a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Gleanings, Volume I : 1903-1909 Author: E. Phillips Oppenheim * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1300341h.html Language: English Date first posted: Jan 2013 Most recent update: Feb 2013 This eBook was produced by: Roy Glashan Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

gleanings, pl.n.— Things that have been gathered bit by bit—the gleanings of patient scholars. The American Heritage Dictionary.

THE hoarse striking of a distant clock broke in upon his meditations. Nine o'clock! His day of slavery had commenced. He laid down the book upon the wooden stall before which it was his custom to linger for a minute or two most mornings. Something had lodged in his throat; it might have been a sob! He had been so absorbed that he had forgotten where he stood, whither he was bound, it all came back to him with such grim yet facile insistence. London Bridge Station, disgorging its crowd of suburban business men, the heavy atmosphere of Bermondsey down the steps below— Bermondsey, with its nauseous odors, its smoke-stained warehouses, in one of which his own stool was awaiting him. It was disillusion, complete, entire—a veritable mud bath after the breath of roses.

For this book had spoken of very different things. It had spoken of heather-crowned hills, of gorse bushes yellow with sprinkled gold, of a west wind, fragrant, melodious in the pines; of flower-wreathed hedges and blossoming trees; of the song of birds and the glad murmuring of insects.

A dull flush stained his sallow cheeks. For once he lost his stoop and stood almost upright. It was the one moment of inspiration which seems to be the heritage even of the very meanest creature who ever walks the earth. The spirit of rebellion leaped up in him like a flame. His way lay, as it had ever done, down those fateful steps. Nine o'clock had struck, and 9 o'clock was his hour. He ignored it. He crossed the station yard and entered the booking hall.

"Then you won't tell me?"

"Won't tell you what?"

"Why you come here, in those clothes, and with no luggage. You must have some friends in Lidford."

He shook his head. "I never heard of the place before," he assured her. "I picked the name out from the time-table. It sounded like the country, and it was a long way off."

She looked at him with incredulity plainly written in her sedate, beautiful face. "Of course," she murmured, making a pretence at rising, "if you don't want to tell me—"

"Please don't go!" he interrupted, in alarm. "It is the truth, really! I know no one here. I only wanted to get away."

"To get away," she repeated, thoughtfully. "Do you mean that you have been doing something wrong?"

"Something wrong!" He repeated the words vaguely, with his eyes fixed upon her all the time. She had risen and was looking at him seriously. Her eyes were blue—such a wonderful blue, like the sky which he had been watching lazily all the afternoon, lying on his back in the deep cool grass; and her hair—ah! there was nothing which he had seen so beautiful as that! Then, warmed by her obvious gravity, he hastened to reassure her.

"No," he declared, "I have done nothing wrong. I have run away from my work, that is all. I read in a book this morning of the country, of the, sunshine, and the wind, and the birds, and—all this." He waved his arm aimlessly about. "I had to come—I couldn't help it."

"You have come from London—here?" she exclaimed.

"Yes!"

"And your luggage?"

"I brought none."

"And your hat?"

"I threw it away. It was a very old, shiny hat, with ink on the bare places. What would have thought of me wandering about the fields in such a thing? It is bad enough as I am."

He glanced disparagingly down at his shabby black clothes and dark trousers, frayed at the ends, but carefully pressed and cleaned. She shook her head. She was a little bewildered.

"I am sure that your clothes are very nice." she said, "and you were wrong to throw away your hat. What are you going to do without one?"

"I have no idea," he answered. "But, then, I have no Idea what I am going to do with myself, so it really doesn't matter, does it?"

"I think." she said, deliberately, "that you are the very queerest person I ever met. Do go on talking to me! Tell me some more about—yourself."

"There is nothing interesting to tell," he assured her, a little wearily. "I would rather listen to you. Tell me some more about the birds."

She shook her head impatiently.

"What is your name, please?" she asked.

"Stephen Marwood," he answered. "I am an orphan, and a clerk in a warehouse. I get twenty-five shillings a week, and I add up figures and make out invoices from 9 till 6 in a cellar, with the gas burning all the time. I live in a long, ugly street, surrounded by miles of other streets. I am just one of a million. I work and I sleep, and I work again, and all the time my lungs are choked with fog and smoke and bad smells."

"It doesn't sound nice," she admitted.

"It isn't!" he assured her.

"And yet." she added, with a little, wistful sigh, "it is London."

"It is certainly London," he declared. "It might as well be hell."

She looked at him wonderingly. After all, he must be a little mad.

"And where," she asked, reverting once more to the practical, "are you going to sleep?"

"I don't know." he answered, dreamily, "and I don't care, if only I can smell this honeysuckle all night."

"And your tea and supper?" she asked, scornfully. "Will the scent of the honeysuckle satisfy your hunger as well?"

He closed his eyes for a moment. Removed from all distractions, he was forced to admit that he was hungry. "I shall go down to the inn." he decided. "I suppose there is an inn here. But you?"

She pointed downward to where the gray smoke rose in a straight, thin line from a red-tiled cottage. "There is no inn," she told him. "but my aunt will get you some tea, if you like. We often have parties."

"We will have it together, then?" he begged, eagerly.

"Perhaps," she answered, laughing.

A month afterward they met almost in the same place.

"Let us climb to the top and watch the reapers," he begged. "There is a field on the other side where the poppies are all in clusters, like specks of blood in a waving, yellow sea. I was watching them all this morning. By to-morrow they will be gone. The men seem to creep like insects, but all the time the grain falls."

She sighed. She was dressed in black. She looked thin and there were tears in her eyes. But more wonderful still was the change in him. He carried himself like a man; a healthy tan bad burnt his cheeks, his eyes were bright with health. Even his voice had acquired a new firmnesss. The drudge was no more. The yoke of his servitude was cast aside. To-morrow he might starve. His small savings, in fact, were almost spent. To-day, at least, he was a man.

"What strange fancies you have!" she declared. "The farmers hate the poppies, and these overgrown hedges which you admire so much ought all to be cut down and trimmed."

He laughed. "Give me the honeysuckle and the creepers," he declared. "I have seen enough of the ugly and the useful to last me all my life. Come, it is only a few steps further. Give me your hand."

Breathless, they reached the summit of the hill and the shelter of the little grove of pine trees. She sat down with her back to the trunk of one of them. He threw himself by her side. Below them the slumbering landscape, warm and mellow in the afternoon sunshine, and in their faces th« west wind.

"I believe in heaven," he murmured. "I have found it."

A delight, almost a fervor, was in his eyes as they wandered on and on to where the limits of his vision ended in a faint blue mist. She looked at him as one who seeks to read a book written in a strange language.

"I do not understand," she said. "It is beautiful here. I know, because everyone says so, and it is pleasant to sit and watch it all for a while. But I have sat here all my life, and I am weary of it."

"Weary!" he repeated, in amazement. "Weary of this country, of this life!"

"Sick to death of it!" she answered, with a vigor which was almost bluntness. "Who can sit and look at one picture all their lives, however beautiful? The fields and the hedges change only from winter to summer, from summer to winter. And the people change never."

He pointed to the little graveyard away in the valley. "It is not true," he declared. "They have their joys and their sorrows also. There was merriment enough at the harvest home the other day, and the whole village wept over that last little mound in the churchyard."

She shook her head impatiently. A strand or two of her hair was loosened; the sun flecked it with gold. He realized then that she was beautiful. She sat there like a self-enthroned goddess.

"The people are all very dull and very ignorant," she said. "Their lives are narrow; they sleep and they eat, and they die—but they do not live. They never live."

He was alarmed. "Go on," he said, in a low tone. "You, have something in your mind?"

"It is true," she admitted. "While aunt was alive, I was a prisoner. Now, I am free. I want to escape."

"Escape—from here?" he murmured. "Why, this is Paradise!"

She laughed softly, but with her mirth was mingled a subtle note of mockery.

"You are a very foolish person." she said, "you do not know what ambition is. I do not want to sit upon the bank all my life."

"There are many who drown," he murmured.

"I will take the risk," she answered.

All the joy and freshness seemed to fade away from his face. Something of the old haggard despair came back to him. This was the end, then, of all his dreams.

"Yesterday," he said, in a low tone, "I walked to Market Deeping. I got a situation with Sheppards', the auctioneers, and Mrs. Green, in the village, has promised me a room."

Her lips curled a little. "If it satisfies you—" she began.

He interrupted her. "Don't mock me!" he cried, roughly. "Nothing satisfies me if you go away. You know that."

"That is foolish," she said, "for I am most surely going away."

"To—London?"

"Yes. I have written to my cousin there."

"It would have broken your aunt's heart," he said.

"While she was alive I obeyed her," the girl answered, defiantly. "Now she is gone my life, is my own."

"Yes." he murmured, "yes. Our lives are all our own. See how the corn falls, Esther. . . . They have reached the last belt, and all the poppies are gone."

At first she wrote to him. He carried her letters with him backward and forward, reading them, studying them, always treasuring them. Save only for this one sorrow , the sorrow of her absence and his constant anxiety concerning her, his life had become a joy to him. His work was simple, and he did it better than it had ever been done before. His little office was bright and clean, his window looked out upon a quaint old cobbled market-place. In front was a garden, bright even in these late autumn days with simple flowers. Backward and forward he walked to and from his work, and the wind and rain and sun seemed each in their turn the sweetest things he had known. He grew in stature and in breadth: the latent possibilities of his manhood asserted themselves. In the little village he became a popular person. He attempted gardening, and every one was willing to help him with advice and bulbs, and the promise of seeds. He even ventured to discuss the crops with the farmers whom he met on the way . He remembered that he had once, before the evil days, called himself a Christian, and one Sunday morning he found his way to the village church. He came out with a curious sense of removal from that part of his life which was still something of a nightmare to him. Henceforth the memory of it never troubled him. He had come into real and intimate kinship with these simple folk among whom chance had brought him.

And then her letters ceased. He wrote and wrote again, but there came no reply. He bore it as well as he could, and then, one day, a chance remark brought the stinging color into his cheeks, and his heart for a moment stood still. He applied for leave of absence and went to London.

The address which she had given him was No. 127 West-st., Edgware Road. But when he reached it he felt again for the letter in his pocket. No. 127 was a public house. Yet that was the number at the head of her letter. He pushed open the swing doors and entered.

There was a smell of stale beer and fresh sawdust. An unwholesome looking youth, collarless and unwashed, was cleaning the stains of beer pots from the marble-topped tables. A couple of carmen were wrangling in a corner, a dissolute looking person in seedy black was drinking at the counter and carrying on a desultory conversation with a young person, behind the bar. Marwood addressed himself to her.

"Can you tell me if Miss Day lives here?" he asked. The young person looked at him curiously.

"Used to!" she answered. "She's gone away now."

It was true, then. Esther had really lived in a place like this. He looked about him wondering, and back at the young person behind the bar, who seemed undecided whether to resent his scrutiny or to encourage him as a possible admirer.

"Can you tell me—her present address?", he asked.

The young person jerked her head toward a swing door, leading apparently into an inner bar. "Don't know," she said. "I dersay Mrs. Molesworth can tell you. She's in there."

Marwood pushed open the swing door. A stout, florid woman stood behind a circular counter flanked with a gorgeous array of mirrors and glasses. She was apparently engaged in the task of turning sundry black bottles upside down and holding them up to the light to estimate their contents.

"I beg your pardon." he said. "I believe that Miss Day has been staying here. Can you give me her present address?"

The woman set down the particular bottle which she was examining and looked at him fixedly.

"And what might be your business with Miss Day?" she asked.

"My name is Marwood," he said. "I knew Miss Day down in Somerset."

The lady nodded her head vigorously. She became, if possible, a little redder in the face.

"Then all I can say is that it's a great pity you didn't keep her in Somerset." she answered. "What's the use of a girl like her, with scarcely a rag to her back, coming up here with such notions? Wouldn't do this, and wouldn't do that—as particular and finicky all the time as you please. Drat the girl, I say, niece or no niece!"

"I am sorry," Marwood said timidly. "I daresay it was a great change for her up here. Can you tell me where I shall find her?"

"No, I cannot," the lady answered, as though incensed at the question. "And, what's more, if I could I wouldn't, and good-day to you, sir."

She swung around and disappeared through a door leading to an inner room.

Marwood left the place with hot cheeks. Some shadow of the humiliation which he could well imagine had been her lot seemed also to have fallen upon him. For two days and two nights he sought her in all manner of places and thoroughfares. Then chance befriended him. She was standing beneath a lamp post, and he was in the shadows. There was no one to see the tears which filled his eyes, to hear the sob which rose hot in his throat. She was tall and thin and pale. Her eyes, were larger, there was a pinched look about her features. Her clothes were shabby. He thanked God for that. She was talking with a man—a gentleman, he seemed to be, well dressed, good humored, debonaire. Marwood listened.

"And how does the show go?" the man asked her.

"Oh! I am no judge," she answered, wearily. "It seems stupid enough from the wings. I am only in the chorus, you know. I have nothing to do, really."

"We are going to alter all that," the man said, swinging his cane. "I shall speak to Randall and hammer a small part out of him, somehow. But, by Jove, Miss Day, you look awfully pale!"

Then Marwood saw her stumble for a moment, as though she.were dizzy. She recovered herself almost immediately.

"I am—quite well," she said. "A little tired, perhaps."

The man suddenly threw away his cigarette.

"Look here, Miss Day," he said, "you've done a very foolish thing! You've missed your luncheon. You girls are always forgetting your meals. I never do. Come along. No, I insist!"

Her faint protestations were of no avail, and Marwood felt the blood run cold in his veins, for he had seen for a second what no one can ever see and mistake—the wolfish gleam of hunger in her eyes, come and gone like a flash, but more eloquent than any spoken words. Then the restaurant doors before which they had been standing opened and they disappeared Inside. Marwood waited. It was an hour before they came out. The transformation in her was amazing. The lines seemed to have been smoothed from her face: there was color in her cheeks and light In her eyes. Marwood, who had been standing on the opposite side of the street, started to cross the way, but he was too late. Somewhat unwillingly, as it seemed to him, her companion hurried her into a hansom, and followed.

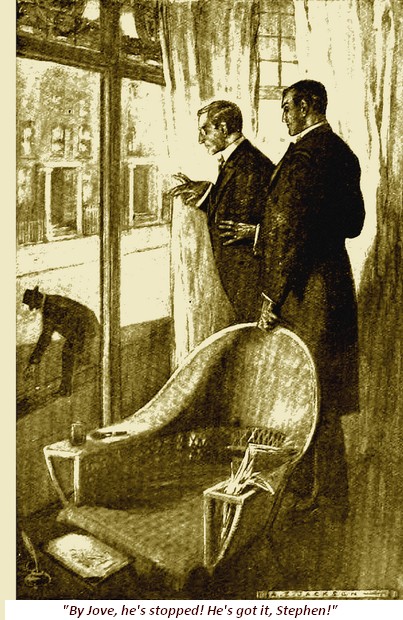

Marwood caught a glimpse of the man's face under the gas-lamp—it was sufficient. When the cab drew up before a row of flats a little west of Pall Mall he was already turning the corner. He saw Esther alight, hold, out her hand: he could see her hesitation, her reluctant footsteps. He caught the man's eager tone as he bent over her hand—

"For a moment—not more than five minutes. I must show you the little play—and I believe that the part would suit you admirably. We will keep the hansom, it you like. I will send you home."

Marwood called out, but his voice sounded weak even to himself. The door was closed.

He leaned for a few moments against the palings. He was out of breath, and to him there had been something tragic in the disappearance of those two, the man and the girl, behind that closed door. His imagination ran rife. He saw hideous things. Almost he was ready to creep away—to escape—to forget. Then, as he returned to a more sane state of mind, he saw her as she came first to him, her hands clasped behind, her head. thrown back as she walked blithely through the clover-scented meadows, humming some forgotten tune. With an oath, he trod the flags and rang the bell. A liveried servant let him in and led the way toward the lift.

"Which floor, sir?" he asked.

"I want the gentleman's rooms who has just come in with the lady," Marwood answered, his hand in his pocket.

"Mr. Borrodale—fourth floor, sir," the man remarked, closing the gates of the lift.

The man servant in plain black livery blandly denied Mr. Borrodale's presence. His coat and hat on the hall table, however, emboldened Marwood. He pushed his way in.

"It's no use; you can't see the governor!" the man declared, angrily. "Out you go!"

The veneer of civility had departed. He attempted the bully. Marwood heard a woman's cry, and he struck the man on the mouth. Then with an oak chair he thundered upon the closed door of the room from which the cry had come. A man swore and a woman sobbed. Marwood sent a panel crashing out of the door, which was suddenly thrown open. He caught one glimpse of her face, pale and terror-stricken, as she flitted by. He would have followed, but master and servant were too many for him. The latter struck him from behind, and he spent the night in a hospital. When he sought her again it was in vain.

So Marwood returned to his country life and his routine work. One day, old Mr. Sheppard, his employer, called him into his private office.

"Marwood." he said bluntly. "I am getting on in years, and I want a rest. I have saved a little and I have only my daughter to think of. Will you take the business—and marry her?"

Marwood sat still and thought. He watched the dusty floor specked into gold by a long shaft of sunlight, and he saw things there which the four walls of that room had never held. Presently he looked up.

"I want a month's holiday," he said. "When I return I will answer you."

The old man grunted, but gave his consent. Once more Marwood travelled up to London, and renewed his search. This time he succeeded very easily. Esther Day was well known now. Her name and her pictures were in all the papers. She was acting at the Frivolity, and she had made a "hit."

He called upon her, and he felt his courage oozing away. He felt the slow dissipation of the one romance of his life as they talked together. She was well dressed, prosperous, more beautiful than ever, with all the light smartness of the modern Londoner. To their last strange meeting she made no allusion. She gave him tea, and showed him her new poodle. She talked of theatrical matters as one in the know—and to him it was jargon. When he stood up to go, he made one effort to break down the barriers which seemed to have grown up between them.

"And you have, found," he asked, holding her hand for a moment, "the things you sought for?"

She laughed.

"I have learned wisdom," she answered. "I have learned how much to expect."

He fancied that she hurried him away. As he left the door a brougham drove up, and a young man alighted—a young man of the type he knew nothing of—immaculate in dress and person, good-looking, languid. Marwood went back to the country that night.

Yet he delayed his answer, though old Sheppard grew more and more impatient every day. Marwood passed through a curious phase of his emotional life. Mary Sheppard was pretty in her way, and waited only for him to speak. Yet he hung back with something of the feeling of a man called upon to sign his own death warrant. An impending sense of the finality of life seemed to him to be inevitably coupled with the decision which the old man and the girl were now awaiting with almost obvious eagerness. He had no great aspirations, nothing which could rank as ambitions. Yet behind the trend of his daily life, his ordinary, well-performed tasks and simple pleasures, he felt at times the dim, unrealized presence of greater things, a more quickening and satisfying life. Sometimes, in the night, he sat up in bed and stretched out his arms—for what he scarcely knew. He wandered up on to the hilltop and watched the reapers. Some shadow of a far distant, impossible dream seemed to still torment him with intangible and unsatisfying longings. And all the time the old man and the girl waited. In the end they had their way.

She came into his little office—a curiously incongruous presence in her fashionable clothes, bringing with her the subtle air of the city and of all those nameless things, the presence of which had so estranged him on his last visit to her. But this time he had no consciousness of them, for she looked into his eyes and it was the look for which he had prayed so often.

"My friend." she murmured, "you were right. I am weary of it all. When you came to me I was brutal. I owe you so much, and I wanted to escape the debt. I have come to pay it, if I can."

Her hands had stolen into his. It was, after all, like a dream—a beautiful dream poignant with unutterable bitterness.

"Come out with me." she murmured. "I want you to take me through the meadows and up to the hill where we watched the reapers. Will you come?"

He let fall her hands, and a great sob rose to his throat.

"I cannot!" he said.

A fear stole Into her eyes.

"Don't tell me that you have changed!" she pleaded.

"I have never changed," he answered gravely; "but I am married to Mary Sheppard. It was her father's last wish, and it seemed to matter so little."

She laughed—a curious, dry, mirthless laugh.

"I hope that you will be happy," she said. "Somehow, I never thought of this. And, after all, my coming was only a whim. I must act to-night, and to-morrow night—and all the days of my life."

He heard the rustling of her gown as she left him. He heard the office door swing to and close. He sat on his hard chair, and once more he looked steadily with fixed, sightless eyes into that long shaft of golden dust. Then his head sank lower and lower—into his hands. He leaned forward upon the desk. Before him stretched the long, level vista of weary days—the treadmill of an unlived life. Some one shouted to him from the top of the stairs. It was like the sentence of his doom—

"Stephen, are you coming up to dinner or are you not?. Everything will be cold!"

He rose slowly and ascended the stairs.

"Mr. Anderson, I am sure. I recognised you directly. What a strange chance that we should come across one another in this out-of-the-way part of the world!"

I had risen to my feet, of course, immediately she had taken me by surprise by halting in front of my small table. It was not possible to avoid taking the delicate long hand with its white fingers so frankly held out to me. We shook hands solemnly while I ransacked my brain for some coherent speech of apologetic denial. And then something in the expression of her wonderful brown eyes, a faint meaningful contraction of the eyebrows as she looked straight at me, altered the whole situation. She knew quite well that my name was not Anderson; she was perfectly well aware of the indubitable fact that these were the first words which we had ever exchanged.

I mumbled something idiotic, and she turned to glance down the room. The old man with whom she had entered, a decrepit, weak-faced, but aristocratic-looking, Englishman was shaking hands with an Italian, whom I had been told was a native of the place, and who had evidently come in to dine. They were out of earshot, and for the moment were not observing us.

She leaned over towards me.

"I have seen you here for the last few evenings," she said, hurriedly. "Tell me your real name."

"John P. Shrive," I answered. "I am an American."

The corners of her lips twitched slightly, and those wonderful eyes, which for several evenings I had done little else save sit and admire from a respectful distance, were filled with laughter.

"So I thought," she answered. "I wonder—I wonder whether you would care to do me a service?"

My words tripped one another up. I was incoherent, but earnest. For two days I had been vainly trying to find some excuse to speak to her. I had attempted a conversation with her father, and suffered the ignominy of a chilling repulse. A service. There was a very little in the world which I would not have attempted for her.

"After dinner, then," she said, "do not sit out in the front. You will find some seats at the back of the house. Order your coffee there, and I will come when I can. And remember this. If my father or Count Perlitto should speak to you don't be drawn into any conversation at all. Be rude to them if you can. Don't tell them anything about yourself or your business."

"Count Perlitto," I observed, "is the little dark gentleman with the brushed-up moustache?"

"Yes! But it is my father who is most likely to ask you questions. Please don't think that this is a conspiracy, or anything very terrible. I will explain it all to you presently."

With a little smile and a nod she turned away and joined the two men at the other end of the room. I ordered double my usual quantity of wine and began my dinner.

Now, for two evenings I had dined alone at this same little table, which I had carefully chosen because it afforded me the most satisfactory view of the most beautiful girl I had ever seen in my life. She was tall and very slight, her hair was lightish brown, and here and there a glint of gold, and she had that French trick of laughing with her eyes which I never could resist. She wore delightfully cool muslin gowns, and about her whole person, her jewellery, her shoes, and the care of her hands, there was a certain inexplicable daintiness which was as much a part of her as that delightful little laugh which seemed to me the most musical thing I had ever heard in my life. But to-night things were different. I myself had become an object of the most surprising interest to her two companions. I saw the girl lean forward and talk to them as she trifled with some new and highly-seasoned hors d'oeuvre, and the effect of her words was instantaneous. Her father fumbled for a moment with an enormous horn-rimmed monocle, having successfully fixed which in his left eye, he turned and transfixed me with a most tremendous stare. The little Italian displayed a similar interest in slightly different fashion. He kept darting sidelong glances towards me, showing his white teeth and curling his black moustache, and all the while talking in most animated fashion to his two companions. This sort of thing went on more or less during the entire progress of the meal, to my great discomfort. No sooner did I raise my eyes to steal one of my customary glances towards the young lady than either the horn monocle with its blank, unwavering stare, or the little Italian's keen black eyes were fixed upon me. Between curiosity and annoyance, my dinner was completely spoilt. I missed a course, and was in the act of rising when I saw the whole party hurriedly leave their places and bear down upon me.

Her father, who only yesterday had responded to some attempted advances on my part with truly British hauteur, stopped at my table and smiled genially upon me.

"If you are taking your coffee outside this evening," he said, "will you join us? This is my friend, Count Perlitto, who is a large landowner in the neighbourhood; my daughter I believe you have already met."

I glanced towards her and found a decided negative engraven upon her frowning forehead. On the whole, though I was burning with curiosity to know what the whole thing meant, I was glad to have an opportunity of asserting my independence.

"I'm very much obliged to you, sir, for the suggestion," I said, "but I'm afraid it's quite impossible. I have a great deal of writing to do to-night, and the mails out here are a trifle scanty."

I distinctly saw the two men exchange rapid glances as I mentioned the writing.

The Count interposed. "The writing. Oh, yes," he said, "but afterwards? The evening is positively too fine to be spent within the doors—beneath the roof—ah, you understand? Besides, you are a tourist, is it not so, from a great country? We would wish, we who live here, to show hospitality to those who come so far from the large cities where all the sightseers find their way. Here it is very different. Here you see the true Italy. You will do us the honour, signor? There is some liqueur, not of the house, which is to be recommended."

Guidance was before me in the frown, now even more forbidding.

"Very sorry, Count," I said firmly. "It is quite impossible for me to join you this evening."

He departed with a polite expression of regret. The girl smiled at me over her shoulder, which I took to mean that so far I had done the correct thing. I sat down in my chair, poured out a glass of wine and tried to puzzle out where I stood. The Count, who was, as I well knew, the great landowner of the place, and whose aversion to tourists was a byword, and who had several times passed me on the road with an insolent stare, was suddenly more than commonly anxious to make my acquaintance. The father of the young lady who had been the object of my respectful, but vehement, admiration, after repulsing my advances in the most freezing manner, was displaying at least a similar anxiety. The change in both of them dated from the moment when the young lady herself had directed their attention towards me. The undoubted inference then was that she had told them something or other concerning me which had aroused their interest. I determined to go and find out what it was.

The place to which I had been directed was deserted when I arrived there, and deservedly so. There were a few iron chairs, a patch of scanty grass, a long line of outbuildings, and beyond the sloping vineyards. I lit a cigarette, but decided not to advertise my presence there by ordering coffee. In a very few moments I heard the soft rustle of advancing skirts, and she came round the corner of the grey stone building.

Whatever this matter was in which I was becoming involved, it apparently savoured more of comedy than tragedy, to judge by the suppressed laughter in the girl's face. I wiped the dust from a chair with my handkerchief, and she sat down beside me with the utmost composure.

"I suppose, Mr.—Shrive," she began, "you have made up your mind that I am a most forward young person."

"If you want me to tell you exactly what I think of you," I answered, moving a little nearer, "all I can say is that I'm ready to go straight ahead."

She nodded composedly.

"Yes," she said, "you look like that sort of person."

"What sort of person?" I asked.

"The sort of person who goes straight ahead. It's a characteristic of your country-people, isn't it?"

"When one's mind is made up," I said, firmly, touching, as though by accident, the back of her chair.

"There are some necessary explanations," she murmured. "Afterwards—"

She looked at me. I withdrew my hand.

"Please go on," I said.

"My father's name is Derwent," she said. "He has come out here to look at a silver mine belonging to Count Perlitto. He wants to buy it."

I nodded.

"Yes," I said, encouragingly. "The Count looks like the sort who have silver mines to sell. We get plenty of them out in Boston."

"My father thinks he is a good business man," she continued. "As a matter of fact, he has lost nearly all his money speculating in things which he doesn't understand a bit. He has about twenty-thousand pounds left. That is all we have to live upon. The Count is asking twenty-thousand pounds for this mine. If my father buys it we shall be penniless."

"Sure the mine's no good?" I asked.

"Absolutely," she answered, with the first note of impatience in her tone. "Ask yourself what the probabilities are. My father knows nothing about mining himself, and he has not even an expert's opinion upon it. He goes entirely upon the Count's word, and what the Count chooses to show him. Why, the mine isn't being worked—hasn't been worked for thirty years."

"Perhaps," I suggested, "the Count hasn't the capital to work it. Labour out here's mighty cheap, but up-to-date mining takes a lot of money."

She looked at him with a faint frown. The smile had gone from her lips.

"The mine is worthless," she said, simply. "I am sure of it. I have read up its past history, and if ever there were silver there at all it has been exhausted long ago. But even granted that there is a chance in favour of the mine—which there isn't—I want you to remember that this twenty- thousand pounds is all that stands between us and beggary."

"In that case," I said, decidedly, "your father is mad even to think about the deal."

"I knew," she said, "that you would agree with me. You can understand, can you not, the trouble I am in? My father's mind is practically made up. He means to buy the mine. I saw a telegram to his lawyers, ordering them to realise our last securities. The moment the money comes, my father will sign the deed of purchase."

"Has he no friends," I asked, "whose opinion he would take?"

"Not one," she answered. "He has always been so foolish that I think everyone is tired of advising him. He always goes his own way in the long run. He is so painfully obstinate. I do not think that there is anybody who can help me—except you."

Her hand fell upon my coat-sleeve, and mine promptly closed over it. She made no movement to draw it away. I felt that I would have pitched the Count down one of his own shafts with pleasure if she had asked me.

"What can I do?" I asked.

"I will tell you," she said. "A plan came into my head when I saw you sitting there alone this evening. Somehow—you looked helpful, and—I had an idea that—you know you behaved rather badly, haven't you?"

"You mean that I have looked at you a good deal," I answered. "I couldn't help it, Miss Derwent, indeed. It wasn't impertinence. I just felt that I wanted to know you badly, and the next best thing was to sit in my corner and watch you. You are rather nice to watch."

"Am I?" she asked, softly.

"You couldn't give me greater happiness," I said, "than to help you—if, indeed, that is possible. You see, helping implies a reward, doesn't it?"

"You want bribing, then?" she asked, with affected coldness.

"Call it an incentive," I answered.

"At least—if it is all I can get—a word of gratitude from you will be worth all the trouble you can give me."

"Is that all—you will expect?" she asked softly.

I felt my heart thumping against my ribs. I wanted to raise her fingers to my lips, and draw her close to me, and I dared do nothing of the sort. I knew well that she was half playing with me, that she permitted herself this badinage because she had decided rightly or wrongly that I was a person to be trusted.

"If I dared to ask all that I would wish to claim," I said, earnestly, "I am afraid that you would say that my service was not worth the price."

An incomprehensible smile played about her lips. I have often wondered since exactly what she was thinking of at that moment.

"Supposing," she suggested, softly, "that we waive the question of incentive—or reward."

"I will willingly leave it," I said, "to your generosity."

She sighed. Her tone when she spoke again was more practical. I felt that a delightful little interlude was over.

"To go back to my plan," she said. "What I want you to do is very simple. I want you to transform yourself into one of those creatures who go about and report on mines—experts you know."

I looked at her steadily.

"Ah!" I said.

"In fact," she continued, "so far as my father and the Count are concerned, you are one already. I told them that your real name was Anderson, that I met you at Mrs. Murgatroyd's, and that you were something to do with mining. You must have noticed their sudden change of manner towards you."

"Yes," I admitted, "I noticed that."

"Of course," she continued, "you won't want to give yourself away all at once. Keep up the tourist as long as you can. But in the end I want you to let father think that you have been sent here by another syndicate to report upon the property, and that your decision is most unfavourable. That ought to stop him buying it, and, in short, that is my plan."

I remained silent. I felt her eyes upon me.

"Do you mind?" she asked timidly. "Is it too difficult? Or perhaps you don't like saying what isn't true?"

"I don't mind a bit," I assured her. "I think that your plan is wonderful, and I will do my best to carry it out."

"I shall never be able to thank you enough," she murmured. "Poverty is hard enough as it is, but destitution!"

I took her hand again. It was soft and cool, and faintly responsive. I felt that I would have lied till I was black in the face for her. But I wondered—

The Count was the first upon the field. He caught me smoking an early cigarette in the cobbled square of the little town, and at once waved his hand in friendly salute.

"Ah!" he cried, as though the sight of me were some unexpected boon conferred upon him by Providence. "It is Mr. Anderson, is it not? Good morning! Good morning!"

"My name," I answered, "is Shrive. John P. Shrive!"

The Count shrugged his shoulders. Suddenly he came close up to my side and looked round to be sure that we were alone.

"Come," he said, "you are an American; you are a people of great affairs; you like, I think, that one talks business with you. Whatever your name may be, you are here to make a report upon my mine—the Great Fortuna Mine. Is it not so?"

"My dear Count," I said, "I guess you are a long way off this time. I know no more about mines than a babe unborn. I'm junior partner and buyer in a firm of dry goods men in Boston, and I'm on my way to Genoa to buy silk. I just stopped over a day or so to get a bit of your country at first hand, and to see your pictures."

The Count listened to me with marked impatience, tapping his leg all the while with his long riding whip. When I had finished he smiled at me serenely.

"Very good, very good, my dear sir. I understand perfectly that it is necessary for you to act secretly. But I will be frank with you. The mine is as good as sold."

I was careful to let an instantly smothered little exclamation of dismay escape me. The Count heard it with a smile of triumph.

"To whom?" I asked.

"To the Englishman, Mr. Derwent," the Count answered promptly. "I am quite open with you—as you see. I cannot treat with your principals, whoever they may be."

"My principals," I answered, "don't buy mines. We deal in dry goods."

"Yes! Yes!" he ejaculated impatiently. "I know all about that. But let us talk like sensible men, eh? The mine being sold, your report is useless, is it not so? Come, you shall not have your labour for nothing. I will buy it from you."

"If the mine is already sold," I remarked, "of what value can my report be—supposing I have made one?"

"As good as sold," he interrupted. "It is the formalities only which await completion."

"Then I still do not see," I said, "of what value my supposed report could be."

The Count fixed me with his little black eyes.

"For the purposes of business," he said slowly, "no! It is not worth the paper on which it is written. But I will show you how frank I am. Mr. Derwent, he, too, knows that you are Mr. Anderson, the mining expert. He will come to you for your verdict. He will, perhaps, try to buy your report. Now, you have had no opportunity to inspect the property properly. It may be—I cannot tell—that you have even prepared an unfavourable report. If so I will buy it from you. I do not wish to cause the good Mr. Derwent any uneasiness."

"The uneasiness," I remarked, "will come later on."

"What you mean?" he asked, quickly.

"I know nothing about mines," I said. "I am a dry goods man. But somehow I don't take much stock in the Fortuna Mine."

"For how much you not say that again?" he asked. "Not any more at all. For how much you say it is a good mine?"

The little Count had got there at last. I pursed up my lips and stood as though thinking. The Count watched my face anxiously.

Fortunately for me intervention came in the shape of Mr. Derwent and his daughter, who called to us from the front of the hotel. I could not but admire the ease and grace with which the Count cloaked his annoyance. He took me by the arm and let me across the square, all smiles and bows.

"For how much, dear friend?" he whispered in my ear.

I shook my head.

"You're rushing this a bit, Count," I answered. "I'll think it over."

The Count muttered something which sounded very much like "damn," but was probably something worse. A moment afterwards we were shaking hands with the Derwents.

Miss Derwent, in a broad-brimmed picture hat trimmed with roses, and a white flannel gown, looked more charming than ever. Her greeting, too, with its delicate insinuation of our secret understanding, was exactly what I had looked for. She had talked to me in undertones of the beauty of the place, the clearness of the sky, the wonderful early sunlight in which the distant vine-covered hills were bathed. But of the other things which lay between us she made no mention, nor did she attempt in any way to draw me apart from the others.

Our déjeuner—I seemed to be included in the meal as a matter of course—was quite a success. The Count chatted gaily and well of the beauties of the country where, he told us, with a little burst of pardonable pride, his family had ruled for ten centuries. He spoke of art and the things appertaining to it with the ease and fluency of one who was master of his subject. Of his mine, too, he spoke vaguely as the repository of hidden treasures which would long ago have been dragged to light but for his love of the quiet countryside.

"You English," he said, "and you," he added, addressing me, "you do not understand that feeling. It is well for you that you do not. You are a utilitarian people. It is you who work hand-in-hand to-day with the great forces of the world. But with us here it is different. We are guilty of the terrible weakness of leaning upon our past. The people round here are my people. I want to see them husbandmen and wine-growers, not miners with pale faces, sowing the seeds of weakness in the next generation. I love to see my hillsides covered with vineyards as they have ever been. I do not love the tall shafts, the roar of machinery, the country made black and scarred with the entrails torn out of the earth. And yet these things must come," he murmured, leaning back and lighting a cigarette. "For many years I have struggled against it, but no longer. Ah, it is not possible."

I looked across at the Count with unfeigned admiration. His beautiful eyes were filled with sadness. He leaned back in his chair, looking out upon the distant hillside as though already those shafts had come into existence. Miss Derwent permitted herself the faintest of smiles as she glanced across at me. Mr. Derwent seemed intent upon the great dish of strawberries which the Count had sent down from his own villa.

After breakfast we were served with coffee and some delicate green liqueur, and then Mr. Derwent took his hand in the game. He began by moving his chair close to mine, and making clumsy efforts to get rid of the Count and his daughter. At this sort of game the Count was his master, and with very faint help from Veronica (I knew her name now), his attempts for some time were unsuccessful. At last, however, in obedience, as I suspect, to a vigorous under-the-table injunction from her father, Veronica rose languidly to her feet.

"I am afraid," she said, "that I am in an extravagant frame of mind this morning. After all, I think that I must have that ivory cross. Count, will you come and interpret for me?"

The Count rose to his feet with much less than his usual gallantry.

"Will you not charge me with the commission, signorina," he said. "My shop-people, when they see an English lady or an American, are, I fear, inclined to be exorbitant. Leave it to me, and I will promise you the cross at much less cost."

Veronica hesitated. Mr. Derwent interposed.

"Nonsense, my dear!" he exclaimed. "I have seen the cross, and I think the price very reasonable. Go with the Count at once and secure it. I insist! It is only fair that we should spend a little money in a town where we have been so well entertained."

Veronica lifted her white skirts just far enough to show me a delightful little foot, and turned toward the Count. It was not possible for him to hesitate any longer. He made a vigorous effort, however, to include me in the party.

"You, too, Mr. Anderson," he said passing his arm through mine. "Oh, I insist. There are, indeed, some valuable curios to be seen. It is an opportunity which you must not miss."

I am convinced that Mr. Derwent would have detained me by main force had I not saved him the trouble. I rose from my chair as Veronica passed, but excused myself with some emphasis.

"Sorry, Count," I said, "but I'm afraid I'm very unlike most of my countrypeople in that respect. I've no use for curios. I like my ornaments and my furniture clean and modern. I'll keep Mr. Derwent company."

The Count threw me a look over his shoulder, evidently intended to remind me of our uncompleted bargain. Veronica nodded to me from underneath her parasol, and crossed the square at a pace which the Count must have found maddeningly slow. Mr. Derwent leaned over towards me and opened the ball straight off.

"I—er—was hoping to have a few minutes' conversation with you this morning, Mr. Anderson," he said, slowly adjusting his eye-glass. "From something which my daughter let drop in—er—the course of conversation, I gathered that you were to some extent interested in—in short, in mining properties."

"You wanted to ask me," I suggested, "about this mine of the Count's?"

"Exactly!" he admitted. "Now I am free to confess that I am not a mining expert. I came out to have a look at the property, meaning—er—to have an independent opinion in case I thought it likely to interest me. I find, however, that there is no room for any delay in the matter. Our good friend the Count—very decent, hospitable sort of fellow he seems—is, between ourselves, hard pressed. He means to sell, and to sell at once. He says that his brother is even now in London with a power of attorney. However that may be, it is certain that I have no time to get an expert out. I must rely upon my own judgment and the Count's honesty."

"Of the two—" I murmured.

"Eh?" Mr. Derwent interrupted.

I stirred my coffee vigorously and disclaimed speech. Mr. Derwent glared at me from behind his monocle.

"It occurred to me," he went on, "that you might in this dilemma be inclined to help me with a word of advice. I am aware," he went on with a little wave of the hand, "that such a course is a little unusual. I refrain from asking you any personal questions. What your position here may be I do not know. I do not enquire. It is not my business. You may be—er—representing other interests. I will take my risk of that. I have ventured to make out this cheque for one hundred guineas;" he pushed it towards me. "Consider me for the moment as a client. Is the Great Fortuna Mine worth twenty-thousand pounds?"

I tore the cheque into small pieces. "It is not worth twenty-thousand pence," I answered.

He suddenly dropped his eye-glass and leaned forward. I scarcely knew him. A certain vagueness of expression was gone. He spoke and looked like a wide-awake astute man.

"Come," he said, "I don't like your tearing that cheque up. You could have given me value for the money, and no man should be ashamed to take what he has earned."

"No man," I answered, "can serve two masters. That's a mighty true saying, Mr. Derwent."

"There's only one thing I'm afraid of about you," he said, eyeing me keenly. "I can't be altogether sure that Veronica hasn't been getting at you."

"Do you allude," I asked guardedly, "to your daughter?"

He ignored my question, but I could see that his suspicions were growing.

"For some reason or other," he remarked thoughtfully, "Veronica is dead set against this deal. I never knew her to interfere in a business matter before. I can't understand it at all."

"Your daughter," I said gravely, "may surely be pardoned if she takes some interest in a matter concerning her so closely."

"But for the life of me," he protested, "I cannot see how it does concern her."

"Speculations such as this," I said severely, "may be the pastime of the rich; but to gamble with the shreds of one's fortune is unpardonable."

He looked at me in amazement.

"You—I—but you must be acquainted with my daughter, I suppose. You must have some idea of what you are talking about?"

"Naturally," I answered tersely.

"Then upon my word, for an intelligent young man," he said, "you're about the best hand at talking nonsense I've come across."

"You ought to be a judge," I answered. "However, for your daughter's sake, here's the best and safest tip you've ever had. Let the mine alone."

"I'm inclined to think you're right," he admitted with a sigh. "It is a risk, especially if your people, whoever they might be, are 'bears.' I hate to come all this way and do no business, though."

"Why don't you stay at home, then," I said, severely, "and for your daughter's sake put the little you have in a good railroad stock?"

He set down the liqueur glass which he had been in the act of raising to his lips, and looked at me for a moment in utter astonishment. Then he leaned back in his chair and laughed till the tears came into his eyes.

"I don't know who you are," he said weakly, "but you're the funniest young man I ever came across. Never mind. I believe you're right about the mine. We'll start back to London this morning."

I was perhaps as astonished as he was, but I said nothing, for the Count and Veronica were close at hand. The former looked at us both anxiously.

"Come," he called out, "we have triumphed. The ivory cross is ours. And now, if you are ready, Mr. Derwent, my carriage is here. The notary will be at my villa in an hour's time."

Mr. Derwent rose to his feet.

"One moment, Count," he said.

They stepped aside. Veronica turned to me. There was the most becoming little pink flush upon her cheek.

"Well?" she exclaimed.

"I think that your father is persuaded," I said. "He will not buy. He is telling the Count so now."

She laughed softly.

"My friend," she said, "I shall be for ever in your debt."

"I would rather," I answered, "that you paid."

She looked at me and down at her feet.

"He would have signed last night," she said, "if I had not invented you."

The Count and Mr. Derwent came towards us. The former was pale with rage. I am convinced that nothing but the arrival of a telegraph message at that instant prevented his assaulting me. He tore open his message, and as he read he became a changed man.

"Alas!" he exclaimed, turning towards Mr. Derwent with ill-concealed triumph, "I can no longer argue this matter with you. Your time was up last night. You have exceeded it, and, behold, the mine is no longer mine to deal with. It is sold."

Mr. Derwent looked sharply at me.

"Sold to whom?" he asked.

The Count shrugged his shoulders.

"It is my brother in London who has arranged the matter," he said. "He has power of attorney, and he has received the money. The purchaser is a Mr. Charles Ellicot."

Mr. Derwent looked at his daughter.

"What do you know about this, Veronica?" he asked.

"Tell you presently, father," she answered. "Just at present I want to talk to Mr. Anderson. Please come here."

I followed her obediently round the hotel to the gardens in the rear. She made me sit down, and took the seat next to mine. As though afraid that I might seek to escape, she laid her hand upon mine. It was not necessary.

"First of all," she began, boldly, "I'm engaged to Charlie."

I held her hand tightly. I was not capable of articulate speech just then.

"Father wouldn't hear of it," she went on. "He said that Charlie was too poor, and had never done anything. He didn't believe in Charlie. I did."

She paused. I think she found my silence a little disconcerting.

"Charlie heard of this mine," she went on. "He sent over two experts and got two magnificent reports. Then he sent about trying to raise the money to buy it. Unfortunately, father heard about the mine too, and he decided to come over and look at it. I came with him to try to stop his buying it, if I could. All the time Charlie was trying to raise the money in London. Yesterday he wired me, 'All promised. Shall conclude to-morrow.' I was almost at my wit's end, for father had arranged to conclude the purchase last night."

"This is where I come in, I suppose," I remarked feebly.

She nodded.

"They really put the idea into my head," she said. "My father wondered whether you were not here in connection with the mine, and the Count looked mysterious and smiled to himself. So I spoke to you last night, and afterwards I told them that you were a mining-engineer. That put father off at once, for he saw a chance of getting an expert opinion."

"He had it," I murmured.

"It was awfully sweet of you," she declared. "You see how beautifully it has all come off!"

"Then it wasn't your father's last twenty-thousand pounds!" I remarked, suddenly.

"Of course not," she murmured. "My father is really Lord Derwent. He prefers to travel incognito because people bother him so."

For a moment the humour of this thing possessed me. I recalled my sound advice to a multi-millionaire, and I laughed till the tears stood in my eyes. Suddenly I remembered that I, too, had a confession to make.

"By-the-by," I said slowly, "did you say that your—your friend—"

"Charlie," she murmured.

"Had had two favourable reports on the mine?"

"Yes."

"And has bought it?"

She nodded. I looked at her sympathetically. After all, it was impossible for her marry a pauper.

"I am very sorry to hear it," I said hypocritically. "Perhaps the most extraordinary part of this affair is that I am really a mining engineer, and have been preparing a secret report upon this property."

She looked at me in amazement.

"Are you in earnest?" she asked.

"I am sorry to say I am," I answered. "I came over on behalf of a New York syndicate, and I posted my report to them last night. I told your father the literal truth. The Great Fortuna Mine is not worth twenty thousand pence."

"What a fraud the Count is," she sighed, "and what a lot of money people will lose."

"Yes, but Charlie!"

She laughed softly.

"Oh, it makes no difference to Charlie," she said. "I believe he had to pay an awful lot of money for those favourable reports, but he's sold out to a syndicate for a hundred-thousand pounds. He got the signatories and raised the money of them to buy the mine. The syndicate will sell to a company, and, of course, the public who buys shares will be the people who will lose their money. I think Charlie's quite clever, don't you?"

"I should imagine there's no doubt about it," I assured her.

We sat for a few minutes in silence. Our hands were still very close together. I was feeling exceedingly depressed.

"We spoke," I remarked, "of something in the nature of a reward."

"It is quite true," she admitted. "You have earned it. Please sit still."

She rose to her feet and bent over me.

"Close your eyes," she whispered.

I obeyed her. To this moment I can remember the touch of the sun upon my shut eyelids, the rustling of the soft, lazy air through the orange trees, the drowsy humming of bees in the garden. I felt her face close to mine—and suddenly the touch of her lips, one whispered word in my ear! I had had my reward.

For a second I remained there, motionless. I lacked the power or the will to tear myself away. Then with a little cry I sprang to my feet and hurried round the corner of the hotel. I was too late. The hotel omnibus, laden with luggage, was rumbling across the square, the Count stood upon the pavement waving a florid farewell. A little white hand flashed out of the window. It was the last I ever saw of Veronica.

But one morning, some two months later, I received a packet in an unfamiliar handwriting. When I opened it I found one hundred shares in the Great Fortuna Silver Mine, and a little scrawl of paper:

"Charlie says these are very good to sell—quickly!"

THE woman sat alone in her dressing-room. For the second act, her costume needed no change—a dash of powder, a trifling rearrangement of the hair, had completed in a few seconds her necessary preparations. She had dismissed her maid, and denied herself to a lady journalist who represented a fashion paper, and wanted to talk about her dresses. She felt the need of solitude.

The girl with the large dark eyes— who was she? Had she been looking into a mirror, back down the long avenue of years to the days of her own girlhood, when she, too, had gazed out upon life with, something of the same mysterious wonder? Fashions move always in a circle. She, too, had twisted her hair somewhat in that fashion, had worn a rose instead of a ribbon, had sought with something of the same almost plaintive eagerness to understand, if only dimly, the life which throbbed on every side of her.

Who was she? A ghost? An actual unit of the audience, a living and breathing person, or a creature of the fancy only? The violins of the orchestra swayed less and less, the music died away. There was silence, and then the tinkling of a little bell. The curtain had risen.

In a few minutes, she was on the stage again, face to face with a situation round which, even in these days of the play's assured success, controversy raged fiercely. A false note, and daring became grossness; a gesture, even a look, and the forbidden was manifest. To conceal it utterly was the most exquisite triumph of art. That night, perhaps for the first time in her life, the woman wholly succeeded.

Again the curtain fell amidst a storm of applause, and again the woman sat abstracted and thoughtful in her dressing-room. This time she was not left undisturbed. A man came in to her, tall, graceful, but with the tired face and wrinkled brows of premature age.

She took no notice of his entrance. He paused to light a cigarette.

"I congratulate you," he remarked, drily.

"Upon what?"

"Your versatility. You have given a new rendering of Mona to-night. You have stripped her of the flesh, lifted her wholly off the clogging earth. But I warn you, Emily, the critics won't like it."

"The critics!"

"People are so like sheep. They need some one to direct them. They do not see the ass's skin, only the mantle of the prophet. And our friends of the press do not like to be trifled with."

The woman sat still, with her back to him. The perfume of his cigarette, his presence in her room, the easy nonchalance of his manner, stung her.

She still looked into the mirror, and still she saw the same things.

"I must play the part," she said, in a low tone, " as I feel it."

"Is not that," he remarked, holding his cigarette thoughtfully between his fingers, "a little hard upon those who have to play up to you? Last night you were flesh and blood, the arrogant courtesan, a marvelous creation. You almost frightened me with the reality of it, and one could hear the audience holding their breaths—it was supreme. To-night you rise phoenix-like to a virtue which holds evil things abashed. If you are the actual courtesan, you are also the embodiment of all the opposite things in life. It may be a triumph in originality—your rendering, I mean—but it is deuced uncomfortable for me."

The woman smiled, faintly. She understood quite well the reason of his annoyance. He was the puppet-actor, born of the times, only possible in this period of uninspired plays, a man of graceful presence and musical voice, who owed his position to these things, and these things only. The genius that made it possible for her suddenly to purify a situation which it was rumored had worried the King's censor, had fired no answering impulse in his slower wits. His acting had been constrained and unimpressive. He had felt himself at sea, and he had shown it. Man-like, he was aggrieved. He had been robbed of his meed of applause, the only stimulant not wholly physical which appealed to him. This was the hundredth night, too, and the critics were in the stalls.

"I am glad that you felt the change," the woman said, slowly. "Why not adapt yourself to it?"

"Why change?" he answered, irritably. "The piece went well enough before. You seem to be trying to transform a magnificent piece of realism into an idyll. At this theatre, we do not play to school-children."

She abandoned the subject a little abruptly. It did not interest her to discuss these things with him.

"I wonder," she said, "if you know who some people are, in the third row of the stalls—two elderly ladies, rather oddly dressed, and a child with large eyes."

He prided himself upon knowing everybody, and he did not fail her.

"Two old maids from the wilds of Scotland, and their niece," he answered. "Nugent Campbell, their name is, I think—the girl's father is the Sir Henry Nugent Campbell who did so well out at the war. Beautiful eyes, hasn't she?"

He was examining himself negligently in the mirror; the fold of his tie did not altogether please him, or was it his pin that was a trifle crooked? Presently, however, he glanced toward her. She was sitting quite still, and her hands were clasping the arms of the chair. The natural pallor of her complexion seemed intensified. There were things in her face which he did not understand.

"You're seedy, Emily," he exclaimed. "Let me ring for your woman. Have some wine, will you?"

She moved her head toward the door.

"Go away!" she said.

"Nonsense! I can't leave you like this. The curtain will be up in five minutes. Let me get you a glass of champagne."

"Cannot you see that I wish to be alone?" she said. "I am quite well. Please go away."

He shrugged his shoulders and departed, closing the door behind him.

From outside came a momentary wave of strangely mingled sounds, the shifting of heavy scenery, the murmur of conversation from the audience, of muffled laughter from the wings, the throbbing of violins from the orchestra. Then the door closed, and there was silence. The woman rose swiftly, and turned the key in the lock.

The duke stopped his sisters on their way out. He addressed them with a severity which was belied by the twinkle in his eyes.

"Amelia!" he exclaimed. "I am astonished. Fancy bringing the child to see a play like this!"

Amelia, who had had qualms, looked at him, anxiously.

"I am very sorry, Robert, but I had no one to consult, and they assured me at the library that it was quite the thing to see. If you had kept your promise and come in to tea yesterday afternoon, I had a list of plays which I had intended to submit to you."

"You mustn't scold aunt," the girl declared, smiling up at him. "I have never enjoyed anything so much in my life. If only it were not so sad!"

"You were lucky to-night, anyhow," he remarked. " I have never seen Emily Royce act like that before."

"She is beautiful," the girl murmured. " How I should love to see her off the stage!"

The duke hesitated, and then laughed to himself.

"You shall," he said. "I'm going behind. Hundredth-night celebration, you know, and I'll take you if you like."

The girl's eyes were bright with joy.

"Auntie, do you hear?" she exclaimed. "Isn't it glorious? Do you mean that I shall really see her to speak to?"

"Robert! You are joking, of course," Miss Amelia exclaimed. "You do not seriously propose to take that child behind the scenes?"

He smiled. "Why not? I'll take all of you. Huntingdon will be delighted, and it's quite the thing to do, I assure you. Your friend, Lady Martin, and her daughters have gone."

Miss Amelia sighed. "I am sorry to disappoint Esther," she said, "and I do not dispute what you say, Robert, but I cannot part with all my old prejudices so easily. I do not approve of the theatre. I will not sacrifice my principles to the extent of accepting hospitality from the ladies and gentlemen who have been kind enough to amuse us."

The duke nodded his head approvingly. He thoroughly enjoyed his sisters.

"Quite right," he remarked, "quite right. Never mind, Esther," he added, seeing her gallant effort to hide her disappointment, "I'll take you. You'll find my carriage outside, Amelia. Take it home, and send it back to the stage door for us. I'll look after Esther."

"You dear!" the child exclaimed, clinging to his arm. "You don't mind, Aunt Amelia?"

Miss Amelia sighed. "Your uncle would not suggest anything unbefitting, my dear," she said. "Our approval is, of course, quite another matter."

So, presently, Esther found herself in the strangest place she had ever imagined in her life. She was on the stage, shut off now from the house by the drop-curtain, and thronged with crowds of men and women in evening dress. Servants in livery were handing round champagne and sandwiches; all present seemed to be talking a great deal, and enjoying themselves immensely. Leverson caught sight of the new-comers presently, and came hurrying up.

"A little niece of mine from the wilds of Scotland, Leverson," the duke remarked. "Stage-struck, of course. I've brought her to see what ordinary people you all are with your war-paint off. Mr. Arthur Leverson, Miss Nugent Campbell."

The child was shy at first, but Leverson laid himself out to amuse her, and it was very easy. He showed her how the lime-light was worked, and explained the moving of the scenery.

They were standing a little apart, talking, when Emily Royce came in.

"Oh, I wonder—!" the girl exclaimed, eagerly.

He looked down at her with an amused smile.

"Well?"

"Could I—would she speak to me just for a moment?"

He was a little annoyed, but he hid it admirably.

"Of course. I'll take you to her."

Emily spared him the effort. She detached herself from a little group, and came toward them. Leverson murmured the girl's name.

"I saw you in front, didn't I?" Emily said, smiling. "Somehow, I fancied that the theatre was almost a new place to you. Was I right?"

"Absolutely," the child answered.

She was no longer in the least shy. No one had ever looked at her quite so kindly as this wonderful woman.

"I have never been inside the theatre before," Esther admitted. "My aunts are—a little old-fashioned, and we live so far off from everywhere.

"Go and talk to the Esholts, Mr. Leverson," Emily said. "I am going to take possession of Miss Campbell for a little time."

Leverson withdrew with a subdued grumble meant to sound good-natured, but not altogether successful. Emily made the girl sit down on a lounge by her side.

"I noticed you quite at the beginning of the play," she said, smiling. "You seemed so absorbed, and you know we people on the stage love to act to people who are interested."

"I think it is marvelous," the child said, still a little shyly, "to think that any one can act like you do. I can scarcely believe that I am really here talking to you."

"Tell me about your home in Scotland, and your life there," Emily said. "Do you mind? I should so like to hear about it all."

The child was ready enough to talk. She spoke of the old, gray castle, with its prim, well-ordered life; the wonderful hills, with the mystery of their inaccessible, mist-wreathed summits; the deep, tree-hung glens; the salmon river which came rushing down from some hidden spot; the purple moors always so lonely, and growing bleaker and bleaker as they rolled away northward. The woman by her side smiled and listened and prompted her every now and then with some questions. Behind it all was the strange background of gay conversation, the popping of corks, the ceaseless hurrying hither and thither of servants.

"You have very few friends, then?"

"Very few. My aunts are not fond of strangers or visitors. Sometimes it is very dull, especially when the rains come, and the whole country is hidden in mists."

"But your father—is he never with you?"

The girl shook her head, gravely.

"Very, very seldom. He is a soldier, you know, and he is always away fighting somewhere. I think that he does not like being at home."

The girl's eyes, very grave and steadfast, were suddenly troubled. Something in the set immobility of Emily's features chilled her.

"I am afraid," she said, "that I am wearying you. I do not know why I have talked so much of my little concerns, when I Would so much rather have had you tell me about your own wonderful life."

Emily shook her head. The faint smile which parted her lips was at least reassuring.

"You do not know how interested I have been," she said. "Some day, I hope that we shall have another talk."

"We are in London for two months," Esther said. "Might I come and see you?"

"I think—we must see," was the unexpectedly evasive answer. "I shall write to you."

A man who had just come in looked at the pair for a moment or two with a curious expression. Then he went up to the duke.

"Ernham," he said, "did you bring your niece here?

"By Jove, I did, and I've forgotten all about her," the duke answered. "Where is she?

"Sitting on the sofa there, talking to Emily Royce. You had better take her home."

The duke raised his eyebrows.

"Why?"

"Do you know what Emily Royce's name was when she first came on the stage?"

"No idea," the duke admitted, cheerfully. "Never can remember those things."

"Some one might have reminded you," his friend remarked. "It was Emily Heddon."

The duke was staggered. He looked toward the couch. This was the woman, then, whom his brother had married, and Esther—

"Great heavens!" he muttered.

"Esther, I am sorry to interrupt you, but we must go at once," he added, a moment later.

The girl held out her hand to Emily. "Good-bye," she said, simply. "I hope that I shall see you again." She felt the touch of her fingers warmly enough returned, but for some reason Emily was silent.

II

THEY were sitting together in the Park—not for the first time. The girl looked very sweet and fresh in her plain muslin gown and large hat, but her clear eyes were a little troubled.

"You are so much older and wiser than I am," she said, "that I suppose you must be right. But I do not like it. I do not think I can come any more."

"But how else can I see you?" he protested. "You know that your aunts dislike the stage and everything connected with it. They would never allow me to visit them."

"It is very perplexing," she admitted. "Aunt Amelia is really very kind to me, but—"

"Perhaps," he whispered, leaning over toward her, "you do not want to see me any more."

She looked at him a little shyly. Her eyes were full of reproach. She was adorably pretty."

"It is not kind of you to say that," she murmured, "because you know that I do."

He touched her fingers for a moment, and she felt a guilty thrill of joy, inexplicable, wonderful. He had had so much experience in these matters, every little move was known to him.

He began to talk, and she to listen, the color coming and going in her cheeks, a whole world of new emotions roused, quivering into life by the soft, passionate words which came so readily to his lips. Of course, he triumphed. It was a foregone conclusion, the battle altogether too one-sided. Soon he was walking by her side toward the gates.

A victoria was stopped close to them, and a woman all in white descended. She was paler even than the chiffon which hung from her parasol, but her eyes seemed lighted with smoldering fire. Leverson swore under his breath. Even Esther felt that there was something inappropriate in the glad little cry of welcome which sprang to her lips.

"How fortunate that I should see you both!" Emily exclaimed. "Miss Campbell, I want you to do me a favor. I want you to jump straight into my carriage, and let my people take you home."

"Alone?" the child exclaimed. "But you are coming, too! May I not drive with you?"

Emily shook her head. She denied herself a great deal.

"The carriage will return for me here," she answered. "I have something particular to say to Mr. Leverson."

Mr. Leverson did not seem at all enchanted at the prospect. His appearance was, to say the least, sulky. Nevertheless, his protest was almost inarticulate, and Emily simply turned her back upon him. She saw the child into the little victoria, and waved her hand in adieu. Then she returned to Leverson. They stood face to face upon the broad path.

"My friend," she said, drily, "I hope you will believe that your flirtations and liaisons, of which I am told you are somewhat proud, are, in a general way, matters of supreme unimportance to me. In this particular case, however, I have something to say. I insist upon it that you discontinue your clandestine meetings and all correspondence with that child."

There were times when Leverson was not handsome, and this was one of them. His manner was shifty, his indignation petulant.

"Really, Mrs. Royce," he said, "I scarcely see that our relations are such as to give you the right to dictate to me in such matters."

She smiled, faintly. She had been the humiliation of his life of amours, and she knew it.

"We will not discuss that," she answered. "I know you through and through, Arthur Leverson, and I am going to appeal to your only vulnerable spot—your self-interest. You obey my wishes in this matter, or you leave the theatre."

"You are not serious?" he exclaimed.

"I am very serious indeed. I can do without you—you cannot do without me. Our play is the biggest success London has known for years, and your share in it is not worth a snap of the fingers. Yet you share with me the honors and the profit. So it shall continue unless you disobey my wishes in this matter. If you meet or speak to that child again unchaperoned, you go."

"This is monstrous!" he exclaimed. "I have a vested right in the play."

"You might force me to withdraw it," she answered, "but that would not trouble me in the least. I am a rich woman."

He turned on his heel with a little exclamation, and walked away. Emily sat down and waited for her carriage. The immediate effect of Emily's intervention was the following note duly delivered at Leverson's rooms on the next evening:

16, MERSHAM STREET, W.

MY DEAREST,