an ebook published by Project Gutenberg Australia

Title: That Droll Lady

Author: Thos. E. Spencer

eBook No.: .html

Language: English

Date first posted: 2024

Most recent update: 2024

This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore

Mrs. McSweeney At A Bazaar

Mrs. McSweeney Has Visitors

Mrs. McSweeney Goes To The Zoo

Mrs. McSweeney At A Picture Show

Mrs. McSweeney At The Review

Mrs. McSweeney At The Gardens

Mrs. McSweeney On Microbes

Mrs. McSweeney Goes House-Hunting

Mrs. McSweeney Has A Turkish Bath

Mrs. McSweeney Moves

Mrs. McSweeney Goes A-Fishing

Mrs. McSweeney Up The Blue Mountains

Mrs. McSweeney Goes To Vote

Mrs. McSweeney On Troglodytes

Mrs. McSweeney Has A Cold

Mrs. McSweeney At A Euchre Party

Mrs. McSweeney Plays A Part

“By the Holy Shmoke,” exclaimed Mrs. McSweeney, jumping from the rocking chair in which she had been gracefully reclining, “’tis a quarther to five. Pat will be home at six, and not a praty peeled.”

“But the clock only sthruck three,’’ said Mrs. Moloney.

“That’s why I know it is a quarther to five,” said Mrs. McSweeney. “Faith! I’d back that clock agin the sun. If you wind it up oncet a week, pint the minute hand on ten minutes every mornin’, and allow for the variations, you can always be sure of bein’ wdhin ten minutes of the post office clock. But I must attind to me praties or there’ll be the divil to pay and nothing to pay him wid.”

“I’ll come and help you,” said Mrs. Moloney, “and we can talk as we peel them.”

Mrs. McSweeney led the way to the kitchen, lent Mrs. Moloney an apron, and, as they dropped the parings into the same tin dish, the conversation, which had been interrupted by the striking of the clock, was resumed.

“Where was I?” said Mrs. McSweeney.

“You was just going to tell me about the bazaar,” said Mrs. Moloney.

“So I was,” said Mrs. McSweeney, “Well, if you want to begin a thing properly, I suppose there’s nothin’ like beginin’ at the beginning so I might as well tell you phwat led up to it. You know the youngest Miss Simpson, the one wid the crooked nose?”

“The one wid the pimple on her chin?” said Mrs. Moloney.

“’Tis not a pimple, ’tis a wart. They say she has them all over her. But that’s the one. She came to me a fortnight ago last Friday. Let me see. Was it a fortnight, or was it three weeks? Maybe ’twas three weeks. Anyway, ’twas the day Miss Tompkins’s cat sihtole me kidneys, for I was just accusin’ her of it over the back fince when the door-bell rang. Miss Simpson, the one wid the crooked nose, I think she’s the youngest, but anyhow it doesn’t matther because neither of ’em will ever see forty agin, she came and asked me if I would help them wid a bazaar they was gettin’ up for the purpose of supplying boot polish to the Solomon Islanders.”

“Sure,” says I, “phwat do I care whether they have boot polish or not?”

“Nobody cares,” she says, “but we are gettin’ up a bazaar, and when you get up a bazaar you must get it up for something.”

Then she praised me new fire screen, and went on, “You know, Mrs. McSweeney, ’tis the fun we want. All the nice people will be there. We have the pathronage of two real live mimbars of parlymint, three aldhermen, a publican, and the wife of a pawnbroker. With the exception of the mimbers of parlymdnt, they are all givin’ something to the bazaar, and we want you to be in the fashion and give us a conthribution.”

“And why,” says I, “ain’t the mimbers of parlymint givin’ somethin’?”

“They are givin’ their names,’’ she says. “That is the fashion wid mimbers of parlymint.”

Well, she got round me that way, that I tuk a ticket and promised a contribution.

I didn’t know phwat to buy them for the bazaar, so I consulted Mrs. Broadfoot, who knows all about bazaars, her husband bein’ a policeman. She told me that it was not considhered the thing to buy anything for a bazaar, the proper thing to do was to make something.

You know, Mrs. Moloney, that if I pride mysilf upon anything it is my cooking, and I have reason to do so, as you can witness by frequent experiences. So I made up my mind to make a cake for the bazaar. Knowin’ that the mimbers of parlymint and the aldhermen were great judges of cakes, bein’ so much among ’em, I tuk the greatest pains to make it, and mixed it, as they say, regardless of expense. The day before the openin’ of the bazaar I sent it to Miss Simpson wid a shmall boy and my complimints.

I got a new shampane shantung dhress for the occasion and a chanticlere hat wid a rooster on top surrounded wid poppies.

I thought I’d be late for the openin’, as I was behind toime in shtartin’ owin’ to Pat bein’ late home for his lunch and havin’ to wash up and the kitchen chimbley catchin’ fire just as I was shtartin’ to get ready. It was a mercy the greengrocer happened to call at the toime because, although I had my hair down and nothin’ on but a wrapper, he put some bags over it and extinguished it before any great damage was done.

When I did get my dhress on I perspired that way that I burst a hook in my hurry and had to take it off to sew it on agin. When I got to the bazaar I found that although I was a half an hour late I was a half an hour early. I was gettin’ tired of shtandin’ in the crowd and one of me corns a shootin’ when the Ministher for Public Functions arrived wid his wife dhressed in a frock coat and a tall hat

He made a beautiful speech and tould us how the Solomon Islanders were all livin’ in a shtate of cannibalism, owin’ to never havin’ known the civilisin’ influence of boot polish. He complimented the ladies who had got up the bazaar, he praised the mimbers of parlymint, and the aldhermin and the publicans, and the pawnbroker’s wife, and declared the bazaar open. He then bought a sixpenny buttonhole from the mare’s daughter and wint away to open another bazaar.

Before he wint, I was inthrojooced to him. When he caught me name he shmiled. “Mrs. McSweeney is it?” he said. “Faith, I have heard of you. I look upon you,” he says, “as one of the mainstays of the Governmint,” he says, “While the people have your advintures to read,” he says, “the counthry will be safe. The people will be good timpered and continted and take no notice of the Governmint. Everybody will be happy,” he says, “for divil a soul could read them and be miserable.”

Afther he had gone the bazaar began in earnest.

“Will you buy a doll, Mrs. McSweeney?” said a sweet young female of uncertain age. “Only seven and six,” she says, “and it can say ‘Mum.’”

“I have no use for dolls,” says I, “me twins has grown out of them.”

Then another lady, wid a purple velvet gown, the wife of a publican, thrimmed wid sequins, wanted me to buy a pillow sham. Another one wanted me to buy a bar of scented soap in a green voile thrimmed wid insertion at twopence three farthings a yard. At last I was surrounded that way that I thought I’d burst another hook, and I said, “For the love of all that’s good, show me to the refrishmint shtall.”

“This way, Ma’am,” said a lady in shpectacles about five feet tin high and thin in proportion, and she led me down the hall between the shtalls on which were a variety of articles too numerous to mintion and a band playin’ and the flags a wavin’ till we came to a shtall at the far end of the room.

“This, Ma’am,” said the thin lady, “is me daughter’s shtall. She would like you to go into her lucky bag.”

“ME,” says I.

“Yes,” says she.

“Where is it?” I says.

“This is it,” she says, and she showed me a bag about as big as a minnow.

“And do you think,” says I, “that the likes of me cud get into the likes of that?”

“She would like you to take a chance in it for sixpence,” she says.

“I would not take me chance in it for a pound,” says I. Then I says, “I want the refrishmint shtall.”

“Well, ’tis before you,” said the thin womian wid a shniff.

I wint in the direction she pinted and there I saw the refrishmint shtall covered wid all sorts of nice things to eat, and Miss Simpson, wid the wart on her face dhressed in white muslin for all the wurruld as if she was only half her age.

“How do you do?” she says. “How do you like the tout ensemble?”

“The tout is all right,” I says, “but I don’t care much for the ensemble.” For I wanted to let her see that I knew as much about it as she did. “But,” I says, “I’m tired, and I want a cup of tay. Have you a cup of tay on you?”

“I can get you a cup in a moment,” she says.

“And I’ll thry a bit of the cake I made,” says I, lookin’ round for it.

“Oh, I’m so sorry,” she said, in a confused tone of voice. “You can’t. It’s sold.”

“Sold!” says I, “and how much did you get for it?”

“I got a shillin’ for it,” she says.

“Great Golliwogs!” says I, “and the engradients cost me four and six, to say nothin’ of me throuble and firin’ and the use of me shtove. Who bought it?” I says.

“My sisther,” she says. “When you sint it round yisterday we had some friends for afthemoon tay and my sisther bought it on the shpot.”

“Bought it for a shillin’,” says I.

“She bought it for the good of the cause,” she said, wid a toss of her head.

“Then I think,” says I, “that she ought to have let it be sold for the good of the Solomon Islanders. But anyway, can you get me a cup of tay?”

“I can,” she says, “if you will wait a minute.”

“I’ll wait here,” says I. And I looked round for somethin’ to sit on. There bein’ no chairs in sight and bein’ dead tired, I sat down on the corner of the shtail. I had no sooner sat down and put me weight on it than I found it was made of nothin’ but some boards laid on trestles. You could never imagine the result widhout bein’ there to see it. The end of the shtail that I sat on wint down, and all the rist of the shtall wint up. I grabbed at Miss Simpson, but she didn’t break me fall worth mintionin’. She wint down, and bang, I wint on top of her, and the refrishmints were distributed wid promiscuousness and indiscriminality over all the shtails in the vicinity, and elsewhere. A fancy goods shtall was liberally shpatthered wid calves’ foot jelly, loaves of bread went crashin’ into the middle of a china shtall, a knuckle of ham knocked over a large doll that was given by Mrs. Moses in a glass case, a blanc mange landed fair on the bald head of one of the mimbers of parlymint and slithered from his head down the neck of his wife in a low-neeked book-muslin dhress, and all was confusion and eatables. But this was only the fringe of it. Miss Simpson and I were in the centhre. The sight I was when they picked me up was beyond dishcription. I shtraightened meself as well as I could and wint away home. I saw the people on the thram laughin’ at somethin’, but it was not until I got home that I realized the extint of me rediculousness. I found that I had a lump of plum cake on the top of me rooster, a ham sandwich among me poppies, and a bath bun shtickin’ on the end of me hat pin. I found a jam tart in me transformation, and me dhress was a ruin. I wondhered next day phwat made the twins so quiet, and when I wint into the kitchen to see, there they were, as good as gold. One of them was pickin’ jujubes off me yoke, while the other was suckin’ me Shantung where I had sat down in a dish of chocolate creams. When I undhressed that night, conversation lollies rained from every garmint, and apple marangs oozed from me.

“Well, if you must go you must. It is just as well that phwat Pat said should be buried in obliviousness. Good bye. Don’t forget the shtep.”

“I’m so glad you’ve come,” said Mrs. McSweeney.

“I’ve been just dyin’ for somebody to talk to. If I don’t aise me moind I’ll bust, so I will.”

“I had to go up the road to get something for Moloney’s lunch,’’ said Mrs. Moloney, as she hung her umbrella on the gas bracket, “so I thought I’d step in and pass the time of day.”

“’Twas kind of you,” said Mrs. McSweeney. “I wanted to have a good talk wid somebody, and it might as well be you as anybody else. Did you know I have had visitors?”

“I heard you had someone staying wid you,” said Mrs. Moloney, “but I didn’t know they were visitors.”

“Did I ever tell you of me cousin, Mick Flaherty?” said Mrs. McSweeney. “I thought not. Well, ’tis a good many years ago now that he wint up the counthry to look for work, and he got a job on a station, and he did so well that he was able to take up a bit of land, and he shtarted farmin’ wid two cows and a few pounds in his pocket. It was not long before he got married to a native of the disthrict named Matilda. She was christened afther her father’s favourite cow. Poor Mick! He died suddenly, gettin’ through a fence wid a gun in his hand, not knowin’ it was loaded. He left her wid six childer and about a thousan’ sheep and several cows. The second eldest is delicate, and so she wrote and said she was bringing him to Sydney for a change, and as they ’d never been in Sydney before, could I put them up for a week. ’Twas a week they came for and they shtayed a month. ’Twas the longest month, Mrs. Moloney, I ever lived. My heart is bruck wid ’em. ’Tis not that I grudged them the bit they ate, far from it, but they got on me nerves. She only brought the sick one wid her, and I’ve been thanking Providence she didn’t bring the lot. I often thry to think that if one child that was sick could get into so much mischief, phwat would have become of me if she had brought the others that were well. And I give it up.

Before they’d been in Sydney a day he was teachin’ me twins to snare me neighbour’s cats in the back yard like rabbits. The second day he was down he was teachin’ ’em sheep shearin’ wid Mrs. Jones’s poodle dog. And although I sent her the hair, she swears she’ll have the law agin me. Me shtair carpet’s ruined wid ’em racin’ up and down like mad all day. Me linoleum is shpoiled through him runnin’ over it like a big draft horse wid hobnailed boots on, and me heart has been in me mouth for a month.

She would never go outside the door widhout me, and Payther (that was his name) would not let her go out widhout him. He used to follow her about like a foal afther a mare.

If I tuk them out I was never sure that I’d get them home alive. We were comin’ home from the Zoo one day and we had to change thrams at the railway. I turned round to buy a paper from a boy, and whin I turned agin there was Matilda and Payther shtandin’ right in the road of a thram that was comin’ towards them. I shcreamed to them and a gintleman dhragged them away just in toime to save their lives, and when I asked them phwat they meant by gettin’ in front of the thram, Matilda said it was all right. “The dhriver could see us there,” says she, “and he could have pulled his thram on one side.”

That was the way with them. They thought they knew everything when they knew nothing.

Last Wednesday bein’ a half holiday Pat said he would hurry home and take us to a picnic. He said he would lave wurruk early and be home at twelve 0’clock. I knew he’d want some hot wather to wash the dirt off his hands, so about five minutes to twelve I put the little kettle on the gas ring and lit the gas. Then I wint upsthairs to get him a clean shirt out and while I was away he came in.

He shouted out, “Where’s me hot wather?”

It’s on the gas ring,” I shouted back sat him.

“Why the blazes didn’t you make it hot?” he sings out.

“’Tis gettin’ hot,” I shouts.

“The gas is not alight,” he says.

“Well,” says I, “I cud take me dyin’ oath I lit it.”

Then I heard him sthrike a match and then— then—there was a bang, and his howls were like fog-horns.

I was down shtairs wid me heart in me mouth three steps at a time and there was Pat dancing about the kitchen wid half his whiskers singed off. When he stopped his dancin’ I asked him how he did it.

“How did I do it?” says he, “sure I never did it. All I did was to shtrike a match. All the rist did itself.”

“But wasn’t the gas alight?” says I.

“No,” says Matilda, “I thought it was burnin’ to waste, so I blew it out.”

I looked at Pat, and Pat looked at me. Then he looked at Matilda. By the look of him I cud tell phwat was in his moind, but he didn’t say it. He felt his right whisker, which was crumblin’ in his hand, and then, wid a big effort, he said:

“You will be obliging me, ma’am, the next time you touch the gas to lave it alone.”

“Oh! very well,” said Matilda, as she tossed her head, “the next time I see it wastin’ I will let it waste.”

“If you plase,” said Pat. And then he said, “Well, I suppose we must get ready to go to the picnic.”

“You’d betther look in the glass first,” says I, “and see how you fancy yoursilf wid half a whisker.”

“Howly Moses!” he shouted, as he looked in the glass. “I don’t know which I’m most like, a scarecrow or a birch broom in a fit. Nobody would take me for a man.” Then he scratched his head and sighed. “I’ll have to go and get a clane shave,” he said.

So off he wint to the barber’s shop while I put clane collars on the twins. Prisently he came back growlin’.

“Phwat’s the matter,” says I, “and why didn’t you get your shave?”

“Get me shave!” he says, in a tone of contimptuousness. “Isn’t it Widnesday?” he says. “’Twas two minutes past one whin I got there,” he says, “and the barber says it ’ud be more than his life was worth to shave me afther one o’clock on Widnesday. He’d be breakin’ the Early Closin’ Act and The Arbitration Act, and several more Acts of Parliament and be rindherin’ himself liable to be fined tin times over.”

“And phwat are we to do?” I says, as Matilda eame down all ready to go out, and wid Payther in a new pair of nickers.

“You can go up to the pub and get me a flask of whisky,” he says, “and then,” says he, “you can do what you bally well like. I’m goin’ to dhrown me sorrows in dhrink, and then I’m goin’ to bed, and I’m goin’ to shtop there until I can get a lawful shave. If I let anybody I know see me like this, the mimory ’ud haunt ’em.”

I had to get him the whisky and he wint to bed. Then I got out me mendin’, and when Matilda saw that I was settled for the afthernoon, she tuk off her things and went on to the balkiney wid Payther, and sat there till tay time. Pat had to lose toime next mornin’, owin’ to his toime of shtartin’ bein’ seven and the barber not openin’ till eight. When he came home that night the twins came runnin’ in and said there a sthrange man comin’ in to the gate. I didn’t know him mesilf till he shpoke, for he looked as much like Father O’Reilly as Father O’Reilly himself, and more so.

Counthry people are all right in the bush, Mrs. Moloney, but whin they come to town they don’t seem to fit their surroundin’s. Thinkin’ to get them a threat, I got some fish one day for dinner. At the table, Payther used to eat as if every moment of his life was goin’ to be the next. He used to ate his gravy, wid his knife, and he’d empty his plate quicker than I cud fill it. When he got helped to fish he shtarted at it as if it was the first meal he’d had for six months. He had only taken the second mouthful when he began to choke.

“What ails you, Payther?” says Matilda. But Payther kept on coughin’ and chokin’.

“Why don’t you speak to me, and tell me what it is,” says Matilda. But Payther. when he thried to shpake to her, only shpluttered and coughed the fish he had in his mouth all over me clane cloth.

“He has a fishbone in his throat,” says I.

“The idea of you givin’ him fish to ate wid bones in it,” says Matilda,

‘‘He should take his toime and look out for the bones,” says I. For I was not well plased at the way she shpoke to me, and me patience was gettin’ exhausted wid ’em.

“’Tis thryin’ to kill me darlin’ child you are,” she says. “Can’t you speak to me, Payther? Oh! what will I do wid him?”

“Give him some hard crust to chew,” says I, “perhaps that will sind it down.” But Payther would not take the crust, and threw himself on to the floor and kicked. “Shtand him on his head,” says I, “perhaps that will bring it up!” She tried to catch him by the legs to shtand him on his head, but Payther made a kick at her, and in thryin’ to save hersilf she caught me by the hair and shpoiled me new transformation that cost me five and six at the bargain sale. Then I made a grab at Payther, but he eluded me and disappeared coughin’ and shplutterin’ under the table.

“Come out of that, you little divil,” says I, for I was losin’ me timper.

“Don’t you dare to call me little darlin’ a divil,” says Matilda, bridlin’ up at me.

“I’ll call him a divil as often as I choose, and oftener if I like,” says I, for me timper was clane gone by this toime. Then seein’ Payther’s fut shtickin’ out from undher the table I made a grab at it. When she saw me grab, she gave me a push, and I shud have fallen if I had not caught howld of somethin’. So I caught Matilda. She caught the table cloth, but it came wid her, and down we wint, and everything on the table afther us. Whin I exthricated myself, I was a wreck, and me new eau-de-neil blouse was ruined. I looked for Matilda, and she was layin’ on the floor in a dead faint. I got a dipper of wather and threw it over her and she soon came to. When she did, the first thing she said was:—

“Payther! Where is my Payther?”

In my agitation I had clane forgotten Payther, but when I looked for him undher the table, he was scoopin’ up some jelly from the floor wid his hands and atin’ it.

“Where’s the fishbone?’’ says I.

“It’s gone,” says he, wid his mouth full of jelly.

“Which way did it got” says Matilda, “up or down!”

“I don’t know,” he says, “whether I coughed it up or choked it down. Anyway it’s gone. This jelly’s bosker. There’s no bones in it.”

Well, somehow this little incident caused a coolness between me and Matilda, especially whin Pat tried to take her part.

“You must be lanient wid her,” he said. “She’s from the counthry and it’s natural for her to be fond of her child.”

“And I think,” says I, “that it’s toime she wint back to the counthry, and I’ve a notion that she’s fond of more than her child.”

“What do you mane?” he says.

“I know phwat I mane,” says I. “Do you think it’s me she’s shtoppin’ here for?”

“I should think not,” says he, “and you as cool to her as you are.”

“Then it must be you,” says I.

“Get me me boots,” he says, “and don’t be a bally idiot.” But anyhow, I’m thankful to say they’re gone. The house is that quiet it don’t seem like the same place. I wished her goodbye when she shtarted for the counthry and I tould her that I wished she might live long and die happy there.

“And must you go? Dear me! How the toime flies. Don’t forget your wathermelon.”

“Come in,” says Mrs. McSweeney, “come in. Don’t be shtandin’ there wearin’ out the doormat, take the rockin’ chair and sit on it. And where did you shpend the King’s Birthday?”

“We wint to the National Park,” said Mrs. Moloney, as she arranged the cushions in the rocking chair, “and the mosquitoes nearly devoured us. I have to wear a veil wid red shpots to hide the marks of them. What wid the mosquitoes and the sun, and the sand-flies, we were all like—eh—what is that animal that has shpots all over it?”

“The leopard,’’ said Mrs. McSweeney. “If you had shpint your holiday in the same sinsible manner as we did you’d have no need to ask.”

“There are different opinions about sinsibility,” said Mrs. Moloney, “but where did you go?”

“Well,” replied Mrs. McSweeney, “as the mother of twins and the wife of the man that reckons he’s the father of ’em, I considher it my bounden duty to combine recreation wid education, so that their minds and their bodies may devilope side by side like the—”

“Meaning which?” said Mrs. Moloney, “the twins, or the man that reckons he’s the father of ’em?”

“Principally the twins,” said Mrs. McSweeney, “though the oldest of us ain’t so wise that we have not a lot to learn, if it’s only good manners.”

“Thrue for you,” said Mrs. Moloney. “Thrue for you.”

“Tis thrue for others beside me,” said Mrs. McSweeney, “and perhaps more so.”

“I think there’s thunder about,” said Mrs. Moloney.

“Maybe there is, and maybe there isn’t,” replied Mrs. McSweeney. “If there is, ’twill be time enough for us to attmd to it when we hear it. Where was I when you intherrupted me?”

“You was makin’ a vain attimpt to devilope something side by side wid something else,” said Mrs. Moloney, “and you got the twins and the father of the twins mixed up that way that I couldn’t tell the tother from which. But tell your own tale in your own way. ’Tis not for me to tell you how to tell your tale.”

“Well,” said Mrs. McSweeney, “Pat wanted to go to the races, but wishing as I said, to combine recreation wid amusement—no—I mane information wid education—no—that is not it. I mane that wishin’ to combine information wid recreation— that’s it—I persuaded him to take the twins and me to the Zoo. He was grumpy about it at first and said he didn’t get a holiday very often and why shouldn’t he enjoy himself when he did?

“What can you see at the Zoo,” he says, “that you can’t see any time goin’ up George Sthreet?”

“Tigers and lions,” says I.

“Who wants to see tigers and lions?” he says.

“’Twill be an education for the twins,” says I.

“Oh, well, have your own bally way,” he says, “as you always do. ”

And so we wint to the Zoo. I did not know at first what dress to wear, but I decided at last on me heliothrope hobbled skirt, cut low at the neck, and me new chanticlere hat. You didn’t see me new chanticlere hat? It has, or I mane it had, a fullsized bantam roosther on top, red poppies all round, a big tartan bow at the back, and forget-me-nots undherneath. Oh, it was a poem. The thram was crowded and the guard in a divil of a hurry. “Now then. Hurry on,” he says. But I couldn’t hurry on. When I made me hobble I didn’t reckon on the height of the thram shtep, and so it was a bit too tight for me to sthretch. However, wid the help of Providince and some assistance from Pat and the conducthor, I got safely on board. I could get no sate, but was thankful to have something to shtand on. Pat and the twins had to ride on the footboard. Pat was on one side and the twins on the other. They kept me heart in me mouth, for I felt sure that one or other or all of them would fall off every time the thram gev a jerk. I had to look both ways at oncet. Now I’d be tellin’ the twins to hould tight, and then I’d be tellin Pat to be careful. At last a man that was shtandin’ just behind me and houldin’ on by the sthrap, made me jump by shoutin’ in me ear:—

“Missus,” he says, “would it be askin’ too much if I was to ask you to take charge of that bally hat of yours and to keep it shtill? It is as big as a cartwheel and has teeth on it like a circular saw. Every time you twist your head, and that’s about ten times a second, it cuts pieces out of me. There’s several bits of my ear on the floor of the thram now.”

I was about to give him a sharp answer, but when I saw him wipin’ the blood off his ear I hadn’t the heart to talk to him as I would have liked to talk to him, so I gev him a look of silent contimpt instead. I was glad whin we got to the Zoo, for me limbs were gettin’ pins and needles in them through shtandin’ on one leg like a chicken roostin’.

“Buy some peanuts for ze monk.”

It was a little dark man with a basket that was shpakin’.

“Buy some peanuts for ze monk?”

“Get away wid you,” says I. “Monks don’t eat peanuts.”

“Oh, yes, Missy. Ze monks very fond of ze peanuts.”

“But,” says I, “there are no monks in here. This is the Zoo.”

“Oh, yes. Plenty monks. Long-haired monks, short-haired monks. Monks wis ze long tail, and monks wis ze short tail. Plenty monks. ’

So I bought some peanuts and we went to the enthrance. Pat paid for the lot of us and they tould us to go through a thing like an iron cage, and that twisted round and round. Pat got through all right and so did the twins, but when it came to my turrun I found that the thing was about two sizes too shmall for me. They twisted it backwards and forwards and me about half way in it, till I was a mask of bruises. Then the man did phwat he should have done at first, he tould them to take me in at the cart enthrance.

When I got inside I thought the twins were goin’ mad.

“Come here, Mum,” says Pat junior, pullin’ me round to the right. “Come and see the big brown bear.”

“No! Come this way,” says Mike. “Come and see Jumbo. He’s cracking nuts with his trunk.”

“Garn,” says Pat junior. “That’s the monkey.”

“Garn yerself,” says Mike. “Monkeys ain’t got trunks.”

Just then I sees Pat senior beckoning to us, and phwat should he be lookin’ at but a big brown bear on the top of a big pole in a place they called a pit. He used to climb the pole for the buns and cakes that the people would throw to him. Then he’d go down agin for all the world like a hod-carrier goin’ down a laddher. Then he’d sit up on the bottom and keep turnin’ round lookin’ for more buns. He’d been sittin’ up and turnin’ round so often that his tail was worn to a shtump. It was no more use to him as a fly-catcher than it would have been to dip honey out of a jar.

Next we wint to see some birds they call cranes. Why they call them cranes I don’t know. They have thin legs that seem too thin for them to shtand on, and to show off they shtand on one of them while they scratch their ear wid the other.

Then we saw some cassiwaries, and some emus, and some more bears and an osthrich that looked for all the world like a two-legged camel, hump and all.

Near the osthriches were some Highland cattle. “Come and look,” says Pat. “These are Scotch cattle.”

“You have no need to tell me that,” says I.”Look at that black bull wid the black hair all over his face. He’s the dead image of old McKinley that lives opposite to us. If I was in surf bathin’ and he poked up his head foreninst me I should say ‘Good mornin’, Mr. McKinley.’”

The only answer Pat gave to this was a shniff and a shnort. He can’t bear to hear me talk of surf bathin’.

We saw a lot of other animals from all over the world. There were some dear little antelopes. They were that graceful and frisky they reminded me of the time when I was a girl. There were some cattle from Foochow, and an animal wid a name I could not pronounce. It was spelt G. N. U. It had curly horns and two odd ends. His forequarthers seemed to belong to one animal and his hindquarthers to another. He had black whiskers on his face, a black mane on has neck, and a silver tail on his — other end. We saw some yaks from India, and gazelles from Arabia, where the sthreet arabs come from. We were passing a fince where there was another quiet-lookin’ baste. Pat was walkin’ foreninst me and not lookin’ at the animals, but was feastin’ his eyes on two girls who were walkin’ in front of him dhressed in the height of fashion and green open-work shtockin’s.

“Phwat’s the name of that one,” I says.

“Which one?” he says. “The one wid the pink hat or the one —”

“I mane the animal behind the fince,” I says. “Not them bould hussies that you have been eyein’ so closely.”

“Oh,” he says, turnin’ round to look at the card. “He is called—Holy Saint Dominick!”

“That’s a quare name for an animal,” says I.

“May the divil roast him, and you too,” says Pat, wipin’ his face on his coat sleeve. “He shpat fair in me eye.”

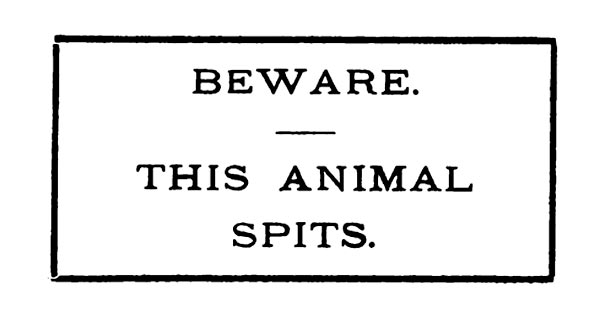

I looked at the card from a distance, and it said:

And I found it was called a vecuna.

“Sure,” says Pat, “I wish he was a man, I’d take a fall out of him for shpittin’ in me eye. ’Tis a thing I would not let me most intimate friend do.” And he wiped his face some more. “Why didn’t you warn me?” he says.

“You would have seen the card,” I says, “if you hadn’t been so busy watchin’ those bould hussies wid the green shtockin’s,” I says.

Just then he saw one of the twins laughin’ and he made a skelp at him, but the young ’un ducked undher his arrum and got away. For the next few minutes Pat was as grumpy as the ould camel that we saw in the next yard. He was the most miserable camel in the world if you could judge by his appearance. He was turnin’ grey, his lips were thremblin’ and his hump was all askew. We saw the Syrian goats. There were two of them. A blonde and a brunette. Their ears were so long that they had to hold up their heads to keep from walkin’on them.

Pat was some distance ahead when I heard him callin’ to me,

“Come here,” he says. “Come quick and see your Uncle, ould Tim Sheehy. ’Tis the dead spit of him.”

I wint to where he was pointin’, and there, in a glass cage, was the ugliest and the blackest lookin’ monkey I had ever seen. I couldn’t help laughin’ at him, for his face was the image of Uncle Tim’s before he got it shpoilt at the picnic.

There were more monkeys, big monkeys and little monkeys, white-nosed monkeys and pig-tailed monkeys, bonnet monkeys and baboons. We saw the man feedin’ the lions and the tigers, the wolves and the leopards. We wint to the aquarium and saw the Paradise fishes, Zebra fishes, Burmese eels, and bullrouts. We saw shnakes of all kinds. Diamond shnakes, black shnakes, whip shnakes and tiger shnakes. Afther we had seen the shnakes we saw the flamingoes, who were all legs and necks, and the sacred ibis that was all beak.

We saw the polar bears and the opossums, and the kangaroos, and there was one female kangaroo that had a dear little joey in her pouch. Then we wint to see the birds. Oh! the lovely birds they have. Parrots and parakeets of all sizes and colours. Red parrots and green parrots, black-tailed parrakeets and blue-fronted Amazons.

“Oh! Mum!” shouted Mike, “come and look at the eagle.”

I wint round the corner to where he was, and saw a solemn-lookin’ ould bird that looked more like an owl than what I thought an eagle would look like. He looked as if he was half asleep.

“Is that thing an eagle?” I says.

“Yes,” says Mike. “Look at the ticket.”

“Well,” says I, “he seems to be sleepy.”

“I’ll wake him,’’ says Pat junior, and he tuk off his cap and waved it at the eagle, who took no notice of him.

Mike then waved his cap and dhropped it inside the fince. He was goin’ to crawl undher afther it but I shtopped him.

“I’ll get it for you,” I says, “don’t you go in.” And I reached over the rail to get it for him, I had no sooner shtooped down than I felt a tug.

“Houly Moses,’’ says I, “phwat’s caught me?”

“There’s nothin’ caught you,” says Pat laughin’. “’Tis the eagle that has caught your bantam roosther. They’re cock-fightin’, and it’s tin to one on the eagle. Pull Biddy, or he’ll have it.”

“Oh! me beautiful chanticlere,” says I. “It’ll be ruined,”

Then I felt another big tug that I thought had cost me me new hair pads. “Shoo him off,” I says.

Pat shouted at the eagle, and waved his arrums to thry to make him lose his hoult, but it was no use. The eagle wouldn’t give way, me hat pins wouldn’t give way, and me hair pads were thrue to me, so the roosther had to give way, and when I lifted me head the eagle was houldin’ me roosther in his claw, and pickin’ the shtuffin’ out of him wid his beak, so he was.

I shtraightened me hat the best way I could, but it was like Kitty Booney when she arrived in America, it had lost its characther.

When I’d sthraightened me hat I insisted on goin’ home, and we shtarted to walk towards the gate, but in goin’ to the gate we had to pass the place where the elephant was.

“Oh! Mum,” shouted the twins, both at oncet, “here’s the elephant. Come and have a ride.’’

There he was, for all the wurruld like you’d see him in a picture book. He had his thrunk at one end and his tail at the other, and he was waggin’ them both. There was a man dhrivin’ him wid a shtraw hat and a sandy moustache.

“Do you think he would carry me?” I says to the man.

“I think he would,” says the man, “but we give no guarantee. You see he’s only an elephant. But if you like to chance it we will thry.”

At that moment I caught the elephant’s eye, and if ever an eye shpoke, Mrs. Moloney, it was the eye of that elephant at that moment.

“No,” says I, “I will not chance it. The twins may ride if they like, but I have too much respect for my dignity to ride a thing like that.”

“All right, Mum,” said the twins, both at oncet.

“You must sit shtill and not move,” I says to them.

“All right, Mum,’’ says they.

They climbed up a sort of a platform on to the elephant’s back, the man got asthride of his neck, and off they shtarted. They were sittin’ one on each side of the elephant, and I was just thinkin’ how I’d like to get their photos taken, when Pat junior made a grab at an apple that Mike was atin’, and they shtarted fightin’ for it.

“Shtop your tomfoolery,” I shouted, “or you’ll be failin’ off.”

Sure enough the wurruds were not out of me mouth when Mike shlipped and would have fallen if Pat had not grabbed him by the hair.

They both commenced howlin’ at oncet and I thought that every moment they’d be undhar the fate of the elephant, and he joggin’ along and grinnin’ as if he enjoyed it. They were comin’ back towards me, and throwin’ discretion to the winds, as the sayin’ is, I ran in front of the elephant and waved me umbrelly frantically round me head.

“Shtop, you murdherin’ divil,” I shouted. “Do you want to make orphans of me two twins?”

But he never shtopped. Before I knew another thing, he had his thrunk round me waist. He upended me over his head and sat me sthraddle ways on his neck in front of the dhriver. Poor man, he was as frightened as I was, besides bein’ half shmothered. Well, you know, Mrs. Moloney, hobble shkirts were never intinded for that kind of treatmeat. Me heliothrope, that cost three and eleven pence three farthings a yard at the bargain sale, was a ruin, I went out in a hobble shkirt, but I came home in a directwore, and the wind blowin that way that pins wouldn’t hould it.

But, barrin’ one or two little things that happened and were not on the programme, we had a grand day at the Zoo.

“Well, if you must go, you must. I suppose I’ll see you to-morrow. Mind the rint in the carpet.”

“Have you seen the pictures?” said Mrs. McSweeney, as she settled herself on Mrs. Moloney’s balcony for a comfortable chat.

“The pictures in what?” said Mrs. Moloney, as she noted that Mrs. McSweeney had a new pair of open-worked stockings.

“I mane the livin’ pictures,” said Mrs. McSweeney, “at the theayter.”

“I have not been to the theayter for ages,” said Mrs. Moloney. ‘‘By the time Moloney gets home and has a wash, and gets his tay, ’tis too late for theayters, and him wantin’ to get to bed early, havin’ to be up before daylight.”

“That’s the best of havin’ a man that can come home early now and then if he wants to,” said Mrs. McSweeney. “Pat can always get home at six, if he wants to, and it gives us time to take part in a little social enjymint now and agin.”

“I don’t care much for social enjymint,” said Mrs. Moloney. “So long as Moloney has regular work and keeps off the dhrink, I can find enough to do at home widhout gaddin’ about. ”

“Well,” said Mrs. McSweeney, shrugging her shoulders, “the donkey that always lives on thistles never knows the want of oats. Social enjymint is necessary to those that’s accustomed to it.”

“But what about the pictures?” said Mrs. Moloney.

“I was just comin’ to that when you intherrupted me,” said Mrs. McSweeney. “As Pat can get home at six o’clock when he likes, bein’ in a position of responsibility, he came home early one night last week and I had sausages for his tay. Sausages is his weak point, and always puts him in a good humour. So, when he had finished his tay and had a shmoke, he began playin’ wid the twins. At last one of ’em said, “When are you goin’ to take us to the pictures, Dad?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” he says, “suppose we go tonight?”

“Hurray!” says the twins, both at oncet.

“There’ll just be time,” says Pat. “Put on your things, Biddy, and we’ll all go to the pictures.”

Afther I’d got Pat out a clean shirt and collar, and washed the twins and combed their hair, I put on me new dhress of black shiffon glassy and embossed fillet lace, and me green velvet toke wid the red feather, and off we shtarted to the pictures.

We got there in good toime and got a good place in the front sates and waited for the performance to commence.

By-and-bye the musicians came in wid their insthruments and they tuk their sates and waited.

‘‘Phwat are they waitin’ for?” I says to Pat. “Why don’t they shtart?”

“They’re waitin,’” he says, “for the conducthor.”

“And why didn’t he come in wid the others?” I says.

“Becase he likes his little bit of fat,” says Pat. “If he came in wid the others people might take him for a musician.”

Just as he was shpeakin’ in walked the conductor, and as soon as he tuk his sate he gave a little tap wid his shtick and off the music shtarted. When they played the “Minsthrel Boy” me heart was in me mouth, but when they played the “Wind that shuk the Barley” it was in me feet I had to hould on to the sate to keep mesilf from gettin’ up and dancin’. And even then me feet wouldn’t keep shtill.

At last they lowered the lights and they showed the first picture.

“Hats off!” shouted somebody behind.

I looked round and divil a one could I see wid a hat on, so I went on lookin’ at the pictures.

“Hats off!” shouted somebody agin.

Just then somebody prodded me in the back wid somethin’, and I jumped and gave a shqueal, it shtartled me so?

“Phwat’s the matter?” says Pat.

“Somebody poked me in the ribs,” I says.

Then he shtud up and looked round. “Who was it poked me wife in the ribs?” he says, “Tell me that,” he says.

“’Twas I that touched her,” says a young female wid a pink dhress thrimmed wid gold passyminthery and a green parasol.

“And phwat did you for?” says Pat, as he looked at her in a mildher tone of voice.

“Will you kindly ask her to take off her hat?” she says wid a simile. “It hides all the pictures.”

“Take your hat off, Biddy,” he says, “the young lady can’t see the pictures.” And he shmiled back at her.

“I’ll take it off when I choose,” I says, not likin’ the way he looked at her.

“Don’t bother her,” says a young felly two sates back. “Perhaps if she does she’ll have to take her hair off wid it.”

“Some of your hair would come off mighty quick,” says I, “if I could get at you.”

“Shut up!” says Pat. “You’re makin’ an exhibition of yoursilf.”

“Am I?” I says, “where?”

“Here,” he says.

“’Tis aisy to be seen,” I says, “that I can be insulted wid immunity by a set of blackguards and that I have nobody to take me part.”

“If you won’t take that bally hat off, keep it shtill,” says an old man three sates back. “I’m breakin’ me neck thryin’ to dodge it.”

“I suppose I’d betther take it off?” I says to Pat in a whisper, “although I can’t see that it interferes wid anybody.”

“Yes,” he says, “take the bally thing off for the sake of peace and quietness. I can’t fight them all and look at the pictures at the same time.”

So I tuk it off and held it on me knee, and there was a great sigh of satisfaction behind me. And then I was able to fix me moind on the pictures. At least they said they was pictures, but I had a doubt about it. They were min and women movin’ about, and their eyes were movin’, and their lips were movin’, and I have an idea that it was real min and women pretendin’ to be pictures.

There was one place where there was a lovely counthry lane and a man hidin’ behind a tree wid a gun in his hand, and if ever there was a murdherous lookin’ villain he was one. The way he rolled his eyes was enough to turrun your blood into wather.

Presently, along came a fine lookin’ young felly carryin’ a bag full of money. As he came to the tree, the man behind it lifted his gun and tuk aim at him. The young man came along, gettin’ closer and closer, and the man wid the gun took aim agin. I cud shtand it no longer.

“Look out!” I shcreamed, “dodge him! Dodge him! He’s goin’ to shoot!”

But I was too late. Bang! went the gun, and when I opened my eyes agin, there was the young man, weltherin’ in his—phwat is it they welther in?”

“Gore,” said Mrs. Moloney.

“Yes,” said Mrs. McSweeney, “that’s it. The young man was weltherin’ in his gore.”

“Police!” I shouted. “The vagebone. He’s killed a man, and now he is robbin’ him.”

But the police tuk no notice, Pat tould me to shut up, and said somethin’ about “Blatherin’ idiot,” but I didn’t cateh phwat it was, and the people laughed. But I was so upset that I never knew phwat became of the robber, but Pat said it ended all right and he got his deserts, which was a blessin.

By-and-bye the lights wint up and Pat said there would be an intherval of tin minutes, and he said he just remimbered that he had to go out and see a man about a football match and to sit shtill and he’d be back in a minute.

I laid me hat on his sate to mind it and looked round at the people. The young lady in the pink dhress shmiled at me and said it was very warrm.

Not to be outdone in politeness, I tould her that it was.

“’Tis a nice show, ma’am,” she says.

“It is then,” says I.

“Are the little boys enjyin’ themselves?” she says, lookin’ at them and shmilin’.

“You bet,” says Pat.

“Bosker,” says Mike.

“Would you like some chocolates?” she says.

“Rather,” says both of ’em at once.

She gave them some chocolates and I made them say “Thank you,” and we got talkin’ to one another. She tould me that her young man, who had gone out to see a man about something, brought her to see the pictures about three times a week. She said her mother was a widow and her father was a clergyman, and she was shtudyin’ typewritin’ to help her poor old mother who was not too well off, and her sweetheart not bein’ able to marry her yet, as he was in a bank and not allowed to get married until promoted.

“Your collar is crooked,” she said, shimlin’ at me.

“Thank you, my dear,” says I, “would you mind straightenin’ it?”

She sthraightened me collar, and while she was doin’ it, the lights went down and the pictures came up. The first picture was a funny one and the twins were laughin’ at it fit to break a blood vessel when Pat came back,

“You had some throuble to find the man!” I says to him as he went to sit down.

“I did,” he says. “He was a—Houly Murdher!”

‘‘Phwat is it?” says I.

But he shtarted to dance and all the time thryin’ to keep back the bad language he was burstin’ to use. The people shouted ‘‘Silence!’’ and “Sit down!”

“There’s not a man here’ll make me sit down,” says Pat, dancin’ as well as he cud between the sates.

As he jumped I saw that me green velvet hat was hangin’ to him

“Pat,” says I, “you’ll ruin me hat.”

“To the divil wid your bally hat,” he says. “’Tis not the hat I’m moindin’, it’s the bally pins.”

“Which pin is it?” says I.

“All of ’em,” he says.

Well, I felt for the pins and I pulled ’em out one at the time, and the people were shtill singin’ out for him to sit down, and so he thried to sit down agin but he jumped up wid a yell.

“I can’t do it,” he says, “I can’t do it. I’ll never be able to sit agin. ”

“Well, then, we’d betther go home,” I says.

“Yes,” said a man behind, “take him home like a good woman.”

Pat wanted to fight the man that said it, but it was too dark for him to see which man it was that said it, which perhaps was quite as well.

Me hat was a wreck. I sthraightened it as well as I could, but it would turrun down in some places and cock up in others that way that I was ashamed of it.

Comin’ home in the thram there was a ladylike woman sittin’ in the sate opposite to me, and she made me quite uncomfortable the way she kept lookin’ at me. At last she spoke.

“I hope you will not think me rude,” she said, wid a shmile, “but I was surprised at your hat.”

“Was you,” I says. “And phwat were you surprised at?” For I couldn’t tell her everything, and Pat shtandin’ on the footboard of the thram close by, rubbin’ himself.

“Well,” she says, “I am a milliner, and it was only to-day the mail came in and brought the very latest Paris fashions, and now to-night I see you have one on. ’Tis the very latest, and I didn’t think there was one in Sydney yet.”

And sure enough if you go round the block now, you’ll see scores of them turruned down and cocked up just the same as mine. The next time I want to get a hat of the latest fashion, I’m goin’ to get Pat to take me to a picture show.

Well, we got home all right. I called and got a fine lobsther and a bottle of shtout and by the time we had finished that Pat was in a purty good humour agin, the only dhrawback bein’ that Pat had to take his off the mantelpiece.

But you’d never believe it, Mrs. Moloney, the sin and wickedness there is in this wurruld. When I wint to take off me things I found that me pendant wid the ruby and the diamonds that Pat bought me when he won the sweep was gone. I was that upset that the lobsther and stout was wasted on me. I couldn’t tell Pat, on top of his other throubles, so I went to bed and laid awake all night thinkin’ of it.

I have been lookin’ ever since for the clergyman’s daughter, but I’m afraid I’ll never see her or my pendant agin.

“Well, I must be goin’ or Pat will be home before me and lookin’ for the vaseline I promised to take him home.”

“Sure ’tis a beautiful day, so it is,” said Mrs. McSweeney, in answer to Mrs. Moloney’s salutation. “Dhraw your chair to the windy. I’m enjyin’ the shmell of the geraniums. ’Tis quite refreshin’ afther washin Pat’s socks. Where did you go yesterday? Nowhere? I wint to the review, no less. McSweeney had a holiday, and when I tuk him up a cup of tay in the mornin’, he says to me, “Biddy,” he says, “did you ever see a King’s Birthday?”

“Phwat a question,” says I.

“How?” says he.

“As if anybody cud see a birthday,” says I.

“Bad scran to you,” he says, “’tis mighty smart ye are this mornin’.’’ Then says he, “You know what I mane. I mane the levy, wid the soldiers, and the voluntayrs and things they hould in the park,” he says.

“You mane the review,” says I.

“Well, did ye ever see a review?” he says.

“I can’t exactly say that I did,” says I, “but me aunt on me mother’s side that married O’Toole of Ballyragin’’—

“Oh! Hould your blather,” he says, for he can never bear to hear me talk of me ancesthry. “Will you come to the review to-day?” he says.

“I don’t know phwat I cud wear,” says I.

“Wear anything,” he says. “Sure, Biddy, haven’t I often tould ye that ye have the kind of beauty that looks best when it’s unadorned? What did the poet say about it, Biddy? You used to be good at poethry.”

“Which poet?” says I.

“Divil a know I know,” says he, scratchm’ his head. “But put on anything you like and we’ll go and see the review,

Wid the bands a playin’

And the thrumpets brayin’,

And the horses boundin’

And the bugles soundin’;

Wid the swords a flashin’

And the sabres clashing

Wid the dhrums a beatin’

And the throops rethreatin’,

Wid the flags a flyin’

And the—”

“Oh! shut up,” says I. “Ye’re devilopin’ a habit of poethry that’ll grow on ye,” says I.

“’Tis not a habit,” he says, “’tis a natural accomplishment that was born wid me. There’s toimes when I can’t help it. It oozes from me like wather from a leaky shoe.”

Anyhow, I put on me tartan blouse with the red yoke and a pink skirt wid the green braid trimmin and we wint to the review.

“Phwat hat did ye wear?” asked Mrs. Moloney.

“I wore my Merry Widow hat, wid the forget-me-nots,” said Mrs. McSweeney, “and we shtarted early to avoid the crush, as the sayin’ is. There was no seats to be had on the thram, but I managed to squeeze in while Pat shtood on the footboard. I was no sooner in the thram than it shtarted that quick that I lost me balance, and then I sat down in the lap of a thin gintleman in a grey felt hat wid a flop. The concussion was great, and it was some toime before I cud exthrieate meself und sthruggle to me feet, for when I tried to rise I found that the thin gintleman’s glasses were caught in me forget-me-nots, while me umbrelly was hooked into the weskit of a stout man that sat foreninst me. When he had unhooked me, the stout gintleman gave me a pull in front and the thin gintleman a shove behind and I got to me feet wid Pat glarin’ at me from the footboard.

“I ask your pardon,” says I to the thin man, when I had gained me feet.

“Don’t mintion it,” he says, when he had got his breath and shtopped coughin’.

“Did I hurt you?” says I.

“I don’t think there’s anything bruk,” he said. “I’ll be able to tell bether when the thram shtops and I’m able to sthraighten myself.”

Just then the thram shtopped wid a jerk and it threw me towards the stout gintleman, but he saved me by shtickin’ out his two arrums and shovin’ me back agin.

“I ask your pardon,” says I. “’Twas the jerk of the thram that did it.”

“’Tis all right,” he says, “I’m used to it. I wurruk in a wool-sthore. I’m handlin’ bales of wool all the week.”

When we got to the Park it was beautiful to see the crowds of min, wimmin, and soldiers, all pushin’ and scrougin’ in different directions.

“Come on,” says Pat, “and we’ll get a good place to see the Governor.”

“Come there, shtand back,” said a felly in cordheroy pants and leggin’s that Pat said was a throoper. “Shtand back.”

He gave Pat a shove and he shtepped back right on to me favourite corn. I sang out and shoved him off it. The throoper pushed him back, so I shoved him agin. When the throoper saw him comin’ at him the second toime he caught Pat by the collar.

“Defyin’ the law, are you,” he said, as he shuk him, “come along wid me to the police station. I’ll soon show you.”

He was just goin’ to march Pat off, and Pat lookin’ that wild that I thought he’d hit the policeman, when I says, “’Twas my fault,” I says, “’Twas me that pushed him.”

“Then,” says he, “I’ll have to arrest you.” And he let go of Pat.

“Arrist me, is it?” says I, “faith! if you do you’ll get your hands full. I’ll not go a foot,” says I, “unless you carry me.”

He looked at me for a minute, and then he laughed. “I’ll not take the job on,” he says. “Keep back out of the crowd,” he says, “and when the review’s over I’ll fetch a throlly for you.”

He passed on, shovin’ the crowd back as he wint, and we were able to look about us. Pat was a bit grumpy at first, but at last a bugle sounded and he couldn’t be grumpy any more.

“Do you see the soldiers?” he says.

And sure enough I did. There they shtud, in a long row, wid their guns and swords and things.

Some was dhressed in rid coats, some in grey, some in brown, and some in blue. It was as good as a scene in a pantomime.

“Which is the Governor?” says I.

“Him on the chistnut horse,” says Pat.

“Bless him,” says I, “how nice he looks. And phwat a beautiful chist proticther he has.”

“Sure,” says Pat, “that is not a chist proticther. ”

“Then phwat’s it for?” says I.

“To keep his chist from gettin’ hurt wid the bullets and the cannon balls and things,” says he.

“And phwat’s that but a chist proticther?” says I.

“Oh! shut up,” he says, “and don’t be passin’ remarks about the Governor.”

“That’s not the Governor,” said a man in a tall hat wid a red moustache, “that’s only his hay-de-kong.”

“Which is the Governor, then?” says I.

“The one wid the cocked hat and feathers and gould sthripes on his breast,” he says. “Look now,” he says, “they’re goin’ to march past.’’

And sure enough they all came marchin’, some in rid coats, some in blue, and some in kharkee, some on foot and some on horseback. There was some they called the light horses, and some the heavy horses. There was the naval brigade, wid their white caps, and the artilleree wid their guns, and the lancers wid their lances, and the bands were playin’ and sthreamers flyin’, and the man in the tall hat tould us the names of them as they wint past.

There was one band that was not playin’ at all until it got right forninst us, and just as they were passin’ the dhrummer gave his dhrum three bangs and they shtruck up a tune that brought the tears into me eyes and me heart into me mouth. ’Twas “Garryowen,” no less.

“’Tis the Irish Brigade,” said the man wid the tall hat, makin’ room for me to look.

And sure enough, there they came, wid their heads in the air, as bould as brass and twice as shiney, lookin’ as saucy as they did whin they followed the Duke of Willington into the Battle of Thrafalga, and tuk the consait out of Napoleon Boniparty.

“Hurray!” says I, as I waved me umbrelly round me head, to the imminent danger of the crowd, ‘‘Hurray! Who says that Austhralia is not safe from the proud invadher,” I says, “when she has an Irish Brigade to protict her?”

“Oh! shut up,” said a man behind me that was shmokin’ a cigarette wid a red necktie, “you’re not in Ireland now.”

“No” says I, “and you were never there.”

“How do you know?” says he.

“Bekase Saint Pathrick banished the likes of you,” says I.

“Are ye callin’ me a riptile?” says he.

“’Tis good enough for you,” says I.

“’Struth!’’ says he, “ if you was a man I’d stouch yer.”

“Phwat’s that?” says Pat, sthrugglin’ to get at him through the crowd. “Stouch me missis is it? Here, who’ll hould me coat?”

I began to schrame, and in thryin’ to keep Pat back me umbrelly poked the gintleman in the eye wid the tall hat.

“For the love of Heaven keep him back,” says I, “or there’ll be murdher done.”

“Don’t keep him back,” said the man wid the red necktie, “let him come on, it will be a lesson to him.”

Just then a man came ridin’ by that would have had a foine chist if his head had been turned the other way round, and he shouted something that sounded like “Her-r-r-hoop,’’ and all the soldiers that were facin’ us on the other side of the Park pointed their guns at us simultaneously.

“Herrrrr-r-r-hoop!”

He had no sooner said it agin than all the soldiers fired their guns at once. Sueh a rattle I never heard, and I thought me toime had come. Then I turned to run away.

“Let me out!” I said to the crowd. “I’ll not shtay here to be shot in could blood,” says I, “and to lave me two motherless twins mournin’ for me.”

“Shtop, Biddy,” says Pat. “Don’t be a blatherin’ idiot.” But I kept thryin’ to make a hole in the crowd. “Biddy!” he says, “they’re not loaded.”

But I wouldn’t chance it. The crowd parted for me and I ran till I got the other side of the hill, and I sank on the grass wid me head in a shwim and me hat a ruin.

Pat was just tellin’ me that I ought to have more sinse when I thought that me latther end was before me. There was a puff of shmoke just over me head , and I no sooner saw it than I thought me, head was off.

“BANG!” Oh! I thought I’d never get the sound of me ears agin.

BANG! “Pat,” says I, “let me out of this.”

BANG.

“Biddy,” says he, “don’t be a flamin—”

BANG.

“Shtop kickin’,” says he, “and hould up your head. It’s only—”

BANG.

“It only the cannons—”

BANG.

I heard no more for the next half hour, although Pat said it was only about two minutes, but BANG! BANG! BANG! All I remimber is a confused conglomeration of crowds, trees, thrams, and Pat puttin’ vinigar and brown paper on me head and swearin’ at me inwardly.

“Where am I?” says I, faintly.

“You’re at home, glory be to the Powers,” says Pat.

“And where’s your coat?” I says.

“Haven’t I it on?” he says. “May the divil fly away wid you, Biddy,” he says. “I must have left it in the crowd, and I’m so used to have it off that I never missed it till this minute, through lookin’ afther you, and bringin’ you home in a cab,” he says.

“Pat,” says I, “I’ll never go to another review,” says I, “as long as I live.”

“I know you won’t,” he says.

Then he pulled his boots off, and as he banged them on the floor it made me shcream, for I thought his boots were guns. Me nerves are shathered, Mrs. Moloney. When the alarram clock wint off this mornin’ I shcreamed and fell out of bed wid the fright, and when I was gettin’ Pat his breakfast I dhropped the tay-pot when a bit of coal fell into the fendy.

Each toime there has been a knock at the door or a ring at the bell to-day I’ve bruk something, and if I keep like this much longer there’ll not be a whole thing in the house.

“Did you say you must be goin’? Well, the best of frinds must part. Shut the door aisy. If you bang it, I’d jump that way that it would be a toss up whether I should ever come down agin.

“Good-bye. Call in agin soon.”

“’Tis a question,” said Mrs. McSweeney, an she helped Mrs. Moloney to her fifth scone, “’tis a question whether we will ever be able to give half as much to Nature as Nature has given to us.”

“’Tis a question,” replied Mrs. Moloney, “whether Nature hasn’t given too much to some of us.” And she smiled sweetly at Mrs. McSweeney.

“Of course,” retorted Mrs. McSweeney, “you can shpake for yourself. You have a lot to be thankful for. See the appetite Nature has given you.”

“’Tis a healthy one,” said Mrs. Moloney, “and none of me other frinds remind me of it. But if Nature gave me a good appetite, which is a conshtant expinse and only an occasional pleasure, she gave me me bunions, which are always on me mind.”

“Most people have them on their feet,” said Mrs. McSweeney. “But whin I shpoke of Nature I was alloodin’ to Nature in her biggest sinse. To her bounchous gifts that are spread all over the Universe, and in other places too numerous to mintion, like plums in a Christmas cake, or flies on a threacle cask. To the rain—”

“That came through the tiles and shpoiled me best quilt,” said Mrs. Moloney.

“To the sunshine, the mountains and the flood,” said Mrs. McSweeney.

“To the insects, and the riptiles, and the mud,” echoed Mrs. Moloney.

“Some people,’ continued Mrs. McSweeney, “always look on the darkest side of everything. If they were thransported to the sun they would wandher round it lookin’ for a dark side. I suppose they can’t help it. It is the way, they’re built.”

“I suppose,” said Mrs. Moloney, “’twas Nature that built ’em.”

“’Tis well that Nature gave me a sweet timper,” said Mrs. McSweeney, “or ’tis annoyed I’d be at your interruptions. As it is I must be charitable and pity your want of depreciation. Sure, ’tis a funny place the wurruld would be if we were all made alike. ’Twas not an argumint I intinded to provoke. I was alloodin’ to the beauties of Nature as seen in our own botanic gardens. Last Choosday week was the birthday of me twins, and as I always give them a threat on their birthday, I tuk them to the gardens. The one great advantage about twins is that one birthday does the two of them. So I got them ready in the mornin’ and we wint to the gardens. We wint in the thram as far as King Sthreet and walked up and through the domain.

When we got to the gardens we went to see the ducks in the ponds. There were wild ducks, and anchovy ducks, and ducks that were not ducks but drakes. The twins fed them wid biscuits and bits of bread. ’Twas a beautiful day and the gardens looked lovely. They were as green as the hills of Wicklow. I never go to the gardens but I think of the green fields of Ballyragin, I get young again, and this time I was that jubilant that I offered to run Mick for a penny, and I should have beaten him if it hadn’t been for me shkirts gettin’ in the road.

We had lunch phwat they call all frisco, which means “undher a tree.” ’Tis undher the trees that Nature gives you the healthy appetite. The way the twins got outside the scones and the sandwiches, the cakes and the tarts, the peaches and the bananas was a treat to see, and beyant description. I could see them swellin’ that way that I had to eat the last couple of tarts mesilf to keep them’ from burstin’.

As it was they had pains that way that I had to rowl them six times down a hill to disthribute the loads they had undher their pinafores.

Afther we’d rested and got over the effects of our lunch we tuk a walk to look at the flowers. Och! the beautiful flowers.

The roses and lillies and sweet daffodillies,

That down in the gardens grow;

The pretty primroses they make into posies.

And cowslips all in a row,

Wid the green of the grass, and the beds of flowers, the gardens look for all the wurruld like a patchwork quilt. There were beds of violets and beds of verbenas, beds of gladigoniums and beds of pelarolouses. On one side was a big patch of chrysanthuses and on the other a bunch of polianthimums, besides a lot that I didn’t know the names of.

When we came to any that I didn’t know the names of, the twins used to read them to me. ’Twas not that I couldn’t read them, but I should have had to use me glasses, and I never put them on in public. The way the twins used to handle the hard wurruds was delightful to a mother’s ear to see.

“This is a larkspur,” says Pat.

“And this is a high biscuits,” says Mike.

“Here’s a columbine,” says Pat.

“And here’s a cyclorama,” says Mike.

“Look at the princes feather,” says Pat.

“Oh! Mum, look at the carbunculus,” says Mike.

“This is a trifoleum,” says Pat.

“Get away wid you,” says I. “Is it your own mother you’d be afther desayvin’? Whoever named that flower knew nothin’ about it. A trifoleum indeed. Why, ’tis the dear little shamrock no less.”

I wint down on me knees to look at it, and sure enough there it was, as green and as modest as if it had been growin’ in its own green Isle where

“It grows in the brakes, in the bogs and the mireland,

The dear little, sweet little shamrock of Ireland.”

I wanted no more flowers, for me heart was back in the land of me girlhood.

“Come along,” says I, “we’ll go up to the wishin’ tree.”

“What’s the wishin’ tree?” says Pat.

“’Tis a tree,” says I, “that was planted by Captain Cook when he first laid out these gardens. He planted a big pine tree that he happened to have wid him, and he put a shpell on it.”

“What’s a spell, Mum?” says Mike.

“’Tis a kind of charram,” says I. “And he made it so that for the future anybody walkin’ round it backwards three times could wish a wish, and phwatever they wished they’d get.”

“Hurray!” says the twins both at oncet. “Come and wish a wish.”

There was nearly a fight when we got to the tree to see which of them should have the first wish, but I decided that Mike should go first as he was the youngest. He walked three times round the tree backwards, and then wished he was a man.

“Sure,” says I, “your wish’ll come thrue some day if you live long enough, but you’ll have to wait awhile.”

Then Pat shtarted to walk backwards, but he only got half way when he shtopped.

“Phwat did you shtop for?” I says.

“There’s a poleeshman comin’,” he says.

“Och!” says I, “take no notice. He’ll not say anything to you.” So he wint on until he had gone three times round.

“Phwat did you wish?” says I.

“I won’t tell you,” he says.

“And is that the way,” says I, “that you shpake to the mother that’s givin’ you a birthday? ’Tis ashamed of yourself you should be.”

Well,” he says, “if you want to know, I wished I was a girl.”

“Well, maybe you’ll get your wish,” I says, “if you wait long enough. It takes a long while to turn a boy into a gurrul.”

“I don’t feel any difference,” he says.

“Have patience,” I says. “You don’t know phwat may happen.”

“Well,” says he, shpakin’ sheepish like, “it’s your turn now.”

“Sure I was never good at walkin’ backwards,” I says, “except when I twisted me leg and had to walk backwards to go forwards. But we’re out to enjy ourselves and so I suppose I might as well thry. I’ll wish a wish meself.”

I shtarted to walk backwards, but I found it no aisy matther, bekase if you once look forward as you walk backward you lose your wish,

“Am I goin’ shtraight?” I says, when I was about half ways round.

“No,” says Pat, “you are goin’ round.”

“I mane am I goin’ shtraight round?” I says.

“Oh, near enough,” says he, “only you nearly walked on to the geranthemums. Keep to the right a bit.”

So I kept to the right a bit.

“A bit more,” he says.

So I turruned a bit more to the right.

“Now go sthraight ahead,” he said.

I wint shtraight for about a half, or it might be three-quarthers, of a yard. The little shpalpeen.

He knew phwat he was about, for I hadn’t tuk two shteps when I felt a concussion behind me. Then I fell over something, turruned a back somerset, and found mesilf sittin’ out of wind on the ashfelt footpath. Just in front of me, on the way I had come, sat a big poleesthman in white pants wid a red face. He was lookin’ at me as if he would swallow me. It seems he was stoopin’ down tyin’ his boot-lace when that young divil of a Pat backed me on to him.

“Tare an’ ouns,” he says, when he got some wind. “Is it salt and batthery or phwat?”

“No,” says I, “’tis a case of obsthructin’ the footpath.”

“I’ll obsthruct you,” he says, “when I get me wind. ’Tis threason to be upsettin’ a mimber of the foorce. I’ll run you in. By the ghost of me grandmother’s gridiron, I will.”

“Say that agin,” I says.

“I’ll see you” he says.

But I burrust out laughin’. I could hould it no longer.

“Phwat are you laughin’ at?” he says. “I’ll tache you—”

“Oh,” I says, “hould your whisht, You’ve taught me all you’re ever likely to tache me. Do you moind the last time we tuk the flure together? ’Twas at Dinny Doolan’s weddin’. The time Con Rooney lost his ear. ’Twas just before you sailed for Austhralia where you were goin’ to make a fortune in three months. ’Tis years ago. Ye were a shmart young felly then. You have doubled your weight at laste, but your brogue has the same flavour, and you have the same ould oath. I’d know you, Tim Donovan, if you were kippered.”

He picked up his helmet that was on the ground beside him, and then he looked at me. At last a light seemed to dawn on him.

“Troth!” he says, “am I wool gatherin’?”

“You look like it,” says I.

“It can’t be,” he says, “but it is. Sure, you’re not Biddy?”

“I am that same,” says I. “The gurrul you jilted, no less.”

He got on his feet and brushed his trousers, and then he turruned to the twins.

“Move on,” he says. “Gwanawayouterthat.”

“Lave them alone, Tim,” I says. “They are my twins.”

“Your phwat?”

“My twins. And now help me up. And how is Mrs. Donovan?” says I, as he sthruggled to raise me.

“She is,” he said, “the same as usual. She is not so plump as you, Biddy, and she doesn’t bear her age well.”

“He didn’t run me in. He’s comin’ to tay nixt Sunday, that bein’ his day off jooty. Talkin’ of tay, it’s nearly six o’clock, and me wid fish to cook. Good-bye. Pop in agin soon.”

“’Tis just in toime ye are,” said Mrs. McSweeney, as she placed an extra cup and saucer for Mrs. Moloney. “So sure as the clock sthrikes four a sinkin’ feelin’ comes over me, and ’tis then I foind a cup of tay is both refrishin’ and invigoratin’. And how is Moloney and the gurls?”

“The gurls are well, thank you,” replied Mrs. Moloney, as she removed her hat and gloves, “but Moloney’s a wreck. He lost three days last week and two this week wid the inflooenzy, and it has left him that cross that there’s no doin’ anything wid him, to say nothin’ of the pains in his limbs that keep me awake all night with his groanin’. I’m that worn out I cud shleep sthandin’.”

“Faith! ’tis well I know the sinsation,” said Mrs. McSweeney, as she removed Mrs. Moloney’s hat pins from the biscuit barrel and stuck them in the tea-cosy, “didn’t I have it meself last winther. And phwat wid the pains and the aches in me limbs, the looseness of me cough, and the tightness of me chest, me groanin’ and me wheezin me moanin’ and me shneezin’, Pat used to use bad language at me in his shleep. Not that I cud blame him for it, for phwat wid rubbin’ me wid liniment, handin’ me cough mixture, attindin’ to the twins, and tellin’ me the toime every quarther of an hour, the shleep he got wasn’t worth mintionin’ more especially as it was the busy saison and he wurrukin’ overtime. But I didn’t know so much about it then as I know now. ’Tis a curious thing, Mrs. Moloney, but I always notice that the more we learn the more we seem to know. Do you know phwat causes the inflooenzy, Mrs. Moloney? ’Tis microbes. Phwat? never heard of microbes! Well, well now. I thought everybody knew phwat microbes was. Microbes, Mrs. Moloney, are—well—they are just microbes. Neither more nor less. That’s the name they give them. Everything, now-a-days, is caused by ’em. Do you moind the wurruds of the poet?

“Phwat great evints from little causes shpring.”

When the poet said that, Mrs. Moloney, microbes was the little causes he was alludin’ to. I learned all about them at a lecture the either night. The lecture was in connection wid the fresh hair laague, and the tixt was “Microbes.” The gintleman that lectured showed us pictures of ’em; and they was the funniest things, Mrs. Maloney. Pat said it made him feel for all the wurruld as if he’d been takin’ too much bad whisky. There was microbes like shnakes, and microbes like goannas, long ones and short ones, thin ones and thick ones. Some were sthraight and some were crooked, some were all head and no tail, and some were all tail and no head. There were microbes like tadpoles, microbes like corkscrews, and microbes like pieces of maccarony.

The gintleman explained that they were different families of ’em, wid family resimblances in each, and the way they increase their families is quite beyond our powers of conciption, Mrs. Moloney. To think of a microbe becomin’ a great grandfather, wid millions of descendants, in twinty minutes, is enough to make you doubt the truth of the lecturer if he wasn’t a clergyman and it not bein’ to his advantage to tell a lie.

Everything we eat has microbes in it, everything we dhrink has microbes in it, and all diseases are caused by microbes. The air we breathe is full of ’em, and the wather we dhrink is thick wid ’em. I can’t purtind to remimber the names of ’em, but everything is caused by ’em. There are thousands of different sorts, and each sort is the cause of something. There is the microbe of Inflooenzy, and the microbe of Brown-quiet-us. The microbe of Love, and the microbe of Jealousy. The microbe of Fashion, and the microbe of Politics. Phwatever happens now, you may take it for granted that there’s microbes at wurruk. If you feel sad, it’s microbes. If you feel jolly, it’s microbes. If you feel betwixt and between, it’s microbes, only then they’re fightin’ each other.

The only consolation we have is that they are like min, and disagree wid each other. It may surprise you to know, Mrs. Moloney, that at the prisent moment ye have inside ye hundreds of millions of microbes that are fightin’ battles in your interior, and that your very loife, to say nothing of your future health and happiness, is depindin’ on the result. Even your moral character is in the balance and may be found wantin’. The microbes of Love and Hathred, of Virtue and Vice, of Honesty and Depravity, are at this moment contindin’ in mortal combat undherneath your shtay bodice, and it is quite uncertain which will win. But ’tis pale ye look. Perhaps a little shpirits? Phwat will ye take wid it? Nothing? Well, perhaps it will be best that way. I like it nate mesilf. And I have some cloves. Here’s to you. May the microbes of throuble never get into your organs to disthurb their harmony.

Now, as I was sayin’, everything is caused by microbes, and if they did not destroy one another the wurruld wud be full of ’em. The microbe of Love continds wid the microbe of Jealousy, and they fight each other till they desthroy each other and there’s nothin’ of either of ’em left. The microbe of Selfishness is fightin’ the microbe of Ginerosity, the microbe of Pride is preyin’ on the microbe of Humility, the microbe of Laziness on that of Industhry, that of Threachery on that of Loyalty, while the microbe of Tears is devourin’ the microbe of Mirth and Laughter. The microbe of Timidity subdues the microbe of Courage, and the microbe of old age is continually gettin’ the betther of that of youth.

There are microbes that have been discovered and indintified and some that have elluded indintification, and that go about their dirthy wurruk in secret. There are microbes that projooce themselves and some that can be inthrojooced by inockilation. If a man is a fool he can be inockilated wid the microbe of Common Sinse, and if a woman is a flirt and a breaker of hearts she ought to be inockilated wid the microbe of Blighted Affection. As some can only be inthrojooced by inockilation, so some can only be removed by an operation.

Do you mind the toime of Mrs. Dwyer’s last evenin’? I mane the evenin’ ye were not invited? Well, on that night I met Mrs. Murphy that keeps the little shop at the corner. She has a friend in a warehouse in the city, whose brother is married to a young woman who has a cousin who is a nurse in a hospital wid streamers and a blue cloak. She was tellin’ me that the time of the nurses is principally taken up wid attendin’ operations and fightin’ microbes. They fight ’em by the antideciptic system, and most of the operations is for appindixitis. ’Tis a new disease, and consequently all the best people has it.

Well, to come back to the day of Mrs. Dwyer’s evenin’. I met that night the most perfect gintleman I ever saw wid my two mortal eyes. He’s in the hair dhressin’ line, and keeps a shop where he sells tobacco and cigars wid lovely dark eyes and a waxed moustache. He comliminted me on me compliction, and we had two waltzes, some ice crame and green ginger. He handed me a glass of wine as he squeezed me hand wid a dash of sody in it, and he was just callin’ me his “affinity,” phwatever that is, when some evil janius inockilated Pat wid the microbe of Jealousy, and he insisted on me goin’ home at once if not sooner.