a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

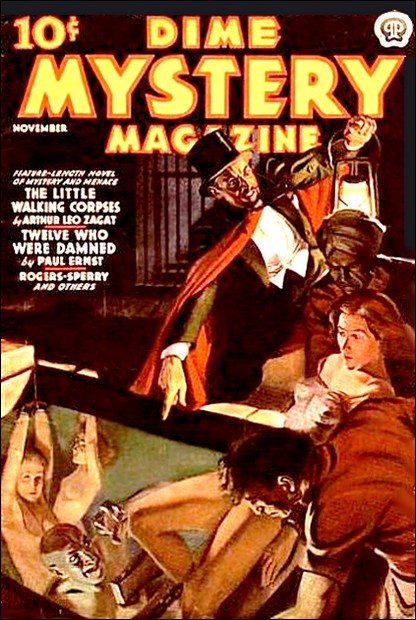

Title: The Little Walking Corpses Author: Arthur Leo Zagat * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1304761h.html Language: English Date first posted: Aug 2013 Most recent update: Apr 2017 This eBook was produced by Paul Moulder and Roy Glashan. Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Guard your little ones with ceaseless vigil, lest the fate of the children of Staneville befall your own! For there, that patter of small, scuffed shoes became a tocsin of terror—and signified that one more babe had joined the Little Walking Corpses!...

Dime Mystery Magazine, November 1937

FEAR was a living presence in the streets of Staneville. It was visible in the pallor that underlay the weather-beaten countenances of the small town's inhabitants, in the furtive glances with which their eyes, bloodshot by sleeplessness, searched every chance-met face with suspicion and challenge.

Worst of all, it was manifest in the flare of their nostrils as eternally they tested for an alien taint a breeze otherwise fragrant with the crisp autumn tang of the forest that coated Buzzard Mountain.

The odor of death was what they sought and found; the stench of a corpse from whose bones the flesh sloughed, moldering.

On Thursday the smell was faint as the smoke-haze from some brush fire the wardens fought where the Range dipped below the northern horizon. Between Monday and Tuesday last, it had been a fetid reek flooding a moonless midnight in which the shrill of the cicadas was stilled, and the countless small noises that make up the country's nocturnal hush were utterly absent.

No one in Staneville had not been waked by that sudden cessation of all sound. None there was who had not lain for interminable minutes stifled as by a noisome, intangible palm folded over nose and mouth while the darkness, pressing against the houses, throbbed with the beat of vast, unseeable wings.

Rousing to a breathless, sultry dawn, none at first knew his nocturnal experience to be other than a peculiarly vivid nightmare. Then the shadow of a charnal stench drifted into opened windows of the houses on the Slope, into the drab shanties of Frog Hollow, and faces turned questioningly to one another.

In dark pupils the knowledge grew that what had passed in the night had not been a dream, but before paling lips could form the words trembling upon them a scream shrilled through the hamlet.

Knife-like where the woods stretch the tentacles of their underbrush toward the last white dwellings of the well-to-do; distance-dulled yet still startling in the lowly slum west of Main Street; it pulled all Staneville into the open, and streams of half-dressed humanity frothed up the steep eastward ascent to Oxford Lane.

Pouring into the Lane they saw the woman on the trim lawn before her cottage, her countenance contorted, her dark hair a tumbled storm on nude shoulders, her arms outflung and imploring.

Sun-blaze striking through a gossamer nightgown stripped her taut body of all concealment, its broad hips and full-formed breasts, its rounded, sturdy thighs; but no one saw her as a naked woman, only as a frantic and terrified mother. For now that they were near, the scream formed into an intelligible shrill call.

"Dickie! Where are you Dickie? Dick!"

"It's Jane Horn," the word passed back to those who could not yet see nor hear. "She's screaming for her little Dickie."

Icy fingers closed on every heart at the mention of misfortune to the freckle-faced, tow-headed ten-year-old, whose cheery whistle and twinkling eyes everyone in the village knew.

Cole Simpson was already at the gate, his gaunt fingers on its latch, having beaten them there because his was the next house to the Horn's. He twisted to the fore-runners and flung at them a barked command.

"Stay back! I'll take care of this."

He went through onto the lawn, his slippers flapping on the dew-wet grass, his tall, spare figure clothed only in trousers and long-sleeved undershirt, his iron-grey hair unkempt. Behind him the first of the crowd stopped short, thrusting back against others who halted in turn. A hush spread swiftly among them and although the woman's cries had died to a sobbing whimper it was distinctly heard by even the farthest removed.

Distinctly heard too was Simpson's voice, strangely gentle, not dry and harsh as was its wont. "What is it, Jane?" The woman's head turned to him but there was no recognition in her eyes.

"Jane!" Simpson snapped sharply, grasping her elbow. "What's the matter?"

"Dick," the name ripped from her. "Gone!" With that she seemed to break up, the tenseness leaving her, her legs folding so that save for the dart of the man's arm about her waist, she would have crumpled to the ground.

"Listen," he said, his narrow, hallow-cheeked face more like grey granite than ever, "listen to me. You must hold yourself together. You must tell us exactly what has happened so that we can help you, so that we can find Dick for you. Tell us what you know."

Somewhere in the crowd a voice whispered, "That smell! It's stronger here..."

"Know?" Jane Horn was saying, looking at Simpson now, seeing him. "All I know is that I went to his room to wake him up and he wasn't there. Not there—nor anywhere."

"Maybe he sneaked out to go swimming before school, or for some other kid's nonsense."

"In his nightshirt? Barefoot? His shoes are there, all his clothes. And he wouldn't do that without telling me. Not my Dickie. Not while his father is away."

"Even your Dick might. He's a boy, after all, and thoughtless. Go into the house, my dear, and get something on. Meanwhile I'll look around. There will be footprints. The ground is soft and I've kept the people from trampling your lawn. Don't worry, we'll find him."

"Footprints! That's it. Look for them. We'll look for footprints under his window." The mother pulled free from Simpson, darted toward the side of the house, her uncovered feet splashing the dew.

There were no footprints in the loam where she bent, peering at the ground. There were no footprints anywhere on the lawn. There was nothing to tell where Dick had gone, or what had happened to him.

By the time this had been ascertained the police arrived: the trio of peace officers that was all Staneville could boast. Balloon-paunched, dull eyes fat-drowned, Chief John Mault wheezingly posted his two lank constables to bar out the buzzing throng by a show of authority less effective than Cole Simpson's simple command, and waddled through the gate to join Cole in his search.

While pendulous jowls concealed Mault's collarless state, no amount of fussy self-importance could hide his fat-brained futility, yet it was he who discovered the only trace of the vanished lad. It was a book, Ken Thomas: Junior G-Man, that he picked up out of the rank weeds where the Horn property ended at the rear of the house and the ground lifted sharply to the forest edge.

He turned it over in his pudgy hands, an abrupt stillness cloaking him. Staring at it over his shoulder, Jane Horn vented a tiny scream.

"It's Dick's!" she exclaimed. "Lou sent it to him from Buffalo. It came last night and Dick took it to bed with him. He fell asleep holding it so tightly I couldn't take it away. Give it to me."

She reached for it. Mault evaded her grasp. "No," he sighed. "No, I've... I've got to keep it." The pink of his plump cheeks had faded to a sickly green.

"What is it?" Simpson demanded, coming up. "Fingerprints?"

"No," the police officer replied, his voice low and toneless as though it were being squeezed out of a clamped larynx. "They'd be washed away by the dew. But... but..." His one hand jerked away from the book. There was a dark brown smear on it, of some viscid, sticky gum. The hand lifted to Simpson's nose.

"Smell," Mault husked.

There was no need to bring that stain so close to the man's nostrils. The stuff that Mault's hand had rubbed from Dickie's book had the unmistakable stench of rotting flesh!

Jane Horn smelled it and her mother's instinct, swifter than any man's thoughts, seized its meaning. "The Thing took him," she shrieked. "The Thing in the night." Then she was a crumpled and pitiful heap in the grass.

They heard that scream, the people buzzing in the road, and blanched, recalling the black quarter-hour they had forgotten, recalling how close the beat of vast, unseen wings had throbbed to the walls behind which their own children were.

That was when the Fear was born in Staneville, the Fear Staneville had not for one moment forgotten because never for one moment of the dreadful days or the sleepless nights since had the air been untainted by the smell of the unknown Thing in the night.

ROSALIE CARTER fought to drive the brooding fear from her classroom, piling on her nineteen charges more work than their little minds and their little hands could cope with. Smiling with her lips, though in her brown eyes there was no smile, she drove them, cruelly kind, while all the time she was poignantly conscious of the empty seat at the back of the room, of the armed men guarding the schoolhouse on Oak Street.

Last Tuesday there had been no school. The mothers had kept their children behind locked doors and barred windows while the fathers, and the young men of the village, had combed every cellar, every yard, and had quartered Buzzard Mountain and the tilled lowland west of Staneville, with no result.

Ostensibly it had been Chief Mault who directed the search, but it was Cole Simpson who had taken a map of the township, penciled numbered squares upon it and assigned each small plot to a group of three. It was Simpson who, drawn, haggard, had checked the last number against a fruitless report just as Wednesday's dawn was greying the sky.

"Nothing," he had said, tonelessly. "No trace of Dick. No trace of whoever took him. No trace, even, of the dead thing we keep smelling."

That had been in this very building. Because Simpson was principal of the Consolidated School it had been used as headquarters for the searchers. Rosalie, brewing coffee through the night for the hunters, had watched the hope drain slowly out of them and the fear grow steadily in their tired eyes. She had heard what Simpson had said at the last, had seen him throw his hands wide in token of despair.

She had come to his support when he had insisted it would be better for the children of Staneville if they resumed their normal routine rather than remain shut in with terror. Despite the alarm of the parents, there was no real evidence that the menace of the Thing was directed against them or, except for the brooding, ominous odor, that it would return at all. At all events the youngsters would be safer carried to and from their homes in convoyed buses, more easily guarded when assembled in a group.

Thus they had argued; but it was not reason, it was the force of Cole Simpson's personality, the respect for him almost amounting to awe that the parents had not lost since they had been tiny tads under his tutelage, that had prevailed.

These recollections ran through Rosalie Carter's mind while a pigtailed miss swayed from one scuffed shoe to another, dumbly twisting the hem of a flowered dress too short for her.

"Come, come, Joan," the teacher's clear, young voice chided. "You ought to know all about how the wasps lay their eggs. This is only Thursday and we heard such a grand report about them on Monday. Who was it brought in that nice composition...?" She gulped, went spinning to the window to hide the appalled dismay in her face! That had been Dick Horn's last recitation to her, his last recitation anywhere!

Her figure was slight against the bright window, graceful, with the lilting rhythm of youth and the out-of-doors. One tanned arm was visible, its firm roundness hardening as its fingers dug into the sill. A straight back shadowed under crisp, white organdie shook with a repressed sob.

"I know, teacher, I remember," an eager pipe brought Rosalie around again. "Let me tell." A spectacled youngster, half out of his seat waved an excited hand.

"All right, Charles." The girl, her winsome small countenance hardly more mature than those of the tots she taught, was for once grateful for the impetuousness of the class pest. "Go ahead."

Joan Hardie dropped into her seat as the lad stumbled into the aisle. "The wasp is the bandit of the insect world," he began in a singsong monotone whose intelligibility was somewhat impaired by the absence of two front teeth. "It stings other insects but it doesn't kill them. It makes them... in... insen..."

"Insensible, Charles," Rosalie supplied. "That means puts them to sleep so that they don't move and seem dead, though they are really alive. The word's insensible."

"Yes'm. Insensible. Then the wasp drags them to its burrow where it lays an egg on them. Then it closes up the burrow so that its enemies can't find it and..."

The boy's mouth was still open but speech was no longer coming from it. His eyes were enormously magnified behind their lenses, bulging and abruptly black. The class was a mass of pallid, staring faces, wavering queerly—and the stench of a rotting cadaver was as thick as an unfelt fluid in the blurring room!

Rosalie's dry throat gave a soundless rasp. A greyness obscured her sight, deepened swiftly into black...

Rosalie was on the floor, awkwardly jammed between iron legs of a desk and a ventilator grating in the wall. The smell had faded almost to its former vagueness. Above her there was the sound of startled movement and the beginning of scared whimperings. She shoved a desperate hand against wood gritty with chalk dust, twisted, somehow managed to regain her feet.

"It's all right, children," she called out. "There's nothing to be frightened of."

She was sick with nausea, her vision scarcely clear yet, within her brain the beat, beat of vast and dreadful wings, but she must reassure them, must ward off from them the panic that was throttling her. "Everything's all right."

The class swam out of the blur, the youngsters straightening from the desks over which they had slumped. Charley Collins was scrambling erect. Nothing was changed, nothing at all.

Get them back into routine! She must get them back.

"Go on, Charles. What happens after the wasp closes up its burrow?"

The boy wasn't looking at her. Then he was, and he was trying to tell her something but his twitching lips made no words. He pointed a grimy forefinger... at a vacant place.

It wasn't the seat Dick Horn used to occupy. It was in the front, near the door. It was where Joan Hardie ought to be, but she wasn't there. She wasn't anywhere in the room.

At Staneville's north-east corner, Oxford Lane curves west and becomes Oak Street. Along the outer edge of this curve is a low wall of lichen-covered stone blocks, and from this a graveyard runs back, gently rising till it ends against a vertical crag outthrust from the forested steep of Buzzard Mountain.

With uncommon foresight the earliest burials were made at the base of this dark and forbidding cliff, and the village of the dead grew outward toward what was in its beginning merely a road climbing to the spring, high in the mountain, whose icy flow was at that time sufficient for the infant hamlet's needs. As a result, the portion of the cemetery bordering the Lane is an expanse of velvet greensward upon which row after row of carefully tended tombstones give a decorative dignity to the graves.

Far back, however, in the shadow of the terminal precipice, neglect has allowed Time and Nature to run their course. Vines, torn by winter storms from the rocky facade, tangle with lush weeds and rank brush to form a gloomy thicket. Here oblong depressions grow slowly deeper as the dank loam settles into hollows once filled by caskets now inextricably mingled with their ancient occupants. Here green-slimed stone slabs, gnawed by decay, lean crazily askew, their inscriptions moss-filled and illegible.

Into this miniature jungle, the Thursday of that dreadful week, Jethro Anther forced his grumbling way. Brambles tore at the dirt-stained, tough fabric of his overalls. He protected his face from the lash of resentful withes with a pair of hedge-clipping shears gripped tightly in one gnarled hand, and dragged a long-handled spade after him with the other.

"Fool idea," Anther mumbled with toothless gums, "Fixin' up a grave nobody's thought of long as I been diggin' 'em here, an' that's more'n thirty year."

Completely bald, his skin leathery, hatched by fine lines and the color of sunbaked clay, there was a more than fancied resemblance between the gravedigger and his clients. Of all Staneville's inhabitants he was the least affected by what was going on. The smell of death was the odor of his livelihood. He was too old for curiosity, too old for fear.

"But mebbe I ought ter be glad Cal Thomas seed his great-gran'ther's name on thet stone, pokin' around in here Tuesday," he continued, "an' give orders ter have it made decent." He gave vent to a cackling laugh. The thicket seemed to absorb the sound, and Anther came through into a clearing, although the shadow of foliage and of the mountain was no less deep.

He halted at the edge of one of the rectangular depressions. Its stone lay on the ground at its head, fallen backward. Moss was freshly scraped away to reveal faint letters; B-REB-N-S-HO—S.

"Barebones Thomas," Anther cackled, "Mebbe thet wuz yer name when they put ye in, but there ain't even bones left o' ye now, let alone flesh ter cover 'em. Well, I better be gettin' started manicurin' yer garden."

He dropped the shears on the ground to one side, leaned the spade against his knee while he spat into his calloused palms, then gripped its handle. The heart-shaped blade went easily into the ground.

Jethro Anther lifted an unexpectedly large first shovelful, grunted. "Huh!" he exclaimed. "If I didn't know better I'd say some 'un's been an' dug this up not more'n a week ago. An'... an'," he sniffed. "Say, thet's funny. This dirt still smells..."

He checked abruptly, his wiry body rigid. There was the sound of movement behind him. A rustle of leaves, a slither. Anther started to turn...

A shriek sliced the stillness of the graveyard, a single gibbering shriek... The silence of death's sleep closed down.

"JOAN has gone out without permission," Rosalie Carter said, surprised at her own calmness. "She knows she should not have done that." She went along the front of the desk rows. She was opening the door, was leaning out.

The long corridor was dim. From behind shut doors came the drone of the other classes. She could hear Mr. Waite's thin voice declaiming with querulous emphasis: "amo, amas, amat"... the muffled laughter of the kindergartners. There was no small, pigtailed figure in the hall. There was no patter of small, scuffed shoes.

Rosalie Carter felt eyes on her back; watching, expectant eyes. If she called out she would alarm the whole school. But she dared not leave her eighteen youngsters alone, dared not send one of them to Mr. Simpson's office upstairs.

She shut the door quietly, turned to meet the eyes that were upon her, eyes in which deepening fear mingled with childish trust.

"I'll have a talk with her when she gets back," she smiled. "A very serious talk. In the meantime get your notebooks and your spellers and copy the list of words on page twenty-seven." She strolled unconcernedly back across the room through an obedient rustle. "Five times... I want you to know them well." She reached the window, stood against it, peering out.

Her hands, in front of her and hidden from the children, gripped the sill tightly and were trembling uncontrollably. In the moment of thought Rosalie had gained for herself she had abruptly realized that time had elapsed between the surge of that odor and her struggle to rise from a floor to which she did not recall falling. She had lost consciousness for a period the length of which there was no way of estimating. The Collins boy too had fallen to the floor. Every child in the room, had known oblivion...

Every child! Joan also. Joan had not left the room. She had been taken from it!

Rosalie's body was hollow within, and the hollow was filled with a quivering jelly of dread.

A footfall thudded through the glass. Jim Tarr was coming past on his patrol, a rifle gripped in strong, capable fingers, his frame big-boned, lithe, the ripple of silky muscles somehow evident beneath the rough tweeds cloaking them. His head turned to her window, as Rosalie knew it would, and a comradely grin illuminated his blunt-jawed, broadly sculptured face.

Her arm lifted in what to any watching from behind would look like her usual wave of greeting. But the fingers of its hand beckoned imperatively, then went to her lips with a signal for discretion.

Jim's grin vanished. He nodded quick understanding, his blue eyes narrowing with concern. He wheeled, broke into a ground-covering lope. Rosalie saw the dark auburn of his hatless head vanish beyond the corner around which was the school's entrance.

Warming with the knowledge that she had secured aid, that it was Jim who was coming to help her, the teacher turned back to her class. For a short space the silence was broken only by the scrape of busy pencils. Then knuckles rapped briefly against the door. Breath hissed almost inaudibly from between the girl's cold lips as she turned the knob and opened it.

"Pardon me, Miss Carter," Jim said, his tone low but pitched just right to reach into the room. "I've just made a bet with one of the boys about how to spell a word and if you've got time we'd like to have you settle the question."

"Glad to, Mr. Tarr," Rosalie smiled, "but we mustn't disturb the class." She slipped through between the edge of the door and its jamb, keeping the portal half-open.

"What's up?" Tarr breathed. "You looked... jittery."

He wasn't alone. Cole Simpson was there beside him, grave, anxious. "Jittery?" Rosalie murmured. "I'm terrified..." and then she was telling them what had occurred, her eyes not on them but watching through the slitted opening the room where there were now two vacant places.

"Joan's gone," she finished. "I'm sure she's gone just like Dickie Horn."

There was a throbbing moment in which the men's faces visibly greyed.

"She must be somewhere in the building," Jim husked. "Every side of it, every window and door is being watched by armed men and even a rat couldn't get out without someone seeing it."

"I'll have every inch of the school gone over at once," the principal put in. "Can you keep on with your class?"

Rosalie's lips were icy but there was no lack of courage in her voice. "Of course."

"Then do so. Don't worry. We'll find Joan. We'll find her if we have to take the structure apart brick by brick."

"No," Rosalie Carter said. "No. You will not find her."

Nor did they, though under Simpson's direction not even a fly's resting place was left unsearched. They had to invade the classrooms at the last, had to let the pupils know what was going on, had to question every one of them, every teacher, and send the children home in buses bristling on the outside with weapons and shuddering inside with white-lipped terror. But they did not find Joan Hardie.

Not then.

Jim Tarr had ridden the doorstep of the school bus that made the outer circuit of the town. It was returning now through the early dusk the shadow of Buzzard Mountain brings to Staneville, and he was seated alongside Walt Smeed, its driver, but his forefinger still hovered near the trigger of the rifle in his lap and his anxious look still probed the dimness gathering in Oxford Lane.

"Lou Horn got back this mornin'," Walt remarked nodding at the pale bulk of the house from which the Thing had taken its first victim. "They say he's near crazy with grief."

"I don't wonder," Tarr responded. "It would be a hell of a sight better for him and for Dickie's mother, to know what's happening to the kid than to be like this, imagining almost anything."

"Yeah," Smeed agreed. "Yeah. You're right. Even if he was a layin' in the graveyard here." He slowed for the bend just ahead.

"STOP!" Jim yelled, clawing the door handle. "Stop!" He was out of the bus, was vaulting the cemetery wall. Walt, slammed on his emergency, snatched a forty-five out of a holster hanging from the wheel, lurched to the ground, scrambled over the fence. Thudding feet gave him his direction. He saw Tarr, a spectral apparition dodging among tombstones in the spectral greyness, plunged after him.

Jim slowed, stopped as Smeed came up to him. "What is it?" the latter gasped.

Tarr peered into the colorless murk that was almost more concealing than darkness. Smeed stiffened, fiercely aware of the cadaveral odor, omnipresent for so long but weirdly appropriate here. There was no comfort in the hardness of the revolver butt grinding into his palm, but a strange sense that what menaced Staneville was immune to bullets, to any human weapon.

"What did you take out after?" he demanded again, speech an effort.

"I don't know," Tarr whispered, as though he could be overheard. "I saw—thought I saw—someone moving in here. Or some thing. It didn't seem to be shaped like anything human, no more than those..." he jerked a hand to the huddled, shapeless bulks about them that might be headstones or—beasts—crouched, motionless, waiting for a chance to spring upon them. "I saw it for just an instant and then—it was gone."

"Hell," Smeed grunted, with no assurance. "It wasn't nothing. Come on back to the bus."

Jim stared at the gloomy mass of the thicket against the cliff. "I wonder... I'd like to poke around in there. I've got a hunch..."

"You go in there, buddy, and you go alone. You're nuts anyways. The boys went through that mess with a fine tooth comb last Tuesday and Wednesday and scratches were all they got for their pains. Are you coming?"

"All right," Tarr yielded, still reluctant. "I'm coming."

They went toward where they thought the Lane was. It took so long to reach the wall that Walt began to think they were twisted around, but they hit it after awhile. They climbed over. Smeed slid in under the big steering wheel switched on headlights ceiling lights, released the brake.

"Hey!" Tarr exclaimed, behind. "There's one of the kids still... No. Good God! Walt! Look..."

Smeed turned. Tarr was halfway down the aisle his hand on a boy's shoulder. The boy was toppling forward in the seat, strangely stiff. The boy's lids were open but there were no eyes between them, only balls dully white. There was a spray of freckles across the small, still face and it was the face of Dickie Horn.

A night shirt had slipped half-off Dick's bony little chest and Jim's fingers, keeping him from falling, lay in the corner between shoulder and neck, their bronze darker by contrast with the sickly grey-whiteness of the skin there.

"Dead," Walt said. The one word, a statement, not a question, was all he could manage. Somehow he couldn't move, couldn't get up, but he knew there was something queer about Tarr, about the way he stood, rigid, about the way he stared at the small boy.

"No," Jim Tarr said. "Not dead. Maybe he'd be better off if he was."

JIM TARR'S mouth was a tight, colorless line but his nostrils were flaring. Walter Smeed got it too, the smell of dead rot in the bus, stronger here than it had been in the graveyard. The odor of fear. He gulped.

"What... what do you mean?"

Jim's head lifted, turned to him, its face a deep-lined, still mask. "I felt a throb, here in the artery. Another, just now. His heart's beating, very slow, but beating. And the skin's cold, icy, but soft. He isn't dead, Walt. But..."

"But what?"

"I don't know." It was a groan. "We've got to get him to a doctor. The hospital. Get going, Walt. For God's sake get going."

The rasping burr of the starter, the roar, the bus's racketing lurch into motion and its rushing thunder as it hurtled down the long descent of Oak Street brought some sense of reality back to Smeed. It was fully dark now, but the night was filled with the yellow oblongs of lighted, blind-drawn windows, with windows tight shut, nailed shut, with houses whose doors were locked and double-locked against terror.

"What you saw," Walt threw back to Jim. "It slipped around us and put the kid in the bus while we were looking for it. If we'd been smart enough we might have caught it."

"We might have caught it," Tarr husked. "But we didn't. If any more children go..."

It was not until the dusk had deepened almost into darkness that anyone thought to switch on the light. Rob Wood, the school janitor, did it then.

Rosalie Carter, pallor lending her a fragile, almost ethereal quality, blinked. Then, from her habitual post at the window, she could see again the room where she had taught for months, unfamiliar now because its occupants were adults and not the youngsters who had trusted her and whom she had failed.

Cole Simpson sat at the big desk up front, her desk, and beside him was seated John Mault; the grey, poised slenderness of the one an almost painful contrast to the other's gross bulk. Standing to Simpson's left were the school's two handymen: stooped, shabby, stockily built Wood, competent and powerful in his suit of blue dungarees, despite the years evident in the grey bristle blurring the square line of his jaw.

The other teachers were squeezed into the children's seats, a half-dozen angular spinstresses and two men. Julius Waite, the Latin instructor was as sere as his subject; wizened, his countenance sallow and wrinkled as a dried apple; Doctor Holzer, teacher of science, white-bearded, ruddy-cheeked; even brooding fear failing to iron out the good-humored wrinkles at the corners of his small, twinkling eyes.

Grim, quivering with leashed wrath, two young men stood at the door, rifles horizontally across their chests, fingers curled on the triggers.

Mr. Simpson sighed, and began to speak. "One of you," he said in his low, harsh voice, "knows where Joan Hardie is. It is impossible, with the school watched as closely as it was, that she had been taken from it. No one but those here and the children were in the building. No one except the children has been permitted to leave it. Therefore she is somewhere within its four walls and one of you knows where."

"That's logic," Mault put in. "Nobody can't argue with that."

"I can." Surprisingly, it was Mr. Waite whose querulous tone interrupted. "I agree that the child was not seen leaving the school. But she is not in it. We have searched every nook and cranny of it."

Simpson's expressionless visage moved slightly to bear upon him. "What do you suggest, then?"

The Latin teacher shrugged. "'Facile est descensus Averni!', 'The descent to Hell is easy', but no easier than to pose objections to a faulty solution of this mystery that confronts us."

"Nevertheless," the principal insisted, "you have something in mind or you would not have spoken. What is it?"

Mr. Waite looks like a scared brown hare, Rosalie thought, twisting a handkerchief in her fingers. He's simply terrified of answering, but Mr. Simpson will make him.

"What is it, Julius Waite?"

Waite's fleshless lip quivered. "As Miss Bunker will bear me out, Joan Hardie is neither outside nor inside of this building. Hence she must have..."

"Vanished into thin air," Dr. Holzer snorted. "Bunk! I've worked with you and Cole a quarter of a century but this is the first time I've discovered any of us is feeble-minded. I..."

"Just a minute, August," Simpson intervened. "Please let me handle this. Julius, we may in the end be forced to accept your views, but we are not yet ready to admit there is anything of the supernatural about what has happened. We will adhere to the probabilities. I want to know where each one of you was at two-twenty today, which was when I came out of my office and met young Tarr responding to Miss Carter's summons. Suppose you tell us first."

"I was in front of my class, teaching the blockheads the conjugation of amo. I..."

"That will do. How about you, Miss Bunker?"

The response of the parrot-faced English instructress was similar, as was that of the rest except for Dr. Holzer. He alone had not been in full view of a score of pupils at the crucial moment.

"I was in my office," he explained, "but the only door to it is into the laboratory and there were a dozen students there dissecting frogs. Its window is right over the lawn Tarr was patrolling and even if I were still agile enough to climb down from the second story and back again I would surely have been seen. However, you may search the room if you wish."

"We've already done that," Mault said grimly. "And found nothing. Well, Simpson, it looks like..."

Sound rattled the window panes, cutting him off; the roar of a racing motor, the blare of a frenzied horn from outside. Rosalie whipped around, peering through the glass, was jostled by others jumping to look out. A huge vehicle lurched past, its row of windows lighted.

"It's one of the school buses," someone exclaimed. "It's shooting into the hospital driveway. Something new must have happened."

The rush was away from Rosalie now, to the door, but it piled up there against the stalwart guards. "Stop!" Mault called, "You're not going out. None of you is going out till we find out who's tied up with this thing."

There was a sudden chatter of outraged protest, stilled by Simpson's calm, "Take your seats, ladies and gentlemen. Please take your seats." Rosalie noticed that she had dropped her handkerchief in the excitement, bent to pick it up.

When she straightened her pupils were dilated, her face taut, her slim frame trembling.

"We are still of the opinion that one of you is concealing something," Cole Simpson was saying, "and until that one confesses you are all under arrest. You will be held here under guard, all night, all week if necessary. There will be armed men posted outside the doors and armed men under the windows and their instructions will be to shoot to kill anyone who tries to leave."

"What about you, Simpson," Julius Waite demanded. "Seems to me you're in this as much as the rest of us. Even more. The first child disappeared from the house next to yours, and..."

"Chief Mault will be in my office with me," came the steady reply. "He cannot be suspected."

"Mr. Simpson," Rosalie found her tongue at last. "I've found out something."

"Hold it. If you've discovered something it would be better that the culprit, if he is in this room as we suspect, should not hear you. Suppose you come to my office, with me and Chief Mault, and tell us about it there."

Rosalie nodded agreement. "Meantime," Simpson continued, turning to the others, "the guards are already posted. Remember their instructions."

Rosalie Carter went down the first floor corridor between the slender old educator and the wheezing, puffing police Chief. There were too many in the hall for her to speak; too many hard-eyed, set-jawed men with guns of all description, watching her curiously. Simpson unlocked a door, clicked a switch button. The familiar furniture seemed to take on a new aspect, seen thus by artificial light. This was the outer office and Simpson led the other two toward the door to his private sanctum. He was moving very slowly, very wearily. He had to hold on to the jamb while he fumbled his key into the lock of that inner door.

"I better 'phone the hospital," Mault wheezed, "and find out about that bus. You two go on in, I'll be right with you."

The door opened. Simpson found the switch, filled the small room with light. The door closed behind Rosalie. She heard the spring lock click. The principal staggered, turned a face toward her that was green-filmed, pallid.

"I—I'm not as strong as I thought." He made a pathetic effort to smile, and suddenly Rosalie was sorry for him. "These three days... I have had no sleep."

He gained his desk, stumbled into the chair. His hands were hidden by the glass-topped walnut. "The school—my dream of the years, one great school instead of the little one room shanties scattered around—slipping away after I had attained it. If this keeps up... already the farmers are refusing to send their youngsters into Staneville, refusing to pay their assessments... the builders threatening to foreclose their mortgage... But what was it you found?"

"This." Rosalie held her handkerchief out to him. "I dropped it, rubbed it against the ventilator grating when I picked it up, and...

The wisp of linen was blotched by a dark brown smear. There was no need to bring it closer to Simpson. The odor of a corpse, the odor of the fear that had been throttling Staneville so long, was very strong in the room—as if a corpse were present.

There was something queer in the old man's eyes. "You think...?" His arm moved, as though his unseen hands were doing something under the desk-top.

"It was on the grating. The hole's large enough for a man to get through, and the network lifts out easily. It's some gas that makes you unconscious. That's the way Joan was taken!"

That smell! It was strangely more powerful! It was choking her, was stoppering speech. Rosalie swayed, clutched for support.

Through a darkening swirl she could make out Cole Simpson's face, contorted, his eyes growing till the face was all eyes, hating eyes... Simpson!

She was going down, down, down into bottomless dark. Hands caught her, lifted her...

The bus roared into the hospital courtyard, racked to a halt. Men in white sprang out of a doorway over which a brilliant lamp globe was lettered, ADMITTING ROOM—started running across the asphalt toward the bus.

"Take care of it, Walt," Jim Tarr snapped. "I'm off." He was in the vehicle door, was dropping to the ground.

"Hey!" Smeed blurted. "Where are you going?"

"Back to the graveyard," Jim snapped. "Back to find out what's hiding in the jumble beneath the cliff." Then he was gone, dodging the approaching orderlies; gone into the darkness that lay on Staneville like a funereal shroud.

ROSALIE CARTER came up out of a sick nothingness to dazed awareness of motion, to dull realization that she was cradled in arms that felt her weight not at all, that she was being carried to some unknown place. There was the beat of vast, unseen wings about her, the flow past her cheek of air dank and damply chill. There was that smell in her nostrils, the stench of corrupt flesh waking memory, waking fear to claw her...

Over and over she kept sinking into oblivion, over and over, but each time the fear was greater, the dread grown, till almost the girl was praying, inchoately, that there should be no next time.

Sometimes there would be the horror of that moment of discovery that Cole Simpson, venerated and venerable, was the perpetrator of that which had come to Staneville. Sometimes there would be only the terror of what lay ahead, at the end of this strange, dark journey. But always there would be that throb, throb, throb and always the reek of a charnel house.

Time blurred and had no meaning. It might be minutes or hours since the beginning of this too real nightmare. Rosalie did not know and did not care.

At length, however, she came to a space of awakening and though the beat of something enormous but unseen met her, and the sepulchral stench, she was no longer moving, no longer held in muscular arms. There was hardness under her, a painful hardness, and there was a rustling sound about her.

She forced her lids apart.

A glow, greenish, unearthly, lay against Rosalie's aching eyes. Inconsequentially, she recalled a rotted stump once seen in the lightless woods, a luminous ghost shape. This glow was exactly like that shining inner phosphorescence of decay.

It seeped down out of a ceiling above her, so low that it seemed to press ponderously upon her, so irregular in surface that it seemed to have no shape, that it seemed momentarily about to cave in and crush her. Dark, slender threads crawled over it, immobile at the instant but surely about to wake to loathsome life.

The rustling sound rolled Rosalie's head to it, to a swirl of blackness moving toward her, apparently out of a wall eerily glowing and formless as the roof!

The Thing was man shape, yet in some curious manner not human. It was faceless in rustling, stygian draperies and the limbs growing out of it were like great black wings, but the sound they made, reaching for her, was a flutter and not the throb, throb that still beat against her ears.

Terror, imminent and awful, struck icily to the very core of the girl's being, stripping her of will, of strength, so that she was held in a nightmare paralysis. The motion of the Thing took it out of the line of her sight and she saw past it.

An abortive scream rasped the tight cords of her throat.

A black hole gaped in the wall, entrance to some tunnel. Before it, stark nude and incredibly rigid on a green-slimed pallet that had the very size and shape of a gravestone, Joan Hardie lay. One pigtail coiled in a lax position across the pitiful, small neck and tiny white fingers were outspread as if to fend off horror.

"No," the Thing had a voice, muffled, hollow. "She is not dead, my dear." And a chuckle came, slow, hateful. "Not dead, but she will remain like that for years. Forever, if I wish it so."

Yes, the apparition had a voice. Though changed by the fabric through which it came there was still something familiar in its timbre. Of course! Rosalie remembered. This was Cole Simpson. It was Cole Simpson who had tricked her into being alone with him, had gassed her to insensibility and carried her off.

"Look at her. You will be like that in a moment—and forever." He was right above her now, was bending to her, those grotesque arms of his descending to her, like wings of black horror closing down. "You know too much—but you will be silent about what you know, forever." He was going to kill her, this man whom all Staneville revered, this man she, herself, had so venerated. "Not dead, but silent, unless I choose to wake you." A hand, cold, clammy, closed on her bare arm.

"Wait!" Astounding that Rosalie could speak even with this harsh croak. "Wait." Somehow she must deter him, must stave him off. Perhaps Mault had battered down that locked door, found them gone, found the way they had gone. "What are you going to do to me?" There must be rescue for her. There must be! "What do you mean, not dead but silent forever?"

Again that slow chuckle, but the black form was stayed. "Insensible, my dear." Where had she heard that word before? "Unable to move, to speak, to see. Needing no food nor drink. Not dying even though centuries pass, because there is no waste of tissue, the functions being suspended. It can be done. I am the first man to have accomplished it, though aeons ago the way was discovered by the wasps."

The wasps! That was it! Strange that it should have been Dickie Horn who had told how the wasps stung their victims, dragged them to their burrows and left them alive for ten times their span of normal life, in order that the hatched grubs might have fresh food. Strange that thus he should have predicted his own fate.

Recollection struck at Rosalie of a digger-wasp burrow she had unearthed one spring, of the living-dead cicada bodies within and how they were acrawl with the little white grubs; eating, eating. That was what was in store for her! Here, in this dark cavern, the blind pallid crawlers of under-earth would find in her inanimate body fresh food for their hunger and...

The claw on her arm tightened, and in the other, thrust abruptly out of the black drapery, was the bright gleam of a glass tube, the sharp gleam of a long, keen needle...

"This will do it," her captor husked. "The venom of a thousand wasps in this hypodermic syringe. It will..."

From the tunnel's Nubian maw there was the faint thud of distant feet. Of approaching rescue. He had not noticed it, she must keep him from noticing it. "I know why you are doing it to me, but why did you do it to the children? You have always loved them, why are you making them suffer?"

"So that others, millions of others, should not suffer." It worked! The slow thrust of that terrible needle was halted. "The world stirs to war, and with the next war will come clouds of lethal gas descending on the cities, enveloping them for years, perhaps. No way to escape it, no way to bar it out and still have air to breathe, food to eat, water to drink. But I will show them the way. A dose of the living death in this vial, then they can be closed up in chambers hermetically sealed against the gas. When it is gone the chambers will be opened and they will be taken from them and brought back to life, the children and the women who but for me would be long dead. A million against a few, but I had to devise a method to obtain the few I needed for experiment, a way to hide them..."

The oncoming feet were nearer, but still far. Too far. "Then there is a way," Rosalie said, "to bring your victims back to life."

"My subjects," he corrected. "There must be. There has to be." Was that a sigh that came out of the faceless mask? "But my knowledge was not sufficient to find it." Then a chuckle. "That is why I gave them back my first subject so that those who do have the knowledge might work on him, might find that way for me. Clever, wasn't it?"

"Clever," she praised, fighting for the little time she needed now. "As clever as the way you sent the gas through the ventilators into my classroom, making me and the children unconscious while you stole Joan from among us. Clever as the gas itself, from which people wake without knowing they have been asleep. What is that gas?"

"My own invention. An organic compound, distilled from the half-putrefied bodies of animals. I..."

He checked, whirled to the pound of feet in the tunnel mouth. Out of it lurched a bulky form. In the grisly light Rosalie glimpsed a curious contraption clamped over the man's nose and mouth, but she knew he was Rob Wood, the janitor.

"Rob!" she yelled. "Thank God you've come." She flailed hands against the gravestone beneath her, pushing herself up to aid him in the coming struggle.

"Hurry it, Chief," Wood panted. "They're comin' awake in the schoolhouse. We got ter get back quick afore they find out we're missin'... Look out! She's gettin' away!"

He jumped on Rosalie, half-risen. His spatulate fingers caught her frock at the throat, it tore away with a ripping sound. The dank air of the subterranean hollow was chill against her bared breasts, and against them his calloused palms thrust cruelly, shoving her down upon the stone, holding her down, helpless, immovable.

Above her the other's black shapelessness swooped down, and the terrible needle darted for her. A scream broke from Rosalie Carter's throat, shrill, agonized.

FROM the schoolhouse on Oak Street the reek of a hundred moldering corpses was gradually fading. Among the still bodies slumped in the hallways, in the seats of the two classrooms that had been guarded as prison cells, one stirred a little, then another.

The thicket where the graveyard lay against its terminal cliff battled Jim Tarr as though it were endowed with a malevolent life. His flashlight beam bored a tight hole in the tar-barrel murk, but from the darkness on either side the bushes lashed him, thorns tore at him. He panted, struggling through it, struggling on.

What was it he thought he was going to find here?

His face, his hands, were torn and bleeding. The weariness of sleepless nights, of brooding fear, weighted his limbs so that they were numbed, leaden. Every deeper shadow, every half-seen shape blacker against the black threatened him with a menace the more dreadful because its nature was unknown. But he bored deeper into the tangle, a convulsive grip flattening his fingers on flashlight cylinder and rifle butt, his blunt jaw grimly outthrust, his eyes narrowed and smouldering.

Behind those eyes was the vision of a small form rigid in a death that was not death. Behind those eyes was the recollection of a grey shape drifting in greyness out of this thicket, drifting, he could almost swear, into it again. And in Jim's nostrils was the stench of death's putrescence, deepening as though he neared its source.

A slanting tombstone jutted out of the greenery in front of him. He veered to pass it. Something clutched his ankle—a vine loop—tripped him. He sprawled forward, throwing the rifle over his head, thumped hard, breath gusting from between his lips. The flashlight jolted from his hand, rolled beyond grasp.

Its beam scythed the blackness, fell across a ghastly visage peering through a flutter of leaves. A toothless skull half obliterated by a dark stain. Not a skull, a mummy-head, parchment skin shrunken into the hollows, and the stain dried and clotted blood.

Tarr's fists pounded the earth. He was fighting to rise, to flee. Ancestral panic prickled the hairs at the back of his neck, surged darkly in his veins. Black lips in that mummy face twitched. Sound mumbled from them.

That jerked Jim forward, to the hitherto unseen body lying crumpled in the depression of a sunken grave. "Another," he gasped. "Good God! It's Jethro Anther. What happened, man? What is it?"

"Socked me," the blackening gums mumbled. "Bruk me skull." It was only the merest shadow of a voice, as though by some hideous necromancy of hate it projected from beyond death a message of vengeance. "Rob Wood. Thought I was dead, but I saw..." The voice died, but there was a scrabble in the dark beside his contorted form, a movement of his twisted shoulder that told Tarr it was his hand that scrabbled, and an imperative jerk downward of the fleshless chin.

Jim snatched for his hand-torch, within reach, darted its light to where that scrabble came from. He saw...

Dark dirt upturned out of the ancient grave. Jutting from it a metal cylinder topped by a metal wheel, a gas tank beyond doubt!

Anther's fingers, like horny bird's claws, made a turning movement. Understanding the speechless command, Tarr reached to the valve wheel, twisted a bit. The gas hissed out, and the reek of rotted cadavers was rank in Jim Tarr's nostrils!

"What the...!" he exclaimed, twisting the valve closed. "It came from here. Leaking..."

A scream cut him off, a woman's scream, oddly muffled but still high and shrill and agonized.

Jim jumped to his feet, rifle in one hand, flashlight in the other. His frantic beam swept the thicket, impinged on the frowning rock-face. Nothing. Nothing but darkness. Nothing but netted, baffling bushes and the black, solid crag.

IN a hospital room light beat down, white and merciless on a bed where a small, still figure lay; beat mercilessly down on storm-dark hair framing the anguish ravaged face of a mother who had lived through agony only to find greater agony.

"Give him back to me," Jane Horn cried. "Give my Dickie back to me."

There was speculation, doubt, in the eyes of the man in white who tugged at a clipped Vandyke. "We might try an injection of adrenaline in the heart tissue," he mused. "It might bring him out of it. Or..."

"Or what?"

"Or it might kill him."

"Even that would be better than this. Try it doctor. Try it."

"God!" Jim Tarr groaned, staring helplessly at the defiant blackness, the scream still ringing in his ears. "Where...?"

"There." The croak came from his feet. Jethro Anther was miraculously half-raised from the ground, miraculously his quivering arm was extending. "Through there." He was pointing at the precipice. "It opens." The hand dropped, never to point again.

Jim flung himself at the crag. His fingers caught a knob. The face itself on the rock was moving, was grating inward. There was a gaping hole at his feet, visible by a strange, eerie luminescence.

Tarr jumped down into that hole, reckless of what might meet him, whirled to a sharp exclamation. He saw tawny hair, a hand clamped over Rosalie Carter's face. He saw a black, stooped shape, fingers spreading the skin over Rosalie's jugular vein, a hypodermic needle sliding sickingly into the white skin. And in the same instant, he leaped.

His flailing gun-butt crunched black-swathed skull-bone, flung the robe-wearer sprawling against the farther wall. His rifle's steel-clad heel jolted Rob Wood's chin, split it, so that as the grizzled janitor fell, scarlet blood gushing from the crushed jaw. And then Jim was kneeling to Rosalie, was gathering her in his arms. As quickly as that it was all over.

"Jim," the girl sobbed, "Oh Jim!" Suddenly she was thrusting at him, thrusting him away, from her.

She was laughing. Most awfully she was laughing the thin, high laugh of hysteria while the tears rolled down her cheeks. She was pointing past him.

"Not Simpson," she jabbered. "Look, Jim, it's not Simpson."

Tarr turned. Somehow in his fall the robes had been torn away from the head of the man in black. Through the torn fabric jutted the white-bearded, ruddy-cheeked countenance of August Holzer!

Rosalie Carter's laugh cut off. She slumped against Jim, a dead weight in his enfolding arms.

The walls were painted a cool green, and every corner was rounded, so that Rosalie knew it must be a hospital room. It was sunlight that had awakened her, and the sound of a shade rattling up to let the sunlight in.

The nurse turned to her. "I see you are awake, my dear, and feeling better. These just came and I brought them in."

"These" were flowers—a great, gorgeous bouquet glorifying the agate pitcher serving them as a vase.

"Oh, lovely," Rosalie exclaimed.

"Aren't they?" the nurse smiled. "And the gentleman who brought them is waiting outside to see you. A Mr. Tarr."

After awhile Jim Tarr was in the room, perched on the edge of a chair, his blue eyes glowing. "I've got good news for you, Miss Carter," he was saying. "Dickie Horn is all right again, and Joan Hardie will soon be."

"Oh wonderful! But what of Dr. Holzer?"

"Dead. Wood's going to live, till he burns in the chair."

"Jim, I don't understand why Holzer went after the children. He told me his idea, but I don't know. I can't decide whether it was madness or genius that impelled him to his acts." She repeated what she had learned in the lair of fear. "I can't quite judge whether he was right when he said it was just that a few suffer to save millions from suffering, but it seems to me adults would have been better subjects for his experiment than children."

"Maybe. But there was something else behind what he did than a way to save people from being killed by gas. You see, there was a scheme on foot for breaking up the school district before the building of the Consolidated School was decided on. If that had been done Simpson would have been put in charge of one of the districts and Holzer of the other, but the Consolidation stopped it. By terrifying the farmers into withdrawing from the merger he hoped to regain that position and no longer remain Simpson's underling. That's the way it's been figured out, anyway, by Julius Waite and Simpson, but we'll never know."

"No," Rosalie sighed, "we'll never know whether he was a philanthropist or a madman, a genius or a greedy, avaricious monster."

"There's no doubt about Rob Wood. Holzer had caught him accepting bribes, falsifying his records and so on. He held that knowledge over Wood's head and made him help him, promising him a fortune if his schemes were successful. It was Holzer who sprayed the gas through the Horns' window, and later filled the school's ventilating system with it from the duct in his private office. But it was Wood who actually carried the kids off. They had the cylinders buried in a grave, and Wood also went back and forth through the tunnel. That's why he killed Anther, who was digging into that very grave."

"The tunnel?"

"Oh, I forgot that you didn't know. It's the old water tunnel that used to run down from the spring on Buzzard Mountain before the new pumping system was installed. They used it to get from the school to their hidden roost in the cliff. The new aqueduct joins the old just past the hospital here, and the sound came through."

"Jim!"

"Yes?"

"Jim, I haven't thanked you yet for saving me, for taking care of me."

"Hell, you don't have to thank me for that. Matter of fact, I'd like..." The chap broke off, red suffusing his big-boned face.

"You'd like?" Rosalie prompted softly. "What is it you would like, Jim?"

Jim Tarr smiled. "Well... Might as well say it... I'd like... to take care of you... for... for..."

"For always, Jim?" Rosalie murmured. "Perhaps I would like that too. Why don't you ask me?"

Minutes later the nurse opened the door, her knocking having met with no response. She closed it again, very softly.

"Doctor or no doctor," she whispered to herself, "that's better medicine for that girl than all the drugs in the storeroom."

This site is full of FREE ebooks - Project Gutenberg Australia