a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Red Window Author: Fergus Hume * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1700241h.html Language: English Date first posted: March 2017 Most recent update: March 2017 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Chapter I. Comrades

Chapter II. Sir Simon Gore

Chapter III. The Will

Chapter IV. A Strange Adventure

Chapter V. Lost in the Darkness

Chapter VI. A Maiden Gentlewoman

Chapter VII. Bernard’s Friends

Chapter VIII. Bernard’s Enemies

Chapter IX. At Cove Castle

Chapter X. A Statement of the Case

Chapter XI. Mrs. Gilroy’s Past

Chapter XII. The New Page

Chapter XIII. A Consultation

Chapter XIV. Love in Exile

Chapter XV. The Past of Alice

Chapter XVI. The Unexpected

Chapter XVII. The Diary

Chapter XVIII. Tolomeo’s Story

Chapter XIX. Plots and Counterplots

Chapter XX. A Confession

Chapter XXI. Young Judas

Chapter XXII. The Truth

Chapter XXIII. A Year Later

“Hullo, Gore!”

The young soldier stopped, started, colored with annoyance, and with a surprised expression turned to look on the other soldier who had addressed him. After a moment’s scrutiny of the stranger’s genial smile he extended his hand with pleased recognition. “Conniston,” said he, “I thought you were in America.”

“So I am; so don’t call me Conniston at the pitch of your voice, old boy. His lordship of that name is camping on Californian slopes for a big game shoot. The warrior who stands before you is Dick West of the — Lancers, the old Come-to-the-Fronts. And what are you doing as an Imperial Yeoman, Gore?”

“Not that name,” said the other, with an anxious glance around. “Like yourself, I don’t want to be known.”

“Oh! So you are sailing under false colors also?”

“Against my will, Conniston—I mean West. I am Corporal Bernard.”

“Hum!” said Lord Conniston, with an approving nod. “You have kept your Christian name, I see.”

“It is all that remains of my old life,” replied Gore, bitterly. “But your title, Conniston?”

“Has disappeared,” said the lancer, good-humoredly, “until I can make enough money to gild it.”

“Do you hope to do that on a private’s pay?”

West shrugged his shoulders. “I hope to fight my way during the war to a general’s rank. With that and a V.C., an old castle and an older title, I may catch a dollar heiress by the time the Boers give in.”

“You don’t put in your good looks, Conniston,” said Bernard, smiling.

“Dollar heiresses don’t buy what’s in the shop-windows, old man. But won’t you explain your uniform and dismal looks?”

Gore laughed. “My dismal looks have passed away since we have met so opportunely,” he said, looking across the grass. “Come and sit down. We have much to say to one another.”

Conniston and Gore—they used the old names in preference to the new—walked across the grass to an isolated seat under a leafless elm. The two old friends had met near the magazine in Hyde Park, on the borders of the Serpentine, and the meeting was as unexpected as pleasant. It was a gray, damp October day, and the trees were raining yellow, brown and red leaves on the sodden ground. Yet a breath of summer lingered in the atmosphere, and there was a warmth in the air which had lured many people to the Park. Winter was coming fast, and the place, untidy with withered leaves, bare of flowers, and dismal under a sombre, windy sky, looked unattractive enough. But the two did not mind the dreary day. Summer—the summer of youth—was in their hearts, and, recalling their old school friendship, they smiled on one another as they sat down. In the distance a few children were playing, their nursemaids comparing notes or chatting with friends or stray policemen, so there was no one near to overhear what they had to say. A number of fashionable carriages rolled along the road, and occasionally someone they knew would pass. But vehicles and people belonged to the old world out of which they had stepped into the new, and they sat like a couple of Peris at the gate of Paradise, but less discontented.

Both the young men were handsome in their several ways. The yeoman was tall, slender, dark and markedly quiet in his manner. His clear-cut face was clean-shaven; he had black hair, dark blue eyes, put in—as the Irish say—with a dirty finger, and his figure was admirably proportioned. In his khaki he looked a fine specimen of a man in his twenty-fifth year. But his expression was stern, even bitter, and there were thoughtful furrows on his forehead which should not have been there at his age. Conniston noted these, and concluded silently that the world had gone awry with his formerly sunny-faced friend. At Eton, Gore had always been happy and good-tempered.

Conniston himself formed a contrast to his companion. He was not tall, but slightly-built and wiry, alert in his manner and quick in his movements. As fair as Gore was dark, he wore a small light mustache, which he pulled restlessly when excited. In his smart, tight-fitting uniform he looked a natty jimp soldier, and his reduced position did not seem to affect his spirits. He smiled and joked and laughed and bubbled over with delight on seeing his school chum again. Gore was also delighted, but, being quieter, did not reveal his pleasure so openly.

When they were seated, the lancer produced an ornate silver case, far too extravagant for a private, and offered Gore a particularly excellent cigarette. “I have a confiding tobacconist,” said Conniston, “who supplies me with the best, in the hope that I’ll pay him some day. I can stand a lot, but bad tobacco is beyond my powers of endurance. I’m a self-indulgent beast, Gore!”

Gore lighted up. “How did your tobacconist know you?” he asked.

“Because a newly-grown mustache wasn’t a sufficient disguise. I walked into the shop one day hoping he was out. But he chanced to be in, and immediately knew me. I made him promise to hold his tongue, and said I had volunteered for the war. He’s a good chap, and never told a soul. Oh, my aunt!” chattered Conniston. “What would my noble relatives say if they saw me in this kit?”

“You are supposed to be in California?”

“That’s so—shootin’. But I’m quartered at Canterbury, and only come up to town every now and again. Of course I take care to keep out of the fashionable world, so no one’s spotted me yet.”

“Your officers!”

“There’s no one in the regiment I know. The Tommies take me for a gentleman who has gone wrong, and I keep to their society. Not that a private has much to do with the officers. They take little notice of me, and I’ve learned to say, ‘Sir!’ quite nicely,” grinned Conniston.

“What on earth made you enlist?”

“I might put the same question to you, Bernard?”

“I’ll tell you my story later. Out with yours, old boy.”

“Just the same authoritative manner,” said Conniston, shrugging. “I never did have a chap order me about as you do. If you weren’t such a good chap you’d have been a bully with that domineering way you have. I wonder how you like knuckling under to orders?”

“He who cannot serve is not fit to command,” quoted Gore, sententiously. “Go on with the story.”

“It’s not much of a story. I came in for the title three years ago, when I was rising twenty. But I inherited nothing else. My respected grandfather made away with nearly all the family estates, and my poor father parted with the rest. Upon my word,” said the young lord, laughing, “with two such rascals as progenitors, it’s wonderful I should be as good as I am. They drank and gambled and—”

“Don’t, Conniston. After all your father is your father.”

“Was my father, you mean. He’s dead and buried in the family vault. I own that much property—all I have.”

“Where is it?”

“At Cove Castle in the Essex Marshes!”

“I remember. You told me about it at school. Cove Castle is ten miles from Hurseton.”

“And Hurseton is where your uncle, Sir Simon, lives.”

Gore looked black. “Yes,” he said shortly. “Go on!”

Conniston drew his own conclusions from the frown, rattled on in his usual cheerful manner. “I came into the title as I said, but scarcely an acre is there attached to it, save those of mud and water round Cove Castle. I had a sum of ready money left by my grandmother—old Lady Tain, you remember—and I got through that as soon as possible. It didn’t last long,” added the profligate, grinning; “but I had a glorious time while it lasted. Then the smash came. I took what was left and went to America. Things got worse there, so, on hearing the war was on, I came back and enlisted as Dick West. I revealed myself only to my lawyer; and, of course, my tobacconist—old Taberley—knows. But from paragraphs in the Society papers about my noble self I’m supposed to be in California. Of course, as I told you, I take jolly good care to keep out of everyone’s way. I’m off to the Cape in a month, and then if Fortune favors me with a commission and a V.C. I’ll take up the title again.”

“You still hold the castle, then?”

“Yes. It’s the last of the old property. Old Mother Moon looks after it for me. She’s a horrid old squaw, but devoted to me. So she ought to be. I got that brat of a grandson of hers a situation as messenger boy to old Taberley. Not that he’s done much good. He’s out of his place now, and from all accounts, is a regular young brute.”

“Does he know you have enlisted?”

“What, young Judas—I call him Judas,” said Conniston, “because he’s such a criminal kid. No, he doesn’t. Taberley had to turn him away for robbing the till or something. Judas has spoiled his morals by reading penny novels, and by this time I shouldn’t wonder if he hasn’t embarked on a career of crime like a young Claude Duval. No, Gore, he doesn’t know. I’m glad of it—as he would tell Mother Moon, and then she’d howl the castle down at the thought of the head of the West family being brought so low.”

“West is your family name, isn’t it?”

“It is; and Richard is my own name—Richard Grenville Plantagenet West, Lord Conniston. That’s my title. But I dropped all frills, and here I smoke, Dick West at your service, Bernard, my boy. So now you’ve asked me enough questions, what’s your particular lie?”

“Dick, Dick, you are as hair-brained as ever. I never could—”

“No,” interrupted Conniston, “you never could sober me. Bless you, Bernard, it’s better to laugh than frown, though you don’t think so.”

Gore pitched away the stump of his cigarette and laughed somewhat sadly. “I have cause to frown,” said he, wrinkling his forehead. “My grandfather has cut me off with a shilling.”

“The deuce he has,” said Conniston coolly. “Take another cigarette, old boy, and buck up. Now that you haven’t a cent, you’ll be able to carve your way to fortune.”

“That’s a philosophic way to look at the matter, Dick.”

“The only way,” rejoined Conniston, emphatically. “When you’ve cut your moorings you can make for mid-ocean and see life. It’s storm that tries the vessel, Bernard, and you’re too good a chap to lie up in port as a dull country squire.”

Bernard looked round, surprised. It was not usual to hear the light-hearted Dicky moralize thus. He was as sententious as Touchstone, and for the moment Gore, who usually gave advice, found himself receiving it. The two seemed to have changed places. Dick noticed the look and slapped Gore on the back. “I’ve been seeing life since we parted at Eton, old boy,” said he, “and it—the trouble of it, I mean—has hammered me into shape.”

“It hasn’t made you despondent, though.”

“And it never will,” said Conniston, emphatically, “until I meet with the woman who refuses to marry me. Then I’ll howl.”

“You haven’t met the woman yet?”

“No. But you have. I can see it in the telltale blush. Bless me, old Gore, how boyish you are. I haven’t blushed for years.”

“You hardened sinner. Yes! There is a woman, and she is the cause of my trouble.”

“The usual case,” said the worldly-wise Richard. “Who is she?”

“Her name is Alice,” said Gore, slowly, his eyes on the damp grass.

“A pretty unromantic, domestic name. ‘Don’t you remember sweet Alice, Ben Bolt?’“

“I’m always remembering her,” said Gore, angrily. “Don’t quote that song, Dick. I used to sing it to her. Poor Alice.”

“What’s her other name?”

“Malleson—Alice Malleson!”

“Great Scott!” said Conniston, his jaw falling. “The niece of Miss Berengaria Plantagenet?”

“Yes! Do you know—?” Here Gore broke off, annoyed with himself. “Of course. How could I forget? Miss Plantagenet is your aunt.”

“My rich aunt, who could leave me five thousand a year if she’d only die. But I daresay she’ll leave it to Alice with the light-brown hair, and you’ll marry her.”

“Conniston, don’t be an ass. If you know the story of Miss Malleson’s life, you must know that there isn’t the slightest chance of her inheriting the money.”

“Ah, but, you see, Bernard, I don’t know the story.”

“You know Miss Plantagenet. She sometimes talks of you.”

“How good of her, seeing that I’ve hardly been in her company for the last ten years. I remember going to “The Bower” when a small boy, and making myself ill with plums in a most delightful kitchen garden. I was scolded by a wonderful old lady as small as a fairy and rather like one in looks—a regular bad fairy.”

“No! no. She is very kind.”

“She wasn’t to me,” confessed Conniston; “but I daresay she will have more respect for me now that I’m the head of the family. Lord! to think of that old woman’s money.”

“Conniston, she would be angry if she knew you had enlisted. She is so proud of her birth and of her connection with the Wests. Why don’t you call and tell her—”

“No, indeed. I’ll do nothing of the sort. And don’t you say a word either, Bernard. I’m going to carve out my own fortune. I don’t want money seasoned with advice from that old cat.”

“She is not an old cat!”

“She must be, for she wasn’t a kitten when I saw her years ago. But about Miss Malleson. Who is she? I know she’s Miss Plantagenet’s niece. But who is she?”

“She is not the niece—only an adopted one. She has been with Miss Plantagenet for the last nine years, and came from a French convent. Miss Plantagenet treats her like a niece, but it is an understood thing that Alice is to receive no money.”

“That looks promising for me,” said Conniston, pulling his mustache, “but my old aunt is so healthy that I’ll be gray in the head before I get a cent. So you’ve fallen in love with Alice?”

“Yes,” sighed Gore, drawing figures with his cane. “I love her dearly and she loves me. But my grandfather objects. I insisted upon marrying Alice, so he cut me off with a shilling. I expect the money will go to my cousin, Julius Beryl, and, like you, I’ll have to content myself with a barren title.”

“But why is Sir Simon so hard, Gore?”

Bernard frowned again. “Do you notice how dark I am?” he asked.

“Yes! You have rather an Italian look.”

“That’s clever of you, Dick. My mother was Italian, the daughter of a noble Florentine family; but in England was nothing but a poor governess. My father married her, and Sir Simon—his father—cut him off. Then when my parents died, my grandfather sent for me, and brought me up. We have never been good friends,” sighed Bernard again, “and when I wanted to marry Alice there was a row. I fear I lost my temper. You know from my mother I inherit a fearful temper, nor do I think the Gores are the calmest of people. However, Sir Simon swore that he wouldn’t have another mésalliance in the family and—”

“Mésalliance?”

“Yes! No one knows who Alice is, and Miss Plantagenet—who does know—won’t tell.”

“You said no one knew, and now you say Miss Plantagenet does,” said Conniston, laughing. “You’re getting mixed, Bernard. Well, so you and Sir Simon had a row?”

“A royal row. He ordered me out of the house. I fear I said things to him I should not have said, but my blood was boiling at the insults he heaped on Alice. And you know Sir Simon is a miser. My extravagance—though I really wasn’t very extravagant—might have done something to get his back up. However, the row came off, and I was turned away. I came to town, and could see nothing better to do than enlist, so I have been in the Yeomanry for the last four months, and have managed to reach the rank of corporal. I go out to the war soon.”

“We’ll go together,” said Conniston, brightening, “and then when you come back covered with glory, Sir Simon—”

“No. He won’t relent unless I give up Alice, and that I will not do. What does it matter if Alice is nameless? I love her, and that is enough for me!”

“And too much for your grandfather, evidently. But what about that cousin of yours, you used to talk of? Lucy something—”

“Lucy Randolph. Oh, she’s a dear little girl, and has been an angel. She is trying to soothe Sir Simon, and all through has stood my friend. I made her promise that she would put a lamp in the Red Window when Sir Simon relented—if he ever does relent.”

Conniston looked puzzled. “The Red Window?”

“Ah! You don’t know the legend of the Red Window. There is a window of that sort at the Hall, which was used during the Parliamentary wars to advise loyal cavaliers of danger. It commands a long prospect down the side avenue. The story is too long to tell you. But, you see, Conniston, I can’t get near the house, and my only chance of knowing if Sir Simon is better disposed towards me is by looking from the outside of the park up to the Red Window. If this shows a red light I know that he is relenting; if not, he is still angry. I have been once or twice to the Hall,” said Gore, shaking his head, “but no light has been shown.”

“What a roundabout way of letting you know things. Can’t Lucy write?”

Gore shook his head again. “No. You see, she is engaged to Julius, who hates me.”

“Oh, that Beryl man. He comes in for the money?”

“Now that I’m chucked I suppose he will,” said Bernard, gloomily; “and I don’t want to get poor Lucy into his black books, as he isn’t a nice sort of chap. He won’t thank her if she tries to bias the old man in my favor. And then there’s the housekeeper who doesn’t like me—Mrs. Gilroy her name is. She and Julius will both keep Sir Simon’s temper alive. I can’t write to him, or my letter would be intercepted and destroyed by Mrs. Gilroy. Lucy can’t write me because of Julius, so my only chance of knowing if the old man is thinking better of his determination is by watching for the red light. I shall go down again twice before I leave for Africa.”

“And if you see the red light you won’t stick to soldiering?”

“Yes, I will. But I’ll then walk boldly up to the Hall and tell Sir Simon how sorry I am. But in any case I intend to fight for my country. Alice herself wouldn’t ask me to be a coward and leave. I go to the Cape with you, Conniston,” said Bernard, rising.

“Good old chap,” said Conniston, delighted, “you’re the only fellow I’d care to chum up with. I have often thought of you since we parted. But you rarely wrote to me.”

“You were the better correspondent, I admit,” said Gore, as they walked across the bridge. “I am ashamed I did not continue our school friendship, as we always were such chums, but—”

“The inevitable woman. Ah, Delilah always comes between David and Jonathan.”

“Don’t call Alice by that name!” fired up Gore.

“Well, then, I won’t. But don’t get in a wax. What a fire-brand you are, Gore! Just as fierce as you were at school.”

“Yes,” said Bernard, quieting down. “I only hope my bad temper will not ruin me some day. I tell you, Conniston, when Sir Simon pitched into me I felt inclined to throw something at his head. He was most insulting. I didn’t mind what he said about me, but when he began to slang Alice I told him I’d pitch him out of the window if he didn’t stop. And I said many other foolish things.”

“Shouldn’t do that. He’s an old man.”

“I know—I know. I was a fool. But you have no idea how readily my temper gets the better of me. I could strangle anyone who said a word against my Alice.”

“Well, don’t strangle me,” said Conniston, laughing. “I won’t call her Delilah again, I promise you. But about your Red Window business—you needn’t go down to the Hall for a week or so.”

“Why not?”

“Because Sir Simon is in town.”

“Nonsense. He never comes to town.”

“He has this time. Queerly enough, his lawyers are mine. I saw him at the office and asked who he was. Durham, my lawyer friend, told me.”

“How long ago was that?”

“Three days. I came up on business, and was in plains!”

“Plains?”

“What! you a soldier and don’t know plain clothes are called so. You are an old ass, Bernard. But, I say, I’ve got digs of a sort hereabouts. Come and dine with me to-night.”

“But I haven’t any dress clothes. I got rid of them, thinking I was going to the Cape sooner.”

“Then come in khaki. You look A 1 in it. Here’s the address,” and Conniston hastily scribbled something on his card. “I shall expect you at seven.”

The two friends parted with a hearty handshake, and Gore walked away feeling happier than he had been. Conniston, gazing after him, felt a tug at his coat. He looked down, and saw a small boy. “Judas,” said Conniston, “you young brute! How did you know me?”

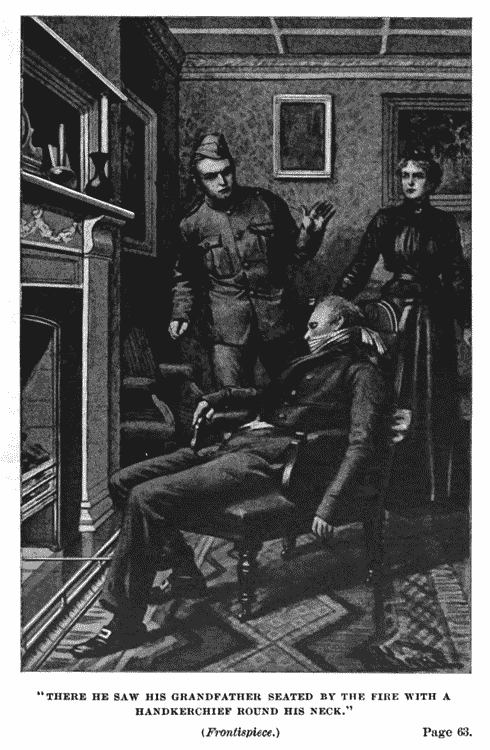

Avarice, according to Byron, is a gentlemanly vice appertaining to old age. It certainly acted like Aaron’s rod with Sir Simon, as it swallowed up all his more youthful sins. During the early part of the Victorian epoch, the old man had been a spendthrift and a rake. Now, he never looked agreeably upon a woman, and the prettier they were the more he frowned upon them. As he was close upon eighty, it was not to be wondered at that his blood ran thin and cold; still, he might have retained the courtesy for which he was famous in his hot youth. But he eschewed female society in the main, and was barely civil to his pretty, fascinating niece, who attended to him and bore with his ill-humors. Only Mrs. Gilroy succeeded in extorting civil words from him, but then Mrs. Gilroy was necessary to his comfort, being a capital nurse and as quiet as a cat about the house. Where his own pleasure was concerned Sir Simon could be artful.

Long ago he had given up luxury. He never put liquor to his withered lips, he ate only the plainest food, and surrounded himself with merely the bare necessities of life. All his aims were to gather money, to see it increase, to buy land, to screw the last penny out of unwilling tenants, and to pick up a farthing, in whatever mud it might be lying. He never helped the poor, he grudged repairs to the property, he kept Lucy on short commons, and expressed such violent opinions concerning the rector’s tithes that the poor man was afraid to come near him. As Sir Simon, like a godless old pagan, never went to church, the absence of the clerical element at the Hall troubled him little. He was a typical miser in looks, being bent, withered and dry. As a young man he had bought, in his spendthrift days, a great number of suits, and these he was wearing out in his old age. The garments, once fashionable, looked queer in the eyes of a younger generation; but Sir Simon minded no one. He was always scrupulously dressed in his antique garb, and looked, as the saying goes, as neat as a new pin. His health was tolerable, although he suffered from rheumatism and a constant cough. Owing to his total abstinence, he was free from gout, but could not have been worse tempered had he indeed suffered, as he assuredly deserved to. With his withered skin, his thin, high nose, his pinched features and his bent form he looked anything but agreeable. When walking he supported himself with an ebony cane, and had been known on occasions to use it on the backs of underlings. From this practice, however, he had desisted, since the underlings, forgetful of the feudal system, brought actions for assault, which resulted in Sir Simon losing money. As the old Baronet said, radical opinions were ruining the country; for why should the lower orders not submit to the stick?

It was rarely that this agreeable old gentleman came to town. He lived at the Hall in Essex in savage seclusion, and there ruled over a diminished household with a rod of iron. Mrs. Gilroy, who had been with him for many years, was—outwardly—as penurious as her master, so he trusted her as much as he trusted anyone. What between the grim old man and the silent housekeeper, poor Lucy Randolph, who was only a connection, had a dreary time. But then, as the daughter of Sir Simon’s niece, she was regarded as an interloper, and the old man grumbled at having to support poor relations. Bernard he had tolerated as his heir, Lucy he frankly disliked as a caterpillar. Often would he call her this name.

As usual, Sir Simon came to town with the least expense to himself, since it agonized him to spend a penny. But an old friend of his, more open-handed than the baronet, had lent him his town house. This was a small residence in a quiet Kensington square, by no means fashionable. The central gardens, surrounded by rusty iron railings, were devoid of flowers and filled with ragged elms and sycamores, suffered to grow amidst rank grass untrimmed and unattended. The roads around were green with weeds, and the houses appeared to be deserted. Indeed, many of them were, as few people cared to live in so dull a neighborhood; but others were occupied by elderly folk, who loved the quietness and retirement. Crimea square—its name hinted at its age—was a kind of backwater into which drifted human derelicts. A few yards away the main thoroughfare roared with life and pulsed with vitality, but the dwellers in the square lived as in the enchanted wood of the sleeping beauty.

No. 32 was the house occupied by Sir Simon, and it was distinguished from its neighbors by a coat of white paint. Its spurious, smart air was quite out of keeping with the neighborhood, and Sir Simon made ironical remarks when he saw its attempt at being up-to-date. But the house was small, and, although furnished in a gimcrack way, was good enough for a month’s residence. Moreover, since he paid no rent, this enhanced its value in his avaricious eyes. It may be mentioned that the servants of the owner—a cook, a housemaid and a pageboy—had stopped on to oblige Sir Simon, and were ruled over by Mrs. Gilroy, much to their disgust. The housekeeper was by no means a pleasant mistress, and turned their intended holiday into a time of particularly hard work.

It was about the servants that Mrs. Gilroy spoke to her master one morning shortly after the occupation of the house. Sir Simon, accurately dressed as usual, and looking like a character out of Dickens as delineated by Phiz, was seated beside a comfortable fire supping a cup of plasmon cocoa, as containing the most nutriment in the least expensive form. While enjoying it, he mentally calculated various sums owing from various tenants about which he had come to see his lawyers.

The room was of no great size, on the ground floor, and had but two windows, which looked out on the dreary, untidy gardens. Like the exterior of the house, it had been newly painted and decorated, and was also furnished in a cheap way with chairs and tables, sofas and cabinets attractive to the uneducated eye, but detestable to anyone who could appreciate art. The scheme of color was garish, and, but that the blinds were pulled half-way down, so as to exclude too searching a light, would have jarred on Sir Simon’s nerves. Lucy Randolph, who sat reading near the window, shuddered at the newness and veneer of her surroundings and thought regretfully of the lovely, mellow old Hall, where everything was in keeping and hallowed by antiquity. All the same, this too brilliantly-cheap room was cosy and comfortable, bright and cheery, and a pleasing contrast to the foggy, gray, damp weather. Perhaps it was this contrast which its decorator had desired to secure.

Mrs. Gilroy, with folded hands, stood at her master’s elbow, a tall, thin, silent, demure woman with downcast eyes. Plainly dressed in black silk, somewhat worn, and with carefully-mended lace, she looked like a lady who had seen better days. Her hair, and eyes, and skin, and lips, were all of a drab color, by no means pleasing, and she moved with the stealthy step of a cat. Indeed, the servants openly expressed their opinion that she was one, and she certainly had a somewhat feline look. But, with all her softness and nun-like meekness, an occasional glance from her light eyes showed that she could scratch when necessary. No one knew who she was or where she came from, but she looked like a woman with a history. What that was only she and Sir Simon knew, and neither was communicative. Lucy Randolph hated her, and indeed no love was lost between the two. Mrs. Gilroy looked on Lucy as a pauper living on Sir Simon’s charity, and Miss Randolph regarded the silent housekeeper as a spy. Each annoyed the other on every occasion in that skilful way known to the sex. But the war was carried on out of the old man’s sight. That autocrat would speedily have put an end to it had they dared to skirmish in his presence.

“Well! well! well!” snapped Sir Simon, who talked something like George III. in reiterating his words. “What’s the matter? What?”

“I have to complain of the housemaid Jane, sir.”

“Then don’t. I pay you to keep the servants quiet, not to bother me with their goings-on. Well! well! well!” somewhat inconsistently, “what’s Jane been doing?”

“Receiving a follower—a soldier—one of those new young men who are going to the war.”

“An Imperial Yeoman?” put in Miss Randolph, looking up with interest.

“Yes, Miss,” responded Mrs. Gilroy, not looking round. “Cook tells me the young man comes nearly every evening, and makes love to Jane!”

“What! what!” said the baronet, setting down his cup irritably. “Tell the hussy to go at once. Love?” This in a tone of scorn. “As though I’ve not had enough worry over that with Bernard. Tell her to go.”

Mrs. Gilroy shook her head. “We can’t dismiss her, sir. She belongs to the house, and Mr. Jeffrey”—

“I’ll see him about it later. If he knew he certainly would not allow such things. A soldier—eh—what? Turn him out, Gilroy, turn him out! Won’t have it, won’t have him! There! you can go.”

“Will you be out to-day, sir?”

“Yes, I go to see my lawyers. Do you think I come to town to waste time, Gilroy? Go away.”

But the housekeeper did not seem eager to go. She cast a look on Lucy eloquent of a desire to be alone with Sir Simon. That look Lucy took no notice of, although she understood it plainly. She suspected Mrs. Gilroy of hating Julius Beryl and of favoring Bernard. Consequently, all the influence of Mrs. Gilroy would be put forth to help the exiled heir. Lucy was fond of Bernard, but she was engaged to Julius, and, dragged both ways by liking and duty, she was forced to a great extent to remain neutral. But she did not intend to let Mrs. Gilroy have the honor and glory of bringing Bernard back to the Hall. Therefore she kept her seat by the window and her eyes on her book. Mrs. Gilroy tightened her thin lips and accepted defeat, for the moment. A ring at the door gave her an excuse to go.

“It’s Julius,” said Lucy, peeping out.

“What does he want?” asked Sir Simon, crossly. “Tell him to wait, Gilroy. I can’t see him at once. Lucy, stop here, I want to speak.”

The housekeeper left the room to detain Mr. Beryl, and Lucy obediently resumed her seat. She was a handsome, dark girl, with rather a high color and a temper to match. But she knew when she was well off and kept her temper in check for fear of Sir Simon turning her adrift. He would have done so without scruple had it suited him. Lucy was therefore astute and assumed a meekness she was far from possessing. Mrs. Gilroy saw through her, but Lucy—as the saying goes—pulled the wool over the old man’s eyes.

Sir Simon took a turn up and down the room. “What about Bernard?” he asked, abruptly stopping before her.

Lucy looked up with an innocent smile. “Dear Bernard!” she said.

“Do you know where he is?” asked the baronet, taking no notice of the sweet smile and sweet speech.

“No, he has not written to me.”

“But he has to that girl. You know her?”

“Alice! yes, but Alice doesn’t like me. She refuses to speak to me about Bernard. You see,” said Lucy, pensively, “I am engaged to Julius, and as you have sent Bernard away—”

“Julius comes in for my money, is that it?”

“Not in my opinion,” said Miss Randolph, frankly, “but Alice Malleson thinks so.”

“Then she thinks rightly.” Lucy started at this and colored with surprise at the outspoken speech. “Since Bernard has behaved so badly, Julius shall be my heir. The one can have the title, the other the money. All the same I don’t want Bernard to starve. I daresay Julius knows where he is, Lucy. Find out, and then I can send the boy something to go on with.”

“Oh!” said Lucy, starting to her feet and clasping her hands, “the Red Window,—I mean.”

“I should very much like to know what you do mean,” said Sir Simon, eyeing her. “The Red Window! Are you thinking of that ridiculous old legend of Sir Aymas and the ghost?”

“Yes,” assented Miss Randolph, “and of Bernard also.”

“What has he to do with the matter?”

“He asked me, if you showed any signs of relenting, to put a light in the Red Window at the Hall. Then he would come back.”

“Oh!” Sir Simon did not seem to be displeased. “Then you can put the light in the window when we go back in three weeks.”

“You will forgive him?”

“I don’t say that. But I want to see him settled in some reputable way. After all,” added the old man, sitting down, “I have been hard on the boy. He is young, and, like all fools, has fallen in love with a pretty face. This Miss Malleson—if she has any right to a name at all—is not the bride I should have chosen for Bernard. Now you, my dear Lucy—”

“I am engaged to Julius,” she interposed quickly, and came towards the fire. “I love Julius.”

“Hum! there’s no accounting for tastes. I think Bernard is the better of the two.”

“Bernard has always been a trouble,” said Lucy, “and Julius has never given you a moment’s uneasiness.”

“Hum,” said Sir Simon again, his eyes fixed on the fire. “I don’t believe Julius is so good as you make him out to be. Now Bernard—”

“Uncle,” said Lucy, who had long ago been instructed to call her relative by this name, “why don’t you make it up with Bernard? I assure you Julius is so good, he doesn’t want to have the money.”

“And you?” The old man looked at her sharply.

“I don’t either. Julius has his own little income, and earns enough as an architect to live very comfortably. Let me marry Julius, dear uncle, and we will be happy. Then you can take back Bernard and let him marry dear, sweet Alice.”

“I doubt one woman when she praises another,” said Sir Simon, dryly. “Alice may be very agreeable.”

“She is beautiful and clever.”

The baronet looked keenly at Lucy’s flushed face, trying to fathom her reason for praising the other woman. He failed, for Miss Randolph’s face was as innocent as that of a child. “She is no doubt a paragon, my dear,” he said; “but I won’t have her marry Bernard. By this time the young fool must have come to his senses. Find out from Julius where he is, and—”

“Julius may not know!”

“If Julius wants my money he will keep an eye on Bernard.”

“So as to keep Bernard away,” said Lucy, impetuously. “Ah, uncle, how can you? Julius doesn’t want the money—”

“You don’t know that.”

“Ask him yourself then.”

“I will.” Sir Simon rang the bell to intimate to Mrs. Gilroy that Julius could be shown up. “If he doesn’t want it, of course I can leave it to someone else.”

“To Bernard.”

“Perhaps. And yet I don’t know,” fumed Sir Simon. “The rascal defied me! He offered to pitch me out of the window if I said a word against that Alice of his. I want Bernard to marry you—”

“I am engaged to Julius.”

“So you said before,” snapped the other. “Well, then, Miss Perry. She is an heiress.”

“And as plain as Alice is handsome.”

“What does that matter? She is good-tempered. However, it doesn’t matter. I won’t be friends with Bernard unless he does what I tell him. He must give up Alice and marry Miss Perry. Try the Red Window scheme when you go back to the Hall, Lucy. It will bring Bernard to see me, as you say.”

“It will,” said Lucy, but by no means willingly. “Bernard comes down at times to the Hall to watch for the light. But I can make a Red Window here.”

“Bernard doesn’t know the house.”

“I am sure he does,” said Lucy. “He has to go to the lawyers for what little money he inherits from his father, and Mr. Durham may have told him you are here. Then if I put the light behind a red piece of paper or chintz, Bernard will come here.”

“It is all romantic rubbish,” grumbled the old man, warming his hands. “But do what you like, child. I want to give Bernard a last chance.” At this moment Julius appeared. He was a slim young man with a mild face, rather expressionless. His hair and eyes were brown. He was irreproachably dressed, and did not appear to have much brain power. Also, from the expression of his eyes he was of a sly nature. Finally, Mr. Beryl was guarded in his speech, being quite of the opinion that speech was given to hide thoughts. He saluted his uncle affectionately, kissed Lucy’s cheek in a cold way, and sat down to observe what a damp, dull day it was and how bad for Sir Simon’s rheumatism. A more colorless, timid, meek young saint it would have been hard to find in the whole of London.

“I have brought you some special snuff,” he said, extending a packet to his host. “It comes from Taberley’s.”

“Ah, thank you. I know the shop. A very good one! Do you get your cigars there, Julius?”

“I never smoke,” corrected the good young man, coldly.

Sir Simon sneered. “You never do anything manly,” he said contemptuously. “Well, why are you here?”

“I wish, with your permission, to take Lucy to the theatre on Friday,” said Mr. Beryl. “Mrs. Webber is going with me, and she can act as chaperon.”

“I should think she needed one herself. A nasty, flirting little cat of a woman,” said Sir Simon, rudely. “Would you like to go, Lucy?”

“If you don’t mind, uncle.”

“Bah!” said the old man with a snarl. “How good you two are. Where is the theatre, Julius?”

“Near at hand. The Curtain Theatre.”

“Ah! That’s only two streets away. What is the play?”

“As You Like It, by—”

“By Chaucer, I suppose,” snapped the old man. “Don’t you think I know my Shakespeare? What time will you call for Lucy?”

“At half-past seven in the carriage with Mrs. Webber.”

“Your own carriage?”

“I am not rich enough to afford one,” said Julius, smiling. “Mrs. Webber’s carriage, uncle. We will call for Lucy and bring her back safely at eleven or thereabouts.”

“Very good; but no suppers, mind. I don’t approve of Mrs. Webber taking Lucy to the Cecil or the Savoy.”

“There is no danger of that, uncle,” said Lucy, delighted at gaining permission.

“I hope not,” said the old man ungraciously. “You can go, Lucy. I want to speak to Julius.”

A look, unseen by the baronet, passed between the two, and then Lucy left the room. When alone, Sir Simon turned to his nephew. “Where is Bernard?” he asked.

A less clever man than Julius would have fenced and feigned surprise, but this astute young gentleman answered at once. “He has enlisted in the Imperial Yeomanry and goes out to the war in a month.”

Sir Simon turned pale and rose. “He must not—he must not,” he said, considerably agitated. “He will be killed, and then—”

“What does it matter?” said Julius coolly—“you have disinherited him—at least, I understand so.”

“He defied me,” shivered the baronet, warming his hands again and with a pale face; “but I did not think he would enlist. I won’t have him go to the war. He must be bought out.”

“I think he would refuse to be bought out now,” said Beryl, dryly. “I don’t fancy Bernard, whatever his faults, is a coward.”

“My poor boy!” said Sir Simon, who was less hard than he looked. “It is your fault that this has happened, Julius.”

“Mine, uncle?”

“Yes. You told me about Miss Malleson.”

“I knew you would not approve of the match,” said Julius, quietly.

“And you wanted me to cut off Bernard with a shilling—”

“Not for my own sake,” said Julius, calmly. “You need not leave a penny to me, Sir Simon.”

“Don’t you want the money? It’s ten thousand a year.”

“I should like it very much,” assented Beryl, frankly; “but I do not want it at the price of my self-respect.”

The old man looked at him piercingly, but could learn nothing from his inscrutable countenance. But he did not trust Julius in spite of his meek looks, and inwardly resolved to meet craft by craft. He bore a grudge against this young man for having brought about the banishment of his grandson, and felt inclined to punish him. Yet if Julius did not want the money, Sir Simon did not know how to wound him. Yet he doubted if Julius scorned wealth so much as he pretended; therefore he arranged how to circumvent him.

“Very well,” he said, “since Bernard has disobeyed me, you alone can be my heir. You will have the money without any loss of your self-respect. Come with me this morning to see Durham.”

“I am at your service, uncle,” said Julius, quietly, although his eyes flashed. “But Bernard?”

“We can talk of him later. Come!”

The attentive Beryl helped Sir Simon on with his overcoat and wrapped a muffler round his throat. Then he went out to select a special four-wheeler instead of sending the page-boy. When he was absent, Mrs. Gilroy appeared in the hall where Sir Simon waited, and, seeing he was alone, came close to him.

“Sir,” she said quietly, “this girl Jane has described the young man’s looks who comes to see her.”

“Well! well! well!”

“The young man—the soldier,” said Mrs. Gilroy, with emphasis—“has come only since we arrived here. Jane met him a week before our arrival, and since we have been in the house this soldier has visited her often.”

“What has all this to do with me?” asked Sir Simon.

“Because she described the looks of the soldier. Miss Randolph says he is an Imperial Yeoman.”

Sir Simon started. “Has Miss Randolph seen him?” he asked.

“No. She only goes by what I said this morning to you. But the description, Sir Simon—” Here Mrs. Gilroy sank her voice to a whisper and looked around—“suits Mr. Gore.”

“Bernard! Ah!” Sir Simon caught hold of a chair to steady himself. “Why—what—yes. Julius said he was an Imperial Yeoman and—”

“And he comes here to see the housemaid,” said Mrs. Gilroy, nodding.

“To spy out the land,” cried the baronet, in a rage. “Do you think that my grandson would condescend to housemaids? He comes to learn how I am disposed—if I am ill. The money—the money—all self—self—self!” He clenched his hand as the front door opened. “Good-bye, Mrs. Gilroy, if you see this Imperial Yeoman, say I am making a new will,” and with a sneer Sir Simon went out.

Mrs. Gilroy looked up to heaven and caught sight of Lucy listening on the stairs.

Mr. Durham was a smart young lawyer of the new school. The business was an old one and lucrative; but while its present owner was still under thirty, his father died and he was left solely in charge. Wiseacres prophesied that, unguided by the shrewdness of the old solicitor, Durham junior, would lose the greater part, if not all, of his clients. But the young man had an old head on young shoulders. He was clever and hard-worked, and, moreover, possessed a great amount of tact. The result was that he not only retained the old clients of the firm, but secured new ones, and under his sway the business was more flourishing than ever. Also Mark Durham did not neglect social duties, and by his charm of manner, backed by undeniable business qualities, he managed to pick up many wealthy clients while enjoying himself. He always had an eye to the main chance, and mingled business judiciously with sober pleasures.

The office of Durham & Son—the firm still retained the old title although the son alone owned the business—was near Chancery Lane, a large, antique house which had been the residence of a noble during the reign of the Georges. The rooms were nobly proportioned, their ceilings painted and decorated, and attached to the railings which guarded the front of the house could still be seen the extinguishers into which servants had thrust torches in the times they lighted belles and beaux to splendid sedan chairs. A plate on the front intimated that a famous author had lived and died within the walls; so Durham & Son were housed in a way not unbecoming to the dignity of the firm. Mr. Durham’s own room overlooked a large square filled with ancient trees, and was both well-furnished and well-lighted. Into this Sir Simon and his nephew were ushered, and here they were greeted by the young lawyer.

“I hope I see you well, Sir Simon?” said Durham, shaking hands. He was a smart, well-dressed, handsome young fellow with an up-to-date air, and formed a striking contrast to the baronet in his antique garb. As the solicitor spoke he cast a side glance at Beryl, whom he knew slightly, and he mentally wondered why the old man had brought him along. Sir Simon had never spoken very well of Julius, but then he rarely said a good word of anyone.

“I am as well as can be expected,” said Sir Simon, grumpily, taking his seat near the table, which was covered with books, and papers, and briefs, and red tape, and all the paraphernalia of legal affairs. “About that will of mine—”

“Yes?” inquired Durham, sitting, with another glance at Beryl, and still more perplexed as to the baronet’s motive for bringing the young man. “I have had it drawn out in accordance with your instructions. It is ready for signing.”

“Read it.”

“In the presence of—” Durham indicated Beryl in a puzzled way.

“I can go, uncle, if you wish,” said Julius, hastily, and rose.

“Sit down!” commanded the old man. “You are interested in the will.”

“All the more reason I should not hear it read,” said Julius, still on his feet.

Sir Simon shrugged his shoulders and turned his back on his too particular nephew. “Get the will, Durham, and read it.”

It was not the lawyer’s business to argue in this especial instance, so he speedily summoned a clerk. The will was brought, carefully engrossed on parchment, and Durham rustled the great sheets as he resumed his seat. “You wish me to read it all?” he asked hesitatingly.

Sir Simon nodded, and, leaning his chin on the knob of his cane, disposed himself to listen. Beryl could not suppress an uneasy movement, which did not escape his uncle’s notice, and he smiled in a grim way. Durham, without further preamble, read the contents of the will, clearly and deliberately, without as much as a glance in the direction of the person interested. This was Julius, and he grew pale with pleasure as the lawyer proceeded.

The will provided legacies for old servants, but no mention was made of Mrs. Gilroy, a fact which Beryl noted and secretly wondered at. Various bequests were made to former friends, and arrangements set forth as to the administration of the estate. The bulk of the property was left to Julius Beryl on condition that he married Lucy Randolph, for whom otherwise no provision was made. The name of Bernard Gore was left out altogether. When Durham ended he laid down the will with a rather regretful air, and discreetly stared at the fire. He liked young Gore and did not care for the architect. Therefore he was annoyed that the latter should benefit to the exclusion of the former.

“Good!” said Sir Simon, who had followed the reading with close attention. “Well?” he asked his nephew.

Beryl stammered. “I hardly know how to thank you. I am not worthy—”

“There—there—there!” said the old man tartly. “We understand all that. Can you suggest any alteration?”

“No, uncle. The will is perfect.”

“What do you think, Durham?” said Gore, with a dry chuckle.

“I think,” said the lawyer, his eyes still on the fire, “that some provision should be made for your grandson. He has been taught to consider himself your heir, and has been brought up in that expectation. It is hard that, at his age, he should be thrown on the world for—”

“For disobedience,” put in Beryl, meekly.

Sir Simon chuckled again. “Yes, for disobedience. You are not aware, Durham, that Bernard wants to marry a girl who has no name and no parents, and no money—the companion of a crabbed old cat called Miss Plantagenet.”

“I know,” said the young lawyer, nodding. “She is the aunt of Lord Conniston, who told me about the matter.”

“I thought Lord Conniston was in America,” said Julius, sharply.

“I saw him before he went to America,” retorted the solicitor, who did not intend to tell Beryl that Conniston had been in his office on the previous day. “Why do you say that? Do you know him?”

“I know that he has a castle near my uncle’s place.”

“Cove Castle,” snapped Sir Simon. “All the county knows that. But he never comes near the place. Did you meet Lord Conniston at Miss Plantagenet’s, Julius?”

“I have never met him at all,” rejoined the meek young man stiffly, “and I have been to Miss Plantagenet’s only in the company of Bernard.”

“Aha!” chuckled Sir Simon. “You did not fall in love with that girl?”

“No, uncle. Of course I am engaged to Miss Randolph.”

“You can call her ‘Lucy’ to a near relative like myself,” said the baronet, dryly. “Do you know Miss Malleson, Durham?”

“No. I have not that pleasure.”

“But no doubt Bernard has told you about her.”

Durham shook his head. “I have not seen Gore for months.”

“Are you sure? He inherits a little money from his father; and you—”

“Yes! I quite understand. I have charge of that money. Gore came a few months ago, and I gave him fifty pounds or so. That was after he quarrelled with you, Sir Simon. Since then I have not seen him.”

“Then he does not know that I am in Crimea Square.”

“Not that I know of. Certainly not from me. Is he in town?”

It was Beryl who answered this. “Bernard has enlisted as an Imperial Yeoman,” said he.

“Then I think the more of him,” said Durham quickly. “Every man who can, should go to the Front.”

“Why don’t you go yourself, Durham?”

“If I had not my business to look after I certainly should,” replied the lawyer. “But regarding Mr. Gore. Will you make any provision for him, Sir Simon?”

“I can’t say. He deserves nothing. I leave it to Julius.”

“Should the money come into my possession soon,” said Julius, virtuously, “a thing I do not wish, since it means your death, dear uncle, I should certainly allow Bernard two hundred a year.”

“Out of ten thousand,” put in Durham. “How good of you!”

“He deserves no more for his disobedience to his benefactor.”

Sir Simon chuckled yet again. “I am quite of Julius’s opinion,” he declared. “Bernard has behaved shamefully. I wanted him to marry a Miss Perry, who is rich.”

“Why can’t you let him marry the woman he loves?” said Durham, with some heat. “They can live on ten thousand a year and be happy. What is the use of getting more money than is needed? Besides, from what I hear, this Miss Malleson is a charming girl.”

“With no name and no position,” said Sir Simon, “a mere paid companion. I don’t want my grandson to make such a bad match. If he does, he must take the consequences. And he will—”

“Certainly he will,” said Beryl, anxious about the signing of the will. “He has been hard-hearted for months, and shows no signs of giving in. Since I am to inherit the money I will allow Bernard two hundred a year, or such sum as Sir Simon thinks fit.”

“Two hundred is quite enough,” said the baronet. “Mr. Durham, we will see now about signing this will.”

“Can I not persuade you to—”

“No! You can’t persuade me to do anything but what I have done. I am sure Julius here will make a better use of the money than Bernard will. Won’t you, Julius?”

“I hope so,” replied Beryl, rising; “but I trust it will be many a long day before I inherit the money, dear uncle.”

“Make your mind easy,” said Sir Simon, dryly. “I intend to live for many a year yet.”

“I think I had better go now,” observed Julius, rising.

“Won’t you stop and see the will signed?”

“No, uncle. I think it is better, as I inherit, that I should be out of the room. Who knows but what Bernard might say, did I remain, that I exercised undue influence?”

“Not while I am present,” said Durham, touching a bell.

“All the same I had better go,” insisted the young man. “Uncle?”

“Please yourself,” replied Gore. “You can go if you like. I shall see you on Friday when you come for Lucy.”

“To take her to the Curtain Theatre. Yes! But I trust I will see you before then, uncle.” And here, as a clerk entered the room and was apparently, with Durham, about to witness the will, Julius departed. He chuckled to himself when he was outside, thinking of his good luck. But at the door his face altered. “He might change his mind,” thought Beryl. “There’s no reliance to be placed on him. I wish—” he opened and shut his fist; “but he won’t die for a long time.”

While Julius was indulging in these thoughts, Sir Simon had taken up the will to glance over it. He also requested Durham to send the clerk away for a few moments. Rather surprised, the lawyer did so, thinking the old man changeable. When alone with his legal adviser the baronet walked to the fire and thrust the will into it. Durham could not forbear an ejaculation of surprise, “What’s that for?”

“To punish Julius,” said Sir Simon, placidly returning to his seat, as though he had done nothing out of the way. “He is a mean sneak. He told me about Bernard being in love with that girl so as to create trouble.”

“But you don’t approve of the match?”

“No, I certainly do not, and I daresay that when I insisted on Bernard marrying Miss Perry that the truth would have come out. All the same it was none of Beryl’s business to make mischief. Besides, he is a sly creature, and if I made the will in his favor, who knows but what he might not contrive to get me out of the way?”

“No,” said Durham, thoughtfully, but well pleased for Bernard’s sake that the will had been destroyed. “I don’t think he has courage to do that. Besides, people don’t murder nowadays.”

“Don’t they?” said Sir Simon; “look in the newspapers.”

“I mean that what you think Julius might do is worthy of a novel. I don’t fancy novels are true to life.”

“Anything Julius did would be just like a novel. I tell you, Durham, he is a villain of the worst; I don’t trust him. I have led him on to think that the will has been made in his favor; and when he learns the truth he will be punished for his greed.”

“But, Sir Simon,” argued the lawyer, “by letting him think the will is made in his favor, you have placed him in the very position which, according to you, might lead to his attempt to murder.”

“I’ll take care of myself,” said the old man, somewhat inconsistently, for certainly he was acting differently to what he said. “By the way, you have the other will?”

“Yes! It leaves everything to Bernard save the legacies, which remain much the same. Of course, in the first will is mentioned an annuity to Mrs. Gilroy.”

“Hum, yes. I left her out of the new will. The fact is, I don’t trust Mrs. Gilroy. She’s too friendly with Julius for my taste.”

“I understood her to be on the side of Bernard.”

“Oh, she’s on whatever side suits her,” said Sir Simon, testily. “However, let the first will stand. She’s a poor thing and has had a hard life. I have every right to leave her something to live on.”

“Why?” asked Durham, bluntly. He found Mrs. Gilroy something of a mystery, and did not know what was the bond between her and Sir Simon.

“Never you mind. I have my reasons, so let things remain as they are. Bernard can marry Miss Malleson when I am dead if he chooses.”

“He thinks he has been disinherited?”

“Yes! I told him so. The truth will come as a pleasant surprise.”

“Won’t you take him back into favor and tell him?” urged Durham.

“No! not at present. If we met, there would only be more trouble. He has a temper inherited from his Italian mother, and I have a temper also. He behaved very rudely to me, and it’s just as well he should suffer a little. But I don’t want him to go to the war. He must be bought out.”

“I fear Bernard is not the man to be bought out.”

“Oh, I know he is brave enough, and I suppose being bought out at the eleventh hour when war is on is not heroic. All the same, I don’t want him to be shot.”

“You must leave things to chance,” said Durham decidedly. “There is only one way in which you can make him give up his soldiering.”

“What’s that?”

“Make friends with him, and ask him to wait till you die.”

“No, no, no!” said Sir Simon, irritably. “He must keep away from me for a time. After all, he is the son of his father, and, bad as Walter was, I loved him for his mother’s sake. As for the Italian woman—”

“Mrs. Gore! She is dead.”

“I know she is. But her brother Guiseppe is alive, and a scoundrel he is. The other day he came to the Hall and tried to force his way into the house. A gambler, a rogue, Durham—that’s what Guiseppe is.”

“What is his other name?”

“Tolomeo! He comes from Siena.”

“I understood Mrs. Gore—your son’s wife—came from Florence.”

“So she said. She declared she was the member of a decayed Florentine family. But afterwards I learned from Guiseppe that the Tolomeo nobles are Sienese—and a bad lot they are. He is a musician, I believe—a plausible scamp. I hope he has not got hold of Bernard.”

“Bernard is his nephew.”

“I know that,” snapped the old man. “All the same, the uncle is sadly in want of money, and would exercise an undue influence over Bernard.”

“I don’t think Gore is the man to be controlled,” said Durham, sagely.

“You don’t know. He is young after all. But you know, by the will, I have put it out of Bernard’s power to assist Tolomeo. If he gives him as much as a shilling the money is lost to him and goes to Lucy.”

“That is rather a hard provision,” said Durham, after a pause.

“I do it for the boy’s good,” replied Gore, rising; “but I must get home now. By the way, about that lease,” and the two began to talk of matters connected with the estate.

Sir Simon after this refused to discuss his erring grandson, but Durham, who was friendly to Bernard, insisted on recurring to the forbidden subject. However it was just when the old man was going that he reverted to the bone of contention, “I wish you would let me tell Bernard that you are well disposed toward him.”

“Ah! you plead for the scamp,” said Sir Simon, angrily.

“Well, I was at Eton with him, you know, and we are great friends. If he is an Imperial Yeoman there will be no difficulty in seeing him.”

“Leave matters as they are. I have ascertained that he won’t go to the war for six weeks. Julius found that out for me, so wait till he is on the eve of sailing. Then we’ll see. If nothing else will keep him at home, I’ll make it up. But I think a little hardship will do him good. He behaved very badly.”

“Bernard is naturally hot tempered.”

“So am I. Therefore, let us keep apart for a time. Who knows what would happen did we meet. No, Durham, let Bernard think that I am still angry. If Lucy sets a lamp in the Red Window that’s a different thing. I shan’t interfere with her romance.”

“The Red Window. What’s that?”

“A silly legend of the Gore family of which you know nothing. I have no time to repeat rubbish. I’ll come and see you again about that lease, Durham. Meanwhile, should Bernard be hard up, help him out of your own pocket. I’ll make it up to you.”

“He wouldn’t accept alms. Besides, he has enough to go on with. I have two hundred of his money in hand.”

“Then I have nothing more to say. I’m sorry the fellow isn’t starving. His conduct to me was shameful.” And Sir Simon went grumbling home.

“All the same, I’ll see Bernard,” thought Durham, returning to his office.

Conniston and Bernard Gore were as much as possible in one another’s company during the stay of the former in town. Thinking he would go out to the Cape sooner than he did, Bernard had impulsively got rid of his civilian clothes, and therefore had to keep constantly to his uniform. But in those days everyone was in khaki, as the war fever was in the air, so amongst the throng he passed comparatively unnoticed. At all events he managed to keep away from the fashionable world, and therefore saw neither Sir Simon nor Lucy. Beyond the fact that his grandfather was in town Bernard knew nothing, and was ignorant that the old man had taken up his abode in Crimea Square. So he told Durham when the lawyer questioned him.

The three old schoolfellows came together at Durham’s house, which was situated on Camden Hill. Faithful to his intention to see Gore, the lawyer had sent a note asking Conniston where Bernard was to be found. Already Conniston had told Durham of his chance meeting in the Park, so when he received Durham’s letter he insisted on taking Gore to dinner at the lawyer’s house. Bernard was only too glad, and the three had a long talk over old times. The dinner was excellent, the wine was good, and although the young man’s housekeeper was rather surprised that her precise master should dine with a couple of soldiers, she did her best to make them comfortable. When the meal was ended Durham carried off his guests to the library, where they sat around a sea-wood fire sipping coffee and smoking the excellent cigars of their host. Durham alone was in evening dress, as Gore kept to khaki, and Conniston, for the sake of company, retained his lancer uniform. Their host laughed as he contemplated the two.

“I feel inclined to go to the front myself,” said he, handing Gore a glass of kümmel, “but the business would suffer.”

“Leave it in charge of a clerk,” said Conniston, in his hair-brained way. “You have no ties to keep you here. Your parents are dead—you aren’t married, and—”

“I may be engaged for all you know.”

“Bosh! There’s a look about an engaged man you can’t mistake. Look at Bernard there. He is—”

“Pax! Pax!” cried Gore, laughing. “Leave me alone, Conniston. But are you really engaged, Mark?”

“No,” said Mark, rubbing his knees rather dismally. “I should like to be. A home-loving man like myself needs a wife to smile at him across the hearth.”

“And just now you talked of going to the front,” put in the young lord. “You don’t know your own mind. But, I say, this is jolly. Back I go to barracks to-morrow and shall remember this comfortable room and this glimpse of civilized life.”

“You were stupid to enlist,” said Durham, sharply. “Had you come to me, we could have arranged matters better. You knew I’d see you through, Conniston. I have ample means.”

“I don’t want to be seen through,” said Conniston, wilfully. “Besides, it’s fun, this war. I’m crazy to go, and now that Bernard’s coming along it will be like a picnic.”

“Not much, I fear,” said Bernard, “if all the tales we hear are true.”

“Right,” said Durham. “This won’t be the military promenade the generality of people suppose it will be. The Boers are obstinate.”

“So are we,” argued Conniston; “but don’t let us talk shop. We’ll get heaps of that at the Cape. Mark, you wanted to see Bernard about some business. Shall I leave the room?”

“No, no!” said Gore, hastily. “Mark can say what he likes about my business before you, Conniston. I have nothing to conceal.”

“Nothing?” asked Durham, looking meaningly at his friend.

Gore allowed an expression of surprise to flit across his expressive face. “What are you driving at, Mark?”

“Well,” said Durham, slowly, “your grandfather came to see me the other day on business—”

“I can guess what the business was,” put in Bernard, bitterly, and thinking that a new will had been made.

The lawyer smiled. “Quite so. But don’t ask me to betray the secrets of my client. But Sir Simon knew you were in the Imperial Yeomanry, Bernard. He learned that from Beryl.”

“Who is, no doubt, spying on me. It is thanks to Julius that I had the row with my grandfather. He—”

“You needn’t trouble to explain,” interrupted Durham. “I know. Sir Simon explained. But he also asked me if you knew he was in town.”

“I told Bernard,” said Conniston, “and you told me.”

“Yes. But does Bernard know where Sir Simon is stopping?”

“No,” said Gore, emphatically, “I don’t.”

“Neither do I. What are you getting at, Mark?”

“It’s a queer thing,” went on Durham, taking no notice of Conniston’s question, “but afterwards—yesterday, in fact—Sir Simon wrote saying that he heard from Mrs. Gilroy of an Imperial Yeoman who had been visiting in the kitchen of Crimea Square—”

“What about Crimea Square?” asked Gore, quickly.

“Your grandfather is stopping there—in No. 32; old Jefferies’ house.”

“Oh! I knew nothing of that. Go on.”

“Sir Simon,” proceeded the lawyer, looking at Gore, “stated in his letter that the description of the soldier, as given by the maid, applied to you, Bernard.”

Gore stared and looked puzzled, as did Conniston. “But I don’t quite understand,” said the former. “Do you mean that my grandfather thinks that I have been making love to some servant in Crimea Square?”

“In No. 32. Yes. That is what Sir Simon’s letter intimated to me.”

The other men looked at one another and burst out laughing. “What jolly rubbish!” said Lord Conniston. “Why, Bernard is the last person to do such a thing.”

“It’s all very well to laugh,” said Durham, rather tartly, “but you see, Gore, Sir Simon may think that you went to the kitchen, not to make love to the maid, but to see how he was disposed towards you.”

“But, Mark, I haven’t been near the place.”

“Are you sure?” asked Mark, sharply.

Bernard, always hot-tempered, jumped up. “I won’t bear that from any man,” he said. “You have no right to doubt my word, Durham.”

“Don’t fire up over nothing, Gore. It is in your own interest that I speak. I knew well enough that you wouldn’t make love to this housemaid mentioned by Sir Simon—Jane Riordan is her name. But I fancied you might have gone to see if your grandfather—”

“I went to see nothing,” replied Gore, dropping back into his chair with a disgusted air. “I don’t sneak round in that way. When my grandfather kicked me out of the house, I said good-bye to Alice and came to London. I saw you, to get some money, and afterwards I enlisted. I never knew that Sir Simon was in town till Conniston told me. I never knew he lived in Crimea Square till you explained. My duties have kept me hard at work all the time. And even if they hadn’t,” said the young man, wrathfully, “I certainly wouldn’t go making love to servants to gain information about my own people.”

“Quite so,” said Durham, smoothly. “Then why—”

“Drop the subject, Mark.”

“Sit down and be quiet, Bernard,” said Conniston, pulling him back into his seat, for he had again risen. “Mark has something to say.”

“If you will let me say it,” said Durham, with the air of a man severely tried by a recalcitrant witness.

“Go on, then,” said Bernard, and flung himself into his chair in a rather sullen manner. His troubles had worn his nerves thin, and even from his old schoolfellow he was not prepared to take any scolding. All the same, he secretly saw that he was accusing Durham of taking a liberty where none was meant.

“It’s this way,” said the lawyer, when Gore was smoothed down for the time being. “We know that Beryl hates you.”

“He wants the money.”

“I know that.” Durham smiled when he thought of the destroyed will; but he could hardly explain his smile. “Well, it is strange that the description given by the maid of this soldier—and a yeoman, mind you—should be like you. Have you a double?”

“Not that I know of.”

“Then someone is impersonating you so as to arouse the wrath of your grandfather against you. Sir Simon is a proud old man, and the idea that you condescended to flirt with—”

“But I didn’t, I tell you!” cried the exasperated Gore.

“No. We know that. But Sir Simon, judging from his letter, thinks so.”

“He has no right to do that. My conduct never gave him any reason to think I would sink so low.”

“My dear chap,” said Conniston, with the air of a Socrates, “when anyone has his monkey up, he will believe anything.”

“Conniston is quite right,” said the lawyer, “though he expresses himself with his usual elegance. Sir Simon, with Beryl at his elbow, is inclined to believe the worst of you, Bernard, and probably thinks you have deteriorated sufficiently to permit your making use of even so humble an instrument as a housemaid.”

“Bah!” said Gore, in a rage. “What right has he to—”

“Don’t be so furious, my dear man. I am advising you for your own good, and not charging seven-and-six either.”

This made Bernard laugh. “But it does make a fellow furious to hear his nearest—I won’t say dearest—think so badly of one.”

“One’s relatives always think the worst,” said Conniston, oracularly. “Miss Plantagenet thinks so badly of me that I’ll never see that five thousand a year. Miss Malleson will have it, and you, Bernard, will live on it. Pax! Pax!” for Bernard gave him a punch on the shoulder.

“Dick, you’re a silly ass! Go on, Durham.”

“Well,” said Durham, beginning in his invariable manner, “I fancy that Beryl is up to some trick. You have not been near the place; so someone made up to impersonate you is sneaking round. Of course, there is the other alternative, Mrs. Gilroy may be telling a lie!”

“She wouldn’t,” rejoined Gore, quickly. “She is on my side.”

“So you told me. But your grandfather thinks otherwise. We were talking about you the other day.”

“And Sir Simon said no good of me,” was Bernard’s remark. “But what is to be done?”

“Only one thing. Go and see your grandfather and have the matter sifted. If Mrs. Gilroy is lying you can make her prove the truth. If she tells the truth, you can see if Beryl has a hand in the matter.”

Gore rose and began to pace the room. “I should like to see my grandfather,” said he, “as I want to apologise for my behavior. But I am afraid if we come together there will be trouble.”

“I daresay—if Beryl is at his elbow. Therefore, I do not advise you to call at Crimea Square. But when Sir Simon goes down to the Hall again, you can make it your business to see him and set matters right.”

“I am afraid that is impossible,” said Gore, gloomily, “unless I give up Alice, and that I won’t do.” He struck the table hard.

“Don’t spoil the furniture, Bernard,” said Conniston, lighting a cigarette. “You do what Mark says. Go down to Hurseton.”

“I don’t want to be known in this kit, and I have parted with my plain clothes,” objected the other.

“You always were an impulsive beast,” said Conniston, with the candour of a long friendship. “Well, then”—he rose and crossed to the writing-table—“I’ll scrawl a note to Mrs. Moon telling her to put you up at Cove Castle. She can hold her tongue, and the castle is in so out-of-the-way a locality that no one will spot you there. You can then walk across to Hurseton—it’s only ten miles—and see if that Red Window is alight.”

“Your grandfather said something about the Red Window,” said Durham, while Conniston scribbled the note in a kind of print, since Mrs. Moon was not particularly well educated. “What is it?”

Bernard explained the idea of Lucy, and how she was playing the part of his friend, to let him know how matters stood. “I am always startled by a red window now,” he said, laughing at his own folly, “as it means so much to me. The other night I saw a chemist’s sign and it made me sit up.”

“It’s an absurdly romantic idea,” said Durham, with all the scorn of a lawyer for the quaint. “Why revive an old legendary idea when a simple letter—”

“Mrs. Gilroy and Julius would stop any letters,” said Bernard, “that is, if she is hostile to me, which she may be. I am not sure of her attitude.”

“What is the legend of the Red Window?” asked Durham.

“It’s too long a story to tell,” said Bernard, glancing at the clock, which pointed to a quarter to ten, “and I’m due at barracks. I’ll tell you about it on another occasion. Meantime—”

“Meantime,” said Durham, rising, “I advise you to drop red windows and legends and go down to see Sir Simon boldly. A short interview will put everything right.”

“And might put everything wrong.”

“No,” said Durham, earnestly, “believe me, your grandfather will be more easy to deal with than you think. I am his solicitor and I dare not say much, but I advise you to see him as soon as you can. The sooner the better, since Beryl is a dangerous enemy to have.”

“Well, Lucy is my friend.”

“And Mrs. Gilroy your enemy along with Beryl.”

“I’m not so sure of that,” began Gore, when Conniston lounged towards him with a letter.

“You give that to Mrs. Moon,” said he, “and she will put you up and hold her tongue and make things pleasant. But don’t say I am in town, as I have not dated the letter.”

“Does she think you are in America?” asked Bernard, putting the letter into his pocket, and promising to use it should occasion offer.

“Yes. She thinks a great deal of the West family,” said Conniston, taking another glass of kümmel, “and she would howl if she heard I was a mere private. And I don’t know but what she may not know. I saw that young brute of a Judas when I left you the other day, Bernard.”

“Judas?” echoed Durham, who was unlocking the spirit-stand.

Conniston sat down and stretched out his legs. “He’s Mrs. Moon’s grandson. Jerry Moon is his name—but he’s such a young scoundrel that I call him Judas as more appropriate. I got him a place with Taberley, the tobacconist, but he took money or something and was kicked out. The other day when I met him he was selling matches. I gave him half a sovereign to go back to his grandmother, so by this time I expect he’s at Cove Castle telling her lies. I instructed him to hold his tongue about my soldiering.”

“Why didn’t you send him to me?” said Mark. “I would have frightened him, and made him hold his tongue.”

“If you could frighten Judas you could frighten his father, the Old ‘Un down below,” said Conniston, laughing. “He’s what the Artful Dodger would call a young Out-and-Outer; a kind of Jack Sheppard in grain. He’ll come your way yet, Mark, passing by on his journey to the gallows. He’s only thirteen, but a born criminal. He’ll hold his tongue about me so long as it suits him, and sell me to make a sixpence. Oh, he’s a delightful young scamp, I promise you!”

All this aimless chatter made Bernard rather impatient. “I must cut along,” he said; “it’s rather foggy and it will take me a long time to fetch my barracks. No, thank you, Mark, I don’t want anything to drink. Give me a couple of those cigarettes, Conniston. Good night.”

“Won’t you stop the night?” said Durham, hospitably. “Conniston is staying.”

“He’s on furlough and I’m not,” said Bernard, who was now putting on his slouch hat in the hall. “Good night, Conniston. Good night, Durham.”

“You’ll think over what I told you,” said the lawyer, opening the door himself and looking outside. “I say, what a fog! Stop here, Bernard.”

“No! No! Thanks all the same.” Gore stepped out into the white mist, buttoning his coat. “Give me a light. There! Go back and yarn with Dick, I’ll come and see you again. As to Sir Simon—”

“What about him?”

“I’ll think over what you said. If possible I’ll go down and stop at Cove Castle, and see Sir Simon at night. By the way, what’s the time, Durham?”

The lawyer was about to pull out his watch when Conniston appeared at the end of the hall in high spirits. “My dear friend,” he said in a dramatic manner, “it is the twenty-third of October, in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and—”

“Bosh!” interrupted Bernard. “The time, Mark?”

“Just ten o’clock. Good night!”

“Good night, and keep that wild creature in order. Conniston, I’ll look you up to-morrow.”

It was indeed a foggy night. Bernard felt as though he were passing through wool, and the air was bitterly cold. However, he thrust his hands into his pockets and smoked bravely as he felt his way down the hill. Hardly had he issued from the gate when he felt someone clutch his coat. Brave as Gore was he started, for in this fog he might meet with all manner of unpleasant adventures. However, being immediately under a lamp, he saw that a small boy was holding on to him. A pretty lad he looked, though clothed in rags and miserable with the cold. In one hand he held a tray of matches and in the other a piece of bread. His feet were bare and his rags scarcely covered him. In a child-like, innocent manner he looked up into the face of the tall soldier. “Well, boy,” said Bernard, feeling for sixpence, “Are you wanting to get home?”