a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: The Missioner Author: E. Phillips Oppenheim * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1203021h.html Language: English Date first posted: Aug 2012 Most recent update: Dec 2016 This eBook was produced by Roy Glashan. Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

"The Missioner," A.L. Burt reprint edition, New York, 1917

The lady of Thorpe was bored. These details as to leases and repairs were wearisome. The phrases and verbiage confused her. She felt obliged to take them in some measure for granted; to accept without question the calmly offered advice of the man who stood so respectfully at the right hand of her chair.

“This agreement with Philip Crooks,” he remarked, “is a somewhat important document. With your permission, madam, I will read it to you.”

She signified her assent, and leaned wearily back in her chair. The agent began to read. His mistress watched him through half closed eyes. His voice, notwithstanding its strong country dialect, had a sort of sing-song intonation. He read earnestly and without removing his eyes from the document. His listener made no attempt to arrive at the sense of the string of words which flowed so monotonously from his lips. She was occupied in making a study of the man. Sturdy and weather-beaten, neatly dressed in country clothes, with a somewhat old-fashioned stock, with trim grey side-whiskers, and a mouth which reminded her somehow of a well-bred foxhound’s, he represented to her, in his clearly cut personality, the changeless side of life, the side of life which she associated with the mighty oaks in her park, and the prehistoric rocks which had become engrafted with the soil of the hills beyond. As she saw him now, so had he seemed to her fifteen years ago. Only what a difference! A volume to her—a paragraph to him! She had gone out into the world—rich, intellectually inquisitive, possessing most of the subtler gifts with which her sex is endowed; and wherever the passionate current of life had flown the swiftest, she had been there, a leader always, seeking ever to satisfy the unquenchable thirst for new experiences and new joys. She had passed from girlhood to womanhood with every nerve of her body strained to catch the emotion of the moment. Always her fingers had been tearing at the cells of life—and one by one they had fallen away. This morning, in the bright sunshine which flooded the great room, she felt somehow tired—tired and withered. Her maid was a fool! The two hours spent at her toilette had been wasted! She felt that her eyes were hollow, her cheeks pale! Fifteen years, and the man had not changed a jot. She doubted whether he had ever passed the confines of her estate. She doubted whether he had even had the desire. Wind and sun had tanned his cheeks, his eyes were clear, his slight stoop was the stoop of the horseman rather than of age. He had the air of a man satisfied with life and his place in it—an attitude which puzzled her. No one of her world was like that! Was it some inborn gift, she wondered, which he possessed, some antidote to the world’s restlessness which he carried with him, or was it merely lack of intelligence?

He finished reading and folded up the pages, to find her regarding him still with that air of careful attention with which she had listened to his monotonous flow of words. He found her interest surprising. It did not occur to him to invest it with any personal element.

“The agreement upon the whole,” he remarked, “is, I believe, a fair one. You are perhaps thinking that those clauses——”

“If the agreement is satisfactory to you,” she interrupted, “I will confirm it.”

He bowed slightly and glanced through the pile of papers upon the table.

“I do not think that there is anything else with which I need trouble you, madam,” he remarked.

She nodded imperiously.

“Sit down for a moment, Mr. Hurd,” she said.

If he felt any surprise, he did not show it. He drew one of the high-backed chairs away from the table, and with that slight air of deliberation which characterized all his movements, seated himself. He was in no way disquieted to find her dark, tired eyes still studying him.

“How old are you, Mr. Hurd?” she asked.

“I am sixty-three, madam,” he answered.

Her eyebrows were gently raised. To her it seemed incredible. She thought of the men of sixty-three or thereabouts whom she knew, and her lips parted in one of those faint, rare smiles of genuine amusement, which smoothed out all the lines of her tired face. Visions of the promenade at Marienbad and Carlsbad, the Kursaal at Homburg, floated before her. She saw them all, the men whom she knew, with the story of their lives written so plainly in their faces, babbling of nerves and tonics and cures, the newest physician, the latest fad. Defaulters all of them, unwilling to pay the great debt—seeking always a way out! Here, at least, this man scored!

“You enjoy good health?” she remarked.

“I never have anything the matter with me,” he answered simply. “I suppose,” he added, as though by an afterthought, “the life is a healthy one.”

“You find it—satisfying?” she asked.

He seemed puzzled.

“I have never attempted anything else,” he answered. “It seems to be what I am suited for.”

She attempted to abandon the rôle of questioner—to give a more natural turn to the conversation.

“It is always,” she remarked, “such a relief to get down into the country at the end of the season. I wonder I don’t spend more time here. I daresay one could amuse oneself?” she added carelessly.

Mr. Hurd considered for a few moments.

“There are croquet and archery and tennis in the neighbourhood,” he remarked. “The golf course on the Park hills is supposed to be excellent. A great many people come over to play.”

She affected to be considering the question seriously. An intimate friend would not have been deceived by her air of attention. Mr. Hurd knew nothing of this. He, on his part, however, was capable of a little gentle irony.

“It might amuse you,” he remarked, “to make a tour of your estate. There are some of the outlying portions which I think that I should have the honour of showing you for the first time.”

“I might find that interesting,” she admitted. “By the bye, Mr. Hurd, what sort of a landlord am I? Am I easy, or do I exact my last pound of flesh? One likes to know these things.”

“It depends upon the tenant,” the agent answered. “There is not one of your farms upon which, if a man works, he cannot make a living. On the other hand, there is not one of them on which a man can make a living unless he works. It is upon this principle that your rents have been adjusted. The tenants of the home lands have been most carefully chosen, and Thorpe itself is spoken of everywhere as a model village.”

“It is very charming to look at,” its mistress admitted. “The flowers and thatched roofs are so picturesque. ‘Quite a pastoral idyll,’ my guests tell me. The people one sees about seem contented and respectful, too.”

“They should be, madam,” Mr. Hurd answered drily. “The villagers have had a good many privileges from your family for generations.”

The lady inclined her head thoughtfully.

“You think, then,” she remarked, “that if anything should happen in England, like the French Revolution, I should not find unexpected thoughts and discontent smouldering amongst them? You believe that they are really contented?”

Mr. Hurd knew nothing about revolutions, and he was utterly unable to follow the trend of her thoughts.

“If they were not, madam,” he declared, “they would deserve to be in the workhouse—and I should feel it my duty to assist them in getting there.”

The lady of Thorpe laughed softly to herself.

“You, too, then, Mr. Hurd,” she said, “you are content with your life? You don’t mind my being personal, do you? It is such a change down here, such a different existence ... and I like to understand everything.”

Upon Mr. Hurd the almost pathetic significance of those last words was wholly wasted. They were words of a language which he could not comprehend. He realized only their direct application—and the woman to him seemed like a child.

“If I were not content, madam,” he said, “I should deserve to lose my place. I should deserve to lose it,” he added after a moment’s pause, “notwithstanding the fact that I have done my duty faithfully for four and forty years.”

She smiled upon him brilliantly. They were so far apart that she feared lest she might have offended him.

“I have always felt myself a very fortunate woman, Mr. Hurd,” she said, “in having possessed your services.”

He rose as though about to go. It was her whim, however, to detain him.

“You lost your wife some years ago, did you not, Mr. Hurd?” she began tentatively. As a matter of fact, she was not sure of her ground.

“Seven years back, madam,” he answered, with immovable face. “She was, unfortunately, never a strong woman.”

“And your son?” she asked more confidently. “Is he back from South Africa?”

“A year ago, madam,” he answered. “He is engaged at present in the estate office. He knows the work well——”

“The best place for him, of course,” she interrupted. “We ought to do all we can for our young men who went out to the war. I should like to see your son, Mr. Hurd. Will you tell him to come up some day?”

“Certainly, madam,” he answered.

“Perhaps he would like to shoot with my guests on Thursday?” she suggested graciously.

Mr. Hurd did not seem altogether pleased.

“It has never been the custom, madam,” he remarked, “for either my son or myself to be associated with the Thorpe shooting parties.”

“Some customs,” she remarked pleasantly, “are well changed, even in Thorpe. We shall expect him.”

Mr. Hurd’s mouth reminded her for a moment of a steel trap. She could see that he disapproved, but she had no intention of giving way. He began to tie up his papers, and she watched him with some continuance of that wave of interest which he had somehow contrived to excite in her. The signature of one of the letters which he was methodically folding, caught her attention.

“What a strange name!” she remarked. “Victor Macheson! Who is he?”

Mr. Hurd unfolded the letter. The ghost of a smile flickered upon his lips.

“A preacher, apparently,” he answered. “The letter is one asking permission to give a series of what he terms religious lectures in Harrison’s large barn!”

Her eyebrows were gently raised. Her tone was one of genuine surprise.

“What, in Thorpe?” she demanded.

“In Thorpe!” Mr. Hurd acquiesced.

She took the letter and read it. Her perplexity was in no manner diminished.

“The man seems in earnest,” she remarked. “He must either be a stranger to this part of the country, or an extremely impertinent person. I presume, Mr. Hurd, that nothing has been going on in the place with which I am unacquainted?”

“Certainly not, madam,” he answered.

“There has been no drunkenness?” she remarked. “The young people have, I presume, been conducting their love-making discreetly?”

The lines of Mr. Hurd’s mouth were a trifle severe. One could imagine that he found her modern directness of speech indelicate.

“There have been no scandals of any sort connected with the village, madam,” he assured her. “To the best of my belief, all of our people are industrious, sober and pious. They attend church regularly. As you know, we have not a public-house or a dissenting place of worship in the village.”

“The man must be a fool,” she said deliberately. “You did not, of course, give him permission to hold these services?”

“Certainly not,” the agent answered. “I refused it absolutely.”

The lady rose, and Mr. Hurd understood that he was dismissed.

“You will tell your son about Thursday?” she reminded him.

“I will deliver your message, madam,” he answered.

She nodded her farewell as the footman opened the door.

“Everything seems to be most satisfactory, Mr. Hurd,” she said. “I shall probably be here for several weeks, so come up again if there is anything you want me to sign.”

“I am much obliged, madam,” the agent answered.

He left the place by a side entrance, and rode slowly down the private road, fringed by a magnificent row of elm trees, to the village. The latch of the iron gate at the end of the avenue was stiff, and he failed to open it with his hunting crop at the first attempt. Just as he was preparing to try again, a tall, boyish-looking young man, dressed in sombre black, came swiftly across the road and opened the gate. Mr. Hurd thanked him curtly, and the young man raised his hat.

“You are Mr. Hurd, I believe?” he remarked. “I was going to call upon you this afternoon.”

The little man upon the pony frowned. He had no doubt as to his questioner.

“My name is Hurd, sir,” he answered stiffly. “What can I do for you?”

“You can let me have that barn for my services,” the other answered smiling. “I wrote you about it, you know. My name is Macheson.”

Mr. Hurd’s answer was briefly spoken, and did not invite argument.

“I have mentioned the matter to Miss Thorpe-Hatton, sir. She agrees with me that your proposed ministrations are altogether unneeded in this neighbourhood.”

“You won’t let me use the barn, then?” the young man remarked pleasantly, but with some air of disappointment.

Mr. Hurd gathered up the reins in his hand.

“Certainly not, sir!”

He would have moved on, but his questioner stood in the way. Mr. Hurd looked at him from underneath his shaggy eyebrows. The young man was remarkably young. His smooth, beardless face was the face of a boy. Only the eyes seemed somehow to speak of graver things. They were very bright indeed, and they did not falter.

“Mr. Hurd,” he begged, “do let me ask you one question! Why do you refuse me? What harm can I possibly do by talking to your villagers?”

Mr. Hurd pointed with his whip up and down the country lane.

“This is the village of Thorpe, sir,” he answered. “There are no poor, there is no public-house, and there, within a few hundred yards of the farthest cottage,” he added, pointing to the end of the street, “is the church. You are not needed here. That is the plain truth.”

The young man looked up and down, at the flower-embosomed cottages, with their thatched roofs and trim appearance, at the neatly cut hedges, the well-kept road, the many signs of prosperity. He looked at the little grey church standing in its ancient walled churchyard, where the road divided, a very delightful addition to the picturesque beauty of the place. He looked at all these things and he sighed.

“Mr. Hurd,” he said, “you are a man of experience. You know very well that material and spiritual welfare are sometimes things very far apart.”

Mr. Hurd frowned and turned his pony’s head towards home.

“I know nothing of the sort, sir,” he snapped. “What I do know is that we don’t want any Salvation Army tricks here. You should stay in the cities. They like that sort of thing there.”

“I must come where I am sent, Mr. Hurd,” the young man answered. “I cannot do your people any harm. I only want to deliver my message—and go.”

Mr. Hurd wheeled his pony round.

“I submitted your letter to Miss Thorpe-Hatton,” he said. “She agrees with me that your ministrations are wholly unnecessary here. I wish you good evening!”

The young man caught for a moment at the pony’s rein.

“One moment, sir,” he begged. “You do not object to my appealing to Miss Thorpe-Hatton herself?”

A grim, mirthless smile parted the agent’s lips.

“By no means!” he answered, as he cantered off.

Victor Macheson stood for a moment watching the retreating figure. Then he looked across the park to where, through the great elm avenues, he could catch a glimpse of the house. A humorous smile suddenly brightened his face.

“It’s got to be done!” he said to himself. “Here goes!”

The mistress of Thorpe stooped to pat a black Pomeranian which had rushed out to meet her. It was when she indulged in some such movement that one realized more thoroughly the wonderful grace of her slim, supple figure. She who hated all manner of exercise had the ease of carriage and flexibility of one whose life had been spent in athletic pursuits.

“How are you all?” she remarked languidly. “Shocking hostess, am I not?”

A fair-haired little woman turned away from the tea-table. She held a chocolate éclair in one hand, and a cup of Russian tea in the other. Her eyes were very dark, and her hair very yellow—and both were perfectly and unexpectedly natural. Her real name was Lady Margaret Penshore, but she was known to her intimates, and to the mysterious individuals who write under a nom-de-guerre in the society papers, as “Lady Peggy.”

“A little casual perhaps, my dear Wilhelmina,” she remarked. “Comes from your association with Royalty, I suppose. Try one of your own caviare sandwiches, if you want anything to eat. They’re ripping.”

Wilhelmina—she was one of the few women of her set with whose Christian name no one had ever attempted to take any liberties—approached the tea-table and studied its burden. There were a dozen different sorts of sandwiches arranged in the most tempting form, hot-water dishes with delicately browned tea-cakes simmering gently, thick cream in silver jugs, tea and coffee, and in the background old China dishes piled with freshly gathered strawberries and peaches and grapes, on which the bloom still rested. On a smaller table were flasks of liqueurs and a spirit decanter.

“Anyhow,” she remarked, pouring herself out some tea, “I do feed you people well. And as to being casual, I warned you that I never put in an appearance before five.”

A man in the background, long and lantern-faced, a man whose age it would have been as impossible to guess as his character, opened and closed his watch with a clink.

“Twenty minutes past,” he remarked. “To be exact, twenty-two minutes past.”

His hostess turned and regarded him contemplatively.

“How painfully precise!” she remarked. “Somehow, it doesn’t sound convincing, though. Your watch is probably like your morals.”

“What a flattering simile!” he murmured.

“Flattering?”

“It presupposes, at any rate, their existence,” he explained. “It is years since I was reminded of them.”

Wilhelmina seated herself before an open card-table.

“No doubt,” she answered. “You see I knew you when you were a boy. Seriously,” she continued, “I have been engaged with my agent for the last half-hour—a most interesting person, I can assure you. There was an agreement with one Philip Crooks concerning a farm, which he felt compelled to read to me—every word of it! Come along and cut, all of you!”

The fourth person, slim, fair-haired, the typical army officer and country house habitué, came over to the table, followed by the lantern-jawed man. Lady Peggy also turned up a card.

“You and I, Gilbert,” Wilhelmina remarked to the elder man. “Here’s luck to us! What on earth is that you are drinking?”

“Absinthe,” he answered calmly. “I have been trying to persuade Austin to join me, but it seems they don’t drink absinthe in the Army.”

“I should think not, indeed,” his hostess answered. “And you my partner, too! Put the stuff away.”

Gilbert Deyes raised his glass and looked thoughtfully into its opalescent depths.

“Ah! my dear lady,” he said, “you make a great mistake when you number absinthe amongst the ordinary intoxicating beverages. I tell you that the man who invented it was an epicure in sensations and—er—gastronomy. If only De Quincey had realized the possibility of absinthe, he would have given us jewelled prose indeed.”

Wilhelmina yawned.

“Bother De Quincey!” she declared. “It’s your bridge I’m thinking of.”

“Dear lady, you need have no anxiety,” Deyes answered reassuringly. “One does not trifle with one’s livelihood. You will find me capable of the most daring finesses, the most wonderful coups. I shall not revoke, I shall not lead out of the wrong hand. My declarations will be touched with genius. The rubber, in fact, is already won. Vive l’absinthe!”

“The rubber will never be begun if you go on talking nonsense much longer,” Lady Peggy declared, tapping the table impatiently. “I believe I hear the motors outside. We shall have the whole crowd here directly.”

“They won’t find their way here,” their hostess assured them calmly. “My deal, I believe.”

They played the hand in silence. At its conclusion, Wilhelmina leaned back in her chair and listened.

“You were right, Peggy,” she said, “they are all in the hall. I can hear your brother’s voice.”

Lady Peggy nodded.

“Sounds healthy, doesn’t it?”

Gilbert Deyes leaned across to the side table and helped himself to a cigarette.

“Healthy! I call it boisterous,” he declared. “Where have they all been?”

“Motoring somewhere,” Wilhelmina answered. “They none of them have any idea how to pass the time away until the first run.”

“Sport, my dear hostess,” Deyes remarked, “is the one thing which makes life in a country house almost unendurable.”

Wilhelmina shrugged her shoulders.

“That’s all very well, Gilbert,” she said, “but what should we do if we couldn’t get rid of some of these lunatics for at least part of the day?”

“Reasonable, I admit,” Deyes answered, “but think what an intolerable nuisance they make of themselves for the other part. I double No Trumps, Lady Peggy.”

Lady Peggy laid down her cards.

“For goodness’ sake, no more digressions,” she implored. “Remember, please, that I play this game for the peace of mind of my tradespeople! I redouble!”

The hand was played almost in silence. Lady Peggy lost the odd trick and began to add up the score with a gentle sigh.

“After all,” her partner remarked, returning to the subject which they had been discussing, “I don’t think that we could get on very well in this country without sport, of some sort.”

“Of course not,” Deyes answered. “We are all sportsmen, every one of us. We were born so. Only, while some of us are content to wreak our instinct for destruction upon birds and animals, others choose the nobler game—our fellow-creatures! To hunt or trap a human being is finer sport than to shoot a rocketing pheasant, or to come in from hunting with mud all over our clothes, smelling of ploughed fields, steaming in front of the fire, telling lies about our exploits—all undertaken in pursuit of a miserable little animal, which as often as not outwits us, and which, in an ordinary way, we wouldn’t touch with gloves on! What do you say, Lady Peggy?”

“You’re getting beyond me,” she declared. “It sounds a little savage.”

Deyes dealt the cards slowly, talking all the while.

“Sport is savage,” he declared. “No one can deny it. Whether the quarry be human or animal, the end is death. But of all its varieties, give me the hunting of man by man, the brain of the hunter coping with the wiles of the hunted, both human, both of the same order. The game’s even then, for at any moment they may change places—the hunter and his quarry. It’s finer work than slaughtering birds at the coverside. It gives your sex a chance, Lady Peggy.”

“It sounds exciting,” she admitted.

“It is,” he answered.

His hostess looked up at him languidly.

“You speak like one who knows!”

“Why not?” he murmured. “I have been both quarry and hunter. Most of us have more or less! I declare Hearts!”

Again there was an interval of silence, broken only by the stock phrases of the game, and the soft patter of the cards upon the table. Once more the hand was played out and the cards gathered up. Captain Austin delivered his quota to the general discussion.

“After all,” he said, “if it wasn’t for sport, our country houses would be useless.”

“Not at all!” Deyes declared. “Country houses should exist for——”

“For what, Mr. Deyes? Do tell us,” Lady Peggy implored.

“For bridge!” he declared. “For giving weary married people the opportunity for divorce, and as an asylum from one’s creditors.”

Wilhelmina shook her head as she gathered up her cards.

“You are not at your best to-day, Gilbert,” she said. “The allusion to creditors is prehistoric! No one has them nowadays. Society is such a hop-scotch affair that our coffers are never empty.”

“What a Utopian sentiment!” Lady Peggy murmured.

“We can’t agree, can we?” Deyes whispered in her ear.

“You! Why they say that you are worth a million,” she protested.

“If I am I remain poor, for I cannot spend it,” he declared.

“Why not?” his hostess asked him from across the table.

“Because,” he answered, “I am cursed with a single vice, trailing its way through a labyrinth of virtues. I am a miser!”

Lady Peggy laughed incredulously.

“Rubbish!” she exclaimed.

“Dear lady, it is nothing of the sort,” he answered, shaking his head sadly. “I have felt it growing upon me for years. Besides, it is hereditary. My mother opened a post-office savings bank account for me. At an early age I engineered a corner in marbles and sold out at a huge profit. I am like the starving dyspeptic at the rich man’s feast.”

Captain Austin intervened.

“I declare Diamonds,” he announced, and the hand proceeded.

Wilhelmina leaned back in her chair as the last trick fell. Her eyes were turned towards the window. She could just see the avenue of elms down which her agent had ridden a short while since. Deyes, through half closed eyes, watched her with some curiosity.

“If one dared offer a trifling coin of the realm——” he murmured.

“I was thinking of your theory,” she interrupted. “According to you, I suppose the whole world is made up of hunters and their quarry. Can you tell, I wonder, by looking at people, to which order they belong?”

“It is easy,” he answered. “Yet you must remember we are continually changing places. The man who cracks the whip to-day is the hunted beast to-morrow. The woman who mocks at her lover this afternoon is often the slave-bearer when dusk falls. Swift changes like this are like rain upon the earth. They keep us, at any rate, out of the asylums.”

Wilhelmina was still looking out of the window. Up the great avenue, in and out amongst the tree trunks, but moving always with swift buoyant footsteps towards the house, came a slim, dark figure, soberly dressed in ill-fitting clothes. He walked with the swing of early manhood, his head was thrown back, and he carried his hat in his hand. She leaned forward to watch him more closely—he seemed to have associated himself in some mysterious manner with the mocking words of Gilbert Deyes. Half maliciously, she drew his attention to the swiftly approaching figure.

“Come, my friend of theories,” she said mockingly. “There is a stranger there, the young man who walks so swiftly. To which of your two orders does he belong?”

Deyes looked out of the window—a brief, careless glance.

“To neither,” he answered. “His time has not come yet. But he has the makings of both.”

A footman entered the room a few minutes later, and obedient, without a doubt, to some previously given command, waited behind his mistress’ chair until a hand had been played. When it was over, she spoke to him without turning her head.

“What is it, Perkins?” she asked.

He bent forward respectfully.

“There is a young gentleman here, madam, who wishes to see you most particularly. He has no card, but he said that his name would not be known to you.”

“Tell him that I am engaged,” Wilhelmina said. “He must give you his name, and tell you what business he has come upon.”

“Very good, madam!” the man answered, and withdrew.

He was back again before the next hand had been played. Once more he stood waiting in respectful silence.

“Well?” his mistress asked.

“His name, madam, is Mr. Victor Macheson. He said that he would wait as long as you liked, but he preferred telling you his business himself.”

“I fancy that I know it,” Wilhelmina answered. “You can show him in here.”

“Is it the young man, I wonder,” Lady Peggy remarked, “who came up the avenue as though he were walking on air?”

“Doubtless,” Wilhelmina answered. “He is some sort of a missionary. I had him shown in here because I thought his coming at all an impertinence, and I want to make him understand it. You will probably find him amusing, Mr. Deyes.”

Gilbert Deyes shook his head quietly.

“There was a time,” he murmured, “when the very word missionary was a finger-post to the ridiculous. The comic papers rob us, however, of our elementary sources of humour.”

They all looked curiously towards the door as he entered, all except Wilhelmina, who was the last to turn her head, and found him hesitating in some embarrassment as to whom to address. He was somewhat above medium height, fair, with a mass of wind-tossed hair, and had the smooth face of a boy. His eyes were his most noticeable feature. They were very bright and very restless. Lady Peggy called them afterwards uncomfortable eyes, and the others, without any explanation, understood what she meant.

“I am Miss Thorpe-Hatton,” Wilhelmina said calmly. “I am told that you wished to see me.”

She turned only her head towards him. Her words were cold and unwelcoming. She saw that he was nervous and she had no pity. It was unworthy of her. She knew that. Her eyes questioned him calmly. Sitting there in her light muslin dress, with her deep-brown hair arranged in the Madonna-like fashion, which chanced to be the caprice of the moment, she herself—one of London’s most beautiful women—seemed little more than a girl.

“I beg your pardon,” he began hurriedly. “I understood—I expected——”

“Well?”

The monosyllable was like a drop of ice. A faint spot of colour burned in his cheeks. He understood now that for some reason this woman was inimical to him. The knowledge seemed to have a bracing effect. His eyes flashed with a sudden fire which gave force to his face.

“I expected,” he continued with more assurance, “to have found Miss Thorpe-Hatton an older lady.”

She said nothing. Only her eyebrows were very slightly raised. She seemed to be asking him silently what possible concern the age of the lady of Thorpe-Hatton could be to him. He was to understand that his remark was almost an impertinence.

“I wished,” he said, “to hold a service in Thorpe on Sunday afternoon, and also one during the week, and I wrote to your agent asking for the loan of a barn, which is generally, I believe, used for any gathering of the villagers. Mr. Hurd found himself unable to grant my request. I have ventured to appeal to you.”

“Mr. Hurd,” she said calmly, “decided, in my opinion, quite rightly. I do not see what possible need my villagers can have of further religious services than the Church affords them.”

“Madam,” he answered, “I have not a word to say against your parish church, or against your excellent vicar. Yet I believe, and the body to which I am attached believes, that change is stimulating. We believe that the great truths of life cannot be presented to our fellow-creatures too often, or in too many different ways.”

“And what,” she asked, with a faint curl of her beautiful lips, “do you consider the great truths of life?”

“Madam,” he answered, with slightly reddening cheeks, “they vary for every one of us, according to our capacity and our circumstances. What they may mean,” he added, after a moment’s hesitation, “to people of your social order, I do not know. It has not come within the orbit of my experience. It was your villagers to whom I was proposing to talk.”

There was a moment’s silence. Gilbert Deyes and Lady Peggy exchanged swift glances of amused understanding. Wilhelmina bit her lip, but she betrayed no other sign of annoyance.

“To what religious body do you belong?” she asked.

“My friends,” he answered, “and I, are attached to none of the recognized denominations. Our only object is to try to keep alight in our fellow-creatures the flame of spirituality. We want to help them—not to forget.”

“There is no name by which you call yourselves?” she asked.

“None,” he answered.

“And your headquarters are where?” she asked.

“In Gloucestershire,” he answered—“so far as we can be said to have any headquarters at all.”

“You have no churches then?” she asked.

“Any building,” he answered, “where the people are to whom we desire to speak, is our church. We look upon ourselves as missioners only.”

“I am afraid,” Wilhelmina said quietly, “that I am only wasting your time in asking these questions. Still, I should like to know what induced you to choose my village as an appropriate sphere for your labours.”

“We each took a county,” he answered. “Leicestershire fell to my lot. I selected Thorpe to begin with, because I have heard it spoken of as a model village.”

Wilhelmina’s forehead was gently wrinkled.

“I am afraid,” she said, “that I am a somewhat dense person. Your reason seems to me scarcely an adequate one.”

“Our belief is,” he declared, “that where material prosperity is assured, especially amongst this class of people, the instincts towards spirituality are weakened.”

“My people all attend church; we have no public-house; there are never any scandals,” she said.

“All these things,” he admitted, “are excellent. But they do not help you to see into the lives of these people. Church-going may become a habit, a respectable and praiseworthy thing—and a thing expected of them. Morality, too, may become a custom—until temptation comes. One must ask oneself what is the force which prompts these people to direct their lives in so praiseworthy a manner.”

“You forget,” she remarked, “that these are simple folk. Their religion with them is simply a matter of right or wrong. They need no further instruction in this.”

“Madam,” he said, “so long as they are living here, that may be so. Frankly, I do not consider it sufficient that their lives are seemly, so long as they live in the shadow of your patronage. What happens to those who pass outside its influence is another matter.”

“What do you know about that?” she asked coldly.

“What I do know about it,” he answered, “decided me to come to Thorpe.”

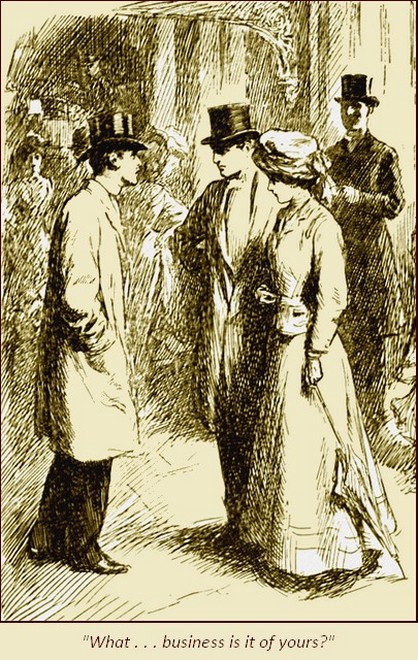

There was a moment’s silence. Any of the other three, Gilbert Deyes especially, perhaps, would have found it hard to explain, even to realize the interest with which they listened to the conversation between these two—the somewhat unkempt, ill-attired boy, with the nervous, forceful manner and burning eyes, and the woman, so sure of herself, so coldly and yet brutally ungracious. It was not so much the words themselves that passed between them that attracted as the undernote of hostility, more felt than apparent—the beginning of a duel, to all appearance so ludicrously onesided, yet destined to endure. Deyes turned in his chair uneasily. He was watching this intruder—a being outwardly so far removed from their world. The niceties of a correct toilet had certainly never troubled him, his clothes were rough in material and cut, he wore a flannel shirt, and a collar so low that his neck seemed ill-shaped. He had no special gifts of features or figure, his manner was nervous, his speech none too ready. Deyes found himself engaged in a swift analysis of the subtleties of personality. What did this young man possess that he should convey so strong a sense of power? There was something about him which told. They were all conscious of it, and, more than any of them, the woman who was regarding him with such studied ill-favour. To the others, her still beautiful face betrayed only some languid irritation. Deyes fancied that he saw more there—that underneath the mask which she knew so well how to wear there were traces of some deeper disturbance.

“Do you mind explaining yourself?” she asked. “That sounds rather an extraordinary statement of yours.”

“A few months ago,” he said, “I attended regularly one of the police courts in London. Day by day I came into contact with the lost souls who have drifted on to the great rubbish-heap. There was a girl, Martha Gullimore her name was, whose record for her age was as black as sin could make it. Her father, I believe, is the blacksmith in your model village! I spoke to him of his daughter yesterday, and he cursed me!”

“You mean Samuel Gullimore—my farrier?” she asked.

“That is the man,” he answered.

“Have you any other—instances?” she asked.

“More than one, I am sorry to say,” he replied. “There were two young men who left here only a year ago—one is the son of your gardener, the other was brought up by his uncle at your lodge gates. I was instrumental in saving them from prison a few months ago. One we have shipped to Canada—the other, I am sorry to say, has relapsed. We did what we could, but beyond a certain point we cannot go.”

She leaned her head for a moment upon the slim, white fingers of her right hand, innocent of rings save for one great emerald, whose gleam of colour was almost barbaric in its momentary splendour. Her face had hardened a little, her tone was almost an offence.

“You would have me believe, then,” she said, “that my peaceful village is a veritable den of iniquity?”

“Not I,” he answered brusquely. “Only I would have you realize that roses and honeysuckle and regular wages, the appurtenances of material prosperity, are after all things of little consequence. They hear the song of the world, these people, in their leisure moments; their young men and girls are no stronger than their fellows when temptation comes.”

Deyes leaned suddenly forward in his chair. He felt that his intervention dissipated a dramatic interest, of which he was keenly conscious, but he could not keep silence any longer.

“To follow out your argument, sir, to its logical conclusion,” he said, “why not aim higher still? It is your contention, is it not, that the seeds of evil things are sown in indifference, that prosperity might even tend towards their propagation. Why not direct your energies, then, towards the men and women of Society? There is plenty of scope here for your labours.”

The young man turned towards him. The lines of his mouth had relaxed into a smile of tolerant indifference.

“I have no sympathy, sir,” he answered, “with the class you name. On a sinking ship, the cry is always, ‘Save the women and children.’ It is the less fortunate in the world’s possessions who represent the women and children of shipwrecked morality. It is for their betterment that we work.”

Deyes sighed gently.

“It is a pity,” he declared. “I am convinced that there is a magnificent opening for mission work amongst the idle classes.”

“No doubt,” the young man agreed quickly. “The question is whether the game is worth the candle.”

Deyes made no reply. Lady Peggy was laughing softly to herself.

“I have heard all that you have to say, Mr. Macheson,” the mistress of Thorpe said calmly, “and I can only repeat that I think your presence here as a missioner most unnecessary. I consider it, in fact, an——”

She hesitated. With a sudden flash of humour in his deep-set eyes, he supplied the word.

“An impertinence, perhaps!”

“The word is not mine,” she answered, “but I accept it willingly. I cannot interfere with Mr. Hurd’s decision as to the barn.”

“I am sorry,” he said slowly. “I must hold my meetings out of doors! That is all!”

There was a dangerous glitter in her beautiful eyes.

“There is no common land in the neighbourhood,” she said, “and you will of course understand that I will consider you a trespasser at any time you are found upon my property.”

He bowed slightly.

“I am here to speak to your people,” he said, “and I will do so, if I have to stop in these lanes and talk to them one by one. You will pardon my reminding you, madam, that the days of feudalism are over.”

Wilhelmina carefully shuffled the pack of cards which she had just taken up.

“We will finish our rubber, Peggy,” she said. “Mr. Deyes, perhaps I may trouble you to ring the bell!”

The young man was across the room before Deyes could move.

“You will allow me,” he said, with a delightfully humourous smile, “to facilitate my own dismissal. I shall doubtless meet your man in the hall. May I be allowed to wish you all good afternoon!”

They all returned his farewell save Wilhelmina, who had begun to deal. She seemed determined to remember his existence no more. Yet on the threshold, with the handle of the door between his fingers, he turned back. He said nothing, but his eyes were fixed upon her. Deyes leaned forward in his chair, immensely curious. Softly the cards fell into their places, there was no sign in her face of any consciousness of his presence. Deyes alone knew that she was fighting. He heard her breath come quicker, saw the fingers which gathered up her cards shake. Slowly, but with obvious unwillingness, she turned her head. She looked straight into the eyes of the man who still lingered.

“Good afternoon, Miss Thorpe-Hatton,” he said pleasantly. “I am sorry to have troubled you.”

Her lips moved, but she said nothing. She half inclined her head. The door was softly closed.

Never was a young man more pleased with himself than Stephen Hurd, on the night he dined at Thorpe-Hatton. He had shot well all day, and been accepted with the utmost cordiality by the rest of the party. At dinner time, his hostess had placed him on her left hand, and though it was true she had not much to say to him, it was equally obvious that her duties were sufficient to account for her divided attention. He was quite willing to be ignored by the lady on his other side—a little elderly, and noted throughout the country for her husband-hunting proclivities. He recognized the fact that, apart from the personal side of the question, he could scarcely hope to be of any interest to her. The novelty of the situation, Wilhelmina’s occasional remarks, and a dinner such as he had never tasted before were sufficient to keep him interested. For the rest he was content to twirl his moustache, of which he was inordinately proud, and lean back in his chair with the comfortable reflection that he was the first of his family to be offered the complete hospitality of Thorpe-Hatton.

Towards the close of dinner, his hostess leaned towards him.

“Have you seen or heard anything of a young man named Macheson in the village?” she asked.

“I have seen him once or twice,” he answered. “Here on a missionary expedition or something of the sort, I believe.”

“Has he made any attempt to hold a meeting?” she asked.

“Not that I have heard of,” he replied. “He has been talking to some of the people, though. I saw him with old Gullimore yesterday.”

“That reminds me,” she remarked, “is it true that Gullimore has had trouble with his daughter?”

“I believe so,” young Hurd admitted, looking downwards at his plate.

“The man was to blame for letting her leave the place,” Wilhelmina declared, in cold, measured tones. “A pretty girl, I remember, but very vain, and a fool, of course. But about this young fellow Macheson. Do you know who he is, and where he came from?”

Stephen Hurd shook his head.

“I’m afraid I don’t,” he said doubtfully. “He belongs to some sort of brotherhood, I believe. I can’t exactly make out what he’s at. Seems a queer sort of place for him to come missioning, this!”

“So I told him,” she said. “By the bye, do you know where he is staying?”

“At Onetree farm,” the young man answered.

Wilhelmina frowned.

“Will you execute a commission for me to-morrow?” she asked.

“With pleasure!” he answered eagerly.

“You will go to the woman at Onetree farm, I forget her name, and say that I desire to take her rooms myself from to-morrow, or as soon as possible. I will pay her for them, but I do not wish that young man to be taken in by any of my tenants. You will perhaps make that known.”

“I will do so,” he declared. “I hope he will have the good sense to leave the neighbourhood.”

“I trust so,” Wilhelmina replied.

She turned away to speak once more to the man on her other side, and did not address Stephen Hurd again. He watched her covertly, with tingling pulses, as she devoted herself to her neighbour—the Lord-Lieutenant of the county. He considered himself a judge of the sex, but he had had few opportunities even of admiring such women as the mistress of Thorpe. He watched the curve of her white neck with its delicate, satin-like skin, the play of her features, the poise of her somewhat small, oval head. He admired the slightly wearied air with which she performed her duties and accepted the compliments of her neighbour. “A woman of mysteries” some one had once called her, and he realized that it was the mouth and the dark, tired eyes which puzzled those who attempted to classify her. What a triumph—to bring her down to the world of ordinary women, to drive the weariness away, to feel the soft touch, perhaps, of those wonderful arms! He was a young man of many conquests, and with a sufficiently good idea of himself. The thought was like wine in his blood. If only it were possible!

He relapsed into a day-dream, from which he was aroused only by the soft flutter of gowns and laces as the women rose to go. There was a momentary disarrangement of seats. Gilbert Deyes, who was on the other side of the table, rose, and carrying his glass in his hand, came deliberately round to the vacant seat by the young man’s side. In his evening clothes, the length and gauntness of his face and figure seemed more noticeable than ever. His skin was dry, almost like parchment, and his eyes by contrast appeared unnaturally bright. His new neighbour noticed, too, that the glass which he carried so carefully contained nothing but water.

“I will come and talk to you for a few minutes, if I may,” Deyes said. “I leave the Church and agriculture to hobnob. Somehow I don’t fancy that as a buffer I should be a success.”

Young Hurd smiled amiably. He was more than a little flattered.

“The Archdeacon,” he remarked, “is not an inspiring neighbour.”

Deyes lit one of his own cigarettes and passed his case.

“I have found the Archdeacon very dull,” he admitted—“a privilege of his order, I suppose. By the bye, you are having a dose of religion from a new source hereabouts, are you not?”

“You mean this young missioner?” Hurd inquired doubtfully.

Deyes nodded.

“I was with our hostess when he came up to ask for the loan of a barn to hold services in. A very queer sort of person, I should think?”

“I haven’t spoken to him,” Hurd answered, “but I should think he’s more or less mad. I can understand mission and Salvation Army work and all that sort of thing in the cities, but I’m hanged if I can understand any one coming to Thorpe with such notions.”

“Our hostess is annoyed about it, I imagine,” Deyes remarked.

“She seems to have taken a dislike to the fellow,” Hurd admitted. “She was speaking to me about him just now. He is to be turned out of his lodgings here.”

Gilbert Deyes smiled. The news interested him.

“Our hostess is practical in her dislikes,” he remarked.

“Why not?” his neighbour answered. “The place belongs to her.”

Deyes watched for a moment the smoke from his cigarette, curling upwards.

“The young man,” he said thoughtfully, “impressed me as being a person of some determination. I wonder whether he will consent to accept defeat so easily.”

The agent’s son scarcely saw what else there was for him to do.

“There isn’t anywhere round here,” he remarked, “where they would take him in against Miss Thorpe-Hatton’s wishes. Besides, he has nowhere to preach. His coming here at all was a huge mistake. If he’s a sensible person he’ll admit it.”

Deyes nodded as he rose to his feet and lounged towards the door with the other men.

“Play bridge?” he asked his companion, as they crossed the hall.

“A little,” the young man answered, “for moderate stakes.”

They entered the drawing-room, and Deyes made his way to a secluded corner, where Lady Peggy sat scribbling alone in a note-book.

“My dear Lady Peggy,” he inquired, “whence this exceptional industry?”

She closed the book and looked up at him with twinkling eyes.

“Well, I didn’t mean to tell a soul until it was finished,” she declared, “but you’ve just caught me. I’ve had such a brilliant idea. I’m going to write a Society Encyclopædia!”

Deyes looked at her solemnly.

“A Society Encyclopædia!” he repeated uncertainly. “’Pon my word, I’m not quite sure that I understand.”

She motioned him to sit down by her side.

“I’ll explain,” she said. “You know we’re all expected to know something about everything nowadays, and it’s such a bore reading up things. I’m going to compile a little volume of definitions. I shall sell it at a guinea a copy, pay all my debts, and become quite respectable again.”

Deyes shook his head. His attitude was scarcely sympathetic.

“My dear Lady Peggy, what nonsense!” he declared. “Respectable, indeed! I call it positively pandering to the middle classes!”

Lady Peggy looked doubtful.

“It is a horrid word, isn’t it?” she admitted, “but it would be lovely to make some money. Of course, I haven’t absolutely decided how to spend it yet. It does seem rather a waste, doesn’t it, to pay one’s debts, but think of the luxury of feeling one could do it if one wanted to!”

“There’s something in that,” Deyes admitted. “But an encyclopædia! My dear Lady Peggy, you don’t know what you’re talking about. I’ve got one somewhere, I know. It came in a van, and it took two of the men to unload it.”

Lady Peggy laughed softly.

“Oh! I don’t mean that sort, of course,” she declared. “I mean just a little gilt-edged text book, bound in morocco, you know, with just those things in it we’re likely to run up against. Radium, for instance. Now every one’s talking about radium. Do you know what radium is?”

Deyes swung his eyeglass carefully by its black riband.

“Well,” he admitted, “I’ve a sort of idea, but I’m not very good at definitions.”

“Of course not,” Lady Peggy declared triumphantly. “When it comes to the point, you see what a good idea mine is. You turn to my textbook,” she added, turning the pages over rapidly, “and there you are. Radium! ’A hard, rare substance, invented by Mr. Gillette to give tone to his bachelor parties.’ What do you think of that?”

“Wonderful!” Deyes declared solemnly. “Where do you get your information from?”

“Oh! I poke about in dictionaries and things, and ask every one questions,” Lady Peggy declared airily. “Would you like to hear some more?”

“Our hostess is beckoning to me,” Deyes answered, rising. “I expect she wants some bridge.”

“I’m on,” Lady Peggy declared cheerfully. “Whom shall we get for a fourth?”

“Wilhelmina has found him already,” Deyes declared. “It’s the new young man, I think.”

Lady Peggy shrugged her shoulders.

“The agent’s son?” she remarked. “I shouldn’t have thought that he would have cared about our points.”

“He can afford it for once in a way, I should imagine,” Deyes answered. “I can’t understand, though——”

He stopped short. She looked at him curiously.

“Is it possible,” she murmured, “that there exists anything which Gilbert Deyes does not understand?”

“Many things,” he answered; “amongst them, why does Wilhelmina patronize this young man? He is well enough, of course, but——” he shrugged his shoulders expressively; “the thing needs an explanation, doesn’t it?”

“If Wilhelmina—were not Wilhelmina, it certainly would,” Lady Peggy answered. “I call her craving for new things and new people positively morbid. All the time she beats her wings against the bars. There are no new things. There are no new experiences. The sooner one makes up one’s mind to it the better.”

Gilbert Deyes laughed softly.

“If my memory serves me,” he said, “you are repeating a cry many thousand years old. Wasn’t there a prophet——”

“There was,” she interrupted, “but they are beckoning us. I hope I don’t cut with the young man. I don’t believe he has a bridge face.”

Victor Macheson smoked his after-breakfast pipe with the lazy enjoyment of one who is thoroughly at peace with himself and his surroundings. The tiny strip of lawn on to which he had dragged his chair was surrounded with straggling bushes of cottage flowers, and flanked by a hedge thick with honeysuckle. Straight to heaven, as the flight of a bird, the thin line of blue smoke curled upwards to the summer sky; the very air seemed full of sweet scents and soothing sounds. A few yards away, a procession of lazy cows moved leisurely along the grass-bordered lane; from the other side of the hedge came the cheerful sound of a reaping-machine, driven slowly through the field of golden corn.

The man, through half closed eyes, looked out upon these things, and every line in his face spelt contentment. In repose, the artistic temperament with which he was deeply imbued, asserted itself more clearly—the almost fanatical light in his eyes was softened; one saw there was something of the wistfulness of those who seek to raise but a corner of the veil that hangs before the world of hidden things—something, too, of the subdued joy which even the effort brings. The lines of his forceful mouth were less firm, more sensitive—a greater sense of humanity seemed somehow to have descended upon him as he lounged there in the warmth of the sun, with the full joy of his beautiful environment creeping through his blood.

“If you please, Mr. Macheson,” some one said in his ear.

He turned his head at once. A tall, fair girl had stepped out of the room where he had been breakfasting, and was standing by his elbow. She was neatly dressed, pretty in a somewhat insipid fashion, and her hands and hair showed signs of a refinement superior to her station. Just now she was apparently nervous. Macheson smiled at her encouragingly.

“Well, Letty,” he said, “what is it?”

“I wanted—can I say something to you, Mr. Macheson?” she began.

“Why not?” he answered kindly. “Is it anything very serious? Out with it!”

“I was thinking, Mr. Macheson,” she said, “that I should like to leave home—if I could—if there was anything which I could do. I wanted to ask your advice.”

He laid down his pipe and looked at her seriously.

“Why, Letty,” he said, “how long have you been thinking of this?”

“Oh! ever so long, sir,” she exclaimed, speaking with more confidence. “You see there’s nothing for me to do here except when there’s any one staying, like you, sir, and that’s not often. Mother won’t let me help with the rough work, and Ruth’s growing up now, she’s ever such a strong girl. And I should like to go away if I could, and learn to be a little more—more ladylike,” she added, with reddening cheeks.

Macheson was puzzled. The girl was not looking him in the face. He felt there was something at the back of it all.

“My dear girl,” he said, “you can’t learn to be ladylike. That’s one of the things that’s born with you or it isn’t. You can be just as much a lady helping your mother here as practising grimaces in a London drawing-room.”

“But I want to improve myself,” she persisted.

“Go for a long walk every day, and look about you,” he said. “Read. I’ll lend you some books—the right sort. You’ll do better here than away.”

She was frankly dissatisfied.

“But I want to go away,” she declared. “I want to leave Thorpe for a time. I should like to go to London. Couldn’t I get a situation as lady’s help or companion or something of that sort? I shouldn’t want any money.”

He was silent for a moment.

“Does your mother know of this, Letty?” he asked.

“She wouldn’t object,” the girl answered eagerly. “She lets me do what I like.”

“Hadn’t you better tell me—the rest?” Macheson asked quietly.

The girl looked away uneasily.

“There is no rest,” she protested weakly.

Macheson shook his head.

“Letty,” he said, “if you have formed any ideas of a definite future for yourself, different from any you see before you here, tell me what they are, and I will do my best to help you. But if you simply want to go away because you are dissatisfied with the life here, because you fancy yourself superior to it, well, I’m sorry, but I’d sooner prevent your going than help you.”

Her eyes filled with tears.

“Oh! Mr. Macheson, it isn’t that,” she declared, “I—I don’t want to tell any one, but I’m very—very fond of some one who’s—quite different. I think he’s fond of me, too,” she added softly, “but he’s always used to being with ladies, and I wanted to improve myself so much! I thought if I went to London,” she added wistfully, “I might learn?”

Macheson laughed cheerfully. He laid his hand for a moment upon her arm.

“Oh! Letty, Letty,” he declared, “you’re a foolish little girl! Now, listen to me. If he’s a good sort, and I’m sure he is, or you wouldn’t be fond of him, he’ll like you just exactly as you are. Do you know what it means to be a lady, the supreme test of good manners? It means to be natural. Take my advice! Go on helping your mother, enter into the village life, make friends with the other girls, don’t imagine yourself a bit superior to anybody else. Read when you have time—I’ll manage the books for you, and spend all the time you can out of doors. It’s sound advice, Letty. Take my word for it. Hullo, who’s this?”

A new sound in the lane made them both turn their heads. Young Hurd had just ridden up and was fastening his pony to the fence. He looked across at them curiously, and Letty retreated precipitately into the house. A moment or two later he came up the narrow path, frowning at Macheson over the low hedge of foxgloves and cottage roses, and barely returning his courteous greeting. For a moment he hesitated, however, as though about to speak. Then, changing his mind, he passed on and entered the farmhouse.

He met Mrs. Foulton herself in the passage, and she welcomed him with a smiling face.

“Good morning, Mr. Hurd, sir!” she exclaimed, plucking at her apron. “Won’t you come inside, sir, and sit down? The parlour’s let to Mr. Macheson there, but he’s out in the garden, and he won’t mind your stepping in for a moment. And how’s your father, Mr. Hurd? Wonderful well he was looking when I saw him last.”

The young man followed her inside, but declined a chair.

“Oh! the governor’s all right, Mrs. Foulton,” he answered. “Never knew him anything else. Good weather for the harvest, eh?”

“Beautiful, sir!” Mrs. Foulton answered.

“Were you wanting to speak to John, Mr. Stephen? He’s about the home meadow somewhere, or in the orchard. I can send a boy for him, or perhaps you’d step out.”

“It’s you I came to see, Mrs. Foulton,” the young man said, “and ’pon my word, I don’t like my errand much.”

Mrs. Foulton was visibly anxious.

“There’s no trouble like, I hope, sir?” she began.

“Oh! it’s nothing serious,” he declared reassuringly. “To tell you the truth, it’s about your lodger.”

“About Mr. Macheson, sir!” the woman exclaimed.

“Yes! Do you know how long he was proposing to stay with you?”

“He’s just took the rooms for another week, sir,” she answered, “and a nicer lodger, or one more quiet and regular in his habits, I never had or wish to have. There’s nothing against him, sir—surely?”

“Nothing personal—that I know of,” Hurd answered, tapping his boots with his riding-whip. “The fact of it is, he has offended Miss Thorpe-Hatton, and she wants him out of the place.”

“Well, I never did!” Mrs. Foulton exclaimed in amazement. “Him offend Miss Thorpe-Hatton! So nice-spoken he is, too. I’m sure I can’t imagine his saying a wry word to anybody.”

“He has come to Thorpe,” Hurd explained, “on an errand of which Miss Thorpe-Hatton disapproves, and she does not wish to have him in the place. She knows that he is staying here, and she wishes you to send him away at once.”

Mrs. Foulton’s face fell.

“Well, I’m fair sorry to hear this, sir,” she declared. “It’s only this morning that he spoke for the rooms for another week, and I was glad and willing enough to let them to him. Well I never did! It does sound all anyhow, don’t it, sir, to be telling him to pack up and go sudden-like!”

“I will speak to him myself, if you like, Mrs. Foulton,” Stephen said. “Of course, Miss Thorpe-Hatton does not wish you to lose anything, and I am to pay you the rent of the rooms for the time he engaged them. I will do so at once, if you will let me know how much it is.”

He thrust his hand into his pocket, but Mrs. Foulton drew back. The corners of her mouth were drawn tightly together.

“Thank you, Mr. Stephen,” she said, “I’ll obey Miss Thorpe-Hatton’s wishes, of course, as in duty bound, but I’ll not take any money for the rooms. Thank you all the same.”

“Don’t be foolish, Mrs. Foulton,” the young man said pleasantly. “It will annoy Miss Thorpe-Hatton if she knows you have refused, and you may just as well have the money. Let me see. Shall we say a couple of sovereigns for the week?”

Mrs. Foulton shook her head.

“I’ll not take anything, sir, thank you all the same, and if you’d say a word to Mr. Macheson, I’d be much obliged. I’d rather any one spoke to him than me.”

Stephen Hurd pocketed the money with a shrug of the shoulders.

“Just as you like, of course, Mrs. Foulton,” he said. “I’ll go out and speak to the young gentleman at once.”

He strolled out and looked over the hedge.

“Mr. Macheson, I believe?” he remarked interrogatively.

Macheson nodded as he rose from his chair.

“And you are Mr. Hurd’s son, are you not?” he said pleasantly. “Wonderful morning, isn’t it?”

Young Hurd stepped over the rose bushes. The two men stood side by side, something of a height, only that the better cut of Hurd’s clothes showed his figure to greater advantage.

“I’m sorry to say that I’ve come on rather a disagreeable errand,” the agent’s son began. “I’ve been talking to Mrs. Foulton about it.”

“Indeed?” Macheson remarked interrogatively.

“The fact is you seem to have rubbed up against our great lady here,” young Hurd continued. “She’s very down on these services you were going to hold, and she wants to see you out of the place.”

“I am sorry to hear this,” Macheson said—and once more waited.

“It isn’t a pleasant task,” Stephen continued, liking his errand less as he proceeded; “but I’ve had to tell Mrs. Foulton that—that, in short, Miss Thorpe-Hatton does not wish her tenants to accept you as a lodger.”

“Miss Thorpe-Hatton makes war on a wide scale,” Macheson remarked, smiling faintly.

“Well, after all, you see,” Hurd explained, “the whole place belongs to her, and there is no particular reason, is there, why she should tolerate any one in it of whom she disapproves?”

“None whatever,” Macheson assented gravely.

“I promised Mrs. Foulton I would speak to you,” Stephen continued, stepping backwards. “I’m sure, for her sake, you won’t make any trouble. Good morning!”

Macheson bowed slightly.

“Good morning!” he answered.

Stephen Hurd lingered even then upon the garden path. Somehow he was not satisfied with his interview—with his own position at the end of it. He had an uncomfortable sense of belittlement, of having played a small part in a not altogether worthy game. The indifference of the other’s manner nettled him. He tried a parting shaft.

“Mrs. Foulton said something about your having engaged the rooms for another week,” he said, turning back. “Of course, if you insist upon staying, it will place the woman in a very awkward position.”

Macheson had resumed his seat.

“I should not dream,” he said coolly, “of resisting—your mistress’ decree! I shall leave here in half an hour.”

Young Hurd walked angrily down the path and slammed the gate. The sense of having been worsted was strong upon him. He recognized his own limitations too accurately not to be aware that he had been in conflict with a stronger personality.

“D—— the fellow!” he muttered, as he cantered down the lane. “I wish he were out of the place.”

A genuine wish, and one which betrayed at least a glimmering of a prophetic instinct. In some dim way he seemed to understand, even before the first move on the board, that the coming of Victor Macheson to Thorpe was inimical to himself. He was conscious of his weakness, of a marked inferiority, and the consciousness was galling. The fellow had no right to be a gentleman, he told himself angrily—a gentleman and a missioner!

Macheson re-lit his pipe and called to Mrs. Foulton.

“Mrs. Foulton,” he said pleasantly, “I’ll have to go! Your great lady doesn’t like me on the estate. I dare say she’s right.”

“I’m sure I’m very sorry, sir,” Mrs. Foulton declared shamefacedly. “You’ve seen young Mr. Hurd?”

“He was kind enough to explain the situation to me,” Macheson answered. “I’m afraid I am rather a nuisance to everybody. If I am, it’s because they don’t quite understand!”

“I’m sure, sir,” Mrs. Foulton affirmed, “a nicer lodger no one ever had. And as for them services, and the Vicar objecting to them, I can’t see what harm they’d do! We’re none of us so good but we might be a bit better!”

“A very sound remark, Mrs. Foulton,” Macheson said, smiling. “And now you must make out my bill, please, and what about a few sandwiches? You could manage that? I’m going to play in a cricket match this afternoon.”

“Why you’ve just paid the bill, sir! There’s only breakfast, and the sandwiches you’re welcome to, and very sorry I am to part with you, sir.”

“Better luck another time, I hope, Mrs. Foulton,” he answered, smiling. “I must go upstairs and pack my bag. I shan’t forget your garden with its delicious flowers.”

“It’s a shame as you’ve got to leave it, sir,” Mrs. Foulton said heartily. “If my Richard were alive he’d never have let you go for all the Miss Thorpe-Hattons in the world. But John—he’s little more than a lad—he’d be frightened to death for fear of losing the farm, if I so much as said a word to him.”

Macheson laughed softly.

“John’s a good son,” he said. “Don’t you worry him.”

He went up to his tiny bedroom and changed his clothes for a suit of flannels. Then he packed his few belongings and walked out into the world. He lit a pipe and shouldered his portmanteau.

“There is a flavour of martyrdom about this affair,” he said to himself, as he strolled along, “which appeals to me. I don’t think that young man has any sense of humour.”

He paused every now and then to listen to the birds and admire the view. He had the air of one thoroughly enjoying his walk. Presently he turned off the main road, and wandered along a steep green lane, which was little more than a cart-track. Here he met no one. The country on either side was common land, sown with rocks and the poorest soil, picturesque, but almost impossible of cultivation. A few sheep were grazing upon the hills, but other sign of life there was none. Not a farmhouse—scarcely a keeper’s cottage in sight! It was a forgotten corner of a not unpopulous county—the farthest portion of a belt of primeval forest land, older than history itself. Macheson laughed softly as he reached the spot he had had in his mind, and threw his bag over the grey stone wall into the cool shade of a dense fragment of wood.

“So much,” he murmured softly, “for the lady of Thorpe!”

“The instinct for games,” Wilhelmina remarked, “is one which I never possessed. Let us see whether we can learn something.”

In obedience to her gesture, the horses were checked, and the footman clambered down and stood at their heads. Deyes, from his somewhat uncomfortable back seat in the victoria, leaned forward, and, adjusting his eyeglass, studied the scene with interest.

“Here,” he remarked, “we have the ‘flannelled fool’ upon his native heath. They are playing a game which my memory tells me is cricket. Everyone seems very hot and very excited.”

Wilhelmina beckoned to the footman to come round to the side of the carriage.

“James,” she said, “do you know what all this means?”

She waved her hand towards the cricket pitch, the umpires with their white coats, the tent and the crowd of spectators. The man touched his hat.

“It is a cricket match, madam,” he answered, “between Thorpe and Nesborough.”

Wilhelmina looked once more towards the field, and recognized Mr. Hurd upon his stout little cob.

“Go and tell Mr. Hurd to come and speak to me,” she ordered.

The man hastened off. Mr. Hurd had not once turned his head. His eyes were riveted upon the game. The groom found it necessary to touch him on the arm before he could attract his attention. Even when he had delivered his message, the agent waited until the finish of the over before he moved. Then he cantered his pony up to the waiting carriage. Wilhelmina greeted him graciously.

“I want to know about the cricket match, Mr. Hurd,” she asked, smiling.

Mr. Hurd wheeled his pony round so that he could still watch the game.

“I am afraid that we are going to be beaten, madam,” he said dolefully. “Nesborough made a hundred and ninety-eight, and we have six wickets down for fifty.”

Wilhelmina seemed scarcely to realize the tragedy which his words unfolded.

“I suppose they are the stronger team, aren’t they?” she remarked. “They ought to be. Nesborough is quite a large town.”

“We have beaten them regularly until the last two years,” Mr. Hurd answered. “We should beat them now but for their fast bowler, Mills. I don’t know how it is, but our men will not stand up to him.”

“Perhaps they are afraid of being hurt,” Wilhelmina suggested innocently. “If that is he bowling now, I’m sure I don’t wonder at it.”

Mr. Hurd frowned.

“We don’t have men in the eleven who are afraid of getting hurt,” he remarked stiffly.

A shout of dismay from the onlookers, a smothered exclamation from Mr. Hurd, and a man was seen on his way to the pavilion. His wickets were spreadeagled, and the ball was being tossed about the field.

“Another wicket!” the agent exclaimed testily. “Crooks played all round that ball!”

“Isn’t that your son going in, Mr. Hurd?” Wilhelmina asked.

“Yes! Stephen is in now,” his father answered. “If he gets out, the match is over.”

“Who is the other batsman?” Deyes asked.

“Antill, the second bailiff,” Mr. Hurd answered. “He’s captain, and he can stay in all day, but he can’t make runs.”

They all leaned forward to witness the continuation of the match. Stephen Hurd’s career was brief and inglorious. He took guard and looked carefully round the field with the air of a man who is going to give trouble. Then he saw the victoria, with its vision of parasols and fluttering laces, and the sight was fatal to him. He slogged wildly at the first ball, missed it, and paid the penalty. The lady in the carriage frowned, and Mr. Hurd muttered something under his breath as he watched his son on the way back to the tent.

“I’m afraid it’s all up with us now,” he remarked. “We have only three more men to go in.”

“Then we are going to be beaten,” Wilhelmina remarked.

“I’m afraid so,” Mr. Hurd assented gloomily.

The next batsman had issued from the tent and was on his way to the wicket. Wilhelmina, who had been about to give an order to the footman, watched him curiously.

“Who is that going in?” she asked abruptly.

Mr. Hurd was looking not altogether comfortable.

“It is the young man who wanted to preach,” he answered.

Wilhelmina frowned.

“Why is he playing?” she asked. “He has nothing to do with Thorpe.”

“He came down to see them practise a few evenings ago, and Antill asked him,” the agent answered. “If I had known earlier I would have stopped it.”

Wilhelmina did not immediately reply. She was watching the young man who stood now at the wicket, bat in hand. In his flannels, he seemed a very different person from the missioner whose request a few days ago had so much offended her. Nevertheless, her lip curled as she saw the terrible Mills prepare to deliver his first ball.

“That sort of person,” she remarked, “is scarcely likely to be much good at games. Oh!”

Her exclamation was repeated in various forms from all over the field. Macheson had hit his first ball high over their heads, and a storm of applause broke from the bystanders. The batsman made no attempt to run.

“What is that?” Wilhelmina asked.

“A boundary—magnificent drive,” Mr. Hurd answered excitedly. “By Jove, another!”

The agent dropped his reins and led the applause. Along the ground this time the ball had come at such a pace that the fieldsman made a very half-hearted attempt to stop it. It passed the horses’ feet by only a few yards. The coachman turned round and touched his hat.

“Shall I move farther back, madam?” he asked.

“Stay where you are,” Wilhelmina answered shortly. Her eyes were fixed upon the tall, lithe figure once more facing the bowler. The next ball was the last of the over. Macheson played it carefully for a single, and stood prepared for the bowling at the other end. He began by a graceful cut for two, and followed it up by a square leg hit clean out of the ground. For the next half an hour, the Thorpe villagers thoroughly enjoyed themselves. Never since the days of one Foulds, a former blacksmith, had they seen such an exhibition of hurricane hitting. The fast bowler, knocked clean off his length, became wild and erratic. Once he only missed Macheson’s head by an inch, but his next ball was driven fair and square out of the ground for six. The applause became frantic.

Wilhelmina was leaning back amongst the cushions of her carriage, watching the game through half closed eyes, and with some apparent return of her usual graceful languor. Nevertheless, she remained there, and her eyes seldom wandered for a moment from the scene of play. Beneath her apparent indifference, she was watching this young man with an interest for which she would have found it hard to account, and which instinct alone prompted her to conceal. It was a very ordinary scene, after all, of which he was the dominant figure. She had seen so much of life on a larger scale—of men playing heroic parts in the limelight of a stage as mighty as this was insignificant. Yet, without stopping to reason about it, she was conscious of a curious sense of pleasure in watching the doings of this forceful young giant. With an easy good-humoured smile, replaced every now and then with a grim look of determination as he jumped out from the crease to hit, he continued his victorious career, until a more frantic burst of applause than usual announced that the match was won. Then Wilhelmina turned towards Stephen Hurd, who was standing by the side of the carriage.

“You executed my commission,” she asked, “respecting that young man?”

“The first thing this morning,” he answered. “I went up to see Mrs. Foulton, and I also spoke to him.”

“Did he make any difficulty?”

“None at all!” the young man answered.

“What did he say?”

Stephen hesitated, but Wilhelmina waited for his reply. She had the air of one remotely interested, yet she waited obviously to hear what this young man had said.

“I think he said something about your making war upon a large scale,” Stephen explained diffidently.

She sat still for a moment. She was looking towards the deserted cricket pitch.

“Where is he staying now?” she asked.

“I do not know,” he answered. “I have warned all the likely people not to receive him, and I have told him, too, that he will only get your tenants into trouble if he tries to get lodgings here.”

“I should like,” she said, “to speak to him. Perhaps you would be so good as to ask him to step this way for a moment.”

Stephen departed, wondering. Deyes was watching his hostess with an air of covert amusement.

“Do you continue the warfare,” he asked, “or has the young man’s prowess softened your heart?”

Wilhelmina raised her parasol and looked steadily at her questioner.

“Warfare is scarcely the word, is it?” she remarked carelessly. “I have no personal objection to the young man.”

They watched him crossing the field towards them. Notwithstanding his recent exertions, he walked lightly, and without any sign of fatigue. Deyes looked curiously at the crest upon the cap which he was carrying in his hand.

“Magdalen,” he muttered. “Your missioner grows more interesting.”

Wilhelmina leaned forwards. Her face was inscrutable, and her greeting devoid of cordiality.

“So you have decided to teach my people cricket instead of morals, Mr. Macheson,” she remarked.

“The two,” he answered pleasantly, “are not incompatible.”

Wilhelmina frowned.

“I hope,” she said, “that you have abandoned your idea of holding meetings in the village.”

“Certainly not,” he answered. “I will begin next week.”

“You understand,” she said calmly, “that I consider you—as a missioner—an intruder—here! Those of my people who attend your services will incur my displeasure!”