a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Voyage In Search Of La Perouse Volume I Author: Jacques Labillardiere * A Project Gutenberg Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1203851h.html Language: English Date first posted: October 2012 Date most recently updated: October 2012 Produced by: Ned Overton and Col Choat Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

The life of La Pérouse and the fate of this voyage of discovery,

which was never determined by Dentrecasteaux and his party,

are discussed in detail in

Ernest Scott's "[Life of] Lapérouse",

at Project Gutenberg Australia.

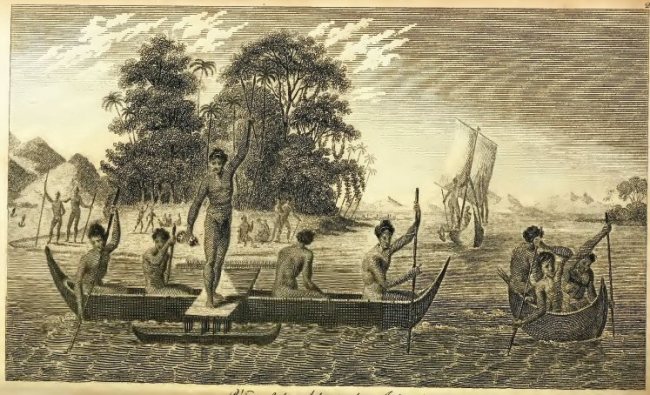

PLATE XXVII. Dance of the Women of the Friendly Islands

in

Presence of Queen Tiné

London:

PRINTED FOR JOHN STOCKDALE, PICCADILLY.

1800.

T. Gillet, Printer, Salisbury Square.

TO

ROBERT PEEL, ESQ.

Member of Parliament for the Borough of

Tamworth, &c. &c. &c.

Who, by his Ingenuity, Abilities, and Industry, has

honourably

acquired a princely Fortune, and in so doing had the

Satisfaction of keeping several thousand

Persons in constant Employment:

Who, in the Time of Danger and National Difficulty,

handsomely appropriated the munificent Sum of

TEN THOUSAND POUNDS,

TO THE EXIGENCIES OF HIS COUNTRY:

And whose Conduct,

In promoting AN UNION WITH IRELAND,

has shone so nobly disinterested:

THIS WORK,

AS A SMALL MARK OF RESPECT AND

ESTEEM,

IS HUMBLY DEDICATED,

By his ever obliged, obedient,

And faithful Friend and

Servant,

John Stockdale.

London 6th May, 1800.

THE laudable taste for Voyages and Travels, which prevails in the present age, has been gratified with many excellent productions, which render that species of literature highly interesting to readers of almost every description. Modern voyages of discovery have embraced so Many objects, that in them the Navigator sees the progress of his important art, the Geographer observes the improvement of his kindred science, the Naturalist is gratified with curious and useful objects of research, the Merchant discovers new scenes of commercial enterprise, and the General Reader finds, a fund of rational entertainment.

The Moral Philosopher, too; who loves to trace the advances of

his species through its various gradations from savage to

civilized life, draws from voyages and travels, the facts from

which he is to deduce his conclusions respecting the social,

intellectual, and moral progress of Man. He sees savage life

every where diversified with a variety, which, if he reason

fairly, must lead him to conclude, that what is called the state

of nature, is, in truth, the state of a rational being placed in

various physical circumstances, which have contracted or expanded

his faculties in various degrees; but that "men always

appear

"among animals a distinct and a superior race;

"that neither the possession of similar organs,

"nor the use of the hand, which nature has

"given to some species of apes, nor the continued

"intercourse with this sovereign artist, have

"enabled any other species to blend their nature

"with his; that in his rudest state he is found

"to be above them, and in his greatest degeneracy

"never descends to their level; that he is,

"in short, a man in every condition; and that

"we can learn nothing of his nature from the

"analogy of other animals."* Every where adapting means to

ends, and variously altering and combining those means, according

to his views and wants, Man, even when pursuing the gratification

of animal instincts, too often miserably depraved, shows himself

to be possessed of nobler faculties, of liberty to chuse among

different objects and expedients, and of reason to direct him in

that choice. There is sufficient variety in human actions to show

that, though Man acts from motives, he acts not mechanically, but

freely; yet sufficient similarity of conduct, in similar

circumstances, to prove the unity of his nature. Hence there

appears no ground whatever for supposing, that any one tribe of

mankind is naturally of an order superior to the rest, or has any

shadow of right to infringe, far less to abrogate, the common

claims of humanity. Philosophers should not forget, and the most

respectable modern philosophers have not forgotten, that the

savage state of the most civilized nations now in Europe, is a

subject within the pale of authentic history, and that the

privation of iron alone, would soon reduce them nearly to the

barbarous state, from which, by a train of favourable events,

their forefathers emerged same centuries ago. If the limits of a

preface would allow us to pursue the reflections suggested by the

different views of savage life, presented by this and various

other scientific voyages, it would be easy to show, that the

boasted refinement of Europe entirely depends on a few happy

discoveries, which are become so familiar to us, that we are apt

to suppose the inhabitants of these parts of the world to have

been always possessed of them; discoveries so unaccountable, and

so remote from any experiments which uncivilized tribes can be

supposed to have made, that we cannot do better than acknowledge

them among the many precious gifts of an indulgent

Providence.

[* Ferguson on Civil Society.]

Having mentioned Providence, a word not very common in some of our modern voyages, we are tempted to add a consideration which has often occurred to our minds, in contemplating the probable issue of that zeal for discovering and corresponding with distant regions, which has long animated the maritime powers of Europe. Without obtruding our own sentiments on the reader, we may be permitted to ask, whether appearances do not justify a conjecture, that the Great Arbiter of the destinies of nations may render that zeal subservient to the moral and intellectual, not to say the religious, improvement, and the consequent happiness, of our whole species? or, Whether, as has hitherto generally happened, the advantages of civilization may not, in the progress of events, be transferred from the Europeans, who have but too little prized them, to those remote countries which they have been so diligently exploring? If so, the period may arrive, when New Zealand may produce her Lockes, her Newtons, and her Montesquieus; and and when great nations in the immense region of New Holland, may send their navigators, philosophers, and antiquaries, to contemplate the ruins of ancient London and Paris, and to trace the languid remains of the arts and sciences in this quarter of the globe. Who can tell, whether the rudiments of some great suture empire may not already exist at Botany Bay?

But, not to detain the reader with such general reflections, which, however, open interesting views to contemplative minds, we proceed to say a few words of the work now presented to the Public. And here we need to do little more than refer to the learned and ingenious Author's introduction to his own work. The reader will immediately perceive that, if it has been tolerably executed, it must form a valuable Supplement to the Voyage* of the unfortunate La Pérouse so valuable indeed, that it may fairly be questioned, whether that work can be considered as perfect without it.

[* Printed for Stockdale, London, in two large vols. 8vo. with fifty-one fine Plates. It must be observed, that this is the only edition to which are annexed the interesting Travels of De Lesseps, over the Continent, from Kamtschatka, with Pérouse's dispatches.]

Of the execution of the work, the reader must form his own judgment. He will perhaps agree with us, that the Author writes with the modesty and perspicuity which become a philosopher, who all along recollects that he is composing a narrative, and not a declamation. He has, in our opinion, with, great taste and judgment, generally abstained from those rhetorical flourishes, which give an air of bombast to too many of the works of his countrymen, even when treating of subjects which demand accuracy rather than ornament. Most of his reflections are pertinent and just, and not so far pursued as to deprive the reader of an opportunity of exercising his ingenuity by extending them farther.

This chaste and unaffected manner of writing may be considered as an internal mark of the fidelity of his narrative. He had no weak or deformed parts to conceal with flowery verbiage, and therefore he rejected its meretricious aid. As another, and a fill stronger proof of our Author's fidelity, we may mention his occasional censure of the conduct of Officers, not excepting the Commander in Chief himself, when their conduct happened not to appear quite deserving of that general approbation, which he seems willing to bestow. A man must be very conscious of having honestly executed his own mission, and of faithfully describing the objects of it, when he scruple not to express publicly his disapprobation of the conduct of Officers of talents and distinction, engaged in the higher departments of the same great undertaking.

In translating the work, the object aimed at was to render it so literally as never to depart from the meaning of the Author; yet so freely as not merely to clothe his French idiom with English words. The translation of such a work should, in our opinion, be free without licence, and literal without servility.

Some readers would, no doubt, have willingly dispensed with a great number of the nautical remarks, and with all the bearings and distances; but those particulars were plainly so important to navigators, that they could not, on any account, be omitted. Nor, indeed, has a single sentence of the original, been retrenched in the translation, except two passages, which would have been justly considered as indelicate by most English readers; and, for the same reason, the two engravings referred to in the exceptionable passages, have been altered.

The whole of the plates are given in a style generally not inferior to the original, which, with the French work in quarto, are sold for six guineas, being thrice the price of the present translation.

*** In the original, the distances are all expressed in the new French denominations of metres, decametres, &c. and the Author has given a table for reducing them to toises. But, in the translation, the reader has been spared that trouble, by every where inserting the equivalent toises, French fathoms. A toise is equal to six French feet, or nearly to six feet five inches, English measure; 2,853 toises make a geographical or nautical league, twenty of which make a degree of a great circle of the earth. Hence, to reduce toises to nautical leagues, divide them by 2,853; the quotient will be the leagues, and the remainder the odd toises.

NO intelligence had been received for three years respecting the ships Boussole and Astrolabe, commanded by M. de la Pérouse, when, early in the year 1791, the Parisian Society of Natural History called the attention of the Constituent Assembly to the fate of that navigator, and his unfortunate companions.

The hope of recovering at least some wreck of an expedition undertaken to promote the sciences, induced the Assembly to send two other ships to fleet the same course which those navigators must have pursued, after their departure from Botany Bay. Some of them, it was thought, might have escaped from the wreck, and might be confined in a desert island, or thrown upon same coast inhabited by savages. Perhaps they might be dragging out life in a distant clime, with their longing eyes continually fixed upon the sea, anxiously looking for that relief which they had a right to expect from their country.

On the 9th of February 1791, the following decree was passed upon this subject:

"The National Assembly having heard the

"report of its joint Committees of Agriculture,

"Commerce, and the Marine, decrees,

"That the King be petitioned to issue orders

"to all the ambassadors, residents, consuls, and

"agents of the nation, to apply, in the name of

"humanity, and of the arts and sciences, to the

"different Sovereigns at whose courts they

"reside, requesting them to charge all their

"navigators and agents whatsoever, and in what

"places soever, but particularly in the most south

"erly parts of the South Sea, to search diligently

"for the two French frigates, the Boussole and

"the Astrolabe, commanded by M. de la

"Pérouse, as also for their ships' companies, and to

"make every inquiry which has a tendency to

"ascertain their existence or their shipwreck; in

"order that, if M. de la Pérouse and his

"companions should be found or met with, in any place

"whatsoever, they may give them every assistance,

"and procure them all the means necessary

"for their return into their own country, and for

"bringing with them all the property of which

"they may be possessed; and the National

"Assembly engages to indemnify, and even to

"recompense, in proportion to the importance of

"the service, any person or persons who shall

"give assistance to those navigators, shall procure

"intelligence concerning them, or shall be

"instrumental in restoring to France any papers or

"effects whatsoever, which may belong, or may

"have belonged, to their expedition:

"Decrees, farther, that the King be petitioned

"to give orders for the sitting out of one or more

"ships, having on board men of science,

"naturalists, and draughtsmen, and to charge the

"commanders of the expedition with the

"two-fold mission of searching for M. de la Pérouse,

"agreeable to the documents, instructions, and

"orders which final be delivered to them, and of

"making inquiries relative to the sciences and to

"commerce, taking every measure to render this

"expedition useful and advantageous to navigation,

"geography, commerce, and the arts and

"sciences, independently of their search for M.

"de la Pérouse, and even after having found him,

"or obtained intelligence concerning him."

Compared with the original, by us the President and Secretaries of the National Assembly, at Paris, this 24th day of Feb. 1791.

| (Signed) | DUPORT, | President. |

| {LIORE, {BOUSSION, |

Secretaries. |

From my earliest years, I had devoted myself to the science of natural history; and, being persuaded, that it is in the great book of Nature, that we ought to study her productions, and form a just idea of her phenomena, when I had finished my medical course, I took a journey into England, which was immediately followed by another into the Alps, where the different temperatures of a mountainous region present us with a prodigious variety of objects.

I next visited a part of Asia Minor, where I resided two years, in order that I might examine those plants, of which the Greek and Arabian physicians have left us very imperfect descriptions; and I had the satisfaction of bringing from that country very important collections.

Soon after my return from this last tour, the National Assembly decreed the equipment of two ships, in order to attempt to recover at least a part of the wreck of the ships commanded by La Pérouse.

It was an honourable distinction to be of the number of those, whose duty it was to make every possible search, which could contribute to restore to their country, men who had rendered her such services.

That voyage was, in other respects, very tempting to a naturalist. Countries newly discovered might be expected to increase our knowledge with new productions, which might contribute to the advancement of the arts and sciences.

My passion for voyages had hitherto increased, and three months spent in navigating the Mediterranean, when I went to Asia Minor, had given me some experience of a long voyage. Hence I seized with avidity this opportunity of traversing the South Seas.

If the gratification of this passion for study costs us trouble, the varied products of a newly discovered region amply compensate us for all the sufferings unavoidable in long voyages.

I was appointed by the Government to make, in the capacity of naturalist, the voyage of which I am about to give an account.

My Journal, which was kept with care during the whole course of the voyage, contained many nautical observations; but I ought to observe, that that part of my work would have been very incomplete, without the auxiliary labour bestowed upon it by Citizen Legrand, one of the best officers of our expedition.

I take this opportunity of testifying my grateful remembrance of that skilful mariner, whose loss in the present war is a subject of regret.

When I was leaving Batavia, in order to proceed to the Isle of France, Citizen Piron, draughtsman to the expedition, begged my acceptance of duplicates of his drawings of the dresses of the natives, which he had made in the course of the Voyage. I do not hesitate to assure my readers, that those works of his pencil are striking likenesses.

I have endeavoured to report, in the most exact manner, the facts which I witnessed during this painful voyage, across seas abounding with rocks, and among savages, against whom it was necessary to exert continual vigilance.

General Dentrecasteaux received the command of the expedition. That officer requested from the Government two ships of about five hundred tons burden, Their bottoms were sheathed with wood, and then filled with scupper nails. It was not apprehended that this mode would diminish their velocity, and it was thought that it would add to the solidity of their construction. It is, however, acknowledged that ships sheathed and bottomed with copper may be constructed with equal solidity, and that they have greatly the advantage in point of sailing. Those ships received names analogous to the object of the enterprize. That in which General Dentrecasteaux embarked, was called the Recherche (Research), and the other, commanded by Captain Huon Kermadec, received the name of the Esperance (the Hope).

The Recherche had on board one hundred and thirteen men at the time of her departure: the Esperance only one hundred and six.

ON BOARD OF THE RECHERCHE.*

Principal Officers.

| Bruny Dentrecasteaux, Commander of the Expedition, | |

| Doribeau [Dauribeau], Lieutenant, | |

| Rossel, ditto, | |

| Cretin, ditto, | |

| Saint Aignan, ditto, | |

| Singler Dewelle ditto, | |

| Willaumez senior, Ensign, | |

| Longuerue, Eleve, | |

| Achard Bonvouloir, ditto, | |

| Dumerite, Volunteer, | |

| Renard, Surgeon, | |

| Hiacinthe Boideliot, Surgeon's Mate. | |

| Letrand, Astronomer, | |

| Labillardiere, Naturalist, | |

| Deschamps, ditto, | |

| Louis Ventenat, ditto, acting as Chaplain, | |

| Beautems Beaupré, Geographical Engineer, | |

| Piron, Draughtsman, | |

| Lahaie, Gardener. | |

| Warrant and Petty Officers | 8 |

| Gunners and Soldiers | 18 |

| Carpenters | 3 |

| Caulkers | 2 |

| Sail-makers | 2 |

| Pilots | 3 |

| Armourer | 1 |

| Blacksmith | 1 |

| Sailors | 36 |

| Young Sailors | 3 |

| Boys | 4 |

| Cook, Baker, &c. | 5 |

| Domestics. | 8 |

ON BOARD THE ESPERANCE.

Principal Officers.

| Huon Kermadec, Captain, | |

| F Trobiant, Lieutenant, | |

| Lasseny, ditto, | |

| Lufançay, ditto, | |

| Larnotte Dupertail, ditto, | |

| Legrand, Ensign, | |

| Laignel, ditto, | |

| Jurieu, Volunteer, | |

| Boyne, Eleve, | |

| Jouanet, Surgeon, | |

| Gauffre, Surgeon's Mate. | |

| Pierson, Astronomer, acting as Chaplain, | |

| Riche, Naturalist, | |

| Blavier, ditto, | |

| Jouveney, Geographical Engineer, | |

| Ely, Draughtsman, | |

| Warrant and Petty Officers | 8 |

| Armourers | 2 |

| Gunners and Marines | 14 |

| Carpenters | 3 |

| Blacksmith | 1 |

| Caulkers | 2 |

| Sail-makers | 2 |

| Pilots | 4 |

| Sailors | 36 |

| Boys | 5 |

| Cook, Baker, &c. | 5 |

| Domestics | 8 |

[* The name of every individual on board both the ships is inserted in the original; but it seems unnecessary to retain any names in this translation but that of the officers and men of science, who, if we may tire the expression, are the chief dramatis personæ, and several of them come forward, in their respective capacities, in the course of the work.—Translator.]

It is melancholy to add, that of two hundred and nineteen people, ninety-nine had died before my arrival in the Isle of France. But it must be observed, that we lost but few people in the course of our voyage, and that the dreadful mortality which we experienced was owing to our long stay in the island of Java.

|

CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. LIST OF PLATES.

|

[A list of plates for Volume II. has been moved to that volume.]

PLATE I. CHART of the World, exhibiting the Track of M. de

la Pérouse, and the Tracks of La Recherche and L'Esperance

in Search of that Navigator

Departure from Brest—Arrival at St.

Croix, in the Island of Teneriffe—Journey to the Peak of

Teneriffe—Resuscitation of a Sailor who had been

drowned—Some daring Robbers early off his Clothes—Two

of our Naturalists are attacked with a spilling of Blood, which

obliges them to give up their Design of Proceeding to the Summit

of the Peak—English Vessels in the Road of St.

Croix—Different Results from the Observations made in Order

to determine the Variations of the Needle—New Eruption of a

Volcano to the South-east of the Peak.

AUGUST, 1791.

THE equipment of the two vessels appointed for the voyage which we were about to undertake being already in a state of great forwardness, towards the close of the month of August, we received orders from General Dentrecasteaux to repair to Brest. I had the pleasure of travelling thither in the company of three persons engaged in the same expedition, namely, the Citizens Riche, Beaupré, and Pierson.

We arrived at Brest on the 10th of September. Some of the finest ships in the French navy, such as the Majestueux, the Etats de Bourgogne, the America, &c. were then in the harbour.

While our astronomers were engaged in making the observations necessary for determining the movements of our time-keepers, those who designed to make Natural History the principal object of their attention were employed in furnishing themselves with all the requisites for preparing the collections, which they purposed to make in the unknown countries we were about to visit.

As it was my intention to devote myself chiefly to the observation of the vegetable kingdom, I stood in need of a great quantity of paper, and wished to provide myself with some of a very large size. It was, however, not without great difficulty that I was able to procure twenty-two reams; almost all that remained in the warehouses having been lately appropriated to the service of the artillery.

I employed a part of the time that I had at my own disposal in examining the botanical garden, which is kept in very good order. There is also, in this place, a small cabinet of natural history, which contains several anatomical preparations presented to it by Citizen Joannet, surgeon of the Esperance.

The muster of our crews took place in the harbour on the 21st of September.

The vessels went into the road-stead on the 25th. There were then no foreign ships there, and very few French.

We were very heavily laden, so that when we let sail our draught was thirteen feet nine inches at the stern, and twelve feet ten inches at the head.

There were on board the Recherche; 6 eight pounders; 2 carronades of thirty-six; 6 pedereroes of half a pound; 12 pedereroes of six ounces; 45 muskets; 35 pistols; 50 sabres; 30 battle-axes, and 10 espingoles.

The Esperance was provided with nearly the same means of defence, which were sufficient to secure us against any violence that might be attempted by savages.

Both vessels were furnished with a great bore of commodities intended to be distributed amongst the natives of the South-seas. Iron tools, and stuffs of different colours, especially red, formed the basis of our bartering stock.

Each of the vessels was bored with provisions sufficient for the consumption of eighteen months. We now only waited for a favourable wind to set sail. A pretty fresh breeze springing up from the east, enabled us to get under way about one o'clock in the afternoon of the 28th of September. Soon after we had left the roads, we discovered two sailors and a cabin-boy, who being very desirous of going on this expedition, and having been disappointed in their with to be included in our crew, had concealed themselves in the ship. As we had scarcely room sufficient for the men already on board, our Commander gave orders to tack about and make for the roads of Bertheaume, where our three unbidden guests were set on shore.

The Esperance, having met with no such interruption, had got considerably a-head of us, but we came up with her before night, as our vessel was a much better sailer.

At taking our departure at six in the evening, we found our place to be 48° 13' N. lat. 7° 15' E. long.

We set the ouessant at N. 2° W. of the compass.

The bec de la chevre at S.E. 4° E.

The bec du raz at S. 2° E.

Point Mathieu was then at the distance of 2,565 toises.

We now steered our course E.N.E. till towards midnight, when we directed it right east.

On the 29th, our Commander Dentrecasteaux was informed, by dispatches which he had orders not to open before we were in the main sea, that Major Huon Kermadec, Commander of the Esperance, was advanced to the rank of post-captain (capitaine de vaisseau), and himself to that of rear-admiral (contre-amiral). This intelligence was immediately conveyed by the speaking-trumpet to the Esperance, and our flags were hoisted with the distinctive ensigns of the rank conferred upon the Commander.

We again discovered two marines, and a cabin-boy, who were not inrolled among our crew, and had kept themselves till now concealed in the ship. As we were already too far from the land to set them on shore, the Commander permitted them to accompany us on our expedition.

Having made several sea-voyages before the present, I had flattered myself that I was too seasoned a sailor to be any more incommoded by the motion of the vessel; but I found that I had already entirely lost this qualification, for I was sea-sick during the first three days after our sailing from Brest. I have had frequent opportunities in the course of this voyage of remarking, that a very short stay upon shore is sufficient to render me anew susceptible of sickness from the motion of the vessel; for whenever we have put out to sea, after having lain a short time at anchor, I have always been disordered for two or three days as much as I was after our departure from Brest. The sailors advise one, in these cases, to endeavour to eat, notwithstanding the loathing of food that always accompanies this disorder. But this piece of advice it is very difficult to follow for besides the pain produced by the action of swallowing, the presence of food in the stomach increases the nausea, and the vomiting that supervenes is still more distressing.

Diluting liquors, taken in small quantities at a time, so as not to burden the stomach, have always afforded me the most relief. Lukewarm water, slightly sweetened with sugar, is the drink which I have generally used, as it is the easiest to be procured at sea.

We had, however, several persons on board, who, though they had never been at sea before, experienced not the smallest inconvenience from the toiling of the ship. Such a constitution is very desirable for those who undertake long voyages; for it is impossible to describe the disagreeable sensations that attend this spasmodic affection, which, as it operates upon every part of the frame, produces such a general depression of its powers, that life would be insupportable, were it not for the hope of a speedy termination of the disorder.

From the day of our setting sail, to the 5th of October, we had slight breezes, that varied between the north and east points of the compass. From that time to our arrival at Teneriffe, they blew pretty fresh, varying between the north and north-east. This alteration in the state of the wind gave us no small uneasiness, as in our situation it might become productive of the most fatal consequences. Lumbered as we were in every part of the vessel, and drawing considerably above the load-water line, we ran the risk of being overset by a sudden squall; besides, the stowage had been very negligently performed. In this disorderly state we had sailed from France, although the expedition had been decreed by the National Assembly almost eight months before it took place.

On the 11th of October, about fifty-five minutes after ten o'clock, we observed an eclipse of the moon. The observations that can be taken at lea, lead to no very accurate results. Citizen Willaumez, however, concluded, from one which he took, that we were now in the longitude of 18° 19' 45" W. On the 12th, about eight in the morning, the Esperance intimated to us by a signal, that land was espied.

Towards noon we reckoned ourselves to be at the distance of about 71,800 toises from the peak of Teneriffe, which bore S.E.S. raising its head majestically above the clouds.

At the close of the evening we were not more than about 10,260 toises distant from the northeast point of the island. We shifted with the fore and main top-sails every three hours, whilst we expected the dawn. As soon as it appeared, we made towards the island, coasting along at the distance of 500 toises.

About half an hour after nine in the morning, we cast anchor in the road of St. Croix, in a muddy bottom of black sand, about fifteen toises in depth.

The French Consul, Citizen Fontpertuis, waited immediately upon our Commander, with art offer of his services in furnishing us with whatever we might want for the prosecution of our expedition.

I went on shore in the afternoon, to take a view of the environs of the town. Although the season was considerably advanced, the reflection of the rays of the sun from the volcanic stones, produced a degree of heat that was the more oppressive as the air was perfectly calm.

I observed among the plants that grow in the neighbourhood of St. Croix, a woody species of balm, known by botanists under the name of melissa fruticosa, also the saccharum teneriffæ, the cacalia kleinia, the datura metel, the chrysanthemum frutescens, &c. Some of the gardens were ornamented with the beautiful tree termed poinciana pulcherrima.

In the evening, Citizen Ely, being struck with the grotesque appearance of some of the women in the town, who, even during the greatest heat of the season, wear long cloaks of very coarse woollen stuffs, was employed in drawing a sketch of one of them, when he was suddenly interrupted by a sentinel, who imagined him to be taking a plan of the harbour. It was in vain that he attempted to explain to him what his draught was intended to represent; the soldier would not suffer him to finish it.

As we had anchored too close to another small vessel, we cast an anchor in the afternoon nearer to the shore, by which we kept ourselves at a convenient distance.

The bearings we took at this place gave us the following results;

The redoubt on the north side of the town, N.N.E. 4° E.

The great tower situated about the middle of the town, E.S.E.

At sun-rise each of the forts returned our salute of nine guns with an equal number. On the noon of the preceding day, we had saluted the town with fifteen, as it returned us gun for gun.

A packet-boat from Spain cast anchor to-day in the road-stead.

We had agreed to take a journey to the peak on the morrow, and subsequently to visit the other high mountains of the island in succession. The French Consul very obligingly did all that was in his power, to facilitate the execution of our design, and gave us letters of recommendation to M. de Cologant, a very respectable merchant, resident at Orotava.

About four o'clock the next morning, our party assembled upon the Mole to the number of eight; namely, Develle, one of the officers of our ship, Piron, Deschamps, Lahaye, and myself, with three servants, one of whom understood the Spanish language, and served as our interpreter. We found the mules that were to carry us at the sea-side; but it was more than an hour before we could set out upon our journey, it being no easy matter to assemble our guides, some of whom, knowing that we could not set off without them, made no scruple of letting us wait till they chose to make their appearance. When they had arrived we thought we should be able immediately to proceed, but we were obliged to expostulate with them a long time, before they could be induced to carry the small stock of necessaries that we took with us upon our expedition.

The reader will recollect that our ships were so plentifully stored with provisions, that one might have thought we were going to sail to some desert country. Rossel, who had the charge of the officers' table, had given orders to the cook to send us an excellent salmon-pie for our journey should not have mentioned in trivial a circumstance, had it not been for the sake of the contrast which it affords with the worm-eaten biscuits and cheese, that were our usual regale whilst we remained on shore, in the subsequent part of our expedition.

Mons. de Cologant having been informed by the French Consul of our intended journey, invited us to come to his house at the harbour of Orotava. This port, which is not more than about 15,390 toises distant from St. Croix, is a very convenient baiting-place for those who visit the peak; it being situated at the foot of the nearest mountains of the chain to which it belongs.

We were three hour before we arrived at Laguna. This town is only 5,130 toises distant from St. Croix; but the road thither is very fatiguing, as it ascends for the greater part of the way. The place is meanly built, and very thinly inhabited. We were informed that at least one half of its inhabitants consists of monks.

On our way to Laguna we passed over some barren mountains, which were covered with a variety of plants of a luxurious growth. Amongst others we noticed the euphorbia canariensis, the euphorbia dendroides, the cacalia kleinia, the cachis opuntia, &c. These plants, as they derive their nourishment almost entirely from the atmosphere, thrive very well in spite of the sterility of the abrupt precipices on which they grow. When we descended into the small plain on which the town stands, we remarked that the mould produced from the corruption of the vegetables, and washed down from the surrounding mountains by the rain, answers a very useful purpose in fertilizing this little spot of ground, so that it yields abundance of corn, Indian wheat, millet, and other esculent plants.

I here observed a species of the periploca, which I had formerly discovered during my travels in the Levant. I have given an account of it in the second decade of my description of the plants of Syria, under the appellation of periploca angustfolia. Citizen Desfontaines has likewise collected some of the same species upon the coasts of Barbary.

All the stones that we had hitherto seen these regions appeared to have undergone the action of fire. As the mountains of this chain that are of the mean elevation consist of large masses, that after being fused must have retained a great degree of heat for a considerable length of time; expected to find the lavas very compact in their texture. My conjecture was confirmed. Their grain is very fine, and their colour for the most part a deep brown.

Surrounded with these volcanic remains, we found the heat very oppressive, which appeared to incommode our guides much more than ourselves; so that they exerted all their powers of persuasion in order to prevail upon us to make halt during the day, and only travel in the night-time. They probably imagined that our sole aim was to see the summit of the peak, and several of our company would have had no very great objections against our journey being conducted upon that plan. But it is easy to suppose that such a nocturnal ramble could not promise much advantage to those whose object of pursuit was the study of natural history.

The inhabitants of the island are beset with religious prejudices from their earliest infancy. The children came running out of their habitations to enquire if we were of their religion; and we contented ourselves with commiserating the unfortunate beings upon whom monkish bigotry and intolerance exert with unbounded rigour their pernicious sway.

Most of the garden-walls in the country beyond Laguna, are ornamented with the beautiful plant called trichomanes canariense.

As we approached Orotava, our road led us down a very gentle declivity. We saw no more such barren mountains as in the vicinity of St. Croix, where the luxuriance of the vegetable kingdom is only an indication of the sterility of the soil; but verdant banks covered with vineyards, the produce of which constitutes the chief wealth of the island. The shrub termed bosea yervamora grows here in low situations.

At five o'clock in the evening we arrived at Orotava, where we were received by M. de Cologant, in the most hospitable manner.

Two vessels, an English and a Dutch, were then at anchor in the road-stead, in order to take in a cargo of wine. The landing-place here is much more difficult of access than that at St. Croix, on which account this harbour is less frequented.

M. de Cologant's wine-vaults were an object well worthy of our attention; as the wines of the island are the principal commodity in which this opulent merchant trades.

Amongst the different kinds of wine which they contain, there are two sorts that have qualities very distinct from each other; namely, the sack, or dry wine, and that which is commonly known by the name of malmsey. In the preparation of the latter, care is taken to concentrate its saccharine principle as much as possible.

The price of the best wine was then 120 piastres per pipe, and that of the inferior sort 60 piastres. It is necessary however to remark, that I here speak only of the price at which it is sold to strangers; for the same wine which they buy at 60 piastres the pipe, is sold to the inhabitants of the island for six and thirty.

When the fermentation of these wines has proceeded to a certain length, it is the custom to mix with them a considerable quantity of brandy, which renders them so heady, that many persons are unable to drink them, even in very moderate quantity, without feeling disagreeable effects upon the nervous system from this admixture.

We were assured that the island generally yields thirty thousand pipes of wine in a year. As it does not produce a sufficient quantity of corn for the consumption of the inhabitants, a part of the produce of the wines, which are sold to strangers as Madeira wine (and indeed they differ very little from it in quality), is expended in the purchase of this indispensably necessary article of sustenance.

Although the olive thrives very well in this island, it is very little cultivated. The different species of the palm-tree that are to be met. with in some of the gardens, are cultivated only for curiosity.

We had been assured, before our departure from St. Croix, that we should find the summit of the peak already covered with snow. I had not thought it necessary to take a barometer with me at setting out; but I sound at Orotava that I had been led into a mistake; and there I was unable to procure this instrument of observation.*

[* We read, in the account of the Voyage of La Pérouse, that when the ship lay at anchor in the road of St. Croix, the mercury, in the barometer that Lamanon had taken with him, fell at the peak of Teneriffe to 18 inches 4 lines, whilst the thermometer indicated 9.7° above 0, though, at the same moment of time, the barometer stood, at St. Croix, at 28 inches 3 lines, and the thermometer at 24½°.]

We purposed to proceed very early the next morning on our journey. But that happened to a festival day, and our guides could not be persuaded to set out before they had heard mass; some of them had even heard three already: as for us, we waited for them with the most impatient solicitude, when our uneasiness was redoubled by being informed that we ought to consider it as a very great indulgence if they would agree to travel at all on so high a festival. They were, however, at length ready to accompany us, about nine o'clock in the forenoon.

Having left the town, we pursued a track that often led us up very steep ascents, from whence we observed enormous masses of mountains piled one upon the other, and forming a sort of amphitheatre round the base of the peak. On their brows we frequently met with level spots that served us for resting-places, where, after having fatigued ourselves with climbing up the rugged paths, we stopped for a short time to take breath, and acquire fresh courage for ascending the higher mountains.

Our guides were astonished to observe that some of us chose to go on foot, contrary to the custom of the greater part of those who make the tour of the peak; and incessantly admonished us to ride upon the mules which they led along with them.

After having passed through some fine plantations of vines, we found ourselves surrounded with chestnut-trees, which cover the most elevated regions of these mountains.

In the clefts between the mountains, I observed the polipodium virginicum, and several species of the laurel that were new to me, amongst the rest the laura indica of Linnæus.

Although we purposed to perform our journey within a space of not many days, we ought to have provided ourselves with a larger stock of shoes; for even the strongest soles were soon ground to pieces by the lava on which we walked.

It was near noon when we arrived at the height of the clouds, which spread a thick dew over the brush-wood through which our road led us.

One should think that the abundance of rain which falls upon these heights, in consequence of the natural propensity of the atmosphere,* must give rise to a great number of springs. They arc, nevertheless, very rare; as the earth is not sufficiently attenuated to retain the water, which filtrating through the volcanic soil, discharges itself, for the greater part, into the ocean, without collecting into regular streams.

[* We may here remark, that when high mountains become much heated by the rays of the sun, they act as a kind of stove, by which the superincumbent atmosphere is elevated in consequence of the dilatation which it undergoes. Hence arises the moisture of the more distant part of the atmosphere, which, rushing in to supply the place of that which has been sent into higher regions by the action of the heat, carries with it the clouds suspended in it; as I have had frequent opportunities of observing at Mount Libanon, where this phœnomenon never fails to take place about five o'clock in the afternoon during the heats of the month of September, unless some violent current of the atmosphere should happen to counteract its natural disposition. Perhaps this may be the sole reason of the attraction that appears to exist between mountains and clouds.]

As soon as we had surmounted these thick clouds, we enjoyed a spectacle beautiful beyond conception. The clouds heaped up below us appeared blended with the distant ocean, and concealed the island from our light. The sky above us formed a vault of the most transparent azure, whilst the peak appeared like an insulated mountain placed in the midst of a vast expanse of waters.

Soon after we had left the clouds beneath us, I observed a phœnomenon, which I had formerly had occasion to remark, during my stay amongst the high mountains of Kesroan in Natolia. It was with new surprise that I saw the outlines of my figure, delineated in all the beautiful tints of the rainbow, upon the clouds below me, situated opposite to the sun.

The decomposition of the rays of the sun, by contact with the surfaces of bodies, affords a very satisfactory explanation of this splendid phœnomenon. It exemplifies, upon a large scale, a fact well known to natural philosophers; namely, that when the rays of the sun are made to pals through a small hole in the window-shutter of a darkened chamber, so as to fall upon any object within it, they represent the outlines of the object in all the various colours of the rainbow, by being collected with a prism and thrown upon white sheet of paper.

We now had to cross a prodigious heap of pumice-stones, amongst which we observed very few vegetables, and those in a very languishing condition. The spartium was the only shrub that could support itself in these elevated regions. It was very troublesome walking upon this volcanic soil, as we sunk into it up to the middle of the leg. We found some blocks of pozzolana sparingly scattered among the pumice-earth.

At nine o'clock in the evening we took up our abode for the night in the midst of the lava. Some large fragments that we found, were our only shelter against the east wind, which blew with considerable violence. The cold was very intense at this height, where nature has not consulted the convenience of travellers, as very little wood is found here; so that the scanty fuel that we were able to collect, was not sufficient to prevent us from passing a very unpleasant night.

The day at length began to dawn. We left some of our guides with their mules at the place where we had spent the night, and proceeded on our journey to the peak, which we were now in haste to accomplish.

We continued, for the space of an hour, to travel over large heaps of fragments of a greyish coloured lava, amongst which some blocks of pozzolana were scattered, as also, huge masses of a very compact blackish glass, which bore a great resemblance to the coarse glass of bottles. This glass though formed in the vast crucibles of the mountains at the time of their combustion, might become very useful in the arts; for being already completely manufactured by the hand of nature, it would only require to be exposed to the action of the fire in order to fuse it anew, and render it susceptible of being moulded into all the forms that the hand of man is able to give to it.

We arrived at the mouth of a cavern called la queve del ana, the orifice of which is full four feet and a half in diameter. As its cavity runs for a length of more than six feet in an almost horizontal direction, we were not able to reach the bottom otherwise than by descending into it with the help of a rope. We found that it contained water, the surface of which, as was to have been expected at this height, was covered with ice about an inch and a half thick. We immediately made a hole in the ice, and regaled ourselves with some excellent water. I did not feel any of those disagreeable sensations in the throat, which I have often experienced on the French Alps, from drinking the water which issues from the foot of the Glaciers; although the cold of the water in this cavern was one degree lower than that generally indicated by the water of the Glaciers, for upon plunging a thermometer into it, it fell to the freezing point. It seems that the disagreeable pricking sensation occasioned by the water of the Glaciers in the internal fauces, arises from its being deprived of its atmospherical air.

The roof of the cavern was covered with crystals of saltpetre.

Piron, who had been indisposed for several days, found himself so overcome with fatigue as to be unable to proceed any further. Deschamps also chose to remain with him at the cavern; as for the rest of us, we set forward on our ascent to the summit of the peak.

Having reached its base, we saw it elevate itself before us in the shape of a cone, to a prodigious height, forming the crown of the highest of there mountains. From this spot our view extended over all the rest of the mountains, which seemed to form so many gradations, that must first be surmounted before we can arrive at this commanding eminence.

At the place called La Ramblette, situated the north-east side of the peak, our curiosity was excited by some clefts made in the rock, a few of which were three inches wide; the rest were merely cracks, from which issued an aqueous vapour that had no smell, although the sides of the chinks were covered with crystals of sulphur, shooting out from a very white earth, which appeared to be of an argillaceous nature.

A mercurial thermometer being introduced into one of the clefts, the quicksilver rose, in the space of a minute, to 43° above 0 of Reaumur's scale. In several of the others it did not rise higher than 30°.

We were now engaged in the most toilsome part of our journey, the acclivity of the peak being exceedingly steep. When we had surmounted about a third part of the ascent, I made a hole about three inches deep into the earth, from whence an aqueous inodorous vapour issued, and though the heat of the surface of the earth was not greater than it usually is at an equal elevation, upon plunging a thermometer into it the mercury rose to 51° above 0.

The spartium supra nubium was the last shrub that I noticed before we arrived at the foot of the cone; but there is an herbaceous plant which, notwithstanding its apparent delicacy, vegetates even in still higher situations. I mean a species of violet with leaves somewhat elongated, and slightly indented at the edges; its flowering time was already past. We observed it to grow quite near to the summit of the peak.

The vapours of the atmosphere not being able to rise so this height, the sky presents itself in the purest azure, which is more bright and dazzling than what we can see in the clearest weather of our climates. Though some scattered clouds hung in the atmosphere far below our feet, we had still a very perfect view of the neighbouring islands.

The cone is terminated by a crater, the greatest elevation of which is on the north-east side. Its south-west side has a deep depression, which seems to have been produced by the linking of the ground.

Near to the top are several orifices about three inches in diameter, from which a very hot vapour issues, that made Reaumur's thermometer rise to 67° above 0, emitting a sound very like that of the humming of bees. When the snow begins to fall on the summit of the peak in the latter part of the year, that which falls upon these orifices is soon melted by the heat. The sides of these holes are adorned with beautiful crystals of sulphur, mostly of the form of needles, and same of them arranged into very regular figures. The action of the sulphuric acid combined with the water, effects such a change upon the volcanic products of this place, that at first sight one might mistake them for very white argillaceous earth, that has acquired a high degree of ductility from the moisture constantly issuing from the above-mentioned apertures. It is in this kind of earth that the sulphuric crystals which I have spoken of are found.

The decomposition of the sulphur, and the volcanic products, form an aluminous salt that covers the ground in needles, which have very little cohesion with each other.

The thermometer, when placed in the shade at the height of about three feet from the surface of the ground at the summit of the peak, rose in a quarter of an hour to 15° above 0. No sensible variation was observed upon changing its distance from the earth, even by six or eight feet, which gives us reason to believe, that the internal heat of the ground in this place, though so very great, has little influence upon the temperature of the atmosphere. Besides, the air of the atmosphere might easily be heated at this height by the rays of the sun to 15°, as a higher temperature is often experienced at the foot of the Glaciers. I have often known the thermometer to stand at 20 above o upon Mount Libanon, though placed quite close to the snow.

The declivity of the mountain facilitated our return, and we descended much quicker than we had ascended. It was already evening before we reached the place where we had passed the preceding night. The almost total want of sleep, which we had experienced in consequence of the intense cold, gave us little courage to spend another night at the same place. We therefore shed to proceed immediately farther, in order to seek a better flicker upon some of the neighbouring mountains; but as our guides would not move a step before the moon rose, we were compelled to remain there till near midnight, waiting for its appearance. With the assistance of its feeble light, we descended over the pumice-stones, following pretty closely the track which we had made for ourselves in our ascent.

After a march of four hours, the brush-wood, which grew very thick, obstructed our way so much, that we were obliged to halt till day-break. We had here abundance of fuel, and made ourselves amends for the cold of the preceding night, by immediately kindling a very large fire. Most of our company were so very much fatigued with their toilsome journey, that they had no other with left than to make the belt of their way back to St. Croix; although we had agreed at letting out from Orotava, that we would return by the opposite side of the mountains. But as we were no longer all of the same mind, it was settled that those who had already satisfied their curiosity, should return to the ships; whilst the gardener and myself alone resolved to complete our first design. All our guides wished to accompany those who were returning to the ships, so that it was with great difficulty that I could persuade one of them to attend us.

I was gratified with finding among the plants that grew on the sides of the rocks, the campanula aurea, the prenanthespinnala, the adiantum reniforme, and a species of the ceterac, remarkable on account of its leaves, which are much larger than those of the European species.

As these mountains afford very little water, we directed our course towards a small habitation, where we presumed we should find ourselves near to some stream of water. We were not disappointed, for we came to a very fine spring of delicious limpid water, which lost itself again under the ground, after having but kin appeared above its surface.

Apple-trees loaded with fruit adorned the garden of these peaceable cottagers. This fruit tasted so delicious to the servant who accompanied us, that he took it into his head, whilst we were employed in viewing the premises, to make an exchange that gave us a very poor idea of his foresight. He had given away our whole store of flesh-meat for some of these apples, without taking a moment's consideration whether or not they would be an equally good provision for us in travelling the mountains. We swore to ourselves that we would never on a future expedition leave our stores in the charge of such an œconomist. In general it may be remarked, that the servants employed at sea are almost wholly unfit for service on shore.

At the close of the evening we were far from any habitation of men. About nine o'clock we reached a village, the inhabitants of which can certainly not be accused of carrying the virtue of hospitality to a blameable excess. It was not without the greatest difficulty that we were able to procure shelter among them. As we did not understand the Spanish language, we were obliged to make use of signs to express our meaning, a language that, in the night time at least, is a very impeded means of communication; but our guide, who was no less desirous of going to bed than we were, went knocking in vain at one door after the other, till having gone round almost the whole village, we at length found two charitable souls who agreed to harbour us.

We were immediately served with a frugal repast, during which the house was lighted in the manner that is practised by some of the inhabitants of the Alps. They set fire to small splinters of very resinous wood, stuck into the wall, which afford plenty of light, but throw out a great deal of smoke. One of our hosts took the charge upon himself of lighting new splinters of wood as fast as the former were confirmed.

We stood much more in need of sleep than of meat, and hastened to enjoy a repose, which proved the more delectable, as we were here no more incommoded with the cold we had experienced on the high mountains.

On the following day, the loth, I went on board with my collection of volcanic products and some very fine specimens of plants, such as the tenerium betonicum, the eschium frutescens, &c.

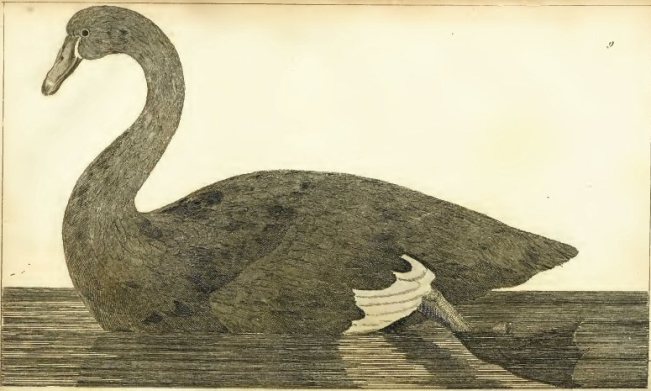

The birds known by the name of Canary-birds are cry common in the lower regions of these mountains; their colour is a brown mixed with various other hues, and their plumage is not so beautiful in their wild state, as it becomes when they are domesticated. Some travellers have asserted, that an indigenous species of the parrot is found in there islands; but I have never seen any in my excursions, and several credible persons among the inhabitants have assured me that this assertion is destitute of foundation.

A very stiff gale, which sprung up to-day, caused the sea to swell to such a height, as to drive on shore the pinnace of the Esperance, after having overset it upon one of the sailors, who could not be extricated in less than a space of several minutes. He was already suffocated to a great degree; but the means usually employed in these cases proved successful in restoring him to animation.

Whilst I here express my gratitude to the garrison of St. Croix, for the alacrity with which they hastened to the relief of this unfortunate sailor. I cannot pass over in silence a piece of knavery committed upon this occasion by some of the natives.

Whilst we were administering our assistance this man, we had hung up his clothes to dry, little suspecting what should happen. Some of the inhabitants of the town, perhaps conceiving him already dead, thought sit to appropriate his clothes to the use of the living; they were accordingly carried off, and all pursuit after the robbers was in vain.

Citizens Riche and Blavier, engaged in the study of natural history, had undertaken a journey to the peak the day after we had let out upon ours; but they did not succeed in reaching the summit; for whilst they were still at a considerable distance from it, their lungs being unable to accommodate themselves to the rarefied atmosphere, they were seized with a spitting of blood, which obliged them to relinquish their enterprize.

The following days were employed by us in visiting the environs of St. Croix, where the country is in general very barren.

The town is very thinly peopled, even in proportion to the smallness of its extent; though the harbour here is more frequented than any other in the island. The Spaniards have introduced here their own manner of building. The distribution of the internal part of the houses is, the same with that which they practise in Europe, without any of those modifications which the difference of the climate requires.

The Governor-general of the Canary-islands usually resides at St. Croix. There are several convents of monks and nuns in this place. One of the parochial churches here is equally remarkable for the tasteless profusion with which the gilding is lavished upon it, and the bad choice of its paintings.

In the market-place there is a fine fountain, the water of which is conveyed from a great distance by wooden pipes through the mountains. The streets are ill-paved; most of the windows are without glass-panes, lattices being used instead of them, which the women very frequently open, when curiosity, or any other motive, prompts them to let themselves be seen.

Women of condition dress after the French fashion; those of the lower ranks cover their shoulders with a piece of coarse woollen stuff, which forms a sort of cloak very incommodious in this hot climate; broad-brimmed hats of felt shelter their faces from the rays of the sun; intermarriages with the natives render their complexions darker than those of their countrywomen; and their features are upon the whole rather disagreeable.

The multiplicity of religious observances practised by the inhabitants were not sufficient to prevent the women from going, with their chaplets in their hands, to meet our tailors, whenever they came on shore, some of whom, have had to repent for a long time their having been seduced by such a superabundance of attractions.

The wine of Teneriffe, which, as I have already observed, is very heady, was likely to have been the cause of very fatal consequences to one of our sailors, who, in a fit of intoxication, committed a very heinous offence upon a sentinel. The French Consul, however, made use of his interest with the officer who had the command during the absence of the Governor-general, so as to prevent any cognizance being taken of the matter. The discipline observed on board the English ships effectually secures them from any of these disagreeable occurrences.

The Scorpion sloop of war, of sixteen guns and one hundred men, commanded by captain Benjamin Hallowell, had cast anchor in the roads on the 18th, consorted by a small cutter, They had sailed from Madeira five days before, where they had left a vessel of fifty guns, which was expected soon to arrive at Teneriffe. Commodore Englefield who commanded it, had also the general command of this small armament which was defined for the coast of Africa. These officers, aware of the danger to which sailors are exposed whilst they remain on shore, kept them as much as possible on board; and never suffered them to quit the ship but when the exigences of the armament required it. The Commodore was resolved to keep strictly to this regulation, during the whole time that he should be stationed on the coast of Africa.

The variation of the needle was found by an average of sixteen observations taken on board, fourteen of the azimuth and two of the ortive amplitude, to be 8° 7' 7" E.

The result of two observations taken by Citizen Bertrand, one of the astronomers to the expedition, on the terrace of a house in the town, gave 21° 33' E.

The observations taken on board appeared more to be confided in than the others, as they agreed with the progressive diminution of the variation which we had observed since our departure from Brest, and with the observations that had been taken long since by different other navigators.

The dip of the needle was now at 62° 25'. The same needle had pointed 71° 30' at Brest, and 72° 56' at Paris.

The place where we lay at anchor in the road of Teneriffe was 28° 29' 35" N. lat. 18° 86' [sic] E. long.

The thermometer and barometer, observed on board towards noon, varied very little during our stay in this place. The former never rose above 20° two tenths, nor the latter above 28 inches two lines.

The station of St Croix is a very excellent one, on account of the plentiful supply which it affords of all sorts of European kitchen-vegetables, cabbages excepted, which, though very small, are sold at an exorbitantly high price. Most of the orchard-fruits of Europe are likewise to be met with here, and the same domestic animals as in the ports of France.

Experience had taught us that the sheep of this island do not bear confinement on board so well as ours. The pure air which they have been accustomed to breathe on the mountains where they feed, renders them the more susceptible of injury from the impure air between-decks.

Teneriffe also affords great abundance of dried fish. They particularly carry on an extensive traffic with the species termed bonite.

Those parts of the island upon which the labour of cultivation has been bestowed, are very fertile, as is generally the case in volcanic islands. The internal heat of the earth which forms their basis, exhales towards the surface of the ground a portion of the rain-water which they have imbibed, which produces a remarkably luxuriant vegetation.

On the other hand the too slow decomposition of some of these volcanic stones, and the extreme dryness of some of the mountains, render many parts of the island unfit for cultivation. The action of the fire to which they have been exposed at different periods after long intervals, as attested by historical records, together with the shelter which they receive from the plants peculiar to those situations, retarding in many places that gradual decomposition which would otherwise have taken place, had they been left entirely bare.

No volcanic eruption had been known in this island, since that which broke out ninety-two years ago, till in the month of May, 1796, a new eruption took place on the south-east side of the peak, as I was informed by Citizen Gicquel, officer of marines, who spent some time at St. Croix on his return in the frigate La Régénerée from the Isle de France.

I shall insert the account which I received of this event from Citizen le Gros, Consul of the French Republic.

"On the 21st day of May, 1796, the inhabitants of St. Croix heard some hollow reiterated sounds, very like the distant report of cannon; in the night-time they felt a flight trembling of the earth, and on the following morning a volcano was observed to have broken out on the south-east side of the peak. During the first days after its eruption, it appeared to have fifteen mouths, their number was soon reduced to twelve, and at the end of a month only two were to be seen, which threw out with their lava large masses of rock, that often preferred their line of projection for a space of fifteen seconds before they fell to the ground."

Before our arrival at Teneriffe our vessels had been so encumbered with their stores, that we scarcely knew how to dispose of our crew.

We depart from Teneriffe, and set sail for the Cape of Good Hope—Observations—Splendid Appearance of the Surface of the Sea, produced by phosphoric Light—The most general Cause of the Phosphorescence of the Sea-water ascertained—Four of our Sheep which we had brought from Teneriffe are thrown into the Sea—Moderate Temperature of the Atmosphere near the Line—Variation of the Compass greater on the South than on the North Side of the Equator—Easy Method of rendering stagnated Water fresh—Thick Fog, which causes the Mercury in the Barometer to rise—Lunar Rainbow—Arrival at the Cape of Good Hope.

A VERY high swell of the sea had prevented us almost two days from getting our provisions on board. We were not ready to set sail till the 23d of October.

We endeavoured at the first dawn to get under way. All our boats had been taken on board the preceding day as soon as we had unmoored; as we wished to take advantage of the land-wind, which blows here almost every morning. It was likewise necessary that we should put out to sea before the flood-tide, which was expected to let in about half an hour after five.

We held by a cable to the English corvette. I cannot omit this opportunity of commending the polite behaviour of the English captain, who gave us, in the most obliging manner, every assistance that we stood in need of to enable us to get under way. Our Commander on his part had likewise done him every service in his power; when he came to anchor in the roads a few days after our arrival. One of the anchors of the English sloop helped us to heave down, and having spread our sails, we steered off from the coast under a slight breeze, which did not continue long enough for the Esperance to take advantage of it, although she had unfurled her sails a few minutes after our vessel. Carried away by the flood, the force of which had not at first been perceived, the was obliged to case a final anchor, by which the hauled in order to keep off from the coast while the endeavoured to stand clear of the vessels about her.

At half after nine o'clock the stood towards us. We then directed our course S.S.E.

At noon we were in 28° 5' 40" N. lat. 18° 36' 40" E. long. At this spot we set the peak of Teneriffe E. 28° N. and the eastern point of the island of Canary E. 24° S.

We then steered, about one o'clock in the afternoon, S.E.S. with a view to pass between the Cape Verd islands and the main land. We had a pretty fresh east breeze.

About six in the evening the island Gomere bore N. 38° E.

On the 26th, the Esperance told us her longitude, after having enquired to know ours. The great difference between the longitude of our reckoning, and that taken by observation, threw us into some uncertainty, which induced us to bear down two rhomb-lines starboard from our former S.E.S. course; but subsequent observations determined us to resume our first direction. The weather was very fine, and we had nothing, to fear from approaching the African coast; besides, we knew from our soundings that it was many leagues distant.

On the following morning we were out of sight of land, which convinced us that the observations taken on board the Esperance were erroneous.

We crossed the Tropic of Cancer about one o'clock in the afternoon, in 20° E. long. The barometer indicated 28 inches 2 4-5ths lines.

The first fish that would bite at the hook of our fishermen, was a very fine dorado (coryphæna hyppurus). This was sufficient to put the whole crew in motion; but the fisherman had the mortification of finding only a part of its gills upon his hook, as he had drawn the line too hastily.

Since our departure, from Teneriffe the wind had blown pretty steadily from the N.E. point.

A swallow of the common species (hirundo rustica), undoubtedly lately come from Europe, followed us for some time, without lighting upon the veal; but soon directed its slight right towards the African coast, where it was sure of finding the insects on which it feeds. We were now about 28° N. lat. 22° 30' E. long.

As there was very little wind, we observed great number of the medusa caravela floating upon the surface of the water. This plant should not be touched unguardedly, as, like many other kinds of sea-nettles, it raises blisters upon the hand, that afterwards become very painful.

The species of remora, known by the name of echineis remora, generally follows the shark, as it finds sufficient nourishment in the excrements of that voracious fish. It does not, however, attach itself so exclusively to the shark as not to follow other large fishes also, and even vessels, to which it sixes itself when it is fatigued with swimming.

In the night we observed that our vessel was followed by a large shoal of dorados. As they swam much faster than we sailed, they often moved in a circular course round our vessel with incredible swiftness. Although the night was very dark, it was easy to follow them with the eye, as they leave a luminous track behind them. This phosphoric light, produced in the agitated water of the sea, appears the more brilliant in proportion to the darkness of the night, and the velocity with which the fishes move; so that we were able to discern their track very distinctly, although they swam several feet below the surface of the water.

30th. We were now in those seas that abound with voracious fillies, such as the bonito, the tunny, and others of the same class, which find plenty of food amongst the different species of fish on which they prey; the principal of which is the flying-fish (exocœtus volitans, Linn.). The bonitos that followed us were easily caught by our fishermen, though they used no other bait than a bunch of feathers, bound up so as to resemble a flying-fish, within which the hook was concealed.

We had been almost becalmed for some time, but the regular winds began to recover their force. They were again interrupted on the 3d of November by a storm, which continued during the whole night; the next morning they blew as on the preceding days. On the 6th they left us at 9° 6' N. lat. 21° E. long.

The heat was now excessive, though the thermometer was only 23° above o of Reaumur's scale.

A bird, called by Buffon goeland noir (larus marinus, Linn.), having lighted upon one of the yards, escaped from a sailor, who had climbed up the mast, in the very instant when he was about to seize it.

A prodigious number of bonitos followed us day and night; and it was a matter of great astonishment to us, that they were able to keep up with us so long without taking any rest.

The motteux of Buffon (motacilla amanthe, Linn.), fatigued with its long flight over the sea, lighted upon our vessel, and suffered itself to be taken.

We were becalmed for seventeen days in lat. 5° N. We afterwards had storms, followed by squalls, that varied from E.N.E. to S.S.W. having veered round by south.

The tempest-bird (procellaria pelagica, Linn.) is not so sure an indication of a storm, but that its appearance is often followed by a calm of several days duration. It was a pleasing sight to observe these little birds flying close to the stern of our vessel, in quest of their food, which they find upon the surface of the ocean.

We were mortified to find that the vegetables and fruits, which we had bought at Teneriffe, did not keep; as their corruption was greatly accelerated by the heat and moisture that prevails during the calms of this zone. We had reason to believe that as they had been gathered in a very hot and dry climate, they would have kept much better than those of Europe.

A small shark (squalis carcharias, Linn.) fell a victim to his voraciousness. As soon as they had hauled him on deck, he was immediately cut in pieces, and every one had his share. The shark however is very poor food; for besides the natural abhorrence which the flesh of an animal that devours human bodies must excite, it is very difficult of digestion; but at sea we cannot choose our dishes, and fresh provisions are always preferable to salted.

I found attached to the higher orifice of his stomach a number of worms of the genus doris of Linnæus. They were about an inch and a half in length, and did not easily let go their hold, although the shark was dead. I observed them now and then shoot out the two tentacula that belong to the characteristics of this genus.

The situation of the mouth of the shark, under his long upper jaw, obliges him to turn himself almost round upon his back in order to seize any object above him; so that his white belly, which the transparency of the sea-water renders distinguishable even at a great depth below the surface, points out to the fisherman the exact moment when he ought to draw his line, in order to fasten this voracious fish to his hook.

Nature has amply provided it with the means of securing its prey; for besides several rows of teeth formed in the manner most adapted for penetrating the hardest bodies, the internal part of the mouth is likewise furnished with various asperities that serve to prevent the egress of any instance that it has laid hold of.

Had we been trading to India, we should not have sailed to coiled a quantity of the fins of this fish, as they are in great request amongst the Chinese, who believe them to be a very powerful aphrodisiac.

When the air was calm the heat was extremely oppressive; the thermometer however stood no higher than 23°; although we were not more than 9° north of the equator. Our longitude was 20° 50' east. It appears that in these parts the thermometer affords a very inadequate standard of the sensible heat of the atmosphere; for though it. indicated several degrees lower than what we frequently experience in the warm summer weather of Europe; the heat threw us into a most profuse perspiration, which gave rise to very troublesome effervescenses of the blood.

Between the tropics, the mercury in the barometer stands at a very uniform height. We never observed it to vary more than an inch and a half, More or less. It generally stood at 28 inches 2 lines, although the atmosphere was often agitated by violent forms, which being generated in the interior of Africa, from the coast of which we were not more than about 300,000 toises distant, were brought over to us by winds from N.E. and E.N.E.

12th. We here caught the fish known among the ichthyologists by the name of ballistes verrucosus. A great number of a small species of whales (soufflers) swam about our ships, followed in their tardy course by sharks which fed upon their excrements.

A squall from the S.E. gave us intimation of the gales from the same quarter, that prevailed in the distant regions under the equator; though they blow there generally from the N.E. during this season, when the sun remains almost two months within the Tropic of Capricorn.