a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Tennyson Author: G. K. Chesterton and Dr. Richard Garnett * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1300301h.html Language: English Date first posted: Jan 2013 Most recent update: Jan 2013 This eBook was produced by: Colin Choat and Roy Glashan Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

In this edition of Tennyson the illustrations printed in the first edition have been replaced by a combination of digitally enhanced versions of the original images and higher-quality pictures from other sources. Links to the footnotes at the end of the book have been added to the text. The biography has been expanded by the inclusion of a gallery of twenty pictures painted by Helen Allingham and reproduced, with notes by the artist, in the book The Homes of Tennyson, published by Adam and Charles Black, London, in 1905.

IT was merely the accident of his hour, the call of his age, which made Tennyson a philosophic poet. He was naturally not only a pure lover of beauty, but a pure lover of beauty in a much more peculiar and distinguished sense even than a man like Keats, or a man like Robert Bridges. He gave us scenes of Nature that cannot easily be surpassed, but he chose them like a landscape painter rather than like a religious poet.

Above all, he exhibited his abstract love of the beautiful in one most personal and characteristic fact. He was never so successful or so triumphant as when he was describing not Nature, but art. He could describe a statue as Shelley could describe a cloud. He was at his very best in describing buildings, in their blending of aspiration and exactitude.

He found to perfection the harmony between the rhythmic recurrences of poetry and the rhythmic recurrences of architecture. His description, for example, of the Palace of Art is a thing entirely victorious and unique. The whole edifice, as described, rises as lightly as a lyric, it is full of the surge of the hunger for beauty; and yet a man might almost build upon the description as upon the plans of an architect or the instructions of a speculative builder. Such a lover of beauty was Tennyson, a lover of beauty most especially where it is most to be found, in the works of man. He loved beauty in its completeness, as we find it in art, not in its more glorious incompleteness as we find it in Nature.

There is, perhaps, more loveliness in Nature than in art, but there are not so many lovely things. The loveliness is broken to pieces and scattered: the almond tree in blossom will have a mob of nameless insects at its root, and the most perfect cell in the great forest-house is likely enough to smell like a sewer. Tennyson loved beauty more in its collected form in art, poetry, and sculpture; like his own "Lady of Shalott," it was his office to look rather at the mirror than at the object. He was an artist, as it were, at two removes: he was a splendid imitator of the splendid imitations. It is true that his natural history was exquisitely exact, but natural history and natural religion are things that can be, under certain circumstances, more unnatural than anything in the world.

In reading Tennyson's natural descriptions we never seem to be in physical contact with the earth. We learn nothing of the coarse good-temper and rank energy of life. We see the whole scene accurately, but we see it through glass. In Tennyson's works we see Nature indeed, and hear Nature, but we do not smell it. But this poet of beauty and a certain magnificent idleness lived at a time when all men had to wrestle and decide. It is not easy for any person who lives in our time, when the dust has settled and the spiritual perspective has been restored, to realise what the entrance of the idea of evolution meant for the men of those days. To us it is a discovery of another link in a chain which, however far we follow it, still stretches back into a divine mystery.

To many of the men of that time it would appear from their writings that it was the heart-breaking and desolating discovery of the end and origin of the chain. To them had happened the most black and hopeless catastrophe conceivable to human nature; they had found a logical explanation of all things. To them it seemed that an Ape had suddenly risen to gigantic stature and destroyed the seven heavens. It is difficult, no doubt, for us in somewhat subtler days to understand how anybody could suppose that the origin of species had anything to do with the origin of being. To us it appears that to tell a man who asks who made his mind that evolution made it, is like telling a man who asks who rolled a cab-wheel over his leg that revolution rolled it.

To state the process is scarcely to state the agent. But the position of those who regarded the opening of the "Descent of Man" as the opening of one of the seals of the last days, is a great deal sounder than people have generally allowed.

Click here for more information

It has been constantly supposed that they were angry with Darwinism because it appeared to do something or other to the Book of Genesis; but this was a pretext or a fancy. They fundamentally rebelled against Darwinism, not because they had a fear that it would affect Scripture, but because they had a fear, not altogether unreasonable or ill-founded, that it would affect morality. Man had been engaged, through innumerable ages, in a struggle with sin.

The evil within him was as strong as he could cope with—it was as powerful as a cannonade and as enchanting as a song. But in this struggle he had always had Nature on his side. He might be polluted and agonised, but the flowers were innocent and the hills were strong. All the armoury of life, the spears of the pinewood and the batteries of the lightning, went into battle beside him. Tennyson lived in the hour when, to all mortal appearance, the whole of the physical world deserted to the devil.

The universe, governed by violence and death, left man to fight alone, with a handful of myths and memories. Men had now to wander in polluted fields and lift up their eyes to abominable hills. They had to arm themselves against the cruelty of flowers and the crimes of the grass.

The first honour, surely, is to those who did not faint in the face of that confounding cosmic betrayal; to those who sought and found a new vantage-ground for the army of Virtue. Of these was Tennyson, and it is surely the more to his honour, since he was the idle lover of beauty of whom we have spoken. He felt that the time called him to be an interpreter. Perhaps he might even have been something more of a poet if he had not sought to be something more than a poet. He might have written a more perfect Arthurian epic if his heart had been as much buried in prehistoric sepulchres as the heart of Mr. W. B. Yeats. He might have made more of such poems as "The Golden Year" if his mind had been as clean of metaphysics and as full of a poetic rusticity as the mind of William Morris. He might have been a greater poet if he had been less a man of his dubious and rambling age. But there are some things that are greater than greatness; there are some things that no man with blood in his body would sell for the throne of Dante, and one of them is to fire the feeblest shot in a war that really awaits decision, or carry the meanest musket in an army that is really marching by. Tennyson may even have forfeited immortality: but he and the men of his age were more than immortal; they were alive.

Tennyson had not a special talent for being a philosophic poet, but he had a special vocation for being a philosophic poet. This may seem a contradiction, but it is only because all the Latin or Greek words we use tend endlessly to lose their meaning.

Click here for more information

A vocation is supposed to mean merely a taste or faculty, just as economy is held to mean merely the act of saving. Economy means the management of a house or community. If a man starves his best horse, or causes his best workman to strike for more pay, he is not merely unwise, he is uneconomical. So it is with a vocation. If this country were suddenly invaded by some huge alien and conquering population, we should all be called to become soldiers. We should not think in that time that we were sacrificing our unfinished work on Cattle-Feeding or our hobby of fretwork, our brilliant career at the Bar or our taste for painting in water-colours. We should all have a call to arms. We should, however, by no means agree that we all had a vocation for arms. Yet a vocation is only the Latin for a call.

In a celebrated passage in "Maud," Tennyson praised the moral effects of war, and declared that some great conflict might call out the greatness even of the pacific swindlers and sweaters whom he saw around him in the Commercial age. He dreamed, he said, that if—

...The battle-bolt sang from the three-decker out on the

foam,

Many a smooth-faced, snub-nosed rogue would leap from his counter or

till,

And strike, were it but with his cheating yard-wand, home.

Tennyson lived in the time of a conflict more crucial and frightful than any European struggle, the conflict between the apparent artificiality of morals and the apparent immorality of science. A ship more symbolic and menacing than any foreign three-decker hove in sight in that time—the great, gory pirate-ship of Nature, challenging all the civilisations of the world. And his supreme honour is this, that he behaved like his own imaginary snub-nosed rogue.

His honour is that in that hour he despised the flowers and embroideries of Keats as the counter-jumper might despise his tapes and cottons. He was by nature a hedonistic and pastoral poet, but he leapt from his poetic counter and till and struck, were it but with his gimcrack mandolin, home.

Tennyson's influence on poetry may, for a time, be modified. This is the fate of every man who throws himself into his own age, catches the echo of its temporary phrases, is kept busy in battling with its temporary delusions. There are many men whom history has for a time forgotten to whom it owes more than it could count. But if Tennyson is extinguished it will be with the most glorious extinction. There are two ways in which a man may vanish—through being thoroughly conquered or through being thoroughly the Conqueror. In the main the great Broad Church philosophy which Tennyson uttered has been adopted by every one. This will make against his fame. For a man may vanish as Chaos vanished in the face of creation, or he may vanish as God vanished in filling all things with that created life.

G. K. Chesterton.

IT is easy to exaggerate, and equally easy to underrate, the influence of Tennyson on his age as an intellectual force. It will be exaggerated if we regard him as a great original mind, a proclaimer or revealer of novel truth. It will be underrated if we overlook the great part reserved for him who reveals, not new truth to the age, but the age to itself, by presenting it with a miniature of its own highest, and frequently unconscious, tendencies and aspirations. Not Dryden or Pope were more intimately associated with their respective ages than Tennyson with that brilliant period to which we now look back as the age of Victoria. His figure cannot, indeed, be so dominant as theirs.

The Victorian era was far more affluent in literary genius than the periods of Dryden and Pope; and Tennyson appears as but one of a splendid group, some of whom surpass him in native force of mind and intellectual endowment. But when we measure these illustrious men with the spirit of their age, we perceive that—with the exception of Dickens, who paints the manners rather than the mind of the time, and Macaulay, who reproduces its average but not its higher mood—there is something as it were sectarian in them which prevents their being accepted as representatives of their epoch in the fullest sense.

In some instances, such as Carlyle and Browning and Thackeray, the cause may be an exceptional originality verging upon eccentricity; in others, like George Eliot, it may be allegiance to some particular scheme of thought; in others, like Ruskin and Matthew Arnold, exclusive devotion to some particular mission. In Tennyson, and in him alone, we find the man who cannot be identified with any one of the many tendencies of the age, but has affinities with all. Ask for the composition which of all contemporary compositions bears the Victorian stamp most unmistakably, which tells us most respecting the age's thoughts respecting itself, and there will be little hesitation in naming "Locksley Hall."

Tennyson returns to his times what he has received from them, but in an exquisitely embellished and purified condition; he is the mirror in which the age contemplates all that is best in itself. Matthew Arnold would perhaps not have been wrong in declining to recognise Tennyson as "a great and powerful spirit" if "power" had been the indispensable condition of "greatness"; but he forgot that the receptive poet may be as potent as the creative. His cavil might with equal propriety have been aimed at Virgil. In truth, Tennyson's fame rests upon a securer basis than that of some greater poets, for acquaintance with him will always be indispensable to the history of thought and culture in England.

What George Eliot and Anthony Trollope are for the manners of the period, he is for its mind: all the ideas which in his day chiefly moved the elect spirits of English society are to be found in him, clothed in the most exquisite language, and embodied in the most consummate form. That they did not originate with him is of no consequence whatever. We cannot consider him, regarded merely as a poet, as quite upon the level of his great immediate predecessors; but the total disappearance of any of these, except Wordsworth, would leave a less painful blank in our intellectual history than the disappearance of Tennyson.

Beginning, even in his crudest attempts, with a manner distinctly his own, he attained a style which could be mistaken for that of no predecessor (though most curiously anticipated by a few blank-verse lines of William Blake), and which no imitator has been able to rival. What is most truly remarkable is that while much of his poetry is perhaps the most artificial in construction of any in our language, and much again wears the aspect of bird-like spontaneity, these contrasted manners evidently proceed from the same writer, and no one would think of ascribing them to different hands. As a master of blank verse Tennyson, though perhaps not fully attaining the sweetness of Coleridge or the occasional grandeur of Wordsworth and Shelley, is upon the whole the third in our language after Shakespeare and Milton, and, unlike Shakespeare and Milton, he has made it difficult for his successors to write blank verse after him.

Tennyson is essentially a composite poet. Dryden's famous verses, grand in expression, but questionable in their application to Milton, are perfectly applicable to him; save that, in making him, Nature did not combine two poets, but many.

This is a common phenomenon at the close of a great epoch; it is almost peculiar to Tennyson's age that it should then have heralded the appearance of a new era; and that, simultaneously with the inheritor of the past, perhaps the most original and self-sufficing of all poets should have appeared in the person of Robert Browning. A comparison between these illustrious writers would lead us too far; we have already implied that Tennyson occupies the more conspicuous place in literary history on account of his representative character.

The first important recognition of Tennyson's genius came from Stuart Mill, who, partly perhaps under the guidance of Mrs. Taylor, evinced about 1835 a remarkable insight into Shelley and Browning as well as Tennyson. In the course of his observations he declared that all that Tennyson needed to be a great poet was a system of philosophy, to which Time would certainly conduct him.

If he only meant that Tennyson needed "the years that bring the philosophic mind," the observation was entirely just; if he expected the poet either to evolve a system of philosophy for himself or to fall under the sway of some great thinker, he was mistaken.

Had Tennyson done either he might have been a very great and very interesting poet; but he could not have been the poet of his age: for the temper of the time, when it was not violently partisan, was liberally eclectic. There was no one great leading idea, such as that of evolution in the last quarter of last century, so ample and so characteristic of the age that a poet might become its disciple without yielding to party what was meant for mankind.

Two chief currents of thought there were; but they were antagonistic, even though Mr. Gladstone has proved that a very exceptional mind might find room for both. Nothing was more characteristic of the age than the reaction towards mediaeval ideas, headed by Newman, except the rival and seemingly incompatible gospel of "the railway and the steamship" and all their corollaries.

It cannot be said that Tennyson, like Gladstone, found equal room for both ideals in his mind, for until old age had made him mistrustful and querulous he was essentially a man of progress. But his choice of the Arthurian legend for what he intended to be his chief work, and the sentiment of many of his most beautiful minor poems, show what attraction the mediaeval spirit also possessed for him; nor, if he was to be in truth the poetical representative of his period, could it have been otherwise.

He is not, however, like Gladstone, alternately a mediaeval and a modern man; but he uses mediaeval sentiment with exquisite judgment to mellow what may appear harsh or crude in the new ideas of political reform, diffusion of education, mechanical invention, free trade, and colonial expansion.

The Victorian, in fact, finds himself nearly in the position of the Elizabethan, who also had a future and a past; and, except in his own, there is no age in which Tennyson would have felt himself more at home than in the age of Elizabeth. He does, indeed, in "Maud" react very vigorously against certain tendencies of the age which he disliked; but this is not in the interest of the mediaeval or any other order of ideas incompatible with the fullest development of the nineteenth century. If the utterance here appears passionate, it must be remembered that the poet writes as a combatant.

When he constructs, there is nothing more characteristic of him than his sanity. The views on female education propounded in "The Princess" are so sound that good sense has supplied the place of the spirit of prophecy, which did not tabernacle with Tennyson. "In Memoriam" is a most perfect expression of the average theological temper of England in the nineteenth century. As in composition, so in spirit, Tennyson's writings have all the advantages and all the disadvantages of the golden mean.

By virtue of this golden mean Tennyson remained at an equal distance from revolution and reaction in his ideas, and equally remote from extravagance and insipidity in his work. He is essentially a man of the new time; he begins his career steeped in the influence of Shelley and Keats, without whom he would never have attained the height he did—a height nevertheless, in our opinion, appreciably below theirs, if he is regarded simply as a poet. But he is a poet and much else; he is the interpreter of the Victorian era—firstly to itself, secondly to the ages to come. Had even any poet of greater genius than himself arisen in his own day, which did not happen, he would still have remained the national poet of the time in virtue of his universality.

Some personal friends—splendide mendaces—have hailed him as our greatest poet since Shakespeare. This is absurd; but it is true that no other poet since Shakespeare has produced a body of poetry which comes so near to satisfying all tastes, reconciling all tendencies, and registering every movement of the intellectual life of the period. Had his mental balance been less accurately poised, he might have been the laureate of a party, but he could not have been the laureate of the nation.

As an intellectual force he is, we think, destined to be powerful and durable because the charm of his poetry will always keep his ideas before the popular mind; and these ideas will always be congenial to the solid, practical, robust, and yet tender and emotional mind of England. They may be briefly defined as the recognition of the association of continuity with mutability in human institutions; the utmost reverence for the past combined with the full and not regretful admission that—

The old order changes, giving place to new,

And God fulfils Himself in many ways;

the conception of Freedom as something that "broadens down, from precedent to precedent"; veneration for "the Throne unshaken still," so long as it continues "broad-based upon the People's will," which will always be the case so long as

..... Statesmen at the Council meet

Who know the seasons.

Philosophically and theologically, Tennyson is even more conspicuously the representative of the average English mind of his day. Not that he is a fusion of conflicting tendencies, but that he occupies a central position, equally remote from the excesses of scepticism and the excesses of devotion. This position he is able to fill from his relation to Coleridge, the great exponent of the via media; not, as in former days, between Protestantism and Romanism, but between orthodoxy and free thought.

Tennyson cannot, indeed, be termed Coleridge's intellectual heir. As a thinker he is far below his predecessor, and almost devoid of originality; but as a poet he fills up the measure of what was lacking in Coleridge, whose season of speculation hardly arrived until the season of poetry was past.

Tennyson was but one of a band of auditors—it might be too much to call them disciples—of the sage who, curiously enough, had himself been a Cambridge man, and who, short and unsatisfactory as had been his residence at that seat of learning, seemed to have left behind him some invisible influence destined to germinate in due time, for all his most distinguished followers were Cantabs.

Such another school, only lacking a poet, had flourished at Cambridge in the seventeenth century, and now came up again like long-buried seeds in a newly disturbed soil. The precise value of their ideas may always be matter for discussion; but they exerted without doubt a happy influence by

Turning to scorn with lips divine

The falsehood of extremes,

providing religious minds reverent of the past with an alternative to mere mediaevalism, and gently curbing Science in the character she sometimes assumes of "a wild Pallas of the brain."

When the natural moodiness of Tennyson's temperament is considered, the prevalent optimism of his ideas, both as regards the individual and the State, appears infinitely creditable to him. These are ideas natural to sane and reflecting Englishmen, unchallenged in quiet times, but which may be obscured or overwhelmed in seasons of great popular excitement. The intellectual force of Tennyson is perhaps chiefly shown in the art and attractiveness with which they are set forth; even much that might have appeared tame or prosaic is invested with all the charms of imagination, and commends itself to the poet equally with the statesman.

Tennyson is not the greatest of poets, but appreciation of his poems is one of the surest criteria of poetical taste; he is not one of the greatest of thinkers, but agreement with his general cast of thought is an excellent proof of sanity; many singers have been more Delphic in their inspiration, but few, by maxims of temperate wisdom, have provided their native land with such a Palladium.

Richard Garnett.

Somersby Rectory, the birthplace of Alfred Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson was born on Sunday, August 6th, 1809, at Somersby, a village in North Lincolnshire between Horncastle and Spilsby. His father, the Rev. Dr. George Clayton Tennyson, Rector of Somersby, married in 1805 Elizabeth Fytche, daughter of the Vicar of Louth, in the same county; and, of their twelve children, Alfred was the fourth.

He always spoke with affectionate remembrance of his early home: of the woodbine trained round his nursery window; of the mediaeval-looking dining-hall, with its pointed stained-glass casements; of the pleasant drawing-room, lined with bookshelves and furnished with yellow upholstery. The lawn in front of the house, where he composed his early poem, "A Spirit Haunts the Year's Last Hours," was overshadowed on one side by wych-elms, on the other by larch and sycamore trees.

On the south was a path bounded by a flower-border, and beyond "a garden bower'd close" sloping gradually to the field at the bottom of which ran the Somersby Brook

That loves

To purl o'er matted cress and ribbed sand,

Or dimple in the dark of rushy coves,

Drawing into his narrow earthen urn

In every elbow and turn,

The filtered tribute of the rough woodland.

The charm and beauty of this brook haunted the poet throughout his life, and to it he especially dedicated, "Flow down, cold rivulet, to the sea." Tennyson did not, however, attribute his famous poem, "The Brook," to the same source of inspiration, declaring it was not addressed to any stream in particular.

Tennyson's Mother/ Somersby Church

Tennyson was exceedingly fortunate in the environment of his childhood and the early influence exercised by his parents. His mother was of a sweet and gentle disposition, and devoted herself entirely to the welfare of her husband and her children. Her son is said to have taken her as a model in "The Princess"; and he certainly gave a more or less truthful description of this "remarkable and saintly woman" in his poem "Isabel":—

Locks not wide-dispread,

Madonna-wise on either side her head;

Sweet lips whereon perpetually did reign

The summer calm of golden charity.

Tennyson's father was a man of marked physical strength and stature, called by his parishioners "The stern Doctor." In 1807 he was appointed to the living of Somersby, and that of the adjoining village of Bag Enderby, and this position he held until his death, on March 16th, 1831, at the age of fifty-two. He was buried in the old country churchyard, where "absolute stillness reigns," beneath the shade of the rugged little tower. In his time the roof of the church was covered with thatch, as were also those of the cottages in its immediate vicinity.

The livings of Somersby and Bag Enderby were held conjointly, service being conducted at one church in the morning and at the other in the afternoon. Dr. Tennyson read his sermons at Bag Enderby from the quaint high-built pulpit, Alfred listening to them from the squire's roomy pew.

Louth/The Grammar School, Louth

At the age of seven Tennyson was sent to school at Louth, a market-town which may fairly lay claim to having been a factor of some importance in his early life. His maternal grandmother lived in Westgate Place, her house being a second home to the young Tennysons. The old Grammar School where Alfred received the early portion of his education is now no longer in existence. Tennyson's recollections of it and of the Rev. J. Waite, at that time the head-master, were not pleasant. "How I did hate that school!" he wrote later. "The only good I got from it was the memory of the words Sonus desilientis aquae, and of an old wall covered with wild weeds opposite the school windows."

Tennyson's first connected poems were composed at Louth, and in this town also his first published work saw the light, appearing in a volume entitled "Poems by Two Brothers," issued in 1827 by Mr. J. Jackson, a bookseller. The two brothers were Charles and Alfred Tennyson.

After a school career which lasted four years, Alfred returned to Somersby to continue his studies under his father's tuition. This course of instruction was supplemented by classics at the hands of a Roman Catholic priest, and music-lessons given him by a teacher at Horncastle.

In 1828 Charles and Alfred Tennyson followed their elder brother Frederick to Trinity College, Cambridge. They began their university life in lodgings at No. 12, Rose Crescent, moving later to Trumpington Street, No. 57, Corpus Buildings. Of his early experiences of life at Cambridge, Alfred wrote to his aunt: "I am sitting owl-like and solitary in my rooms (nothing between me and the stars but a stratum of tiles). The hoof of the steed, the roll of the wheel, the shouts of drunken Gown and drunken Town come up from below with a sea-like murmur...The country is so disgustingly level, the revelry of the place so monotonous, the studies of the University so uninteresting, so much matter of fact. None but dry-headed, calculating, angular little gentlemen can take much delight in them."

Arthur Hallam (from the bust by Chantrey)

It was at Trinity College that Tennyson first made the acquaintance of Arthur Hallam, youngest son of the historian, whose friendship so profoundly influenced the poet's character and genius. "He would have been known if he had lived," wrote Tennyson, "as a great man, but not as a great poet; he was as near perfection as mortal man could be."

In February 1831 Tennyson left Cambridge without taking a degree, and returned to Somersby, his father dying within a month of his arrival. From this time onward Hallam became an intimate visitor at the Rectory, and formed an attachment for his friend's sister Emily. In July 1832 Tennyson and Hallam went touring on the Rhine, and at the close of the year appeared the volume of "Poems by Alfred Tennyson," which contained, amongst others, "The Lady of Shalott," "The Miller's Daughter," "The Palace of Art," "The Lotos Eaters," and "A Dream of Fair Women."

"Well I remember this poem," wrote Fitzgerald, with reference to 'The Lady of Shalott,' "read to me, before I knew the author, at Cambridge one night in 1832 or 3, and its images passing across my head, as across the magic mirror, while half asleep on the mail-coach to London 'in the creeping dawn' that followed."

There she weaves by night and day

A magic web with colours gay.

She has heard a whisper say,

A curse is on her if she stay

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be,

And so she weaveth steadily,

And little other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

The idea of "Mariana in the South" came to Tennyson as he was travelling between Narbonne and Perpignan. Hallam interpreted it to be the "expression of desolate loneliness."

Till all the crimson changed, and past

Into deep orange o'er the sea,

Low on her knees herself she cast,

Before Our Lady murmur'd she;

Complaining, "Mother, give me grace

To help me of my weary load,"

And on the liquid mirror glow'd

The clear perfection of her face.

Of these earlier poems none added more to Tennyson's growing reputation than "The Miller's Daughter." It was probably written at Cambridge, and the poet declared that the mill was no particular mill, or if he had thought of any mill it was that of Trumpington, near Cambridge. But various touches in the poem seem to indicate that the haunts of his boyhood were present in his mind.

Stockworth Mill was situated about two miles along the banks of the Somersby Brook, the poet's favourite walk, and might very well have inspired the setting of these beautiful verses.

I loved the brimming wave that swam

Thro' quiet meadows round the mill,

The sleepy pool above the dam,

The pool beneath it never still,

The meal-sacks on the whiten'd floor,

The dark round of the dripping wheel,

The very air about the door

Made misty with the floating meal.

In the volume of 1832, several stanzas of "The Palace of Art" were omitted, because Tennyson thought the poem was too full. "'The Palace of Art,'" he wrote in 1890, "is the embodiment of my own belief that the Godlike life is with man and for man."

Amongst the "marvellously compressed word pictures" of this poem is the beautiful one of our illustration on page 11.

Or in a clear-wall'd city on the sea.

Near gilded organ-pipes, her hair

Wound with white roses, slept St. Cecily;

An angel look'd at her.

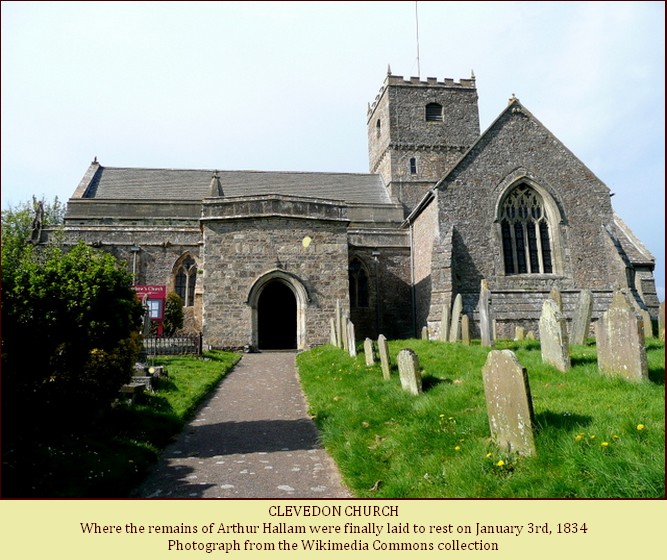

On the 15th of September, 1838, Arthur Hallam died suddenly at Vienna. His remains were brought to England, and laid finally to rest in the old and lonely church beside the sea at Clevedon, on January 3rd, 1834.

When on my bed the moonlight falls,

I know that in thy place of rest

By that broad water of the west

There comes a glory on the walls.

Tennyson's whole thoughts were absorbed in memories of his friend, and he continually wrote fragmentary verses on the one theme which filled his heart, many of them to be embodied seventeen years later in the completed "In Memoriam."

The home of Emily Sellwood, at Horncastle/Grasby Church

In 1830 Tennyson first met Emily Sellwood, who twenty years later became his wife. Horncastle was the nearest town to Somersby, and in the picturesque old market-square stood the red-brick residence of Mr. Henry Sellwood, a solicitor. The young Sellwoods being much of the same age as the Tennysons, a friendship sprang up between the two families, which in later years ripened into a double matrimonial relationship. In 1836, Charles Tennyson, the poet's elder brother, married Louisa, the youngest daughter of Henry Sellwood. In the previous year he had succeeded to the estate and living of Grasby, taking the surname of Turner under his great-uncle's will. At his own expense he built the vicarage, the church and the schools; and on his death, in 1879, Grasby descended to the Poet Laureate. It was at his brother's wedding that the bride's sister, Emily, was taken into church by Alfred Tennyson, but no engagement was recognised between them until four or five years later, and their marriage did not take place until 1850. It was solemnised at Shiplake Church on June 13th, the clergyman who officiated being the poet's intimate friend, the Rev. Robert Rawnsley.

In the April of the same year, on the death of Wordsworth, Tennyson had been offered the poet-laureateship, to which post he was appointed on November 19th, owing chiefly to Prince Albert's admiration for "In Memoriam."

Lady Tennyson became the poet's adviser in literary matters. "I am proud of her intellect," he wrote. She, with her "tender, spiritual nature," was always by his side, cheerful, courageous, and a sympathetic counsellor. She shielded his sensitive spirit from the annoyances and trials of life and "her faith as clear as the heights of the June-blue heaven" helped him in hours of depression and sorrow.

Chapel House, Twickenham, was the poet's first settled home after his marriage, and he resided in it for three years. It was here his "Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington" was written, and the birth of his son Hallam took place in this house on August 11th, 1852.

Farringford, Tennyson's residence at Freshwater

In 1853, whilst staying in the Isle of Wight, Tennyson heard that the residence called Farringford was to let at Freshwater. He decided to take the place on lease, but two years later purchased it out of the proceeds resulting from "Maud," which was published in 1855, and Farringford remained his home during the greater part of each year for forty years, and here he wrote some of his best-known works.

"The house at Farringford," says Mrs. Richmomd Ritchie in her Records, "seemed like a charmed palace, with green walls without, and speaking walls within. There hung Dante with his solemn nose and wreath; Italy gleamed over the doorways; friends' faces lined the passages, books filled the shelves, and a glow of crimson was everywhere; the oriel drawing-room window was full of green and golden leaves, of the sound of birds and of the distant sea."

The grounds of Farringford are exceedingly beautiful and picturesque. On the south side of the house is the glade, and close by

The waving pine which here

The warrior of Caprera set.

Referring to Farringford in his invitation to Maurice, Tennyson wrote—

Where far from noise and smoke of town

I watch the twilight falling brown

All round a careless order'd garden,

Close to the ridge of a noble down.

The ridge of the down in question constituted the poet's favourite walk, and the scenery which he encountered round Freshwater Bay might well have been represented in the opening verse of "Enoch Arden"—

Long lines of cliff breaking have left a chasm;

And in the chasm are foam and yellow sands.

Inland the road leads to the little village of Freshwater, in which the erection of a number of new houses evoked from the poet the lines—

Yonder lies our young sea-village—Art and Grace are

less and less:

Science grows and Beauty dwindles—roofs of slated hideousness!

Opposite these villas stands an ivy-clad house at that time occupied by Mrs. Julia Cameron, the celebrated lady art-photographer, two of whose effective portraits of Tennyson appear on pages 22 and 26.

"The Idylls of the King"/Aldworth

In the autumn of 1859, "The Idylls of the King" were first issued in their original form, being four in number: Enid, Vivien, Elaine, and Guinevere, and from their publication until the end of Tennyson's life his fame and popularity continued without a check. During the next few years the poet spent much time in travelling, but in 1868 he laid the foundation-stone of a new residence, named Aldworth, about two miles from Haslemere, which became his second hone—

You came, and look'd and loved the view

Long-known and loved by me,

Green Sussex fading into blue,

With one grey glimpse of sea.

On the way from Haslemere to Aldworth, it is necessary to cross a rough common covered with whin bushes to reach the long winding lane which was named Tennyson's Lane. This was the poet's favourite walk when living in the neighbourhood.

Tennyson's Memorial, Beacon Hill, Freshwater

Tennyson died on Thursday, October 6th, 1892, and was buried in the Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey, next to Robert Browning, and near the Chaucer monument. Against the pillar close by the grave has been placed Wolner's well-known bust. The monument erected to the memory of the poet on Beacon Hill, near Freshwater, was unveiled by the Dean of Westminster on August 6th, 1897.

Alfred Tennyson (from the painting by Samuel Laurence)

With regard to the portraits of Tennyson reproduced in these pages, perhaps those of chief interest in addition to the Cameron photographs already referred to are the paintings by Samuel Laurence, executed about 1838, and the three-quarter length by G. F. Watts, now in the possession of Lady Henry Somerset. Of the former Fitzgerald wrote:

"Very imperfect as Laurence's portrait is, it is nevertheless the best painted portrait I have seen; and certainly the only one of old days. 'Blubber-lipt' I remember once Alfred called it; so it is; but still the only one of old days, and still the best of all, to my thinking."

Alfred Tennyson (from the painting by G. F. Watts in 1859)

The Watts portrait, according to Mr. Watts-Dunton, possesses "a certain dreaminess which suggests the poetic glamour of moonlight." The same writer asserts that "while most faces gain by the artistic halo which a painter of genius always sheds over his work, there are some few, some very few faces that do not, and of these Lord Tennyson's is the most notable that I have ever seen among men of great renown."

Cover of First Edition

THE following pictures were painted by Helen Allingham (1884-1926). They were reproduced in the book The Homes of Tennyson, published in 1905 by Adam and Charles Black, London. A copy of the book, which was authored by Arthur Patterson, F.R. Hist. S., is available at the Internet Archive (archive.org).

Aldworth

Tennyson loved the autumn on Blackdown, so I was the more pleased to make this drawing of his stately Sussex home when the Virginia creeper was in its full autumn glory.

The house was not so richly covered with creepers when I was first invited to stay there in the autumn of 1876, but the great view of the Weald of Sussex remains the same as ever it was "Green Sussex fading into blue."

Tennyson's Down

I made this drawing of the "High Down" ("The Noble Down") in May, from the edge of the copse on Maiden's Croft. On its highest part stands the monument placed by English and Americans on the site of the old Beacon, and from there the Down slopes away for a mile and a half to the Needles. To the Beacon and back was a favourite walk of the Poet's. The copse was full of bluebells, and some of them had escaped into the field.

The Primrose Path of Dalliance, Farringford

This is the family name for the lovely path through the copse on the Maiden's Croft. It is approached from the House by the little bridge that spans the lane through Farringford. Tennyson loved the flowers and could not bear to see any plucked, even when growing in profusion in the fields. This drawing belongs to old friends of his who have always known the path well.

The Glade, Farringford

The Glade is the name given to a narrow wood- land path leading down from the little postern in the lane to the Upper Lawn, a green open scoop in the woods, whence one catches the first glimpse of the House. Here the tall trees have blown over, and have been allowed to stay just where they caught in each other's branches. Heart's-tongue and filix-mas ferns and bluebells line the path on either side. The utter quietude of the place, only broken now and again by the squeak of a squirrel, brought to my mind as I painted there Keats's beautiful opening lines in Hyperion

"No stir of air was there,

Not so much life as on a summer's day

Robs not one light seed from the feather' d grass,

But where the dead leaf fell, there did it rest."

Glimpse of Farringford

from the Upper Lawn

I made this drawing in the spring of 1890, and as the Poet liked it, I asked him to keep it. The grass on the path, then getting thin from the close, high growth of the trees, has now quite gone. The face of the House, with the great magnolia and roses twining round the windows of Tennyson's own special rooms, remains almost the same.

Farringford

In 1890 I made a drawing of Farringford from almost the same point of view, as I think it is the best of this, the living, side of the house. In my first drawing I had the opportunity of sketching the Poet as he walked out in his boat cloak, but this time there were no inhabitants of the place but the gardeners one, an old friend of mine, William, the coachman of forty years' standing, came to talk with me sometimes and in their absence some intruding rabbits enjoyed themselves on the lawn.

Freshwater Bay

My drawing of the Bay from the Park (near to the lane that runs through it) was painted this May after sunset when the buttercups and daisies had closed their petals. Afton Down rises to the left with its military road this end of the road is new, as some years ago the old end fell into the sea. The Stag rock just shows among the trees, and beyond are the red headlands on either side of Brook Bay, where lies the submerged "primeval forest." In the distance is St. Catherine's Point, the most southern in the Island. This view was seen, with a little difference in the immediate foreground, in the early sixties from Farringford House. But gradually the trees have grown up in the middle distance so that only a glimpse of the bay is now left. To recover the old view, Lord Tennyson tells me, he would have to cut away a whole wood. Even from the platform on the roof of the house one cannot now get the clear sweep of the down as seen in a drawing at Farring- ford made by "Dicky Doyle" of the old view from the drawing-room window.

Arbour in Farringford Kitchen Garden

Tennyson made this arbour for his wife in the early days of their coming to Farringford. The white lilac (of which there are bushes on either side) was one of his favourite flowers. The old arbour still stands, but is so closely overgrown with ivy that it cannot be much used for sitting in. I remember (when I was painting it, I think) the Poet taking Mr. Birket Foster and myself there to rest one sunny morning: he was in cheerful mood, and was amused by telling, and listening to, funny stories and sayings.

In the Kitchen Garden, Farringford

The arbour that is shown in the corner of this drawing is newer and less picturesque than the one Tennyson made. Of late years he sat in it much on sunny afternoons in early spring, screened from the cold winds ; and many were the friendly meetings, talks, and teas that privileged friends have enjoyed with the Poet in this little house. The old cherry tree happened to be in fine bloom the spring I made this drawing, and on the right of it can be seen a little fir tree that was rooted on the top of the old wall. Later (when the present Lord Tennyson was in Australia) that part of the wall fell down in a great storm, probably partly because of the weight of this strong little tree on its summit.

The Kitchen Garden, Farringford

Leaving the dairy behind, one passes up a long walk bordered on both sides with flowers, the fruit trees and vegetables behind them. The time of this drawing is the middle of May the elms are in their brightest green, the roses and lilies in bud the apple blossom is beginning to go over, but the lilacs, hyacinths, pink peony, pansies, and sweet- scented stocks are in perfection, with tulips and wall-flowers still bright, and the edging of aubretia still lilac.

The Dairy Door, Farringford

This leads from the dairy farm up into Farringford Kitchen Garden, and is, I think, so pretty a door- way, besides being so interesting, that I have twice painted it. The Poet frequently brought his friends down through the Kitchen Garden from Farringford. When I was painting there he always stopped to see how my drawings were getting on.

Farringford Dairy and Home Farm

The farm is a long old stone cottage, with a deep thatch, and old barns and byres around it, lying at the foot of the kitchen garden, and facing the lane (at its turn here) running through the wilderness property. This drawing was made from the field (in a corner of which stand the ricks) and looks across the lane, down which the children are passing. This last year or two Mrs. Diment's growing family of fowls (not to speak of guinea-fowls and peacocks) have pecked away most of the grass and hedge near the gate.

Aldworth from Blackdown

Although Aldworth commands such a magnificent view, there are few places from which the house can be seen from without. I made this sketch in the eighties, when we were living at Witley, and last autumn, strolling over the down, I found the same point of view. The scene seemed almost exactly as it was about twenty years ago.

From the Porch, Aldworth

We were staying in Haslemere during the summer of 1880, and my husband and I often walked up to Aldworth. Tennyson pointed out this as one of his favourite views a little glimpse of a farmhouse with the blue distance beyond, framed in by the pots of geraniums and formal trees on his terrace, and then by the arch of his porch. So I proposed to sketch it for him, and there was a sort of compact that, in return, he would allow me to make a drawing of himself, an operation by no means pleasant to him.

Chase Cottage and Pond

Lord Tennyson, who showed me this secluded spot some years ago, told me that it was one of his father's favourite walks from Aldworth. It lies in a hollow of Blackdown. The Poet always loved water (running water when possible), and liked to come and look into the depths of this shady pond, and to watch the little gold birch and beech leaves floating on its surface as they floated last autumn when I made this drawing.

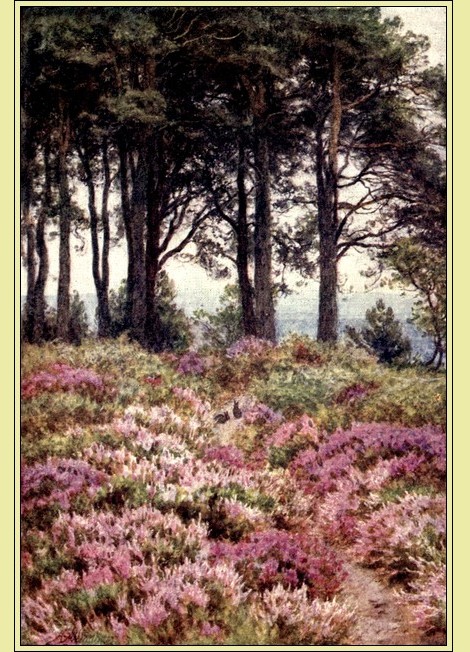

The Temple of the Winds, Blackdown

A group of fir trees stands on the far south-eastern corner of Blackdown, exposed to all the winds of heaven. There is a wide view over the Weald of Sussex from this point, and southward, on very clear days, one may get a glimpse of the sea between the hills. Just below the trees are the ruins of an old summer-house where Tennyson, in days gone by, used to sit. I did this drawing some years ago.. The young trees and shrubs have since grown up and choked the heather that used to border the little path going to the firs.

Cottage at Roundhurst

One day when my husband and I were over from Witley, Tennyson took us for a beautiful walk, within sight of this old cottage, but it was too muddy that day for us to get near it. Later, in '90, "91, and '92, I often walked over the Down from Haslemere to paint, and made this and several other drawings of the cottage. One day Tennyson walked with us from Aldworth, and rested on a cottage chair in the little garden (at the far side of the cottage in this drawing) by a little rillet of spring water rushing down from the hillside.

Shed at Roundhurst

This old shed, now gone, lay at the foot of Black - down, near the old Roundhurst farm built by Inigo Jones or by one of his disciples. I went over from Witley several times to paint it. A long climb back up the winding drive, we always found it, to the friendly greeting and tea that awaited us at Aldworth.

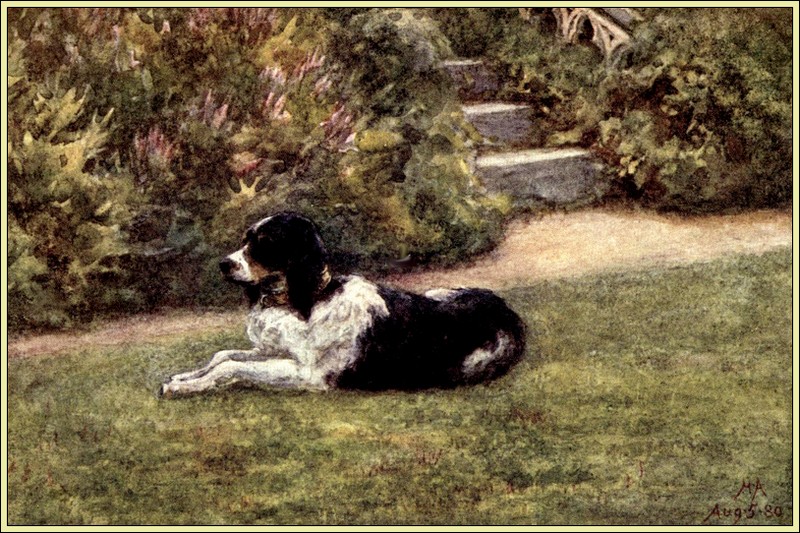

Old Don

It was when we were spending the summer of 1880 at Haslemere that I made the sketch of the favourite old setter. The day after my last visit to paint him, the old dog died, and Tennyson wrote his name under the little drawing.

Tennyson's Woods at Blackdown

I made this drawing in 1902, I think, looking southwards from Tennyson's road to his woods over Fox's Holes. The old road goes all the way through his property, skirting the garden in a deep cutting called Packhorse Lane.

This site is full of FREE ebooks - Project Gutenberg Australia