a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Ebony Bed Murder Author: Rufus Gillmore * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1800731h.html Language: English Date first posted: August 2018 Most recent update: August 2018 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Chapter 1. - Griffin Scott

Chapter 2. - A Female Henry VIII

Chapter 3. - Dorothy Vroom

Chapter 4. - An Inexorable Zealot

Chapter 5. - The Incredible Family

Chapter 6. - A Clew

Chapter 7. - A Babbling Brook

Chapter 8. - Gentler Methods

Chapter 9. - Detective Haff Telephones

Chapter 10. - The Torn Glove

Chapter 11. - A Catalogue of Husbands

Chapter 12. - Character Will Out

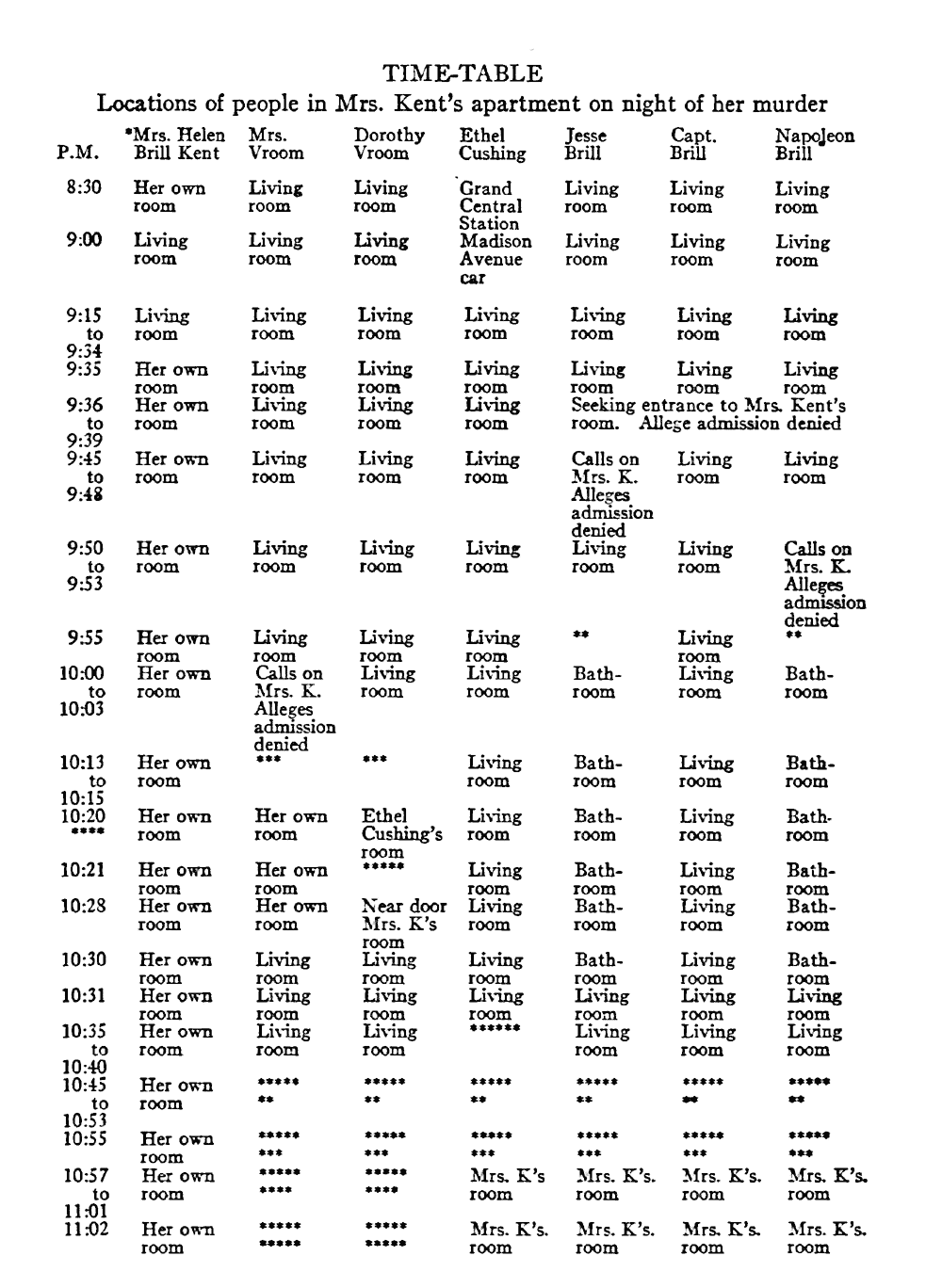

Chapter 13. - The Time-Table of a Murder

Chapter 14. - Mr. Edward St. Clair

Chapter 15. - A Good Sign

Chapter 16. - Horizontal Thought

Chapter 17. - The Modern Weapon

Chapter 18. - Dichlorethyl Sulphide

Chapter 19. - The Gorilla

Chapter 20. - Reeling in a Big One

Chapter 21. - The Battle

Chapter 22. - The Man Who Was There

Chapter 23. - A Second Weapon

Chapter 24. - The Noose

Chapter 25. - Ways and Ends

ON the night of the first shocking tragedy, I pushed the bell to Griffin Scott’s duplex apartment.

White-haired Wilson received me stiffly, but admitted me to Scott’s queer workshop. Scott got up, dashed towards me in a tart temper.

“I tried gently to suggest to you that I didn’t care to talk about the Lopez murder,” he said.

“Sorry. No one else knows the inside facts.”

Two nights before, I had finally located Griffin Scott here. He dodged all my questions, fascinated me into playing chess with him; while I was under his spell, he with neat questions learned all about me.

“I’ll make it plainer to you. You’re the first one to run me down here and I prefer my privacy.”

He stood, legs apart, his eyes bristling with such irritation that mine toured his odd workshop. Leather-upholstered settee and chairs by Sheraton. Books by foreign publishers of ungainly volumes. Refectory table by some tempted Italian monastery. But desk, files and other furniture, steel, and by Yawman & Erbe. The eager reaching-out-everywhere tastes of an advertising man—hard-boiled but a writer on the sky—of a star who had turned tracker of murderers, hunter of big game. Also an advertising star’s startling faculty for invention. From the ceiling, like settings in stage flies, dangled a Steinway baby grand, a carpenters’ bench and tool chest and a fully equipped chemical laboratory. He had but to push levers in a hall switchboard to transform this office into a study, into a workshop, into a laboratory. Wires and electric juice moved the furniture without the little exhibitions of bovine temperament of piano movers.

A doubt appeared to come over his manner from his irritated scrutiny of me. “Sit down,” he ordered. “You’ve discovered my real name, haven’t you?”

“Y-es,” I said after some doubt.

His wiry-looking average height settled down a little. Long nervous fingers slipped into cinnamon-colored hair frequently trimmed. Eyes a hard blue, deep set, always moving, and the clear-cut features of an advertising man grew suddenly thoughtful.

“That’s a wallop where it hurts. When I made my Gauguindive here, I kept my uptown apartment. Even my office doesn’t know this address.”

I began to squirm. “No one’ll ever get that out of me. Whether you make up your mind to come through on the Lopez murder or not, I’ll keep your secret.”

My eyes, or tone, or something seemed to bring him to me. Under dropped eyelids, he appeared for a moment to estimate my exact weight. Then he whisked to a steel file and lifted out something. Into my lap he dropped a heavy brown file-envelope marked Lopez Case.

I fumbled the bulky legal-wallet open. The notes proved a gold mine for a writer. For a long time I bent low over them seeing nothing else. Then I arrived at Scott’s first theory of a murder so fiendishly peculiar that the murderer was allowed to poison himself. From that longsighted analysis and deduction, my eyes leaped to the man sitting in the swivel-chair behind the desk. A face as grave as Lincoln’s, though I knew he was under thirty-five. He was a natural. A genius at this thing.

What a character! I burned to linger inside his dugout, to get to know him better. Couldn’t I make him a friend?

“Shaking down another crime there?”

“Crime!” He chuckled, as he straightened up a bit from an enormous portfolio leaning from his lap against the edge of his desk. “This is our first advertising campaign for a new client. Rushed to me by my agency, as always just before closing dates. It’s up to me to initial it tonight.”

What a break! My blunder brought my eager overtures to a troubled stop, even if he did take it humorously. I was through muddling across to him; but now he startled me by saying:

“Just about the brightest move of yours was strengthening your chess game.”

“Great jazz! How did you know?”

“When you came in here, your eyes jumped first to the chess cabinet. They said, when they got around to me, that you felt all geared up to trim me tonight.”

I stared at him a bit uneasily. Then I laughed at myself. Not the faintest idea in my noddle then what was coming to me from being placed here tonight with Griffin Scott. I merely felt all sort of oiled up by his growing warmth towards me. I would have made talk, but he looked busy, so I hunched once more over the mass of material on the Lopez murder.

A moment later, he slapped down the portfolio on the glass top of his broad desk.

“Crime was right. Just another clever campaign. I shall have to wade through all the data for a sounder idea tonight.” He threw himself back in his chair, lighted a cigarette. “Dogs aren’t clever—not until whipped into it. Babies don’t get that way, until we applaud ’em. This is a sick age when so many imagine a little part-time cleverness can pole-vault them onto a short-cut to the top. For the love of salt, there’s only one all-time clever class, and that’s the criminal class. Look at ’em. All scorning the beaten tracks; all mapping out short-cuts to what they want.”

He was making talk with me; I answered quickly. “But getting away with murder here.”

“Some murders. Too often the police catch only the corpse but—”

My laugh died as he cocked his head to listen. He spoke hastily and in a low voice.

“That’s Randolph Hutchinson, the district attorney, at the door but you stand by for a spot of chess. It’ll sharpen up me for a go at this advertising.”

Stand by? It would have taken a steam-shovel to root me out of there, with Scott growing friendlier, and with an official coming who had always sent out word to me from his inside office that he was too busy to see me just then. And Hutchinson—might he not be calling here tonight to discuss some baffling murder with Scott?

When Scott introduced me, Hutchinson gave me the usual political smile and hand-hug; but his dark handsome face showed irritation and he roamed around as if preferring to talk to Scott alone.

Scott caught his eye. “I’ve asked Gillmore to stick around for revenge. He writes about the black art of murder, and he’s been reading up on chess. While you, sword-swallower of the third degree,” he whirled his chair around, “rate chess as nothing higher than Spanish torture.”

The hand Hutchinson pointed at Scott shook humorously as he turned to me. “That young Airedale can smell thoughts cooking in your mind, and as for seeing ahead at that game, he’s one damned searchlight.”

“Anything interesting, Randolph?” Scott asked, as the telephone on his desk rang.

“Just calling to keep you friendly.” Hutchinson slumped into a chair and peeled tinfoil off a cigar. “This is my first open spot of rest today, and now—”

Scott held out the receiver to him. “For you. Nasty disposition my telephone has.”

Hutchinson got up with a groan. “One day with the rattlesnake buzzing away on my desk and you’d be biting people but—wait a minute. This must be something sour or they wouldn’t be calling me here. I’ll take it on the hall phone.”

He sauntered out of the office. Scott rolled up the Kirman hearthrug that covered his great chessboard painted upon the floor. If he could have had his way he would have played upon the Piazza San Marco.

We sat on the floor at opposite ends. Tonight I trusted to impress Scott by winning a game. I sprang a carefully memorized variation of the four knights’ opening. Useless! He switched into an answer not in the books, and I couldn’t hold my mind tightly on the game. My thoughts wandered to Hutchinson out in the hall, probably receiving inside news of some crime I’d have to get either highly tabloided or thoroughly expurgated in the morning newspapers.

My game was on the rocks, going to pieces. I looked up sharply. Hutchinson was coming back with faster steps. He dashed into the workshop, his dark face flushed with big news.

“Here’s a hot one. Helen Brill Kent’s killed herself.”

I fell back, incredulous. Arms propped me up against the floor. Why should that blue-eyed, golden-haired Lillie Langtry of our time end her own life? Princes at Biarritz had slipped their equerries to take her by storm. An infatuated shah had compelled a secretly swearing ambassador to lay a smoke Persian cat in its royal basket at her feet. Personages with commanding titles and fortunes had confidently attempted to play with her low-born affections, but this dazzling young Kentucky blonde’s specialty was marriage. And often she had married—often enough to make herself a celebrity the world around. Why should she cut short a career the newspapers made glamorous with descriptions of her jewels and reports of her marriages and mixing with royalty? I scrambled to my feet to learn. Scott, already up, was asking:

“Killed herself! Where?”

“In her Park Avenue apartment. They just found her sprawled over the extravagant ermine floor-rug in her room.”

The thought of that bold and uninhibited beauty lying there rasped the low strings of horror. Scott’s swift question stilled them.

“What did she use—poison?”

Hutchinson strutted a little, swelled up with the news. “No. Banged her damned fascinating little head off with her own pearl-handled revolver. What do you think of that? Killing herself when any one of her ex-husbands would gladly have done it for her.”

“But Helen Brill Kent! Mutilating the head that won her husbands and jewels. That’s all out of focus.”

Hutchinson spun around on him hotly. “What’s the use of disputing a fact? She’s done it.”

“You didn’t see her do it. Did anyone?”

“Of course not. Even that sensational publicity hound wouldn’t shoot herself in public.”

“Her letters—what reason did she give?”

“She didn’t give any reasons. She just went and did it cold.”

Scott, his head bent forward, walked thoughtfully to his desk. I watched him eagerly. He suspected this was murder. Always I had longed hungrily to be in on a big murder right from the start. That ambitious dare-devil had boldly capitalized her good looks; as she soared from a Broadway chorus to high places, the newspapers eagerly dramatized her rise, created a spectacular international beauty. If this should be murder, here loomed the murder of the century. If Griffin Scott would only go out on it and take me along!

Scott stood with one hand lying on the portfolio of advertising on his desk. He wrenched around towards us.

“Know anyone who’ll take my damned advertising agency off my hands?”

His morose tone made Hutchinson laugh. I gloomily watched him drop into the chair behind his desk. He threw a last questioning glance at the portfolio and turned reluctantly towards Hutchinson.

“Randolph, you’ll be down there and I won’t. Now, I wish you’d quiet a doubt that’s been kicking around in my mind for years. Husband Number Four—remember the smooth polite little Marquis? Well, he helped to sell her a bed he swore belonged once to La Pompadour. I don’t believe that. For years I’ve suspected he put something over on his new American wife then. Look it over like a good fellow. Let me know whether he succeeded in swindling that smart girl with a false antique, won’t you?”

Hutchinson poured on me a look of despairing astonishment. “Listen to him fussing about old furniture, when we’re all het up over the suicide of a modern Cleopatra, will you?”

Scott chuckled, like a master of infinitesimal calculus pleasingly accused of being human. My smile felt stiff, waxy. My climbing hopes had gone into a nose-dive, cracked up. Scott, interested as he obviously was, showed that other work kept him from entering this case. Unless Hutchinson now commandeered him, I should have to get details of this shocking tragedy from the newspapers.

Hutchinson glanced at his watch, lurched towards the door. “After midnight. And another delay on my way home. I’m off.”

My eyes dropped, fell on the ruins of my chess game with Scott littering the floor. If this should be murder, didn’t Scott realize how vitally he might be needed on the scene? Then his voice jerked up my head.

“Don’t disappoint yourself, Randolph.”

His sharp tone called me out on the edge of my chair. Hutchinson stood in the doorway, his spring overcoat on over only one shoulder, and he let it hang there.

“What’s on your mind?”

Scott sank back in his chair until its back supported his neck. He surveyed Hutchinson doubtfully.

“Only a suggestion. Don’t allow the police to hurry you out with that as suicide. Find her letters first. Perhaps she mailed them.”

Hutchinson marched resentfully nearer. “A bird with her high-flying past! What’s the matter with you tonight? Sure to blow her head off when remorse caught up with her.”

Scott’s blue eyes hardened, flashed sort of an electric bite on his over-serious young face.

“What! That fearless female Henry the Eighth? She shuffle off the stage of life like a pretzel peddler? See here, Randolph. What have you got against Helen Brill Kent?”

Hutchinson wrestled with exasperated jerks into the other arm of his overcoat. “I know all about that love-pirate. Stuyvesant, her third victim, is a distant connection of mine.” His fists closed; I saw them boring into overcoat pockets. “Look here, Griffin. With the little you know, how can you possibly be so cocksure? Now, get a load of this—”

A chair shrieked. Scott was at Hutchinson’s elbow, urging him along to the door.

“I can’t let prejudice make a goat of you tonight. Let’s get down there and see what has happened.”

I watched them argue all the way across the workshop, my face growing steadily longer. I felt overlooked, left out of it. But then I began to appreciate how seldom Scott, no matter how occupied by others, overlooked anyone. He turned in the doorway and called me.

I let the Lopez case lie where it slipped and ran after them. Could I have foreseen what it meant to be inside on a tragedy such as this right from the start, I couldn’t possibly have been quite so eager. I haven’t been so eager on others since.

In District Attorney Hutchinson’s limousine, we speeded to the scene of Helen Brill Kent’s startling exit from life.

Many regarded that international beauty as a brave young woman, splendidly fearless of both men and divorce. Hutchinson snapped out the quite different judgment of many others.

On the back seat, he glanced cloudily past me at Griffin Scott; his exasperated tone flayed Helen Brill Kent; he might have been showing her up in court.

“Her father was the undertaker in a small Kentucky town. Even if he did set her like a snare behind the dry goods Emporium counter, she baited the snare and she pulled the noose. In less than a week, she noosed the town’s marriage-prize. See her tossing her golden fleece at the proprietor’s son and the next minute luring him back after her again with sidelong glances from her big blue eyes—whipsawing him into eloping with her? That infatuated boy’s neck she made the first rung of her ladder up to the rogue’s gallery of beautiful women.”

Scott moved restively. “Easy, Randolph. She couldn’t have been older than fifteen then.”

Hutchinson made a disgusted sound in his throat. “She was one sweet little adding machine, and you know it. Get the clicking calculation of her. She drops that infatuated hick inside of three months; she travels to New York on his money; she gets on public display in a chorus here before she’s sixteen. And what does she do then? Why, she scans the suckers, winging to that golden hair of hers like moths to a lighthouse. She picks another one. And then right on up, marrying every time she can to advantage; marrying money, then a title, marrying often enough to make herself known around the world. Five husbands if I’ve kept the count straight. And shaking off used husbands in the divorce courts as if they were fleas.”

Scott’s nervous white hand flashed up indignantly. “Don’t act so damned like a traded-in husband. The girl had nothing except her angelic looks. No education. No family to help her. No friends here. No money. Why, they say she walked off the ferry here carrying a battered old straw suitcase so empty that it looked positively famine-stricken. And yet with nothing except her face, her figure and a cool head, she—”

“If that isn’t you defending that scheming dip!” Into Hutchinson’s tone came the resentment of the punisher whose punishment has been questioned. “She went through life precisely like a pickpocket. She picked money, jewelry and husbands. She shucked out the money and jewelry. She tossed the husbands into the ashcan.”

Scott whirled around towards him; his blue eyes blazed. “You’d force a misogamist to speak up for her. Why treat her like an outlaw, when she never broke a law on your books? Why blame her for having no sentiment left, when you know the terrible family she sprang from? Wait a minute! Wait a minute, I’m not half through with you. Look here, Randolph. If you think she so infuriated five husbands, why so sure this is suicide? Why so positive that one of her maddened husbands hasn’t done—”

Another battle over this enigmatic woman, that would never arrive anywhere because the truth lay somewhere in between, ended abruptly. The car stopped before one of the older apartment houses on a corner of Park Avenue and a side street high up in the Fifties.

We forced our way out and through a subway mob of reporters and camera men. One sharp-faced leg-man hung on to Hutchinson, as a thistle hangs on to golf hose, all the way to the elevator. I stared back through its grilled door at the cool but determined swarm the news had mobilized. If a flash merely reporting the death of Helen Brill Kent mobilized that throng of reporters, what if Scott established this to be murder?

A world sensation! And I was to be in at the start!

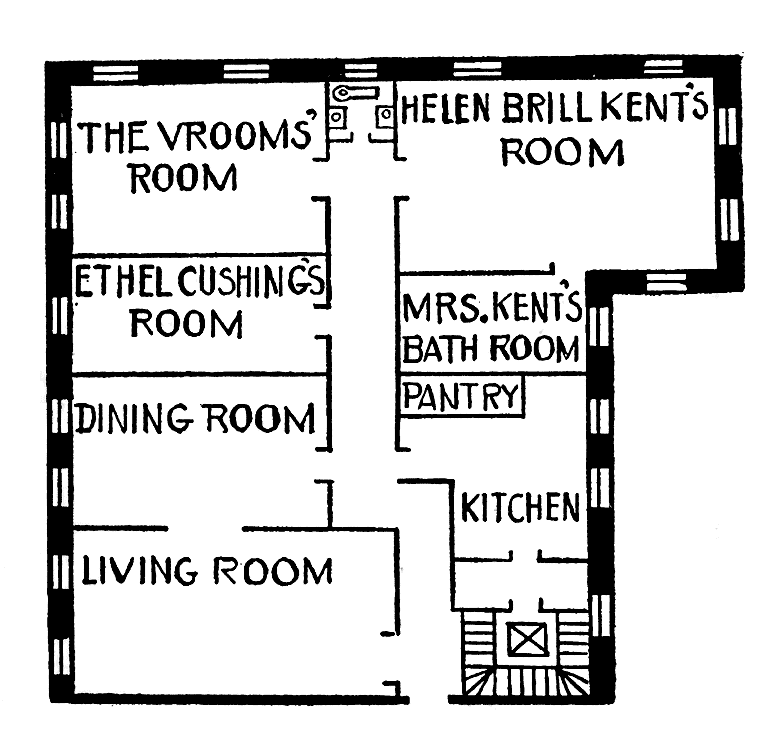

Haff, a young detective swelling in his first important assignment, let us into Helen Brill Kent’s apartment. He swaggered ahead of us down a short front hall. A sharp turn to the left. Down a longer rear hall. Then we stepped softly into the bedroom in which the body had been found.

My eyes traveled fast around the largest room in the apartment. The closed door to the right probably led to her great bathroom. A dainty ciel-blue chaise longue said she liked the throne of Empire favorites. A small inlaid serpentine-front sideboard used as a desk spoke of her weakness for French antiques. Triple full-length folding mirrors hinted a vanity thoroughly businesslike.

Then my exploring eyes flew to the left. Here horror held them. They stayed hypnotized. On a sombre ebony bed lay a covered body. On an ermine floor-rug beside this bed glistened a ragged-edged pool of jellying blood. I felt touched with ice. Was this where it had happened? Where an amazingly eventful career had crashed?

We would learn now, if allowed to remain. Hurrying to us from the center of the large room came a stodgy and corpulent detective of forty-five, Detective-Sergeant Mullens, obviously demanding our reason for trespassing on his case. He appeared neckless; his squarish head was set on his thick shoulders like a snow-man’s; the puffed cheeks of his heavy face looked as fiery as though poisoned by ivy.

He shook hands warmly with Hutchinson, but coldly with Scott and quite indifferently with me, when Scott introduced me. Clearly he welcomed only one of us. I glanced in astonishment at Scott. He, I knew, had saved Sergeant Mullens from blundering badly on the Lopez case, but what now? Plainly the Sergeant hoped to scowl him off this case.

Scott, undisturbed, roamed calmly towards the bed, advising me to follow.

“Any objection to my looking around a bit?” he asked in a tone of idle curiosity.

“Go on,” Hutchinson answered instantly, but Mullens frowned at the world and made no reply.

Hutchinson questioned Mullens in a low tone. Scott drew a black satin coverlet embroidered in gold cautiously down off the torso of Helen Brill Kent.

I stared at her body and shuddered. In her admitted thirties, she still looked in her slim twenties, but death chilled her white skin into marble. Her hair still seemed flowing gold, but great empty blue eyes gazed up fixedly at the rose-tinted ceiling. Her features were classically perfect, but her chin sagged horribly in death. I began to feel queer in my middle section. I turned away hastily.

Over the foot of the bed lay her Novitzky negligee of silver tissue trimmed with ominous black fox. She wore a nightdress of flesh-colored crêpe de Chine hung with ivory Point d’Alençon lace. I couldn’t loosen my eyes from her face now that I was staring at it again, but I breathed easier when Scott bent forward and the great head of knowledge screened the gaping small head of beauty from my sight.

Hutchinson turned towards us a face bright with victory from his consultation with Mullens. He called out noisily to Scott:

“Not a letter here or in the mail—but—she shot herself through the mouth. Asking any surer evidence of suicide?”

Scott barely raised his head. “Talking, yawning or laughing, someone else might have shot her through the mouth. Any powder marks?”

It was Mullens who replied and his tone was ugly. “Sure there are powder marks. Where they ought to be. Inside her mouth.”

Without touching the body, Scott searched for them with his high-powered pocket-flashlight. I glanced over the bed about which he had kept a curiosity alive for years. It was a ghastly contraption of ebony ornately carved. Jutting out in low relief from the headboard, two cupids with untimely smiles winged their way, their hands outstretched but empty over the dead woman.

I touched Scott’s arm as he straightened up from the body. “This isn’t an authentic Pompadour bed, is it?”

“Never. That was the satinwood and figured-tapestry period in beds. The little Marquis helped to swindle her with this, just as I thought, but Helen Brill Kent was nobody’s continuous fool. Out she kicked that commission-making husband soon afterwards.”

Two of his long nimble fingers caught up feverishly the edge of a crêpe de Chine sheet. “Black sheets! A leaf from the book of Ninon de l’Enclos. But Ninon escaped a violent death and a marble slab in the mortuary.”

I repressed a shiver at the harder fortune of this modern beauty.

Scott studied several silvery hairs tipped with black that he discovered upon the coverlet, then glanced quickly beneath the bed. Under flashlight and jewelers’ microscope, he inspected the blood on the black pillow beyond the body and the hemorrhage on the ermine floor-rug. Then he moved past me to the night-stand beside the head of the bed.

“Ah, here’s an authentic piece. A true petit bureau, the sister of a Louis Quinze in the Louvre.”

He examined the rose-colored enamel water bottle and the empty revolver-case upon its old marble top. He bent close to a frosted and flower-hooded incandescent bulb attached to the center of the headboard of the bed. A beautifully designed gold chain to pull it on and off with hung down between the heads of the grinning cupids. He straightened up with a puzzled look on his severe face.

“Look. She tossed her negligee carelessly across the foot-board. She slipped into bed. You can see how her weight hollowed down the taut undersheet. What happened then—in the next few minutes? Her relaxed face tells us nothing—a dead face never does—when the light behind it goes out, no more memory than a mirror.”

But now Mullens’ voice jumped to a pitch that swung us around. He stood glaring at Hutchinson.

“Murder! With all the extra patrols on Park Avenue? With all the people inside here and out there, and the windows wide open, and no one hearin’ the least yip of a scream? Hell, someone’s makin’ you see cockeyed.” Hutchinson turned a pleased yet inquiring smile on Scott. “The Sergeant’s all set to give this out as suicide.”

Across the room leaped Scott. His manner was eager, imploring; imploring where I expected him to be commanding and peremptory, but I realized that he must know his way about here.

“Not yet, Sergeant. My word, no. Wait until we discover why—”

Mullens’ raised hand held up traffic of all other opinions until he laid down his. “It’s suicide. I’m tellin’ you. You’re in one tough jam tryin’ to make it anythin’ else. Listen. Here’s the pill that ploughed through that woman’s neck. I picked it up on the bed. Here’s the shell, off the floor near that ermine rug. Look ’em over, Mr. Hutchinson. Both .32s or I’ll go back on a beat in the sticks. And so’s this gun. Just one pill fired from it. And everyone here identifyin’ this pearl-handled toy as hers.”

Pressing three envelopes containing these into Hutchinson’s hands, he roared on before anyone could cut in.

“Now, that gun. Daytimes they kept it in the drawer of that night-stand side of her bed. Nights the maid put it out on top when she turned down the bed. Look at the empty case over there on the top now. There’s the position chalked on the floor where I picked up the gun. And try to rub this out—I’ve got her finger-prints on that gun of hers. That much picked up, I put Haff on the front door. I had all the people in here one at a time for a sweat. And you ain’t heard nothin’ yet.”

He stopped just for breath. No one could have stopped his noisy, deafening cataract of details.

“Now here’s the pusher. That skinny doll over there was feelin’ all shot. She’d eaten on six pounds that she couldn’t steam off. She was sufferin’ so from neuritis that she threatened to jump out the window—some days she couldn’t derrick the mornin’ coffee to her mouth. She’d sunk so much money in Wall Street lately that she was down close to her jewels. And then, on top of all that, along comes today. And it’s a jumpin’ off spot. It’s her birthday.”

Scott’s head twitched up from a listening pose. “Oh, Sergeant! You expect us to believe that any birthday look back could drive Helen Brill Kent to suicide?”

“You’re damned right it could. Have I got to tell you how women like her grouch on their birthdays after—”

“But you’re classing her wrong. She never looked back; she kept her eyes ahead every minute. Nothing weak or remorseful about that ambitious beauty.”

“Sez you, but you listen to me. She shot her coffee back to the kitchen three times this mornin’. Her temper got fiercer as night came along. Tonight she’s hurlin’ a birthday party to her family in her Rue-dee-Pay parlor here, but how long does she stick it out with them? One blue half-hour. She can’t stand it. Not a minute longer. So she sneaks away in here. She locks the door. Maybe she bends out one of the windows, but doesn’t like to mush up her looks. So she picks up the gun waitin’ for her right on that night-stand. And there she drops herself. On that ermine rug right side of her bed. I’m tellin’ you. This was an open-and-shut case of suicide—nothin’ but. She faced the gun and not one scream out of her.”

I blinked at Mullens. Could this be suicide after all? He made a strong case. I turned hastily to Scott.

He was lighting a cigarette. He paused, the cigarette on its way to his lips in one hand, the yellow-flaming lighter in the other. His tone was that of a diplomat feathering coming shock with satirical praise.

“A perfect pen-and-ink drawing, Sergeant; every detail, even the hungry flies on the toothsome tooth-paste inked in—only she wasn’t shot on that ermine rug. She met death in her ebony bed.”

Mullens’ eyes widened, but he shoved out his chin. “Sure, and that’s why, I s’pose, they found the body on the rug.”

Scott deliberately lighted his cigarette, then impatiently snapped the lighter shut as though choking off a flaming retort. “The higher degree of coagulation of the blood on the pillow tells us something, Sergeant. If we can learn how her body came on the floor, we may step out in the clear on this murder.”

“Murder! Didn’t you get it? I’ve got her finger-prints on her own gun.”

Scott whisked the cigarette from his lips; his eyes shone with zest. “And you expect the cunning genius who schemed this murder to sign his own name on it? Oh, Sergeant, you don’t appreciate an artist at murder.”

“An artist! If someone else croaked her, would he plant the gun as far away from her body on the floor as that?”

“Perhaps he didn’t. Where’s the smoke Persian cat that sleeps on the foot of that bed?”

“Shah? Hell, he’s in the parlor with the people found here. I s’pose you’ll be masterin’ the cat language now and claimin’ he removed the gun from her hand. And next you’ll be sayin’ that scared roll of fluff lifted the corpse from the bed to the floor.”

A stern young face with the stamp of taste upon it considered him critically. “Drowning—going down the last time clutching your straw. I suppose the only way to save you is to knock you senseless.”

“Savin’ me?” Mullens bellowed with laughter. “This time it’s you that’s way out over your head. This time I’m savin’ you.”

Scott struck the fireplace with his cigarette without turning. For the first time I saw him roused. His blue eyes sizzled.

“You act like an old hen. You scratch. You get one worm. You quit. You can’t get away with it. I won’t let you hustle this woman underground as a suicide. A murder that a Borgia might have planned! And you imagine I’ll let such a tantalizing puzzle slip through our hands.”

Mullens’ square face looked as if burning up. “I know my scullions. I’ve got my motive. I’ve got my weapon. I’ve got her finger-prints on it. I’ve got—”

“You’ve got so much that you saw what you wanted to see in one thing. Pull that out and your whole skyscraper collapses.”

“Is that so? Go on. Pull it out.”

Scott bent nearer; he launched a torpedo. “Sergeant, now how could she shoot herself without showing powder marks?”

“Who said she could? I told you—”

Scott groaned. “Don’t—for the love of salt, don’t try to tell me again those dark spots in her throat are powder marks. Put a strong light on them. Check up.”

Mullens’ eyes bulged; his jaw dropped as he evidently saw how a hasty mistake there would cave-in his entire theory. Then his jaw went up into a grin and he started towards the body.

“Come on. I’ll show you.”

“You look them over. I’ll prove those aren't powder marks by this man.” Scott nodded towards someone entering the room.

Mullens glanced at the entering Medical Examiner and then said hotly. “No, you don't. I’ll frame the questions for Doc.”

A hot fight one had to put up to force a new idea on Sergeant Mullens, I thought. Scott hastened away to Mrs. Kent’s desk as though now confident of the outcome, but so also appeared Mullens. He winked slowly at Hutchinson as much as to say, “Doc’ll show him where he gets off,” before hurrying to meet the Medical Examiner.

Medical Examiner Solovitch, short and paunchy, alert but not nervous, nodded to us all as he listened to some information Mullens gave him in a low tone. Then he shook his head and said:

“No, I can do the job better there.”

He went direct to the body. After a close survey, he began mechanically moving the head and members to determine the progress of rigor mortis at the joints. He studied his wrist watch a time and then asked without turning:

“Did this happen about ten tonight?”

Mullens again winked at Hutchinson. “We don't know. You tell us.”

“Well, call it between ten and eleven for as good a guess as you can expect me to make before an autopsy.”

While Scott roamed around, and Hutchinson and Mullens argued, and I gazed nervously out a window, Solovitch completed a more thorough examination. Then he turned towards us brushing his hands, and said in a brisk tone:

“Death caused by a shot through the mouth without injuring her teeth. The shot penetrated between the axis and atlas vertebrae of her spinal column. It fractured her spine at that point causing instantaneous death. Some hemorrhage on that pillow, but mostly internal. There’s an exit wound, so I suppose you have the bullet. No signs of a struggle; not an abrasion of the skin. Any questions?” Mullens’ manner put pressure on him as he took a step towards him. “I’ll tell you there’s questions. Someone’s tryin’ to crowd me to the curb. Take a squint at the blood on the ermine rug and on the pillow. You tell us, Doc, if she didn’t shoot herself on that rug.”

Solovitch examined both spots slowly and thoroughly while I waited anxiously for his decision. Then he turned, wiping his hands on a colored handkerchief.

“No. She was shot in bed there. The amount, character and condition of the hemorrhages indicate that beyond all question.”

Mullens swallowed and spoke with husky eagerness. “O.K., but Doc, you spotted those powder marks in her throat, didn’t you?”

Solovitch stared at him in amazement. “Powder marks?”

Mullens rushed to him. He seized the Medical Examiner by the elbow and pulled him to the body. They bent down. Mullens argued violently in a low determined tone. But Solovitch continued shaking his head.

It was murder! There were no powder marks.

The man who had kept Helen Brill Kent from being lowered into a suicide’s grave quietly resumed his examination of the shell, bullet and revolver that Hutchinson had placed in their envelopes upon the victim’s desk. Hutchinson, now looking troubled, watched every move of his with a new vigilance. Mullens kept his broad back towards us, not ready yet to show his face. Then at a nod of Solovitch’s to a low question, he sprang into action. He lurched across the room and pushed open the bathroom door.

“Come out here.”

At Mullens’ hoarse order, a short but wiry man of about forty-five, wearing the uniform of a captain of the Salvation Army, came into the room.

Mullens waved him towards the Medical Examiner and said: “Her brother, Cleveland Brill. He says he found her body on the floor and put it on the bed.”

His uniform startled me. This woman of the world with a brother a captain in the Salvation Army! Her hair was fine and golden, his a coarse red; her figure was slim and boneless, his gaunt, bony; her face was lineless and perfect, his was tightened by set purposes, gristled. Feeling and fervor seemed to be pushed back in his slightly bulging blue eyes. Solovitch addressed him with obviously assumed severity.

“What did you move this body for?”

Captain Brill answered him fearlessly in the vibrant tone of the street exhorter. “I moved her because I am a Christian and that was my Christian duty.”

“Next time you think of the law first, not your religion.”

“I shall always think first of my religion.”

Solovitch scanned his rigidly earnest face and, with a slight smile at us, ceased arguing with an unexpected zealot.

“Well, now you put the body right back precisely as you found it.”

Captain Brill hesitated a moment. Then with tight lips and out-starting eyes, he crossed the room to do as he was ordered. He hesitated again before he could bring himself to touch the body; he trembled visibly throughout the operation of moving it; and he scurried from the room as soon as permission was granted him. I watched him wondering. Did his dread and his haste to get away spring from natural human horror or guilt? I remember that at that time I couldn’t make up my mind.

The body now lay sprawled upon the floor beside the black bed in which Helen Brill Kent had expected to sleep. Her head, pointing towards the night-stand, covered the red stain upon the ermine rug. The chalked outline of the revolver appeared half way between her head and the nightstand. Far away from the position of the weapon, her right arm extended at a right angle from her body across the rug and bare floor. Her left arm stretched close beside her body.

The sight of this celebrated beauty dropped sprawling there threw a spell of horror on us. It was broken by Mullens. He evidently was a man singularly faithful to his own ideas. His voice sounded much meeker, but he shook his head doubtfully at Scott.

“It’s all off, I know, but she certainly looks as if she shot herself and flopped there.”

Scott jumped up; his voice was harsh; he gave him a fighting look. “Suicide is out. We’ve washed up.”

“All right by me, but at the same time—”

Hutchinson for the first time declared his change of mind; he interrupted Mullens with impatience.

“Now, why bring that up again? Let’s get on.”

Mullens made a wry mouth. “Sure thing. Any questions for Doc?”

He waited until Hutchinson asked a few general questions. Then muttering that he must order Haff to speed up the autopsy and phone for the fingerprint sharps, he accompanied Medical Examiner Solovitch from the room.

In a few minutes, he steamed back. He went direct to Hutchinson. “I s’pose you’ll want to look ’em over now.” Hutchinson squared broad shoulders.

“Who did you catch here?”

Mullens wiped a red face with a folded handkerchief.

“I’ve got six people penned in the parlor. Three men and three skirts. All there was at the party thrown here tonight.”

“Sergeant, which one of them did this?”

Mullens pulled an ear and looked thoughtful.

“I’ve been thinkin’ ’em over. My pick of them all would be Dorothy Vroom, the daughter of this beaut’s stage mother. She looked anxious. She asked too many questions. She acted hot to make out if I got this right as suicide but—” he counted her out with a surly fling of a thick wrist— “no use hopin’ to stick anything on her in front of you gents. Not one damned bit of use. She’s young and she looks like a Spanish dancer. You’d all fall for her looks.”

Hutchinson smiled at him broadly. “And you didn’t yourself, Sergeant?”

Mullens’ red face worked with anger. “No. And if I did, I’m sour on her now.”

It was then that Scott made his discovery. A finger across his lips drew us to him. Caution thinned his voice to a whisper.

“Someone’s trying to work a new eavesdropping stunt on you here, Sergeant. That inside telephone is wedged up.” Over his stooped back, we stared at the apartment’s room-to-room telephone resting upon a low shelf between the head of the bed and the night-stand. The small French handset lay deceptively across the cradle. Scott’s forefinger pointed out a tiny piece of dark paper. This wedged up the plunger. The weight of the handset failed to press that down. The line into this room had been cleverly kept open.

We straightened up startled. Which person here could be so anxious to overhear the decisions arrived at in this room? Who except the murderer?

Into Mullens’ smoky eyes came a glitter. He jostled out from among us.

Scott spoke to him quickly in a carrying whisper, his hands forming a megaphone. “Wait! I haven’t had time to—”

At the door, Mullens’ look thundered for silence.

A moment later, we peered over Mullens’ shoulders through a partly opened door into the bedroom across the hall.

This room was smaller. It was much less extravagantly furnished. The inside telephone, instead of being deftly tucked away out of sight, was here fastened flagrantly to the wall.

Over this leaned a young girl. A tall and slenderly rounded young girl, her hair glossily blue-black. She listened intently, almost she seemed hung by an ear to the receiver.

Mullens’ dull eyes glistened. He stepped inside. His voice broke through the silence, noisy with jubilee.

“Here! Drop that. You come and chew hard on some questions of mine now, young lady.”

A dark startled face of perhaps eighteen twisted around towards us. Shock powdered it with pallor. The small disc held at her ear slipped from her hand. It swung away, struck the plaster wall a harsh swat. For a moment, she stood staring at Mullens, her long lashes fluttering. Then her small head went back and she bravely battened down shock. Just as Mullens predicted, I found myself admiring Dorothy Vroom, but for something more than her looks. I liked the courage with which she stepped out of the room after Mullens.

Mullens’ manner said it. He had caught the girl he suspected.

Sergeant Mullens fussed back ahead of Dorothy Vroom into the room in which Helen Brill Kent had been murdered. He turned; and now his smoky eyes glinted with sweetened suspicion.

“Come in. If you had nothin’ to do with this, the body wouldn’t give you the shakes.”

At sight of the body gruesomely re-sprawled upon the floor, Dorothy Vroom had stopped horrified outside the door. A shudder shook her. At the Sergeant’s crowing insinuation, long black lashes leaped high and curled out. She straightened her tall slender figure, but she remained outside.

Scott darted past her and threw the black satin coverlet over the body.

“Thank you—lots.” She walked gamely into the room.

District Attorney Hutchinson and I followed her. Someone closed the door.

She stood, an arm along the top of a high-backed chair, her dark young face pale, but apparently steeled for an expected collision. Mullens, barrel-bodied, blustered up to her. He poked his huge square face close up to her small oval one.

“Now! Why did you shoot her?”

“Don’t be so devastating. If you’re trying to be funny—”

Mullens cleared away that notion with an ugly sweep of an arm. “Why did you do it?”

She started; a wild and desperate look came into her brown eyes. “Then you don’t think it’s suicide?”

“I’m askin’, not answerin’ questions.” He turned his broad back on her; he looked at us; his look said, “Get that? Remember how eager I told you she was to have me take this for suicide?” Then he whirled around and slapped a hard cynical look on her.

“Hot—ain’t you—to have this called suicide?”

Color painted her face with resentment, but she moved back a step. “You’re positively medieval. I simply asked you what you decided.”

“Huh!” He looked her over with disgust. “All right, then why did you wedge up the phone in here?”

I expected her to quibble; instead she answered frankly. “Isn’t that obvious enough? You wouldn’t tell us a thing. I was curious. I wanted to learn whether you considered it suicide. Wouldn’t you, if you lived where this happened?”

His inability to break her with his close face and bullying goading manner evidently exasperated him. He snapped at her viciously.

“Who’s askin’ the questions? Snap out of that. What did you hear listenin’ in?”

“Not a word. It was tantalizing. I heard only a murmur. I kept hoping it would clear up.”

He snorted. “And you think I’m that mush-headed? I’m askin’ you for the last time. What did you hear?”

“I told you. Nothing.”

Her coolness appeared suddenly to drive him mad. “Who do you think you are?” He gripped her slender shoulder fiercely with a heavy mottled hand. “You come across with the truth. Or I’ll shake it out of you.”

She gasped. She tore away his fingers with both hands. She stood glaring at him, quivering with indignation, too choked by feeling apparently to speak, but her outraged glare said plenty.

He shoved his face right up into hers again. “You heard me? I’ll shake it out of you.”

Her lips came together tightly. They seemed to close a hatch and smother down fire. With an air of restraint, she put a trifle more distance between them. Her chilling look and silence made it icy.

Once more her coolness seemed to madden him. He flung out a hand for her shoulder.

She stepped aside; her coolness vanished; her voice vibrated with rage. “Don’t be so poisonous. You keep your loathsome hands off me.”

Her girlish chin was raised: velvety brown eyes flashed black; an olive face paled with a rush of fearless reckless spirit ready for anything. The hand clenched behind her hip might have held a dagger.

Mullens’ heavy face brightened; obviously he delighted in having discovered the sensitive point at which to break her. His big hands twitched, apparently itching to lay hold of her again. But now I saw Scott deliberately drop upon a bare spot on the floor the wedged telephone handset he had been busily inspecting.

At this shell-like clatter, Mullens spun around and Scott shook his stern head slightly. Mullens scowled, but a questioning glance at Hutchinson got him nothing. He grudgingly took Scott’s advice. He shot more questions at Dorothy Vroom, but he kept his hands off her. He kept them off, although her changed attitude now shut his hands up frequently into fists. There she stood now, silent, distant as the horizon. There was no getting another word out of her. Finally, Mullens threw up his hands and passed her with a black look to Hutchinson.

“You want to question her?”

Hutchinson also now shook his head slightly. Clearly, his manner advised Mullens to let the enraged girl go and get over the fierce resentment his first grip in third-degreeing had roused in her.

At Mullens’ air-sawing growl of dismissal, she went swiftly, but with her head high. I opened the door for her. Her flashing black eyes changed to a surprised soft brown velvet as she thanked me. Then Mullens aired his grievance.

“Just one good soft-gloved sock and I’d have had the whole story but—” His knocking look rapped each one of us— “you all have to fall for her high-steppin’ looks and ways. Oh, hell!”

Scott looked disgusted. “Sergeant, you showed just about as much tact with her as a pair of boxing gloves.”

Hutchinson defended himself with a crisp gesture of annoyance. “Wait. I’ll question her hard enough, but not until I know more about this.”

“Yeah,” Mullens’ lips twisted sourly, “and that young spitfire’ll freeze up the minute you get her where you want her. Tellin’ me she heard nothin’!”

“She didn’t.” Scott’s quiet tone had a punch behind it. “If you’d waited until I looked over this telephone I could have told you she overheard nothing. From this big room, not one word. Not unless someone talked within three feet of this transmitter. It’s the ordinary mouthpiece, not more highly sensitized; no amplifiers connected with it.”

I warmed at his effort to secure justice for Dorothy Vroom, never imagining then that his earlier work with Mullens enabled him to see the hard luck coming to the one Mullens first cleated his suspicion on. To me, the notion that so frank a young girl could possibly have committed murder seemed simply idiotic, yet Mullens’ angry reply thrust cold facts into my mind not to be disregarded.

“We caught her red-handed listenin’ in, didn’t we? And you saw how hot she was to have this called suicide, didn’t you?”

“Oh, Sergeant!” Scott squelched an argument with an irritated rush at him. “Here’s a cunning masterpiece of cold-blooded murder—plotted out, perfected to the last detail—full of blind spots, not one clew, simply crowded with sweet problems—and you choking the first strangely acting bystander up against the wall for all the answers. You just don’t seem to get it. Take the corsets off your mind. Take a deep breath. Look about. Now, shut up! It’s my turn to talk. And your turn to do a little looking around here. Her bedroom door spring-locked; no other way into this fifth-floor room, except by aeroplane. No powder marks; no struggle, and who won’t fight some for life? Not one scream, yet Mrs. Kent faced the weapon and she was no dumb cluck. No window in line with the trajectory of the shot. Nothing but the body. Sweet, baffling, fascinating problems! For us to solve. The fiend who plotted this murder isn’t going to hand us the answers—or any lead to them. Let’s go. What about the famous Kent jewels?”

Scott may have edged his way in on this case, but he certainly was making himself felt now. I gazed at him with awe. Mullens looked rebuked, mastered for a short time. Hutchinson acted suddenly troubled, spoke quickly to Mullens.

“That’s right! Where’s all this female Henry the Eighth’s loot?”

Mullens groaned. “I’d forget them, now wouldn’t I?” He slid open an invisible panel in the south wall, aimed a thick finger at the combination of the wall-safe inside. “They’re all in there O.K. That’s the first thing I had old Lady Vroom, her stage mother, make sure of. But that’s all Wall Street left her.”

Scott tried the door of the safe, found it locked, walked away shaking his head. “Then Wall Street didn’t pick her as clean as usual? She managed to keep the war medals of her beauty, did she? Better see they’re moved to a safer place, Sergeant. You know her unbelievable family. One might have slaughtered her to save that much.”

“Not a chance. No one here knows a thing about her gamblin’ in stocks, except Mrs. Vroom, and she begged me to keep it quiet.”

Scott turned around sharply, walked back towards him. “Well, that’s something to think of. Why should she want that kept quiet?”

Mullens freed himself of domination with a humorous grin. “It hurt her, Mrs. Vroom said, to see money that came so hard to Helen Brill Kent go so easy.”

Scott chuckled. “It does seem to hurt others often more than it does the loser, doesn’t it?” He studied Mullens a moment, and then asked impatiently. “But who’s here? Who was found here to get after on this riddle?”

“The corpse’s father, her two brothers and her daughter, the whole damned family, and Mrs. Vroom and that young snip of a daughter of hers, Dorothy Vroom. But what makes you think this is any riddle?”

“Oh, you’ll see soon enough. It won’t be long now. When they rushed in here, they found that bed-light burning, didn’t they?”

Mullens’ eyes opened wide. “That’s right. Now, how did you guess that?”

“She wasn’t shot in her sleep. Her eyes are open. And they found that chandelier lighted, too, didn’t they?” Mullens’ big mouth fell open; he stared at Scott with disturbed amazement. “Now, who in hell told you that was lighted—after that woman had opened windows and climbed into bed?”

“Oh, it’s much too soon to tell you why I think that, Sergeant.” Scott surveyed the spacious room’s great wrought-iron chandelier that sprouted a garden of tulip-shaped yellow bulbs and nodded his head. “Yes, that matches up,” he said to himself.

Mullens soured at being left out of something. “I guess I can see as far ahead as anyone.” He muttered to himself a moment and then addressed the world. “It makes me sick the way some people jump in on a case and pretend to know everything when they haven’t one damned lead.”

“Lead? You want a real lead?” Scott’s eyes blazed at him. “Why the spring lock on a bedroom door?”

Hutchinson jumped; he looked sharply towards the door to the hall. “Is there a spring lock on that door?”

“Sure, but what of it?” Mullens confidently waved it out of the pattern. “With her queer family, you yourself would clap on an extra lock to keep them nuts from droolin’ in on you all the time.”

At this disdainful treatment of his offered lead, Scott’s manner sharpened for another set-to with him. The war of differing opinions common in the early stages of a real mystery appeared about to break out again. But now, two finger-print specialists from Police Headquarters, one carrying a camera and equipment, popped briskly into the room, and Scott dashed impatiently to Hutchinson to ask:

“Can’t we get a look at this apartment and the people here while these men are working?”

Hutchinson nodded. He waited until Mullens tipped off the finger-print experts and then made the suggestion to him.

Mullens nodded grumpily. As we all started towards the door, I saw Scott attempt to slip him a secret suggestion. In a carefully lowered tone, he said something quickly meant for the Sergeant’s ear alone. But Mullens jerked away petulantly and made it public.

“Yeah? You question them, too, do you?” He swung around testily to the finger-print sharps prowling around the big room. “While you’re about it, take the fingerprints of the corpse. And squirt some powder over the print I showed you on the gun. Someone here’s hipped with the idea that isn’t the victim’s John Hancock on the weapon.”

Mullens must have been rattled not to think of that, I thought. Wondering whose finger-prints would be found on that weapon, I followed the others from the room.

Mullens and Hutchinson led the way.

Lights burned in every room and hall to drive away shadows, but over the apartment hung the creeping hush that follows unexpected death. This was a normal Park Avenue apartment, but baffling, cold-blooded murder devilled it for me with unseen but watching evil spirits. And soon Helen Brill Kent’s incredible family and others involved were to make this a haunt of horror. I tagged along behind three men whose experience had apparently calloused them to all that.

We looked first around the smaller bedroom opposite assigned to Mrs. Vroom, Helen Brill Kent’s stage-mother, and to Dorothy Vroom. Then around the still smaller bedroom beyond on the right, belonging to Miss Ethel Cushing, Mrs. Kent’s only daughter. Mullens grunted out information and kept a jealous eye upon Scott, who merely wandered around each room. The first door upon the left in this longer rear hall swung into the pantry. Through its glass panel, we glanced at a cook and two maids in the kitchen beyond. They apparently awaited rebelliously permission to go to bed.

We turned to enter the dining room opposite. Sounds of a scuffle at the front of the apartment startled us.

We rushed up the front hall. Detective Haff, lean but cocky, shouldered the wide front door shut against outside force. With his back against it, he turned and jubilantly saluted Mullens.

“Another fresh reporter?” Mullens asked him.

The youngest detective of the Homicide Bureau, strutted confidentially nearer.

“That bunch of sweetness in there,” he nodded towards the living room, “Miss Vroom they tell me her name is, must’ve phoned out to her boy-friend. He’s outside and marked up some, and outside he stays.”

Mullens spoke out the corner of a mouth that showed a pleased grin. “That’s the stuff, Haff. Sock him or anyone else tryin’ to barge in here to her. We have our doubts about that young lady.”

“Is that so?” Astonishment for a moment seemed to darken Haff’s pleased look. “Well, she’s too good for that college cut-up anyway. And now you’ve passed the order—” he held up a bony hand and clenched it slowly with menace.

Could Dorothy Vroom’s frankness and spirit and good looks have misled me utterly regarding her? Was it possible that young girl did have something to do with the murder? And now that she realized that we recognized this as murder had guilt urged her to telephone outside for help? Startled by this unhappy doubt, I stared at Haff. And there behind him, Dorothy Vroom appeared in the wide entrance to the living room.

Her dark young face looked deeply troubled; her brown eyes anxious, as she asked Haff:

“Wasn’t that someone for me?”

He smiled all over her. “Oh, no. You just leave it to me to tip you, if anyone calls for you, lady.” He turned and winked at us.

She gazed at his back doubtfully. “You really will?”

“I sure will.”

Still looking doubtfully back, she disappeared into the living room.

I sincerely hoped that my doubt of her was misplaced. But as I followed the others back to the rear hall, Hutchinson and Mullens looked at each other in a way that indicated growing assurance of her guilt.

Through the last door on the right in the rear hall, Mullens preceded us into the dining room. From this room, as the accompanying plan shows, a broad connecting entrance afforded us a view of all people found here tonight and held.

From this dark dining room, we studied six people in the brilliantly lighted living room. Which one of these amazingly different types had murdered Helen Brill Kent? Huddled together in three chairs at the far end of a modern French salon, three men sat in whispering conference. Captain Brill of the Salvation Army sat stiffly erect in the middle. His elephantine father and his emaciated, dinner-jacketed, crafty-looking younger brother, Napoleon Brill, leaned towards him, elbows on knees, and appeared to be questioning him sharply but in guarded tones. I had a feeling that they were cunningly extracting from him everything he had learned while in the room with us where the murder had been committed.

Far away from them, at the end of the living room near us, sat the three women in dejected silence. Gaunt and dark Mrs. Vroom, the victim’s stage-mother, stared crumpled into space from a gilded armchair. On a stool against one knee sat her daughter Dorothy. One hand held her mother’s tightly, but she glanced frequently and anxiously towards the entrance. On a window-seat to their left sat Ethel Cushing with plump legs stretched out before her. I gazed at her with quick curiosity. People wondered how so beautiful a woman as Helen Brill Kent could have had such a homely daughter. Her large round face brooded over an open book. Alert on its haunches upon the white mantel at this end of the living room, in vigilant isolation from all these human beings, sat the smoke Persian cat named Shah. Gleaming orange eyes, earlier fixed upon the people in the living room, now sharply watched us in the dark dining room.

Which one a murderer? I scanned six strangely different human beings without being able to pick out the killer. Had Scott singled him out? No, his eyes travelled from one to another. But with such a depth of interest that I soon had to touch his elbow. District Attorney Hutchinson and Sergeant Mullens were moving on. Mullens stopped before the glass panel in the pantry door opposite, pointed through it into the adjoining kitchen and suggested to Hutchinson:

“Better let me send those three servants up to bed. The cook’s evidently been sopping up Jersey lightning. She looks lighted to the pent-house and they don’t know a damned thing. They were out to a cinema together; they showed me their seat stubs.”

We passed through the pantry into the small kitchen. A jug-shaped cook with glazed eyes and two trimly attired older maids, lolling around the kitchen table, glanced at us eagerly. Hutchinson asked them a few perfunctory questions, then waved them away upstairs to bed. We watched them scramble to the back-door like women to a bargain counter, but Scott’s keen eyes had spied something.

“One minute!” he called. “The spring lock on this door—isn’t this new?”

In the narrow back hall, the flushed-faced cook lurched around towards him. “New? Sure, it’s new. New as the water on my knee since I came to work in this sweatshop.”

Scott chuckled. “And how long is that? I mean how long has this lock been on here?”

“Two months, your honor. Sez she, ever since the last cook walked off in a huff with her key to the old lock. Sez I, don’t you believe a word of that two-faced slut.”

“Come along, Kittie. The gentleman is through with you.” The two maids dragged their excited companion up the stairway that mounted around the service elevator.

Scott closed the kitchen door. He bent over the new spring lock on the back door of the apartment with an interest it failed to arouse in Hutchinson and Mullens.

Hutchinson smiled skeptically at Mullens. “A couple of cooks that could have killed Mrs. Kent for saying their coffee was bad.”

Mullens grinned. “That’s it. If words was bullets, only one man, woman or child would be alive today.”

They moved on. Scott and I followed them back into the room in which murder had happened. The fingerprint specialists had completed their work, leaving an odor of burned powder. Mullens listened to their report. He swung around to Hutchinson, his eyes burning with excitement.

“What do you know about this? We may have a pinch right in reach. Those ain’t Mrs. Kent’s prints on the gun. The professor here says her right thumb shows tented arches. And the print on that gun shows meetin’ whorls. I’m slippin’ into the parlor with these sharps. I’ll get the thumb-prints of those six people. If one of them shows meetin’ whorls, this case, someone thinks so damned hard, will be right in the bag.”

Could Scott be wrong? I whipped around for a look at him, as Mullens called the two finger-print men and tramped from the room ahead of them. Scott idly started to follow them. He carelessly gave up that purpose at sight of the two white-jacketed men coming into the room bearing a stretcher.

As these men rose from dropping the stretcher beside the body of Helen Brill Kent, Scott slipped each a folded bill and evidently whispered a suggestion. The men nodded and disappeared into the bathroom. They reappeared bringing a towel and a tiny wad of cotton batting. A sagging jaw, they tied up with a towel passed under the chin and knotted over golden hair; the cotton batting they gently inserted in nostrils. Then, after a glance at Scott for approval, they moved the body with exaggerated tenderness from the floor to their stretcher and covered it. A moment later, they bore out of her luxurious room the body of an international beauty destined now to meet the knife of autopsy.

Hutchinson, who had watched all this with a faintly superior smile of amusement on his strong face, said something to Scott too quickly for me to catch.

Scott moved away without replying, as if caught at an action he would have preferred to keep secret.

And then Mullens, flaunting a number of finger-prints and a smiting manner, whiffed gustily into the room.

“You made me take my hands off her,” he said. “All right, but now I’ve got ’em right on her throat. You see these? Dorothy Vroom’s finger-prints smack on the gun that croaked Mrs. Kent.”

I felt knocked limp and faint.

“Look!” Mullens held up the smudged pieces of paper before Hutchinson. “Here’s the meetin’-whorl pattern the men cameraed on that revolver. And here’s Dorothy Vroom’s right thumb-print. You see this island here? Well, there it is there—And this bifurcation or forking line here? There it is socking you right in the eye—Now, sink your eye-tooth into that little ridge-dot—And into that one there. Not another girl’s thumb in the world has them. Signed right on the weapon. We’ve got her. It’s the clincher.”

Scott and I crowded them for a closer view of the startling evidence. I stared dully at the dirty smudges that fixed the murder of Mrs. Kent on that young girl.

There was a tingling silence. Then Scott punched Mullens with a fiery glance.

“Sergeant, you’re crazy as a June-bug. The crafty schemer who plotted this murder drop us a finger-print? He just couldn’t do it. Didn’t she explain this?”

Mullens’ heavy face parked a joyful grin. “Sure, she explained this. Catch that smart young lady without an explanation. But I had to threaten to run her in to get her thumb down here. And by the time I cornered her out in the hall, she dished out a damned raw mess of fish. She tried to make me think that when Captain Brill hoisted up the body to the bed, she picked up the revolver from the floor. She was scared blue, she was, that he might stumble over it with the body. That hard little devil worrying about a little thing like that! It’s so touching, it makes me weep.”

Scott may have started all this trouble rolling down on Dorothy Vroom, but once more I heard him speak up hotly in her defense.

“Weep? You make me weep real tears. What better explanation do you want?”

Mullens crooked up one corner of his mouth. “Hot damn, but she’s got you goin’ strong for her. Listen! Why did she plop it right down on the floor afterwards? Why didn’t she fear her mother or someone else would stumble over it? Why can’t she name just one of the five others there who saw her pick it up afterwards?”

“She could, if she was cunning enough to put this through.”

With a disgusted grunt, Mullens whipped around to Hutchinson.

“What about it? Do I make the pinch now, or you want to grill her first?”

“You go and—”

Scott’s angry movement stopped Hutchinson.

“Man alive! Why don’t you make sure first no one did see her pick it up afterwards?”

Hutchinson thought a moment.

“Right! That’s the thing to do. Before she gets to the others to back up her feeble story.” He turned briskly to Mullens. “You order Haff to send in that Salvation Army officer. And then you two both take to the sidelines and watch me take the ball. I’m taking charge here now.”

A few minutes later, Captain Brill’s wiry little figure sat rigidly erect on the edge of a low-backed, cretonne-covered armchair. His slightly bulging emotional blue eyes were fixed hard as a wrestler’s on Hutchinson. His fingers were laced together over his lap with a tightness that hinted it would be hard to pry anything out of him.

Hutchinson looked at him a moment, and then took a round-about way to the information he was after.

“Captain Brill, did your sister fear anyone—say, unruly servants or divorced husbands?”

The knotted hands unknotted. Captain Brill’s stiffness eased up visibly, though he shook his bristling red hair firmly.

“No. Helen never knew fear. It would have been far better for her, if she had.”

“Now, what do you mean by that?”

Captain Brill’s protruding eyes fired with sudden fervor. “If she had known proper fear, she might have saved her soul. What else is of real consequence, brother?”

The passion of the zealot vibrated his tone. Exhortation loomed in the rapt eager way he bent forward, but Hutchinson spoke quickly.

“Suppose you tell us in your own words exactly what happened here tonight.”

The witness raised quickly a freckled bony hand. “First I want to explain how I came to be here. I didn’t come to join in the celebration of my sister’s birthday, but because I was told that she was suffering from neuritis for her sins. I have no time for parties.” His earnest look demanded the belief of each one of us before he went on. “We gathered in the living room. About nine Helen came in there. But her sins were tormenting her too greatly for her to stay long. At half past nine, she left us and came in here to go to bed. She—”

Hutchinson with an impatient movement turned him elsewhere. “When did you hear the shot?”

“I heard a sound that I know now must have been the shot at exactly twenty minutes past ten.”

“How can you be so positive about that time?”

“I looked at the tall clock in the living room.”

“Who were in the living room with you then?”

“Only Ethel Cushing, my sister’s daughter, but—”

Hutchinson moved swiftly nearer. “You’re sure you and Miss Cushing were the only ones in the living room, when the shot was fired at this end?”

“Yes, but the others were in their own rooms, not in this room.”

Hutchinson turned away, asking carelessly. “Quite sure of that?”

“I am.”

Hutchinson spun around towards him. “How can that be true? Your father and brother have no rooms here.”

A quick flood of red on a thin earnest face, but his eyes refused to drop. “No. I spoke hastily. My father and brother were in the bathroom next door to here.”

“Did you see them there?”

“No, but they told me they were there and I have faith in them.”

Things began to look slightly better to me. No longer was Dorothy Vroom the sole person here to suspect. At the time of the shot, Jesse and Napoleon Brill claimed to be next door. But were they there? I recalled the furtive way they appeared to be questioning this witness after he replaced the body upon the floor and was permitted to join them in the living room. It seemed to me that suspicion might much better be directed at them that Hutchinson now concentrated upon the young girl caught listening in.

“But Dorothy Vroom—she told you she was in her own room then?”

“No. I didn’t ask her. But I’m sure she had nothing to do with this. My wretched sister took her own life.”

“Oh no, she didn’t. We have positive proof she didn’t. And now, suppose I demonstrate to you that Dorothy Vroom—”

“Don’t waste your time. I shall throw the first stone at nobody.”

Captain Brill gathered himself together rigidly and that was that. Hutchinson fenced with him and wrestled with him; bullied him; jabbed him with sarcasm; but this tight lipped martyr could not be made to consider this a case of murder; nor could he be either cajoled or driven into saying one word placing suspicion on others. With an impatient gesture, Hutchinson finally gave up.

“Well, go on with your story.”

Captain Brill’s inflexible attitude relaxed. “Ten minutes after we heard the sound that we thought was just automobile exhaust, Dorothy Vroom and her mother came into the living room. Dorothy had to go out to keep an engagement. Before she got away, my father and my brother Napoleon entered, and Nappy asked Dorothy to wait for him. She wouldn’t. So Nappy playfully snatched away her gloves. And then, before I could bring peace between them, Miss Cushing came running in and whispered something that hushed us all up tight with horror.”

“What did she whisper?”

I strained forward. My mind raced like a disconnected engine. Now, we were to hear how Helen Brill Kent’s body had been discovered.

Captain Brill moistened thin lips. He went on in the resonant tone of the street exhorter, a tone that sounded queerly over-strong pealing out of so small a man.

“She whispered that she had pounded and pounded and pounded on this door, but no answer.”

“And then?”

“And then, I hammered and hammered, and I couldn’t get an answer. I stooped and looked through the keyhole. All I could see was an arm. But it lay along the floor. And it didn’t move. So I called for a key and Mrs. Vroom brought hers. I opened the door. There was the terrifying swish past us out from under the bed of the cat. Then we got our nerves together and all came in. And here Helen lay stretched out on the floor.” He closed his eyes evidently to shut out horror; he opened them too soon. “At first, I hoped she had only fainted. I lifted her up on the bed. But then I saw that terrible wound in her mouth and neck and I knew the worst had happened. Her sins had made her take her own life. Before she could repent.” For an interminable moment, he regarded us—a steady look, not drooping and sad, but stiffened with severity, as if a younger sister, though foolish people might envy her worldly riches, had come to a bad end through not listening to him. Into my mind a thought bounded. How that sister and brother, governed by such contrary purposes and morals, must have clashed! One so beautiful but mercenary; the other so homely but devout. Whenever they met, eyes must have flashed; mouths must have poured out the kindling criticism and the inflaming advice that crackle into the fiercest family fights. What if such a fight had been fought between them here tonight?

Hutchinson, intently groping for further evidence against Dorothy Vroom, disregarded that possibility. But not Scott apparently. I saw him bend on Hutchinson a look of acute surprise at the turn his next question took.

Hutchinson, squaring broad shoulders, planted himself directly in front of Captain Brill. He put him under a hard look.

“Now, after you came in here and found your sister’s body, did you at any time see anybody pick up the revolver from the floor?”

I leaned forward. Would Captain Brill understand? The guilt or innocence of Dorothy Vroom hung on his answer to that shrewdly worded question. He evidently didn’t; he studied Hutchinson doubtfully, but only for a moment; then he replied with decision.

“No, sir. I saw no one pick up the revolver.”

“Or anyone at any time afterwards place the revolver back upon the floor?”

The witness studied his questioner a longer time; he answered with less decision.

“No, sir. Not that I remember.”

Hutchinson flashed a triumphant glance at Scott; he asked his next question persuasively and with his eyes aimed out a window.

“Then if Miss Dorothy Vroom says that she picked up the revolver after the crime just to save you from stumbling over it with the body, she probably isn’t telling us quite the truth, is she?”

I knew that incriminating question was coming. I felt a twinge of sorrow for the young girl about to be incriminated. But Captain Brill’s response made me start and sit up quickly. He shook his head stubbornly. His voice rang out in the still room.

“I won’t say that.”

I felt like breaking into cheers for him; but Hutchinson’s manner prodded him confidently.

“Why won’t you say that? You didn’t see her pick it up or lay it down after the crime, did you?”

“No, I didn’t but—but how could I, when my back was towards her?”

Hutchinson scowled as if he had just lost the king of the stream off his hook. “You couldn’t have kept your back towards her. Not all the time.”

“Most of the time. And—remember this. I was too shocked by my sister’s death to notice a little thing like that.”

Hutchinson raised an angry hand, also his voice. With a heckling frown, he drove him. “This is no little thing, Captain Brill, and don’t you think for one minute that it is.”

“I don’t care. I won’t say that.”

And Hutchinson couldn’t make him.

After trying to in vain, he shifted sharply to another matter. “Now I want you to tell me how you fixed the time you gave us.”

Captain Brill’s eyes widened. “As I told you, I looked at the clock. It said twenty minutes past ten.”

“Yes, yes, I didn’t mean that at all. I remember with what superb forethought you looked at the clock when you heard the shot. People always look at some clock or go out on the street and ask some passerby the minute whenever a car hiccoughs. What I want you to explain now is, how did you know it was just ten minutes after the shot when Dorothy Vroom came flying into the living room?”

His witness shook his head sternly. “I didn’t say that she came flying in there.”

“You said that she was in a great hurry to go, didn’t you?”

“No, I said that she had to go out to keep an engagement.”

“Well, we won’t quibble over words.” Hutchinson hovered over him, his manner growing friendlier, but merely cheese in a trap. “But you don’t expect me to believe that you kept your eyes on the clock all the time, do you? And so, how can you say it was ten minutes after the shot—precisely half-past ten, in fact—when Dorothy Vroom came into the living room?”

Another trap. And one likely to snare them both in an incredible explanation. But Captain Brill’s explanation was so simple and commonplace as to prove to me singularly convincing.

“I didn’t keep my eyes on the clock. And I didn’t look at it again then. I didn’t have to. Dorothy and her mother came into the room. At that moment the clock chimed the half-hour. And what Dorothy said then made me hear it. Because she said, ‘Oh, mother, I’m late. I promised faithfully to meet Bascomb at half-past ten.”

I smiled; so did Hutchinson, but his smile curled into sarcasm.

“Wonderful! Whenever your eyes grew inattentive to the clock, it got all worked up and spoke to you. But let that slide. Now, how did Dorothy act when she came into the living room then—nervous, worried, anxious to get out of the apartment?”

The witness shook his head inexorably. “I said that she had to go out and that she was late but—”

“Then she must have seemed worried and anxious.”

Captain Brill set thin lips firmly. “No. I won’t say that. I said—”

“You’ll have to admit that. If she was late, how could she help acting worried and anxious?”

“I didn’t notice that she did. And I won’t say that.”

As they fought over that point, I looked down at the floor disgusted. If this witness did act strangely as if shielding others, why should Hutchinson strive for evidence against Dorothy Vroom only? And now Scott rebelled; he got up restively and said to Hutchinson.

“Randolph, I’m going out to check the time of that clock in the living room. Mind if I ask Captain Brill a few questions before going?”

Hutchinson spread over him an annoyed look. “Go on, if you’re suffering from blood pressure.” He retired to a chair, but his hands gripped its arms, ready to catapult him back into his argument at the first open moment.

Scott sat down and stretched out his legs before him, as though his questions were of no particular moment; he bent over and with his handkerchief flicked dust off one shoe, before inquiring in a voice peculiarly soothing after Hutchinson’s exasperated tone.