|

Project Gutenberg

Australia

a

treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden

with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with

Google Site Search |

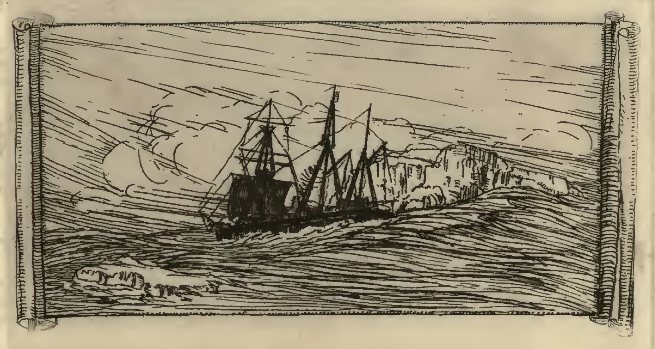

Title: The Antarctic Book: Winter Quarters, 1907-1909.

Author: E.H. Shackleton (Editor).

* A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook *

eBook No.: 1304521h.html

Language: English

Date first posted: July 2013

Date most recently July 2013

Produced by: Ned Overton.

Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions

which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice

is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular

paper edition.

Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the

copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this

file.

This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg

Australia HOME PAGE

Production Notes:

A few typographical errors have been corrected. The

illustrations are placed where the occur in the original.

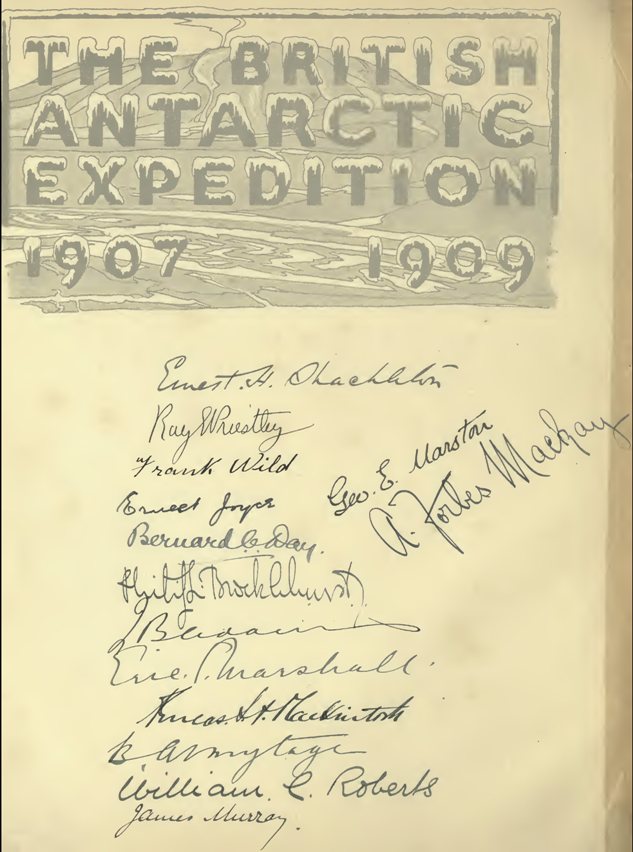

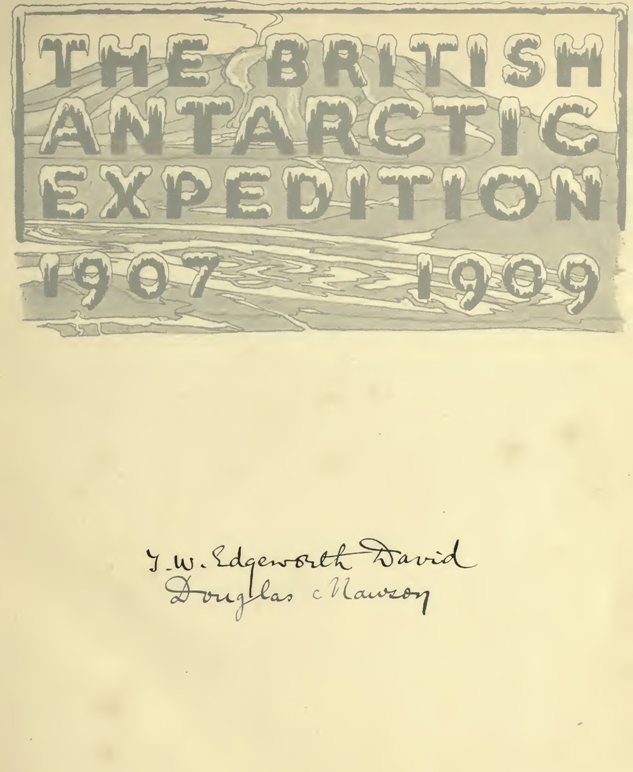

THE ANTARCTIC BOOK

WINTER QUARTERS

1907-1909

Of this book only 300 copies have

been printed for sale. The type

is distributed, and it will not be

reprinted

THE ANTARCTIC BOOK

WINTER QUARTERS

1907—1909

LONDON

WILLIAM HEINEMANN

MCMIX

CONTENTS

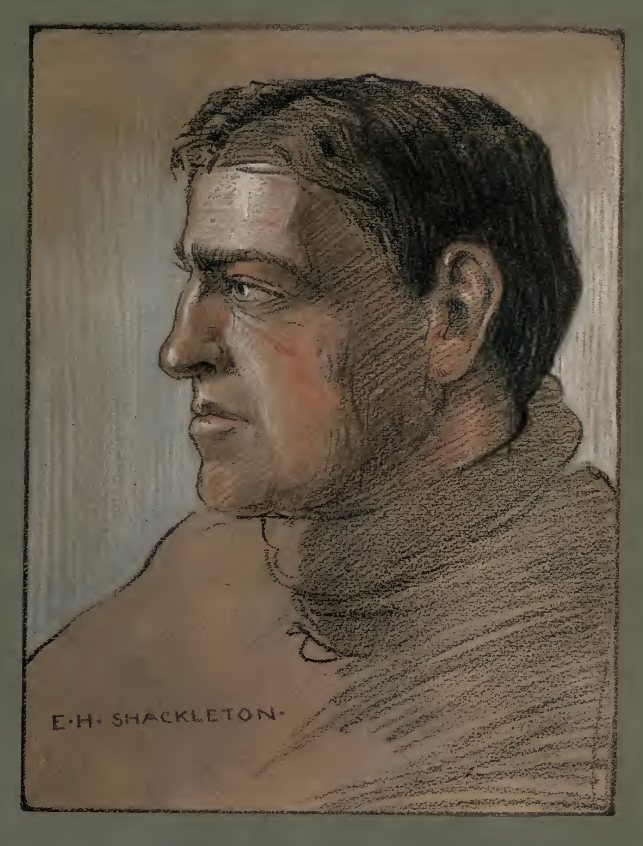

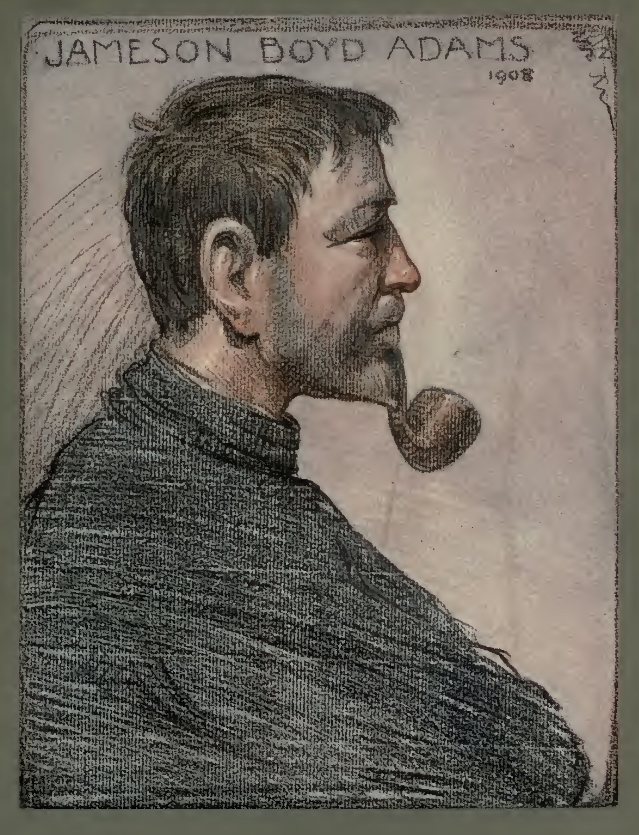

THE SOUTHERN PARTY

I

E. H. SHACKLETON

II

JAMESON BOYD ADAMS

III

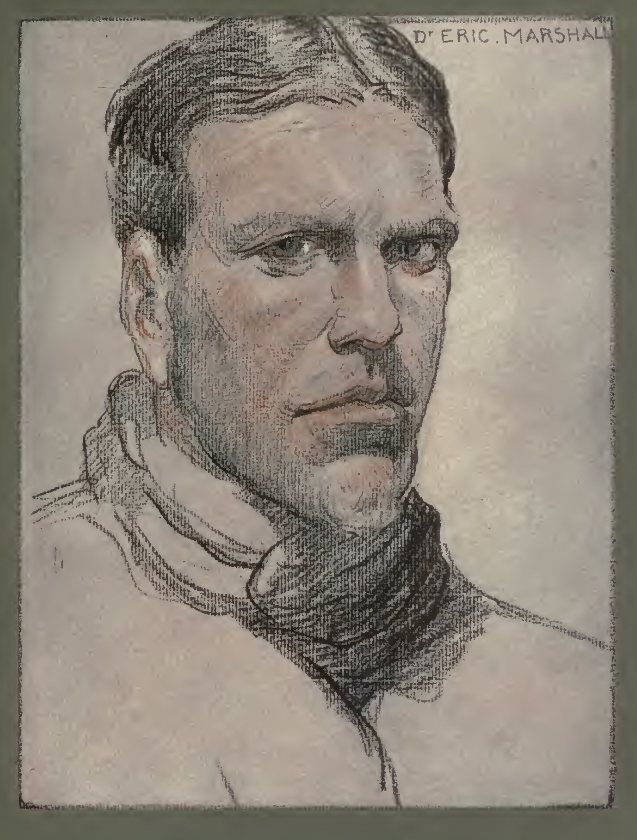

DR. ERIC MARSHALL

IV

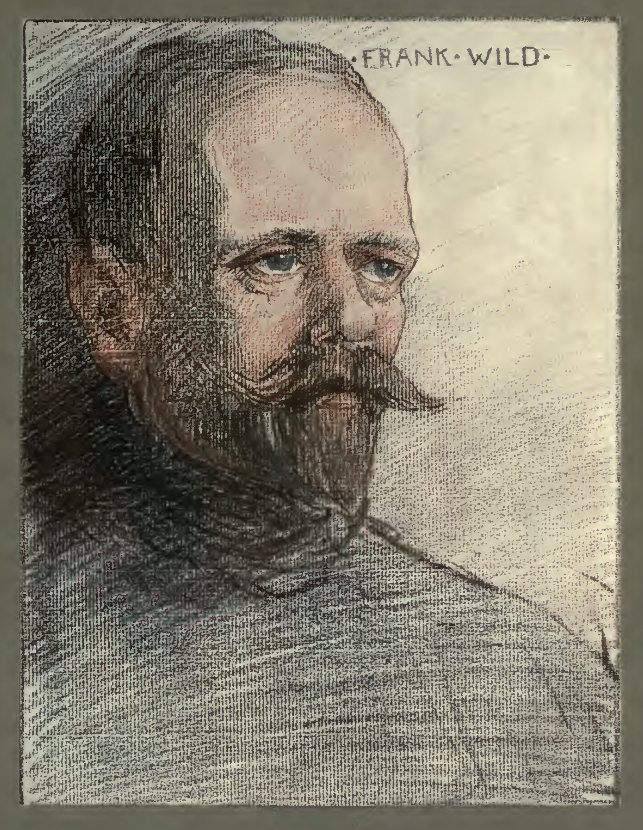

FRANK WILD

EREBUS

BY E.H. SHACKLETON

{Page 21}

EREBUS

EEPER of the Southern Gateway,

grim, rugged, gloomy and grand;

Warden of these wastes

uncharted,

as the years sweep on, you

stand.

At

your head the swinging smoke-cloud; at

your feet the grinding

floes;

Racked and seared by the inner fires, gripped

close by the outer snows.

Proud, unconquered and unyielding, whilst the

untold æons passed,

Inviolate through the ages, your ramparts

spurning the blast,

Till men impelled by a strong desire, broke

through your icy bars;

Fierce was the fight to gain that height where

your stern peak dares the

stars.

You

called your vassals to aid you, and the

leaping blizzard rose,

Driving in furious eddies, blinding, stifling,

cruel snows.

The

grasp of the numbing frost clutched hard

at their hands and faces.

And

the weird gloom made darker still dim-

seen perilous places.

AURORA AUSTRALIS

BY E.H. SHACKLETON

{Page 25}

AURORA AUSTRALIS

HEY, weary, wayworn, and

sleep-

less, through the long withering

night.

Grimly clung to your iron sides

till with laggard Dawn came the

light:

Both heart and brain upheld them, till the

long-drawn strain was

o'er,

Victors then on your crown they stood and

gazed at the Western

Shore;

The distant glory of that land in broad splen-

dour lay unrolled.

With icefield, cape, and mountain height, flame

rose in a sea of gold.

Oh! Herald of returning Suns to the waiting

lands below;

Beacon to their home-seeking feet, far across

the Southern snow;

In

the Northland, in the years to be, pale

Winter's first white sign

Will turn again their thoughts to thee, and the

glamour that is thine.

BATHYBIA

BY D. MAWSON

{Page 29}

BATHYBIA

FAINT stirring seemed to be going on about,

which gradually made itself felt on my yet somnolent senses.

Rising-time was evidently drawing nigh. The uncertainty shortly

came to an end when, in harsh tones, the familiar call sounded:

"Lash up and stow, lash up and stow; 8.30, and time all hands

were up." This announcement, coming as it did from a pair of

lungs boasting of an early training in St. Paul's Cathedral, and

matured in the Navy, was calculated to wake effectually the

profoundest slumberer, but did not prevent me turning over for a

final doze. ¶It hardly seemed any time, however, before we were

exerting our best efforts dragging the sledges onwards towards

the Southern goal. The drudgery of the journey over the great

"sastrugi" ruffled plateau of Victoria Land had now become felt

by all. Everlastingly our eyes wandered over the horizon in

search of new objects, but as yet nothing greeted our gaze more

than had been the bane of our march these last two hundred and

fifty miles, since leaving Mount Lister behind.

¶Why we had ever come to choose our present

route to the South—S.S.W. over the Victoria Land

Plateau—seemed impossible of explanation. It was generally

believed, however, that the strength of the meteorological

element had prevailed in this decision, as it was decidedly a

chance to get abundance of high-level data. Some of the more

outspoken, irritated by the monotony of the journey, now

expressed themselves in no measured terms regarding the

alteration of the original plans. More especially had discontent

arisen because of the fact that this had entailed the

substitution of man-power to the extent of the combined strength

of the expedition in place of the ponies. ¶To-day the march

proved more interesting, as scarcely had we got properly under

way before the Commander drew our attention to a peculiar

appearance in the sky, somewhat to the west of our course. It was

like nothing he had had experience of in this latitude during his

previous exploration with Captain Scott along the Great Ice

Barrier, Resembling open water, it suggested possibilities we had

never till now entertained. As the day wore on, the more real did

this phenomenon appear, so that every one was fired with a new

enthusiasm. The new sledges no longer seemed to offer any

resistance, so that we pressed onwards at a brisk pace for two

days.

The S.W. middle current wind, so prevalent to

the north, had now cut out, and the warmer south-seeking

anti-trade came down to the plateau level, helping us onward.

Some miles ahead a fog-bank hanging low upon the land obscured

the horizon. ¶On the morning of the third day we felt a crisis

was close at hand, as the sky in front contrasted strongly with

the uniform ice-blink we were now leaving behind. The

temperatures perceptibly rose as we came up to the fog-bank. The

tiny particles of ice floating in the air and producing the fog

were now so much more abundant that it was impossible for us to

see more than about a hundred yards ahead. The increased

temperature was due, evidently, to liberation of latent heat set

free by separation of the fog particles. ¶Camp had been pitched

and the "hoosh" served, when the hungry Scotchman was interrupted

in his occupation of devouring any remaining tit-bits by a shout

from without. Inquiring heads appeared from the tents, and

amongst the turmoil that ensued could be heard cries of "The

Bottomless Pit!" "Gehenna!" A moment later our astonished gaze

was greedily devouring the situation. The mist had temporarily

rolled back, revealing a steep slope commencing shortly in front

of us. The gradient increased rapidly until lost to sight in the

mist, a couple of thousand feet below. We appeared to be standing

on the ruin of a huge volcano of unprecedented proportions. The

wall on which we stood extended far to the north and south. Even

as we watched the cloud-bank rolled yet further back, and a more

extended view unfolded to our rapt gaze. The steep gradient,

already noted, ended below in a yet steeper slope, almost

wall-like, whilst dimly, in the depths below, snowless undulating

plains were visible. What a mighty wall guarded the secrets of

the abyss! What grandeur beyond anything to be expected! Our very

souls were elevated and burned with a desire to penetrate the

depths before us: yet how impossible this seemed I How could

mortal man scale such a wall as barred our progress? ¶Whilst our

thoughts ran thus, a better view being obtained to the south, we

descried a steeply dipping slope leading from the plateau down to

the depths below. This was developed in the form of a semi-cone

against the face of the wall, and appeared to be of volcanic

origin. This volcanic slope was certainly quite scaleable, and we

unanimously decided to attempt a descent by it. Many hours

afterwards camp was pitched on the plateau hard by the cone, and

all were oblivious of the sounds of revelry occasioned by the

snorers. ¶The following day the fog again enveloped the

landscape, and the time was spent making the necessary

preparations for the continuance of our journey with packs in

place of sledges. The depth of the abyss before us was very

great, but difficult at the time for us to judge. Afterwards it

proved to be about 30,000 feet, or some 22,000 below sea-level.

When at last the mist rose and we were able to proceed, advance

proved rapid for the first 12,000 feet, as we could glissade for

long stretches at a time; at this level, the temperature having

steadily risen during the descent, the ice-cap began to dwindle

and a lobed front was met extending amongst great accumulations

of morainic material stacked in the form of terraces along the

mountain-side. Thaw-water, developed in pools investing the

erratic boulders distributed over the ice, trickled away to unite

and form crystal-clear streams, soon lost in crevasses, whither

they plunged to swell the muddy waters of sub-glacial channels.

Camp was pitched at this stage, and we indulged in the usual

"hoosh." The air felt quite warm and moist, so much so that

instead of immediately after crawling into our sleeping-bags,

some time was spent in surveying the new scene before us. At

intervals spouting streams leapt from the glacier faces, and,

ploughing deep furrows in the morainic terraces at our feet,

continued their downward courses as mountain torrents, till,

almost lost in the distance below, they appeared as silver

streaks threading their way by winding courses across the

undulating plains of Bathybia, as we had unanimously designated

this region. Loud booming sounds proceeded upwards periodically

from the depths below, occasioned by the precipitation of small

avalanches breaking away from the ice-cap above. Our biologist

was busy examining lichens which coloured the boulders bright

hues. There was abundant evidence of low forms of plant and

animal life, though curiously restricted in range. ¶Affairs had

assumed such an interesting pitch that we lost no time in getting

under way the following day. Novelties appeared on every hand,

until we were in a condition to accept unmoved any new

discoveries, however radical. When at last the steep slopes had

been negotiated and the undulating plains reached, a much fuller

insight into the conditions prevailing in Bathybia had been

gleaned. The summer temperature averaged about 70°F., and was

evenly toned by abundance of water vapour and carbon dioxide in

the atmosphere. The air was distinctly oppressive on account of

its density and moisture, but even this passed unheeded in the

general excitement. The plant life had rapidly increased in

abundance as lower altitudes were reached. These were chiefly

algæ and fungi, though representatives of the mosses, liverworts,

and ferns were not wanting. On the plains a dominant red colour

pervaded the vegetation, owing to prolific growth of red algæ.

The existence of red-coloured plants was of course to be

expected, existing as they did in sunlight from which a large

proportion of the blue end of the spectrum had been eliminated,

in its passage through so great a thickness of atmosphere.

Finally the vegetation had already become very rank, and the

odours distinctive of some species were not at all pleasant.

¶However much the plant life interested us, it did not claim our

attention so much as less pretentious examples of the animal

kingdom. Small crawling, spider-like beasts had been noted close

below the glacier zone; since then larger forms had made their

appearance, some of which looked distinctly formidable. The

biologist had an encounter with one of these large-bodied,

short-legged animals, and was generally regarded as lucky in

securing the specimen without harm to himself. It measured a foot

in length, and was armed with vicious-looking mandibles. Though

not identical with anything we had ever seen before, it much

resembled a magnificent tick, and was pronounced as belonging to

the mite family. The existence of these great ticks constituted a

distinct element of danger, and precautions were taken to guard

against possible injury from that quarter. With this object in

view we were careful always in future to keep our ice-axes within

reach. ¶Our first camp on the plains was never to be forgotten.

Most of the time intended for sleep was spent in ridding

ourselves of an almost microscopic species of mite, which

infested our camping-ground and invaded our persons. We learnt

that a camp in comfort could be expected here only after taking

the precaution previously to burn off the vegetation from the

site. In this way obnoxious creatures were removed. Already our

progress was much impeded by the luxuriance of the vegetation,

and as this state of affairs did not show signs of improving, we

decided to attempt navigation on a river which lay about three

leagues to the north, and appeared to be the main drainage line

of this portion of Bathybia. ¶Some time elapsed before this new

method of procedure could be put to the test. Raft-building was

not without its troubles, as we were unacquainted with the

materials available, and consequently their floating qualities

had to be determined. At length a structure was completed which

rode lightly on the water, and was regarded by the seafarers

amongst us as distinctly promising. In its construction we

employed the dead trunks of huge fungi of a variety capable of

resisting waterlog. Large sheets of fungus several inches in

thickness, found growing over the ground in moist localities,

furnished an excels lent decking; whilst a spyrogyra-like alga

was found to answer splendidly as a cord for binding the

structure. ¶Whilst these preparations were in progress several

incidents of special interest occurred. One of these came near

proving fatal to one who had gained much in favour by rendering

signal service as a mountaineer during our descent. Provisions

had become alarmingly scarce, and a section of the company

decided that members of the scientific staff were much more

likely to excel as connoisseurs in the matter of food-stuffs than

prove experts in shipbuilding. As the labour of examining the

natural products at hand did not present an arduous aspect, the

scientist above referred to came manfully forward and offered his

services in this domain. Instructions were issued to the effect

that explorations should not be conducted far from camp, and the

route proposed to be taken should be clearly defined before

setting out. The investigator had been absent on his quest for

over two hours, and the commander, becoming anxious, set out in

search of the wanderer. The search party had gone hardly a couple

of hundred yards into the jungle when they stumbled upon the

prone body of the missing man. A giant tick was investigating the

carcase, and apparently Just about to commence operations on its

prize. The obnoxious creature was forthwith despatched, and the

body of the martyr reverently taken back to camp. He still

breathed heavily, but no wounds could be found on the body. A

dread feeling seized us, for, though living things had no terror

for us, yet the intangible found us weak. For long the doctor

diligently attended, in the uncertainty of the stroke,

administering small doses of alcohol from our limited medical

store. At last, after twelve hours, success crowned his efforts

and the patient regained consciousness. Even now his senses

seemed to have lapsed,

and in his delirious ramblings, amongst

inarticulate expressions, could be heard, "Yon's the recht stuff,

mon, aye it is!" Later on he seemed to come to himself again, as

he weakly asked for tea. Indeed so frequent became his cravings

for this beverage that one of us was told off specially to keep

up the supply. It was not till the evening of the second day that

the matter was cleared up. All but the night-watch had retired,

when the supposed invalid suddenly stepped briskly from his bed,

and made towards the food-bags with a determination boding ill

for our now inconsiderable stores. On this occasion the

night-watchman proved the value of the institution by quickly

alarming the sleepers and averting what might have proved a

serious catastrophe. Explanations ensued, and we discovered that

the miraculously-healed patient had merely had the good fortune,

as he described it, to discover a succulent alga giving abundance

of intoxicating fluid. No further explanation was required, as

his subsequent behaviour was obvious to every one. ¶Whilst this

drama was being enacted more valuable discoveries were made by

others. The senior geologist, in company with a bodyguard, had

studiously applied his tasting faculties over a wide range of

vegetable products, narrowly averting serious consequences. As a

result of his investigations, three varieties were finally

selected as good for human sustenance. One of these was a

mushroom-type of fungus, the others sweet-tasting algæ. Some of

the algæ contained abundance of oil and made perfect kindling.

With this material spluttering torches could be made on a

moment's notice. We now had abundance of carbohydrate food, but

did not feel disposed to try the culinary qualities of the

monster ticks. ¶That day an unusual disturbance took place in the

atmospheric conditions, so that, instead of the general calmness

which usually existed in this region, we experienced a succession

of cold blasts descending the valley walls. This change reminded

us again of the conditions under which we existed here in

Bathybia: a land where the sun shone red in the morning, pink at

noon, and red in the evening. Our eyes accommodated themselves

surprisingly rapidly to these new circumstances; possibly owing

to previous exercise in the dull pink illumination of modern

drawings-rooms. In the jungle the light was exceedingly dim and

our exploits had to be conducted with great caution. Although,

since the recent discoveries, the food-supply presented no

immediate difficulties, we were loth to remain a winter in these

regions, for, though in summer the conditions were bearable,

there was no guarantee of their remaining so during the long

night of the winter months. As soon, therefore, as the raft was

completed, we launched out on our down-stream voyage, intending

to make the most of our time collecting facts concerning this

wonderful land. Oars of a kind had been fashioned, but were

mostly serviceable in poling the craft off weed-banks, the

current being quite sufficient to take us along at about two

miles per hour. ¶Many were the suggestions offered for cooking

our new food, but finally the amateurs gave over in favour of the

chef, who had the power of making tasteless dishes appetising by

attaching names. The concoctions usually served up in Bathybia

were purees, which, being translated, simply meant fresh-gathered

this or that, immersed in pure river-water, and brought to a

temperature of 212° F. for an hour or more. ¶Naturally more

attention was now bestowed upon the denizens of the river, and

indeed their abundance and variety surprised us. Minute organs

isms belonging to the Rotifers and Tardigrada abounded, whilst

larger species occasionally came into view. We spent many an hour

peering into the waters in search of new finds, and were

abundantly rewarded by queer sights. For several days our

progress continued thus without serious event. The jungle,

however, became alarmingly denser, so that it was now almost

arched overhead and presented a gloomy outlook. Unaccountable

noises and glimpses of strange forms came to us through the weak

light, but unfortunately nearer acquaintance had so far been

avoided. Matters did not improve, so that we were soon hastening

along beneath a complete covering of dense matted vegetation so

effective in blotting out the daylight that, but for the fact

that here was the home of phosphorescent fungi, we should have

been in utter darkness. This greenish-white luminescent forest

seemed weird in the extreme after the red light to which we had

been so much accustomed. ¶Presently our meditations were

disturbed by a volley of strong expletives of a nautical

character coming from the starboard bow. We were just in time to

rescue our comrade from the clutch of a dangerous-looking

spider-like monster, several feet in length, that had attempted

to board us. Invasions of these monster water-bears, as well as

unavoidable affrays with giant species of rotifers, were all too

common during this extraordinary voyage. However, in accordance

with the adage which states that necessity is the mother of

invention, we soon discovered that these beasts without exception

retreated in the face of fire, to which they were entirely

unaccustomed. A supply of torches was kept in readiness as

weapons in the event of need. By the aid of these, also, a better

knowledge of the conditions around us was obtained. The river was

now to all intents and purposes a subterranean stream cutting

through the accumulated remains of dead sunlight-seeking plants,

which still lived only far above, within range of the daylight,

at the upper surface of this dense mass of dead and living

vegetation. This lower zone through which we now passed was not

altogether composed of dead material, but supported abundance of

saprophytic types, chiefly fungi and bacteria. No human being

could exist long under these trying conditions, so that it was

with joy that, after two days, streaks of daylight began to

penetrate the tangled mass above. In a comparatively short time

clear sky stood above us, and the walls of rank vegetation on

either bank slowly dwindled as we proceeded. With the return of

daylight our spirits rose. During the same day we witnessed a

fight between a water-bear and a rotifer, both of giant size.

Each of these was several feet in length and must have been

immensely powerful. The water-bear seized on the rotifer from

behind, and had commenced sucking the life-fluid of his victim,

when, with surprising alacrity, the captive swung round his free

end and seized his adversary in a bunch of tentacles. A furious

combat ensued, in which the water-bear, though much mauled,

proved victor. We judged, from the action of the rotifer, that

something of the nature of an anæsthetic had been injected by his

enemy. Definite proof of this was shortly forthcoming in an

unexpected manner. One of us, who had been in the habit of daily

treating himself to a wash, whether he required it or not, when

we floated out into daylight again, hastened to make up for lost

time, whilst dangling his legs over the stern and, at the same

time, conducting an animated conversation on the relative merits

of deer-stalking in the Highlands and in more populous centres.

Somebody had just made an unusually fitting sally when, above the

ripple of applause, there sounded a wild yell followed by an

apprehensive exclamation, "He's got my other toe!" Quick was the

word and sharp was the action that followed, else we

would never have saved the bather from the

malicious grasp of a giant water-bear. The beast had already

punctured the toe referred to, but was driven off before serious

damage was done. It had had time, however, to inject an

anæsthetic, as our comrade passed into a comatose state after

about one minute, and did not revive for over half an hour. ¶So

accustomed had we now become to our new surroundings that we

passed a few days not unpleasantly, drifting down the stream. The

vegetation, though luxuriant of its kind, grew much less dense,

and we came at length to more or less open country. There plant

life was represented by mushroom-like fungi arranged in clumps

over the plain. Our artist was in specially good spirits, and, on

our mooring alongside the bank, took the opportunity to scramble

on to the top of a clump of giant toadstools hard by, intending

to size up the sketching possibilities of the neighbourhood. A

sharp report shortly afterwards attracted our attention in time

to see him executing evolutions in mid-air about fifteen feet

above the summit of the toadstools and some thirty feet from the

ground. It happened that this particular toadstool was matured

and required to burst it only the slight irritation supplied by

our comrade in mounting. Fortunately the bed was soft to fall

back upon, else a serious accident must have resulted. Our

ingenious engineer was much struck with this demonstration, and

conducted a series of experiments among members of the genus

fungi represented in the neighbourhood. As a result he brought to

camp some time afterwards a huge flat specimen which, he averred,

would make a fine mattress. In kindness of heart the specimen was

given to his companion of the afternoon's adventure. Judging by

the remarks made by the recipient during his sleep, he must have

passed an unusually pleasant night. Indeed the mattress appeared

to be still exerting a magic influence close on to the breakfast

hour, when several attempts failed to rouse the slumberer. Then

up came the ingenious engineer, who, with a prick of an ice-axe

in the proper place, fired the mattress, and shot its burden from

the depths of sleep into broad daylight via the tent roof. ¶From

this point on the river water became increasingly more brackish,

so that we were much exercised in our minds regarding the future

source of our water-supply. After traversing several shallow

lakes, the matter became critical, and we decided to moor up to

the bank. The neighbouring country was almost desert compared

with the jungle left behind. The saline soil supported only

stunted vegetation, except for occasional clumps of mushroom-like

fungi standing on local elevations of the ground. We were some

distance from camp, making a reconnaissance, when a heavy

rain-storm commenced. Perfect shelter was obtained beneath the

umbrella of the fungi. As time went on, however, and the downpour

did not abate, we grew anxious for the safety of our

commissariat. Shortly afterwards we might have been seen marching

back to camp each sheltered under one of these novel umbrellas.

The adjacent country already showed signs of flooding. It was

therefore deemed best to pack our gear and remove it to one of

the elevations. The waters continued to rise even after the rain

ceased, so that our position was again threatened. We were now

thoroughly alarmed, and hastily transferred all our possessions

to a flotilla of queer crafts, consisting of fifteen large

mushroom-shaped fungi set in the floating position, and lashed

together with Alpine rope. Hardly had these preparations been

completed than the lapping waters swept us off in the strong

current. We were eventually carried into a great salt lake. ¶As

the only fresh water available for drinking purposes consisted of

that which chanced to have been caught in the bilges of our

crafts, great relief was felt when a steady wind set in, driving

us gently before it. Two days later we were fortunate enough to

reach the further shore, and, entering the débouchure of a large

stream, succeeded in travelling some distance up it with a still

favourable wind. Finally, on account of the opposing current, we

had to abandon the water and march on land. ¶One morning, just as

most of us were rising, a scampering noise was heard without,

accompanied by encouraging shouts of "Hi yah! hi yah! Stick it,

boy!" Presently one of our equestrians, who had risen early to

take his accustomed morning walk, came riding up, mounted on a

new species of a monstrous mite. He pulled rein with a "How's

this for a specimen, Mr. Biologist!" "Go to

———!" was the answer, which meant that the

scientist was not having any. This portion of our journey proved

very wearying, as our daily marches were extended as long as

possible. The direction in which we had been travelling, being

across the main topographic features of Bathybia, was calculated

to yield a maximum of information in a minimum of time. Time,

however, was now becoming a serious matter, though new

information never failed. Since leaving the great salt basin of

the central regions

our track had consistently risen. The total

amount of this elevation now amounted to close on 6000 feet. The

Jungle was fast becoming too dense to penetrate. Therefore, as a

final coup before retracing our steps, we decided to ascend a

high volcanic cone lying close by our course. From its summit,

some 17,000 feet above, much information might be gained. A

summer snow-cap descended for about 4000 feet, whilst a perpetual

wreath of smoke curled towards the sky from the summit. It was

noon three days later that we made our camp just below the

snow-line. The afternoon was spent by most of us in a visit to

the summit. Hydrocarbons were escaping from fissures in the

ground near the summit, whilst continuous flames played about the

crater where the greater heat kept the escaping gases ignited.

The rocks were very basic and heavy. Metallic iron occurred in

many of the outcrops, and copper fibres were observed in not a

few. However interesting these observations were, they did not

prevent us drinking in the distant panorama. Far behind were the

great salt sea and saline borderlands. Ahead was a sea of jungle

spread over gradually rising plains. Beyond, where frigid

altitudes were reached, a great snowy plateau carried the picture

beyond the horizon. The whole party was overcome with the immense

wild grandeur of the scene, and when it was time for return we

retraced our steps down the snowy slopes in silence. From this

reverie we were suddenly awakened by a shout from the foremost,

who had come upon the body of a huge animal, about four feet in

length, partly buried in the ice. The biologist examined the

beast, and reported it to have affinities between the water-bears

and the mites, but distinct from anything so far noted in

Bathybia. We got to work with our ice-axes and soon had him out.

The body being more or less cylindrical, we found no trouble

rolling our prize to the camp near by. In the first instance our

intention for so doing was merely to astonish our comrades.

However, the biologist, seeing the specimen still intact, asked

that it might be spared till further investigated. It was the

peculiarity of our biologist to save his specimens for

examination during the early morning hours. ¶After supper, it

being the eve of our return journey, a general discussion

regarding the natural history and physical data so far

experienced in Bathybia was instituted. Summarising the various

points brought forward as bearing on a scientific elucidation of

the phenomena, the following are worthy of note. Bathybia was a

great depression some hundreds of miles across, bounded on the

east by a great fault face, but with more gently rising

boundaries in other directions. In fact it might be likened to a

portion, for example, of the basis of the Pacific Ocean from

which the water had been removed. It seemed to us almost certain

that the earth's folding and faulting, giving place to this

configuration, must have taken place at a period corresponding to

a maximum phase of a great ice age, when the Antarctic regions

supported an ice-cap of stupendous thickness. The ice must then

have played the role of rock when the great earth movement

referred to occurred. At a later date, as the ice age passed

away, ablation, removing the ice strata, exposed the deep basin

of Bathybia. The lower portions of this basin, situated below so

great a thickness of atmosphere, was blanketed from the great

cold of the upper regions. To this end, also, the humidity and

increased abundance of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere aided.

Although in succeeding times the highlands above were deeply

buried under snowfields, this deep plateau-locked basin could

keep its floor for the most part unencumbered with water. The

atmospheric circulation, being distinct from that of the outer

earth, presented special features. What was most to be remarked

with respect to the atmosphere was that it contained a minimum of

dust particles; so that, though the air was saturated with

moisture, condensation seldom took place, except along the

borderlands, where fogs were very prevalent. The great

rain-storm, producing the flood we had experienced, was probably

due to an unusual disturbance of an anti-cyclonic nature, whereby

dust-mote-loaded air of the anti-trade belt above had descended,

causing sudden condensation. The waters, continually draining

into a central basin and there evaporating, led to the production

of a residual salt sea. ¶A knowledge of the strata underlying the

basin would have been of the greatest value, but of course

exposures were not available. However, a great accumulation of

coal-producing matter was presented in the jungle zone. Extinct

volcanic activity had been noted along the fault scarp, and

specially interesting was the active volcano on which we now

stood. The great basicity of the lava, and the fact that it

contained metallic elements, and probably also exhalation of

hydrocarbons, showed it to be typical of the deeper earth crust.

The abundance of plant and animal life, and especially the

curious restrictions governing their range, seemed, at first

acquaintance, inexplicable. The biologist now drew attention to

the fact that all the species represented were but curiously

developed forms of types already known to the scientific world.

They had suffered but little variation, though many had increased

enormously in size. Furthermore, it was known that such species

could at one stage or another in their life-history be

transferred for great distances by wind agency. Also many, even

in adult state, after remaining frozen for long periods,

maintained the power of reanimation when thawed out. ¶In the

light of this information, it seemed most reasonable to suppose

that the invasion of plant and animal life had come from warmer

climes through the agency of the anti-trade winds. ¶It was just

about 2 a.m., when a select few were in the act of brewing their

tenth cup of tea since supper, that a movement in one of the

sleeping-bags attracted attention. An arm and then a head

appeared, followed quickly by the rest of the body. Silently the

figure slipped on his boots, and a moment later passed out of the

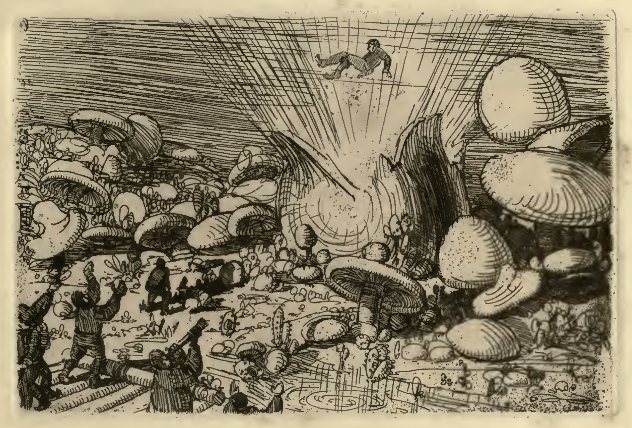

tent with the intention of inspecting his specimen. ¶Almost

immediately a wild commotion rent the air, and as we burst from

the tent a terrifying spectacle met our gaze. The beast we had

left frozen a few hours ago had thawed out and come to life, as

is the wont of the water-bears when subjected once again to

congenial conditions. In this case, however, the term of

hibernation had been extended to centuries, so that no doubt in

the interval this savage species had become practically extinct.

Our comrade was frantically struggling with his specimen, and

into the mêlée we threw ourselves. The din grew louder, and

slowly but surely out of the confusion rose a voice, which smote

clearer upon me: "Rise and shine, you sleepers—8.45, and

time for tables down!" ¶There in the passage was the horrid

figure of the night-watchman replacing our washing-up bowl, which

had just served him as a breakfast-gong. As I sleepily drew on my

clothes, regretful at sacrificing Bathybia for Cape Royds, I

meditated how much can happen in Dreamland during a short

quarter-hour.

PRINTED BY BALLANTYNE AND

COMPANY

LIMITED. AT THE BALLANTYNE

PRESS, TAVISTOCK STREET

COVENT GARDEN

LONDON

[END]

This site is full of FREE ebooks - Project Gutenberg Australia