a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Diary of a Honeymoon Trip to Australia in 1897 Author: Evelyn Louise Nicholson (edited by Colin Choat) eBook No.: 0607521h.html Language: English Date first posted: September 2006 Most recent update: April 2020 This eBook was produced by: Colin Choat

This work is licensed under a

Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia

Licence.

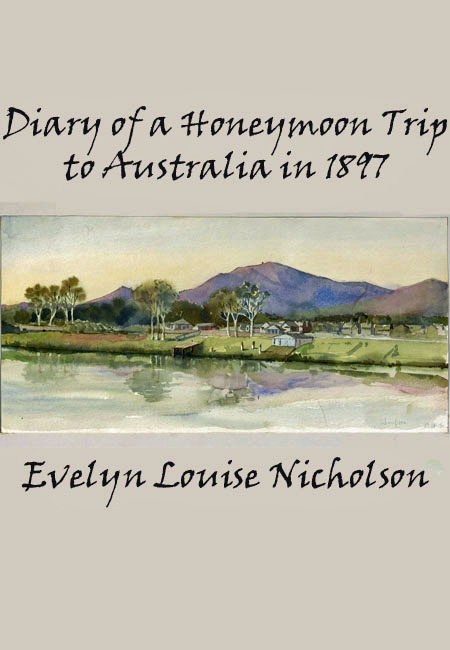

The cover sketch is from "Mt. Nicholson, Rockhampton" painted in August 1897 by Charles Archibald Nicholson, Evelyn's husband.*

[* Mt Nicholson was named by Ludwig Leichhardt (1813-1848?), naturalist and explorer, on 27 November 1844, after Charles Nicholson (1808-1903) doctor, politician, landowner and businessman. Leichhardt noted in his Journal of an Overland Expedition in Australia that "the most distant range was particularly striking and imposing; I called it "Expedition Range," and to a bell-shaped mountain bearing N. 68 degrees W., I gave the name of 'Mount Nicholson,' in honour of Dr. Charles Nicholson, who first introduced into the Legislative Council of New South Wales, the subject of an overland expedition to Port Essington." Charles Nicholson was Evelyn Louise Nicholson's father-in-law. More information about him and about Evelyn Louise Nicholson and her husband, Charles Archibald Nicholson, together with brief details about a number of other people mentioned in the diary, can be found at the end of this ebook.]

This ebook incorporates the untitled diary that Evelyn Louise Nicholson kept from 10 June 1897 to 13 October 1897, during a trip to Australia in 1897, together with a number of the sketches which she and her husband painted during the trip.

In the diary, Evelyn Nicholson gives a picture of life during, what she terms, a "honeymoon trip.*" She describes the voyages to and from England, the cities and towns which they visit and provides an account of the food, the landscape, the flora and fauna and the weather, as well as acute observations of her fellow-travellers.

[* Honeymoon trip: See 20 September 1897]

The diary and sketch book are held in the Rare Book and Special Collections section of University of Sydney Library.* A partial transcription of the diary was published by the library in 1999.

[* Evelyn Nicholson's trip to Australia, 1897.]

After the first few pages of the diary, in which the author describes the departure of her husband and herself from England and begins to describe the sea voyage, the narrative is interrupted by a description of a visit to Sydney University. The author then, on page 10, under the date of 27 August 1897, describes a some of their movements on returning to Sydney, after a voyage by steamer to Rockhampton and return. Then, on page 11, under the date of 6 September 1897, she writes that the diary had:

"met the usual fate of dairies, and ended abruptly. In fact it is so short a time ago that I can clearly remember all the incidents, tedious and otherwise, of our outward voyage. Possibly it is as well that the diary came to an untimely end, owing to headaches and general slackness, as it could at best have been but a gossiping record of our first impressions (modified or confirmed as time went on) of one's fellow passengers, and of the few sails we passed. And the more numerous specimens of the animal and bird would [have been] so much more beautiful than either."

The author then takes up the narrative from where she left off, at sea, a short time out from London, and the rest of the diary describes the voyage to Sydney, the return trip to Rockhampton and the Nicholson's return voyage back to England. The text of this ebook is in the same order as the diary.

Evelyn Nicholson's sketchbook contains watercolour sketches, by both herself and her husband. Some of the sketches are referred to in the diary. All of the sketches have been inserted into the text at relevant places, according to the dates shown on them. Some other images of printed menus, passenger lists, and miscellaneous drawings are included in the collection. These have also been inserted into the ebook, at appropriate places in the text.

Evelyn Nicholson's sketches often bear the initials "ELN" whilst Charles' sketches are signed "CAN". Some sketches are unsigned.

The text of the diary is out of copyright in Australia, as are the sketches by Evelyn and Charles Nicholson. Original content added by me, such as the cover and notes are copyright. Readers may enjoy them under the Creative Commons licence shown at the beginning of this ebook.

Colin Choat

April 2020

0

Introduction

Evelyn Louise Nicholson's Diary

from 10 June 1897 to 13 October 1897

1 Departure from England

The narrative of the voyage was here interrupted

by the author to give an account of a visit to

Sydney University, after making a return voyage

from Sydney to Rockhampton.

2 Sydney University

3 The Voyage from Teneriffe to

Sydney.

3.1 Teneriffe

3.2 Cape Town

3.3 Hobart

3.4 Launceston

3.5 Melbourne

3.6 Albury

37. Sydney

4 The return voyage

from Sydney to Rockhampton

4.1 Sydney

4.2 Brisbane

4.2a Maryborough

4.3 Gladstone

4.4 Rockhampton

4.5 Bundaberg

4.6 Brisbane

4.7 Sydney

5 Homeward Bound

5.1 Wellington

5.2 Cape Horn

5.3 Montevideo

5.4 Teneriffe

5.5 England

6 List of sketches from the sketch

book

7 List of Other images

8 Details of some of the people

mentioned in the diary

O Off Finistere.

O St Elmo: Santa Cruz and Coast of

Teneriffe.

O Coast of Teneriffe.

O Sunrise, Teneriffe.

O Santa Cruz

O Teneriffe

O Peak of Teneriffe

O Peak of Teneriffe after sunset

O Table Bay, 2 July 1897 [ELN]

O Table Bay, 2 July 1897 (CAN)

O Hobart and Mount Wellington, 20 July

1897 (C.A.N.)

O Near Hobart, Fern Tree Inn, 21 July

1897 (C.A.N.)

O Fern Tree Hollow, Tasmania, 21 July,

1897

Mount Wellington, Tasmania, from train, 22 July 1897

Launceston River (Tamar), July 22, 1897 (C.A.N.)

Bridgewater, Tasmania, 22 July 1897

Tamar River, W. Launceston, 22 July 1897

O Sydney

O SCENES AROUND SYDNEY HARBOUR

Manly Ocean Beach, 30 July 1897

Sydney Heads, 30 July 1897

Pinchgut fort, 30 July 1897

O SCENES AROUND SYDNEY

Pinchgut Fort, 31 July 1897

South Head, 31 July 1897

Sydney, from Harbour, 31 July 1897

Sydney Smoke, 27 July 1897

Ashfield, 28 July 1897

O Fitzroy River, Rockhampton

O Mounts Nicholson and Archer,

Rockhampton

O Mount Nicholson, Rockhampton

O Rockhampton, 10 August 1897 (C.A.N.)

O Grangemount, Rockhampton

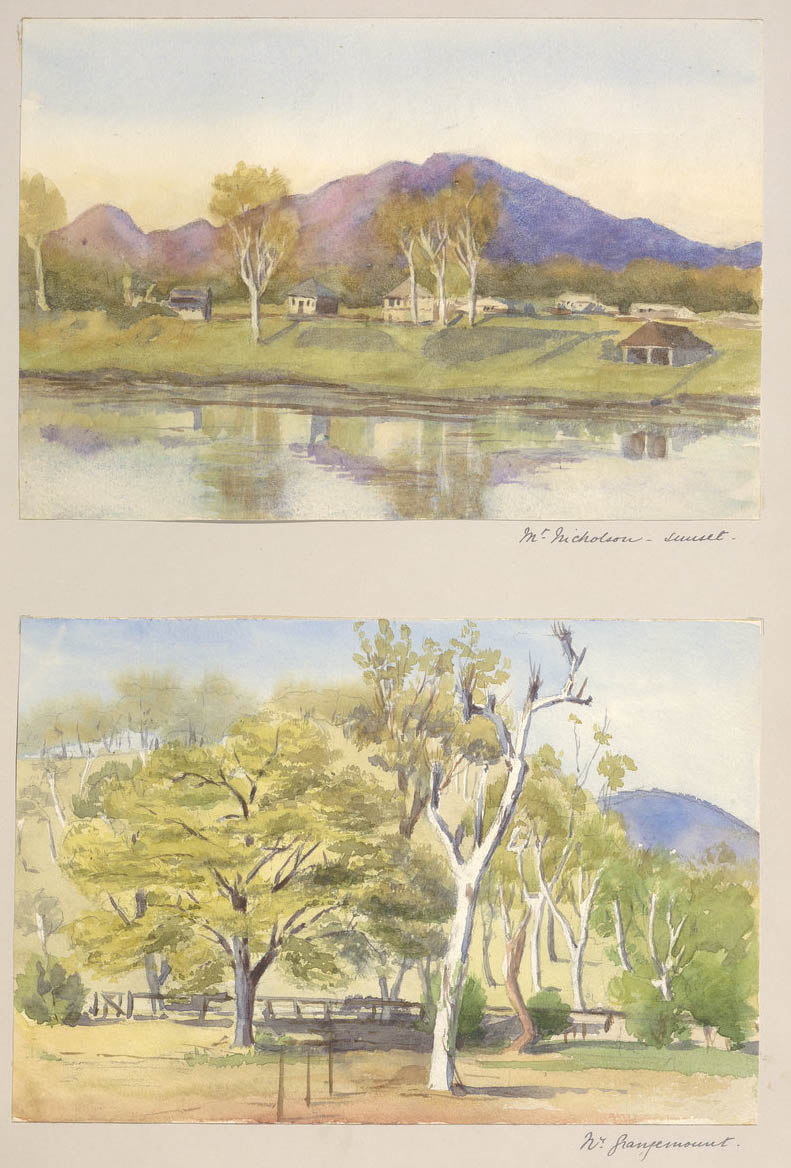

O Top: Mount Nicholson, Sunset

Bottom: Near Grangemount

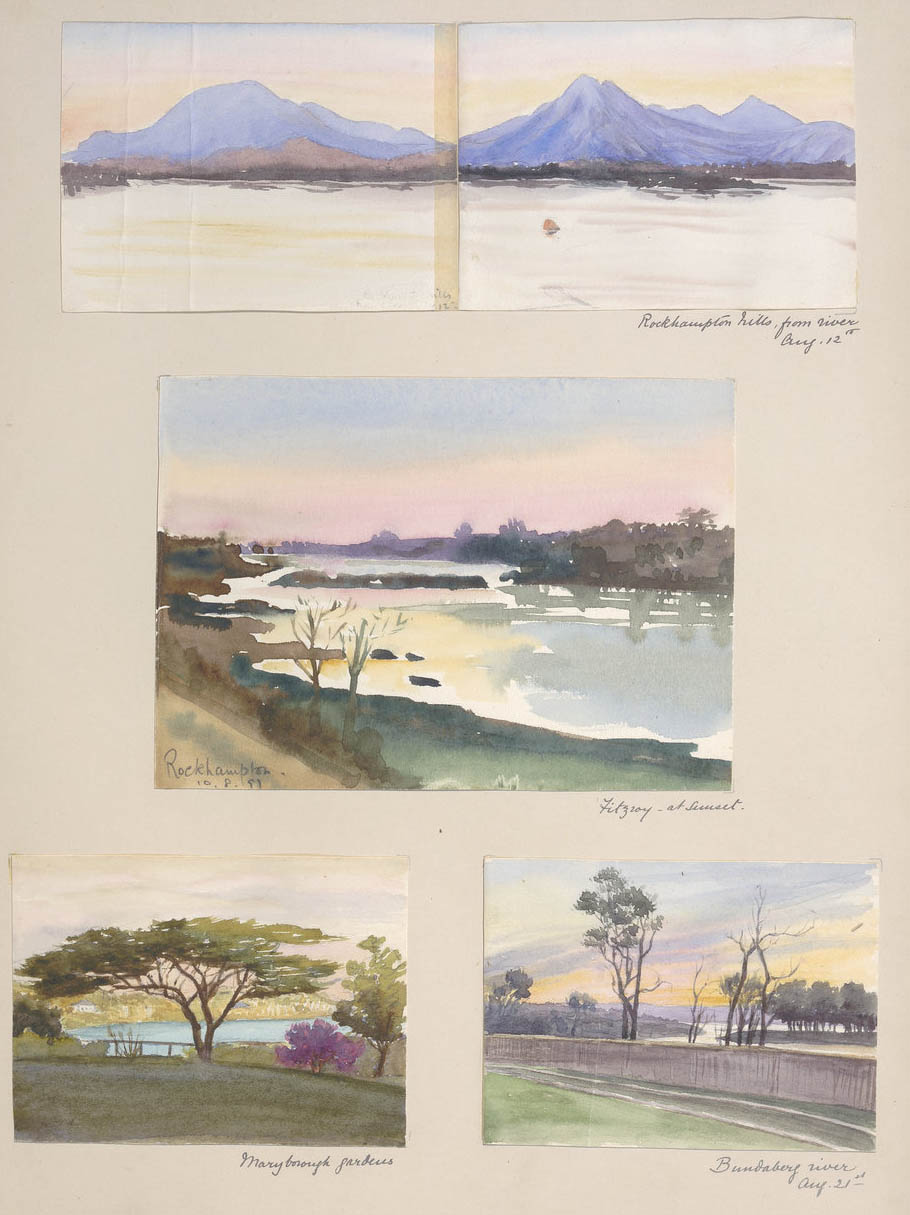

O Rockhampton Hills, from River, 12 August

1897

Fitzroy River, at Sunset, 10 august 1897

Maryborough Gardens

Bundaberg River, 21 August 1897

O "Bauhinia" from Maryborough, 5 August

1897

O Tasmanian Heather, Berries and Fungi, 21

July 1897

O SYDNEY, 27 JULY 1897

1. Christmas Bell

2. Garlic

3. Epacris

4. Flannel Flower

5. 6. 7. Baronias (sic)

O Top: Pomegranate, Thumbergia, Red

Bougainvillea,

Sturt's Desert Pea (Clianthus Dampieri), August 1897

Bottom: Wild flowers, Rockhampton, August 1897

1. Verbena, 2. Ozalis, 3. Vetch, 4. [no description], 5. Devil's

Apple

O Coral Tree, Sydney

O Strelizia, Ashfield

O Charles Archibald Nicholson (1867-1949)

O Sir Charles Nicholson (1808-1903)

O First page of Evelyn Louise Nicholson's

Diary

O Dinner Menu for R.M.S. Gothic first

class passengers, 22 June 1897

O Breakfast Menu for R.M.S. Gothic

first class passengers, 20 June 1897

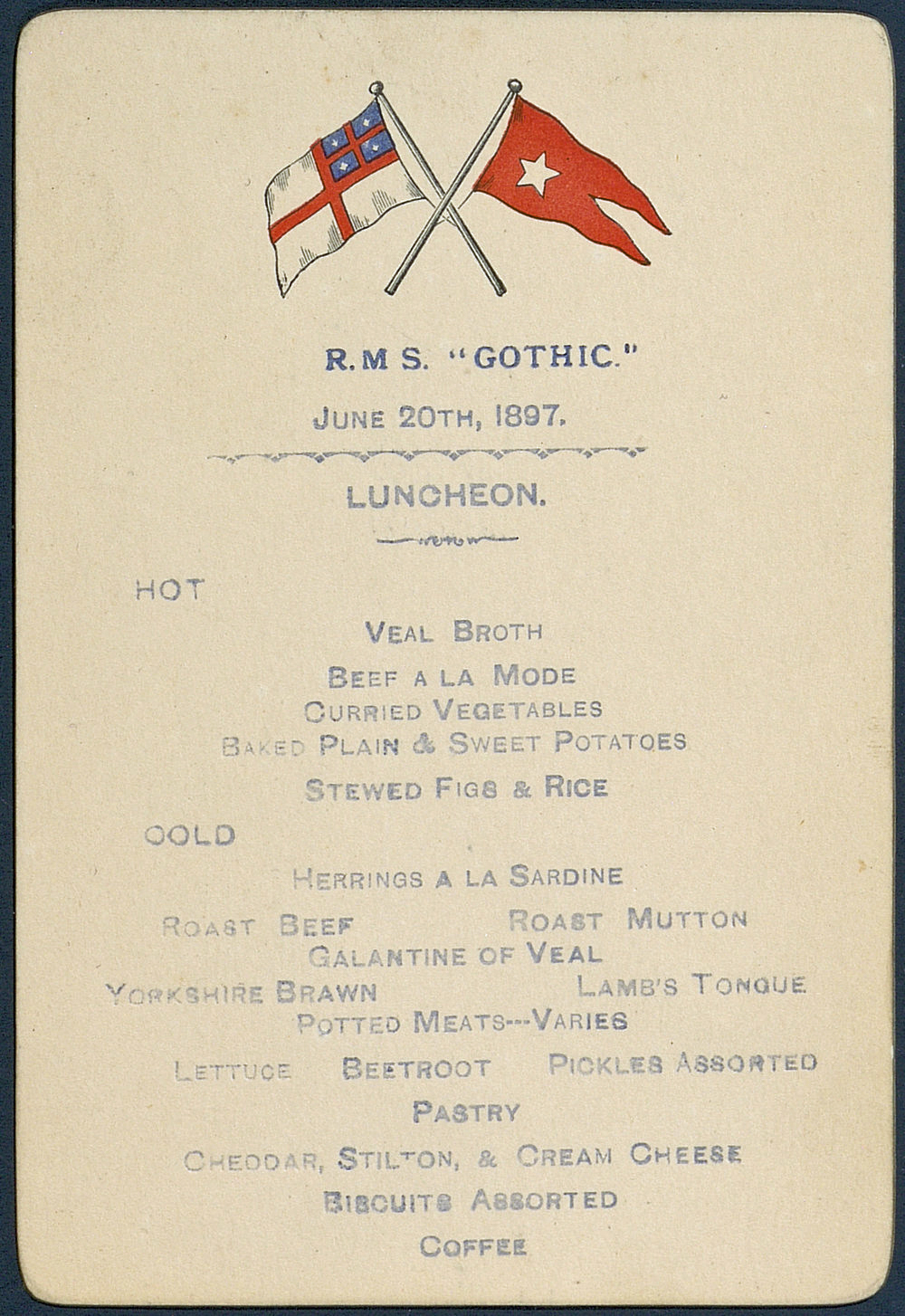

O Luncheon Menu for R.M.S. Gothic

first class passengers, 20 June 1897

O Dinner Menu for S.S. Tongariro

first class passengers, 12 October 1897

O Dinner Menu for S.S. Tongariro

first class passengers, 12 October 1897 (reverse side)

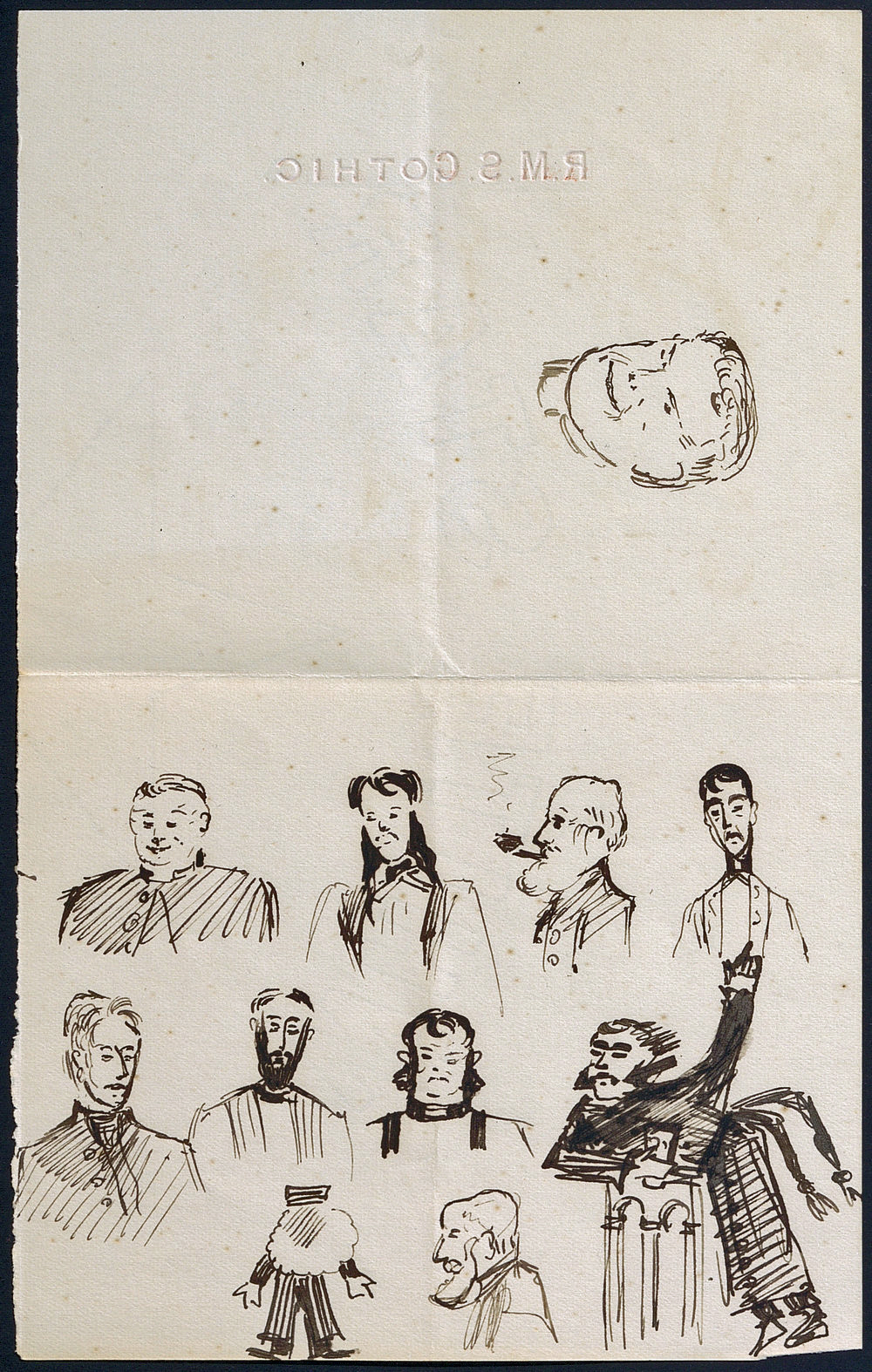

O Sketches of people on the R.M.S.

Gothic

O Sketch of two women

First page of Evelyn Louise Nicholson's Diary. Courtesy of State Library of New South Wales

{P1}

Thursday 10 June 1897 to — Monday 14 June 1897

1. Departure from England

The fourth day we have been at sea. We embarked at the Albert Docks on Thursday 10 June but the ship did not start until next day, while we were at breakfast. It was a relief to get out of those horrid docks and steam slowly down the Thames with its prismatic coloured flats and hazy blue hills, past innumerable boats and barques with sails all shades of red and brown and drab.

Archie left us at Gravesend. We felt rather blank at first and I began to wake up out of the dreamlike existence of the last few days and realise we were off and alone and together. I can't say I saw much of the Kentish shore or of anything else that evening for my head ached so badly, after the sounds and smells of the night, that I stayed in my cabin the rest of the evening, only coming up for a few minutes to see the end of a most gorgeous sunset, red and purple over a golden and green sea.

We made up for everything by an excellent night and found ourselves nearing Plymouth, when we arrived on deck. I had {P2} made acquaintance with the two Miss Bournes the day before, or rather, renewed my acquaintance with Miss Clara Bourne, who was as charming as ever. We much regretted her leaving us at Plymouth where the pilot, a nice old man in a top hat, also wished Charlie and me an affectionate farewell.

We both painted all the morning. Charlie began to find an affectionate boy who had limpetted [sic] himself, after the manner of boys; rather a nuisance. I slept all the afternoon (we left Plymouth Harbour during lunch time) and when I woke we came on deck and watched the Cornish coast fading into the distance.

The weather was perfect and we sat on deck in the moonlight till quite late. We both drew one or two full-rigged ships that passed us and caught the evening light in the most effective way. Yesterday (Sunday) we only saw three ships altogether and no land. It was a grey day, with gleams of sun and a most {P3} unpleasant swell, which made everyone very miserable, though they all considered themselves very brave.

I don't think anyone was actually seasick, though Charlie became very green at tea time, so the kind Mr. Inman cut that meal (which we had in his cabin, with him and the doctor) rather short and, after lying down for a bit in our cabin, Charlie was soon all right again.

Off Finistere, 14 June, 1897, (C.A.N.)

{P4}

Monday 26 July 1897

[The narrative of the voyage is interrupted here

to give an account of a visit to Sydney University,

after taking a return trip to Rockhampton]

2. Sydney University

Ink is too valuable, and so is time, so I must put down my impressions of Sydney University in pencil. I do so much wish it were finer, as the view from there must be lovely, but one could only see a few towers and chimneys through the thick haze of rain. They have not had a rainfall like this for many years, and many places which are usually green fields, are converted into lakes.

We splashed through the streets with Thomas and eventually found a steam train which rushed us through what seemed interminable suburbs, where parks and dust heaps; huge stores and tiny dwelling houses one storey high; miles of hoardings with advertisements of purely local productions boldly purporting to be in use all over the world; were mixed up in bewildering confusion.

The suburbs extend to, and beyond, the gates of the University gardens, which no longer are in the country. They are well planted and plenty of hibiscus, trumpet ash, laurestinus and other flowering shrubs were out. The older part of the building is by far the best. The medical school, a large separate building in the same {P5} style, is a mongrel imitation, the Macleay museum being a terrible edifice in brown brick which is being smothered with ivy as fast as possible. The tin roof, however, nothing can hide. The Schools of Chemistry, Physics, and Engineering are in low somewhat shed-like buildings, and at the back there are even wooden and corrugated iron erections (some of them devoted to the lady students) mixed up with tennis-grounds and asphalt paths, which give a very un-scholastic appearance to that part of it.

The more temporary ones will, however, be swept away if Government grants the £30,000 necessary to complete the side of the quadrangle opposite to the Great Hall. This, Mr. Barff, the Registrar, who took us round and showed us everything with the greatest kindness, told us they had great hopes of commencing next year. I said I hoped they would also complete the cloisters.

They allow golden ivy to grow up the buttresses of the hall which give it a more venerable appearance than the rest of the main building, but {P6} the coats of arms between each are not going to be covered up. I saw the well-known one, on the right of the big door of the hall outside, and also in one of the windows in the entrance hall, where some of the tapestry, and pictures given by Pater are also hung.

The great hall is very fine indeed, the roof beautiful. The picture at home does not give a good idea of it, as it is very dark, the large windows being all filled with coloured glass. Pater's portrait occupies the left hand side of the end wall, in the place of honour, and there are various prints of it in other parts of the building. It is too much in the dark to be well seen, and though strikingly like Syd, is not an altogether good likeness, the head being so small as to give the impression of a very tall man.

We recognised the portrait of Mr. Denison and were shown that of Sir W. Manning and other people. We saw some of the lecture rooms and then Mr. Barff took us to the museum where everything seemed to be labelled with {P7} Pater's name, and there was a general idea of him pervading everything.

This beautiful collection is not seen to the best advantage, as it occupies one large, and two smaller rooms, but the things are beautifully mounted and most carefully arranged. The new buildings will consist of a museum below and new library above.

For the splendid collection of books they possess, the present premises are very much cramped. The Etruscan vases in Pater's collection cannot be seen to advantage, being too near together. They are most beautiful and varied, and the Egyptian collection is wonderfully interesting. I do not think two such enthusiastic visitors as ourselves can have surveyed them for a long time.

Mr. Barff says the Greek and Roman things are the most interesting to the general visitors. The paintings on the mummy covers are as fresh as possible, and Charlie was delighted with them and the little Etruscan cinerary urns and the inscriptions and everything. We are going again when we return, if possible.

{P8}

They are very proud of them, though I doubt if many people know much about them! We were loath to leave the museum, but there was so much to see, and we got home very late, as it was. The Macleay Museum of Natural History has some good specimens, but is not well arranged. Several huge casts of Egyptian antiquities (waiting for the new buildings) mixed up with the stuffed animals and skeletons, give it a somewhat grotesque appearance.

While we were here, a violent storm of rain descended with a noise like thunder on the iron roof, and when it was over we rushed through mud and puddles to the Medical School. They are very proud of this and the stained glass in the windows thereof. I have no doubt it is a most convenient and suitable building, but it is extremely hideous. There is an excellent pathological museum, with rather too many horrors for my taste, and we also saw the huge lecture rooms, and well fitted laboratories, and declined to go into the dissecting room!

{P9}

The Engineering School interested me very much, as did that of Chemistry where we were introduced to Professor Liversidge and much enjoyed seeing some most beautiful specimens of gold in nuggets, which he brought out for our benefit. When sawn through, the finest of these (about 3 inches across) presented the appearance of crystalline formation, all in the purest gold. He took us to see the furnaces for refining, and the gold, and we also saw the museum, with good specimens of minerals and a quantity of the copper sheathing of a vessel, which the professor told us contained minute particles of gold, and which he was going to test.

Professor Threlfall showed us the Chemistry School, and described his interview with Pater in London, which seems to have much amused him, and then, last of all, we inspected the Biology School, which I think pleased me, most of all the new part. It is only a tiny, low building with a creeper covered verandah, but is most compact and well arranged, and the little museum perfect in its way. Mr. Barff kindly promised to get one or two photographs done {P10} for me to take to Pater, as I did not see any good ones of the University in Sydney.

[In Sydney, after returning from a trip to Rockhampton.]

Friday 27 August 1897

When we returned to Sydney, we spent another delightful afternoon at the University, this time in fine weather, and in company with Lady Manning. Mr. Barff was away, but had left a proof of his kindheartedness and sympathetic interest, in the shape of a lovely book of photographs for Pater.

We spent a long time in the Great Hall, and wondered more than ever at the bad taste of the present Sydneyites with such an example before them. In the Nicholson Museum* we made one or two little sketches of some of the beautiful things, but our time was too short. We were extremely glad to have the opportunity of refreshing our remembrance of what interested us most there and, in fact, of what we shall always remember as the pleasantest of our experiences in Sydney.

[* See Wikipedia, Nicholson Museum]

{P11}

Monday 6 September 1897

3. The Voyage from Teneriffe to Sydney.

It does not seem at all long since I resolved to keep the diary which has met the usual fate of diaries and ended abruptly. In fact, it is so short a time ago that I can clearly remember all the incidents, tedious and otherwise, of our outward voyage. Possibly it is as well that the diary came to an untimely end, owing to headaches and general slackness, as it could at best have been but a gossiping record of one's first impressions (modified or confirmed as time went on) of one's fellow passengers, and of the few sails we passed, and the more numerous specimens of the animal and bird world so much more beautiful than either.

We soon got accustomed to the objectless horizon and, by the end of the first week, to our fellow passengers, the whole of whose names I did not, however, arrive at till about halfway.

Thursday 17 June 1897

3.1 Teneriffe

We reached Teneriffe on June 17* and got up early to see as much of that beautiful coast as possible. Our table companions and chief friends were already on deck. They were:

[* There is a blank space in the manuscript where, it seems, the author intended to enter the day, but did not do so. There are sketches made at Teneriffe on 17 June 1897, so that date has been used.]

Mr. & Miss Headington, an old gentleman of a most sunny and happy disposition and an equally good-natured daughter; Mrs. {P12} Cohen, a pretty Jewess with two dear little children, going back to her home in Melbourne after a year's absence; The Hon. C. E. Hill-Trevor and Lieut. H. D. O. Ward, R.H.A., Lord Ranfurley's two aides de camp* with whom we soon became great friends.

[* See the interesting photograph at Wikimedia Commons. Lord Ranfurly was Governor of New Zealand.]

Why everyone on board failed to do so, I can only attribute to jealously, or some small measures of that sort, as they were uniformly kind and pleasant and most considerate for all on board, excellent company and clever into the bargain.

Well, all these people met us, brandishing sketchbooks for the most part, and upbraided us with our lateness. I accomplished two sketches before the sun was very high, so did not do badly. Charlie went on shore almost immediately in a small boat with Mr. Inman.

St Elmo: Santa Cruz, 17 June 1897, (C.A.N.)

Coast of Teneriffe, 17 June 1897, (C.A.N.)

Sunrise, Teneriffe, 17 June, 1897.

Santa Cruz, 17 June, 1897

Peak of Teneriffe after sunset, 17 June 1897

It was a very hot day, and my head ached, so I did not join the rest who went on shore, but tried to paint till the black dust (we were coaling) over everything stopped me. I finished up our letters and later on watched the little dark-skinned boys diving for pennies from a boat by the ship's side.

{P13}

Charlie returned in the afternoon, with ten sketches, which give me a better idea of the place than anything else could, and the others arrived just in time, before we started, having had a long drive to Laguna and brought back some lovely fruit.

Mr. Inman had brought me some in the morning, when I was gasping, and I was also looked after by Mr. Buxton, with whom we had made quite friends, he being, as I soon discovered, younger brother to V. Buxton and going out to his people at Adelaide. His sister, a young lady with a charming face, which attracted me at once, had seen him off at Plymouth (where Mr. Ward also came on) and I did not then know she was the girl I had met at Grasse eleven years before.

All through the voyage these continued our chief friends and, by degrees, one corner of the library got to be looked on as our property, though in the hot weather we did not trouble that stuffy apartment much. Charlie and I almost always had tea with Mr. Inman on Sundays, and sometimes in the week, and there used to meet Mr. Bartlett and Mr. Gannule, two of the ships officers, which wretched individuals {P14} are not allowed by the Shaw Savill regulations to be acquainted with the passengers. Mr. Gannule, however had known my cousin, George Oliver, so we ignored the regulations.

In fact, as much as possible, we annoyed the Captain, for whom no one had any love, and as even a polite question was an annoyance to him (so great was the great man's dignity) it was no difficult matter. Mr. Inman, the Dr. and the Captain took turns weekly to reside at our table and much jollier it was the weeks our friend was there. At any time it was the jolliest and most conversational on the ship and was envied or hated accordingly, as the case might be.

During the hot weather, life was only possible on deck, and our principal occupations were drawing each other and talking. Mrs. Cohen and Mr. Ward did some really clever caricatures. Charlie got through a certain amount of work, and was regarded as a wonder by all on board.

Sunday 20 June 1897

I remember Sunday June 20 remarkably well. It was intensely hot and I got a slight coup de soleil, looking over the ships side, at the curious {P15} little Portuguese men of war, floating on a perfectly shining sea. Besides that, two dolphins, the most gorgeous blue and prismatic fish, passed under the ship.

At service, where the Captain presided as usual, we had the special prayer for the day and the hymns chosen for the occasion in England.* I had played the hymns the first Sunday, but got Mr. Inman to let me off and a rather feeble person played them as far as the Cape. The Captain's pronunciation of the names in the lessons was a cause of hilarity during the whole voyage. I remember he called Phessice "Venice," Sisera "Sisira," and prayed for protection from the "voylance" of the tempest.

[* On 20 June 1897 Queen Victoria celebrated her diamond jubilee, as Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Wikipedia.

Tuesday 22 June 1897

On 22 June the saloon presented a gala appearance, being hung with flags and jubilee tri-coloured muslin, and every table was ornamented with flowers by Mr. Inman, who had kept them alive in the freezing room and sat up half the night to make the saloon look as festive as possible.

Besides extra good meals and unlimited champagne at dinner, and drinking Her Majesty's health, {P16} the only other special thing to mark the day was that at four o'clock a rocket was fired off and we all on the two decks joined in singing God Save the Queen, (with the new verse), after which I retired to bed and lay with my head on ice all night.

I was very bad all next day with the usual accompaniments of sun-stroke, but the next day I was better, though my head still ached. That Monday we had heavy thunder-storms and all that week the weather was oppressively hot, with rain at night, so that the windows were kept shut and life was a burden.

The evenings on deck were cool and the phosphorescence beautiful.

During the whole voyage, we had a concert in the evening, given by the steerage, to which we all listened, a much more successful affair than one we had attempted on deck the previous week.

Wednesday 23 June 1897

After the worst of the hot weather was over (we crossed the line on 23 June) the Sports Committee set to in earnest and three or four days were enlivened by most people making, more or less, exhibitions of themselves. I won the {P17} second prize [in the] egg and spoon race, and C. the first [in] arithmetic. Lord Ranfurley's ten servants came out strong in the sports. The caricatures went on as usual, and by the time we got to the Cape, we had quite settled everyone's histories and the skeletons in their most private cupboards, and were on better terms than ever with our special friends.

Friday 2 July 1897

3.2 Cape Town

On 2 July we reached Cape Town and there kind Miss Bourne left us. The others who departed were a somewhat sordid-minded couple with a family of five nice boys; some Americans who were no special loss; and a young lady on the subject of whom speculations had been rife, and whose dress, flirtations, and guileless innocence, to say nothing of her pretty face, had been the amusement of all on board.

We afterwards heard she was an actress at the Variety Theatre at Johannesburg, and the last we saw of her was going off in a hansom with another not-to-be-regretted passenger—"a man with a history"—which, in his case, meant mostly—drink. However there were still two, {P18} if not three, dipsomaniacs left on board, and we took on a very ill-conditioned looking "crowd" at the Cape, so there was still come excitement.

One of the new passengers, a Mr. Musters, who had been in "Jameson's Raid"*, and was a very good sort, became our friend and joined the little circle in the corner of the library. The rest were no gain at all, and we could well have dispensed with a Scotch bagman and his wife, who made day and night hideous with their howls at the piano, and whose opinion of us was much what ours was of them.

[* The Jameson Raid (29 December 1895 - 2 January 1896) was a botched raid against the South African Republic (commonly known as the Transvaal) carried out by British colonial statesman Leander Starr Jameson and his Company troops. Wikipedia.]

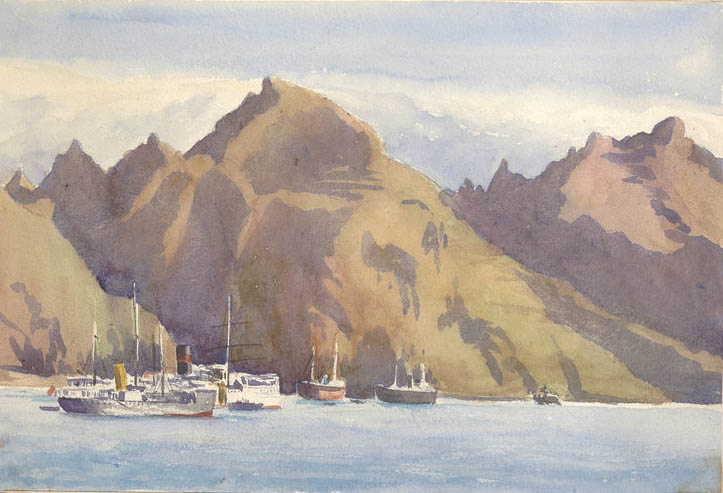

Table Bay, 2 July 1897, (C.A.N.)

On 2 July we woke up to find ourselves slowly steaming along the lovely African Coast with low lying purple hills, a glorious green blue sea, whales at intervals and flights of the most charming birds, among whom we saw, for the first time, the sweet little chequered cape pigeon.

Sunset, Table Bay, 2 July 1897, [E.L.N.]

Sunset, Table Bay, 2 July 1897, [C.A.N.]

We painted hard all we could, but we moved so fast it was difficult. Table Bay and Mountain are very fine {P19} and the harbour was full of lovely sailing ships, and some picturesque old hulks showed green in the green water. All along the jetty myriads of birds sat in black and white rows, but we passed everything so quickly one could not take in all one saw.

The tender with the mail was a welcome sight and we shouted enquiries to a sailor, as to how the Jubilee had gone off in England, in a way that seemed to astonish him.

We heard there of the loss of the Aden* and the death of Barnato**, not much else. Mr. Buxton got a wire to say he was 1st in 1st class in his Tripos, so someone was happy at any rate. As for Charlie and me, we bundled on shore as fast as we could, as there were not more than four hours before the ship started.

[* Wreck of the Aden. See Papers Past.]

[** Barney Barnato, born Barnet Isaacs, was a British Randlord, one of the entrepreneurs who gained control of diamond mining, and later gold mining, in South Africa from the 1870s. He is perhaps best remembered as being a rival of Cecil Rhodes. Wikipedia.]

Charlie was in great woe, and desired beyond everything to return straight to England, but he seemed to have recovered his spirits again when I met him later on at the bank, where I had gone with Mrs. Cohen, as she did not care to go alone.

{P20}

The "blacks," of whom we saw many on the wharf, are, some of them, most repulsive looking, others rather fine men. In Cape Town there are people of every shade of colour. Some of the old Malay women are rather picturesque, and the children quite pretty-looking. Beyond a gay coloured crowd of niggers round some fishing boats on the beach, I saw nothing really picturesque at Cape Town, which is the most squalid looking place I ever saw; miserable shanties jumbled up with pretentious and awful buildings, in the most degraded styles.

The "Cathedral" is a box-like building with square windows, only one of which was good. It possessed high pews and the fittings overall were awful. However, we were glad to be in a church again and also, later on, to see some real green grass in the Botanical Gardens, where we sat for a little time and looked at the bare English oaks and some poinsettias and clumps of narcissus and forgot, or pretended to, all the discomforts of the voyage. We also enjoyed having a meal to ourselves again and altogether felt better (n.b. C. had some beer!).

{P21}

The Nixons, from whom we had had a kind letter, were out when we called, so we returned to the town and had some tea. We met Mrs. Cohen in tears because she had lost her children, but they were soon afterwards found by Mr. Inman. We only just got to the tender in time, as our cabby went to the wrong wharf, but soon found ourselves on the ship again listening to the experiences of our friends and struggling hard to paint the effect on the mountains of one of the most lovely sunsets I have ever seen.

We moved out of the harbour only too soon with the sunset glow lingering for long after the sun had set and a little crescent new moon hanging in the crimson for a good omen for the next three weeks. They passed very quickly indeed. It was cold and wet, and we had some days when the ship rolled heavily all the time, others when she pitched, and a good many on which we were glad to stay in the library with rugs and I, for my part, slept more than ever in my life before.

Two days off the Cape we passed the largest shoal of porpoises anyone on board had ever seen. {P22} It was more than a mile long, and the sea seemed literally alive with the dear things all jumping in rows and looking the happiest of living things. We had one or two lovely days then one when, all unprepared, we sat or lay on deck as usual and there came a great wave and down went Charlie's drawing things, just rescued in time by Mr. Musters and, after a good deal of laughing and shrieking and scrambling, everyone (no one got wet) moved their chairs to a safer place and tried to forget how we were rolling.

I had two bad falls that day, [one] on the slippery deck and the next, when Charlie's instruments and all the loose chairs were sliding up and down the library. He got a bad bang on his head from a pillar coming towards him and I had to strap him up with plaster. Several people had bad falls and much china was broken those days. Mrs. Gannule told me the ship had been at an angle of thirty-eight degrees which, in such a monster, rolling slowly, is not a pleasant position.

{P23}

Tuesday 20 July 1897

3.3 Hobart

We had a good many letters to write and plans to arrange etc., and the time went very quickly so that we came to 20 July and the low shores of the Derwent early that day, almost before we could realize the voyage was over. Hobart has a lovely harbour and is a most pretty old-fashioned looking town, dominated by the beautiful crags of Mount Wellington, all streaked with snow.

We had lunch on board and said farewell to most of the passengers but left the final goodbyes till we returned to see the Gothic off at four. Mrs. Cohen met her husband and went on shore to Hayley's Hotel, as did Mr. Evans and his brother (a poor consumptive man who had nearly died on board) and some other of the passengers. Mr. Mercer, a cheerful young Australian, Mr. Buxton and ourselves went to Heethome's Hotel, the latter coming with us in a cab.

It was nice to be on shore and I began to get an appetite at once and Charlie looked more cheerful than he had done for six weeks, though he was very depressed at finding we could not get on till the Thursday, nor possibly get to Sydney before Saturday 24th. We returned to the Gothic before any of her remaining passengers did, {P24} and watched them all returning by twos and threes. These violets* were some of a large quantity of most beautiful flowers Mr. Inman had had sent on board.

[* Two dried flowers are attached, with sticky tape, to this page of the diary.]

We had bought a cup (with "Love the Giver" on it) for Miss Headington, and a spoon, and presented them to her great satisfaction and amusement.

Mr. Hill-Trevor and Mr. Ward, having lingered to buy her a hat and a bun, were late and the big ship had begun to move slowly out of the wharf before they arrived, breathless. Their embarkation and that of Messrs Butler and Dudgeon, also left behind, was scarcely dignified.

We walked along the wharf exchanging last words with our friends and Charlie threw them some apples, then we left the Cohens and others and went right on to the end and waved and waved till our floating home swung slowly around in the bay, pouring out volumes of black smoke, and then seemed to shoot off and become a mere dot in no time. Mr. Inman's tall figure waving a pocket handkerchief on a stick, was the last we could distinguish. It was very pathetic altogether.

{P25}

We went back to tea with Mr. Buxton and then C. and I poked about a little, went into the cathedral, which is a somewhat cold looking building, but churchlike and well appointed, heard most part of Evensong, and then came back to our hotel where that night we slept the sleep of the just as much as was possible from the intense stillness and stationariness of everything.

The next day was rather rainy, but with gleams of sun. Mr. Buxton had dined with the Gormistons and found out we "ought to see" the Fern Tree Bower, a bit of tropical forest on the slopes of Mount Wellington, about five miles distant. So we four started and had a most lovely drive. The road wound slowly up through suburbs first, small cottages and villas with shingled roofs and bright gardens, then through more or less cultivated country and finally through bush: thick undergrowth of sheoak, wattle, tamarisk and other shrubs, with fringes of scarlet and white heaths and towering masses of gum trees, which, in Tasmania, are real giants, very different to any we saw in Australia.

{P26}

Everywhere the practice of ringing* is adopted, and we passed some large tracts of these skeleton trees, while other solitary specimens gleamed white through the surrounding foliage. All the way, lovely peeps of the harbour, river and surrounding hills, blue or purple under cloud shadows, greeted us at the turns of the road. Fern Tree Bower is, in itself, a sort of tropical tea garden and therefore a disappointment.

[* ringing, or ringbarking: the complete removal of a strip of bark from around the entire circumference of the trunk of a tree, which results in the death of the tree]

There is a tiny inn and a church on the same scale, and one or two wooden shanties, and one wooden house, also a gate with "To the Bower" on it. You proceed for about a quarter of a mile along a neat path with benches and tree ferns at regular intervals and you arrive, finally, at a clearing with more benches; a sort of cricket pavilion; a stream; two rows of tree ferns, neat and clean and looking like (as C. said) cigars with a tuft on the top; and an inscription put up by the municipality of Hobart. It looks like the grave of something, possibly poetry, for there is no sign of that, but I daresay it is a convenient spot for tea picnics.

Hobart and Mount Wellington, 20 July 1897, (C.A.N.)

Near Hobart, Fern Tree Inn, 21 July 1897, (C.A.N.)

{P27}

The woods are full of the flat fern opposite*. The indented sort is one side frond of a frond of tree fern. These are about six feet long when full grown. The highest tree fern at the Bower was thirteen feet, but we saw some really beautiful ones afterwards, after walking about half a mile along a rougher path into the forest. The gum trees are here most grand, with huge roots about sixteen feet or more in diameter, near the ground, towering up into the most fantastic shapes.

[* The specimen has been removed from the page, with only a vague impression remaining.]

After a clearing of dead giants, we came into a dense forest, oh so damp, and dripping and mossy, and looked down from the raised path, down the hill into a tangle of tree ferns and gum tree roots and stems, which must have looked the same for centuries. (Plenty of living poetry here.)

Tasmanian Heather, Berries and Fungi, 21 July 1897

The dead tree ferns have fallen on one another and got matted together with creepers, so that you can't see where the ground is, while everywhere their huge fern leaves spread, and the upright plants (many of them have stems twenty feet high) carry ball-like heads of drooping leaves, as you see in an old palm, very different to the broom-like specimens in the Bower.

{P28}

We came round by a different way to the inn, where a curious meal of chops cheese, raspberry jam, cream, potatoes and tea had been prepared for us. On our return to Hobart Charlie and I went out and bade farewell to Mrs. Cohen and the Evanses, went to the end of evensong and finished up by doing a little shopping on the way home.

In the evening we all sat in a snug little room by a fire and Charlie, Mr. Mercer and Mr. Buxton, smoked and held forth on Australian politics. It was great fun.

Our train left at eight next morning and we were quite sorry to say goodbye to pretty English-looking Hobart. Tasmania is a lovely country but it strikes an English person as being dreadfully uncultivated and yet it is a garden compared with Australia. The railway took such sharp curves and kept one in such a state of agitation with jolts and bangs that I was quite surprised to arrive safely at Launceston.

3.4 Launceston, Tasmania

It is a somewhat squalid place, but we had only a few minutes to judge of it before our steamer, the Coogee, started and [there was] a great scrimmage to get the luggage. All the population and one individual in a top hat were occupied in staring at Lady Gormiston, which accounted for the fact that {P29} our luggage was left behind, as we found, at Melbourne. We enjoyed steaming down the Tamar in the lovely evening light, and watched the most glorious sunset as we emerged into Bass Straits.

Fern Tree Hollow, Tasmania, 21 July, 1897

Mount Wellington, Tasmania, from train, 22 July 1897

Launceston River (Tamar), July 22, 1897 (C.A.N.)

Bridgewater, Tasmania, 22 July 1897

Tamar River, W. Launceston, 22 July 1897

I had an amusing conversation with Mr. Buxton in the evening, re his family. He wanted us to come to lunch at Government House at Melbourne and see his father. We had a good crossing, slept pretty well, and fairly early came in sight of that most ugly place, Melbourne.

3.5 Melbourne, Victoria

We disembarked on a squalid wharf where I saw old Sir Fowell and we heard of Lady Brassey's accident. C. and I were not sorry to escape lunching there. Grief followed, as our baggage was not forthcoming, so after bidding a sad farewell to our two pleasant fellow travellers we went up to the office to telegraph, etc.

Melbourne is all huge offices and public buildings, built in what someone told me was the Scotch Gothic style (n.b. a very ugly style). Electric and cable trams tear up and down, busy men and dowdily dressed women jostle you rudely. Nowhere seemed there a rest for the sole of one's foot. I was especially struck with the {P30} mixture of squalor and splendour and the extremely frumpy style of the ladies' dresses.

Melbourne Cathedral is a very fine building, by Butterfield, with ghastly fittings by a local man. I sat there and rested some time. We also found a seat in the sun in a rather bare public garden and I nearly went to sleep on C.'s shoulder, I was so tired.

3.6 Albury, New South Wales

Our train left at four so we had some tea first and then, there being no room anywhere else, I stayed in the ladies' carriage with a young lady and a child, and C. hovered about between that and the smoking carriage. At Albury at 12 pm, on the frontier, we had to change. After that the line was broad gauge and less jolty; it was awful before.

We could only find room in a carriage with four men, but they were very kind, especially in the matter of all getting out by 3 a.m. and leaving us to get a little sleep at last. In the night we passed the remains of three bushfires, the stumps still smouldering. That was the only relief from the monotony of three hundred miles of gum trees—gum trees—gum trees—small and stunted, on bare brown ground, with here and there a clearing, and a few wooden houses and occasionally, a church.

{P31}

3.7 Sydney, New South Wales

The approach to Sydney by the railway is not imposing , but we were most delighted and thankful to get there about eleven, after passing through about ten miles of beadvertisemented [sic] suburbs. It was pouring with rain, much needed after a terrible drought. We settled ourselves in at the Grosvenor. Charlie went out to see Thomas and send off telegrams about the luggage, and I wrote letters and rested. Not much could I see of Sydney through the haze of rain.

Thomas Fenn came about 2 o'clock, and as he was most anxious to take us out, out we went, regardless of the pouring rain. We had only our journey clothes on, so did not care. I had various small purchases to make, owing to the lack of luggage, and we found only one shop still open, it being Saturday afternoon. Some of the warehouses and public buildings in Sydney are fine and solid looking, and the whole place has a much more established, and not such a mushroom look, as Melbourne. The streets are not wide. They are paved with cobbles. Omnibuses rattle over these.

Sydney

{P32}

In some streets your life is imperilled by steam trams, in others you find great comfort in the cable or electric trams. The traffic is not regulated by the police, but where the steam trams cross the cable ones, there is a signal post which is some slight comfort. Except for the corrugated iron verandahs to the shops, Sydney is an English looking place.

Sunday 25 July 1897

We woke early to find heavy rain still falling, and we puddled through the wet streets to the Cathedral to Early Service. We liked the Cathedral very much, though it is not such an imposing building as Melbourne and the windows are bad. There is also a dado of most terrible tiles, but it all felt homelike.

The service was performed in a somewhat slovenly manner, a good deal by the clerk! but we were too glad to be in a Church again to mind. We managed to get a cab, coming home. In the afternoon we energetically started for Ashfield (about 10 miles out) to see the Corlettes. We got an omnibus to the station at Sydney, but there was no cab at Ashfield Station and apparently no one knew where the Corlettes lived.

{P33}

One peculiarity of Australians is that, if they can't answer a question, they don't say so, but simply stare, and go on. After some wandering and many enquiries we saw the house in the distance and rushed up the path in a pouring shower of rain, certain that we were right by the appearance of an unmistakable Corlette in the doorway.

They received us very kindly and we promised to come and stay with them on Tuesday, if they would excuse our travelling clothes. We saw the whole family except the eldest son, who had gone to England. Miss Corlette drove us back in the buggy to the Station. It still rained.

We did some telephoning for the first time in our lives that evening, to Lady Manning, to whom I had written, and she promised to come to lunch on Tuesday. No, I remember it was Monday evening we telephoned. It is a strange sensation hearing a voice from five miles away [that] you last heard in England.

Monday 26 July 1897

On Monday morning C. went to see Pater's old House, now a convent, and other places with Thomas, and in the afternoon he took us to the University where we spent a most pleasant afternoon, in spite of the rain.

{P34}

A good deal of our time in Sydney was spent in various offices, re tickets, steamers, luggage etc. Also, we presented all the letters of introduction, [which] we brought.

On Monday morning C. also went by steamer to Manly, and saw the harbour and brought me back some lovely wild flowers, which I painted. He also called on Mrs. Knox, which she returned, finding me in.

Tuesday 27 July 1897

Tuesday morning we went to the Bank etc., and then looked up Mr. Statham, who was most kind and jolly. He took us in a little electric launch, across the Harbour to the Pastoral Produce Co.'s Warehouse and Refrigerating works, of which he is, I think, Consulting Engineer. It is a huge building. We went up in the lift to the top, passing floor after floor, some empty, some full of huge bales of "dumped" wool. Mr. Statham showed us the machinery where this was done, also the engine rooms where the ammonia freezing process causes the engines to be covered with snow. {P35} In several places a valve causes one side to be covered with snow, while the other is so hot you could not bear your hand on it.

We saw the huge condensers, and entered a small and arctic chamber where the snow lay in heaps and the temperature was about 26 degrees below freezing point. There is a huge store, where the sheep are frozen, after being run in along a rail at a certain height above the floor. There were about a thousand carcasses there, as hard as iron and giving back much the same sound when struck.

The view from the roof of the building is very fine, and I got a better idea of Sydney harbour than I ever did in any of our journeys up and down it. It was a brilliantly fine day, the water blue, and enough clouds to make effective shadows on the more distant hills. The shipping was most picturesque. Several fine boats, a P. & O., N. G. Lloyd, and other big liners, lay outside Circular Quay.

Sydney Harbour has a most wonderful number of small bays and inlets and could, I should think, accommodate all the fleets in the world. The effects at sunset are lovely, especially as the features one could dispense with, such as the numbers of {P36} villas that spoil the appearance of some of the most beautiful bays, are then veiled in a mysterious golden light.

Coral Tree, Sydney

We were a little disappointed after Hobart, in finding all the hills round Sydney Harbour so low, and no one striking feature, but possibly we had expected more than the beauties we did find in it, from the exaggerated accounts one reads, which are hardly applicable to any place on earth, certainly not to any place where there is a large population, and Nature is by no means left to herself.

SYDNEY, 27 JULY 1897

1. Christmas Bell

2. Garlic

3. Epacris

4. Flannel Flower

5. 6. 7. Baronias (sic)

Lady Manning came to lunch, and was very kind. She had not got into her house yet, but wanted us to come there on our return. She deprecated our going to the Corlettes, as she said we should not be comfortable. However we were, in an Australian way. They are most kind, and we liked them very much. Isabelle does wonders, but one sees the result of the real mistress of the house being "feckless" in the general muddle and impunctuality of everything. Mrs. Corlette is very fond of drawing and took a great interest in my efforts. I spent most of Wednesday morning painting.

{P37}

Dr. Corlette took Charlie [on] a ruridecanal* round, in the buggy, and I stayed at Ashfield and lazed and, in the afternoon, helped to entertain various ladies who came to tea. Dr. Corlette and Charlie, who mutually liked each other, stayed out so long that the good ladies only had a momentary glimpse of my better half, and I had to be extra amiable to make up.

[* Ruridecanal: A rural dean is a member of clergy who presides over a "rural deanery." "Ruridecanal" is the corresponding adjective for the term. Wikipedia.]

As a punishment, poor Charlie got bitten by the Corlettes' horse, "Charlie," a waler* of uncertain temper. It did not graze the skin, but was a bad bruise for nearly a fortnight and needed a lot of rubbing and bandaging and commiseration on my part, as the poor dear could not use his arm.

[* Waler: An Australian breed of riding horse. Wikipedia.]

At the Corlettes, as in most Australian houses, you are drinking some hot beverage or other all day long, viz. seven times. Tea before breakfast, tea or coffee at breakfast, cocoa in the middle of the morning, tea at lunch, tea at tea, tea at dinner, and cocoa before going to bed.

Strelizia, Ashfield

Isabelle drove us to the station next morning and we had a certain amount of business to do before going to tea with Mrs. Tregarthen, Lady Manning's daughter, with whom she was staying in Rose Bay.

{P38}

In answer to telegram news [that] had come that the luggage had been sent on by ship and would be at Sydney on Friday, for which piece of calm stinginess Charlie sent the Shaw Savill Co. at Melbourne a letter which must have been rather unpleasant to receive. By their carelessness and delay we had missed the fast boat to Rockhampton and had to put up with a little coasting boat (A.U.S.N. Co.), the Eurimbla, leaving on Saturday at 2 p.m.

Rose Bay is a very pretty part of Sydney, as we saw, from Mrs. Tregarthen's, Pater's old House, Lindsay, in a lovely position with garden down to the water's edge. There are houses all the way to Rose Bay, now.

Friday 30 July 1897

The luggage arrived early, and we spent nearly all the morning repacking it. Mr. Thomas Knox came to call, and was very kind, giving us two letters of introduction; one, to Mr. Walsh at Brisbane, and one to Mr. Hamilton Turner at Rockhampton, both also in Dalgetys. (n.b. Mr. Moore is the head of the Shaw Savill Dept. of Dalgetys in Sydney).

After lunch we went out and did a great deal of business. In the morning we had gone to a little opal shop where I bought four, and also plunged in the way of being {P39} photographed at the celebrated Crown Studios. We got our tickets, money, letters etc., also bought some charming toys for Thomas' children, and then started, somewhat late, by the 4 o'clock steamer for Coogee. So I saw the harbour with the advantage of the sunset light, and did some little sketches of the Heads etc. on the way.

SCENES AROUND SYDNEY

Manly Ocean Beach, 30 July 1897

Sydney Heads, 30 July 1897

Pinchgut fort, 30 July 1897

Coogee is a small place with a big house, belonging to the Cardinal, a large number of provision shops and the Ocean Beach, a sandy shore where we sat and watched the sea as long as we dared. We then patronized the chief industry of the place, viz. the providing of teas, and just caught our steamer back nicely.

We were very happy, sitting in the half darkness, watching the numberless lights reflected in the water, especially so, as the next day we would really be off and near the end of our long journey.

We had unpacked the presents for Thomas and took them with the toys to his house after dinner, where we spent the evening with him, his wife and little boy (the other two children were in bed) to their great satisfaction. He has most excellent quarters, a large airy flat, the top Storey of the Bank of N.S.W.

{P40}

Saturday 31 July 1897

Saturday morning was spent in going to say good bye to Mr. Forsythe (of "Burns Phillip" etc.) and finishing up one or two little things and getting the luggage on board. Miss Corlette and the youngest girl, Jean, came to lunch and kindly accompanied us through a heavy shower of rain to the wharf, where we found Thomas awaiting us with a large bunch of violets for me.

4. The Return Voyage from Sydney to Rockhampton

4.1 Sydney, New South Wales

The Eurimbla did not take very long getting under way, and we were soon steaming down the harbour, I trying to draw everything as we passed.

SCENES AROUND SYDNEY

Pinchgut Fort, 31 July 1897

South Head, 31 July 1897

Sydney, from Harbour, 31 July 1897

Sydney Smoke, 27 July 1897

Ashfield, 28 July 1897

This little boat, on whom we spent many subsequent day, proved a comfortable and homelike place. Fortunately we had very fair weather, or we should not have got on so well, there being no sitting room except a tiny smoking room on deck, as one could not count the saloon which was just over the screw. There was no gallery round the companion where one could sit, as in the Coogee, which is one of Huddart Parker's boats.

The Eurimbla is an A.U.S.N. boat. Our cabin was of the tiniest, but on deck. The berths were hard and the drain from the wash-hand basin smelt, but for all that we liked the little boat very much.

{P41}

Her captain (Grahl) was a very nice cheery, untidy man with whom we soon made great friends. His great idea is his wife, of whom he is evidently very fond. We found out all this and heard all his history later on. He was always a especially kind to me, being a "Hampshire man" born at Portsmouth.

Charlie was not over well that first evening. Somehow, without being a bad sailor, he never is very well the first day or so on a ship and the whole time I was on the Eurimbla I felt seedy. I think it was the stuffiness and smells.

The sunset that evening was lovely. I tried to paint it to please Charlie, who could not draw, poor dear, his arm being in a sling. We sat side by side and watched the shore and were quite happy. We were never out of sight of land all that journey and sometimes came quite close.

I did a good many sketches all the way, but it is a monotonous coast, nothing but gum trees and sandhills alternately, and here and there distant blue mountains, but for the most part low hills.

{P42}

In all the 500 miles from Sydney to Brisbane we only passed four lighthouses (in the day time) and one village (on Sunday), no sign of any other human habitation. One does not wonder at the centres the towns become when one sees what immense tracts of wasteland separate them from one another.

Sunday 1 August 1897

Sunday was a somewhat heathen experience. There was a tall man dressed as a person with a long head, and still longer hair, and I wondered if he would have any sort of service, but it was a good thing he did not, as he was probably a Baptist, as they all dress alike out here.

There were some nice people on board, a Mr. and Mrs. Bethell and her brother. She had travelled a good deal and I found a good many subjects of interest in common with her. They kindly lent us some papers on Sunday afternoon and Charlie spent some time asleep on a bench, where I covered him up and sat by him.

Monday 2 August 1897

4.2 Brisbane, Queensland

Next day, the coast was very uninteresting and flat, hardly any blue hills. Brisbane River is full of curious buoys and landmarks which the gulls consider their special property and on which they sit in rows. It was dark when we got in and [we] could only see by the lights, that it is a largish place.

{P43}

We were a long time getting birthed and were very glad to get onshore and walk up to our hotel, The Imperial, where, after some tea etc., we went to bed. It was much warmer here and we saw several people in white dress as we came up the main street, while in Sydney they are still in very winterly clothes.

Brisbane is difficult to describe, as it did not impress us in any way. There is so little of it and yet it is large. The post office is a fine building, with arcades and a flavour of the Uffizzi about it. We found some dear letters awaiting us, of which we were very glad.

We had pretty well made up our minds in many long talks on the Eurimbla, to go by the Tongariro on 2 September or, at any rate, try to, and risk staying in New Zealand if we missed—all this if a fortnight sufficed us at Rockhampton.

Tuesday 3 August 1897

We had had so much cold water thrown on the whole thing in Sydney, where everyone considers Rockhampton a sort of inferno, that I should have stayed behind if we had not both been rather miserable at the idea. Mr. Statham, however, had told us it was all right there now, and so did Mr. Walsh, whom we duly called on, on Tuesday morning, and found most kind and pleasant.

{P44}

It was hot, and so glary, we both found our black spectacles necessary. We called on Mr. Bland (head of the A.U.S.N in Brisbane) and Mr. Forrest. The latter was out, but subsequently telephoned his regret at missing us. We heard at the wharf that our tiresome boat did not leave till 8 p.m, this being a great blow to our worthy skipper, as we thereby missed all the good tides.

Charlie and I then found the cathedral, a small church with iron pillars and, what was far more interesting, the museum where there is a really splendid natural history collection. We saw some of our old friends the porpoises; some swordfish; a Tasmanian devil, which is a harmless looking beast though very ugly; whole families of kangaroos; opossum; wallabies; and other marsupials. There were a good many platypi, also fine specimens of fish, snakes, butterflies, all kinds of reptiles, and the most exquisite birds.

We recognised our dear friends the albatross, of whom we had seen many after {P45} the Cape, grand stately birds amid a crowd of molly hawks, cape pigeons, and seagulls, but lost our hearts completely to the funeral cockatoos, huge and black and fierce, with enormous plumes and a few scarlet or yellow feathers at the edge of the tail.

All the parrots were lovely. The two things that amused me most were a lizard with a frill and an animal I have never seen before, a wombat. Oh! So fat, all down the same size, legs and tail and all, something like Mab!

There is a good collection of minerals which also interested us. After lunch I had a good rest, it was so hot and tiring; and C. went out for a walk. His arm made him rather sad as he could do nothing.

We went out together later and had tea in a nice clean shop, then went on, and after looking at a lot of opals I bought one or two, before we returned to dinner.

Notwithstanding being on board in good time, we did not start till late so, after sitting on deck and talking a bit, we went to bed.

{P46}

Wednesday 4 August 1897

All Wednesday morning we were going through Sandy Straits* where a narrow channel of deep water runs between sandbanks. The Straits are formed by Fraser island, a Long island covered with gum and other trees, and mangrove swamps along the coast.

[* Now called "Great Sandy Strait."]

Here and there we saw pelican and crane. The island is named after Fraser, who was shipwrecked there with his wife. He was killed by the aborigines and eaten, but Mrs. Fraser lived among them for three years, at the end of which time she was rescued by some escaped convicts, who she afterwards rewarded by denouncing them to the authorities! I hope she was not an Englishwoman. Beyond a horse station, established there by some Englishman, the island is only inhabited by "blacks."

4.2a Maryborough, Queensland

In the afternoon we reached Maryborough, after steaming slowly up seven miles of the Mary River. As the ship did not leave again till ten, we had plenty of time to see all there is to be seen at Maryborough, which does not take long. There is a post office; two or three dreadful edifices called churches, of which the RC is the worst; a long wide street with verandahs; a few shops; and innumerable public houses and restaurants.

{P47}

We had tea in one of these, but they looked shocked when we asked for ices, which were advertised in the window, as, though very hot, it was winter time.

We saw some shockingly scurrilous democratic papers outside a bookseller, which made us feel angry, and yet sorry that these benighted people should be fed on such trash and have no chance of better.

The great thing at Maryborough is the garden, a lovely place on the river bank planted with palms bolinieas, bougainvilleas and masses of bamboo, towering up to quite forty feet. The flowering shrubs were in full beauty and we sat in the shade and much enjoyed ourselves.

"Bauhinia" from Maryborough, 5 August 1897

C. lay on the grass, which is of rather a dusty nature. The ground falls very prettily into several sorts of basins, which are taken the best advantage of, and well planted. We came back two hours late for dinner, but returned again to the garden to sit in the moonlight till it was time to go back and turn in, before the ship at last started.

Thursday 5 August 1897

4.3 Gladstone, Queensland

Thursday the coast was very dull, low hills and mangrove swamps, all the way. We got to Gladstone at about 4 o'clock. {P48} That is to say, we got to a rough pier ending in a causeway, built up over the swamp, at the end of which we could see a chimney. The town is four miles inland. This is the meatworks. It is a place which is supposed to be going to supersede Rockhampton, but to our eyes looked like Martin Chuzzlewit's Eden*.

[* Mark Tapley accompanied Martin Chuzzlewit when Martin went to the United States to seek his fortune. The two men attempted to start new lives in a swampy, disease-filled settlement named Eden, but both nearly died of malaria. Wikipedia]

We went on shore, but I don't think I should have done so, if I had had any idea what a mangrove swamp was like. These ghastly looking trees, with their high interlaced roots, all whitened with salt, grow in thick black slime where nothing else will live. The smell was horrible and, but for finding a tiny plant of eucalyptus on the track, I think I should have gone back. Charlie smoked vigorously.

We emerged onto a salt pan, a white waste stretching on all sides, across which the causeway ran, and at length brought us to the meatworks.

There is a wooden post office on piles, two or three shanties on a bare hill, with a few scanty gum trees. Here and there a waler was trying to find something to eat. A curious conveyance with two rat-like horses waited to take passengers to the "town." Bones and ashes lay all about, and the smell was so insufferable that we beat a most cowardly retreat, without exploring further.

{P49}

4.4 Rockhampton, Queensland

We stopped about seven times in the course of the night, as the Fitzroy is a difficult river to navigate, in a thick fog. However, the morning light found us safely tied up to the wharf at Rockhampton and looking out one could see little white wooden houses along the bank and high hills.

We slept again till the steward informed us Mr. Mawdsley was asking for us. It was raining, but he had slept the night before at the hotel in order to meet us. We dressed quickly and went on shore, a cab taking us and our possessions to the Criterion Hotel, a substantial stone building with deep verandahs and loggia over, where we had a bed and dressing room (opening out of one another and onto the loggia) and where A. Mawdsley stayed to breakfast with us, before taking C. out to show him round.

Rockhampton, 10 August 1897, (C.A.N.)

Rockhampton is by far the prettiest place we saw in Australia. The hills are such lovely shapes with deep blue coombes in them. They sunsets and early morning effects are glorious. It is not prejudice, though possibly our knowing so much about it all, {P50} and feeling more or less at home there, had something to do with our liking it so much.

Sydney is so un-English really, and yet so unlike a foreign place that we felt altogether fish out of water there, but Rockhampton is so thoroughly colonial, with its wooden houses built on piles, its gardens, hills and woods, and we entered so much more into the colonial manner of life, that we could feel it to be a new experience and enjoy it accordingly.

Charlie, of course, was quite happy having plenty to do at last, and his arm got all right very soon. Almost every day he bicycled somewhere with Mr. Blain, to look at the land, and spent much time in the office and seemed soon to grasp the situation completely.

Friday 13 August 1897

We stayed at the hotel till Wednesday the 11th and were very comfortable there. On Friday, the day we arrived, Mr. C. Thomson came to lunch and I went out with C. in the evening and saw A. M.'s office and also Isabella, who came in to fetch him.

Saturday 14 August 1897

On Saturday, Miss Rees Jones called on me in the morning and Mrs. Mawdsley came to lunch. C. went to see Mr. Thomson off in the morning and met Mr. Archer and Mr. Meacham. Mr. Reid was away. C. had been made a member of the club for a month and used to see people there occasionally.

{P51}

Sunday 15 August 1897

On Sunday I did not go to church in the morning. Mr. and Mrs. Fergusson came to see me, both in great grief at not having known before and wanting to carry us off there at once. However, I told them the Mawdsleys expected us first. I arranged to go for a drive next day. They were very kind.

The weather was so hot that I was only comfortable in white but the inhabitants went about saying the wind was cold. However, on Wednesday that dropped, and they allowed that it was warm, even very warm, towards the end of our stay. They have had practically no winter this year.

The moon was lovely every night and we tried our best to paint sunsets. I went to part of the evening service with C. on Sunday. The cathedral looks as if it was built of cardboard and as if a good wind would blow it away. The only really substantial thing in it is the reading desk!

The man who took the service had a fine voice. The choir evidently considered they had too, and proceeded at their own sweet will, {P52} half a note ahead of the organ all the time. It did not much matter, as the organist was not particular and played wrong notes in the non-vocal portions of the service.

Monday 16 August 1897

On Monday afternoon I went on a long drive with Mrs. Fergusson and her daughter, Mrs. Sydney Jones. We started along the road up the river, went round by the jail and Mrs. E. V. Reid's house, along the ridge to the south of the town, past the residences of the elite (n.b. except the Fergussons, all are of wood with corrugated iron roofs) and returned through the town and a little way along the road, down the river.

From the ridge you have a magnificent view across the lagoons to the south, a wide tract of country, mostly uninhabited, with grand Hills in the distance. None, however, are so beautiful as the three to the north of the river, Mounts Berserker, Archer and Nicholson, especially the second.

Mounts Nicholson and Archer, Rockhampton

Mount Nicholson, Rockhampton

From the ridge, the town of Rockhampton reminded me of nothing so much as a brickfield, the acres of corrugated iron roofs being only occasionally varied by larger buildings. Of these, the post office is by far the best, a graceful looking building with pillars and arched verandahs.

{P53}

Tuesday 17 August 1897

On Tuesday afternoon, just as I was setting out with Minnie Mawdsley, for a drive in their buggy, came Mrs. Blain, an old Scotch lady, who seemed to think three quarters of an hour the regulation length for a visit. On the two occasions when I saw this most excellent person, what chiefly impressed me was her evident desire to talk on what she considered my subjects. Consequently we discoursed on the "very best" society. The Baroness Burdett-Coutts was quite the least exalted person mentioned.

When she asked me what I thought of the fashions out here, I was quite at a loss and merely exclaimed, "are there any?" The good soul was evidently quite satisfied with the date of the mode of her best black silk.

Wednesday 18 August 1897

The next day, having had various callers, I went by myself in a covered buggy, to return them. This calling amused me very much. It is the one thing the ladies of Rockhampton have to do, and it is evidently a high crime and misdemeanour not to be very particular about it. There are difficulties however. [In the] first place the roads {P54} would not be called roads in England. Even the main thoroughfares are so terribly up and down that I always came back from a drive feeling like a jelly. The other roads are mere tracks, where the trees have been cleared. Here and there it has been too much trouble to grub a stump and it stands in the middle of the road, a foot or so high. Here and there the "road" goes across a creek, down one side, bump, bump, up the other, at an angle of about 30 [degrees].

I never quite made up my mind whether I preferred being on the celestial or terrestrial side on these occasions. Ruts, of course, are a mere nothing. What the horses are made of, that they don't shy, I cannot think. Their nerves are considerably better than mine as, on a moonlight night, a weird white gum stump (all the trees are white gums, and very ugly they are) six feet high, with just room between it and a hole for you to pass, if you have luck, used to make me even feel nervous.

Those people who have no roads to their house, (like Mr. Hamilton Turner), {P55} but where you drive over the downs, with its short dusty grass, wherever there are least hummocks, are the best off. Then too, having drawn up on a slope and the carriage having got through the gate, the family horse, which is walking about the drive, may chance to think it would like to get through too, and some delay occurs before it is induced to change its mind.

All the houses are built on high posts, to keep off the white ants, and a flight of steps leads you into the verandah. If the lady is at home the house door is open, and a bell generally stands on a bracket, which she as often as not answers herself. Some of the houses are very pretty and cosy and English-looking. Some are most untidy, like one place where I called and thought I had got into a chicken yard by mistake. There was rabbit wire all round, ashes and bones strewn everywhere, not a flower or green leaf, and such a funny shanty-like house, all closed up, as the lady was out.

Some of the houses have lovely creepers, but most people are afraid of these, on account of the snakes.

{P56}

I called on Mrs. E. V. Reid, Mrs. Sandford Wills, Mrs. Dove, Mrs. Fergusson, Mrs. Sydney Jones and Mrs. Allen, besides those I have mentioned, while at Rockhampton and C. called on Captain Hunter.

On Wednesday we began a delicious, free, open-air existence with the Mawdsleys, with whom we stayed till the following Tuesday. They do everything for themselves and we helped them as much as they would let us. It all reminded me of our life at Alassio.

The delight of having no servants sleeping in the house, no one can imagine who has not tried it. Out there in the bush it is so safe that they never lock up anything, not even the doors of the ground floor rooms, kitchen, store and dining rooms. One night we went out possum shooting, the dogs in a wild state of excitement. None were shot, however, that night, though Charlie and A. Mawdsley brought back one, another evening.

The moonlight was lovely and the creek was delicious at night, to all but one's nose, for there were skeletons of dead beasts everywhere and here and there a carcase, not yet finished up by the birds of prey.

{P57}

It is so curious, the bare brown grass and big boulders, and the shadeless gum trees, mixed up with shrubs and ti-trees, bush-apples, hibiscus here and there, white stumps or fallen trees—a most weird landscape.

It was very hot in the day time. One day when I went out and caught some of the gorgeous butterflies, (which I let loose again, n.b.) I nearly got sunstroke.

The birds were exquisite—several kinds of hawks and kites, magpies, parrots green and pink, the sweetest little tree creepers, wrens and finches—these were common and so tame.

Then there were the soft gentle-looking black and white butcher birds with the curious cry; the laughing jackasses whose insane cackle seems to go on all day sometimes, and once I saw one of the exquisite little bee-eaters, a wonder of blue and golden glories.

On Sunday, when there was a new "bush violet" in the creek, I saw, among other curious birds, the king hawk, a grand bird which Mr. Inman pointed out to me. He came to see us, but missed Charlie, who had gone on a long walk with the two Mawdsleys, (Harry having come down from {P58} Mt. Morgan on Saturday) attired in very little besides a pith hat. However, they were none to cool. Charlie came back enchanted with the wild beauty of the hills, but oh the heat! He went to see Mr. Inman twice and got me two opals.

On Thursday we had a long lovely day on the river. Charlie and I, Archibald and Minnie Mawdsley, and Mr. Schmidt of the Harbour Board, and his sister, were the party.

We went about thirty miles down the river in the H.B.* steam launch to Broadmount, where a pier, a hotel, and a station Master's house, form the nucleus of a new town.

[* Harbour Board.]

We saw a good many crane and one porpoise, but no alligators, which was a great disappointment. Mr. Schmidt afterwards gave me a crocodile's egg which, with sixty-six others, he had got out of a large nest on the river bank.

Fitzroy River, Rockhampton

Friday, Charlie was busy so I stayed in and painted and in the afternoon went with Isabella to see kind old Mrs. Fergusson in her big upholstery house. There was a "crowd" playing tennis who all stared, but we excused ourselves and so avoided being delayed, and [having] an inventory of my clothes taken by the Rockhampton ladies.

{P59}

Charlie missed his way that night and Isabella and I waited a long time for him, but got so eaten by mosquitoes we had to return.

Saturday stands out in my memory as a typical Australian day, very hot. We went by train to Gracemere early and were met by Mr. C. Archer and driven to the house, which is what they call a slab house and is one of the oldest about. On three sides it is surrounded by the lake and the garden is exquisite though, owing to bad times, not well kept up now. It was an ideally lazy day, most of it spent in the cool verandah, covered with masses of thunbergia out in flower, part of it playing with Mrs. Archer's fat baby, and talking to her and her nice sister, Mrs. Allen, in her room. I do not know how many pipes Charlie smoked!

Mr. W. Archer was away, but his brother was very kind. They insisted on our taking away some native curios. Indeed, everyone was most kind in giving us things. Most of Sunday morning I spent talking to {P60} Mr. Inman in the verandah. It was a hot day, one could not sleep in the afternoon or breathe anywhere in the house, but it was very lovely. What must the heat be in the summer?

Harry Mawdsley did not return to the mine till Tuesday morning, on the afternoon of which day we left Grangemount, sadly, and went to Kenmore, the Fergusson's big house.

Grangemount, Rockhampton

Top: Mount Nicholson, Sunset

Bottom: Near Grangemount

I much enjoyed the three days we spent with those excellent and kind people whom we both liked. They are so much more simple than their surroundings. Our bedroom was a sumptuous apartment with a mosquito netted brass bed in the middle and an arched verandah all to ourselves on which, after the heat of the day, I walked with Charlie in my night dress and felt cool for the first time. All the rooms are big and the house is well adapted for the climate, with beautiful bathrooms.

On Thursday evening we drove back with A. Mawdsley and had dinner with them and a pleasant last evening, driving back in the dark to the town, where we got a cab on.

{P61}

Mr. and Mrs. Fergusson brought me down to our ship (the Eurimbla again) next day and Charlie met us there. Archibald and Mr. Rees Jones lunched with us at The Criterion and at 2 o'clock saw us off, as did also Mr. Schmidt and Mr. Blain.

Saturday 21 August 1897

4.5 Bundaberg, Queensland

I threw Archibald some of the lovely roses Mrs. Sydney Jones had given me, as we sheered off. Our journey back to Brisbane differed from the last, as we only stopped at Bundaberg, where we arrived on Saturday afternoon. The banks of the river are lined with plantations of cane and there is a huge sugar mill at the wharf, where we stopped.

Rockhampton Hills, from River, 12 August

1897

Fitzroy River, at Sunset, 10 august 1897

Maryborough Gardens

Bundaberg River, 21 August 1897