a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The History of Ballarat, from the First Pastoral Settlement to the Present Time. Author: William Bramwell Withers. * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1304971h.html Language: English Date first posted: August 2013 Date most recently: August 2013 Produced by: Ned Overton. Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Production Notes:

The original map is missing from the scanned document. In its place, a map has been sourced from the State Library of Victoria, compiled by Robert Allan and also published by F.W. Niven. It covers the Ballarat gold mines and shows many of the locations mentioned in Appendix B. Click on this map to enlarge it.

In concordance with the classic, recently released in Project Gutenberg Australia, "The Eureka Stockade" (HTML), translations of all foreign language quotations and passages are here provided as numbered footnotes in an added Glossary. To go to the translation, click on the [red] bracketed number, then click on the [blue] number to return to the text. Withers' book has no footnotes.

Sandhurst is now Bendigo.

THE HISTORY OF BALLARAT.

BY

JOURNALIST.

SECOND

EDITION:

WITH PLANS, ILLUSTRATIONS, AND ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS.

L.N.

TO YOUR MEMORY,

WHOSE

FRAGRANCE

"NO TIME CAN CHANGE,"

I REVERENTLY DEDICATE

THIS RECORD

OF

CHANGE.

{Page vii}

This little History, in eight chapters, only touches a few of the more prominent incidents connected with pastoral settlement and the gold discovery in the Ballarat district. The compiler has seen the growth of the town from a mere collection of canvas tents among the trees and on the grassy slopes and flats of the wild bush to its present condition. Less than 20 years ago there was not a house where now stands this wealthy mine and farm-girdled city, whose population is nearly equal to the united populations of Oxford and Cambridge, and exceeding by several thousands the united populations of the cities of Winchester, Canterbury, Salisbury, and Lichfield at the time of the gold discovery. This is one of the truths which are magnificently stranger than fiction.

Some of the first workers in this mighty creation are still here. Of the pastoral pioneers there are still with us the Messrs. Learmonth, Pettett, Waldie, Winter, Fisken, Coghill, and Bacchus; and the Rev. Thomas Hastie is still living at the Manse at Buninyong.

Down the valley of the Leigh, where the Sebastopol streets and fences run over the eastern escarpment of the table land, may still be seen the sandstone foundations of a station begun by the Messrs. Yuille, whom the coming of the first hosts of gold-hunters scared away from a place no longer fit, in their opinion, for pastoral occupation. Those unfinished walls are in a paddock overlooking a little carse of some four or five acres by the creek side, owned by an Italian farmer, and close to the junction of the Woolshed Creek with the main stream in the valley. On the other side of the larger stream rise basaltic mounds, marked with the pits and banks of the earlier miners. Like the trenches of an old battle-field, these works of the digging armies of the past are now grass-grown and spotted with wild flowers. All around, the open lands of fifteen years ago are turned into streets and fields and gardens. A little way lower down the valley, where the ground has a broad slope up from the left bank of the Leigh to the foot of the ranges, was the Magpie rush of 1855-6. For a mile nearly every inch of frontage was fought for then, and a town of over four thousand inhabitants sprang up. Gold was found plentifully, and warehouse, hotel, and saloon crowded close with dwelling and church along the thoroughfare. A summer flood surprised the dwellers on the lowland and carried off lives as well as property, mingling a tragic sorrow with the losses of the unsuccessful. Time, less sudden than the midsummer freshet, but more sweeping, has cleared the ground of almost every vestige of the busy but fragile life of fifteen years ago. But the eternal sense of the Infinite survives "our little lives" and all their fitful pulsations of varying passion. Yonder, where, by the bush track side, the rounding slope swells upon the south, stands a church, sombre, lonely, and silent as the Roman sentinel at Pompeii when all around him had fled or fallen. This is all, save here and there heaps of broken bottles and sardine tins half hidden by the grass, and a few faint trench and building lines, softened by the rains, and bright at this time with the young verdure of the turning season. The most curious eye could now discover no other traces of the rush if it were not for the broader and deeper marks left where the first miners fought their industrial way, and where, for years, their followers retraced the golden trail. On going up the Yarrowee banks northward a space, as one looks up the valley he sees, beyond the city, the bare top, the white artificial chasms and banks and mounds, where Black Hill raised its dark dense head of forest trees before the digger rent the hill in twain, and half disembowelled the swelling headland.

Besides the pastoral settlers already mentioned, there are yet with us some of the first discoverers. Esmond is still here. Woodward and Turner, of the Golden Point discoverers, are still here in Ballarat, and Merrick and some others of that band remain in the district. Others who followed them within the first week or two are also amongst our busy townsfolk of to-day.

While these remained it was thought desirable to gather some of the honey of fact from fugitive opportunity, that it might be garnered for the historian of the future. Nearly all the persons whose names have been mentioned above have assisted in the preparation of this narrative by furnishing valuable contributions from their own recollections, and the compiler takes this occasion to thank them and others, including legal managers of mines, whose ready courtesy has enabled him to do what he has done to rescue from forgetfulness the brief details here chronicled touching the history of this gold-field. He has borrowed some facts and figures, too, from Mr. Harrie Wood's ably compiled notes, published in Mr. Brough Smyth's "Gold-fields and Mineral Districts of Victoria." To the officers of most of the public institutions referred to he also owes the acknowledgment of much courtesy; and to Mr. Huyghue, a gentleman still holding office in Ballarat, and who was in the public service here at the time of the Eureka Stockade, thanks are due, both by the publisher and compiler, for notes of that period, and for the extremely interesting illustrations of the Stockade, the Camp, and other spots copied from original drawings. The publisher also acknowledges the courtesy of Mr. Ferres, the Government printer, in supplying original documents, and of Mr. Noone in giving valuable assistance in connection with their reproduction by the photo-lithographic process. The contributions of newspaper correspondents during the Eureka Stockade troubles have also assisted the compiler, and notably the letters of the correspondent of the Geelong Advertiser in 1854-5. But to Mr. John Noble Wilson, the commercial manager of the Ballarat Star, is due, on the part of all concerned, the recognition of his suggesting the narrative, of his constant cordial co-operation, and his untiring ingenuity in making suggestions and collecting materials both for the text and the illustrations. The reproduced proclamations by the Government, which the reader will find at intervals, as well as many of the original documents, are the fruit of that gentleman's assiduity in collecting materials of interest and pertinence.

It has been necessary to record the fact that the tragic issue of the license agitation was mainly due to the mistakes of the governing authorities, even as the unrighteous rigors of the digger-hunting processes were made more poignant by the haughty indiscretions and brutal excesses of commissioners and troopers. But it is equally incumbent on the recorder to recognise the more agreeable fact that there were officers in both grades who did their harsh duties differently. Some of these are still in the service, and retain the respect they won in the more troublous times by their judicious and humane administration of an obnoxious law, for the existence of which they were in no way responsible.

In the matter of gold statistics there has been found great difficulty, for the early records were imperfect, and the latter ones are little, if in anywise, superior; while searches for the first newspaper accounts of the gold discovery have shown that, both in Melbourne and Geelong, the public files have been rifled of invaluable portions by the miserable meanness of some unknown thieves.

The future we have not essayed to divine. What the past and the present of our local history may do to enable the reader to speculate upon the future, each one must for himself determine, though the faith of the Ballarat of to-day in the Ballarat of the future may, we think, be more accurately inferred from the stable monuments of civic enterprise, and the many signs of mining, manufacturing, and rural industry around, than from the occasional forebodings of fear in seasons of depression. In less than two decades we have created a large city, built up great fortunes, laid the foundations of many commercial successes, and sown the seeds of yet undeveloped industries; and those who have seen so much should not readily think that we are near the exhaustion of our resources, either in the precious minerals, or the still more precious spirit of enterprise and industry necessary for the development of the wealth of nature around us. For the good done, and for the doers of the good, we may all be thankful, if not proud; and, in proportion as we are thus moved, we may look with confident hope towards the future, whose uncertain years are lit up with the radiance of the past, and shaped to our vision by the promise of the present.

Among modest writers it is the fashion not only to write prefaces, but to excite attention to wonderful merit by apologies for defects. The present writer burns to be in the fashion. He craves the indulgence of the reader in informing that important personage that the ordinary duties of a reporter on a daily morning paper are not luxuriously light, and that the compilation of the following narrative has been a refreshing appendage to the daily discharge of such ordinary duties, plus a bracing exercise of sub-editorial function. He has, no doubt, amply vindicated Bolingbroke's accurate apothegm, and especially in this preface. Both preface and narrative may be regarded as a verbose exaggeration of the importance of the subject. The answer to that is, that the writer has written mainly for those who know the place, and, knowing it, are proud of it; for those who believe in the future in reserve for it, for the colony to which it belongs to-day, and for the empire of which it some day may be a not altogether unimportant portion.

In the City of York, where memory and fancy, busy with the records and the remains of the past, make of the softened lights and shadows and many-colored figures of mediaeval English history an inexpressible charm, the glorious Minster rises over all supreme in its solemn and saintly beauty. Whatever pilgrim there has studiously perused that marvellous "poem in stone" may have seen over one of the doorways the work of some loving and pious egotist in the following inscription:—"Ut rosa flos florum, sic tu es domus domorum." [1] Let us be permitted, with similar egotism, if not with equal piety, to inscribe here, as over one of the portals of approach to one of the golden fields and cities of Victoria:—Ut aurum metallorum pretiosissimum, sic tu es camporum aureorum princeps, urbiumque opulentissima. [2]

W.B.W.

Ballarat, 22nd June, 1870.

{Page xii}

This second edition was called for as the first was out of print, and this new issue and all the author's interest in the History are the sole property of the publishers. In transferring my rights to the publishers, I undertook to write what was deemed necessary to bring the narrative "up to date". To do this and supply some omissions from the first edition were, both, desirable, and the attempt has been carried out as far as the publishers' views as to space have permitted. How inadequate the realisation is, my repeated wails in the text admit as frankly as possible. Independently of the omissions from the first edition, the developments of the city and suburbs during the 17 years since 1870 involved so much matter that it was found impossible to deal with it all in a satisfactory manner within the space available; but it is hoped that the leading events of the period have, at least, been in some way recognised. And even that could not have been done had it not been that the author, with some few exceptions, met everywhere the readiest will to assist him by supplying the official information required. In the body of the work these courtesies have been generally acknowledged, and I desire to repeat here my sense of indebtedness in that respect to very many citizens. It is not for me to judge how ill or well my part of the work has been done, but it may be permitted to me to say that the publishers and printers have finished their work in a manner that does credit to them and to the arts they represent. Mr. Niven has enriched the edition with many illustrations from his own pencil, and the photo-lithographs of official and other documents which give fac similes of those papers, bespeak the resources of the publishers' establishment. The apposite; designs on the cover, and their engraving and printing, are all the product of the publishers' own office, and compare creditably with the work of old-world firms. The map of the mines, at page 232,* has been prepared from surveys specially made by Mr. Robert Allan, mining surveyor, and is a document of interest and value. To Mr. Anderson, the head printer, I owe my thanks for many intelligent suggestions in the course of the revisal of proofs, and his vigilant eye detected some errors in Appendix A which had lain unnoticed ever since the issue of the edition of 1870. It is hoped that the present edition is nearly free from literal errors, but two or three have been noticed since the matter passed through the press. In the bottom line, page 61, the date 1855 should be 1854; in the heading to Chapter VI. "representative charges" should be "representative changes;" and in the bottom line, page 285, the date 1857 should be 1856.**

[* The original map was not available; another, also produced by Niven, has been substituted here—N.O.]

[** All these corrections have been made—N.O.]

A word to scholars, that they may not believe a lie. I am no Latinist. As a poor pavior on the high road of letters, I picked up some Roman tesseræ [3] by the way side, and, to please my fancy and give bits of color and tone of reminiscence and meaning not else handy, inserted them here and there in the ruder work. Only that, my learned brothers of the great republic.

The writer of even so small a history as this, is but as the voice of one crying in a wilderness of facts and dates, in hope of reducing them in some sort to cosmic order. Like the life it essays to depict, history is only a drama, and the historian merely sets the scenes, and lifts the curtain, where else had been uncertainty or oblivion.

Our revels now are ended. The actors here, too, were all spirits. Many, as squatters Pettett, Waldie, Winter Bacchus, one of the Learmonth's, besides a host of mining and civic pioneers, have melted into air since the first edition was issued. The veteran Thomas Hastie still lives at the Buninyong manse, and others still grace, or disgrace, with their corporal presence, the scenes of their exploits. There remain Humffray and Lalor, and, with other of Lalor's Stockade subalterns, the gold-finder Esmond. Humffray and Esmond are in the shallows, but Lalor, on whose "rebel" head a price was once set, floats proudly as the able and well-salaried Speaker of the Legislative Assembly. His political friends are not ashamed to plead for a retiring pension for him, after he has, for many years, been liberally paid for his services in a nominally pension-hating democracy; whilst Esmond, but for whose discovery Lalor might never have been here, has failed to get leave to earn State wages enough to keep the wolf from the door.

The fingers of change move swiftly. Whilst facts and figures have been shaping for the printers of this edition, the funerals of some of those who furnished the matter have passed by. Since the last chapter has been in type, the old mess-room of the civil and military officers of the Camp has been sold, and its materials have been removed piece-meal. Thirty years ago, the present Premier of Victoria stood in his blue serge shirt on the verandah of the house, and unsuccessfully tried to persuade his brother blue-shirts to return him, at that time, to the court then sitting there. "Rebel" bullets fell about the house during the ante-Stockade trouble, and then the vanquished victors of the Stockade sent representatives to sit in the mess-room as a Local Court, with Warden Sherard as first chairman, and thereafter, as long as the court lived, with the merry, brown-eyed Daly, and with the merrier and caustic Miskelly as the clerk for awhile. Ex-Chairman Sherard is still here, as Savings Bank actuary, but Daly and many others, who sat there a generation agone, are dead. The old historic house itself is now gone, too, and a free public library is to be built upon the site.

For myself, I now vanish for ever from this stage, to write editions of this History no more—if this be history. But though I now retire behind the scenes, so far as this work is concerned, I shall not forget the play nor the leading players. The largest portion of my life has been spent here, and if there be any possibility of the realisation of such a sad conceit as that of the Tudor Mary, who said Calais would be found written upon her heart, the name of this beautiful city of Ballarat may be found written upon mine.

W.B.W.

Ballarat, 3rd August, 1887.

General View of Ballarat,

1887

(Frontispiece).

"King Billy" and Ballarat Tribe, 1850

Ballarat in 1852 from Mount Buninyong

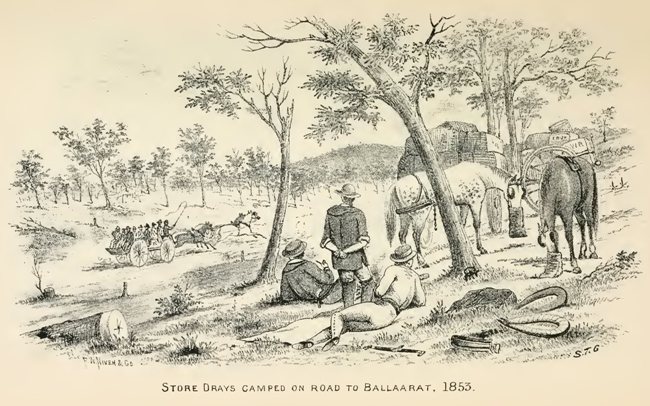

Store Drays on the Road to the

Diggings

Creswick Creek from Spring Hill, 1855

Ballarat Flat, 1855, from Black Hill

The "Township" from Bath's hotel, 1855

John Alloo's Restaurant, Main road,

1853

Deep Sinking, Bakery Hill, 1855

First Quartz Mill, Black Hill

Arrival of the Geelong Mail Coach

Gold-digging License

Business License

Arrival of Troops

Site of the Eureka Stockade

Government Notices:

[Notice on Social Order]

[Notice by the Resident Commissioner]

[Notice to Special Constables]

Proclamations:

[Two Proclamations]

[Reward for Lawlor and Black]

[Reward for Vern]

[Notice by the Lieutenant-Governor]

[Notice by France's Consul]

Soldiers' and Diggers' Graves

The Stockade Memorial

Golden Point and Yarrowee Creek

First Horse Puddler

Band and Albion Consols Mine, 1887

Madame Berry Mine, 1887

Mining Plan of Ballarat [substitute]

Mining Registrar's Old Office

View of Sturt street

Lake Wendouree

| [Preface to the First Edition] [Preface to the Second Edition] CHAPTER I. First Exploring Parties.—Mount Buninyong.—Mount Aitkin.—Ercildoun.—Ballarat.—Lake Burrumbeet Dry.—Settling Throughout the District.—First Wheat Grown.—First Flour Mill.—Founding of Buninyong.—A Wide Diocese.—Appearance of Ballarat.—The Natives.—Aboriginal Names.—The Squatters.—Premonitions of the Gold Discovery. CHAPTER II. California and the Ural.—Predictions of Australian Gold.—Discoveries of Old Bushmen.—Hargreaves and others in New South Wales.—Effects of Discovery at Bathurst.—Sir C.A. Fitz Roy's Despatches.—First Assay.—Esmond and Hargreaves.—Esmond's Discovery at Clunes.—Previous Victorian Discoveries.—Esmond's the First Made Effectively Public.—Hiscock.—Golden Point, Ballarat.—Claims of Discoverers as to Priority.—Effects of the Discovery.—Mr. Latrobe's Despatches.—His Visit to Ballarat.—The Licenses.—Change of Scene at Ballarat.—Mount Alexander Rush.—Fresh Excitements.—Rise in Prices. CHAPTER

III. Great Aggregations of Population.—Opening up of Golden Grounds.—A Digger's Adventures.—Character of the Population.—Dates of Local Discoveries.—Ballarat Township Proclaimed.—First Sales of Land.—Bath's Hotel.—First Public Clock.—Tatham's and Brooksbank's Recollections.—Primitive Stores, Offices, and Conveyances.—Woman a Phenomenon.—First Women at Ballarat.—Curious Monetary Devices.—First Religious Services.—Churches.—Newspapers.—Theatres.—Lawyers.—First Courts.—Capture of Roberts, the Nelson Robber.—Nuggets.—Golden Gutters.—Thirty or Forty Thousand Persons Located. CHAPTER IV. The Gold License.—Taxation Without Representation.—Unequal Incidence of the Tax.—Episodes of Digger Hunting.—Irritating Method of Enforcing the Tax.—Suspicions of Corruption among the Magistrates and Police.—Visit of Sir Charles and Lady Hotham.—Big Larry.—Roff's Recollections.—Reform League.—Murder of Scobie.—Acquittal of Bentley.—Dewes Suspected.—Mass Meetings.—Burning of Bentley's Hotel.—Irwin's Narrative.—Arrest of Fletcher, M'Intyre, and Westerby.—Re-arrest of Bentley.—Conviction of Bentley.—Rich's Experiences.—Conviction of Fletcher, M'Intyre, and Westerby.—Demand for their Liberation.—Increased Excitement.—Fête to the American Consul.—Foster.—Sir Charles Hotham.—Arrival of Troops.—Troops Assaulted.—Bakery Hill Meeting.—Southern Cross Flag.—Burning the Licenses. CHAPTER V. The Last Digger Hunt.—Collision between the Diggers and Military and Police.—Southern Cross Flag again.-—Lalor and his Companions Armed, kneel, and swear Mutual Defence.—Irwin's Account.—Carboni Raffaello.—His Pictures of the Times and the Men.—More Troops Arrive.—The Diggers Extend their Organisation Under Arms.—Lalor "Commander-in-Chief".—Forage and Impressment Parties.—Original Documents.—Shots Fired from the Camp.—The Stockade Formed.—Narrative of a Government Officer in the Camp.—Attack by the Military and Taking of the Stockade.—Various Accounts of the Time.—Raffaello's Description.—Other Tragic Pictures.—First Stone House.—Bank of Victoria Fortified.—A Soldier's Story.—List of the Killed.—Burials.—Rewards Offered for the Insurgent Leaders.—Their Hiding and Escape.—Charge Against A.P. Akehurst.—Proclamation of Martial Law.—Feeling in Melbourne.—Foster's Resignation.—Deputation of Diggers.—Humffray Arrested.—Vote of Thanks to the Troops.—Legislative Council's Address to the Governor.—His Reply.—Prisoners at the Ballarat Police Court.—Royal Commission of Enquiry.—Trial and Acquittal of the State Prisoners.—Humffray.—Lalor's and his Captain's Hiding Place and Peculiarities.—Cost of the Struggle.—Compensation Meeting at the Stockade.—Raffaello there Selling his Book.—Subsequent Celebrations.—Soldiers' and Diggers' Monuments.—The Burial Places.—The Insurgent Flag.—Death of Sir Charles Hotham.—Hotham and Foster Vindicated. CHAPTER VI. Ballarat Politically Active and Influential.—New Constitution.—Humffray and Lalor Elected.—Their Addresses.—Humffray in Trouble.—Lalor on Democracy.—Lalor on the Star.-—The Grand Trunk Affair.—Petition for a Private Property Mining Law.—Neglect by the Parliaments of Mining Interests.—Probable Causes.—New Political Demands.—Votes of Lalor and Humffray.—Burial Expenses of Governor Hotham.—O'Shanassy Chief Secretary.—Haines Succeeds, with M'Culloch as Commissioner of Customs.—O'Shanassy in Power Again.—Nicholson Cabinet.—Succeeded by Heales, with Humffray as First Minister of Mines.—O'Shanassy in Power Again.—Succeeded by M'Culloch.—The Tariff.—Re-call of Governor Darling.—Darling Grant Crisis.—Death of Governor Darling.—Grant to his Widow and Family.—Sladen Ministry.—M'Culloch in Power Again.—Representative Changes.—Jones Declared Corrupt.—Defeats Vale.—The Macpherson Ministry.—Its Resignation.—Macgregor's Failure.—M'Culloch and Macpherson in Office Together.—Michie Elected for Ballarat West.—First Berry Government.—M'Culloch in Power Again.—Joseph Jones, Minister of Railways.—Major Smith in the Second and Third Berry Governments.—His "Merry Millions".—His Breach with Berry.—Ballarat Sticks to him.—C.E. Jones Returned Again.—He and his Tribune.—R.T. Vale and Jones beat Bell and Fincham.—Ballarat East Candidates: their Ups and Downs.—James, Minister of Mines, Loses his Seat, and Leaves Political Life.—Council Elections.—Wanliss Petitions Against Gore's Return.—A Local Self-Government Paroxysm.—Local Court.—Mining Board.—Court of Mines.—Local Courts Wrongly Constituted.—Mining Boards.—Judge Rogers and Black Wednesday.—One Code of Mining Law Required.—Valuable Services of the Earlier Courts and Boards. CHAPTER

VII. Block and Frontage Claims.—Some Early Diggers.—Election Excitements.—Opposition to Extended Areas.—Such Opposition a Mistake.—Present Areas.—Progress of Mining Discoveries.—Increased Operative Difficulties.—Introduction of Machinery.—Luck in Digging.—Mining Agreements and Litigation.—The Egerton Case.—The Clunes Riot.—The Browns Leases.—Pleasant Creek Jumps.—Stink Pots.—Private Property Leases and Law.—Foreign Capital.—Sebastopol Drainage.—Prospecting Board.—Koh-i-Noor, Band and Albion Consols, Llanberris, and Black Hill Quartz Companies.—The Kingston Alluvial Field.—Gold Returns and Mining Statistics.—Pre-eminence of the Ballarat District.—Westgarth on the Purity of Ballarat Gold.—Assays of Ballarat Nuggets.—Table of Nugget Dates, Weights, and Localities.—Sebastopol Plateau Revival.—Increasing Proportion of Quartz Gold.—The Future to be Chiefly Quartz Mining.—The Corner.—A Great Transition. CHAPTER

VIII. Area and Population of Ballarat.—Great Mining Collapse.—Municipal Statistics of Ballarat West, Ballarat East, and Sebastopol.—Water Supply.—Lake Wendouree.—Yacht and Rowing Clubs.—Hospital.—Benevolent Asylum.—Orphan Asylum.—Female Refuge.—Ladies' Benevolent Society.—Roman Catholic and Anglican Dioceses.—Churches.—State and Church Schools—School of Mines.—Museum—Observatory.—Public Art Gallery.—The Stoddart Gift.—The Russell Thompson Bequest.—The Burns Statue.—Other Statues Projected.—Typography.—Photography.—Lithography.—Public Libraries.—Mechanics' Institute.—Academy of Music.—Eisteddfod.—Cambrian Society.—Musical Societies.—Agricultural and Horticultural Societies.—Iron Foundries.—Implement Factories.—Woollen Mills.—Coachbuilding.—Flour Mills.—Bone Mills.—Breweries.—Distilleries.—Cordial Factories.—Bacon Factories.—Tanneries.—Boot Factories.—Juvenile Industrial Exhibition.—Fire Brigades.—Volunteers and Militia.—Gas Company.—Banks.—Recreation Reserves.—Cricket and Football Clubs.—Hunt, Race, Coursing, and Gun Clubs.—Roller Skating Rinks.—Acclimatisation, Caledonian, and Hibernian Societies.—Reformatory.—Hope Lodge.—Railways.—Tramways.—Public Offices.—Public Halls.—Gaol and Court House.—Camp.—Last of the Military.—Explorers' Monument.—Queen's Jubilee and Old Pioneers.—Electric Telegraph and Telephone.—Rainfall and Temperature.—Henry Sutton.—Local Journalism.—Royal and Other Visitors.—Reminiscences.—Past and Present Contrasts. Appendix A: [Representatives in Parliament for Ballarat from the First Election in 1855 to the Year 1886.] Appendix B [Glossary: Translations of Foreign Language Quotations and Phrases.] |

HISTORY OF BALLARAT.

{Page 1}

BALLARAT BEFORE THE GOLD DISCOVERY.

First Exploring Parties.—Mount Buninyong.—Mount Aitkin.—Ercildoun.—Ballarat.—Lake Burrumbeet Dry.—Settling Throughout the District.—First Wheat Grown.—First Flour Mill.—Founding of Buninyong.—A Wide Diocese.—Appearance of Ballarat.—The Natives.—Aboriginal Names.—The Squatters.—Premonitions of the Gold Discovery.

In January of the next year explorers set out again. The party this time consisted of Messrs. J. Aitken, Henry Anderson, Thomas L. Learmonth, Somerville L. Learmonth, and William Yuille. The starting point was Mr. Aitken's house, at Mount Aitken, and thence the explorers went towards Mount Alexander, which at that time had just been occupied by a party of overlanders from Sydney, consisting of Messrs. C.H. Ebden, Yaldwin, and Mollison. From Mount Alexander they followed the course of the Loddon, passed over what has since been proved to be a rich auriferous country, and bore down on a prominent peak, which the explorers subsequently called Ercildoun, from the old keep on the Scottish border, with which the name of the Learmonth's ancestor, Thomas the Rhymer, was associated. Their course brought them to the lake district of Burrumbeet and its rich natural pastures. The days were hot but the nights cold, and the party, camping at night on an eminence near Ercildoun, suffered so much from cold that they gave the camping place the name Mount Misery. There was water then in Burrumbeet, but it was intensely salt and very shallow. Next year, 1839, Lake Burrumbeet was quite dry, and it remained dry for several succeeding summers. It was covered with rank vegetation, and the ground afforded excellent pasture after the ranker growth had been burnt off. The country thus discovered was occupied during the year 1838, and other settlers, pushing on in the same direction, in a couple of years completed the occupation of all the fine pastoral country as far westward as the Hopkins River. The brothers Learmonth, Mr. Henry Anderson, Messrs. Archibald and W.C. Yuille, and Mr. Waldie settled on the subsequently revealed gold-fields of Ballarat, Buninyong, Sebastopol, and their immediate vicinities. Some members of the Clyde Company, of Tasmania, visited the Western district in 1838, that company giving the name to the Clyde Inn, of the old Geelong coach road. They settled upon the Moorabool and the Leigh, Mr. George Russell being the manager. Major Mercer, who gave the name to Mount Mercer, and Mr. D. Fisher, were of that company. The Narmbool run, near Meredith, was taken by Mr. Neville in 1839. Ross' Creek was named from Capt. Ross, who in those early days used to perform the feat of walking in Highland costume all the way to Melbourne. But in those times travelling was a more serious matter than in these days of railroads, coaches, cabs, and other vehicles, with good roads and a generally settled country. Then there were no roads, few people, and a thick forest, encumbered about Ballarat, too, with the native hop. Mr. Archibald Fisken, of Lal Lal, was the first person to drive a vehicle through the then roadless forest of Warrenheip and Bullarook. In 1846 he drove a dog-cart tandem with Mr. W. Taylor through the bush to Longerenong, on the Wimmera.

Messrs. T.L. and S.L. Learmonth, whose father was then in Hobarton, settled their homestead on what became known as the Buninyong Gold Mining Company's ground at Buninyong. Mr. Henry Anderson, who was the earliest pioneer in what is now known as Winter's Flat, planted his homestead near the delta formed by the confluence of the Woolshed Creek and the Yarrowee, Messrs. Yuille subsequently taking that homestead and all the country now known as Ballarat West and East and Sebastopol. These settlers gave the name to Yuille's Swamp, more recently called Lake Wendouree. The Bonshaw run was taken up by Mr. Anderson, 'who named it Waverley Park, and Mr. John Winter coming into possession shortly afterwards gave to it the present name, after his wife's home in Scotland. Messrs. Pettett and Francis, in 1838 (as managers for Mr. W.H.T. Clarke), took up the country at Dowling Forest, so called after Mrs. Clarke's maiden name. Shortly after they had settled there Mr. Francis was killed by one of his own men with a shear-blade, at one of the stations on the run. Before Mr. Pettett took up the Dowling Forest run he was living at the Little River, and a native chief named Balliang offered to show him the country about Lal Lal. The chief in speaking of it distinguished between it and the Little River by describing the water as La-al La-al—the a long—and by gesture indicating the water-fall now so well known, the name signifying falling water. Mr. Waldie subsequently took up country north-west of Ballarat, and called his place Wyndholm, where he resided till his decease. Messrs. Yuille had settled originally on the Barwon, near Inverleigh, but finding the natives troublesome they retired to Ballarat. Mr. Smythe, who with Mr. Prentice held the run, gave the name to Smythe's Creek, as Messrs. Baillie had to the creek at Carngham their run there being afterwards transferred to Messrs. Russell and Simson. Mr. Darlot also occupied a run there. Creswick Creek has its name from Henry Creswick, who settled upon a small run there. Two brothers Creswick had previously held country close to Warrenheip. The Messrs. Baillie were sons of Sir William Baillie, Bart., of Polkemmet, Scotland. Mr. Andrew Scott settled with his family at the foot of Mount Buninyong, where he had a snug run in which the mount and its rich surrounding soil were included. Mrs. Andrew Scott was the first lady who travelled through this district. She drove across the dry bed of Lake Burrumbeet in the year 1840. The country about Smeaton and Coghill's Creek was taken up in the year 1838 by Captain Hepburn and Mr. David Coghill who came overland from New South Wales with sheep and cattle, following the route of Sir Thomas Mitchell in his expedition of exploration in Port Phillip in 1836. With them came Mr. Bowman, who also brought stock. He took up a run on the Campaspe, while his companions came on further south. The Murray was very low when they crossed, and the stock was easily passed over. At the Ovens they found a dry river-bed; Lake Burrumbeet was also dry that year. When Messrs. Hepburn and Coghill had left sheep at the Campaspe and Brown's Creek on their way, they pushed on, and from Mount Alexander they descried the Smeaton Hills, and, continuing their journey, found and took up the unoccupied country there. Smeaton Hill was called Quaratwong by the natives, and the hill between the Glenlyon road and Smeaton Hill was called Moorabool. Captain Hepburn, a seafaring man originally, was one of the Hepburns of East Lothian, Scotland, and Smeaton was named by him after the East Lothian estate held by his relative, Sir Thomas Hepburn. Mr. Coghill was the first to plough land at the creek which bears his name, and in which locality there now is found one of the broadest and richest tracts of farming land in Victoria. He brought with him overland a plough, a harrow, and the parts of a hand steel flour-mill. In 1839 he ploughed and sowed wheat, and thus grew and ground the first corn grown there. In 1841 Captain Hepburn erected a water-mill for corn on Birch's Creek; that was the first mill of that kind. Birch's Creek was named after the brothers Arthur and Cecil Birch, who, with the Rev. Mr. Irvine, came overland soon after Messrs. Hepburn and Coghill, and settled at the Seven Hills. Besides the run at Coghill's Creek, taken up by Mr. Coghill for some others of his family. Cattle Station Hill was also taken by him. This run lay between Glendaruel and the Seven Hills, and was part of the purchased estate belonging to the Hepburns. The late Captain Hepburn long acted as a justice of the peace, and he was one of the squatters whom M'Combie mentions as having taken part in a meeting held on the 4th of June, 1844, in front of the Mechanics' Institute, Melbourne, to protest against Sir G. Gipps' squatting policy, and to urge forward the movement for the separation of Port Phillip from New South Wales. The squatters mustered on horseback that day on Batman's Hill, and thence rode to the meeting in Collins street, the "equestrian order" thus giving an early example of the right freemen have, even in a Crown colony, to air public grievances publicly and fearlessly.

Lal Lal was taken up in the year 1840 by Messrs. Blakeney and George Airey, the latter a brother of the Crimean officer so often and so flatteringly mentioned in Kinglake's "History of the Crimean War". In the same year, Messrs. Le Vet (or Levitt) and another took up Warrenheip as a pig-growing station, but the venture failed, and some of the pigs ran wild in the forest there for years, and preyed on each other. After Messrs. Le Vet and Co. had been there awhile, the run was taken up on behalf of Messrs. Verner, Welsh, and Holloway, of the Gingellac run, on the Hume, by Mr. Haverfield (at present the editor of the Bendigo Advertiser), Le Vet and partner selling their improvements for about £30. Shortly after Mr. Haverfield came to Warrenheip, Bullarook Forest was occupied by Mr. John Peerman, for Mr. Lyon Campbell. The Mr. Verner mentioned above was the first Commissioner of the Melbourne Insolvency Court. He was related to Sir William Verner, a member in the House of Commons for Armagh. Mr. Verner took part, as chairman, at a Separation meeting held in Melbourne on the 30th December, 1840, and soon after that he left the colony. Mr. Welsh was the late Mr. Patricius Welsh, of Ballarat; and Mr. Holloway became a gold-broker, and died at the Camp at Bendigo. In the year 1843, Mr. Peter Inglis, who had a station at Ballan, took up the Warrenheip run, and shortly after that purchased the Lal Lal station, and throwing them both together, grazed on the united runs one of the largest herds in the colony. The western boundary of Mr. Inglis' Warrenheip run marched with the eastern boundary of Mr. Yuille's run, the line being struck by marked trees running from Mount Buninyong across Brown Hill to Slaty Creek. Mr. Donald Stewart, now of Buninyong, was stock-rider for Mr. Inglis, on the Warrenheip and Lal Lal stations, and superintendent during the minority of the present owner of Lal Lal. In 1839 Mr. W.H. Bacchus brought cattle from Melbourne and grazed them on his run of Burrumbeetup, the centre of which run is now occupied by the Ballan pound. There is a waterfall on the Moorabool there, which, for its picturesque beauty, is well worth visiting. The run extended on the Ballarat side of the Moorabool to about midway to the Lal Lal Creek. Mr. Bacchus still resides in the same locality, his present station being known as Perewur, or Peerewurr, a native name, meaning waterfall and opossums. It was originally held by Messrs. Fairbairn and Gardner. Buninyong was a village, or township, long before Ballarat had any existence as a settlement. The first huts were built at Buninyong in the year 1841, by sawyers, splitters, and others, Mr. George Innes being then called the "King of the Splitters". George Gab, George Coleman, and others, were the pioneers in the Buninyong settlement. Gab had a wife who used to ride Amazonian fashion on a fine horse called Petrel, and both husband and wife were energetic people. Gab opened a house of accommodation for travellers on the spot where Jamison's hotel was afterwards built. The first store in the neighborhood was opened at the Round Water Holes, near Bonshaw, by Messrs. D.S. Campbell and Woolley, of Melbourne, who almost immediately afterwards removed to a site next Gab's, at Buninyong, whose place they took for a kitchen. Gab then removed and built another hut opposite to the present police-court, and he opened his new hut also as a hotel. A blacksmith named M'Lachlan, with a partner, opened a smithy opposite to Campbell and Wooley's store. This was the nucleus of the principal inland town then in the colony. In the year 1844 Dr. Power settled there, and built a hut behind what was afterwards the Buninyong hotel. He was the first medical man in the locality, and for years the settlers had no other doctor nearer than Geelong. The young township became a favorite place with bullock teamsters, who were glad to build huts there where they could leave their wives and children in some degree safe from aboriginal or other marauders. In the year 1847, the Rev. Thomas Hastie, the first clergyman in the district, came to Buninyong. His house, and the church in which he performed service, were built entirely by the residents in Buninyong, both pecuniary gifts and manual labor being contributed. Then, as afterwards, the Messrs. Learmonth were among the foremost movers in the promotion of the mental and moral, as well as material welfare of the people about them. Mr. Hastie, in a letter to us, says:—

Before I came in 1847, the Messrs. Learmonth had made several efforts to procure the settlement of a clergyman at Buninyong, but had failed, partly from want of support, but chiefly from their inability to procure one likely to be suitable. Overtures had been made to Mr. Beazely, a Congregational minister then in Tasmania, and afterwards in New South Wales, but he declined them. The Messrs. Learmonth were willing to take a minister from any denomination, and the circumstance that a Presbyterian clergyman was settled here arose from the fact that no other was available. Until after the gold discovery there was no minister in the interior, that is out of Melbourne, Geelong, Belfast, and Portland, but Mr. Hamilton of Mortlake, Mr. Gow of Campbellfield, and myself. For many years my diocese, as it may be called, extended from Batesford, on the Barwon, to Glenlogie, in the Pyrenees, and included all the country for miles on either side, my duties taking me from home more than half my time. Before I came the Messrs. Learmonth had contemplated the establishment of a cheap boarding-school for the children of shepherds and others in the bush, but for prudential reasons they deferred the matter till the settlement of a minister offered the means of supervision. Immediately after I came the project was carried out, and subscriptions were received from most of the settlers in the Western district. The school was opened in 1848 by Mr. Bedwell, £10 a year being charged for board and education.

The gold discovery carried away the teachers, raised the prices of everything, and Mr. Hastie had to see to the school and its GO boarders himself; but through all the difficulties the school was maintained with varying fortunes, until at length it became the Common-school near the Presbyterian Manse, with an average attendance of some 180 children.

What is now the boroughs of Ballarat, Ballarat East, and Sebastopol, was then a pleasantly picturesque pastoral country. Mount and range, and table land, gullies and creeks and grassy slopes, here black and dense forest, there only sprinkled with trees, and yonder showing clear reaches of grass, made up the general landscape. A pastoral quiet reigned everywhere. Over the whole expanse there was nothing of civilisation but a few pastoral settlers and their retinue—the occasional flock of nibbling sheep, or groups of cattle browsing in the broad herbage. There were three permanent waterholes in those days where the squatters used to find water for their flocks in the driest times of summer. One was at the junction of the Gong Gong and the Yarrowee, or Blakeney's Creek, as it was then called, after the settler of that name there. Another was where the Yarrowee bends under the ranges by the Brown Hill hotel, and the other was near Golden Point. Aborigines built their mia-mias about Wendouree, the kangaroo leaped unharmed down the ranges, and fed upon the green slopes and flats where the Yarrowee rolled its clear water along its winding course down the valley. Bullock teams now and then plodded their dull, slow way across flat and range, and made unwittingly the sites and curves of future streets. Settlers would lighten their quasi[new?] solitude with occasional chases of the kangaroo, where now the homes of a busy population have made a city; it was a favorite resort of the kangaroo, and Mr. A. Fisken, of Lal Lal, and other settlers often hunted kangaroo where Main, Bridge, and other streets are now. The emu, the wombat, the dingo, were also plentiful. The edge of the eastern escarpment of the plateau where Ballarat West now is, was then green and golden in the spring time with the indigenous grass and trees. Where Sturt street descends to the flat was a little gully, and its upper edges, where are now the London Chartered Bank, the Post-office, and generally the eastern side of Lydiard street, from Sturt street to the gaol site, were prettily ornamented with wattles.

"King Billy" And The Ballarat Tribe,

1851.

I often passed (says Mr. Hastie) the spot on which Ballarat is built, when visiting Mr. Waldie, and there could not be a prettier spot imagined. It was the very picture of repose. There was, in general, plenty of grass and water, and often I have seen the cattle in considerable numbers lying in quiet enjoyment after being satisfied with the pasture. There was a beautiful clump of wattles where Lydiard street now stands, and on one occasion, when Mrs. Hastie was with me, she remarked, "What a nice place for a house, with the flat in front and the wattles behind!" Mr. Waldie had at that time a shepherd's hut about where the Dead Horse Gully is on the Creswick Road, and one day when I was calling on the hut-keeper, he said the solitude was so painful that he could not endure it, for he saw no one from the time the shepherds went out in the morning till they returned at night. I was the only person he had ever seen there who was not connected with the station.

The ground now occupied by Craig's hotel on one side of the gully that ran down by the "Corner", and by the Camp buildings on the other side, were favorite camping places in the pastoral days. Safe from floods, and near to water and grass, the spot invited herdsman and shepherd, bullock-driver and traveller, to halt and repose.

The aborigines were nut numerous about Ballarat even in those early days; a little earlier, however, as when Dowling Forest was taken up, they were more numerous and were often troublesome, being great thieves. Several of the adults were strongly marked with small-pox at the time the locality was taken up for pastoral occupation. The natives, were considered inferior to the Murray tribes, and were generally indolent and often treacherous. From time to time they were troublesome to the settlers—as well to the good as to the bad. King Billy was the name given to the chief of the tribes about here, and that regal personage for many years wore a big brass plate bearing his title. He was chief of the tribes about Mounts Buninyong and Emu, and King Jonathan, of a Borhoneyghurk tribe, was his subordinate.

My brother and I (says Mr. Somerville L. Learmonth) began by feeding and being kind to the natives, but not long after the establishment of our first out-station, on the way to Smythesdale, we were aroused in the dead of night by the intelligence that Teddy, the hut-keeper, had been murdered. Some of the natives had seen the ration-cart on the previous day; they watched until the hut-keeper went unarmed to the well for water, his return was intercepted, and one blow with a stone hatchet laid him dead at the murderers' feet. The hut was robbed and a shepherd brought to the homestead the Pad intelligence. A party started next day in pursuit of the natives, but I have often felt thankful that we failed in finding them. On two occasions our men were attacked, but they resisted successfully and their assailants retired. Frequently small numbers of sheep were missing, but beyond this, and the stealing of small things when allowed to come near a station, the natives never injured us. I attribute our immunity to having issued orders, which were enforced, that the natives should on no pretext be harbored about any station. They are most expert thieves. I remember seeing a woman who was employed in gathering potatoes quietly raise a large proportion with her toes, and place the potatoes in her wallet, the others being openly put into the receptacle provided by the employer. Another gentleman, surprised at the rapidity with which his crop withered away, examined and found that the tubers had been removed and the stems placed in the ground again.

The place where the Messrs. Learmonths' hut-keeper was murdered was called Murdering Valley. It is near the south-western boundary of the borough of Sebastopol, and was, a few years ago, the scene of a more horrible tragedy than that of the murder by the aborigines. Once in 1842 the natives were troublesome on Mr. Inglis' run at Ballan. They had offered some insult to a hut-keeper's wife and all the European force of the station turned out with tin kettles, pistols, sticks and other instruments of noise and defence or offence—a great noise and demonstration were made to terrify the natives and thus that trouble was got over. Mr. Hastie says that when he first came to Buninyong the natives were "comparatively numerous". They used to come to the manse for food, in return for which they would fetch or break up fire wood.

As a pendant to the Rev. Mr. Hastie's picture of pre-auriferous Ballarat, the following, given to the author by Henry Hannington, will further help to illustrate the "origins" of the place. Mr. Hannington says:—

I was several times about Ballarat before the diggings in 1851. In the year 1844 I was driving a team of bullocks for Mr. Duncan Cameron, of Pascoe Vale, from his station. Yuille's Swamp (Lake Wendouree) was a camping place for teams, and the bullocks generally made off for the flat by Golden Point, where the grass was always green in the driest of summers. The timber on the flat was white gum, not thick. The creek opposite to Golden Point was shallow, about 15 inches deep. There was one water hole near Grimley's Baths (between Bridge Street and the Gas Works). I used to see a log hut or two about when I went after the bullocks, and some sawyers and splitters had huts and a few cattle on the ranges. The road from the Grampians to Geelong and Melbourne was the same as at present. It went past where the Unicorn Hotel is (opposite to the Post Office), then round Dan. Fern's corner (Albert Street), across the creek near Golden Point, and then to Buninyong, to the publichouse kept by Mrs. Jamieson, who was called Mother Jamieson. From there it went to Fisken's, near the Lal Lal Falls, for water for the teams. We had several visits from the black lubras. The blackfellows seldom came with them. We all had to carry firearms, as the blacks were treacherous, and were spearing hut keepers and others every day. I got safe with my team to Moonee Ponds, Pasco Vale, and had to come back to the Ballarat District in 1845, as there was an order from the Government for a few free men to join the new mounted police, and I was sent to Mr. Edward Parker, the protector of the blacks at Jim Crow Creek (Daylesford). I had nothing much to do. Went once a week for the mail, and was often about Ballarat looking up horses, as they always made for the flat opposite Golden Point. Everything looked then pretty much as it had the year before.

Hannington is only one of the vouchers for the water supply of the Yarrowee valley, but as old or older settlers than he tell us, as we have in part seen already, of the occasional drying up of what now seems to be permanent waters. Thus, one of the Learmonths writing to the Corn Stalk, in April, 1858, says:—

When we discovered the country around Burrumbeet, in January, 1838, there were then a few inches of intensely salt water in the lake. In June of that year the water dried up, and in the three following years Lakes Burrumbeet and Learmonth were quite dry and covered with coarse grass, which the cattle and sheep fed over, and which was burned in each of these summers. There was a little water in the middle of both lakes not evaporated at the end of the summer of 1842, and since then there was a gradual increase in both till 1852 when it reached its maximum and has been fluctuating since then. All the swamps and most of the springs that now supply water were perfectly dry, or nearly so, in the years 1839, 1840, 1841. The Moorabool did not run in these years, and the Leigh and the Barwon only for a few weeks, and then not more than knee deep. During these dry seasons Burrumbeet was fringed with a sort of myrtle, which must have been growing there for some time, for the trees had attained a considerable size, as may be seen by their stumps and roots which are still visible a hundred yards within water mark. With regard to Yuille's Swamp, from which Ballarat is supplied with water, it also was dry in the years I have mentioned, but the water in it, when the winter rains did not fail, was always good, which was not the case with many of the lagoons in the district.

Mr. Waldie corroborates Mr. Learmonth as to Yuille's Swamp, and Mr. Learmonth, with smaller, other eyes than those of subsequent water-supply caterers, remarks that if Yuille's Swamp were improved by feeders from Waldie's Creek "very inexpensive works would furnish Ballarat with an abundant and cheap supply of water at all times."

Hannington, like many another waif of the old days, seems, as we shall see by and bye, to have got stranded in the shallows whilst other craft about him swept on to fair havens. The squatters, too, were not fixed like the land they occupied, for they had their exits and their entrances, as we have seen, and many departed for good and all. It was thus with the Learmonths eventually, albeit they remained for many years after the date of the days of which we are now treating. Their Buninyong pre-emptive they let on a mining lease and after that they sold the hind. Still holding the Ercildoun estate, they ventured, themselves, some years later, upon the fortunes of mining, and took a quartz mine at Egerton, appointed a manager, won a good deal of gold, then sold the mine and sued the vendees, including the manager, who had sold as the vendors' agent and then joined the vendees. But this matter is dealt with further down the stream of our story. Not long after the law suit the last of the Learmonths left the colony or was dead. Ercildoun, the place where their famous merino flocks had borne them so many golden fleeces, was sold to Sir Samuel Wilson, and he eventually became an absentee, living in Earl Beaconsfield's house of Hughenden, and after some defeats becoming a member of the House of Commons, where he now sits as representative for Portsmouth.

Ballarat, or, more properly, Ballaarat, is a native name, signifying a camping or resting place, balla meaning elbow, or reclining on the elbow; all native names beginning with balla have a similar significance. Wendouree is the anglicised form of Wendaaree, a native word, signifying "be off", "off you go." Yarrowee is probably a Scottish settler's use of the Scottish Yarrow, with a diminutive to suit the smaller stream. Buninyong, or, as the natives have it, Bunning-yowang, means a big hill like a knee—bunning meaning knee, and yowang hill This name was given by the natives to Mount Buninyong because the mount, when seen-from a given point, resembled a man lying on his back with his knee drawn up. The Yow-Yangs, by the Werribee, is a form of Yowang. Station Peak, one of the Yow-Yangs, was called Villamata by the natives. Warrengeep, corrupted to Warrenheip, means emu feathers; the name was given to Mount Warrenheip from the appearance presented by the ferns and other forest growths there. Gong Gong, or Gang Gang, is an aboriginal name for a species of parrot; Burrumbeet means muddy water, and Woady Yaloak standing water. Mount Pisgah, in the lake country, was first known as Pettett's Look-Out, and Mount Rowan as Shuter's Hill. Mount Blowhard had no name among the settlers until one of Pettett's shepherd-boys gave it that name, from having often proved the appropriateness of such a designation, since his experiences of windy days there had been frequent.

As a race the Australian squatters were brave and adventurous. Many of them were men of liberal education and broad and generous culture, and some were men bearing old historic names, as well as possessing the instincts and the discipline of gentlemen. Others were vulgar boors, whose only genius lay in adding Hock to flock, run to run, and swelling annually the balance at their bankers. The first squatters took their lives in their hands, for they had to fight with various enemies—a treacherous native population, drought, hunger, and on all sides difficulties. Says Mr. Coghill, in a viva voce [4] communication to us:—

Every day, I may say for ten years, I have been many hours in the saddle. I never had much trouble with the natives, only that they would sometimes thieve a little; but I used always to make a point of going to them and talking to them as well as I could, and explaining to them that if they behaved themselves they would not be molested. I remember the bother we had with our first wool. We did not know how to get it down to ship, and we thought we would send it by way of Morrison's station, on the Campaspe. We had to cross the Jim Crow ranges, and we were a week among the gullies and creeks there before we could get a passage with our wool across the ranges.

The squatters were essentially explorers, and encountered all the risks of exploration. Over mountain and valley, through forest and across plain, they went where everything was new to civilisation. Passing by arid, treeless, grassless wastes, mere howling wildernesses of desolation, they pursued their way to tracts of boundless fertility, lands flowing, prospectively, with milk and honey, potentially rich in corn, and wine, and oil. Ever among the virgin newness of an unsubdued country, they steered their course by by guided by the sun or the compass; at night, led by the skies, as, to quote the great New England poet's melodious, child like conceit.

This may seem to be a romantic view of the squatter, but it is a real one. It is as real as the cutty pipes, the spirit flasks, the night rugs, the camp fires, the rivalries, ambitions, generous hospitalities, and occasional meannesses of the race. Doubtless they sought their own good, hut, however unwittingly, they actually became the beneficial occupiers of the laud for others. The teeming hosts drawn hither afterwards by the more dazzling hopes of fortune, and becoming eventually, and not without reason, hostile to the squatter, were in great part fed by the countless flocks and herds which the pastoral pioneers had spread over the wide pastures of this fair and fertile home of all the nations. With what to the squatter must have seemed like rash and boisterous violence, the sudden tide of population dashed its confluent waves upon our shores, and the serried ranks of the new army of industry marched boldly in upon the domains of the squatter, rudely disturbed his quiet dreams of perpetual occupation, and added at once a hundredfold to the market value of all his possessions.

From the first pastoral settlement to the discovery of gold there was a wool-growing, cattle-breeding period of something more than one decade. In that period the courage and the enterprise of the squatters, the real pioneers of all our settlement, had achieved no little in the direction of the development of the value of the main source of all national wealth—the land. Mr. M'Combie, in his "History of Victoria", remarks of the early years of settlement:—

During the ten years that the province of Port Phillip had been settled, it had been daily progressing in population and wealth. Vast interests had been silently growing up, and new classes were beginning to emerge into importance. All depended upon the land. The first wealth of Port Phillip was acquired from pastoral pursuits, and nearly every person was either directly or indirectly engaged in squatting.

But while those "vast interests had been silently growing up",

there had been occasional premonitions of a rapid and turbulent

change. While the shepherds fed their flocks by night and by day,

other voices than those of angels in the air were heard in some

places. In some of the more picturesque nooks of the district

traversed by the Pyrenees and their off-shoots, the solitary

shepherd, or squatter, on one or two occasions, or oftener still,

saw sudden visions of easily won and boundless immediate wealth.

Where the broad belts of purple forest spread out, and fair green

glades and glens and ravines stretched over the swelling ranges

of the district, the bushman wandered from silence to silence

that only the elements or the birds of the native woods ever

disturbed. Then it was that the first whisperings were heard of

the rich secrets of the unmeasured geologic ages, and the first

gleams were caught of the visions that had in them, however dim

and formless then, the promise of a more brilliant epoch. But it

may be well supposed that those hardy pioneers recked not then,

even as they knew not, of the troubles that would fall to the

squatter with the sturdy democracy of the then coming time. They

were lords of all they surveyed. Of all earth-hungerers, they

were, assuredly, among the hungriest, for, as Westgarth says,

they had "a cormorant capacity for land". Over tens of thousands

of acres of broad lands they roamed in the jocund spirit of

undisputed occupation, and the still broader future lay

unexplored, though even then the democratic invasion was

imminent. The visions we wot of had been seen, but if seen were

not all revealed. They were not at once blazoned forth to the

public ear, but stealthily treasured or stealthily told, for

instinct of change, of hope, of fear, more or less held back all

who had seen the bright spectacle. The governing authorities

heard of the things seen, and were offered proofs of the reality

of the fateful discovery; but the same instinct and horror of

change restrained them also from giving the revelations to the

world. But the secret had escaped for ever when the first

glittering speck glared as a lurid omen of evil, or lit up bright

hopes that fell like a burst of sudden sunshine upon the silent,

solitary settler. The new thing might be feared, or worshipped,

fought against or cherished by the timid or selfish possessors of

office and settlements, but it was to master all their purposes.

Thus was foreshadowed the quicker entry of Australia among the

peoples and the nations, the coming of the population from all

the corners of the earth to overrun the quiet haunts of the

squatter and the shepherd, the beginning of the new interests,

and a grander destiny for the whole continent.

Ballarat in 1852 (looking north-west from Mt.

Buninyong).

{Page 17}

THE GOLD DISCOVERY.

California and the Ural.—Predictions of Australian Gold.—Discoveries of Old Bushmen.—Hargreaves and others in New South Wales.—Effects of Discovery at Bathurst.—Sir C.A. Fitz Roy's Despatches.—First Assay.—Esmond and Hargreaves.—Esmond's Discovery at Clunes.—Previous Victorian Discoveries.—Esmond's the First Made Effectively Public.—Hiscock.—Golden Point, Ballarat.—Claims of Discoverers as to Priority.—Effects of the Discovery.—Mr. Latrobe's Despatches.—His Visit to Ballarat.—The Licenses.—Change of Scene at Ballarat.—Mount Alexander Rush.—Fresh Excitements.—Rise in Prices.

California electrified Europe and the United States by its gold discoveries in the years 1848-9, and that event was soon followed by the discovery of gold in Australia. Geologists who had studied maps and noted the auriferous mountain lines of the Ural and California, no sooner heard of Australian strata and the bearings of the mountains and ranges, than the existence of gold in this island continent was predicted. In the older settlements, too, of New South Wales, the aboriginies and the whites had occasionally stumbled upon glittering metals, as afterwards they did also in Victoria; but it was the Californian prospector, Hargreaves, who first publicly demonstrated the existence of gold in Australia. Actually, the discovery by others seems to have occurred both in New South Wales and Victoria about the time of the Californian rush in the year 1849. From a despatch dated 11th June, 1851, to Earl Grey from Sir C.A. Fitz Roy, then Governor of New South Wales, we learn that some two years before then a Mr. Smith announced to Sir Charles' Government the discovery of gold. A dispatch from Mr. Latrobe, the Governor of Victoria at the time of Esmond's discoveries, mentions the discovery of gold some two or three years previously in the Victorian Pyrenees. Smith was attached to some ironworks at Berrima. He showed a lump of golden quartz to the Chief Secretary in Sydney, and offered, upon terms, to reveal the locality of his discovery. The Sydney Government, if we may take the Governor's despatch as a guide, had some doubts both as to the veracity of the applicant and the propriety of making known his discovery even if a reality.

Apart (says Sir C.A. Fitz Roy) from my suspicions that the piece of gold might have come from California, there was the opinion that any open investigation by the Government would only tend to agitate the public mind, and divert persons from their proper and more certain avocations.

Then, on the 3rd April, 1851, Mr Hargreaves appeared upon the scene, Smith having vanished in refusing to "trust to the liberality" of the Sydney Government. Mr. Hargreaves was a man of greater faith than Smith, and he disclosed the localities in which he had discovered the precious metal. The localities were near Bathurst. The news spread all over the colonies, and the Bathurst and adjacent districts were rushed, to the great terror of quiet pastoral Settlers, and the annoyance of the respectable Government of Sydney. From the Governors despatches to Downing Street, it appears that the official mind was much agitated what to do. Settlers advised absolute prohibition of gold digging, and the authorities were in doubt as to whether it might be safe to impose regulations and a tax. Counsel's opinion was obtained as to the property of the Crown in the precious mineral, and ultimately a license tax of thirty shillings per month was levied upon the Bathurst diggers. The Rev. W.B. Clark, the geologist, gave excellent geological and political advice at the time, in the columns of the Sydney Morning Herald. He sagaciously remarked that "the momentary effect of the gold mania may be to upset existing relations; but the effect will be a rapid increase of population, and the colony must prepare herself for an important growth in her influence upon the destinies of the world."

The police despatches to the Sydney authorities described the miners as "quiet and peaceable, but almost to a man armed", wherefore the officer advised, "that no police power could enforce the collection of dues against the feeling of the majority." Hargreaves came to the aid of the authorities as a man strong in counsel and Californian experience. A minute of Hargreaves' is worth noting—"There existed (he says) no difficulty in obtaining the fees in California." But this was no marvel, as will be seen by the following revelation. "All the people (he continues) at the mines are honest and orderly. I was alcadi there. If a complaint be made the alcadi summonses a jury, and the decision is submitted to. A man found guilty of stealing is hung immediately." This was not less direct as a system of jurisprudence than that practised, as Dixon and Dilke tell us, by the sheriff of Denver, on the buffalo plains of America, where criminals had a very brief shrift and a quick nocturnal "escape" up the gallows tree. Yet we do not learn that in Denver, or anywhere else in that part of America, "all the people" were either honest or orderly, as Alcadi Hargreaves says they were in California. But then the Sydney prospector left his aleadiship in the early days, when the Arcadian simplicity of mining society had not yet lost the fresh bloom of what we will take to have been its early and honest youth. The Bathurst diggers appear to have behaved pretty well on the whole.

In July, 1851, occurred what the Sydney Morning Herald called "a most marvellous event", namely, the discovery of a mass of gold 106 lbs. weight imbedded in quartz. This made everybody wild with excitement. The Bathurst Free Press, of 16th July, said—"Men meet together, stare stupidly at each other, talk incoherent nonsense, and wonder what will happen next." Some blacks in the employment of a Dr. Kerr found this prize, their master appropriated it, and gave the finders two flocks of sheep, besides some bullocks and horses. Possibly this was the basis of Charles Reade's great nugget incident in his "Never Too Late to Mend". It may be noted here that last November the discovery of a similar mass took place at Braidwood, in New South Wales. The weight of the specimen was given at 350 lbs., of which two-thirds were estimated to be pure gold. We may conclude this notice of the discovery of gold in New South Wales by quoting the first assay of gold as given in the Government despatches from Sydney, under date 24th May, 1851. This assay was as follows:—

| humid

process. |

| | |

dry

process. |

||

| Gold. . . . . . | 91.150 | | | Gold. . . . . . . . . . . | 91.100 |

| Silver . . . . . | 8.286 | | | Silver . . . . . . . . . . | 8.333 |

| Iron . . . . . . | 0.564 | | | Base Metal . . . . . | 0.567 |

| ———— | | | ———— | ||

| 100.000 |

| | 100.000 |

||

| Or 22 carats, £3 17s. 10½d. per oz., plus 1 dwt. 16 gr. silver, value 5½d. | ||||

Victoria was not long behind New South Wales in finding a gold-field, and it soon caused the elder colony to pale its ineffectual fires in the greater brilliance of the Victorian discoveries. James William Esmond was to Victoria what Hargreaves was to New South Wales. Esmond, like Hargreaves, had been at the Californian gold-fields, and had an impression that the Australian soil was also auriferous. He left Port Phillip for California in June, 1849, observed that there were similarities in soil and general features between Clunes and California, and decided to return and explore his Australian home for gold. It chanced that Esmond and Hargreaves were fellow passengers on their return from California to Sydney. Esmond found gold on the northern side of the hill opposite to Cameron's, subsequently M'Donald's pre-emptive right, at Clunes, on Tuesday, the 1st of July, 1851, and gold was found about the same time at Anderson's Creek, near Melbourne.

According to a letter written by Esmond to the Ballarat Courier on the 4th November, 1884, it appears that the above dates may be shifted a little. Esmond says in his Courier letter:—

On the 29th of June, 1851, I discovered gold in quartz and alluvial at Clunes, and brought it to Geelong. I showed the same to William Patterson, then watchmaker, afterwards assayer for the Bank of Australia, who tested the samples in the presence of Mr. Alfred Clarke, of the Geelong Advertiser, who reported my discovery on the following Monday, the 8th July, 1851. During that week I never heard of any gold discovery having been made or spoken of, except the discovery at Clunes. Previous to the discovery of gold in California, it was reported that a shepherd on McNeil and Hall's station at the Pyrenees discovered a lump of gold, and that he sold it to a person named Brentani, a jeweller in Melbourne. Captain Dana and his black troopers were sent up to ascertain if there was any truth in the reported discovery. A few people assembled on the ground to seek for the precious metal, but they all failed. I was living in the locality at the time, but did not go to the rush, believing it to be a hoax; but I thought differently after returning from the Californian diggings, which I visited in 1849. Anderson's Creek was the first diggings I heard of after Clunes was opened, Mr. Mitchell being the discoverer, and Buninyong was the next, by Mr. Hiscocks. * * * In a few weeks afterwards I returned to Clunes, and collected a sample of gold, some 8 oz. or 9 oz., which I sent to Mr. Patterson, of Geelong. This was the first sample of gold sold or produced in the Victorian market. My object in writing this letter, sir, is to inform the public where the first payable gold-field in the colony of Victoria was opened, and what I state I don't think any person will dispute.

Esmond published his discovery in Geelong on the 6th of July, Hargreaves having preceded him in the sister colony by some two months. But we have seen that before Hargreaves there was a Smith, who would not accept the terms of the Sydney Government, and so disappeared. There was yet another discoverer earlier than the man of the Berrima ironworks. Mr. John Phillips, late Government mineralogical surveyor, and then mining surveyor for the Victorian Government at St. Arnaud, discovered gold in South Australia before any of the explorers previously mentioned. He announced his discoveries to the authorities in South Australia and Port Phillip, and to Sir Roderick Murchison, but neither of the local Governments acted upon his discovery. The discovery by Mr. Phillips was about synchronous with discoveries made by the Rev. W.B. Clarke, and had been foreshadowed in the geological predictions of Sir Roderick Murchison and Count Strzelecki. Mr. Phillips got nothing for his pains, and Esmond was less fortunate than Hargreaves in the matter of public recognition and reward. To Hargreaves were voted £10,000 by the Government of New South Wales, and subsequently £2381 by the Victorian Parliament, Esmond, after a hard light, receiving a vote of £1000 from the Parliament of Victoria, and some small public, quasi-public, and private rewards besides. But he did not receive the amount all at once, though early proposed. On the 5th October, 1854, Dr. Greeves proposed, in the Legislative Council, a vote of £5000 to Hargreaves, and in his speech he admitted that Esmond was "the first actual producer of alluvial gold for the market." The motion was carried. Mr. Strachan moved, supported by the late Mr. Haines, and only seven others, an amendment for giving £1000 each to Hargreaves, Esmond, Hiscock, Mitchell, and Clarke, and £500 to a Dr. Bruhn, who was said by Dr. Greeves to have advised Esmond as to the existence of gold in Victoria. There was an earlier discovery than Esmond's in Victoria, asserted by Mr. J. Wood Beilby, as the repository of a secret from the person who was said to have been the actual discoverer. But Beilby does not claim for public revelation, but only as the revealer to the Government of the day. In a pamphlet published by Dwight, of Melbourne, in Beilby's interests as a claimant for State reward, the following statement is found:—

Mr. J. Wood Beilby establishes, by the production (from the Chief Secretary's office) of his correspondence with Mr. La Trobe, and concurring documentary evidence, the fact that, so early as 7th June, 1851, or some weeks earlier than Mr. Wm. Campbell, he informed the Government of the existence of gold in workable deposits at the locality now known as Navarre, and in the ranges of the Amherst district. Mr. B. does not claim to have been the original discoverer, but to have placed the information before Government, for the benefit of the public, at the critical period when its value in arresting the threatened exodus of our population to Bathurst was immense. Mr. La Trobe was at first very incredulous, evidently not having been made aware previously, of the existence of gold as one of the mineral products of Victoria, as his reply, by letter of 11th June, 1851, demonstrates. Mr. B., however, supplied further details of information, and, waiting upon him personally, so urged investigation, offering to share expenses, that Mr. La Trobe organised a prospecting party, including Mr. David Armstrong, then a returned Californian digger, afterwards gold commissioner, and the late Capt. H.E.P. Dana, attended by a party of native police; Mr. Commissioner Wright, resident at the Pyrenees, being nominated to act with the gentlemen of the party as a board of enquiry. From various causes the expedition was delayed starting from the Aboriginal Police Depôt, Narree Worran, until a few days before the publication of Mr. Campbell's letter. But the news was made public. Although Mr. La Trobe had requested Mr. Beilby to abstain from further publication of the fact until the result of his investigations, the officials named to accompany the expedition, and their subordinates and outfitters, were not tongue-tied or bound to secrecy. It is, therefore, no matter of surprise that their intended prospecting trip to the Pyrenees was bruited far and wide; and, as a sequence, their investigations forestalled by the discoveries at Clunes.