a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Life of Sir John Franklin, R.N. Author: H D Traill * A Project Gutenberg Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1301261h.html Language: English Date first posted: March 2013 Date most recently March 2013 Produced by: Ned Overton Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Production Note:

Some aspects of the punctuation has been modernised; a number

of misprints (except names) have been corrected. All quotations

are here indented.

SIR JOHN FRANKLIN

PORTRAIT OF SIR JOHN FRANKLIN,

from a drawing by Negelin.

AUTHOR OF 'THE NEW LUCIAN'

'WILLIAM III' 'THE MARQUIS OF SALISBURY'

'LORD STRAFFORD' ETC.

WITH MAPS, PORTRAITS, AND FACSIMILES

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET

1896

The exploits of SIR JOHN FRANKLIN are written so large across the map of the Arctic Ocean and its coasts; the circumstances of his tragic end have rendered his name and achievements familiar to so many Englishmen not otherwise specially conversant with the subject of Polar exploration; the story of his voyages and discoveries has so often been related as a part of the general history of English adventure, that the appearance of this biography, nearly half a century after his death, may seem to require a few explanatory words.

It has been felt by his surviving relatives, as it was felt by his devoted wife and widow, that to the records, ample and appreciative as many of them have been, of the career of the explorer there needed the addition of some personal memoir of the man. What Franklin did may be sufficiently well known to his countrymen already. What he was—how kindly and affectionate, how modest and magnanimous, how loyal in his friendships, how faithful in his allegiance to duty, how deeply and unaffectedly religious—has never been and never could be known to any but his intimates. But that knowledge ought not to be confined to them. The character of such men as Franklin is, in truth, as much a national possession as their fame and work. Its influence may be as potent and its example as inspiring; and it has been felt by those responsible for the production of this volume that some attempt should at last be made to present it to his fellow-countrymen.

It was the long-cherished desire of Miss Sophia Cracroft, niece of Sir John Franklin, and constant and attached companion of Lady Franklin, to perform this labour of love herself, and it supplied the animating motive of her unwearied industry in collecting the mass of documents hitherto unpublished which have been employed in the preparation of this work. Failing health and almost total loss of sight, however, prevented the accomplishment of her purpose, and eventually her executors, Mr. and Mrs. G. B. Austen Lefroy, have entrusted the work to the present writer.

Both to them and to him it is a source of much satisfaction that this Biography should issue from the house of Mr. John Murray, whose father was the publisher of Franklin's two Narratives of his Arctic Explorations and the personal friend of their author and Lady Franklin, and who has himself taken a warm interest in the present undertaking.

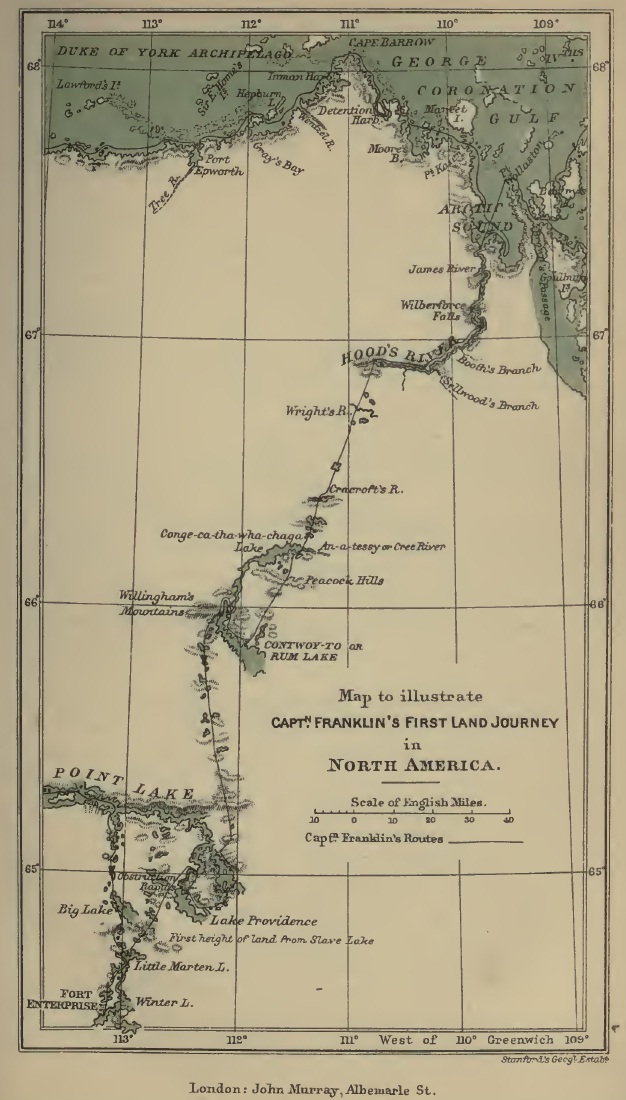

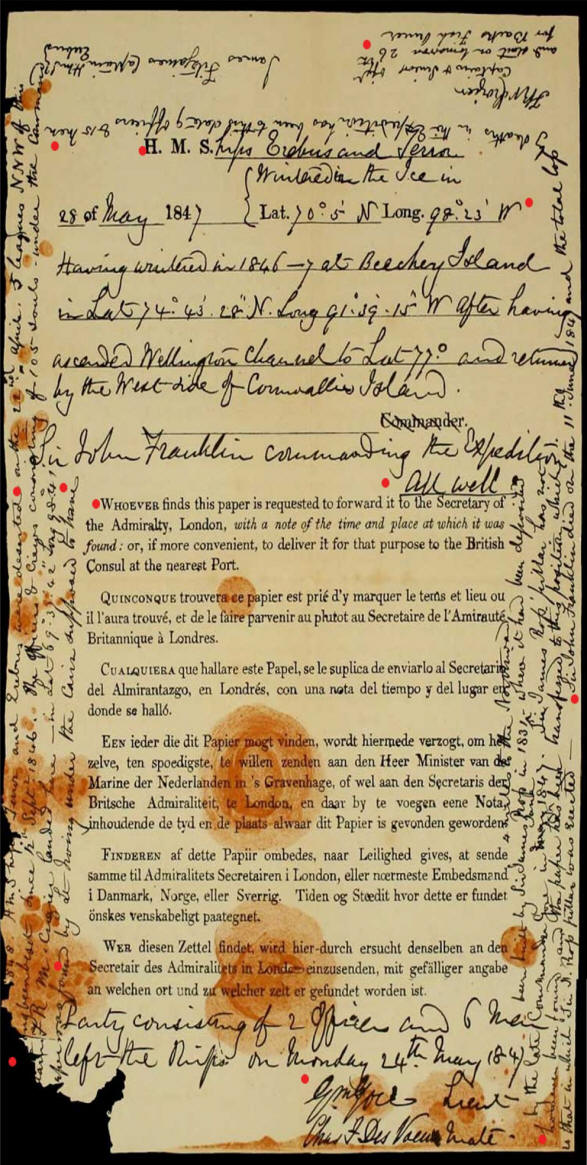

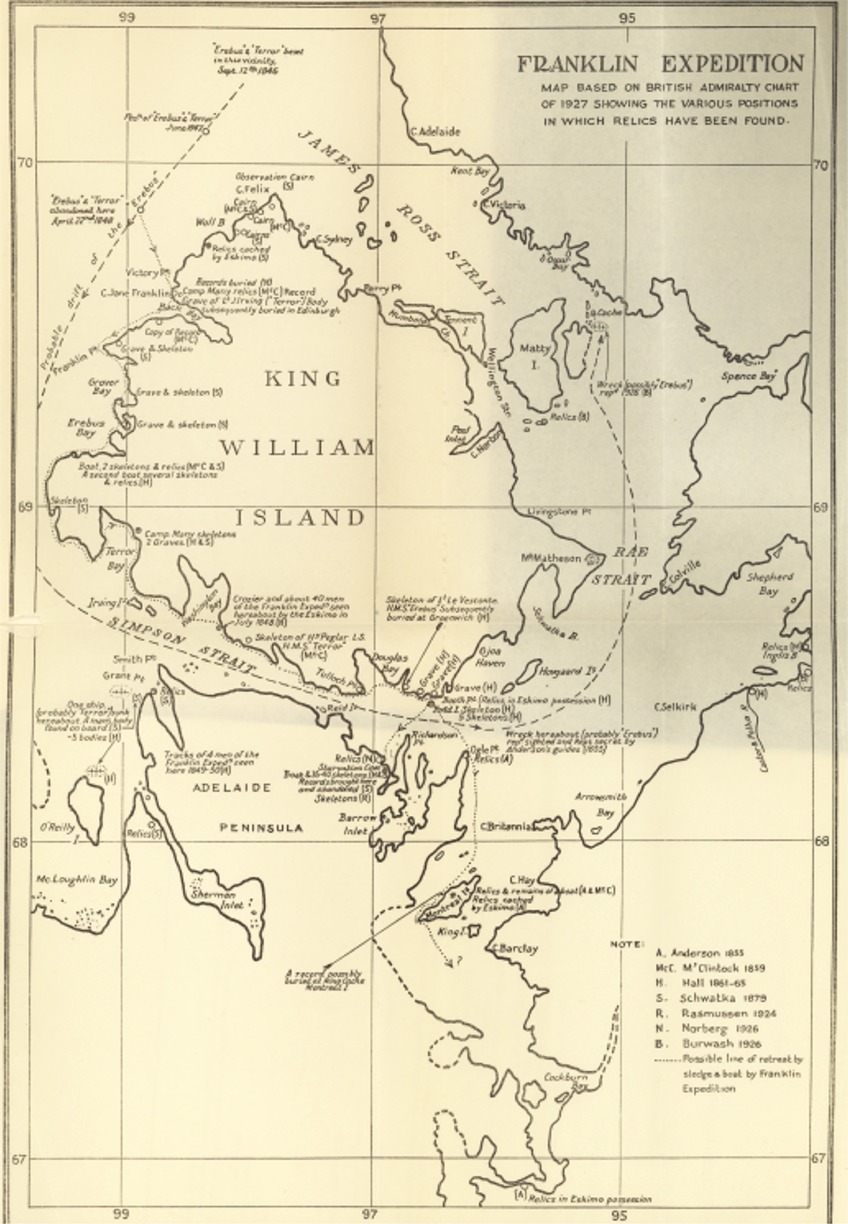

In dealing with Franklin's achievements as an explorer ample assistance was accessible to me in already published works. The story of his first two Arctic expeditions—the former a tale of unexampled toil and sufferings heroically endured—has been told with admirable clearness, simplicity, and modesty by Franklin himself. In 1860, after the return of the Fox from her famous and successful voyage, the late Admiral Sherard Osborn, himself an active and distinguished member of one of the earlier search expeditions, published a little volume of a hundred pages, entitled 'The Career, Last Voyage, and Fate of Franklin', containing a condensed but masterly sketch of his hero's earlier discoveries and a most graphic and moving description of his last ill-starred adventure. The particulars of Sir Leopold McClintock's search for and discovery of the sole extant record of the crews of the Erebus and Terror have been gathered from that gallant officer's painfully interesting narrative of his voyage. But still more important and indeed invaluable help has been derived by me from the able and exhaustive monograph on Franklin contributed to the 'World's Great Explorers' series by Admiral A. H. Markham, himself an Arctic officer of distinction, whose ready kindness, moreover, in advising me on an obscure point in the history of Franklin's closing hours and in perusing the proofs of the chapters dealing with his last expedition I desire most gratefully to acknowledge.

Nor can I close this record of my obligations without expressing my thanks to Miss Jessie Lefroy for such a lightening of my labours by the methodical arrangement of documents as only those who have suffered from the lack of such assistance in examining and digesting voluminous masses of manuscript material can fully appreciate.

H. D. T.

LONDON, 1895.

EARLY YEARS AFLOAT

1786-1807

THE name of Franklin has none of that obscurity of origin which sometimes perplexes a biographer at the very threshold of his work. Its blood and history unmistakably proclaim themselves. The 'franklin' was the old English freeholder—the man who held direct of the Crown, and was frank, or free from any services to a feudal lord. He was, in fact, the original type of the small independent country squire, and so continued to be until, at any rate, the time of Chaucer, whose delightful description of the 'Frankeleyn' pilgrim in the Prologue to the 'Canterbury Tales' distinctly stamps him as of this rank. By Shakespeare's day, however, it is clear that his status had somewhat declined. More than one reference to a 'franklin' and a 'franklin's wife' in the Shakespearian drama shows clearly enough that the word no longer designated any one of sufficient importance to have it written of him that 'at sessions ther was he lord and sire;' still less that 'ful ofte tyme he was knight of the schire.' We may take it as certain, in fact, that before the Elizabethan period the title of 'franklin' had become identified with the order of well-to-do substantial yeomen; and though by that time of course the process of converting the description of men's rank or calling into their surnames had long since completed itself, there were in continuing existence, no doubt, many English families whose surname still represented their status. There were still Franklins by name who had originally been franklins by position. The famous American statesman and natural philosopher claimed descent from 'a family which had been settled for four centuries at Ecton, in Northamptonshire'; and it was from this same sturdy order of Englishmen, for many an age the pillar of the country's prosperity in peace and its right arm in war, that John Franklin, the famous Arctic explorer, sprang.

The family had been East Anglian from as far back as it was possible to trace it. A sister of John Franklin's, who had been at pains to investigate its history, states that her forbears came originally from the county of Norfolk. Her inquiries were not successful enough to enable her to fix the period of migration, but there is evidence dating from the early years of the eighteenth century that the family was at that time settled at Sibsey, near Boston, in Lincolnshire, on an estate which had even then been in their possession for several generations. The wealthier yeomanry of those flourishing times took rank almost as a small local squirearchy, whose members were not always among the most provident of men; and at least two generations of the Sibsey Franklins seem to have lived up to this position with an only too dramatic success. The family tradition, at any rate, is, that John Franklin, the grandfather of the explorer, following paternal example, so greatly reduced the ancestral patrimony as to leave little more at his death than 'a moderate subsistence for his widow'; and, forced to rebuild their fortunes, the Franklins passed, as many a good English house has done before and since, from the ranks of the country gentry into those of trade. John Franklin's widow, 'a woman', writes one of her descendants, 'of masculine capacity and great resolution of character', rose to the occasion. She apprenticed her eldest son Willingham to a grocer and draper in Lincoln, and as soon as he was out of his indentures removed with him to the market town of Spilsby, where she opened a little shop, and, 'not content with acting as housekeeper for her son, superintended the business in every department which admitted of female supervision with the utmost activity and success.' Thanks to her assistance and to his own energy, Willingham prospered in his trade, added to it in due time a banking business, married the daughter of a substantial farmer in 1773, and, six years later, had accumulated sufficient capital to acquire the freehold of his house and shop in the town, and to purchase a small property a few miles off as a place of retreat for his old age. It was in the house at Spilsby, on April 15, 1786, that John Franklin first saw the light.

He was the fifth and youngest son and the ninth child of a patriarchal family of twelve. The second and third of his four elder brothers (the fourth died in infancy) rose, like himself, to distinction in the public service. Willingham Franklin, the second son, who was seven years John's senior, was sent to Westminster and Oxford, becoming scholar of Corpus, and afterwards Fellow of Oriel. He was called to the Bar from the Inner Temple, and was in 1822 appointed Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court at Madras, where, two years later, his career was prematurely cut short by cholera. James Franklin, the third son, entered the East India Company's service as a cadet in 1805, served with credit in the Pindari war, and singled himself out as an officer of considerable scientific attainments. He was employed on important Indian surveys, and after his retirement from the service was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. He died in 1834 at the age of fifty-one.

Of Franklin's seven sisters, two died unmarried: one of them in comparatively early years, the other, Miss Elizabeth Franklin, at an advanced age. Of the five married sisters, two also died before attaining their thirtieth year. Sarah Franklin, the younger of them, had become the wife of Mr. Selwood, and was the mother of the two ladies who married two brothers of a name destined to become illustrious throughout the English-speaking world, and the younger of whom still survives as the Dowager Lady Tennyson, widow of the late Poet Laureate.

A third sister, Hannah, married Mr. John Booth, and their daughter Mary became the wife of Franklin's staunch comrade and friend, Sir John Richardson.

It was, perhaps, with his sister Isabella, the sixth daughter of the family, that John Franklin was the most closely linked in after life. She married Mr. Thomas Robert Cracroft, and it is to the pious labours of her daughter Miss Sophia Cracroft, seconding and prolonging those of Lady Franklin, whose devoted friend and lifelong companion she was, that I am indebted for the copious materials on which this memoir is based.

Henrietta, the youngest daughter, married the Rev. Richard Wright, and died some ten years ago in extreme old age, leaving a son, the present Canon Wright, Rector of Coningsby, Lincolnshire.

The early life of a boy with half a dozen elder brothers and sisters is in most families much the same. He becomes the fag of the one, the pet of the other, and by turns the pride and the plague of their common parents. In John Franklin's case the fagging may have been remitted; but there is distinct evidence of the petting, which, moreover, was no doubt encouraged and justified by the fact that, like many children destined to a vigorous manhood, he was a singularly weak and ailing infant, whose prospect of being reared at all was during the first two or three years of his life considered extremely doubtful. Though undoubtedly of an affectionate and generally docile disposition, John, his brother-in-law Mr. Booth records, was 'not noted, like his brothers and sisters, for neatness and orderliness;' and the combination of this not uncommon failing with a certain harmless propensity—which indeed may even have been the germ of a virtue—led to unpleasant consequences. It was, in fact, the cause of at least one incident which was without precedent in the family, and which is spoken of even in the records of a later generation almost with bated breath. On the landing of the staircase in the house at Spilsby, as probably in many a similar spot in many another English household of that Spartan age, there hung a whip; 'but such was the dutiful obedience at all times paid by the children to their parents' that from an instrument of correction it had declined into a mere emblem of authority. It was reserved, however, for the future explorer to show that, like the sword of the magistrate, it was not borne in vain. Opposite to the Franklins' house stood that of the Rev. Mr. Walls, the owner of Boothby Hall, a gentleman of 'ample private fortune', at whose door the carriages of callers were constantly to be seen. Upon the youngest son of the Franklin family the sight of these arriving and departing visitors exercised an irresistible fascination. Naturally, however, his parents, having regard to that unfortunate want of 'neatness and orderliness' above mentioned, were unwilling to exhibit John as a sample of the Franklin household, and he was 'strictly forbidden to go over the way and stare at this daily spectacle.' But the child 'seemed utterly incapable of putting a curb on his curiosity.' The conclusion of the painful story is almost visible already. A boy of untidy appearance, intensely interested in the fashionable arrivals at the house of a neighbour, and, in defiance of parental injunctions, determined to assist at them: we have here the plot of a domestic tragedy ready made. After repeated commands, repeatedly disobeyed, the emblem of authority became once more an instrument of correction; the whip which hung on the landing was taken down—and used. But, 'though the boy was in no way rebellious on any other point, neither entreaty nor whipping could prevent his punctual attendance at the opposite door whenever a carriage drew up.' It was not exactly the explorer's thirst for discovery, yet perhaps it may have had its latent affinities with that passion. It was certainly gratified with all an explorer's determination. With his mind intently directed towards his childish object, and his will resolutely bent on attaining it, it seems clear that John Franklin accepted his punishment as a mere unpleasant incident of the enterprise, an experience to be submitted to and disregarded, like the Polar cold, or the winter darkness of the Arctic Circle.

But, indeed, there is evidence enough that he was a lad full of adventurous aspirations. There was almost as much of earnest as of jest in the endeavour to outdo the projects of his playfellows, which an anecdote of his boyish years records. The family story goes that, after each of them had specified the particular feat of strength or heroism which he intended to perform on attaining manhood, nothing less ambitious would satisfy young Franklin than the construction of a ladder whereby to 'climb up to heaven.' Gravitation and statical laws were possibly recognised even then as obstacles; but obstacles only existed to be overcome.

To a lad possessed by so early and extravagant a longing to do battle with the forces of Nature, it is a critical moment when he is first confronted with that mighty adversary in its most impressive and defiant form. The turning-point of his career is usually reached on the day when he receives his first challenge from the sea.

To Franklin it was not long in coming. At the age of ten, he was sent to school at St. Ives, whence he was shortly afterwards transferred to that nursery of Lincolnshire worthies, at which Charles and Alfred Tennyson were many years after also educated, the Grammar School at Louth; and one day, during his earlier time at this school, he started off with a playmate to pay his first visit to the coast. His native town of Spilsby, though but a few miles inland, had no connections, by trade or otherwise, with any East Anglian port, and there had been nothing therefore in his surroundings to inspire him with curiosity as to maritime matters or with interest in a seafaring life. But that drop of brine which is in the blood of every Englishman, and which has driven many a youth from the very heart of the Midlands to make his lifelong home upon the ocean, must have stirred in young Franklin's veins. Setting out from Louth one holiday with this young companion, he made his way to Saltfleet, a little watering-place some ten miles off, and there looked for the first time on that world of waters on which he was to play so memorable a part.

That one look was enough. The boy returned home as irrevocably vowed to a sailor's life as though he had been dedicated by some rite of antiquity to the god of the Sea. His father—like nine English fathers out of ten—objected. That curious spirit of parental resistance to what ever has been, and, it is to be hoped, ever will be, the natural and irresistible vocation of so many thousands of English sons, was strong within him. John was his youngest—how often it is the youngest!—the Benjamin of the flock; and it would be a hard matter to part with him, for all his 'want of neatness' and his undue curiosity about the visitors over the way.

Mr. Franklin's attitude, in fact, towards his son's maritime aspirations was simply that adopted before and no doubt since his time by innumerable British fathers similarly situated. It seems only to have differed from the traditional paternal posture in that it was taken up with more intensity of conviction and maintained with more persistency than in the average case. Not many a father, that is to say, would go so far perhaps as to declare, with the elder Franklin, that 'he would rather follow his son to the grave than to the sea;' though many, no doubt, have resorted to the means adopted by him for testing the reality and seriousness of the boy's inclinations. John, after all, was but twelve years old. How many lads of that age, especially during the school term—a very important point—had been seized with what they imagined to be a passion for a seafaring life, but what was in reality only a distaste for the restraints of the class-room or a want of sympathy with the usher! Mr. Franklin accordingly had recourse to a test which fathers in like case have not infrequently applied, with, from their own point of view, complete success. After two years' resistance to his son's importunities he sent him for a cruise on board a merchantman trading between Hull and Lisbon, no doubt in the expectation that from that most efficient of hospitals for the treatment of the sea-fever from which John was supposed to be suffering, he would be able to report himself as 'discharged cured'. But, so far from yielding to this rough remedy—even rougher in those days than in these—the malady became more acute. The boy returned from his voyage confirmed in his longing for a sailor's life; and, this fact once ascertained, Mr. Franklin, like a wise man, gave way. A berth was soon obtained for him as a 'first-class volunteer' on board the Polyphemus, Captain Lawford, and in the autumn of 1800 his eldest brother Thomas was sent up to London with him to procure his outfit and see him off. Duties of this kind are not always dear to the heart of an elder brother, and when he is a young man of twenty-seven, actively engaged in business, and full, as was the case here, of grave business anxieties, some little impatience with the delays of his mission is perhaps excusable. This, at any rate, seems the probable explanation of Thomas's curious proposal to 'place John at school' while awaiting the return of the Polyphemus, then engaged in 'demonstrating' off Elsinore, to Yarmouth Roads. 'I fear', he writes to his father, 'that it will be impossible for me to save Monday'—that is, to return by that day. 'If it is possible I shall do it, for never was I so tired of doing nothing, yet continually running after this nasty cloaths-buying business, which to-morrow I shall compleat.' Still, he speaks with a proper fraternal pride of the result of his labours, and admits that 'the dirk and cocked hat, which are certainly very formidable, are among the most attractive parts of his dress.'

It was not till the end of October that the Polyphemus arrived in port, and that Mr. Allenby, the friend with whom John had been placed in London, was able to tell his father, 'I have just seen your delightful boy off in the Yarmouth coach, inside; paid all for him and gave him ten pounds in his pocket. This I thought necessary, as he has his bedding, &c, to buy at Yarmouth, and if he is admitted to a mess with the officers he will have to subscribe to it' He adds, with what reads like a mild sidelong rebuke of the impatient Thomas: 'I hope that Mr. T. Franklin is gone to Yarmouth to meet him. If not, I hope he will go, as he will not have to attend him again on the same business. In future I have no doubt but he will fight his own way.' The first letter written by the lad as an officer in His Majesty's service gave every indication that he would. For this is the bright, boyish, spirited fashion in which the young middy writes:—

H.M.S. Polyphemus, Yarmouth Roads: March 11, 1801.

Dear Parents,—I take this opportunity to inform you that we were yesterday put under sailing orders for the Baltic, and it is expected that we shall certainly sail this week. It is thought we are going to Elsineur to attempt to take the castle, but some think we cannot succeed. I think they will turn their tale when they consider we have thirty-five sail of the line, exclusive of bombs, frigates, and sloops, and on a moderate consideration there will be one thousand double-shotted guns to be fired as a salute to poor Elsineur Castle at first sight.

Then follows a passage which is interesting as showing that exploration was more in the boy's thoughts even then than the excitement of war:—

I am afraid I shall not have the felicity of going out with Captain Flinders [who was preparing a vessel for a survey of the Australasian coast], for which I am truly sorry, as we in all probability will be out above four months; but if we do return before the Investigator sails, I will thank you to use your interest for me to go. You cannot hesitate asking Captain Lawford to part with me when you consider the advantages of it. Look at Samuel Flinders, who has the promise of getting his commission to go out with his brother. . . .[whereas, in our present service], if we take any ships or make any prize money, it will be two years before we receive it, and very little will fall to my share.

I will thank you when you write to Anne and Willingham to tell them of our expedition up the Baltic, by which some of us will 'lose a fin' or 'the number of our mess', which are sailor's terms.

I will give you the names of the ships which are going with us, and of those which remain in Yarmouth under the command of Admiral Dickson. [Here follows a list of Sir Hyde Parker's fleet] I think we shall play pretty well among the Russians and Danes if they go to war with us.

Please to remember me to my brothers and sisters.

I remain your affectionate

son,

JOHN FRANKLIN.

Excuse my bad writing, as we expect it is the last boat. The ships that remain in Yarmouth are the Princess of Orange, the Texill (54), the Leyden (68), and two or three others for a guard.

Remember me to dear Henrietta, and tell her when I get a ship she shall be my housekeeper. Also to Isabella.

The youthful prophet was right. The 'salute to poor Elsineur Castle' shook Europe, and echoes through our history to the present hour. In less than three weeks after these words were written young Franklin was bearing a part in what the greatest of our naval heroes pronounced 'the most terrible' of the hundred battles he had fought.

The British fleet sailed from Yarmouth on March 12, under Sir Hyde Parker, with Nelson as his second in command, and arrived off Zealand on the 27th. Entering the Sound, in spite of the opposition of the Governor of Cronenberg, who, after protesting against their entrance, opened fire upon them from his batteries as they sailed through that channel on March 30 with a fair wind from the N.W., our vessels bore up towards the harbour of Copenhagen. Menacing indeed was the armament upon which the lad's eyes rested when, after a four hours' sail up the Sound, the Polyphemus came to anchor with the rest of the squadron opposite this famous and formidable port. The garrison of the city consisted of ten thousand men, with whom was combined a still stronger force of volunteers. All that was possible had been done to strengthen the sea-defences, and the array of forts, ramparts, ships of the line, fireships, gunboats, and floating batteries, was such as might well have deterred any other assailant but the hero of the Nile. Six line-of-battle ships and eleven floating batteries, with a large number of smaller vessels, were moored in an external line to protect the entrance to a harbour flanked on either side by two islands, on the smaller of which fifty-six, and on the larger sixty-eight heavy guns were mounted. Four other sail of the line were moored within, across the harbour mouth, while a fort mounting thirty-six powerful pieces of ordnance had been constructed on a shoal, supported by piles. These were so disposed that their fire would cross that of the batteries in the citadel of Copenhagen and on the island of Amager. It seemed hardly possible that any ships could pass over the centre of the deadly circle and live.

Nor were these armaments the only obstacles which confronted the British fleet. The channel, by which alone the harbour could be approached, was little known and extremely intricate; all the buoys had been removed, and the sea on either side abounded with shoals and sandbanks, on which if any of the vessels grounded they would instantly be torn to pieces by the fire from the Danish batteries. The Danes themselves considered this particular barrier insurmountable, and Nelson himself was fully aware of the difficulty of surmounting it; for a day and a night were incessantly occupied by the boats of the fleet, under his orders, in making the necessary soundings and replacing by new buoys those which had been taken away. Despite these precautions, however, and despite all that British seamanship could do in the way of skilled navigation, the harbour shoals proved formidable antagonists when the actual attack was made on the morning of April 2. Of the twelve line-of-battle ships which made fearlessly for the entrance of the harbour, amid the joyous cheers of their crews, on that memorable day, no fewer than three went aground and stuck immovable, exposed to the withering fire of the Tre Kroner batteries and unable to render any effective aid in the attack.

The Polyphemus was in Nelson's division, and was one of those which escaped this untoward mishap. The Edgar, under Captain Murray, led the division, and it was the Agamemnon, the ship immediately behind her, which was the first to go aground. The Polyphemus, which had been the last but three of the line, was signalled to advance out of her turn. Then followed the Monarch, the Ardent, and other vessels. The two that shared the fate of the second vessel in the division were the ships which had been in the immediate rear of Franklin's, the Bellona and the Russell. Nelson followed in the Elephant, and only saved his vessel and the remainder of his division by a swiftly conceived and executed change of course.

Pressing onward, however, with the rest of his force, which had been warned by the fate of the Agamemnon to alter their course, and pass inside instead of, as had been intended, outside the line taken by their leading vessels, the nine remaining vessels reached their stations, and at forty-five minutes past ten the action commenced, becoming general by half-past eleven.

The Polyphemus was soon at it hammer and tongs; and was among the vessels which, during those four furious hours, had the hottest work. Here is an extract from her official log:—

At 10.45 the Danes opened fire upon our leading ships, which was returned as they led in. We led in at 11.20. We anchored by the stern abreast of two of the enemy's ships moored in the channel, the Isis next ahead of us. The force that engaged us was two ships, one of 74, the other of 64 guns. At half-past eleven the action became general, and a continual fire was kept up between us and the enemy's ships and batteries. At noon a very heavy and constant fire was kept up between us and the enemy, and this was continued without intermission until forty-five minutes past two, when the 74 abreast of us ceased firing; but not being able to discern whether she had struck, our fire was kept up fifteen minutes longer, when we could perceive their people making their escape to the shore in boats. We ceased firing and boarded both ships and took possession of them. Several others were also taken possession of by the rest of our ships; one blown up in action, two sunk. Mustered ship's company and found we had six men killed and twenty-four wounded, and two lower-deck guns disabled.

Such was the result of the triple duel between the Polyphemus and the Danish block-ships Wagner and Provestien, assisted by the Tre Kroner battery. The cannonade all round was tremendous, nearly two thousand guns on both sides concentrating their fire upon a space not exceeding a mile and a half in breadth. For three hours had the engagement continued without showing any signs of slackening in its firing; when Sir Hyde Parker signalled to Nelson a permissive order to retire, and there occurred the often related, but recently questioned,* incident of Nelson's putting his telescope to his blind eye. Sir Hyde's motive was a generous one. He had seen with concern the grounding of the three ships, and their almost helpless exposure to the Danish cannonade. 'The fire', Southey reports him as saying, 'is too hot for Nelson; a retreat must be made. I am aware of the consequences to my own personal reputation, but it would be cowardly in me to leave Nelson to bear the whole shame of the failure, if failure it should be deemed.' Doubtless, too, he knew his man well enough to feel confident that if Nelson saw the slightest chance of continuing the contest with success—and the chance must have been slight indeed which did not satisfy Nelson—he would disobey the order. Figuratively in fact, if not literally speaking, he foresaw the legendary application of the telescope to the blind eye, and his foresight proved accurate. Nelson failed to 'see' the signal, and, nailing his own colours to the mast, prolonged the desperate fight for another hour, until, the rapidity and precision of the British fire having at last proved irresistible, the Danish replies began at two o'clock in the afternoon to abate sensibly in vigour. Ship after ship struck amid the cheers of our sailors, and before three the whole force of the six line-of-battle ships and the eleven floating batteries which had formed the front line of defence were either taken, sunk, burnt, or otherwise destroyed. Finally, the resistance of the enemy having now been completely broken down, Nelson sent proposals for an armistice, which were accepted, and the attacking squadron drew off to rejoin Sir Hyde Parker's ships in the centre of the Straits. The loss on board the British fleet was very severe. It was no less than 1,200 killed and wounded, a larger proportion to the number of seamen engaged than in any other general action during the whole war. On the side of the Danes, however, it was much greater, the total number of killed, wounded, and prisoners amounting to 6,000.

[* See Professor J. K. Laughton's Nelson. 'Men of Action Series.' (Macmillan.)]

The condition indeed of the enemy at the close of the action presented a heart-rending spectacle. White flags were flying from every mast that was yet erect, and guns of distress booming from every hull that was still afloat. The sea was thickly covered with the floating spars, and lurid with the light of flaming wrecks. English boats thronged the waters endeavouring to render all the assistance in their power to their wounded and drowning enemies, who as fast as they could be rescued were sent ashore; but great numbers perished. It was not till daybreak on the following morning that Nelson's flag-ship, the Elephant, which had gone aground in returning to Sir Hyde Parker's squadron, was got afloat and the prizes carried off.

Thus ended this murderous battle, one of the most obstinately contested in the annals of the British Navy. For the boy Franklin it was a baptism of fire indeed; and even in those days of the Great War, when Englishmen thought nothing of sending their children almost from the nursery to the cockpit, the case of this lad of fifteen who passed with such startling abruptness from the sleepy peace of a Lincolnshire country town to the thunder and slaughter of the dreadful day of Copenhagen can hardly have had many parallels. There could, at any rate, have been no more dramatically appropriate opening to a life of peril and adventure destined to be crowned by a tragic death.

The horrors of the scene produced, as well as they might, a deep impression on young Franklin's mind; and a kinsman records having been told by him in later years that 'he saw a prodigious number of the slain at the bottom of the remarkably clear water of that harbour, men who had perished on both sides in that most sanguinary action.' But exultation over the victory and pride at having borne a part in it were, of course, more enduring sentiments in the young midshipman's mind. He was genuinely attached to his profession and happy in its pursuit; and even from the few written records which have been preserved of this early period of his career one can gather details which shape themselves into an attractive, if imperfect, picture of the lad. The weakliness from which, as already mentioned, he had suffered in his infancy had long since disappeared. Even in his school days he was remarkable, relates a reminiscent of that time, Mr. Tennyson d'Eyncourt, 'for his manly figure and bravery', and his 'flowing hair;' and both then and afterwards he appears to have struck observers by a peculiar earnestness and animation of countenance. The characteristic which had impressed Mr. Tennyson d'Eyncourt in the face of the schoolboy is noted, curiously enough, almost in the same words, by an officer who met him when on the verge of manhood, and who subsequently testified to the accuracy of the observation by at once recognising him again after a lapse of forty years. This witness also speaks of him as a youth 'with a most animated face'. It was doubtless the immature and undeveloped form of that fine expression of energy and daring which distinguishes his later portraits. In other physical respects, too, the boy appears to have been 'the father of the man'; for 'the round-faced, round-headed' lad with an evident tendency to 'put on flesh' who is described elsewhere in the last-quoted of these accounts might very well ripen into the portly and full-bodied Franklin of middle age.

His ways and disposition were evidently full of charm. From many slight but sufficient indications, traceable even in the scanty reminiscences of this far-off time, one can plainly discern those winning qualities which afterwards endeared him, beyond all leaders that one has ever heard of, to his companions in adventure. There is the same frankness of speech and bearing, the same open and affectionate disposition, and no doubt, too, the same hot but generous temper, which in after years made him at once so quick to resent a slight and so ready to forgive it.

His fear lest the despatch of the Polyphemus to the Baltic should make him lose the chance of joining the exploring expedition to the South Seas proved fortunately groundless. Had he been too late to join it, the whole course of his career might have been altered. He might quite possibly have settled down into the life of the ordinary naval officer and never have acquired that passion for geographical discovery which afterwards bore such brilliant fruits. But the hope expressed by him in the letter above quoted was realised. The Polyphemus was ordered home with the rest of the Baltic fleet in the summer of 1801; and a berth was obtained for Franklin on board the Investigator, which started for the Southern Hemisphere on July 7 of that year. Her commander, Captain Matthew Flinders, who had married an aunt of Franklin's, was a sailor of first-rate capacity, and had already won high distinction as an explorer in the seas to which he had now been despatched on no less ambitious an enterprise than that of effecting a survey of the entire seaboard of Australia. There could have been no better school or schoolmaster for a youth of John Franklin's bent and aspirations. He was proud of his commander's achievements, and attached to him both by relationship and regard. The character of his duties was in many respects novel, and his voyage, he was aware, would procure him an amount of training in navigation and practical seamanship which he could not have acquired with anything like the same expedition in the regular service of the navy. Of the spirit in which he entered on his duties we may judge by the following extract from a letter of Captain Flinders to the elder Franklin:—

It is with great pleasure that I tell you of the good conduct of John. He is a very fine youth, and there is every probability of his doing credit to the Investigator and himself. Mr. Crossley has begun with him, and in a few months he will be sufficient of an astronomer to be my right-hand man in that way. His attention to his duty has gained him the esteem of the first lieutenant, who scarcely knows how to talk enough in his praise. He is rated midshipman, and I sincerely hope that an early opportunity after his time is served will enable me to show the regard I have for your family and his merit.

By October of 1801 the Investigator had reached the Cape of Good Hope, and from that station Franklin wrote his father a letter describing the incidents of the voyage. They had touched at Madeira on the way out, and the lad's account of that island and its people abounds in evidences of an observant faculty beyond his years. Now, as always, he was studying more than the mere routine of his profession, in the scientific branches of which, however, he was obviously making good progress. He was, indeed, acquiring a proficiency for which he did not obtain quite his fair amount of recognition; for it would seem that Sam Flinders, his captain's brother was in the habit of entrusting to him a considerable share of the duty of taking observations without being equally careful in distributing the credit of the results. To this 'exploitation' of himself young Franklin thought it wise to submit, though not without privately recorded protests; and it is with some natural feelings of resentful relief that later on he chronicles the fact of Sam's having exchanged his berth on the Investigator for a post which his brother had succeeded in obtaining for him on board another vessel.

The elder Flinders did much, however, to atone for the unsatisfactory conduct of the younger. He instructed his nephew pretty steadily in navigation and relieved him when at sea of day watches, Franklin reports, in order to enable him to attend his captain 'in working his timepieces, lunars, &c.;' so that, on the whole, the eager young sailor had no reason to be dissatisfied with his opportunities of self-improvement. The example of the fine seaman and enthusiastic explorer under whom he served must indeed, for a lad of Franklin's ardent temperament, have been an education in itself. Throughout his whole life he cherished the warmest admiration for the character of Matthew Flinders, and in later years he gladly welcomed the opportunity of paying an enduring tribute to his old commander's memory in that very region of the world which his discoveries had done so much to conquer for civilisation.

In the summer of 1802, when, after having surveyed the whole of the southern coast of the Australian continent from King George's Sound in Western Australia to Port Jackson, the Investigator was refitting in that harbour, Franklin wrote his mother a letter full of that dutiful simplicity of filial affection which was so marked a feature in his character. 'I take this opportunity', he says, in the quaintly ceremonious manner of the time,

of returning my most sincere thanks to my worthy parents for their care of me in my younger days, for my education, and lastly for the genteel and expensive outfit for this long voyage; and if a due application to my duty and anxiety to push forward in my profession will repay them, they may rely on it as far as I'm able. ... My father, I trust and hope, is more easy about the situation in life I have chosen. He sees it was not either the youthful whim of the moment, or the attractive uniform, or the hopes of getting rid of school that drew me to think of it. No! I pictured to myself both the hardships and pleasures of a sailor's life (even to the extreme) before ever it was told to me; which I find in a great measure to agree. My mind was then so steadfastly bent on going to sea, that to settle to business would be merely impossible. Probably my father, like many others who are unacquainted with the sea, thinks that sailors are a careless, swearing, reprobate, and good-for-nothing set of men. Do not let that idea possess you, or condemn all for some. Believe me, there are good and bad men sailors. It is natural for a person who has been living on salt junk for several months when he gets on shore to swag about. Picture to yourself a man debarred from all sorts of comfortables such as mutton, beef, vegetables, wine, and beer. Would he not after that bar was broke begin with double vigour? But I have said enough on this subject. A line in answer to this would satisfy me.

Later on in the letter he reverts to a matter which was seldom absent from his mind—the necessity of steady endeavour to perfect himself in his profession:—

Thank you for that good and genuine advice in your letter. . . The first thing which demands immediate attention is the learning perfectly my duty as an officer and seaman. It would be an unpardonable shame if after serving two years I was ignorant of it. The next, the taking and working of astronomical observations which (thank God!) by the assistance of Captain Flinders I am now nearly able to do. Then French: many is the time I have envied the hours spent in play instead of learning. Now I feel the want of a knowledge of French, for there are two ships of that nation engaged in discovery here and I'm not able to converse with them in French, but am obliged to refer to unfamiliar Latin.

Writing a few months later to his sister Elizabeth, he gives a detailed account of his reading, interspersed with criticisms, amusing in their youthful air of profundity, on the subjects of his study:—

The following are the books which I read in my leisure hours (inform me, do you approve of them?):—'Junius's Letters.' What astonishing criticisms! What a knowledge of the State affairs at that time! But he was at last mastered by Horne Tooke, who had a right cause to handle. 'Shakespeare's Works.'—How well must that man have been acquainted with man and nature! The beautiful sympathetic speeches he makes them use! Of comedies, the 'Taming of the Shrew' and the 'Merry Wives of Windsor' are his masterpieces. Of tragedy, 'Macbeth' and 'King John'. History of Scotland, from the Encyclopaedia, 'Naval Tactics', 'Roderick Random', 'Peregrine Pickle', sometimes Pope's Works. And, exclusive of navigation books and Latin and French, geography sometimes employs a good deal of my time, as was the request of my brother Thomas in his last letter.

He winds up with a piece of information most interesting to a sister—

I am grown very much indeed, and a little thinner, so that I shall be a spruce and genteel young man, and sail within three points of the wind, and run nine knots under close-reefed topsails, which is good sailing—

and also admirably well adapted to bewilder the female mind, as was no doubt its intention, with its shower of unfamiliar nautical expressions.

The pursuit of literature, however, could only have been the occupation of a not very abundant leisure; for it is certain that Franklin was kept pretty fully employed during his stay at Sydney in assisting to promote the scientific objects of the voyage. An observatory was set up on shore, to which all the chronometers were removed, and where all the necessary observations were taken. It was placed under the charge of Samuel Flinders, to whom Franklin was attached as assistant; and his services in that capacity were thought at least sufficiently worthy of recognition by the local authorities to have earned for him the humorous appellation of 'Mr Tycho Brahé' from Governor King, then presiding over the colony of New South Wales.

A few days after the letter last quoted was written, the vessel resumed its voyage, which, however, was destined to be cut short by unforeseen causes before its object was fully attained. Unfortunately, it turned out that the scientific curiosity of the Admiralty had not, like charity, begun at home. Before commissioning the Investigator to survey the coast of New Holland it would have been better to more carefully survey the Investigator. After rounding the north-east point of the continent and entering the Gulf of Carpentaria, the extensive coast-line of which was examined and duly delineated on the chart, the old vessel began to 'exhibit unmistakable signs of decay'; and it was discovered on examination that her timbers were in so rotten a condition that it was not considered likely that she would hold together in ordinary weather for more than six months, while in the event of her being caught in a gale she would in all probability founder. Her commander, it is true, was not unprepared for this discovery. Evidence of her general unseaworthiness had come to light, indeed, before she had reached Madeira on her outward voyage; but, as Captain Flinders characteristically put it, he had been 'given to understand that the exigencies of the Navy were such that no better ship could be spared from the service, and his anxiety to complete the investigation of the coasts of Terra Australis did not admit of his refusing the one offered.' Admirable, however, as is the spirit of a naval officer whose ardour in adventure will not permit him to decline the offer of a rotten ship if a sound one is not to be had, one cannot feel equally impressed with the conduct of naval authorities who send him out in such a vessel to explore the entire seaboard of Australia, with an injunction 'not to return to England until that work is satisfactorily accomplished.' As it was, Captain Flinders had all his work cut out for him to return, not to England, but to Sydney, which port he succeeded in reaching in June 1803, after an anxious and perilous voyage round the west coast of Australia. At Sydney the Investigator was again examined, and the experts by whom she was examined having reported her 'not worth repairing in any country', she was ultimately converted into a storehouse hulk, and it was arranged that Flinders, with a portion of his officers and crew, should return home in the Porpoise, in order to report the facts of the case to the Admiralty and endeavour to obtain another vessel in which to continue the work of Australian exploration.

The breakdown of the Investigator was, however, but the first of the series of misadventures which Franklin was destined to meet with in this his maiden cruise as an explorer. Six days out of Sydney the Porpoise, making for the newly discovered Torres Strait with two merchant vessels under its pilotage, struck upon a reef—a fate which was shared by one of its consorts—the other making off, one regrets to record, without rendering any assistance. The disaster occurred towards nightfall, and, the ships fortunately holding together until the morning, their crews managed to effect a landing, with such of the provisions and stores of the two vessels as they were able to save, on a sandbank some nine hundred feet by fifty, about half a mile from the wreck. Their position here, however, was sufficiently critical. The nearest known land was two hundred miles off, and Sydney, the only place from which assistance was to be hoped for, they had left nearly four times that distance behind them. It is needless to say that they faced the situation with the cheerful pluck and resourcefulness of their nation and calling. Tents were erected with the salvaged sails; a blue ensign with the union-jack down was hoisted on a tall spar as a signal of distress; an inventory of stores was taken and found sufficient to last the ninety-four castaways, if properly husbanded, for a period of three months. A council of officers was then called, and it was decided that one of the six-oared cutters should be despatched to Sydney, under the command of the indomitable Flinders, to obtain relief. Accordingly, on August 27, accompanied by the commander of the lost merchant ship and twelve men, and having stored his small boat with provisions and water for three weeks, that officer set out on his doubtful and hazardous voyage of seven hundred and fifty miles. Week after week passed, and at length, on October 7, when their stores were beginning to run low and the castaways were within measurable distance of the date at which it had been resolved that if no help came they would themselves make a desperate dash for the mainland of Australia in two boats which they had constructed out of materials saved from the wreck, they caught the welcome sight of a sail. It was Flinders returning from Sydney in the Rolla, bound for Canton, accompanied by the two Government schooners Cumberland and Francis. Franklin, with the bulk of the shipwrecked crew, embarked on board the first-named vessel; his captain, anxious to get home as soon as possible to report his discoveries and prepare his charts for publication, preferred to return to England at once in the Cumberland. It was a fatal choice. The vessel touched at the Mauritius on its way home, and there, by one of those many acts of downright brigandage which disgraced the name of France at the rupture of the Treaty of Amiens, he was made a prisoner by the French Governor of the island and detained for no less than six and a half years. He lived, this much-enduring Ulysses, to return to England and to write an account of his memorable voyage; but the volume and the charts accompanying it, which he had lost his liberty in hurrying home to publish, only issued from the press, by a truly tragic coincidence, on the very day of his death.

Franklin had gone to Canton in the Rolla to await a homeward-bound ship, but there were yet further adventures in store for him before reaching England. A squadron of sixteen Indiamen was on the point of sailing, under the command of Commodore Nathaniel Dance, of the H.E.I.C.S.; and the officers and men of the Investigator were distributed among its vessels, Franklin's berth falling to him on board the Earl Camden, which flew the commodore's flag. They carried arms, did these merchantmen of John Company, as indeed such vessels mostly did in those troublous times; but their guns, from thirty to thirty-six in number, were of light calibre, and the gallant vessels relied rather upon the 'brag' of their appearance than on their real fighting power; for their hulls were painted in imitation of line-of-battle ships and frigates, the more easily to deceive the enemy's cruisers and privateers. They could hardly hope, however, to escape the attentions of a powerful French squadron by devices of this kind; and it was with such a squadron that they were fated to fall in. Its commander, Admiral Linois, was not otherwise than a brave and capable officer, and the five vessels under his command, consisting of the Marengo, a line-of-battle ship of 84 guns, La Belle Poule, 48, two other vessels of 36 and 24 guns respectively, and an eighteen-gun brig under Dutch colours, were no doubt considerably more than a match in fighting power for the fleet of Indiamen. Yet this did not prevent the Admiral and his squadron from getting quite comically the worst of one of the most singular encounters in the whole of our naval history. Linois, having received news of the sailing of the Indiamen from Canton, put to sea at once from Batavia, and came across his intended captures as they were entering the Straits of Malacca. Their behaviour, however, was contrary to all maritime precedent. A witty countryman of the Admiral has in two often-quoted lines expressed the scandalised astonishment with which the hunter would naturally regard resistance on the part of a usually fugitive quarry—

Cet animal est très méchant:

Lorsqu'on attaque, il se défend—

and Linois found to his surprise that these particular merchantmen were animals of just this vicious temper. Instead of making all sail to escape their pursuers, they formed in order of battle, and showed every sign of preparing for a regular engagement. It was late in the afternoon; and the phenomenon was so perplexing that the French Admiral not unnaturally thought he might as well take a night to consider it, and decided to postpone the attack till the following morning. Under cover of the darkness the English ships might, no doubt, have made their escape without difficulty, but Commodore Dance had no intention of thus spoiling so pretty a quarrel. His ships lay to for the night; and Linois finding them in the same position next day began to suspect that they must consist partly of men-of-war, and continued to hold aloof. Thereupon Dance gave orders for his ships to continue their course under easy sail. The French Admiral, encouraged by this movement, pressed forward with the design of cutting off some of the rearward ships. Upon this, however, the English Commodore instantly faced about, and young Franklin, who was acting as signal-midshipman, was ordered to run up the signal: 'Tack in succession, bear down in line ahead, and engage the enemy.'

Whether in the King's uniform or out of it, Jack in all ages of our history has asked nothing better; and as quickly as this manœuvre could be executed the two squadrons engaged. The action was short and sharp, if not exactly decisive. After three-quarters of an hour of it the French ceased firing and drew off, whereupon the insatiable Dance actually gave the signal for a 'general chase', and the astonished seas beheld the unique spectacle of sixteen English merchantmen in hot pursuit of a French squadron of war. The Commodore gave chase for 'upwards of two hours', and then, rightly concluding that he had done enough for honour, recalled his pursuing ships, proceeded on his homeward course, and duly arrived in England to be rewarded with a well-merited knighthood. It was one of the most dashing feats of 'bounce' on record, and deserves to rank with that other and better known exploit of heroic impudence which has for generations been celebrated in many a gruff forecastle chorus to the refrain of the 'Saucy Arethusa'.

How Franklin's services on this occasion were appreciated by his commander the following extract from a letter, written by Sir Nathaniel Dance a year later, will show. Addressing Mr. William Ramsay, an official of the East India Company, he says:

I beg leave to present to the notice of the Hon. Court, Mr. Franklin and Mr. Olive, midshipmen in His Majesty's Navy, who were cast away with Lieut. Fowler in the Porpoise, and who were, as well as that gentleman, passengers for England on board the Earl Camden. Whatever may have been the merits of others, theirs in their station were equally conspicuous, and I should find it difficult in the ship's company to name any one who for zeal and alacrity of service and for general good conduct could advance a stronger claim to approbation and reward.

On August 6 the Earl Camden arrived in the English Channel, and for the first time after a prolonged interval of enforced silence the young sailor was able to communicate with his family. His prolonged cruise had been full of trials and not free from disaster, but he dwells in his usual mood of cheery contentment on its compensating gains:—

Although mishaps seem to attend every companion of the voyage—viz. a rotten ship, being wrecked, the worthy commander detained, and the great expense of twice fitting out—yet do we cheer ourselves with a well-founded idea that we have gained some knowledge and experience, both professional and general, even while visiting the dreary and uncultivated regions of New Holland.

His father had in the meantime retired from business to the retreat which he had provided for himself many years before, and thus the son overwhelms him with inquiries:—

I have formed many and various conjectures concerning the Enderby House and enjoyments, and of the residences and situation of my dear brothers and sisters, particularly of Willingham, not having heard of or from him since 1801, nor from Spilsby since June 1802. Sensible of the pleasure the receipt of letters will afford, particularly from home, I trust some kind person will not fail answering this by return, and mention how every member of the family is—whether any of the Spilsby friends are dead, whether the old town looks gay, whether you have received Captain Palmer's account of the Porpoise's wreck, dated January 10, 1804, and how my old acquaintances in and about Spilsby are. Some of them have, I expect, paid the debt of Nature.

A truly characteristic midshipman's account of information-arrears.

On August 7, 1804, Franklin was discharged from the Earl Camden, and on the following day he was appointed to H.M.S. Bellerophon, Captain Loring, which now historic vessel, after a six weeks' leave spent with his family and friends, he joined on September 20. And, just as he had left home for the first time to fight in the great battle of Copenhagen, so now, at the end of his first short leave of absence, he quitted England to take part, after only a few months' longer interval, in the still more memorable struggle of Trafalgar.

The winter of 1804 was spent in blockading the French fleet in the harbour of Brest, a new experience for Franklin in naval operations. In April of the following year Captain Loring was succeeded in the command of the Bellerophon by Captain James Cooke, whom the midshipman, in that tone of kindly patronage which not infrequently marks the gun-room's criticism of the commanding officer, describes to his mother as seeming 'very gentlemanly and active;' adding, 'I like his appearance much.' The weary blockade was still continuing, though spring was ripening into summer; and Franklin, seizing an opportunity at Cawsand Bay for an 'epistolary conversation with my relatives previous to our departure to resume this station', goes on to say:—

We have victualled and stored our ship for six months, for the purpose of being in perfect preparation to chase the Brest fleet, should any of them think of moving this summer. There are twelve sail of us which have fitted for foreign service; but I believe for no better reason than the above. Some rumours have sent us out to the West Indies, others off Cadiz, and some to the East Indies; but certainly without foundation.

Then his thoughts reverting to his father's newly adopted country life, the young sailor continues in youth's diverting vein of didactic reflection:—

I trust my father keeps his health and spirits. The farm at this season of the year must afford him much amusement. The green fields, the approaching harvest, all tend to gladden the heart of the farmer, who measures, as it were, every ray of sun and drop of rain, and is able to tell that this does good and that harm.

Later on in the letter he adds:—

The Devonshire fields promise good crops. I hope Lincolnshire does likewise. Days begin to grow long and the shore very pleasant. I have been on shore once and enjoyed a long walk. To us Channel-gropers, believe me, a walk on shore, even in the detestable borders of the seaport, is charming.

Cadiz proved, after all, to be the destination of the Bellerophon. She sailed in the summer for that port, and remained there for some time under Lord Collingwood's orders, when she was detached with three other ships to convoy the transports and troops despatched from England to Malta with secret orders, supposed, as Franklin says, to be 'for landing in Egypt should Bonaparte endeavour to march any force towards our Indian settlements.' Returning from this duty, the squadron was ordered to blockade the port and harbour of Carthagena, wherein lay six line-of-battle ships which by some accident had been prevented from joining the combined fleets of France and Spain, then in the West Indies, with Nelson hunting for them in vain.

Events meanwhile were rapidly working up to the dramatic climax of Trafalgar. From the same letter, concluded three days later, Franklin reports the great Admiral's return to Cadiz after the final abandonment of his West Indian chase; and a little later Collingwood's command was taken over from him by Nelson, and the British fleet, consisting of twenty-seven sail of the line and three frigates, was concentrated off the Spanish coast. Yet another month, and on the ever-memorable October 21 it closed with those of France and Spain in that tremendous conflict which was to shatter Napoleon's hopes of conquest and leave the British flag supreme on every sea.

The Bellerophon, as all the world knows, was in the thick of the battle, and Franklin, again appointed to the post of signal midshipman, was in the hottest of the fire that swept her decks. The following account of one of the most dramatic incidents of the action was afterwards given by him to his brother-in-law, Mr. Booth:—

Very early in the engagement the Bellerophon's masts became entangled with and caught fast hold of a French line-of-battle ship [apparently L'Aigle]. Though the masts were pretty close together at the top, there was a space between them below, but not so great as to prevent the French sailors from trying to board the Bellerophon. In the attempt their hands received severe blows, as they laid hold of the side of the ship, from whatever the English sailors could lay their hands on. In this way hundreds of Frenchmen fell between the ships and were drowned. While the Bellerophon was fastened to the enemy on one side, another French man-of-war was at liberty to turn round and fire first one broadside and then another into the English ship. In consequence 300 men were killed on board the Bellerophon. At last, after a very sharp contest, the French ship which was at liberty received such a severe handling that she veered about and sailed away; but still a desultory yet destructive warfare was carried on between the two entangled ships, until out of forty-seven men upon the quarter-deck, of whom Franklin was one, all were either killed or wounded but seven. Towards the end of the action only a very few guns could be fired on either of the ships, the sailors were so disabled. But there remained a man in the foretop of the enemy's ship, wearing a cocked hat, who had during the engagement taken off with his rifle several of the officers and men. [It was a shot from one of these sharpshooters in the rigging of the Redoutable, it will be remembered, that struck Nelson down.] Franklin was standing close by, and speaking to a midshipman, his most esteemed friend, when the fellow above shot him and he fell dead at his comrade's feet. Soon after, Franklin and a sergeant of Marines were carrying down a black seaman to have his wounds dressed, when a ball from the rifleman entered his breast and killed the poor fellow as they carried him along. Franklin said to the sergeant, 'He'll have you next;' but the sergeant swore he should not, and said that he would go below to a quarter of the ship from which he could command the French rifleman, and would never cease firing at him till he had killed him. As Franklin was going back on the deck, keeping his eye on the rifleman, he saw the fellow lift his rifle to his shoulder and aim at him; but with an elasticity very common in his family he bounded behind a mast. Rapid as the movement was, the ball from the rifle entered the deck of the ship a few feet behind him. Meantime, so few guns were being discharged that he could hear the sergeant firing away with his musket from below, and, looking out from behind the mast, he saw the rifleman, whose features he vowed he should never forget so long as he lived, fall over headforemost into the sea. Upon the sergeant coming up, he asked him how many times he fired: 'I killed him', said the sergeant, 'at the seventh shot.'

Franklin himself escaped without a wound. Throughout the greater part of the fight he had been stationed on the poop, and he was one out of only four or five in that quarter of the ship who emerged unscathed from the struggle. But even upon him it left its mark in an injury invisible indeed but not unfelt. 'After Trafalgar,' says one of his relatives, 'he was always a little deaf.' To the last day of his life he bore about with him this troublesome reminder of that furious cannonade.

The Bellerophon returned to England in December of 1805, Franklin carrying with him a certificate from Lieutenant Cumby, who had succeeded to Captain Cooke's command when that gallant officer fell, to the effect that he had performed the duties of signal-midshipman 'with very conspicuous zeal and ability.' His stay in England, however, was destined to be only a short one. The Bellerophon remained at Plymouth no longer than was necessary to refit, and make good the injuries sustained in the action; after which she put to sea again, and for the next eighteen months was employed in cruising between Finisterre and Ushant. Franklin's connection with the famous vessel was soon to come to an end. On October 27, 1807, he begins a letter to one of his sisters with the remark that she will probably be surprised at the new address from which he writes. Two days before he had been drafted from the Bellerophon on to the Bedford, 'commanded by Captain Walker, a smart, active officer, and the ship, I judge, will be a fine ship. Report says she is going foreign, but it must receive some authentication before I can believe it. Indeed, I hope she may.'

His hopes were realised; but the foreign service on which he was despatched turned out to be in disappointing contrast with the exciting experiences of the recent past. He could hardly expect, however, that these would be indefinitely prolonged. The pace, indeed, had been too good to last; and there could not have been many midshipmen in His Majesty's service who had, even in those stirring times, come in for so large a share of adventure in so short a period as had fallen to the lot of John Franklin. It was but six years since he had entered the Navy, a lad of fifteen, and before completing his twenty-first year he had smelt powder in two of the greatest naval battles of our history, explored a continent, suffered shipwreck, and played his part in one of the most singular and, in its almost comical way, most brilliant exploits in the annals of our maritime warfare. Thus his courage and fighting quality had been splendidly tested; he had had his training in seamanship on half the waters of the globe; he had learnt energy and resource in the stern school of disaster; and he had had admirable opportunities for studying navigation and the scientific branches of his profession in general under one of the most capable and painstaking of commanding officers. Fortune had favoured him with many advantages, but to have made the most of them was his own merit. His passionate love of his calling had never abated, and his ambition to perfect himself in all its duties had never flagged. There is no doubt that, thanks in part to his favouring stars, but still more to his own great gifts as a seaman, he had even at this early period of his career already qualified himself for a position of command. By the time he attained his majority he was 'fit to go anywhere and do anything.' But the good luck which had hitherto attended him was now about to bid him adieu for some time to come. Some years were to pass before he again escaped from the dull routine of duty into the field of warlike adventure, and yet a good many more years before he found his way to that special sphere of maritime enterprise in which his true vocation lay.

SERVICE IN TWO HEMISPHERES

1807-1815

IN the concluding chapter of Southey's 'Life of Nelson' the author of that classic biography, by way of illustrating the fame of his hero and the confidence reposed in him by his countrymen, ventures upon the daring hyperbole that 'the destruction of the French and Spanish fleets, and the total prostration of the maritime schemes of Napoleon, hardly appeared to add to our security or strength, for, while Nelson was living to watch the combined squadrons of the enemy, we felt ourselves secure as now, when they were no longer in existence.' Still, after all, 'stone dead hath no fellow', and we can hardly doubt that the annihilation of the French fleet, saddened though our glorious victory was by the death of Nelson, was generally regarded by the English nation as preferable to any other arrangement.

The only class among them who might conceivably have preferred a less complete triumph were the officers of the British Navy. For the last quarter of a century, with few and brief intermissions, they had been as well supplied with opportunities for the practical study of their profession, both in seamanship and in fighting, as any sailors could desire. But Nelson had made such a 'clean job' of it at Trafalgar as to cut off the main source of these opportunities at a stroke. By sweeping the enemies of Great Britain off the face of the sea he left her defenders for many years to come without any efficient training school in naval warfare.

It was Franklin's good fortune to have joined the British Navy in time to share its last five years of glorious activity; had he entered it in 1806 instead of 1801, he would have been condemned to commence, as he was now to continue, his career by undergoing as long or a longer spell of uneventful and monotonous duty. The record of his service afloat from the end of 1807 to the beginning of 1813 is in effect the history of a continuous patrol. The first mission of the Bedford after Franklin joined her as master's mate—a rank, however, from which he was promoted in a couple of months to that of acting lieutenant—was to convoy the fugitive royal family of Portugal, driven from Lisbon by the French invasion, to Rio Janeiro, and for no less than two years the vessel remained stationed in South American waters. She returned to England in the summer of 1810, but for only a very brief period, for the unlucky Walcheren expedition was on foot, and for the next two years she was employed in the not much more exciting duty of blockading Flushing and the entrance of the Texel.

During this period, therefore, the external and public side of the young sailor's life claims but little of a biographer's attention, which may be devoted mainly to such details of his private history and domestic relations as serve to illustrate his personal character. To the Franklin family circle the years which we are now approaching were far from being unmarked by important events. One at least of these events had all the memorable qualities of disaster. Early in the century the commercial affairs of the bank in which Thomas Franklin had embarked much of his own capital, and in which a good deal of his father's savings were also invested, took an unfortunate turn. Thomas became involved in business transactions with one Walker, whose honesty seems to have been open to something more than suspicion; and the consequent pecuniary difficulties in which he found himself entangled led ultimately to the failure of the Spilsby Bank. The shock of this calamity brought the son to the grave in 1807 at the early age of thirty-four, besides hastening the death of his mother a few years later; and it communicated itself in a sufficiently perceptible fashion even to John himself overseas. During the twelve or thirteen years of embarrassment due to these misfortunes, Franklin received no money whatever from home. His scanty pay was all he had to subsist on, and his position in such circumstances must have been one of no little difficulty and discomfort. But the adversity of the family only served to bring into stronger relief the fine qualities of the youngest son. His letters of this period are full of cheerful courage, and testify throughout to a deep filial affection, which was further illustrated in the touching little incident, recorded by his brother-in-law, of his laboriously saving the sum of 5l. out of his midshipman's pittance and remitting it to his parents as his mite of relief to their embarrassed finances.

Most tiresome, perhaps, of all the duties of this monotonous period were those of the squadron detailed to dance attendance upon the exiled Prince Regent of Portugal and his Court. They were as dull as the manœuvres of a blockade, without any of its sustaining hopes of a possible engagement. In a letter to his sister from the Bedford, cruising off Rio Janeiro, in December 1808, one sees how eagerly he caught at any piece of political news from home which might seem to promise an earlier close of his distasteful commission:—

By a corvette from Lisbon despatched purposely to the Prince we learn that the capitulation entered into by General Dalrymple [the Convention of Cintra] is done away, and that a considerable number of the French army are prisoners. This, we hope, may excite the Prince to a desire of return, an event we all anticipate. There, again, I think I hear you say: 'Sailors are always dissatisfied: for instance, my brother and his companions, when living in one of the most luxuriant countries under heaven's canopy, where the least exertion in husbandry or agriculture is overpaid by superabundant return, and whose very bowels contain the richest mines of gold and silver.' This remark as to the characteristic of sailors may be true, yet I assure you in this case it is excusable in those obliged to remain among perhaps the most ungrateful inhabitants of the earth, for whom it is impossible to have the slightest esteem or respect, subject to their bigotry, and observers of their lethargy and indecision, with the greater considerations of a dear, expensive market, and unhealthy crowded towns.

Still, there were occasional diversions, and one such adventure of Franklin's on the island of Madeira, whither he had been sent to reclaim two deserters from the Bedford who had been captured by the Portuguese authorities, is so well and graphically told by him in his despatch to his commanding officer, Captain Mackenzie, that the amusing story had best be given in his own words:—

In obedience to your directions (he writes) I herein state the conduct of Sergeant Joachim Francisco Uramão, who had possession of the two deserters from H.M.S. Bedford, whom you sent me to claim on the 25th August, 1809.

After leaving the ship with the person who gave the information of these men being taken, I went to the captain of the regiment by whom the informer was despatched, and begged he would give orders that the men might be delivered to me. He sent a guide with the necessary instructions for the sergeant, whom [the guide] we took on the boat and proceeded to the spot.

Immediately on entering the village we saw the deserters, apparently unguarded. One was assisting in thatching the sergeant's house, the other drunk. I inquired for the sergeant, but it was some time before I saw him, and then he was just rising from his bed, and drunk also. I desired my interpreter to say those men had deserted from the Bedford, that I was a lieutenant of the ship, and sent to claim them by my captain, having also got the necessary orders for their discharge from his captain. He arose, and very insolently told me I could not have them, that he had an order from his colonel to take them on board, as well as a letter from Captain Mackenzie, and that he meant to carry them the next day. Seeing the facility there was for their escaping in the night, I pointed out that I had full power to give any receipt he wished, and that, having come far from the ship, I did not wish to return without the men. He then grew more violent, and said: 'Your commander may command his ship but not the shore', still persisting in not giving them up to me. Finding all remonstrance vain on my part, I begged the guide to repeat the orders he had received from his captain respecting the release of the two men, and at that repetition he waxed furious, and told him he did not care for the captain, that he ought not to have acquainted the English of the two men being in his possession, and that he would put both the captain and the guide to death.

(Sergeant Joachim Francesco Uramão must evidently have been very drunk indeed.)