a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Five Knots Author: Fred M White * A Project Gutenberg Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1100051h.html Language: English Date first posted: February 2011 Date most recently updated: February 2011 This eBook was produced by: Maurie Mulcahy. HTML version by Roy Glashan. Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

| I - No Bigger Than A Man's

Hand II - A Little Bit Of String III - The Registered Letter IV - In The Wood V - Under The Trees VI - The Lighted Lamp VII - The Shadow On The Wall VIII - The Blue Terror IX - Behind Locked Doors X - "Mr. Wil—" XI - On The Way Home XII - In The Ring XIII - An Old Acquaintance XIV - Russell Explains XV - The Real Thing XVI - The Yellow Hand XVII - The Diamond Moth XVIII - A Tangled Clue XIX - Fencing XX - The Waterfall XXI - A Double Foe XXII - From East To West XXIII - An Expected Trouble |

XXIV - The Long Dark Hour XXV - The Diamond Moth Again XXVI - Dr. Jansen XXVII - No Foe Of Hers XXVIII - Beyond Surgery XXIX - A Message XXX - A Slight Misunderstanding XXXI - A Question Of Honour XXXII - No Place Like Home XXXIII - By Whose Hand? XXXIV - A Human Derelict XXXV - Jansen At Home XXXVI - Leading The Way XXXVII - A Respite XXXVIII - A Sinking Ship XXXIX - The Vaults Beneath XL - Towards The Light XLI - Vanished! XLII - Treasure Trove XLIII - In Hot Pursuit XLIV - The Meaning Of It XLV - Aladdin's Cave XLVI - Uzali's Way Out |

Frontispiece

Something like a shadow seemed to flicker across the dim hall and then the strange visitant was lost to view. But was it substantial, real and tangible, or only the creature of imagination? For at half-past four on a December afternoon before the lamps are lighted one might easily be deceived, especially in an old place like Maldon Grange, the residence of Samuel Flower, the prosperous ship-owner. Some such thought as this flashed through Beatrice Galloway's mind and she laughed at her own fears. Doubtless it was all imagination. Still, she could not divest herself of the impression that a man had flitted quietly past her and concealed himself behind the banks of palms and ferns in the conservatory.

"How silly I am!" she murmured. "Of course there can be nobody there. But I should like—"

A footman entered and flashed up the score or so of lights in the big electrolier and Beatrice Galloway's fears vanished. Under such a dazzling blaze it was impossible to believe that she had seen anybody gliding towards the conservatory. Other lights were flashing up elsewhere and all the treasures which Mr. Flower had gathered at Maldon Grange were exposed to the glance of envy or admiration. Apparently nothing was lacking to make the grand house absolutely perfect. Not that Samuel Flower cared for works of art and beauty, except in so far as they advertised his wealth and financial standing. Nothing in the mansion had been bought on his own responsibility or judgement. He had gone with open cheque-book to a famous decorative artist and given him carte blanche to adorn the house. The work had been a labour of love on the part of the artist, so that, in the course of time, Maldon Grange had become a show-place and the subject of eulogistic notices in the local guide-books. Some there were who sneered at Samuel Flower, saying there was nothing that interested him except a ship, and that if this same ship were unseaworthy and likely to go to the bottom when heavily over-insured, then Flower admired this type of craft above all others. The reputation of the Flower Line was a bad one in the City and amongst seafaring men. People shook their heads when Flower's name was mentioned, but he was too big and too rich and too vindictive for folk to shout their suspicions on the housetops. For the rest of it Flower stuck grimly to his desk for five days in the week, spending the Saturday and Sunday at Maldon Grange, where his niece, Beatrice Galloway, kept house for him.

Beatrice loved the place. She had watched it grow from a bare, brown shell to a bewitching dream of artistic beauty. Perhaps in all the vast establishment she liked the conservatory best. It was a modest name to give the superb winter garden which led out of the great hall. The latter structure had been the idea of the artist, and under his designs a dome-like fabric had arisen, rich, with stained glass and marble and filled now with the choicest tropical flowers, the orchids alone being worth a fortune. From the far end a covered terrace communicated with the rose garden, which even at this time of year was so sheltered that a few delicate blooms yet remained. The orchids were Beatrice's special care and delight and for the most part she tended them herself. She had quite forgotten her transient alarm. Her mind was full of her flowers to the exclusion of everything else. She stood amongst a luxuriant tangle of blooms, red and gold and purple and white hanging in dainty sprays like clouds of brilliant moths.

By and by Beatrice threw herself down into a seat to contemplate the beauty of the scene. The air was warm and languid as befitted those gorgeous flowers, and she felt half disposed to sleep as she lay in her comfortable chair. There would be plenty to do presently, for Flower was entertaining a large dinner party, and afterward, there was to be a reception of the leading people in the neighbourhood. Gradually the warmth of the place stole over her drowsy sense and for a few minutes she lost consciousness.

She awoke with a start and uneasy feeling of impending evil which she could not shake off. It was a sensation the like of which she had never experienced before, and wholly foreign to her healthy nature. But nothing was to be seen or heard. The atmosphere was saturated with fragrance and delicate blossoms fluttered in the lights like resplendent humming-birds. As she cast a glance around, her attention became riveted upon something so startling, so utterly unexpected, that her heart seemed to stand still.

The door leading on to the terrace was locked, as she knew. It was a half-glass door, the upper part being formed of stained mosaics, leaded after the fashion of a cathedral window. And now one of the small panes over the latch had been forced in, and a hand, thrust through the opening, was fumbling for the catch.

The incident was sinister enough, but it did not end the mystery. The hand and the arm were bare, and Beatrice saw they were lean and lanky and brown, like the leg of a skinny fowl. From the long fingers with blackened nails depended a loop of string which the intruder was endeavouring to drop over the catch. Unnerved as Beatrice was, she did not lose her self-possession altogether. While she gazed in fascinated horror at that strange yellow claw, it flashed into her mind that the hand could not belong to a white man. Then, half unconsciously, she broke into a scream and the fingers were withdrawn. The string fell to the ground, where it lay unheeded.

Beatrice's cry for help rang out through the house, and a moment later hurried steps were heard coming towards the conservatory. It was Samuel Flower himself who burst into the room demanding to know what was amiss. At the sight of his stalwart frame and the strong grim face Beatrice's fears abated.

"What is the matter?" he asked.

"The hand," Beatrice gasped. "A man's hand came through that hole in the glass door. He was trying to pass a loop of string over the latch. The light was falling fully on the door, and I saw the hand distinctly."

"Some rascally tramp, I suppose," Flower growled.

"I don't think so," Beatrice said. "I am sure the man, whoever he was, was not an Englishman. The hand might have been that of a Hindoo or Chinaman, for it was yellow and shrivelled like a monkey's paw."

Something like an oath crossed Flower's lips. His set face altered swiftly. Though alarmed and terrified, Beatrice did not fail to note the look of what was almost fear in the eyes of her uncle.

"What is the matter?" she asked. "Have I said or done anything wrong?"

But Flower was waiting to hear no more. He dashed across the floor and threw the door open. Beatrice could hear his footsteps as he raced down the terrace. Then she seemed to hear voices in angry altercation, and presently there was a sound of breaking glass and the fall of a heavy body. It required all Beatrice's courage to enable her to go to the rescue, but she did not hesitate. She ran swiftly down the corridor, when, to her profound relief, she saw Flower coming back.

"Did you see him?" she exclaimed.

"I saw nothing," Flower panted. He spoke jerkily, as if he had just been undergoing a physical struggle. "I am certain no one was there. I slipped on the pavement, and crashed into one of those glass screens of yours. I think I have cut my hand badly. Look!"

As coolly as if nothing had happened Flower held up his right hand from which the blood was dripping freely. It was a nasty gash, as Beatrice could tell at a glance.

"I am so sorry." she murmured. "Uncle, this must be attended to at once. There is danger in such a cut. I will send one of the servants into Oldborough."

"Perhaps it will be as well," Flower muttered. "I shall have to get this thing seen to before our friends turn up. Tell them to fetch the first doctor they can find."

Without another word Beatrice hurried away, leaving Flower alone. He crossed to the outer door and locked it. Then he threw himself down on the seat which Beatrice had occupied a few minutes before, and the same grey pallor, the same queer dilation of his keen grey eyes which Beatrice had noticed, returned. His strong lips twitched and he shook with something that was not wholly physical pain.

"Pshaw!" he muttered. "I am losing my nerve. There are foreign tramps as well as English in this country."

Wilfrid Mercer's modest establishment was situated in High- street, Oldborough. A shining brass plate on the front door proclaimed him physician and surgeon, but as yet he had done little more than publish his name in the town. It had been rather a venture to settle in a conservative old place like Oldborough, where, by dint of struggling and scraping, he had managed to buy a small practice. By the time this was done and his house furnished, he would have been hard put to it to lay his hands on fifty pounds. As so frequently happens, the value of the practice had been exaggerated: the man he had succeeded has not been particularly popular, and some of the older patients took the opportunity of going elsewhere.

It was not a pleasant prospect, as Mercer admitted, as he sat in his consulting-room that wintry afternoon. He began to be sorry that he had given up his occupation of ship's doctor. The work was hard and occasionally dangerous, but the pay had been regular and the chance of seeing the world alluring. But for his mother, who had come to keep house for him, perhaps Wilfrid Mercer would not have abandoned the sea. However, they had few friends and Mrs. Mercer was growing old and the change appeared to be prudent. Up to the present Wilfrid had kept most of his troubles to himself, and his mother little knew how desperately near the wind he was sailing in money matters. Unfortunately he had been obliged to borrow, and before long one of his repayments would be falling due. Sorely against his will he had gone to the money-lender, and he knew that he could expect no quarter if he failed to meet his obligations.

While he sat gazing idly into the growing darkness, watching the thin traffic trickle by, he heard the sound of a motor horn and a moment later a big Mercedes car stopped before his door. There was an imperative ring at the bell, which Wilfrid answered in person.

"I believe you are Dr. Mercer," the driver said. "If so, I shall be glad if you will come at once to Maldon Grange. My master has met with an accident, and if you cannot come immediately I must find somebody else."

"I believe I can manage it," Wilfrid said with assumed indifference. He was wondering who the man's master was and where Maldon Grange must be. A stranger in the neighbourhood, there were many large houses of which he knew nothing. It would be well, however, to keep his ignorance to himself. "If you'll wait a moment I'll put a few things into my bag."

Few words were spoken as the car dashed along the road till the lodge gates at Maldon Grange were passed and the car pulled up in front of the house. A footman came to the door and relieved Wilfrid of his bag. He speedily found himself in a morning room where he waited till Beatrice Galloway came in. She advanced with a smile.

"It is very good of you to come so promptly," she said. "I did not quite catch your name."

"Surely you have not forgotten me?" Wilfrid said.

"Wilfrid—Dr. Mercer—" Beatrice exclaimed. "Fancy seeing you here. When we last met in London six months ago I thought you were going abroad. I have heard several times from our friend, Mrs. Hope, and as she never mentioned your name, I concluded you were out of England. And all this time you have been practising in Oldborough."

"Well, not quite that," Wilfrid smiled. "I have only been in Oldborough about a month or so. I had to settle down for my mother's sake. To meet you here is a great surprise. Are you staying in the house?"

"Didn't you know?" Beatrice asked. "Well perhaps you could not. You see, when I was staying with Mrs. Hope my uncle was abroad, and I don't think his name was ever mentioned. I suppose you have heard of Samuel Flower?"

Wilfrid started slightly. There were few men who knew more of Flower and his methods than the young doctor. He had been surgeon on board the notorious Guelder Rose on which there had been a mutiny resulting in the death of one of the ship's officers. The Guelder Rose was one of the Flower Line, and ugly stories were still whispered of the cause of that mutiny, and why Samuel Flower had never brought the ringleaders to justice. Wilfrid could have confirmed those stories and more. He could have told of men driven desperate by cruelty and want of food. He could have told of the part that he himself had played in the outbreak, and how he had brought himself within reach of the law. At one time he had been prepared to see the thing through. He had been eager to stand in the witness-box and tell his story. But by chance or design most of the malcontent crew had deserted at foreign ports, and had Samuel Flower chosen to be vindictive, Mercer might have found himself in a serious position. And now, here he was, under the roof of this designing scoundrel, and before him was the one girl in all the world whom he cared for, and she was nearly related to the man whom he most hated and feared and despised.

All these things flashed through his mind in a moment. He would have to go through with it now. He would have to meet Samuel Flower face to face and trust to luck. It was lucky he had never met the man whom he regarded as the author of his greatest misfortunes, and no doubt a busy man like Flower would have already forgotten the name of Mercer. It was a comfort, too, that Beatrice Galloway knew nothing of the antecedents of her uncle. Else she would not have been under his roof.

"It is all very strange," he murmured. "You can understand how taken aback I was when I met you just now."

"Not disappointed, I hope," Beatrice smiled.

"I don't think there is any occasion to ask that question," Wilfrid said meaningly. "But I must confess that I am disappointed in a sense. You see, I did not know you were the probable heiress of a rich man like Mr. Flower. I thought you were poor like myself, and I hoped that in time—well, I think you know what my hopes were."

It was a bold, almost audacious, thing to say in the circumstances, and Wilfrid trembled at his own temerity. But, saving a slight flush on the girl's checks, she showed no sign of disapproval or anger. There was something in her eyes which was not displeasing to Wilfrid.

"I am afraid we are wasting time," she said. "My uncle has had a fall and cut his hand badly with some glass. He is resting in the conservatory, and I had better take you to him."

Mercer followed obediently. Samuel Flower looked up with a curt nod, as Beatrice proceeded to explain. Apparently the name of Mercer conveyed nothing to him, for he held out his hand in his prompt, business-like fashion and demanded whether anything was seriously wrong.

"This comes of listening to a woman," Flower muttered. "My niece got it into her head that a tramp was trying to break into the house, and in searching for him I slipped and came to grief. Of course I found nobody, as I might have known at first."

"But, uncle," Beatrice protested. "I saw the man's hand through the glass. You can see for yourself where the pane has been removed, and there, lying on the floor, is the very piece of string he was using."

Beatrice pointed almost in triumph to the knotted string lying on the floor, but Flower shook his head impatiently and signified that the sooner Mercer went on with his treatment the better. As it happened, there was little the matter, and in a quarter of an hour the wounded hand was skilfully bandaged and showed only a few strips of plaster.

"You did that very neatly," Flower said in his ungracious way. "I suppose there are no tendons cut or anything of that kind? One hears of lockjaw following cut fingers. I suppose there's no risk of that?"

"For a strong man my uncle is terribly afraid of illness," Beatrice smiled. "I see he owes me a grudge for being the cause of his accident. And yet, indeed, I am certain that a man attempted to enter into the conservatory. Fortunately for me, I am in a position to prove it. You won't accuse me of imagining that there is a piece of string lying on the floor by the door. I will pick it up and convince you."

Beatrice raised the cord in her hand. It was about a foot in length, exceedingly fine and silky in texture, and containing at intervals five strangely complicated knots of most intricate pattern. With a smile of triumph on her face Beatrice handed the fragment to her uncle.

"There!" she cried. "See for yourself."

Flower made no reply. He held the string in his hand, gazing at it with eyes dark and dilated.

"Great heavens!" he exclaimed. The words seemed to be literally torn from him. "Is it possible—"

Beatrice and Wilfrid looked at Flower in astonishment. He did not seem to heed until his dull eyes met theirs and saw the question which neither dared to ask.

"A sharp, sudden pain," he gasped, "a pain in my head. I expect I have been working too hard. It has gone now. Perhaps it isn't worth taking any notice of. I am told that neuralgia sometimes is almost more than one can bear. So this is the piece of string the fellow was using, Beatrice? I am afraid I can't disbelieve you any longer. I am sure that there is no string like this in the house. In fact, I never saw anything like it before. What do you make of it, Dr. Mercer?"

Flower was speaking hurriedly. He had assumed an amiability foreign to his nature. He spoke like a man trying to undo a bad impression.

"It is curious, but I have seen something similar," Mercer said. "It was a piece of silken string of the same length, knotted exactly like this, and the incident happened in the Malay Archipelago. The ship on which I was doctor—"

"Oh, you've been a ship's doctor," Flower said swiftly.

Mercer bit his lip with vexation. The slip was an awkward one, but after that exclamation Flower showed no disposition to carry the query farther, and Wilfrid began to breathe more freely. He went on composedly enough.

"The ship was laid up for several weeks for repairs. Not caring to be idle I went up country on an exploring expedition, and very rough work it was. As you may be aware, the Malays are both treacherous and cruel, but so long as one treated them fairly, I had nothing to grumble about. I cured one or two of them from slight illnesses, and they were grateful. But there was one man there, his name does not matter, who was hated and feared by them all. I fancy he was an orchid collector. Anyhow, he had a retinue of servants armed with modern weapons, and he led the natives a terrible life. I purposely avoided him because I did not like him or his methods. One day I had a note from a servant asking me to come and see him as he was at the point of death. When I reached the man's quarters I found that all his staff had deserted him, taking everything they could lay hands on. The man lay on his bed dead, and with the most horrible expression of pain on his face I have ever seen. I could find no cause of death, I could find no trace of illness even. And by what mysterious means he was destroyed I have not the slightest notion. All I know is this—round his forehead and the back of his head was a tightly-twisted piece of silken string with five knots in it, which might be the very counterpart of the fragment you hold in your hand."

"And that is all you have to tell us?" Flower asked. He had recovered himself, except that his eyes were strangely dilated. "It seems a pity to leave a story in that interesting stage. Is there no sequel?"

"As far as I know, none," Wilfrid admitted. "Still, it is rather startling that I should come upon an echo from the past like this. But I am wasting your time, Mr. Flower. If you would like me to come and see you to-morrow—"

But Flower did not seem to be listening. Apparently he was debating some problem in his mind.

"No," he said in his quick, sharp way. "I should like you to come again this evening. We have some friends coming in after dinner, and if you don't mind dropping in informally in the character of a doctor and guest I shall be greatly obliged. Besides, it may do you good."

Wilfrid was not blind to the material side of the suggestion, but did not accept the situation too readily. He would look in about half-past nine. He had said nothing as to meeting Beatrice before. Neither did she allude to the topic, for which he was grateful. Beatrice led the way to the door.

"I am not to be disturbed, mind," Flower called out. "I am going into the library for a couple of hours, and I want you to send James Cotter to me, Beatrice. I can see no one till dinnertime."

Flower strode away to the library, where he transacted most of his business when out of town, and a few minutes later there entered a small, smiling figure in black, humble of face, and with a quick, nervous habit of rubbing his hands one over another as if he were washing them. This was James Cotter, Flower's confidant and secretary, and the one man in the world who was supposed to know everything of the inner life of the wealthy ship-owner.

"Come in, Cotter. Sit down and lock the door."

"You have some bad news, sir," Cotter said gravely.

"Bad news! That is a mild way of putting it. Come, my friend, you and I have been through some strange adventures together, and I daresay they are as fresh in your memory as as they are in mine. Do you recollect what happened seven years ago in Borneo?"

Cotter groaned. "For Heaven's sake, don't speak about it, but thank God that business is past, and done with. We shall never hear any more of them."

Flower paced thoughtfully up and down the room.

"I thought so," he said. "I hoped so. It seemed to me that the precautions I had taken placed us absolutely outside the zone of danger. As the years have passed away, and you have grown more and more careless until one were inclined to laugh at your own fears, to wake up, as I did an hour ago, to the knowledge that the danger is not only threatening, but actually here—"

"Here!" Cotter cried, his voice rising almost to a scream. "You don't mean it, sir. You are joking. You are playing with your old servant. The mere thought of it brings my heart into my mouth and sets me trembling."

By way of reply Flower proceeded to explain the strange occurrence in the conservatory. When he had finished he laid the piece of silken thread upon the table. Its effect upon Cotter was extraordinary. He tore frantically at his scanty grey hair. Then he laid his head upon the table and burst into a flood of senile tears.

"What is the good of going on like that?" Flower said irritably. "There is work to be done and no time to be lost. I know you are bold enough in the ordinary course of things, and can face danger when you see it. The peculiar horror of this thing is its absolute invisibility. But we shall have to grapple with it. We shall have to fight it out alone. But, first of all, there is something to be done which admits of no delay. I sent into Oldborough for a doctor, and who should turn up but that very man Mercer, who nearly succeeded in bringing a hornet's nest about our ears over that affair of the Guelder Rose? I should never have remembered the fellow if he had not foolishly let out that he was a ship's doctor, and naturally I kept my information to myself."

"You know what I want done. That man is poor and struggling. He has to be crushed. Find out all about him. Find out what he owes and where he owes it. Then you can come to me and I will tell you how to act. No half measures, mind. Mercer is to be driven out of the country and he is not to return."

Cotter grinned approvingly. This was a commission after his own heart. But from time to time his eyes wandered to that innocent-looking piece of string upon the table, and his face glistened with a greasy perspiration.

"And about that, sir?" he asked, with a shudder.

"That will have to keep for the moment. I want you to go to the post-office and fetch the letters. I am expecting something very important from our agents in Borneo, and you will probably find a registered letter from them. It relates to that matter of Chutney and Co. It will be written in a cypher which you understand as well as I do. You had better open it and read it, in case there may be urgent reasons for cabling a reply at once. As soon as this business is done with and out of the way, Cotter, the better I shall be pleased. It is a bit dangerous even for us. Of course, we can trust Slater, who does everything himself and always uses the cypher, which I defy even Scotland Yard to unravel. Still, as I said before, the work is dangerous, and I will never take on a scheme like that again. You had better use one of the cars as far as the post-office to save time."

"I shall be glad to," Cotter muttered. "I should never dare to walk down to the village in the dark after seeing this infernal piece of string. The mere sight of it makes me shiver."

Cotter muttered himself out of the room and Flower was left to his own thoughts. He sat for half an hour or more till the door opened and Cotter staggered into the room. He held in a shaking hand an envelope marked with the blue lines which usually accompany registered letters.

"Look at it," he mumbled. "That came straight from Borneo, written by Slater himself, sealed with his own private seal, and every line of it in cypher. I should be prepared to swear that no one but Slater had touched it. And then when I come to open the envelope, what do I find inside? Why, this! This! This!"

With quivering fingers Cotter drew the letter from the envelope and unfolded the doubled-up page. From the middle of it dropped a smooth silken object which fell upon the table. It was another mysterious five-knotted string.

Master and man stared at each other blankly. Unmistakable fear was visible in the eyes of both. And yet those two standing there face to face were supposed not to know what fear meant. There was something ridiculous in the idea that an innocent looking piece of string should produce so remarkable an effect. It was long before either spoke. Flower paced up and down the room, his thin lips pressed together, his face lined with anxiety.

"I cannot understand it at all," he said at length. "I thought this danger was ended."

"But there it is," Cotter replied. "If these people were not so clever I should not mind. And the more you think of it, sir, the worse it becomes. Fancy that message finding its way into Slater's letter. The thing seems almost impossible; like one of those weird conjuring tricks we used to see in India. And Slater is a cautious man who runs no risks. He wrote that letter in his own hand. He posted it himself you may be sure. And from the time that it dropped into the letter-box to the time it reached my hand, nobody but the postal officials touched it. Yet there it is, sir, there it is staring us in the face, more deadly and more dangerous than a weapon in the hands of a lunatic. Still, we have got our warning, and I dare say, we shall have time—"

"But shall we?" Flower said impatiently. "Don't be too sure. You have forgotten what I told you about Miss Galloway and the mysterious hand that was trying to force a way into the conservatory. She doesn't know the significance of that attempt, and there is no reason why she should. But, we know, Cotter. We know only too well that the danger is not only coming, but that it is here. Unless I am mistaken it threatens us from more quarters than one. But it is folly to discuss this matter when there is so much to be done. I have friends coming to dinner, curse it, and more are expected later in the evening. I must leave this matter to you and you must do the best you can. Prowl about the place, Cotter. Keep your eyes open. Pry into dark corners. See that all the windows are closed. Perhaps you might also explain something of this to the keeper, and ask him to chain one or two dogs up near the house. They may be useful."

Cotter acquiesced, but it was evident from the expression of his face that he did not feel in the least impressed by his employer's suggestions. This dark, intangible danger was not to be warded off by commonplace precautions. For some time after Cotter had gone Flower sat at his table thinking deeply. The longer he pondered the matter, the more inexplicable it became. Beatrice's discovery was grave enough, but this business of the registered letter was a thousand times worse. Nobody appreciated daring, audacity and courage more than Flower. He knew what a strong asset they were in success in life; indeed, they had made him what he was. But this cleverness and audacity were far beyond his own. He took up the silken string and twisted it nervously in his fingers.

"What is it?" he murmured. "How is the thing done? And why do they send on this warning? What a horrible business it all is! To be hale and hearty one minute and be found dead the next, and not a single doctor in the world able to say how the end is brought about! And when you tackle those fellows there is no safety. Why shouldn't they bribe some dissolute scamp of an Englishman to do the same thing after showing him the way. There are dozens of men in the city of London who would put an end to me with pleasure, if they could only do so with impunity."

Flower rose wearily and left the library. He was tired of his own thoughts and for once had a longing for human society. As he went along the corridor leading to the hall, one of the maids passed him with a white face and every sign of fear and distress. With a feeling of irritation he stopped the girl and inquired what was the matter.

"What has come to the place?" he muttered. "And what have you been crying about? Aren't you Miss Galloway's' maid?"

"Yes, sir," the girl murmured. "It is nothing, sir. As I was coming from the wood at the back of the house, on my way home from the village, I had a fright. I told Miss Galloway about it and she told me not to be silly. I dare say if I had looked closer, I should have found that—"

The girl's voice trailed off incoherently and Flower suffered her to go away. It was not for him to trouble himself over the fears and fancies of his servants, and at any other time he would have shown no curiosity. But in the light of recent events even a little thing like this had its significance. At any rate, he would ask Beatrice about it.

Beatrice was in the drawing-room putting the finishing touches to the flowers. It would soon be dinner-time.

"I have just met your maid," Flower said. "What on earth is the matter with the girl? She looks as if she has seen a ghost. I hope to goodness the servants haven't been talking and making a lot of mischief about this story that a former lord of Maldon Grange walks the corridors at nights. If there is one form of superstition I detest more than another, it is that."

"You would hardly call Annette a superstitious girl," Beatrice replied. "As a rule she is most matter of fact. But she came in just now with the strangest tale. She had been to the village to get something for me, and as she was rather late she came home through the pine wood. She declares that in the middle of the wood she saw two huge monkeys sitting on the grass gesticulating to one another. When I pointed out to her the absurdity of this idea, she was not vexed with me, but stuck to her statement that two great apes were there and that she saw them quite distinctly. Directly she showed herself they vanished, as if the ground had opened and swallowed them up. She doesn't know how she managed to reach home, but when she got back she was in great distress. Of course it is possible Annette may be right in a way. I saw in a local paper the other day that there is a circus at Castlebridge, which has taken one of the large halls for the winter. The account that I read stated that one or two animals had escaped from the show and had caused a good deal of uneasiness in the neighbourhood. As Castlebridge is one about twenty miles from here, perhaps Annette was right."

Flower muttered something in reply. At first he was more disturbed than Beatrice was aware, but her news about the circus seemed plausible and seemed to satisfy him.

"It is very odd," Beatrice went on, "that we should have these alarming incidents simultaneously. For the last year or two we have led the most humdrum existence, and now we get two startling events in one day. Can there be any connection between them?"

"No, of course not," Flower said roughly. "Tell the maid to keep her information to herself. We don't want to start a rumour that our woods are full of wild animals, or the servants will leave in a body. I'll write to the police to-morrow. If these animals are roaming about they must be captured without delay."

Flower made his way upstairs to his room to dress for dinner. Usually he had little inclination for social distractions, for his one aim in life was to make money. To pile up riches and get the better of other people was both his profession and his relaxation. Still, there were times when he liked to display his wealth and make his power felt, and Beatrice had a free hand so far as local society was concerned. But for once Flower was glad to know he would have something this evening to divert his painful thoughts into another channel. Try as he would he could not dismiss Black Care from his mind. It was with him when he had finished dressing and came down into the drawing-room.

Was it possible, he asked himself, there could be any connection between the maid's story and the more startling events of the day? Surely it was easy for a hysterical girl to make a mistake in the dark.

But further debate was no longer practicable, for his guests were beginning to arrive. They were Beatrice's friends rather than his. From beneath his bushy eyebrows he regarded them all with more or less contempt. He knew perfectly well they would have had none of him but for his money. For the most part they were here only out of idle curiosity, to see such treasures as Maldon Grange contained. Only one or two perhaps are people after Flower's own heart. Well, it did not matter. Whatever changed the tenor of his thoughts and led his mind in new directions was a distinct relief. He sat taciturn and sombre till dinner was announced.

Wilfrid Mercer had walked back to Oldborough very thoughtfully. The event of the past hour or two appeared to have changed the whole current of his existence. He had parted with the old life altogether, and had set himself down doggedly to the humdrum career of a country practitioner. No more long voyages, no adventures more exciting than the gain of a new patient or the loss of an old one. He had not disguised from himself that life in Oldborough would be monotonous, possibly nothing but a sordid struggle. But he would get used to it in time, and perhaps even take an interest in local politics.

But already all was changed. It was changed by a simple accident to Samuel Flower. There was some inscrutable mystery here and, to a certain extent, Wilfrid held the key to it. It seemed to him, speaking from his own point of view, that he knew far more about the affair than Flower himself.

It was as well, too, that nothing should have happened to cause Beatrice Galloway any fear for the future. She might be puzzled and curious, but Wilfrid did not believe that she attached any significance to the piece of string. The string she found appeared to have been dropped by accident as, no doubt, it was; but behind that there lay something which spoke only to Wilfrid Mercer and Samuel Flower.

The more Wilfrid debated the matter, the more certain did he feel that Flower saw in this thing a deadly menace to himself. Wilfrid had not forgotten the look of livid fear on Flower's face when Beatrice handed the string to him. He had not forgotten the sudden cry that burst from Flower's lips. He did not believe that the ship-owner suffered from neuralgia. The most important point was to find out whether Flower understood the nature of the warning: Did he know that the mystery had been hatched in the Malay Archipelago? Did he know that the natives there had invented a mode of taking life which baffled even modern medical science? If Flower knew, then he might make a bold bid for life and liberty. If not, then his very existence was in peril.

So far Wilfrid's reasoning was clear. But now he struck against a knot in the wood and his plane could go no further. What connection was there between a prosaic British citizen like Samuel Flower and a bloodthirsty Malay on the prowl for vengeance? So far as Wilfrid knew, Flower had spent the whole of his life in London, where such contingencies are not likely to occur. The point was a difficult one to solve, and Wilfrid was still hammering at it when he reached home. Something like illumination came to him while dressing for dinner.

He wondered why he had not thought of it before. Of course, as a ship-owner, Samuel Flower would come in contact with all sorts and conditions of men. The crews of the Flower Line were drawn from all parts of the world. And amongst them Malays and Lascars figured prominently. Wilfrid recollected that there had been many Malays engaged in the mutiny on the Guelder Rose. Matters began to grow more clear.

The night was fine and bright, and the sky full of stars as Wilfrid set out to walk to Maldon Grange. He would not he justified in the extravagance of a cab, for the distance was not more than four miles, and he had been told of a short cut across the fields. At the end of half an hour a moon crept over the wooded hills on the far side, so that objects began to stand out clear and crisp. Here was the path he must follow, and there were the spinneys and covers with which Maldon Grange was surrounded. Most of the fallen leaves were rotting under foot. The ride down which Wilfrid had turned was soft and mossy to his tread. He went along so quietly that he did not even disturb the pheasants roosting in the trees. He passed a rabbit or two so close that he could have touched them with his walking stick. The rays of the moon penetrated the branches here and there and threw small patches of silver on the carpet of turf. Wilfrid had reached the centre of the wood where the undergrowth had been cleared away recently. Looking down the long avenue of trees, it seemed as if he were standing in the nave of a vast cathedral filled with great stone columns. For a moment he stood admiring the quiet beauty of it. Then he moved on again. His one thought, was to reach his destination. He did not notice for a moment or two that a figure was flitting along the opening to his left or that another figure a little way off came out to meet it. When he did become aware that he was no longer alone he paused in the shadow of a huge beech and watched. He did not want to ask who these people were. Probably he was on the track of a couple of poachers.

But though the figures stood out clearly in the moonlight, Wilfrid could see no weapons, or nets, or other implements of the poaching trade. These intruders seemed to be little more than boys if size went for anything, and, surely two poachers would not have seated themselves on the grass and proceeded to light a fire as these men were doing now. They sat gravely opposite one another talking and gesticulating in a way not in the least like the style of phlegmatic Englishmen. In a fashion, they reminded Wilfrid of two intelligent apes discussing a handful of nuts in some zoological garden. But then apes were not clothed, and these two strangers were clad. It was, perhaps, no business of his, but he stood behind the shadow of a tree watching them. He saw one reach out and gather a handful of sticks together; then a match was applied and the whole mass burst into a clear, steady and smokeless flame. The blaze hovered over the top of the sticks much as the flame of a spirit lamp might have done. With Wilfrid's knowledge of camp fires he was sure that a casual handful of sticks would never give so clear and lambent a flame. He forgot all about his appointment at Maldon Grange, his curiosity overcoming every other feeling. He really must discover what these fellows were doing.

It was easy to creep from tree to tree until he was within thirty or forty yards of the two squatting figures. He saw that the fire was burning as brightly and clearly as ever. He saw one of the strangers produce a small brass pot into which he dropped a pinch or two of powder. Then the vessel was suspended over the fire, and a few moments later a thin violet vapour spread itself out under the heavy atmosphere of the trees until the savour of it reached the watcher's nostrils. It was a weird sort of perfume, sweet and intensely soothing to the nerves. It seemed to Wilfrid that he had never smelt the like of it before, and yet there was a suggestion of familiarity about it. Where had he been in contact with such vapour? How did it recall the tropics? Why was it associated with some tragedy? But rack his brains as he might he could make nothing of it. He felt like a man who tries to fit together the vague outlines of some misty dream. Doubtless it would come to him presently, but for the moment he was at fault. His idea now was to creep farther forward and try to see something of the faces of this mysterious pair. The mossy carpet under foot was soft enough, but there was one thing Wilfrid had not reckoned on. Placing his foot on a pile of dead leaves a stick underneath snapped suddenly with a noise like a pistol-shot. In a flash Mercer crouched down, but it was too late. As if it had been blown out with a fierce blast of wind, the fire was extinguished, the brass pot vanished, and the two figures dissolved into thin air. It was amazing, incredible. Here were the scattered trees with the moonlight shining through the bare branches. Here was the recently cleared ground. But where had those wanderers vanished? Wilfrid dashed forward hastily, but they had gone swiftly and illusively as a pair of squirrels. Mercer drew his hand across his eyes and asked whether he were not the victim of hallucination. It was impossible for those men to have left the wood already. And, besides, there were the charred embers of the sticks yet warm to the touch, though there was no semblance of flame, or even a touch of sullen red. There was nothing but to go on to Maldon Grange and wait the turn of events. That these strangers were after no good Wilfrid felt certain. But whether they had or had not any connexion with the warning to Samuel Flower he could not say. He would keep the discovery to himself.

He was in the house at length. He heard his name called out as he entered the drawing-room. He was glad when Beatrice came forward, for he felt a little shy and uncomfortable before all these strangers.

"I am so glad you came," Beatrice murmured. "Stay here a moment. I have something important to say to you."

Beatrice emerged from a throng of chattering people presently and Wilfrid followed her into the hall.

"I hope you don't mind," she said, "but I should like you to see my maid. It may be nothing but a passing fit of hysteria, but I never saw her so nervous before. She went to the village on an errand this afternoon, and when she came back she told me she had been frightened by two large monkeys in the pine wood behind the house. She said that they vanished in a most extraordinary way. I should have put the whole thing down to sheer imagination if I had not known that some animals have escaped recently from the circus at Castlebridge."

"It is possible the girl spoke the truth," said Wilfrid, with a coolness he was far from feeling, "but I will see her with pleasure. I daresay if I prescribe something soothing you can send into Oldborough and get it made up."

Wilfrid returned by and by with the information that there was nothing the matter with the maid and that her story seemed clear and coherent. There was no time for further discussion, as Flower came forward and enlisted Wilfrid to make up a hand at bridge. The house was looking at its best and brightest now. All the brilliantly lighted rooms were filled with a stream of gaily-dressed guests. The click of the balls came from the billiard-room. It seemed hard to associate a scene like this, the richest flower of the joie de vivre, with the shadow of impending tragedy, and yet it lurked in every corner and was even shouting its warning aloud in Wilfrid's ears. And only a few short hours ago everything was smooth, humdrum, monotonous.

"I hope you are not in any hurry to leave," Flower murmured as he piloted Wilfrid to the card table. "Most of these chattering idiots will be gone by eleven, and there is something that I have to say to you."

"I shall be at your service," Wilfrid said. "I will stay as long as you please. In any case I should like to have another look at your hand before I go."

Flower turned away apparently satisfied and made his way back to the billiard-room. For a couple of hours and more the guests stayed enjoying themselves until, at length, they began to dribble away, and with one solitary exception the card tables were broken up. Wilfrid lingered in the hall as if admiring the pictures, until it seemed that he was the last guest. It was a little awkward, for Flower had disappeared and Beatrice was not to be seen. She came presently and held out her hand.

"I am very tired," she said. "My uncle wants to see you before you go and I know you will excuse me. But I hope we shall not lose sight of one another again. I hope you will be a visitor at the Grange. Please tell your mother for me that I will come and call upon her in a day or two."

"Is it worth while?" Wilfrid asked somewhat sadly. "We are poor and struggling, you know, so poor that this display of luxury and wealth almost stifles me."

"We have always been such good friends," Beatrice murmured.

"I hope we always shall be," Wilfrid replied. "I think you know what my feelings are. But this is neither the time nor place to speak of them."

He turned away afraid to say more. Perhaps Beatrice understood, for a pleasant smile lighted up her face and the colour deepened in her cheeks. At the same moment Flower came out of the library. He glanced suspiciously from one to the other. Little escaped those keen eyes.

"You had better go to bed, Beatrice," he said abruptly. "I have some business with Mr. Mercer. Let us talk it over in the billiard room. I can't ask you in the library because my man Cotter will be busy there for the next half-hour."

In spite of his curtness it was evident that Flower was restless and ill at ease. His hand shook as he poured out the whisky and soda, and his fingers twitched as he passed the cigarettes.

"I am going to ask you a question," he said. "You recollect what you told us this afternoon about that Borneo incident—about the man whom you found dead in such extraordinary circumstances. I couldn't put it to you more plainly this afternoon before my niece, but it struck me that you knew more than you cared to say. Did you tell us everything?"

"Really, I assure you there is no more to be said," Wilfrid exclaimed. "The victim was practically a stranger to me, and I should have known nothing about it if I had not been fetched. I am as puzzled now as I was then."

Flower's brows knitted with disappointment.

"I am sorry to hear that," he said. "I thought perhaps you had formed some clue or theory that might account for the man's death."

"I assure you, nothing," Wilfrid said. "I made a most careful examination of the body; in fact, I went so far as to make a post-mortem. I could find nothing wrong except a certain amount of congestion of the brain which I attributed then and do still to the victim's dissipated habits. Every organ of the body was sound. All things considered, the poor fellow's blood was in a remarkably healthy state. I spared no pains."

"Then he might have died a natural death?"

"No," Wilfrid said firmly. "I am sure he didn't. I am convinced that the man was murdered in some way, though I don't believe that any surgeon could have put his hand upon the instrument used or have indicated the vital spot which was affected. I admit that I should have allowed the matter to pass if I had not found that strange piece of string knotted round the brows. It would be absurd to argue that the string was the cause of death, but I fancy that it was a symbol or a warning of much the same sort that the conspirators in the olden days used when they pinned rough drawings of a skull and cross-bones to the breasts of their victims."

Flower was listening with his whole mind concentrated upon the speaker's words. He seemed as if he changed his mind. From the breast-pocket of his dress-coat he produced a letter, and from it extracted a piece of knotted string.

"Of course you recognise this?" he asked.

"I do," Wilfrid said. "It is the piece which Miss Galloway picked up this afternoon."

"Well, it isn't," Flower said with a snarl. "This is another piece altogether. I hold in my hand, as you see, a letter. This letter was sent me from Borneo by one of my agents. It is connected with a highly complicated and delicate piece of business, the secret of which is known only to my agent, to my secretary and myself. The letter is written in cypher in my agent's own handwriting. I know that from the time it was written to the time it was posted it was never out of his hand. It reached me with every seal intact, and yet, neatly coiled up inside, was the identical piece of string which you are looking at now. I should like to know, Dr. Mercer, how you account for that?"

"I couldn't," said Wilfrid. "Nobody could explain such an extraordinary occurrence. Of course, there is a chance that your agent himself might—"

"Nothing of the kind," Flower put in. "He is not that sort of man. Besides, if he had been, there must have been some explanation in the letter, whereas the thing is not alluded to at all. Frankly, I am disappointed that you can give me no further information. But I will not detain you longer."

"One moment," Wilfrid said. "I must have a look at your hand before I go. It is as well to be on the safe side."

"One moment," Flower said. "I'll see if my man Cotter has finished, then I will come back to you."

Wilfrid was not sorry to be alone, for this was fresh material for his already bewildered thoughts. There was danger pressing here, but from what quarter, and why, it was impossible to determine. Yet he was convinced the hand of tragedy was upon the house, and that all Flower's wealth, all his costly possessions, would never save him from the shadow of the coming trouble. This pomp and ostentation, these beautiful chairs and tables and carpets and pictures were no more than a hollow mockery.

Time was creeping on and yet Flower did not return. The hands of the clock over the billiard-room mantle-piece moved onwards till the hour of twelve struck, and still Flower made no sign. It seemed to Wilfrid that the subtle scents of the blooms which lined the hall and overflowed into the billiard-room were changing their scent, that the clear light thrown by the electrics was merging to a misty blue. He felt as if a great desire to sleep had overtaken him. He closed his eyes and lay back. Where had he smelt that perfume?

He jumped to his feet with a start. With a throbbing head he darted for the window. He knew now what it was—the same pungent, acrid smell those men were making in their fire under the trees. Was it deadly? A moment's delay might prove fatal.

Beatrice sat before the fire in her bed-room looking thoughtfully into the glowing coals. If appearances counted for anything she ought to have been a happy girl, for she seemed to lack nothing that the most fastidious heart could desire. Samuel Flower passed rightly enough for a greedy, grasping man, but he never displayed these qualities so far as his niece's demands were concerned. The fire was burning cheerfully on the tiled hearth, the red silk curtains were drawn against the coldness of the night, the soberly-shaded electric lights glinted upon silver and gold and jewels scattered about Beatrice's dressing-table. The dark walls were lined with pictures and engravings; here and there were specimens of the old china that the mistress of the room affected. Altogether it was very cosy and very charming. It was the last place in the world to suggest crime or trouble or catastrophe of any kind.

But Beatrice was not thinking about the strange events of the evening, for her mind had gone back to the time when she first met Wilfrid Mercer in London. He had been introduced by common friends, and from that time Beatrice had contrived to see a good deal of him. From the first she had liked him, perhaps because he was so different from the young men of her acquaintance. Samuel Flower's circle had always been a moneyed one, and until she had known Wilfrid Mercer, Beatrice had met few men who were not engaged in finance. They belonged, for the most part to the new and pushing order. Their ways and manners were not wholly pleasing to Beatrice. Perhaps she had been spoilt. Perhaps she valued money for the pleasure it brought, and not according to the labour spent in the gaining of it. At any rate she had been at few pains to show a liking for her environment before Wilfrid's visit. Here was a man who knew something of the world, who could speak of other things than the City and the latest musical comedy. There was that about his quiet, assured manner and easy unconsciousness that attracted Beatrice. She knew as every girl does when the right man comes, that he admired her. Indeed he had not concealed his feelings. But at that time Wilfrid was ignorant of Beatrice's real position. Naturally enough, he had not associated her with Samuel Flower. He had somehow come to imagine that her prospects were no better than his own. There had been one or two delightful evenings when he had spoken freely of his future, and Beatrice had thrilled with pleasure in knowing why he had made a confidante of her. He had said nothing definite, but the girl understood intuitively that one word from her would have brought a declaration to his lips.

It was a pretty romance and Beatrice cherished it. The whole episode was in sharp contrast with her usual hard, brilliant surroundings. Besides, there was a subtle flattery in the way in which he had confided in her. She had intended to keep her secret and not let Wilfrid know how grand her prospects were till she had talked the matter over with her guardian. That Flower would give his consent she did not doubt for a moment. He had no matrimonial views for her. Indeed, he had more than once hinted that if she cared to marry any really decent fellow he would put no obstacle in the way. Perhaps he knew enough of his own circle to feel convinced that none of them were capable of making Beatrice happy.

These were the thoughts that stole through the girl's mind as she sat in front of the fire. She was glad to know that Wilfrid had not forgotten her. She had read in his eyes the depth and sincerity of his pleasure. He had told her frankly enough, that he was taken aback at her position, and the statement had showed to Beatrice that there was no change in his sentiments regarding her.

He would get used to her wealth in time. He would not love her any the less because she would come to him with her hands full. Ay, and she would come ready and willing to lift him beyond the reach of poverty.

"How silly I am!" the girl murmured. "Here am I making a regular romance out of a common-place meeting between two people who have done no more than spend a few pleasant evenings together. Positively I blush for myself. And yet—"

The girl rose with a sigh, conscious that she was neglecting her duties. She had come to her room without a thought for her maid who might be requiring attention. She stole across the corridor to the room where Annette lay. The lights were nearly all out and the corridor looked somewhat forbidding in the gloom. The shadows might have masked a score of people and Beatrice been none the wiser, a thought which flashed upon her as she hurried along. All the time she had lived at Maldon Grange she had never been troubled by timorous fears like these. Perhaps the earlier events of the evening had got on her nerves. She could see with fresh vividness that long, thin, skinny hand fumbling for the lock of the conservatory door.

It was too ridiculous, she told herself. Doubtless that prowling tramp was far enough away by this time. Besides, there were too many dogs about the place to render a burglary likely. At the end of the corridor Beatrice's little terrier slept. The slightest noise disturbed him: his quick ear detected every sound. Doubtless those shadows shrouding the great west window contained nothing more formidable than the trailing plants and exotic flowers which Beatrice had established there.

The door of the maid's room was open and the girl lay awake. Beatrice could see that her face was damp and pale and that the girl's eyes were full of restless fear. She shook her head reproachfully.

"This is altogether wrong," she said. "Dr. Mercer told you to go to sleep at once. Really, Annette, I had no idea you were so nervous."

"I can't help it, miss," the girl whined. "I didn't know it myself till this afternoon. But every time I close my eyes I see those horrible creatures dancing and jabbering, till my heart beats so fast that I can hardly breathe."

"You know they were animals," Beatrice protested. "They escaped from the circus in Castlebridge. I read about it in the papers. Doubtless they have been recaptured by now."

Annette shook her head doubtfully.

"I don't believe it, miss," she whispered. "I have been lying here with the door open and the light of the fire shining on the wall opposite in the corridor, as you can see at this moment. I had almost persuaded myself the thing was a mere fright when I saw a shadow moving along the wall."

"One of the servants, of course."

"I wish I could think so, miss," the girl went on. "But it wasn't like anybody in the house. It was short and thick with enormously long arms and thin crooked fingers. I watched it for some time. I would have called out if I only dared. And then when it vanished I was ashamed to speak. But it was there all the same. Don't leave me, miss."

The last words came in a beseeching whisper. With a feeling of mingled impatience and sympathy Beatrice glanced round the room. A glass and a bottle of medicine stood by the bed-side.

"I declare you are all alike," Beatrice exclaimed. "If you go to a dispensary and get free medicine you swallow it like water. But when a regular doctor prescribes in this fashion you won't touch it. Now I am going to give you your draught at once."

The girl made no protest. Apparently she was ready to do anything to detain Beatrice by her side. She accepted the glass and swallowed the contents. A moment or two later she closed her eyes and in five minutes was fast asleep. As the medicine was a sleeping draught Annette would not wake before morning. Closing the door behind her Beatrice crept back to her room, looking fitfully over her shoulder as she walked along. She had caught something of Annette's nameless dread, though she strove to argue with herself about its absurdity. She glanced over the bannisters and noted the lights in the hall below. Seemingly her guardian had not retired. She found herself wondering if Wilfrid Mercer was still in the house. At any rate, it was pleasant to think there was help downstairs if necessary.

"I'll go to bed," Beatrice resolved. "I dare say I shall have forgotten this nonsense by the morning. That is the worst of an old house like this, these gloomy shadows appeal so to the imagination."

Nevertheless, Beatrice dawdled irresolutely before the fire. She would go out presently and see that her dog was in his accustomed place. Usually he was as good as half-a-dozen guardians.

As Beatrice stood there she began to be conscious that the room was becoming filled with a peculiar, sweet odour; the like of which she had never smelt before. Perhaps it came from her flowers. She would go and see. She stepped out in the darkness and paused half hesitating.

The strange sickly scent went as quickly as it had come. The air cleared and sweetened once more. It was very odd, because there was no draught or breath of air to cleanse the atmosphere. Doubtless the scent had proceeded from the tropical flowers at the end of the corridor. Many new varieties had been introduced recently, strange plants to Beatrice, some of them full of buds which might open at any moment. Perhaps one of these had suddenly burst into bloom and caused the unfamiliar odour.

Beatrice hoped that the plant might not be a beautiful one, but if it were she would have to sacrifice it, for it would be impossible to live in its neighbourhood and breath that sickly sweet smell for long. In another moment or two she would know for herself. She advanced along the corridor quickly with the intention of turning up the lights and finding the offending flower. She knew her way perfectly well in the dark. She could have placed her hands upon the switches blindfold. Suddenly she stopped.

For the corridor was no longer in darkness. Some ten of fifteen yards ahead of her in the centre of the floor and on the thick pile of the Persian carpet was a round nebulous trembling orb of flickering blue flame. The rays rose and fell just as a fire does in a dark room, and for the moment Beatrice thought the boards were on fire.

But the peculiar dead-blue of the flame and its round shape did not fit in with its theory. The fire was apparently feeding upon nothing, and as Beatrice stood there fascinated she saw it roll a yard or two like a ball. It moved just as if a sudden draught had caught it—this strange will-o'-the-wisp at large in a country house. Beatrice shivered with apprehension wondering what was going to happen next. She could not move, she could not call out for she was now past words. She could only watch and wait developments, her heart beating fast.

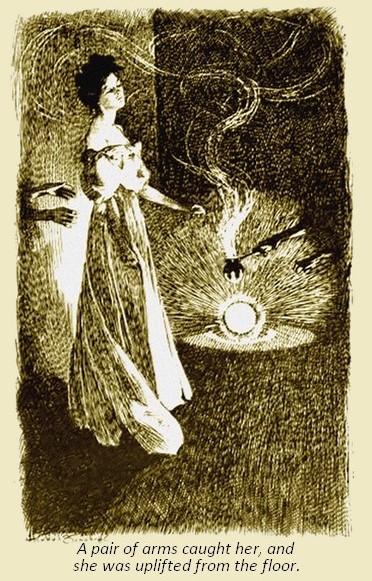

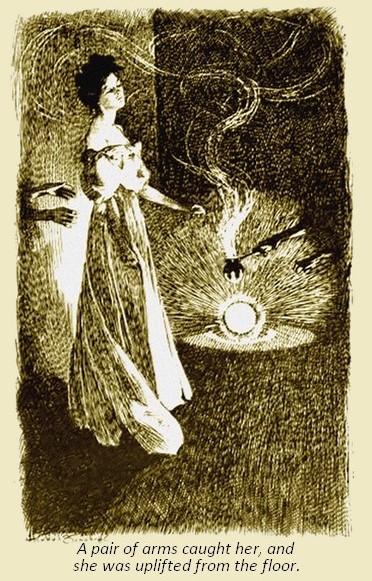

And developments came. For the best part of a yard a fairly strong glow surrounded the sobbing blue flame. Out of the glow came a long, thin, brown hand and arm, the slim fingers grasping a small brass pot and holding it over the flame. Almost immediately a dusty film rose from the pot and once again that sickly sweet perfume filled the corridor. Beatrice swayed before it, her senses soothed, her nerves numbed, until it seemed to her that she was falling backwards to the ground. A pair of arms caught her and she was lifted from the floor and carried swiftly along to her own room. It was all like a dream, from which she emerged by and by, to find herself safe and sound and the door of her room closed. She shook off the fears that held her in a grip of iron and laid her hand on the knob. The lock was fastened on the outside.

What did it mean? What terrible things were happening on the other side of that locked door? It was useless to cry for help, for the walls were thick and no one slept in the same corridor but herself. All the servants had gone to bed long ago. Therefore, to ring the bell for help would be useless. All Beatrice could do was to wait and hope for assistance, and pray that this blue terror overhanging the house was not destined to end in tragedy. Perhaps this was an ingenious method by which modern thieves rifled houses with impunity and got away with their plunder before alarm could be raised. It seemed feasible, especially as she recollected that her dog had not challenged the intruders. She hoped nothing had happened to the terrier. She could not forget her tiny favourite even at this alarming moment.

Meanwhile, help was near at hand, as Beatrice expected. In the billiard-room Wilfrid Mercer had come to his senses, and made a dash for the window. He knew now that some dire catastrophe was at hand. He did not doubt that this was the work of the two strangers whom he had seen under the trees. In fact, with the scent burning and stinging in his nostrils there was no room for question. Whether the stuff was fatal or not he did not know, and there was no time to ask. The thing to do was to create a powerful current throughout the house and clear the rooms and passages.

He thought of many things in that swift moment. His mind went flashing back to the time when he had encountered the dead English man in the Borneo hut with that knotted skein about his forehead. He thought about the strange discovery in the afternoon when those five knots had so mysteriously appeared again. He thought most of all of Beatrice and wondered if she were safe. All this shot through his mind in the passing of a second between the time he rose from his chair, and fumbled for the catch of the windows opening on to the lawn. He had his handkerchief pressed tightly to his face. He dared not breathe yet. His heart was beating like a drum.

But the catch yielded at last. One after the other the windows were thrown wide and a great rush of air swept into the room causing the plants to dance and sway and the masses of ferns to nod their heads complainingly. It was good to feel the pure air of Heaven again, to fill the lungs with a deep breath, and note the action of the heart growing normal once more. The thing had passed as rapidly as it had come and Wilfrid felt ripe for action. He was bold enough to meet the terror in whatever way it lifted up its head. As he turned towards the hall Cotter staggered into the room. His face white and he shook like a reed in the wind. His fat hands were rubbing nervously together and he was the very embodiment of grotesque, almost ludicrous, fright.

"After all these years," he muttered, "after all these years. I am a wicked old man, sir, a miserable old wretch who doesn't deserve to live. And yet I always knew it would come. I knew it well enough though Mr. Flower always said we had got the better of those people. But I never believed it, sir, I never believed it. And now when I have worked and toiled and slaved to enjoy myself in my old age I am going to die like this. But it wasn't my fault, sir. I didn't do it. It was Flower. And if I had only known what was going to happen I would have cut my right hand off rather than have gone to Borneo ten years ago."

"In the name of common sense, what are you jabbering about?" Wilfrid said impatiently.

But Cotter did not hear. He had not the remotest idea whom he was talking to. He wandered in the same childish manner, rubbing his hands and writhing as if he were troubled with fearful inward pains.

"Can't you explain?" Wilfrid asked. "So you two have been to Borneo together, eh? That tells me a good deal. In the meantime, what has become of Mr. Flower?"

Apparently Cotter had a glimmer of sense for he grasped the meaning of the question.

"He is in there," he said vaguely, "in the library with them. Oh, why did I ever come to a place like this?"

Again the vague terror seemed to sweep down on Cotter and sway him to and fro as if the physical agony were more than he could bear. It was useless to try to extract any intelligent information out of this sweat-bedabbled wretch. And whatever happened Flower must be left to his own device for the moment. Doubtless he had brought all this upon himself, and if he had to pay the extreme penalty, why, then, the world would be little the worse for his loss. But there was somebody else whose life was far more precious. Wilfrid bent over the quaking Cotter and shook him by the shoulders much as a terrier shakes a rat.

"Now, listen to me, you trembling coward," he said between his teeth. "Try to get a little sense into that muddled brain of yours. Where is Miss Galloway, and where is she to be found?"

"Don't," Cotter groaned. "Do you want to murder me? I suppose Miss Galloway is in her bedroom."

"I can guess that for myself," Wilfrid retorted. "Show me her room."

"Oh, I will," Cotter whined. "But don't ask me to move from here, sir. It would be cruel. It is all very well for a young man like you who doesn't know—"

"If you won't come, I will take you see by the scruff of your neck and drag you upstairs," Wilfrid said grimly.

He caught hold of Cotter's limp arm and propelled him up the stairs. The atmosphere was clean and sweet now, though traces of the perfume lingered. Cotter, hanging limply from Wilfrid's arm, pointed to a door. Then he turned and fled holding on by the bannisters. It was no time to hesitate so Wilfrid tapped at the door. His heart was in his mouth and waited with sickening impatience for a reply. Suppose the mischief had been done! Suppose he should be too late! He had with difficulty saved himself. Then he gave a gasp of relief as he heard the voice of Beatrice asking who was there.

"It is I, Mercer," he said. "There is no time to lose. Will you unlock the door?"

"I cannot," Beatrice replied. Her voice was low, but to Wilfrid's relief quite steady. "The door is locked on the outside. I am so thankful you have come."

Wilfrid turned the key. With a great thrill of delight he saw that Beatrice was little the worse for what she had gone through. He indulged in no idle talk but reached out his hand in search of one of the electric switches. Beatrice grasped Wilfrid's meaning. She stretched out her hand and immediately the corridor was flooded with light.

"I cannot understand it," she murmured. "Dr. Mercer, what does it mean?"

"Perhaps you had better tell me your experience first," Wilfrid suggested. "If I can throw any light afterwards on this hideous mystery I shall be glad."

"I'll tell you as collectedly as I can," Beatrice replied. "I had almost forgotten the alarm I had in the conservatory this afternoon when I came up to bed. I sat for a while dreaming over the fire—"

Beatrice stopped and a little colour crept into her face. She wondered what Wilfrid would say if he only knew what she had been thinking about. He nodded encouragingly.

"Then I suddenly recollected that I had not seen Annette. When I reached her room I found her wide awake and as terrified as when she came back from the village. I suppose she was too upset to take your medicine, for the bottle stood unopened on the table. After I had given it to her she went off to sleep almost immediately, but not before she had told me something which disturbed me very much. As she lay with the bedroom door open, the firelight shone upon the wall on the other side of the corridor, and she declared she had seen a shadow on the wall like one of the figures that had frightened her in the wood. I pretended to be angry and incredulous, but I confess that I was really rather startled. It seemed so strange that a quiet country house should suddenly be invested with such an atmosphere of mystery. Why did that man try to get into the conservatory? And why were those figures?—but I am wandering from the point."

"I think we had better have facts at first," Wilfrid said.

"Oh, yes. Well, I went back to my room after seeing Annette to sleep, and I fear I must own to feeling considerably frightened. It was a relief to find that somebody was still about downstairs, and to remember that there were so many dogs about the house. Then I remembered my little terrier who always sleeps on a mat at the end of the corridor. It is warm there, because I have had the place fitted with hot-water pipes and turned it into a conservatory where I grow exotic plants. It struck me as singular that the dog should give no alarm if anybody were wandering about the house, and I went out to see if he were all right. I did not turn on the lights because I would not pander to my own weakness. Besides, I could find my way about the corridor blindfold. And then, in the darkness, I saw an amazing thing—a globe of flickering blue fire, about the size of a football. It moved in the most a extraordinary way, and at first I thought the floor was alight. But I abandoned that idea when I saw a long, lean arm thrust out and a brass cup held over the flame. Oh, I must tell you that before that I noticed a peculiar scent of the most strange and overpowering description. I thought that one of my new plants had come into bloom and that this was the perfume of it. Then I saw how mistaken I was, and that the odour arose from the brass cup over the flame. After that I recollect nothing else except that I became terribly drowsy and when I recovered I was in my own room with the door locked on the outside. I cannot tell you how thankful I was to hear your voice."

"It is very strange," Wilfrid said. "Obviously you did not go back to your room by yourself. Therefore, some one carried you there. I think you may make your mind easy as far as you are personally concerned. Whoever these mysterious individuals may be, they bear no enmity to you."

"Then whom do they want," Beatrice asked.

Wilfrid was silent for a moment. He could give a pretty clear answer to the question. But Beatrice was already terrified and troubled enough without the addition of further worry. Cotter's incoherent terror and his wild speech had given Wilfrid a clue to the motives which underlay this strange business.

"We will discuss that presently," he said. "In the meantime, it will be as well to find out why your dog did not give an alarm."

The black and white terrier lay on his mat silent. He did not move when Beatrice called. She darted forward and laid her hand upon the animal's coat. Then an indignant cry came from her lips.

"The poor thing is dead," she exclaimed. "Beyond doubt the dog has been poisoned by those fumes. And look at my flowers, the beautiful flowers upon which I spent so much time and attention. They might have been struck by lightning."

Wilfrid could see no flowers. Across the great west window was a brown tangled web hanging in shreds; in the big pots was a mass of blackened foliage. But there was nothing else to be seen.

"Do you mean to say these are your flowers?" Wilfrid asked.

"They were an hour ago," Beatrice said mournfully, "some of the rarest and most beautiful in the world. They have come from all parts of the globe. It is easy to see what has happened. Oh, please take me away. I shall be stifled if I remain. It is horrible!"

Beatrice was on the verge of hysteria. Her nerves had been tried too far. It was necessary to get her into the open air without delay. In his quick, masterful way Wilfrid took her by the arm and led her downstairs into the billiard-room. Beatrice was safe, however. It was plain the visitors had no designs against her; indeed, they had proved so much by their actions. And, unworthy as he was of assistance, something would have to be done to save Samuel Flower. Wilfrid would have to act for himself. He could expect no help from the terror-stricken Cotter who appeared to have vanished, and it would not be to prudent to arouse the servants. He took Beatrice across the billiard-room and motioned her into the open air.

"I will fetch a wrap for you," he said. "I shall find some in the hall."

"Am I to stay outside?" Beatrice asked.

"It will be better," Wilfrid said as he returned with a bundle of wraps. "At any rate, you will be in the fresh air. And now I want you to he brave and resolute. Don't forget that these mysterious strangers have no grudge against you. Try to bear that in mind. Keep it before you and think of nothing else. I believe I have a fair idea what is taking place."

"But yourself," Beatrice murmured. "I should never know a moment's happiness if anything happened to you. You have been so strong and kind that—that—"

The girl faltered and tears came into her eyes. She held out her hands impulsively and Wilfrid caught them in a tender grip. He forgot everything else for the moment.

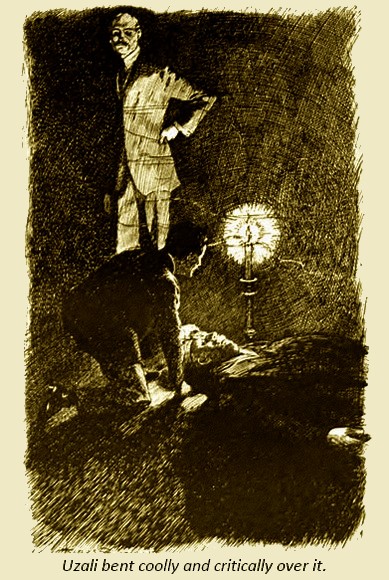

"For your sake as well as mine," he whispered. "And now I really must act. Unless I am mistaken it is your uncle who is in most danger."