an ebook published by Project Gutenberg Australia

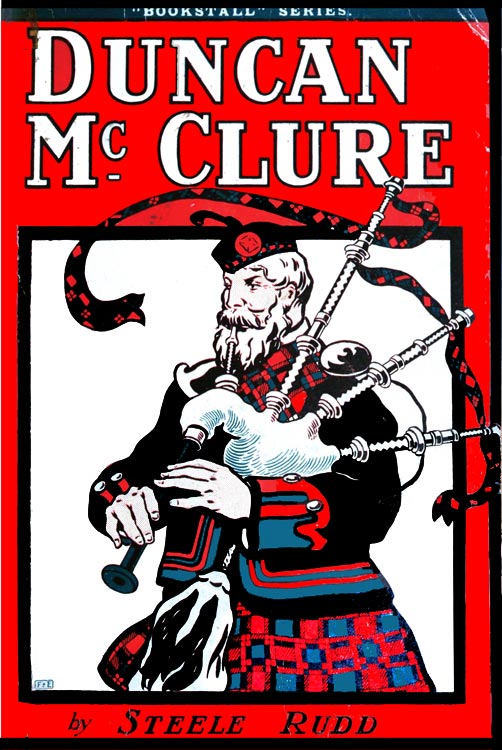

Title: Duncan McClure

Author: Steele Rudd

eBook No.: 2400141h.html

Language: English

Date first posted: May 2024

Most recent update: May 2024

This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore

Chapter 1. - The Pioneers

Chapter 2. - The Country Store

Chapter 3. - A Word in Season

Chapter 4. - Trouble At McLeod’s

Chapter 5. - A Bush Tragedy Averted

Chapter 6. - A Fresh Misfortune

Chapter 7. - Bailey and the Morrows

Chapter 8. - The Poor Parson Takes An Outing

Chapter 9. - The Land Sale

Chapter 10. - McClure Drops in for a Crack

Chapter 11. - Retribution

Chapter 12. - The Lord Loveth A Cheerful Giver

Chapter 13. - The Wedding

The sun went down on a blazing, blistering summer day. A stiff, cool breeze sprang up and fanned the sun-baked earth, and sobbed and soughed in the cornstalks and in the dense and darkened forest trees. Under the shadows of the barn a pair of plough horses, eye deep in nose-bags, crunched and crunched at their feed. From the sheep-fold came the last bleats of the ewes as the flock settled restfully for the night. From a vessel set at the back-door a pair of collies noisily lapped up the table leavings.

A light streamed through the open cracks of the crude, temporary dwelling.

Inside, the pioneers, father and two sons, sat back from the tea table, silent, reflectful. Scotch people they were, from Loch Lomond—Scotch people with a broad accent and big hearts—new arrivals with a faith as strong as their Presbyterianism in the future of the new land, the great bushland, the wide, torrid Queensland. They believed in land—these Scotch pioneers, and in sheep, and in wheat, and in horses, and cows—in all things, in fact, pertaining to the soil—and the soul. And they believed in these things just as they believed in the Bible, and John Knox. They believed in these things the more when others around them, overtaken by floods and droughts and fires, lost heart and hope, and cried curses down upon the new land, and, like the Israelites, murmured against their lot, and prayed to the Lord for deliverance.

The father and sons became known in the district— in the new bush district of Woothen-binbee—as old Sandy McClure, and Colin and Duncan McClure. The sons were of middle-age: burly, bulky, big-framed, red-whiskered men, with square-cut heads, big feet and humorous eyes. The parent, or the “heidmon” as he was styled domestically, was an undersized, wiry, old veteran with a large, inquisitive head, characteristic features, and an obsolete parsonic shave.

A fiery, boisterous, stern, exacting, strong-willed, crabby, old warrior he was; yet just, high-principled and painfully honourable.

The “heidmon” glanced round at a crude side-table supporting a bulky, well-worn family Bible, and said:

“Didna ony o’ ye fetch the newspaper th’ day?”

“Oh, be th’ hokey,” Duncan answered, rising hurriedly to reach down the weekly mail from a shelf above his head— “there’s a grreat fat letter for ye. There must be a deil o’ a lot o’ news in ’t. It weighs as heavy as Cain’s conscience maun a’ done when he knocked his wee brither on th’ heid.”

“Be th’ kin o’ write I think it’s frae Jean,” Colin put in prophetically, as his brother handed over the mail.

“I think it maun be hers, for ye canna mistake Jean’s write,” Duncan added, with just a suspicion of mischief in his eye. “Jean hasna ony idea o’ art. She scrawls a’ roon th’ envelope, y’ ken, like th’ heidmon hissel’.”

“E-ech!” in a prolonged groan from the stern-visaged old man, as he broke open the seal and extracted several sheets of closely-written and cross-written notepaper, and leaned back to read it.

Duncan winked good naturedly at his brother, and paying no further heed to the parent, who became absorbed in his daughter’s letter, opened a conversation across the table with Colin.

“Wha th’ deuce was that cove,” he asked, “wi’ a rag fleein’ frae his hat like a tail o’ a sark wha was crackin’ tae ye at th’ corn paddick aboot three o’clock?”

“I didna ken him frae Adam,” Colin answered slowly. “He was tryin’ terrible hard to explain something or ither tae me aboot his farm or his auld woman or some one, but I couldna mak heid nor tail o’ him. He stuttered something awfu’.”

“That’s th’ beggarin’ chap,” Duncan exclaimed, with beaming face. “He came ower tae th’ plough tae me and stood glowering for th’ deil’s own time at a furrow I just opened. It was a middlin’ straight furrow, ye ken, for a wunner, and he couldua see what kin’ o’ a mark it was I had tae guide mysel by. The flagpole I had put up was richt outside th’ paddoek a’th’gither, an’ he had his back tae it, an’ couldna see ahint him.”

“ ‘W-w-what aire y’ g-g-g-goin be?’ he stuttered oot, an’ I sez to him, pretendin’ I didna unnerstan’—‘Oh, I’m gaun be th’ bloomin’ sun, but there’s a lot of beggarin’ cloods aboot th’ dey?’

“ ‘Goin’ be th’ s-s-s-sun!’ he spluttered wi’ a look o’ rreal consterneetion in his ee!

“ ‘Yers,’ I answered, quite loud at him—‘It’s th’ best way if ye want tae pleugh straight. It’s far better than—’ ”

“Haud yer tangue,” the heidmon broke out in a roar. The sons looked at him. But as his eyes remained fixed on the letter and his lips working rapidly, Duncan deemed it safe to proceed.

“ ‘It’s better than flags?’ I said tae him, ‘an’ it’s no sae much trouble, ye ken. Ye havena got tae put it up.’”

They both laughed at the expense of the absent stranger.

“ ‘W-w-weel I’m blawed!’ he said,” Duncan went on— ‘th-th-that’s a wr-r-r-rinkle if ye l-l-l-like. ’ ”

“De ye tell me he said that, truly?” Colin asked in confirmation of the stranger’s simplicity.

“Be th’ hokey he ded that, Colin,” Duncan affirmed with great solemnity. “An’ efter a while he began tae think it oot for hissel’ an’ keeked at the sun a deuce o’ a lot o’ times.”

“ ‘But I d-d-don’t see how ye can g-g-g-go be it.’ he said, ‘when it sh-sh-shifts,’ thinkin’ tae bowl me oot, maybe.”

“ ‘That’s just whaur ye’re wrang,’ I said, an’ waved me haan’ aboot i’ th’ air like a parrson i’ th’ pu’pit. ‘Th’ sun doesna shift at a’,’ I said, gi’en him a bit o’ science. ‘Dinna ye ken it’s the erth ye’re stannin’ on, mon, that, revolves aroon’ th’ sun?’ an’ bless me, he said ‘he didna,’ an’ I lauched at him. ‘Why blaw it, ye dinna ken muckle i’ this country,’ I telt him, ‘if ye dinna ken tae pleugh by th’ sun. It’s a’ th’ faishion i’ Scotland.’ An’ he just it managed tae squirt oot that he ‘wer d-d-d-daimed when—”

There was another interruption.

“Are ye daft?” the heidmon roared; still without looking up, and closely perusing the letter. Duncan paused a moment, and, looking slyly toward his parent, continued in a suppressed voice:

“An’ just, when he telt me he was daimed, Colin, the heidmon’s voice”—(glancing again at the solemn sire) — “rrattled on the air ahint us like a clap o’ thunner, an’ made us baith jump an’ look roon.” Colin smothered his feelings with a bag of oatmeal that lay on the table.

“An dang it if he wasna bangin’ on wi’ one haun’ tae th’ flagpole that I had stuck i’ th’ grund, an’ wi’ th’ ither was wavin’ his crummuck.

“ ‘Tak’ ye a braw new hay fork to guide ye’re crooked ee by?’ he yelled—‘ye careless yokel, I’ll bash ye’re heid wi’ it?’ ” (Another sly glance at the heidmon.) “ ‘By crikey,’ I said tae th’ cove, ‘th’ auld heidmon’s in a deil o’ a rage wi’ someone, -ye better slither!’ An’ be cripes, he cleared for his vara life wi’oot knowin’ how I had lee’d tae him.”

The heidmon lifted his eyes at last, and glared at the sons.

“Wunna ye e’er gi’ ower yer gabblin’?” he shouted— “wunna ye?”

Then after a pause:

“Hae ye nae thochts o’ sympathy at a’ for ye’re sister in sair distress wi’ the worl’, an’ her ten puir faitherless bairns! . . Ah, me!” and a troubled sigh escaped him.

The big burly sons became grave and concerned, and feelingly enquired for the welfare of their widowed sister.

“I’ll gi’ it tae ye in fu’.” And the heidmon in loud solemn tones read the letter.

“Puir Jean!” Colin said, “It’s peetifu’! She canna be left tae battle alane wi’ sae many wee anes withoot assistance.”

“By jove, no,” Duncan said, as though that side of the situation had just occurred to him. Then by way of suggestion: “Couldua we bring them a’ up here?”

“ ’Tis what’s vexin’ my ain min’,” the parent answered, and rising from the table he tramped the room in thought and reflection, at intervals sighing: “Ah me; ah, me.”

Colin spoke.

“I think she’d be a lot better—” But he didn’t finish.

“Haud ye’re tangue!” shouted the heidmon at the top of his voice.

Colin held his tongue.

Then:

“I hae solved it,” and the heidmon paused suddenly, and faced round.

“I’ th’ morn I’ll gang mysel tae that drucken scalliway, Skein, out-by, an’ gie what he askit for his shanty o’ a dwellin’. Th’ railway line is a’maist builded noo, an’ he’ll hae nae mair custom for his grog. It’s made o’ wither board an’ guid iron’s on the roof, an’ wad mak them a hame an dae for to start a bit sma’ store.”

“By jove! yers,” Duncan answered enthusiastically— “that’s a gran’ idea.”

But Colin didn’t go into raptures over it. Colin had “doots aboot the success o’ a store i’ th’ wild woods whaur there was only aboot sax or seeven families a’th’githur in th’ deestric’.”

The Heidmon went off the handle. He struck the table hard with his fist and yelled:

“Wunna ye e’er get gumption intae ye’re wooden heid? Sax families in a’ th’ deestric’! Ay, an’ be th’ tame th’ bairns can follow th’ plengh wunna there be sax hunner think ye? Whare in a’ th’ Lord’s earth, unner a’ his blue sky tell me is there sic a gran’ land? Sax families in a’ th’ deestric’! Ay, an it’s saxpenee an acre th’ noo, but wunna ye live an’ wunna my ain sel live tae see th’ day when ’twill be saxteen poon’ an acre? Wha’ll deny it? Wha?” And his chest heaved, and his eye flashed fire.

Then ignoring Colin and turning sharply to Duncan : “Get ye pen an’ ink the noo an’ write ye th’ puir body an’ tell her a’ we hae planned. If she disna prosper say ye, I’ll gie my ain word she wunna starve.” And while Duncan procured the writing material and commenced the letter the heidmon paced the room again.

Duncan paused in his labours to moisten the pen with his large, red tongue, and leaning heavily on his elbows said: “By jove, this is a grreat plan It’s far better than they should a’ stick doon there i’ th’ city. If she doesna mak’ a lot out o’ th’ store it winna maitter a fig. Look at a’ th’ spare grub we hae roon’ us here. They need never want for a dish o’ spuds or a bloomin’ pumpkin, or a leg o’ mutton—”

“Ech, michty!” the heidmou bellowed, “canna ye stop blawin’ tae yoursel’!”—and as he paused in his stride th’ end of one of the floor boards elevated itself, and pointed at the rafters where a number of swallows were roosting— “an’ get on wi’ whaat ye’re daein.”

Duncan got on with the letter, and as the heidmon continued his pacing, the up-ended board fell back into position with a loud rattle behind him. Colin, who meanwhile had taken down a violin and was screwing at the keys of it, looked up in surprise.

“Whaat was that?” the heidmon asked, looking all round the room.

Duncan glanced up and chuckled. Duncan was familiar with the eccentricities of the floor. He had seen the board performing before.

“Whaat was it?” the heidmon persisted noisily.

“Nothing,” Duncan said, with a broad grin, “ainly th’ bloomin fluir boards jumpin’ up tae hit someane i’ th’ ee. ”

“Ech! ye dinna talk sense,” the heidmon growled, and going to the door, opened it and yelled into the night— “Detchie! Detchie!” and the two collies responded in frolicking bounds. And while he talked to them in language which only they could understand, Colin, thinking of the floor, said:

“ ’Tis a guid job. Duncan, we haena got wives, else we’d hae to fix th’ boards, I’m thinkin’.”

“By jove! I dinna ken that,” Duncan replied, labouring hard with the pen. “If we’d ’a ta’en wives”—(a pause) —“we could hae set them”—(another pause)—“to nailing th’ boards doon for us.” (A further pause.) “How d’ye think that big ane that rins aboot the scrub out-by wi’ bare feet wad suit ye, Colin ?”

“Weel, th’ fluir wadna suit her,” the other answered. “I wad be a’ ma time pu’in’ splinters out o’ her feet.”

“Hae ye feenished?” the heidmon shouted, closing the door on the dogs and turning to the light again.

“I’m just on th’ last word,” came calmly from Duncan. “I’ve been addin’ a piece frae mysel’.”

“Read it,” the parent commanded sternly.

Duncan read the epistle over with difficulty.

“Ech!” the heidmon grunted disparagingly; “it isna put th’gither at a’. A wean could do nae worse.”

Duncan’s eyes twinkled.

“I’m a bit nateral in expreesion, maybe,” he drawled in extenuation, “tae mak’ a guid deeplomat. I just ca’ a spade a spade.”

Then, as he folded the letter and placed it in the envelope:

“Dae ye ken what a’ these colonial chaps ca’ a spade?”

“Ech! I dinna,” grunted the heidmon. contemptuously.

“A (blanky) shovel!” Duncan said, cold-bloodedly.

The heidmon drew himself up to his full height, while his drooping underlip curled like a ringlet of hair.

“Hoot awa’!” he roared. “Daur ye mak’ sic an ungodly speech an’, th’ Bible starin’ ye i’ th’ vara ee? I’m sair shamed o’ it. Claes ye th’ letter!”

Duncan took reproof in grave silence, but Colin, to conceal his feelings, hugged the violin closely, while in a weird, mournful manner he rasped out the air to “The Bonnie Hills of Scotland.”

The heidmon, casting a final look of reproach at the imperturbable Duncan, sank into an old-fashioned arm-chair lined with bagging, and leaning forward fell into reflection.

“Ay! Ay!” he sighed, when the strains of the violin ceased. “Th’ Bonnie Hills o’ Scotland! . . . . Ah, me!”

His eyes remained fixed on the floor. Suddenly his voice was lifted, and in mellow, broken tones he sang:

“The bonnie hills o’ Sco-ot-lan’, I never mair may see,

An’ nae spot se dear in a’ the worl’ as those bonnie hills tae me.”

He broke off, and supporting his elbows on his knees, and resting his chin in his palms, remained swaying gently from side to side till the old-fashioned family clock, that had graced the walls of his ancestors in the Highlands, struck ten. “Ah, me!” he murmured, and pulling himself together rose and approached the side-table.

A few minutes later his voice was heard reading a chapter from the huge family Bible.

For three years now Mrs. Stewart had been settled in her country store at Woothen-binbee to which she had come in answer to her brother Duncan’s letter. It was not a large store. It was a store and dwelling in one. The widow’s humble dining-room opened into it; and when customers happened along she would put aside her sewing or leave her baking-board to serve in the shop. Customers didn’t happen along very frequently, though. When they did chance to turn up, however, it was for a bag of flour, or a bag of sugar, or a chest of tea. Money wasn’t thrown away by the inhabitants of Woothen-binbee in those days. It didn’t require the income to keep them that it does now. If they procured sufficient to feed and clothe themselves and their numerous offspring they were content. It was no use being discontented. They couldn’t afford to invest in much else. And if credit were denied them for that little until “after the harvesting,” which was nearly always put off for a number of seasons, they would have had to refrain from investing at all, and go out into the wildest parts of their paddocks and become a lot of John the Baptists, and pioneer the land on grasshoppers and wild honey. But their hearts were full of hope, and they had rare confidence in the new land, had those old pioneers. And in return the widow gained confidence in them, and trusted them with bag of flour after bag of flour, and looked to Providence to see her through. And somehow Providence always seemed to come along just when the sun was about to set on her troubles, and see her through.

The old “heidmon” and Colin and Duncan McClure used to come along too, sometimes, and visit the little store. The heidmon mostly came to discuss the business side of it with his daughter; Colin merely to see how his sister and all the youngsters were getting along; Duncan to poke about behind the counter and like a big school-boy examine curiously the articles that were displayed on the shelves.

“By jove!” said Duncan one day, when his eyes rested on a concertina case. “What th’ deuce hae ye in that thing, Jean?”

Mrs. Stewart enlightened him.

“Well, I’m blawed. I never had a guid look at ane,” and Duncan opened the case and extracted the instrument.

“Crikey!”—pushing his fat, dumpy fists into the straps —“there’s a cove up at th’ scrub wha has one o’ those an’ from our verandah we can hear him playin’ it like th’ vera deil every nieht. . . I wonder if they’re anyways hard tae learn.”

Mrs. Stewart thought Duncan “wouldna have vera much trouble to learn, seein’ as how he could blaw th’ pipes. ”

“But this is a lot deeferent,” Duncan said, expanding the concertina almost to bursting point, and eyeing the ribs of it closely. “Look at a’ th’ bloomin’ keys it has.”

Here a traveller, with a swag ou his back, followed by Mrs. O’Moore, from the plains, came in to purchase things, and Mrs. Stewart left Duncan and passed behind the counter. She attended to Mrs. O’Moore first.

“Can y’ play, mate?” the traveller asked of Duncan.

“Cripes, I can’t, can you?” Duncan answered.

“Could a bit one time.”

“Well, gi’ us a bloomin’ tune, now,” and Duncan handed over the concertina to the traveller.

“Looks a pretty good one,” the traveller said, with admiration in his eye. Then seating himself on the counter he commenced to play an Irish jig.

Duncan, with his head on one side, and his hands stuffed in the pockets of his broad trousers, stood watching him intently.

It had been a long time since Mrs. O’Moore had heard such music, and it was too much for her. It stirred her into notion. She turned from the counter and taking a grip of her skirts started to rattle her feet on the shop floor and to twirl about as if she had been caught in a whirlwind

Duncan got a great surprise. He took his hands from his pockets and said: “Cripes! look at this.”

Mrs Stewart leaned over the counter and enjoyed Mrs. O’Moore.

The musician quickened the time. Mrs. O’Moore gave a loud whoop and quickened her time.

“Go it, ol’ girrl,” Duncan said.

Mrs. O’Moore “went it.”

“Crikey!” Duucan said, “she’s as nimble as a two-year old.” But soon Mrs. O’Moore reached her limit, and, with a gasp and a shriek, stopped and returned to the counter again.

“By hokey, but ye’re a guid dancer,” Duncan said to her. Then turning to the musician: “An’ this chap can play that thing like the deil.”

Mrs. O’Moore laughed. The traveller started to play more.

“Would ye believe I could dance?” Duncan said, looking at Mrs. O’Moore.

“I-I-I-wouldn’t, then,” Mrs O’Moore, who had an impediment in her speech, answered bluntly. “You-you- you-you’re too fat, and-and-and-weighty.”

“By jove! I’m no that fat,” Duncan answered, without moving a muscle of his face. “I’m a pretty smart fellow, and I’ll dance a Scotch dance for ye, just to show ye.”

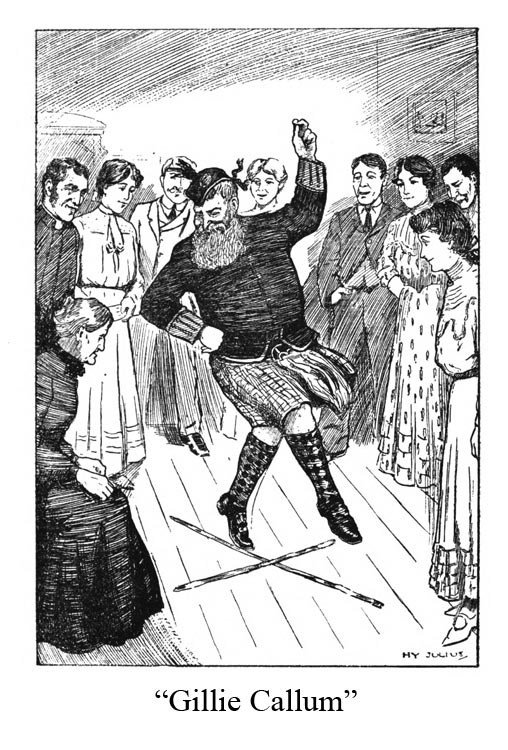

To the musician: “Can ye play ‘Gillie Callum’?”

“Play what?” the musician said with a grin.

Duncan whistled the air, and said—“That?”

The musician shook his head again, and grinned some more.

“Well, play any bloomin’ thing ye like,” and Duncan hitched up his pants and walked around the floor.

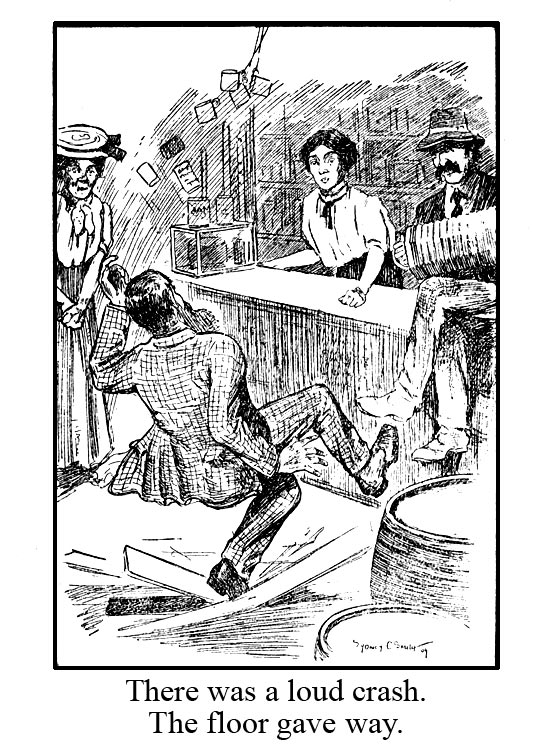

The musician played “anything,” and Duncan with one hand above his head, started dancing the Highland Fling. He danced like a man who regarded dancing as a serious matter. The flooring sank and creaked under his sixteen stone weight; the shop seemed to rock and roll about like a ship.

“You’ll hae th’ place doon,” Mrs. Stewart called out. But Duncan didn’t hear her.

Several tins of jam and some sardines left the shelving and thumped the counter.

“Duncan!” Mrs. Stewart called out in alarm.

Still Duncan didn’t hear her.

There was a loud crash. The floor gave way and let a lot of Duncan through.

“My! my! what hae ye done?” Mrs. Stewart cried.

Mrs. O’Moore threw herself about and laughed noisily. The musician stopped, and laughed too.

“Wha hae I done?” Duncan echoed, lifting himself up slowly. “Hurt me bloomin’ shin; that’s a’.”

“Ech! ye’re awfu’ foolish.” And Mrs. Stewart proceeded to serve Mrs. O’Moore.

Duncan puffed hard, and rubbed his shin.

“Ye ought tae buy that thing,” Duncan said, addressing the traveller, after he had got his wind.

“Oh, I duimo,” the traveller drawled. “How much is it?”

“Oh!” Duncan answered lightly, “about a couple o’ quid,” and added: “It has a gran’ tone.”

“I’d want th’ whole bloomin’ shop for that. Give us a couple of figs o’ tobacco, missus,” and the traveller slipped from his place on the counter.

Mrs. Stewart finished serving, and the customers left the shop.

“Did ye hear me tryin’ to sell th’ concertina to that cove for y’, Jean?” Duncan said, gazing out the door.

“He didna want it, I suppose,” Mrs. Stewart answered thoughtfully.

“He wanted it a’ richt. Jean. I could tell that by th’ way he was huggin’ it so close, ye ken. But it was the price that stuck in his gizzard”

“But how did ye ken th’ price, Duncan?” Mrs. Stewart asked.

“I didna ken th’ bloomin’ price at a’, Jean; I just telt him he could hae it for a couple o’ quid.”

“It doesna surprise me that he didna tak’ it, then, for it’s only eight and six.”

Just then Mrs. O’Moore re-entered the shop in a hurry.

“I-I-I-damn near forgot an axe-handle,” she said. And Duncan, smiling broadly, turned away and entered the dining-room, where Lily, the eldest girl in the Stewart family, was engaged setting the table for dinner.

“That auld Irish woman out there,” he said, “is a rum stick. Do ye ken what she said th’ noo, Lily?”

“What, uncle?” and Lily smiled in anticipation. “She said”—and Duncan closed his eyes and contorted his features, and spoke like Mrs. O’Moore—“I-I-I domu near forgot an axe-handle!”

Lily shrieked, and Duncan, opening his eyes, stared solemnly through a window that over-looked the yard. Several of the boys trailing past in silent procession attracted him.

“What, th’ deuce dae thae chaps reckon their doing?” he asked.

“They’re burying a hen, I think,” Lily answered. “One died last night.”

“Oh, ghost! so they are. That’s just what it is, and they’re givin’ it a bloomin’ funeral,” and Duncan drew nearer the window.

“One o’ them has a spade,” Duncan went on, making discoveries; “he’ll be the undertaker, I suppose. And little Andrew has saething in his hauu that looks like a prayer book. He’ll be the parrson.”

Duncan chuckled and turned from the window.

“Boys do funny bloomin’ things, don’t they,” he added after a silence. “What thae chaps are doin’ noo reminds me of a good joke I played on Colin when we were both youngsters. Colin, ye ken, had an auld speckled hen that he thocht th’ deil o’, an’ one day I let fly a stane at a neighbour’s dog that was comin’ after our eggs and killed this hen o’ Colin’s as dead as Julius Cæsar.”

Lily was seized with a fit of merriment.

Duncan proceeded: “By jove! I got a deil of a frieht when I saw auld Speck give her last kick, and stretch herself out. An’ I didn’t know what to do, so I just sneaked away like a murderer and left her there. And next day, when Colin found her, there was grreat lamentation. He cried like billy-o about her; and I cried too. I felt, ye ken, if I didn’t cry profusely he’d suspect me. Sae we both sat there beside her and wept for the deil’s ain time. And when we had made oursels seeck a’most wi’ grief, we decided tae pay a last treebute o’ respect tae her and gie her a real decent funeral.”

Lily sat to enjoy her uncle.

“We put her remains in a perambulator, and Colin, draped in a black skirt o’ your grandmither’s, pulled it along. But, Lord, Lily, I couldna tell ye what a bloomin’ hypocrit I felt mysel’ when I was followin’ along as chief mourner.”

Lily, laughing, rose and ran out to the kitchen.

The customers having gone, Mrs. Stewart returned to the dining-room.

“Hello!” Duncan broke out, “did auld mother O’Moore get her axe-handle?”

“The puir auld body,” Mrs. Stewart said, and sat down.

Lily came in with a hot joint on a dish. “And didn’t Uncle Colin ever find out who killed his hen?” she asked.

“Oh, yes,” Duncan drawled. “I always meant, ye ken, tae mak’ a clean breast o’ it, an’ clear ma conscience.”

“And you told him?”

“Yes; one day, about sixteen year after, when he was in a good humour, I said tae him, lookin’ straight at him: De ye ken wha killed Speck, Colin?”

“ ‘No,’ he said, opening his eyes as wide as two water-holes.

“ ‘I did!’ I said.” And Duncan chuckled and took up his old felt hat.

“But ye’ll wait for dinner, Duncan?” Mrs. Stewart said. “Canna ye not see it’s a’ ready on th’ table?”

“By jove! no, Jean. I’m in a tearin’ hurry,” Duncan answered, striding to the door. “If I wasna back before dinner the auld heidmon would swear his heid off.”

And Duncan left.

Duncan McClure fell in love, and married and settled down on a farm in the district of Narralane.

The settlers of Narralane were ambitious people and desired to push their district along. At Duncan’s instigation they formed themselves into a Progressive Association and began operations by establishing a debating society.

A man from the city who wrote books and contributed to newspapers was invited to come along and deliver the inaugural address. He came along one evening to Mr. McClure’s barn and was honoured with a large gathering.

Duncan McClure was voted to the chair.

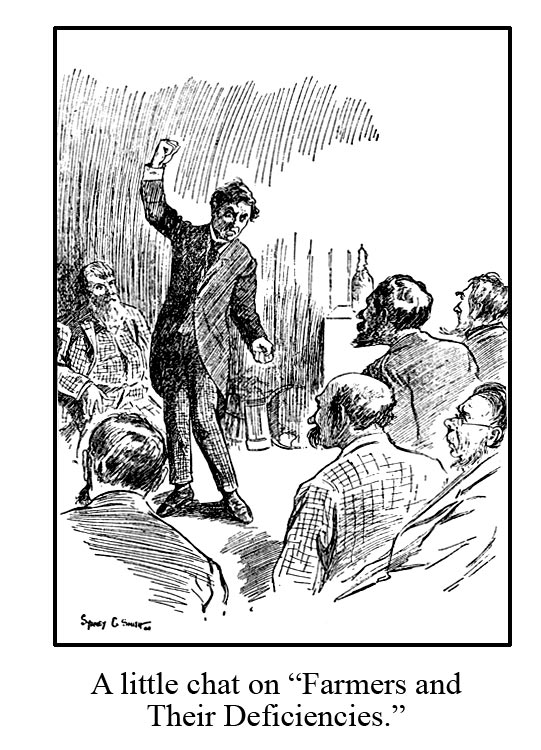

The man from the city rose and said: “Gentlemen, this is not to be a discourse on drink, or heat-waves, or water bags, or a political address. It’s a subject you will all understand. It’s a little chat on ‘Farmers and their Deficiencies.’

“Touching first, then, on the keen delights, the aid and direct benefits to be derived by both young and old alike, from such a society as you propose to establish, I venture to voice the opinion that there is no form of leisure study followed anywhere in the world at the present day that so sharpens and cultivates the intellect—that so readily draws a student to the shelves of a library—that enables him to shape his ideas and give them fit expression—that qualifies him to hold his own in the struggle to maintain his individual rights and public interests so confidently and competently as a training in a well-conducted debating class. And whether he be farmer, propagandist, preacher, patriot, politician or pig-buyer, the same thing applies, and the same advantages will accrue to him. And I know of no man in the community to whom such a training would be of greater assistance than the farmer. And I know of no class who, by their reticence and silence, and by leaning heavily upon the other fellow for intellectual support, so obviously display their own deplorable neglect and deficiency in this same respect as my estimable friends and brethren, the farmers.

“And why is it so with the farmer? It is not because he hasn’t the necessary brains! Not because he has not been given the ground-work of a fair education—but simply because after leaving school—the time when he should only be about to begin to learn something, his young brain is permitted to rest—to get dusty, and rusty, and clogged with cob-webs. To make and amass money he is unfortunately taught, by precept and example, is the sole and only noble object in life; that money is all that is worth working and living for. Literature, music, art, or science of any kind, doesn’t even appear on the dim horizon of his golden ambition. As he matures, his cows, and his horse and sulky, and his numerous barb-wire gates that frequently maim himself and his best horse, and keeps society and the bailiff from getting near the premises, are his oil-paintings, his only art gallery. The local newspaper which prints the highest price for produce, and is loudest and longest in reviling the political party which he doesn’t believe in, is his only literature. And he doesn’t want or seek any other sort of literature. It’s quite good enough for him! The weeping and wailing of the tall cornstalks when a breeze is fanning them on a hot day and the pens of fat porkers squealing their lungs out when the buyer takes a fancy to them, form his one idea of sublime music and melody; the only music worth cultivating, he reckons, and the only melody worth listening to. And amongst these earthly blessings he plods along, putting in his eternal daily rounds, rising with a lantern to milk in the morning and racing home in the sulky from somewhere or other in the evening to milk some more before it gets too dark to see the cows’ teats. His conversation is painfully limited, and chained to circumstance and time. It is mostly of the earth, earthy; and, like his cheese and butter, is raised on the farm —made on the premises. It generally runs on the lucerne, or on the dry grass. Frequently it is confined to the yard or the windmill, or the factory-meeting, or the bull with the long pedigree that he gave a fiver for at a sale of a pensioned-off herd of dairy cattle. The pedigree is regarded as a valuable asset, and becomes a family heirloom. The bull itself doesn’t matter. He is allowed to roam and invariably goes off in the night with the principal barb-wire gate on his horns to make love somewhere.

“Seldom, if ever, will the farmer trust himself to take an active part in a movement where a discussion is necessary and his interests involved. He feels and confesses he should make himself heard, but never having heard his own voice lifted by itself, he doesn’t like the sound of it. His voice is the only ghost that haunts him and it haunts him frequently and effectively—and he dreads letting it out of its dark recesses for an airing. Occasionally, at long and premeditated intervals though, he breaks out in a violent place, and threatens to proceed to the railway station to meet the Commissioner face to face and place a grievance before that great official with the force of several large sledge-hammers. He goes perilously near carrying out the threat, and meets the Commissioner right where he said he would. The Commissioner meets him, too, just as he has met hundreds of him before, and invites him into his ‘special’ carriage. The natural reserve and terrible mental torture of the uncertainty of the moment dispel all the sledge-hammer resolutions, and leave him limp and badly beaten. The Commissioner has done all the talking for him, and told him a lot of things that he didn’t want to know, and at the end warns him to get out before the train starts and over-carries him. And he gets out—stumbles out—falls out like an elephant. And, gentlemen, I might continue dilating on this weak and unhappy feature of the farmer until the next train comes along or your cows come home to be milked and walloped in the bails. But I think I have said enough on that point for a while at all events.

“I have already remarked that the sole ambition of the farmer, as he employs himself to-day, is to make money, and to make it at the sacrifice of all other accomplishments, and the higher and nobler pursuits in life; and lest you should be inclined to forget it, gentlemen, I intend to say it again, and, if possible, to say it much harder, before sitting down. My experience teaches me that outside the four picturesque corners of the cow-yard the farmer never thinks or displays a thought worth tuppence. What force it chiefly is that propels the wheels of the universe he never has time to think out or to worry himself about. He doesn’t want to think about it, and he hasn’t learnt how to think about it, anyway. He is a worshipper of brawn and horse-power and pump handles, and from the scant time he devotes to books which represent the lives and life-work, and are the fruits of the best brains the world has known, it would seem it never occurs to him that there is such a thing as thought-power. It was thought-power which made Christendom, and discovered America, to quote a well-known author. Horsepower may send a steamer over the Atlantic in seven or eight days, but thought-power will send a message across in as many seconds. And, besides, it was thought-power discovered horse-power, and used it.

“I have already admitted that the farmer has as much brains as the next fellow, which perhaps isn’t admitting much—and that it is not because of the lack of brains that he is so intellectually deficient. Being a bit of a phrenologist I can see some of you have and I know from experiences of my own that young fellows reared in the country come to regard their chances of improving themselves as quite hopeless, because they have been denied a high-class education— a university training—and by their retiring, bashful sort of disposition, they stand aside when the coxcomb or man of airs from the city comes along and give him, because of his superior looks, all the talk and all the road-way to himself. And the chances are, maybe, that the man from the city hasn’t half the countrymen’s brains, but having the confidence to assert what little he has or hasn’t, he annexes and carries off the prize. Metaphorically speaking, your young man of the country is leg-roped—intellectually chained up—and is dragging and lagging along like a dingo, a thousand years behind the times. To raise him from his mental lethargy requires more social intercourse—a wider knowledge of the world he lives in, and a closer acquaintance with the works of the master minds that have advanced civilisation, and shaped the destinies of nations. In fact, he has to be hatched and brought right out of his shell. In the vegetating state in which he exists to-day, he is lolloping along in absolute ignorance of the golden opportunities and possibilities that are his very own, if he only knew how to make use of them—which he doesn’t. It is to the glorious open air life of the country, and not to the dim, dirty alleys and attics and back-yards of the congested cities, that Australia-must look for the production of public and literary men fit to rank with the great intellects of other lands. She is centuries behind them to-day, and when the average man of the country, by his own research and study, comes to realise that there is no Shakespeare, no Milton, no Burns, no Johnson, no Locke, no Macaulay, no Adam Smith, no Fielding, no Charles Lamb, or no Dryden in Australia, and that the most eloquent political speakers he has in his country to-day are mere pigmies and potato pips when compared with such men as Pitt, Fox, Burke, Sheridan, Curran, Robert Emmet, and Gladstone of the old world, or Jefferson, Lincoln, Daniel Webster, Wendel Phillips, or Washington of America—when he comes to realise these things, I say, he will value the treasures that are hidden away between the covers of thousands of volumes that adorn the shelves of our Schools of Arts; he will then devote less of his leisure hours to discussing the colour of his cows and the quality of butter and milk cans; he will live in a more intellectual atmosphere at home, and when a candidate for political honours comes along, and asks him to believe that his country and his lands are in danger of being raided and annexed by a tribe of New Guinea savages, as one did the other day, he will vote for that politician with bricks and empty gin-cases and cowhide.

“I repeat, that it is from the country, from men like yourselves, that Australia must look for men to shape her destinies. There is no atmosphere so inspiring to thought and reflection as that of the country. On the shaft of a dray, on the seat of a mowing machine, or between the handles of a plough a man might shape a successful play, or an epic poem, or he may solve a great political or industrial problem. And on this point I will quote a passage from an article written by Washington Irving. He said: ‘To this mingling of cultivated and rustic society may also be attributed the rural feeling that runs through British Literature; the frequent illustrations from rural life, those incomparable descriptions of nature which abound in the British poets that have continued down from “The Flower and the Leaf” of Chaucer, and have brought into our homes the freshness and the fragrance of the dewy landscape. The pastoral writers of other countries appear as if they had paid nature an occasional visit and become acquainted with her general charms, but the British poets have lived and revelled with her—they have wooed her in her most secret haunts—they have watched her minutest caprices. A spray could not tremble in the breeze—a leaf could not rustle to the ground—a diamond drop could not patter in the stream—a fragrance could not hail from the humble violet, nor a daisy unfold its crimson tints to the morning but it has been noticed by these impassioned and delicate observers and wrought up into some beautiful morality.’

“What the brain is capable of doing then, I say, is never fully revealed until it is put to the test, and no man knows what he can do, or what he can’t do, until he tries. There is no doubt in my mind that some of us are born with better brains than others; some are endowed, perhaps, with greater natural gifts, but every brain that isn’t made of cheese or jelly or greenhide is capable of being improved and expanded. Like soil it will grow weeds and Bathurst-burr until it is cultivated, and profitable seed planted in it. And like soil again, it will raise weeds and Bathurst-burr after it has been cultivated, if neglected long enough. And that to be able to express his thoughts intelligibly and forcibly a man must necessarily be a born writer, or orator, is absolute bosh. Ambition and work are the secrets of the success of it every time. First cultivate the art of thinking, and the rest must follow with more or less success—mostly less, no doubt. Because a man is not naturally a gabbler it does not follow that, given a set of competent ideas, he will not be able to clothe them in suitable and attractive language. Just you try it. I think it was Johnson—not the one down the road who runs your pub—who so wisely said: common fluency of speech in many men and most women is owing to a scarcity of matter and scarcity of words; for whoever is a master of language, and has a mind full of ideas, will be apt, in speaking, to hesitate upon the choice of both; whereas common speakers have only one set of ideas and one set of words always ready at the mouth. So people come faster out of church when it is almost empty than when a crowd is jostling at the door.’

“And now, gentlemen, I come to what seems to my humble understanding to be the saddest and most lamentable aspect of the defects and deficiencies in the life of the farmer as he lives to-day. It is a delicate matter to touch on, perhaps, but it is of such vital importance to a nation such as Australia promises to be, that I wouldn’t be doing my duty if I shirked it, or attempted to talk round it. My remarks on the matter, of course, are not intended to be personal. Don’t misunderstand me for a moment. It is always etiquette that on occasions such as this present company should be excepted; but were you all sitting outside on the fence, instead of round this room, I dare say I might strain a point to include the lot of you! As I promised before to say again: the farmer’s one and only aspiration in life is to accumulate coin, and become wealthy and fat and to leave those dependent upon him even wealthier and fatter than himself. The only, goal he is making for, on this side the grave, is the goal of the money-grub. And he is quite conscious of his aspiration, too; but he is utterly unconscious of the fact that it is only aspiration. The farmer doesn’t realise the pride of place he should hold in the community, not a bit of him. His importance to Australia he hasn’t yet started out to think about. He doesn’t know who he is, or who he ought to be, even. And the priceless heritage which is his in the shape of picked, landed possessions in a young and enormously wealthy country, with unlimited resources undeveloped, such as Australia is, and, with the future—barring an invasion — that lies before her, he doesn’t appreciate, because he hasn’t awakened to the fact that he holds such a heritage. It doesn’t even stand out as a dim circumstance to him yet. If it did, he would surely begin to take some pride in such a treasure. He would begin to pay more respect to the surface of things. He would spend a little time and money and taste in setting it off with touches of art and ornamentation. He would, surely, with advantage to himself and Australia, begin to hold his head a bit higher; and to differentiate between the proprietor of the farm and the man who is employed to milk the cow. A visitor from foreign lands, coming to Australia, I venture to say, would not be able, unless accompanied by a guide, to walk on to any one farm out of a hundred in Queensland and say which was the man who signed the cheques, and which the man getting his ten bob a week for milking the cow. It would be impossible for him to do so, because there is no external difference—no line drawn. And I do not say it out of disrespect for the man of wages. I mean it in a broad and national sense. In his eager, nervous haste to make, and horde money, the farmer loses all sight of the fact that it is necessary he should lend a little tone to his position. To do so is business; and instead of masquerading in false garbs the way he does—in the garbs of the ten bob a week man— if his possessions and himself were, to a modest extent, adorned with the symbols of position and prosperity, what a pattern he would become for others, and what a magnificent advertisement he would be to his country!

“To bring about such a state of things, however, it would be necessary to convince the farmer, that intellectual achievements are, after all, much more honoured, and more to be coveted than a purse bulging with boodle! And it is high time that some of the leisure moments, at least, on every farm, were devoted to acquiring its own little library, and the minds of the children directed to pursuits other than the everlasting cow-and-calf order, and disorder of things. Those children are inevitably destined to become wealthy, and let farmers see to it lest their offspring may, one day, find themselves humiliated like the Duke of Bedford, when he protested against a pension being granted to Edmund Burke. And when Burke replied: ‘It would not be gross adulation, but uncivil irony, to say that His Grace has any public merit of his own to keep alive the idea of the services by which his vast landed pensions were obtained. My merits, whatever they are, are original and personal; his are derivative. It is his ancestor, the original pensioner, that has laid up this inexhaustible fund of merit which makes His Grace so very delicate and exceptious about the merits of all other grantees of the Crown.’”

The book-man, puffing and perspiring, resumed his seat amidst silence. A restless, uneasy, uncertain feeling seemed to possess the audience.

Duncan seemed to understand the feeling. He leaned over and whispered into the ear of the lecturer:

“By crikey! I dinna like the look o’ them. Their eyes are glaring and rolling like wild cattle’s. Ye’ve stirred their bluid. Tak’ that glass i’ ye’re haun’ to mak’ it believe ye’re gaun for a drink an’ go out that door near by an’ run like the vera deil till ye reach my place, or they’ll rend ye soul an’ body.”

The lecturer took up the glass and went out. And Duncan to hold the audience in check, jumped to his feet and, waving a volume of Pickwick Papers about, said:

“Well, now, I’m blawed if I ken mysel’ what a farmer wants wi’ a’ this readin’ that Meester Jones hae talked aboot. I’ve got a beggarin’ book here that someone gi’ed my wife. Four or five bloomin’ people tried to read it before I had a go at it. One o’ them got as far as that, page 10”— (displaying a corner turned down)—“another got up to that, page 14. Another had enough when he got to page 20”— (displaying another “dog’s ear”)—“and I mysel’ stuck to it like th’ deil till I reached page 51, which was a lot further than any o’ th’ ithers got; an’ I’ll stake my bloomin’ soul there’s no man livin’ or dead who’ll get any further wi’ it.”

Then McGrundy jumped up and said: “Anyhow, I reckon this cove’s quite right in everythink he said, and farmers don’t read or think half what they ought to. I know that from meself.”

Tom Ryan rose and said the same.

Duncan stared hard.

Bill Murray and Sam Thomas added their approval of the lecturer’s sentiments. The whole gathering, in fact, agreed with him, and began to express wonder at his long absence.

“Crikey!” Duncan drawled in explanation, “I thocht by the glint i’ ye’re een that a’ you chaps were sair offendit at what he eensinuated an’ I advised him tae sneak oot an’ slither hame.”

As time went on Duncan McClure prospered and became a power in the land—that is, in the land round Narralane. His honesty of purpose, his broad human sympathies and even his Scotch hardheadedness, commended him to the worthy folks who dwelt in his community. No doubt he was a bit of a rough diamond, and more than one shady customer had cause to remember that he was not a man to be trifled with; but, on the other hand, no one in trouble or distress had ever appealed to Duncan in vain. Having fought an uphill fight himself and by sheer grit reached a point of comparative opulence, he was always willing to lend a helping hand to the man or woman struggling against odds.

That was why the poor parson had found a friend in Duncan McClure. The keen, observant Scotchman had watched this “labourer in the vineyard” for a long time, had noted and admired his indomitable pluck, notwithstanding the poor yield of his harvest, and, in his own bluff and hearty manner, had become his friend.

Not only the poor parson himself but Mrs. McCulloch, his wife, had reason to look upon McClure as the friend in need who is a friend indeed, and no farm in the district showed the minister’s family more hearty hospitality than “Loch Ness.”

And the poor parson needed all the help he could get from such as Duncan, for his work was hard and often thankless. Long journeys in blazing heat or driving rain by day or by night, visiting the sick, comforting the afflicted, or mayhap assisting at a wedding or a christening. If any of his parishioners were in trouble he was expected to visit them and say the word in season or endeavour to help them with a bit of good advice. For, as often as not, the “trouble” was more mundane than spiritual and the parson was frequently the means of tiding things over or showing a way out. Apart from sudden calls it was the poor parson’s custom to visit the outlying portion of his parish at stated times, making a round that would take him away from home for days at a time, and on these solitary journeys he often had food for reflection.

On this occasion he set out to make Archie McLennan’s place at the out-station gate before night, intending to start back to Narralane the following day. And as he jogged leisurely along beneath a canopy of the clearest blue the sleepy native bears, as he passed beneath them, lifted their woolly heads and peered down from their places in the forks of the towering trees. And now and again a weary, homeless traveller with a heavy swag on his back saluted him respectfully and inquired the time of day and the number of miles to the nearest water.

“Lord God,” the minister would murmur as he measured the magnitude of the great solitary bush at a glance, “open the eyes of the rulers of our nation to the wealth that is hidden away here, that they may direct the steps of Thy people to this land.”

And every fresh valley with limpid streams winding through it; and every towering belt of flawless timber, every undulating piece of plain land that his eye rested on, the same prayer unconsciously left his lips with increased fervour, till at last, about noon, he came in sight of Neil McLeod’s weird and humble habitation. It consisted for the most part of 160 acres of dense scrub, with here and there large holes cut in it to make room for the cultivation paddock and the house and yards. From a primitive point of view the holding was a picture—a grand work of art. Imposing walls of mountains were banked all round it, amongst whose silent gorges travellers were sometimes doomed to lose their way, and where men in the D.T.’s used to wander from Shanahan’s shanty on the new railway, and strip themselves of their clothes and run from tree to tree concealing themselves, and calling out, “They’re coming! They’re coming!” Ah, yes! there was a lot of grim humour lurking about McLeod’s lonely selection. There was a large family, too, of the McLeods, consisting of several strapping sons growing into manhood, and a number of robust, kindly-natured, fair-skinned girls. And as the poor parson approached the habitation, he saw them all grouped outside, with gloomy, downcast expressions on their faces, watching two men rounding up the few head of milking cows which formed the nucleus of the prospective dairy herd that they had for many years dreamed of raising—and the family’s hope and main-spring of support—and putting them in the yard to check the brands.

The work of the day was all suspended, and none of the family seemed to have heart enough to do another hand’s turn about the place. The poor parson greeted them all cheerfully, and in turn they responded with a forced sickly effort at pleasantry. The girls hung their heads, and the boys pulled their slouch hats down over their eyes when taking charge of the horse after the minister had alighted from it.

“I hope no serious trouble has come to any of you, Mr. McLeod,” the minister said, noticing the gloom that was upon the tanned faces of all. Mrs. McLeod, with big tears in her kind, motherly eyes, looked at her husband and waited for him to speak. McLeod hesitated, and the girls moved quietly away and went inside the house.

“Well, yes, Mr. McCulloch,” the father, with a futile effort to treat his misfortunes lightly, said; “we have a bit of a bother to-day—we’re losing all the cows, as a matter of fact—and the horses, too!”

The poor parson didn’t seem to understand, and stared wonderingly from Mr. McLeod to the cows as they trooped into the yard.

“The storekeeper has sent the bailiff for them,” Mrs. McLeod said; then covered her face with her apron and sobbed into it.

The poor parson understood, and spoke softly and sympathisingly.

“Of course I would have paid the money,” McLeod said; “but when a man hasn’t got it, what can he do, Mr. McCulloch?” and he lowered his head and scratched the ground thoughtfully with the toe of his boot.

“I am very sorry,” the poor parson replied. “I can understand how hard and disheartening it must be to all of you. I feel it keenly myself, and how much heavier the misfortune must weigh on you. But don’t forget it could be worse, Mr. McLeod,” he added, “much worse—and you should thank God your trouble is only a financial one, which might be retrieved in many ways, and that it is not a serious illness or the death of a member of your family. For, after all, the loss of one’s worldly possessions is but a minor matter in our lives.”

“Ah, yes!” Mrs. McLeod answered. “Look at the poor widow woman, how she was taken away only the other night! And I’m sure that poor girl and boy would much sooner have lost every stick they had, and gone begging all their lives, than anything should have happened to their poor mother.”

The reference to the death of Mrs. Braddon was too painful for the poor parson, and he remained silent.

“Yes,” McLeod said slowly; “when you look at it that way we’re a good lot better off than we think.”

The girls called to their mother to invite Mr. McCulloch in for a cup of tea. And the bailiff, having finished checking the brands of the stock, rode across to have a final word with the boys, who were sitting on the ground with their backs to the barn, brooding over the situation together.

“I could only see three horses,” the bailiff said, referring to his note book, and reading out the descriptions of the animals.

“There should be five,” Jimmy, the eldest boy, said.

“I’m telling you I could only see three,” the bailiff repeated.

“Well, there was five,” Jimmy insisted in an antagonistic tone, “and I can show them to you,” and he rose to his feet.

“Well, I always thought a wink was as good as a nod to a blind horse,” the officer said; “but I’m beginning to think a man wants to carry a blackboard about with him in these parts. I’m telling you again that I could only see three of them.”

Jimmy gradually began to understand the ways of a humane bailiff, and with an intelligent look on his face drawled:

“Oh! I see—yairs, o’ course.”

Then the bailiff said “Good-day,” and rode off.

The poor parson, instead of holding prayers, asked for pencil and paper, and went carefully into the position of McLeod’s affairs with him, and showed how it was still possible to get sufficient credit from a bank to enable him to buy more cows and make a fresh start. And when he went away in company with Jimmy, who was to show him a short cut through the ranges to MacLennan’s place, the McLeods brightened up and became hopeful and light-hearted again.

Eight miles it was through the ranges to MacLennan’s, and from there the poor parson intended making back to Narralane the following day.

“There was somewhat of an unpleasant incident the last occasion on which I called at Mr. MacLennan’s place,” the minister remarked thoughtfully as the hut came in sight, “arising out of an extraordinary misunderstanding.”

Jimmy smiled, and said, “Yairs, we heerd about it.”

The minister looked quickly and concernedly at Jimmy and asked:

“Was it spoken of?”

“Oh, yairs—a lot o’ times.”

“In what light was it spoken of?” with deeper concern. Jimmy looked puzzled.

“Oh! just when any o’ them met, you know—daytime, I think, mostly.”

“I mean, what was the view they took of the incident—what was their account of it?”

Jimmy smiled again. Then drawled bashfully, “Well” (pausing), “they reckoned you” (another pause)—“perhaps it wouldn’t be right to tell you.”

The poor parson bit his lip, and a troubled, anxious look came into his face, and he stared at the hut which they were now drawing close to.

“Archie is not at home just now, though,” Jimmy said, in a consoling sort of way.

“Is he not?” with a look of fresh concern from the minister. “No—he’s been away for months, at the Burnett gettin’ sheep for the station.”

“And does Mrs. MacLennan stay all alone?” the minister asked.

“One o’ me sisters was stayin’ with her for a while, but she’s home again now, and me mother, I think, is comin’ over tomorrow or the day after, to stay with her for a month.”

They passed through the station gate, and an aged cattle-dog came whimpering to meet them. The animal sprang up at the heads of the horses, and clawed the trouser leg of the poor parson; then rushed back to the hut, and stood whining and wagging its tail at the half open door.

Jimmy, who understood the language of dogs better than he did that of bailiffs, said apprehensively:

“There’s something up here; that dog wouldn’t go on like that if there wasn’t.” And he sprang actively out of the saddle,

The dog disappeared inside, and rushed into the bedroom.

Jimmy knocked on the half-open door, and called out.

There was no reply. He called again.

The dog answered with a loud hollow bark from the bed-room.

“There’s something wrong right enough,” Jimmy, with a nervous tremour in his voice, said to the minister; then boldly entered the house.

The minister, with a look of alarm on his face, followed.

Mrs. MacLennan lay in bed; and through the open bed-room door they saw the dog standing looking up into her face.

“Anything the matter, Mrs. MacLennan?” Jimmy asked.

“My God!” Jimmy gasped. “I believe she’s dead!”

The dog bounded on to the bed, and stood whimpering over his mistress.

“My God!” Jimmy gasped again, as they both entered the bed-room and scanned the face of the woman. “She is dead!”

The poor parson, pale and trembling, lifted the hand that lay stiff and cold on top of the blanket.

“Lord God! have mercy!” he exclaimed, reeling back and putting his hands to his head.

For a while Jimmy stared hopelessly at his companion; then murmured: “What on earth can we do?”

“Lord God!” the poor parson muttered.

“I think we ought to see if there’s been foul play,” Jimmy said, and leaned over the dead woman. “No!” he exclaimed. “I think” (pausing and watching the woman’s face closely), “I think she’s still alive.”

The minister lifted the limp hand again, and felt the pulse long and anxiously. “There is yet life,” he said. “Go you, friend, and tell your people. I will remain and watch over our sister.”

“It’ll be terrible for you to do that,” Jimmy answered feelingly, “for it will be all night, nearly, before anyone can arrive.”

“It will be terrible—duty is often terrible. But go; do not delay—and the Lord guide you in safety.”

“My heavens!” Jimmy murmured as he swung into the saddle. “In there all night alone!” and his hair rose on end at the very thoughts of the awful situation, as he galloped through the darkening timber.

The minister set to and made a fire, and searched the shelves of the humpy for whatever home remedies they contained, and applied them to the patient. Then hour after hour went slowly by. The night birds called gloomily to each other. At one moment they whooped funereally and with the doleful regularity of a bell tolling for the dead. At another they filled the air with screams, that sounded like the cries of lost souls in pain. Every now and again a dingo would “Coo-ee” mournfully, and, when the echo had died slowly away, another would answer back. And the dawn was almost breaking when the first cart, containing McLeod and Mrs. McLeod, rattled over the loose stones, and passed through the gate.

Catching the sound of the minister’s voice within, McLeod, as he stepped on to the rough, boarded verandah, placed his hand on his wife’s arm, and they both paused and listened.

In deep, solemn tones came the words: “Our Father, who art in heaven: Hallowed be Thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive our debts, as we forgive our debtors. And lead us not into temptation: but deliver us from evil: for thine is the kingdom, the power, and the glory, for ever and ever. Amen.”

The Stewarts later entered the house.

“Thank heaven!” the minister murmured, and, spreading his arms on the rude table at which he was sitting, rested his head on them.

Mrs. Stewart took charge of the patient, and administered a little brandy to her, and an hour or so after, and just when the doctor arrived, there were sure signs of recovery. By the afternoon she opened her eyes, and murmured things to those about her.

And, later in the day, as the poor parson returned slowly towards Narralane, he was met by a bearded tan-faced drover, leading a pack-horse and riding along at a swinging pace. The horseman steadied his speed when approaching, and respectfully moved his hat. But the minister didn’t remember Archie MacLennan, and they both passed on.

A fresh misfortune was upon the Narralane congregation. A storm had swept over the country and carried away the church. And it was the only building in the district that it had carried away—not even a barn, or the frailest old bark humpy in the district had been affected by that hurricane.

“I canna understan’ it at a’,” Duncan McClure said, gazing in solemn wonder upon the sacred ruins of the fallen edifice.

“Nor me,” Bailey, the storekeeper, sighed, shaking his head

Neither could the poor parson. He stood and stared dejectedly at the catastrophe in silent amazement.

“Well, m-m-m-man proposes,” Bill Eaglefoot said, closing his eyes and shaking his head spasmodically, “but the Lul-Lul-Lul-L-Lord disposes.”

For the moment Bailey seemed to entertain doubts as to the reverence of Bill’s observation, and closely watched to see how it would be regarded by the parson.

“Yes, friend,” the parson said, bestowing a soft look of approval on the ragged, useless-looking reprobate.

“You never said a truer word in your life, then,” Bailey promptly said, patronisingly, to Bill, “if it isn’t the only true word that ever y’ did say,” and he turned his eyes on the others assembled round the debris, like mourners at a grave, and he turned his eyes on the others assembled round the débris, like mourners at a grave, and chuckled ignorantly.

Bill, who, upon being complimented by the poor parson, felt like walking on air, now suddenly took umbrage.

“I suppose y-y-you think,” he snapped, stepping off the end of the damaged pulpit, upon which he had been standing with both feet, and looking Bailey, the elder of the church, right between the two eyes, “that that’s m-m-my own ph’losophy?”

“I didn’t know it was philosophy, Bill,” Bailey replied, grinning at the others again.

“No, o’ course y-y-y-you didn’t,” Bill sneered, mounting the end of the broken pulpit again. “And I don’t s-s-s-suppose you ever heard o’ Bub-Bub-Bub-acon, did you?”

“Bacon!” Bailey chuckled; “I’ve eaten plenty of it,” and laughed at his own greasy joke, until the others, to Bill’s discomfiture, joined in the merriment.

Bill shuffled his feet nervously, and bit his lip, and scowled.

“Hae ye ever heard o’ Robbie Burns?” Duncan McClure asked, stepping forward and fixing his twinkling grey eyes on Bill in a defiant sort of way.

The parson smiled amusedly at Duncan.

“I dinna mean you, pairrson,” Duncan put in quickly, as though anticipating the minister meant to assist Eaglefoot by disclosing the identity of the Scottish poet. “I’m askin’ Bill the question, seein’ he seems to ken sic a deil o’ a lot.”

Then, turning to Bill again, “Hae ye ever heard o’ Robbie Burns?” And Duncan glared as though he had Bill in a tight place.

The others grinned in favour of Duncan.

Bill, in sheer disgust, turned his face away, and looked across the landscape.

“I kenned he hadna,” Duncan concluded triumphantly. Then, placing his heavy foot on Bill’s instep to attract his attention again, said: “Hae ye ever heard this before?” And, in a broad, sing-song voice, he proceeded to recite:

“O, ken ye hoo Meg o’ the Mill was mairrit?

O, ken ye hoo Meg o’ the Mill was mairrit?

The priest he was oxter’d, the—”

Duncan paused and tried to think, but couldn’t remember any more.

There was a loud laugh. The poor parson smiled at Duncan and walked away, and Duncan mopped his brow laboriously and looked triumphantly at Bill.

“Look here,” Bill said, turning on Duncan, “that th-th-ing was old a hundred years before Bub-Bub-Bub-ums was bub-bub-orn.” And he stepped off the battered pulpit and went away.

“Puir Bill,” Duncan said, rejoining the minister, “his skull’s a wee bit crackit, pairrson.”

But the rebuilding of the church was all that was on the parson’s mind. He invited those around him to the shade of a tree, and placed the serious aspect of the situation before them. After consulting for an hour they decided to hold service one night during the week at “Loch Ness,” and, at the conclusion of it, the church committee would meet and “do something.”

The sun was down, and the shades of evening were stealing silently over the great Bushland. At “Loch Ness” the last can of milk was emptied at the dairy; the cows were sauntering in twos and threes from the yard; the plough horses, still wet with sweat, ravenously feeding from the nose-bags; while across in the mountain hollow the jackasses were laughing in mocking refrain at the departing day.

“The boys reckon they can see the auld pairrson comin’ roond the corner o’ the paddock, but I’m hanged if I can, Vi!” Duncan McClure said, as he reached the kitchen and proceeded to wash his face and large, brown arms in a capacious tin dish of water that stood on a wooden bench beside the door.

Mrs. McClure hurried into the front room, which had been reserved for the holding of the service, to see that everything was in order and to put the cards away. Then she returned to the kitchen and started laying the table.

“I suppose we’ll have to tak’ supper in the kitchen th’ nicht, Vi,” Duncan went on, squeezing water from his whiskers and rubbing his face hard with a coarse towel.

Mrs. McClure hoped the minister “wouldn’t mind.”

“Be th’ hokey, he’ll have to like it, Vi!” came from Duncan in loud good-natured tones. “He’s no a bit better than the rest o’ us.”

“Ye shouldna speak so disrespectfou, Duncan,” Mrs. McClure said, flying about.

“Besides the meenister should receive more consideration than common folk.”

“I don’t think that, Vi,” Duncan called at the top of his voice. “And if I was an auld pairrson mysel’, I don’t think I’d—”

“Good evening, Mr. McClure,” came, in soft, silky tones, from the edge of the kitchen verandah.

Duncan looked round.

“By joves!” he shouted delightedly. “I’m beggared, it’s Mr. McCulloch himsel’! We were jist talkin’ about ye, pairrson; and hoo are y’ gettin’ along?”

The poor parson smiled and said he was getting along very well. Then he mounted the verandah and shook hands with Duncan and with Mrs. McClure, who came from the kitchen with her homely-looking face radiant with smiles.

“What hae ye done wi’ your horse?” Duncan inquired, seeing the minister had appeared without the quadruped.

“Your man took charge of him at the yard gate for me,” the other replied.

Duncan looked surprised.

“Auld Bill, was it?” he asked out of curiosity.

The parson smiled, and said it was.

“Weel, weel,” Duncan drawled. “Fancy that, Vi! The auld sinner! I didna think he had sae much intelligence.”

The parson spoke up for Bill, and paid him several compliments upon his usefulness as a groom.

“He’s comin’ to the service the nicht, pairrson,” Duncan said in a hushed voice and with an amused look in his face.

The parson was pleased to hear of Bill’s good resolution, and related an instance that he knew of respecting a hardened criminal who had been reclaimed by the church and lived a good Christian life ever after.

“Well, that’s what he’s been tellin’ the boys, pairrson,” Duncan drawled. “But I think, mesel’, the auld deil ’ll sneak oot o’t as soon as he gets a skinfou o’ grub.”

Then he lifted the tin dish he had sluiced himself in, and, turning round, heaved the water over the verandah, just as Bill, in search of his supper, hobbled round the corner.

“Gosh, man!” Duncan exclaimed, apologetically, on seeing the contents of the dish go over Bill and wash his hat off.

Bill threw up both hands and gasped for breath.

“Oh, dear!” the parson muttered pityingly, turning his eyes on Bill.

“I didna see y’ comin’, man.” Duncan chuckled amusedly at the drenched reprobate. “I didna.”

“Well, y’ mighter taken th’ soap out of it!” Bill stammered in injured tones, as he rubbed his eyes.

Duncan’s features instantly relaxed.

“Oh-h!” he said, leaning over the edge of the verandah, and peering concernedly at the ground about Eaglefoot’s feet,. where the lump of yellow soap lay. “Han’ it back, han’ it back, man!”

Bill shook the water off himself like a dog, and stooped and handed Duncan back the soap. Duncan replaced it in the dish, then turned to the parson.

“I was gaun tae ask ye, when a’ that happened, if ye would care to hae a wash yoursel’, pairrson?”

The parson had remembered the day had been excessively hot, and thought he would.

“Wait a wee till I fill the dish for ye.” And Duncan tripped off to the tank, and returned with the dish brimming over.

Mrs. McClure protested.

“Why could ye no tak’ Mr. McCulloch into the bedroom to wash himself, Duncan?” she said.

The parson smilingly assured Mrs. McClure that he would sooner wash in the tin dish, and, removing his coat, carefully rolled up his limp and soiled shirt cuffs.

“An’ it’s a lot better, pairrson,” Duncan said, with an air of assurance; “for ye canna wash a’ the dirt aff yoursel’ in a bedroom.”

The minister lifted the soap and began his ablutions with a graceful action.

“Stan’ away back frae it, pairrson,” Duncan said, “and poke your heid richt under; it’ll cool ye after a’ the heat.”

Mrs. McClure scowled at her voluble husband, to silence him; then she suggested that he proceed with the carving while the others were getting ready.

“A’ richt, Vi!” Duncan answered boisterously, taking his place at the head of the kitchen table, and proceeding to slash into the round of corned beef which had just been lifted steaming hot from the pot; and, when he had filled every available plate, called out loud enough to be heard at the barn: “Ye’d better come noo, all o’ ye, an’ tak’ your seats afore the grub gets cauld.”

Bill Eaglefoot was first to respond. Bill always believed in promptitude at meal-time.

“Hello, Bill,” Duncan said, with a good-humoured grin; “had ye tae change your shirt?”

“No!” Bill growled. “But I w-w-ould have if I h-h-had another to p-p-p-put on.” And, squeezing himself into a seat behind the large family teapot, he commenced his meal right away.

“Come along, Mr. McCulloch,” Mrs. McClure called out, and the minister entered, and was given a seat on Duncan’s right hand. Then came the young McClures and the two ploughmen, who hesitated at the door and looked nervous in the presence of the Church.

Duncan turned to the minister:

“Eh, mon!” he exclaimed in admiration, “but it’s made a great change in ye, pairrson,” and the minister smiled feebly.

“Duncan!” Mrs. McClure said, speaking from the bottom of the table. “Ye shouldna pass remarks.”

The rest of the company smiled, and stole sly glances at the minister.

“But there’s a difference, richt eneuf,” Duncan insisted stubbornly. “An’ do ye no feel it yersel’, pairrson?” he asked, appealing to the minister.

“Did ever ye hear sic a man?” Mrs. McClure said to Bill, who was sitting handy to her at the table.

But Duncan wasn’t to be interrupted.

“These hot days, ye ken,” he continued, by way of explanation, “a man perspires a deil o’ a lot, an’ the dust a’ gets on ye, and after ye hae a wash and get it a’ aff, ye feel like anither fella—ye dae, don’t ye?” and he looked at one of the ploughmen for confirmation. But the ploughman had no wish to be drawn into conversation at the table, and only grinned and looked away.

Duncan, after a pause, turned to the minister again.

“But I don’t suppose ye sweat very much, dae ye, pairrson?”

“Duncan! Duncan!” Mrs. McClure cried again, and Eaglefoot, in the act of putting a potato into his mouth, changed his mind, and, dropping his fork, broke into a low, audible chuckle. The others followed his example.

Duncan put down the carver. “Ask a blessin’, pairrson,” he said in solemn tones.

The minister bowed his head and said:

“For what we are about to receive the Lord make us truly thankful. Amen.”

Old Bill, who had been eating all through the piece, looked from one to the other with a half-shamed expression on his face.

Mrs. McClure, noticing his discomfiture, leaned over the corner of the table and whispered, “It doesna matter.” And Bill took fresh courage and began the meal all over again.

It was a quiet, uneventful repast. No one but Duncan and the parson conversed, and as the others finished they rose and shoved their seats back against the wall, and sat there stiff-backed, telling each other in turn that it had been a lot hotter that day than the day before.

An hour later the dogs started barking, and the sound of voices and the tramping of horses were heard in the yard.

“They’re beginning to come,” someone said, and Bill and the ploughmen, glad of an excuse, rose and went out.

“Well, I suppose we had better licht up the kirk,” Duncan said to Mrs. McClure, then went off to the sittingroom, where some chairs and the side-boards and tail-boards of drays, resting on gin-cases, awaited the congregation.

After Bailey and some more of the elders supervised matters, and readjusted the seats, and Mrs. McClure had explored the kitchen for an extra candle or two, the minister entered and took his seat behind a little table which served as a pulpit. Then the weird, heavily-booted congregation trooped into the dimly-lighted room, and, taking their seats nervously, sat staring expectantly at their pastor.

Duncan McClure gazed all round the room, and turned and looked to see who was sitting behind him, then leaned across to his son Peter, and whispered:

“I dinna see that auld deil, Bill.”

Peter smiled and shook his head sceptically. Peter was a nonbeliever where Bill was concerned.

“Gang oot, Peter,” Duncan whispered again, “and ask him in.”

Peter rose and went out. But Bill was not about. Bill was on his way to Charley Jorgens’s place, on the parson’s horse. Charley Jorgens was a particular friend of Bill’s and owned a horse and dray with which he used to make a living collecting dead bones and things that other people didn’t take any interest in. And sometimes he collected things that other people took a lot of interest in.

Peter returned, and, taking his seat again, shook his head in the negative.

“The leein’ auld deil!” Duncan whispered in condemnation of Bill; then turned his attention to the parson.

The poor parson was not an eloquent preacher, but he was earnest and impressive, and his words held the congregation in rapt attention. They all sat motionless, their eyes rivetted solemnly to the floor, listening intently.

The parson proceeded to outline the steps and stages of a criminal’s life. On the left-hand wall of the room he pointed in an imaginary way to the infant in its mother’s arms, and, in touching tones, said, “Innocence.” On the right he pointed to the criminal in chains, and exclaimed, “Guilt.” Tears came from the women’s eyes, and the men exhibited restlessness.

The parson, in emphasis, struck the open Bible that lay before him on the improvised pulpit, and a nest of startled cockroaches, glossy-backed, well-fed and full-whiskered, unexpectedly fell from the table. The vermin raced across the floor; but, when Mary Archibald gave a start and moved her skirts, they wheeled in irregular order, and scampered towards Duncan McClure. Duncan, who hadn’t noticed them at first, suddenly opened his eyes and moved his foot. The cockroaches turned again and raced back under cover of the table, where they remained together, shouldering each other about and blinking at the audience.

The congregation grinned, and Bill Andrews nudged Tom Smith. Tom Smith struggled to retain his composure. Mary McBrown raised her eyes meaningly to her mother, and they both turned red, and took out their handkerchiefs and coughed into them. When they coughed, the cockroaches started nervously, and seemed inclined to scatter, but took courage and settled down again, and blinked more and more at the congregation.

Willie Smith nudged old Macfarlane; old Macfarlane turned his head slowly, and, scowling at Willie, whispered hoarsely, “Hae some sense.”

The congregation seemed to lose interest in the sermon altogether; their minds were all on the cockroaches. Presently the parson thumped the table again, and added a new interest to the proceedings.

The “Jack of Hearts,” and the “King of Clubs,” and the “Ace of Spades,” and the “Queen of Diamonds,” followed by a number of “rags,” dropped out of some part of it and fell on the backs of the unsuspecting vermin.

All but one scattered suddenly. The one remained concealed under the “Ace of Spades” and the “Queen of Diamonds.”

“O-o-h!” Mary McBrown whimpered, involuntarily, as some of the vermin arrived hurriedly at her feet. Her mother pinched her to silence her; then they both made a choking noise and smothered their mirth. But Bill Thompson, from the opposite side of the room, laughed outright, and, rising clumsily, made for the door.

The parson paused for a moment and stared at Bill; then continued his sermon without remark.

The congregation settled down, and were becoming absorbed again in the minister’s words, when the “Ace of Hearts” and the “Queen of Diamonds,” balanced across each other, began to show signs of animation, and moved slowly across the floor towards Mrs. McClure.

The congregation lost its solemnity altogether, and made a noise like geese. The parson stopped abruptly, and eyed them warningly.

Duncan McClure glared at them and shook his head, then chuckled himself.

The poor parson, with a dark look on his face, gave out the next hymn—and saved the situation.

The congregation made a great noise finding the place in their hymn books, and, rising hurriedly, sang and laughed in the same key.

The service ended; and Duncan McClure apologised to the minister for the unseemly merriment of the congregation. Then the Church Committee took possession of the room. On McClure’s suggestion, they decided to rebuild the church with their own labour, and to put the first nail in it the following morning. Then they shook hands with the parson and with one another, and went home.

Next morning the committee met at the appointed hour, each burdened with some portion or other of a carpenter’s kit. But they didn’t make a start on the church. There was no church to start on. It had all disappeared in the night.

And when Duncan McClure returned home, he found Bill Eaglefoot had disappeared, too.

Bill was helping Charley Jorgens to build a new house.

The Morrows were poor North of Ireland people, and lived on a selection at the Grass Tree.