a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The City of Sydney Author: John Arthur Barry * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1600981h.html Language: English Date first posted: October 2016 Most recent update: October 2016 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Author of Steve Brown’s Bunyip, In the Great Deep, The Luck of the Native Born, A Son of the Sea, Against the Tides of Fate, &c., &c.

Production Note: In order to show details in some images (cover, title page, collage, and advertisements) have a larger version that can be shown by clicking on the small image. After viewing, press the back button on your browser to return.

CONTENTS

Publisher’s Note

Chapter I - The Founding of the City

Chapter II - Weakly Infancy

Chapter III - The Harbor—Macquarie’s Buildings

Chapter IV - Early Social Life

Chapter V - Sydney in the Twenties

Chapter VI - Sydney in the Twenties—(Continued)

Chapter VII - The Early Thirties

Chapter VIII - The Later Thirties

Chapter IX - The Early Forties

Chapter X - In the Forties

Chapter XI - In the Forties—(Continued)

Chapter XII - Sporting in the Forties

Chapter XIII - Some Early Suburbs & Islands

Chapter XIV - Sydney in the Fifties

Chapter XV - The Fifties and Sixties

Chapter XVI - The Sixties and Seventies—(Conclusion)

The Rocks Resumptions

Advertisements

“SYDNEY PAST AND PRESENT” was first published serially in the “Town and Country Journal,” and the great interest taken by the public in the subject was shown not only by the large demand for copies of the paper, but also by the frequent enquiries received by the Editor as to whether the illustrations and letterpress would be published in book form. THE NEW SOUTH WALES BOOKSTALL COMPANY aware of this demand, purchased the book rights of the letterpress and pictures, and the public have now an opportunity of acquiring in a connected form, this record of the oldest Australasian city.

During the first publication of the articles several letters were received correcting obvious errors of the Press, and less obvious ones of the author, who has in some cases made alterations in the text suggested by these letters.

Some of the illustrations, for which no good proof of authenticity could be obtained, have been omitted, and some good views of the Rocks, first published in the “Sydney Mail,” added by permission of the proprietors of that newspaper. In the case of some of the illustrations it is difficult to ascertain the authorship. But to the skilful pencil of the late Mr. John Rae, Sydney owes a great number of the best old-time pictures of the City—between the later thirties and the early fifties. And many of the blocks in this book have been reproduced from copies of these drawings. Most of the Modern Sydney pictures came from the studios of Messrs. Kerry & Co., photographers, George Street, Sydney.

Of course the ideal book on the subject should contain complete sets of pictures of the City at different periods, accompanied by letterpress supplying an accurate description to correspond with them. But the lack of historical material in a new country, such as ours, renders this impossible. This book, however, represents what, after a good deal of search and study among old records, could be found possible to use in reasonable and convenient form.

THE founder of Sydney was Captain Arthur Phillip, who, in 1788, discovered that Port Jackson, in place of being the mere open bay that Cook, years earlier, had taken it for, was in reality one of the finest harbors in the world, with space in its waters for a score of navies; on its shores for as many cities.

In 1770 Captain Cook had discovered Botany Bay, and recommended it to the Government as a good site for a colony. But it was not until eighteen years later that, wanting a site for a convict settlement, the authorities of the day bethought themselves of Botany Bay, and sent Captain Arthur Phillip in charge of eleven ships, since known as the “First Fleet,” to establish himself on its shores. But Phillip didn’t care about Botany. Water, he said, was scarce, the soil comparatively poor; and unable to endorse Cook’s glowing eulogy, the captain decided to go further afield and explore the coast to the northward. This he did in three open boats. More out of curiosity than otherwise, they turned in between the Heads to have a look at Cook’s “open bay, in which there appeared to be good anchorage.” And thus was discovered the wonderful harbor and the site of the future capital of the colony.

After first landing at Manly Beach (so named because of the courage shown by the natives), a spot for the settlement was eventually selected on the banks of a small fresh water stream that fell into a cove on the southern side of the harbour.

Soon the whole fleet came round, and brought up in the little bay, which was promptly named Sydney Cove, in compliment to the secretary of State. “In it,” to use Phillips’ own words, “ships can anchor so close to the shore that at a very small expense quays may be made at which the largest ships may unload. This cove… is about a Quarter of a mile across at the entrance, and half a mile in length.” And here did the old Sirius and her consorts anchor in that space of water, surrounded by the site of what is known to us now as Circular Quay. Low hills, scrub-grown, ran down to the water’s edge, and represented the position of the future capital of a little more than a century later, when ocean steamers by the score should line the wharves of the cove, and the highest developments of science, commerce, and art have combined to form the great city behind and around it.

But to return. A space having been cleared in the scrub large enough the military and the convicts to camp upon, on the 26th day of January a company came ashore near the spot where, in Macquarie Place, now stands the Obelisk, the stone from which all the roads in the colony take their distance and measurement. The national flag was hoisted, the marines saluted and fired three volleys, and the Governor, surrounded by his officers, proposed the healths of “The King and the Royal Family” and “Success to the New Colony.” Later, on the 7th of February, there took place another ceremony no less impressive, when the colonists, numbering 1030, were all assembled, the convicts seated in a half circle, the marines paraded in front of them, and the officers grouped in the centre. Then Collins, the Judge Advocate, read the Governor’s commission, and the commission of the other officers, also the Act establishing the colony, and other formal documents. Then the marines fired three volleys, and the first Governor of New South Wales, after thanking his officers and soldiers for their behaviour so far, addressed the convicts, promising rewards to those who conducted themselves well; unsparing severity to offenders. After his speech the colonists dispersed, whilst Phillip and his principal officers partook of a cold repast already laid out in a marquee. During the proceedings, at intervals, the band played, and after the commissions were read, “God Save the King” was performed.

And thus was consummated the founding of the colony. The residence of the Governor, what he quaintly calls his “Canvas House,” and the tents of the officers, were pitched on the east side of the little creek (presently known as the Tank Stream), with the flag staff reared in front of them, and close to were planted the various fruit trees procured at Rio Janeiro and the Cape of Good Hope.

The marines and the convicts in their charge were housed in huts on the west side of the cove. Phillip writes to his patron, Lord Sydney: “I have the honor to enclose your Lordship the intended plan for the town. The Lieutenant-Governor has already begun a small house, which forms one corner of the parade, and I am building a small cottage on the east side of the cove, where I shall remain for the present with part of the convicts and an officer’s guard. The convicts are distributed in huts, which are built only for immediate shelter. On the point of land (now Dawes Point) which forms the west side of the cove, an observatory is building, under the direction of Lieutenant Dawes, who is charged by the Board of Longitude with observing the expected comet. We now make very good bricks, and the stone is good, but do not find either lime stone or chalk… The principal streets are placed so as to admit a free circulation of air, and are 200ft. wide.”

And in such wise was the founding of the city of Sydney. Unfortunately, succeeding Governors altered those wisely-laid out streets of Phillip’s, with the result of giving us the miserable lanes of the present day. All this, however, was the work of much time and labour, and for long only the principal officers could boast of being lodged in wooden huts; for the rest, it was still canvas. The hard gum timber blunted and broke the shoddy tools of the workmen, who, in addition, were anything but mechanics. Also, there were continual complications and troubles to retard the progress of the infant colony and its capital. Phillip writes: “I am very sorry to say that not only a great part of the clothing, particularly the women’s, is very bad, but most of the axes, spades, and shovels, the worst that ever were seen. The provision is as good. Of the seeds and corn sent from England part has been destroyed by the weevil; the rest is in good order.”

Most pathetic and forlorn must have appeared to us, could we of this latter day have seen it then, the little settlement on the shores of the Cove, with its few scattered buildings, most of them “formed of rough boards nailed to a few upright posts shabbily covered with bark,” and situated mainly on the hill lying to the north-west of the Cove. Stumps of trees studded the hardly indicated streets; no wharves, even of the rudest description, had yet been formed; except around the mouth of the Tank Stream the scrub grew thick to the water’s edge, and loomed grey and monotonous on every inland hill, on every harbor headland. And to those of us who, passing to and fro the Cove of to-day, and threading the busy streets of the great city behind it, ever cast a thought to the scene it must have presented in those early months, years, even, the whole thing should appear little less than a miracle.

But, despite all hardships, trials, and sufferings, the stout heart of the brave founder never failed him, his patience, nor his absolute faith ever wavered. He, however, was the sole exception. Let us see, for instance, what the Lieutenant-Governor, Ross, has to say about the business. Writing to Under-Secretary Nepean, he wails:

“Take my word for it, there is not a man in this place (he should have excepted his superior) but wishes to return home, and indeed they have no less than cause, for, I believe, there never was a set of people so much upon the parrish as this garrison is, and what little we want, even to a single nail, we must not send to the Commissary for it, but must apply to his Excellency for it; and when we do he alwayes sayes there is but little come out, and it is but little we get… If you want a true description of the country, it is only to be found amongst many of the private letters sent home; however, I will, in confidence, venture to assure you that this country will never answer to settle in, for, although I think corn will grow here, yet I am convinced that if ever it is able to maintain the people here, it cannot be in less time than probably a hundred years hence. I, therefore, think it will be cheaper to feed the convicts on turtle and venison at the London Tavern than be at the expense of sending them here.”

This was written only six months after landing. And early though this was to show the white feather, the dreariness of the outlook and the weary hopelessness of the life might have excused a much stronger man than Ross was for weakening under the strain. There, however, can be no excuse for his incessant grumbling, and attempt to put every possible obstacle in the Governor’s way, instead of doing what he could to help him through his many and constant troubles.

As time passed, bricks were made, stones hewn, timber shaped, and houses built, in spite of difficulties which had at first sight appeared almost insurmountable. The winter rains made matters terribly uncomfortable for both bond and free; but the hardships thus engendered acted as a spur to them to provide efficient shelter from the elements.

Thus, in the winter of 1788. we find the settlers busily employed in carrying out the details of Phillip’s plan, long since dispatched to Lord Sydney. Barracks for marines were erected; houses for the Governor and the Lieutenant-Governor; the hospital was roofed with shingles, and the Observatory begun at the future Dawes Point. This last building, however, was scarcely finished before it was found to be too small, not only for its principal object, but to accommodate the lieutenant’s family. So the masons and other workmen set about building another Observatory in the same spot. On the other hand, the barracks, when finished, proved far too large for the military alone, and, therefore, was partially used as a store. The greatest inconvenience was felt throughout these operations for lack of men with any practical knowledge of building and the other trades necessary to make any progress with the erection of the city.

In October, 1789, came about a rather momentous event, no less than the launching of the first boat built in the colony. This craft was intended for the transport of stores from the newly-formed farm at Rose Hill, close to where Parramatta now stands. The boat was a huge and unwieldy specimen of the builder’s art. The convicts called it satirically the “Rose Hill Packet.” Then, learning by much hard experience how difficult it was to shift her, they altered that fancy name to the more appropriate one of “The Lump.” A magazine was about this time erected near the Observatory, and a house built for the Judge Advocate. The roadways—bogs in wet weather, and dust-heaps in dry, were made a little more passable towards Christmas time. Also a guard-house was built on the east side of the cove, close to the bridge, that had been thrown over the Tank Stream.

In the beginning of 1790 a flagstaff was erected at the South Head, by means of which the arrival of ships could be signalled to the infant Sydney. And from there during the terrible year of ‘90 many anxious eyes swept the desolate ocean for signs of that relief so eagerly expected. Food was giving out and necessaries of every description, and famine stared the embryo colony in the face. For nearly two years the colonists had been isolated. Apparently the Home Government had forgotten their very existence, notwithstanding many appeals from Phillip. And but for that same Phillip it is quite possible that not only would there be no Sydney to-day, but that Australia would be under French or Dutch rule instead of British. If Ross, for instance, had been in Phillip’s place the chances are twenty to one that on his lachrymose representations all attempt at colonisation would have been abandoned. But, fortunately for us, and for England, too, Phillip, the naval sea-captain, was the man of all men fitted for the occasion.

Famine was upon him and his charges, and night and day the seamen of the Sirius kept watch at the new flagstaff in hopes of being able to signal to the town the approach of those supply-ships that everybody believed with the most implicit faith must be long ere this well on their way from England.

But the events of this memorable year of 1790 are history, and Sydney, owing to disease and famine, grew little or nothing in size during it.

A fresh storehouse was finished, and a landing place formed at the head of the Cove; and, the bad year once passed, the young settlement seems to have steadily, if slowly, grown and spread, first along the foreshores and the course of the Tank Stream, until, cradled though it had been in despair and famine, and handicapped by the quality of its inhabitants, it presently began to be apparent to everyone that there was forming on the shores of the cove the nucleus of a city. In 1792 Phillip left the colony and went home to England, more secure than ever in the belief, which, indeed, had never deserted him, that the prosperity of the settlement was thoroughly assured.

One incident of ‘91 should be noted, in that the first convict settler, who had made a declaration that he was able to support himself on a farm he had occupied for fifteen months, received a grant of 140 acres of land. At the present day many of our settlers would be only too proud to be able to declare a similar fact.

In 1792 flour was 9d. per lb.; potatoes were 3d. per lb. A sheep cost £10 10s; a milch goat, £8 8s; breeding sows, each £7 7s to £10 10s; laying fowls, 10s. By these figures it may be seen what terrific value was attached to live stock of any description in these early days.

Tea was a luxury, indeed, at 8s to 16s per lb. Sugar was comparatively cheap at 1s 6d per lb. Spirits at 12s to 20s per gallon were cheaper than at present, and porter at 1s per quart was within the reach of most people. At this time, and for a score of years afterwards, it must be remembered that spirits, chiefly rum, were the ordinary currency of the colony. When Hunter arrived, in 1795, the whole population, with the exception of 179, was dependent on the public stores for rations.

Briefly, the events of his five years’ term embraced the first use of the printing press, the discovery of the lost herd of cattle, and the forming of the settlement of Newcastle, on the Hunter River.

So far as Sydney itself was concerned, the only building of importance seems to have been that of the first school. Here 300 children were taught, and, after service each Sunday, catechised by the Rev. Mr. Johnson. Various windmills, too, were erected to grind the settlers’ corn. This was done gratuitously by the government. In 1800 Captain Hunter was superseded by Captain King.

During the latter’s term the Female Orphan School, of which more anon, was founded; the first issue of copper coin took place. A notable incident was the establishment by a prisoner, Geo. Howe, of the first Australian newspaper, known as the “Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser.’’ This was in 1803, and original files of this ancient newspaper are now so scarce as to be very valuable. The editorial address accompanying the first issue runs:

“Innumerable as the obstacles were which threatened to oppose our Undertaking, yet we are happy to affirm that they are not unsurmountable, however difficult the task before us. The utility of a paper in the colony, as it must open a source of solid information will we hope be universally felt and acknowledged. We have courted the assistance of the Ingenious and Intelligent. We open no channel to Political discussion or Personal Animadversion. Information is our only purpose; that accomplished, we shall consider that we have done our duty in exertion to merit the Approbation of the Public and so secure a liberal patronage to the ‘Sydney Gazette.’ ”

FOR many years Sydney does not appear to have made much headway. Even in 1816-17 Woolloomooloo was a dense scrub, in which it was very easy to get bushed, whilst tea (sometimes wrongly called ti) tree grew freely throughout the city in streets and open places. Thatched houses and mud huts formed the majority of the buildings. Where the Town Hall now stands was a public cemetery, although not the earliest, for a burying-ground had been earlier made further north; the Cathedral grounds of to-day were a favourite camp for drovers and cattle dealers; and everywhere roamed the aborigine.

George-street (named after the reigning monarch) started from Dawes Point, and ran along the western side of the Cove. The only public wharf was that already referred to, and known as King’s. There, all the merchandise of the colony was landed. Near the wharf, the now almost neglected Tank Stream flowed into the Cove. Houses were scarce and scattered. Where the Mariners’ Church stands there was one of the few weatherboard cottages. On the other side of the Cove were situated the Government boatsheds.

The roads were still mere bush tracks of dust or mud, according to the weather. For some inscrutable reason other, an orphanage had been built at the corner of Bridge-street. Apparently the authorities expected a prolific crop of orphans. These, however, proved so scarce that in a few years the building was abandoned, and the land subdivided, and sold. Out of this re-arrangement Queen’s Place was formed. There was a bank—the Australia—at the corner of George and Essex streets. And here took place the first Australian bank robbery. The thieves tunnelled from a drain in an adjacent paddock until they reached the strong room, and, forcing that, got away in safety with much plunder.

Where the Bank of Australia now stands were the Government stores, whence rations were served out to the convicts. Across Bridge-street the Tank Stream flowed sluggishly, spanned by its thick-set bridge of a pattern seen over country brooks in England. The origin of the word “Tank” may not be generally known. It seems that a butcher at that time had his shop in Hunter-street, and his land extended back to the stream. On one side of his property were a number of excavations, or tanks, cut out of the solid rock, and in these the soldier’s wives washed clothes. Other accounts, however, say that out of these “tanks” the town derived its water supply. The two stories, even in those days, could hardly be compatible. Probably the latter is correct.

On the site of our present General Post Office stood a small house in a fruit garden, whilst near by was a clump of detached cottages and some fenced-in paddocks. At the corner of George and Barrack streets was in 1817, a cow-yard, which fronted George-street for a considerable distance. In the cottage next to the milkman’s lived a turner, and next him stood a three-roomed public-house.

The above is a facsimile of the copper plate which was discovered in March, 1899, when excavating a telephone tunnel near the corner of Philip and Bridge streets. Collins, the contemporary historian of the First Fleet, describes the laying of the foundation of the first Government House, and relates how this plate was then deposited. Collins prints the inscription, which last year saw the light for the first time for 111 years.

The site of the old markets was enclosed by a strong four-railed fence, and here were a number of sheds for the display of produce brought in by the settlers. North of the market stood a wooden pillory, large enough to hold a couple of offenders. Prisoners sentenced to floggings were brought to this place, tied to a cart-tail, and publicly whipped in view of the crowd of marketing women.

On the site of the present Cathedral, in a “wattle and daub” cottage, lived a drover. In this cottage he was one day found dead, and, dying intestate, the property—thought little of at the time—reverted to the Crown, and eventually was secured by the Church of England authorities, to whom Governor Macquarie made a grant of it. Later, he laid the foundation stone of the present Cathedral. As one stocks would not suffice, there were, in conspicuous places about the city, four more.

As long before as 1796, Sydney’s first theatre had been opened. Certainly it could not have been much of a building, costing, as it did, only £100. The first play performed in it was Dr. Young’s tragedy, “The Revenge,” a piece long since dead and forgotten, but which, in the latter part of the 17th century, had no small reputation as a public favourite. But it is the prologue of the old play that, first mouthed in the first Australian theatre, made the occasion so memorable, and for ever rescued from oblivion the title, at least, of Young’s play. And although the passage alluded to above is one of the stock quotations of the language, it may not be out of place to here give the four famous opening lines—

“From distant climes, o’er widespread seas we come,

Though not with much eclat or beat of drum

True patriots we, for, be it understood,

We left our country for our country’s good”

The tariff of admission was not extravagant, or does not seem so to us, seeing that a seat in the gallery, the fashionable part of the house in those days cost only one shilling cash, or its equivalent in spirits, flour, meat, or other necessaries. This, however, so it is said, was not actually the first entertainment of its kind in the colony, inasmuch as a performance of Farquhar’s “The Recruiting Office,” has been traced back to June 4, 1789—the birthday of George III.—“on which date some prisoners were graciously permitted to show their loyalty to their Sovereign by acting this play”—The 1796 theatre came to a bad ending. Whether truly or not, it was said that owing to its establishment crime increased to such an extent that the Governor ordered it to be pulled down; and for some years Thespian entertainments were not heard of except as private indulgences. Authorities are divided as to the authorship of the prologue, although it has been generally attributed to the notorious convict, George Barrington. This claim is, however, strongly contested by the late Mr. Samuel Bennett, in his valuable work, “The History of New South Wales,” in which the author considers it highly probable that the lines were written by Lieutenant-Colonel Collins, and that the fathering them upon Barrington was merely by way of joke. Be this as it may, the prologue, apart from the single verse given, is an extremely clever bit of work, teeming with sly allusions to the former proclivities of the actors.

The open Haymarket space of to-day was in these years, 1817-20, occupied by the Government brickyards. Hence the Brickfield Hill of our own time. In the meantime, the site of the present Town Hall had been occupied by a public pound, which, when the ground was presently required for other purposes, was removed to that upon which the brick fields stood. Also, upon the Haymarket, was situated the first toll-bar. A paddock extended from here right through to Hay-street, whilst a creek ran out into a large pond, that took up most of Ultimo. It was known as Dickson’s Pond, and was a common resort of the citizens when they felt like going for an afternoon’s duck shooting.

There were few other streets, and these mostly nameless, besides the ones already mentioned. Bush tracks, to be made into thoroughfares later on, abounded. Before Governor Macquarie appeared on the scene, there were indeed no “streets.” The sparsely built upon and straggling ways were known as “rows.” But in Macquarie’s time these were altered. Thus “Pitt’s Row” became Pitt-street. “Soldiers’ Row” Park-street, “Back Soldiers’ Row” Kent-street, etc. Market-street was merely a boggy lane; Woolloomooloo a farm, and Hyde Park a racecourse. Tribes of blacks roamed about Botany, North Shore, and Manly, and camped around and in the infant city itself.

The Botanic Gardens, Farm Cove, and most of the bay shores and headlands were all primitive bush. On the banks of the little creek in the Gardens, then a sparkling stream, now a sluggish pond, bridged, and with its course obstructed, was a favourite corroboree-ground of the natives. The present University grounds were known as Grose’s Farm; but the other suburbs, Newtown, Marrickville, Leichhardt, Glebe and Forest Lodge, were all thick bush, with, perhaps, here and there, the small cleared patch of some enterprising settler.

The barracks lay between George, Clarence, Margaret, and Barrack streets, and are remarkable only as the scene of the first step towards Bligh’s deposition by Major Johnson, and the New South Wales Corps of notorious memory:

“The drums beat to arms; the New South Wales Corps—most of them men primed with rum—formed in the barrack square, and with fixed bayonets, colours flying, and band playing, marched to Government House, led by Johnson. The Government House guard waited to prime and load, then joined their drunken comrades, and the house was surrounded.” The rest is matter of common history.

Prominence has purposely been given to the foregoing picture of Sydney, in order, if possible, to place before the reader some idea of what changes had taken place since Phillip left it—practically a city of great distances, and but little else. In 1809 Macquarie had arrived, and, as we have seen, took to the work of improving and extending Sydney with a ready and willing mind. Grose and Hunter had done little in this way, lacking opportunity and time. The former was only in office two years; and Hunter had his hands too full with the squabblings of the New South Wales Corps to admit of leisure for much else.

His term of office though, was notable for one happening, i.e., the first civil action of any magnitude was tried in Sydney The facts are worth stating:—“A soldier of the New South Wales Corps shot a hog, belonging to a Mr. Boston, for trespass. The owner of the hog used abusive language to the soldier. At the instance, so Boston alleged, of two of his officers, the soldier beat him with a musket. For this Boston claimed £500 damages. The trial lasted two days, and the court (a military one) gave a verdict against two of the defendants, with damages 20s each. The Governor, on appeal, confirmed the verdict. Thus, as a contemporary writer gleefully observes, “Though it was sought to make the Government a sort of military despotism, yet the seeds of civil freedom were sown, and would, in due season, bud and blossom,” a prediction, as we who now read, can amply testify, thoroughly borne out.

Let us see, now what Macquarie thought of his charge. He writes in his first dispatch:

“I found the colony barely emerging from infantile imbecility, suffering from various privations and disabilities; the country impenetrable beyond forty miles from Sydney; agriculture in a yet languishing state; commerce in its early dawn; revenue unknown; threatened with famine, distracted by faction; the public buildings in a state of dilapidation; the few roads and bridges almost impassable; the population in general depressed by poverty; no credit, public, or private; the morals of the great mass of the population in the lowest state of debasement, and religious worship almost entirely neglected.”

Truly a terrible indictment this to draw up against any people! And though it was, probably, in great measure true, there is all the more credit due to our ancestors for having survived such a state of things, and made us what we are.

Nor must it be imagined that, for all the pessimistic declaration just quoted, the lieges were entirely without their pleasures and recreations. There was, for instance, racing in Hyde Park, lasting three days, and conducted after the Newmarket fashion, followed by an ordinary and two balls. The principal prize was a “Lady’s Cup,” presented to the winner by Mrs. Macquarie. “The subscribers’ ball,” says “The New South Wales Gazette,” “took place on Tuesday and Thursday night, and was honored by the presence of his Excellency the Governor and his lady, his honor the Lieutenant-Governor and his lady, the Judge Advocate and lady, the magistrates and other officers, civil and military, and all the beauty and fashion of the colony… A supper followed the ball… After the cloth was removed the rosy deity asserted his pre-eminence, and with the zealous aid of Momus and Apollo, chased pale Cynthia down into the Western World; the blazing orb of day announced his near approach, and the God of the chariot reluctantly forsook his company. Bacchus dropped his head; Momus could no longer animate.” All of which, put in modern phrase, means simply a very wet night indeed, and no one with much less than three bottles under his belt at daylight.

In the earlier days of the colony Divine service was performed in the open air, soon after sunrise, and under the most shady trees procurable. In 1793, a temporary church had been built at the back of the huts on the eastern side of the Cove, near the corner of what are now Hunter and Castlereagh streets. It was erected at the sole expense of the Rev. Mr. Johnson, already mentioned, of strong posts, wattles, and plaster, and thus enjoyed the distinction of being the first Christian Church in Australasia. In 1798 it was burnt down. Then the brick store built in the premier year of the colony was utilised as a church. The same store, which appears to have been the very first house in the colony worthy of the name, stood a little behind the site of the present Bank of Australasia.

The first part of old St. Phillips’ (since replaced by the present fine Gothic structure) to be built was the clock-tower. This was finished in 1797; but in 1806 it fell down. Formerly of brick, it was rebuilt of stone the same year. The church itself was begun in 1800; but not until nine years later did the Rev. W. Cooper officiate therein for the first time. It was finished about a year afterwards, and a handsome altar service of solid silver was presented to it by his Majesty King George III. St. Phillip’s was consecrated by the Rev. Samuel Marsden, a gentleman of varied attainments and pursuits. On the last Sunday in December, 1809, Lachlan Macquarie, not long landed, attended service at the new church.

Marsden, of whom the early chronicles have much to say, was, in addition to a clergyman, a magistrate, landowner, and stockbreeder. Thus in the very next number of the “Gazette” to the one announcing the consecration of St. Phillip’s, appears his name in conjunction with two other settlers, offering a reward of £1 sterling, or a gallon of spirits, for all skins of native dogs.

And now, 90 years later, we are still offering from £1 to £5 for dingo scalps!

With the advent of Macquarie, Sydney began to shufle off something of the squalor and dinginess of those earlier days at which we have glanced. We have seen Phillip living in his four-roomed tent; then, later, in the hut dignified by the name of “Government House,” and surrounded by tenements, to which even it was a palace; we have seen the little settlement born in much travail to the accompaniments of hunger and hardships of every description, and the clanking of chains; the miseries alike of bond and free throughout the desperate struggle for existence during years that might well have depressed the stoutest hearts, dismayed the most sanguine souls. Then came the twelve years of Macquarie’s blended rule of despotism and benevolence; clear views and narrow, stubborn ones. You have read his first dispatch sent home when the first appalling impression of Sydney and its surroundings were hot upon him. Now read what posterity has to say of him:—

“He found New South Wales a gaol, and he left it a colony; he found Sydney a village, and he left it a city; he found a population of idle prisoners, paupers, and paid officials, and he left a large, free community, thriving in the produce of flocks and the labour of convicts.”

To Macquarie’s work as a builder there will be much occasion to refer.

FINE a harbour as Port Jackson was, the early days, as may be supposed saw few opportunities for the use of it as such. The comings and goings of ships were confined to those of a few transports with convicts, and of provision vessels at long intervals from England or the Cape. Later, trade was opened with the East Indies and with the United States.

Passages were of great length. For instance, one ship, the Ceres, took nearly six months to come out. A curious incident happened on the trip. Touching at Amsterdam Island she took off four men, two English and two French, who had apparently been marooned from a brig called the Emilia. For no less three years had these unfortunates lived in that desolate spot, subsisting mostly on seal flesh. About 1794 a little trade with India begins; for we read that “the snow Experiment, from Bengal, and the sloop Otto, from North America, anchored in the Cove”—the last named five months and three days out from Boston. Trust Jonathan to discover a chance for trade, no matter how distant the scene of operations! His notions, too, we may be very sure were welcome enough to the citizens, and his bargains profitable to himself.

As time passed, however, the duties of the signalman at South Head became less and less of a sinecure, and on occasions there was almost what might be called a rush of ships. Many of these oversea arrivals had curious stories to relate, some of the weather, others of their cargoes. Amongst the last Mr. Michael Hogan, who brought “the Marquis Cornwallis from Ireland, with 233 male and female convicts of that country,” seems to have had a very rough experience.

“We understand,” says the report, “from Mr. Hogan that there had been a conspiracy to take the ship from him. This was, however, happily defeated. Nevertheless, the commander felt it his duty to punish many of the ringleaders very severely; in fact, when they arrived in Sydney they were carried from the ship to the hospital.” That is all. But reading between the lines one can imagine unpleasant things.

Emboldened, perhaps, by the cruise of the Experiment, a sister snow, the Susan, presently arrived—231 days from Rhode Island. She took her time, and touched nowhere. She was laden with spirits, broadcloth, and a variety of useful articles. A desperately long and lonely journey for a small vessel of, likely enough, not 300 tons.

One vessel, the Britannia in these years—1794-1798—is constantly mentioned as bringing stores and live stock to the infant colony from Calcutta, Madras, and Capetown. Perhaps she may be looked upon as entitled to the distinction of the first “regular trader” to Sydney.

Of course we had nothing much to export, as yet. Nor was our first shipment, when we did imagine we had found something worth sending away, much of a success. Somebody, it appears, had made a big lot of grindstones out of the coarser sort of freestone. These were sent to the Isle of France, and deposited there with an agent for disposal. But one morning a slave, rushing into his master’s room, exclaimed, “Massa, massa, oh my gad, grindstone all run away!” It had rained in tropical fashion during the night, and demolished the stack of Australian grindstones, floating some of them out of the yard, and about the streets, and washing the more porous ones into mere sand. This story is, however, probably apocryphal.

But although these sporadic exits and entrances of wandering ships made Sydney, even in those far-off days, a port, journalistic recognition of the fact did not come until the printing of the first newspaper, in 1803. In it—

“Notice is hereby given that the ship Castle of Good Hope will positively sail for India on Sunday, the 13th current; and Captain M’Askell requests that all claims may be given in to him by the 10th.”

Then again, the editor, to make the most of his one ship, expatiates as follows:—

“The Castle of Good Hope is the largest ship that has ever entered this port, and measures about 1000 tons. During the passage she lost twelve cows and one horse, fell in with no other vessel, and met with no accident. Her passing through Bass’s Straits instead of going round Van Dieman’s Land considerably shortened her passage, and saved many cows.”

In a day or two, however, the paper is enabled to chronicle the arrival of a “whaler, the Greenwich, with 1700 tons of spermaceti oil, procured mostly off the north-east coast of New Zealand.”

And ever as the months pass, so does “ship news” require more space for both deep-sea and coasting—the last under the title “Boats.” “Came in from the Hawkesbury on Saturday last, the 19th instant, the William and Mary, W. Miller, owner, laden with wheat,” and so on, and so on. Deep-sea ships lay at anchor in the Cove, the small fry came up to the “Sydney Wharf.” “On Sunday morning last came five boats from Kissing Point with fruit, poultry, vegetables, and potatoes.”

Whalers seem to have put in pretty regularly to refit and re-victual; heaving down on some soft spot on the shores of the Cove for caulking of seams and patching of copper after the long cruise. In the thirties, whaling became a very flourishing industry indeed, attracting many men and ships from England and Scotland. But we shall have occasion to glance now and again at the state of the port during the progress of this chronicle.

On February 15, 1811, the second year of the reign of Macquarie, was born the first Australian by an Australian mother. His name was Arthur Devlin, his birthplace Liverpool, on the banks of George’s River in the County of Cumberland, New South Wales. His subsequent career is of interest from his having been one of the first whaleboat’s crew which claimed the championship of the colony. His companions were James and George Chapman, William Howard, Andrew Melville, and George Mulhall. The first race took place in 1830, and was from Dawes’ Battery round Shark Island, and back to the starting place. At that time the port was full of whalers, and competition was therefore keen. But these six young Australians, all standing over six feet, were too much for any of the other boats, and won easily.

Early in 1895 a contractor working on a piece of vacant ground in North Sydney, used as a market garden twenty years ago, unearthed three tombstones. And to these stones hangs a story that is part of the story of our city, and must be here briefly told.

The inscriptions, then, on these tombstones commemorated the deaths of the surgeon, the chief officer, and the master of the ship Surrey, all of whom died on the ship’s first passage to Sydney—a very terrible one, indeed. Early in the month of July, 1814, the ship Brexhornebury, while off Shoalhaven, fell in with a big vessel lying-to, her sails in confusion, and signals of distress flying. She proved to be the Surrey, transport, from Spithead, with 200 male and 139 female convicts on board. There was also a detachment of 25 soldiers. Contagious fever had broken out on board, not only among the convicts, but also among the officers and crew. The captain informed the master of the Brexhornebury that 28 of the male convicts, two soldiers, the chief officer, and two seamen had died; that he and the remainder of his officers and crew were still suffering; and he implored help to take his fever-stricken ship into Port Jackson.

Naturally there was no disposition to eagerly board the Surrey, and the boat’s crew lay on their oars, and doubtfully surveyed the floating pesthouse and the scared and disease-marked faces that peered wistfully over her bulwarks.

At length a man, turning to the captain of the Brexhornebury, said, “I can navigate. I’ll go on board and take her in.” This unknown hero did so, and brought the Surrey to Sydney with her captain, Paterson, dying, and the other officer little better. Most unfortunately, there is no mention of that man’s name. It was worthy of mention.

The Surrey got into port on July 27, and was anchored in a convenient position “near the North Shore.” But not until April 31 was the camp, in which her people had lived in tents, broken up, and the ship brought round to the Cove.

This old “Surrey” or, as the early records call her, the “Surry,” was one of the oldest traders, or, rather, transports, to Sydney, making between 1814 and 1840, no less than eighteen voyages; and she must have been almost identified with and looked upon by the citizens as part of their history. The tombstones, it may be mentioned did not distinguish the site of the burial, but were merely memorials placed there by sorrowing friends and shipmates at a much later period.

Of interest, as showing at what an early age men in those days reached positions of sea-responsibility, it is recorded that Captain Paterson and Surgeon Brooks were only 24 years old; while Chief Officer Crawford was but 28. Where the last resting places of the captain and the surgeon were really situated there seems no evidence. The chief officer was probably buried at sea.

During the twelve years of Macquarie’s rule he made roads, erected public buildings, and constantly travelled about the colony, distributing grants to deserving settlers, planning townships, and pardoning industrious prisoners. Fifteen months after the discovery of the long-sought-for-passage across the Blue Mountains by Wentworth, Lawson, and Blaxland, the Governor had, by placing nearly every convict in the colony at the work, formed a good road to the western plains. And along this he presently, accompanied by his wife and suite, journeyed, and founded the town of Bathurst.

But Sydney was the chief centre of this indefatigable man’s exertions. And he did nothing by halves. For instance, seeing that the old markets, close to the wharf, were most unsuitable for the purpose, he issued a proclamation that he intended to at once remove them to “that piece of open ground, part of which was lately used by Messrs. Blaxland as a stockyard, bounded by George-street on the east, York-street on the west, Market-street on the north, and the burying-ground on the south, and, henceforth, to be called Market Square.” If the shade of Macquarie ever revisits Sydney, what, one wonders, does it think of the great pile that now stands on part of the same ground? Does it envy the questionable achievement, and feel regret at not having been able to stand sponsor for yet another “Macquarie” effort; for he, too, often built well but not wisely.

Presently he erected a wharf at Cockle Bay (now Darling Harbor) for the reception of sea-borne goods, and, more particularly, grain and corn. And there have been wharves on that spot ever since for that especial purpose. He it was, too, who built a market house “surrounded by a cupola and lantern, and with a front portico supported by Grecian pillars.” Many of us remember this imposing structure as the late Central Police Court, dingy, dirty, and quite unfitted for such business. But in those days it was deemed a really superb building.

Years ago, in the time of Governor Hunter, a half-moon battery had been erected by the ship’s company of the Supply, and armed with some of the tender’s guns. This promontory was then called Point Bennilong, from the fact that, on the site of the battery now known to us as Fort Macquarie, Governor Phillip had built a house for Bennilong, the native who accompanied him to England, and afterwards returned with Hunter. In a plan of Sydney presented by the Hon. P. G. King to the Legislative Council, dated 1820, Fort Macquarie is shown, but mentioned as carrying sixteen guns. In that year, the point on which it stood was separated by a narrow stream from the mainland, and it was necessary to cross a drawbridge before entering the fort. Later on, the moat was filled in, some land reclaimed from the sea, and an outer wall built. Little, however, seems to be known of its history, because the earlier Governors devoted more attention to fortifying Dawes’ Point, and the fort, named after Phillip, which occupied the site of the present Observatory. This defence commanded the harbour; and with the battery on George’s Head, erected in 1803, and the one on old Bennilong Point, was considered sufficient for the defence of Sydney.

Probably the ever-restless Macquarie took the old Fort in hand, and did something for it, besides endowing it with his own patronymic. It is of interest to remember that at the time of the Crimean war this battery was provided with additional guns; during the latter end of 1870 it was strengthened by the addition of five 42 pounders. The last occasion upon which it was used was in March, 1871, when the guns were manned by fifty men, and the fort took a share in the spectacle known as the “defence of Sydney.” It has now totally disappeared to make room for a nondescript land of castellated barn, intended to serve as a tram terminus. In triumphs of grotesque uncouthness the architects of Macquarie’s and those of our own time seem thoroughly at one.

No less indefatigable as a former of streets than as a builder, did Macquarie prove himself. Already it has been told how he cut George-Street out of a thick scrub between the markets and the Cove; cleared and named many others, and by his exertions did much towards making the city out of the village. It must be remembered, however, that, unlike his less fortunate predecessors, he had the British Treasury at his back, and unlimited muscle at instant command. Plenty of land he also had to give away. And that he was liberal with it the story of Burwood House amply proves.

Mr. Alexander Riley was an enterprising gentleman, who, wishing to go in for scientific farming on a large scale, applied for and received a grant of no less than 1000 acres, extending from Parramatta to the Liverpool Road, and embracing much of the present boroughs of Croydon, Burwood and Strathfield. Here, with the aid of a small army of assigned servants, he fenced the whole of the estate, cleared half, subdivided it into paddocks, and laid down English grasses, besides building Burwood House. At this day the ancient mansion presents much the same appearance as it did in 1820, and its preservation speaks well for the endurance of the native timbers, and the excellence of early workmanship. Of course, as time passed, it was bit by bit shorn of its surrounding grounds and the last we hear of it was when, in 1885, Messrs. Hardie and Gorman sold the house, with 200ft frontage to Burwood Park Road, for £3550. Let us hope that whoever owns the eighty-year old house will deal gently with it, and not pull it down to build suburban red brick villas on its site.

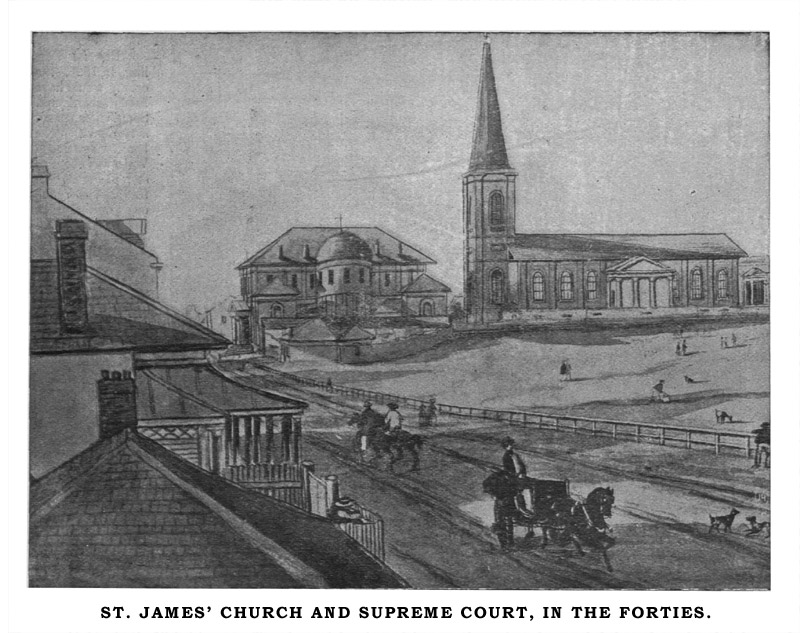

We have seen the building of the first permanent church—old St. Phillip’s.—Now, in 1819, was laid the foundation-stone of the second —St. James. Says an old writer:—“The spire surmounting the brick tower at the west end not only takes away from the heaviness of the edifice but also forms a conspicuous object from every part of the city and its neighbourhood.” This spire, it may be remembered, was renovated some years ago, and the interior of the building materially enlarged. Still, in all essentials, the church remains as it was in the days of Macquarie.

In the same year was finished and occupied the Hyde Park Barracks, used as the principal convict depot of the colony. All these prisoners on their arrival were forwarded here, and after being duly registered were open for assignment to the free inhabitants as servants. The Supreme Court was begun in 1820, but not completed for another eight years. Three years previously had arrived our first judge, Mr. Baron Field; also an Auxiliary Bible Society had been established; there was a free school, prisons, Churches, and a racecourse; but there were as yet, no free press and no trial by jury to complete the civilising of the city.

Before leaving Macquarie and his works, in stone and mortar, reference must be made to one of them, if only for the curious means by which he got it built, and the curious means the builders took of paying themselves.

The then colonial architect had been told to prepare plans for a general hospital. This he did, but on such a costly and lavish scale—a centre building and two detached wings to be erected of cut stone, with a covered portico completely surrounding each of the three piles —that Macquarie, although sorely tempted, considered the expense doubtfully, and for a while hung back. But only for a while. And, presently, he made an agreement with three well-known citizens by which these gentlemen contracted to erect the building in its entirety on condition of receiving a certain quantity of rum from the King’s store, and of having the sole right to purchase, and to land free of duty, all the ardent spirits that should be imported into the colony during a certain term of years, The “Rum Hospital,” as it was called at the time, was eventually completed in accordance with these conditions. The wages of those so employed were as was usual in those days, paid for half in cash and half in “property,” i.e., in tea, sugar, ardent spirits, wine, clothing, etc., or any other article the contractors happened to have in their store, and, which, of course, was charged to the labourer at an enormous percentage above its true value. And to make a clean sweep, the contractors erected several public houses in the vicinity of the works, at which the emancipist and convict labourers might spend their wages. Says Dr. Lang: “In the year 1824 the Rum Hospital was calculated to be worth £20,000. I am confident that a good building could now (1834) be erected for £10,000. The quality of Bengal rum received by the contractors was 60,000 gallons, worth at that time the whole estimated cost of the building. The monopoly was for three years, afterwards extended to three-and-a-half years, and as the contractors could purchase spirits at three shillings (a gallon) and retail them at forty, the right was supposed to be at least £100.000.”

And in this extraordinary fashion did Sydney get her first general hospital.

Surely never any charitable institution founded under such, to say the least of it, disreputable circumstances! Still though Macquarie’s contemporaries raged bitterly against him doubtless, out of the evil that attended its birth came eventually much good and comfort to the suffering. It served its purpose, even as does the beautiful building that now stands on the site of the “Rum Hospital” a portion of which, the southern wing, still remains with us in the shape of the Mint.

WRITING of Sydney in about 1821-2, a visitor remarks: “This town covers a considerable extent of ground, and would, at first sight, induce the belief of a much greater population than it actually contains. This is attributable to two circumstances—the largeness of the leases, which, in most instances, possess sufficient space for a garden; and the smallness of the houses erected on them, which, in general, do not exceed one story. From these two causes it happens that the town does not contain above seven thousand souls. There are in the whole upwards of a thousand houses; and although they are, for the most part, small, and of mean appearance, there are many public buildings, as well as houses of individuals, that would not disgrace this great metropolis (London). Of the former class, the General Hospital and the Barracks are, perhaps, the most conspicuous; of the latter are the houses of Messrs. Lord, Riley, Howe, Underwood, and Nichols. Land in this town,” the writer goes on to say, “is in many places worth £1000 per acre, and is daily increasing in value, rents are, in consequence, exorbitantly high. It is very far from being a commodious house that can be had for a hundred a year unfurnished.”

He visited the market, already described, and was rather pleased with it, finding it well supplied with grain, vegetables, poultry, butter, eggs and fruit. It was held on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

The Bank of New South Wales, he thinks, “promises to be of great and permanent benefit to the colony in general.” Its capital at that time was £20,000, divided into two hundred shares, and its paper was now the circulating medium of the colony.

Education was spreading, and the schoolmaster was going, comparatively, far afield. “There are in this town,” says a historian of these early twenties, “and other parts of the colony, several good private seminaries for the board and education of the children of opulent parents. The best is in the district of Castlereagh, which is about forty miles distant, and is kept by the clergyman of that district, the Rev. Henry Fulton, a person peculiarly qualified both from his character and acquirements for conducting so responsible and important an undertaking. The boys in this seminary receive a regular classical education, and the terms are as reasonable as those of similar establishments in this country” (England).

Compare this “seminary” business with the first school, already mentioned, of the Rev. Mr. Johnson, and it will be acknowledged that we were making rapid advances indeed. Here, bearing on the same subject, is an extract from the “Sydney Gazette” of the day:—

“Sydney Academy, No. 93, Phillip-street.—Wanted a Drawing and a Dancing master; persons properly qualified, and who can give satisfactory testimonials as to character and abilities, will meet with liberal encouragement by applying as above. Likewise, wanted a good laundress.”

And also: “Boarding and day-school for young ladies by Mrs. Hickey, Bent-street Sydney; opened for a limited number, where they will be instructed in English Grammar, writing, geography, and the French language. Terms: Under ten years, board and tuition, including English grammar and plain work, per annum £20.”

Then, for the opposite sex: “To parents, guardians etc.—Mr. Cuffe begs leave respectfully to acquaint his friends and the public that he has removed his day and evening schools from his late residence in Pitt-street to Macquarie-street where every attention is paid to the education of youth in all its branches, by himself, and able assistants, terms as usual. N.B.—A Sunday-school will be spiritually and morally attended to.”

All this sounds very fine; but it must be kept in mind that the city proper was as yet scarcely more than a collection of huts, with, dotted amongst them, the comparatively huge buildings of Macquarie’s regime: that the waters of the Cove still washed up to where the Paragon Hotel now stands, and that the gallows, upon which men were hung in batches, was a prominent feature of the city.

The first place of execution, by the way, was, as nearly as can be gathered, near Hyde Park, not far from where St. James’s Church now stands. But, although accounts differ in this matter, it seems pretty certain that the site of the original gallows afterwards formed part of a garden, taking in the ground upon which is erected the Supreme Court; and, probably, this garden ran up to the corner of our King street. However, this may be, the gallows, in 1804, began a series of journeys; close to the corner of Park and Castlereagh streets, occupied in 1848, as it is now, by the Barley Mow Hotel; thence it was taken to some part of Sussex-street, where, in the same year, stood Barker’s Mills: then it was moved to a piece of ground near Strawberry Hills; then to the back of the Military Barracks; from there, in the beginning of the twenties, this much-travelled machine found a resting place on the summit of a cliff in Princes-street, at the rear of the gaol in Lower George-street. Its final journey was to the front of the new gaol at Darlinghurst, where it performed its first duty on two men convicted of murder, in October, 1841.

Innumerable arguments have taken place about this matter of the precise situation of the original gibbet. But by what can be learnt from careful research, the above is as nearly as possible its early history.

A dominating feature of the Sydney landscape, to which reference has already been made, was the windmills crowning some of the most prominent heights, and forming, as will be seen in the old prints, a not unpicturesque element in the scene.

Steam, for the purpose of grinding com, was not utilised until about 1828. Says the “Gazette” of 1819: “Mr. John Blaxland begs leave to inform the public that he has erected a mill for the grinding of grain, the stones of which are the production of the colony; and that he will grind wheat at 1s per bushel. Any person found taking stones from his Luddenham Estate will be prosecuted.”

The last intimation shows that the editor of the “Gazette” had to suffer imposition as well as his modern prototypes, it being, to all intents and purposes, a separate advertisement. But, then, Mr. Blaxland was a person of weight in the community, whilst the poor newspaper man of those days had to tramp round the country for many miles, and in all weathers, humbly soliciting payment of two, and even three, years’ overdue subscriptions.

Although the readers of this book should be able to form for themselves, aided by the pictures, a fairly accurate idea of Sydney at the various ages of its growth already touched upon, yet, to give effect to these, something must be said of the men and women, our forbears, who had their being, and lived their lives under so much less happier auspices than do we the present day.

But contemporary historians have not given us, in this respect, very much to go upon. Their time was too greatly taken up by chronicling political squabbles, and the gradual expansion of the colony outside the capital, to afford any leisure for more in a glimpse now and again into the social life of Sydney itself.

Says an early visitor, writing just about the advent of Governor Brisbane:

“Society is upon a much better footing throughout the colony in general than might naturally be imagined, considering the ingredients of which it is composed. In Sydney the civil and military officers with their families, form a circle at once select and extended, without including the highly numerous respectable families of merchants and settlers who reside there. Unfortunately, however, the town is not free from those divisions which are so prevalent in all small communities. Scandal appears to be the favourite amusement to which idlers resort to kill time and prevent ennui; and, consequently, the same families are eternally changing from friendship to hostility, and from hostility back again to friendship.”

These conditions, it may be remarked, will still hold good at present of many other towns, besides Sydney some eighty years ago.

Continues our author: “Of the number of respectable persons some estimate may be formed if we refer to the parties which are given on particular days at the Government House.” Even now many people gauge respectability by much the same test. And notice that word “respectable.” It occurs throughout the old chronicles, and is pregnant with meaning. To be respectable in those days was apparently to be “pure merino,” with no taint even of the emancipist, let alone of the actual convict, about you. And that such spotless ones among the flock were very far from being numerous is shown by the fact that at one of these Government House festivals, in 1822, there were about 160 “respectable” ladies and gentlemen.

Writing a year or two later, the author, already quoted above, remarks rather significantly: “There are at present no public amusements in this colony. Many years since there was a theatre, and more latterly annual races. But it was found that the society was not sufficiently mature for such establishments.” Reading here between the lines, one seems to have unpleasant visions of what our early “general public” was like. Later on, as we shall see, they matured, and, presumably, improved.

From all that can be gathered, and that is but little, our folk of the early years led lives, that, if busy, were none the less monotonous, void of social amusements, except, perhaps, at long intervals, a supper and ball at Government House, or some public celebration like that of the Anniversary Dinner. Of their home life, there has been no word-painter, and of it we know little or nothing.

This function, the Anniversary Dinner, merits rather more than passing notice. The first one on record seems to have been on January 26, 1817, and was held by Isaac Nichols, Postmaster of Sydney, at his house in Lower George-street, at the head of the Cove, to celebrate the 29th anniversary of the foundation of the colony. There are forty select, and presumably thoroughly “respectable” guests, who sit down to table at five in the afternoon, and retire at ten that night.—There are loyal toasts proposed after the cloth is removed; and the “Muse of Mr. Jenkins,” who is the chairman, has composed a song, which is sung to the tune of “Rule Britannia.” A verse or so will suffice to give the reader an idea of this, undoubtedly the first Australian patriotic song:—

When first Australia rose to fame,

And Seamen brave explored her shore

Neptune with joy beheld their aim.

And thus express’d the wish he bore.

Chorus—

Rise, Australia! - with peace and plenty crown’d

Thy name shall one day be renown’d.

Then Commerce, too, shall on thee smile,

Adventurous barks thy ports shall crowd;

While pleas’d, well pleas’d, the Parent Isle

Shall of her distant sons be proud.

Chorus—

Rise, Australia! with peace and plenty crown’d,

Thy name shall one day be renown’d.

And who shall say that “Mr. Jenkins” did not make a very fine forecast indeed, and one fulfilled to the very letter?

Next year the celebration became official, taking place at Government House, while in the evening Mrs. Macquarie gave a ball. Mr. Howe, the editor of the “Gazette” was graciously allowed the privilege of a look round during the evening—not being “respectable” that, of course, was as much as he could expect—and he appears to have been very much taken with a portrait of Admiral Phillip, which was suspended at one end of the room, encircled with wreaths and banners, and an inscription running:—“In commemoration of the thirtieth anniversary of the colony of New South Wales established by Arthur Phillip, whose virtues and talent entitle him to the grateful remembrance of this country, and to whose arduous exertions the present prosperous state of the colony may chiefly be ascribed.” Which goes to show that contemporary recognition of the first Australian pioneer was stronger than that of succeeding generations; and, indeed, until quite recently, in our own day. The artist was a Mr. Greenaway, the Colonial Architect; and it would be of interest to know if that old portrait is still in existence.

The thirty-second anniversary (1820) was celebrated by a public dinner at Hankinson’s rooms, in George-street, which was attended by “sixty or seventy respectable persons.” But on this occasion there was no enthusiasm to speak of, owing to the fact of the guests being over-charged. The tickets for the dinner cost 40s—“without any kind of refined articles, such as jellies or blanc manges, and the elegance of a tip-top tavern table, such as could be had in London for a quarter of the money.”

Some of these good people had probably been glad enough, in the starvation years, of a feed of hominy, and now they are growling because mine host had not provided blanc manges and jellies! And, by the way, it is remarkable that now we find this function left chiefly to the emancipists, who, apparently, have been admitted to call themselves “respectable.” This was, of course, Macquarie’s doing; for only a month or two after landing he had shown very clearly where his sympathies lay by making a convict a magistrate. Certainly, the person in question had been transported for some petty offence at the age of 16. But the affair, nevertheless, gave a tremendous shock to the untainted members of the community.

In 1821. the thirty-third anniversary was perhaps the most successful of any so far. It took place at Gansdell’s Rooms, Hyde Park, when 101 emancipists sat down to a great spread. Dr. Redfern was president, Simeon Lord was vice-president, and there were eight stewards. It is particularly noted by the chronicler of the affair that both dinner and wines were excellent.

Succeeding celebrations all partook of the same non-political and partially representative character until 1825, of which more anon.

Major-General Sir Thomas Brisbane, K.C.B., was now Governor of New South Wales—the second of our military Governors. For the city, in the way of adding to or beautifying it, Brisbane did little or nothing. Indeed, during the whole of his four years stay, he was more or less in hot water. In the first place, he, with a stroke of his pen, altered the financial policy of the colony. and with such disastrous results that wheat rose to £1 per bushel. Wheat, when he arrived, was practically the currency of the country, and was exchangeable at the Government store for vouchers representing an average rate of 10s per bushel. These receipts were as good as cash in Sydney. Brisbane suddenly changed this circulating medium from sterling to colonial currency, with the result of raising the pound sterling 25 per cent above the pound currency; the effect on the small farmers, already many of them deeply in debt to Sydney merchants, may be imagined. Before this, however, he had fallen out with the Scotch Presbyterians. And this was the more curious, inasmuch as Brisbane was himself a Scot, and a Presbyterian to boot.

Dr. Lang arrived in 1823, and at once set about getting a church built, collecting, in a few days, upwards of £700 for that purpose. A memorial was now addressed to the Governor, praying for Government monetary aid for the undertaking. To this a sharp and insulting reply was sent, refusing the wished-for help. The committee, indignant, applied for redress to the Home Government, who severely reprimanded Brisbane, and ordered him to advance not one-third of the cost of the erection, but also to pay the officiating minister a salary of £300 per annum, “regretting,” at the same time “that his Excellency put to their probation members of the Church of Scotland in the colony—the Established Church of one of the most enlightened and virtuous portions of the Empire.”

Thus Brisbane got his snub, and the Scots their church. Later on the Governor, however, showed himself anything but a small minded man; for, perceiving that he had been quite in the wrong, he replaced his name on the list of subscribers, off which, in anger, he had caused to be taken. Nay, more, he laid the foundation-stone of the Church in July, 1924. Such is the story of St. Andrew’s, or, as we, at this day, more generally know it, the “Scots Church.” Standing at the south end of Church Hill, it is practically unchanged; looking as stiff, sturdy, uncompromising, and rugged as the man through whose enterprise it was built.

Dr. LANG never forgave Brisbane for the slight put upon the Sydney Presbyterians by comparing them to their disadvantage with the Roman Catholics. Thus, when the Governor instituted yearly and half-yearly races in the capital, Lang calls him the “patron saint of Australian jockey-ship.” The Scot divine says bitterly: “There are the Sydney and the Parramatta races… There are the Windsor races, and the Liverpool and the Campbelltown races. There are races at Maitland and Patrick’s Plains; two different stations on Hunter’s River; at Bathurst, beyond the mountains; and at Goulburn Plains, 200 miles from Sydney, in the district of Argyle. In short, ‘the march of improvement’ is much too weak a phrase for the meridian of New South Wales; we must, therefore, speak of the ‘race of improvement,’ for the three appropriate and never-failing accompaniments of advancing civilisation in that colony are a racecourse, a publichouse, and a gaol.”

This was unfair and unjust. But Dr. Lang was at times both. Later he wrote:—“When I ask what Sir Thomas Brisbane did for New South Wales, I pause in vain for a reply. When I ask what memorial he left behind him to endear his memory to the country and to perpetuate his fame, a hundred fingers point to the ‘Brisbane Cup.’ ”

But Brisbane did more than this, for he established a fine Observatory at Parramatta. Also, before he left, he launched a thunderbolt at the exclusives of Sydney by actually dining with “the elite of the emanpists.” During his regime, too, was, in 1824, established our first Executive Council; and there arrived our first Chief Justice, Francis Forbes (afterwards Sir Francis); Saxe Bannister, the Attorney-General; John Stephen, father of the late Chief Justice (Sir Alfred Stephen), as Solicitor-General and Commissioner of the Court of Requests; John Mackness, as Sheriff; and T. E. Miller, as Registrar. The first trial by jury was empanelled in a civil cause in February, ‘25. Noteworthy, too, was the establishment of the first independent newspaper, the “Australian,” which was published by Messrs. Wardell and Wentworth.

It will thus be seen that if, during this period, there was little increase in the growth of the city, there were a good many events of importance that were most intimately connected with its present welfare and its future history.

Recurring to the establishment by the Governor of the periodical race meetings so contemned by Lang, it may be of interest to know how the boundaries of the old-time course ran.

The grand-stand, then, in 1821, and the winning-post stood at the top of what is now Market-street; the course took a sweep to the right in the direction of Hyde Park Barracks, thence past the site of St. Mary’s Cathedral and the Sydney Grammar School, passing in front of Lyons Terrace, obliquely to the top of Bathurst street, then along what is now Elizabeth-street, to the corner of Park-street, and thence to the winning post. When first formed, the length of the course was one mile and a quarter, but it was afterwards shortened to a mile and six yards.

The first race took place about 1810, when the 73rd Regiment arrived under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Maurice O’Connell (the late Sir Maurice O’Connell), and the first prize was won by a horse named “Chance,” the property of Captain Ritchie; the Colonel’s mare, “Carlo,” won the second; and one belonging to D’Arcy Wentworth, the third. But shortly after Governor Brisbane’s arrival houses began to spring up so quickly around this quarter that the course was removed to what was known as the Sandy Racecourse, about four miles to the southwards, towards Botany Bay.

One curious event of 1824 was the seizing of a vessel, while at anchor in Sydney Cove, by a King’s ship, acting on behalf of the East India Company. This company, it appeared, claimed the exclusive right of trading in Eastern waters. Now, the colonial Government had chartered a ship—the Almorah—and had sent her to Batavia whence she returned with a valuable cargo of rice, tea, sugar, etc. Presently some of the Sydney merchants, jealous of official meddling with their prerogatives as traders and importers, laid an information against the Almorah with the captain of an English man-of- war, then lying in the harbor; and she was seized in open defiance of the Government, and sent off with her cargo as a prize to India, on a charge of infringing the Company’s charter. The mere fact, it was alleged, of her having tea on board was sufficient excuse for this arbitrary proceeding.

Of course there had been bushrangers in the colony before Brisbane’s time, but not any calling for special mention until the Donohoe gang, who flourished in 1825, and the three following years, instituted a very reign of terror in Sydney and its immediate neighborhood. Donohoe’s gang contained a dozen ruffians; but his chief companions were Walmsley, Webber, and Underwood—all transported convicts except the last, who was native-born. After a time, however, his mates discovered that he had been keeping a diary of their proceedings. Disgusted with this literary effort, they effectually stopped all chance of publication by deliberately murdering the unfortunate author. He had, so it was alleged, joined the gang from mere love of adventure.

For four years these men set the police at defiance, notwithstanding that a reward of £100 was offered for the ringleaders. Between Sydney and Parramatta they murdered and robbed, and fought the police with an impunity that says little for the constitution of the “force” of those days. So great did the terror of the band become that travel’ers joined together for protection. Says a newspaper of the time, speaking of Donohoe and his depredations: “Some half dozen constables or so, we believe, have been packed off up the Parramatta and Liverpool roads, but have returned to town as usual, safe and sound and empty-handed… Some effective measures should be taken, and that speedily, to suppress this alarming evil.”

The dress of the three leaders has been described, and shows that they wanted for little, in that respect at least. “Donohoe: Black hat, superfine blue cloth coat, lined with silk, surtout fashion, plaited shirt (good quality), laced boots, and snuff-coloured trousers.” He seems to have been the dandy of the trio. His two aides, however,—Walmlsey and Webber—were almost equally well-dressed.

At last the residents, harassed beyond endurance, rose in their own protection and gave battle to the bushrangers at Raby, now Bringelly. Here Donohoe was shot. But most of the others managed to escape through the thick scrub. Later on, Walmsley and Webber were captured on the Western road. Walmsley turned king’s evidence against Webber, who was presently hanged. Through the informer others of the gang were at intervals captured, and the long reign of “Bold Jack Donohoe” and his banditti was over.

But during Brisbane’s official term dozens of men seem to have taken to the bush, and had more or less long and successful careers, ending in death by the gallows or the bullet. The Bathurst district was especially prolific of bushrangers; but, compared with the bloodthirsty Donohoe gang, the majority of them appear to have been mere station-hut robbers and petty pilferers of that kind. Nor did we ever produce anything equal to the terrible Tasmanian outlaws. But whilst for robbery under arms they most surely swung, at times, a merciful judge, for simple thieving, might only send them to Norfolk Island, “to be worked in chains during their lives.”