a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Tapestry Room Murder Author: Carolyn Wells * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1900881h.html Language: English Date first posted: August 2019 Most recent update: August 2019 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Chapter 1. - Who Did This Thing?

Chapter 2. - Who Was in the Room?

Chapter 3. - It Had to Be One of Them!

Chapter 4. - Make Your Own Will

Chapter 5. - A Flood of Questions

Chapter 6. - Sky-Eyes and the Other Girl

Chapter 7. - Odors of Evidence

Chapter 8. - Fleming Stone Takes Up the Case

Chapter 9. - The Ticking Clock

Chapter 10. - Abbie Perkins Helps Along

Chapter 11. - The Reconstruction

Chapter 12. - The Mysterious Ticking

Chapter 13. - The Persistent Mothballs

Chapter 14. - Real Clues At Last

Chapter 15. - It May Have Been Cale

Chapter 16. - Another Tragedy

Chapter 17. - The Man With Jane Black

Chapter 18. - The Solution of the Whole Matter

THE room was black dark. The sort of darkness that is described as Cimmerian, Stygian, Egyptian, but is called by most of us, pitch-dark.

Though invisible by reason of the darkness, it was a beautiful room, filled with interesting and valuable pictures, tapestries, curios.

Nor were the people in the room visible to one another. Only could be heard the breathing of its occupants, calm, ordinary breathing, as of untroubled breasts and care-free minds.

Scents there were. Darkness could not conceal those.

Faint, elusive perfume of cyclamen; heavy, haunting fragrance of jasmine. A suggestion of tobacco. Another pungent familiar odor—indescribable but unmistakable—the clean, homely smell of mothballs. And over all, circling in invisible spirals, the oppressive yet poignant fumes of burning incense.

And then, with a sudden flash the place was illumined.

Not glaringly; save for a pair of shaded lamps, the lighting was indirect.

The room revealed itself as a man’s library or sanctum, four-square, each side a deep arched alcove, lined with bookshelves.

The arches framed mural paintings of beauty and worth. The shelves held books of all sorts; antique tomes and rare bindings neighbored by the latest novels and mystery stories.

The thick rugs were Oriental gems and the few pieces of furniture were masterpieces of celebrated designers.

On a small sofa, the sort known as a love-seat, sat a man; on either side of him was a girl.

The man was not sitting upright. He had slumped a little, and his head had fallen forward till his chin rested on his chest.

One girl, a vivid, scarlet-clad little figure, perched on the arm of the love-seat at his left. The other, a tall, serene, Moon-goddess type, stood, frozen with fear on his right a few steps from the couch.

A low moan that rose to a shriek came from one of these girls, as she paled, swayed, and fell to the floor.

The occasion was a small party in honor of the birthday of Gaylord Homer, the host.

Twin Towers, his small but charming home, was in Westchester, in the exclusive and highly restricted community of New Warwick. It was not a new place, but one of respectable age and tested and tried desirability.

So Gaylord Homer bought himself a place there, and now proposed to take unto himself a wife. He had decided upon his choice, and though he had not yet brought the lady to see the matter in the same light that he did, he had every hope of yet achieving that expectation.

The lady’s name was Diana Kittredge, and though that might seem formidable of itself, Gaylord Homer was not afraid of mere words and he was determined that this party of his should be the Rubicon which, when crossed, would change that surname to his own.

As to her Christian name she was mostly called Di, and also, Sky-eyes, a nickname not especially euphonious but wondrously descriptive.

Homer, himself, was a delightful chap, whose outstanding traits were geniality and capability.

Also, he was loyal to his friends, generous to his enemies and kind to his dependents. And if you think that writes him down a milksop, you’re dead wrong.

He had a bull-dog tenacity of purpose, and if he wanted a thing he got it by sheer persistence and perseverance.

That was the way he expected to win his Diana, and the fact that she had not yet said yes to his pleas discouraged him not a bit.

He loved her with the sort of love, he sometimes assured himself, that the wingéd angels of heaven had coveted Miss Annabel Lee.

In fact, he thought Miss Lee’s affair rather picayunish beside the surges of affection that swamped his own heart when he thought about Sky-eyes, and he resolved anew that this paragon of girls was for him and he must get the matter settled.

Hence the birthday party, which was to last over the week-end, and which he strongly hoped would develop into an announcement party before it closed.

It was Friday now, the party had materialized and dinner was in progress.

Diana, the azure-eyed divinity, sat at the right of the host. Her soft, fair hair, parted in the middle, waved over her ears in a curling riot, but was short at the back. Her exquisite face had a translucent effect, as if her soul was shining through, and her gentle, regular features were as serenely beautiful as those of the Mona Lisa.

Perhaps her greatest charm was her mouth and teeth, and the smiles which they helped to make proved the undoing of many a man who watched, fascinated for their return.

In an exquisite, though severely plain gown of silver tissue, Diana was a veritable Moon-goddess, and Gaylord Homer, glancing at her now and again, concluded she was perfect.

Save for one thing. She would scarcely look at or speak to him.

Never rude or noticeably neglectful, an unobservant guest might have thought Miss Kittredge was all a host could desire in the matter of cordiality. But Homer saw the effort she made when she voluntarily addressed him, the veiled indifference in her larkspur-blue eyes.

He fully sensed that she had no intention of saying yes to his pleadings, but that only made him the more determined and the more sure of ultimate success.

Truly, the human genus is a strange proposition.

Now on the other side of Homer sat a girl who was positively eaten up with her love of him. With all the strength of her exotic nature she adored this man.

Marita Moore, whose father was an undistinguished, average American citizen, had had foremothers of Spanish descent, and all their amorous impulses, all their tricks of temperament, had merged and flourished in this youngest scion of the hot-blooded line.

Marita, who looked the part, was small and lithe and sinuous. She was dark and her air was both domineering and defiant.

Her long, black eyes were now sleepy and langorous, now provocative and daring. Her short frock was red—the red of the hibiscus, of the cleft pomegranate—and in her black hair, though it was short, she had managed to thrust a high gold comb, that gave the final touch to her Castilian effects.

Her little hand continually clutched at the sleeve of Gaylord Homer’s coat. She almost seemed as if trying to take him by force.

In a way, it was absurd.

Marita loved the man as he loved Diana. He scorned Marita, as Diana scorned him. Marita was determined to win him, as he was determined to win Diana. And he was as determined that he would never marry Marita as Diana was determined she would never marry him.

A triangle, indeed. An infernal triangle. Whatever happened, one heart must be broken, if not two—or three.

Three strong wills in a mortal clash. One, at least, must give way.

Then, there was another element.

The other side of Diana sat Ted Bingham, a chum of Homer’s. He, too, adored Sky-eyes, and he thought, he hoped, she cared for him. But who could tell what she meant when those red lips and those mother-of-pearl teeth smiled at him?

And what had he to offer, a poor young sculptor, with nothing but faith in his own work? While Gay Homer had everything—everything a goddess could ask for on this earth.

With a suppressed sigh, he turned to his other neighbor, Mrs. Bobbie Abbott, a rollicking young married woman, the scapegrace of the party, and, incidentally, its chaperon. One of the most frivolous, vain and rattle-pated of her set, she still had a fine sense of relative values and a good bit of perception.

She saw how things were going and in a low tone, advised Ted not to give up the ship as yet.

The rest, round the table, were Rollin Dare, opinionated, but likable, Polly Opdyke, a flapper neighbor, and Cale Harrison, the confidential secretary of the host.

That was the party of Gaylord Homer’s birthday dinner, and as they were all fairly well acquainted, conversation was hilarious and repartee untrammeled.

“Why not give up the ship?” Bingham growled, in an undertone to Bobbie. “No girl could stand out against Gaylord’s arguments. He is fine, himself, and he lays at her feet all a woman can ask for. Wealth, position, power, and a love that is mad adoration, How can Diana resist all that?”

“Now, now, lamb, don’t take it thataway. What’s it to her, if she cares for somebody else—you, for instance. And she does—that is, I think she does,” she hastily amended, for Ted seemed about to burst into song.

“You must get ahead of him some way,” the wiseacre went on. “I, too, can’t see how Di can hold out against that charmer. He’s mad about her. Oh, if he’d only turn to the little vamp in red! She’s determined to snatch him from Di’s very grasp.”

“Di isn’t grasping him—look at her.”

“No, but that may be her clever way of egging him on.”

“She’s no egger.”

“Well, good Lord, Teddy, what do you want me to do? I try my best to pet you up, and you only growl at me. If I can help, I will.”

“You can’t, nobody can. When Gaylord gets that queer little set look in his eyes, I know he means to fight to a finish.”

“Fighting won’t get him Diana Kittredge.”

“It may. He may keep at it till she gives in from sheer exhaustion. And, Bobbie, she mustn’t marry him! No, that isn’t just jealousy, there’s another reason.”

“What is it?” the alert mind sensed gossip.

“Never mind, now.”

“Oh I hate those blind hints. They never mean anything, anyway. Well, I must babble a bit to this incubus on my other side. But look at the secretary person. He, I happen to know, is consumed with a burning passion for the firebrand in red.”

“No! I can’t imagine Cale Harrison being consumed with anything for anything. He is the timidest bunny I know! He wouldn’t dare raise his eyes to Marita’s mascara-dipped lashes!”

“Oh, wouldn’t he? I know he has that, Friday afternoon, speaking pieces air, but secretly he feels himself superior to Gaylord himself.”

“Superior!”

“Yes. He scorns Gay’s money and leisure, just as he scorns your sculping. You know these inferiority complex people are really exhibitionists, their humility is just part of their pose.”

“But Harrison is really a mush of apology, he’s always afraid of being in the way or something.”

“Yeah, that’s the way it takes him. But look at him, he’s watching Marita vamp Gaylord, and it’s picking out his stitches. See him squirm!”

“Yes, he looks as if he was just wishing he had the nerve to pick up Marita and run away with her.”

“He has nerve enough but he’s a creature of habit. He has behaved himself so long he wouldn’t know how to set about doing anything desperate or even unconventional. Now I must love my neighbor as myself, on the other side.”

Bobbie turned to Rollin Dare who drew a long breath of relief.

“Well, I thought you hadn’t any bringing up at all! So you remembered I was here.”

“I haven’t had another thought since we sat down! Been jus’ a waitin’ for you!”

“All right, all right. But if you flirt with Teddy Bingham I’ll tell your husband on you. Anyway, you waited too long. Gaylord’s going to chase us out now. You stay by me.”

Homer was a law unto himself in his own house. He had coffee at the table, and then the whole party, men and women, rose together and adjourned to the lounge or wherever they chose.

But it was Gaylord Homer’s invariable custom, for a reason of his own, to go always, from his dinner table to a small room next the dining-room, which was called the Tapestry Room, by reason of some bits of choice and valuable tapestry which adorned its walls.

The house was built with what Bobbie Abbott called the front door on the side.

This was literally true.

The house was of that old-fashioned type whose large front room is a living-room or lounge. The back room is a dining-room, with a breakfast-room annex, and these two ends are connected by a long hall and another room.

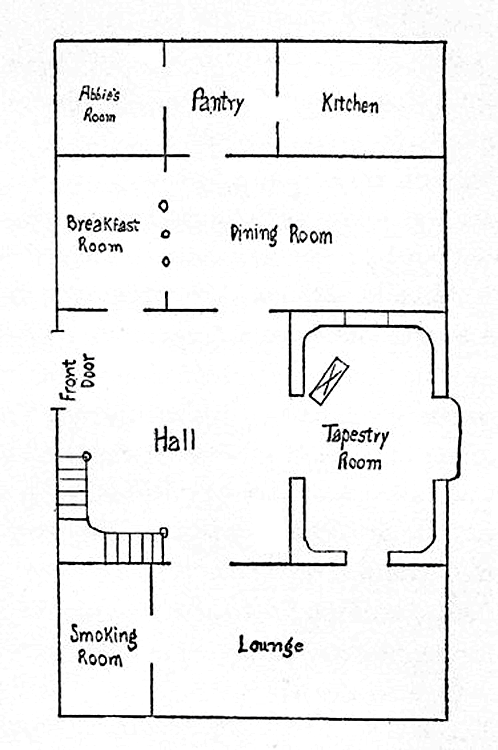

Perhaps a plan would be advisable here.

From the pleasant candle lighted dining-room, they went to the hall, and from there, dispersed as they chose.

Rollin Dare, having corralled the elusive Mrs. Abbott, held on to her arm, and piloted her to the lounge and to a pleasant divan in a corner, where he provided her with a cigarette and then sat beside her.

Ted Bingham followed the pair, but Gaylord Homer paused at the curtained entrance to the Tapestry Room.

“Come in here with me, Di,” he said, his low, delightful voice taking all sense of command from his words.

“No,” she began, but he took her hand and led her over the threshold.

She couldn’t draw back without seeming too ungracious, and reluctantly she went along with him.

Marita, bounded to his other side, and clasped her two fluttering hands round his arm.

Seeing this, Diana tried to leave the group, but Gaylord held her fast.

“No, no, my lady,” he cried, laughing low. “You can’t get away! You can, Marita.”

“But I won’t,” she said, obstinately, her lovely face leaning near his own. “I want to come, too.”

So the trio went together into the room.

A perfect room, four-sided, in each side an alcove of bookshelves. Here and there pictures and draperies, including the rare tapestries that gave the room its name.

Through the draped portières they came from the hall, and Marita gayly drew Homer down on a small couch, one of those short sofas called a loveseat, and then perched herself on the arm of it.

Diana still stood at Gaylord’s other side.

He was looking at her, though Marita was striving to gain his attention.

Ted Bingham, who had gone into the lounge, came to the door between the lounge and the Tapestry Room, and looked in to note the situation.

Polly Opdyke, childishly curious, drew near Ted, to see what he was looking at.

Ted glanced at a clock.

All knew what would happen next.

The village of New Warwick, during the day and evening was supplied with electricity for lighting and power from a five hundred horse-power dynamo, driven by a Diesel engine. But after ten o’clock, most of the town retired and the street lights and those of residences that used electric light were supplied from a fifty horse-power generator and engine.

So each night when the larger engine was shut down, the engineer disconnected the lighting circuits from the main bus and transferred them to the bus supplied by the small generator, after which the voltage was raised and the light burned at normal brightness.

It should have been the work of a minute or two, but owing to the slowness of Old Tom, the engineer, the operation often consumed two or three minutes and sometimes even more.

Hence a few moments of complete darkness occurred every night shortly after ten o’clock, and so accustomed were the citizens of New Warwick and vicinity that it raised no comment and seldom interrupted their occupations.

Talk went on without cessation, readers merely held their books or papers ready for the light which would soon return.

Bridge players held their cards and chatted a moment, then resumed their play.

But, whether from a nervous fear of burglars, or for what reason, Homer never said, he always spent those dark moments in the Tapestry Room.

The assumption was that he wanted to be on the spot if some evilly inclined intruder should attempt to walk off with some of his treasures. For the room was full of curios and rarities that represented a large sum in value and were too, in many cases, unique and irreplaceable.

All of the guests knew of the dark time, as it was always called, and though it often came as a surprise to those not noting the hour, yet they immediately bethought themselves, and waited for the flash of returning light.

And so, as Gaylord Homer sat on the miniature sofa, with Marita on the arm of it, and with Diana standing, haughty and inaccessible at his other side, the lights went out.

There was a little squeal from Polly in the lounge.

Polly always squealed when the lights went off, though living next door, as she did, her home invariably had the same experience.

Bobbie Abbott, still devotedly attended by Rollin Dare, was curled up on her divan, her cigarette just about consumed.

She put it out and dropped the stub in an ash tray, saying she liked it all dark better.

As Dare’s arm stole round her shoulder, she wriggled a bit, not knowing how long the darkness would last.

It seemed a long time though, to the others, and it was nearly three minutes. Astonishing how much longer three minutes is in the dark than in the light. But at last the lights flashed on, and Bobbie straightened up, quickly and calmly returned the curious glance Polly Opdyke shot at her.

And then a scream came—a short, sharp, frightened scream, that came from the Tapestry Room.

It was followed by a soft thud, as if someone had fallen.

Bingham, standing near the entrance to the Tapestry Room, from the lounge dashed through the archway and stood gazing.

He seemed so stunned for a moment, he made no sound at all, then, hastening forward, he helped Marita, who had fallen, to her feet.

But the girl could not stand, and Ted placed her gently in a chair and then turned to the slumped down figure of the love-seat.

Gaylord Homer sat, huddled, his chin resting on his chest, his arms sprawling, and his shoulders beginning to give way.

Near him, Diana was backing away, farther and farther away, with a dreadful look of fear on her beautiful face.

Marita, from the chair where Ted had landed her, had roused and was staring at the scene.

She began to scream but thought better of it and clapped her hands over her mouth.

Then Rollin Dare came bursting into the room, and stepping toward that awful figure that was so strangely still and huddled, he called out “Help!” As he came nearer, he caught the gleam of metal and saw that Gaylord Homer had been stabbed in the back, stabbed with a jeweled dagger, a weapon familiar to them all; a weapon that had long lain on the curio cabinet near by, that was one of Homer’s choicest and most valuable treasures.

Dare touched the dagger, was about to withdraw it, when Bobbie Abbott, who had followed Dare, cried out:

“Oh don’t Rollin! Don’t touch it! Get a doctor, quick!”

This bit of sound common sense brought reaction from Dare, and he said, “Where is one? Is anybody here a doctor?”

“Dad’s a doctor, shall I fetch him?”

It was Polly Opdyke who spoke in a frightened voice but determined to help.

“Yes, child, run!” cried Dare, as he tried gently to raise Homer’s head.

And then Cale Harrison suddenly appeared.

“What’s this?” he cried, harshly. “What’s the matter?”

“Gaylord’s been stabbed,” said Ted Bingham, himself trembling with horror.

“Stabbed! Heavens!” Harrison’s exclamation was lusty enough, but next moment he almost collapsed, himself, and leaned against the jamb of the doorway for support.

In an incredibly short time, Dr. Opdyke appeared and took charge of the situation.

A moment’s examination brought the decision.

“He is dead,” Dr. Opdyke said, solemnly. “Who did this thing?”

JUST to look at her you would know her name must be Abbie Perkins.

It couldn’t have been anything else. Tightly drawn as to hair, skin, and clothing, she stood, motionless, in the curtained doorway between the Tapestry Room and the hall.

A wiry little figure of a woman, the coiled knot at the back of her head so taut that it seemed the reason for the prominence of her round brown eyes. Thin, angular, flat, she seemed cut out of tin.

She had about as much of the quality recently dubbed sex appeal as an icepick, and this fact she knew so well and resented so fiercely that she was jealous and envious of every woman who had what she lacked. That subtle, elusive lure, much written about of late, but no more a decisive factor in a woman’s fate now than in the most ancient of days.

The law of compensation gave her common sense, efficiency, housewifely skill and an uncanny intuition that was almost clairvoyance.

Any or all of these things she would joyfully have bartered for a half ounce of charm. Yet a real sense of humor saved her from misanthropy or sulks and Abbie Perkins was a success in her own field.

She was housekeeper for Gaylord Homer, and it was her generalship that kept things running smoothly, for a home without a mistress is not an easy proposition.

Always an inveterate talker, she stood now silenced and aghast at the scene before her.

“What is it?” she breathed, clasping her bony hands together and staring at the tragic figure on the little sofa.

“Be quiet, Abbie,” said Dr. Opdyke, warningly; “Mr. Homer is hurt.”

“He is dead,” she said, in a sharp tone. “What can I do?”

The doctor flung her a grateful glance.

“That’s the way to talk,” he said. “You can do nothing here, Abbie, but you can help a lot by looking after the servants. Don’t let them get excited or hysterical. Where is Wood?”

“Here I am sir,” and the butler appeared from the dining-room door.

“Stay in the hall, Wood. Let no one pass in or out until the police can get here to take matters in charge.”

“Police!”

It was Bobbie Abbott who spoke, but the dread and horror in her voice found its echo in the hearts of all present.

No one had spoken since the doctor’s awful question. And now, the mention of police brought home to all of them the sudden realization that here was murder and it must be dealt with by the law.

“Yes, of course,” the doctor snapped out. “Who is in charge here?”

He looked about. As he well knew it was Gaylord Homer’s house, Gaylord Homer lived there alone, and now Gaylord Homer sat, helpless and still before their eyes.

There was no one in charge, if not Homer.

Abbie Perkins had gone to look after the frightened servants. Wood stood at attention in the hall, but these were not the ones to take charge.

Then the doctor’s eye lighted on the secretary, Cale Harrison.

“You must take charge for the moment, Harrison,” Dr. Opdyke declared. “As confidential secretary it is your place to do so, at least, until we can get his relatives here. Where are his people?”

“He hasn’t any, except a distant cousin.”

“Well, never mind that now, anyway. The thing to do first is to call the police.”

It was hard on the doctor, for in all his experience he had never been in a situation like this before, and though an able physician, he had but small power to meet this emergency.

He looked about him at the crowd of young people, he looked at the white scared face of Diana Kittredge, the drawn, tear-stained countenance of Marita Moore, the blank faces of the men, and he was glad indeed when his wife came across the hall and stood at his side.

Acting on his orders Wood had denied her admittance, but Emily Opdyke had insistently pursued her way, unheeding him.

“What has happened?” she whispered. “Who did it?”

“We don’t know,” her husband returned. “Look after Polly and do anything you can for the others.”

There was someone in charge now, at least so far as the women were concerned. Mrs. Opdyke was tactful and kindly by nature, and always ready in an emergency.

She made all the women go with her into the lounge, she ordered coffee brought to them there, and found cigarettes for them. Marita she made lie on a couch and bathed her brow with violet water. The girl was almost in hysterics, but Mrs. Opdyke’s ministrations calmed and soothed her.

Diana refused all such nursing and sat in a big armchair, looking inscrutable and a little defiant.

Bobbie Abbott was regaining her composure and wondering why she hadn’t had sense enough to do the very things Mrs. Opdyke was doing.

Polly, reassured now by the presence of both parents, was alert and quite ready to chatter with Bobbie about the tragedy.

But Mrs. Opdyke banned that at once and forbade Polly to speak at all.

The doctor and Cale Harrison were in the Tapestry Room with the dead man, but the other two men had drifted out to the hall.

These two, Dare and Bingham, were silent.

Though in no way enemies, they were not congenial spirits, and neither cared to discuss the case with the other.

Ted Bingham was nervous and walked about lighting a cigarette and then throwing it aside, sitting down a moment, then suddenly jumping up, going out to the dining-room for a glass of water, and then coming back without it.

Rollin Dare watched him, his own big frame comfortably ensconced in a high-backed hall chair.

“Do sit down, Bingham,” he said, at last. “Or at least stand still. You make me jumpy.”

“Who isn’t jumpy? Do you realize what has happened?”

“Of course I do. But we can’t do anything. Why roll around so?”

Bingham vouchsafed no answer but turned off and entered the Tapestry Room.

Here Dr. Opdyke and Cale Harrison were holding a desultory conversation.

“It’s unthinkable,” the doctor was saying.

“Yes,” Harrison agreed.

He was one of those men who would agree to almost anything. It was this trait that had endeared him to Gaylord Homer.

“Come in, Bingham,” Dr. Opdyke said, looking up. “What do you make of it all? Mr. Harrison says there was no one in this room but Gaylord and two girls.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” Ted Bingham returned. “Where were all the others?”

“Where were you?”

“Me? Why—I was standing in that doorway, between this room and the lounge.”

“You were there when the lights went out?”

“Why, yes—I think so. Yes I was.”

“And you stayed there through the dark time?”

“Sure. But—are you questioning me?”

“Not at all. I’ll leave all that to the police.”

“You’d better. Excuse me, I don’t mean to advise, but I know that an official investigation is the one that counts. He—he couldn’t have done it himself?”

“Hardly.” The doctor gave a grim smile. “The dagger was driven in by a strong, quick stroke. It entered between the seventh and eighth ribs, and death was probably painless and almost instantaneous.”

“I see. The murderer then had a knowledge of anatomy.”

“Well, that wouldn’t be really necessary. Anybody with the will to kill would strike about like that. The dagger blade is horizontal, you see.”

“Don’t ask me to look at it—I can’t!” Ted walked away from the tragic sight and fingered some books that lay on a table.

“Perhaps it would be better if you didn’t touch anything, Mr. Bingham,” murmured Harrison, in his deprecatory way.

“Don’t tell me what to do!” Bingham flung back at him, and leaving the room he went to where the girls were.

He sat down beside Diana, who paid no attention to him. She seemed like one in a trance, her blue eyes looked glassy, and her pale face showed all too clearly the remaining dabs of rouge.

From her couch Marita was eying Diana attentively. Her face showed all her worst characteristics, hate, rage, jealousy—all gleamed from her great dark eyes and were shown in the straight line of her red lips.

Yet no one spoke. Perhaps it was because of the restraining presence of Mrs. Opdyke, perhaps the girls were all too overcome with the shock of the tragedy, but Bingham found himself in a silence that was more embarrassing than their first excitement had been.

At last the police arrived. There was the village constable, and a detective sergeant in plain clothes.

The latter took charge of affairs. No longer need Dr. Opdyke wonder who was at the head of things. Sergeant Cram was. He took hold with a force and decision that left no room or place for any one else.

He strode into the Tapestry Room, followed by the far less self-assertive constable. He walked once round the love-seat, viewing the body from all angles.

Then he said, rapping the words out; “Who did it?”

As no reply was forthcoming, Dr. Opdyke said, quietly. “We don’t know that, sergeant. It is yet to be discovered.”

“Who was in the room with him?”

It had come. The vital question, the significant query.

The question that had but one answer, that led to but one result.

“I—I wasn’t here,” the doctor begged the question. “I was called in after Mr. Homer was dead. I live next door.”

“Well, who was here? Who are you, sir?”

It was Cale he turned to, and the secretary replied at once.

“I am Harrison, the confidential secretary of Mr. Homer.”

“Where were you when Mr. Homer was killed?”

“I was upstairs. I went up to the study directly we left the dinner table, and only a few moments later, I heard a commotion down here and I heard a woman scream. I ran down and found Mr. Homer stabbed to death.”

“How did you know he was dead?”

“I—I didn’t—then, but when he was so still—and didn’t move and all——”

“Did anybody say he was dead—before the doctor came, I mean?”

“I don’t know—I really don’t know exactly what did happen or what anybody said. I was sort of—sort of dazed, you know.”

“You’re sort of dazed yet. Pull yourself together, you’ll have a lot of talking to do. Now, tell me, someone, who was in this room with Mr. Homer when he was killed?”

“Mr. Bingham was in that doorway,” offered Dare, pointing to the arched door where Ted had stood.

“Hold on! Did this stabbing occur when the lights went off? The dark time?”

“Yes,” Cale said, “I thought you knew that.”

“I didn’t. I knew nothing about it. How do you know?”

“Only because just after the lights came on again, I heard a shriek and a commotion down here.”

“Well, that fixes the time, doesn’t it, Gorman?” He turned to his fellow policeman for the first time since his entrance.

“Yes, no question about that. You’d better talk to somebody who wasn’t next door or upstairs when the thing happened.”

His dry tone seemed to nettle the sergeant a little, but he agreed.

“Call that man Bingham,” he directed.

In his cautious way, Harrison stepped to the door of the lounge and summoned Ted.

Unwillingly he came, his face as black as a thunder cloud, his lips twitching and his whole aspect belligerent.

“What do you want?” he said, not rudely, but with a decided lack of cordiality.

“You,” said Cram, tersely. “Murder has been committed here, and we want to get the detailed particulars at once.”

“Sorry, but I can’t tell you anything.”

“You can tell me where you were at the time.”

“Oh that. Yes, I was standing in that doorway.”

“Why were you there?”

Ted stared at him, and then said quietly: “For no especial reason. We had all just come in from the dining-room, and we scattered through the house. I paused in the doorway to see where others were going to settle down.”

“And Mr. Homer came into this room directly he left the dining-room?”

“Yes—I think so. I wasn’t noticing, you understand.”

“Did you leave the dining-room after Mr. Homer?”

“Yes, right behind him.”

“Then you couldn’t help seeing where he went. He came right in here?”

“Guess he did.”

“Who was with him?”

There it was, the awful question! But Ted Bingham had no intention of answering it.

“I don’t remember,” he said, mendaciously. “We all crowded through the hall together. Gaylord turned into this room, and a lot of us went on to the lounge. I think Harrison went upstairs.”

“He did. He went up to Mr. Homer’s study to do some work.”

“Oh, was that it? Well, I can only speak for myself. I don’t know about the others.”

“But Mr. Bingham, when you stood in that doorway, just before the lights went out, you surely saw who was in this room with Mr. Homer.”

“No,” Ted looked his inquisitor squarely in the eye, “I was looking the other way.”

“Oh, toward the lounge. Well, then, who was in the lounge?”

“Most of the crowd. Mrs. Abbott, Miss Opdyke—I don’t think I can enumerate them, really.”

“Never mind, I’ll learn all this from the others.”

With that Sergeant Cram went into the lounge, leaving the constable and the doctor alone with the dead man.

Bingham and the secretary he herded before him, seeming desirous for their presence.

The lounge was a large and imposing room. Of noble proportions and with a lofty ceiling it was a fit setting for the treasures of furniture and ornament therein gathered.

Paneled in polished gumwood, the walls gave back reflections of the soft light of a myriad candles, and the darker recesses and alcoves added to the picturesqueness of the scene.

Unheeding the aesthetic effect, Cram looked about for a light-switch and found one. A flood of light followed, and brought into bold relief the faces that had willingly sought the more welcome dusk.

“Ah, that’s better,” said Cram, as he turned on another switch. “Now, if you please, I want a straightforward and coherent story of what happened here tonight.”

Though he had expressed his wishes clearly enough, nobody seemed inclined to grant them.

The silence grew oppressive, and at last Cram said:

“The fact that it is so hard to elicit testimony is a bit suspicious in itself. I find I must interrogate you individually.”

There was a slight rustle of indignation at this, but Cram paid no attention to it, and addressed Rollin Dare.

“I have already had a few words with Mr. Harrison and Mr. Bingham,” he said, in a grave but not unkindly voice, “and now, Mr. Dare, I will ask you to tell me all you can as to the actual happenings when the lights went off.”

“Me,” exclaimed Dare. “I don’t know anything about it.”

“Where were you?”

“Over in that far corner of the lounge, over by the big Oriental urn.”

“Who was with you?”

Dare paused a moment, and then said, firmly, “Mrs. Abbott was with me.”

“You verify that, Mrs. Abbott?” asked Cram, turning to her.

“Yes, of course. We were sitting on the divan there, smoking.”

“All the time the lights were off?”

“Yes, all the time,” said Dare.

“And please describe what happened when the lights came on again.”

Rollin Dare had no thought in his mind but to tell the exact truth as far as he knew it. A straightforward sort, he almost always spoke the truth.

He was a short, stocky man, physically, with a round, pleasant face and mirror-like black hair. He was always positive, though also given to changing his mind. His worst trait was that he was a bit of a sponge, often coming down on his friends for entertainment, favors, and even financial aid now and then.

Yet his gay good nature, and his readiness to help at any time kept him a favorite and caused his faults to be forgotten.

He was not a far-sighted chap, and now, put to it for a description of a scene, he thought only of being exact about it.

“Why, let me see,” he said, thinking back. “We sat there on the divan, Mrs. Abbott and I, and it was dark, and I was thinking as soon as the lights came on I would ask Homer to let us have a dance. Then the lights did come on, just as they always do, you know, and I reached out for a cigarette and gave one to Mrs. Abbott. I was just lighting hers for her, when there came a scream, a girl’s scream from the Tapestry Room.”

“How did you know it was from that room?”

“Why—er—I dunno as I did know at the time—not for sure. But it sounded from that direction, and when we jumped up and went that way—everybody was going that way, why, we could see that was where the scream came from.”

“Yes, and how could you see that?”

“Why, Marita—Miss Moore, you know—had fallen to the floor, and I guess she was the one who had screamed. Though I’m not sure of that.”

“Was it you who screamed, Miss Moore?” Cram whirled round toward her.

“Yes, it was,” Marita said, in a low voice, but speaking steadily.

“Why did you scream?”

“Because, when the lights came on, I saw—I saw Gaylord, with a—a dagger sticking in his back.”

“And you screamed from fright?”

Marita’s great eyes gave one glance round the room, and then came to rest on the countenance of the detective.

“Yes,” she said, slowly, “yes, from fright, and terror and grief.”

“You didn’t know then that Mr. Homer was dead.”

“I surmised it. The way he looked, the way he was huddled down, the way that terrible dagger stuck out—oh, oh,—hush! Don’t ask me any more!”

Marita gave way to an unrestrained sobbing, and Mrs. Opdyke went quickly to her side, hoping to calm her.

Cram turned at once to Diana, and said, with a sort of intuition. “Were you in that room, too, the Tapestry Room?”

The girl had been looking pale and distressed, but this question seemed to break down her final barriers. She collapsed, her head drooped forward in her hands, and she seemed unable to speak.

“Let her alone,” stormed Ted Bingham. “Don’t you see she is ill—she is almost distracted.”

“I am sorry,” Cram said, “but this inquiry must go on. It is imperative. Perhaps Miss Kittredge will answer this one question. Were you in that room with Mr. Homer when the lights went off?”

Diana nodded an assent, and the detective mercifully let her alone.

He turned to Bingham.

“Mr. Bingham,” he said, “I must ask you to answer me carefully. When you stood in the doorway, and the electric lights went dark, were you standing there alone?”

“I was,” Ted replied.

“When the lights came on again, were you still standing there alone?”

“Yes, I was.”

“Who was then in the Tapestry Room with Mr. Homer?”

For a moment Ted hesitated, and then the eye of his inquisitor being firmly fixed on him, he said, slowly:

“Miss Moore was in there and Miss Kittredge, too.”

“Then you must have turned round, Mr. Bingham. You have already told me that you were facing the lounge and couldn’t see into the other room.”

“Yes—I—I suppose I did turn around.”

“And you saw the two ladies there, when the light returned. What were they doing?”

“Nothing, that I noticed. Miss Moore had fallen to the floor, and naturally I hastened to help her up.”

“You had heard Miss Moore scream?”

“Yes.”

“You were then not surprised to find she had fallen?”

“I heard her fall—I mean I heard a sound as if someone had fallen. I think that was when I turned that way.”

“But Miss Moore didn’t scream until after the lights came on.”

“Didn’t she? I’m a bit confused. The shock of it all has dazed my memory a bit. I’ve told you all I know.”

THE arrival of the coroner called the detective away from the lounge and he was closeted for a time, with Coroner Hale and Dr. Opdyke in the Tapestry Room.

The silent constable sat in the hall, where he was glowered at by Wood, and by any of the servants who chanced to pass.

Few did, however, for Abbie Perkins had rounded up the staff and given them orders to remain in the kitchen department unless by her express directions.

Wood, the butler, of course, was not under Abbie’s law, and he drifted about like a lost sheep.

Relieved of the presence of the terrifying detective, the groups of the lounge began to chatter a little.

“Bumptious old bounder,” remarked Dare. “I suppose the police people have to put on that God-almighty attitude to hold up their end. But if he’d just ask his necessary questions in a decent, straightforward way, he’d get better results.”

“I can’t see that he was rude or unmannerly,” said Harrison, in his low, timid voice. “It’s his business to get at the truth of the matter.”

“Well, the truth of the matter doesn’t concern any of us. We didn’t stab old Gaylord. We ought to be deferred to as guests who are shocked and grieved at the disaster. Instead of which he seems positively suspicious of us.”

“Oh, no, Rollin,” cried Bobbie Abbott. “You can’t think he suspects any of us being implicated in the—the affair! Oh, I wish Roger was here! I wish I hadn’t come! I wish——”

She broke down and sobbed so alarmingly that Mrs. Opdyke left her post by the side of Marita and went over to the new demand on her ministrations.

Abbie Perkins stalked into the room. She paused just inside the threshold, and stood, hands on hips, surveying the group.

“I been a-lissenin’ at the doctors,” she said, unblushingly, “and I heard the coroner one say as he’d have the inquest tomorrow and everybody must stay over for it. ’Course most o’ you folks planned to stay two-three days anyhow. Mis’ Opdyke, what about you? And Polly? I want for to set out the bedrooms.”

“Oh, I think we’ll be allowed to go home, Abbie. Only next door, you know.”

“Yes’m, I know. But that coroner one, he said everybody.”

“He’ll let us know soon, I think,” and Emily Opdyke turned back to the now hysterical Bobbie.

“Brace up, Bobs,” said Ted Bingham, coming toward her and speaking gently. “There’s nothing to be afraid of. It’s a ghastly thing to happen, but it’s up to all of us to put up a brave front and carry on as best we can. Once the inquest is over, you can go home. Somebody will come to fetch you, eh?”

“Yes, Ted, somebody will come for me. Roger expects to be away a week, but I’ll send for Jimmy or Dad.”

Bingham passed on and came to anchor next to Diana.

He sat down beside her without a word. By no word or look did she acknowledge his presence, but glancing at her sidewise he saw or imagined he saw a slight look of relief on her face.

Pale as a waxen image, silent as a marble statue, Diana sat looking off into space, her sky-blue eyes vacant and devoid of all expression. A sudden tremor shook her whole frame, and Bingham dared to put out his hand and clasp hers. She gave him an answering pressure, so slight he could scarce notice it, but unmistakable.

“Do you want to leave the room—with me?” he whispered. “Go outside for a stroll?”

“I daren’t,” she murmured back. “That terrible man will return and he’ll want to bully me.”

“Nobody shall bully you, Diana, not while I’m here.”

“You can’t do anything to help, Ted. Or, yes, you do help, just by your presence. Stand by, won’t you?”

“You bet!” he responded emphatically, and then the men came in from the Tapestry Room.

Coroner Hale addressed the waiting crowd.

“Mr. Homer has been murdered,” he said, quietly. “He has been stabbed in the back with a jeweled dagger, one of his own belongings, I am told. The blade reached his heart and death was practically instantaneous. The probability is that the victim made no sound and almost no movement after that attack. Did anyone near him hear any sound from him?”

There was no response to this, and the coroner proceeded.

Hale was a tall, spare man, with sharp features and darting black eyes. He was evidently informed as to the known facts of the tragedy, and he looked piercingly at Diana and also at Marita as he talked.

Getting no reply to his question, he went on in curt, incisive sentences.

“Mr. Homer was sitting at the time, sitting on a small sofa. The lights went off, as they do every night, and in the few moments of darkness someone procured the dagger from the small table where, I am told, it is accustomed to lie and, in the darkness or semi-darkness, drove the blade into the victim. I must now make some pointed inquiries. Who was in the room with Mr. Homer when the electric lights went out?”

The silence that followed this question was for a full minute unbroken.

Hale looked from one to another, noting the expressions on the various faces. Sergeant Cram also scrutinized the faces of the party. Diana still preserved her icy calm, and Marita’s face was hidden in her hands.

“I may as well state,” Coroner Hale said, not unkindly, “that it will in no way help anyone to try to hide or evade the truth. It is, of course, known who was in that room, but for your own sake, I ask you to speak out and tell any facts bearing on the case.”

“I was in the room,” Diana said, then, “I was standing near the sofa on which Mr. Homer was sitting. But I know no facts bearing on the case.”

She spoke with perfect calm and a quiet dignity that commanded the respect of all present.

“I was in the room, too!” Marita exclaimed. Her voice was jerky, her manner excited, indeed, she gave the effect of speaking because Diana had spoken, “I was near the sofa, too, at Mr. Homer’s other side.”

“And can you tell me anything more?” asked Hale.

“No; what is there to tell? We three were there, the lights went out. When the lights came on again, we saw Gaylord——”

“Were you standing, Miss Moore?”

“N—no. I was—sitting on the arm of the sofa.”

“Talking to Mr. Homer?”

“I—I don’t know. I mean I don’t know whether I was talking or not, when the lights went off.”

“You were not,” Diana said; “Mr. Homer was talking to me.”

“Oh, he was,” put in Hale. “What was he talking about?”

“He was asking me if I would rather dance or go for a stroll in the garden.”

“And you replied?”

“I hadn’t replied at all. Just then the darkness came. We are accustomed to it, we often don’t notice it, but tonight, for some reason, it made us all silent.”

“In the silence, then, you could of course hear if another person entered the room. Did you hear any such sound—any sound?”

Diana hesitated. Her calm face gave no hint of what was passing in her mind save that her lips quivered a little.

At last she replied, with a murmured “No” so low-voiced that it could scarcely be heard at all.

Hale turned quickly to Marita.

“Did you, Miss Moore?” he said.

“I?—Me?—Why, no—no, indeed, I heard nothing.”

“Yet in a silence, a two minute or more silence, a man was stabbed, killed, and you two, only a few inches from him, heard no sound?”

Marita, who was lying on a couch, nestled in a dozen pillows, sprang to an upright attitude.

“I didn’t say I heard no sound,” she exclaimed. “There were lots of sounds, I heard a clock ticking, I heard low laughter and chatter from the lounge, I heard Mr. Harrison walk across the hall, I heard the parrot squawk in the dining-room, I heard—well, there were many confused sounds.”

“But did you hear any sound that you would judge made by Mr. Homer?”

“No,” and Marita turned white and shivered.

“Did you, Miss Kittredge?”

“No,” said Diana, as pale as Marita, but keeping her poise.

“Did either of you,” Hale was very grave now, “did either of you hear any sound that might have been made by some intruder, by someone who came into the room for the purpose of crime?”

“I didn’t,” answered Marita, for Hale looked toward her. “But by that I mean I didn’t knowingly hear any such sound. There may have been such, however, for as I said, there were various vague and unidentifiable sounds.”

Hale looked at her in slight surprise. From a decidedly hysterical attitude she had roused herself to coherent talking and to definite description.

“You heard no such indications, Miss Kittredge?”

“I did not. But I heard nothing. That is, I do not remember hearing the clock tick or the parrot cry out.”

“What were you thinking about? Having no intimation of the impending tragedy, what was occupying your thoughts at the dark time?”

A look of desperate fear came into the blue eyes.

It was evident that now Diana had all she could do to keep her poise, to retain her calm.

But she struggled bravely with herself, and at last stammered out:

“I cannot tell you what I was thinking about, for I do not remember. Merely the trivial thoughts of the day.”

“How far were you from Mr. Homer at that time?”

“How far? Why, I don’t know. Perhaps a yard or so.”

“Oh, no, Diana,” Marita broke in, “you were not more than a foot from the couch Gaylord sat on. And you were coming toward it, you were about to sit down beside him.”

“No, Marita, no, I was not. I meant to leave the room.”

“Why?” asked Hale.

“For no especial reason,” Diana returned, naughtily now. “I merely thought I would go into the lounge.”

“And then dark came. You expected the dark?”

“Oh, yes. It always occurred about ten o’clock. But I never know the exact time.”

“You did tonight,” Marita said, “because I had just told you it was five past ten. Don’t you remember?”

“Yes, I believe you had,” Diana said, wearily. “I can’t see that it matters.”

“Mr. Bingham,” Hale turned to Ted, “will you tell me exactly, as to the attitudes of the two ladies in the room with Mr. Homer. You were in the deep alcoved doorway that leads from that room to this.”

“Attitudes?” said Bingham. “I don’t understand.”

“Yes, attitudes. Miss Moore, I am told, was sitting on the arm of the sofa. Was she at Mr. Homer’s right or left side?”

“Why—let me see—the left, I think.”

“Yes, I was on his left,” Marita cried out. “Why not ask me?”

“Were you touching him?”

“When the dark came I had my hand on his shoulder, but as the light went out I took my hand away, and——”

“And jumped up from where you were sitting.”

“Yes—I believe I did.”

“And—I’m speaking to you, Mr. Bingham,—Miss Kittredge was on the right of Mr. Homer?”

“Yes, she was,” Ted asserted. “About four or five feet away.”

“But you had your back to them all, how do you know?”

This was from Sergeant Cram, and Ted thought to himself with what pleasure he could wring the detective’s neck.

“I know, because I saw Miss Kittredge when the lights came on again.”

“And at that time, Miss Moore had fallen to the floor?”

“Yes,” said Ted, curtly.

“It is not my duty,” Hale went on, in his harsh, rasping tones, “to investigate the possibilities of this case, as to the identity of the murderer. That belongs in the jurisdiction of my colleague, Mr. Cram. It is for me to determine the method of the death, and that has been done. I shall have an inquest tomorrow afternoon, and it is necessary that you all remain here until after that time. Dr. and Mrs. Opdyke and their daughter will be permitted to go to their home, next door. The rest of you must remain until excused. The situation is a bit difficult, in that there seems to be no real head of the house. In his position of confidential secretary Mr. Harrison is, in a way, in authority. Who, Mr. Harrison, is Mr. Homer’s heir or his next of kin?”

“His next of kin, I think, is a second cousin, who lives in New York City. But as to his heir, I happen to know that Mr. Homer made a new will within the past week, and while I do not know its contents, I do know it is the only will he ever made, for he told me so.”

“That is of interest, and must be looked into. Who is Mr. Homer’s lawyer?”

“Mr. Crawford. Edgar Crawford of New York City. But he didn’t draw up the will.”

“And who is the cousin in the city? What is his name?”

“Moffatt. His first name is either Alfred or Albert, I’m not sure which.”

“Can you find out? Mr. Moffatt should be notified at once of his cousin’s death.”

“Yes, I can get his address from Mr. Homer’s address book.”

“Get it now, then. I think it only right to tell him the news tonight.”

“It is nearly midnight.”

“Yes. Get me the address, please.”

Harrison obeyed, and quickly finding the address and telephone number, Hale passed the book over to Sergeant Cram and asked him to call up Mr. Moffatt.

“Call in the butler and housekeeper,” Hale then directed, and Wood and Abbie Perkins appeared.

Hale addressed the butler first.

“Did you see any stranger or idler about the place today?” he asked.

“No, sir,” Wood replied. “No one at all who didn’t belong here.”

“Have you noticed any unusual behavior on the part of Mr. Homer the last few days?”

“No, sir. Except that he was a bit excited like, getting up this party. He looked forward to it, I can tell you.”

“Why?”

“Well, it was his birthday party; that is, Sunday would be his birthday and there was to be extra doin’s. And besides——”

“Well, man, go on.”

“Besides, he always liked company and he looked forward to a good time.”

“That is not what you started to say. Why did you change your mind?”

“I didn’t change my mind, sir. I know nothing more of the matter than I’ve told you.”

“Neither he doesn’t,” broke in Abbie Perkins. “Wood is as honest as the day is long, and if he knew anything else he’d tell it.”

“What do you know? Anything else?”

“No, that I don’t. Only I can’t help seein’ what’s right under my nose, can I?”

“Well, what was right under your nose?”

“Oh, only that Mr. Homer hoped and prayed that when this party was over and done with, a certain lady would be his fiancée, that’s all.”

Mrs. Perkins bridled and smiled a little, evidently so full of her exclusive knowledge of her master’s affairs that she felt a great superiority.

“Yes, and who was the certain lady?”

But in the meantime, Abbie Perkins had received such a black look from Ted Bingham, that she collapsed like a burst balloon.

He added a most negative shake of his head and was altogether so forbidding of aspect that she dared not go on.

“I—I don’t know, sir,” she said, quickly calling out her reserves of diplomacy, “I don’t know who the lady was, but Mr. Homer had just sort of intimated, you see, that there was somebody.”

“I think you do know the lady’s name.”

“No, sir, cross my heart, I don’t! But what does it matter now? And the poor man dead and all!”

Just then Cram returned, saying he had talked with Mr. Moffatt.

“What did he say?” asked Hale.

“He was in bed, asleep, and it took me a few minutes to get him awake enough to understand what I was talking about. Then he seemed shocked of course, and asked what we wanted of him. I told him he ought to come up here, and he said he would come tomorrow, then added, that if necessary, he would come tonight. He began to get onto the true inwardness of the matter at last.”

“You told him it was murder?”

“Of course, and while he was properly astounded he really showed little deep feeling. He said, again, ‘Want I should come up there tonight?’ But I said tomorrow would do, for he couldn’t get here under an hour or more, and I take it we’re about through for tonight.”

“Yes, I think so. Better call an undertaker and have the body taken upstairs tonight. If Moffatt is the heir, I’d like to have him here as soon as possible, but no use delaying things for his arrival. And your work, Cram, can be in no way assisted by keeping the dead man down here.”

“No, there’s no doubt about the method and the cause of death. I’ll take charge of the dagger, it’s a valuable piece of property, I’m told.”

“Yes,” Dr. Opdyke told them, “it is a rare and valuable curio. It is a gold and jeweled weapon that was said to be used in the play of Othello, when given by Booth and Barrett. A fine piece of workmanship, aside from its associations.”

“Where was it kept?”

“I don’t know, where was it, Abbie?”

“Always on the small table in the Tapestry Room. The table behind where Mr. Homer was sitting when—when——”

Her feelings overcame her, and she ran from the room.

“Let her go,” said Hale, “we can’t do anything more tonight. Ladies and gentlemen,” he nodded at the crowd, “you are all dismissed for the night. Of course you are not under arrest or even detained, but you must stay in this house or grounds until you are given permission to leave. A dastardly crime has been committed, and the perpetrator must be brought to justice. Anyone who can do so must testify to any facts they know of. To withhold such testimony makes you an accessory and as liable to punishment as the principal.”

The coroner left the room and could be heard in the Tapestry Room, talking in low tones with the undertaker who had recently come in.

“Come out for a breath of air,” Ted Bingham begged of Diana.

But she only looked at him with cold eyes and said she must go to her room at once.

Harrison cast longing eyes at Marita, but dared not cross the room to speak to her. Timid always, he was more embarrassed than ever now with the cloud of tragedy and crime hanging over the house, with the police giving furtive glances now and again toward the beautiful and defiant looking girl he adored.

He tried hard, did Harrison, to go to her side, but his weak will and weaker muscles refused to act for him.

Rollin Dare was not so timid. He went up to Marita, where she still reclined among her pillows and said, cheerily:

“Come on, Rita, come for a sprint through the gardens. It will make you feel a whole lot better.”

But after a moment of hesitation, Marita said no, she wanted to go to her room.

“But,” she added, with her own gay smile, “I’ll go with you tomorrow morning. I’ll be better then.”

“All right,” Dare returned, “good-night, then. Come along, Bobbie I’ve got to get some fresh air, and I hate to walk alone.”

Bobbie Abbott consented, and catching up a light wrap, went with him out to the garden.

Dare was not surprised, though it scared Bobbie, to find the whole place patrolled by policemen.

“Don’t be afraid,” he whispered to her, as he pleasantly greeted the guards. “Good-night, officer, we’re just walking around a bit.”

But at last they managed to find an arbor out of earshot of the patrolmen, and Bobbie burst forth:

“Oh, Rollin, tell me, do! Was it Marita?”

“No, of course not! Hush, don’t say such things! Keep quiet, Bobbie.”

“Then it must have been Diana! It had to be one of them! You know it had to!”

“We don’t know anything of the sort. And if we do, we mustn’t breathe it.”

“Why not? The truth has got to come out. Oh, Rollin, which one did it?”

“Listen here, Bobbie. I tell you you mustn’t talk like that. Don’t you see what a dreadful thing you’re doing to accuse either of those girls?”

“But it had to be one of them. They were in there alone with Gaylord.”

“No matter if they were, you must not mention their names as possible suspects. If you do, you may get into deep trouble yourself.”

“Why? How? What do you mean?”

But Dare refused to tell what he meant and forbade her to continue the subject.

WHEN Sergeant Cram arrived at Twin Towers the next morning, he was met by Bingham, who asked him to join him in a conference in the study on the second floor, where Homer’s business matters were always attended to.

“You’ve had breakfast?” asked the detective, as they went up the stairs.

“Oh, yes, I was up early.” He ushered Cram into a pleasant room, where Cale Harrison sat at his desk.

Another and more elaborate desk was obviously the dead man’s, and at this Bingham sat down, after offering Cram a near-by chair.

“I have decided,” Bingham said, “to take the helm myself. I don’t mean in any officious or presumptuous way, but I feel somebody should take charge and as Gaylord Homer’s near friend and chum, I think I am the one to do so. For the moment, at least. When it transpires that there is an executor or an inheritor, I will turn over to him a full report of all I have done and all the responsibilities I have incurred. But in the absence of such an authority, I feel myself justified in keeping an eye on developments as they occur.”

Cram looked at the speaker a little dubiously, but said nothing.

“The lawyer, Mr. Crawford, will come here this morning, and he may give us such information as will excuse me from any further duty. But until that occurs I propose to take charge.”

“I can see no objection to your plan, Mr. Bingham. I assume Mr. Harrison also agrees to it?”

“Yes—oh, yes,” said Cale Harrison, earnestly. “I am merely a secretary, and I would wish for someone to whom I may report. I shall continue to do my work as usual, until I receive other orders from someone in a position to give them.”

“This is the office of the late Mr. Homer?” asked Cram, looking about the room.

It was directly above the Tapestry Room on the first floor, and though equipped with office furniture, with desks and filing cabinets and a good-sized safe, the pieces were all evidently made to order of choice woods and were of fine workmanship. Also there were valuable pictures and lamps, and the desk fittings were of the finest variety. Those on Homer’s desk were of carved jade, while Harrison’s were of beautiful bronze work.

“Yes, it is the office,” answered Harrison, “though always called the study. But all business matters are looked after here. Mr. Homer was methodical and systematic in his business. You will find his papers and accounts in perfect order, I am sure.”

“Doubtless, oh, yes, doubtless,” said Cram. “Of course, the papers must be gone through, but it will be well to wait for the lawyer’s arrival.”

“I think so,” agreed Bingham. “Now, Mr. Cram, what we want to talk over, Harrison and I, is the—er—the crime itself. Are you willing to say what you think as to—as to the identity of the criminal?”

“You put a difficult question, Mr. Bingham.”

“But you saw the whole affair, that is, as much as anybody could see, what do you think?”

“I have a very decided opinion, and it is that the murderer is someone who came in from outside, and who——”

“There is an old proverb, Mr. Bingham, about the wish being father to the thought. May I suggest, that you strongly hope that the murderer did come in from outside, and that is the ground for your opinion?”

The color flew to Ted’s cheeks and brow, and the sympathetic Harrison also looked embarrassed and distressed.

“I have other grounds,” Ted said, struggling to retain his composure, “I know perfectly well that no one in our party of friends here could have done such a thing. I know the servants are beyond suspicion. Therefore the doctrine of elimination points beyond doubt to an outsider.”

“Elimination is a fine thing,” Cram returned, “but your knowledge and belief is not sufficient to eliminate the people in the house.”

“You don’t mean you suspect any of us!” exclaimed Harrison, in his scared way. “You can’t, it’s impossible!”

“Mr. Harrison, that has yet to be determined. I am quite ready to admit we have a deep problem before us, but it cannot be solved by surmise or suspicion, nor yet by belief and faith. We must have evidence and testimony. They must be sifted and proved. Reliable and trustworthy witnesses must be heard and their stories listened to with care. It is too soon to point the finger of suspicion at anybody. Even if circumstances seem adverse, there may be extenuating conditions, there may be misleading facts. So, I cannot hazard an opinion at present as to the identity of the criminal, but at the inquest this afternoon, there may be facts brought forward and evidence given that will be significant if not decisive. Now, since we are here, I will put a question or two myself. Mr. Harrison, you mentioned a will of Mr. Homer’s but you said it was not drawn up by his lawyer. Will you tell me further of that?”

“Why—it was this way. Although conventional and of normal habits in most ways, Mr. Homer sometimes broke loose and became a law unto himself. In the matter of a will he did so. He had never made a will, but when he did conclude he wanted one he made it himself. He bought a book entitled, ‘Make Your Own Will,’ and he read it thoroughly and then made his own will.”

“Where is that will?”

“I don’t know, but I think it is in the book. You see, the book had a pocket in the back cover, and that pocket held a blank will. I mean a will with the preliminary matter already printed, and then various blanks for any legacies the testator desired to record. Mr. Homer showed me the book and the blank will when he bought it, and since then I have often seen him poring over the book.”

“In this room?”

“Sometimes. But more often as he sat down in the Tapestry Room. He always sat there after dinner for a time, and he kept the will book down there.”

“On the bookshelves?”

“Usually on the table, or carting it round in his pocket.”

“The will must of course be found. Do you know the gist of its contents?”

“I’d rather not say.”

“All right, it doesn’t matter. The book will, of course, turn up.”

“Oh, yes. It will be found among his things somewhere.”

“Mr. Homer was a rich man?”

“I—really, sir, I couldn’t say. Mr. Crawford will tell you all such details. I’m only a secretary, you see, and I hesitate to make statements.”

Cram thought to himself that Harrison hesitated to do almost anything at all, but he asked him no further questions at the time.

“I can tell you that,” broke in Bingham. “I see no harm in saying that Gaylord Homer was a rich man. He inherited a pile from his father, and he has judiciously invested it until it has about doubled itself. I know this from what he has told me himself. Never a braggart, he has often expressed a satisfaction that he had the wherewithal to gratify his tastes for books and art objects.”

“And do you know who was to be the beneficiary under his will?”

“I do not. I didn’t know he had made a will, until Harrison told of it. I often said to Gaylord that he ought to make one, but he only laughed and said he was good for many years yet.”

“Then he had no apprehensions, no fears of any enemy coming in to do him harm?”

“Not that I know of. Yet who can tell about his friends? Homer was not one to babble, and for all I know he may have had a dozen enemies who wanted to kill him.”

“You’re a bit transparent, Mr. Bingham.” Cram smiled a little. “You don’t want any of your friends in the house suspected, so you invent these enemies.”

“Not quite fair, Mr. Cram,” said Harrison, his voice steady enough, but his fingers twitching nervously. “Of course, none of us wants suspicion to rest on anyone in the household, if there is an enemy outside who may have done this thing.”

“That’s natural enough,” said Cram, quietly, “but I’m going downstairs now, and before I go, I want to advise you two men not to talk the matter over too much with the others. It’s wiser to keep your own counsel for the present.”

“Old fossil!” exclaimed Ted, as the detective disappeared downstairs. “He’s mid-Victorian! I’d like to get an up-and-coming detective who could ferret out some unknown enemy of Gaylord’s who sneaked in and killed him.”

“So should I,” and Harrison glanced furtively at Bingham. “But, you must realize, Mr. Bingham, there was no way an outsider could get in.”

“Why not?”

“Because we were all in the hall or lounge or Tapestry Room when the lights went out. No outsider could have come in a dark house and made his way to the Tapestry Room in the dark and committed the murder in the dark and got out again, in the dark, without being heard or seen by some of us.”

“I know it doesn’t seem likely, but, hang it all, Cale, it must have happened, for you know as well as I do that neither of those girls stabbed Gaylord!”

“Yes,” Harrison sighed, “I know it, but can we make the police believe it?”

“We must,” and Ted banged his hand down on the desk before him. “I’m going down and dog the footsteps of that Cram person. I shan’t let him put his rotten stuff over!”

Cale Harrison watched the other man as he swung out of the door and down the stairs.

The secretary was a personable man, fair-haired, blue-eyed and of good complexion. He was neither a prig nor a sissy, yet he lacked a firmness of speech which gave him the effect of lacking firmness of character. This was not the truth. Cale Harrison had a strong will and a quick, sane power of judgment. But his environment as a child had made him shy in manner and over-modest as to his own attainments.

Gaylord Homer had noticed this, and in his good-natured way had tried to uproot it.

“You haven’t a vice,” he had once said to Cale. “Now I don’t want you to cultivate wickedness, but take it from me, a chap too goody-goody can’t get along in these hectic days.”

The remark had settled into Cale’s mind, and he had thought it over many times. Although in some ways he had scorned Gaylord Homer, in other ways he had greatly admired him. For Harrison was a close observer, and he had long since come to the conclusion that a small portion of vice, of some wild sort, ought to be his.

Also, not being entirely above human curiosity, he was impatient to know what legacy his employer had left to him in that home-made will of his.

For a substantial sum had been promised, and Gaylord had worked hard over the precious document.

On an impulse, Harrison began to look through the drawers of Homer’s desk in an attempt to find the important will book and will.

Engrossed in this pursuit, he was startled at the entrance of Lawyer Crawford and Detective Sergeant Cram.

“Oh, oh,” Harrison said, “beg pardon come in, be seated.”

There was no reason for this embarrassment, for the secretary always had free access to his employer’s papers.

As always, his shyness brought about an air of bravado, of superciliousness, and he covered his confusion by an overdone carelessness.

“Oh, here you are,” he said, dropping the papers he held. “How are you, Mr. Crawford?”

Crawford responded duly and paid little attention to Harrison’s nervousness. For he knew the secretary well, but to Cram this flustered manner was peculiar, even suspicious.

“I was looking for Mr. Homer’s will,” Cale went on, “I don’t know where it is.”

“He never made any,” said Crawford, promptly.

And then Harrison had to tell him of the will book and the will that Gaylord Homer had drawn up for himself.

“Ridiculous!” the lawyer exclaimed. “There’s no sense in such a thing! Why shouldn’t I have drawn his will, as I attended to all his other legal business?”

“I don’t know, Mr. Crawford,” Harrison said, looking helplessly at him; “only I do know that is what Mr. Homer did, and the will must be around somewhere.”

“What were the terms of the will?” stormed the lawyer.

“I—I don’t know—exactly.”

“You know a lot about it, Harrison, and it is your duty to tell,” Cram informed him.

“Is it, Mr. Crawford?” asked the vacillating secretary.

“Yes, I think so. Though of course the will must be found. Who was the principal beneficiary?”

“A—a lady.”

“Who?”

“Miss—Miss Kittredge.”

The detective made a half articulate noise in his throat, which, however, was more intelligible than the “Ah,” of Lawyer Crawford.

While the three men in the study set up a determined search for the will, the lady who, as Harrison said, was the chief beneficiary, was taking part in what for lack of a more descriptive term may be called a scene.

Diana, with Marita and Bobbie Abbott, sat in the lounge, and though the conversation had at first been conventional and courteous, it was now becoming more and more personal.

Bobbie had brought about the climax when she said, “Of course neither of you girls could have done such a thing, but who did kill Gaylord?”

Marita’s temper, always inflammable, burst into flame at this, and she exclaimed:

“That’s the same as saying that either Diana or I must have done it! And I hereby declare that I didn’t do it.”

Though possessing plenty of self-control, Diana let it go to the winds at this speech.

“I must certainly declare also that I didn’t do it!” Diana said, in a cold cutting voice that somehow seemed to carry more weight than Marita’s hasty speech.

“Of course you did, Di,” Marita cried; “I didn’t, and there was no one else.”

“I think my statement must be believed before yours,” Diana said, slowly. “I am in the habit of speaking the truth.”

Her eloquent pause was more scathing than any denunciation could have been.

Marita flew into a fearful rage, and so wildly did she gesticulate and so madly pour forth her words that she was like a whirling dervish.

Frightened, Bobbie tried to catch Marita, to calm her, but the angry girl flew at Diana and attempted to strike her, screaming out anathemas in Spanish that were understandable only from their accompanying gestures.

Diana coolly grasped the outstretched hands, and said, contemptuously, “Don’t be a fool, Marita. Stop this nonsense!”

The clear, incisive tone, more than the words, checked Marita’s ebullition of wrath, and she cowered a little, though casting venomous glances at Diana.

“If you didn’t kill Gaylord,” Diana went on, “you’ll make everybody think you did by such actions. Now, behave yourself.”

This stirred up Marita afresh, and she was about to begin a new tirade, when Wood appeared at the doorway with a stranger.

“This is Mr. Moffatt, ladies,” Wood said, urbanely. “I will call Mr. Harris.”

The butler went upstairs, and Diana took charge of the situation.

“I am Miss Kittredge,” she said, with a touch of hauteur in her calm tones. “This is Mrs. Abbott and Miss Moore. I suppose you are Mr. Moffatt, the cousin of Gaylord Homer?”

“Yes,” he said, in a low, pleasant voice. “I was told of the—er—trouble last night, and I came as soon as I could this morning. May I—would you tell me some of the particulars? Was Gaylord still calm and perfectly composed?”

Diana answered him.

“Yes,” she said, “Gaylord was killed, stabbed to death. The police are in charge here and will, I dare say, see you at once.”

The visitor looked dazed, not only at the news given him, but, it was plain to be seen, at the manner of this beautiful but strange girl.

Marita was huddled on the couch, her face turned away from them, and her shoulders heaving with deep sobs and occasional moans.

Bobbie, still scared over the fuss between the two girls, was also interested in the stranger. It wouldn’t be Bobbie Abbott, if she were not interested in any man who came within her ken.

And this man looked attractive. His tall, gaunt form and lean, rugged face gave somewhat the effect of a modern Forty-niner, though his apparel was modish and his manner courteous and suave.

So Bobbie had to get into the game.

“The inquest will be this afternoon,” she vouchsafed, adding, “but I suppose you knew that.”

“No, I didn’t know it before Moffatt said. Will it be held here?”

“Why, yes, I suppose so,” Bobbie spoke uncertainly, but neither of the others volunteered any help.

And then the three men from upstairs came down, and Harrison stepped forward and greeted the visitor.

In his nervous, embarrassed way, he introduced the lawyer and the detective, and then, to his great relief, he was ignored and Mr. Moffatt became the center of attention.

“You are a cousin of the late Gaylord Homer?” Cram asked him.

“A second cousin,” was the reply. “Our fathers were cousins.”

“You were intimate friends?”

“No,” Moffatt said, settling back in his chair, “not intimate friends, but always friendly. I came here to see Gaylord once or twice a year, but our tastes varied widely and while we were not uncongenial, we had little in common. Also,” he smiled a little, “I am a proud man, and I was unwilling to seem as if I was sponging on my cousin for entertainment or hospitality.”

“I see,” said Cram, nodding his head. “And when did you see Mr. Homer last?”

“About two or three weeks ago, I was up here and staid over night. We had a pleasant visit, rather more so than usual, and Gaylord asked me to come again in the summer time, in July, he said. I promised to do so.”

“You live in New York?”

“Yes, in rooms in Thirty-eighth street. I have lived there for years.”

“Can you help us in any way? You see, Mr. Homer was stabbed by an unknown foe. Can you think of any enemy he had who would do such a thing?”

“No, I can’t. You see, I knew very few of Gaylord’s acquaintances and he knew few of mine. But he must have had a fierce enemy to do such a thing as that!”

“Indeed, yes. Do you know of other relatives he had?”

“I think I am the only one of his kin. I have heard him say so many times.”

“And do you know anything about his intended disposition of his property?”

“Not a thing. Some years ago, he said he would leave me a small bequest. But I never counted on it, partly because it is my habit never to count on anything until I get it, and partly because Gaylord was younger than I and would probably outlive me. Moreover, I am not in need. While not wealthy, my wants are simple and I can supply them myself. But I am overcome at the tragedy of his death. I want to do anything I can to help. I mean in tracking down the wretch who killed him and bringing him to justice. Please command me, Mr. Cram, and I will do anything I can to aid you.”

“Are you not in business?”