a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Bring the Monkey Author: Miles Franklin * A Project Gutenberg Australia eBook * eBook No.: 0801301h.html Language: English Date first posted: November 2008 Date most recently updated: November 2008 Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

First published 1933 All the incidents in this book are imaginary and all the characters except Percy are fictitious.

I have always loathed murder. Once I took not the slightest interest in murder; cases. I never read even the most luridly head-lined nor the socially shocking. However, the Tattingwood case assaulted my interest, and has forced me to wonder how many other women or men may have killed someone, and escaped detection, or even suspicion: or alternatively, how many may have been wrongfully suspected, accused, or even convicted of murder.

But I loathe murder more than ever, as revolting, stupid, bestial, unnecessary.

To employ Zarl Osterley's locution, it carries a fiendish thing altogether too far.

It all happened through Zarl Osterley's monkey, Percy Macacus Rhesus y Osterley. Until Zarl took the notion to acquire him I had as little interest in monkeys as in murder. There are no monkeys in my native land, except in Zoos, and these had always seemed to me as too repellently like depraved editions of ourselves. Their mournful mien depressed me. But one day when Zarl was restless through being baulked of an Everest expedition, she said "Let's have a monkey!"

"Where would you keep the brute?" I inquired perfunctorily.

"Here, of course! With us!"

Zarl occupied a flat in a studio building in St John's Wood, London, and I spent much time with her.

"A wart hog would be ever so much more convenient and beautiful," I responded, continuing to read Julian Huxley.

"But I thought you loved animals?!!!"

"All but monkeys: and I don't love any animals in the bread crock, and on the pillows, as they must be in these town places. Animals and cleanliness can't be together in a flat!"

"But we could train a monkey to do anything."

"You'd have to hire someone to look after the beast."

This seemed final. We were in such low water that we could not even hire a char.

No more was said on the subject for a week, then Zarl remarked "I had an offer of a monkey to-day: he was a bit too big, but lovely. I'll never rest now till I have one."

I turned and looked at her--this time over a book by Osbert Sitwell. Zarl resembles a champagne glass, not alone in grace of fashioning, but in effervescent contents. The bubbles are intensely fascinating. "Surely you are not in earnest about a monkey?"

"I must have something. This is dreadful--just going to bed and getting up again--without seeing the sun rise on Kangchenjunga, or the ice break on the Lena."

"I should have thought you had enough of the sleet on the desolate bays of the Beagle Channel when you went to the Horn."

"Oh, I've forgotten that long ago. I'm going to concentrate now on going to the Lena or the Indigirka, and I must have a monkey to keep me from doddering into a complete stodge."

"A monkey would hasten that," I contended. "You've seen those old women with poodles--can't tell the women from the poodles--pathetic derelicts--ugh! A monkey would do that for you--only more so."

"A monkey would be a symbol and a promise."

"A sure promise of wrecking everything in the place, and think of the SMELL!!!"

"I never heard that monkeys smell!"

"Then you must have been very deaf in the Zoo."

"But I'd only have one."

I had visions of Zarl's establishment degenerating into a kennel. Zarl is not a Martha among housewives. That is one of her great charms; one can live with her without ceaseless petty persecution. A London interior becomes sufficiently trying with a cat or dog--but a monkey! Goodbye to our pleasant association. I comforted myself by thinking that the monkey would never materialise.

But a week later Zarl came bubbling in. "I've got a monkey!"

"Where? How? What!"

"Jimmy Wengham brought five back in an aeroplane from Africa, but only one has lived, and he has kept it for me. Someone has it somewhere, and I'm going there to get it. It will be too marvellously thrilling. 'Wizard! Eh, what?' as Jimmy says."

I took a farewell glance around the fine room with its comfortable chairs, reflected that all things bright and fair are fleeting, and retreated to my own lair. But next day, as I was descending, Zarl was ascending my stairs.

"Look! I thought you'd like to see Percy--my monkey. I've had a terrible time with him. He's bitten me, and I could never confess how many things he has broken. I don't think he has been kindly treated. He has a great scar on his leg--poor little cow."

I beheld a creature the size of a half-grown kitten, only more slender, an appealing, shrinking mite that tried to creep out of sight under Zarl's furs. He shuddered and showed his teeth in a piteous grin, as if I were a big baboon that would demolish him. I can never resist any animal, even the so-called human ones, if they appear distressful, and I took this poor little soul in my arms and attempted to stroke his fur, but he shivered through every fibre at the slightest touch, and looked so woebegone that I was instantaneously and permanently enslaved.

"He's behaving very well with you," remarked Zarl. "Would you like to keep him all night? I've got a chance to be motored up to Cambridge for the week-end, and there is a professor there who might like to go down the Lena to the Arctic Sea for the goose-plucking, and to see that thinga-me-bob bird; and Percy might get in the way at the wrong moment."

I was committed to Percy for one night, for two, for three. We were left to make acquaintance as best we would. I washed all his human hands and face, and he enjoyed dabbling in the warm water and grabbing the soap. I made him clean and sweet, settled the matter of loin cloths after the fashion of Mahatma Gandhi, gave him a cup of milk to hold in his own tiny hands, got him a blanket and box, tethered him to the leg of my bed, and retired.

I peeped up now and again to see if he were there, to savour the delight of such a guest. And every time I peeped, he would be peeping too, to see what I intended. It was so amusing that I laughed aloud, cheered and entertained. Never since my teens, in the joy of new kittens, or a baby koala, or an echidna, had I felt such pleasure.

In the morning he came to bed to be cuddled, a warm delicately-fashioned little thing of sensitive texture. How ignorant I had been to think of a monkey only as ugly or evil-smelling! Here were beauty and grace to nourish the aesthetic appetite.

In the days that followed, Percy settled in. I had been thoroughly grounded by my mother in the ethics of pets. She always said, "Unless you are willing to do everything for either a child or an animal, you do not really love it; you only love yourself and the sensuous pleasure to be derived from it." The world is full of the less thorough kind of lovers. There is little competition on the other plane, so Percy quickly developed into a personality, with me as a coolie on the end of his string. A flatette was vacated in Zarl's building and I moved there to be near him. We devoted ourselves to making him happy, and to surrounding him with that affection said to be necessary for the flowering of a monkey's genius. This was due to one exiled from his own sunny country to make a toy for people who should have known better. He devoured as much time as cross-word puzzles or bridge--more than we could afford--and was an expensive luxury for hard-working women; but in an age of people rendered superfluous by machines, the teeth were drawn from the rebuke that we would have been better employed as mothers dragging up infants to degenerate in uselessness.

Fulminations against a mischievous, unfaithful, troublesome invention of sheer pestiferation collapsed. Percy had only to dance before us, or to hold out a confiding hand, to break loose and jump into bed with us, or cry if we left him alone, and our hearts were softened.

In the way of sirens of either sex and of any size or shape he was irresistible--a continual nuisance and a perpetual delight. He was a "wow" in several sets, a favourite in the Parks and on many buses and in the Underground. To his popularity and my infatuation can be attributed my connection with what is here recorded.

Through the evidence and gossip that surrounded the case, by information gleaned from an articulate police official, by deduction and inference--without which any chronicler is a dunce--there was no difficulty in reconstructing the procedure preliminary to Lady Tattingwood's party.

The impending week-end at Tattingwood Hall was noted by the Yard. After the years of comparative freedom from robberies upon jewel owners, which had followed the smashing of Cammi Grizard's and Leiser Guttwirth's gangs just before the war, there had been recently a recrudescence of such depredations. It looked as if the lesser gangs which had been disrupted in the late twenties, by the arrest and conviction of the master spirits, were attempting re-organisation around new leaders.

The tactics of Ydonea Zaltuffrie, the dazzling film star, were such as to generate independent burglarious activities. Her press agent's concoctions raved through the press with such virulence that the police had had to disperse the traffic outside the Ritz. The credulous were doped by the news that she was so startlingly beautiful that she ravaged the hearts of princes and rajahs, as well as those of talking-picture fanatics. She was now about to lay waste the remnants of the English aristocracy. She was to open her campaign in one of the few remaining country houses, where the Hon. Cedd Ingwald Swithwulf Spillbeans, second son of the family, had taken to films as a career. They allured him as a more pulsating adventure than that followed by his elder brother St. Erconwald, in securing, without any thrills or frills, a nice tame heiress, who had risen to the demands of primogeniture by producing two male infants.

Owing to post-war taxes and the rising cost of living in every direction, the Baron himself was threadbare. Tattingwood Hall had become a devouring monster that put him on the rack. Keep it up as of yore, he could not; give it up he would not--not even to his son to evade death duties. It was his life, his love, his religion, his hobby. His second wife had been chosen for the sake of Tattingwood--a Miss Clarice Lesserman. (Soap.) She had invested in Lord Tattingwood some ten years before I met her, for the glamour of the title, and as a bulwark against a war-time infatuation for a man many years her junior. Now mergers, rationalisation and other humorosities of business efficiency were deflating her suds and paralysing her products far below the needs of Tattingwood Hall.

She had no declared children of her own, so was comfortably assimilated by her step-sons, and she welcomed the distractions of the younger's film enterprises.

This week-end was the apex of opportunity towards which Cedd had been diligently working for months. To have captured the fabulous Ydonea Zaltuffrie, in itself was achievement, and the idea was to involve her to the extent of starring in a film story which Cedd had gathered together without the interference of an author. Cedd hoped to direct it. He was even prepared to marry Ydonea for a spell, should art or career demand such lengths. That she might be too independent to marry him, he was not quite Over-Seas or post-war enough to grasp.

Lady Tattingwood had become friends with Zarl Osterley on Mount Cook or Lake Taupo, where she had gone to get a little fresh air, being that way inclined, and where Zarl had lent her some safety-pins in emergency. Lady Tattingwood had been there for fresh air, it has been suggested, and Zarl was taking a little exercise, because one of her fortes is to be secretary to some great man or another on hegiras to the ends of the earth to meditate upon the past history or to inspect the present private life of some bug or weed. This gave her an intimate nook in many different cliques.

Lady Tattingwood was uneasy about the Ali Baba trove of jewels advertised in connection with her film star guest, who wore them with a nonchalance becoming to beads from Woolworth's. There was no telling whom they might attract to the village, so Lady Tattingwood had a heart-to-heart talk with the local police. Lord Tattingwood sent a peremptory message to New Scotland Yard. This was considered by the right official and passed on to Chief Inspector Stopworth.

The Yard had earlier been consulted by Miss Zaltuffrie's Grand Vizier, with the result that a Yard officer was to reinforce the lady's private detective force.

The Chief Inspector, or Captain Stopworth, as he was more familiarly known to his friends, considered the police aspects of Miss Zaltuffrie's advent. Her pictures met him on every illustrated page, and some of them were remarkable. It was not her beauty however, but her jewels that interested Captain Stopworth. It was rumoured that the heir to the Maharajah of Bong or Bogwallah, or some such marvellous or mythical principality, had gone mad about Ydonea in Paris. The press freely stated that he had given her stupendous State Jewels, but probably there was exaggeration in the interests of a commercial headline or two.

Captain Stopworth had plenty of salt to sprinkle on such "publicity," to keep down mortification, but he carefully extracted the grains of news, and re-read Lord Tattingwood's demand. He then put through a call to Supersnoring and requested the Butler to bring Lady Tattingwood to the telephone. When he had established his identity, the Inspector asked her ladyship to inform her husband that there would be a sergeant and constable in his service from Saturday night till Monday morning; and then his tone changed.

"I have not seen you for a long time, old girl."

"Whose fault is that?"

"Well, have you a spare bed for this week-end? I could kill two birds--from Saturday afternoon till Sunday after dinner."

"Yes, oh, my dear, do come, and bring what we spoke of. It will be safer. I'll explain when you are here."

"All right. I'll see you some time during the next forty-eight hours--privately I mean: au revoir."

He replaced the instrument and tattoed a tune on his desk for a few moments while sunk in thought. He then touched a buzzer and a smart young officer came in. Calls to the Ritz Hotel and the Mayfair Police Station were then put through, and there were conferences. Eventually Captain Stopworth informed Detective-Constable Manning that he would proceed to Tattingwood Hall for the week-end in the role of valet, while Detective-Sergeant Beeton was to have the privilege of being present to see Cedd Spillbeans' film, he supposedly being interested in sport and the allied arts.

"It's getting to be a pretty pass with me to be invited for that!" exclaimed Zarl with humorous petulance as she stood before the long mirror and arranged a delectable copper-tinted curl on her forehead. She refers to herself as ginger, but that is affectation. Her hair is that incredible shade that shames a new penny, and challenges amour. It matches the little dancing flecks in her soft round eyes.

She tossed a letter on stationery embossed TATTINGWOOD HALL, SUPERSNORING, with a telephone exchange in the Home Counties.

My darling Zarl,

Do come for the week-end, and bring the Monkey. Ydonea Zaltuffrie is to be here, and if Cedd's machinations hang fire, what am I to do with such a white elephant? She is dripping in beauty and "it" and dresses mostly in jewels, given her by some Indian Prince whose name is never mentioned for fear of making things worse in India. So Swithwulf has dubbed him the Rajah of Bogwallah for convenience. Do. This is a genuine S.O.S. Besides, I'm dying to make his acquaintance. Swithwulf has called in Scotland Yard because of the jewels. Jimmy Wengham is to be here too. Don't fail me. Clarice.

"Did you ever I must be degenerating into a sorry old tart-like an organ-grinder invited to bringa-da-monk to entertain a flicker doll with goggle eyes, who registers the lowest paroxysms of osculation as a substitute for witchery every time some Buffalo Bill whiffles through a megaphone."

"I shouldn't mind being considered a tart with a tom cat, or I'd even be civil to one of those goggle-eyed frowsy Pekes to gain admittance to so marvellous a menagerie. I begrudge Percy Macacus Rhesus y Osterley, he is all that has stood between me and jumping-off this last week."

I was spread in a deep chair, my feet to the fire with Percy on my chest under my oldest woolly jersey, fast asleep. The lovable face showed complete abandon, the closed eyelids were an eggshell blue that left those of the painted ladies mere "mucky pups."

"You come too. I'll wire Clarice. She'll be delighted. She's a kind old pillow."

"I've just refused the party at Buckhurst because I cannot afford the tips in those private pubs--prefer the regular inns; besides, I've only got one evening gown spry enough."

"I haven't a stitch either; and imagine me in evening dress with Percy! He'd pluck every feather off me, and leave bleeding weals on my most important promontories. The odious little cow never cares a hoot about the side his bread is buttered, and favours all the wrong people. He'll most likely go for old Swith's nose."

"He evidently knows how to annex a faithful coolie," I said, tilting his chin the better to adore him. He made little guffing sounds of protest against being disturbed, and crawled farther under my jersey.

"He really is consistent about you. It makes me think he must have some character or intellect. If you won't come with me, come with Percy to Tattingwood Hall."

"I've got an idea! I'll go as your maid in overalls, to take care of Percy. I shall be saved from the woofits, and you'll help Lady Tattingwood to offset Ydonea. My new dress will be free for your use too."

"Don't be a peanut! What an entertaining but utterly impossible idea--some one there might know you."

"No. When I ascend to society, it is to a much more political sociological clique who do good to humanity; also I'll be disguised in a uniform. Who ever looks at a maid at one of those jamborees--plenty of hunting higher up. If I wanted to commit a crime, I'd take Percy, and then everyone would be looking at him and fail to see me. Yes, let's rival Ydonea!"

"Why should I waste my fleeting moments on the oddments that infest Clarice--not one of them could be excited to go as far as the Murrumbidgee, let alone the Indigirka or Lena."

"What about Jimmy Wengham? I see in the papers that he is the pilot of Ydonea's aircraft--going to fly to glory. I should think he might be useful for your expedition."

"Aaaahhhh! Has she swallowed Jimmy? I might induce regurgitation, just to see."

We telephoned a telegram:

DELIGHTED BRINGING MONKEY AND MAID SATURDAY FOUR O'CLOCK ZARL

We were in the midst of our preparations when Lady Tattingwood's reply came:

AFRAID NO ROOM FOR MAID HOUSE FULL SORRY LOVE CLARICE

"Well then, it's off, and I contribute Jimmy to Ydonea's bag," said Zarl. "And I'm glad, as I'd much rather do something quietly with you. Please send another telegram."

Unselfishness is one of the prominent ingredients of Zarl's seductiveness. She was obviously planning to keep me from melancholia during the weekend, because I had lately been knocked into a cocked hat, but I did not want to burden her unduly. I went to the telephone and sent another message:

MAID THOROUGHLY RESPECTABLE GIVE HER MATTRESS IN MY ROOM NECESSARY FOR MONKEY ZARL

"There, you must live up to me now. Percy will be an opening for me to be in the whole shoot, above stairs and below--a two-ring comedy."

I hauled Percy from a picture rail, where he was investigating an electric wire, and lashed him to a divan leg, where he began to shred the valance with perfect good-will and gentlemanliness.

It was a clammy day towards the end of the year with enough roke to close it early, and a good many of the guests were assembled in the great hall when Zarl entered a few minutes past four o'clock. We had arrived at Supersnoring by train, where Lady Tattingwood's motor was awaiting us and two other unclassified guests. Zarl attended to our suitcases while I nursed Percy. His weight was six pounds but his energy made it seem like fifteen, and his resourcefulness and perseverance in employing it were an object lesson to the discouraged. And he can reach as far--well, he can simply reach, and reach, and reach till he gets there. Zarl had to be protected from him till the right moment, or she might arrive with the air of one of those frumps in employment agencies waiting for jobs that always pass them by. I was provided with overalls and a bag of tricks such as a mother takes abroad with a young infant. Percy's wardrobe was extensive.

It is worth going to Tattingwood in any capacity to see the lovely old place crowning the Park as one approaches by the long, sunken drive. To halt under the arch of the tower and turn to the left up the imposing steps that lead to the big chamber called 'the hall' is sheer adventure. The noble beauty of these old places goes to my head.

At the right moment Zarl tucked Percy under her arm with a Judo clasp, that has proved successful, and made an effective entrance. Percy was the right shade to go with her trim coat and skirt, and peeped most endearingly from her fabulous furs, that came straight from Alaska or some such place, I was alert lest he should destroy them; on another occasion he had chewed the head off a mink stole while Zarl was engaged in conversation. He had been too good to be harmless.

Lady Tattingwood, a colourless but unmistakably kind looking woman, like a patroness of suburban charities or the Women's Institutes, welcomed us all three with eager cordiality, and drew us towards one of the two great fires with which the hall was enlivened. Percy creates a diversion in any society, so interesting are animals, but he was a godsend to a company that needed dancing, bridge, gramophone, radio, billiards or something like that to make up for the dearth of inner resources all the time that amour was not on draft.

An elephant hunter from the Congo was presented to Zarl, and with him was Jimmy Wengham, late R.A.F. I pulled my cap lower lest Jimmy may have remembered seeing me at Zarl's one evening. He was an exceedingly tall dark dissipated-looking young man, and had a name for general as well as aerial recklessness. He had retreated from the Air Force because he had used one of the Government planes for his own excursions.

He and the Elephant Hunter had been engaged in throwing knives into a board set up as a target across a corner. Jimmy informed Zarl that the Elephant Hunter was at present in the lead, as he had the more patience. The Elephant Hunter was another very tall man, by name, Brodribb, stolid and with eyes of elephant grey--protective colouration perhaps--which may have been excellent for sighting big game, but had a disconcertingly static stare for a house party.

Lord Tattingwood entered with a curious weapon about the size of a dirk, but more the shape of a rapier, as though a rapier with a small hilt had been cut down to nine or twelve inches, and filed very sharp.

He greeted Zarl, and poked his finger under Percy's neck, causing him to shudder and click irascibly. He said facetiously "Shall I do the little blighter in with this--it wouldn't be the first of his species. Seen dozens like him cut up to flavour the Zulus' soup in South Africa."

The knife throwers were tremendously interested in their host's unconventional weapon, which he said he had had since the Boer war. Both men immediately tried it on the board. Wengham was fascinated by the sport of throwing it to strike into the wood.

"By George! It could be a dangerous thing!" he exclaimed.

"It used to be when I was your age," admitted his host.

He was urged to try his skill now, but after wavering and twisting, the knife fell short from his hand and made a hole in one of the great rugs. "I've lost my nerve and judgment of distance," he said, turning to talk to Zarl. She left the young men to their sport, as we both have a horror of knives. Jimmy Wengham took no notice of Percy. He was engrossed in the new sport and had not a capacious mind. He had not given me a glance fortunately. Lord Tattingwood, on the contrary, fixed me with a steadfast glare.

Nothing but his height fitted the figure of Swithwulf George Cedd St. Erconwald Spillbeans to be the sixteenth Baron Tattingwood and Lord of that splendid pile. He was stooping, shabby and dull--a dowdy old man in the sixties. Disappointing. Zarl went the rounds, while I, thanks to Percy, stood by the door enjoying the promising comedy.

Ydonea Zaltuffrie was not in evidence. A number of the other women guests had also disappeared to put on something startling for the tea hour, which was approaching. Lady Tattingwood, placing her arm around Zarl affectionately, and again thanking her for coming and bringing "the dear little monkey," said she would go upstairs with her. In ordinary circumstances I should have been drafted off to the lower regions, but Zarl transferred the monkey to my arms and said "Come along with him now."

"Yes," confirmed Lady Tattingwood, "Come with us now."

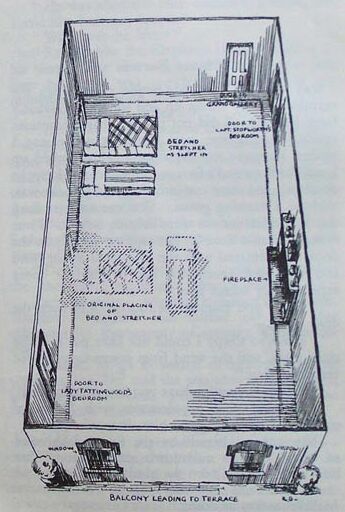

We ascended the grand main staircase and turned to the left. Lady Tattingwood's apartments were in a corner which faced the Park on one side. We were put into a large room adjoining. It had been occupied by Lord Tattingwood during his first marriage, but he now occupied a suite in the east wing. There was rather a large bed, and, placed at the foot of it, was a stretcher. Zarl's quarters were a menage a trois by reason of Percy and me. Lady Tattingwood apologised that she had had to give the dressing-room on the other side to Captain Stopworth at the last moment.

"I am so sorry to have turned him out," said Zarl, "But you brought it on yourself."

"It is he who has cramped your quarters," she replied. "But with the Maharajah's jewels plastered on Miss Zaltuffrie, instead of an idol that could be locked up, I had to have protection. Such a relief to turn the supervision of safety over to Captain Stopworth. It leaves me free to help Cedd with his film fortunes."

Zarl chaffed her friend in low tones; and discussed Jimmy Wengham. When he had crashed out of his Commission in the R.A.F. owing to the abduction of a sacred war machine for a commercial stunt, Jimmy had distinguished himself by one of the first flights to South Africa in company with a titled air woman, who became desperately enamoured of him. Jimmy however was infatuated with Zarl at that date, to the extent of lugging home a family of monkeys. His present idea was to stunt in films and thus collect funds for a record world flight. He had quite smartly got himself elected as pilot of Ydonea's new Puss Moth and was spreading himself as a prominent member of the star's retinue. Ydonea had her eye on his publicity possibilities and for the moment tolerated his standardised amorous cacklings.

While Zarl and her hostess talked, I opened the suitcases and made pretentious play for my mistress pro tern, by laying out the gorgeous pyjamas which were reserved for show and creating envy. Also laid out for her was my one smart new evening gown.

"Don't leave any of the windows open on to the terraces," warned Clarice, "We must guard against entrances for suspicious characters that may be attracted by the jewels."

"It is too thrilling for reality to have the famous Capt. Stopworth right next door to us," said Zarl.

"Hurry down and help us through tea," said her hostess. "And bring Percy, too. Dear wee creature, I am so proud that he has come to spend a week-end with me, and hope he will be happy."

"He will be, but I don't know about you, by the time you'll be finished with him," laughed Zarl.

As soon as Clarice left us we moored Percy to the big coal scuttle into which we piled a door weight and other unchewable articles. The scuttle was put in a clear space near the foot of the bed and Percy given a short leash. In his search for insects and the establishment of hygiene, which was a major business with the little fellow, we hoped he would not pull the pattern out of the carpet, or reach and reach in his elastic capacity till he shredded the bed clothes or pulled over the dressing table.

I plastered myself with a brunette cosmetic that made me resemble an American Indian. Over a brown gown I wore a smart orange apron, and around my short crisp locks wrapped an orange bandeau to match the apron. "An accent will heighten your importance," I said to Zarl. My sporting instinct stirred to outplay Ydonea Zaltuffrie's maid, no matter what she might be.

"Don't be too ambitious, or I may crack in trying to live up to you."

Zarl had an arresting suit of lounge pyjamas for tea, in electric light exactly the colour of her hair. It had been lent to us out of stock for this prank by our friend Mabelle. (Madame Mabelle, Exclusive Gowns, Loane Street, Knightsbridge, where Zarl at that time had a post).

Zarl was to depend upon the monkey for distinctive decor. We couldn't risk his chewing up a forty guinea garment, which was worth at least fifteen guineas on its merits, and Percy quite innocently could leave disreputable hieroglyphs on bosom or cheek, as he struggled towards one for refuge. Therefore where the monkey was, I had to be also, a gilt-edged scheme to be in all the fun without the burden of being entertaining, or having to appear in evening uniform, like a plucked fowl in an ice box; and so inexpensive, compared with being a guest.

Percy had the most adorable little knitted singlet and brown velvet shorts, and sported a strong new lead. All his four hands were cleanly washed in warm water and scented soap, and his nose was powdered. He loved to participate in Zarl's toilette secrets, which were very simple, and no secrets at all. The entertaining little beggar added just the requisite touch of unusuality to Zarl, who generally conquered the wariest by her natural delight in the passing hour. She was stimulated by the prospect of Ydonea, and went down the stairs with a mischievous champagne-bubble expression in her eyes, and the lights making mocking fires in her curls.

Her entry was not to be jeopardised by precipitancy, and while we had been waiting she informed me that during the war, Tattingwood Hall had been lent as a hospital for officers, and Clarice Lesserman had worked there as a V.A.D. Thus had she met her future husband, and also a handsome young second lieutenant, Cecil Stopworth. Away out on the shores of Lake Taupo, Lady Tattingwood had told some of her story to Zarl--the more romantic parts, her tongue loosened to sentimental reminiscence by the inebriating New Zealand moonlight. Lady Tattingwood's friends--so-called--had told Zarl other facets of the affair later.

Glamorous days for Clarice, aging and disillusioned, to look back upon, days when she had nearly run away with the handsome boy, son of an impoverished Indian Civil Servant, whose University career had been interrupted to join up. She had been saved on the brink of folly because whispering tongues insisted upon the fact that she was twelve years her lover's senior, and rich, very rich, and the war was making her much richer, while he would have to depend on his own exertions. Some people, who meant well, put old Lesserman on the trail. Others had suggested that Stopworth was a caddish fortune hunter.

In the antipodean moonlight Clarice confessed to Zarl her regrets that she had not risked all, because Cecil Stopworth's name had never from that day onward been connected with other women. His affection might have been that one example in a million of lasting romance, despite disparity in age and fortune.

The not very serious wounds that had taken Stopworth to Tattingwood Military Hospital, were all that he suffered in the war. He rose to be a Captain, won the Military Cross, and in due order was demobilised and thrown on his own resources. To return to the University was impossible. He had not the means, and had lost the urge. His father had died and his mother was reduced to a small pension. He had the experience of many other young men following the war, and in desperation filed an application, and was accepted as a member of the Police Force.

He had been too proud to permit Clarice Lesserman to sacrifice herself by eloping with him.

In the Force he found work that he liked, and when practicable made application for removal to the Criminal Investigation Department, where he quickly attracted attention. His rise was rapid owing to his successful solution of several criminal mysteries. He came of a good family, and, as the years passed, he renewed his acquaintance with Lady Tattingwood. As he had simple tastes and remained a bachelor, his salary was sufficient for his needs, and he was sometimes to be seen at other week-ends too. It was predicted that he would one day be Commissioner. He was well-suited to his post and seemed to have no interests outside it. With his splendid good looks, charming manners and ability he could easily have advanced himself by marriage, but women were not one of his weaknesses. No one believed that he had a throb of anything but friendship for Clarice, because she looked her years without subterfuge, but the lamp that she had lighted for him was still burning. She was fortunate beyond the dreams of most women that he never humiliated her by affairs with other women, at least none that were known to her circle.

She was now fifty-one or -two, and Captain Stopworth in the last of his thirties. I was glad that the hero of this interesting romance was to be quartered almost with us.

There had been no romance in the second marriage of Tattingwood to Clarice Lesserman. Everyone knew it for what it was. The lady, when forty, had contributed her fortune to the support of Tattingwood Hall in return for position and name. It served as well as most unions, and vas a splendid investment for many of those who depended on week-ends. Tattingwood liked to dispense hospitality in the pre-war way, and Clarice was so kind and unforceful that she never made anyone unhappy.

Zarl assured me that Lord Tattingwood had not always been the frump of to-day. His life had been full of romance. His father was only second cousin of the Fifteenth Baron, and Swithwulf had been designed for the Church. He had escaped this for the army, and had his chance in the Boer war, from which he returned a hero with the V.C. He had been invited by his elderly cousin to stay with the son and heir, a quiet soul addicted to the laboratory, and with no taste for being a landed gentleman. He looked forward with regret to stepping into his father's shoes, whereas Swithwulf would have sold his soul to possess the old place. It was a passion with him. A great horseman, a crack shot, a champion at games, he was a popular figure. People said it was a pity that he could not change with the heir, to whom hunting and similar pursuits were a burden. When it happened that the young man accidentally shot himself and Swithwulf reigned in his stead, all seemed as it should have been.

My head was full of the story as I went down to tea in the wake of Zarl with Percy in my arms. We could not allow him to be near the lounge suite. He had had a good snooze in the train and was far from a cuddly mood, alert to leap in all directions like a crab propelled by a Jennie wink. He was so beyond reason that I put him down, whereupon he descended the stairs with dignity. He liked Tattingwood Hall as much as I did, and probably for analogous reasons. Its spaciousness suggested our native habitats. He slid forward utterly silent, with an electric ease approaching that of fish in water. Arrived amid the company, all eyes were his, as always, wherever he appeared in whatever society.

Zarl's status was quite well upheld by her maid's smart uniform, and, with the addition of Percy, it would be difficult for any other maid to be more special. Zarl was so bewitching in her modish garments and astonishing curls that it would take a transcendent film star to eclipse her.

Cedd Spillbeans came towards her. "Hello! Why this organ-grinder monkey motley touch?"

"I'm so broke that I hope you'll cross Percy's hand with silver."

At this, Jimmy Wengham, who was still practising with the dirk in the corner, desisted, and exclaimed "Surely that's not the stinkin' little blighter I brought over in the old Haviland."

"No one ever knew Zarl so long faithful to any male," said young Spillbeans.

"Do you mean the monkey or me?" demanded Wengham.

On beholding the company, Percy bolted to my arms and showed his teeth in a grin that was merely nervous, but which to the uninitiated looked vicious. One affected lady of mature years, in the dress of a flapper, made a fuss of 'the dear little darling' and wanted to clasp him to her attenuated frame, but a monkey is not that kind of cat. Percy threw himself about and attempted to smack the lady.

"Spiteful little creature," she hissed, and turned to the company. "Monkeys are dangerous things. You never can trust them, Never! I know of awful cases of accidents with them. He's just a common little monkey, isn't he?"

"I wish the little cow would understand which side his bread is buttered," whispered Zarl to me.

"He's going to, this evening," I whispered in return.

He was not at all attracted to the company filling the hall. He clutched me tight and tried to climb inside my dress. At the approach of Wengham he screeched and fluffed out his fur and became a fierce beast in miniature.

"Hal Ha! Jimmy," exclaimed Zarl. "What did you do to him when you were travelling together?"

Everyone laughed, to the discomfiture of Jimmy.

"I had to keep the little blighters in order. You're only a little mongrel, not worth the trouble you were," he said, tickling Percy under the chin. "Say Zarl, will you let me take a shot at him at twenty paces with this knife. Just for practice!"

"He notta lika you," I murmured, gathering Percy to me.

"The little fellow feels instinctively that you are one of those horrid blood sports creatures," said Zarl.

He settled down somewhat, but peeped entertainingly at his enemy, raising his fur. To divert him I set him before a long mirror, and much to the glee of the company he danced for the fellow monkey that he saw in its depths.

"Say Zarl," called Jimmy, "Don't you want to come with me on a world flight, and bring the monkey for a mascot? It would be simply coloss!"

"It would be colossical! When do we start?" demanded Zarl, the champagne bubbles rising, and her sudden interest in Jimmy going to his head.

"Just as soon as I gather the beans. If you and the monkey could charm some fat-necked millionaire into providing a machine--a Puss Moth like Miss Zaltuffrie's."

"What is the matter with Miss Zaltuffrie's?"

"Now that's a wizard idea! I've got everything wrapped up except money. The thing is to get away ahead of the crowd! It's a damned pity you aren't an heiress, Zarl!"

"I find it an inconvenience myself, but the inevitable fate of heiresses consoles me." She could have been thinking of her hostess as her host shambled about.

"The competition is awful when the heiress isn't," admitted Jimmy, "but I must get money somewhere, even if I turn burglar."

"Your state of mind should be reported to Captain Stopworth," said Zarl, as a gentleman entered from the stairway. He came straight to Percy. So this was the famous Chief Inspector! He had the touch that goes with love of animals. Percy looked steadily up at him from his pretty brown eyes so beautifully set in the dearest or little faces, and offered a tiny hand. He took the Captain's thumb in his mouth, and next tried to chew a button off his coat.

"What a success he would be on the films," the Inspector remarked, and strolled over to help his hostess with the placing of the tea trays. Her eyes lighted at his approach. It would be much more difficult to be sure of the state of the handsome Captain's emotions.

"What should be reported to me?" he inquired lightly.

"Only that Jimmy says he would do anything for money, and so should I, if I had an easy chance."

"Go on the films," recommended the gentleman.

"It would be as easy to win the Hospital Sweep," said Zarl.

The tea was cooling as the air grew heavier with the imminence of Ydonea Zaltuffrie. All the social members of her retinue were suitably disposed about the interior, among them, her mother, a plain woman from the Middle-West who stuck to her plain name of Mrs. Burden. She was called Mrs. Zaltuffrie, but more generally "Mommer." Ydonea so patently capitalised the universal mother complex that Mommer Zaltuffrie was suspected of being a hard-fisted and -headed non-relative hired to play the sentimental part. Managers, directors or such potentates of the industry stood about and made standardised pronouncements on the beauty and cleverness of Miss Zaltuffrie, or emitted spontaneous "best bets" or "wise-cracks" as to what would relieve the slump in the trade. One had one dearth of idea, and one another, but they were generally agreed that the total elimination of the author would be a tremendous advance. One little man evidently had a place in the industry as commanding as his proboscis. "An imposing thing carried altogether too far," as Zarl described it. It was likewise bearded within, which thickened his accent. "Not an accent, the honk of a siren, yet not a siren," again to quote Zarl.

"Authors," said this gentleman, "Are the bummest lot of cranks I have ever been up against. Why the heck they aren't content to beat it once they get a price for their stuff, gets my goat."

"I'll say you've thrown off a mouthful there," agreed his companion. "They are egotistical and jealous as cats. What surprises me about them--or it don't surprise me no longer--is that they can't say anything interesting to me."

There was ready agreement that authors were a wanton tax on any industry, whether publishing, drama or pictures.

"Then why have them at all?" interposed Zarl.

"The public has kinda gotta complex about authors. It's an old sooperstition hard to banish. They think you gotta have a big author; and the bigger they are the deader they are above the neck."

"They're just the dumbest things," said another.

"Perhaps if you lent them your megaphones they could be noisier," suggested Zarl.

"They sure need something," agreed the honk from the bearded beak. "You can wear your life away making them known and then they think you are trying to rob them. If you use a few of their little wise cracks..."

"It might be a colossically new idea to crack your own wisdom," interpolated Zarl, "and teach the cows a lesson." She was so enchantingly demure that Cedd Spillbeans came to the rescue of his guests.

"I understand your point of view," he said suavely. "That is why I want you to see my film--one reason. It has been assembled by experts in the industry, not written by some wayward outsider."

"Oh, Boy! You've said something there. That's what put it across with me."

"Yeah! Me too! Right away when I asked who was the author and you said you had given those old guys the go by..."

The cue for Ydonea's entry interrupted this speaker, a virtuoso with a formidable cigar that lolled upon his lips like a German sausage sustained by miraculous levitation. The million dollar beauty was coming, in the part of enchanted fairy princess. Her aureole of hair was palest gold, commercialised as platinum--still more costly. She was a pioneer in this innovation. It suggested ethereality as she descended with the light from a great glass chandelier upon it. The first sight of such fresh young beauty was breath-taking. Her form was tall and lily slender, but voluptuous--no skinniness--supple as an oriental dancer's. Her nose was perfect in bridge and nostrils, her eyebrows dark, her lashes long. She had one of those mouths so obligingly patterned that she had only to part the bowed lips to make a smile to cheer a photographer. She wore her nails long and claw-like and bright rose. Her eyes matched her mouth and nose in beauty. They were large and meltingly brown--like Percy's. There was no nerviness to give them exotic meaning. Her laughter was not the kind that puts wrinkles at the top of the cheeks, but no one would discern this while such beauty was so loudly advertised, at least no infatuated male creature. A sober woman remarking it would be suspected of envy.

She impersonated perfectly the exquisite unspotted maiden, with Mommer ever at hand as a fortification against fornication and other vulgarities ancient and modern. She was attired with that utter simplicity attainable by none but famous couturiers regardless of expense, and had no jewel or ornament upon her person. No silks or velvets for afternoon tea, but some mythical stuff, like sunkist ivory sea foam against a cliff, frothed down the dark stairs. Her man secretary, a young Englishman with a public school "man-nah," who had been engaged for decorative purposes, carried her billowing train, while her rousing utilitarian American woman secretary came behind him and kept a managerial eye on the tableau. When Ydonea halted, her mother rose and fluffed out her train around her with a few finishing touches as to a little girl going to a party. These endearments were advertised as too sweet and cute for anything in middleclass minded society, but were critically received by the assembled hard-bitten fox-hunters and poor relations.

"Oh, a dear 'cute little monkey!" exclaimed Ydonea, declining tea and coming towards Percy.

Miss Bitcalf-Spillbeans, whom Percy had rebuffed earlier in the evening, hastened to say that monkeys were never safe, never. Secretaries and Mommer advised Ydonea to be careful, but she liked the long mirror as much as did Percy, and came on.

Percy had been prepared by a slender diet during twenty-four hours, as he is more amenable with an appetite than with a full tummy. I unostentatiously handed Ydonea a baked chestnut. For this bribe Percy ecstatically deserted me, being that way constituted morally. He sat in Ydonea's arms expertly tearing the hull off the dainty, emitting engaging grunts of satisfaction. Miss Zaltuffrie expressed her delight.

"Oh, boy! I don't know when I've had such a kick out of anything!"

When Percy had finished the chestnut he began to chaw a hole in the diaphanous sleeve of her gown and then to rend it right and left. He loved to tear rag. His new friend would not permit his pleasure to be curtailed. A lady who could command contracts for fifty thousand pounds at par was not obliged to be uneasy about her finery.

"It doesn't matter. He can have the whole thing to play with, the 'cute little darling. I just love him to death right away."

Miss Zaltuffrie must have a monkey forthwith. She could not understand why she had not thought of one before. "Why didn't I think of having a monkey?" she demanded of Zarl, who murmured disarmingly that it was easier to let others think.

"I must have one for my next picture. I'll have this one. Whose is he?" she demanded of me. I indicated Zarl, who was sitting on a pouff on the hearth rug smoking one of the Elephant Hunter's cigarettes, while Jimmy Wengham gazed down at her with a he-man craving inflaming his expression.

Ydonea again turned in that direction, clicking her fingers to draw attention. "Say, Miss, on the Turkish cushion, what do you want for your monkey?"

Zarl, if she heard, affected not to. She continued her jocular blandishments.

"Say, Miss Zaltuffrie is wanting you," said Jimmy, being in that lady's employ.

"Say, what do you want for your monkey?"

"Nothing at all, thank you. He has more than is good for him already." She turned back to Jimmy. "Everyone spoils him in public, and I get the backwash of it in private, and have to discipline him."

"Oh, Miss Thingamebob, I meant how much money will you take for him?" persisted Ydonea, raising her voice.

"One does not sell one's friends. Miss What-you-may-call-'em," said Zarl, turning to the Elephant Hunter.

The perspicacious laughed to their interiors, but Ydonea was good-tempered as well as thick-skinned and ignorant--an undefeatable combination with beauty added. It accounted for her height on the golden ladder of industry.

"Do you put the little blighter out in the kennels?" said Jimmy, to ease the air.

"Indeed, no!" replied Lady Tattingwood. "The dear wee fellow is an invited guest and has the room next to mine." She, an heiress, married for her soap substance, was delighted with Zarl's repartee. Zarl could toss off the things that Clarice herself would have liked to say.

Cedd, commercially in attendance, tactfully observed "I expect the acquisition of Percy will have to proceed like that of other stars. We could offer him a contract. Princes tout for them now."

Percy having wrecked a thousand dollar confection with the aplomb of the governing classes now complacently came to me.

"Do you go with the monkey?" inquired Ydonea.

"Oh, yes. I have come with da leetle fellow. Alway. Da leetle monk he crya without me. I da coolie on da piece of string. I love mooch da leetle Percy."

"Oh, Cedd, you must give her a contract too," exclaimed Ydonea, clapping her hands. "I'll say she's as 'cute as the monkey!"

"That's a wizard idea," approved Jimmy, coming forward. He began to eye me. His expression indicated a straining memory. To elude its capture I excused myself on the score of Percy's needs and made an inconspicuous escape.

Percy created equal excitement below stairs. He held court in a back corridor leading from the butler's offices to the servants' quarters. Even the butler took notice of him and was elated when Percy sparred playfully with him. Kitchen- and house-maids and others piled around as if he were a popular actor at the Chelsea Garden Party. In Ydonea's suite was an Indian with the form of him who 'trod the ling like a buck in spring,' whose legs were like water pipes painted white, and whose head was haughtily reared under a hefty turban of kalsomine green with a fan tail over the left ear. He had a coat of the same shade embroidered with golden leaves.

"Some rooster, ain't he?" whispered a housemaid. Nothing but the ballet skirts and war bonnet of a Highlander with a beard on his knees, and a burr in his beard proper could have rivalled so spectacular a retainer. He regarded Percy with aloof disdain. He had the features and expression of some ruler on an ancient coin.

This was Ydonea's chauffeur. The friendly housemaid informed me that he had been presented to her by the young Rajah of Bogwallhoop. (This was her version of the nick-name given him by her master). He had been commanded to watch over Ydonea and the precious jewels till recalled from that post by the boss Rajah himself. "And they say she can only keep the jewels while she remains pure. That's why she has to be so careful--her mother around her all die time, and kep' on ice so to speak. It ain't very modern, is it?"

"What you think--that a gooda plan?"

"All right while it pays, but a trifle dull. What do you think yourself?" She threw me a long knowing wink.

"You mean to be so pure, or so veree careful?" My sociological tendencies were interrupted by the cook, who shooed us all to our pursuits, and I was left with the chauffeur, whose real name was Gulam, but Yusuf will serve to identify him. Ydonea called all her Indian chauffeurs by that name, as some mistresses call the office of footman Jeames regardless of its incumbent. I retreated from Yusuf's distinguished presence, trying to recall a resemblance. It came suddenly. This imperial creature had sniffed beside me in the Reading Room of the British Museum. English fogs had evidently distressed him, and he had sniff-sniff-snuffle-sniffed till I wanted to shriek "Use your handkerchief!" His beauty had not reconciled me, for I had been reared to a complex that the proper use of handkerchiefs is indispensable good form.

Pooh! So the faithful and picturesque attendant presented by a potentate was probably a modest Indian student employing his week-end in earning a little extra money to pursue his studies! The Rajah and Maharajah were figments of Ydonea's publicity expert. Pooh! Yusuf's beauty and sniffs had attracted me, but he had not deigned me a glance so I walked past him now saying "Have you da handkerchief?"

He produced a shawl-like square of silk patterned as a tropic garden, smelling as the roses of yesterday.

"Da handkerchief for da use. This way, look!" I used a firm white one vigorously, and retreated with the parting shot "Da Engleesh not lika da people not blow da nose, when da nose need da blow."

I went victoriously to cultivate Mammy Lou, Ydonea's Negress maid. We began on a good level, she being exotic and personal maid to the great star, and I keeping up my end as foreign maid to a distinguished charmer with a popular monkey. Mammy Lou was a vast old darkey, genial and approachable as only Negresses can be. None of the flunkies could speak Italian, so the pidgin jargon I had assumed could not be questioned.

Mammy was probably an actress. She was a skilled publicity agent. She welcomed me. I babbled artlessly about Percy. Mammy as artfully babbled about Ydonea. She showed her Mistress's jewel safe. It was not very large or heavy, but was locked with a chain to a big wardrobe trunk. The trunk in its turn was locked with a chain to the bedstead. A burglar could not therefore pick up the safe and walk out with it without shattering the trunk and bedstead. It was at present guarded by a stout man who sat on a chair with a revolver near at hand. I wondered if he might be a gangster. A second member of Ydonea's staff was posted under the window, and a gentleman, who had persistently ambulant movements for a guest, was frequently to be seen in the gallery approaching the door.

Mammy whispered that these were Pinkerton gennelmen who always guarded Miss Ydonea's jewels. I suggested that the real stones were probably in some bank, but Mammy raised her hands in pious protest. "No, siree! I should say not. Miss Ydonea is the real genoowine article. If she says a thing, that thing sure is true."

I persisted that it was unnecessary to carry jewels about to private house parties in England. Mammy mounted a big draught farm high-horse. It did not matter what the folks did in these out of date old castles. Miss Ydonea had better ideas. She always wore her grand jewels on Saturday night. What was the use of spending all that money on jewels if they were not to be seen and used. Miss Ydonea believed in spreading the sunshine, not in gathering up cobwebs and dust on pretty things. I was dismissed as a dolt that had not read the papers. The Pinkerton man winked at me, and chucked Percy under the chin.

I attempted to lessen the worth of the jewels, but Mammy said that the blue diamond alone was worth five hundred thousand dollars. I adopted a more pacific manner and inquired if Miss Ydonea wore grand oriental brocade with the rajah's gems.

"Oh, naw, naw. That would be too ordinairy," said Mammy, about whom I was now sure there was nothing Southern but her uniform and her name. She was a more practised actress than Ydonea, who had acquired her in Hollywood. "Naw, my lawdy! Miss Ydonea will have a palest, pale sea-green silk embroidered in cream, and then she looks like a northern mermaid, and all the jewels, oh, boy! like the lights you see flash on the waves at Catalina Island."

I was promised a glimpse of Ydonea when dressed. Other maids now appeared for a peep at the jewel safe, and Mammy Lou went through her piece again. Her only interest in Tattingwood, other than promoting her mistress's reputation, was a possible ghost. She was supplied with information that excited and terrified her. At a certain time of the year, according to contradictory authorities, or when there was going to be a death in the family, a ghost always paraded in the grand corridor. What shape the ghost took was not forthcoming.

Suddenly all the vassals disappeared as marvellously as young turkeys when Mommer Turkey announces a hawk, and I was face to face with the master of the house. The baron in his hall was as interested in Percy as the menials had been. Only the timid and the curmudgeon were ever above Percy's society.

"Oh, er, how did you carry the little blighter down?" inquired Lord Tattingwood, stopping to poke an affable finger under Percy's chin. Percy waved his arms like a windmill and made passes at imaginary monkeys in a way natural to him. His host grunted.

"Where will the little chap sleep? Must be careful he doesn't get out where one of the dogs will make short work of him...You are very fond of him, aren't you, my girl?"

"Veree, My Lord."

"Pity we couldn't find you something better than a little devil of a monkey at Tattingwood Hall." He looked at me with unmistakable amusement in his small cunning eyes.

"Percy sleep in da basket," I volunteered.

"I should like to see," remarked the gentleman, and it devolved upon a lady's maid to conduct him to our apartment.

He examined the waste paper basket lined with Percy's bedding. He was a man of simple interests, fond of shooting and hunting. He said there was a heavy footstool in his apartments which would make the scuttle quite safe as an anchor, and in a most democratic way took the hassock already being used and proceeded to make the change himself. "Come and see," he commanded. We met the friendly housemaid on the way to Lord Tattingwood's rooms, which were at the other end of the grand corridor beyond the middle tower. The housemaid rushed to take the hassock. As opportunity occurred she winked at me and murmured "The old chap's findin' his way home with you!"

"Da gentleman mooch interest in ma leetle monk."

"Monkey, my eye!" she retorted, an uncompromising girl, and spry. "You are not as used to these parties as I am. Sing out if you need any help." She deposited the heavy mahogany leather-cushioned foot-stool in Zarl's room and withdrew, again winking at large. Lord Tattingwood remained to place the foot-stool, and was apparently infatuated with Percy's antics. "Tie the little blighter up," he commanded. "I want to see if he can move all that."

Percy, when tethered, settled down in the glow of the fire with unusual placidity. Lord Tattingwood seated himself on a chair near by and without preliminaries pulled me to his knee. I remembered the housemaid's offer, but did not summon help. I eyed the poker near by and struggled to free myself. "Oh, Mr. Engleesh Lord, pies, pies, I good girl. I pray da Virgin all da time. I tink I hear someone coming."

That was efficacious. Lord Tattingwood resumed his game with Percy. "Who's in there?" he asked, indicating the door into the Chief Inspector's room.

"The swell polissman," I responded, critically surveying Swithwulf George Cedd St Erconwald Spillbeans, Sixteenth Baron Tattingwood. The eugenics of primogeniture had secured for him a coarse frame upon which sat a big red face with small eyes, a long ungainly nose, a narrow forehead and a sloppy mouth. He had one of those sandy skins, more often seen on dukes than barbers, and hair everywhere, even in his ears and nostrils. Ugh! On this had Clarice Lesserman sunk decent soap-suds money. What economics! Thinking enviously of what I could do with fortune of a few pounds, I murmured with genuine dejection "la poor girl!"

Swithwulf fossicked in his pockets and brought up half-a-crown. He proffered it, murmuring half to himself "The old harridan keeps me deucedly short!"

Noblesse oblige!

"Half-a-crown no gooda me."

"Hum, you know more than you seem to, it strikes me. You're a dago, aren't you? Dagoes are hot stuff. One has to pay for what one wants these days--and the man who doesn't take what he wants, when he feels like it, and the cost be damned, is a poor man. Do you know enough English to get the gist of that?"

I shook my head. "Da reech gentleman he must have what he wants," I ventured.

He took a pin from his tie and handed it. "Come to my room after dinner when they are looking at the shouties. You know where it is."

He was gone out the door.

I popped out in his wake. "Mista Lord," I called, feigning breathlessness. He was already at some distance. "Taka back--I honest. Perhaps I hava da monk and notta get away."

"Tie the blasted little ape up," he said, disappearing with astonishing celerity.

I returned to my quarters and examined the pin, a large pearl exactly like those priced ten bob at the Oriental jewel shops.

Blasted little ape, indeed! More like a blasted big gorilla! And all that good soap-suds money wasted. What a life!

Quel gaspillage!

I answered a knock on my door and found Captain Stopworth.

"There is a desire for Percy's reappearance in the lounge," he said with a slight twinkle of amusement in his eyes, "and as I was coming up, I have offered to act as his escort, and yours."

We went down the grand romantic staircase together. The Chief Inspector was charming--now if he instead of Swithwulf...

Me stood a moment looking down at the company lapt in that comfortable idle hour that stretches between tea and dressing for dinner, when men and women say the things that have to be said or listened to, in the hope of hearing or saying otherwise. The Elephant Hunter, by name of Brodribb, undertook to see to Percy so that he should not wreck the place. Deposited on the hearth rug, he was immediately another person. Studious, efficient, professional, he began upon his duties, the search for any unhygienic fleck or insect that might lurk within his reach. With his exquisite little hands he turned over the fur of a splendid bear rug which promised to occupy him indefinitely.

"You slip away and get your tea and amuse yourself downstairs," whispered Zarl.

"Don't miss your tea," Clarice added with a smile. "Your little pet seems as if he could do without you for a while."

Tea is a prosaic superfluity: a Tattingwood Hall as a hostelry, a rare enchantment. I had the wonderful place almost to myself for an hour, till the dressing bell should summon those responsible for the physical cleanliness of the people disporting themselves so banally in the great hall. I peeped into the drawing-rooms, peered along galleries lined with armour, took the noble vistas with an enjoyment that was compensation for existence. One could almost feel the emotions that must saturate the beams and stones of such a pile, half-hear bygone laughter, rage or grief, like the echo of an echo escaping along the stately passages.

What a theatre for lovers! How many had longed and lied there since the days of Elizabeth the Queen--from which in part it dated--to Clarice of soap, consoled for a dull lord by her handsome Chief Inspector. Well, great piles like Tattingwood Hall have been relinquished before to-day for romance, though such gambles are more glamorous when both parties to them are under thirty. Would the bulwark that Lady Tattingwood had secured against foolishness, hold?

I was too weary and cold to exert myself for my role in the comedy below stairs, so I slipped into Zarl's beautiful room where the big fire was so comforting. Zarl's things were spread towards the top of her bed, so without disturbing them I crept under the eiderdown at the foot, and aided by the warmth of the fire, set out to overtake some of the sleep which had of late eluded me. Just as I was gaining upon my desire. Lady Tattingwood entered from her room, accompanied by the Chief Inspector. Instead of passing into his own room, the Inspector turned the key in the door into the gallery and sat down with his friend before the fire. They sat in the glow of the coals which shone on the high wooden foot of the bed, but left me entirely in shadow under the eiderdown. They were comfortably settled before I had roused sufficiently to declare myself. I hesitated, and the only unembarrassing behaviour was to remain quiet hoping they would never know of my presence.

Clarice began to weep. She wept steadily and relievingly. Her companion let her alone for a few moments and then said "Well, my dear, you don't seem very happy to see me."

"Oh, but I am! The joy of having you here near me once more. Oh, Cecil, my darling!"

"We must be circumspect. This is very reckless of me now--if anyone came..."

"Oh, but they won't. They were all so entertained with that blessed little monkey. Did you ever see anything like it. And Zarl never rushes up to dress till the last moment. Her hair and skin and everything are so lovely and natural she doesn't have to spend hours in making-up."

"Well then, I brought those letters as promised, but I want you to reverse your decision and let me keep them--they are precious to me, and some day in the future may be the most treasured possession..."

Their actions were reflected in the mirror on the dressing-table. Clarice leant toward him, and he put a kindly arm around her. "You want happiness to be known someday. You are ashamed of it?"

"Oh, no. But your career has to be considered, and also Swithwulf's position."

"All that he asks is to be let alone on his own trails. He is perfectly indifferent."

"He might seem to be. But he is very cunning. He is not stupid...Oh, I'm so tired of Tattingwood and what it entails...I want to go away."

"That is why it is foolish to run risks."

"But I had to have something to carry me along...and this is a good opportunity...How is Denise?"

"More like her mother every day. She is always asking me about her mother. I have a struggle to evade her questions. Some day soon I must tell her the truth."

"Better not. Young people are so conventional. She would feel disgraced, and never forgive."

"A new generation has come since the war, and I am training Denise to have an open mind, so that she will be prepared. I discuss all sorts of things with her. I am teaching her to understand the romance of her parentage."

"I am so weary waiting."

"But I don't want to be marked as a fortune hunter. The money complicates matters."

"Are you sure you really want me without the fortune? I am old now, and I often wake up in the night terrified, because I have been dreaming that you were only ridiculing me."

"You must not make it difficult for me. You know there has never been any woman for me but you. Surely my life has demonstrated that."

"Oh, yes dear, and I am so grateful."

"Well, trust me with these," he tapped his pocket. "My life must be uncertain, and I'll put these away in some vault in a sealed and locked packet, with a letter."

"Oh, don't talk of that. It reminds me of the war. You can have the letters, but if Swith found them it would be fatal."

"Thank you Clarice...Ssh!"

The Chief Inspector was gone to his room, with amusing speed. Lady Tattingwood attended to the key into the gallery, and then returned to her own room with slightly less dispatch. There were voices in the gallery, and I had just time to slide off the bed and switch on the light when Zarl turned the handle of the door. She was attended by the Elephant Hunter and Jimmy Wengham, who were in charge of Percy so that finger nails would not injure Zarl's trousered suit. Jimmy could not forbear to tease animals and children, Percy, catching sight of me, laid his ears back for a desperate effort which carried him with a whack to my shoulder, where his nails would have lacerated my skin but for the high-necked uniform. I snatched the lead, and the little creature snuggled to me with murmurs of relief.

"You bad man. My little Percy he notta like you," I said. After a little banter, the two men went away to dress. Percy had subsided and was lashed to the coal scuttle. He sat on the floor squawking softly and rubbing his nose with his hand. He was a trifle hungry, kept so expressly in order to be open to bribes.

Zarl was to wear my new dress, and no decorations whatever but Percy, just to contrast with Ydonea, who was to drip with trillions and crocodillions of jewels.

"I haven't a working wit, so I'm in the hands of my maid," smiled Zarl, whose amenability makes her a delightful companion. The dress was a soft velvet, which glinted greenly in certain cross lights; a wrapped wisp to the knees, below which it flowed in undulations. It would disclose Zarl's perfectly fashioned arms and torso with barefaced but well-grounded optimism, and heighten her "ginger."

"I hate my freckles," she protested.

"There are none below the belt, so to speak," I remarked, laying out her implements of toilet.

"You don't like Jimmy Wengham," she commented. "You would have liked him less had you seen him downstairs. He started cutting Percy's nails with that horrid dirk till they bled. I don't know what has come over Jimmy. He seems so brutal--I don't know how I could have carried on with him even for a minute."

"Did you?"

"You don't suppose he'd lug Percy all the way from Africa in an aeroplane for me unless he had been infatuated. But he wants to go to excessive lengths in love."

"How far?"

"Don't be such a peanut! He's sheerly sloppy. I've been telling him to reserve such mush in case he comes down in a desert atmosphere. England is mawkishly damp already. He always wants to go the whole engine!"

"Merely the usual, isn't it, nowadays?"

"It's carrying a cocktail like love altogether too far. Some men carry even a kiss too far, if they are not curbed. It shows a deplorable lack of imagination."

"How far do you consider love can be carried without being too far?"

"Just to that point where the final demonstration to a person of imagination, would be a clog upon imagination."

"I see...and the anticipation...you like that to inspire an expedition to the Antarctic or the Pole of Cold...I'm thankful Jimmy did not quite recognise me."

"He wouldn't split if he did. Swithwulf has been telling me that he was right on the rocks. Clarice had to salvage him, and Cedd put him in the way of this job with the Zaltuffrie, to tide him over. He's mad to do a world flight, but he's such a cracked-brained thing that the aeroplane people won't trust him. He'd be likely to take off without his petrol or something like that."

I confided to Zarl that I had found Clarice weeping when I came up. Seeking to discover if Zarl knew her secret, I asked "Do you suppose it hurts her when old Swith tries to be gay?"

Zarl laughed right out. "Really, you are too middle-class for a lady's maid among the best people. It comes of carrying respectability too far. Clarice is not such a goat with a cast-iron throat...If ever she did care, except from the point of hygiene and expense, she would have outgrown it long ago...Much more likely that Cecil has said something to her. I'd like to ravish that man myself, only I would never be mean to Clarice; but you've only got to look at them to see it could not hold up--why, she looks like his grandmother, and doesn't try to mitigate it."

"If she had her face lifted, and dyed her hair, it would show weakness."

"Clarice is weak. That is what makes her so lovable and kind."

"Is this from Woolworth's, do you think?"

I showed her the tiepin. She knows a little about jewels and antiques.

"It looks like a platinum setting, and if the pearl is as real as it looks it could be anything from fifty pounds to a thousand. Where did you get it?"

"Swithwulf George St. Erconwald Spillbeans Tattingwood gave it to me for mes beaux yeux. So, while you have been adventuring, I too have not been idle. He has named a trysting place for this evening."

"The colossical old reprobate! Clarice told me once that he humiliated her by his selection of ladies. She said if only he would choose someone like me she would not feel it such a reflection, but I didn't think..."

"You didn't think it was so bad as a coolie on Percy's string."

"I did not think he would have such discernment, or else your incognita is satisfactory," bubbled Zarl. "I'd just hang on to the pin if I were you. You are entitled to adventures among the best people. Their lives are an artistic struggle to escape from the drabness of carrying respectability too far."

"You say that you picked it up, and return it to Clarice."

"What are you going to do about the tryst?"

"What do you think?"

"That his optimism is barefaced, like the gallant Captain's who picked me for his lady for the voyage. Clarice will revel in this when the time comes to reveal it."

"If ever it should."

"We'll skip off home to-morrow. This mouldy collection of oddments doesn't contain one man who could be pried loose from a life-size cigar or a bar parlour, except the Elephant Hunter or Jimmy, and each of those is more stony broke than the other, and each more luny. With people like that it takes altogether too much effort to keep them in the platonic form, whereas the nice professor scientists don't know what is the matter with them but it works just the same..."

"Yes, like a donkey being lured on by a bundle of carrots on the end of the shaft, even unto the Arctic seas."

"Exactly, but I did not construct the universe, and all things are there for our use. The difference between you and me is that I accept the world as it is and you want to mess around and change it, and think it would or could be different if only this or that wasn't what it is."

She was a delectable established fact in the green velvet. Her petite form had a lissom outline. Percy was attired in his black velvet evening shorts, specially designed for him by Madame Mabelle, with a white silk knitted singlet. We could not have buttons on the sides of the trews because he chewed them off, but there were glass buttons at the back to fasten the tabs over his lead.

Clarice entered to have a little chat with her friend before she descended to dinner. She wanted Percy to be present, and said that I could arrange for that with the butler. I agreed with alacrity. "You are fortunate to have a maid so devoted to your little pet," she remarked to Zarl, as I went out.

There is room and to spare in the dining hall of Tattingwood to entertain an elephant or giraffe should the lord of that manor have taste for such guests.

We spread a sheet at one corner and brought in a small heavy garden table, and on it set Percy's tiny bowl of light ware, from which he would drink in his human ultra-dainty fashion. These jobs gave me an excuse to run up and down stairs while the guests were in their burrows dressing. As I turned into the great gallery from the tower stairs the Chief Inspector, already dressed, was ahead of me, evidently going the rounds in his official capacity. His evening uniform was beyond sartorial censure, fresh yet easy, and his flesh glowed with fragrant health; a man to win any woman, and yet he seemed true to Clarice, the ineffectual, ten or twelve years his senior, and making no attempt to soften the disparity. There was dignity in the stability of this romance when compared with those that are as fleeting as barnyard amours. If he really did not desire Clarice's fortune, it was classical, even colossical.

I looked back after him and thus collided with a form coming in the opposite direction. It was the splendiferous Indian chauffeur, Yusuf. He was not a personal attendant and should have been with the other chauffeurs above the stables, long since converted into garages. He was, no doubt, prowling as guardian of the jewels, but I was so irritated by the impact that I boxed his ears and sped to Zarl.

It was time to descend. No trace of tears was now on Lady Tattingwood's hollow cheeks. An inner radiance informed her, gave her gaiety and took ten years off her age. She was tastefully gowned in a quiet conventional style, and was a contrast for Zarl who looked like a mischievous elf in the extreme garment, with Percy wrapped in brown silk and held in the crook of her arm.

Mommer and most of the retinue were downstairs, but Ydonea was still awaited. She floated down the great staircase eventually to make an entry lifted unblushingly from the films, as sure of herself as a crowned princess in professional regalia. She approached slowly and regally and posed before one of the big fires in the lounge. Every male creature cavorted before her, casting covert glances or glaring, in key with his character. Cedd and Jimmy led the scrimmage, but business partly dictated their attitude. Even the Chief Inspector paid court, and his distinguished appearance exacted response from Ydonea. No woman could have resisted Cecil Stopworth had he exerted himself to woo. The more astonishing therefore was his faithfulness to Clarice. No wonder that people should doubt its reality.