a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Northing Tramp Author: Edgar Wallace * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1100561h.html Language: English Date first posted: Aug 2012 Most recent update: Apr 2015 This eBook was produced by Brent Beach and Roy Glashan from the 1929 US edition. Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

The Northing Tramp, 7/6 first edition, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1926

| Chapter I Chapter II Chapter III Chapter IV Chapter V |

Chapter VI Chapter VII Chapter VIII Chapter IX Chapter X |

Chapter XI Chapter XII Chapter XIII Chapter XIV Chapter XV |

The Northing Tramp, 3/6 reprint, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1926

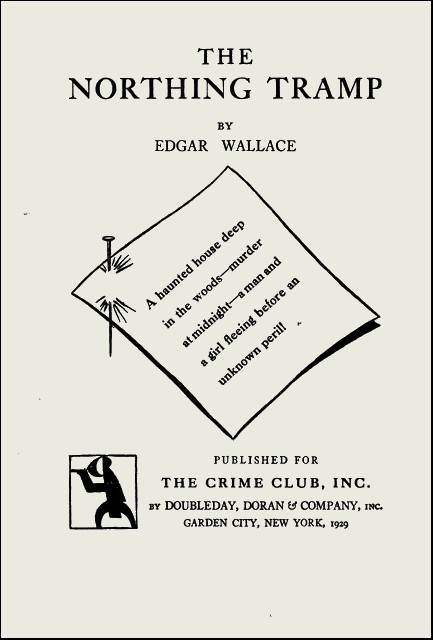

"The Northing Tramp," Title page of 1929 US edition

THE tramp looked to be less savoury than most tramps; and more dangerous. For he was playing with a serviceable automatic pistol, throwing it from one hand and catching it with the other, balancing its muzzle on his forefinger with an anxious eye as it leaned first one way and then another; or letting it slip through his hands until the barrel was pointing earthward. This pistol was rather like a precious plaything; he could neither keep his eyes nor hands from it, and when, tired of the toy, he slipped it into the pocket of his tattered trousers, the disappearance was momentary. Out it came again, to be fondled and tossed and spun.

"Such things cannot be!" said the tramp aloud, not once, but many times in the course of his play.

He was unmistakably English, and what an English tramp was doing on the outskirts of Littleburg, in the State of New York, requires, but for the moment evades, explanation.

He was not pleasant even as tramps go. His face was blotched and swollen, he carried a week's growth of beard, one eye was recovering from the violent impact of a fist delivered a week before by a brother tramp whom he had awakened at an inconvenient moment. He might explain the swelling by his ignorance of the properties of poison ivy, but there was nobody interested enough to ask. His collarless shirt was grimy, his apology for a jacket had bottomless pits for pockets; on the back of his head, as he juggled the pistol, he maintained an ancient derby hat badly dented, the rim rat-eaten.

"Such things cannot be," said the tramp, who called himself Robin ... the pistol slipped from his hand and fell on his foot. He said "Ouch!" like a Christian man and rubbed the toe that was visible between upper and sole.

Somebody was coming through the little wood. He slipped the pistol into his pocket and, moving noiselessly between bushes, crouched down.

A girl, rather pretty, he thought; very slim and graceful, he saw. A local aristocrat, he guessed. She wore a striped silk dress and swung a walking stick with great resolution.

She stopped almost opposite him and lit a cigarette. Whether for effect or enjoyment was her own mystery. Not a hundred yards away the wood path joined the town road, and a double line of big frame houses were inhabited by the kind of people who would most likely be shocked by the spectacle of a cigarette-smoking female. "Effect," thought Robin. "Bless the woman, she's going to set 'em alight!"

From where he crouched he had seen the look of distaste with which she had examined the feebly smoking cylinder. She puffed tremendously to bring it into working order and then went on. He rather sympathized with people who shocked folks: he had shocked so many himself, and was to continue.

Leisurely he returned to the path. Should he wait for nightfall or make a circuit of the town? There must be a road west of the rolling mills to the north or past the big cheese factory to the south. Or should he walk boldly through the main street, endure the questions and admonitions of a vigilant constabulary, and risk being run out of town so long as they ran him out at the right end? He had elected for the first course even before he gave the matter consideration. The town way was too dangerous. Red Beard might be there, and the fat little man who ran so surprisingly fast and threw knives with such extraordinary skill.

Another pedestrian was coming—walking so softly on rubber shoes that Robin did not hear him until too late. He was a lank young man, very smartly dressed, with a straw hat, adorned with a college ribbon, tilted over his right eye. The buckle of the belt which encircled his wasp waist and supported nicely creased trousers was golden, his shirt beautifully figured. He might have just walked out of any ad. page of almost any magazine.

The rather large mouth twisted in a grin at the sight of the ragged figure sitting by the path side.

"'Lo, bo!"

"'Lo!" said Robin.

"Going far?"

"Not far—Canada, I guess. I'll get ferried over from Ogdensburg."

"Fine: got your passport 'n' everything?"

Sarcasm was wasted on Robin.

"I'll get past on my face," he said.

The young man chuckled and offered a very silvery case, thought better of it, and withdrew the cigarette himself. Robin respected the precaution; his hands were not very clean.

He lit the cigarette with a match that he took from the lining of his hat, and smoked luxuriously.

"You won't find it easy. Those Canadian police are fierce. A fellow I know used to run hooch across, but you can't do that now—too fierce."

He was enjoying his condescension, his fellowship with the lowly and the possibly criminal. He was broad-minded, he explained. He had often talked with the genus hobo and had learned a lot. Only a man of the world could talk with tramps without loss of dignity. One need not be common because one associated with common people.

"That's what I can't get our folks to understand," he complained. "Old people get kind of narrow-minded ... and girls. Colleges ruin girls. They get stuck up and nobody's good enough for 'em. And Europe ... meeting lords and counts that are only after their money. I say 'See America first.'"

Robin the tramp sent a cloud of gray smoke up to the pine tops.

"Somebody said it before you," he suggested. "It sounds that way to me."

The young man's name was Samuel Wasser. His father kept the biggest store in Littleburg—Wasser's Universal Store. Samuel believed that every man was entitled to live his own life, and was careful to explain that a young man's own life was an altogether different life from any that was planned for him by people who were "past it."

"I made seven thousand dollars in one year," he said. "I got in with a live crowd fall before last. But the Canadian police are fierce, and the Federal officers are fiercer—still, seven thousand!"

He was very young; had the joy of youth in displaying his own virtues and superior possessions. He rattled certain keys in his pocket, hitched up his vivid tie, looked despisingly at the main street of Littleburg, and asked: "Did you see a young lady come along? Kind of stripey dress?"

Robin nodded.

"I'm getting married to-night," said Samuel lugubriously. "Got to! It's a mistake, but they're all for it. My governor and her uncle. It's tough on me. A man ought to see something of life. It isn't as though I was one of these country Jakes, jump at the first skirt he sees. I'm a college man and I know there's something beyond, a bigger world"—he described illustrative circles with his hands—"sort of—well, you know what I mean, bo."

Robin knew what he meant.

"Seems funny talking all this stuff to you, but you're a man of the world. Folks look down on you boys, but you see things—the wide-open spaces of God's world."

"Sure," said Robin. The tag had a familiar ring. "Where men are men," he added. He had not seen a movie show since—a long time; but his memory was retentive.

"Have another cigarette. Here, two. I'll be getting along."

Robin followed the dapper figure of the bridegroom until it was out of sight. He wished he had asked him for a dollar.

Looking up into the western sky, he saw above the dim haze that lay on the horizon the mass of a gathering storm.

"Maybe it will come soon," he said hopefully.

Red Beard did not like rain, and the fat little man who threw knives loathed it.

MR. PFFIEFER was a stout man with a sense of humour; but since he was a lawyer having his dealings with a dour people who had one public joke which served the whole county when recited at Farmers' Conventions, and one private obscenity which, told in a smoky atmosphere 'twixt shuffle and cut, had convulsed generations of hearers, he never displayed the bubbling sense of fun that lay behind his pink mask of a face.

He could have filled his untidy office with unholy laughter now, but he kept a solemn face, for the man who sat on the opposite side of a table covered with uneven mounds of paper, law books, and personal memoranda was a great personage, a justice of the peace and the leading farmer in the county.

"Let me get this thing right, Mr. Pffiefer." Andrew Elmer's harsh voice was tense with anxiety. "I get noth'n' out of this estate unless October is married on her twen'y-first anniversary?"

Mr. Pffiefer inclined his head gravely.

"That is how the will reads." His podgy fingers smoothed out the typewritten document before him.

To my brother-in-law twenty thousand dollars and the residue of my estate to my daughter October Jones to be conveyed on the marriage of my daughter on or before the twenty-first anniversary of her birth.

Andrew Elmer scratched his head irritably.

"That lawyer over in Ogdensburg figured it out this way. I get twenty thousand dollars anyway. Then when October marries—"

"Who is responsible for this curious instrument?" interrupted the lawyer.

Andrew shifted uneasily.

"Well, I guess I drew it up. Jenny left most all her business to me."

He was a thin man with a hard, angular face and the habit of moving his lips in silent speech. He held long conversations with himself, his straight slit of a mouth working at a great speed though no sound came. Now he spoke to himself rapidly, his upper lip going up and down almost comically.

"Never was any reason to have this thing tested," he said at last. "Jenny's money was tied up in mortgages an' they only just fell in. It was that bank president over at Ogdensburg that allowed I didn't ought to touch the money till October was married. I figured it out this way. That the residoo's all that concerns her ..."

"Is there any residue, Mr. Elmer?"

There was a certain dryness in the lawyer's tone, but Elmer saw nothing offensive in the question.

"Why, no; not much. Naturally there's always a home for October with me an' Mrs. Elmer. That's God's holy ord'nance—to protect the fatherless an' everything. She's been a great expense—college an' clothes, an' the wedding'll cost something. I figured it out when I drawed up that will..."

Mr. Pffiefer sighed heavily.

"Your legacy is contingent—just as October's is contingent. When is the wedding to be?"

Like a ghost of wintry sunlight was the fleeting brightness which came to Elmer's harsh face.

"To-night; that's why I dropped in to see you. Mrs. Elmer figured it this way: you can be too economic, says she. For a dollar 'r so you can get the law of it, so's there'll be no come-back. I'd feel pretty mean if after October was out of the—was fixed up, there was a rumpus over the will."

"Marrying Sam Wasser, ain't she?"

Mr. Elmer nodded, his eyes fixed on the buggy and the lean horse that was hitched just outside the window. That cadaverous animal was eating greedily from the back of a hay wagon which had been incautiously drawn up within reach.

"Yeh—Sam's a nice feller."

He ruminated on this for a while.

"October's kind of crazy—no, not about Sam. Obstinate as an old mule. She goes mad—yes, sir. Seen her stand on the top of the well an' say, 'You touch me an' I'll jump right in'—yes, sir. Sparin' the rod's the ruin of this generation. My father took a slat to all of us, boy an' girl alike. An' I'm her guardian, ain't I? Mrs. Elmer reckons that a spankin' is just what October wants. But there it is—she didn't holler 'r anything, just walked to the well an' said, 'If you beat me I'll jump in.' I figure that self-destruction is about the wickedest thing anybody can talk about. It goes plumb clean in the face of divine Providence. That's October. She'll do most anything, but it's got to be done her way. Sam's a nice, slick young feller. His pa's got building lots and apartment houses down in Ogdensburg, besides the store, and Sam's made money. I'm not sayin' that I'd like to make profit on the degradation—to the level of the beasts in the field—of my fellow critters, but the money's good."

The lawyer pieced together and interpreted, from this disjointed evidence of October's wickedness and Sam Wasser's virtues, a certain difficulty in the operation of match-making.

"October's just as hard as a flint stone. She's never found grace, though me an' Mrs. Elmer's prayed an' prayed till we're just sick of prayin' an' Reverend Stevens has put in a whole lot of private supplications to the Throne. I guess Satan does a lot of work around these high schools."

There was a silence. Mr. Elmer's long, shaven upper lip wrinkled and straightened with uncanny rapidity. The fascinated Mr. Pffiefer, a student of lip reading, saw words: "October," "Giving trouble," and, many times, "money."

He became audible.

"You never know where you're at with October. S'pose you say 'October, there's a chicken pie for dinner,' she says 'Yes.' And when you hand out the plate she says, 'I don't eat chicken pie,' just like that. Don't say anything till you push the plate at her."

Mr. Elmer relapsed into silence; evidently his mind had reverted to the will. The lawyer read "residue" and "hell" and other words.

"She's fast, too. Smoking on Main Street only this morning, and after I prayed an' Mrs. Elmer almost went down on her knees."

"What was the great idea?" Mr. Pffiefer permitted himself the question. "This will, I mean. Why residue, why marriage, before October's twenty-first anniversary?"

Mr. Elmer glanced at him resentfully.

"Jenny believed in marryin' young, for one thing. And that's right, Mr. Pffiefer. The Psalmist said, 'A maid—'"

"Yes, yes," said the lawyer, a little testily, "we know what he said. But David never was my idea of a Sabbath school teacher. Mrs. Jones's views are understandable. But fixing the will that way—I can't get round that, somehow. Almost looks as if it was a bribe to get October off your hands."

His bright eyes transfixed Mr. Elmer for a second, but that worthy and conscientious man stared dumbly through the window. If he heard the challenge he did not accept it.

"Almost looks," said Pffiefer, with a hint of rising heat, "as if this humbug about the residue of an estate which palpably and obviously has no existence was a lure to a likely bridegroom. Sounds grand, 'residue of my estate,' but so far as I can see, Elmer, there are ten acres of marsh and a cottage that no man or woman could ever live in—say five hundred dollars ...?"

He jerked his head on one side inquiringly.

"Twen'y-five hundred dollars," murmured Mr. Elmer. "Got a feller over from Ogdens to value it. He said the new Lakes canal might be cut right through that property. What'll I be owing you, Mr. Pffiefer?"

The lawyer's first inclination was to say "Nothing," but he thought better of that.

"Ten dollars," he said briefly, and saw the old man wince.

Mr. Elmer paid on the nail, but he paid with pain. At the door of the office he paused. A thought occurred to the lawyer.

"Say, Mr. Elmer, suppose Sam doesn't want to marry? He's got kind of smart lately. And he has more money than seems right."

Mr. Elmer shifted uncomfortably.

"Sam's a worker," he said. "He's made money out of real estate—"

"Where?" asked the other bluntly. "I know as much about realty in this country as the next man, and I don't remember seein' Sam's name figurin' in any deal."

Mr. Elmer was edging to the door.

"I think the rain'll hold up long enough to get in the corn," he stated. "Roots are just no good at all. Maybe I'll get you to fix that new lease I've gave to Orson Clark."

On this good and promising line he made his exit.

Mr. Pffiefer saw him climb slowly into the buggy and untie the reins. He had touched a very sore place; Mr. Elmer was panic-stricken. And there was every reason why he should be.

Give a dog a bad name and hang him. Give a man, or, worse, a woman, a name which is neither Mary nor Jane but hovers somewhere about the opposite end of the pole, and she attracts to herself qualities and weaknesses which in some ineffable way are traceable to her misguided nomenclature.

They who named October Jones were with the shades, though one of them had lived long enough to repent of his enterprise.

October, under local and topical influences, had at various times and on particular occasions styled herself Doris Mabel, and Mary Victoria, and Gloria Wendy. At the Flemming School she was Virginia Guinevere: she chose that name before she left home and had her baggage boldly initialled V. G. J.

"I guess I can't get rid of the Jones," she said thoughtfully, her disapproving eye upon the "J." "That old sea-man will kind of hang around, with his chubby little knees under my ears, all time."

"I am afraid so," said her parent wearily.

He had been a tall man, hollow cheeked, long bearded. Children did not interest him; October bored him. She had a trick of borrowing rare volumes from his library and leaving them on a woodpile or amid the goldenrod or wherever she happened to be when it started raining.

"Jones was a pretty mean kind of name," she suggested. "Can't you change it, Daddy?"

Mr. Jones sighed and tapped his nose with a tortoise-shell paper knife.

"It satisfied my father, my grandfather, and my great-grandfather, and innumerable ancestors before them—"

Her brows knit.

"Who was the first Jones?" she demanded. "I'll have to get the biology of that. I guess they sort of came out of their protoplasms simultaneous."

"-ly!" murmured Mr. Jones. "I wish you would get out of that habit, October—"

October groaned.

"What is the matter with Virginia?" she asked. "That is one cute little name."

There was nothing that was October in her appearance, for October is a red and brown month, and she was pinkish and whitish: she had April eyes and hair that was harvest colour, and she had a queer, searching habit of glance that was disconcerting. People who did not know her read into this an offensive skepticism, while in reality it was eagerness for knowledge.

As to her moral character:

Miss Washburton Flemming, Principal of the Flemming Preparatory School for Girls, wrote to her father:

...I would point out one characteristic of October's which may have escaped your observation, and that is her Intense Romanticism, which, linked as it is with an Exaltation of Spirit, may lead her into ways which we should all deplore. It is unfortunate that the dear child was denied the inestimable boon of a Mother's Love. Perhaps she is more self-controlled to-day than she was when she came under our care ...

"How much more of this stuff?" snarled Stedman Jones as he turned the page. There were three more pages and a two-page postscript. He dropped the letter on the floor.

He really didn't care how intense or how romantic October was, or how exalted she might be. While he paid her fees and her amazing extras he did not wish people to write letters to him about her or anybody or anything. He had not to buy her dresses, thank heavens. There was an income from his wife's estate administered by a lout of a brother-in-law whom he had only met twice in his lifetime and with whom, in consequence, he had only quarrelled twice.

Stedman was a bibliophile, the author of a scholarly volume of mediaeval French history, and the only time he was ever really cheerful with October was the last week of her short vacations.

Nobody ever called her Virginia or Alys or Gloria Wendy or Guinevere or anything but October: the nearest she got to an acceptable nickname was when somebody, reasoning along intelligent lines, called her "Huit." In another age she would have been a Joan of Arc; lost causes had for her an attraction which she could not resist. She was by turns a Parlour Socialist, a Worker of the World, an Anarchist, and a Good Christian Woman.

Cross October in the pursuit of her legitimate rainbows and she was terrible; thwart her, and you trebled her resolution; forbid her, and she bared her feet for the red-hot shares across which she was prepared to walk to her objective.

Her father died the second year she was at the Flemming School. She spent two days trying to be sorry—trying to remember something that made him different and dearer. She confided to the principal, who consoled her with conventional references to the source of all comfort, that she had not been greatly successful.

"There is really nothing intrinsically precious about fathers—or mothers either," she said, to the good lady's distress. "You give back people all that they give to you. Parents are only precious when they love their children—otherwise they are just Mr. Jones and Mr. Hobson. That is how I feel about Daddy. I tried hard to be sorry, but the only tear I've shed is when I got maudlin about being an orphan. There's an awful lot of self-pity about us orphans."

Miss Washburton Flemming felt it necessary to straighten a dangerous angle.

"Your father, my dear, worked very hard for you. He gave you a comfortable home, he bought you all that you have, and paid your fees—"

"He'd have been arrested if he hadn't," said October. "I'm terribly sorry, Miss Flemming, but I've just got to get this thing right from my own point of view. I don't think any other matters to me just now."

Her father left practically no money—he never had any to leave; she learned this from the big, uncouth Andrew Elmer. Mr. Jones had merely an annuity which died with him. Mr. Elmer, whom she remembered dimly, was an uncle, the brother-in-law of her mother and sole executor of her mother's estate. Incidentally, her guardian by law and soon to be her most unwilling host.

The translation from the intenseness of the Flemming School to the modified placidity of Four Beeches Farm had at first the illusion of a desirable change; it was as though she had come through the buffets and tossings of a whirlpool to calm waters. In twenty-four hours those calm waters had the appearance of a stagnant pool on which the green scum was already forming. And Mrs. Adelaide Elmer was a shocking substitute for the human contacts she had broken.

October did not rebel; rebellion was her normal state of being. The wildness of a tiger is unaffected by a change of cages; the new keeper had met with nothing fiercer than the domestic cat, and was outraged because her charge showed her teeth when she should have purred. Wise Miss Flemming had fixed an imponderable average of behaviour, balancing periodic atheisms against rhapsodical pieties, and discovered a standard of spiritual excellence which was altogether admirable. Mrs. Elmer lacked the qualities of discrimination. She was, in truth, on the side of uncharity, having been strictly trained in a school which enjoined obedience to parents, blind faith in the Holy Word, and the meek and awe-stricken silence of all children in the presence of their elders.

The Reverend Stevens was called in, his assistance invoked. He came one Saturday afternoon, bringing in his large hand three little books of counsel and comfort. October was not impressed by him, and in truth his education had been of an intensive character and there were certain appalling gaps which only social experience or innate goodness of heart could have bridged.

"He has all the thrones and oil paintings of theology, but there is no carpet on his floor and he eats with his fingers," said October metaphorically.

Mrs. Elmer, who took this literally, was momentarily paralyzed.

"A nicer man never lived"—her voice was a cracked falsetto when she was agitated—"and he uses a knife and fork same as you, October. I never heard a wickeder story."

October did not argue. She never argued unless there was a victory to be gained.

The proposal that she should marry, nervously offered by Elmer, was accepted with remarkable patience.

"Really?" October was interested. "Who have you got?"

Andrew repressed a desire to expatiate on the coldbloodedness of the question.

"I been talking to Lee Wasser ..." he began.

The next day Samuel was introduced. He was rather sure of himself and he spoke unceasingly on his favourite topic. October listened with downcast eyes. When he had gone she asked:

"Does this young man know anybody besides himself?"

Mr. Elmer did not understand her.

Samuel brought flowers and candy and new facts and anecdotes which showed him in an heroic light. He had a neat turn of humour and a gift of repartee. He told her all about this. His conversation was larded with: "So I says to Ed," and "So Al says to me," and he invariably concluded every such narrative with the assurance: "I thought they'd die laughin'."

Once she asked if anybody had ever died in these happy circumstances, and he was taken aback.

"Well ... I mean ... of course they didn't die. What I meant was ... well, you know."

He went home that night with his mind clouded with doubt. Once, when they were alone, sitting on the porch on a hot June night, he grew sentimental, tried to kiss her. It was his right, as he explained afterward. There was no unseemly struggle or resistance, no lips seeking lips and pecking at an ear. She held him back with one athletic hand and asked him not to be a fool.

No date had been fixed for the wedding. The announcement on the part of Andrew Elmer that, by a clause in her mother's will, October must be married on her twenty-first birthday, came in the nature of a shock to everybody but October. When she was told, a week before the date, she merely said "Oh?"

Sam had a consultation with his father and ordered an expensive suite at a hotel romantically situated on the banks of the Oswegatchie.

Thus matters stood when Mr. Elmer had his interview with Joe Pffiefer, the man of law, and found his worst fears fully justified.

The old gray horse ambled on at his own pace; the buggy rocked from side to side as its spider-web wheels met an obstruction, and Mr. Elmer rocked with it. His shrewd eye surveyed the street. Old man Wasser was standing outside Wasser's Universal Store, running his hairy hand through and again through his mat of gray hair. His octagonal glasses had slipped down his nose, pugnacity was in the thrust of his long jaw. With his free hand he was gesticulating to point his observation. And his audience was Sam, very serious. Not the seriousness of one who was at that moment an object of admonition, but rather he seemed to have a partnership in seriousness; his manner spoke agreement. Every time the waving hand fell to thump an invisible tub Sam nodded deeply.

Mr. Elmer sniffed—he always sniffed rapidly when he was perturbed—and guided the languid gray to the broad sidewalk.

"I was just saying to Sam that it don't feel like a wedding day for nobody. Seems like when you're camping and find out round about supper time that it's been Sunday all day. It don't seem like Sunday—and it don't seem like Sam's wedding day."

Sam shook his head. It only felt like a wedding day to him because he was uncomfortable and nervous and rather unhappy.

"It ought to be—different," said Mr. Wasser, Senior, glaring up at the man in the buggy. "Ought to have a kind of excitement and—well, it ought to be different. I'm not so sure..."

He shook his head. Sam also shook his head.

"I don't see what's the matter with the day—" began Elmer.

"It's the feeling. Kind of hunch, here!" Old Wasser struck his chest. "You got to be reasonable, Andrew; you got to put yourself in my place. Sam's my only boy—can't afford to spoil his young life. That's the point. And October—her wedding day, and here was she, not 'n hour ago, on this very board walk with a cigarette an' everybody looking at her and remarking. Old Dr. Vinner and Miss Selby and the city people over at Littleburg House. And Sam—What did she tell you, Sam?"

Sam emerged from the background and testified.

"She said one man's like another man—only this morning. And she didn't love me. She said she'd as soon marry a tramp as marry me—she wasn't partic'lar. She said that a girl had to make a start somewhere an' maybe I'd do to begin with—"

Mr. Elmer drew a deep whistling breath.

"Wish she'd seen that bum I was talkin' to, she'd change her mind pretty quick," said Sam, encouraged to eloquence. "I told her that wasn't the kind of talk I liked to hear from a girl who was wearin' my betrothal ring. She took it off and heaved it at me. Said she wasn't going to limit the—what was it?—limit the expression of her personality for fifty dollars' worth of bad taste—"

"H-w-w-w!" breathed Andrew Elmer. Mr. Wasser's face was all smiling triumph.

"She said maybe she'd change her mind, she wasn't sure. That's when she told me that one man was like another as far as she was concerned."

"Sam's got the ring in his pocket," confirmed Mr. Wasser.

"She's young—" Andrew spoke urgently—"they get that way, doubt their own judgment. It's natural. She's always spoke well about you to me. I get plumb tired of hearing her talk of you. It's 'Sam this' and 'Sam that' mornin' till night. She's proud and likes to hide her feelings."

"Wish she'd hide the line she sold me," said Sam, not wholly convinced, and yet, since he was a man and young, finding a difficulty in disbelieving this story of the secret praises which had been lavished upon him.

He looked at his father. The smile had left Mr. Wasser's face; he was glum and perplexed.

"And we ought to have had her marriage deed fixed, Andrew. What's the hurry, anyway? Give these young people a month or so to think it over."

He pleaded, but could not insist. Andrew Elmer was in a sense a partner in his real estate transactions; he had unsuspected pulls, controlled a certain board of management, was in every way the wrong man to antagonize.

"It don't feel like a wedding, Andrew. No party, nothing. Kind of mean and underhand. It will do us no good."

Mr. Elmer gathered up the reins; it was the psychological moment.

"If you and Sam ain't up to Four Beeches round about nine o'clock to-night I guess I've got enough sense to know that you've backed out," he said sombrely, and laid his whip across the old gray's withers.

Anyway, he ruminated with satisfaction, he had avoided discussing the very delicate matter of October's financial position.

As he was turning at the fork, a long-bodied touring car came slowly past him. He had a glimpse of a thin-faced man at the wheel. An Englishman, he guessed by the monocle. The machine had a Canadian number. Strangers are rare in Littleburg; he turned his head and looked back after the car, saw it stop before the Littleburg House. A few minutes later he saw two men who were also strangers. A tall thickset man with a short red beard, and a fat little man whose face was broader than it was long, the breadth being emphasized by the straight black eyebrows and moustache. They were striding out side by side, the little man's head no higher than his companion's shoulder. They favoured Mr. Elmer with a quick sidelong stare and marched past with no other greeting,

"Littleburg's goin' ahead," said Mr. Elmer.

He had large interests in Littleburg real estate and had every reason to be pleased at this slender evidence of the town's growing popularity.

The two men marched on without exchanging a word and turned into Littleburg House with the precision of soldiers. A tall thin man in a long dust coat was talking to the clerk. He was an Englishman; his accent betrayed him. Good-looking, though his face and features were small; sleek-haired, a little petulant.

"... the roads are abominable. Isn't there a post road to Ogdensburg?"

The two men hardly paused in their stride: they heard this as they passed to the stairway. A stocky, sandy-haired man who had been dozing in one of the long chairs that abounded in the vestibule opened one eye as they came abreast of him, straightened up, relit the stub of his dead cigar, and followed them up the stairs. Evidently he knew their habitation, for he knocked on Number 7 and a voice barked permission to enter.

"'Morning, boys." He nodded affably to the two, and such was his perfect assurance that there was no need for him to display the silver badge that was pinned on the inside of his coat. "Heard you were in town. Stayin' long?"

Red Beard finished the glass of water he was drinking when the detective entered, wiped his moustache daintily with a silk handkerchief, and jerked a cigar from his pocket.

"Me and my friend are just stoppin' over to look 'round," he said. "We reckon to go on to Philadelphia by the night train. Thasso, Lenny?" He looked to his friend for support.

"Thasso," said Lenny.

The sandy man lit the cigar.

"Chief asked me to make a call," he said apologetically. "Thought maybe you mightn't know we'd seen you arrive. Pretty poor place—Littleburg. You'd starve here and that's a fact. Ogdensburg's not much better. The police have had a clean-up lately and they're mighty sore with folks who think they're easy. Chief was on the line to them this morning and they reckoned Ogdensburg wouldn't be healthy for you."

"Philadelphia," said Red Beard, "and we're only stopping off. Utica's our home."

"Fine," said the sandy man, by nature and training a skeptic. "Either of you boys got a gun?"

Red Beard spread out his arms invitingly, and the detective made a quick search, first of one and then of the other. No lethal weapon was discovered.

"That's fine," said the sandy man cheerfully. "I'll be seeing you at the depot about nine?"

"Sure thing," said Red Beard as heartily.

The detective went down through the vestibule and telephoned; the Englishman had departed.

"Some of these guys want the earth," complained the clerk. "'Is Lordship wants a new post road."

"English?"

"And some," said the clerk.

An hour later Red Beard and his friend came down to the lounge and were silent spectators of a ceremony.

A number of high-spirited young men of Littleburg had formed a ring about an embarrassed young man, and they were chanting a ribald chorus. Red Beard gathered from this that the young gentleman in the centre was on the verge of matrimony. They were chanting the lay of a local poet and were by now word perfect.

"Old Sam Wasser was a mean old skunk,

He keeps his hooch where it can't be drunk.

He marries a girl and he never sends

A 'come-all-ye' to his faithful friends—"

"Aw, listen, fellers!"

"There ain't no cake for the bride to cut,

No hooch for the health of this poor nut.

Old Sam Wasser is a mean old dog,

Old Sam Wasser is a mean old hog,

A mean old hog."

"Aw, listen, fellers!"

The circle broke into a formless little group from which great noises emerged.

"You are, Sam!" "And so you are ... you old skinflint!" "Aw, listen!" "Say, come along to my apartment."

The crowd billowed unevenly toward the door, Mr. Bennett, the proprietor of Littleburg House, rubbing his hands in the background and looking happy for the first time since this congregation had irrupted into his hotel.

Sam Wasser's "apartment" was above the garage of his suffering parent. Sam, who was a strangely old boy, gave little parties here at times. There were secret closets wherein the Right Stuff was stored, and an odd assortment of glasses.

Toward the end of the afternoon Sam made a suggestion.

"Lishen, fellers, got an idea. There'sh an ole hobo up in the woods, good feller—man of the world. Le's go right along an' gi'm a drink. Bet he ain't tasted the Right Stuff in years. Le's all be bums. Glor'us Fraternity Men Who Love Wide Open Spaches. Le's..."

MRS. ELMER made several visits to the bedroom. She had endeavoured throughout the day to arouse October to a sense of her responsibilities, but unsuccessfully.

"You'd break the heart of a stone," said Mrs. Elmer bitterly.

She was a terribly thin woman with a face that was all angles, and her manner was normally and permanently acidulated.

"How can I pack, October? I don't know what you want to take with you."

October put down her book and regarded the thin lady thoughtfully.

"Anything. What does a bride wear, anyway?"

It was the first spark of interest she had shown.

"Your blue, the satiny one. Mr. Elmer thought that as the wedding was to be quiet it was waste of money to buy falderals."

"Oh, Lord!" groaned October. "Who wants falderals? Anything you like, Mrs. Elmer. Not too much; I don't want the bother of unpacking."

"Can't you do anything?" demanded the exasperated woman. "Do you expect me to break my back over your trunks?"

"Don't pack 'em," said October, and returned her mind to the book.

She had her supper in her room alone. She was reading by the light of a kerosene lamp, her head on one hand, when Mrs. Elmer in rustling black came twittering in to her.

"The Reverend Stevens has come," she whispered, as though the information were too intimate to be spoken aloud.

October put down her book, carefully marked the place, and stood up, brushing back her hair with a quick gesture.

"What does he want?" she asked astoundingly.

Mrs. Elmer did not swoon.

"You're goin' to be married, ain't you?" she demanded violently.

"Oh, that!"

The long parlour at Four Beeches was at its worst a gaunt and cheerless room. All that flowers, garden-grown, could do to its embellishment had been done. The flowers gave the room a beauty and a dignity which October had not noticed before. Mr. Elmer in his Sunday best and the Reverend Stevens in funereal black were solemn figures. So were Johnny Woodgers, the hired man, and his wife, and Art Fingle, the clerk from the Farmers' Bank, and Martha Dimmock, the widow woman who was accounted Mrs. Elmer's closest and most confidential friend. October looked in vain for Sam.

"You didn't wear the blue after all," whispered Mrs. Elmer. "That dress looks too gay—"

"I feel gay," said October clearly.

The Reverend Stevens held a whispered conversation with Andrew Elmer, and Mr. Elmer went out. It was Mr. Stevens's opportunity. He tiptoed across the room. He had the manner of one in the presence of the newly deceased.

"You are about to embark upon a new life and a new career," he said; "a career which calls for the exercise of all the virtues—"

"Where is this Sam person?" demanded October. "I'd like to take one really good look at him before I decide."

"He will be here presently."

Mr. Stevens was annoyed. October had that effect on him. He, too, had need to exercise all his Christian virtues when he was brought into contact with her. To say that he disliked her intensely is to put the situation truthfully. He was looking forward to the day when she would be removed to the fold which sheltered Lutheran Wassers.

"You are about to embark upon a new—"

The sound of voices came faintly from the road outside; they must have been very loud voices to reach so far. Somebody was laughing stupidly.

"—a new career, as I say. There can only be one sure guide even in the most paltry affairs—"

The voices were so loud now that he stopped. The door was flung open, Mr. Elmer came in backward, waving his hands frantically. After him, facing first one way and then the other, came Mr. Wasser in a tail coat, very flushed and talking at the top of his voice.

The little crowd that followed exploded into the room. Sam Wasser was very noticeable. He had a flag attached to a walking cane and he waved it furiously. Hatless and bearing marks of strife, he did not differ in this respect from his elated friends.

"Here he ish! Whoop! Rush that weddin'. Yi-yap! Gerraway!" This to his frantic father.

Then, in a singsong chorus which was lustily sung by his supporters:

"Callin' your bluff, November Jones, December Jones, callin' your bluff, November Jones, September Jones—wow!"

Then it was that October saw the tramp. He was pushed forward by friendly hands and stood swaying unsteadily on his feet. His eye was glassy, his hair a little wild. Somebody had ripped his coat so that only one sleeve remained.

"Sorry," he said thickly.

Sorry? She looked at him keenly. One word, and it determined her course. Until that moment her mind was all fury and contempt.

Mr. Elmer became articulate.

"What in hell's the meaning of this?" he screeched. "Hey? What's the idea? Get out, you bunch of boozers, get out!"

"Idea?" Sam strode forward truculently. "She'd sooner marry tramp, she said. Call her bluff. Tha's what. Here's tramp. Marry him, tha's what!"

Into the face of October Jones came a look that defied the description of those who witnessed the scene.

"I'll marry him!"

Robin the tramp stared at her owlishly.

"He's drunk!" said a voice in the background, and there was a laugh. "Wouldn't drink, so we sat on him and poured it down."

"We poured it down, we poured it down!" roared the chorus, stamping time with their feet. "He wouldn't drink so we poured it down! Poured it down ..."

The voices straggled; one dropped out and then another. Sam was left in the position of soloist, and presently he stopped.

October was searching the face of the dazed tramp, eagerly, tensely. The thing of rags and tatters shook his head in helpless protest. His gaze wandered from the girl to the shaded lamp: it was smoking blackly. The lamp interested him. He raised a solemn finger as though in reproof. And then his eyes came back to the girl.

"Fearfully sorry!" he muttered. "Curse that intaglio!"

It was as though he of all the gaping company had some dim understanding of her humiliation. He waggled his head, frowned terribly. She saw the struggle between the will of him and the drug that deadened his senses. He was trying to throw off the black cloth that blinded him—and failed. As to this strange talk of intaglios. She had no room in her mind for that.

"I will marry him!"

Elmer's lip was working terribly fast. Mr. Wasser was weeping weakly.

"You can't. You marry Sam—"

"That weakling!"

Sam sniggered at this, made to stride up to her, tripped over the carpet, and floundered on his hands and knees, tried to rise and fell again.

"You'll have to marry me off to-night—I'll take the tramp!"

Mrs. Elmer wrung her hands.

"You don't know what you're saying," she squeaked. "You can't do it, October!"

"Can't I?" The girl's eyes were on the Reverend Stevens. "One man is like another in the eyes of God, isn't he?"

She turned to Robin; he was regarding her with wide eyes.

"Such things cannot be," he said solemnly.

"What is your name?"

"Robin—Robin Leslie."

"Robin Leslie—that will do."

She took his grimy hand in hers. She was at that moment a being exalted; her eyes were blazing.

The Reverend Stevens fiddled with his prayer book, looked over his glasses at Mr. Elmer. Andrew was biting his nails, one eye on the clock, one on the limp figure that sprawled on the floor. Sam had gone to sleep.

"You do as you like," his voice quavered. "You're mad, October—plumb starin' mad..."

She still held the hand in hers.

"My name is October Jones—his is Robin Leslie—marry us."

The Reverend Stevens opened the book and stumbled through the words. From the carpet came the drum beat of Sam's snores.

"Ring?"

She stooped and searched the waistcoat pocket of the slumbering youth.

"Here it is."

So in the sight of God and His congregation she was made Mrs. Robin Leslie.

Mrs. Elmer, hand at mouth, watched her like a woman in a trance. Andrew talked furiously, but no sound came. As for Robin the tramp—

"Sorry!" he said once.

The crowd at the end of the room gasped as they came toward the door.

"Where you goin'?" asked Wasser hoarsely.

"With my husband."

They disappeared into the black night, and for a long time nobody spoke or moved. Then with a scream Mrs. Elmer flew to the door.

"October! October!"

There was no answer but the uneasy rustling of the leaves and the deep growl of distant thunder.

AS OCTOBER crossed the porch she heard the roll of thunder. Hanging over the handrail was the old coat she used as a carpet when the shade of the apple trees enticed her out of doors. She gathered it mechanically.

Robin was walking ahead of her. She saw the nearly white sleeve of his tattered shirt and, quickening her pace, overtook him.

"Where's that?" He pointed with waggling finger.

"That is the road—it leads to the fork."

He rubbed his forehead.

"Another way—path over fields?"

She considered.

"You don't wish to go through the town? It doesn't worry me at all."

"Worries me. I'm rather tight. The young devils! I wasn't prepared for them."

He stood uncertainly. Ahead were the gate and the road. Behind she heard somebody scream her name.

"This way."

She caught him by the sleeveless coat and dragged him between the elderberry bushes along a track scarcely visible in daylight. He stumbled once and apologized. She saw that he really was "tight"—intoxicated. The path brought them to grass and trees and an occasional view between the apple trees of a far-away yellow light. Presently they were clear of the orchard and traversing a rough stretch of field where Mr. Elmer grazed his cows. There was a big barn here, its bulk showing blackly against the sky; beyond was rough going, a pool where the cows drank and sheer waste land where nothing grazed or grew.

"Storm somewhere," said Robin. October had seen the lightning. "Following the valley of the St. Lawrence."

She stopped suddenly.

"What are you—what nationality? You're not American?"

"Bri'sh." Only now and again was his voice slurred.

She drew a long breath.

"Then I'm—British!"

She could not see his face; she had to suppose his dullness from his tone and attitude.

"Are you? Fine."

Her lips were tight pressed.

"I'm American—nothing will ever make me anything but American."

"Oh." He was trying to think. "You said you were Bri'sh just now—I hate people who can't make up their minds. Where are we going?"

"Where are we going? Where do you want to go?"

"Prescott."

She gasped.

"In Canada?"

He nodded; she had to guess this.

"Where does this bring us—right here, I mean?"

She told him there was a road ahead of them. It joined the main road west of Littleburg.

"Is there a little wood road goes through it?" he asked eagerly. And, surprised, she said that there was. They had reached the snake fence which marked the boundary of Four Beeches Farm when he hissed:

"Don't speak—kneel!"

She obeyed and heard somebody talking, and after a while saw the flare of a match.

"Flat down in this dip!" He set her an example and sprawled face downward on the moist grass. She fell beside him, her heart racing.

There was no cause for that wild excitement, she told herself, and yet she knew that there was an enormous, a vital reason. There was danger; a vague sense of peril lifted the hairs of her neck. She found herself glaring toward the road and hating the men who were walking in so leisurely a fashion toward them. Nearer and nearer. One stopped to strike another match. They were less than six yards from where the two were lying. She glimpsed a fat, broad face and had a flash of a red beard.

"You certainly put your name in lights, Lenny!" said Red Beard disparagingly. "We Ought to have come out with a band."

"Huh!" grunted the other. "What's that matter? He's not here, not'n miles."

"I saw him, I tell you. With a bunch of kids, all loaded. If you'd been around I'd have got him."

"Had to go up to the depot... that fly cop ..."

The voices grew indistinct; they became a murmur. Came a growl and rumble of thunder, and when it died away there was silence.

"Are they looking for you?" she whispered.

"Yes."

His voice was steady; he seemed suddenly sobered. As he rose, the western skies throbbed palely with lightning, and she saw the glint of something in his hand. Sober his head might be to meet what trouble was present, but he staggered as he walked.

"Don't stub your toe against the fence," he whispered. "Wood sounds carry. Is there a gate?"

"Farther along."

"Down!"

He had seen the faint speck of a cigar end; the men were coming back. This time the hiding pair had an advantage. A small ridge of earth ran parallel with the fence; behind this they were safely screened.

The two strollers stopped opposite to them. Apparently one seated himself on the fence; they listened, heard the scrape of his shoes on the rail.

"... back in the wood on the other side of the town, I bet. Ought to have combed that wood, Lenny. If I hadn't been a bonehead I'd 'a' got him at Schenectady."

A silence.

"He got that gun," said another voice.

"Like hell he did! That's newspaper lyin'. Fellers don't smash a bank to get a gun. Well, maybe it wasn't a bank but I reckon the bookkeeper's office at a plant is as good as a bank."

"Newspaper said—"

"Newspaper!" He added an appeal to his Deity.

Another long silence. The scent of a good cigar was wafted toward and over the hillock.

"Say, what's Gussie got on him?"

Red Beard (she could identify the two voices now) laughed shortly.

"Listen, Lenny, suppose we get this bird—what'll we have on Gussie? Oh, nothin'! Come on."

The sound of their footsteps receded. Raising his head, Robin took an observation.

"Gussie!" he murmured, "That's jolly good!"

Ten minutes passed before he got up and helped her to rise.

"Where is the gate?"

She walked a little ahead of him. He must have seen that the coat she carried was trailing; he took it from her without a word.

The gate was found; it was half open. They went through the road, which was uneven but infinitely easier to walk upon than the field. The grass had been heavy with dew—she felt the front of her dress was soaked.

"There's a house up in these woods—haunted. Not afraid?"

"The Swede's house," she said, remembering.

"That's it. Hanged himself, didn't he? Hobos never go there—rather sleep in the rain. They think it is unlucky. Terribly superstitious people, tramps. Am I walking too fast?"

"No." A hundred yards farther on: "You're not drunk now."

He turned his head sideways to her.

"Yes, I am, horribly! I keep thinking you're someone else. And my legs are all crazy. I didn't sleep last night. I jumped a ride on a freight train night before that, but one of the train hands found me and booted me off. I could sleep standing to-night. But I'm drunk all right."

The road began to ascend. She had so often walked this way that she could have gone forward blindfolded. Larches appeared on either hand and the road became a track. Now they were in a great darkness; the far-off lightning was helpful, the sky reflection came down to them through the tree tops.

"It is to the left somewhere; there are two steps up the bank."

They walked more slowly now, searching for the path to the Swede's house. A flicker of light in the sky, and they saw the steps—two roughhewn slabs of sandstone, worn by the feet of the suicide.

At the head of the steps he stopped, swaying from side to side. She thought the climb had made him dizzy, but when she put out her hand to steady him he disengaged himself gently. Then she too saw the red gleam of a fire. It was somewhere beyond the spot where they had turned from the track.

"Shtay here," he said huskily, and went down the steps.

Moving stealthily forward, the man stalked the fire foot by foot. No sound came back to the waiting girl. Nearer and nearer he went, slipping from tree to tree until he reached a place where he could see the campers.

There were two: one immensely tall and one who seemed by comparison a dwarf, and though later he proved to be scarcely shorter than the average man, Robin thought of him and spoke of him as "the little man."

Tramps both, grimy of face, their raiment was such that the sack about the big fellow's shoulders seemed surprisingly smart. He had a low receding forehead, a gross button of a nose, and a huge hairy chin; eyes as small, as dark, and as close set as a monkey's. His companion was a very old man. His rags were indescribably foul, his face had not known soap and water in weeks. White-bearded, bald, he sat, staring into the fire.

"Come right along, bo," growled the big man.

He had seen the stalker, though apparently he had not lifted his eyes from the bread he was carving.

Tramp Robin lurched forward. His head was surprisingly clear, though nausea almost overcame him.

"Howdy," growled the big man. "Set you down. Did that yard dick chase you? The—! He ditched me, but this old plug flew the coop."

Robin gathered they had been thrown off a train by a railroad detective.

"An' a slow freight!" He invoked his God.

"Goin' up to Ogdens?" the little old man asked eagerly. "We're glommin' the Limited to-night—"

"Ain't no Limited, you old fool [he did not say "fool"], I'm tellin' yer. How's this town for handouts, Joe? Listen, this dam' road's worse than hell."

"I haven't tried it yet."

The big man opened his eyes. The accent, if not new, was strange.

"British! That's funny." And then, looking closely at the stranger: "Ye're stewed! Hi, Baldy, this bird's stewed!"

A new interest came to the little eyes.

"Set down, Joe—guess you're the gay cat!"

"Pardon me"—the little old man's voice took on a sudden refinement—"you are acquainted with Ogdensburg? You will be interested to learn that—"

"Shut up!"

The big tramp's lips curled up in a snarl, his hand swung back, and the little man shrank to the earth, a grimace of terror on his grotesque face.

"Always seein' spooks; got himself nearly pinched by a station bull at Troy—Troy, can you beat it! Him yowlin' round the railway yards about app'ritions! Ju-liah!"

Baldy was shivering like a wet dog, but at that word some courage returned to him.

"Not that word, O! Listen. She treated me badly—she was mean. O, but I'd rather you didn't!"

"Ju-liah!" roared the big man mockingly.

His great hand shot out, gripped the little face of his companion, and shook it savagely. Robin looked, said nothing till the brute threw the old man from him and grinned up at the eyewitness.

"Set you down. What's hurtin' you, Joe? G'wan, set down. You comin' along? There's good batterin' in Ogdens. Say, I knew 'n Englishman—set down!" The last two words were shouted.

"Standing up," said Robin calmly. "And walking!"

"'Fraid I'll roll you? Gawd a'mighty, you ain't got three cents!"

"Maybe not; still, I'm walking."

He turned and walked away. Out of the corner of his eyes he saw the man reach for a stone, and spun round.

"I'm packing a gat," he said significantly.

He saw that the man believed him, for he forced a laugh.

"You'd get life for that," he said sarcastically. "An' a sappin'! It's a fool thing to carry—a gun."

He got up and trod on the fire, collected the remains of the feast, and rolled them up into an old newspaper.

"Come on, Baldy—this gay cat reckons I'm goin' to roll him! You catchin' that freight?"

Robin shook his head.

"Huh! Never thought you was. Bet you've never decked a car in your life. Come on—you!"

Baldy got up slowly, collected his own belongings, and slouched in the trail of his master. Soon they were out of sight, and Robin, stamping the last red ember to death, went back to the girl.

"Who were they?" she asked. She had seen them pass..

"Some fellers—tramps. Where's this house?"

She pointed—at least he thought she was pointing. The storm was coming nearer; the heaven lit up in a quivering succession of flashes. He saw a low-roofed shack, a blind that hung by one hinge, a pitiful little portico drooping on one pillar.

"Home!" said Robin magnificently.

The door was fast, but a window gave him entrance. After a while she heard his footfall in the passage and the squeaking of a latch. It took a perceptible time to open the door, and then it only yielded far enough to admit her.

"Hinges gone," he said briefly.

He pushed the door tight and then, striking a match, lit a piece of candle which he took from a pocket on the inside of his coat. The passage was inches deep in debris. Dead leaves had found their way here, and scraps of discoloured rags showed under the accumulations of dust. Across the passage ran a beam of unpainted pine, and screwed into the wood was a large hook. She saw this. The forgotten Swede, whose sole memorial this tumbledown house was, had hanged himself.

"Ugh!"

He looked at her gravely.

"Not scared?" His eyes went up to the hook. "That wasn't it. Used to hang hams there. He did it in a wood—on a tree somewhere. So they say. Lost his wife and went mad—before you were born. So they say."

"So who say?" a little impatiently.

He jerked his head vaguely toward Littleburg; in reality he was indicating a scattered community.

"Tramps swap these yarns. I didn't understand them all—they have a language of their own. Hold the light, will you, please?"

October took the candle from his hand and he lurched into a room that opened from the passage. He returned very soon, carrying a dusty and ragged blanket.

"There's an iron bed—the spring mattress feels good to me. Rusty, I think, but springy. We'd better chance a light."

The bed was a very dismal-looking affair, but, as he said, the spring bottom was intact. He shook out the blanket and folded it pillow fashion.

"Warmish," he said sleepily, "but you'd better pull your coat over you."

She sat on the bed. Looked at him. He might have been good-looking once. The bristly face, the bruised eye, the puffy redness on one cheek... October shook her head.

"What is the matter with your face?" she asked.

He was surprised by the question.

"Generally or particularly?" he asked, and touched his cheek. "This? Poison ivy. Those old Inquisitors missed something. Go to sleep."

She kicked off her shoes and lay down, pulling her coat over her. The mattress was largely soft, but it was made up of little steel links and her dress was thin. She would be like a tattooed lady in the morning. He had seated himself in a corner of the room and blown out the candle. Presently she heard his deep breathing; once he snored.

Through the unshaded window she could see the sky lit red and blue at irregular intervals. The house shook and shivered with every crash of thunder. And then the rain came down. It rattled and drummed on the iron roof, beat against the broken windowpane.

"Seep, peep, peep!"

The roof was leaking somewhere; the drip and drop of water sounded close at hand. Between thunder rolls she heard the breathing of Robin. She was dozing when he spoke in his sleep.

"Silly fool," he muttered, "silly fool!"

Whether he was talking of himself, or of somebody who belonged to the life that was veiled, or of her, she could only speculate upon.

She fell into a dreamless sleep. She woke slowly with the consciousness that somebody was holding her hand; a bristly cheek was near to hers. She opened her lips to scream and a firm hand closed her mouth.

THE wedding party had melted down to four. The Reverend Stevens had gone on the tail of guests—wanted and unwanted. His responsibility had been a heavy one, he both felt and said. And yet—might he not to-morrow find himself a Controversial Subject, with legions for him as well as sour battalions against? Might he not anticipate pictures of himself across two or even three columns, with captions beneath?

He had been human before he had become evangelical; it was difficult to be wholly inhuman. Brethren of his cloth, who cared less for captions and controversy, would arise in their wrath and denounce him. Mothers of marriageable daughters, fearing the imitative qualities of youth, would condemn him unreservedly. The broad-minded, who invariably champion the less decent protagonist of all controversies, would say that there was something to be said for him.

He stole away, shaking his head. When the reporters came to him in the morning he would have twelve photographs of himself spread on the parlour table for their inspection. He preferred the one taken at Potsdam in the early days of his ministry. It was in profile, and he had rather a striking profile. He thought about October as he hurried homeward, but imagination was not his strong point. She had committed a folly in her petulance; she would probably have run away from her tramp husband before now. He honestly expected to learn in the morning that she had returned to Four Beeches Farm, was there already, he supposed, as he disrobed for the night.

Andy Elmer sat rigidly by the table that served as an altar. Mrs. Elmer was weeping, more in anger than in sorrow, in her rocker. Mr. Lee Wasser sat on the sofa, his arm about a dazed and sickly Sam.

"Nobody can blame me," said Mr. Elmer disjointedly. "The crazy little cat! High school an' college ideas..."

Mr. Wasser glared at him malignantly.

"Look fine in the newspapers, hey? My boy thrown over for a dirty old hobo, hey?"

He had said this so often in the last ten minutes that Andrew Elmer scarcely heard him.

"She's got no clothes—nothin'!" wailed Mrs. Elmer. "Not even the blue. What folks'll say..."

Andy's upper lip went up and down furiously.

"She done it for spite—" he began.

The hired man appeared in the doorway.

"There's a feller wants to see you, Mr. Elmer. English, I guess. Didn't understand half he was say-in'."

Mr. Elmer blinked at him. The Grand Cham of China could not have made a more inopportune appearance at that hour and in those circumstances than an unintelligible Englishman. He glanced at his wife. Mrs. Elmer dabbed her eyes and made an awkward exit. Sam was not in a state that permitted any kind of exit. There was a challenge in Lee Wasser's eye; he, at any rate, had nothing to be ashamed of. Already Sam was a Victim of Dire Machinations.

He had been drugged by this infamous man with the black eye and the swollen face, or hypnotized, or treated with something that had no fumes of whisky in it. And, thus incapacitated, had been bereft of his wife. Sam drooped more limply; uttered discordant sounds. Mr. Elmer was alarmed.

"Can't you get him into the kitchen, Lee?" he almost pleaded. "Mrs. Elmer's awful particular—"

"He's singing." Mr. Wasser's tone was ferocious. "There's a whole lot back of this business. If it costs me a thousand dollars I'm going to get right down to the bottom of it!"

The hired man ran his fingers between the hateful stiff collar of ceremony and his scrawny neck, a gesture of impatience. There was a little group of excited people on the back porch all talking at once. He had his own view to expose and felt that he was missing something.

"Say, Mr. Elmer, he said he wanted to see you."

Behind him there appeared a tall figure in a long dust coat. He wore an eyeglass and bright brown gauntlets. Mr. Elmer saw that over enamelled shoes were fawn-coloured spats.

"Sorry to bother you—er—"

He was a good-looking fellow with a waxlike complexion, a small brown silky moustache, and a permanent smile. At least, it seemed permanent. His voice was soft and rather musical.

"I heard a rumpus outside but couldn't make head or tail of what these—er—people were saying. Something about a tramp. I hope you will forgive me—er—butting in."

He said "butting in" a little self-consciously, as an Englishman speaks a foreign language. He had (his manner said) no right to flounder in strange colloquialisms, but desired to make himself understood.

"Uh huh. That's right. There was a tramp up here boozed. That's so."

Mr. Elmer was called upon without notice to put into words his version of the happening. And it must be put into words sooner or later. In two or three days he would be facing a Farmers' Convention—he shuddered at the thought.

"Well, say ..."

The presence of Mr. Lee Wasser and the condition of the heir to the Wasser fortune largely determined the colour and shape of his narrative. That the monocled Englishman was a curious intruder, to be asked what'n thunder the affair had to do with him, did not occur to Mr. Elmer. The stranger was The World; he represented in his person millions of people sitting at breakfast reading their morning newspapers and saying: "That's a queer affair over in Littleburg—tramp married a college girl."

Moreover, he was the forerunner of an army of reporters and photographers.

"My niece, well, her mother was a sort of sister-in-law ... this young lady ... October Jones was her name.... She got some mighty queer notions about—everything."

"Extraordinary!" murmured the stranger. It was merely a polite or a sardonic interjection, but it gave Mr. Elmer a guiding line.

"Extr'ordin'ry. You've said it! Well, this young lady was gettin' married. Everything fixed. Reverend Stevens—well, everything!" A wave of his hand indicated certain festive preparations; the Englishman in the dust coat examined the flowers earnestly.

"And then, this tramp sort of—well, he came. Right there where you're standing."

"An' Sam was doped. No doubt about that." Mr. Wasser entered the conversation loudly. "This bum fixed him that way. Maybe gave him somep'n' to smell. He's unconscious now."

Andrew nodded.

"That's about it," he said, "and October was crazy. She said 'I'll marry him.' I just couldn't speak. I was standin' here, or maybe there"—he indicated the alternative spots with meticulous exactness. "I just couldn't so much as holler."

"Doped," murmured Mr. Wasser helpfully.

Andrew considered this explanation and regretfully decided upon its rejection.

"Paralyzed," he substituted. "Couldn't believe I was awake."

The stranger was staring at him. He was as near to being without a smile as ever Mr. Elmer saw him.

"Married?" he said sharply. "Who was married?"

Mr. Elmer groaned at the man's stupidity.

"October—her crazy idea ... she took the ring out of poor Sam's pocket. Just bent down an' took the ring. 'Here it is,' she says. 'What's your name?' An' this hobo says—what did he say, Lee?"

Mr. Wasser had forgotten. His angry gesture told the Englishman how very unimportant was the question of a tramp's name.

"I don't quite understand. This girl—October, is that her name-?—wanted to marry a tramp?"

"He was drunk," said Mr. Wasser, in a tone that suggested a reason for October's strange behaviour.

"She wanted—and she did," said Mr. Elmer.

The stranger's mouth opened; his eyeglass dropped.

"Married! Not really married?"

Messieurs Elmer and Wasser nodded. Sam's nod was involuntary.

"Good God!"

The heart of Andrew Elmer sank. If this simple statement produced such an effect upon a stranger, and obviously an unemotional stranger, what would follow the general publication of the news?

"I want to say right here that October is peculiar. She's crazy, that's all. She'd jump into a well, yes, sir. She said so I 'You touch me,' she says, 'an' I'll jump right in.' Yes, sir—"

"To-night? Did she jump into the well?"

There was unmistakable hope in the stranger's voice.

"No, sir: I'm talkin' about last fall—"

"She married this tramp—actually married him?" And when they nodded gravely: "My God!" Then, before Mr. Elmer could speak: "Where is he?"

"October—" began Mr. Elmer.

"Never mind about October." He was smiling, but wickedly. "I suppose she is here. Where did the tramp go?"

Lee Wasser pointed dramatically to the door.

"They went out—there! Both of 'um."

The man in the dust coat turned his head.

"Both of 'um!" he repeated absently and with sudden animation. "How long since? Which way did they go?"

Mr. Elmer lugged out his big watch.

"About half an hour ago," he said.

The watch had no value at all to indicate the passage of time. This event belonged to eternity; the dial should have been divided into aeons.

"About half an hour—they went out there."

The door, then, was a starting point, the black night a destination. The stranger walked from the house. At the gate four men were talking.

"Say, listen, this bird was loaded. Didn't know what he was doin'. Sam an' Ed got him up in the wood an' Pete back-heeled him and got him on the floor. 'You son of a gun,' says Ed, 'you gotta drink.'"

Dust Coat went past them and they stopped discussing the great happening to speculate upon his identity.

"English. He's got a big machine. Joe Prideaux at the garage reckons it's worth ten thousand dollars an' more."

The machine was waiting a little way along the road and Mr. Alan Loamer leaped into the driver's seat and drove at an increasing speed toward Littleburg. He came through the town more cautiously because he could not afford to be held up by the unimaginative police. Clear of the power plant, he let the big car roar and switched on his powerful headlamps. He was watching the road carefully. Presently he saw somebody jump a fence from the road and brought his machine to a stop.

"Byrne!" he called.

A shape came but of the gloom and then another.

"Have you seen him?"

"No. Lenny and me's been hanging around here. He's got to come this way unless he works back. Lenny reckoned he might be in the woods the other side of town."

The man at the wheel said something under his breath that Red Beard could not hear.

"I wanted to locate you," he said. "Stay here: I'll go back and make inquiries. He has a girl with him."

"You don't say!" Red Beard was frankly astonished.

"Yes—that may make things difficult for you." Mr. Loamer was fretful. His audience did not know that inside him and behind his calmness was a boiling, bubbling rage. "Is there a side road here? I want to turn my car." He pronounced the word strangely.

"Wants to turn his 'caw,' does he?" said Red Beard, watching the manoeuvres of the big machine from a distance. "Gussie's rattled all right, Lenny."

"What's the idea—this girl? Never heard anything about her," demanded the fat man.

The machine had turned by now and was flying back; it boomed- past them on its way to Littleburg.

"You heard him; did he tell me anything? A girl. First I've heard of a girl. That bird's nutty. I keep tellin' you, Lenny."

Mr. Loamer came back to Littleburg to find it alive. He saw groups at odd corners, and once he passed two men carrying shotguns and addressing each other noisily. On the corner of Main and Union streets he saw a policeman.

The policeman knew nothing except that there had been some sort of trouble up at Mr. Elmer's farm. The chief was dealing with the consequence, whatever it was. He asked Mr. Loamer if he had seen two men, one with a red beard and one rather fat and short. Mr. Loamer said that he had not.

"They're not in town, I guess," said the policeman, and expressed the view that the storm would just miss Littleburg.

It was an hour after midnight when the watcher on the road saw the unmistakable headlamps of the big car and woke his companion, who was sleeping with his back against the rail of the fence.

"There is a search party looking for these people," said Mr. Loamer. "They are going through the woods on the far side of the town, but somebody suggested that he would make for the Swede's house. They say it is haunted. Where is it?"

"Swede's house—know that, Lenny?"

The sleepy-eyed Lenny thought that he had heard of such a place, but he had never seen it. Evidently he had a nodding acquaintance with the district.

"It's somewhere on the high ground back of Elmer's place," he said. "Never been there, but the woods are not big."

He indicated the route they would follow. Mr. Loamer said he would return to the town for the latest news and would join them.

"This time—get him!" he said emphatically. "The girl?" He smoothed his moustache with his gloved hand. "I don't know what to do about her." He was silent for a very long time. Evidently the girl was the subject of his cogitation, for when he spoke he said: "She doesn't matter, really."

As he stepped into the driver's seat he remarked casually:

"A policeman asked me if I had seen you fellows, and of course I told him that I hadn't."

"That was certainly kind of you." Red beard was good-humouredly sarcastic.

When the car was out of sight he clapped his companion on the shoulder.

"Let's go," he said. "That old Swede's house is haunted, eh? Maybe we can deal it a new spook."

OCTOBER was very wide awake now. She did not struggle, but gripped at the hand which covered her mouth, conserving all her strength to pry loose this suffocating pad of muscle and bone.

"Don't make a sound!" he was breathing. "Terribly scared you'd shout... somebody prowling outside the house."

She nodded. The hand was drawn away, the bristly face was removed.

"Sorry!" he whispered. "Can you get off the bed without raising a riot? Wait!"

His two hands went under her; she felt herself raised slowly.

"Creak—squeak!" went the rusty springs as they relaxed. He canted her gently, feet to floor, so that she stood with her back to the wall in which the window was set.

"Don't move!"

The storm had passed; she thought she detected the ghostly light of dawn in the room. Silence and then, outside, the cracking of a twig.

Robin the tramp crouched under the window. She could only see a splodge of something a little blacker than the blackness of the room.

The window darkened; hands were fumbling with the latch. She heard the low murmur of a querulous voice. Suddenly a brilliant circle of light appeared on the opposite wall: the man outside was searching the room with an electric lamp. The circle moved left and right, up and down; focussed on the end of the rusty bed and paused there undecidedly. She saw Robin clearly now, huddled under the window; he was gripping a steel rod that, attached to the window, had once regulated its opening. She had wondered why the man outside had failed to find a way in. The light went.

"Get to the door, along the passage to the right. Take your shoes but don't put them on!"

She nodded agreement to the sibilant instructions, gathered her shoes, and tiptoed along the passage until a door barred further progress. Here she waited. Presently she heard him coming toward her.

"Is it open?" he whispered, and went past her.

The passage was so narrow that she felt the brush of his shirt sleeve on her face. The door was unlocked but noisy. The enemy was at the front door by now, rattling the handle. Robin the tramp waited until the sound came again and then, putting his shoulder to the obstruction, pushed. With a grind and a jar it opened. Reaching back, he caught her by the arm and pulled her through. They were in a kitchen which smelled of earth and damp. A second door was here. He felt for it, groping along wet walls. Overhead the roof had partly vanished.

A thudding sound shook the little house. Another. Robin tugged at the door and it opened with a groan; the scent of wet leaves and balsam came to October's grateful nostrils.

"Got your coat?" His lips were close to her ear. She did not mind the bristly cheek now. "Good! Follow me—you'll get your feet wet but that won't kill you. Hold my sleeve. When I stoop, do the same."

He stepped out into the tangle of what had once been a garden. Noiselessly he moved toward the encircling wood, she creeping behind him. Her stockings were soaked; once she trod on a thorn and needed all her self-control to repress a cry. As it was she made some sort of sound, for he half turned. They were circling toward the town road; if it had been light they could not have seen the Swede's shack when he stopped.

"Put on your shoes—I expect your feet are wet."

She held onto his arm with one hand and pulled on her shoes one by one with the other. Her feet were sodden, and the soles of her silk stockings in rags. But she was glad to have leather between foot and earth.

"No hurry. They will take some time exploring the hut," he said, still whispering. "And the trees will spoil Lenny's style—he likes the great open spaces where men are men!"