a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Andrew Tresholm - Adentures of a Reluctant Gambler Author: E. Phillips Oppenheim * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1300371h.html Language: English Date first posted: Jan 2013 Most recent update: Jan 2013 This eBook was produced by: Roy Glashan Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

The stories in this collection were first published in The Cosmopolitan and syndicated in 1929-1930, with illustrations by Hubert Mathieu, by the Metropolitan Newspaper Service, New York. No bibliographic record of their publication in collected form before the present electronic edition, which was prepared from scanned copies of the stories as they appeared in The Daily Sentinel, Rome, NY, could be found.

The advent of Tresholm, professional gamester, makes Monte Carlo buzz

AT a corner table in the restaurant of the Hotel de Paris, at Monte Carlo, four very distinguished local notabilities were enjoying a midday banquet.

Monsieur Robert, the director of the hotel, was host, white-haired, but vigorous, with keen dark eyes.

On his right sat Monsieur le General de St. Hilaire, from the barracks at Nice, a soldierly-looking person, with fierce gray mustaches, who wore his imposing row of ribbons with the air of one who has earned them.

On the left of his host was Monsieur Desrolles, the Chef de Sûreté of Monaco, a man of mysteries, if ever there was one, tall, dark and hatchet-faced, severe of deportment, as befitted the custodian of many secrets. The fourth man at the table was Gustave Sordel, the leading spirit in the Societé des Bains de Mer, that vast organization responsible primarily for the gambling-rooms, and, in a minor degree, for such less important institutions as the Baths, the Tir aux Pigeons, the Café de Paris, and the golf-course.

The conversation was of food and its glorious corollary, wine. Monsieur Robert was engaged in the pleasing task of making the mouths of his guests water.

Suddenly he broke off with a frown. At his elbow stood Henri of the reception bureau, with a paper in his hand.

"What is this, Henri?" he demanded. "Monsieur Grammont is in his office. You see that I lunch with friends? An occasion, this! Why am I disturbed?"

Henri overweighted with apologies.

"It is Monsieur Grammont who thought that you should see this, without delay," he confided. "It is a thing incomprehensible. One does not know whether to allot the room."

Monsieur Robert produced a horn-rimmed eye-glass, and adjusted it. The allotment of the rooms is no concern of mine," he grumbled.

"You will permit a word of explanation, Monsieur," the young man begged eagerly. "From the Blue Train there arrived, a quarter of an hour ago, this gentleman, Monsieur Andrew Tresholm, an Englishman. He had engaged by correspondence a room looking over the gardens, with bath and small salon. Monsieur Grammont suggested Suite 39. I took him to it upon his arrival.

"He was satisfied with the apartments and the price. All goes well, you perceive. I hand him the papers from the Bureau of Police, and invite him to sign them. He fills in his name—you see it there, His age, thirty-six. His place of birth, a county in England. He arrives at 'profession.a He leaves that blank. Monsieur Desrolles," the young man added, "will remember his recent injunction."

"Certainly," the Chef de Sûreté assented. "We wish in all cases to have this profession stated. There has been a certain slackness in this respect."

Henri bowed his grateful acknowledgments across the table.

"I desire to carry out the official request," he continued, "and I press Monsieur Tresholm to fill in the space. He protests mildly. I insist. He takes up the pen, hesitates. Then he smiles. He is of that type—he smiles to himself. Then he writes. Behold, Monsieur Robert, what he writes."

The great man took the paper into his band and stared at though bewildered.

"'Occupation'," he read out, "'professional gambler'."

"'Professional gambler'," Monsieur Robert repeated, reading from the paper.

They all exchanged bewildered glances.

"A joke perhaps?" the General suggested.

The young man shook his bead.

"This Monsieur Tresholm seemed perfectly serious," he declared. "I asked him if he were in earnest, and he replied, 'Certainly. . . It is, the only profession I have,' he assured me, 'and it keeps me fully occupied.' Those were his words. 'Am I to send this in to the police?' I asked him. 'Certainly,' he assented. 'If they must know my profession, there it is'."

"Here, perhaps, is the end of the world for us," said Monsieur Robert. "A professional gambler, mark you. He may know something. A defeating system may have arrived. Soon you may have to close your doors, Gustave, and I my hotel."

Henri waited patiently. "What am I to do about the gentleman's room, Monsieur Robert?" he inquired.

"Give it to him, by all means," was the prompt reply, "See that Madame Grand adorns it with flowers, that the servants, too, show this eccentric every attention Stop, though! His luggage!"

"He has a greet deal of very superior quality," Henri confided. "There is also a motor-car of expensive make."

"Ma foi! He makes it pay!" Monsieur Robert grunted. "But that is very good. Excellent!"

Henri took his leave, and they all began to talk at once.

"An imbecile without a doubt."

"Perhaps a humorist."

"Stop, stop, my friends!" Gustave Sordel begged. "There have been others who have arrived here with equal confidence. We have heard before—we of the Casino—of the invincible system. Our visitor may be very much in earnest. All I can say is, he is welcome."

The young man from the reception bureau once more approached their table.

"I thought it would interest you, sir," he announced, addressing his chief, "to see this gentleman. He has asked for a corner table for luncheon. He arrives now, in the doorway."

They looked at him with very genuine curiosity. A well-built young; man, of a little over medium height, dressed in gray tweeds. His complexion was sunburnt his eyes blue, his features good, and there was a quizzical curve at the corners of his lips and faint lines by his eyes which might have denoted a humorous outlook.

Gustave Sordel looked at his victim with the eyes of the shearer who has opened his gates to the sheep. "He is of the type," he derided. "They believe in themselves, these young Englishmen with systems. We shall see."

Monsieur Robert grunted once more.

"All very well, Gustave," he declared; "that man is no fool. Discoveries are being made now which have startled the world—things that were declared impossible. Why should it not have arrived at last—the perfect system?"

"The gambler with inspiration," Sordel observed, "sometimes gives temporary inconvenience, but it is upon the world with systems that we thrive. I will drink to the health of this brave man."

Andrew Tresholm, an hour or so later, stood upon the steps of the hotel, looking out upon the gay little scene. A small boy, posted there for that purpose, rushed to the telephone to announce to the chefs de partie and officials of the Casino the impending arrival of this menace to their prosperity. There was a little stir in the hall, and everyone neglected his coffee to lean forward and stare. The Senegalese porter approached with a low bow and a smile.

"The Casino, sir," he announced, pointing to the stucco building across the way.

"I see it" was the somewhat surprised reply. "Darned ugly place, too!"

The man, who spoke only French, let it go at that. Tresholm pointed to a quaint little building perched on the side of the mountain overhead.

"What place is that?" he asked in French.

"The Vistaero Restaurant, sir," the man replied. "The Salles Priveés have been open since two o'clock. The Sporting Club will be open at four."

Tresholm showed no particular sign of interest in either announcement A moment later he descended the steps, and the four very prosperous-looking Frenchmen seated in the lounge rose to watch him.

"The battle commences," Gustave Sordel exclaimed, with a chuckle. But apparently the battle was not going to commence, for Tresholm stepped into a very handsome two-seated car which a chauffeur had just brought round, took his place at the wheel, and, skirting the gardens, mounted the hill.

"Ha, ha!" Monsieur Robert joked. "Your victim escapes, Gustave."

"On the contrary." was the complacent reply, "he mounts to the bank."

In less than half an hour, instead of dealing out his packets of mille notes to the ghouls of the Casino according to plan, Andrew Tresholm was leaning over the crazy balcony of the most picturesquely situated restaurant in Europe looking down at what seemed to be a collection of toy buildings out of a child's play-box. A waiter at his elbow coughed suggestively, and Tresholm ordered coffee. He stretched himself out in a wicker chair and seemed singularly content. The afternoon was warm, and Tresholm, who had ill endured the lack of ventilation in his so-called train de luxe the night before, dosed peacefully in his chair. He awoke to the sound of familiar voices—a woman's musical and pleading, a man's dogged and irritable.

"Can't you understand the common sense of the thing, Norah?" the latter was arguing. "The luck must turn. It's got to turn. Take my case. I've lost for four nights. Tonight, therefore. I am all the more likely to win. What's the good of going home with the paltry sum we have left? Much better try to get the whole lot back."

"Five thousand pounds isn't a paltry sum by any means," the girl protested. "It would make things much more comfortable for us even though you still had to go on at your job."

"Darn the job," was the vicious rejoinder.

Tresholm, who was now quite awake, rose deliberately to his feet and moved across to them.

"Do I, by any chance, come across my young friends of Angoulême once more in some alight trouble? Can I be of any assistance?"

The youth glanced across at him and scowled. The girl swung round.

"Mr. Tresholm!" she exclaimed. "Fancy your being here! Aren't we terrible people, squabbling at the top of our voices in such a beautiful place?"

Tresholm sank into the chair which the young man, with an ungracious greeting, had pushed towards him.

"I seem fated to come up against you two in moments of tribulation," he remarked. "At Angoulême, I think I really was of some assistance. You would never have reached the place but for my chauffeur, who fortunately knows more about cars than I do. A little pathetic you looked, Miss Norah—forgive me, but I never heard your other name—leaning against the wall by the side of that exquisite mountain road, wondering whether any good-natured person would stop and ask if you were in trouble."

She smiled at the recollection. "And you did stop," she reminded him gratefully. "You helped us wonderfully."

"It was my good fortune," he said lightly, but with a faint note of sincerity in his tone. "And this time? What about it? May I be told the trouble again? A discussion about gambling apparently. Well, I know more, about gambling than I do about motor-cars. Let me be your adviser."

"Much obliged. It's no one else's trouble except our own," the young man intervened.

"Or business, I suppose you would like to add," Tresholm observed equably. "Perhaps your sister will be more communicative.

"I told you that night at the hotel at Angoulême of my reputation. I am a meddler in other people's affairs. You young people have been disputing about something. Let me settle the matter for you."

"Why not?" the girl agreed with enthusiasm. "Let me tell him, Jack."

"You can do as you jolly well please," was the surly rejoinder.

The girl leaned across the little round table towards Tresholm. "We told you a little about ourselves at Angoulême during the evening of the day when you had been so kind to us," she reminded him. "We are orphans and we have been living together at Norwich, just on Jack's salary. Our name, by the by, is Bartlett We hadn't a penny in the world, except what Jack earned.

"Then two months ago, quite unexpectedly, a distant relative, whom we had scarcely ever heard of, died and left us five thousand pounds each. We decided to pool the money, have a holiday —Jack's vacation was almost due—and, for once in our lives, have a thoroughly good time."

"A very sound idea," Tresholm murmured.

"The place we both wanted to come to," she went on, "was Monte Carlo. We bought a little motor-car—you know something about that—and we reached here a few days ago. It was lots of fun, but, alas, ever since we arrived Jack and I have disagreed. His point of view——"

"I'll tell him that myself." her brother interrupted. "Ten thousand pounds our legacy was—nine thousand we reckoned, when our holiday's paid for, and the car. Well, supposing I invested it, what would it mean? Four hundred and fifty a year. Neither one thing nor the other. It's just about what I'm earning. It wouldn't have helped me to escape, I should have had to go on just the same, and I hate the work like poison."

"Four hundred and fifty a year would have made life very much easier for us, even though you had to go on working," she remarked wistfully.

"Thinking of yourself as usual," he growled. "Well, anyhow, you agreed at first."

"Agreed to what?" Tresholm inquired.

"To taking our chance of making a bit while we were here," he explained. "We decided to risk a couple of thousand pounds and see if we could make enough to live quietly somewhere in the country, where there was golf and a bit of shooting."

"It wasn't my idea," she ventured.

"Of course, it wasn't," he scoffed. "You're like all women. You're too frightened of losing to make a good sportsman."

"Well, we have lost" she rejoined drily—"not two thousand but four."

"That seems unfortunate," was Tresholm's grave comment "What is the present subject of your dispute?"

"Simply this," the young man confided. "We have spent or shall have spent, by the time we get home, a thousand pounds of the legacy. We have lost at the tables four thousand, and sold the little car we bought for half what we gave for it We have five thousand left Norah wants me to promise not to go into the Casino again, and to leave for home at once with five thousand pounds in the bank. I want to go, neck or nothing—win back at least our five thousand—perhaps a good bit more. The luck must turn."

"Quite so," Tresholm agreed. "There's a certain amount of reason in what your brother says, Miss Norah."

She looked at him almost in horror.

"You don't mean to say that you're going to advise him to risk the rest of our legacy!" she exclaimed.

Tresholm made no direct reply. He passed around his case and lighted a cigarette himself.

"Well," he pronounced, "I have a certain amount of sympathy for your brother's point of view. If I were in his position and had lost as much as you say, I think I should want a shot at getting some of it back, but," he added, checking the young man's exclamation of delight and the girls little cry of disappointment with the same gesture, "I should want to know that the odds were level"

"Roulette's a fair enough game," the young man protested. "One chance in thirty five against you—and zero, of course."

"You may call that fair," Tresholm said calmly; "I don't. I am assuming that with your small capital you're backing the numbers. Very well. The bank has the pull on you the whole of the time to the extent of five or six percent If you play chemin de fer, the cagnotte amounts to about the same thing.

"I am with you in spirit, my young friend, but gambling at Monte Carlo isn't what I call gambling at all. You're fighting a man of equal ability a stone heavier than yourself. It can't be done. It's automatic. You must lose."

"That's what I say," the girl declared triumphantly. "We're simply foolish to dream of throwing away the last of our money."

"But people do win," her brother insisted There's that Hungarian who won half a million francs the night before last."

"The Casino takes pretty good care to advertise it when anything of that sort happens," Tresholm pointed out. "He'll probably be in again tonight and lose the lot, and more besides. Now listen to me, Bartlett" he went on. "I'm not against you in spirit I'm against you in this particular proposal because you want to take on an impossibility.

"The people who win here are just the people who play to amuse themselves, and who go away when they've had their fun. People in your position, with a few thousand pounds left over from a legacy and nothing else to fall back upon in the world, are the people who inevitably lose."

The young man thrust his hands into his trousers pockets.

"It's no good trying to be scientific in gambling," he said. "If you want to have a plunge, you always must have a bit up against you, of course. What's it matter so long as you win? I never mind backing a horse at odds on, so long as it's a certainty."

"There is such a thing as fair gambling," Tresholm pointed out. "I'll toss you for your five thousand pounds, if you like. That's a level affair—no cagnotte, no zero. You can choose the coin."

The girl gave a little cry. Her brother gasped.

"You're not serious?" he exclaimed.

"Mr. Tresholm!" she remonstrated.

"I'm perfectly serious," he assured them both. "You seem to think that I know nothing about gambling. On the contrary, I am described in the police records of this principality as a professional gambler. I must live up to my reputation. I will toss you for five thousand pounds. Shall I send for a coin?"

"No!" the girl almost shrieked.

Tresholm shrugged his shoulders.

"Very well," he acquiesced. "You would like to prolong the agony. Dine with me, both of you, tonight at the Hotel de Paris at half past eight We will either toss, or play any game you like where the odds are level, for whatever sum you like up to five thousand pounds."

The girl looked at him reproachfully through a mist of tears. Her brother was exuberant.

"You're a sportsman," he declared. "I wanted to dine at the Paris once more before we left. We'll be there at half past eight."

Gustave Sordel paid a special visit to the hotel just before dinner-time that evening. He encountered Monsieur Robert in the hall.

"But what has arrived!" he exclaimed. "All the afternoon my chefs have been on the qui vive. I have reinforced every table to the extent of a hundred thousand francs. I arranged for a high table at chemin de fer, and, if Monsieur Tresholm had wished to take a bank at baccarat tonight, it could have been managed. Yet behold the strange thing which has arrived. He has not as yet taken out his ticket—"

"In the Sporting Hub, perhaps?" Monsieur Robert suggested. "Three times I have sent there. No one of his name has applied for a card."

"This affair gives one to think," Monsieur Robert admitted, "At present he dines with a young Englishman and his sister—a couple bien distingué, but poor. They left here last week for a cheaper hotel. Of what interest can they be to him?"

Sordel shrugged his shoulders. "After all." he pointed out "even a professional gambler must have his moments. He waits far the night without a doubt."

Meanwhile, in the restaurant, Tresholm, to all appearance, was very much enjoying his dinner. Bartlett was excited and talkative. Norah, on the other hand, was very quiet. She ate and drank little, and her manner, especially towards her host, was reserved, not to say cold.

"Your sister, Bartlett" the latter confided, "is displeased with me. I wonder whether I might ask why."

"Because you have taken his side against me," she said, looking at him with a smoldering anger in her eyes. "You are encouraging him to gamble with that last five thousand pounds. I hoped so much that you would have been on my side, that you would have told him to keep that money, for both our sakes, and not to enter the Casino again."

"And if I had told him that" Tresholm asked calmly, "would it have made any difference?"

She reflected for a moment. "Perhaps it would not," she admitted. "He is very self-willed. He would probably have had his own way, and yet, somehow or other, I am sorry that it should have been you who encouraged this."

"I don't think that you are quite just to blame me," he complained. "You must realize that nothing I could have said would have made the slightest difference. You know that you yourself have used all your persuasions. Your brother would have lost every penny in the Casino, if I had not offered him a saner chance of gambling with me."

"I can't explain," she sighed. "I am just disappointed."

They left the table, crossed the lounge and entered the elevator. In the corridor Bartlett stopped to speak to an acquaintance.

The girl suddenly turned to her companion.

"Mr. Tresholm," she begged, "don't do this. Let him lose his money in the Casino, if he must I don't like the idea of you two sitting down to play against one another. I don't like it There's something horrible about it"

"Don't you think," he asked, "that, if your brother must throw his money away, I might as well have it as anybody else?"

"Do you mean—do you really mean that you are what you said?"

"I am afraid there is a certain amount of truth in what I told you," he acknowledged. "If you go to the Chef de Sûreté here in Monaco, he will show you my papers."

"Then I think it is all very terrible," she pronounced sadly. "I am very sorry that we ever came to Monte Carlo."

"Now for the terms," Tresholm said, as he and Bartlett seated themselves at a small table. "First of all, here are two tickets for the Blue Train tomorrow. It is understood that, whether you win my money or I win yours, you make use of them."

"Right-o!" the young man agreed, pocketing the yellow slips.

"I require more than a casual acceptance of that proposal," Tresholm persisted. "I require your word of honor."

"That's all right" the other acquiesced. "I promise upon my honor."

"And I am your witness," Norah intervened gravely.

"Furthermore, whether you win or lose," Tresholm continued, "you must promise not to return within twelve months."

"Agreed. Come along. Let's start"

"The game I leave entirely to you," Tresholm announced. "There are, as you see, four new packs of cards. I will cut you highest or lowest to win, whichever you like, or I will play you two-handed poker, or piquet, or any other game you prefer."

There was a sudden gleam in the young man's eyes. "Piquet?" he repeated. "You play piquet?"

"Rather well," Tresholm warned him. "I should advise you to choose something else."

Bartlett laughed confidently. "Piquet's good enough for me," he declared. "I used to play it with my old governor every night Let's get on with it," he added, moistening his dry lips. "A hundred pounds a time, eh?"

"Whatever you like," was the reply.

It was midnight before the matter was concluded. Bartlett, white and distraught, with a dangerous, almost lunatic, gleam in his eyes, was pacing the room excitedly. Norah, unexpectedly calm, was still seated in the chair from which she had watched the gambling with changeless expression. Tresholm remained at the table. Before him lay a check for five thousand pounds which the young man had just signed.

"Ready, Jack?" she asked at last.

"I suppose so," he growled. "Come along."

Tresholm rose. "You've had a fair deal with level odds for your money, haven't you?" he asked his late opponent.

"I'm not complaining," was, the broken reply. "I suppose it's no use asking you to lend me a hundred just to have one shot at the Sporting Club?"

"Not the least use in the world," Tresholm refused. "The hundred pounds would go just where the rest of your money has gone. There are some of us who are made to win at games of chance; others to lose. You are one of the predestined losers. If you take my advice, you will never again, so long as you live, indulge in any game of chance for money." He opened the door. The girl passed out slim and dignified, without a glance in his direction.

"Good night Miss Bartlett" he ventured.

"Good night, Mr. Tresholm," she replied. "I congratulate you upon your profitable evening."

With that they both disappeared.

Tresholm returned to his place at the table, playing idly with the cards.

The Blue Train, disturbingly early upon its return journey, just as it is usually outrageously late upon its arrival, came groaning round the bend from Mentone, snorting and puffing into the Monte Carlo station. Norah settled down sadly in her compartment while her brother made his way to the restaurant car to secure seats for dinner.

Then, glancing idly out of the window, she suddenly gave a little gasp. Very deliberately along the platform came Tresholm, calm and undisturbed. Behind him was a small boy carrying an enormous bouquet of roses.

She shrank beck in her place. Anything rather than see him! Before she could decide upon any means of escape, however, the roses were on the seat by her side, and Tresholm was standing bare-headed before her.

"A little farewell offering for you. Miss Bartlett which you must accept, and a farewell note here for you to read as soon as the train has started," he added, handing her a letter. "Will you shake hands?"

In her moment of indecision she forgot and she looked up at him. Directly her eyes met his, clear, gray and somehow compelling, she gave in. Her fingers rested for a moment in his. Then he raised them and brushed them with his lips.

"I am glad," he said gratefully, "that you did not carry your resentment too far. You will accept the roses, I hope, as an inadequate peace-offering, and think of me as kindly as you can."

Then he was gone, and it was not until after the train had passed through the first of the two tunnels that she remembered the note. She tore open the envelop and read:

Dear Lady of Angoulême,

I very much fear that your perceptions were keener than your brother's last night and that you realised the fact that I was playing with marked cards—part of the equipment of the professional gambler. The unexpected luxury of a qualm of conscience has, however, seized me, and I return your brother's check for his imaginary loss.

I still hold him, however, to the conditions of our bargain, and, if you will accept the advice of such an unprincipled person, keep him away from gambling in any shape or form, even though the odds should seem level. There are some men who are born winners. I am one of them. There are others who are born losers. Your brother is one of those.

Fate, alas, deals out other favors to the latter class, which she denies to the former.

Which is why I must sign myself,

Unhappily yours,

Andrew Tresholm."

Fragments of a torn check fluttered across the compartment. Even in her dazed state, even under the spell of that great throbbing joy with which she waited for her brother's return, there crept into her mind a faint, wonderful doubt— a doubt which sometimes, when she looked backwards, seemed to color those hours of agony with a little halo of romance. Was it altogether by chance, she wondered, in those moments of reflection, that the only possible means by which her brother could have been induced to return to England with that five thousand pounds were precisely those which Tresholm had employed?

In his sitting-room, Tresholm found the four packs of cards neatly stacked upon the mantelpiece. He rang the bell for the waiter.

"You might return those," he begged, "to whomever you borrowed them from."

The waiter collected them with a smile, also the fifty-franc note which Tresholm passed him.

"I borrowed them from one of the clerks in the office, Monsieur," he confided. "I trust that Monsieur had fortune,"

Tresholm nodded slightly, but without his usual smile.

"Yes, I am generally lucky," he confessed.

Tresholm took a Gambler's chance,

but the stakes were temptingly high and he couldn't resist

TRESHOLM brought his car to a standstill under a close-leafed magnolia tree, jammed on the brakes, and lighted a cigarette. For six miles, ascending gradually from the sea-level, he had climbed the mountainous road until he had reached the fruitful plateau which embosoms the the slopes of the Lesser Alps. Blue and cold, the landscape lay below him, gray here and there, with the shimmer of turning olive leaves, the vineyards and meadows like little squares of patchwork, the flower fields daubs of brilliant color, the river winding its way amongst them, a glittering thread of silver. In front, barely a mile distant, was one of the old hill towns, the houses of which might well have been carved out of the living rock. The air around him was pleasantly brisk. In the majestic distance, the snow still lay upon the mountains.

His resting-place was peaceful and well-chosen. On his right was a humble French domain, a trim white house, with red roof and green shutters, separated from the road by a carefully tended vineyard, an orchard of orange trees wandering up to a plantation of pines behind. A very pleasant, sunny spot it seemed, cut off from the world by the ravine, on the farther summit of which was the old town and the precipitous way by which one climbed from the great thoroughfares below. Scarcely a human being in sight, scarcely a toiler in the fields.

An imaginary solitude. Tresholm started as he realised the fixed stare of a gaunt figure in blue jeans, standing only a few feet away from him in the vineyard, partially concealed by a scrubby hawthorn hedge. It was more than the ordinary scrutiny of the curious peasant; in fact, it became clear to Tresholm during those first few seconds that the man was not a peasant at all He was tall and thin, and there was something fine-cut about his features. The brown fingers which grasped the pruning-knife were well-formed and shapely, and as he returned that intense gaze, a queer wave of remembrance swept into Tresholm's brain. Like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, those scraps of memory mocked him: the bleak wind-swept plain; the wilderness, dotted all over with a maze of tin huts and framework buildings; the road of a great city with its myriads of blinding lights; a room high up in a huge official building; the thunder of tram, below; the ceaseless movement of multitudes crawling like ants along the pavements.

Perhaps the two men reached the end of that unwinding coil of memory at the same moment, for the watcher in the vineyard turned abruptly away and strode off towards the house. With a muttered exclamation, Tresholm pressed the starting-button of his car, turned in at the rude gateway, drove up the rock-strewn approach to the house, and pulled up in its shadow. He descended, and waited for the man, who was still climbing from below.

"You're Dows, aren't you?" he greeted him— Jasper Dows, Naval Intelligence Department at Washington? Let me see, how many years ago?... Who cares?"

"I am Jasper Dows, all right," he admitted, "but Washington Naval Intelligence Department—I don't know what you're talking about. All gone! I'm a small landed proprietor of Les Tourettes. Eighty acres—you can see the lot, I remember you, though. You're Tresholm. Blast you!"

"Why blast me?" his visitor remonstrated.

Jasper Dows laughed bitterly and stood for a moment in silence. When he spoke again, there was a change in his manner.

Some of the resentment had gone.

"Not your fault, of course, Tresholm," he acknowledged. "Come in and drink a bottle of wine. It's long enough since I talked my own language."

They passed into a small sitting-room, in which were some quaint pieces of old Provençal furniture, a mass of flowers in a rude china basin, but with carpetless floor and empty walls, poverty lurking even in its cleanliness. A woman rose hastily from a chair in a corner with its back to the window—a woman far too attractive for her surroundings, evidently English or American, a little startled at the sight of an unexpected visitor.

"A gentleman whom I used to know, Sara," the master of the house announced. "My wife, Tresholm. We want a bottle of last year's vintage, dear, and a couple of glasses."

She greeted Tresholm pleasantly, left them for a few minutes, and returned with a bottle of wine and two glasses upon a tray.

"The most brutal thing I ever did, to bring her over here," Jasper Dows acknowledged, as, with a word of excuse, she hurried away again. "She would come, though. She's that sort of woman."

"But what was the trouble?" Tresholm asked gravely. "When I left Washington—"

"You knew nothing about it, of course, the other interrupted. "The trouble was disgrace and ruin." "That's rather hard to believe."

"There were a few men in my department who thought so at the time. They changed their minds, though, and out I went. I got the sack, Tresholm. Cashiered—chucked out of the service. Do you know who brought it about? Of course you don't. I'll tell you. Here's one of them." He picked up a copy of the Nice Éclaireur, which had been lying upon the table, and read a paragraph from the English and American news: class="newspaper" "Considerable excitement has been caused in the Sporting Club during this week by the very spirited gambling of an American millionaire, Mr. Josh Chandler, of New York. We understand that he was successful in breaking the bank twice in one evening." "That's one of them," Jasper Dows continued, throwing the paper down. "Josh Chandler was one, and you were the other."

"Are you serious?" Tresholm expostulated, wondering for the moment whether the man had lost his wits.

"Sit down, drink your wine, and listen. You are the one man in the world to whom I can tell the story."

Tresholm listened, and it was late in the afternoon, with the sun sinking over the Esterels, when he glided down again from the farm among the mountains to take his place in the stream of vehicles panting along the lighted way.

Gustave Sordel, being at a loose end the following morning, crossed the road from the Casino about a quarter of an hour before luncheon, and took an aperitif with his friend Monsieur Robert, the director of the hotel. They found seats in a retired corner of the lounge.

"The doors of the Casino are still open?" the latter demanded, in gentle badinage.

"And likely to remain open, so far as regards this eccentric of yours," was the good-humored reply. "Figure to yourself, my dear friend, this Monsieur Tresholm. He rests here within a stone's throw of the Casino, he inscribes himself a professional gambler, and he has not yet taken out his card of admission. What does he do with himself?"

"I will tell you what he did yesterday," Monsieur Robert volunteered, "He left his chauffeur, and he drove out into the country. When he returned, he dined alone—the dinner of an epicure, mind you, and drank with it half a bottle of of my finest Burgundy." "And afterwards?" "He went to bed."

"Imbecile—for what does he wait?"

"For money, perhaps. One cannot storm your stronghold, my dear Gustave, without the sinews of war."

The director of the Casino moved a little nearer to his friend.

"As to that," he confided, lowering his voice," I can tell you something. Have no fear for your hotel bill. Yesterday morning—it must have been before our friend started for his motor trip—I was at the bank, and I—I myself, mind you, was compelled to wait. An important client was with the manager.

"When he came out from the office it was this Monsieur Tresholm. They were around him as though he were a Rothschild. The manager even escorted him to the door whilst I waited."

Monsieur Robert was interested. "You ventured upon an enquiry, perhaps?"

"Up there they are discreet," was the cautious reply. Monsieur Blunt, as you know, has little to say. In his position, he is wise. He brushed aside all my interrogations. 'Monsieur Tresholm,' he whispered in my ear, 'comes to us with excellent recommendations from the highest quarters.' What more than that can be said of any stranger? Yet that is the man who announces himself as a professional gambler, and in four days he has not crossed the threshold of the Casino or of the Sporting Club."

They spoke of other things, and as they talked Tresholm himself entered. He was in tennis togs, carrying a racket under his arm, and instead of passing directly across the lounge, he made a detour towards the restaurant which led him past the divan where the two men were seated. The hotel director greeted him cordially.

"Monsieur was successful in finding a game this morning?" he inquired.

"I found just the game I hoped for," Tresholm confided.

"Excellent! And your apartments, they are comfortable?there is nothing one can do?"

"Nothing whatever," was the courteous assurance. "Everything is as one expects to find it at the Hotel de Paris? perfect."

He would have moved on, but his interlocutor detained him.

"Let me present my friend, Monsieur Sordel," he begged. "It is Monsieur Tresholm, you understand," he added, turning to his companion, "who has perpetrated this jest upon the Chef de Sûreté. I present, you understand, one professional to another. It is a matter of attack and defense. Monsieur Sordel directs the ?Casino."

Tresholm smiled as he shook hands. "Your friend," he remarked, "is a man of many affairs."

"As yet," Sordel rejoined. "I have not had to number yon amongst my responsibilities."

"That will come, without a doubt," Tresholm predicted. "When I first arrived, I had some young friends to entertain. Yesterday the weather was so perfect that I had a fancy for the country. Today, who knows?"

He passed on with a nod of farewell, and the two men exchanged significant glances.

"It may be today, then," Gustave Sordel observed.

Tresholm paused to interview a maître d'hôtel and order luncheon for two in half an hour, after which he ascended to his room, took a shower-bath and changed his clothes. He descended in time to welcome his guest—an American, Chandler by name, his recent opponent at tennis, and a man apparently of about his own age. There was a marked difference between the two, however as they strolled together into the restaurant—Tresholm lean, bright-eyed and sunburnt, to all appearances as hard as nails, and in perfect condition; his companion, built on stockier lines, more than a little fleshy, carefully dressed and groomed, but with the air of one to whom the night pleasures of the principality had made their successful appeal.

"Lucky to have come across you this morning," he remarked, as they took their places. "Don't know that I should have got a game at all. Fellows here seem sort of cliquish. Don't fancy taking a stranger in if they can help it."

"I dare say they make up their sets beforehand," Tresholm suggested tactfully.

"Maybe. Guess I'd better let a few of them know who I am. My old dad left twenty million of the best. You bet I don't have to wait long for a game at any club over on the other aide."

"Twenty million dollars is a great deal of money." "Piled it up during the war, the old man did," his son confided.

"You were over on this side?"

"Didn't get the chance. I was in the navy, but they wanted me in Washington. Seaplane stuff, most of the time. Gosh, they kept me at it, too!"

His first high-ball was beginning to loosen the young man's tongue.

He was filled with placid satisfaction with himself and his surroundings.

"Say, I ought not to have let you whip me like that this morning," he observed. "Six?two, six?one. Not often I get it in the neck like that."

"A little lazy round the back line, weren't you? A late night?"

"Say, if anyone can tell me how to get to bed early in this little burg, he's a winner with me," Chandler declared gloomily.

"I was playing chemie until five this morning."

"I rather thought roulette was your game," Tresholm remarked. "Didn't I see that you had a big win yesterday or the day before?"

"A hundred and thirty-eight thousand of the best, I skun em," the young man boasted. "I had them all scared. They don't understand having anyone up against them who can afford to lose just as much as he wants to. It don't matter a snap of the fingers to me whether I win or not. That's where I've got them cold.

"A hundred and thirty-eight thousand," Tresholm repeated softly, thinking for a moment of that poverty-stricken farm up in the mountains. "That's a great deal of money, Mr. Chandler."

"I guess it seems so over here," was the complacent reply. "See that bulge in my pocket? There it is, and they can have the lot back this evening, if they can get it."

Conversation languished for a time and then continued upon somewhat formal lines. Towards the close of their meal, the American, who had been scrutinizing his host closely, asked him a abrupt question.

"Say, haven't we met somewhere before, Mr. Tresholm? Something about you seems kind of familiar to me ever since you came up and asked me for a game."

"I shouldn't be surprised," was the somewhat vague acknowledgment. It's a small world, you know."

"Ever been in the States?"

"Not lately. I dare say we come across each other in Paris or somewhere," Tresholm observed. "I wander about a good deal"

"Same here. I don't have to do any work, and over this side's good enough You Europeans know how to live the life. Say, that's a bully two-seater of yours, Mr. Tresholm."

"Glad you like it. How about a little run into the country this afternoon?"

"It will keep me awake at any rate," the young man agreed.

At Nice, Chandler, who had dropped off to sleep before they had reached Beaulieu, woke up and demanded a highball. They stopped at the Negresco bar where he relapsed into an easy chair with a sigh of content.

"Some car of yours," he admitted; "but I guess we've come about far enough, eh? This seems a pretty good spot to me."

"Only a little farther on," Tresholm begged. "I want to call on a man I used to know, if you don't mind. We can look in here again coming back, if you want to."

Chandler's acquiescence was a little ungracious, but he suffered himself presently to be escorted out to the car, where he sank back among the cushions and promptly went to sleep. Tresholm drove smoothly on until they were just short of Cagnes, when he turned off the main road and crept upwards towards the ridge which encircled the lesser mountains.

Outside the little farmhouse, he pulled up and shook his companion.

"Come along in and see my pal," he invited.

Chandler sat up, blinking, and looked around him. "Where are we?" he demanded.

"Somewhere between Cagnes and Vence. We have a visit to pay."

Chandler descended grumpily, and Tresholm, opening the unfastened front door, ushered him into the bare sitting-room. The unwilling guest looked about him distastefully.

"Don't seem to me as though we'd get a drink here," he decided. "I guess I'll leave you to your friend and wait outside."

Then Tresholm did an unexpected thing. He locked the door, placed the key in his pocket and pointed to a hard wooden chair.

"You'll sit there, and wait until we've finished a little matter of business," he directed.

Josh Chandler was dumfounded. He stared first at the man who had suddenly abandoned his role of courteous if somewhat silent host and addressed these threatening words to him, and then at the no-less-alarming figure in blue overalls who had pushed aside the curtains and appeared upon the threshold of an inner room. As he stared, his memory also reasserted itself. His sleepy, drink-sodden brain cleared beneath the shock.

"Good Heavens!" he exclaimed. "It's Jasper Dows—and"?his eyes traveled fearfully towards Tresholm—"and the Englishman!"

There was a brief silence. His gaze wandered from the worn face of his former associate back to Tresholm, cold, supercilious, tight-lipped, hard yet flexible as a piece of steel.

"What's this— a hold-up?" he demanded. "I'm getting out of here."

"You'll stay just where you are," Tresholm enjoined calmly.

"Who's going to stop me?"

"I am. You can have a rough-house if you want it, Chandler. Oh, yes, I know you're a strong fellow, but I am a boxer. You wouldn't live with me for thirty seconds. No good patting your hip pocket either. I felt you over in the car. You'd better listen quietly,"

"What the—"

"Oh, do be quiet," Tresholm begged a little wearily. "It isn't any use. You're up against it. You've recognised me. I know the truth as between you and Jasper Dows. You'd better look upon me as your protector. I think if I left you two alone, he'd kill you."

"Do you think I'm afraid?"

"You ought to be if you're not," was the quiet rejoinder. "If you think a thrashing will help you to listen more patiently, come outside and have it. If not, get back to your chair."

"I'm right enough here. Get on with it"

"We won't specify the actual date," Tresholm began, "but some ten or eleven years ago, not being in the financial position to which your father's millions have since boosted you, you sold copies of various plans of proposed new American seaplanes to the secret service agent of another country who happened to be in Washington."

Chandler looked around the room as though to be sure that there were no other auditors but that stern, haggard figure standing between the parted curtains.

"I sold them to you," he said hoarsely. "I've been wondering—I was wondering all luncheon-time where I'd seen you before."

"Quite right," Tresholm acknowledged.

"You sold them to me, and I paid you a very handsome sum of money for them. Unfortunately, the fact that the plans had been copied leaked out, and the affair was traced either to Jasper Dows, or to you. As is usually the case, the innocent man got it in the neck, and you, the guilty one, escaped.

"Jasper Dows was considered lucky to be cashiered. His father cut off his allowance and died without leaving him a penny. His friends gave him the cold shoulder, and here he is, working himself to death, earning just enough to live on. By rights, you ought to be in his place, Chandler. I know the person from whom I bought the plans, don't I?"

The accused man leaned forward. His eyes were full of a very malicious light.

"You know all right, you confounded spy," he agreed, "but you can't tell. Supposing I did sell them to you, what about it? You can't open your mouth, and I'm not going to. There isn't another soul in the world knows the truth—and you can't tell."

Tresholm eyed him for a moment meditatively. "What a foul swine you are," he remarked, in bitter disgust.

"However, either you forget one trifling circumstance, or things may be different in your country. We have a statute of limitations—ten years it is fixed at in my department The ten years are up. Added to this, my papers went in some time ago. I am a free man. Chandler. How do you like that?"

Apparently, Chandler didn't like it at all.

"What do you mean?" he exclaimed. "Is this blackmail?"

Tresholm inclined his head very slightly. I alway said that you were not quite a fool, Chandler," he confided. "It is blackmail, and you are the victim."

The young man was dazed. Tresholm pointed authoritatively to his chair. He sat down.

"Let us consider the matter now from a business point of view," he continued "Jasper Daws, you had better join us."

"I'll stay where I am," was the low, passionate reply. "If I'm in the same room I might kill him."

Tresholm nodded sympathetically.

"Quite so," he assented. "Well, I'll proceed on your behalf. Our friend Jasper Dows, Chandler, would have inherited at least half a million from his father, if it hadn't been for your machinations. Very well, we'll start with that. I think you told me on the tennis-courts this morning, and at luncheon today?several times, if I remember rightly,?that the old man, as you called him, had left you twenty millions. We'll take half a million away from you. Half a million dollars, Chandler?not a great sum for the ruin of a man's life."

"What else?" was the gruff demand.

"Several little things. First of all, you won, as all Monte Carlo knows, a hundred and thirty-eight thousand francs last night I can see the mille notes bulging in your pockets. You have even confided to me the fact of their presence there. You will hand them over to Jasper Dows for immediate expenses."

"What else?"

"Ah, now we come to the point. Your confession of having sold the plans, and of Jasper Dows' innocence, is drawn up here. Your signature will be witnessed by the American consul, who is now walking with Mrs. Dows in the garden— but?listen to me calmly—this is where my friend Jasper Dows is inclined to be generous. He has, as it happens, no desire to return permanently to America. Your confession, therefore, will only be used to insure the clearing of his name.

"That is to say, it will simply be placed before the authorities in Washington. His rank in the service will be restored, and that is all he desires. You have nothing to lose in this direction, for yon held no commission. You were simply a shirker, placed in the department by influence to escape active service."

"Ill have nothing to do with this business!" Chandler shouted.

"Wait!" Tresholm begged, holding out his band. "Consider for a moment what will happen if you agree. You will have made such atonement as is possible to Jasper Dows, even though it may have been under compulsion. For the rest of his life he will enjoy the comfort of which you have deprived him for the last ten years, and his honor will be re-established. Consider what a relief this will be to that sensitive conscience of yours, Chandler."

"Blast you!" the other snarled.

"On the other band," Tresholm went on, unmoved, "if you refuse, being a free-lance in life and having a fancy for my friend Jasper Dows here, and his wife, I shall take the trouble to pay a visit to Washington myself, where I still have many friends. I shall place the facts before the authorities, and I shall place them equally before every one of those enterprising and brilliant young journalists who are apt to gather around when any social scandal or the rumor of it arises. In other words, Chandler, I'll emblazon your name on the roll of disgrace from New York to San Francisco, and never again, so long as you live, will you be able to put your foot upon the deck of a westward-bound steamer."

Chandler unbuttoned his cost threw the great pile of mille notes upon the table, produced his check-book and drew his chair up to the table.

"I'm beat" he decided.

"I always said that you were not quite a fool," Tresholm acknowledged pleasantly. "Dows, you might call in Mr. Wisely."

At Nice, on their homeward journey, Tresholm stopped outside a garage.

"I have brought you so far, much against my inclination," he said to his companion. "You can hire a car here. Get out and look after yourself."

Chandler slouched surlily off, and Tresholm drove on to Monte Carlo.

They sat together in the sunshine outside the Café de Paris the next morning—Jasper Dows and Tresholm. The former had just descended the hill from the bank.

"So it was all right, eh?" his companion asked.

Jasper Dows had the air of a man who had been living in the darkness for years. Even his tone, when he spoke, was the tone of one half dazed.

"They didn't even hesitate," he announced wonderingly. "The money was there already to my credit—five hundred thousand dollars in French francs. I could have drawn the lot if I'd liked."

"Good! Where's the wife?"

Dows' face suddenly softened. An almost beatific smile parted his lips. One might have fancied that his eyes were a little dim.

"She's shopping," he confided. "I just pushed a handful of mille notes into her bag, and she's gone off with them like a child into toy-land. After tea years' poverty, Tresholm!. Never a hundred francs to spend. Making and remaking old clothes . . . . And now she's shopping!"

Tresholm Summoned a waiter and busied himself with the lighting of a cigarette. Jasper Dows was feeling his way back to life again.

"There was one thing yesterday, Tresholm." he said, "that puzzled me. Our Secret Service isn't quits the same as yours, of course, but—that statute of limitations now. I don't quite get that."

Tresholm leaned back in his chair and looked up at the blue sky.

"Chandler's just the sort of idiot who would swallow such a story," he murmured. "You and I know well enough, Dows, that never so long as I lived could I have opened my lips."

"It was just a bluff then?"

Tresholm nodded. "It seemed the only way of dealing with him—just a gamble as to whether he swallowed it or not. I like a gamble sometimes. Rather in my line, as it happens," he added, pausing to wave his hand to Gustave Sordel, who was passing.

First a hold-up and a crooked game of

cards—

A strange evening, but what followed was stranger

TRESHOLM stood upon the top-most step of the Hotel de Paris at Monte Carlo, looking doubtfully out at a not very exhilarating prospect A low-lying bank of clouds obscured the panoramic hills, the pavements were rain-splashed, there were little puddles in the road.

The chairs and tables at the Café de Paris opposite were piled up together, The commissionnaire outside the Casino awaited arrivals with a huge umbrella already unfurled. The Senegalese head porter, standing by Tresholm's side, showed all his white teeth in a smile of expectancy.

"A day for the Casino, Monsieur," he hazarded.

Tresholm gazed meditatively across the Place at the great stucco-fronted building, and the very fact of his hesitation seemed to create a little wave of excitement in his immediate neighborhood. The man who worked the lift to the underground passage held open the gates hopefully. A boy in buttons prepared for a dash across the Place to announce the coming event.

By intuition, or some invisible means the rumor of this long-expected descent upon the stronghold of gambling began to spread. The chief maître d'hôtel of the restaurant followed by two of his subordinates, strolled up as though casually to pay respects to an excellent client.

"A day to remain indoors, I fear, Monsieur," he ventured. "One might amuse oneself at the tables for a time."

Tresholm nodded absently. As yet he made no move. Several people in the lounge prepared to follow him if he should cross the square.

A self-declared professional gambler who had been in Monte Carlo for at least a week, and had not once entered the gambling rooms! The thing was amazing. This morning, however, what else could happen? There was the Casino, with its doors hospitably open, through which was passing all the time a little stream of the world in mackintoshes. The thing seemed predestined.

And then a thin shaft of silver appeared from some partially hidden place and crept down from skywards. The gray puddles flashed like molten silver. The waiters from the Café de Paris came tentatively out and, after a look around, began to rearrange the chairs and tables.

The shaft of sunlight grew broader with the moments. Up in the sky a patch of blue was unexpectedly visible. The of rain for one moment became diamonds and then ceased. The clouds were parting like the drawing of a curtain in a theater.

And then, unmistakably, sunshine— sunshine smiling down upon the Place as though to explain that those leaden hours had been just a joke. The sun shone clearly, its tender warmth chasing all the damp out of the moist atmosphere. Monte Carlo was itself again. Tresholm threw away his cigarette.

"Good!" he exclaimed to his Senegalese friend in the blue uniform. "I shall go out to Cagnes and play golf."

The man tried to conceal his disappointment as he summoned the car. The lift attendant turned away in disgust. The maître d'hôtel followed his example. The expectant little crowd in the lounge resumed their places, and Tresholm stepped into his coupé and disappeared.

Later in the day, it was to mean something to him that the sunshine should have appeared at that particular moment.

Tresholm put on his brakes, stopping the car at once, while his headlights disclosed the man standing in the middle of the road with uplifted arms. After a round of golf, he was in an excellent humor and prepared to play the good Samaritan to anyone. A broken-down car, perhaps? Someone desiring a lift? He leaned forward to scrutinize the man who had hailed him.

"Monsieur will descend," a hoarse voice insisted.

Tresholm was utterly taken by surprise and uncertain, for the moment, how to act. With his hand upon the door of the car stood a person of most ruffianly appearance, wearing a narrow black mask and holding an ugly-looking automatic. Not only that but a second man had appeared out of the shadows and was hanging on the other door.

It is probable that, if Tresholm had not been dreaming and required several seconds to realize the position, his impulse to make a dash for it would have been successful. As it was, however, the opportunity had passed. His first assailant had him at his mercy, and the man who had clambered up behind was in a position to deal him a nasty blow on the top of his head.

Tresholm reflected. He had little money with him, and he was unarmed Discretion was certainly indicated. He held up his hands

"1 will descend," he agreed, "if you will wail while I draw to the aide of the road."

"Vite!" was the harsh command.

Tresholm had every intention of keeping his word, but there was a most unexpected change in the situation. A flashlight illuminated the road. There was the report of a gun from behind, followed by another. The man who had accosted him dashed for the wood from which he had issued, followed by his companion, and the third, who had clambered into the coupé, leaped out and went down the ravine on the other side like a scared rabbit.

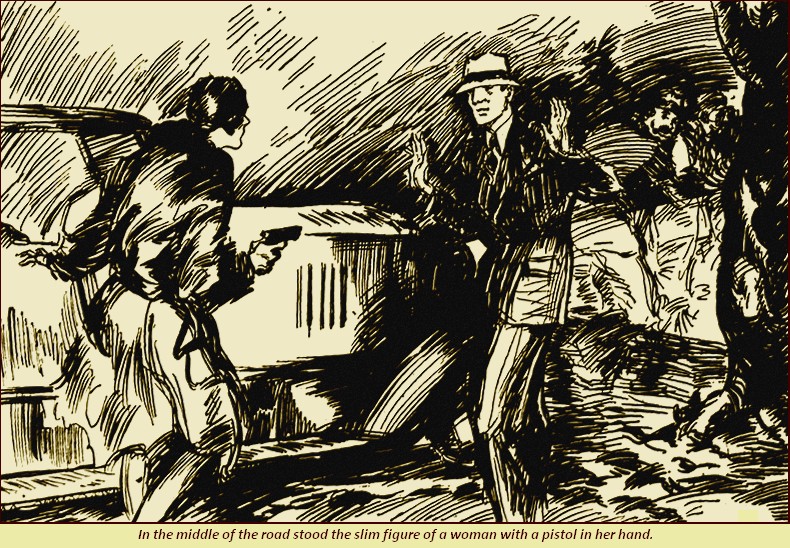

Tresholm descended to find them all disappeared, and the deus ex machina a small two-seated car with dazzling headlights, which had evidently just turned the corner. In the middle of the road stood the slim figure of a woman, with a pistol in her hand.

She nodded and beckoned him to her. He obeyed the summons, hat in hand. The twilight was merging into night, but the moon had scarcely yet risen. He saw her only indistinctly, but he gathered she was young, and, to all appearance, French.

"Mademoiselle," he said, "I am grateful for your arrival."

"One is foolish to travel along this road at night without being prepared for trouble," she remarked. Monsieur is probably a tourist, or he would have known that."

"It is true," he admitted.

"You are hurt?"

"Not a scratch."

"Or robbed?"

"Neither, thanks to you, Mademoiselle."

She glanced at him for a moment intently, almost, he thought, inquisitively.

He saw now that her eyes were dark and her features regular. She was sufficiently good-looking, but her appearance was spoiled by a lowering, almost sulky expression. She seemed to resent his presence, to resent having been under the necessity of offering aid. Her voice only was pleasant.

"Monsieur speaks French so well," she said coldly, "that I am in doubt as to his nationality."

"I am English. My name is Tresholm, and I am staying at the Hotel de Paris."

"You are the eccentric," she asked, "who registered here as a professional gambler?"

"My little joke," he apologized.

"Nevertheless," she went on, "you must have had some reason for what you did. You gamble at times, yes?"

"Now and then," he admitted.

"Piquet, perhaps?"

For a moment, Tresholm was oppressed with a sense of unreality. An attack by footpads in the center of civilisation, a deliverer so unexpected, and a question so apparently pointless!

What on earth could it matter to her or to anyone whether or not he played a somewhat neglected game? His companion appeared to realize his bewilderment; she stamped her foot and frowned at him impatiently.

"Please do not think that I am a crazy woman," she begged. "I have a reason for asking you such a question. Now will you please listen to me. You are Mr. Tresholm. Very well. You will admit that I have been of some service to you."

"A service for which I am greatly obliged," he assured her. "I should certainly have lost my temper and my money, if nothing else, but for your opportune arrival."

"Well, you shall do something for me in return," she said, still without the vestige of a smile, or any note of graciousness in her tone. "You will do me the favor of accompanying me to the villa where I live, which is near here, and taking either a whisky and soda or a cocktail before you proceed."

"I shall be delighted," he acquiesced.

She stepped back into her car and took her place at the wheel. "Will you follow me, please?" she asked, "I would ask you to drive with me, but I see that you have no chauffeur."

The two-seated car moved slowly on, with Tresholm behind. Just before reaching the outskirts of Monaco, the girl extended her hand, and they turned down one of the narrow roads which connect the Lower and Upper Corniche. After a few hundred yards' descent her hand went out again, and she turned between two broken-down gates, along an unkempt cypress-bordered drive, until they reached a deserted-looking villa. The façade was weather-stained and shabby. Its rows of windows were like great glaring eyes, uncurtained; the gardens were desolate; the whole place had an unkempt and forsaken appearance.

The girl descended from her car, and in obedience to her gesture, Tresholm followed her into an ill-furnished room upon the ground floor.

"A quarter to seven," the murmured, as though to herself. "Monsieur Tresholm, it is very hind of you to pay me this little visit"

"If I can be of any service," he ventured, more than ever puzzled.

"You may be," she answered. "I cannot tell. It depends upon what manner of man you are. You seem to have courage, although you let yourself be rescued from footpads by a girl."

He shrugged his shoulders. "I submitted to the inevitable, Mademoiselle," he replied.

She placed a bottle of whisky, a siphon and a glass upon the table.

"Have you ever heard of this villa before, Mr. Tresholm? Do you know who I am?"

He shook his head. "I must confess my ignorance."

"Well, they talk about us sometimes," she remarked,—"not very favorably. This is supposed to be a place to avoid. I live here with my father. He is supposed to be a man with whom you should have nothing to do. You are sure that you have not heard of us?"

"Quite sure, Mademoiselle."

"My name is Brignolles—Lucie Brignolles."

He shook his head. "I am sorry," he confessed, "but the name is unfamiliar to me."

"You never heard of either of us?"

"The other one being—?"

"My father—Monsieur Brignolles."

"Unfortunately, no. You must remember that you yourself correctly described me as a tourist"

"So much the better," she declared. "I will tell you about my father before we begin. You call yourself a professional gambler. An effort at humor, I should imagine, for you seem prosperous. My father is also a professional gambler. Unfortunately, the occasion is rare nowadays when he can find anyone to play with him. His reputation is none too good. He is barred from the Casino. We have no friends. Are you listening?"

"I have beard every word," ho assured her.

She looked across at him gloomily. He thought that he never had seen a more sullen expression in his life. Even the beauty of her eyes was marred.

"My father has ill health," she went on. "He cannot live very long. He has only one passion, and that is to play cards and to rob anyone who plays with him. I have to tell you this, but I am his daughter, and my sympathies are entirely with him as against any tool whose money he can take. I have been to Nice to try to find someone to come and play Piquet. He is quite invincible at Piquet He can win just as much money as his opponent chooses to play for. Will you play with him?"

"Certainly I will," Tresholm accepted, with a queer little smile. "I must warn you that I am rather good at the game myself."

"You could not succeed against my father, because he cheats," she rejoined curtly. "Nevertheless, it will probably make his last few days happier, if he can win some money from you. Can you afford to lose?"

"I certainly can," Tresholm assured her.

"You are wealthy?" she insisted.

"Sufficiently."

"Remember," she told him, "you are fully warned. You will not complain afterwards ?"

"I give you my promise," he replied, "that I will submit to whatever may happen to me."

She produced another siphon of soda-water and set out a card-table. "You need not he afraid of the whisky and soda," she said dryly. "This is a gambler's den, but that is the end of it. You are here to be cheated, but the drinks are all right. Sit there, please, and wait while I fetch my father. Your solitude will give you an excuse to escape if you are afraid."

He opened the door for her and she passed him as though utterly unconscious of his presence. Tresholm resumed his seat with a little grin. He loved adventure. Although he had a sort of instinctive confidence in the ungracious young woman who had just left him, he fully realized that he might very well find himself involved is a singularly unpleasant adventure. He waited for her return, however, without any feeling of apprehension. Very soon, he heard footsteps. She opened the door and entered.

Leaning upon her arm was a tall, emaciated-looking man whose suit of ancient gray tweeds hung loosely upon his shrunken figure. It needed only a glance into big face to convince Tresholm that the girl had been right about his health.

"This is my father," the girl announced shortly. "Mr. Tresholm. A gentleman staying down at Monte Carlo. He will play Piquet with you for an hour."

"Very good of him, I am sure—very good," the old man declared, as he extended a skinny hand. "Pleased to welcome you, Mr.—what did you say his name was, girl?" he asked harshly.

She spelled it out with care.

"Tresholm," he murmured. "Quite a good name. Very kind of you to give me a game, sir. Will you sit there? I have brought the cards."

He laid two packs of cards and some markers upon the table, and lowered himself, assisted by his daughter, into the chair. He commenced shuffling, and Tresholm watched his long fingers, fascinated. One part of the man, at least, retained its old nimbleness.

"What points do you care to play, sir?" the old man asked.

"I am in your hands," Tresholm replied.

"Would twenty-franc points seem too much?"

"I could manage that," Tresholm agreed. "I should warn you, sir, that although I have not played lately, I am supposed to be rather good."

The old man looked across at him without expression in his face.

"There is no one in the world," he said, "who can beat me at Piquet"

They cut for deal. Monsieur Brignolles won.

"It is permitted to smoke?" Tresholm asked.

"By all means," the girl acquiesced, "so long as you have your own cigarettes. We have nothing. We have just that bottle of whisky and some soda-water, in case we can find anyone foolish enough to come and play."

"And your father?"

She shook her head. "He neither drinks nor smokes," she confided. "His state of health does not permit it."

Whatever Monsieur Brignolle's state of health may have been, his mentality Tresholm decided, after the first few games, remained unimpaired. He discarded with brilliant intuition, and he played his cards unerringly. Tresholm for the first time found himself outclassed. He lost with better hands; he lost heavily with bands of equal value. Each time his opponent drew as though inspired. The last card was scarcely played before he was preparing for the next hand. It was as though he played for a great stake, and against the clock.

The girl did the scoring, and every time she passed the sheet to Tresholm for his inspection, she did so with a half-malicious, half-triumphant smile.

"You must say when you would like to leave off, Mr. Tresholm," she remarked once.

"Mr. Tresholm must have his revenge," her father squeaked hastily. "It is not for you to interfere."

"I can tell you one thing, Mademoiselle Brignolles," Tresholm confided. "Your father is not only the finest piquet player whom I have ever encountered, but I can assure you that he is also the finest player in the world. I have never seen such intuition. One could imagine that he might be one of those rare people in the world who can see through the back of the cards."

The girl shot one malign glance at him and did not speak again until the next game was finished. Tresholm glanced at his watch.

"You are afraid of being late for your dinner?" she asked, with a note of sarcasm.

"Not in the least." he assured her. "I only looked at the watch to be certain that I should not be. If I leave here in another half-hour, that will suit me admirably."

"If you are sure you can afford it," she mocked, "Prosperity has come to the house. I see that you already owe nineteen milles."

"I must economize in other directions," Tresholm replied. "At any rate, I am having a wonderful lesson at the game."

They played on in silence. The old man shivered every now and then, as though affected by an ague, but the cards left his hand with uncanny precision.

In the intervals between the deals Tresholm ventured to glance around, and it seemed to him that he never before had sat in such a terrible room. The color-wash was peeling off the walls. There was dust upon the frames of the few hideous pictures. There was not a whole article of furniture in the room. To make matters more uncomfortable, there was a fire of huge logs burning upon the hearth, and not a single window open, but although Tresholm felt his cheeks burn and his forehead become damp, his host's face never changed in its waxen pallor. A sudden vigorous distaste of his surroundings, the ugliness it all, the terrible old man, the sullen girl got on Tresholm's nerves. He began to make mistakes in playing his cards and suffered for them severely. The girl smiled maliciously.

"Only ten minutes longer," she consoled him. How glad you will be to go. Never mind, worse might have happened, if I had left you to the robbers on the hill."

"The game is very interesting," Tresholm assured her, speaking with an attempt at lightness. "I am outclassed, but so would anyone else be."

She shivered palpably. Her father's long, nervous fingers were toying with the cards which remained in the little pack. He drew them out one by one, glanced back at his own hand and hesitated. Finally he discarded, throwing three cards only, instead of five, to which he was entitled. Tresholm, when the last card fell upon the table, had lost more than in any previous game.

The girl began to add up the scores. Her father looked over her shoulder, checking the totals. When she had finished, she looked at them in dismay.

"Do you know how much you have lost, Mr. Tresholm?" she asked.

Quite a good deal, I am afraid," he replied.

"You have lost thirty-one thousand francs," she announced.

"As much as that?" he rejoined coolly.

"Have you the money in your pocket?" the old man asked, with a note of nervous harshness quavering in his voice. "If not, my daughter had better return to the hotel with you."

"I never carry more than a few milles," Tresholm replied. "I have my check-book."

"Where do you bank?" Brignolles asked.

"Here in Monte Carlo"

The old man's face cleared. "If you have not the money, I must take a check then. Lucie, fetch pen and ink."

She placed writing materials upon the table, and Tresholm wrote out a check

While he was filling in the counterfoil he was conscious of someone looking over his shoulder. He turned around and met the old man's greedy eyes.

"But what a balance!" the latter declared breathlessly. "You are a rich man, Mr. Tresholm?"

"I have enough for my needs," was the quiet reply.

The girl threw open the door. "What does it matter to us whether Mr. Tresholm is rich or not?" she demanded. "He has enough to pay his debt." His debt?" Tresholm murmured. She looked at him with challenge in her eyes. The old man shuffled across to the cupboard and took out a glass and a bottle. The girl swung around. "Come this way," she enjoined. "I will see you out." They passed down the wretched little hall, and she opened the front door.

Well," Tresholm said, "many thanks for saving me from the bandits."

"Nothing to thank me for," she rejoined curtly. "You paid, all right."

She closed the door, and Tresholm drove away from the place with an infinite sense of relief. The girl returned wearily to the shabby little room. Before she reached the door, she heard her father calling her. He was standing at the table with a pack of cards in his hand.

"Lucie," he cried, "where is the other pack?"

She shrugged her shoulders. "I do not know," she answered.

"It is gone!" the old man shrieked. "Do you suppose—?"

She searched the table, turned the box upside down, looked everywhere feverishly. Then they faced one another—father and daughter.

"He has taken it away!" the former groaned. "Stop him, Lucie!"

She listened to the sound of Tresholm's horn as she turned from the avenue into the road.

"Too late!" she muttered. "You may as well tear up the check, Father."

At eleven o'clock on the following morning, the girl stood in the road below the bank and watched the great doors roll slowly back. She looked in her bag. The check was safely there. She closed it, turned her back upon the Boulevard des Moulins and slowly entered the gardens. She chose a secluded seat and sat there in what seemed to be a sort of apathetic stupor. After some time she rose, left the gardens by the lower exit, and looked up at the Casino clock. It was exactly eleven.

She crossed the road, sat down at one of the tables outside the Café de Paris, and ordered a cup of coffee. At half past eleven she paid for her coffee and mounted the hill. At five-and-twenty minutes to twelve she crossed the portals of the bank. She made her way to the nearest cashier's window, unfastened her bag, and produced the check. As she handed it across, she felt her heart give a great throb. For a single moment the man's face before her was blurred; everything in the bank was hazy. Then she came to. She was herself again. Even the sullen expression had returned. She was like any ordinary customer waiting for her money.

"Would like any small change, Madame?" the cashier asked.

"A little please," she answered, not too steadily.

He glanced at the check once more. Then he counted rapidly through three packets of ten-mule notes pinned together, pushed them across the counter, and added a mille in hundreds and fifties. The girl stuffed them into her bag. She walked a little uncertainly towards the door. Then she came face to face with Tresholm, who was talking to the bank manager. She gave one little gasp, but recovered swiftly. She was passing on when he stopped her.

"How do you do, Mademoiselle," he said. "I hope you found that I had enough money to meet your fathers check."

The bank manager laughed. An excellent joke. The girl looked at Tresholm, and for a moment he was startled. There was a curious new quality in her eyes.

"Could I speak to you for a moment?" she asked.

"Certainly." he acquiesced.

Ho opened the door for her and nodded his farewell to the manager. She led the way across the road to the gardens.

"How is your father this morning?" Tresholm asked politely.

"He is well as he is likely to be," was the toneless answer. "Do you mind sitting down here; I wish to ask you a question."

He seated himself by her side, immaculate in his white flannels, his pongee coat and the carnation is his buttonhole. In the rather pitiless sunlight, the shabbiness of her own clothes, well-cut thought they were, was a little pathetic.

"I want to know why you did not stop payment of that check," she demanded.

"Stop payment of the check?" he repeated. "But why should I? I lost the money." "Yes, you lost the money," she agreed, But—" She paused significantly.

"If you thought I was going to stop payment of it," he asked, "why weren't you here on the steps at ten o'clock this morning?"

"I was," she confessed. "That was what I was supposed to do—to cash it as soon as the doors were opened. I thought I would give you a chance though. I waited."

"Very sporting of you!" he murmured. "Anyhow, I never meant to stop it."

"Why not?" she persisted. "You know that you were cheated; you know that my father was playing with marked cards. You even brought them away with you as evidence!"