a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Kookaburra Author: Edward S. Sorenson * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1305471h.html Language: English Date first posted: September 2013 Most recent update: September 2013 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

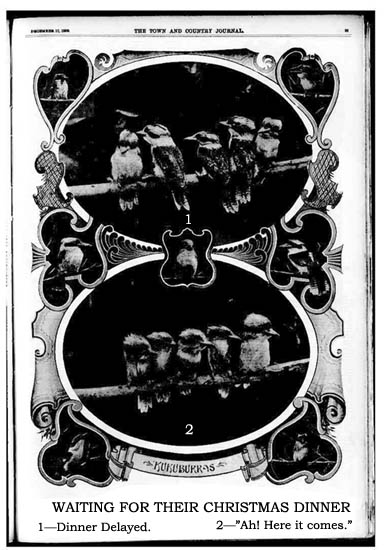

The Kookaburra (the word is spelled in various ways, such as "Kukuburra," "Gogoburra") forms one of an important quartette that have been associated with Australian literature from its inception, the other three being the Curlew, Mopoke, and Emu. Though the latter is generally regarded as our national bird, the Kookaburra is equally worthy of notice; indeed, it may be said that, in certain parts, at least, it has claimed more interest from bushmen and visitors as one of the world's feathered oddities. Its striking appearance alone commands attention, while its "laugh" is even more remarkable. Forbearance on the part of bushmen has made it fearless, and it is a constant companion at all bush homes. Never very shy, it has always been a conspicuous object to settlers, even apart from its remarkable and irresistible cry. In earlier times it was known as the "Settler's Clock," from a belief that its joyful paeans were vented regularly at morn, noon, and dusk, being quiescent through the heat of the forenoon and the wane of the afternoon. That belief has long been shattered. The Kookaburra laughs just when the fit takes it, particularly when excited, which occurs at any hour during the day. A wounded bird makes a demoniacal row, which will bring all others within hearing into the neighbouring trees, and these at once set up an echoing cackle that is repeated again and again. I have also noticed, when a bird alights alone in a tree, it will generally laugh loudly, repeating at intervals until joined by its mate. A bird in one tree will also answer a brother in an adjacent tree, the refrain being caught up by others in the distance, in the same manner as cockerels will answer one another at night. Again, when two come together on a limb, they express their approval in a "hearty laugh," and when several converge from divers directions, it is mutually accepted as an occasion for general rejoicing.

The Kookaburra is the giant of the kingfishers, more than half of which family belong exclusively to Australia. With the exception of the brilliant blue-and-white, which frequents rivers, creeks, and lagoons, the best known members, unlike the usual order of kingfishers, have no love of the water, and do not live on fish. The blue and white or sacred kingfisher is also known as the Van Dieman's Land Jackass, though it is never seen in Tasmania. The one other well distributed member is the bush kingfisher, which, like the Kookaburra, nests in hollow trees, often miles away from water. It has also a fondness for the wart-like ant nests that are built high up on the trunks of dead trees, into which it pecks a circular hole and lays its eggs. I have often watched these little fellows gamely fighting the huge "goanas" that encroached upon the precious precincts of the nest. It is identical with the mangrove kingfisher of northern and far north-western New South Wales.

Compared with the brilliant colours of the other members of the group, the plumage of the common Kookaburra is dull and commonplace. The upper parts vary from brown to chestnut brown, and from white to dirty white below: while the wings are relieved by dashes of shimmering blue. The tail feathers are fairly long, fan-shaped when open, and barred or mottled with brown. It has a peculiar habit of throwing the tail up, even to an incline over the back, on alighting on a limb. It has also a sort of crest, which is in evidence when the bird is excited, when catching its prey, or at such times when several are "holding a corroboree."

Perched on a limb, it looks much bulkier of body than a crow, though not so long; stripped of its feathers, however, it is remarkably small, ridiculously so in comparison with the size of its beak. Though possessed of considerable gripping power, the legs and toes are somewhat weedy; its flight is short and heavy, lacking the wing-skill of most bush birds. Its great strength lies in the beak, as I have had reason to know more than once when handling wounded ones. They vary considerably in colour, and even in size, in different parts of the country, the snow white and white and chestnut being not uncommon. The Kookaburra of Eastern Queensland is a beautiful bird, greyish-brown on the back, with a broad, light-blue band near the tail, and varying shades of blue on the wings. The breast is of a light-greyish hue, closely streaked with brown. It is known as Leach's Laughing Jackass.

Though not a water-haunting bird, it is not a frequenter either of the dry country, being totally unknown in the north-west of New South Wales, and favouring mostly the eastern portion of Australia. In the west and north-western parts of the country we find only an allied species known to science as "D. cervina."

The Kookaburra's usual food consists of grubs, worms, frogs, caterpillars, small lizards, and small snakes. It will also pick up fresh meat, and I have known them to haunt a slaughter yard, though it will not touch a dead beast. On account of its snake-killing reputation, it was protected by Government in many parts of the country, and looked upon as a sacred bird by bushmen. It was averred that no snake could approach a hut while a Kookaburra was about. This however has gone the way of many other old time beliefs. The big black snake may bask in the sun with impunity, though a score of Kookaburras may be watching it, and venting their cachinations overhead. A reptile will always excite them, but they are chary of tackling one, except the small green or whip snakes.

I saw a pair killing one of these snakes once on the Richmond River. One of the birds at first was perched on a low limb. Its mate picked up the snake, carried it towards the top of a high tree, and dropped it. As it neared the ground, the other bird darted out suddenly and caught it, carrying it high into the air when it was again dropped. Then the first bird swooped down and caught it. This was repeated several times, the birds rising with a heavy fluttering motion of the wings, the beak downwards, evidently guarding against the doubling movements of the enemy. Finally, one of them carried it to a limb; the other joined it with a triumphant laugh; and then commenced a lively tug-of-war. One moment the snake would be hanging over the limb, perceptibly stretching, and a bird hanging under each side with closed wings. Presently, one would let go, and the other would fall with a sudden recoil of snake, followed by a short, startled squawk. The battle was renewed on the ground; then again in the air; and the last I saw of them was a wild flutter in the distance, mixed up with several others in a general squabble.

I have witnessed the same interesting combat between them over a chicken. The Kookaburra is far more partial to that diet than it is to snake. Though it will kill small snakes, like the Yankee who ate crow, it doesn't hanker after them. But let it once taste chicken, and it becomes as great a pest to the poultry-yard as the hawk and crow. For this reason many settlers now shoot it at sight. I saw a farmer at Woram (N.S.W.) shoot as many as a dozen in one day without going ten yards from the door. They are among the easiest birds in the bush to kill.

On a farm on the Clarence River I often watched a pair of Kookaburras following the plough, and picking up the white grubs and worms. A farmer in the same locality told me that a pair was always waiting for him on a stump when he went to work in the mornings, and as soon as the plough started they would fly to the furrow and follow it. Occasionally when the ploughman didn't turn up as usual they would linger for hours about the ground, waiting for their breakfast to be unearthed, now and again relieving their feelings in a noisy duet.

The Kookaburra is also known as the Laughing Goburra and the Laughing Jackass. The latter is the most common. How this name originated is not very clear. There is nothing about the bird to suggest a jack or an ass. Barton ("Australian Physiography") suggests that the name is derived from a French word meaning to giggle. One bush version is that its cry in the distance was mistaken for the bray of an ass by a new chum named Jack. His mates afterwards so mercilessly chaffed him about his ass that the bird became generally known as "Jack's Ass." The best version I have heard has an aboriginal origin. A blackfellow, struck by some resemblance in a hilarious miner to the laughing bird, called him "Chaka-Chaka." The miners subsequently alluded to the birds as Chaka-Chakas.

This was soon shortened to Chakas, and that in turn corrupted to Jackass.

Whatever the origin, Jackass to-day, when applied to a silly person, conveys the same meaning as "an ass." In a different sense, we have also the term, "From jackass to jackass," meaning from daylight till dark. It might be remarked that no name fits the bird better than Kookaburra, the first two syllables of which it seems to continually utter in its so-called laugh. In giving vent to this, its head is held up, the huge mandibles wide apart, pointing skywards, and its wings continually move in little flutters against its side. It would seem to require some little exertion to properly modulate the cackle; when it is over, the bird gazes down with a quaint aspect blended of apathy and reflection.

In "A Sketch of the Natural History of Australia," it is claimed that Jack is one of our "incomparable mimics." This he decidedly is not. During many years' experience I never heard one attempt to imitate any foreign sound. His "laugh" embodies all the notes peculiar to him, and when the laughing fit has passed, there is no more sedate or sober-looking bird in the bush than the Kookaburra.

This site is full of FREE ebooks - Project Gutenberg Australia