August 15 he reached the islands "Matfloe and Dolgoy" (Matthew Island and Long Island) to the S.S.W. of Vaigatz, and fell in with the other captains, who had likewise returned from an ineffectual attempt to push eastward to the Ob. They had sailed through Yugor Shar, to which they gave the name Nassau Strait, being the first navigators, with the doubtful exception of Pet, to pass through this passage into the Kara Sea. They claimed to have sailed eastward as far as the meridian of the mouth of the Ob, but as the distance given is only 50 to 60 Dutch miles (each equal to four geographical miles), this can hardly have been the case. All four vessels now sailed home together, reaching their respective destinations about the end of September.

The report made by Linschoten after the return of the voyagers estimated the chances of future success more favourably than was perhaps justified, and this encouraged the merchants to set on foot a more ambitious undertaking for the following year. Seven vessels took part in it, and this time the Amsterdam merchants were willing to combine with those of the other towns interested, their two ships being placed, like the rest, under the command of Nai, who was appointed admiral of the whole fleet. He sailed in the Griffin of Zeelandt, while Tetgales and Barents commanded, respectively, the Hope of Enkhuysen and the Greyhound of Amsterdam (both new war pinnaces), Barents also undertaking the post of chief pilot of the fleet. The chief commercial agents were Linschoten, who again represented the merchants of Enkhuysen, etc., and François de la Dale, who looked after the Moucheron interests. It was arranged that one of the smaller vessels, a yacht of Rotterdam, should return alone with the news, in case of a successful rounding of Cape Tabin, still supposed to be the crucial point of the whole navigation, the remainder of the passage to China being thought comparatively short and easy. As on the former voyage, a Slav named Spindler went as interpreter, to facilitate the hoped-for intercourse with the peoples of Eastern Asia. The fleet sailed on July 2, 1595, and on the 19th of the same month approached Yugor Shar, having the day before passed Matthew Island ("Matfloe"). The strait was blocked by immense masses of ice, and it soon became evident that its passage would be a matter of unusual difficulty, if not quite impossible. The ships anchored in a bay on the Vaigatz side, behind the point known to the Dutch as Idol Point (not to be confounded with the spot at which Samoyed idols were found by Burrough, which was at the northern end of Vaigatz), and thence an examination of the strait was made both by sea and land, but with little success. Barents appears to have been the most energetic of the captains in his efforts to find a passage, and he repeatedly renewed his attempts when the rest were ready to abandon the task as hopeless. But after immense exertions, which brought the ships only a small part of the way through the strait, the outcome of various councils was that the men of Amsterdam, whose obstinacy seems to have given some offence to their fellow-adventurers, at last agreed to turn back and joined in a protest signed by all the captains and the two commercial agents, declaring that all had done their utmost to fulfil their commission, and that the only course open to them was to sail homewards. Thus ended the voyage on which such great expectations had been built, but which had in reality met with much less success than many of the previous ventures, owing, it is true, to the unusual severity of the season, which had kept the ice in the Yugor Strait packed into a solid mass throughout the summer.

Boats' adventure with a polar bear.

(From De Veer's narrative of Barents's

Voyages.)

In spite of the ill-success of the expedition of 1595, the merchants of Amsterdam, encouraged no doubt by the ardour and sanguine spirit shown by Barents, were ready to make yet another attempt in the following year. It was the belief of Barents, founded on his experiences during the voyage of 1594, that the greatest chance of success lay with the route round the north of Novaya Zemlya, and in this he had the support of the opinion of Plancius. Being now independent of their former associates, the Amsterdam merchants were able to form their plans in accordance with these views. Two ships, the names of which are not recorded, were fitted out, and placed under the command of Jacob van Heemskerk and Jan Corneliszoon Rijp, who had been associated with Linschoten and De la Dale as commercial agents during the second voyage, Heemskerk having Barents with him as pilot and apparently leaving to him a large share in the direction of the voyage. The expedition sailed from Vlieland near Amsterdam on May 18, 1596, and in deference to the opinion of Rijp a course was steered further to the west than on the previous voyages, and this led to the discovery, on June 9, of Bear Island, long called Cherie Island by the English, being so named by Stephen Bennet seven years after its discovery by the Dutch. Here the voyagers landed, and gave the island its name from an encounter they had with a bear. Continuing their voyage towards the north, they reached the ice-pack on June 16, and after tacking to keep clear of it, found the latitude on the 17th to be 80° 10'. On the same day high, snow-covered land was sighted, which was evidently the coast of Spitsbergen, east of Hakluyt Headland (as the extreme N.W. point of the group was afterwards named by Hudson), this island group being thus brought to light for the first time in the history of discovery. Before the end of the month the west coast was explored, southwards, to 76° 50' N., the name still in use for the whole group being applied to the newly discovered land by reason of its sharp summits (though it was taken to be part of Greenland), while that of Vogel Hoek was given to the north point of the Foreland (the long island lying a little off the coast) on account of the multitude of birds there seen. The mouths of Ice Fjord and Bell Sound were also noted. Bear Island was once more reached on July 1, and here the two ships parted company, Rijp returning along the coast of Spitsbergen after a fruitless effort to push north through the sea to the east, while Heemskerk, yielding no doubt to Barents's persuasion, sailed for Novaya Zemlya.[1] The farthest point of the voyage of 1594 was successfully passed, the north-eastern promontory of the group being rounded and a bay reached on the east coast which received the name of Ice Haven. Here the ship was beset, and the navigators were forced to spend the winter in great misery. A house was built of drift-wood, which gave them some shelter from the cold, but scurvy broke out and caused much suffering, Barents himself being one of those most severely attacked. Time wore on, but summer approached without any prospect of the release of the ship. It therefore became necessary to attempt the homeward voyage with no better resource than two open boats, in which, on June 13, they embarked, fifteen in all, Barents and another man being still very ill. On June 20, when with incredible difficulties they were making their way down the west coast of Novaya Zemlya, the indomitable navigator, who had done more than any other to keep alive the hope of effecting the north-east passage, breathed his last, and two others of his comrades soon shared his fate. The survivors at length reached open water, and having obtained some help from two Russian vessels met with on July 28, made their way to Kola, where they found three Dutch ships, one of them commanded by their old comrade Rijp, who took them home to Holland.

[1 See additional note on Rijp at the end of the volume.]

The feat thus accomplished ranks among the hardiest achievements of Polar exploration. For the first time a party of men had wintered far within the Arctic Circle, suffering all the hardships inseparable from such a first experience, without any of the comforts enjoyed by those who have since followed in their footsteps. No other navigator visited their desolate wintering place until nearly three centuries later, when, in 1871, Captain Carlsen landed there and found the hut still standing, and various relics which had been left in it when abandoned by the early explorers. The death of Barents—perhaps the most hardy and capable navigator ever produced by Holland—was a great loss to the cause of Polar discovery, and the small success achieved naturally led to a cessation, for the time being, of the Dutch search for a passage. The next attempt was to be made by the English in the person of Henry Hudson.

Part of Hondius's Map of 1611, showing Barents's

Discoveries.

Click on the map to enlarge it.

Of the early life of this enterprising seaman we know absolutely nothing, and doubts have even been thrown, though with no sufficient reason, on his English nationality. In 1607 we find him in command of one of the Muscovy Company's ships—the Hopewell—which was to renew the search for a northern route to the East, on which so much energy had already been expended by the Company. The idea seems to have been to attempt the passage right across the polar area, according to a suggestion made many years earlier by Robert Thorne. Thus instead of steering for Novaya Zemlya, or even for Spitsbergen, Hudson, who sailed from Gravesend on May 1, directed his course towards the east coast of Greenland, which was sighted on June 13. The southern part of this land had already been touched at more than once during the north-west voyages—which we shall have to consider presently—as well as by Cortereal in the 16th century. But even the point where it was first struck by Hudson was some way to the north, and a still higher latitude was attained during the further voyage; though the observations of the coast, hampered as they were by the ice, did not supply any clear idea of its configuration, the land being still shown in subsequent maps as it had been in that of the Zeni and others of its type. Hudson, however, did a useful piece of work in following the edge of the ice-barrier which extends between Greenland and the neighbourhood of Spitsbergen, and proving that there was little likelihood of a passage being found through it. Spitsbergen seems to have been struck near the Vogel Hoek of Barents, while during subsequent cruises a good part of the west and north-west coasts was examined, and the names Hakluyt's Headland, Collins Cape, and Whales Bay assigned to localities on the west coast.[1] On July 23 an astronomical observation, as recorded in the journal of John Playse (practically the only authority for the voyage), gave the latitude as 80° 23', but the correctness of this is doubtful. In any case enough was done to show that no prospect offered of a passage through the ice-pack, and after sailing to and fro for some time, Hudson was forced to turn homewards, falling in accidentally during the voyage with an island (in Lat. 71°) which must have been that of Jan Mayen, but which was named by him "Hudson's Tutches" (Touches). Tilbury was finally reached on September 15. Besides the negative result as regards the wished-for passage, the voyage was important for the attention called by it to the great number of whales and walrus in the Spitsbergen-Greenland Sea, the capture of which formed the incentive for so many subsequent enterprises.

[1 Whales Bay was the opening in 79° just north of Prince Charles Foreland, Collins Cape being on its northern side.]

The failure of this attempt to pierce the northern ice-barrier did not deter the Company from renewing the search in the following year, when trial was once more made of the old route by Novaya Zemlya, Hudson being again in command, with Robert Juet as mate. Sailing from the Thames on April 22, and passing the North Cape on June 3, he navigated the sea between Spitsbergen and Novaya Zemlya, the first ice being seen on June 9, in 75° 29'. The day before, the change in the colour of the sea to a blue-black had been noted—a change which Hudson had already, in 1607, connected with the neighbourhood of ice, though the coincidence is now said to be purely accidental. For the greater part of this month the voyagers continued to beat about in this sea,[1] constantly hindered by ice from making any advance northwards. As they increased their longitude easterly, they were, in fact, compelled to lose some of their northing, and when Novaya Zemlya was sighted on June 26 near the point called Swarte Klip by the Dutch, they were as low as 72° 25'. Some time was now spent on this coast, landings being effected on several occasions and observations made of the general nature of the country, which they found less inhospitable than previous accounts had led people to suppose. Bird life was plentiful, and many deer, bears, and a fox were seen, the sea also abounding with walrus. Still going southward, they came to Kostin Shar, an inlet with an island dividing it into two branches, which had been reached by Brunei, but placed too far north and corrupted by map-makers into Costing Sarch. Here the powerful set of the current outwards gave Hudson great hopes of finding a passage to the Kara Sea, but an exploration by boat proved them fallacious. Therefore being, as he says, "out of hope to find passage by the north-east," Hudson reluctantly gave up the attempt, being "not fitted to try or prove the passage by Vaigatz," though on the return he hoped to ascertain whether Willoughby's land "were as it is layd in our cards." He also had some idea of making an attempt by the north-west, hoping to be able to run a hundred leagues or so within the sound then known as Lumley's Inlet—which may either have been Hudson Strait itself or a passage further north—and the "furious overfall" which had been seen by Davis (see p. 35). But the time being now far advanced he considered it his duty to the Company not to run unnecessary risks, and returned home, reaching Gravesend on August 26.

[1 An occurrence often referred to in connection with this part of the voyage was the supposed sighting of a mermaid—in reality, no doubt, a seal]

It was not many months before the indefatigable navigator was once more negotiating with a view to a third northern voyage, but not now under the auspices of the English Company, which seems to have lost heart after such repeated failures. The circumstances attending the inception of Hudson's voyage for the Dutch East India Company are not fully known, but the main facts can be pieced together from scattered sources. Either at the end of 1608 or the beginning of 1609 he was invited to Amsterdam to give an account of his northern experiences, and had interviews with Plancius and others; but though the Company thought that a further attempt would be worth making, they came to no immediate arrangement. Meanwhile a scheme, favoured by Isaac Le Maire, had been set on foot for the establishment of a rival company under the patronage of Henry IV of France, and the employment of Hudson on a northern venture. This led the existing company to reconsider their decision, with the result that a ship or ships [1] were equipped at once, and were ready to sail by April 6, 1609. The greater part of the crew were Dutchmen, who seem to have been indisposed to accept Hudson's authority, for after sailing for Novaya Zemlya to make trial, as a last hope, of the passage by Vaigatz, he found disaffection existing, and, the ice giving no greater promise of success than in the previous year, he decided to search for a passage along the American coast, being encouraged to do this by letters and maps sent him from Virginia by Captain Smith.[2] The result was the examination of a stretch of coast extending as far south as 37° 45', and the visiting and naming of the Hudson River. During the return dissension again prevailed, and on reaching Dartmouth on November 7, Hudson and the other Englishmen on board—among whom was Juet, to whom we owe the only detailed narrative of the voyage—were ordered by the English authorities not to leave England, but to remain to serve their own country. It was not long before arrangements were made for an English voyage to the north-west, but before speaking of this we must go back somewhat, and take up the thread of former attempts in this direction.

[1 The greater part of the voyage was made in the Half Moon, but according to statements in the minutes of meetings of the council of the Company, Hudson's ship was the Good Hope, and it has been thought that this may have sailed also, but it seems more probable that a confusion had arisen with the name of the ship in which he made his earlier voyage.]

[2 A renewed Dutch attempt by the north-east route, in 1611-12, is referred to at the end of the volume.]

The voyages of the Cabots, which led the way to the north-eastern coasts of America, were not, as we have seen, followed up for a number of years by any further efforts on the part of the British merchants. The chief credit of re-directing public attention to this route seems to belong to Sir Humphrey Gilbert, though there is little doubt that the idea of renewing the search where it had been broken off by Sebastian Cabot had been working in the minds of others, among them Martin Frobisher, to whom fell the actual task of carrying it out. In 1574 Gilbert wrote a learned discourse to show the probability that an easy route to India would be found by the north-west. While based to a large extent on mistaken premisses, it contained some shrewd ideas, and the argument for a north-west passage based on a study of oceanic circulation had in it something more than mere plausibility. In the then existing state of knowledge it was certainly more justifiable to conclude that an easy passage might be found on this than on the opposite side of the Atlantic; and that the Muscovy Company, which had all Cabot's experience at its disposal, should have so long persisted in its preference for the north-east route would be matter for surprise, were it not for the encouragement offered by the rapid development of trade with northern Russia. Gilbert's treatise was not printed till 1576, by which year Frobisher had already gained so much support, that he was able to sail from Ratcliffe on the Thames on June 7, the expedition consisting of the Gabriel, Frobisher's own ship, the Michael (Captain Matthew Kindersly), and a pinnace. The Queen had taken much interest in the preparations, and among the supporters were Michael Lok, a prominent merchant, Richard Willes,[1] and others. Having reached Foula, the westernmost of the Shetland Islands, Frobisher sailed slightly north of west, and on July 11 sighted land, which was taken to be the Frisland of the Zeno map, the observed latitude of 61° corresponding to that assigned in this to the south end of Frisland. In reality it was the southern point of Greenland, and when this had been passed, a course somewhat north of west brought the ships to a new land, with much ice along its coast. On August 11, in 63° N., Frobisher entered what he took to be the desired strait leading to the Pacific, but which was really the bay, since known by his name, running into the south-eastern extremity of Baffin Land. This was explored during several days, and communication was opened with the Eskimo of that region, who are described as "like to Tartars." But it was found impossible to proceed to the end of the bay, and on the 26th the homeward voyage was begun, Harwich being reached early in October. The new land received, from the Queen herself, the name "Meta Incognita", or the Unknown Bourne.

[1 Willes, like Gilbert, wrote a treatise to prove the probability of a north-west passage, in which he endeavoured to answer the objections of those who took the opposite view. He states these with great clearness, but his own arguments seem hardly calculated to carry conviction.]

Frobisher renewed the search in the two succeeding years (1577 and 1578), in the latter with as many as 13 ships, but without materially adding to his discoveries. His ill-success in the primary object of his voyages made him catch at any chance of deriving a profit from the venture, and he brought home a cargo of a shining mineral which he thought to contain gold, but which proved quite worthless. The promoters naturally lost heart, and Gilbert was soon occupied with the colonising schemes in the more southern parts of North America, in the prosecution of which he lost his life in 1583. But the efforts put forth were not without their ultimate result, for it was not long before others came forward to renew the enterprise, for which the discoveries of Frobisher, scanty though they had been, supplied both incentive and encouragement.

John Davis, the able navigator who was to take up the task where it had been left by Frobisher, was the son of a yeoman landowner at Sandridge in the parish of Stoke Gabriel on the Dart. Here he was a neighbour of the Gilberts, and was likewise brought into the society of their half-brother, Sir Walter Ralegh. Having probably been accustomed to the sea from his early youth, his advice was naturally sought by the promoters of voyages of discovery, among whom Adrian Gilbert, the younger brother of Sir Humphrey, took a prominent place after his brother's death. Another associate was Dr John Dee, the mathematician. In 1585 a new scheme took shape, the necessary funds being provided by various merchants of London and the West Country, principally Mr William Sanderson, a wealthy and influential citizen of London, while the voyage had also the support of Sir F. Walsingham, Secretary to the Privy Council. Davis was placed in command, and sailed from Dartmouth on June 7, with two vessels, the Sunshine of London, a bark of 50 tons, and the Moonshine of Dartmouth, somewhat smaller. On the 28th they left the Scilly Islands—a survey of which was made during an enforced detention—and sailed across the Atlantic without sighting land until, on July 20, the east coast of Greenland was struck, some distance north of Cape Farewell. From its barren and inhospitable nature, the land received the name of Desolation, being considered a new discovery, distinct from the land sighted by Frobisher and by him identified with Frisland. Rounding the southern extremity and resuming his north-west course, Davis again sighted the coast just north of 64°, the extensive opening where Godthaab now is being named Gilbert Sound. Hence he crossed the strait which has since borne his name and examined the opposite coast north of, and within, Cumberland Gulf, which seemed to offer good hopes of a passage westwards. But finding it too late in the season to continue the survey, he decided to return to England and arrived at Dartmouth on September 30.