a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Genesis of Queensland. Author: Henry Stuart Russell. * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1305181h.html Language: English Date first posted: August 2013 Date most recently: August 2013 Produced by: Ned Overton. Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Production Notes:

In this work, punctuation, including the accenting of foreign words, is somewhat haphazard; regular examples include "did'nt", "could'nt", etc.; some of it, largely quotes, has been modernised.

It is hoped that by making few corrections, the flavour of the book has been preserved. A few errors—typographically convincing—have been corrected.

GENESIS OF QUEENSLAND.

AN ACCOUNT OF THE FIRST EXPLORING JOURNEYS

TO

AND OVER DARLING DOWNS:

THE EARLIEST DAYS OF THEIR OCCUPATION;

SOCIAL LIFE;

STATION SEEKING;

THE COURSE OF DISCOVERY, NORTHWARD

AND WESTWARD;

AND A

RESUMÉ OF THE CAUSES WHICH LED TO SEPARATION

FROM NEW SOUTH WALES.

WITH

PORTRAIT AND FAC-SIMILES OF MAPS, LOG, &c., &c.

BY

Sydney:

TURNER & HENDERSON.

MDCCCLXXXVIII.

Dedicated

TO THE MEMORY OF

HENRY HUGHES,

OF

WORCESTER, ENGLAND,

AND

WESTBROOK, DARLING DOWNS, QUEENSLAND.

"By heaven! I cannot

flatter,

————but a braver

place

In my heart's love hath no man."

{Page vii}

But for respect to prescribed custom, I should leave this book to be ushered into public presence under the countenance of Patrick Leslie's silent introduction.

A preface, however, does shape itself into an easy chair for the scruples of the most self-distrusting occupant from which he may address himself in tendering the payment of a debt always incurred by ordinary men to their neighbours in the attainment of an end.

For my own relief I use it, therefore, for thanking those who have, in all courteous sympathy, helped me to a short review of times synchronous with the detachments of story to which this first one hundred of Australia's years of self-assertion under the Union Jack has committed her. By tradition of the past, in a measure, Australia's habit may be characteristically caparisoned in the future.

To the late Michael Fitzpatrick (awhile Premier of New South Wales), and then to the unreserved and hearty acquiescence of Henry Halloran and Deputy-Surveyor-General R.D. Fitzgerald, in obtaining for me the perusal of many official documents, a preface gives room for my grateful acknowledgments. These may have forgotten; I have not.

Among the amenities of private intercourse, I am glad to thank Philip Gidley King for enabling me to produce Journals of Allan Cunningham, of which a record in full had been long fallow among his family preserves; also the widow of the noble Carron, to whose manhood I wish to pay tribute, and by her to his memory; and her also who has honoured me by the permission to place this neophyte beneath the tutelary presence of the same Patrick Leslie.

To the boon of a public library, its able and energetic Chief Librarian, R.C. Walker, and his considerate, cordial, and courteous coadjutor, D.R. Hawley—not forgetting the politeness of the active officials therein—I have now a chance of bearing warm testimony.

To the friend to whom I dedicate this redemption of a pledge given to himself when in life, and who procured for me the accompanying specimens of Cook's Log and handiwork, it is too late to address myself. Those who inherit his cherished name may accept my meaning and regret.

The chagrin shared with others now gone, that the days of "our" Darling Downs, on which we breathed a then new element, and revelled in the elastic aspirations of the squatter of the olden time, should fade out of the freshness of their dawn; the aim, that objects wrought out by single enterprise should be fixed to the right name; the fear, that as years fall farther and farther back, the impress of many a notable occurrence, whether affecting time, place, or person, the progress of squatting exploration or that of locality, might fall back with them into the haze of forgotten or irrecoverable things, or, what is more fretting, into the fogs of future distortion and assumption—have all spurred this "small chronicler of his own small times" to present himself to the "some few" yet living to whom the recital may yet bring reflection, whether of personal interest or not; and to those who follow, mindfulness of some worthies gone before, whose names may plead the claim of whilom companionship and attachment in bush or town, prosperity or adversity.

Out of the sunny years of her who called our Queensland into her lot, have the purer rays been shed upon it which have lit up the latter, the happier half of Australia's age.

May not the last, the youngest branch of Australia's growth, bud out in hope, yet more loyally grafted upon the name of her who gave it as the days consolidate its own Centenary?

HENRY STUART RUSSELL.

North Willoughby,

Sydney,

N.S.W.

|

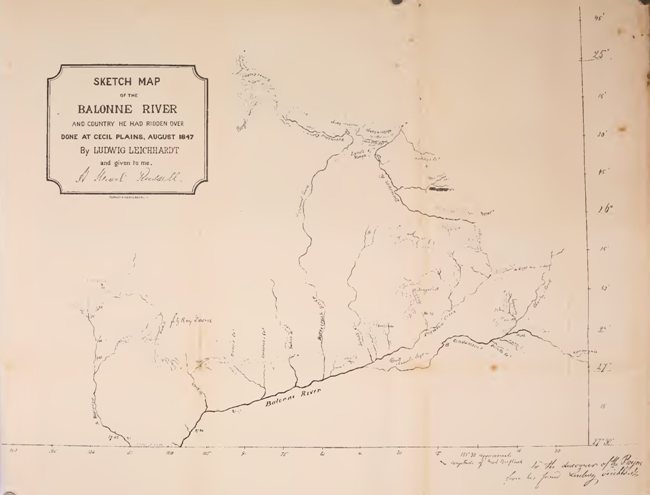

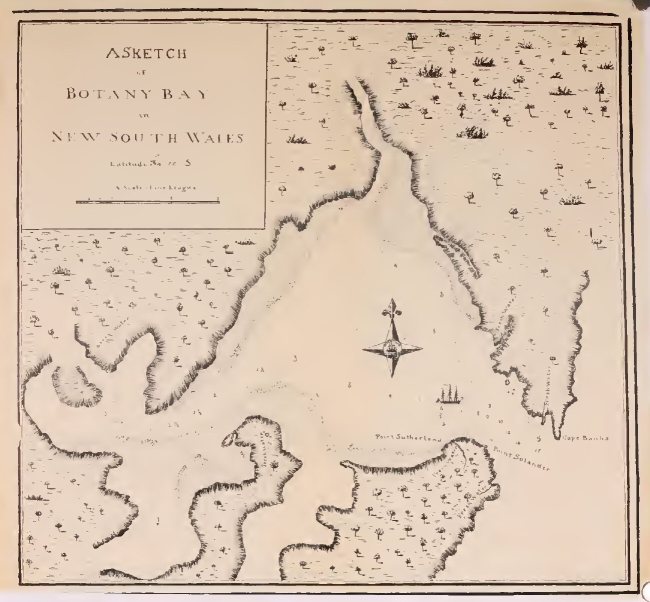

Early Explorers—Fernandez de Quiros—Torres—Torres Straits—Cook—Galamp de la Perouse—Delangle—The Times—Byron's Birth—Norfolk Island—Lieutenant King—Bass—Richard Dove—Atkins—Sydney Gazette—Flinders—Memorable execution—South Head Lighthouse—Fort Macquarie—Territorial Seals—Commissioner Bigge—Allman—Lang—H.M.S. "Britomart". Newcastle—The "Mermaid"—Port Macquarie—Oxley's coast survey—Ports Bowen and Curtis—Moreton Bay—Strange tale of bewilderment at sea—The River Brisbane—Habits of coast natives—Sir Francis Forbes—John Stephen—John Carter—Gordon Bremer—Port Essington—Melville Island—Oxley in the "Amity"—The "Australian"—Trial by Jury—Cunningham—Amity Point—Official visit to Moreton Bay—John Macarthur—Francis Stephen—Red cliff Point—Edenglassie—Fort Dundas—Raffles Bay—The Cobourg Peninsula—Patrick Leslie—Darling Downs—Leichhardt—The "Lady Nelson"—First despatch from Melville Island—George Miller—Port Essington again—Bremer in H.M.S. "Alligator"—Letter to Sir George Gipps—Owen Stanley—H.M.S. "Rattlesnake"—A Cape York rescue—Collapse of North Coast Settlements—Keppel in H.M.S. "Mœander". Retrospection—Prospects—Thomas Hobbes Scott—Rex v. Robert Cooper—Van Dieman's Land—Governor Darling—Major Lockyer—Military Discipline—Captain Bishop—Maurice Charles O'Connell—Surmises respecting our Watersheds—The River Macleay—Captain Logan—Stradbroke Island—South Boat Passage—H.M.S. "Warspite"—Sir James Brisbane—The River Tweed—First "Daily"—Logan's Walk—"Isle of Stradbroke"—Dunwich—Rous Channel—The River Logan—Captain Philip King in the "Mermaid"—Thomas de la Condamine—Henry Grattan Douglas—Fort Wellington—Rev. C.P.N. Wilton—Allan Cunningham Fate of La Perouse—Thomas Livingstone Mitchell—Gallows in 1828-9—The River Clarence—Colonial Botanist Frazer—Swan Port—Stapylton—William Grant Broughton—Allan Cunningham—Leslie—Leichhardt—Port Macquarie Free—Commandant Logan—"Surprise" and "Sophia Jane"—Runaways—Agricultural Company at Newcastle—"Specials"—Lord Howe's Island—Benjamin Sullivan's Scheme The "Squatter"—Our First Bishop—E. Deas-Thompson—John Blaxland—A. McLeay—The "James Watt"—Doubly Wrecked—Lang's "Minerva"—German Clerics—Presbytery of Moreton Bay—Sir Maurice O'Connell—Captain King—Crown Lands Police—Squatting Bill—Withdrawal from Moreton Bay—Major Cotton—Commissioners of Crown Lands—Confusion of names Allan Cunningham's Journals—Blaxland, Lawson and Wentworth—Blue Mountains—Hovell and Hume—Segenhoe—Potter Macqueen—Macintyre—Dartbrook—River Page—Dividing Range—Liverpool Plains—Oxley's River Field—Melville Hills—Goulburn Vale—Barrow's Valley—Lushington Valley—Vansittart Hills—Mitchell's River—Cod Catching—Effects of Drought—Buddle's River—Wild Cattle—Stoddart's Valley—Oxley's Peel—Drummond Ranges—Carlyle's and Little's Hills—The "Cone Masterton"—The River Dumaresq—Macintyre's Brook—Indians—The River Condamine—Darling Downs—Peel's Plains—Canning Downs—Harris Range—Mount Dumaresq—Millar's Valley—Logan Vale—Mount Warning—The "Gap"—A Glimpse Eastward—Homeward Return—Anderson's Brook—The River Burrell—Shoal Bay. Cunningham on the East—Logan—Brisbane—Limestone Station—The "Gap"—Fraser—Mount Warning—Cowper's Plains—Canoe Creek—The River Logan—Birnam Range—Letitia's Plain—"High", or "Flinder's" Peak—Mount Dunsinane—Mount Warning—Innes Plain—Erris Vale—Ascent of Mount Lindesay—Macpherson's Range—Coke and Borough Heads—Glen Lyon—The River Richmond—Mount Clanmorris—Hughes' Peak—Mount Hooker—View of the Sea—Mount Shadforth—Wilson's Peak—Minto Craigs—Mount French—Knapp's Peak—Dulhunty Plains—Rattray Plain—The River Bremer—Logan returns to Brisbane—Limestone Hills—Starts in search of the "Gap"—Mount Forbes—Bowerman Plain—Finds the "Gap's" Eastern Face—Threads the "Pass"—View of Darling Downs—Mount Mitchell—Mount Sturt—Tempest in the "Gap"—Return—Bainbrigge Plain—Mount Fraser—Mounts Edward and Greville—Arrive at Limestone—Remarks—Lockyer's Boat Excursion—Cook—Cunningham—Arthur Hodgson—Patrick Leslie—Leslie's Diary—Dobie—Peter Murphy—Falconer Plains—Walter Leslie—New England—The River Clarence—Admiral King—Garden and Bennett's Station—Toolburra—Glengallan Creek—Canal Creek—Bannockburn Plains—Fresh Start with Stock—Wyndham's—Condamine—Further Exploring of Darling Downs—Hodgson—Etonvale—King and Sibley—Fred Isaac—Leslie's Recollections Petty's Hotel—Letters of Introduction—Aldis' Cigars—Arthur and Pemberton Hodgson—Todd—Buying a Horse—Brown the Saddler—Major Barney—Disadvantage of a Name—Sydney as it seemed to me—Australian Club—En route to New England—Newcastle—Cox's Hotel—Paddy Grant—Lettsome and Archibald Boyd—Black Creek—Hughes and Isaac—Colburne "Old Soldiers"—Patrick's Plains—Cullen's Inn—Singleton's—Muswellbrook—Skellatar—Bengalla—Overton—Nagoa—St. Helier's—Cox—Allman—Aunty Bell—Nowland's Inn—Aberdeen—Potter Macqueen—Scone—Chivers' Inn—The River Page—Denny Day—Currabubbula—Charles Hall—Killalla—Salisbury—Hodgson's Highwayman—Denne's Station—Cashiobury—"Cocky" Rogers—Back to Sydney—Reverend Robert Allwood John Allman—Arthur Maister—Dr. Bland—Owen Stanley—H.H. Browne—Gilbert Elliot—Rape of the Coat-tails—Boydell—Owen Macdonald—Ride to the South—Murrumbidgee—Sharp—The Station Sold—Cavan—Hallett, of Oriel—Yass—Road back to Sydney Patrick Leslie—The s. "Victoria"—Henry and Alfred Denison—Edward Hamilton—Hodgson and Elliot—Frank Forbes—Archibald Bell—Stephen Ferriter—Glennie—Dr. Bowman—Loder's—Allan Macpherson—Charles Hall again—River Peel—Stubbs and Irving—Dalzell—Milne—Rusden—Werris' Creek—St. Aubin's—Captain Dumaresq—Denny Day and Frank Allman—Magnus McLeod—Butler—St. Helier's—Henry Denison and Paddy Grant—Pemberton Hodgson—"Tinker" Campbell—Cameron—McAllman—George Gammie—Bergen-op-Zoom—George Macdonald—Captain O Connell—Cash's—The River Bundarrah—Clark and Ranken's—Wyndham's—Fraser's Creek—Gregory Blaxland—Leslie's Marked-tree Line—The Severn—The "Fiver"—A. Hodgson and Fred. Isaac from Darling Downs The Condamine Grass Trees—Cocky Rogers again—Exploring Etonvale Creek—A Yahoo—Cunningham's "Gap"—Westbrook—Hodgson's "My Word!"—Limestone—Arrest—George Thorne—George Thorne's Wife—Pleasant Quarters Owen Gorman—John Kent—Dr. Ballow—Andrew Petrie—Eagle Farm—Stephen Simpson—William Henry Wiseman—Mrs. Gorman—Logan's Reign—Cunningham's Gap—Joe Archer—Gorman's Gap—Baker or "Boralcho"—The Drummer's—Toolburra—Clifton—Novel Watch-pocket—Dalrymple—A Headlong Meeting—Blacks at Lockyer's Creek—Hell's Hole—Etonvale—Elliot—Shearing—Black Tommy George Leslie—The first Clip—Trip to Brisbane—Arthur Hodgson again—Mosquitos—Thorne and Cunningham's "Gap"—Plough Station—Ralph Gore—To Sydney with Hughes—Henry and Fred. Isaac—Westbrook and Jock Maclean—Gowrie—Denis—Scougall—Coxen—Myall Creek—Jimbour—Samuel Stewart—Wingate—Tummavil—Rolland and Taylor—Yandilla—Talgai—Ellangowan—George Mocatta—Tent Hill—Helidon—Somerville—Fred, and Francis Bigge—Evan and Colin Mackenzie—McConnell—Balfour—My Brother Sydenham—Run to a Rencontre—How Syd. trumped a Trick—Frank Allman—Pagan—Skellatar—Milburne Marsh and Miss Marsh—David Scott—Bengalla Races—Helenus Scott—Glennie—Bundock—John Cox—"Dick" Glover—Matthew and Charles Marsh—Darby and Goldfinch—Morse—Armidale—Ben Lomond—Horses Lost—Etonvale—Murray—Rose—Brooks—Frank Hodgson—Arthur's Round Table—Frank Forbes—Search for a "Run"—Cecil Plains—Back at Betty's Hotel, in Sydney—John Allman—Campbelltown—Captain Allman—John Hurley—Sir Thomas Mitchell—Dr. Wallace The "Shamrock" to Moreton Bay—Governor and Suite—Jolliffe—Milburne Marsh's Flying Shot—Cleveland Point—First Queen of May on Darling Downs—Dr. Goodwin—James Canning Pearce—Fife—Aikman—Simpson's Homœopathy—Quixotic—Chambers' "Edward"—Pinis Petriana—An Agreement Boat Trip to Wide Bay—Edward Baker—Walter Wrottesley—Jolliffe—Mocatta—The River "Morouchidor"—"Petrie's Head"—Aboriginal Doctoring—Bracefell—Brown's Cape—The "Stirling Castle"—Wreck—A "Tourr"—Mrs. Fraser—Her Escape—Boppol—Southern Entrance into Hervey's Bay—Capsize—A Chorus—A Fog—Sheridan—Puzzled—Fire-flies—"Gammon Inch" Bunnia-Bunnia Range—Jolliffe's Beard—The River Monoboola (now "Mary")—Difficulties on nearing Mount Boppol—"Old Bill"—Arthur Hodgson in the "Canopus"—Derhamboi—Strange Scenes—A Watch Found—Back to Brisbane—Pamby-Pamby's Good-bye—"Makromme"—Derhamboi's Au Revoir!—Life with the Ginginbarah—Native Character—Shells for my Sisters in England—The Hunting Phocœna—My Leaf Written in Gaol—Hopes of the Forlorn—Cannibalism—Cooking—Stolen Pleasures Narratives of the "Stirling Castle's" Wreck—Death by Torture—Gathering Doom—Choice of Two Horrors—Garbled Account of Rescue—Base Ingratitude—Bunnia-Bunnia—Araucaria Bidwellii—Female Cannibal Priviliges—The Bundinavah—Courting on the Monoboola—Contract Sealed—Character of the Contract—Aboriginal Domestic Habits—Natural Learning Patrick Leslie—Denny Day—Sir Thomas Mitchell—Stapylton—Execution of His Murderers—The "Piscator"—Leslie and Darling Downs—Lettsome and Boyd—The River "Albert"—Moreton Bay Progress—Glover, from Bathurst—Peter Quack—John Hill and Christopher Gorry—New Road Over the Range—Francis Bigge Shot—Overland to Wide Bay—Eales' Sheep—Superintendent Last—A Christmas Eve Night—Overland to Port Essington—Orton—Black Jemmy—The "Gulf Stream"—A Comet—Bell and Cameron—Thomas Sutcliffe Mort—Cooranga—Blacks Surprised—Henry Denis—A One-eyed Murderer Sir Charles Malcolm—Glover—Sydenham Russell—Letters—Cecil Plains—Burrandowan—A Day and a Month of Dying—Commissioners Macdonald and Rolleston—Cambooya—Pot Luck—Hodgson a Butcher-Boy—Pie-bald Strife—"Gourmand's" in Brisbane—Egg Trick—Table-d'hôte in Queen Street—The Horse "Mentor'"—Benedict Bracker Ludwig Leichhardt—Our First Meeting—G.K. Fairholme—Pipe Ponderings Over—Port Essington—Sandy Blight—The Doctor opens our eyes, and his own are fixed Northward—My Stockman, William Orton—Deliberations—Leichhardt Prepares himself in Sydney—Return—Route—Ruin—Resurrection—Reaction—Second Start—Swan River—Sickness—Third Start—Fading away Robert Little—Kearsey Cannan—Contemporaries—Duncan—Thornton—Sheridan—Brisbane Celebrities—Ralph Gore—Invitation to Bustard Breakfast—An Unforgotten Rebuke—The Loss of the "Sovereign"—Waste Lands—Port Curtis Settlement—Wickham—Moreton Bay Courier—Darling Downs Gazette—Brisbane v. Cleveland—A Visit by Night—Brisbane Racecourses—Butterflies—Caterpillars—Land—Wentworth—Labour—Tea-fight—Burnett—H.M.S. "Orpheus"—Dr. Lang's Emigrants—The Close of my Darling Downs Days Edmund Kennedy—From Sydney by Sea to Rockingham Bay—Thence by land starts for Cape York—William Carron's Journal—Bad beginning has a worse end—Carts useless and left behind—Horses dying are eaten—Terrible Obstacles—Rain—Food filched—Watching Stores—Party left at Weymouth Bay—Doom's Dallyings—A Skeleton Remnant—Carron and Kennedy—Kennedy's Death—Jacky's "Ariel"—A Canoe Chase—Dust and Ashes—Faithful to the end New South Wales' Leap Year—Her growth—Charles Kemp—Spectre of Separation—Ghost of Ruin—Prevention—A Continuance Bill—Sir Robert Peel and Vernon Smith—Power of a Word—London Colonial Gazette A Day with the "Separation" Pack—Lang and Lowe at the Meet—Philippic from Port Phillip—Lang and the "Lima"—Hobson's Choice—A Hook for Separation—Moulding for a new Cast—Lang impeaches Grey—Lang's aim at Separation—His Land Orders—Lang's portly President—Lang's League—Lang for Sydney—Henry Parkes for Lang—Lang elected—"In the name of the Prophet Figs!" Patrick Leslie and Separation—Separation Strifes—Grey's odd trick—Leslie and Lang—Sydney Wrath—Five to three against "Jackeroo"—Hodgson on Separation—Public Sentiment—Apology for "Exiles"—New Constitution Bill—Clauses fifty-one and fifty-two—Denunciation—Indignation—Exultation—Termination. Aspiration Extracts from Cook's Journal (Hawkesworth).—Cape Byron—Mount Warning—Points Danger and Look-out—Moreton's Bay—Cape Moreton—Glass Houses—Double Island Point—From Bustard Bay to Cape Townshend—Thirsty Sound—Conway—Gloucester—Whitsunday—Grafton to Cape Tribulation—Coral stricken—The Endeavour River—Capes Bedford and Flattery—Breaking through the Barrier Reef—Providential Channel—Weymouth Bay—Bolt Head—Sir Charles Hardy's and Cockburn's Isles—Cape York—Newcastle Bay—Possession Island—Cape Cornwall—Booby Island—Return by Timor, Batavia, and Cape of Good Hope—Lands at Deal Extract from Flinders' Journal.—Epitome of his Introductory Review of Early Discoveries—What Flinders had to do in the sloop "Norfolk"—Sugar Loaf Point—Shoal Bay—Point Skirmish—Pumice Stone River—Hervey's Bay—H.M.S. "Investigator"—Do Wide and Hervey's Bays join?—Gatcombe Head—Port Curtis—Keppel Bay—The "Lady Nelson"—Parts company—Threads the "Needles"—The Gulph garnished—"Xenophon" will not Retreat—Sink or Swim with the "Investigator's" Rottenness—By North and West Coasts round Cape Leeuwin in his rotten Ship—To Port Jackson. Journal of an Excursion up the River Brisbane in the Year 1825, by Edmund Lockyer, Esq., J.P., late Major in His Majesty's 57th Regiment of Foot. General Order.—With respect to the Military posted at Penal Stations. Government Order.—Coasting Service. Proclamation.—Port Macquarie, Moreton Bay and Norfolk Island as Penal Settlements La Perouse's Relics.—Brought to Port Jackson by Captain Dillon, commanding the Honourable East India Company's ship "Research". Government Order.—Major Mitchell's appointment as Surveyor-General. Government Order.—The Rev. W.G. Broughton, Archdeacon, Member of the Legislative and Executive Councils. Proclamation.—General Thanksgiving. Proclamation.—Port Macquarie open to Settlers. Account of Logan's Murder.—The Funeral—Captain Clunie's Letter. Proclamation.—Checks upon Excessive Punishment of Convicts. Major [John] Campbell's Journal.—Record of Settlements on North Coast—Melville Island—General Description. Proclamation.—Boundaries of the District of Moreton Bay—Stephen Simpson appointed Commissioner of Crown Lands. First Sale of Land at Brisbane.—Buyers and amounts. Extract Sydney Gazette.—Arrival of the horse St. George and Stock from Bathurst. [ILLUSTRATIONS]Map of the Balonne River. A Sketch of Botany Bay [Cook]. A Plan of the entrance of Endeavour River [Cook]. Fac-Simile portion of Muster Roll of H.M.S. Resolute with Cook's Signature—1760 [above]. Fac-Simile portion of cook's Log of H.M.S. "Endeavour"—May, 1770. [below]. |

{Page 1}

King Arthur made new knights

to fill the gap

Left by the the Holy Quest.— Tennyson. (The Holy

Grail.)

Assuredly the gallant Pedro Fernandez de Quiros must have been possessed by some of the "sacred madness" of King Arthur's bard when as he first gazed, as he thought, upon the coral-gripped coast of the new land which King Philip of Spain had sent him to seek, he shouted in reverent joy with doffed sombrero: "Australia del Espiritu Santo!" But was "Australia" the utterance, or was it "Tierra"? 'Twas not for de Quiros to discover his own error. Choosing one course for further discovery, he directed his Lieutenant to take another in the second ship, and so they parted in 1606. Superstitious dread prevailed over the discipline of his own, and he was compelled by his mutinous men to return to Peru, which he reached in disgrace, ever attendant upon failure. His Lieutenant, Luis Vaes de Torres, soon found that the Admiral had saluted but an island—probably one of the New Hebrides—continued his course westwards, bore away along the south coast of New Guinea; unwittingly fixed his eyes upon the true "Tierra Austral"; upon the "very large islands" which the Cape, since called York, presented to his bewildered sight, ere he stood away to the north, threading his way through the mazy channel which exposed his commander's mistake.

Torres had unconsciously fulfilled the Holy Quest. The memory of and monument to his name are baptised and bathed by the isle-fretted waters which bear it.

In John Bull justice did a native of our own British island stamp "Torres" with his hand of authority as hydrographer to the Admiralty upon that strange channel which had already begun to be the promise of a grand highway claimed by, but not destined for the sovereignty of that flag under which Torres had sailed.

The most authentic registration of Queensland's birth was thus declared from the far north; her future growth was nourished and confirmed from the far south. Among the first forms of a new shore brought to light, she has derived her existence from that which was delivered last by the labour of our Yorkshire countryman, James Cook, Into the arms of our glad motherland.

But through what throes has the first colony planted in this our Australia been nursed to its stature, that it may bear its own part, and send forth its own offspring to bear theirs on the great stage upon which in these years of grace, 1887-8, it and they are summoned to enact the several characters allotted to them, and as yet rehearsed by the help of the common prompting of religion, race, kindred, and country.

It is by the finger-posts of incident in colonial life that the tracks of a community's social rise and progressive ability may be faithfully followed and run out, irrespective of the governing element. Whether of good or evil, worthy or unworthy, noble or ignoble report, the course of events proves a people's character; whereas a religious and political history, even of a new country, compiled from a mass of wrestling opinions, can be taught and learnt but by the commonwealth's outcome up to a present—a present which can find no end while the world is.

The former—my task—is an easy one: the latter, one which only rare ability and genius dare challenge. Yet the one may allure the interest and amused attentiveness of the many, who do not care to dig up or into the thirsty ground of theory, nor sink into the quicksands of inquiry which cannot be solidified.

For instance, who that dwells in this land of bright token can take up an almanac, and fail to exult in his secret soul that on the 20th day of January, 1788, our fellow countryman, Arthur Phillip, had saved it for us "Britishers" but by a few days from becoming the rightful refuge for the Frenchman's "folies"; that two days after he had taken possession of the country in the name of the United Kingdom, established his head-quarters on the bay-sporting waters of Port Jackson, and in all chivalrous courtesy "fended off" "l'Astrolabe" and "la Bussole" with their gallant commanders, Jean Francois Galamp de la Perouse, and his friend Delangle, to the less hospitable shores on which they met their sad fates? Is the fact that the same month of the same year—1788—hailed the birth in our realm of a people's new and giant power—the power of the press, the fourth estate—in a dingy room at Printing-House Square, whence on the first of its days issued forth the first cry of the infant Times, now stalking forth in strength equal to a nation's leverage, worth no grateful glance? Can the nascent glow of Australia's poetic aspirations bear no reflective companionship with the spark which kindled the simultaneously new-born Byron's genius? Are all incurious to the fact that Norfolk Island was made a dependency of New South Wales on the 13th day of the month following, under Lieutenant, afterwards Captain, and then Governor King?

Is it not worth a glance that on the 26th of September, 1791, Lieutenant-Governor, afterwards Governor King, had arrived in the "Gorgon", having received our territorial seal, with authority to grant pardons absolutely or conditionally? Nothing to any housewife that in 1796 coals were being received in Sydney from Newcastle? nor to the admirers of sea-bred pluck that Dr. Bass had thrown open the straits which wear his name, and returned in his whaleboat thence to Port Jackson in February, 1798? Are there none now who would be surprised that until December, 1800, no copper coin was in circulation in the colony? None now living who may read with namesake interest the first noteworthy death in New South Wales, that of Judge-Advocate Richard Dove; none to lift up their eyebrows at the recorded name of his successor, Richard Atkins?

And then, a smart step onward on March 5, 1803, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, published "by authority", coupled with the drawback—important enough in those days—of the report brought to Sydney by him to whom the coast of New Holland had become so much indebted for development, Matthew Flinders, of the loss of the "Porpoise" and "Cato", upon his arrival within the Heads on September 8th, in an open boat.

Is there no sensation attendant upon the announcement of horrors presumably lawful (in the type of the period), and tendered in a somewhat cynical regard for authority one day of this year: "Memorable execution(!).—Joseph Samuels, for burglary, was three times suspended; first, the rope separated; second, it unrove at the fastening; third, it snapped short! The Provost Marshal, Mr. Smith—a man universally respected—compassionating the criminal's protracted suffering, represented the case to the Governor, who was pleased to reprieve him"?

Was there no thought for defence in those troublous days of antipodean wars? Nor for light in those days of darkness? There was; for on the 18th of July, 1816, Governor Macquarie laid the first stones of the tower which makes his name redoubtable, and of the South Head Lighthouse, pulled down not long ago, and then put up again the brightest beacon of the seas! The old Seal, too, worn out, not probably by the frequency of pardoning, but by ceaseless attachments to hanging warrants, was replaced by a new Territorial Seal, sent with a warrant, by the clemency of the Prince Regent, in the November following.

Why should we decline to refresh our knowledge of the stirring times during the chaotic reign of Governor Bligh for one year, five months, and thirteen days; or mark the record of a new era which set in with the arrival of John Thomas Bigge, the Honourable Commissioner of Inquiry, consequent upon Bligh's eviction, in the ship "John Barry", with his secretary, Thomas Hobbes Scott, on the 25th September, 1819? Or, beginning already to creep away to the northward, to mark that a gallant officer of the 48th Regiment, Captain Allman, whose name is still held high in Campbelltown esteem, and in our midst, in memory of a fine old soldier and impartial magistrate, was sent forth to establish a penal settlement at Port Macquarie?

Coming apace to household names of our own years, the preaching of his introductory sermon by Dr. Lang in Sydney, on June 8, 1823, will surely make many prick up their ears.

And how strangely it sounds now that on the 8th of the preceding month Thomas McVitie was magistrate for the week! That the harbour of Port Jackson presented "a novel and gay appearance on the Sunday before, as six vessels were under sail at once! Five to go through Torres Straits, Captain Peach, of H.M.S. "Britomart", being commodore of the squadron; that this smart vessel saluted Point Piper en passant, which was promptly answered by our respected naval officer (and postmaster), Captain Piper"!

{Page 21}

For not this man and that man, but all men make up mankind, and their united tasks the task of mankind. How often have we seen some adventurous and perhaps much-censured wanderer light on some outlying, neglected, yet vitally momentous province, the hidden treasures of which he first discovered, and kept proclaiming till the general eye and effort were directed thither, and the conquest was completed; thereby, in these his so seemingly aimless rambles, planting new standards, founding new habitable colonies in the immeasurable circumambient realm of nothingness and night.—Carlyle. (Sartor Resartus).

How fast within our first half century did the necessities of New South Wales, with respect to the classification of her criminals, and the infliction of secondary punishment, compel her in her apparently dismal destiny's fulfilment to work out under such degrading associations her sad course; blindfolded to all considerations but those by which she could render service to the old home by relieving it of the presence of outcasts and ne'er-do-wells. The establishment of these very depots of guilt became the direct guidance to the exploration of this land. Let us see. Newcastle was the first affiliated prison-house; but on the 11th of September of 1823 the Government cutter "Mermaid"—which plays so frequent a part on the north coast henceforth—sailed with stores to Newcastle, from which dependency about forty prisoners were to be transferred to that of Port Macquarie, as the former is to be no longer considered a "place of banishment" for our felons; and on the 16th of October, the Surveyor-General, John Oxley, had received instructions from Governor Brisbane, upon the advice of Commissioner Bigge, "to proceed northward as far as Port Bowen, Port Curtis, and Moreton Bay; to examine them, and report as to forming in each spot, if fit for the purpose, a new settlement, to which all the convicts not usefully employed on the old settlements, as well as the refractory and incorrigible, were to be removed, and employed in the clearing and cultivation of land, &c., with the view, further, of removing to them, or any one of them, the prisoners then stationed at Port Macquarie, which from the excellence of the soil, the fineness of the climate, and its convenient distance from Sydney, the Governor was desirous of throwing open to free settlers."

And so, accompanied by Uniacke, the Surveyor-General proceeded to Port Macquarie, which they found flourishing after its two years' occupation; a town laid out in "streets of straight lines, handsome esplanade, barracks for 150 soldiers, neat commodious officers' quarters, comfortable huts of split wood, lathed, plastered, and white-washed, for prisoners, garden attached to each; fruit trees, maize, and sugar-cane growing very luxuriantly," and natives of exceptionally fine mould mixing with the whites in a most friendly manner, who in consideration of being "victualled from the King's store", perform very efficient duty as a constabulary, especially in pursuing and bringing back runaways "dead or alive."

Their next visit was to Port Curtis; here they were not so well pleased: harbour difficult, vegetation scanty, timber none but what would do for firewood. They found no fresh water nearer the shore than twelve or fourteen miles, in a rapid river which they named the Boyne, up which they came to a succession of rapids, the banks "highly picturesque, the hills covered with wood, and the plains well grassed. The result, however, was that the place was unsuitable, and that convict labor there would be wholly thrown away."

So, on return, they entered Moreton Bay, discovered by Cook, and visited by Flinders. Dropping anchor, a number of natives rushed down to the shore, among them one who appeared much larger in frame and lighter in colour than the others, who, advancing to a point opposite to the "Mermaid", hailed her in English. A boat was sent off, and as it drew towards them, the natives showed many signs of joy, hugging this man, and dancing wildly around him. He was perfectly naked, daubed all over with white and red ochre. He was soon discovered to be an Englishman, and so bewildered that little could be made of him that night. However, on the morrow Uniacke took down his narrative in writing, and this is by far the most curious and interesting paper in Barron Field's collection. His name was Thomas Pamphlet; had set out with three others—Richard Parsons, John Finnigan, and John Thompson—from Sydney in a large open boat for Illawarra or the Five Islands (at that time the popular name for that place) to get cedar; met with a violent gale which lasted live; days, which drove them, as they imagined, to the southward as far as Van Dieman's Land. Under this delusion they kept to the northward, suffered terribly from want of water for twenty-one days; John Thompson died of thirst; then were wrecked on Moreton Island, which they still believed to be to the south of Port Jackson. Parsons and Finnigan insisted some six weeks before upon another attempt northwards for Sydney; he had gone with them about fifty miles, become too foot-sore to proceed, but got back to this tribe—Parsons and Finnigan having quarrelled, the latter also had returned, but was away at present on a hunting excursion with the chief. Parsons had not since been heard of.*

[* It will be seen, however, that in January of next year Parsons was discovered.]

Finnigan came in the following day; and, guided by their information, Oxley proceeded in the whaleboat to examine the mouth of the river which both had assured him ran into the south end of Moreton Bay. By sunset of that day they had ascended this river about twenty miles. The next day the satisfaction they had at first felt increased. Oxley felt "justified in believing that the sources of this river were not to be found in a mountainous country, but rather that it flows from some lake which will prove to be the receptacle of those interior streams crossed by me," he observes, "during an expedition of discovery in 1818."

In a review upon three works which were published in London in 1826, viz., by W.C. Wentworth (1824), Edward Curr (1820), and Barron Field (1825), appears the following: "The name given to this important river is the Brisbane. That it derives its waters from the lake or morass into which the Macquarie falls, and from those numerous streams which were crossed by Oxley in 1818, all running to the northward, seems a very reasonable supposition. He was able to trace its course forty miles from its mouth, and he could see in the same direction, viz., in the south-west, the abrupt termination of the coast range of mountains; and the distance from Moreton Bay to the lake or morass of the Macquarie is not more than 300 miles. The discovery of this river may cause those to hesitate who so positively assert that none of any magnitude fall into the sea from New Holland. Captain Cook discovered Moreton Bay; it was well known to Captain Flinders, who anchored his vessel both above and below the mouth of this river, and passed it twice in his boats, but it was concealed from him by two low islands."

Pamphlet said that nothing could exceed the kind attention paid by the natives to the shipwrecked seamen; they lodged them, hunted and fished for them, and the women and children gathered fern root for them, painted them twice a day, and would assuredly have tattooed their bodies and "bored" their noses but for their dislike to the process. Not only did these Moreton Bay natives deal with them so kindly, they met with similar treatment among all the tribes with whom they had met in their wanderings to the north. Of the habit of boiling water they all seemed to be ignorant. Pamphlet had saved a tin pot, in which, on one occasion, he had heated some water; it began to boil, and the anxiously-watching savages took to their heels, shouting and screaming. They would not draw near again till he had poured it away; nor were they, in his sojourn, ever reconciled to the operation. Each aboriginal had the cartilage of the nose pierced; many wore large pieces of bone or stick (supplanted in after days by the white man's pipe) thrust through it. The women, as at Sydney, had all lost the first two joints of the little finger of the left hand, but the adults had not, as at Port Jackson, one of the front teeth extracted. The women were daily busied in getting "dingowa", fern root, for subsistence, and making bags of network from rushes. The men made the fishing and kangaroo nets from the bark of the kurrajong (hibiscus heterophyllus). The fishing stations and grounds of each tribe were some few miles apart; and they would change from one to another as the fishing or game began to fail. Their huts were of wattle bent into an arch, interwoven with boughs, covered with the bark of the tea tree (melaleuca armillaris) and impervious to rain. Some would hold ten or twelve persons. Pamphlet declared that during a sojourn of seven months he never saw a woman struck or ill-treated! The men would quarrel—their fights were frequent, often ending fatally. The common usage was for a champion on either side to fight it out fairly in a ring made for the occasion. He saw one, he said, of these duels. At a spot chosen was a circle about twenty-five feet in diameter, three feet deep, and surrounded by a palisade of sticks. The two combatants entered it, parleyed awhile with violent gestures, plucked their spears from the ground; one was pierced through the shoulder; he fell, and was carried off by his friends, the lookers-on departing with loud shouts on all sides. Reconciliation succeeded, and that again was hailed with loud shouts, dancing, and wrestling, after which they all joined in a general hunt for a week.

Instrumental in the discovery of the river Brisbane, these white castaways have thus appeared upon the scene. Let us now return to Port Jackson. We shall, for the first time, hear of one whose name became a household word, not only in this colony, but through his sons, in years afterwards, on Darling Downs. In the person of Sir Francis Forbes, the bench attained the honour of a Chief Justice who, by the brilliancy of his talents, shed new light upon its records, as his estimable character and broad philanthropy did upon the darker pages of the history of New South Wales. It was the beginning of a new era in colonial being. Captain Johnson, in his good ship the "Guildford", did deliver upon these shores our first Chief Justice, his wife and family, on the 5th of March, 1824. The same day the formal promulgation of His Majesty's New Charter of Justice for the Colony of New South Wales took place at the Government House, the Court House, and the Market Place of Sydney, and the Chief Justice took his seat on the bench. The 11th of the August following proclaimed—as effacing what may be termed the martial control—a Legislative Council, established by Royal sign-manual, as being in existence under the hand and seal of the Governor-in Chief; and in the same month was hailed the advent of the first Solicitor-General and Commissioner of the Court of Requests, John Stephen, with his family, in the "Prince Regent", and the first Master-in-Chancery, John Carter, with his family, in the same ship.

Another spurt Northward, Ho! through Torres Straits this time, encircling Queensland and all that she contains, commemorates the month of August, 1824, for H.M.S. "Tamar", commanded by Captain Bremer, C.B., accompanied by the "Countess of Harrington", taking a civil and military establishment, sailed for the north coast of "Terra Australis" on the 24th, for the purpose of founding a new settlement in the vicinity of Melville Island, which, with Port Essington, becomes so much identified with a Queenslander's retrospect, that the energies expended upon that spot should not, with the settlements themselves, be abandoned through exhaustion. Who can forget that Port Essington, at least, was Leichhardt's refuge?

Pending the Melville Island expectations, let us see again what part Moreton Bay is preparing to take in our Australian programme.

In September we find our indefatigable Surveyor-General, John Oxley, again at work. He has sailed in the brig "Amity" with a civil establishment, prisoners, and stores, to plant a new settlement somewhere in Moreton Bay. As a guard, a detachment of the 40th regiment, the officer in command Lieutenant Butler. The Commandant-elect, Lieutenant Miller of the same regiment; his suite completed by a storekeeper, subordinate officers of various designations, and a number of volunteers. The King's Botanist, Cunningham, accompanies the Surveyor-General. Upon John Oxley falls the responsibility of fixing upon the site most eligible for this new dependency.

What says October of 1824 to the credit of our country? Liberty of the Press! thanks to Sir Thomas Brisbane. The publication of an independent weekly newspaper—the Australian, on the 14th.

Trial by jury on the same day obtained in the Quarter Sessions Court.

Did these boons follow in the Chief Justice's train?

Its 21st day brought back our brig "Amity", Captain Penson, with the Surveyor-General and King's Botanist. Our new settlement was established for the while on the very shores of Moreton Bay, at a spot called Red Cliff Point, on its northern margin. It was deemed peculiarly eligible, although it had drawbacks from want of safe anchorage. Oxley went thence up the river about forty miles beyond the place he had ascended it in December last. He then gave his opinion that the river communicated with the interior waters, and it was to be regretted (it was then said), that no proof of that being a fact had been yet obtained. However, his party found fish hitherto known only in the western shed, and that circumstance afforded a strong presumption of the surmised communication. The tree now known as the "Moreton Bay" Pine (Araucaria Cunninghamii), was much noticed. The King's Botanist, Cunningham, made extensive collections, and it is remarkable "that most of the plants were of genera hitherto supposed to be exclusively tropical."

It will be remembered that by the cutter "Mermaid" last year had been rescued two men wrecked on Moreton Island, and that they had spoken of one, Parsons, who had left them, and not re-appeared. About a month before the arrival of the "Amity" on this occasion, this man had returned to his old friends at the mouth of the Pumice Stone River. He had been wandering among the tribes of Hervey's Bay and the coast north of Moreton Bay ever since he had left his comrade in misfortune. For two years his dwelling among the blacks was an interesting story. In all respects he declared he had been well and kindly dealt with.

Upon her return the "Amity" passed through the southern passage into Moreton Bay, which took its name as the "Amity Point Entrance", she being the first craft to make use of it. The discovery of this approach shortened the distance by about fifty miles to the river Brisbane.*

[* Until the loss of the steamer "Sovereign", in 1847, it was the usual entrance, except in very heavy weather; after that catastrophe it was for many years "tabooed".]

The colony must have made a fresh start on the 1st of November, when the first Court of Quarter Sessions was held in Sydney; and Moreton Bay must have been on "tip-toe" in the expectation of a vice-regal visit, for on the 11th the same staunch brig "Amity" conveyed His Excellency the Governor-in-Chief (Sir Thomas Brisbane), the Chief Justice, and the Surveyor-General to sea en route to the new settlement, followed by her tender, the "Little Mars". Captain John Macarthur and Francis Stephen, Clerk to the Council, completed the pleasant party; pleasant, doubtless, in spite of the weather, which in a fit of ill-humour kept them fourteen days on the passage. The heavy gales and thunder-storms were spoken of as terrible day after day, and night after night. They entered the Bay by the north passage. The Governor and Chief Justice went up the river some twenty-eight miles, were much struck by the size of the trees on the banks, and pleased by what they saw. The natives were beginning to be troublesome at Red-Cliff Point, by continual thefts of tools, &c. Sir Thomas had decided upon removing the settlement to a spot about nine miles up the river, which would be more convenient for shipping. The Chief Justice had named the new site Edenglassie (Brisbane?). The "Amity" went to sea by the southern passage, and returned to Port Jackson in four days, on the 4th December.

In August of the year 1824, Captain—afterwards Sir James John Gordon Bremer—in command of H.M.S. "Tamar", and accompanied by the "Countess of Harcourt", Captain Bunn, left Port Jackson for the north coast of Australia, and established the first settlement thereon at Fort Dundas on Melville Island.

Melville Island and Raffles Bay were the outcome of this attempt for a few years, and afterwards Port Essington. The idea of such an extension may be best expressed by the concluding paragraph of Major Campbell's journal in the appendix. Clothed in such an opinion, common sense, which thus weighed the probabilities of the future, would find herself much out-at-elbows in these days of democratic hatred of Indian, Chinese, or Islander service. If she were suffered to look at herself in the glass, she would hardly recognise her own features, and would shrink from the ugly mask which some "larrikin-spirit" hand has bedaubed them with during her long nap.

We know how spasmodically—spasms of mercantile and monetary panics—the eyes of Sydney used to be fascinated by the enticement to hook on to the chain-trace which nature has stretched across the Indian Ocean from our neighbours in the hemisphere opposite.

To Queensland the existence of a settlement on the Cobourg Peninsula has been, I think, an unappreciated boon as yet. Not embraced by the area of her possessions, yet in reviewing the track by which she came to where she is, Port Essington becomes much identified with her career.

It was the suggestion of a direct overland connection with it which at times so highly stimulated the appetite for its realisation. The occupation of Darling Downs by Patrick Leslie gave fresh strength to the desire: the question of such a consummation became lively in town and bush. Port Essington was the northern magnet of which the attraction energised the gallantry of many an ambitious heart. Leichhardt would not, I think, have so promptly tempted the intervening wilderness but for the refuge ready for him at the end of his way.

So, out of Patrick Leslie's hands sprang the baby colony into the cradle of Leichhardt's chevaleresque design; that design was sketched perspectively through the focus which concentrated Port Essington's distinctness of welcome. The Cobourg Peninsula may yet have a grand part to play for the benefit of the land of the south.

It was admitted that the object of the Government of that day in despatching this expedition was "to open and preserve an intercourse with the Malay coast, so as to encourage and facilitate the spice trade." The latitude of the proposed dependency was about 12 deg. S., and 130 deg. E. To be conveyed thither by Captain Gordon Bremer were Captain Barlow of the 30th Regiment (Buffs)—upon whom the superintendence was eventually to devolve—Ensign Everard, twenty-four non-commissioned officers and privates of the same regiment; Dr. Turner, medical officer; George Miller, commissariat clerk in charge of the duties of that department: George Wilson, whose assistant was George Tollemache; and forty-four prisoners of the crown as workmen and mechanics. The Government colonial brig "Lady Nelson",** John, master, accompanied the "Tamar" and "Countess of Harcourt".

[** The "Lady Nelson" was a brig of 60 tons, brought from England by Lieutenant Grant, R.N., in 1800; built with sliding keels, came out of Deadman's Dock, London, on January 13th, 1800; laden at Gosport on February 9th, had freeboard but 2ft. 9in., and looked so small for such a voyage that she got the name of His Majesty's "Tinder Box".]

In the following March, 1825, the "Philip Dundas" from Mauritius, brought news to Sydney that the "Countess of Harcourt", after landing her stores at Fort Dundas, Melville Island, had called at the Isle of France, en route to England; had reported "all well" with Captain Gordon Bremer and the new settlement so far. Houses sent in frame from Sydney had been put together, a fort finished and seven guns mounted, soldiers and prisoners well "hutted", the commissariat officer Miller, getting a store completed. The official despatch from Captain Gordon Bremer gave the following particulars: "Having completed everything necessary for the expedition, sailed from Port Jackson on the 24th of August, 1824, the ship 'Countess of Harcourt', and the colonial brig 'Lady Nelson' in company. On the 28th, passed Moreton Island with a fair wind; from this period running down the east coast, anchoring occasionally, until the 17th of September, when we passed Torres Straits, and on the 20th at Port Essington, of which port and the coast between 129 deg. and 130 deg. east longitude, I took possession in the name of the King. On the 21st, at daylight, began examining the surrounding shores of Port Essington, and despatched four boats in search of fresh water. On the east side the country was much burnt up, the soil sandy and thickly interspersed with red sandstone rock, probably containing iron; trees of no great height, mostly like those of New South Wales; no water found this day. On the 22nd the search was again unsuccessful, but on the western side the soil was better, the country more open, and the trees of magnificent height. On Point Record a hole was found fenced round with bamboo, containing a small quantity of thick or rather brackish water, evidently the work of Malays, as the bamboo is not indigenous in New Holland.* Traces of natives were also found everywhere, but none made their appearance. Our parties had penetrated in various directions considerably into the country, but never found any water; however, there is no doubt that by digging deep wells it might be obtained, yet the present apparent scarcity much diminished the value of Port Essington.

[* In the seventh chapter of Explorations in North Australia, which appears in the Sydney Morning Herald of the 7th May, 1887, by the Rev. J.E. Tenison-Woods, mention is made of bamboo as indigenous, "which," however, "only grows on a few Northern rivers," he observes.]

"It is, nevertheless, one of the most noble and beautiful pieces of water that can be imagined, having a moderate depth, with a capability of containing a whole navy in perfect security, and is well worthy of His Majesty's Government, should they be pleased to extend their establishment to this coast. On the 23rd, as water had not been met with, and the season was advancing, weighed and made sail for Apsley's Strait. On the 24th, made Cape Van Dieman, and on the 26th entered the Strait and anchored off Luxmore Head, when formal possession was taken of Melville and Bathurst Islands. On the 27th, 28th, and 29th, boats were despatched in search of water, other parties sinking wells on both islands, without success. The wells produced a small quantity muddy and slightly brackish.

"On the 30th I had the good fortune to find a running stream in a cove about five miles to the southward of the ship, the south-east point of which presented an excellent position for the settlement, as it was moderately elevated and tolerably clear of timber. The ships were immediately moved down to this cove, which was named 'King's Cove', after the first discoverer of the straits and islands; the point determined on to form the settlement 'Point Barlow': and the whole anchorage 'Port Cockburn', in honour of Vice-Admiral Sir George Cockburn, one of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty.

"On the 1st of October parties were sent on shore to clear the ground and lay the foundation of a fort; and as it was probable the Malays would visit the place in great numbers, and as much hostility might be expected from the natives, who were, as we could judge from the number of their fires on both sides, very numerous, I was determined to render the fort as strong as the means of the expedition would admit. Thermometer 84 deg. to 88 deg.

"On the 8th, began a pier for the purpose of landing provisions, guns, &c. From this period up to the 20th the various works were carried on with such zeal, that the pier, one bastion, and the sea-face of the fort were completed, and I had the satisfaction, on the 21st of October, of hoisting His Majesty's colours under a royal salute from two nine-pounder guns and one twelve-pounder carronade mounted on 'Fort Dundas', which I named in honour of the noble lord at the head of the Admiralty. The pier is composed of immense heavy logs of timber and large masses of sandstone rock; it is sixty-four feet long, eighteen wide, and thirteen high at the end next low-water mark, and from the solidity of the materials will probably last many years.

"On the 25th of October I had been several miles up a small river in Bathurst Island, and on my return, near the entrance, was surprised by the sudden appearance of ten natives, who had waded—it being low water—across the river nearly to a dry sandbank situated in its centre. They were armed with spears, and at first seemed disposed to dispute the passage with us. On our approach they retired towards the shore, which was thickly covered with mangroves, and throwing down their spears, spread their arms out to show us they intended nothing hostile, accompanying the action with great volubility of tongue. I rowed towards them, but they hastily retreated. However, after some time they gained confidence, and advanced so near as to take a handkerchief and some other trifles from the blade of an oar, which was put towards them. I called the river, consequently, 'Intercourse River', and the point 'Point Interview'.

"The same afternoon two of our men, cutting timber and reeds, were in an instant surrounded by a party of the natives, who seized them, but offered no other violence than wresting their axes from them. They had probably been watching some of our parties in the wood, for they appeared to have a correct idea of the value and use of the axe. As soon as our men were at liberty they ran towards the fort—an alarm was given—the soldiers seized their arms, and the savages would have suffered had they not hastily retreated. I immediately went on shore with Captain Barlow, and after going some distance, came up with the natives, in number eighteen or twenty, with whom we soon established communication by making signs of peace. They threw down their spears and came forward with confidence; they, nevertheless, kept some of the youngest in the rear, whose duty seemed to be to collect the spears ready for action. We offered them handkerchiefs, buttons, and other trifles, which they accepted without hesitation, but after having satisfied their curiosity they threw them away. They made many signs for axes, imitating the action of cutting a tree, and accompanied it with loud vociferations, and almost inconceivable rapidity of gesture. They were given to understand they should have axes if they came to the settlement, and so drew them near the fort, but no inducement could get them into the clear ground or inside the line of cottages. They had, I found, stolen three axes, but as we were anxious to establish friendly relations, no notice was taken of the theft; and three others were given to them, at which they appeared highly pleased, especially the chief, to whom a broader one than the rest was given, and who immediately examined the edge, and with much delight showed his fellows that it was sharper than theirs. They retired, and made their fire about half a mile from us.

"On the 27th the same party re-appeared, accompanied by a youth evidently of Malay origin, but even lighter in colour than those people generally are. In his manners he was exactly like the rest, and most probably had been taken by them when very young. They seemed very anxious that we should notice him, thrusting him forward several times when near us. I found they had surprised two of our men, and taken from them an axe and a reaping hook. These articles were of some value to us; our stock was limited, and it became necessary to check the disposition for theft. Therefore, on their making the usual signs for axes, they were given to understand that we were displeased and that none would be given.

"The young Malay, having the reaping-hook in his hand, it was pointed to, and after some hesitation was given up; but the axe was gone. I retired towards the fort. Finding they could, not get the only object that they seemed to value, and our sentinels being on the alert with fixed bayonets, of which they were much afraid—they retired; but it was evident from their brandished weapons they were dissatisfied and probably meant mischief. We saw nothing of them until the 30th, when our boat at the watering-place was surrounded by some twenty who sprang from the bushes, but hesitated to attack on seeing the arms the crew had. At the same moment another party equally numerous suddenly appeared at a cottage in a garden which had been made by the officers at a small distance from the water. It appeared that only one of the young gentlemen and a corporal of marines were in the house. They attempted to retreat, but were opposed by the natives. The affair began to look serious, and they preparing to throw their spears the corporal fired over their heads—(I had given positive orders that except in cases of absolute necessity they should not be fired upon)—upon which they drew back and offered an opportunity for retreat. The corporal loaded as he ran, firing repeatedly until the young gentleman reached the boat, when a shower of spears were thrown from both parties of the natives, some of which went into the boat, and one grazed the midshipman's back. For the sake of sparing bloodshed which would have followed another discharge of spears, the corporal then selected the chief for punishment, and fired directly at him; he Immediately fell or threw himself on the ground—which several others Instantly did on seeing the flash—but it was most probable that he was struck, for he did not rise so quickly as the rest, and the whole party ran Into the wood. None have since been seen in the neighbourhood.

"These people were above the middle height, their limbs straight and well-formed, possessing wonderful elasticity; not strongly made, the stoutest had but little muscle, their activity was astonishing, their colour nearly black, their hair coarse but not woolly, tied occasionally in a knot behind, and some had daubed their heads and bodies with red or yellow pigment. They were almost all marked with a kind of tattoo, generally in three lines, the centre one going directly down the body from the neck to the navel, the others drawn from the outside of the breast and approaching the perpendicular line at the bottom. The skin appeared to have been cut in order to admit some substance Into it, and then bound down until It healed, leaving small raised marks on the surface. The men were entirely naked, but we saw at Bathurst Island two women at a little distance who had small mats of plaited grass or rushes round the body. Their arms were the spear and waddy. The former is a slight shaft well hardened by fire, about nine or ten feet long; those we saw generally had a smooth sharp point, but they have others which are barbed—deadly weapons. One of them was thrown at us, and I have preserved it; it is very ingeniously made, the barbs being cut out of the solid wood; they are seventeen in number, the edges and points exceedingly sharp; they are on one side of the spear only. As they had no iron implements or tools it is wonderful that they can contrive to produce such a weapon. We saw but few of these barbed spears, and it is probable that they cost so much labour in making that they are preserved for close combat or extraordinary occasions. They did not use the wommerah or throwing-stick, so general in New South Wales. The waddy or short pointed stick was smaller than those seen in the neighbourhood of Sydney, and was evidently used in close fight as well as for bringing down birds or animals for food. They throw this stick with such wonderful precision that they never fail to strike a bird on the top of the highest tree with as much certainty as we could with our best fowling pieces. In their habits these people much resemble the natives of New South Wales, but they are superior in person, and if the covering of the women is general it is a mark of decency and a step towards civilisation perfectly unknown to the inhabitants of the east coast. The hallowing and decoration of a sepulture is such an acknowledgment of a supreme power and a future state that it appears evident that the notions of this people on this subject are by no means so rude and barbarous as those we have been accustomed to find amongst the New Hollanders generally.

"On Bathurst Island we found the tomb of a native; the situation was one of such perfect retirement and repose that it displayed considerable feeling in the survivors who placed it there; and the simple order which pervaded the spot would not have disgraced a civilised people. It was an oblong square open at the foot, the remaining end and sides being railed round with trees seven or eight feet high, some of which were carved with a stone or shell, and further ornamented by rings of wood also carved. On the tops of these posts were placed the waddies of the deceased; the grave was raised above the level of the earth, but the raised part was not more than three feet long. At the head was placed a piece of a canoe and a spear, and round the grave were several little baskets made of the fan palm leaf, which from their small size we thought had been placed there by the children of the departed. Nothing could exceed the neatness of the whole; the sand and the earth were cleared away from its sides, and not a scrub or weed was suffered to grow within the area.

"The pier having been finished on the 21st, the party employed on that service and the whole strength of the expedition was directed to the fort, and completing the different works.

"On the 2nd of November commenced building a magazine. On the 7th the Commissariat store-house was finished; and by the 8th the whole of the provisions, stores, and necessaries were landed from the 'Harcourt', and properly secured therein. This store-house is built of wood, well thatched, and fully equal to the occasion until a more regular and substantial one can be built. It contains nearly eighteen months' provisions. The fort, which commands the whole anchorage—the shot from it reaching across to Bathurst Island—was completed (with the exception of the ditch) on the 9th of November. It is composed of timbers of great weight and solidity in layers live feet in thickness at the base; the height of the work inside is six feet, surrounded by a ditch ten feet deep and fifteen feet wide; on it are mounted two nine-pounder boat guns to shift on occasion, and to be put on board the 'Lady Nelson' when it is necessary to detach her to the neighbouring islands or for other purposes. Those guns are provided with fifty rounds of round and grape, and are part of the upper-deck guns of this ship. The fort is rectangular, its sides being seventy-five yards by fifty: in this square are the houses for the commandant and the officers of the garrison, and a barrack for the soldiers is to be put into immediate progress. The soldiers and convicts have built themselves good and comfortable cottages near the fort.

"The climate of these islands is one of the best that can be found between the tropics: the thermometer rarely reaching 88 deg., and in the morning at dawn sometimes falling to 76 deg. Nothing can be more delightful than this part of the twenty-four hours. I was obliged, by necessity, with the whole of the ship's company, to be constantly exposed to a vertical sun, but fortunately few have suffered, and none very severely.

"The soil of this island appears to be excellent. In digging a deep well for the use of the settlement we found a vegetable mould about two feet deep; then soft sandstone rock, occasionally mixed with strata of red clay, until the depth of thirty feet, when we came to a vein of yellow clay and gravel through which an abundance of water instantly sprang, and rose to the height of six feet.

"It is probable that this soil is capable of producing most—if not all—the tropical fruits and shrubs of the Eastern Islands. The plants brought from Sydney flourish luxuriantly, particularly the orange, lemon, lime, banana, and sugar-cane. Melons and pumpkins spring up immediately, and the maize was above ground on the fourth day after it was sown.

"We found the stream of water first discovered to run into several ponds near the beach—which affords to ships an easy mode of watering—and, no doubt, valuable rice plantations may be formed in their neighbourhood.

"Amongst the trees, some of which are of noble growth, I found a sort of lignum vitae, which, probably, will be valuable for block-sheaves; and several others, which appear to be calculated for naval purposes. The forests are almost inexhaustible. A sort of cotton tree was also found in considerable numbers, but not being certain of its produce being valuable, I have sent a sample to England for inspection. We likewise found the bastard nutmeg, and a species of pepper highly pungent and aromatic. The trepang has not been found here. The fish taken in the seine are mullet, a sort of bass, and what is most abundant is that which seamen call the 'Old-Wife'. Our supply of fish is very precarious, being sometimes a week without taking sufficient for everybody. At Port Essington, on the contrary, we always filled the seine at a haul.

"The animals we have seen on this island are the kangaroo, the opossum, the native dog, the bandicoot, the kangaroo rat, and the flying squirrel. The birds are pheasants, quail, pigeons, parrots, curlews, a sort of snipe, and a species of moor-fowl. The venomous reptiles are few: some snakes have been found, which, from the flattened head and fang, were evidently poisonous; centipedes, scorpions, and tarantulas are by no means numerous. The mosquito, as is usual in all new and tropical countries, is exceedingly active and troublesome; and a sandfly not larger than a grain of sand is so extraordinarily venomous that scarcely anyone in the ship or expedition has escaped without bites from these insects, which have in many instances produced tedious and painful ulcers.

"Port Cockburn Is one of the finest harbours I ever saw, and is capable of containing almost an unlimited number of shipping of any draught of water, and is completely secured from every wind that blows.

"On the 10th of November, the defences of Fort Dundas being quite equal to an attack from much more formidable enemies than the natives of Melville Island, I determined to proceed in the further execution of the orders I had received from the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty. I gave charge of the settlement to Captain Maurice Barlow, and placed Lieutenant Williamson and his detachment, of Royal Marines under the command of that officer.

"Weighed and dropped into the fair-way, and was saluted by fifteen guns from the garrison, which was returned from this ship.

"On the 11th and 12th employed getting ready for sea, and finally sailed from Port Cockburn on the 13th, the ship 'Countess of Harcourt' in company: the latter for Mauritius and England: H.M.S. 'Tamar' for India."

I may here gratify myself at least by bearing witness, through documents of authority, to the value of an old friend in the public service, whose merits—at so great a distance from the seat of authority—were so tardily and scantily acknowledged; and when acknowledged, were so shabbily waived. Smith, of London, had better friends there than George Miller, of New South Wales.

Extract from "General Orders."

"Head Quarters, Sydney, Tuesday, 17th August, 1824.

"The following appointment in the Commissariat Department will take place from this date:—

"Mr. George Miller, Commissariat Clerk (Treasury Appointment), is to take charge of the Government duties of the settlement about to be formed at the north-west coast of New Holland.

"R. Snodgrass, Major of Brigade."

"Commissariat Office, Sydney, New South Wales,"30th November, 1825.

"Independently of the above considerations I beg to recall their Lordships' attention to my letter of the 28th March last, No. 301, in which, without being apprised of their intentions, I had taken the opportunity to recommend that that gentleman (George Miller) should be promoted to the rank which their lordships rightly deem befitting the office to which such a station is entrusted. The sentiments of approbation which I expressed upon the occasion have been strengthened by every account that has been received since; and, if opportunity offered, would, I feel assured, be confirmed by the testimony of Captain Barlow, the Commandant. I respectfully request permission, therefore, to renew my former solicitations in Mr. Miller's favour, and to add that my confidence in his integrity still remains unshaken.

"W. Wemyss, Deputy Commissary-General.

"George Harrison, Esq.,"Treasury Chambers, London."

"Sydney, 13th October, 1828.

"The Lieutenant-General is pleased to direct that Mr. George Miller, Treasury Clerk, shall proceed by the first opportunity to relieve Mr. Smith * in the charge of the Commissariat at Port Macquarie.

"By command,

"C. Sturt, Acting Major of Brigade."

[* Afterwards Sir John Smith, Commissary-General-in-Chief, in London.]

"Treasury Chambers, London,"13th April, 1829.

"Sir,—The Lords Commissioners of His Majesty's Treasury having had under consideration your letter, transmitting a memorial from Mr. Commissariat Clerk Miller, praying for promotion, I am commanded to acquaint you that their lordships will bear in mind the testimonials which they have received of Mr. Miller's services and good conduct, but that in the present state of this department they cannot comply with his request.

"(Signed) C.J. Stewart.

| "Deputy Commissary-General Laidley, "New South Wales." |

In order to keep the doings on the north coast in sight, I must make a hop from 1824 to 1838. Captain Sir Gordon Bremer, in command of H.M.S. "Alligator", accompanied by Lieutenant Owen Stanley, in H.M.S. "Britomart", the latter having arrived in Port Jackson on the 15th July, 1838, had received instructions to make another effort to make a permanent military depôt at Port Essington. The gratifying intelligence was hopefully discussed again in Sydney; commercial prospects brightened.

The names attached to the address presented to the commander of the "Alligator", on the 22nd of August, may recall many a familiar face and pleasant acquaintance. Two only, perhaps, are yet amongst us. It was presented to Sir Gordon Bremer, on the quarterdeck of H.M.S. "Alligator".

"To Sir J.J. Gordon Bremer, Captain R.N., K.C.B., C.B., &c.

"We, the undersigned merchants and gentlemen, residing in this colony, take leave to congratulate you on your second visit to our shores, and to offer you our sincere good wishes for the success and prosperity of the new settlement at Port Essington, for the purpose of founding which you have been again selected by His Majesty's Government, and to express our admiration of the zeal and enterprise which have induced you, under many trying circumstances, to undertake this arduous adventure.

"We need hardly assure you of the deep interest we naturally feel in the formation and progress of another dependency in this vast continent; its welfare promoted by the auspices of our parent state, and supported by the industry and capital of Great Britain.

"But we desire to convey to you more especially our hope that the settlement which you are about to re-establish may speedily emulate in prosperity this old appendage of the British Crown, and the conviction that she will also become a very important entrepot for the products of trade with the islands of the Eastern Archipelago.

"That your health, and that of the officers and men under your command may be preserved through the trials always attendant upon the formation of a new settlement, and that you may be eventually rewarded by its complete and permanent success is the sincere wish of

"Your obedient and faithful servants and friends,

| "Richard Jones, M.C. | Robert Campbell, M.C. |

| Alexander McLeay | A.B. Spark |

| H.H. Macarthur, M.C. | John Jamison, M.C. |

| P. de Mestre | Wm. Walker and Co. |

| J. Blaxland, M.C. | W. Lithgow, M.C. |

| Thomas McQuoid | S.A. Donaldson |

| Edward Aspinall | Alexander Berry, M.C. |

| John Campbell | Lamb and Parbury |

| Edwards and Hunter | William C. Botts |

| Samuel Ashmore | G.L.P. Living |

| R. Duke and Co. | R.R. Mackenzie |

| William Gibbes | J.S. Ferriter |

| J. Nicholson, Harbour Master | John Lord and Co. |

| A. Mossman | Geo. Cooper, Col. Customs. |

| Brown and Co. | John Gilchrist |

| A.B. Smith and Co. | Willis, Sandeman and Co. |

| R. Campbell, junr. and Co. | Thomas Smith |

| W.S. Deloitte and Co. | W. Dawes |

| Kenworthy and Lord | Thomas U. Ryder |

| P.W. Flower | Robert How |

| John Tooth | Ramsay and Young |

| Betts Brothers | George Weller |

| Alexander Fotheringham | Cooper and Holt |

| J.T. Manning | Geo. Miller |

| Edye Manning | Hughes and Hosking. |

In honor, it may be presumed, of the occasion, our old friend "Isabella" becomes wedded to the new settlement, and sails thereunto, in duty bound, as the "Essington", ahead of the squad of vessels belonging to the expedition, in September.

The most interesting (being autographical) memorial of the second attempt at consolidating an establishment at Port Essington after the abandonment of its neighbours on the right hand and on the left that I have preserved is that contained in a letter from Sir Gordon Bremer to Governor Sir George Gipps. Port Essington itself was abandoned soon after it had done one good service to the country in sheltering and resuscitating Leichhardt and his band. As soon as New South Wales had obtained the gratification of her desire of years, its object was effaced. The interest which its name once so roused lies dormant: nursing, perhaps, but the occasion to fulfil the promise which Port Essington once held out, the future may yet have that occasion in store.

"Victoria, Port Essington, March 17, 1839,

"My dear Sir George,