a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

The Angel of the Revolution:

George Griffith:

eBook No.: 0602281h.html

Language: English

Date first posted: Jun 2006

Most recent update: Feb 2021

by

George Griffith

"The Angel of the Revolution,"

Tower Publishing Co. Ltd., London, 1893

"The Angel of the Revolution," Title Page

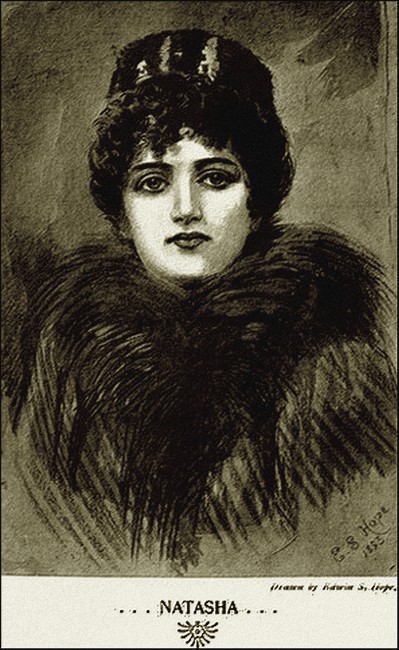

Frontispiece by Edwin S. Hope

"Victory! It flies! I am master of the Powers of the Air at last!"

They were strange words to be uttered, as they were, by a pale, haggard, half-starved looking young fellow in a dingy, comfortless room on the top floor of a South London tenement-house; and yet there was a triumphant ring in his voice, and a clear, bright flush on his thin cheeks that spoke at least for his own absolute belief in their truth.

Let us see how far he was justified in that belief.

To begin at the beginning, Richard Arnold was one of those men whom the world is wont to call dreamers and enthusiasts before they succeed, and heaven- born geniuses and benefactors of humanity afterwards.

He was twenty-six, and for nearly six years past he had devoted himself, soul and body, to a single idea—to the so far unsolved problem of aerial navigation.

This idea had haunted him ever since he had been able to think logically at all—first dimly at school, and then more clearly at college, where he had carried everything before him in mathematics and natural science, until it had at last become a ruling passion that crowded everything else out of his life, and made him, commercially speaking, that most useless of social units—a one-idea'd man, whose idea could not be put into working form.

He was an orphan, with hardly a blood relation in the world. He had started with plenty of friends, mostly made at college, who thought he had a brilliant future before him, and therefore looked upon him as a man whom it might be useful to know.

But as time went on, and no results came, these dropped off, and he got to be looked upon as an amiable lunatic, who was wasting his great talents and what money he had on impracticable fancies, when he might have been earning a handsome income if he had stuck to the beaten track, and gone in for practical work.

The distinctions that he had won at college, and the reputation he had gained as a wonderfully clever chemist and mechanician, had led to several offers of excellent positions in great engineering firms; but to the surprise and disgust of his friends he had declined them all. No one knew why, for he had kept his secret with the almost passionate jealousy of the true enthusiast, and so his refusals were put down to sheer foolishness, and he became numbered with the geniuses who are failures because they are not practical.

When he came of age he had inherited a couple of thousand pounds, which had been left in trust to him by his father. Had it not been for that two thousand pounds he would have been forced to employ his knowledge and his talents conventionally, and would probably have made a fortune. But it was just enough to relieve him from the necessity of earning his living for the time being, and to make it possible for him to devote himself entirely to the realisation of his life-dream—at any rate until the money was gone.

Of course he yielded to the temptation—nay, he never gave the other course a moment's thought. Two thousand pounds would last him for years; and no one could have persuaded him that with complete leisure, freedom from all other concerns, and money for the necessary experiments, he would not have succeeded long before his capital was exhausted.

So he put the money into a bank whence he could draw it out as he chose, and withdrew himself from the world to work out the ideal of his life.

Year after year passed, and still success did not come. He found practice very different from theory, and in a hundred details he met with difficulties he had never seen on paper. Meanwhile his money melted away in costly experiments which only raised hopes that ended in bitter disappointment His wonderful machine was a miracle of ingenuity, and was mechanically perfect in every detail save one—it would do no practical work.

Like every other inventor who had grappled with the problem, he had found himself constantly faced with that fatal ratio of weight to power. No engine that he could devise would do more than lift itself and the machine. Again and again he had made a toy that would fly, as others had done before him, but a machine that would navigate the air as a steamer or an electric vessel navigated the waters, carrying cargo and passengers, was still an impossibility while that terrible problem of weight and power remained unsolved.

In order to eke out his money to the uttermost, he had clothed and lodged himself meanly, and had denied himself everything but the barest necessaries of life.

Thus he had prolonged the struggle for over five years of toil and privation and hope deferred, and now, when his last sovereign had been changed and nearly spent, success—real, tangible, practical success—had come to him, and the discovery that was to be to the twentieth century what the steam-engine had been to the nineteenth was accomplished.

He had discovered the true motive power at last.

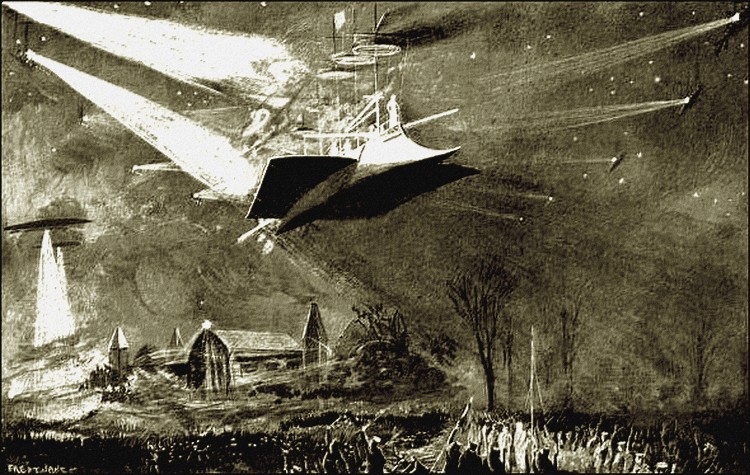

Two liquefied gases—which, when united, exploded spontaneously —were admitted by a clockwork escapement in minute quantities into the cylinders of his engine, and worked the pistons by the expansive force of the gases generated by the explosion. There was no weight but the engine itself and the cylinders containing the liquefied gases. Furnaces, boilers, condensers, accumulators, dynamos—all the ponderous apparatus of steam and electricity—were done away with, and he had a power at command greater than either of them. There was no doubt about it. The moment that his trembling fingers set the escapement mechanism in motion, the model that embodied the thought and labour of years rose into the air as gracefully as a bird on the wing, and sailed round and round in obedience to its rudder, straining hard at the string which prevented it from striking the ceiling. It was weighted in strict proportion to the load that the full-sized air-ship would have to carry. To increase this was merely a matter of increasing the power of the engine and the size of the floats and fans.

The room was a large one, for the house had been built for a better fate than letting in tenements, and it ran from back to front with a window at each end. Out of doors there was a strong breeze blowing, and as soon as Arnold was sure that his ship was able to hold its own in still air, he threw both the windows open and let the wind blow straight through the room. Then he drew the air-ship down, straightened the rudder, and set it against the breeze. In almost agonised suspense he watched it rise from the floor, float motionless for a moment, and then slowly forge ahead in the teeth of the wind, gathering speed as it went. It was then that he had uttered that triumphant cry of "Victory!" All the long years of privation and hope deferred vanished in that one supreme moment of innocent and bloodless conquest, and he saw himself master of a kingdom as wide as the world itself.

He let the model fly the length of the room before he stopped the clockwork and cut off the motive power, allowing it to sink gently to the floor. Then came the reaction. He looked steadfastly at his handiwork for several moments in silence, and then he turned and threw himself on to a shabby little bed that stood in one corner of the room and burst into a flood of tears.

Triumph had come, but had it not come too late? He knew the boundless possibilities of his invention—but they had still to be realised. To do this would cost thousands of pounds, and he had just one half-crown and a few coppers. Even these were not really his own, for he was already a week behind with his rent, and another payment fell due the next day. That would be twelve shillings in all, and if it was not paid he would be turned into the street.

As he raised himself from the bed he looked despairingly round the bare, shabby room. No; there was nothing there that he could pawn or sell. Everything saleable had gone already to keep up the struggle of hope against despair. The bed and wash-stand, the plain deal table, and the one chair that comprised the furniture of the room were not his. A little carpenter's bench, a few worn tools and odds and ends of scientific apparatus, and a dozen well-used books—these were all that he possessed in the world now, save the clothes on his back, and a plain painted sea-chest in which he was wont to lock up his precious model when he had to go out.

His model! No, he could not sell that. At best it would fetch but the price of an ingenious toy, and without the secret of the two gases it was useless. But was not that worth something? Yes, if he did not starve to death before he could persuade any one that there was money in it. Besides, the chest and its priceless contents would be seized for the rent next day, and then—

"God help me! What am I to do?"

The words broke from him like a cry of physical pain, and ended in a sob, and for all answer there was the silence of the room and the inarticulate murmur of the streets below coming up through the open windows. He was weak with hunger and sick with excitement, for he had lived for days on bread and cheese, and that day he had eaten nothing since the crust that had served him for breakfast. His nerves, too, were shattered by the intense strain of his final trial and triumph, and his head was getting light.

With a desperate effort he recovered himself, and the heroic resolution that had sustained him through his long struggle came to his aid again. He got up and poured some water from the ewer into a cracked cup and drank it. It refreshed him for the moment, and he poured the rest of the water over his head. That steadied his nerves and cleared his brain. He took up the model from the floor, laid it tenderly and lovingly in its usual resting-place in the chest. Then he locked the chest and sat down upon it to think the situation over.

Ten minutes later he rose to his feet and said aloud—

"It's no use. I can't think on an empty stomach. I'll go out and have one more good meal if it's the last I ever have in the world, and then perhaps some ideas will come."

So saying, he took down his hat, buttoned his shabby velveteen coat to conceal his lack of a waistcoat, and went out, locking the door behind him as he went.

Five minutes' walk brought him to the Blackfriars Road, and then he turned towards the river and crossed the bridge just as the motley stream of city workers was crossing it in the opposite direction on their homeward journey.

At Ludgate Circus he went into an eating-house and fared sumptuously on a plate of beef, some bread and butter, and a pint mug of coffee. As he was eating a paper-boy came in and laid an Echo on the table at which he was sitting. He took it up mechanically, and ran his eye carelessly over the columns. He was in no humour to be interested by the tattle of an evening paper, but in a paragraph under the heading of Foreign News a once familiar name caught his eye, and he read the paragraph through. It ran as follows:—

RAILWAY OUTRAGE IN RUSSIA

When the Berlin-Petersburg express stopped last night at Kovno, the first stop after passing the Russian frontier, a shocking discovery was made in the smoking compartment of the palace car which has been on the train for the last few months. Colonel Dornovitch, of the Imperial Police, who is understood to have been on his return journey from a secret mission to Paris, was found stabbed to the heart and quite dead. In the centre of the forehead were two short straight cuts in the form of a T reaching to the bone. Not long ago Colonel Dornovitch was instrumental in unearthing a formidable Nihilist conspiracy, in connection with which over fifty men and women of various social ranks were exiled for life to Siberia. The whole affair is wrapped in the deepest mystery the only clue in the hands of the police being the fact that the cross cut on the forehead of the victim indicates that the crime is the work not of the Nihilists proper, but of that unknown and mysterious society usually alluded to as the Terrorists, not one of whom has ever been seen save in his crimes. How the assassin managed to enter and leave the car unperceived while the train was going at full speed is an apparently insoluble riddle. Saving the victim and the attendants the only passengers in the car who had not retired to rest were another officer in the Russian service and Lord Alanmere, who was travelling to St. Petersburg to resume, after leave of absence, the duties of the Secretaryship to the British Embassy, to which he was appointed some two years ago.

"Why, that must be the Lord Alanmere who was at Trinity in my time, or rather Viscount Tremayne, as he was then," mused Arnold, as he laid the paper down. "We were very good friends in those days. I wonder if he'd know me now, and lend me a ten-pound note to get me out of the infernal fix I'm in? I believe he would, for he was one of the few really good-hearted men I have so far met with.

"If he were in London I really think I should take courage from my desperation, and put my case before him and ask his help. However, he's not in London, and so it's no use wishing. Well, I feel more of a man for that shillingsworth of food and drink, and I'll go and wind up my dissipation with a pipe and a quiet think on the Embankment."

When Richard Arnold reached the Embankment dusk had deepened into night, so far, at least, as nature was concerned. But in London in the beginning 7of the twentieth century there was but little night to speak of, save in the sense of a division of time. The date of the paper which contained the account of the tragedy on the Russian railway was September 3rd, 1903, and within the last ten years enormous progress had been made in electric lighting.

The ebb and flow in the Thames had at last been turned to account, and worked huge turbines which perpetually stored up electric power that was used not only for lighting, but for cooking in hotels and private houses, and for driving machinery. At all the great centres of traffic huge electric suns cast their rays far and wide along the streets, supplementing the light of the lesser lamps with which they were lined on each side.

The Embankment from Westminster to Blackfriars was bathed in a flood of soft white light from hundreds of great lamps running along both sides, and from the centre of each bridge a million candle-power sun cast rays upon the water that were continued in one unbroken stream of light from Chelsea to the Tower.

On the north side of the river the scene was one of brilliant and splendid opulence, that contrasted strongly with the halflighted gloom of the murky wilderness of South London, dark and forbidding in its irredeemable ugliness.

From Blackfriars Arnold walked briskly towards Westminster, bitterly contrasting as he went the lavish display of wealth around him with the sordid and seemingly hopeless poverty of his own desperate condition.

He was the maker and possessor of a far greater marvel than anything that helped to make up this splendid scene, and yet the ragged tramps who were remorselessly moved on from one seat to another by the policemen as soon as they had settled themselves down for a rest and a doze, were hardly poorer than he was.

For nearly four hours he paced backwards and forwards, every now and then stopping to lean on the parapet, and once or twice to sit down, until the chill autumn wind pierced his scanty clothing, and compelled him to resume his walk in order to get warm again.

All the time he turned his miserable situation over and over again in his mind without avail. There seemed no way out of it; no way of obtaining the few pounds that would save him from homeless beggary and his splendid invention from being lost to him and the world, certainly for years, and perhaps for ever.

And then, as hour after hour went by, and still no cheering thought came, the misery of the present pressed closer and closer upon him. He dare not go home, for that would be to bring the inevitable disaster of the morrow nearer, and, besides, it was home no longer till the rent was paid. He had two shillings, and he owed at least twelve. He was also the maker of a machine for which the Tsar of Russia had made a standing offer of a million sterling. That million might have been his if he had possessed the money necessary to bring his invention under the notice of the great Autocrat.

That was the position he had turned over and over in his mind until its horrible contradictions maddened him. With a little money, riches and fame were his; without it he was a beggar in sight of starvation.

And yet he doubted whether, even in his present dire extremity, he could, had he had the chance, sell what might be made the most terrific engine of destruction ever thought of to the head and front of a despotism that he looked upon as the worst earthly enemy of mankind.

For the twentieth time he had paused in his weary walk to and fro to lean on the parapet close by Cleopatra's Needle. The Embankment was almost deserted now, save by the tramps and a few isolated wanderers like himself. For several minutes he looked out over the brightly glittering waters below him, wondering listlessly how long it would take him to drown if he dropped over, and whether he would be rescued before he was dead, and brought back to life, and prosecuted the next day for daring to try and leave the world save in the conventional and orthodox fashion.

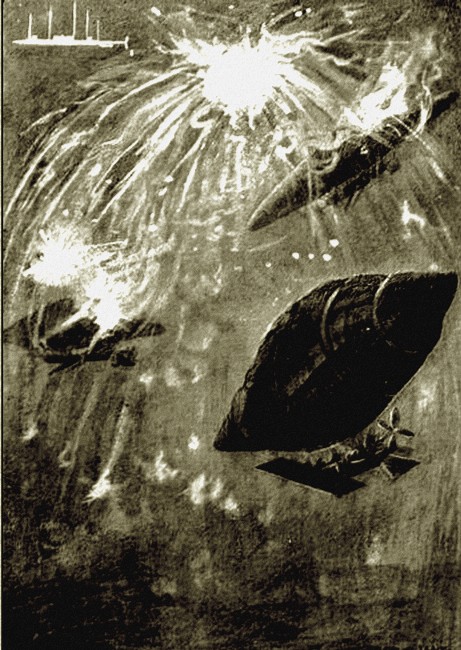

Then his mind wandered back to the Tsar and his million, and he pictured to himself the awful part that a fleet of airships such as his would play in the general European war that people said could not now be put off for many months longer. As he thought of this the vision grew in distinctness, and he saw them hovering over armies and cities and fortresses, and raining irresistible death and destruction down upon them. The prospect appalled him, and he shuddered as he thought that it was now really within the possibility of realisation; and then his ideas began to translate themselves involuntarily into words which he spoke aloud, completely oblivious for the time being of his surroundings.

"No, I think I would rather destroy it, and then take my secret with me out of the world, than put such an awful power of destruction and slaughter into the hands of the Tsar, or, for the matter of that, any other of the rulers of the earth. Their subjects can butcher each other quite efficiently enough as it is. The next war will be the most frightful carnival of destruction that the world has ever seen; but what would it be like if I were to give one of the nations of Europe the power of raining death and desolation on its enemies from the skies! No, no! Such a power, if used at all, should only be used against and not for the despotisms that afflict the earth with the curse of war!"

"Then why not use it so, my friend, if you possess it, and would see mankind freed from its tyrants?" said a quiet voice at his elbow.

The sound instantly scattered his vision to the winds, and he turned round with a startled exclamation to see who had spoken. As he did so, a whiff of smoke from a very good cigar drifted past his nostrils, and the voice said again in the same quiet, even tones—

"You must forgive me for my bad manners in listening to what you were saying, and also for breaking in upon your reverie. My excuse must be the great interest that your words had for me. Your opinions would appear to be exactly my own, too, and perhaps you will accept that as another excuse for my rudeness."

It was the first really kindly, friendly voice that Richard Arnold had heard for many a long day, and the words were so well chosen and so politely uttered that it was impossible to feel any resentment, so he simply said in answer—

"There was no rudeness, sir; and, besides, why should a gentleman like you apologise for speaking to a"—

"Another gentleman," quickly interrupted his new acquaintance. "Because I transgressed the laws of politeness in doing so, and an apology was due. Your speech tells me that we are socially equals. Intellectually you look my superior. The rest is a difference only of money, and that any smart swindler can bury himself in nowadays if he chooses. But come, if you have no objection to make my better acquaintance, I have a great desire to make yours. If you will pardon my saying so, you are evidently not an ordinary man, or else, something tells me, you would be rich. Have a smoke and let us talk, since we apparently have a subject in common. Which way are you going?"

"Nowhere—and therefore anywhere," replied Arnold, with a laugh that had but little merriment in it. "I have reached a point from which all roads are one to me."

"That being the case I propose that you shall take the one that leads to my chambers in Savoy Mansions yonder. We shall find a bit of supper ready, I expect, and then I shall ask you to talk. Come along!"

There was no more mistaking the genuine kindness and sincerity of the invitation than the delicacy with which it was given. To have refused would not only have been churlish, but it would have been for a drowning man to knock aside a kindly hand held out to help him; so Arnold accepted, and the two new strangely met and strangely assorted friends walked away together in the direction of the Savoy.

The suite of rooms occupied by Arnold's new acquaintance was the beau ideal of a wealthy bachelor's abode. Small, compact, cosy, and richly furnished, yet in the best of taste withal, the rooms looked like an indoor paradise to him after the bare squalor of the one room that had been his own home for over two years.

His host took him first into a dainty little bath-room to wash his hands, and by the time he had performed his scanty toilet supper was already on the table in the sitting-room. Nothing melts reserve like a good well-cooked meal washed down by appropriate liquids, and before supper was half over Arnold and his host were chatting together as easily as though they stood on perfectly equal terms and had known each other for years. His new friend seemed purposely to keep the conversation to general subjects until the meal was over and his pattern man-servant had removed the cloth and left them together with the wine and cigars on the table.

As soon as he had closed the door behind him his host motioned Arnold to an easy-chair on one side of the fireplace, threw himself into another on the other side, and said—

"Now, my friend, plant yourself, as they say across the water, help yourself to what there is as the spirit moves you, and talk—the more about yourself the better. But stop. I forgot that we do not even know each other's name yet. Let me introduce myself first.

"My name is Maurice Colston; I am a bachelor, as you see. For the rest, in practice I am an idler, a dilettante, and a good deal else that is pleasant and utterly useless. In theory, let me tell you, I am a Socialist, or something of the sort, with a lively conviction as to the injustice and absurdity of the social and economic conditions which enable me to have such a good time on earth without having done anything to deserve it beyond having managed to be born the son of my father."

He stopped and looked at his guest through the wreaths of his cigar smoke as much as to say: "And now who are you?"

Arnold took the silent hint, and opened his mouth and his heart at the same time. Quite apart from the good turn he had done him, there was a genial frankness about his unconventional host that chimed in so well with his own nature that he cast all reserve aside, and told plainly and simply the story of his life and its master passion, his dreams and hopes and failures, and his final triumph in the hour when triumph itself was defeat.

His host heard him through without a word, but towards the end of his story his face betrayed an interest, or rather an expectant anxiety, to hear what was coming next that no mere friendly concern of the moment for one less fortunate than himself could adequately account for. At length, when Arnold had completed his story with a brief but graphic description of the last successful trial of his model, he leant forward in his chair, and, fixing his dark, steady eyes on his guest's face, said in a voice from which every trace of his former good-humoured levity had vanished—

"A strange story, and truer, I think, than the one I told you. Now tell me on your honour as a gentleman: Were you really in earnest when I heard you say on the embankment that you would rather smash up your model and take the secret with you into the next world, than sell your discovery to the Tsar for the million that he has offered for such an air-ship as yours?"

"Absolutely in earnest," was the reply. "I have seen enough of the seamy side of this much-boasted civilisation of ours to know that it is the most awful mockery that man ever insulted his Maker with. It is based on fraud, and sustained by force—force that ruthlessly crushes all who do not bow the knee to Mammon. I am the enemy of a society that does nob permit a man to be honest and live, unless he has money and can defy it. I have just two shillings in the world, and I would rather throw them into the Thames and myself after them than take that million from the Tsar in exchange for an engine of destruction that would make him master of the world."

"Those are brave words," said Colston, with a smile. "Forgive me for saying so, but I wonder whether you would repeat them if I told you that I am a servant of his Majesty the Tsar, and that you shall have that million for your model and your secret the moment that you convince me that what you have told me is true."

Before he had finished speaking Arnold had risen to his feet. He heard him out, and then he said, slowly and steadily—

"I should not take the trouble to repeat them; I should only tell you that I am sorry that I have eaten salt with a man who could take advantage of my poverty to insult me. Good night."

He was moving towards the door when Colston jumped up from his chair, strode round the table, and got in front of him. Then he put his two hands on his shoulders, and, looking straight into his eyes, said in a tone that vibrated with emotion—

"Thank God, I have found an honest man at last! Go and sit down again, my friend, my comrade, as I hope you soon will be. Forgive me for the foolishness that I spoke! I am no servant of the Tsar. He and all like him have no more devoted enemy on earth than I am. Look! I will soon prove it to you."

As he said the last words, Colston let go Arnold's shoulders, flung off his coat and waistcoat, slipped his braces off his shoulders, and pulled his shirt up to his neck. Then he turned his bare back to his guest, and said—

"That is the sign-manual of Russian tyranny—the mark of the knout!"

Arnold shrank back with a cry of horror at the sight. From waist to neck Colston's back was a mass of hideous scars and wheels, crossing each other and rising up into purple lumps, with livid blue and grey spaces between them. As he stood, there was not an inch of naturally-coloured skin to be seen. It was like the back of a man who had been flayed alive, and then flogged with a cat- o'-nine-tails.

Before Arnold had overcome his horror his host had readjusted his clothing. Then he turned to him and said—

"That was my reward for telling the governor of a petty Russian town that he was a brute-beast for flogging a poor decrepid old Jewess to death. Do you believe me now when I say that I am no servant or friend of the Tsar?"

"Yes, I do," replied Arnold, holding out his hand, "you were right to try me, and I was wrong to be so hasty. It is a failing of mine that has done me plenty of harm before now. I think I know now what you are without your telling me. Give me a piece of paper and you shall have my address, so that you can come to-morrow and see the model—only I warn you that you will have to pay my rent to keep my landlord's hands off it. And then I must be off, for I see it's past twelve."

"You are not going out again to-night, my friend, while I have a sofa and plenty of rugs at your disposal," said his host. "You will sleep here, and in the morning we will go together and see this marvel of yours. Meanwhile sit down and make yourself at home with another cigar. We have only just begun to know each other—we two enemies of Society!"

Soon after eight the next morning Colston came into the sitting-room where Arnold had slept on the sofa, and dreamt dreams of war and world-revolts and battles fought in mid-air between aerial navies built on the plan of his own model. When Colston came in he was just awake enough to be wondering whether the events of the previous night were a reality or part of his dreams— a doubt that was speedily set at rest by his host drawing back the curtains and pulling up the blinds.

The moment his eyes were properly open he saw that he was anywhere but in his own shabby room in Southwark, and the rest was made clear by Colston saying—

"Well, comrade Arnold, Lord High Admiral of the Air, how have you slept? I hope you found the sofa big and soft enough, and that the last cigar has left no evil effects behind it."

"Eh? Oh, good morning! I don't know whether it was the whisky or the cigars, or what it was; but do you know I have been dreaming all sorts of absurd things about battles in the air and dropping explosives on fortresses and turning them into small volcanoes. When you came in just now I hadn't the remotest idea where I was. It's time to get up, I suppose?"

"Yes, it's after eight a good bit. I've had my tub, so the bath-room is at your service. Meanwhile, Burrows will be laying the table for breakfast. When you have finished your tub, come into my dressing-room, and let me rig you out. We are about of a size, and I think I shall be able to meet your most fastidious taste. In fact, I could rig you out as anything—from a tramp to an officer of the Guards."

"It wouldn't take much change to accomplish the former, I'm afraid. But, really, I couldn't think of trespassing so far on your hospitality as to take your very clothes from you. I'm deep enough in your debt already."

"Don't talk nonsense, Richard Arnold. The tone in which those last words were said shows me that you have not duly laid to heart what I said last night. There is no such thing as private property in the Brotherhood, of which I hope, by this time to-morrow, you will be an initiate.

"What I have here is mine only for the purposes of the Cause, wherefore it is as much yours as mine, for to-day we are going on the Brotherhood's business. Why, then, should you have any scruples about wearing the Brotherhood's clothes? Now clear out and get tubbed, and wash some of those absurd ideas out of your head."

"Well, as you put it that way, I don't mind, only remember that I don't necessarily put on the principles of the Brotherhood with its clothes."

So saying, Arnold got up from the sofa, stretched himself, and went off to make his toilet.

When he sat down to breakfast with his host half an hour later, very few who had seen him on the Embankment the night before would have recognised him as the same man. The tailor after all, does a good deal to make the man, externally at least, and the change of clothes in Arnold's case had transformed him from a superior looking tramp into an aristocratic and decidedly good- looking man, in the prime of his youth, saving only for the thinness and pallor of his face, and a perceptible stoop in the shoulders.

During breakfast they chatted about their plans for the day and then drifted into generalities, chiefly of a political nature.

The better Arnold came to know Maurice Colston the more remarkable his character appeared to him; and it was his growing wonder at the contradictions that it exhibited that made him say towards the end of the meal—

"I must say you're a queer sort of conspirator, Colston. My idea of Nihilists and members of revolutionary societies has always taken the form of silent, stealthy, cautious beings, with a lively distrust and hatred of the whole human race outside their own circles. And yet here are you, an active member of the most terrible secret society in existence, pledged to the destruction of nearly every institution on earth, and carrying your life in your hand, opening your heart like a schoolboy to a man you have literally not known for twenty-four hours.

"Suppose you had made a mistake in me. What would there be to prevent me telling the police who you are, and having you locked up with a view to extradition to Russia?"

"In the first place," replied Colston quietly, "you would not do so, because I am not mistaken in you, and because, in your heart, whether you fully know it or not, you believe as I do about the destruction that is about to fall upon Society.

"In the second place, if you did betray my confidence, I should be able to bring such an overwhelming array of the most respectable evidence to show that I was nothing like what I really am, that you would be laughed at for a madman; and, in the third place, there would be an inquest on you within twenty- four hours after you had told your story. Do you remember the death of Inspector Ainsworth, of the Criminal Investigation Department, about six months ago?"

"Yes, of course I do. Hermit and all as I was, I could hardly help hearing about that, considering what a noise it made. But I thought that was cleared up. Didn't one of that gang of garotters that was broken up in South London a couple of months later confess to strangling him in the statement that he made before he was executed?"

"Yes, and his widow is now getting ten shillings a week for life on account of that confession. Birkett no more killed Ainsworth than you did; but he had killed two or three others, and so the confession didn't do him very much harm.

"No; Ainsworth met his death in quite another way. He accepted from the Russian secret police bureau in London a bribe of £250 down and the promise of another £250 if he succeeded in manufacturing enough evidence against a member of our Outer Circle to get him extradited to Russia on a trumped-up charge of murder.

"The Inner Circle learnt of this from one of our spies in the Russian London police, and—, well, Ainsworth was found dead with the mark of the Terror upon his forehead before he had time to put his treachery into action. He was executed by two of the Brotherhood, who are members of the Metropolitan police force, and who were afterwards complimented by the magistrate for the intelligent efforts they had made in bringing the murderers to justice."

Colston told the dark story in the most careless of tones between the puffs of his after-breakfast cigarette. Arnold stifled his horror as well as he was able, but he could not help saying, when his host had done—

"This Brotherhood of yours is well named the Terror; but was not that rather a murder than an execution?"

"By no means," replied Colston, a trifle coldly. "Society hangs or beheads a man who kills another. Ainsworth knew as well as we did that if the man he tried to betray by false evidence had once set foot in Russia, the torments of a hundred deaths would have been his before he had been allowed to die.

"He betrayed his office and his faith to his English masters in order to commit this vile crime, and so he was killed as a murderous and treacherous reptile that was not fit to live. We of the Terror are not lawyers, and so we make no distinctions between deliberate plotting for money to kill and the act of killing itself. Our law is closer akin to justice than the hairsplitting fraud that is tolerated by Society."

Either from emotional or logical reasons Arnold made no reply to this reasoning, and, seeing he remained silent, Colston resumed his ordinary nonchalant, good-humoured tone, and went on—

"But come, that will be horrors enough for to-day. We have other business in hand, and we may as well get to it at once. About this wonderful invention of yours. Of course I believe all you have told me about it, but you must remember that I am only an agent, and that I am inexorably bound by certain rules, in accordance with which I must act.

"Now, to be perfectly plain with you, and in order that we may thoroughly understand each other before either of us commits himself to anything, I must tell you that I want to see this model flying ship of yours in order to be able to report on it to-night to the Executive of the Inner Circle, to whom I shall also want to introduce you. If you will not allow me to do that say so at once, and, for the present at least, our negotiations must come to a sudden stop."

"Go on," said Arnold quietly; "so far I consent. For the rest I would rather hear you to the end."

"Very well. Then if the Executive approve of the invention, you will be asked to join the Inner Circle at once, and to devote yourself body and soul to the Society and the accomplishment of the objects that will be explained to you. If you refuse there will be an end of the matter, and you will simply be asked to give your word of honour to reveal nothing that you have seen or heard, and then allowed to depart in peace.

"If, on the other hand, you consent, in consideration of the immense importance of your secret—which there is no need to disguise from you —to the Brotherhood, the usual condition of passing through the Outer Circle will be dispensed with, and you will be trusted as absolutely as we shall expect you to trust us.

"Whatever funds you then require to manufacture an airship on the plan of your model will be placed at your disposal, and a suitable place will be selected for the works that you will have to build. When the ship is ready to take the air you will, of course, be appointed to the command of her, and you will pick your crew from among the workmen who will act under your orders in the building of the vessel.

"They will all be members of the Outer Circle, who will not understand your orders, but simply obey them blindly, even to the death. One member of the Inner Circle will act as your second in command, and he will be as perfectly trusted as you will be, so that in unforeseen emergencies you will be able to consult with him with perfect confidence. Now I think I have told you all. What do you say?"

Arnold was silent for a few minutes, too busy for speech with the rush of thoughts that had crowded through his brain as Colston was speaking. Then he looked up at his host and said—

"May I make conditions?"

"You may state them," replied he, with a smile, "but, of course, I don't undertake to accept them without consultation with my—I mean with the Executive."

"Of course not," said Arnold. "Well, the conditions that I should feel myself obliged to make with your Executive would be, briefly speaking, these: I would not reveal to any one the composition of the gases from which I derive my motive force. I should manufacture them myself in given quantities, and keep them always under my own charge.

"At the first attempt to break faith with me in this respect I would blow the air-ship and all her crew, including myself, into such fragments as it would be difficult to find one of them. I have and wish for no life apart from my invention, and I would not survive it."

"Good!" interrupted Colston. "There spoke the true enthusiast. Go on."

"Secondly, I would use the machine only in open warfare—when the Brotherhood is fighting openly for the attainment of a definite end. Once the appeal to force has been made I will employ a force such as no nation on earth can use without me, and I will use it as unsparingly as the armies and fleets engaged will employ their own engines of destruction on one another. But I will be no party to the destruction of defenceless towns and people who are not in arms against us. If I am ordered to do that I tell you candidly that I will not do it. I will blow the airship itself up first."

"The conditions are somewhat stringent, although the sentiments are excellent," replied Colston; "still, of myself I can neither accept nor reject them. That will be for the Executive to do. For my own part I think that you will be able to arrive at a basis of agreement on them. And now I think we have said all we can say for the present, and so if you are ready we'll be off and satisfy my longing to see the invention that is to make us the arbiters of war—when war comes, which I fancy will not be long now."

Something in the tone in which these last words were spoken struck Arnold with a kind of cold chill, and he shivered slightly as he said in answer to Colston—

"I am ready when you are, and no less anxious than you to set eyes on my model. I hope to goodness it is all safe! Do you know, when I am away from it I feel just like a woman away from her first baby."

A few minutes later two of the most dangerous enemies of Society alive were walking quietly along the Embankment towards Blackfriars, smoking their cigars and chatting as conventionally as though there were no such things on earth as tyranny and oppression, and their necessarily ever-present enemies conspiracy and brooding revolution.

Twenty minutes' walk took Arnold and Colston to the door of the tenement- house in which the former had lived since his fast-dwindling store of money had convinced him of the necessity of bringing his expenses down to the lowest possible limit if he wished to keep up the struggle with fate very much longer.

As they mounted the dirty, evil-smelling staircase, Colston said—

"Phew! Verily you are a hero of science if you have brought yourself to live in a hole like this for a couple of years rather than give up your dream, and grow fat on the loaves and fishes of conventionality."

"This is a palace compared with some of the rookeries about here," replied Arnold, with a laugh. "The march of progress seems to have left this half of London behind as hopeless. Ten years ago there were a good many thousands of highly respectable mediocrities living on this side of the river, but now I am told that the glory has departed from the very best of its localities, and given them up to various degrees of squalor. Vice, poverty, and misery seem to gravitate naturally southward in London. I don't know why, but they do. Well, here is the door of my humble den."

As he spoke he put the key in the lock, and opened the door, bidding his companion enter as he did so. Arnold's anxiety was soon relieved by finding the precious model untouched in its resting-place, and it was at once brought out. Colston was delighted beyond his powers of expression with the marvellous ingenuity with which the miracle of mechanical skill was contrived and put together; and when Arnold, after showing and explaining to him all the various parts of the mechanism and the external structure, at length set the engine working, and the air-ship rose gracefully from the floor and began to sail round the room in the wide circle to which it was confined by its mooring-line, he stared at it for several minutes in wondering silence, following it round and round with his eyes, and then he said in a voice from which he vainly strove to banish the signs of the emotion that possessed him—

"It is the last miracle of science! With a few such ships as that one could conquer the world in a month!"

"Yes, that would not be a very difficult task, seeing that neither an army nor a fleet could exist for twelve hours with two or three of them hovering above it," replied Arnold.

The trial over, Arnold set to work and took the model partly to pieces for packing up; and while he was putting it away in the old sea-chest, Colston counted out ten sovereigns and laid them on the table. Hearing the clink of the gold, Arnold looked up and said—

"What is that for? A sovereign will be quite enough to get me out of my present scrape, and then if we come to any terms to-night it will be time enough to talk about payment."

"The Brotherhood does not do business in that way," was the reply. "At present your only connection with it is a commercial one, and ten pounds is a very moderate fee for the privilege of inspecting such an invention as this. Anyhow, that is what I am ordered to hand over to you in payment for your trouble now and to-night, so you must accept it as it is given—as a matter of business."

"Very well," said Arnold, closing and locking the chest as he spoke, "if you think it worth ten pounds, the money will not come amiss to me. Now, if you will remain and guard the household gods for a minute, I will go and pay my rent and get a cab."

Half an hour later his few but priceless possessions were loaded on a four-wheeler and Arnold had bidden farewell for ever to the dingy room in which he had passed so many hours of toil and dreaming, suffering and disappointment. Before lunch time they were safely bestowed in a couple of rooms which Colston had engaged for him in the same building in which his own rooms were.

In the afternoon, among other purchases, a more convenient case was bought for the model, and in this it was packed with the plans and papers which explained its construction, ready for the evening journey. The two friends dined together at six in Colston's rooms, and at seven sharp his servant announced that the cab was at the door. Within ten minutes they were bowling along the Embankment towards Westminster Bridge in a luxuriously appointed hansom of the newest type, with the precious case lying across their knees.

"This is a comfortable cab," said Arnold, when they had gone a hundred yards or so. "By the way, how does the man know where to go? I didn't hear you give him any directions."

"None were necessary," was the reply. "This cab, like a good many others in London, belongs to the Brotherhood, and the man who is driving is one of the Outer Circle. Our Jehus are the most useful spies that we have. Many is the secret of the enemy that we have learnt from, and many is the secret police agent who has been driven to his rendezvous by a Terrorist who has heard every word that has been spoken on the journey."

"How on earth is that managed?"

"Every one of the cabs is fitted with a telephonic arrangement communicating with the roof. The driver has only to button the wire of the transmitter up inside his coat so that the transmitter itself lies near to his ear, and he can hear even a whisper inside the cab.

"The man who is driving us, for instance, has a sort of retainer from the Russian Embassy to be on hand at certain hours on certain nights in the week. Our cabs are all better horsed, better appointed, and better driven than any others in London, and, consequently, they are favourites, especially among the young attaches, and are nearly always employed by them on their secret missions or love affairs, which, by the way, are very often the same thing. Our own Jehu has a job on to-night, from which we expect some results that will mystify the enemy not a little. We got our first suspicions of Ainsworth from a few incautious words that he spoke in one of our cabs."

"It's a splendid system, I should think, for discovering the movements of your enemies," said Arnold, not without an uncomfortable reflection on the fact that he was himself now completely in the power of this terrible organisation, which had keen eyes and ready hands in every capital of the civilised world. "But how do you guard against treachery? It is well known that all the Governments of Europe are spending money like water to unearth this mystery of the Terror. Surely all your men cannot be incorruptible."

"Practically they are so. The very mystery which enshrouds all our actions makes them so. We have had a few traitors, of course; but as none of them has ever survived his treachery by twenty-four hours, a bribe has lost its attraction for the rest."

In such conversation as this the time was passed, while the cab crossed the river and made its way rapidly and easily along Kennington Road and Clapham Road to Clapham Common. At length it turned into the drive of one of those solid abodes of pretentious respectability which front the Common, and pulled up before a big stucco portico.

"Here we are!" exclaimed Colston, as the doors of the cab automatically opened. He got out first, and Arnold handed the case to him, and then followed him.

Without a word the driver turned his horse into the road again and drove off towards town, and as they ascended the steps the front door opened, and they went in, Colston saying as they did so—

"Is Mr. Smith at home?"

"Yes, sir; you are expected, I believe. Will you step into the drawing- room?" replied the clean-shaven and immaculately respectable man-servant, in evening dress, who had opened the door for them.

They were shown into a handsomely furnished room lit with electric light. As soon as the footman had closed the door behind him, Colston said—

"Well, now, here you are in the conspirators' den, in the very headquarters of those Terrorists for whom Europe is being ransacked constantly without the slightest success. I have often wondered what the rigid respectability of Clapham Common would think if it knew the true character of this harmless-looking house. I hardly think an earthquake in Clapham Road would produce much more sensation that such a discovery would.

"And now," he continued, his tone becoming suddenly much more serious "in a few minutes you will be in the presence of the Inner Circle of the Terrorists, that is to say, of those who practically hold the fate of Europe in their hands. You know pretty clearly what they want with you. If you have thought better of the business that we have discussed you are still at perfect liberty to retire from it, on giving your word of honour not to disclose anything that I have said to you."

"I have not the slightest intention of doing anything of the sort," replied Arnold. "You know the conditions on which I came here. I shall put them before your Council, and if they are accepted your Brotherhood will, within their limits, have no more faithful adherent than I. If not, the business will simply come to an end as far as I am concerned, and your secret will be as safe with me as though I had taken the oath of membership."

"Well said!" replied Colston, "and just what I expected you to say. Now listen to me for a minute. Whatever you may see or hear for the next few minutes say nothing till you are asked to speak. I will say all that is necessary at first. Ask no questions, but trust to anything that may seem strange being explained in due course—as it will be. A single indiscretion on your part might raise suspicions which would be as dangerous as they would be unfounded. When you are asked to speak do so without the slightest fear, and speak your mind as openly as you have done to me."

"You need have no fear for me," replied Arnold. "I think I am sensible enough to be prudent, and I am quite sure that I am desperate enough to be fearless. Little worse can happen to me than the fate that I was contemplating last night."

As he ceased speaking there was a knock at the door. It opened and the footman reappeared, saying in the most commonplace fashion—

"Mr. Smith will be happy to see you now, gentlemen. Will you kindly walk this way?"

They followed him out into the hall, and then, somewhat to Arnold's surprise, down the stairs at the back, which apparently led to the basement of the house.

The footman preceded them to the basement floor and halted before a door in a little passage that looked like the entrance to a coal cellar. On this he knocked in peculiar fashion with the knuckles of one hand, while with the other he pressed the button of an electric bell concealed under the paper on the wall. The bell sounded faintly as though some distance off, and as it rang the footman said abruptly to Colston—

"Das Wort ist Freiheit."

Arnold knew German enough to know that this meant "The word is 'Freedom'", but why it should have been spoken in a foreign language mystified him not a little.

While he was thinking about this the door opened, as if by a released spring, and he saw before him a long, narrow passage, lit by four electric arcs, and closed at the other end by a door, guarded by a sentry armed with a magazine rifle.

He followed Colston down the passage, and when within a dozen feet of the sentry, he brought his rifle to the "ready," and the following strange dialogue ensued between him and Colston—

"Quien va?"

"Zwei Freunde der Bruderschaft."

"Por la libertad?"

"Fur Freiheit Uber alles!"

"Pass, friends."

The rifle grounded as the words were spoken, and the sentry stepped back to the wall of the passage.

At the same moment another bell rang beyond the door, and then the door itself opened as the other had done. They passed through, and it closed instantly behind them, leaving them in total darkness.

Colston caught Arnold by the arm, and drew him towards him, saying as he did so—

"What do you think of our system of passwords?"

"Pretty hard to get through unless one knew them, I should think. Why the different languages?"

"To make assurance doubly sure every member of the Inner Circle must be conversant with four European languages. On these the changes are rung, and even I did not know what the two languages were to be to-night before I entered the house, and if I had asked for 'Mr. Brown' instead of 'Mr. Smith,' we should never have got beyond the drawing-room.

"When the footman told me in German that the word was 'Freedom,' I knew that I should have to answer the challenge of the sentry in German. I did not know that he would challenge in Spanish, and if I had not understood him, or had replied in any other language but German, he would have shot us both down without saying another word, and no one would ever have known what had become of us. You will be exempt from this condition, because you will always come with me. I am, in fact, responsible for you."

"H'm, there doesn't seem much chance of any one getting through on false pretences," replied Arnold, with an irrepressible shudder: "Has any one ever tried?"

"Yes, once. The two gentlemen whose disappearance made the famous 'Clapham Mystery' of about twelve months ago. They were two of the smartest detectives in the French service and the only two men who ever guessed the true nature of this house. They are buried under the floor on which you are standing at this moment."

The words were spoken with a cruel inflexible coldness, which struck Arnold like a blast of frozen air. He shivered, and was about to reply when Colston caught him by the arm again, and said hurriedly—

"H'st! We are going in. Remember what I said, and don't speak again till some one asks you to do so."

As he spoke a door opened in the wall of the dark chamber in which they had been standing for the last few minutes, and a flood of soft light flowed in upon their dazzled eyes. At the same moment a man's voice said from the room beyond in Russian—

"Who stands there?"

"Maurice Colston and the Master of the Air," replied Colston in the same language.

"You are welcome," was the reply, and then Colston, taking Arnold by the arm, led him into the room.

As soon as Arnold's eyes got accustomed to the light, he saw that he was in a large, lofty room with panelled walls adorned with a number of fine paintings. As he looked at these his gaze was fascinated by them, even more than by the strange company which was assembled round the long table that occupied the middle of the room.

Though they were all manifestly the products of the highest form of art, their subjects were dreary and repulsive beyond description. There was a horrible realism about them which reminded him irresistibly of the awful collection of pictorial horrors in the Musze Wiertz, in Brussels— those works of the brilliant but unhappy genius who was driven into insanity by the sheer exuberance of his own morbid imagination.

Here was a long line of men and women in chains staggering across a wilderness of snow that melted away into the horizon without a break. Beside them rode Cossacks armed with long whips that they used on men and women alike when their fainting limbs gave way beneath them, and they were like to fall by the wayside to seek the welcome rest that only death could give them.

There was a picture of a woman naked to the waist, and tied up to a triangle in a prison yard, being flogged by a soldier with willow wands, while a group of officers stood by, apparently greatly interested in the performance. Another painting showed a poor wretch being knouted to death in the market- place of a Russian town, and yet another showed a young and beautiful woman in a prison cell with her face distorted by the horrible leer of madness, and her little white hands clawing nervously at her long dishevelled hair.

Arnold stood for several minutes fascinated by the hideous realism of the pictures, and burning with rage and shame at the thought that they were all too terribly true to life, when he was startled out of his reverie by the same voice that had called them from the dark room saying to him in English—

"Well, Richard Arnold, what do you think of our little picture gallery? The paintings are good in themselves, but it may make them more interesting to you if you know that they are all faithful reproductions of scenes that have really taken place within the limits of the so-called civilised and Christian world. There are some here in this room now who have suffered the torments depicted on those canvases, and who could tell of worse horrors than even they portray. We should like to know what you think of our paintings?"

Arnold glanced towards the table in search of Colston, but he had vanished. Around the long table sat fourteen masked and shrouded forms that were absolutely indistinguishable one from the other. He could not even tell whether they were men or women, so closely were their forms and faces concealed. Seeing that he was left to his own discretion, he laid the case containing the model, which he had so far kept under his arm, down on the floor, and, facing the strange assembly, said as steadily as he could—

"My own reading tells me that they are only too true to the dreadful reality. I think that the civilised and Christian Society which permits such crimes to be committed against humanity, when it has the power to stop them by force of arms, is neither truly civilised nor truly Christian."

"And would you stop them if you could?"

"Yes, if it cost the lives of millions to do it! They would be better spent than the thirty million lives that were lost last century over a few bits of territory."

"That is true, and augurs well for our future agreement. Be kind enough to come to the table and take a seat."

The masked man who spoke was sitting in the chair at the foot of the table, and as he said this one of those sitting at the side got up and motioned to Arnold to take his place. As soon as he had done so the speaker continued—

"We are glad to see that your sentiments are so far in accord with our own, for that fact will make our negotiations all the easier.

"As you are aware, you are now in the Inner Circle of the Terrorists. Yonder empty chair at the head of the table is that of our Chief, who, though not with us in person, is ever present as a guiding influence in our councils. We act as he directs, and it was from him that we received news of you and your marvellous invention. It is also by his direction that you have been invited here to-night with an object that you are already aware of.

"I see from your face that you are about to ask how this can be, seeing that you have never confided your secret to any one until last night. It will be useless to ask me, for I myself do not know. We who sit here simply execute the Master's will. We ask no questions, and therefore we can answer none concerning him."

"I have none to ask," said Arnold, seeing that the speaker paused as though expecting him to say something. "I came at the invitation of one of your Brotherhood to lay certain terms before you, for you to accept or reject as seems good to you. How you got to know of me and my invention is, after all, a matter of indifference to me. With your perfect system of espionage you might well find out more secret things than that."

"Quite so," was the reply. "And the question that we have to settle with you is how far you will consent to assist the work of the Brotherhood with this invention of yours, and on what conditions you will do so."

"I must first know as exactly as possible what the work of the Brotherhood is."

"Under the circumstances there is no objection to your knowing that. In the first place, that which is known to the outside world as the Terror is an international secret society underlying and directing the operations of the various bodies known as Nihilists, Anarchists, Socialists—in fact, all those organisations which have for their object the reform or destruction, by peaceful or violent means, of Society as it is at present constituted.

"Its influence reaches beyond these into the various trade unions and political clubs, the moving spirits of which are all members of our Outer Circle. On the other side of Society we have agents and adherents in all the Courts of Europe, all the diplomatic bodies, and all the parliamentary assemblies throughout the world.

"We believe that Society as at present constituted is hopeless for any good thing. All kinds of nameless brutalities are practised without reproof in the names of law and order, and commercial economics. On one side human life is a splendid fabric of cloth of gold embroidered with priceless gems, and on the other it is a mass of filthy, festering rags, swarming with vermin.

"We think that such a Society—a Society which permits considerably more than the half of humanity to be sunk in poverty and misery while a very small portion of it fools away its life in perfectly ridiculous luxury —does not deserve to exist, and ought to be destroyed.

"We also know that sooner or later it will destroy itself, as every similar Society has done before it. For nearly forty years there has now been almost perfect peace in Europe. At the same time, over twenty millions of men are standing ready to take the field in a week.

"War—universal war that will shake the world to its foundations —is only a matter of a little more delay and a few diplomatic hitches. Russia and England are within rifleshot of each other in Afghanistan, and France and Germany are flinging defiances at each other across the Rhine.

"Some one must soon fire the shot that will set the world in a blaze, and meanwhile the toilers of the earth are weary of these dreadful military and naval burdens, and would care very little if the inevitable happened to- morrow.

"It is in the power of the Terrorists to delay or precipitate that war to a certain extent. Hitherto all our efforts have been devoted to the preservation of peace, and many of the so-called outrages which have taken place in different parts of Europe, and especially in Russia, during the last few years, have been accomplished simply for the purpose of forcing the attention of the administrations to internal affairs for the time, and so putting off what would have led to a declaration of war.

"This policy has not been dictated by any hope of avoiding war altogether, for that would have been sheer insanity. We have simply delayed war as long as possible, because we have not felt that we have been strong enough to turn the tide of battle at the right moment in favour of the oppressed ones of the earth and against the oppressors.

"But this invention of yours puts a completely different aspect on the European situation. Armed with such a tremendous engine of destruction as a navigable air-ship must necessarily be, when used in conjunction with the explosives already at our disposal, we could make war impossible to our enemies by bringing into the field a force with which no army or fleet could contend without the certainty of destruction. By these means we should ultimately compel peace and enforce a general disarmament on land and sea.

"The vast majority of those who make the wealth of the world are sick of seeing that wealth wasted in the destruction of human life, and the ruin of peaceful industries. As soon, therefore, as we are in a position to dictate terms under such tremendous penalties, all the innumerable organisations with which we are in touch all over the world will rise in arms and enforce them at all costs.

"Of course, it goes without saying that the powers that are now enthroned in the high places of the world will fight bitterly and desperately to retain the rule that they have held for so long, but in the end we shall be victorious, and then on the ruins of this civilisation a new and a better shall arise.

"That is a rough, brief outline of the policy of the Brotherhood, which we are going to ask you to-night to join. Of course, in the eyes of the world we are only a set of fiends, whose sole object is the destruction of Society, and the inauguration of a state of universal anarchy. That, however, has no concern for us. What is called popular opinion is merely manufactured by the Press according to order, and does not count in serious concerns. What I have described to you are the true objects of the Brotherhood; and now it remains for you to say, yes or no, whether you will devote yourself and your invention to carrying them out or not."

For two or three minutes after the masked spokesman of the Inner Circle had ceased speaking, there was absolute silence in the room. The calmly spoken words which deliberately sketched out the ruin of a civilisation and the establishment of a new order of things made a deep impression on Arnold's mind. He saw clearly that he was standing at the parting of the ways, and facing the most tremendous crisis that could occur in the life of a human being.

It was only natural that he should look back, as he did, to the life from which a single step would now part him for ever, without the possibility of going back. He knew that if he once put his hands to the plough, and looked back, death, swift and inevitable, would be the penalty of his wavering. This, however, he had already weighed and decided.

Most of what he had heard had found an echo in his own convictions. Moreover, the life that he had left had no charms for him, while to be one of the chief factors in a world-revolution was a destiny worthy both of himself and his invention. So the fatal resolution was taken, and he spoke the words that bound him for ever to the Brotherhood.

"As I have already told Mr. Colston," he began by saying "I will join and faithfully serve the Brotherhood if the conditions that I feel compelled to make are granted"—

"We know them already," interrupted the spokesman, "and they are freely granted. Indeed, you can hardly fail to see that we are trusting you to a far greater extent than it is possible for us to make you trust us, unless you choose to do so. The air-ship once built and afloat under your command, the game of war would to a great extent be in your own hands. True, you would not survive treachery very long; but, on the other hand, if it became necessary to kill you, the air-ship would be useless, that is, if you took your secret of the motive power with you into the next world."

"As I undoubtedly should," added Arnold quietly.

"We have no doubt that you would," was the equally quiet rejoinder. "And now I will read to you the oath of membership that you will be required to sign. Even when you have heard it, if you feel any hesitation in subscribing to it, there will still be time to withdraw, for we tolerate no unwilling or half- hearted recruits."

Arnold bowed his acquiescence, and the spokesman took a piece of paper from the table and read aloud—

"I, Richard Arnold, sign this paper in the full knowledge that in doing so I devote myself absolutely for the rest of my life to the service of the Brotherhood of Freedom, known to the world as the Terrorists. As long as I live its ends shall be my ends, and no human considerations shall weigh with me where those ends are concerned. I will take life without mercy, and yield my own without hesitation at its bidding. I will break all other laws to obey those which it obeys, and if I disobey these I shall expect death as the just penalty of my perjury."

As he finished reading the oath, he handed the paper to Arnold, saying as he did so—

"There are no theatrical formalities to be gone through. Simply sign the paper and give it back to me, or else tear it up and go in peace."

Arnold read it through slowly, and then glanced round the table. He saw the eyes of the silent figures sitting about him shining at him through the holes in their masks. He laid the paper down on the table in front of him, dipped a pen in an inkstand that stood near, and signed the oath in a firm, unfaltering hand. Then—committed for ever, for good or evil, to the new life that he had adopted—he gave the paper back again.

The President took it and read it, and then passed it to the mask on his right hand. It went from one to the other round the table, each one reading it before passing it on, until it got back to the President. When it reached him he rose from his seat, and, going to the fireplace, dropped it into the flames, and watched it until it was consumed to ashes. Then, crossing the room to where Arnold was sitting, he removed his mask with one hand, and held the other out to him in greeting, saying as he did so—

"Welcome to the Brotherhood! Thrice welcome! for your coming has brought the day of redemption nearer!"

AS Arnold returned the greeting of the President, all the other members of the Circle rose from their seats and took off their masks and the black shapeless cloaks which had so far completely covered them from head to foot.

Then, one after the other, they came forward and were formally introduced to him by the President. Nine of the fourteen were men, and five were women of ages varying from middle age almost to girlhood. The men were apparently all between twenty-five and thirty-five, and included some half-dozen nationalities among them.

All, both men and women, evidently belonged to the educated, or rather to the cultured class. Their speech, which seemed to change with perfect ease from one language to another in the course of their somewhat polyglot converse, was the easy flowing speech of men and women accustomed to the best society, not only in the social but the intellectual sense of the word.

All were keen, alert, and swift of thought, and on the face of each one there was the dignifying expression of a deep and settled purpose which at once differentiated them in Arnold's eyes from the ordinary idle or merely money- making citizens of the world.

As each one came and shook hands with the new member of the Brotherhood, he or she had some pleasant word of welcome and greeting for him; and so well were the words chosen, and so manifestly sincerely were they spoken, that by the time he had shaken hands all round Arnold felt as much at home among them as though he were in the midst of a circle of old friends.

Among the women there were two who had attracted his attention and roused his interest far more than any of the other members of the Circle. One of these was a tall and beautifully-shaped woman, whose face and figure were those of a woman in the early twenties, but whose long, thick hair was as white as though the snows of seventy winters had drifted over it. As he returned her warm, firm hand-clasp, and looked upon her dark, resolute, and yet perfectly womanly features, the young engineer gave a slight start of recognition. She noticed this at once and said, with a smile and a quick flash from her splendid grey eyes—

"Ah! I see you recognise me. No, I am not ashamed of my portrait. I am proud of the wounds that I have received in the war with tyranny, so you need not fear to confess your recognition."

It was true that Arnold had recognised her. She was the original of the central figure of the painting which depicted the woman being flogged by the Russian soldiers.

Arnold flushed hotly at the words with the sudden passionate anger that they roused within him, and replied in a low, steady voice—

"Those who would sanction such a crime as that are not fit to live. I will not leave one stone of that prison standing upon another. It is a blot on the face of the earth, and I will wipe it out utterly!"

"There are thousands of blots as black as that on earth, and I think you will find nobler game than an obscure Russian provincial prison. Russia has cities and palaces and fortresses that will make far grander ruins than that —ruins that will be worthy monuments of fallen despotism," replied the girl, who had been introduced by the President as Radna Michaelis. "But here is some one else waiting to make your acquaintance. This is Natasha. She has no other name among us, but you will soon learn why she needs none."

Natasha was the other woman who had so keenly roused Arnold's interest. Woman, however, she hardly was, for she was seemingly still in her teens, and certainly could not have been more than twenty.

He had mixed but little with women, and during the past few years not at all, and therefore the marvellous beauty of the girl who came forward as Radna spoke seemed almost unearthly to him, and confused his senses for the moment as some potent drug might have done. He took her outstretched hand in awkward silence, and for an instant so far forgot himself as to gaze blankly at her in speechless admiration.

She could not help noticing it, for she was a woman, and for the same reason she saw that it was so absolutely honest and involuntary that it was impossible for any woman to take offence at it. A quick bright flush swept up her lovely face as his hand closed upon hers, her darkly-fringed lids fell for an instant over the most wonderful pair of sapphire-blue eyes that Arnold had ever even dreamed of, and when she raised them again the flush had gone, and she said in a sweet, frank voice—

"I am the daughter of Natas, and he has desired me to bid you welcome in his name, and I hope you will let me do so in my own as well. We are all dying to see this wonderful invention of yours. I suppose you are going to satisfy our feminine curiosity, are you not?"

The daughter of Natas! This lovely girl, in the first sweet flush of her pure and innocent womanhood, the daughter of the unknown and mysterious being whose ill-omened name caused a shudder if it was only whispered in the homes of the rich and powerful, the name with which the death-sentences of the Terrorists were invariably signed, and which had come to be an infallible guarantee that they would be carried out to the letter.

No death-warrants of the most powerful sovereigns of Europe were more certain harbingers of inevitable doom than were those which bore this dreaded name. Whether he were high or low, the man who received one of them made ready for his end. He knew not where or when the fatal blow would be struck. He only knew that the invisible hand of the Terror would strike him as surely in the uttermost ends of the earth as it would in the palace or the fortress. Never once had it missed its aim, and never once had the slightest clue been obtained to the identity of the hand that held the knife or pistol.

Some such thoughts as these flashed one after another through Arnold's brain as he stood talking with Natasha. He saw at once why she had only that one name. It was enough, and it was not long before he learnt that it was the symbol of an authority in the Circle that admitted of no question.

She was the envoy of him whose word was law, absolute and irrevocable, to every member of the Brotherhood; to disobey whom was death; and to obey whom had, so far at least, meant swift and invariable success, even where it seemed least to be hoped for.

Of course, Natasha's almost girlish question about the airship was really a command, which would have been none the less binding had she only had her own beauty to enforce it. As she spoke the President and Colston—who had only lost himself for the time behind a mask and cloak—came up to Arnold and asked him if he was prepared to give an exhibition of the powers of his model, and to explain its working and construction to the Circle at once.

He replied that everything was perfectly ready for the trial, and that he would set the model working for them in a few minutes. The President then told him that the exhibition should take place in another room, where there would be much more space than where they were, and bade him bring the box and follow him.

A door was now opened in the wall of the room remote from that by which he and Colston had entered, and through this the whole party went down a short passage, and through another door at the end which opened into a very large apartment, which, from the fact of its being windowless, Arnold rightly judged to be underground, like the Council-chamber that they had just left.

A single glance was enough to show him the chief purpose to which the chamber was devoted. The wall at one end was covered with arm-racks containing all the newest and most perfect makes of rifles and pistols; while at the other end, about twenty paces distant, were three electric signalling targets, graded, as was afterwards explained to him, to one, three, and five hundred yards range.