a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Thirty Years Among The Blacks of Australia

Author: William T Pyke

eBook No.: 2100161h.html

Language: English

Date first posted: 2021

Most recent update: 2021

This eBook was produced by: Maurie and Lyn Mulcahy

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

EVERYONE who has lived in Australia any length of time has heard of Buckley, "The Wild White Man," as he was familiarly called by the early settlers. Two separate accounts were published during the 1850's, purporting to give to the curious reader Buckley's savage life among the native black wanderers and hunters. Both these books have been out of print for over twenty years, during which period inquiries for them at the booksellers have been numerous and continuous, though, of course, unsatisfied.

The present chapters are an attempt to make use of the life of Buckley as a groundwork for imparting a readable, reliable, and fairly complete description of the manners and customs of the strange people with whom he lived for more than a generation. In compiling it many books and pamphlets have been consulted and, I think, every statement contained herein may be verified by reference to the best acknowledged authorities.

It is a strange fact, but nevertheless true, that no cheap work on the Australian Aboriginal black is procurable. Students and specialists are recommended to read Curr's Australian Race, 2 vols., £2 2s.; Brough Smyth's Aborigines of Australia, 2 vols., £3 3s.; Dawson's Australian Aborigines, 13s 6d.; Beveridge's Aborigines of Victoria and Riverina, 5s. In addition to these publications there are some pamphlets and reports in the Public Library, Melbourne, where also may be seen the journals, &c., of various Australian explorers, which contain incidentally information on the blacks.

WILLIAM T. PYKE. Melbourne.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

CHAPTER I.—SOLDIER AND CONVICT.

CHAPTER II.—THE PORT PHILLIP CONVICT SETTLEMENT OF 1803-4.

CHAPTER III.—THE RUNAWAY CONVICTS.

CHAPTER IV.—BUCKLEY'S CRUSOE LIFE.

CHAPTER V.—ADOPTED BY THE BLACKS.

CHAPTER VI.—FIGHTING AND HUNTING.

CHAPTER VII.—TRIBAL AMENITIES.

CHAPTER VIII.—DOMESTIC AND TRAGIC.

CHAPTER IX.—WITCHCRAFT & VENGEANCE.

CHAPTER X.—TERPSICHOREAN AND COMMERCIAL.

CHAPTER XI.—HOPES OF RESCUE.

CHAPTER XII.—RESTORED TO CIVILISATION.

CHAPTER XIII.—THE ABORIGINES AND THE WHITES.

ANECDOTE BY MR. GIDEON LANG.

BUCKLEY'S EARLY LIFE—TAKES THE KING'S SHILLING—FIGHTS THE KING'S ENEMIES—HIS DISGRACE—TRANSPORTED TO PORT PHILLIP.

ONE of the most curious and romantic incidents connected with the early history of the Colony of Victoria is the story of the life and adventures of William Buckley, a runaway convict, and his thirty-two years' wanderings with the blackfellows of Port Phillip.

I purpose in the present narrative to give a short account of William Buckley's life, and to interweave with it a description of the manners and customs of his black companions, together with a brief sketch of the history of the founding and settlement of the great Colony of Victoria.

Our hero, if we way presume to call the object of our tale a hero, was born near Macclesfield in the county of Cheshire, England in the year 1780, ten years after the discovery by Captain Cook of the great south land* of which poor Buckley was destined to become the sole though unwilling British colonist for more than a generation; perhaps not monarch of all he surveyed but at any rate with no other white man to dispute his right to the title if he had claimed such an exalted dignity.

[* The land first discovered on the Continent of Australia by Captain Cook's expedition was Cape Everard, within the boundary of the Colony of Victoria. Captain Cook named it Point Hicks, in honour of Lieutenant Hicks, of the Endeavour, who first sighted it on Thursday, April 19th, 1770.]

Buckley the elder, his father, tilled a small farm in the neighbourhood of Macclesfield and tried to raise his domestic crop of boys and girls as respectably as his very limited means would allow him. He was fairly successful with the others, but William seems to have been the tare among the wheat. The seeds of good advice falling in his case on stony ground did not take root, and therefore brought forth no fruit in the shape of improved conduct. So his father, like a good husbandman, plucked him out, and transplanted him from his own family circle into that of the boy's grandfather.

His grandfather took him in hand, and sent him to a small night-school, where he received the rudiments of reading and writing.

When the lad was about fifteen years of age, he was apprenticed to a brick-layer; but work did not agree with him: he seems to have been born tired, like the lazy man in the story. Disliking restraint, or continuous exertion, he often quarrelled with his master, who endeavoured to make him industrious and useful. These frequent attempts to shirk or scamp his work brought well-merited punishment upon his shoulders, which he submitted to with a very bad grace. For two or three years a continuous warfare waged between master and man.

At length the sullen and rebellious boy resolved to quit the employment of his taskmaster on the first opportunity which might present itself. And the opportunity came when he was about nineteen years of age.

In those troublous times when every nation of Europe was embroiled in Napoleon's wars, the recruiting-sergeant was to be found in every likely village in England, beating up yokels and other simpletons as food for powder, or candidates for glory. Attracted by the brilliant and gorgeous uniforms of the soldiery, and inspired by plenty of beer, the patriotism of the sergeant's victims was very easily aroused.

To William Buckley, lazy, stupid, and discontented with his condition, the sergeant's glowing descriptions of a soldier's life and the glorious pomp and circumstance of war opened to his mental vision a bright vista of future greatness, or perhaps swaggering independence and pot-house popularity. The King's shilling and the large bounty of ten guineas were gladly accepted by him, and he enlisted in the Cheshire Militia. After serving about a year in the Militia, he volunteered into the 4th or King's Own Regiment, receiving another bounty, for soldiers were badly wanted in those days.

In a few weeks his regiment was ordered to Holland, where the English and Russian forces were fighting the French and Dutch republicans. The privations and dangers of a disastrous campaign, rendered still more terrible by the severities of a Dutch winter, were passed through. Buckley's regiment suffered heavily, the elements assisting the enemy not a little in harassing its movements and reducing its numbers. A shot from a Frenchman's gun wounded Buckley in the right hand, and rendered him for some time unfit for duty.

When the war was over his regiment returned to England and was quartered in Chatham Barracks.

After having been in the army about four years, Buckley received a third bounty, this time for extended service. His officers were pleased with his attention to duty and general conduct, and perhaps were proud of him, for he was a fine-looking fellow, probably the biggest man in his regiment, being nearly six feet six inches in height and splendidly proportioned.

The dull monotony of barrack life at length had a demoralizing effect upon poor Buckley's character. An inactive existence tests every man's moral backbone, and Buckley's was not one of the strongest. He became associated with some of the worst men in the regiment, with a result that blasted his whole future career.

Returned from six weeks furlough, during which he had visited his relatives and old acquaintances in the country, he was arrested and tried for receiving stolen goods. The charge against him was proved, and the smart soldier who had helped to fight the King's enemies had now to serve His Majesty in a more menial capacity. His bright scarlet uniform was exchanged for one of a more sombre colour, decorated with broad arrows and other insignia of degradation and servitude; and the daily routine of barrack life for the arduous and not at all congenial task of trundling a heavy wheelbarrow full of stones and earth at the fortification of Woolwich.

Six months had slowly passed at this work, when he was drafted with the first batch of prisoners, selected by the Government, to found a new penal settlement in Australia, on the shores of Port Phillip.

This expedition, which had been several months in preparation, was originally destined for Port Jackson, or Botany Bay as it was then popularly called, the parent settlement in Australia; but political and commercial reasons had induced the Government to alter their decision, and fix upon Port Phillip as a more suitable place. Jealousy of England's historic enemy, France, and the fear of Napoleon founding a rival colony somewhere on the Australian coast, which had only recently been explored in detail by the great French navigator, Baudin, were good political reasons for starting another colony, 500 miles away from the old one.

An additional incentive to such a proceeding was also given by the report that valuable forests of timber suitable for shipbuilding purposes abounded on the southern coast. England was then projecting a very large increase to her navy, and her own forests of British oak had shown signs of not meeting the large demands made upon them during the long naval wars in which she had been engaged, and which were about to be renewed with increased vigour.

Commercially, it was thought the new settlement ought to prove very valuable as a station or emporium for the numerous vessels employed in the sealing industry, for at that time the neighbouring coasts abounded with thousands and thousands of that useful amphibian, an animal which had become very scarce and difficult to obtain in northern latitudes.

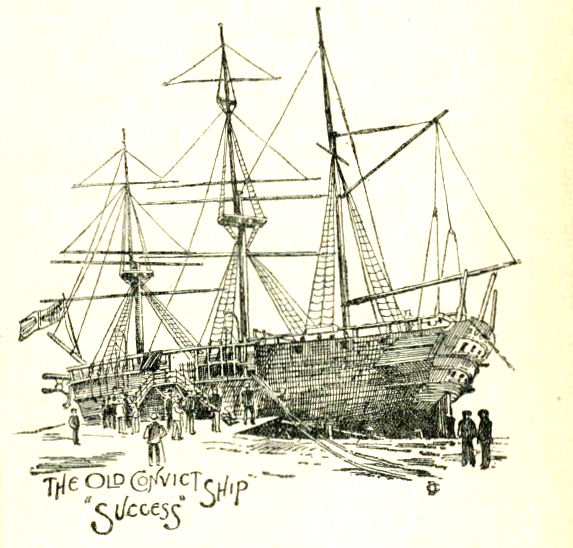

By the 26th day of April, 1803, the convicts, their keepers, and a few free settlers, were embarked, and the doleful expedition set sail out of Portsmouth Harbour. It consisted of two vessels, the Calcutta, a fifty gun frigate, under the command of Captain Daniel Woodriff, and a chartered East Indiaman named the Ocean.

To Lieutenant-Colonel David Collins of the Royal Marines, who had had some colonial experience as Judge-Advocate of the elder colony for the first ten years of its existence, was given the position of supreme command, under the title of Lieutenant-Governor, his superior officer being Governor King of the Port Jackson settlement.

The convicts numbered 307, all males; and there were 17 free women on board, prisoners' wives who had offered to share the hard lot of their worse halves. Seven children of the convicts also accompanied their exiled parents. It may be mentioned that one of these children was John Pascoe Fawkner, who afterwards became one of the founders of the City of Melbourne, and figured in political life for many years in the Colony of Victoria.

Besides officials, seamen, and soldiers, only twelve free people (eleven men and one women) were on board—a very little quota of goodness to leaven so huge a mass of human iniquity and misery.

The voyage out was not marked by any extraordinary events. On the whole the prisoners behaved very well, and were treated with consideration by their keepers. But any insubordination or breach of regulations was promptly punished by the free application of that most useful instrument, the cat-o'-nine-tails. In those days anything like tender-heartedness in the treatment of convicts would have been regarded as a direct incentive to mutiny. Two prisoners died, and the wife of another one also succumbed to the severities of ship life. The usual ports of call were touched at, the usual storms were weathered, and on October 10th, 1803, land was sighted by the look-out man of the Calcutta—King Island, in Bass Straits, being the first point descried within Australian waters.

A raging gale which came on shortly afterwards compelled them to stand off till next day. Then the entrance to Port Phillip was made, and the Calcutta glided through its narrow and shallow opening and dropped anchor just inside the Heads near where is now situated the popular holiday resort of Sorrento. The Ocean was already there, riding at anchor, having anticipated the arrival of her crime-laden consort by a few days.

STARTING A COLONY—TROUBLES WITH THE BLACKS—LIFE IN THE CONVICT CAMP—FREQUENT ESCAPES OF CONVICTS—BUCKLEY TAKES TO THE BUSH—ABANDONMENT OF THE SETTLEMENT.

BUT little time was lost in preparing for the disembarkation of the ships' companies. Soon the place was lively with the hum of busy people engaged in felling trees, constructing huts, making paths, landing provisions and stores, and all the other manifold duties attending the formation of a new settlement in the primeval wilds, where hitherto none but the stealthy and suspicious black, the timid kangaroo, or the feathered denizen of the woods had broken the deep solitude.

In three weeks everything had been got ashore, and the Ocean transport was discharged from His Majesty's Service and free to resume her voyage to China as soon as she was able to take in ballast.

The black inhabitants seemed to regard the invaders of their dominions with but very little apprehension, and showed not the slightest desire to contest the right or the power of the new-comers to settle amongst them. They manifested the childish curiosity common to all inferior peoples, and took with great avidity and delight the presents of biscuits, trinkets, blankets, etc., proffered to them by the white men. Generally, after receiving the gifts, they immediately departed into the seclusion of the bush, to more thoroughly enjoy them, or to make known their good fortune to their friends.

The first act of impropriety on their part was committed by one of their number who stole the wash-streak of a boat, and made off with it behind some neighbouring bushes. But the delinquent and his conniving companions were very soon brought to their bearings. All the presents which had just been given to them were forcibly taken back again, and they were made to understand by signs that they would not receive anything more until the stolen article was restored to its rightful owners—a very practical and humane way of teaching the poor ignorant creatures the difference in meum and tuum.

A few weeks later a serious affray with the natives took place, in which, it is to be regretted, some blood was shed. With it the conflict of the two races may be said to have had its beginning. It happened while Tuckey, First-Lieutenant of the Calcutta, and Mr. Harris, the Surveyor of the settlement, were exploring the shores of the bay in company with two boats' crews. They had landed on the western side of Port Phillip, near the entrance to what is now named Corio Bay. We will describe what occurred in Lieutenant Tuckey's own words, as recorded in his journal :—

'The N.W. side of the port, where a level plain extends to the

northwards as far as the horizon, appears to be by far the most

populous. At this place, upwards of two hundred natives assembled

around the surveying boats, and their obviously hostile intentions made

the application of firearms absolutely necessary to repel them, by

which one native was killed and two or three wounded.

'Previous to this time, several interviews had been held with

separate parties, at different places, during which the most friendly

intercourse was maintained, and endeavoured to be strengthened on our

part by presents of blankets, beads, &c. At these interviews they

appeared to have a perfect knowledge of firearms, and as they seemed

terrified even at the sight of them, they were kept entirely out of

view.

'The last interview which terminated so unexpectedly hostile, had at

its commencement the same friendly appearance. Three natives, unarmed,

came to the boats, and received fish, bread, and blankets. Feeling no

apprehension from three naked and unarmed savages, the First-Lieutenant

proceeded with one boat to continue the survey, while the other boat's

crew remained on shore to dress dinner and procure water.

'The moment the first boat disappeared, the three natives took leave,

and in less than an hour returned with forty more, headed by a chief,*

who seemed to possess much authority. This party immediately divided,

some taking off the attention of the people who had charge of the boat

(in which was Mr. Harris the Surveyor of the colony), while the rest

surrounded the boat; the oars, masts, and sails of which were used in

erecting the tent.

'The intention to plunder was immediately visible, and all the

exertions of the boat's crew were insufficient to prevent them

possessing themselves of a tomahawk, an axe, and a saw. In this

situation, as it was impossible to get the boat away, everything

belonging to her being on shore, it was thought advisable to temporise

and await the return of the other boat, without having recourse to

firearms, if it could possibly be avoided; and, for this purpose,

bread, meat and blankets were given them. These condescensions however,

seemed only to increase their boldness, and their numbers, having been

augmented by the junction of two other parties, amounted to more than

two hundred.

'At this critical time the other boat came in sight, and observing the

crowd and tumult at the tent, pushed towards them with all possible

despatch. Upon approaching the shore, the unusual warlike appearance of

the natives was immediately observed; and as they seemed to have entire

possession of the tent, serious apprehensions were entertained for Mr.

Harris and two of the boat's crew, who it was noticed were not at the

boat.

'At the moment that the grapnel was hove out of the Lieutenant's boat,

to prevent her taking ground, one of the natives seized the master's

mate, who had charge of the other boat, and held him fast in his arms.

'A general cry of "Fire sir; for God's sake, fire!" was now addressed

from those on shore to the First-Lieutenant. Hoping the report only

would sufficiently intimidate them, two muskets were fired over their

heads. For a moment they seemed to pause, and a few retreated behind

the trees, but immediately returned, clapping their hands, and shouting

vehemently. Four muskets with buckshot and the fowling-pieces of the

gentlemen with small shot, were now fired among them, and from the

general howl, very different from their former shouts, many were

supposed to be struck. This discharge created a general panic, and,

leaving their cloaks behind, they flew in every direction among the

trees.

'It was hoped the business would have terminated here, and orders were

therefore given to strike the tent, and prepare to quit the territory

of such disagreeable neighbours. While thus employed, a large party

were seen again assembling behind a hill, at the foot of which was our

tent. They advanced in a compact body to the brow of the hill, every

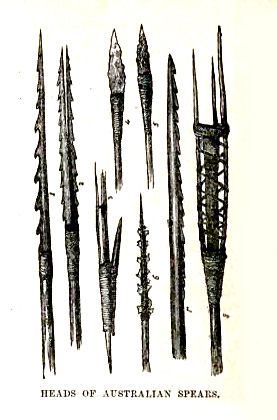

individual armed with a spear, and some carrying bundles of them.

'When within a hundred yards of us they halted, and the chief, with

one attendant, came down to the tent, and spoke with great vehemence,

holding a very large war spear in a position for throwing. The

First-Lieutenant, wishing to restore peace if possible, laid down his

gun, advanced to the chief and presented him with several cloaks,

necklaces, and spears, which had been left behind in their retreat.

The chief took his own cloak and necklace and gave the rest to his

attendant. His countenance and gestures all this time betrayed feelings

more of anger than of fear, and his spear every moment appeared on the

point of quitting his hand.

'When the cloaks were all given up, the main body on the hill began

to descend, shouting and flourishing their spears. Our people were

immediately drawn up, and ordered to present their muskets loaded with

ball, while a last attempt was made to convince the chief that, if his

people continued to approach, they would be immediately fired upon.

These threats were either not properly understood, or were despised,

and it was deemed absolutely necessary for our own safety to prove the

power of our firearms, before they came near enough to injure us with

their spears.

'Selecting one of the foremost, who appeared to be the most violent,

as a proper example, three muskets were fired at him, at fifty yards

distance, two of which took effect, and he fell dead on the spot. The

chief, turning round at the report, saw him fall, and immediately fled

among the trees; a general dispersion succeeded, and the dead body was

left behind.'

[*Lieutenant Tuckey is wrong. The Australian blacks had no chiefs, in the ordinary sense of the term. The husband was the chief of his own household; but the people, as a tribe, recognised no personal authority. Each man or family was under no restraint but that imposed by custom. As in all communities, civilised or savage, some men in every tribe were naturally looked up to by the others, on account of superior intelligence or physical strength. These might be taken for chiefs by white strangers.]

But the native blacks were not the only trouble which the authorities had to encounter and overcome. The convicts were not easily amenable to discipline, and their red-coated janitors, in many respects, were not much better. Drunkenness was extremely rife. The Lieutenant-Governor regarded its prevalence with indignation and dismay, and issued orders for its abatement or suppression, but with little effect. The soldiers constantly appearing on parade in most unsoldierly unsteadiness evoked his strong reprobation, and consequently after a time no one was allowed to take his allowance of spirits into the privacy of his tent, but was obliged to drink it while standing in the presence of his superior officer. Thus the thrifty teetotallers, if there were any teetotallers among them, were prevented from trading their allowance to their more thirsty or convivial comrades.

Rumour sayeth that the Governor himself was rather fond of the ruddy wine, and that he had an able confrére in his chaplain 'Old Bobby Knopwood,' as that reverend gentleman was familiarly called by the unrighteous or facetious. But as Shakespeare has it —'What in the officer is but a choleric word, is in the soldier rank blasphemy;' and in those days it was no uncommon thing for a 'gentleman' (God save the mark) to drink himself under the table. The old saying that example goes further than precept does not seem to have been thought of by those in authority in the little settlement.

However, it was not all beer and skittles with the convicts. They were aroused from their slumbers at sunrise, and immediately set to work at their several tasks, which they were kept at till seven in the evening, with about two hours and a half of intervals for rest and refreshment. But in extenuation of the hard labour, the discipline to which they had to submit was not very severe when we take into consideration all surrounding circumstances; their food was good, and there appears to have been plenty of it—in fact, the convicts in this respect fared quite as well as their keepers.

But the excessive heat constantly referred to, and complained of, by the Rev. Robert Knopwood, made continuous work irksome to men who had been enjoying or enduring a forced idleness on shipboard for so many months. To escape from this uncongenial toil, many convicts eluded the vigilance of their guards, and took to the bush. But they found out that by doing so they had jumped out of the frying-pan into the fire. The surrounding country was so barren that absconders were soon compelled to return. Yet, notwithstanding the non-success of these, hardly a day passed without one or more of the others running away, the object of most of them being to reach Port Jackson. A very hazy idea of the geography of their position prevailed among the convicts, it being generally imagined that the older colony was but a short distance off.

To correct this mistaken notion and lessen the number of escapes, the Governor printed notices warning all of the difficulties and dangers of such a desperate course, and the utter impossibility of men, almost naked and totally inexperienced in bush craft, being successful in an attempt to reach a settlement 1,000 miles away along the coast; and adding, that even should they by any chance elude the lynx-eyed and blood-thirsty natives, they would be immediately brought to justice and severely punished on their arrival at their destination.

In the month of November a batch of six convicts absconded, but in a few days returned in a very sorry plight, repentant and crestfallen. On this occasion the Governor determined to make a striking example of the culprits, and teach a solemn lesson to every convict in the encampment. He therefore ordered a general parade of troops and prisoners, and gave instructions to the chaplain to read his official commission as Lieutenant-Governor. After the ceremony he sentenced each of the miserable delinquents to a public castigation of 100 lashes each.

But this brutal punishment acted as no deterrent to their companions in durance, for it is reported that even so early as the next day some others made a bold dash for liberty. Three of these came back in such an exhausted state that the punishment cat could not safely be administered to them. In fact, their strength was so far gone that it was found necessary to place them under the care of the doctor. They stated to the authorities that their companions had levanted with the provisions while they were searching for water. This story proving the falsity of the old proverb about there being honour among thieves, the Governor attempted to draw a moral from the treachery, and hoped that so strong an indignation and mutual distrust would be aroused as to prevent in future any such combinations to break away from their lawful keepers.

Graver delinquencies broke out during the next month, among which were store-breaking and plundering. Even the tents of the sick were robbed of their provisions. On Christmas Eve a raid was made on the commissary's tent, and, besides other articles, a gun was made off with.

Christmas day came. The smiling sun shining in a brilliant Australian sky contrasted strongly with what our exiles had experienced in northern climes. But old associations and customs were not wholly forgotten or neglected under these new conditions, and a slight indulgence was offered to the prisoners in the shape of 1 lb. of raisins each for Xmas plum-pudding, so that all could enjoy this time-honoured Christmas luxury.

Our hero, Buckley, now appears on the records in a new light. He had started well. His behaviour on shipboard was exemplary, and a considerable amount of liberty was accorded him in consequence. Most of his time was spent on deck, where he made himself useful in a variety of ways among the seamen. The Governor took notice of him, being, no doubt, attracted by his fine upstanding soldierly appearance, and promoted him to the rank of his own body-servant, which position he held till his services were required to assist in the erection of the more substantial structures of the settlement—the powder magazine and storeroom—skilled labour, such as he possessed by virtue of his early training as a brick-layer, being lamentably wanting in the little community.

His ingrained hatred of hard or continuous labour again showed itself. Bricklaying had not agreed with him in his youthful years, and now in his manhood the old aversion marked another turning-point in his career. Perhaps the sudden change from flunkey to artisan had something to do with it this time. Anyhow, once more he listened to the voice of the tempter, and became a party to a carefully prepared plot, which was devised in company with five other black-sheep of the convict fold who longed for fresh fields and pastures new.

The work they were employed upon frequently took them outside the line of sentinels, and they availed themselves of any little opportunity that might offer itself to 'plant' provisions or any other articles they thought would come in useful to them in the bush. On the 27th December they were ready, and agreed to make a start for freedom that night.

When the shades of evening had given place to the deep gloom of night, and the last weary convict had at length fallen into a troubled slumber, and naught broke the solemn stillness but the drowsy sentinels on their watchful rounds, or the weird cry of a native bird or animal in the ghost-like bush around, then did the six conspirators quietly steal forth from the presence of their comrades into the outer air, pass the line of sentinels, and make for their secreted hoard. But—

"The best laid schemes o' mice and men

Gang aft a'gley,

And leave us naught but grief and pain

For promised joy."

and Buckley and his friends found this out to their cost.

They managed to 'spring their plant,' as getting away with hidden booty is called in convict parlance, but the authorities, suspecting that a number of the convicts had concerted a plot amongst themselves to break away, had that night stationed an extra line of outposts beyond the confines of the settlement. Unfortunately for the fugitives, these piquets were on the qui vive, and opened fire just as the retreating men began to feel that they had completely eluded the vigilance of their guards, with the result that one man was brought down by a well aimed bullet. Another one was so terrified and dazed at seeing his comrade fall that he paused in his flight and was immediately surrounded and captured.

Shot after shot reverberated through the woods, but none of the other runaways were hit. Dodging behind trees and bushes and any inequalities of the ground that they could take advantage of, they gradually got out of range and made good their escape.

We will now leave them for a time, and follow the fortunes of the settlement. The success of this daring outbreak greatly alarmed the authorities, who considered that so large a number of the exiles being free in the bush, was a strong menace to the maintenance of order within the boundaries of the settlement. It was feared that others would strive to emulate the enterprise of Buckley and his party.

The night-watch was immediately strengthened, and shortly afterwards a voluntary association of civil officers and free settlers was formed to assist the military in their police functions. The officers of this kind of special constabulary carried firearms, and the men were armed with batons. Their self-appointed duties consisted of a patrol of the encampment, independently of the military rounds. Being irregular in their movements, and not wearing a uniform like the soldiers, it could never be foretold by the convicts when or where they would turn up next, and consequently they soon became very useful in checking crime; and many an unfortunate misdemeanant was pounced upon by them, and promptly brought to justice.

In consequence of large fires being seen at some distance from the encampment, it was concluded that the escapees were still in the neighbourhood. It was therefore determined that an effort should be made to retake them.

With this object an expedition was organised on the 6th of January, 1804, in which the civil association and several marines joined their forces. They managed to follow the tracks of the fugitives for several miles, but could trace them no further, and perforce had to come back unsuccessful. No other attempt was made in this direction, as the Governor thought that it was unnecessarily harassing to the small force under his command, and he felt sure that the runaways would return or else perish by starvation.

A week after this fruitless expedition one of Buckley's companions surrendered himself at the camp, after having, according to his own account, accompanied his fellow fugitives almost around Port Phillip, a distance of one hundred miles. He brought back the stolen gun with him and stated that he had subsisted almost entirely on shell-fish and gum—a very inferior bill of fare, even for a convict.

The last days of the settlement were now drawing nigh. Lieutenant-Colonel Collins had never liked Port Phillip. He had pitched upon probably the worst spot upon its shores; and although he had sent out many exploring parties, these had performed their duties in so very perfunctory a manner that no practical good came of them. It is true that he was told of the existence of a large stream* at the head of the bay, but this he considered to be too far away from the entrance for the safety of such an establishment as his.

[* The Yarra]

Collins seems to have had an extreme dread of the natives, and they were reported to be very numerous and ferocious around the northern shores. The small body of troops at his command were scarcely sufficient to keep his unruly charges in check, and he deemed it too great a risk to venture further from the open sea, to a place where he would in all likelihood have a large body of black foes without his walls, to contend with, as well as the many white blackguards within.

Excessive prudence seems to have been a very noticeable feature of Collins's character. To us looking back over the past, and knowing what has been done by but poorly equipped later comers, his cautious conduct may be said to have amounted to timidity, and quite unworthy of the leader of a colonizing expedition.

Within a month after landing he was already seeking to quit Port Phillip. He had an idea that Van Diemen's Land would be superior both from a commercial and a military point of view. The following quotation from a despatch to Governor King clearly conveys his opinion of Port Phillip and at the same time shows what a bad prophet he was. He writes:—

'I am well aware that a removal hence must be attended with much difficulty and loss; but, upon every possible view of my situation, I do not see any advantage that could be thereby attained, nor that by staying here I can at all answer the intentions of the Government in sending hither a colonial establishment. The bay itself, when viewed in a commercial light, is wholly unfit for any such purpose, being situated in a deep and dangerous bight, between Cape Albany Otway* and Point Schanck, to enter which must ever require a well-manned and well-found ship, a leading wind, and a certain time of tide, for the ebb runs out at the rapid rate of from five to seven knots an hour, as was experienced by the store-ship. The Calcutta had fortunately a fair wind, and the tide of flood when she came in, and she experienced a very great in-draught, which had brought her during the night much nearer than she expected. With a gale of wind upon the coast, and well in between the two above-mentioned points, a ship would be in imminent risk of danger.'

[*Now Cape Otway.]

He writes further under date 14th November, 1803, to Lord Hobart, the Secretary of State, as follows:—

'I regret that I have not a better report to make to your lordship of the probable success of an expedition, equipped under your lordship's auspices with a liberality that inspired every one concerned in the undertaking with the most sanguine hopes of success. You may rest assured that what is possible shall be done by me to ensure it, if it should be Governor King's opinion that I am to remain here. I have suggested to that gentleman, in a private letter which I wrote to him, that Port Dalrymple, on the northern side of Van Diemen's Land, appears to possess those requisites for a settlement in which this very extensive harbour is so wholly deficient. Every day's experience convinces me that it cannot, nor ever will, be resorted to by speculative men. The boat that I sent to Port Jackson was three days lying at the mouth of the harbour before she could get out, owing to a swell occasioned by the wind meeting the strong tide of ebb. A ship would undoubtedly find less difficulty, but she must go out at the top of the tide and with a leading wind, which is not to be met with every day. When all the disadvantages attending this bay are publicly known, it cannot be supposed that commercial people will be very desirous of visiting Port Phillip.'

He was vested with discretionary power to remove the settlement, if he considered the site unfit, and he resolved to communicate with Governor King at Port Jackson, in order to find whether any port likely to be suitable for a colony had been discovered along the south coast of Australia.

It was, however, a difficult matter to convey his dispatch, as the Calcutta was wanted in the bay, and the transport Ocean, having completed her charter, could not be utilised without additional expense to the government.

In this emergency a cousin and namesake of the Lieutenant-Governor gallantly volunteered to make the voyage to Sydney in an open boat. His offer was gladly accepted, and he started, with a crew of six convicts, upon what turned out to be a most tempestuous and perilous voyage. After nine days' buffeting of wind and wave he and his plucky crew arrived within 60 miles of Sydney heads, when they were overtaken by the Ocean, which took them on board and carried them on to their destination. The despatches were duly delivered, and Governor King thus received the first intimation of the arrival of the expedition within the boundaries of his extensive dominions.

Governor King concurred with his coadjutor Collins, as to the advisability of removing the settlement to the island of Van Diemen's Land. Should the French attempt to form a colony in the neighbourhood he thought that they would more likely select that island than the mainland. He accordingly re-chartered the Ocean to assist Collins in the removal of his establishment across the water from Port Phillip, either to Port Dalrymple on the northern coast, or to Storm Bay on the southern coast, whichever he preferred.

The return of the Ocean on the 12th of December, with Governor King's reply was therefore gladly welcomed. The agreeable news brought by it was, however accompanied by the very disagreeable and disturbing intelligence, that war was again raging between England and France.

Captain Woodriff of the Calcutta, on learning this, resolved, with the true patriotism characteristic of a British sailor, to leave the colony, and bring his vessel within the fighting arena without any loss of time. Its departure, less than a week afterwards, somewhat inconvenienced the authorities of the settlement, and delayed arrangements for the removal; so that it was not till the end of January that the first shipload, consisting of one hundred and twenty convicts and twenty marines where taken on board the Ocean.

After sailing through Port Phillip Heads, it took her twenty days to reach the river Derwent, truly a very tardy voyage. She left again on March the 22nd, and did not arrive at Port Phillip till April 17th, a voyage of almost a month.

In three days the remainder of the establishment was embarked, and again sail was set. This time, owing to the very tempestuous weather prevailing, the voyage occupied the long period of thirty-five days, more than is now taken to steam half-way round the globe. The very elements seem to have protested against the abandonment of the settlement.

Thus the attempted colonisation of Victoria was finally relinquished by our colonel of marines and his recreant crew, and the native inhabitants were left for another generation to roam in the primeval solitudes of the pathless woods, or along the lonely beach of the sea-girt shore undisturbed by the unruly intrusion of the white invader.

THE FOUR ABSCONDERS—A GLIMPSE OF THE BLACKS—SUFFERINGS IN THE BUSH—SIGNALLING THE 'CALCUTTA'—BUCKLEY'S COMRADES LEAVE HIM.

HAVING seen the last of our first colonisers, we will now return and follow the footsteps of William Buckley. That worthy and his three companions kept close together, and made rapid progress in their flight through the bush. Fear lent them wings, and by the morning a considerable space had been placed between themselves and their late prison home. They then slackened their speed, feeling now very little apprehension of being pursued and retaken, as it was not customary for Governor Collins to prosecute a search to any such distance as they had by this time reached. However, to make assurance doubly sure they continued on till the shades of evening began to fall, when coming to a small creek they concealed themselves within a clump of tangled bushes, and lay down thoroughly fagged with their strenuous exertions.

They slumbered till daybreak. On awaking, they felt much refreshed, and relieved to find that they had not been disturbed during the night. They then unpacked their provisions, and ate a hearty breakfast. How to reach Sydney was the next question for consideration. Their instincts urged them to seek the haunts of fellow white men, and at Sydney they thought they would be able to mingle unobserved with the general population, and perhaps be enabled to earn a living as free men, or mayhap in time escape the country altogether and return to old England once more.

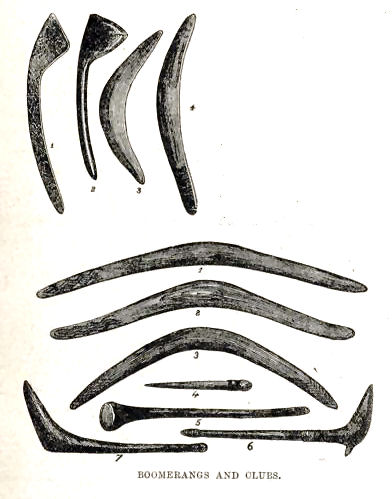

The creek on the bank of which they had slept now barred their progress. They travelled along it some distance, seeking a suitable crossing place, but could not find one. A number of natives suddenly appeared a little distance off, completely blocking the way and causing a fearful dread in the minds of the not over-courageous convicts. The blackfellows advancing towards them warily with spears poised and boomerangs ready for throwing, looked formidable indeed; but they were really as frightened of the unknown trespassers on their domains as our runaways were afraid of them, so that when Buckley discharged his gun they all made off with a terrified howl into the inner recesses of the woods.

Much relieved at this unexpected retreat of their black foes, the convicts determined to cross the creek without more ado. One of their number, however, had had enough of this perilous liberty, and refused to go any further. He therefore took the gun and began to retrace his steps. In spite of his faint-heartedness the others were not deterred. Buckley, being a splendid swimmer, stripped, and jumping into the water helped each of his companions over separately, and then returned for their clothes and the provisions.

A cumbrous iron pot or kettle which had been carried by the party all along was here thrown into the scrub, being no longer of any use to them, as they had eaten the provisions with which it had been filled, and they possessed no tea, that prime necessity to every true bushman nowadays. Buckley mentions in his autobiography that this pot was picked up thirty-two years after by a party of men who were clearing ground for agricultural purposes.

The creek crossed, their march was continued. By night time they were within a few miles of the present site of Melbourne. The Yarra was reached during the morning of the third day of their flight, and by the friendly aid of some fallen giant gums which had been caught by a natural bed of protruding rock they passed safely over to the other side.

The prospects of the party were now becoming ominous. Their original scanty stock of stolen provisions not having been supplemented by wild food of any kind, was by this time almost exhausted. Hunger stared them in the face, unless they could devise some means of obtaining sustenance.

They arrived at the foot of the You Yangs after a lengthy tramp over miles and miles of flat country. Here they ate the last morsels of their provisions.

They were now on the same footing as the native dweller of the soil, but without his experience in the art of providing for his daily wants.

Morning come, and they were assailed by the sharp pangs of hunger, but were without the wherewithal to satisfy them. Buckley proposed that they should make for the sea-shore, because to remain where they were meant certain death to all from starvation. Acting on his suggestion they turned their steps coastwards and reached the beach after a long and weary tramp. Here they found a few shell-fish which they devoured ravenously, and thus in a measure appeased their hunger.

Journeying on, they at length were fortunate enough to meet with a water hole, at which they quenched their thirst and then lay down beside it for the night.

Now their struggle for a merest existence began. They wandered despairingly along the shore, toilfully gathering such shell-fish as they could pick up on the sand or tear off the rocks, and now and then varying their diet with a crab or lobster, and supplementing these with gum which they found oozing from the trunks of trees.

This miserable and unwholesome fare soon injuriously affected their health, and they were forced by sheer exhaustion and pain, to halt for several days. When recovered a little, they resumed the march, on the way sighting several native camping-places, luckily deserted by their owners, much to the satisfaction of our runaways, for they were now less able than ever to cope with the savage native.

One morning they were surprised by discovering the white sails of the Calcutta, which was riding at anchor in the offing. They then knew that, instead of being on the road to Sydney, they had completely travelled round the bay to a point directly opposite the site of their old quarters.

Broken down as they were with their privations, they hailed the sight of the ship with wild exclamations of delight. If they could only get aboard the old ship again they would risk any punishment which might be inflicted upon them, rather than continue where they were, and suffer as they now suffered. To attract the attention of those on board they stripped off their tattered clothing, and waved it from branches of trees, the while gesticulating and shouting like madmen.

But it was of no avail; no one saw them. When evening came on they gathered a huge pile of timber and bushes, and made an enormous fire. But this had no better effect. Even if the blaze had been seen by the Calcutta people, they probably thought that the natives were the originators of it.

For several days they continued making the same signals, and at last were rewarded by seeing a boat put off from the ship's side and steer towards them, as they imagined. Deliverance then seemed so near that fear of the brutal punishment of the lash meted out to returned or recaptured absconders arose in their breasts, and nothing but the instant dread of death by starvation kept them from hiding themselves in the bush. However, this conflict of feeling did not last long, for the boat, after advancing some distance in their direction, turned its head towards the ship, and then both hope of rescue and fear of punishment vanished.

They continued signalling for a short time, but at length gave it up. Then, in desperation at their woeful predicament, Buckley's two companions signified their determination of retracing their steps around the bay, and surrendering themselves to the authorities. They argued that the lash of the taskmaster could not inflict greater suffering upon them than they were then enduring, and in the convict settlement they certainly had been served with a plentiful and regular supply of food, even if they had been compelled to work laboriously for it.

Buckley was earnestly urged to accompany them, but he obstinately repelled their entreaties, and said he would stay where he was, and risk any suffering and privation rather than surrender his liberty. The two men then reluctantly left him. Neither of them reached the settlement. They, no doubt, perished miserably in the bush, for they were never again heard of.

ALONE—SEES SIGNS OF THE NATIVES—RETREATS TO THE SHORE—DISCOVERED BY THE NATIVES—THEY TAKE HIM AWAY—ALONE ONCE MORE—TERRORS OF SOLITARY LIFE—RESOLVES TO GIVE HIMSELF UP—PERILS AND PRIVATIONS—TAKES SPEAR FROM NATIVE GRAVE—LIES DOWN TO DIE.

LEFT to himself we can imagine that Buckley's rejections were none of the happiest. Although not naturally of a social or a friendly disposition, yet he bitterly felt the loss of his companions in misfortune, and fain would have followed them, had not pride or stubbornness kept him back. Perhaps he thought they would return to him and urge him once more.

As the evening came on and melted into night he experienced a desolateness almost unbearable. The silent horror of his whole surroundings terrified and appalled him. Every moving shadow or gentle sigh of the breeze as it rustled through the branches of the overhanging trees, awakened within his mind an awful sense of his utter loneliness, and his distance from human help, at his own powerlessness, and a gloomy foreboding of the future.

Sleep he could not. Once or twice he fell into a sort of troubled slumber disturbed with dreams of his past life—every event of his fitful career obtruded itself upon him—his childhood's home, his disobedience of his parents' wishes, his old master the brick-layer, the recruiting sergeant, his soldier days when gallantly fighting his country's enemies; and so on to his disgrace, the convict ship, and the hard life at the settlement. All these passed vividly in succession before him as he lay there that night.

The rising sun at length told him that another day had broken. He got up and searched the beach in quest of shell-fish for breakfast.

After several days of mental prostration, during which he felt like one bereft of his reason, he somewhat recovered, and began to adapt himself to his new circumstances. Once more the old idea of reaching Sydney asserted itself, and he resumed his journey along the coast, still going however in a southerly direction, towards Cape Otway.

His movements for several days were accompanied by great privations, his staple article of diet being nothing better than shell-fish. Fresh water becoming scarce, he was forced to go a considerable distance inland to find some. Here he almost stumbled on an encampment of the dreaded natives, but he eluded them by swimming across a stream.

That night he had to sleep in his wet clothing, and awoke next morning suffering severe pains, and it was not till the day had well advanced that he was sufficiently recovered to be able to move about. To add to his discomfort a lighted piece of bark which he had carried with him was extinguished in the stream, and he had not the wherewithal to light a fire.

Another deserted camp again aroused his alarm but this time no natives appeared to be in the neighbourhood.

Thinking he would be safer on the shore, he made for it again, passing on his way a burning tree which had probably been set afire by the natives, where he obtained another torch. Here he also found some berries growing on a bush, and on taking his fill of them he felt much refreshed at such a welcome change in his diet.

For months this sort of life continued. Sometimes he had much ado to escape the watchful aborigines. At times starvation stared him in the face. On one occasion he was nearly drowned by the advancing ocean while he was asleep beneath the shelter of a huge rock.

At last he settled down to a listlessness born of despair, and instead of attempting his self-allotted journey, he wandered aimlessly to and fro within a radius of a few miles, with no other object than to procure his daily food. A low fever attacked him, and laid him prostrate for weeks. Luckily he happened at the time to be camped in a more sheltered spot than usual, having the protection of several shelving rocks around and above him, and a plentiful supply of fresh water trickling from a spring at a short distance off.

The fever gradually wore off. But he kept to the place, as it was the best he had come across in his wanderings.

Buckley called this nook his 'Sea-beach Home.' The place was to him what the fertile oasis in the desert is to the wandering Arab. He was there well provided with food, for besides having an abundant supply of shell-fish lying about on the rocky shore, there grew over the cliff a creeping plant, which in season, offered him numerous water-melons of a luscious taste, and there were also bushes in the neighbourhood which produced currants, both black and white. Faring daily on this variety of food, he continued to dwell there content with his lonely lot, or, at least, in a not unhappy apathetic condition.

At length the even tenor of his Robinson Crusoe-like life was rudely disturbed. Solitude had engendered a brooding habit, and in this he was one day indulging, and gazing in a meditative mood out to sea, taking little heed of the sights or sounds around him, except, perhaps, the ripple of the wavelets over the low rocks and shingly beach at his feet, when the sound of human voices broke on his ear and startled him from his reverie.

Standing up and turning quickly round he beheld three blackfellows on the cliff directly over him. A sudden impulse led him to hide himself, and he darted precipitately into a deep fissure between the rocks. Never perhaps had the slow-going Buckley moved with such celerity, and he fervently hoped, and half believed, he had escaped observation by the blacks. He was, however, soon bitterly disappointed. Bounding lightly down from rock to rock, they were in a few moments at the narrow opening, in the deepest recess of which he was crouched, and by shouting and beckonings they so worked upon his fears, that he thought it would be good discretion to creep out and stand before them.

The natives seemed wonder-stricken at beholding him. No doubt Buckley was the first white man they had viewed so closely, or, perhaps, ever seen at all. They examined him curiously, opening his shirt to see whether all of his body was white, and, uttering the while a sort of whine, caught hold of both his arms, and pulled here and there at his tattered garments. The scrutiny was after a few minutes completed by their striking their own breasts several times, and then that of their captive, who, still trembling from the first shock, thought their strange behaviour must be the prelude to some personal injury.

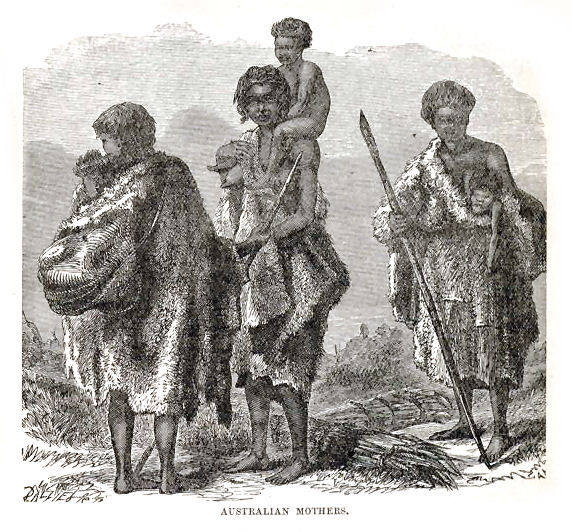

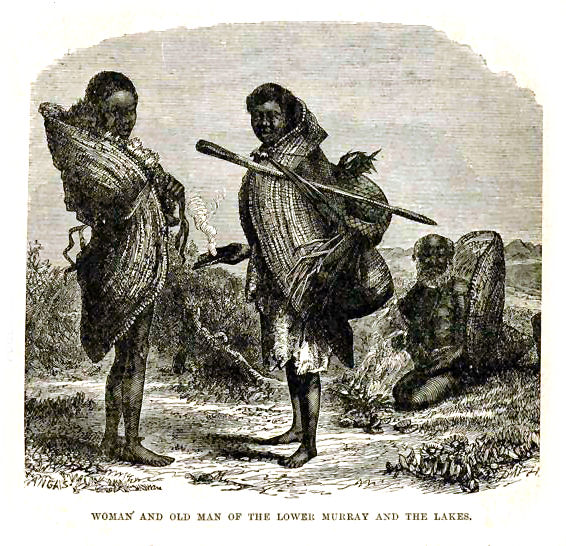

None of the three blackfellows were of very powerful build. Their limbs, from the elbows and the knees, tapered off towards the extremities, more than is the case with the average white man. However, they were wonderfully agile in appearance, and, moreover, carried spears of portentous length, which Buckley eyed with fear, for had they made a target of his massive frame, his naturally gigantic strength would have availed little. Over their fairly proportioned shoulders each wore a cloak of furred skin, the fur inside next the body. This garment reached almost to the knees.

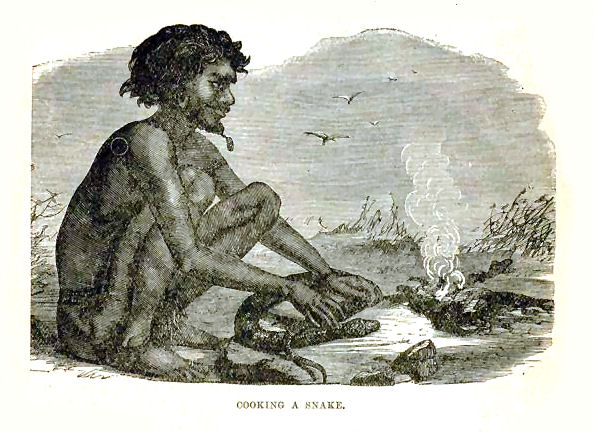

When the astonishment of the trio had somewhat subsided, they made an inspection of the rough shelter-hut which the lonely man had constructed, and after a time one of them, without any apology for the liberty he was taking with another man's property, used some of the material in making a roaring fire. Another threw off his only garment, and waded to some rocks a short distance off shore, and soon returned with a good-sized lobster, which he threw alive into the flames.

When it was roasted to his own satisfaction, he broke it in four portions, and generously gave the largest and best to Buckley, who felt greatly relieved in his mind by this evidence of hospitality. He had hitherto fancied that the first act of the savage natives on getting hold of him, would be to kill him for the purpose of banqueting upon the daintiest portions of his huge body. The lobster was eaten ravenously to the last morsel, and then the natives made signs to Buckley that he must go away with them. He was scarcely yet free from misgivings as to their intentions, and held out some time before he would understand their signs.

At last he was led quietly around the cliff and into the bush under their vigilant guidance until dusk, when they all halted beside two very rudely constructed bark and turf shelters. These were the mia-mias of the natives, and consisted merely of three stems stuck in the ground and inclined so as to support a few slabs of bark, which, with one end on the ground, leaned a contrary way so as to rest on the tree stems, the interstices between the bark slabs being filled up with tufts of grass. They were entirely open on one side, and of about sufficient height to allow a native to sit in them but not to stand, and the depth of each was just enough to afford shelter to a couple of natives lying side by side at full length.

The party divided and went to rest in these primitive habitations. Buckley, whose position was next the bark, was rather cramped by his bed-fellow, who was altogether an extremely offensive individual to pass the night with in such close quarters. Dirt and grease, with which he was bedaubed, increased the disagreeable odour natural to his black skin, and he kept awake throughout the night, muttering to himself as if in fear of some enemy; or was it the nightmare, brought on by an undigested portion of the lobster he had digested some hours before? This wakefulness prevented Buckley from slipping away as he intended to do in the darkness of the night; but at dawn when the natives wished to resume the march, he put his foot down against going any further.

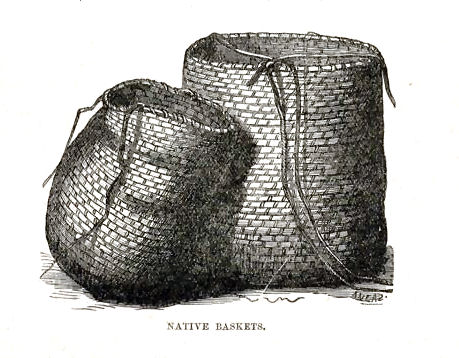

The blacks on this had some warm wranglings between themselves, and much violent gesticulations with their obstinate captive; but finally the victory remained with Buckley. They consented to leave him, but signified that they wished to have his tattered socks, probably as a pledge or maybe a souvenir. Luckily for him that he had Australian blacks to deal with. Had he been in the hands of the wild Red-men they might have insisted on taking a lock of his hair, with a goodly portion of his scalp attached. However, Buckley would not take the socks off, and although the blackfellows stamped their feet, struck their breasts, and looked disappointed and fierce, still he was obdurate. His determined opposition was in this instance also a complete success, for presently they went away. After several minutes one of them came back bringing with him a rush basket full of berries, which he offered in exchange for the much coveted convict hose. But Buckley, who, as we have seen more than once, could be very resolute at times, kept to his first determination, and the black, seeing that he could not gain his object, departed, leaving the basket of berries in the mia-mia.

This basket was a skilfully contrived article; the rushes of which it was made having been split and ingeniously entwined so as to make a small open basket of neat appearance. The berries, most likely the native cherry, were fresh and wet with the morning dew, and made a very acceptable breakfast to our unsocial and friendless wanderer.

Buckley waited a few hours, and finding himself again quite alone, made off as fast as he could towards the coast. He reached a spot where the sea beat violently upon a rocky and shingly beach. A short distance out were several seals, some sporting about, some sleeping on a cluster of rocks. He trudged along the sea-shore, and as the day drew to a close he looked about in vain for a supper, and then regretfully bethought him of the previous day's repast with the natives. He decided to return to them and started off in search of them, but lost his way in the endeavour, and went hungry to bed that night within the hollow trunk of an old gum tree.

During the day he had picked up a fire-stick—a torch of bark about two feet long, commonly carried by the native women from one camping place to another in order to ignite the domestic fire. With this Buckley lighted a fire in front of his natural bedroom, for the weather was chilly. The blaze attracted a number of wild dogs, opossums, and native bears, and the horrid howls of the one mingling with the shrill childlike cries of the others, kept the highly wrought man in a tremulously nervous state. Only once throughout that blood-curdling night did he peer into the darkness, and then, seeing nothing around him but the phantom-like trees, he turned his head and tried to shut out the hideous noises which seemed as a weird chorus in which he was the central figure, with invisible forms flitting everywhere above him and around him.

Towards morn the fire had burned low, and he cared not to venture out from his shelter to replenish it. A fitful slumber consequent on his thorough exhaustion from his long watching came over him, but it did not last long. Suddenly a hideous noise from the overhanging branch of a tree close by broke forth on the crisp morning air, and awoke him with a terrified stare. Gazing upwards in his fright he descried a number of brown sombre-looking birds rather larger than a pigeon, with clumsy heavy bodies and disproportionately large heads. Their widely distended beaks gave forth the unearthly combination of chuckle, hoot, and bray, which had aroused him from his sleep. The birds, to his imagination, seemed to be jeering at him, as just before each outburst they looked at him curiously and knowingly, with their heads slightly bent as if intent on peering into his very marrow. They were laughing jackass birds which have a delightful habit of arousing with their fiendish cachinnation just before sunrise, all lie-a-beds, human or feathered. Presently the other birds in the forest took up the strain, and the whole air was filled with the warblings and chatterings of thousands of the feathered race inhabiting the neighbourhood, and thus was heralded in the birth of another day.

As soon as the sun shed sufficient light, Buckley again essayed to track the natives, but ere the day was out he was completely bewildered by the labyrinth of gums and similar trees, and the general sameness of the landscape which has not unfrequently been noticed by later travellers. Consequently, for several days, he rambled distractedly through a thick bush, finding no food, and only occasionally getting any water. Every night he was visited with the same seemingly unearthly noises which had banished sleep when first heard. A man of average strength would, under such circumstances, have been completely tired out and unable to move; the giant Buckley, however, although gradually becoming more dazed, continued in a dreamy manner to wander here and there, sometimes obtaining a few roots or berries with which to stay the gnawings of his empty stomach.

At length he came to a large lake* at a spot where ducks, black swans, and other wild fowl in great numbers swam, dived, and hovered about its surface. In their very live condition they were a very tantalizing eye-sore to the hungry, helpless, and hopeless wanderer. He noticed that a stream of considerable size ran out of the lake, and believing that it emptied itself into the ocean, on the shores of which he would surely come across some creatures of a catchable kind, such as lobsters, mussels, and other shell-fish, he dragged his weary way along the river's bank and ultimately arrived at the beach, near to the place from which he had seen the seals gliding off the slippery rocks.

[*Probably Lake Connewarre.]

Somewhat cheered at recognizing the spot after the perplexities of his struggle through the bush mazes, he made another endeavour to reach the native huts. This time his efforts were successful, and lying down in one of them he indulged himself in a long, and much needed, refreshing sleep. On waking, he went out and picked handfuls of berries of the kind the natives had left him, and these sustained him for several days. His next movements took him back to his 'Sea-beach Home,' where he again settled down for a long period.

Winter came again, and the weather grew so inclement that the bleak beach became a miserable dwelling-place. As the cold increased, his chief food, shell-fish, became more and more difficult to find, and he began to think he had eaten out the neighbourhood. His clothes, too, after their long and rough services were worn to shreds, and afforded him hardly any warmth. The accumulating weight of these hardships was too much for the animal spirits of Buckley. His long sojourn in the bush by himself at last told terribly upon him, and completely cowed his stubborn nature. He longed for a change. Anything would be better than his present position. He therefore determined, like the prodigal son in the parable, to arise and go unto his legal keepers, and once more endure the thraldom of the convict settlement. With this intention he set off, bitterly regretting that he had not done so many months ago, when his more sensible companions had made up their minds to return.

One evening, when worn out with many days' trudging on the sands, he found himself hemmed in by the inflowing tide against an almost perpendicular rise of rock. To escape a watery grave he clambered into a large cavern just above high water mark, and was about to seek repose there for the night, when several seals or seal-elephants came splashing, snorting, sprawling in at the opening of his retreat. Being a close prisoner till the sea should go down he was horrified at their arrival. Fear caused him to spring up and utter a wild yell, and in so doing he struck terror into the slimy invading monsters. Scrambling one over the other they tumbled back again into their native element, leaving Buckley an easy victor, and sole possessor of their rocky lair. They did not again disturb him during the night, and when the tide receded next morning he resumed his return journey.

He made but little progress. His strength was failing fast, and he could keep up for only very short stages. After several days he got back to the river in which his first fire-stick had been extinguished, and on its banks he dragged himself into a thick scrub.

Here he constructed a rude shelter to protect himself in a measure from the icy coldness which severely affected him, and then he went to sleep. Waking early in the morning his eyes lighted on a mound of earth with part of a native's spear stuck upright on top of it. He was in want of a strong staff to support his enfeebled body, and, therefore, feeling no compunctions in desecrating the grave, if indeed he knew at the time that it was a grave, he appropriated the spear. This spear subsequently proved a veritable staff of life to him, as we shall see later on.

Next day he nearly lost his life in crossing the river, which was running with a swift and flooded current. He was carried some way down stream, but by good fortune an eddy or cross current drew him near enough to the oppose bank to enable him to clutch an overhanging branch, and with its assistance he struggled out. After these great exertions, so exhausted was he, that it was with the utmost difficulty he managed to crawl on his hands and knees to the shelter of a few bushes, where, bitterly cold and miserable, he lay down and passed a most wretched night.

He felt that his last hours had now surely come. The dismal dingoes' horrible howls in the surrounding darkness, awakened anew in his breast the old superstition common all over England, that a dog's howling always forebodes death; and he felt that it could be none other than he who would now be the victim of the grim and gaunt messenger of eternity.

But when morning broke, the instinct of self-preservation asserted itself, and he determined to postpone for a day at least the feast which the dogs seemed to presage they would have on his carcase. He hobbled about from tree to tree picking gum bit by bit, and eating it as he went. However, the exertion soon became too much for him, and he was presently forced to abandon his search for food and sink to the ground at the foot of a large Eucalyptus. In blank despair he lay there, he knew not how long, awaiting death to end his sufferings. With his spear clutched convulsively in one hand, he at length swooned away.

SAVED FROM DEATH—JUMP UP, WHITE-FELLOW—PERSONAL APPEARANCE OF HIS NEW FRIENDS—THEIR ECCENTRIC BEHAVIOUR—THE BLACK ENCAMPMENT—A TRIBAL JOLLIFICATION—PRIMITIVE ANGLERS—'POSSUM HUNTING—CLAIMED AS A RELATIVE—PRESENTED WITH NATIVE GARMENTS.

ALTHOUGH hope was gone, help was close at hand. While he was thus lying there, the sharp eyes of two dusky daughters of the forest perceived him, and, with the truly universal curiosity of their sex, approached closer to get a better view. It is not surprising that they were greatly astonished, if not alarmed, when the closer inspection revealed to their gaze a man different from any they had ever beheld. To convey to their husbands the intelligence that they had discovered a monstrous man with white features and limbs, did not take them long, and very soon those worthies returned with their better, and uglier, halves to the spot where the object of their discovery lay prostrate.

With a caution quite natural, although there were four to one, they surrounded him. Then, seeing that he was utterly helpless and bearing the marks of long privation, they summoned up sufficient courage to touch him. This aroused Buckley from his stupor, and he struggled into a sitting posture with the help of the spear, which had all this time been clutched by him as a dying man clutches a straw.

As he gazed in a dazed sort of a way at them, he looked like one just arisen from the dead. And this idea seems to have taken hold of the minds of his black discoverers, for these simple-minded children of nature, on seeing the familiar spear in his hand, thought they recognised in Buckley the re-embodied ghost of a departed warrior belonging to a neighbouring and friendly tribe, at whose burial they had only lately assisted. According to aboriginal theology, the spirit of the late lamented man ought to be still hovering around. It was also an article of popular belief that the black-fellow after death jumped up white-fellow, and here, truly, was a case in confirmation. *

[* "They have a belief that when they die, they go to some

place or other and are there made white men, and that they then return

to this world for another existence. They think all the white people

previous to death belonged to their own tribes. In cases where they

have killed white men, it has generally been because they imagined them

to have been originally enemies, or belonging to tribes with whom they

were hostile. In accordance with this belief, they fancied me to be one

of their tribe who had been recently killed in a fight, in which his

daughters had been killed also."

Some observant writers on the aborigines dispute this. They aver

that it is a modern notion derived from intercourse with the whites

since the first settlement of Port Jackson in 1788. Other reliable

authorities hold with the statement here quoted from Buckley's

autobiography.

The belief or idea probably is a very old one, at least among the

tribes whose territory bordered on the sea coast. It may have taken its

rise from the fact of white men occasionally landing. The blacks, not

knowing how to account for their appearance from the illimitable ocean,

settled the matter by inventing as an explanation the legend expressed

in the words: "Go down black-fellow, jump up white-fellow."]

They laid hold of the worn-out Buckley by the arms, and, after greeting him with friendly thumps on the chest, managed to set him on his feet. Then the women got one on each side and helped him along, while the men marched on ahead shouting, making hideous noises, and wildly tearing their hair, and behaving in a very extraordinary, not to say extravagant, manner generally. Whether these gesticulations and outcries denoted joy or sorrow, Buckley does not say.

They proceeded thus for a short distance and came to a couple of mia-mias where the women obtained a bowl or calabash, a rough sort of basin made by the natives out of the knotty excrescence of a tree by the aid of fire and a flint stone, and into it put gum and water which they mixed into a pulp and offered to the almost expiring Buckley, who devoured the mixture eagerly. Next they gave him some large fat grubs, which the women procured at the roots of trees and underneath decayed logs. These grubs completed his meal, and such was his famishing condition at the time that he thought them delicious, and a luxury equal to the sweetest marrow he had ever tasted. The meal ended, Buckley felt greatly revived, although still very weak.

Notwithstanding the hospitality shown to him, he had no confidence in a continuance of the good offices of his black benefactors, and would have left them had he been able.

He did not like their looks. Certainly they were not beauties. More foreboding countenances could scarcely be imagined. The nose was flat, with widely distended nostrils, and had through its septum, as an effort at ornamentation, a short stick or reed, which certainly did not add to their attractiveness in Buckley's eyes. Their mouths were large and cavernous, with hanging heavy thick lips; below these a large underjaw denoted great strength, very necessary for the tearing asunder and mastication of the coarse food they had to subsist on, their teeth performing many offices which civilized people delegate to knives and forks. Remarkably quick eyes, sunken afar back and overhung by bushy brows, bespoke a watchful and suspicious, if not a treacherous, nature. Retreating foreheads and high cheekbones completed the delineation of their features. Surmounting all was a luxuriant growth of jet black hair on the head of both men and women, and rather longer on the latter. Both men had thick shaggy beards, and on shoulders and chest the hair also grew strong and thick. Each had a band made of bark fibres wound round the head, either for ornament or to keep the hair within bounds. Their faces might be described as speaking faces; every mood was reflected in them as in a mirror. In repose they bore a very sullen, not to say morose, aspect, but when interested in anything this completely vanished, and in its place a most animated and bright expression revealed to the onlooker that the blacks had within them considerable vivacity and nerve.

They could not boast of extravagance as regards dress. The women's attire was bunches of feathers tied with a bark cord at the waist, and hanging around the loins in form of a skirt somewhat shorter than that of a stage fairy; while the men were content with wearing strips of furred skin depending about 12 inches before and behind from a skin belt.

Both sexes had slim limbs and walked pigeon-toed, but with a graceful and an active step. The bodies, it might also be mentioned, were plentifully bedaubed with the fat of some animal; this probably served a utilitarian as well as an ornamental purpose, for the greasy coating must, in a measure, have warded off the inclemencies of the weather from their otherwise almost bare skins.

During the night Buckley was continually disturbed by the moans of the women, who seemed to him to be lamenting deeply over something that had happened. Next morning he observed that their faces and limbs were frightfully lacerated. Their natural ugliness had been largely augmented by the wounds from which blood was flowing freely. It was a frightfully sickening sight to him, and made him still more eager to quit such undesirable company. If, thought he, they could thus inflict such pain or torture upon themselves without any apparent reason, what might they not do to him should they choose to consider him as enemy.

Early next day the men by signs told Buckley they were going a journey on which he must accompany them. The start was soon afterwards made, the men in front with Buckley in the middle between them, the women, carrying the baggage, following at a little distance. The blacks were all watchful that their captive should not escape them, and marched along in silence until a river (now called the Barwon) was reached. After a while they forded the river, and on the other side of it entered on a marshy plain, where Buckley, to his great dismay, detected the forms of numbers of natives moving about among the scrub. On seeing him and his captors, whom they evidently expected, fully one hundred natives emerged and steered towards them. Presently Buckley, quivering from head to foot with anxiety for his future safety, was closely regarded by their enquiring and interested looks, while his rescuers told with a great deal of volubility the story of their wonderful discovery.

This introduction to the tribe was a trying ordeal to the runaway convict, but at length his fears were in a measure allayed when he noticed that no blood-thirsty passions seemed to be awakened in their black breasts by the recital. He was soon conducted to the native encampment. This was on a rising ground, and consisted of a number of rude bark-and-bough dwellings, built in similar manner to those already described in which he had previously lodged. Besides these, there were other shelters in the camp which gave no protection at all on top, they were merely boughs and bark heaped up to a yard or so in height to form a screen or shelter of a semicircular form, and might properly be described as 'break winds,' for they were nothing more. Before each of these primitive structures was a little fire, notwithstanding that the day was rather warm, for the aborigines were partial to heat, and also never neglected to keep the domestic cinders in readiness for a chance broil.