a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

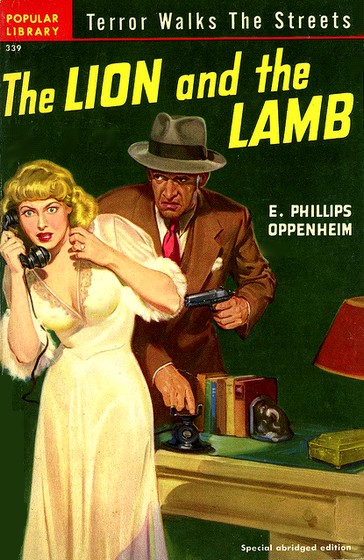

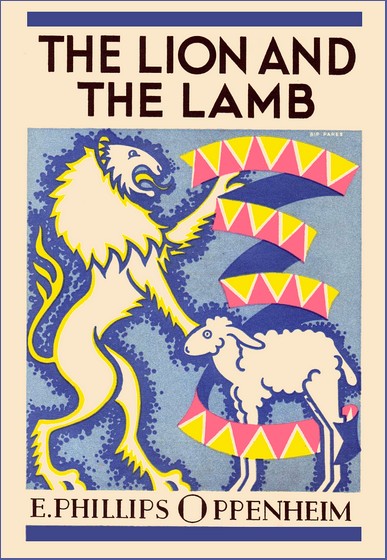

Title: The Lion and the Lamb Author: E. Phillips Oppenheim * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1203341h.html Language: English Date first posted: Sep 2012 Most recent update: Sep 2012 This eBook was produced by: Roy Glashan Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

|

· Chapter I · Chapter II · Chapter III · Chapter IV · Chapter V · Chapter VI · Chapter VII · Chapter VIII · Chapter IX · Chapter X |

· Chapter XI · Chapter XII · Chapter XIII · Chapter XIV · Chapter XV · Chapter XVI · Chapter XVII · Chapter XVIII · Chapter XIX |

· Chapter XX · Chapter XXI · Chapter XXII · Chapter XXIII · Chapter XXIV · Chapter XXV · Chapter XXVI · Chapter XXVII · Chapter XXVIII |

· Chapter XXIX · Chapter XXX · Chapter XXXI · Chapter XXXII · Chapter XXXIII · Chapter XXXIV · Chapter XXXV · Chapter XXXVI · Chapter XXXVII |

AT exactly ten minutes past nine on a gusty spring morning, the postern gate in the huge door of Wandsworth Prison was pushed open, and David Newberry, for the first time in many months, lifted his head and drew in a long gulp of the moist west wind. His original, half-shamefaced intention of hurrying into the obscurity of the moving crowds was instantly shaken. He was cut adrift from the prison by that closed door, and nobody seemed to be taking any notice of him. Nothing seemed to matter except that this was freedom. When, a few moments later, he squared his shoulders and proceeded on his way, the miraculous had happened. He had lost his sense of self-consciousness, there was a certain eagerness in his footsteps, he was on his way back into life, and there were still things which were worth while.

A young man, on the other side of the road, who had been talking to some one in a stationary taxicab, broke off his conversation, crossed the thoroughfare, and presently accosted him.

"Hullo, Dave!"

David Newberry eyed the speaker with an air of gloomy disgust. He came to a standstill unwillingly.

"What do you want, Reuben?" he asked.

"I like that," was the jaunty response. "What do you suppose I want, but you? Tottie Green isn't the man to let any of his lads down. There's a taxicab engaged," he added, pointing across the way, "and a spread at The Lion and the Lamb. We'd have made it the Trocadero if we could, but I expect they'll be keeping an eye on you for a time. Lem's over there, waiting."

"You can ride back in the taxi with Lem then, and eat the spread," David Newberry rejoined. "I want nothing more to do with you, or Lem, or Tottie Green."

Reuben laid his hand on his companion's shoulder. He was a tall, dark young man, whose clothes fitted him almost too well, sallow-faced, with sharp features, and the persuasive voice of one who has started life as a welleducated huckster.

"Dave, old man, you've got to get rid of that stuff quick," he begged. "Tottie just had to let you down. If he'd sent you even a lawyer, they'd have traced it back to us directly. Then, as regards Lem and me, it would have been a three years' job for either of us, and," he added, dropping his voice, "it might even have meant the swinging room for Lem. You got off with six months as a first offender. What's six months, anyway—There's your money in the bank and the boys waiting to see you."

David Newberry shook himself free from the other's grasp.

"You heard what I said," he repeated. "Get back to your Lem and your taxi, and leave me alone."

Reuben made no movement. His manner became even more urgent.

"You've got to get all that out of your head, Dave," he insisted. "The old man's waiting there, and Belle is all fussed up at the idea of seeing you again. Make up your mind to it. You've got to come back with me. Here comes Lem, to find out what's the matter."

"See that policeman?" the newcomer into the world pointed out. "I don't want to be in trouble again for brawling in the street, or I'd knock you down. I'm going to call him."

The man who had crossed the road presented himself— an unpleasant- looking person, with the square shoulders, the bulbous ears, and the cruel mouth of a prize fighter, which, indeed had been his profession. He grinned at David—not a pleasant expression, for his yellow, broken teeth and the sidewise withdrawal of his lips were alike unprepossessing.

"How goes it, Dave, old man?" he demanded, with a certain note of bluster in his tone. "What about a move, eh?"

"I wish to the devil you would move off, both of you," was the bitter reply. "I have told Reuben here I want nothing more to do with Tottie Green or any of you. You're a set of quitters, and I'm through with you."

The grin this time more closely resembled a snarl.

"Stop your kidding," the ex-prize fighter enjoined. "I tell you your money's waiting—a hundred and seventyfive quid—not a penny docked. The old man's going to hand it over to you himself. There's a drop of Scotch too, in the taxi."

David Newberry drew himself up, and there became even more apparent a very singular and remarkable difference between the three young men, as would have seemed almost natural, if their family histories had been known.

"Get this into your muddy brains, you fools, if you can," he said firmly. "I've done with Tottie Green, done with all of you—except you, Lem, and you, Reuben. There's a little understanding due between us that's got to come; otherwise I never want to see any of your ugly faces again. Clear out!"

The deportment of Tottie Green's second ambassador suddenly changed. He became truculent, if not menacing. He drew nearer to David, who avoided him with disgust.

"You just get this into your silly nut, Dave," he countered. "You're one of Tottie's men, and you don't quit till he says the word. There's been one or two who tried, and they got theirs sweet and proper. Try it on, if you want to. You'll feel the tickle of a knife in your ribs or the catgut round your throat before you've found your way to Scotland Yard. Come along, young fellow. You don't want us to have to buy that blooming taxi, do you?"

Cannon Ball Lem had been a fair, middle-weight boxer in his time, and he sidled up to David in unpleasantly aggressive fashion. The latter took a quick step sideways and touched a policeman on the shoulder.

"Constable," he complained, "this man is annoying and threatening me. I am just out of prison, and I haven't any desire to go back again. Will you please see that these two leave me alone."

The policeman, favourably impressed by David's voice and manner, turned promptly around. The two ambassadors from the unseen power, however, were already disappearing into the taxicab. David raised his cap.

"Many thanks, Constable," he said. "Cannon Ball Lem they used to call that young man, and he certainly had a fair idea of using his fists. I didn't want to be knocked about the first day I was out of prison."

The man grinned.

"Now that you're free, you choose your company," he advised.

David Newberry, absorbed soon in the traffic of the broader thoroughfares, went about his business with a slightly relaxed sense of tension. His first call was at a tobacconist's shop, where he purchased two packets of Virginian cigarettes and a box of matches. In the doorway, he paused to light one of the former, and his whole expression softened as he slowly inhaled the smoke and tasted for the first time for many months the joy of tobacco. Presently he summoned a taxicah, and having decided, after a seemingly casual glance up and down the street, that he was not being followed, directed the man to drive to the Strand. At a second-hand shop in this neighbourhood, he purchased a leather trunk, slightly soiled but of very superior quality, a kit bag, and a fitted dressing case, for all of which articles he paid from a bulky roll of bank notes. He drove on to a famous emporium for the sale of misfits and second-hand clothes, where, being fortunately of almost stock size, he was able to purchase a complete and expensive wardrobe, the whole of which he took away with him in his trunk. From an outfitter's, close at hand, he bought sparingly of linen and ties, having the air, whilst he made his selection, of one who is more at home in the chaster atmosphere of Bond Street. He was then driven to the Milan Hotel, where he engaged, without any trouble, a small bachelor suite in the Court. With his luggage stowed away, and the porters duly tipped, he descended to the barber's shop, and for an hour submitted himself to the complete ministrations of the establishment.

At precisely midday, he took his first drink for many months—no crude affair of whisky from a bottle in a mouldy taxicab, but a double dry Martini cocktail, served in a thin wineglass with tapering stem, cloudy and cold. The unaccustomed sting of the alcohol seemed further to humanise him. He mounted in the lift to his rooms, a glow in his blood, his sense of freedom now become a realisable and glorious thing.

Seated in an easy-chair, with a cigarette between his lips, he glanced through the telephone book and asked for the number of Messrs. Tweedy, Atkinson and Tweedy, Solicitors, of Lincoln's Inn. Mr. Atkinson, for whom he enquired under the name of David Newberry, was prompt in response. His voice over the telephone sounded urgent and anxious.

"This is Atkinson speaking. Is that—er—er— h'm??"

"This is David Newberry," the young man snapped. "Please rememher that that is the name and the style in which I wish to be addressed. When can I see you?"

"At any time you choose," was the prompt response.

"In half an hour?"

"Certainly, if I can get to Wandsworth in that time. You are still, I presume—"

"I'm out," David interrupted curtly, "or I shouldn't be telephoning. Three days short for good conduct. Milan Court 128."

"Fortunately, my car is waiting," the lawyer confided. "I shall be with you almost at once."

His client rang off. He stood with his hands in his pockets, looking eastward over the bare tops of the trees at the misty, grey-domed churches and the solid new buildings slowly creeping up. There was a gleam of the river to the right, white-flecked and swirling, a scurry of dried brown leaves on the bosom of the tempestuous wind. In detail, he saw nothing. It was a great moment for him, a moment in which he needed all his self-control, all his imagination, all his resolution. Before him lay, if he chose to take it, the broad way of an easy life, a life of forgetfulness and oblivion to all he had suffered, forgiveness— negative at any rate—of the cowards who were responsible for those lost months, and that cloud of disgrace from which he could never wholly escape. He was too strong a character to be frequently subject to these spasms of self-pity, but in those few luminous moments he was acutely conscious of the flagrant acts of injustice on the part of others—his own kith and kin—who were, after all, responsible for his disaster. Even their death seemed to matter very little. The evil was done. It was hard for him to believe that a time might arrive when he would bear them no ill will. Before that time could arrive, life would have to be kinder to him, would have to thaw the bitterness in his heart and melt the blood which he still felt cold in his veins. There was always the chance that he might become a human being again, but in this period of detachment, when only the past was of account, it seemed to him a curiously remote possibility.

IN due course, there was a ring at the bell, and in response to David's invitation, a middle-aged, very welldressed, portentous-looking gentleman, his right hand outstretched, and carrying a small black bag in his left, entered the room. Behind him, following a little diffidently, and with a despatch box under his arm, was another person of obviously less consequence. His clothes and general appearance bore the unmistakable imprint of the lawyer's clerk.

"My dear Lord Newberry!" the solicitor exclaimed. "I beg your pardon—Mr. David Newberry, since you wish it—let me offer you a hearty welcome back into =? shall we call it civilisation?"

"Very good of you, I'm sure," David murmured, affecting not to notice the outstretched hand.

"I come, hoping sincerely that you are prepared to let bygones be bygones," his visitor continued. "Believe me, there were times when I felt a positive pain in carrying out the instructions we received from your lamented father."

The young man inclined his head.

"Who is this person with you?" he asked.

"I took the liberty of bringing my confidential clerk," Mr. Atkinson explained. "There are so many details connected with the estate which you should know of, things which no one man could carry in his head. We have all the papers here. It may be rather a long affair, but it has to be done."

"It must stand over until another time," David announced. "For this morning, I shall ask you to send away your clerk—what did you say his name was?"

"Mr. Moody. He has been with the firm for a very long time."

"Mr. Moody then," David continued, turning towards him, and for the first time there was a shade of courtesy in his tone and a slight smile upon his lips—"I shall ask you to send him away for the present. Anything that is necessary can be attended to later on. I am sorry, Mr. Moody, you have had the trouble of coming for no purpose."

The elderly man smiled from his place in the background.

"It's been a pleasure to see you again—er—Mr. David Newberry, if only for this moment."

The clerk, in obedience to a gesture from his employer, withdrew, and David motioned the latter to a chair. The lawyer's right hand was still twitching, but David's eyes were still blind.

"I shall open our conversation, my—Mr. Newberry," the man of law began, "by begging you to forget everything there may have been in the past of an unpleasant nature. I can assure you that your misfortune was a bitter grief to the firm, as it naturally was to your father and brothers."

"We can take all that for granted," David interrupted, a little curtly.

"Nevertheless," the other continued, "I must repeat my conviction that if your father, if we had any of us, realised the situation properly, everything would have been different. When you have an hour to spare, I should like to go into the whole series of incidents, one by one."

David smiled bitterly.

"I fear, Mr. Atkinson," he said, "that I shall never have that hour to spare."

"It has always been my conviction," the lawyer persisted, "that your father took an unduly censorious view of your earlier indiscretions."

David shrugged his shoulders slightly.

"A little late for that sort of thing, isn't it?" he remarked. "We will leave the past alone, so far as possible. There are certain things, however, which you must understand. I arrived home from Australia penniless, and as I couldn't see why in God's name my father couldn't do something for me, I wrote and asked him. His reply came through you, and you know what it was."

The lawyer fidgeted in his seat.

"I risked a good deal," he declared earnestly, "in attempting to modify your father's attitude."

"Never mind about that. You had to carry out instructions, of course =? but here comes the point. I was in London, penniless, barely twelve months ago. I hadn't a job. I'd held a commission in the Australian army, which stopped my enlisting here. I thought of the Foreign Legion, but I hadn't the money to get to France. I wasn't eligible for the dole, even if I could have brought myself to touch it. You know what I did. I joined a gang of criminals. The first time I went out with them, they let me down. You also know the sequel to that."

"Is it worth while," Mr. Atkinson pleaded, "dwelling upon these—er—disagreeable incidents—The whole thing is finished and done with, you have come into a fine inheritance, an income of something like thirty thousand a year, and, if you will forgive my saying so, there is nothing left now but to wipe out this last very unpleasant memory, and make a fresh start."

"Eventually, perhaps," David observed. "As I have already warned you, however, I am not quite ready yet to take up my new responsibilities."

Mr. Atkinson was puzzled.

"But, my dear Mr. Newberry," he expostulated, "I don't quite see—I don't quite understand why there should be any delay."

"You wouldn't," was the brief retort, "but there is going to be, all the same."

"Perhaps you will explain."

"I sent for you to do so. I sha'n't use many words about it either. Mr. Atkinson, I am an embittered person."

All the sympathy which the lawyer could summon into his somewhat expressionless face was there, as he looked towards the slim young man with the clean-cut features and the hard grey-blue eyes, lounging in the opposite chair.

"I'm not surprised at that, Mr. Newberry."

"For fifteen years," David went on, "my father, my two brothers, and practically the whole of the family have treated me like an outcast, entirely without reason. My father and brothers are tragically dead, so that's an end of it. I can bear them no grudge, even if I can't altogether forgive."

The lawyer was grave and almost dignified.

"Indeed, Mr. Newberry," he said, "the continuation of any ill feeling on your part would be—if you will forgive my saying so—unbecoming. The whole country was shocked at the terrible accident which cost your two brothers their lives on their way back from Paris. Full details will never be known, as there were no other passengers, and both the pilot and the mechanic were killed, but it was clear that they fell from over two thousand feet on a perfectly still day on to the rocks, with, naturally, the most appalling results. No wonder when the news was broken to your father the shock was too much for him. As you know, he fainted, never regained consciousness, and died without uttering a word. Mr. Newberry, you must forget all the wrongs you suffered from your family. Death, and such death, is atonement enough."

"You are perfectly right, Mr. Atkinson," David admitted. "I can assure you I have not an unkind thought in my mind toward my father or either of my brothers. That may be considered as wiped out. But to go back again to my own precarious existence. After suffering all that I had suffered, just reflect upon what happened to me when I was driven to join this band of criminals. Again I am made the cat's-paw. I don't mind telling you, Mr. Atkinson, that law- breaking as a profession is not in my line. I had decided to quit it before that first j ob. Then see what happened. There were three of us concerned in the affair. It was well enough planned, and there was plenty of time for all of us to have escaped. My two companions, however, got the funk, locked the door on me, got away themselves, and left me to face the music."

"Disgraceful!" the lawyer exclaimed.

"So disgraceful," David agreed, "that before I enter into my inheritance and my new life, I am going to break up that gang, whatever it costs me."

"But my dear—Mr. Newberry," the lawyer protested, "why on earth, in view of your wonderful future, should you run the slightest risk in dealing personally with this band of criminals? I ask you to consider the matter seriously. Is it worth while?"

"It is not only worth while, from my point of view," David confided, "but it has become a necessity."

"I fail to follow you," the lawyer confessed.

"If I don't go for them, they're coming for me. It seems that they don't allow seceders, and they have already ordered me back to my place. As soon as they find out that I am a rich man and am not coming, there will be trouble."

Mr. Atkinson was honestly shocked.

"But, my dear Mr. Newberry," he expostulated, "let me entreat you to accompany me at once to Scotland Yard. Adequate protection shall be afforded to you. To that I pledge my word."

"You think so," David observed, with a faint smile.

"I'm afraid you don't know my friends."

"Why not take Scotland Yard into your confidence concerning them," Mr. Atkinson urged. "I have always understood that the band of criminals with whom you were temporarily associated was one of the most dangerous in London. The police would move for you against them with the utmost pleasure. You ought to be able to give them valuable information and place yourself in safety at the same time."

David shook his head.

"I'm afraid that you are very much a layman in such matters, Mr. Atkinson," he regretted. "There's just one thing the venomous person who was my late Chief is proud of, and that is that no man has ever squealed and lived for twenty-four hours."

"Squealed?" the lawyer murmured questioningly.

"Given the show away — turned king's evidence," David expounded. "I'm not afraid of threats, but I took the oath like the others, and I really don't think that I could bring myself to break it. I swore that, whilst I lived, I would never give away to the police or any one else the various lurking places of the gang, the names of any of them, or the headquarters of their leader. I believe, from what I have been told, that in the last six years seven people have taken the initial step towards breaking their word, and not one of them lived for twenty-four hours."

Mr. Atkinson mopped his forehead. He was genuinely distressed.

"You must forgive me—you must really forgive me, Mr. Newberry," he begged, "if I venture to say that your point of view is outrageous."

"In what way?" David queried.

"How can your word of honour be binding to a band of criminals who, on their part, have already taken advantage of you, and from whom you acknowledge yourself to be still in danger?" the lawyer demanded.

David stroked his chin thoughtfully.

"The treachery to me," he pointed out, "was not on the part of the gang but on the part of two members of it only. Those I am proposing to deal with privately. So far as regards the rest, they have carried out what they imagined to be their part of the bargain. They sent a taxicab to meet me at the prison this morning, with a bottle of whisky to promote good feeling. They had a feast prepared for me, and my share of the result of the burglary has been carefully put on one side and is waiting for me. They've carried the affair through soundly, from their outlook."

Mr. Atkinson was very nearly angry. He spoke with resolution and vigour.

"The sooner you abandon these quixotic ideas the better, Mr. Newberry," he said. "You can't treat thieves like honest men. The Chief Commissioner at Scotland Yard is a friend of mine. I propose that we visit him at once, or, better still, let me ring him up and invite him to lunch."

"Nothing doing," was the terse reply. "You have some vague idea, Mr. Atkinson, of what my life has been, but let me tell you this: I have never lived without adventure, even though it has cost me dear, and I have never broken my word to man, woman, child, or thief, although that has cost me dear sometimes, too. I am taking this little job on outside the police; that is why I wanted to see you at once."

The lawyer was nonplussed. Perhaps he recognised impregnability; at any rate, he acknowledged temporary defeat.

"The time will probably come before long," his distinguished client concluded, "when I may be prepared to assume my title, to occupy my houses, and to visit my estate. Until then, I require you to keep my whereabouts an absolute secret both from my relatives and all enquirers, whoever they may be. I will sign a power of attorney, if necessary, and you will continue to manage my affairs as before."

Mr. Atkinson was touched and eager. The hard, legal tone of some of the letters in which he had conveyed messages from the late Earl of Newberry to his prodigal son had caused him many a groan in the light of subsequent events. He leaned a little forward, moistening his lips and endeavouring to keep his voice steady.

"Do I understand you, my lord—I beg your pardon, Mr. Newberry—correctly?" he asked. "It is your wish that we continue to administer your affairs and act as your agents for the present?"

"That is my wish," David assented. "In the meantime, I am in need of money. There will be no difficulty about that, I suppose?"

"Not the slightest. We are really almost ashamed to disclose the fact that the balances at your various banks amount to nearly a hundred and seventy- five thousand pounds. This, too, after we have invested quite freely of late."

"At which bank have I the largest balance?"

"You have sixty-nine thousand pounds at Barclays'. I have here all the cheque hooks. Barclays' is the top one. It will be necessary—I regret very much to trouble you— but it will be necessary for you to accompany me there to demonstrate your signature."

"I will do that at once," David decided, rising to his feet. "My campaign will probably cost money."

The two men left the room together:? the lawyer with an unexpectedly light heart. His client's mad scheme was depressing, but he had looked for worse things.

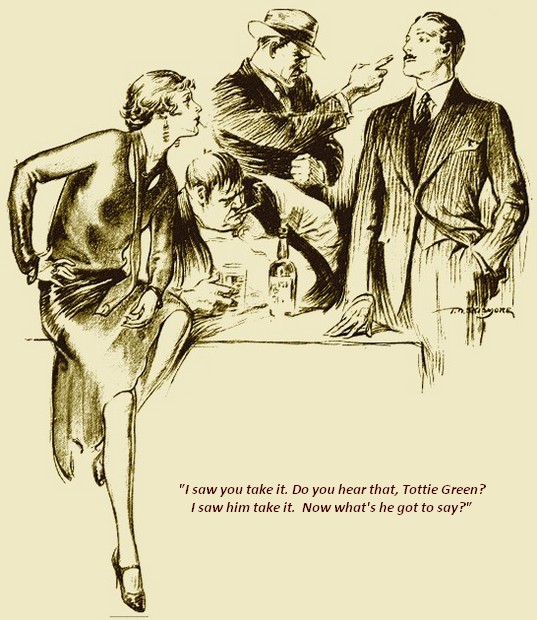

IN some odd and varying manner, every person in the hideous corner room on the first floor of the Lion and the Lamb public house seemed to possess something in common with its appalling ugliness. Tottie Green, renowned in criminal circles from Limehouse to Seven Dials, a mountainous heap of flesh, sat in his specially constructed easy-chair, upholstered in crimson velvet plush, coatless, his unbuttoned waistcoat freely sprinkled with tobacco ash, beads of perspiration from the heat of the room he loved standing out upon his coarse, low forehead. Cannon Ball Lem, in a suit of checks of music-hall size, the front of his hair plastered in two little curls over his forehead, and wearing bright yellow boots, represented the oldfashioned race of prize fighters as completely as the room itself had passed out of date with the ornate public houses of the last decade. The girl stretched upon the sofa, also upholstered with crimson plush, at first sight seemed to possess only the attractions of the barmaid type. She was large, richly but unbecomingly dressed, with flowing limbs, masses of golden hair, hazel eyes, a large pouting mouth, and over-beringed hands. The room itself was Tottie Green's headquarters and abode. It represented to him everything he had desired in life. The furniture was all of one pattern and had been proudly chosen in the Tottenham Court Road by the proprietor of the Lion and Lamb when he had furnished his corner public house in the purlieus of Bermondsey. There were two scratched mirrors with gilded frames upon the walls, whose only other adornments were advertisements of whisky and other alcoholic beverages. The carpet was thick and might once have been expensive, but it was stained in many places, and much of the cigar ash which had escaped Tottie Green's waistcoat seemed to have found an eternal resting place in its pile. There were a few cheap vases upon the mantelpiece, decanters and an open box of cigars upon the table, an empty bottle of wine lying on its side, a floating cloud of cigar smoke, and many indications that the heavily curtained window had remained closed if not for weeks, at least for days.

"I guess our young gent ain't coming," Cannon Ball Lem observed, without removing the cigar from the corner of his mouth. "Think I'll drop down and have a game of billiards with Harry."

"You stay where you are," his patron and Chief growled.

"He'll come fast enough. They generally do when Tottie Green sends for them."

The girl raised herself a little on the sofa and removed the cigarette from her lips. There was something lionesslike in the grace of her attitude, as she leaned with her elbow on the back of the couch, her cheek in the palm of her hand.

"What's all this talk about?" she demanded. "Why don't he come for his money?"

"He don't seem to need it," her guardian confided. "He ain't touched a bob from us, and there he is driving about in a fine motor car and staying at a West End hotel."

She laughed.

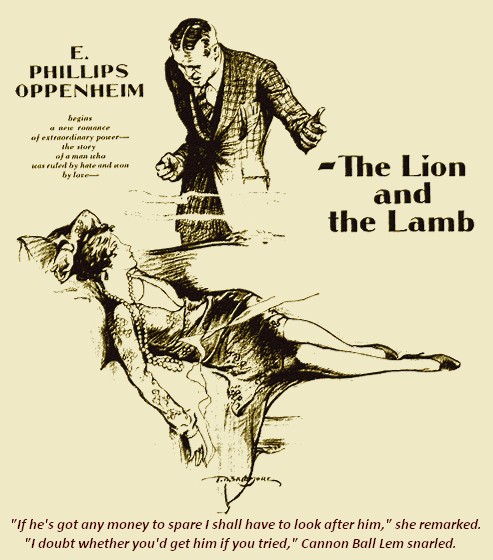

"If he's got any money to spare, I shall have to look after him," she remarked.

"I doubt whether you'd get him if you tried," Cannon Ball Lem snarled. "You should have heard him talk to us up at Wandsworth. He's got some of them fine gentleman manners with him I can't abear. I'd like him in the ring for five minutes. I'd spoil his beauty."

"Don't do anything of that sort until I've made up my mind whether he's worth while," the girl yawned. "If I want to get him, I shall, so you needn't fret about that, Lem, or any of you. What's doing these days? I want some more jewellery."

"We've three of the lads out Hampstead way to-night," Tottie Green told her. "Might be a fat little job, but small. There's another affair I've marked down for some time, but our lads are getting too well known. That's one reason why I want to keep Dave."

"If you wanted to keep him, what did you start with selling him for?" she asked lazily.

"The lads did that," her guardian replied, puffing asthmatically. "Reuben was in the show, and if they'd nabbed him it might have meant the swinging room."

The girl rose to her feet and lounged over to the looking-glass. Her hands toyed ineffectually with the great coils of fair hair, which in their abundance and vitality seemed never to have known the restraining hand of a coiffeur. She turned around and looked about her disdainfully.

"Daddy Green," she complained, "this is the foulest room in London. I think that I shall leave you all and start on my own."

"What's the matter with the room?" her guardian demanded in bewilderment. "It's just the sort of place I always meant to have, all my days—the kind of headquarters to sit in and do nothing but make plans. Don't you go and spoil it all, Belle. Where would you go to if you left here, I wonder?"

"Up the West End," the girl replied thoughtfully. "I should like to go on the films. Think I shall, too."

Tottie Green began to shake. His enormous stomach heaved and quivered. He perspired more freely than ever. Yet, notwithstanding his general appearance of impotence, there was a terribly menacing look about his eyes and lips.

"If you did that, my girl," he threatened, "you'd be sorry for it."

"My God, the boys were right!" Cannon Ball Lem, who had been looking out of the window, declared. "Here he is, in a motor car, with a chauffeur in livery, getting out as bold as brass. Isn't he the toff too! I ain't sure that I want him back, guv'nor," he added, turning to his Chief.

"I fancy him and me'd fall out."

"You'd probably get what you're asking for if you did," the girl mocked. "You've gone a bit to seed, you know, Lem."

There was a knock at the door. David Newberry entered, closing it behind him. For a moment, he stood still. The girl was watching him, her hand resting lightly upon her hip, her hair aflame against the common, incandescent light. She smiled a welcome to him.

"Well, Mr. Bad Penny," she said, "come to see the old folks at home, eh?"

He acknowledged her greeting courteously but without enthusiasm, and, advancing farther into the room, laid his hat and stick upon the table and drew off his gloves. He nodded curtly to Tottie Green and ignored Cannon Ball Lem altogether. They watched him, a little stupefied. He had had time to visit his tailor, and he was wearing clothes of a cut and style outside the range of their experience. He was a great deal more assured in his manner, too, than any one should have been in the presence of the great Chief of the Underworld. The old man carried a book in which seven crosses appeared at different times after the names of seven young men. Two of Tottie Green's Lambs were languishing in prison, but the seven young men had passed into oblivion, all right. Pa Green ruled his band through fear, and the composure of this young visitor in his presence was distressing. He scowled across at him.

"So you've come at last," he remarked harshly. "Taken your time about it, haven't you?"

"Well, to tell you the truth, my first intention was not to come at all," David replied. "Then I decided it would be rather interesting to know what you wanted from me. Besides," he added, after a moment's pause, "I have something to say to you on my own account."

Tottie Green drew one or two deep breaths. The sound itself was unpleasant, and the display of his teeth was worse. He drank from a tumbler by his side and lit a cigar. For some reason or other, it seemed to occur to him that amicable methods might be better with his visitor.

"Do you want a drink or smoke, young man?" he asked, pointing to the table on which was set out a liberal supply of decanters and cigar boxes.

"Not with you," was the calm reply.

The autocrat of the Lambs stared across the room. His eyes for the moment were bulbous. He had the air of one who could scarcely believe what he heard. From behind, Belle laughed lightly.

"That's right, Mr. Dandy," she encouraged him. "Don't let them bully you."

Cannon Ball Lem clenched his fist and looked at it thoughtfully. The man in the chair had more than ever the appearance of a fat and bloated satyr. Nevertheless, though he was shaking with anger, he still took pains to restrain himself.

"Young fellow," he confided, "there's more than one has gone to his grave for holding out against me. I don't allow insubordination. You joined my Lambs, and when you join you're mine until I give you your quittance, or until you buy it from me."

"Give it to me then," David demanded. "I've had enough of your Lambs."

"I don't choose to give it to you," was the angry reply.

"Be sensible, Dave lad. I need you for my work. You ain't so well known as some of the others, and you can do the gentleman stunts. That's what we're short of. You can work with Belle there sometimes, if you don't want the rough stuff, although they tell me you're a scrapper, all right."

"That's more than your lads are," David answered bitterly. "They left me alone to fight two policemen whilst they got away with the swag. If that's their idea of running a j ob, it isn't mine. I've finished. Do you understand that? I wouldn't go out with your pack of cowards again for anything in the world."

The old man was breathing heavily. Speech at that moment would have been unwise. Belle called across the room to this very bold visitor.

"What about me, Dave? Wouldn't you take me along and let me show you a few stunts? There are more ways of making money than breaking into safes."

"Thank you," David answered, "I don't want to hear of any of your stunts. I've finished with the lot of you. That is one of the two things I came here to say."

"And what might be the other?" Lem asked, sidling up a little closer to where David was lounging against the table.

"Get out of my way," the latter enjoined. "I'm going to say it to the old man there, and I want to say it face to face. You've had a pretty good innings, Tottie Green. You've sat in here, filling your stomach, and swilling, and getting hold of young men to do your dirty work a trifle too long. It's time it came to an end. You played a foul trick on me, and I'm going to get it back on you. I'm going to break you and your gang. As to those two cowards who ran away and left me to face the music down at Frankley Grange, they're going to be sorry they were ever born before I've finished with them."

There was a brief and strange silence. Cannon Ball Lem, who was a slow thinker, stood for a moment with his mouth open, and an ugly light dawning gradually in his eyes. The old man was making wicked and stertorous noises in his place. The girl was leaning a little forward, mildly amused, but watching every one closely through half-veiled eyes.

"You've got it straight from me now," David went on coldly. "I came here to give you warning. I'm just being honest about the matter. Open war. That's what it's going to be. I'm a Lamb in revolt."

"Hold on a minute, Lem," his Chief croaked. "Wait till I give the word."

David, who, warned by certain twitchings of the other's body, was standing tense and prepared, shrugged his shoulders.

"You can turn your bully loose on me if you want to," he said, "but I don't see the use. My chauffeur down below knows I've come here, and he won't go away without me. There was a policeman at the door as I came in. I should think a row up here in the Holy of Holies wouldn't do you any good."

Cannon Ball Lem was eyeing his master wistfully.

"Five minutes, Dad," he begged. "Let me have five minutes with him."

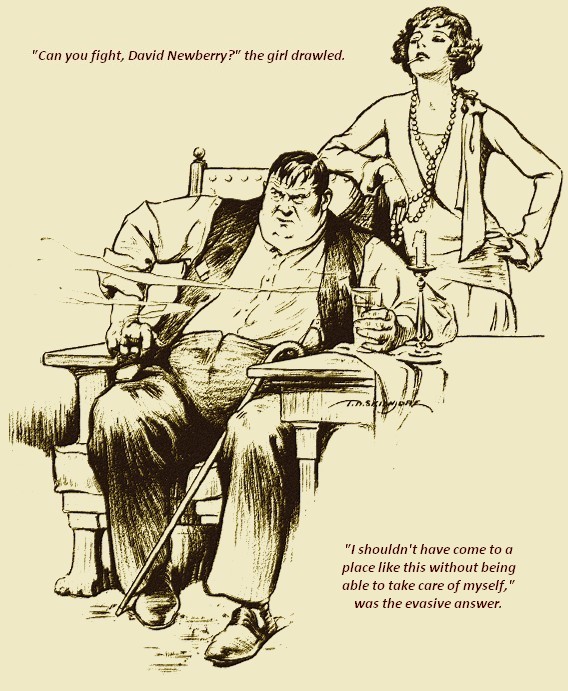

"Can you fight, David Newberry?" the girl drawled.

"I shouldn't have come to a place like this without being able to take care of myself," was the evasive answer. There was regret in her eyes as she lounged across the floor, moving as though without definite intent between the two men. With the flutter of her skirts, there stole out into the tobacco and drink-odorous room a waft of peculiar but seductive perfume, overstrong, almost nauseating, yet in its way disturbing. The memory of it lingered with David long after he had left the sordid apartment.

"I should have loved a scrap," she confessed, "but you're right, David. The police are better away from this place. Chuck it, Lem," she enjoined in a voice of authority. "A scrap between you two wouldn't do any one any good. As for you, David," she concluded, with a challenging look into his set, determined face, "you're a brave man in your own way, I suppose, but you're a fool, all the same, to come here and talk like this. You'll get what you're asking for, all right, if you don't take care. They'll have you one of these dark nights."

David Newberry prepared to take his leave.

"Let them, if they can," he rejoined. "I've learned a few of their tricks myself, you know."

"Your hundred and seventy-five pounds is here," Tottie Green growled.

"Keep it," was the scornful reply. "It will do to pay the hospital bill of some of your Lambs when I begin to talk to them."

In some unexplained manner, each one of them knew that the immediate danger of a fracas was over. Belle, with her hand upon her hip, crossed over to the plush-draped mantelpiece. She took a cigarette from a box and lit it.

"Can't I have it for chocolates?" she asked. "It's not enough for diamonds, or I should have liked a ring. Goodbye, David Newberry."

She flung a mocking smile across the room, and, with an ironic bow, he took his leave. As they listened to his retreating footsteps, she laughed again.

"He won't be much trouble," she declared scornfully. "If you really want him, I can get him all right."

CANNON BALL LEM stood at the window and scowled down into the street. The girl, with a cigarette between her lips, joined him. They watched David's unhurried departure.

"A chauffeur—in livery!" the former exclaimed, turning aside to spit into his Chief's spittoon.

"Don't do that," the girl ordered, in a tone of repugnance. "Makes me sick."

Lem growled.

"Swanking about in his own motor car and wearing toff's clothes!"

"If you ask me," the girl observed, "I think that he is a toff. He behaves as though he had been used to that sort of thing all his life."

"Where did Ned Rattigan bring in word that he was staying?" Tottie Green demanded.

"One of these swanky hotels," Lem replied—"the Milan Court, up west. What I should like to know, Guv'nor," he went on earnestly, "is where did he get the money from? He hadn't got the price of a pint of beer when he joined up."

"Maybe he's on a confidence lay," Tottie Green suggested.

The girl shook her head.

"David isn't clever enough for that," she declared. "It would need some nerve too, just out of prison. You can take my word for it, I'm right. Joined us because he was a toff down on his luck. Why, you can tell from the way he talks and wears his clothes. If any of you buy a new suit, even Reuben, you look like gawks for the first few days."

"Gentleman David, eh?" Tottie Green murmured.

"Maybe you're right, girl. What I should like to know is, where does the money come from? It seems to me that some of it ought to belong to us."

"You should have left him to me to deal with," the girl remarked, throwing herself upon the couch. "Some of it probably would have done then. The last person who ought to have been here is Lem. That made him mad to start with— Who's this?"

They listened to the flying footsteps mounting the stairs, and wondered. They heard them without anxiety, for, in what was coming, there was nothing akin to the slow, ponderous footfall of authority.

"Some one in a hurry," the girl drawled.

The door was swiftly but silently opened and closed. The young man Reuben entered. He stood on the threshold for a minute, sobbing for lack of breath, glancing eagerly around. Then he closed the door behind him and came farther into the room—a lean, cadaverous-looking young man, with smoothly brushed, glossy black hair, sombrely but carefully dressed.

"Has he been?" he demanded, almost fiercely.

"Has who been?" Tottie Green enquired.

"Dave—blast him!"

"Yes, he's been," the other acknowledged, his watery, bulbous eyes fixed curiously upon the newcomer, searching his expression as though seeking to read his thoughts.

"Dave's been. What about it, Reuben? What's wrong?"

The young man sank into a chair. He was coughing a little now, and there were drops of sweat breaking through the unhealthy pallor of his forehead.

"Togged out like a duke," Lem grumbled. "Came in a motor car, if you please, with a chauffeur in livery. Turned up his nose at his hundred and seventy-five pounds. Wants to give us the go-by. I reckon the boss will see to that."

A spasm of anger enabled the visitor to recover himself.

"Togged out like a duke, eh?" he repeated. "Wouldn't have his share of the Frankley cash. Not likely! He's done better than that."

"Come into money or something?" the girl enquired lazily.

"Come into fiddlesticks," was the fierce reply. "Gawd, if I'd got here half an hour earlier! He's done us—that's what's happened—he's done us in the eye. Done you, Daddy Green! Done me! Done Lem here! Came like a duke, eh? Motor car, clothes, and all! Well, you'll never see him again."

There was a hushed atmosphere in the tawdry, smokehung room. Reuben's disjointed sentences were pregnant with some vital emotion, which became instantly communicated to his auditors. Even the girl leaned forward. No one spoke. They could sense the words framing on his lips.

"I'll tell you. He's got the Frankley Blue Diamond, the Virgin's Tear."

No one spoke. Tottie Green's huge stomach began to rise and fall. The colour mounted to his forehead. He looked like a man whose blood pressure needed serious attention. Cannon Ball Lem stood with his mouth open crookedly, unbelieving, his senses resisting those few, commonplace words. The girl swung herself off the couch and sat leaning forward, her chin upon her two clenched hands, a glorious, but terrible light in her eyes. It was she who spoke.

"You're mad, Reuben," she declared. He wiped his forehead. With the mingled agony and evil joy of his disclosure, he had become the coolest of the quartette.

"Am I mad?" he rejoined. "I have been, ever since that night, not to have suspected. You were mad too, Lem, to bustle me off and leave him behind. We got him fixed wrong that way, and he took his chance."

"Speak plain, you fool," Lem demanded.

"What do you mean by saying he's got the Virgin's Tear?" Belle insisted.

"It's perfectly plain," Reuben continued. "That old lady in the bedroom was cunning, but not cunning enough for Gentleman Dave. She gave us the keys of the safe because she was tied up and had to, but the Virgin's Tear was never there. That's why he stayed behind and got left. He'd tumbled to it. We were the mugs. The Virgin's Tear was where it always had been kept—in a small casket, at the back of the dressing table. He'd tumbled to it somehow. That's why he fought so hard. That's why he was so far behind us."

Tottie Green was still speechless. His cunning brain was at work. He was thinking, and thinking very hard. The natural savagery of the girl was shining out of her face. She, too, was trying to piece together the story, and her first impulse was to reject it.

"You're talking like the villain of a dime novelette, Reuben," she sneered. "How can you tell what took place in the room after the girl came down? How do you know he found the diamond, much more had nerve enough to pinch it? And supposing he did, supposing he was cleverer than you two blundering fools, what did he do with it—He was caught within twenty yards of the room. Do you suppose he swallowed it?"

Reuben was himself again now, and the Reuben of everyday life was a very self-composed, cynical and precise young person.

"During that twenty or thirty yards," he pointed out, "there may have presented itself through the window, or in the corridor or room through which he passed, a possible hiding place."

"Quit this and get on to facts," Tottie Green growled.

"You must have more reasons than this. Tell us why you're sure he's got the Blue Diamond. Let's have the facts, lad."

"You shall have them, all right," was the quick reply.

"I'll tell you why it's a cert. For one thing, Moss and Nathan, the fake jewellers, have an order in hand at the present moment from Lady Frankley to make up for her an imitation of the Virgin's Tear, and they had to work on specifications. She hadn't the stone even to show them."

"No proof," Tottie Green grunted. "Go on."

"Very well, then, listen to this," Reuben continued.

"Last week, the Insurance Company settled up with her ladyship. They paid her ninety-two thousand pounds, and fifty thousand pounds of that was for the Virgin's Tear."

"You're talking through your hat, Reuben," Lem declared.

"I am not talking through my hat, as you'll realise if you'll allow me to finish. The j ewels were insured with the Mutual, and the young woman who typed out the final agreement and typed the body of the cheque was Mollie Padmore."

Tottie Green wiped the sweat from his forehead and groaned.

"Jesus!" he muttered.

"The Virgin's Tear," Reuben went on, his voice becoming lower, his eyes shining like black points of light, "was amongst the stolen jewels that night, and the Insurance Company have paid for it. Did Lem here get it, or even see it? No. Did I? No. It's your Gentleman David who did us in. He hid it, or threw it out of the window, somewhere between her ladyship's room and the door which we had to lock, where he was trapped. He got word somehow to a pal, and he's touched. Rolled up in his motor car, did he? Dressed like a duke! Got a grudge against us for leaving him, eh—That's a cunning piece of bluff. He stayed behind to get the Virgin's Tear, and damned well worth while it was too."

"Been threatening us," Lem put in. "He's been down here, threatening us. Called us cowards, because we left him behind. Says he's breaking away from us. Blast him!"

"Breaking away from us, eh?" Reuben repeated. "I should think the boss might have something to say about that."

"Oh, Christ!" Lem muttered to himself in agony. "If they'd only let me give him what he deserved, he'd have been lying here now, and us waiting for him to come to, to give him some more."

There was another silence—an ominous, menacing silence. The roar of traffic in the streets below found its way in broken patches through the fast- closed windows, but in the room itself one heard nothing but the heavy breathing of the grotesque and evil figure upon the chair. He it was who first moved. He turned wheezily to one side, took up a block of memorandum paper, searched for and found with difficulty the stubby end of a pencil in his capacious waistcoat pocket. With painful effort he wrote. They all watched him. They knew what it meant when Daddy Green wrote with that particular pencil on that particular block of paper.

DAVID NEWBERRY, a few days later, came face to face with an old friend in Bond Street. He endeavoured to pass on with wilfully unseeing eyes, but the Marquis would have none of it; a large man, he blocked the pathway and made escape impossible.

"David Newberry, by all that's amazing!" he exclaimed.

"So you're about again, young fellow."

"Yes, sir, I'm out," was the toneless reply. "I passed through the little postern gate a few days ago."

The Marquis refused to wince.

"And glad of it, eh?"

"Well, I like fresh air," David admitted. "There are certain restrictions, too, about prison life, which never appealed to me."

"Don't write your reminiscences," the Marquis begged.

"We're fed up with them, Newberry. What are you going to do about things now? The world has changed for you during the last seven or eight months."

"Yes, it has changed," the other admitted. "I have a title which I don't want and a position which is useless to me. I may be able to do something with the money."

"Embittered," his companion murmured. "I thought so. Don't know that I blame you altogether, but you'll have to be reasonable. You've more friends than you know of. Every one thought that your father was terribly hard, and, although one doesn't want to speak ill of the dead, there weren't two young men in the country more unpopular than your two brothers. You've been a bad boy, of course, but I don't mind telling you that there isn't one of us in the county wouldn't sooner have you at Anderleyton than either of them. Poor chaps, they were asking for it and they got it in the neck, and that's all there is to be said about it. Now, what are your plans?"

"I haven't any," David told him, "beyond the immediate present."

"Not thinking of settling abroad, or any rubbish of that sort? Martha seemed to have got hold of that idea, somehow."

"I might," David admitted. "I should have liked Kenya in the old days, if I'd had a little capital."

The Marquis thrust his hand through the young man's arm.

"At six o'clock in the evening," he confided, "I owe it to my constitution to take a drink. You'll say stupid things if I ask you to come to the Club. We'll try the Ritz Grill Room."

They went on their way together—the Marquis of Glendower, Lord Lieutenant of the county in which David had been born, a portly, dignified man, broad-shouldered, yet with a certain sparseness of frame which spoke of athletic pursuits, and David, fretting a little, but very helpless against the friendliness of the older man. Over a whisky and soda in a retired corner, the latter abandoned all restraint.

"What did you do it for, David?" he demanded.

"I joined the gang partly out of devilishment, and partly because I was starving," the other confessed. "I literally hadn't a shilling."

"But surely," Glendower persisted, "your father couldn't have refused you a reasonable income, however small it was."

"I wrote and told him precisely the straits I was in,"

David confided. "He answered me through his lawyers. I'll show you the letter some day, if you like—rather an epic in its way. He declined to assist me with even a five-pound note."

"One doesn't wish to speak ill of the dead," the Marquis repeated, "but I always thought Henry was the hardesthearted, coldest-blooded, most obstinate old curmudgeon in our part of the world."

"Up till then," David went on, "I had never committed a dishonest deed. I joined up with these fellows primarily to get a meal, and they sent me out during the first week. I hadn't much to do with the actual robbery at Frankley, except, of course, that I was there to help. I did the fighting, and played the fool generally. My companions sold me like a couple of dirty scoundrels; they got away with the jewellery, and I recovered consciousness in hospital."

"You knocked those two policemen up a bit, though."

"They weren't badly hurt. I sent each of them a cheque yesterday."

"A dirty gang you seemed to have got mixed up with, even for criminals," the Marquis mused. David lit a cigarette.

"Yes, they're a bad lot," he admitted. "They won't last much longer, though."

"You know," his companion went on, "the troubles of your home life were absolutely flagrant. There isn't a soul who doesn't realise that you were very badly treated. I don't wish to hurry things, of course, David, but we want you back again, and I'm jolly certain that you'll be surprised at the welcome you get. People soon forget, and there are a good many of us have knocked a policeman or two about, some time or other during our lives, and ought to have gone to jail for it. In a month or two's time, or a year, say, if you come and settle down with us, not a soul will remember a thing about your little affair. I bet you could have the hounds if you wanted them before long."

"You're very kind, as you always were to me," David acknowledged gratefully.

"Well," the Marquis continued, "I'm very glad to have met you this evening, anyway. You were always a harumscarum sort of lad, and difficult to deal with, and I sort of feel that after this little escapade, unless some one talks to you seriously, you might be dropping out of sight again, and we don't want you to. Have you been to see your sister?"

"Not I."

"I don't know that I blame you. All the same, you can afford to forgive a good deal when you remember that she's lost her father and two brothers within six months."

"I fancy I should be the last person she'd want to see," David objected.

"Give her the chance of saying so, then. Jolly nice girl, Harold's stepdaughter's turned out to be. She'll be one of the beauties next season. By- the-by, would you like me to trot you round to see them all? It wouldn't be a bad idea, and I should rather enjoy it."

"Not just at present," was the prompt refusal. "It's awfully good of you, sir, and I appreciate it immensely, but I am going to ask you to keep quiet, if you don't mind, even about having met me, for a month or two. I want to lie perdu if I can."

"Up to more mischief?" the older man asked gravely. David shrugged his shoulders.

"You might think so, sir," he admitted, "but, at any rate I'm not out to defy the law or anything of that sort."

The Marquis rose to his feet.

"Well," he said, "I've got to go upstairs to sign some fellow's visitor's book. London seems packed with foreign royalties just now. You'll leave me your address, David. Come, I insist upon that."

"I'm at the Milan Court, sir," David confided, "but keep away from me for a time, please. I'm staying there as Mr. David Newberry, and I want to remain as quiet as I can for a week or so. I'll look you up directly I'm through with my little business."

"That's a promise?" the Marquis stipulated.

"Word of honour."

David turned back into Bond Street, curiously and illogically disturbed. His was one of those dispositions warped by a long course of injustice which become almost apt to resent kindness. It was like an unwanted sop, an irritating balm, for wounds which he preferred to keep open. Many more interviews like this one with the Marquis, he realised, might altogether change his settled poise towards life. He had been ill-used, and the bitterness of it was fast becoming part of himself. He was being cheated of self-pity, he reflected, with a grim little smile forced upon his lips by a latent sense of humour. In his disturbed mental attitude, he saw his way less clearly, as he passed through the crowded streets. His eyes had lost their hard, steely gleam. He was perplexed by a momentary weakness, which he discarded almost with reluctance.

At the corner of Bruton Street, he picked up a taxicab and drove eastwards. With some difficulty he found the place of which he was in search—a large building, which had once been a warehouse, at the end of a paved alley off a side street in Holborn. A black sign was painted over the entrance:

ABBS'S GYMNASIUM

BOXING. COURSES IN PHYSICAL CULTURE. FENCING.

(Terms moderate)

(Enquire within)

David pushed open the swing door, and stood for a few moments at the foot of some steps leading to the office in which two young women were typing, gazing down the long room. There was a certain amount of sparring going on in the various rings, and some vigorous work with the punch ball. A short, stout little man presently came hurrying up.

"What can I do for you, sir?" he asked cheerfully.

"Recognise me, first of all. Then I should like you to show me round."

The little man looked hard at his visitor. Suddenly a light broke into his face.

"My God, it's young Mr. David!" he exclaimed. "Glad I am to see you, sir— real glad!"

David held out his hand, which the other grasped. Suddenly a cloud darkened the gymnasium instructor's face. He coughed.

"I beg your pardon, my lord," he apologised. "I forgot for a moment. I thought you were back at Anderleyton."

"I want you to forget Anderleyton," David told him curtly. "I'm living for a short time, well—incognito—as much as I can. As a matter of fact," he went on, with a grim smile, "I've been living incognito for the last six months—a life of complete seclusion, Abbs. Hear anything about it?"

The little man coughed once more.

"I did hear as how there'd been a bit of trouble, sir," he admitted, "and very sorry I was too. And then to lose your father and brothers like that! Enough to turn any one's head."

"Let it go at that," David enjoined shortly. "I came here to talk business with you, Abbs. Who's that sandyhaired fellow there with the useful punch?"

"That's Sammy West," Abbs confided. "We're training him seriously. He's fighting at the Albert Hall next week. Then there's Teddy Levy a little lower down. He's having a rest with his sparring partner."

"Any jiu-jitsu instructors?"

"Only one at present, but I'm in correspondence with another. I tell you, sir, we could turn out as plucky a band of fighters as you'd see anywhere—fellows who know how (to use their hands and their legs, and get out of any scrap clean."

"Business good?"

Mr. Abbs scratched his head.

"It's good enough, so to speak, sir," he replied, "but, all the same, it's difficult to make it pay. We've plenty of clients just now—couldn't keep them out last night. A good many of them only comes in for half an hour's exercise. Better for them than the public house, but there ain't much profit about it."

"Show me round," David begged. "I should like to see your lads at work."

They completed a tour of the premises. Then David laid his hand upon his companion's arm.

"Take me to your office," he enjoined. "I have a proposal to make to you."

Mr. Abbs led the way up the steps to the untidylooking apartment, where a couple of girls sat typing at old-fashioned and battered desks. There were announcements of boxing contests upon the walls, and torn bills dealing with several other sporting events. One of the girls paused, with her fingers upon the keys of her machine, and looked curiously at David. The other continued her work, unnoticing. The two men passed on beyond to a smaller sanctum, and Abbs closed the door behind them carefully.

"What can I do for you, sir?" he enquired, throwing some papers from a chair and dusting it carefully. David lit a cigarette. His eyes seemed always to be wandering back to the long line of sparring youths dimly to be seen now through the glass casements.

"I heard of your establishment in an odd sort of way, a few months ago," he observed, "and when I was told it was run by a man named Abbs, I felt sure that it must be you. Seems a good many years since you were our gymnasium instructor down at Anderleyton."

"It does indeed," the little man agreed. "Your poor dad, he was one for looking after his health, he was. An hour's exercise in the morning, and an hour in the afternoon. And then your two brothers—that was fair tragic. You was the only one though, sir, as took to boxing proper. Neither of them could have stood up to you for thirty seconds."

"And didn't they love me for it!" David reflected, a little grimly. "Never mind. I didn't come here to talk about that. Listen to me carefully, Abbs. Why do you suppose you get so many of these young fellows anxious to learn boxing and jiu jitsu?"

Abbs looked at his visitor keenly. He had the air of a man not altogether at his ease. He shifted his weight from one leg to the other, and considered for a moment.

"Do you really want me to tell you that, sir?"

"It's what I came for."

"Well, then, this is how it seems to me, and naturally I've come across a few things that carry out the idea," Abbs began slowly. "There's a good many of them who come just for exercise and because they want to be able to hold their own in a tussle, but there's another lot that comes here what I'm not so sure about. Queer lads they are too, some of them."

"Tell me about them," David begged.

"You see, sir," Abbs continued, "there's a good deal of this quick, raiding robbery going on nowadays, and a young man who's clever with his fists, and knows how to use his feet and wrists, is the one who can get away with it. Mind you," he went on guardedly, "I'm not saying that you'd find many at my show like that, but I'm certain that it's at the backs of the minds of most of them."

"Gangsters," David murmured softly.

"Gangsters is the word. Why, where there used to be half a dozen bands in the country, and these pretty well confined to the race courses, to-day I should say there are fifty. The worst of them use guns or knives. I try to get into the brains of my lads here that that's where the serious trouble comes. I try to teach them to do all that is necessary in the way of defence or attack in as straightforward a manner as possible, if one might use the word."

"That's good," David approved. "Talking of gangs," he went on, "have you ever heard of the Lambs?"

Abbs shook his head doubtfully.

"Not by name, sir," he admitted. "I know there is one gang—very hot stuff too—with a leader who is supposed to live in seclusion and direct them from a distance. I don't know anything about them, though, sir, or any one else."

"It is my intention," David announced, tapping another cigarette upon the table and lighting it, "to put that particular band out of business. Do you think I could engage, and train, say, thirty of your lads, who would take the job on under your supervision and mine?"

Abbs was frankly startled.

"You'll excuse me, sir," he protested, "but surely that's a police job?"

"I'm not exactly hand in glove with the police," David explained drily. "There's money in my proposition, you know, Abbs. Quite enough to make it worth while."

The man was obviously uncomfortable.

"I'm doing very well with my little academy," he confided. "I'd rather not know what my pupils are training for. I'd rather not know what they do when they're outside these walls."

"It would be a thousand pounds down for you," David announced, with the air of a deaf man; "ten pounds a week for the lads, and fifty pounds for each one of the Lambs they tumble into jail or put out of action."

"It's real money, all right," Abbs acknowledged wistfully, "but by all accounts these gangsters are a wicked lot. There ain't one of them who don't carry a gun or a knife or something. My lads ain't used to that sort of stuff."

"No, but I want your lads trained so that they can deal with it," David explained. "With the help of jiu jitsu, there's very little in it between a man who's armed and a man who isn't at close quarters. I think I could prove that to you sometime, if we go into this little affair together. Besides, I can tell you another thing about the Lambs. They've been earning too much money. They're getting fat and lazy, some of them, and they haven't the stomach for a fight that they had in the old days."

"Was it them as played the dirty on you, my lord?" Abbs queried.

"It was," David acquiesced, "and whether you help me or not, there isn't one of them who isn't going to regret it. I can give you the cheque for the thousand now, Abbs."

"To-morrow morning, if you please, sir," the man begged. "Leave it over till then, and I'll see what can be done. I didn't want to be dragged into any business of this sort, but after all, it's you, Mr. David, and the money's good."

David, as he turned to take his leave, was suddenly conscious of a queer sense of disturbance. He was back again for a moment in that hideous public- house sitting room, a flaring palace, with its beer-stained interior. The stink of the room was in his nostrils and, mingled with it, the same half-alluring, half-nauseating perfume, with its queer suggestions of the jungle, of secret and sickly places. He lifted his head quickly. There was a rustle in the outside office.

"Where on earth does that scent come from?" he asked. Abbs looked over the top of the window.

"It's one of them damned typists," he muttered.

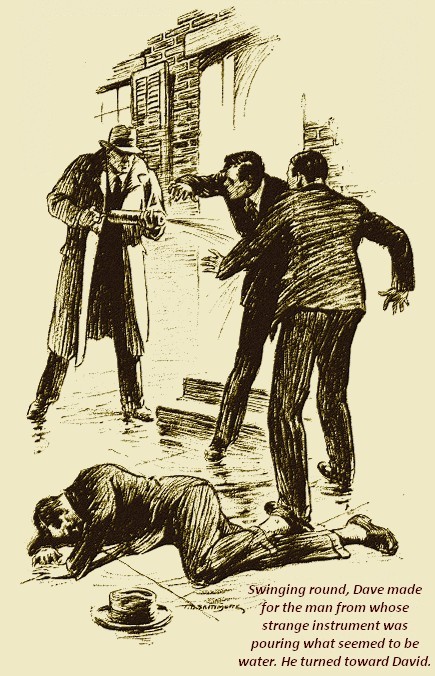

DAVID awoke some time in the black hours of the following morning, in the chamber of his suite at the Milan Court, acutely conscious that he was not alone. He leaned out of his bed and turned on the switch of his electric lamp. Nothing happened. He tried again—without result. He reached upward for the bell and found only an empty cord. The severed plug lay upon his pillow. The curtains, which he remembered distinctly having left open to admit a current of air from the window, were closely drawn. He was dimly aware of at least two, there may have been three, dark, human shapes grouped a little way from his bed. He was not a nervous person but there was something terrifying in the silence by which he was surrounded.

"Who is in this room?" he asked sharply.

There was no immediate answer. He sat up and opened his mouth to shout. Suddenly an unseen hand thrust something between his teeth; others pinioned his arms. One of those dimly visible shapes bent over the bedstead rails, and his feet were held down. He struggled for a moment furiously. Then he realised that he was at a hopeless disadvantage, and he lay quite passive, using all his senses, struggling to discern the forms of his assailants, listening for any encouraging sounds from without. It was evidently the one hour of rest between night and dawn, for the rumble of traffic over Waterloo Bridge had ceased, and a pall of silence lay over the Strand and the nearer thoroughfares of the City. He tried to speak, but only choked. Then a voice addressed him, unexpectedly near to his bedside—a familiar, silky, almost melodious voice, with a sneer underlying its smoothness.

"I am Reuben," the voice announced, "and these are two of Tottie Green's lads chosen for their muscle. We've brought you a message from Tottie Green—an official one this time—and from the Council of the Lambs, the Lambs who admitted you to membership less than twelve months ago. You know what we want."

David made no attempt at reply. Speech could only be a grotesque and incoherent thing.

"You know also who I am," the voice went on. "I am Reuben—Reuben Grossett. If I'd been at the Lion and the Lamb when you paid your visit there, you wouldn't have brought off that bluff. If I take the gag away, will you give us your word of honour not to call out whilst we talk. Nod your head if you agree."

David nodded. Anything to get that loathsome spring, bound with rubber, out of his mouth. The other deftly removed it.

"I take it you will keep your word," Reuben remarked, "but perhaps it would be as well to remind you that I am sitting within a foot of you, and that if you try to summon help, it will be the last time you open your mouth in this world. We don't merely threaten, either. You ought to know that. We keep our word."

"I shall not call out for help," David agreed, "unless some one actually comes to the door. Why should I—What harm have I to fear from you?"

"None, if you behave like a pal, and don't try any silly games," was the curt reply. "If you want to know what we've come for, I'll tell you. We've come for the Virgin's Tear, or the Blue Diamond, or whatever you care to call it—the jewel you pinched from Frankley Place."

"Then the sooner you go back again," David rejoined, "the less time you'll waste. I haven't got it."

There was a brief silence. David's eyes, accustomed a little now to the darkness, made out that there were four forms in the room and, though no voice was raised above a . breath, he was conscious of that whisper of menace, a veritable wave of evil. He realised that no one believed him.

"So far as we have heard," Reuben went on slowly, "there was only one burglary at Frankley Place that night, and we were the boys who were concerned in it. There were no other thieves about, just you and I and Lem. You stayed longest in the room where the jewels were—too long for your own safety. You followed us out—"

"Yes, I followed you out," David interrupted fiercely, "and what happened? We could all have got away. You wanted to make sure of your own safety and you locked the door—locked it against me, as well as your pursuers. Dirty cowards, that's what you were. That's what I went back to tell Tottie Green."

Again there was that little breeze of menace—an undernote of movement, half of muttered whispering. A breath of wind shook the blind against the window.

"We are here to discuss one matter, and one matter only," Reuben said, "and you've a better chance of waking up in the morning if you'll remember it. The Virgin's Tear was stolen from Frankley Place that night, from the room in which we left you. No one else could have got in and taken it. What did you do with it—You disposed of it somewhere. How? In what hiding place?"

"Why are you so sure," David asked, "that the Virgin's Tear was stolen? It wasn't amongst the other jewels. Why should you think that I discovered it?"

"We know that it was stolen," was the half-whispered reply, "because it has just come to our notice that the Insurance Company has paid for its loss. Insurance Companies don't pay without proof. You are the only man who could have taken it. You went into prison a pauper, and you come out spending money like a millionaire. Perhaps you can explain that."

"Perhaps you can explain what I did with the Virgin's Tear, then?" David countered, listening, with a faint gleam of hope, to the first market wagon rumbling over Waterloo Bridge. "It was three or four days before I recovered consciousness after the fight that night, and when I did, all my clothes had been taken away from me."

"You had plenty of chances of getting rid of it before the police rushed in," Reuben replied. "You had to pass through two rooms to get to the door by which we made our escape. There may have been hiding places in the room. On the other hand, two of the windows were open, and below you were the grounds. That's all in the way of explanations. We haven't any time to spare, Dave. We want the Virgin's Tear, or to know where you deposited it. Come through with it, Dave, or take what's coming to you."

"Do you mean to murder me?"

"We mean to get the Virgin's Tear."

"I haven't got it."

The lean, supple figure, bending over the side of David's bed, hung down in front of his eyes the illuminated dial of a watch.

"We can only give you one minute, Dave," he said shortly. "After that, you are going to pass out, or wish you could pass out,—three thirty- three. You have sixty seconds."

"If you murder me," David reminded him, "you'll do it for nothing. I haven't got the Virgin's Tear."

"You know where it is."

"I haven't the faintest idea."

The four shapes all seemed to lean toward him. There was the sound as though of an angry wind stirring amongst decayed leaves. They drew round the bed. He could feel the hot, beery breath of one of them upon his cheek. Reuben was handling a length of sinister-looking cord.

"Thirty seconds have gone," he announced.

Flat on his back, David Newberry waited for death. There seemed little to be done, poor chance of awakening any one, even if he broke his word and attempted to call out. Those long, skinny fingers, which he had always hated, were within a few inches of his mouth. Reuben was bracing his knee against the bedstead.

"Fifteen seconds, David. You're going out if you don't give us a line on the diamond."

Still no sound in the sleeping hotel. A late taxi hooted up the Strand. One or two more wagons were rolling across the bridge, but the electric standards were still alight, the dawn was still to come.

"Time," Reuben murmured.

"Time be damned!" David rejoined. "I haven't got the diamond, blast you!"

The gag was in his mouth. His wrists were held down by two of his assailants. A moment later, the cord was around his throat, drawn up tighter and tighter until it was taut. Then Reuben paused. One of the other stepped forward and handed something across the bed.

"You're in the swinging room, mate. Your last chance— going fast! Where's the Virgin's Tear?"

David made the effort of his life. The muscles of his legs and arms swelled almost to breaking point. He felt that his veins were bursting. His head seemed strangely congested. Not one thousandth part of an inch would those devilishly fastened cords give. A Houdini might have escaped from his bonds; a Samson would have failed. He felt his breath go out in one last gasp, as his strength died away. The cord around his neck was cutting now. Everything in the room was dancing. He heard the drawing of a stopper from a bottle, smelt something less sickly but more powerful than chloroform, which seemed in a single breath to take all his senses away. Without even a struggle he fell back and lay prostrate and inert upon the bed.

* * * * *

The sunlight streaming into the room awakened him. He lay still for some time, trying to reconstruct what had happened, to sort out fancy from fact. Then, still sore, he sat slowly up in bed. There was scarcely a sign of disorder in the room, and little change in it, save that the cut telephone wire lay upon the carpet, and the bell knob still reposed upon the counterpane. He sprang out of bed and gazed at his neck in the looking-glass. There was a faint red mark there, but it was barely distinguishable. And then a strange fancy came upon him. He stood quite still, his head thrown back as though he were listening. It was no fancy, after all. It was unmistakable in its penetrating, cloying sweetness—the perfume of the public-house parlour at the Lion and the Lamb. He had a curious nightmare fancy, a figment of his disordered night. He fancied that he could see her, her hand upon her hip, looking over her shoulder at him with that insolent smile. At the sound of a distant closing door he started. Then, with an effort to pull himself together, he drew back the curtains and threw wide open the window, struck the air with the palms of his hands, as though to beat out into the misty void imaginary wisps of that hateful perfume. He staggered back into the sitting room and rang the bell.

"Fill my bath and ask one of the managers to come up," he directed the valet who answered it.

A suave young man, who spoke perfect English with a slightly foreign accent, presently made his appearance. He listened to David's story with the utmost politeness. He examined the severed cords of the telephone and the electric light with much concern.

"You say that your door was bolted, sir?" he enquired.

"Not only was my bedroom door bolted," David assured him, "but the door leading into the hall, and the communicating door between my sitting room and here was also bolted."

"You seem to have taken every precaution," the young man remarked.

"I had reason to," David confided. "I happen to know that there are people in London who are ill-disposed towards me."

The reception clerk moved across the room and gently tried the door connecting with the next apartment. It was fastened on the other side.

"Who is in there?" David enquired.

"I will ring down from your sitting room and ask, sir."

In due course the young man made his report. The apartment was unoccupied, also the apartment on the other side. With a pass-key, he opened the door. The room was a small one, and empty, but the bed had been slept in.

"What about that?" David demanded. The hotel official was a little staggered. He went to the telephone which stood by the bedside and spoke again to the office. He was looking more thoughtful when he hung up the receiver.

"This room was let late last night," he announced, "through one of the waiters on our staff to a former patron of his, a Doctor Nadol, who left for Liverpool, by the newspaper train, to perform an operation."

The two men made their way back to David's room. The reception clerk glanced once more at the defective cord of the telephone and electric bell, and regretted their threadbare condition.

"You are quite sure—you will pardon the suggestion, Mr. Newberry—that you did not have a nightmare last night?"

David swallowed hard. He pointed to the two severed cords. His companion shrugged his shoulders.

"There is always something to be explained," he murmured enigmatically.