a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Picturesque New Guinea Author: J W Lindt * A Project Gutenberg Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1202541h.html Language: English Date first posted: July 2012 Date most recently updated: July 2012 Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

01. Motu Water Carrier, Port Moresby

For years past, when perusing the account of exploring expeditions setting out for some country comparatively unknown, I always noticed with a pang of disappointment that, however carefully the scientific staff was chosen, it was, as a rule, considered sufficient to supply one of the members with a mahogany camera, lens, and chemicals to take pictures, the dealer furnishing these articles generally initiating the purchaser for a couple or three hours' time into the secrets and tricks of the "dark art," or when funds were too limited to purchase instruments, it was taken for granted that enough talent existed among the members to make rough sketches, which would afterwards be "worked up" for the purpose of illustrating perhaps a very important report.

Sir Samuel Baker remarks, in the Appendix to one of his Works, that a photographer should accompany every exploring expedition. The only one I ever heard of being furnished with that commodity was H.M.S. "Challenger," on her scientific cruise round the world, but I remember reading in the "Photographic News" the complaint of a gentleman, that so many years had already passed, and still there was no sign of the "Challenger" photographs ever becoming accessible to the public.

How this is, or why it should be so, is difficult to tell, but as yet no book of travel, entirely illustrated by artistic views and portraits taken direct from nature, has come under my notice. According to my belief, there can be but one reason for it, and that is the difficulties encountered to find a competent artist photographer willing to join an expedition are greater than those necessary to secure the services of someone who can sketch, and hence artistic photography, the legitimate and proper means to show friends at home what these foreign lands and their inhabitants really look like, is set aside for drawings, either partly or purely imaginary.[*]

[* Though this book was written and the pictures taken under this impression, I found, on arrival in England, that several works of travel illustrated by photography have been published. I had the pleasure of meeting Mr. John Thomson, F.R.G.S., of Grosvenor Street, who showed me his magnificent and interesting work on "China and its Peoples." I examined also Sir Lepel Griffin's clever work, "Famous Monuments of Central India," and a little book on Tahita, by Lady Brassey, ably illustrated by Col. H. Stuart-Wortley. The illustrations in these Works consist without exception of photographs printed in autotype, and the inspection of these books and their pictures at once put me face to face with the countries described and their inhabitants, far more vividly than could works illustrated by wood engravings, where, for truth, the reader depends firstly on the individual conception of the artist, and secondly on the skill of the engraver.]

Ever since I first passed through Torres Straits in September, 1868, I conceived an ardent desire to become personally acquainted with those mysterious shores of Papua and their savage inhabitants. I travelled this route on board a Dutch sailing vessel, and weird indeed were the tales that circulated among the crew concerning the land whose towering mountain ranges were dimly visible on our northern horizon. But years passed by, and time had almost effaced the impression, until I made the acquaintance of Signor L. M. D'Albertis, the intrepid Italian, who explored the Fly River higher up than anyone has ventured since. This occurred in 1873. Signor D'Albertis visited the Clarence River, in New South Wales, where I lived for many years, by way of recruiting his health after his voyages to N. W. New Guinea. How I fretted that circumstances prevented me from accompanying him on his first trip in the "Newa," and how I envied young Wilcox (the son of a well known Naturalist residing on the Clarence) being engaged as assistant collector, no one knows but myself. Again some years elapsed, and when next I met D'Albertis it was at Melbourne, in 1878. His personal reminiscences, and subsequently the reading of his interesting work, powerfully awakened my desire again for a trip to New Guinea. But circumstances were still adverse, and it was only when rumours of annexation became rife, and the Rev. Mr. Lawes visited Melbourne early in 1885, that the prospect of visiting the land of my dreams began to assume a more tangible form.

Mr. Lawes, hearing me speak so enthusiastically about my long cherished desire, assured me of his readiness to assist, and of hospitality, should I come to Port Moresby. The reverend gentleman's kindness and goodwill were amply proved, as my narrative will show, but be it here recorded, with due deference, I believe he doubted at that time the likelihood of ever seeing me sit at his table in the broad verandah of the mission house, listening to Mr. H. C. Forbes' reminiscences of the interior of Sumatra (the exhumation and ultimate fate of "that Kubu woman" to wit).

A month or so after Mr. Lawes' departure from Australia, the papers reported the intelligence that Sir Peter Scratchley had been appointed High Commissioner for the Protectorate of New Guinea, and that a properly equipped expedition was to be sent to investigate the newly acquired territory. Now or never was my chance. Colonel F. T. Sargood kindly introduced me to Sir Peter, I offered to accompany the expedition as a volunteer, finding myself in every requisite, and giving copies of the pictures I should succeed in taking in return for my passage and the necessary facilities to develop and finish my negatives on board.

My offer was accepted by Sir Peter, and on July 15th, 1885, I received notice to join the "Governor Blackall," the vessel selected for the expedition, then lying in Sydney Harbour.

The command of the "Governor Blackall" was entrusted to Captain T. A. Lake, the senior captain of the A. S. N. Company's fleet, who, throughout the voyage, sustained his high character as a skilful navigator among coral reels, and proved himself a man of tact and decision, qualities that were more than once put to the test during our cruise. Before launching into the description of the expedition, I wish to record here my deep sense obligation to the gentlemen who kindly aided in the production of this Work by contributing chapters of valuable information. In the first place my thanks are due to the Rev. James Chalmers, who kindly continued the thread of the narrative, and brought it to a conclusion, when I was obliged to leave the expedition at Samarai (Dinner Island) about a month before the lamented death of Sir Peter Scratchley. I am also greatly indebted for his interesting paper on "The Manners and customs of the Papuans." On that subject no better source of information than him could be found. To Mr. G. S. Fort I offer my best thanks for presenting me with his Official Report of the Expedition. The same recognition is due to Sir Edward Strickland, the President of the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia, for the permission to embody in my journal the interesting account of the "Bonito" Expedition, undertaken under the auspices of the Royal Geographical Society almost simultaneously with ours. My appeal to Mr. Edelfeld, now exploring in Motu Motu, met with a ready response from that gentleman in the shape of travelling experiences in the neighbourhood of Mount Yule.

Last, but not least, I have to thank my learned countryman and friend. Sir Ferdinand Baron Von Müller, the eminent Botanist, for the promise of a valuable essay from his pen, although, unhappily, the pressure of departmental work on his hands is at present so severe that his contribution cannot be ready for this, the first edition of my book; and I cannot conclude without acknowledging my indebtedness to Commander H. Field, of H. M. Surveying Schooner "Dart," and to his able officers, Lieutenants Messum and Dawson, not forgetting Dr. Luther, who, with their uniform kindness and courtesy, made my return journey on board that vessel a perfect pleasure trip.

J. W. LINDT.

Melbourne, 1887.

P.S.--With regard to the publication of this Work much credit is due to Mr. Bird, of the Autotype Company. Arriving as I did, a stranger in London, this gentleman materially lightened my labours by introducing me to Messrs. Longmans, the publishers, and contributing his experience freely. My thanks are also due to Mr. Sawyer and his clever staff, for the masterly reproduction of my pictures, upon which the success of the book mainly depends.

02. Portrait of Author, J. W. Lindt, F.R.G.S.

PREFACE

CHAPTER I.--HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF NEW GUINEA.

Geographical Positions--First Discoveries--First Explorers--The

Missionaries--Dutch Settlement--English Surveys of the Coast--Attempts of

Australian Settlement--Annexation by Queensland--Refusal of Imperial

Sanction--Australian Colonists Remonstrate--Proposal of a British

Protectorate--Annexation by Great Britain--Dissatisfaction of the

Colonists--Announcement of German Occupation--Arrival of Sir Peter

Scratchley--His first Proceedings and Premature Death--Appointment of a

Successor--The German Settlement

CHAPTER II.--From Sydney to New Guinea.

Colonists Demand Annexation of New Guinea--Lord Derby's

Vacillation--Appointment of Sir Peter Scratchley as High Commissioner--His

Arrival and first Proceedings--Departure from Sydney--Pathetic Parting of the

Commissioner and his Family--A Sabbath Day on Board--Northwards to

Brisbane--Description of the "Governor Blackall"--Music hath Charms to soothe

the hardy Seaman's breast--An Eminent Naturalist--Gentle Savages--Departure

from Brisbane--A New Patent Log--The Tragedy of Percy Island--A Strange Ocean

Product--An Island Paradise--An Apron Signal--Townsville--Meeting with a

"Vagabond"--Cooktown--The Tragedy of Lizard Island--New Guinea in Sight

CHAPTER III.--FIRST LANDING IN NEW GUINEA.

First View of Papua--Breakers Ahead--Haven of Safety reached--First

Welcome--The Missionary and his Wife--Excursion to Rano Falls planned--Native

Villages on the Littoral--Frolicsome Young Savages--A Degraded Race--A tribe of

potters--A Strange Flotilla--Preparations for Excursion--A Christian Salbath in

a Savage Land--Elevating Influence of Christianity--A Photographer's

Impedimenta--First Landing--Religious Service in the Motu Language--"Granny"

the Prime Minister--A Start resolved on--A Guide and Carriers engaged--Also a

Native Head Cook

CHAPTER IV.--FIRST EXCURSION IN NEW GUINEA.

Orders to March--Heavy Travelling--Tropical Creek--Sure-footed Mountain

Steeds--Native Hunting Camp--Luncheon in the Forest--Smoking the Bau Bau--Good

Country for Horse-breeding--Koiari Kangaroo-hunting--The Hunter's Feast--The

Koiari Tribe--Splendid Natural Panorama--Morrison's Explorations--Camp for the

Night--Perilous Journeying--The Alligators' Haunt--Night in the Papuan

Forest--Frightening the Devil--Fears of Danger from Natives dispelled--Morning

in the Forest--A Purpose abandoned--Strike for a Koiari Village--Savage

Gourmands--Steep Mountain Ascent--Magnificent Mountain Scenery--A Koiari

Welcome--A Mountain Village--Dwellings on the Tree-tops--A Koiari

Chief--Photographer in Koiari--Hospitable Offer--A Koiari Household--Great

White Chief--Buying a Pig--A Koiari Interior--A Papuan Meal--Conference of

Chiefs--Papuan Etiquette--A Tribal Feud--Uncomfortable Night--Superb Mountain

Views--The Photographer in a Koiari Village--Return to the Port--A Ruined

Village--Native Remains--Encounter Mr. Forbes--Missionary Hospitality

CHAPTER V.--EXCURSION UP THE AROA RIVER.

Site Fixed for Government House and Buildings--Bootless Inlet--Lakatoi Trading

Vessels--Native Regatta--Quit Port Moresby for Redscar Bay--Landing of the

Party--The Mouth of the Aroa--Ascent of the Stream--Reflections on

Land-tenure--Visit to Ukaukana Village--Interview with the Head Chief of

Kabadé--Exchange of Presents--Adventures returning to Camp--Night

Alarms--The Vari Vara Islands--Back to Port Moresby

CHAPTER VI.--A COASTING EXPEDITION.

Arrival of H.M.S. "Raven"--Trade Winds--Site for Government Stores--Inland

Party organized--Arrival off Tupuselei--Coast Scenery--A Papuan Venice--Sir

Peter Scratchley's Visit to Padiri--Sickness among the Party--A Native

Feud--Attack apprehended--Kapa Kapa--A Group of Mourners--Mangoes--Birds of

Paradise--A Palaver--Continuation of the Voyage

CHAPTER VII.--AN EXPEDITION INLAND.

Walk from Hula to Kalo--Cocoanut Groves--Native Diseases--Mortality--History of

the Reprisals for Murdering--Price of a Wife--Matrimonial Customs--The Author

leaves Kalo--Crossing a River--Arriving at Hood Lagoon--Rejoin the Ship

CHAPTER VIII.--NATIVE VILLAGES.

Scenery at the Hood Lagoon--Kerepunu, Hula--Fracas between the Ship's Company

and Natives--Beneficial Results--Start for Aroma--A Native Chief as

Passenger--Parimata--Moapa--The Aroma District--Departure for Stacey

Island--The Scenery Described

CHAPTER IX.--SOUTH CAPE.

Bertha Lagoon--Garihi--Ascent of the Peak--East Shores of the Lagoon--Under

Way--The Brumer Group--Rendezvous at Dinner Island--Murder of Captain

Miller--Investigations at Teste Island

CHAPTER X.--SEARCHES FOR MURDERERS.

Return to Dinner Island--Rendezvous with H.M.S. "Diamond" and

"Raven"--Excursion to Heath Island--Departure for Normanby Island--Diaveri--An

Exciting Chase--Fruitless Negotiations--Capture of an Alleged Murderer--A

Mistake and its Rectification--The Real Simon Pure--His Adventures in

Sydney--Return of the Author in H.M.S. "Dart"

CHAPTER XI.--MR. CHALMERS' NARRATIVE.

Visit to Killerton Islands--The Juliade Islands--Reprisals for the Murder of

Captain and Mrs. Webb--Colombier Point--Unsuccessful Attempt to Communicate

with Natives--Hoisting the Union Jack at Moapa--Inland Excursion to Koiari

Villages--Ascent of Mount Variata--Meet Mr. Forbes--Sogeri--Mr. Forbes'

Station--Return to Port Moresby and Hula--Bentley Bay--Ascent of Mount

Killerton--Illness of Sir Peter Scratchley--Character of the Coast--The

Jabbering Islands--From Collingwood Bay to Cape Nelson--Mountains and

Harbours--Departure of the "Governor Blackall" for Australia--Illness of Sir

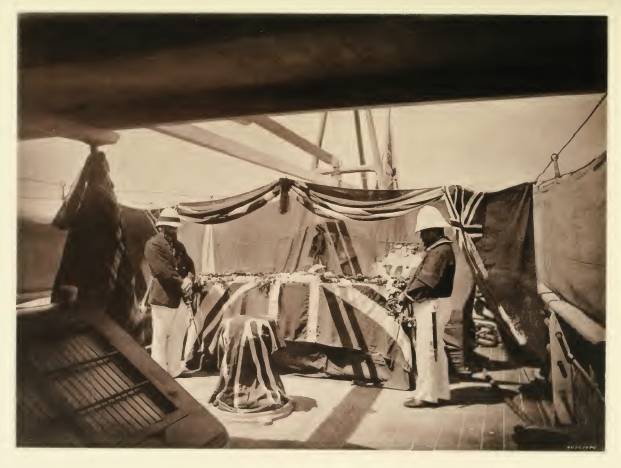

Peter Scratchley--His Death--His Funeral

CHAPTER XII.--TWO NEW GUINEA STORIES BY JAMES CHALMERS,

F.R.G.S.

I. Veata of Maiva--II. The Koitapu Tribe and their Witchcraft

CHAPTER XIII.--HISTORY AND DESCRIPTION OF POTTERY

TRADE.

A Papuan "Enoch Ardon," by James Chalmers, F.R.G.S

CHAPTER XIV.--TRAVELS IN THE NEIGHBOURHOOD OF MOUNT

YULE.

Motu Motu and Customs of the People, by E. G. Edelfeld, M.R.G.S.

APPENDIX I.--BRITISH NEW GUINEA.

Report on British New Guinea, from Data and Notes by the Late Sir Peter

Scratchley, Her Majesty's Special Commissioner, by Mr. G. Seymour Fort. Private

Secretary to the late Sir Peter Scratchley, R.E., K.C.M.G.

APPENDIX II.--"THE BONITO" EXPEDITION.

Captain Everill's Report of the Royal Geographical Society's Expedition to the

"Fly, Strickland, Service, and Alice Rivers"

APPENDIX III.--GERMAN NEW GUINEA EXPLORATION

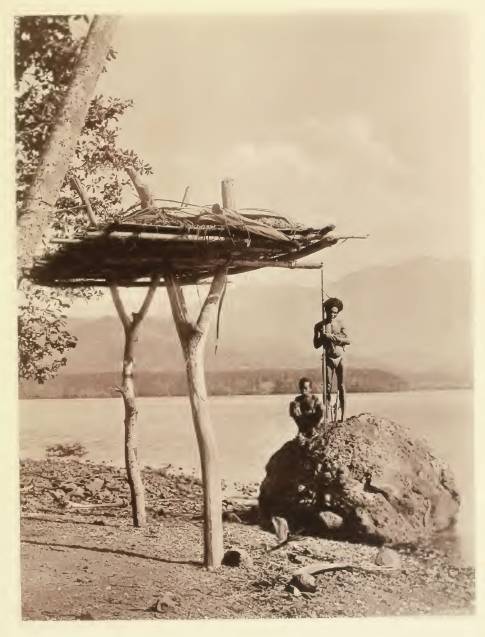

01. Motu Water Carrier, Port Moresby

02. Portrait of Author, J. W. Lindt, F.R.G.S.

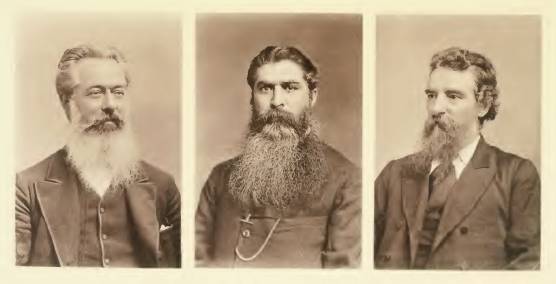

03. Portraits of the Revs. S. McFarlane, G. W. Lawes,

and James Chambers

04. "The Start." Sir Peter Scratchley, his Staff and

Party of Friends, S.S. "Governor Blackall"

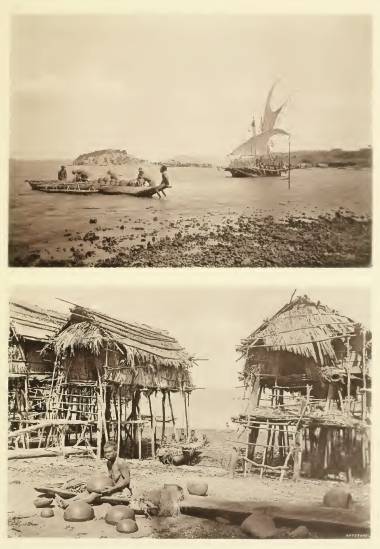

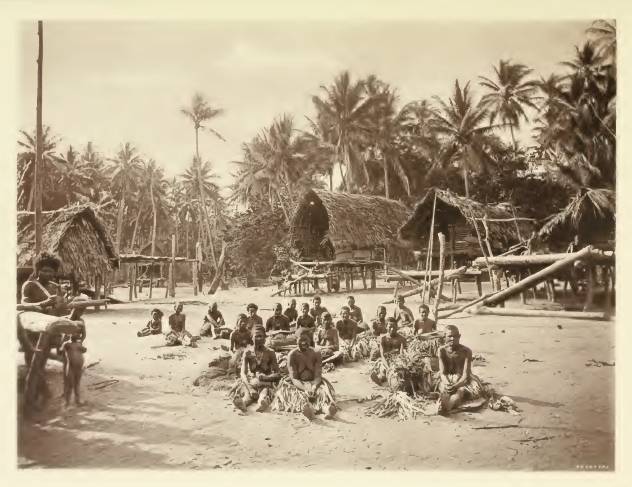

05. Loading Lakatoi, Port Moresby — Women making

Pottery

06. Lakatoi, or Motu Trading Vessel, under Sail

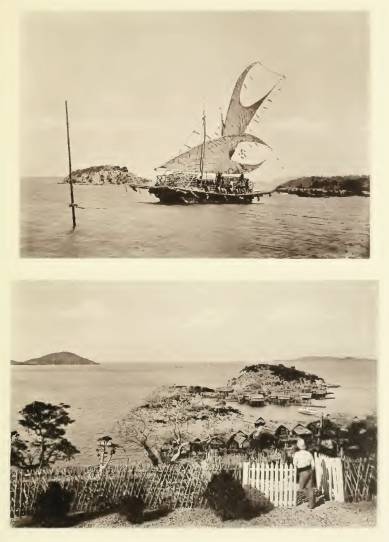

07. Lakatoi near Elevala Island—Elevala Island,

from Mission Station

08. Koiari Chiefs

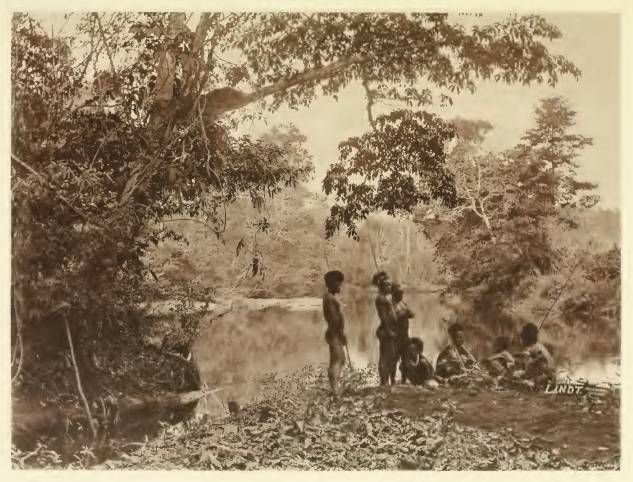

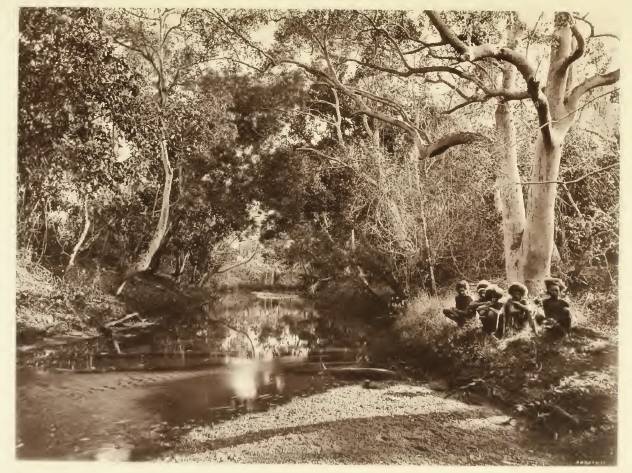

09. The Haunt of the Alligator, Laloki Eiver

10. Roasting Yams for Breakfast, Badeba Creek

11. Near the Camp, Laloki River

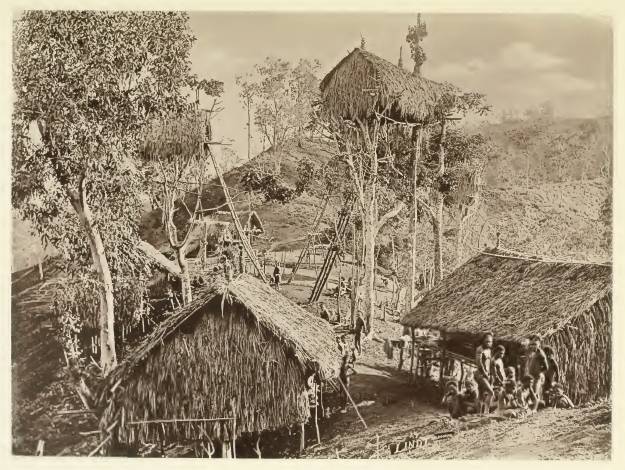

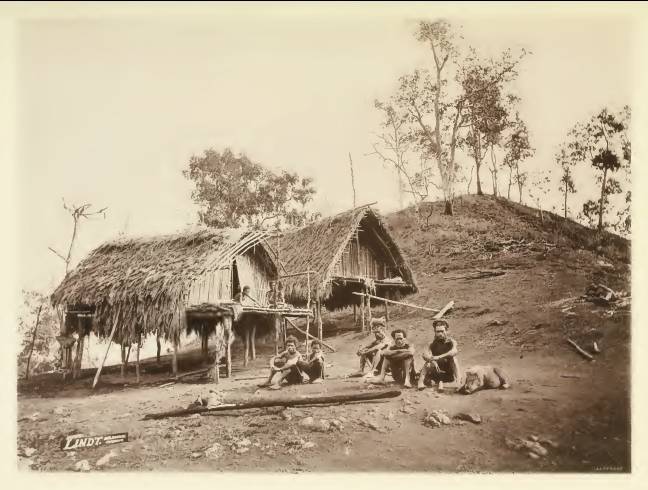

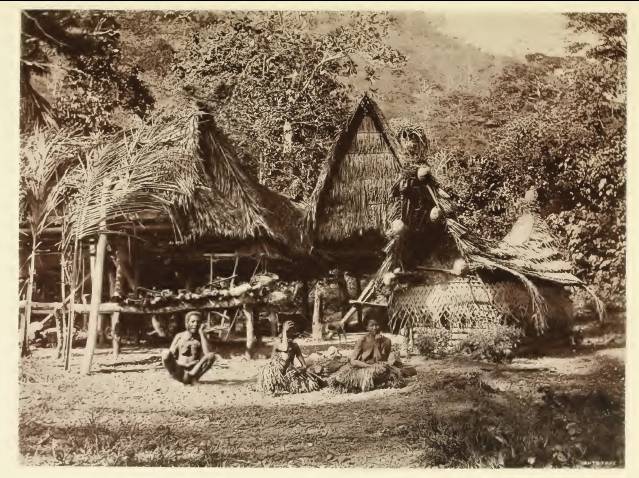

12. Sadãra Makãra, Koiari Village near

Bootless Inlet

13. The Village Pet at Sadãra Makãra

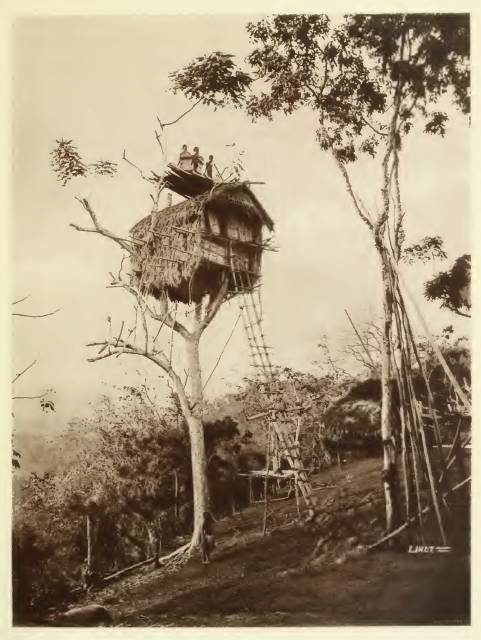

14. Tree-house, Koiari Village

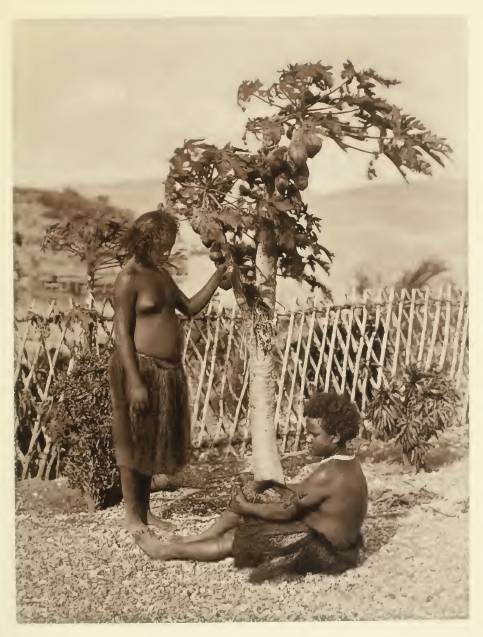

15. Motu Girls, Port Moresby, also Paro Paro Apple

Tree

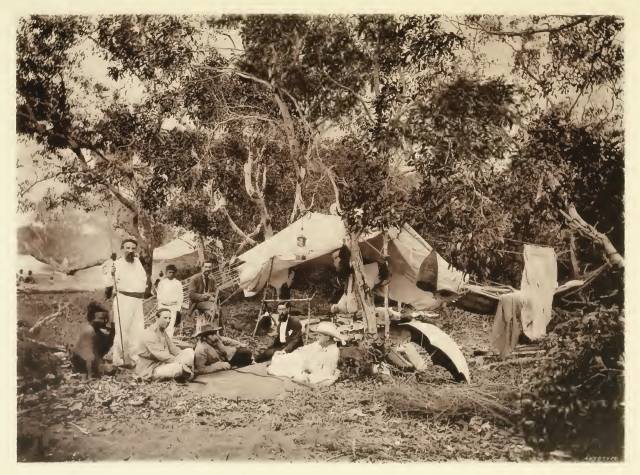

16. Sir Peter Scratchley's Camp, near Mouth of Aroa

Eiver, Redscar Bay

17. Native House at Vanuabada, Kabade District

18. Native Teachers, Kabade District

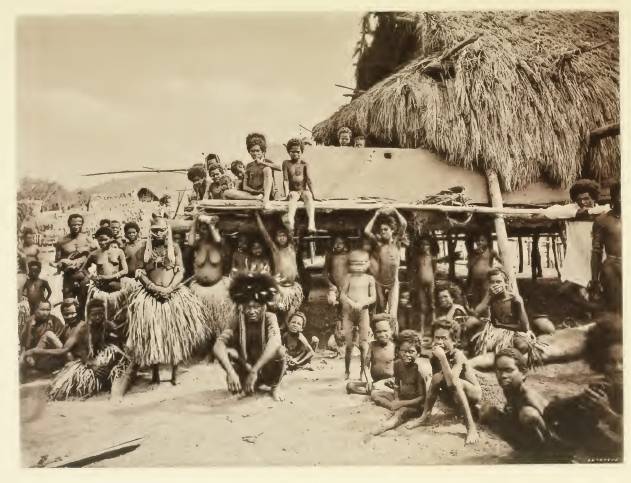

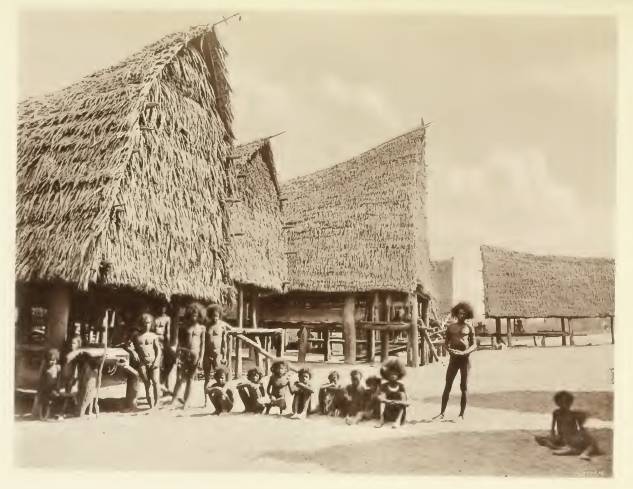

19. Village of Koilapu, Port Moresby

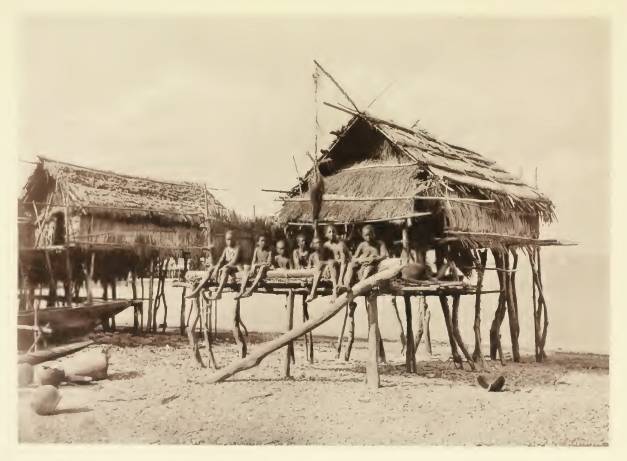

20. At Low Water, Native Houses at Koilapu

21. H. 0. Forbes and Party of Malays, also Captain

Musgrave and Mr. Lawes

22. Tupuselei (Marine Village) from the Shore

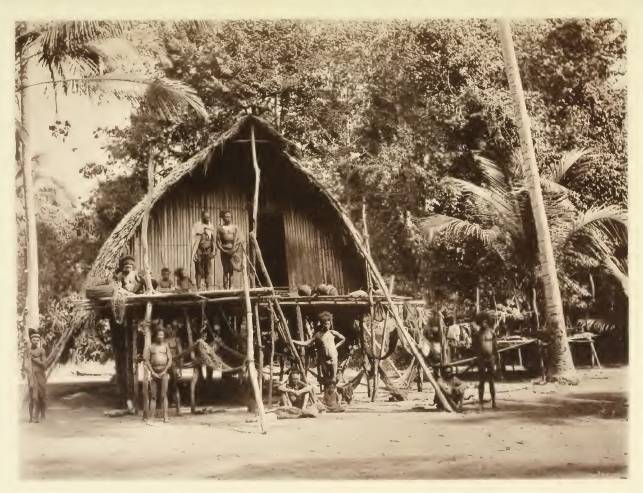

23. The Chief's House, Marino Village of Tupuselei

24. Women of Tupuselei going for Water

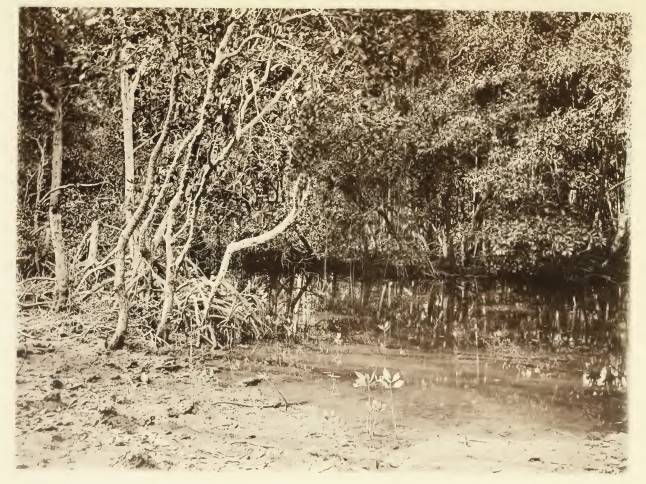

25. Mangrove Scrub, near Kaele

26. Group of Natives at Kapa Kapa, central figures in

mourning

27. The Kalo Creek, Kapa Kapa District

28. New Guinea Trophy, Weapons and Implements

29. Native House at the Village of Kamali

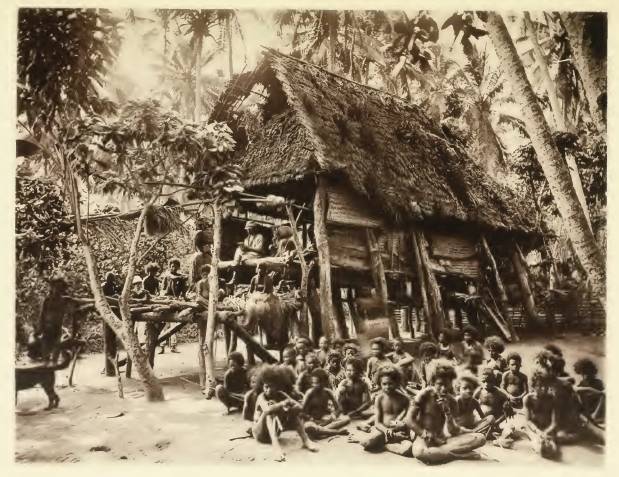

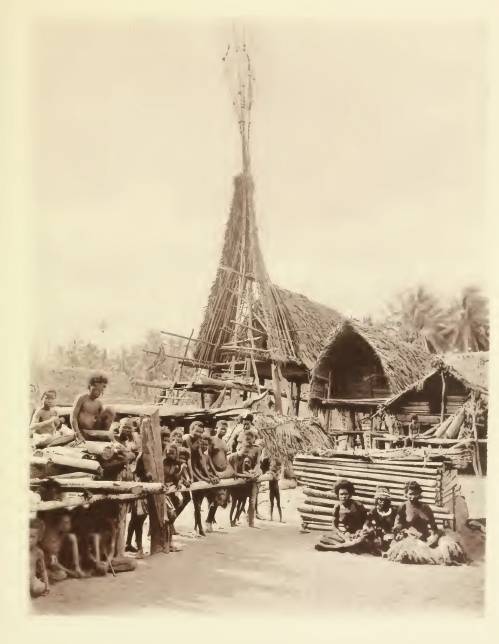

30. The Chief's Spire House at Kalo (in course of

re-construction)

31. Mourners and Dead-house at Kalo

32. Village Scene at Kalo, with Teacher and Christian Church (not included in

the book)

33. Kerepunu Women at the Market Place of Kalo

34. Village Scene at Moapa, Aroma District

35. Native Houses and Graves at Suau, Stacey Island

36. Garihi Village, Bertha Lagoon, South Cape

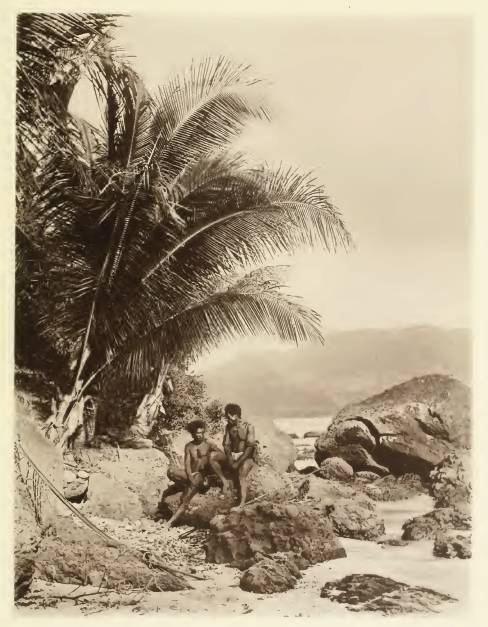

37. Boating Scene, Bertha Lagoon and Cloudy Mountains

in the Distance

38. Magiri Village, Bertha Lagoon, South Cape

39. Group and Native House, Mairy Pass, Mainland of New

Guinea in the Distance

40. Young Cocoanut Trees on Stacey Island, Farm Peak in

the Distance

41. Platform for Dead Bodies, South Cape, New

Guinea

42. Naria Village, South Cape, New Guinea

43. On the Beach, Teste Island, Kissack's trading

Canoe, Bell Rock and Cliffy Island in the Distance

44. Paddles, Native Ornaments, and Implements from the

Neighbourhood of Dinner Island and China Straits

45. Village at Slade Island (Engineer Group)

46. The Voyage Homeward, on board H.M.S. "Dart" (on the

Job)

47. "The End," Sir Peter Scratchley's Catafalque, on

board S.S. "Governor Blackall"

48. The Honourable John Douglas, C.M.G., Sir Peter

Scratchley's Successor; Captain T. A. Lake, Senior Captain of the A.S.N.

Company's Fleet, and Commander of the S.S. "Governor Blackall" (on one

Plate)

49. Sir Peter Scratchley, K.C.M.G., and Mr. G. Seymour

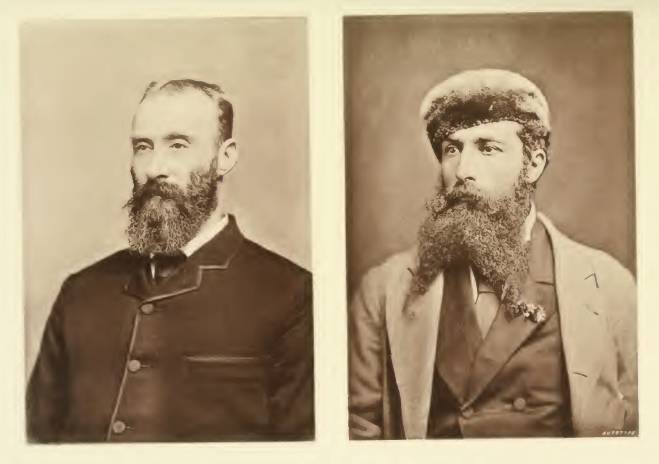

Fort, Private Secretary (on one Plate)

50. Fly River Explorers, Signer Luigi Maria D'Albertis,

and Captain H. C. Everill (on one Plate)

Geographical Positions—First Discoveries—First Explorers—The Missionaries—Dutch Settlement—English Surveys of the Coast—Attempts of Australian Settlement—Annexation by Queensland—Refusal of Imperial Sanction—Australian Colonists Remonstrate—Proposal of a British Protectorate—Annexation by Great Britain—Dissatisfaction of the Colonists—Announcement of German Occupation—Arrival of Sir Peter Scratchley—His first Proceedings and Premature Death—Appointment of a Successor—The German Settlement

New Guinea, the latest addition to the magnificent Colonial empire now owned by Great Britain, is the largest island on our globe, counting Australia as a sixth continent. It lies to the north of Australia, from which it is separated by a narrow strait named after Torres, a Spanish navigator, who, in 1606, sailed through it on his way from the New Hebrides to the Philippine Islands.

First Discoverers.—It is doubtful whether anything relating to this large island was known to the European world before the time of Columbus. No mention of it is found in the works of any of the ancient geographers. The earliest reference to it that can be traced is given in the narrative of their voyages and adventures left by two Portuguese navigators, Francisco Sorrani and Antonio d'Abreu, who in 1511 saw and described a portion of the south-west coast. In the absence of any fuller information on the subject, the honour of discovering New Guinea falls to these two adventurers. Fifteen years later another Portuguese navigator, Don Jorges Menenes, was voyaging Malacca to the Moluccas, and encountering a storm, was driven out of his course to the eastward, and came upon the great island, where, finding a safe and convenient harbour, he remained for a month to refit his shattered vessel. He named the island Papua, a Malayan expression for black or curly hair, which is a very marked feature of the native population. Under that name New Guinea is shown on a chart published in Venice in 1554. Another Portuguese mariner visited the island in 1528, and gave it the high sounding title of the Isla del Oro, or Island of Gold, from a belief that it abounded in the precious metals. But the honour of giving the island the name it will bear permanently falls to Inigo de Retez, a Spanish sailor, who in 1545 sailed 250 miles along the northern coasts, and, thinking that he saw in the appearance of the country a resemblance to the Guinea coast on the west of Africa, called it Nueva Guinea. The next we hear of the place is an account given by Torres of the southern portion and its inhabitants, whom he describes as being "dark in colour, naked except having some clothing round the middle, and armed with clubs and darts ornamented with tufts of feathers." Schouten, a Dutch navigator, discovered some volcanoes in the island in 1616. Twenty-seven years later Abel Janez Tasman, the greatest of the Dutch navigators and the discoverer of Tasmania (which he named Van Dieman's Land) and of New Zealand, visited and minutely examined a portion of the west coast. On the New Year's Day of the year 1700, William Dampier, the prince of English maritime adventurers, voyaging in quest of new lands, sighted New Guinea, and never left it until he had sailed completely round it, although his vessel (named the "Roebuck") was both old and leaky. His account of the place and people is very racily written, and was probably read by De Foe before he wrote "Robinson Crusoe." "The natives," he says, "are very black; their short hair is dyed of various colours—red, white, and yellow: they have broad, round faces with great bottle-noses, yet agreeable enough, except that they disfigure themselves by painting and wearing great things through their noses, as big as a man's thumb and about four inches long. They have also great holes in their ears, wherein they stuff such ornaments as in their noses." The illustrious navigator, Cook, rediscovered Torres Strait in 1772, and added much to the previous knowledge of the island and its inhabitants. In 1828 the Dutch took possession of the western portion and attempted to make a settlement there, but failed. In 1843 Captain Blackwood, in H.M.S. "Fly," discovered the river, which he named after his ship. Subsequently, Captain Owen Stanley, in the "Rattlesnake," made a rough survey of a great portion of the coast, and in 1873 Captain Moresby, in the "Basilisk," completed our knowledge of the external form and dimensions of New Guinea.

First Explorers.—Up till very recently the only information possessed by the civilised world respecting the island and its inhabitants amounted to little more than that the people were negroes, and that beautiful birds of paradise were to be found there. Alfred Wallace, the distinguished naturalist, was the first European that gave the world a larger knowledge of the native population and the natural productions. After him came Dr. Mickluoho Maclay, in 1871. He lived with the natives for fifteen months, enduring the severest privations and risking his life in the cause of science. But amongst the explorers of New Guinea pre-eminence must be given to Signor D'Albertis, who, in 1872, in company with his fellow-countryman. Dr. Beccari, penetrated into the interior in many directions, and made himself intimately acquainted with the names and habits of the natives. At various subsequent times Signor D'Albertis continued his explorations and observations, the results of which he has given to the world in two handsome volumes beautifully illustrated. This distinguished Italian is a born explorer. He is possessed with the true spirit of martyrdom in the cause of science. His pluck, perseverance and patience, seem only to grow with the difficulties he has to encounter, and the obstacles he has to overthrow. His personal privations and sufferings wring from him no complaints; and he merely records them in his simple matter-of-fact manner as among the facts and incidents of the time, and as affording an insight into the ideas and ways of the natives in view of such circumstances. A German explorer, Dr. A. J. Meyer, made some important additions to our knowledge of the country by explorations, vigorously prosecuted in 1873. Dr. Beccari, alone, went on an expedition into the interior in 1875, and returned with a large and valuable collection of specimens of the flora and fauna of the island.

The Missionaries.—Those active pioneers of civilisation, the English missionaries, have not neglected New Guinea; but their work amongst the natives has been seriously hindered by the unhealthiness of the country and climate. The Rev. S. McFarlane was appointed by the Directors of the London Missionary Society to establish a mission in the island in 1870. With him was associated the Rev. Mr. Murray; and subsequently the Rev. W. G. Lawes and the Rev. James Chalmers joined the mission. The labours of these gentlemen amongst the native population have been of a quite heroic kind; and to them is mainly due the merit of taking possession of the country for the British people. At the hourly risk of their lives they have carried on their apostolic labours, facing a thousand dangers, overcoming a thousand difficulties, unwearied in their high purpose of civilising and Christianising this savage people. They have established primary school training institutions, for native teachers, schools for teaching the industrial arts, mission stations at many points along the coast, and churches with regular congregations and enrolled members. A real triumph of missionary achievement was witnessed at the mission station on Murray Island on the 14th May, 1885, when the 15-ton mission yacht, Mary, was launched from the yard of the Papuan industrial school, amid great feasting and rejoicing. The wood for the little vessel had been cut, and the building of it was executed by the hands of the pupils of the school under the supervision of the Rev. Mr. McFarlane. The yacht is intended for missionary work in and about the Fly River.

03. Portraits of the Revs. S. McFarlane, G. W. Lawes, and James

Chambers

Dutch Settlement.—So far as is known, the Dutch, as already stated, were the first European nation to attempt settlement in New Guinea. In 1828 Captain Steenboom, in the ship "Triton," landed on the island and took possession in the name of the Dutch Government of the territory extending from the 141st parallel of E. longitude westward to the sea. He built a fort at a place he called Triton Bay, on the N.W. coast, the scenery around which was very beautiful. But (as a Dutch gentleman at Macassar told Wallace) the officer left in charge of the settlement, finding the life there insufferably monotonous, killed the cattle and other live stock, and reported that they had perished through the unhealthiness of the place, and that, besides, the natives were very fierce and intractable. The settlement at Triton Bay was on this account abandoned. Seven years later another Dutch commander surveyed what was then called the Dourga River, and found it to be a strait, ninety miles long, dividing Frederic Henry Island from the mainland. The Dutch still hold nominal possession of the territory proclaimed by Captain Steenboom, but practically the acquisition is of no value to them.

English Surveys of the Coast.—The southern shores of New Guinea have been mostly surveyed by British ships. Captain Blackwood, in H.M.S. "Fly," discovered in 1843 the river which he named after his ship. The next English commander that surveyed part of New Guinea was Captain Owen Stanley, who, in 1847, in H.M.S. "Rattlesnake," sketched a large extent of the coast and marked off a number of mountains, one of which, called after him, is over 13,000 feet high. In 1873 Captain Moresby, in the "Basilisk" discovered and named Port Moresby, and determined the form of the south-eastern extremity of the island. Hoisting the Queen's flag he took possession in her Majesty's name, by right of discovery, of Moresby Island and the surrounding archipelago.

Attempts at Australian Settlement.—The Australian colonists have not been wholly indifferent to the probable advantages to be gained from effecting a settlement in New Guinea. During the past twenty years several expeditions have been either planned or partially executed with that object, and the Imperial Government has been again and again asked to take action for the establishment of a British occupation of the territory. To these requests unfavourable answers were given, although it was known at the Colonial Office that so long back as 1793 the island had been formally annexed to Great Britain. In that year, two commanders in the service of the East India Company, William Bampton, Master of the "Hormuzeer," and Matthew B. Alt, Master of the "Chesterfield," were exploring in these waters; and on the 10th July an armed party of forty-four men from the two vessels, under the command of Dell, chief mate of the "Hormuzeer," landed on Darnley Island in Torres Strait, and took possession of that island and the neighbouring island of New Guinea in the name of His Majesty King George the Third. All the formalities customary on such occasions—hoisting the union jack, reading the proclamation, and firing a volley—were duly observed on this occasion. Nevertheless, it was not until nearly a century had elapsed that the imperial authorities at Downing Street condescended to take notice of the fact that there was such a place as New Guinea in existence.

Annexation by Queensland.—The fact was forced upon their attention by the spirited action of the Premier of Queensland, Sir Thomas McIlwraith, who, weary of the rebuffs repeatedly inflicted on the Australian colonists by the colonial office in regard to this matter, patriotically resolved upon annexing New Guinea on his own authority. Accordingly he instructed Mr. H. M. Chester, at that time police-magistrate at Thursday Island, to proceed to the great island, and take possession in the name of Her Majesty the Queen, of all that portion of it which was not claimed by the Netherlands Government. In obedience to these instructions Mr. Chester sailed for New Guinea; and, on the 4th April, 1883, he performed the ceremony of formal annexation of all that part of the territory lying between the 141st and the 155th meridians of east longitude. These facts were duly reported to the Imperial authorities, and strong representations were made to them by the Governments of the United Colonies to induce them to endorse with their approval the action of the Queensland Premier.

Refusal of Imperial Sanction.—But Lord Derby, who then held rule in the Colonial Office, was adverse. He addressed a despatch to the officer administering the Government of Queensland, Sir A. H. Palmer, formally refusing to sanction the act of annexation. At this time it was well known that Germany was meditating the project of taking possession of a part, or the whole of New Guinea; and yet Lord Derby affirmed that there appeared to be no reason for supposing that any Foreign Power harboured such a design. His lordship objected, moreover, to the unnecessarily vast extent, as he deemed it, of the territory annexed by Mr. Chester. The utmost that his lordship would concede was that possibly a protectorate might be established over the coast tribes, under the direction of the High Commission for the Western Pacific, but absolute annexation was quite out of the question.

Australian Colonists remonstrate.—This fresh rebuff, instead of paralysing the Australian colonists, only roused them to greater activity. Mr. Service, Premier of Victoria, was the first to move in the matter. He asked the Governments of the other Colonies to send delegates to an Intercolonial Convention, at which this and other questions would be considered. The request met with immediate and general compliance. Accordingly, the Convention assembled in Sydney in November, 1883; all the Australasian Colonies were represented, and the Governor of Fiji, Sir G. W. Des Voeux, was present, but did not vote. Resolutions affirming the desirability of promptly and effectually securing the incorporation with the British Empire of such parts of New Guinea as were not claimed by the Netherlands Government, were unanimously adopted.

Proposal of a British Protectorate.—To such an emphatic expression of the wishes of the Australian Colonists, Lord Derby could not be indifferent. In May of the following year his lordship addressed a despatch to the Governor of Queensland, intimating that the Imperial authorities were inclined to sanction the appointment of a High Commissioner for New Guinea, provided that the Australian Colonies would agree to pay a subsidy of £15,000 per annum towards the expense of a protectorate. At once the two Colonies of Queensland and Victoria offered to guarantee, between them, payment of the whole amount, and the other Colonies subsequently consented to pay each its quota of contribution, but upon condition that annexation was really intended by the Imperial Government.

Annexation by Great Britain.—In October, 1884, several vessels of war on on the Australian station left Sydney Harbour one by one, bound northwards, and on the 6th November, five British war-ships were lying at anchor in Port Moresby. Commodore Erskine then formally proclaimed the British Protectorate, and the British flag was hoisted with great ceremony, in the presence of about 250 officers and men of the squadron, the missionaries, and as many of the natives and representative chiefs as could be collected for the occasion. All acquisition of land from the natives was forbidden, and regulations prohibiting the introduction of alcohol and firearms were drawn up. A representative chief, Boi Vagi, of Port Moresby, was chosen, and Mr. H. Romilly was left as Acting Commissioner, to enforce the regulations, and to act with authority until the arrival of the High Commissioner. Shortly afterwards the appointment was conferred on Sir Peter Scratchley, who at once proceeded to enter upon his duties.

Announcement of German Occupation.—So far the Imperial Authorities had complied with the wishes of the Australian Colonists, at least in appearance. But the favour shown them was materially lessened in value by the limitation of the area of territory taken under the British protection. They, very naturally, desired that the whole of the island not claimed by the Dutch should be annexed to the British Empire; but Lord Derby drew a line across the map, bisecting the eastern half into two nearly equal parts, and made this line the boundary of the protectorate, leaving the northern section free to be snapped up by any Foreign Power that might choose to take it. With reason the Colonists complained that good faith had not been kept with them, and that their agreement to pay the subsidy of £15,000 a year was invalidated by Lord Derby's act. But his lordship refused to alter his decision, and, unfortunately for the cause of the Colonists, New South AVales, which had formerly been in hearty accord with all its sister Colonies in this matter, drew off now, and stood aloof. It seemed as if the Secretary of State for the Colonies, secretly abetted by the New South Wales Government, was bent upon tacitly inviting some Foreign Power to take possession of the unannexed portion of the island. Before the close of the year—as any person gifted with the least degree of sagacity might have foreseen—the expected claimant made his appearance on the scene. The news flashed along the electric wires in all directions that the German flag was floating over several points along the north-east coast of New Guinea, and on many of the adjacent islands. Fuller information showed that the German Government had formally annexed the whole of the territory marked off by Lord Derby as lying outside the area of the British protectorate, together with the islands of New Britain, New Ireland, and many others in that extensive archipelago. It must be recorded, to vindicate the truth of history, that this intelligence caused a movement of strong indignation in the minds of the Australian Colonists, and vigorous protests against the action of the German Government were addressed by the Australian Agents General to the Imperial Authorities. The feeling of resentment was all the more keen, because the guarantee to pay £15,000 a year towards the expense of the protectorate had been given under a distinct understanding that the whole of New Guinea, excepting the part claimed by the Dutch, should be annexed. Lord Derby, moreover, up till the very hour of the declaration of the German occupation, had denied all knowledge of any such intention on the part of any Foreign Power. With reluctance the Australian Colonists accepted the limitation of area imposed by his lordship; but it was only their fervent loyalty to the British connexion that prevented them from marking in a very emphatic manner their sense of what they held to be a most unjustifiable surrender of the Imperial rights on the part of the Secretary of State for the Colonies.

Arrival of Sir Peter Scratchley.—Sir Peter Scratchley arrived in Australia at the beginning of 1885. His first task was to secure the consent of the several Colonial Governments to share in the payment of the stipulated subsidy for the maintenance of the protectorate. He visited each of the Colonies in succession, and after some demurs on the part of one or two of the governments had been overcome, succeeded in his object. He next chartered a fine steamer, the "Governor Blackall," from the Australian Steam Navigation Company, and on the 20th August sailed for the seat of Government.

His First Proceedings and Premature Death.—He selected Port Moresby as his first station, living on board the "Governor Blackall," and taking a general inspection of the surrounding locality, with a view to selecting a fitting site for the proposed capital of the new protectorate. His intention was to make himself thoroughly acquainted with the country before framing any regulations for the settlement of whites within the territory. It was with this purpose that he joined the expedition, the history of which is narrated in the present volume, and which ended, for him, in his untimely death from the malarial fever incident to the climate. The loss thus caused, both to the Australian Colonies and to the Imperial Interests, was deeply felt and universally mourned.

Appointment of a Successor.—Mr. John Douglas, ex-Premier of Queensland, was appointed by the Imperial Authorities to succeed Sir Peter Scratchley. The new High Commissioner has set himself with characteristic energy to carry out the purposes of his predecessor.

The German Settlement.—The German government has granted a charter to a company to promote settlement in its newly acquired possessions, and very liberal inducements are held out to enterprising adventurers to become the pioneers of the German Colony.

Colonists Demand Annexation of New Guinea—Lord Derby's Vacillation—Appointment of Sir Peter Scratchley as High Commissioner—His Arrival and first Proceedings—Departure from Sydney—Pathetic Parting of the Commissioner and his Family—A Sabbath Day on Board—Northwards to Brisbane—Description of the "Governor Blackall"—Music hath Charms to soothe the hardy Seaman's breast—An Eminent Naturalist—Gentle Savages—Departure from Brisbane—A New Patent Log—The Tragedy of Percy Island—A Strange Ocean Product—An Island Paradise—An Apron Signal—Townsville—Meeting with a "Vagabond"—Cooktown—The Tragedy of Lizard Island—New Guinea in Sight

The repeated demands of the Australasian Colonists for the annexation of New Guinea failed, for a long period, to move the Imperial Government. The policy of Lord Derby, when Secretary of State for the Colonies in Mr. Gladstone's Administration, seemed to be of the Fabian order. His lordship (as Mr. Froude told the Colonists), was in the habit of looking at both sides of a question, and taking time to make up his mind. But somehow the march of events outstripped Lord Derby's calm deliberation. Rumours came abroad that some great Foreign Power was meditating the annexation of the northern island. Stimulated to action by these reports, the patriotic Premier of Queensland, Sir Thomas McIlwraith, resolved upon taking the matter into his own hands, and he despatched an agent to New Guinea with orders to take possession of the territory in the name of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. These orders were promptly obeyed, but the patriotic act did not meet with Lord Derby's approval.

The annexation was disavowed in Downing Street, and the Colonial Minister continued his tranquil meditations on both sides of the New Guinea Question. At length Germany stepped in, and forestalled the fixed purpose of the Australian Colonist. The larger half of the coveted territory was added to the German possessions in the Pacific. Then Lord Derby—doubtless with a feeling of thankfulness to Prince Bismarck for his considerateness in leaving a fragment of the prize unappropriated—bethought him of the propriety of taking steps to secure the interests of his own nation in the matter. His lordship appointed an Imperial Special Commissioner, and despatched him to Australia to obtain the funds requisite for establishing and maintaining a British Protectorate over Southern New Guinea and the adjacent Archipelago.

Sir Peter Scratchley, the newly-appointed Commissioner, set forth upon his mission, and arrived in Melbourne at the close of the year 1884. His first task was to procure a vessel to convey him to his destination, and also suitable for a floating vice-regal residence, pending the erection of a palace on shore. His next business was to obtain from the several Australian Governments contributions towards the salary and expenses of the Special Commissioner. This object was gained without any difficulty, although there was a good deal of grumbling at Lord Derby's remissness in allowing Germany to steal a march upon him. But, as matters could not now be remedied, the Colonial Premiers, one and all, agreed to share jointly the expenses of the Protectorate, and the Premier of New South Wales, in addition, offered the use of H.M.C.S. "Wolverene," then stationed in Sydney Harbour, for a six months' service on the New Guinea coast. This offer the Commissioner gladly accepted; but just then, as it happened, reports were raised of an impending rupture of friendly relations between Great Britain and Russia, and the "Wolverene" would, in case of that event occurring, be required for purposes of local defence. Instead of continuing his efforts to procure another vessel, Sir Peter Scratchley devoted his attention to the condition of the colonial defences, most of which had been constructed under his own supervision. Happily, the Russian scare speedily subsided, and tenders were called for from shipowners possessing a vessel suitable for the New Guinea service. The tender of the Australasian Steam Navigation Company, for the use of the S.S. "Governor Blackall," was accepted, this vessel lying then in Sydney Harbour, undergoing repairs and refitting.

04. "The Start." Sir Peter Scratchley, his Staff and Party of Friends, S.S.

"Governor Blackall"

By the end of July, 1885, everything was in readiness for a start; but another fortnight's delay occurred through the sudden illness of the Commissioner. His health restored, Sir Peter Scratchley gave orders to Captain Lake to have steam up and all ready for the voyage by half-past eight on the morning of Saturday, 15th August. It was with no little joy and pride that I shipped my personal baggage and apparatus, and enrolled myself as a member of the Expedition. It seemed to me that a goal I had long been striving to reach was now in sight, and that I was fortunate enough not only to obtain exceptional facilities for seeing a country whose physical peculiarities, and the manners and customs of whose inhabitants had hitherto been little known and imperfectly described, but to be the humble means of communicating truthful information to others. A large party of friends came on board to take a farewell breakfast, and to accompany us down the beautiful harbour. We rounded H.M.S. "Nelson," and the band on board that vessel struck up "Auld Lang Syne" by way of parting salute. A number of small steamers were conveying the men garrisoned in the various forts and batterie to a grand review that was to come off that day, and the men, as they passed our vessel, greeted us with hearty cheers. A little past Bradley's Head our Captain slackened speed to allow Lady Scratchley and her children to be taken on board the launch "Gladys." I could not help noticing that the parting between the Commissioner and his wife and eldest daughter was touched with pathos and solemnity, as if they all felt deeply that the enterprise in which the husband and father was engaged was not wholly free from serious risks and dangers. Alas! it was their final parting on earth. The younger members of the Commissioner's family, however, entertained no misgivings. With the happy carelessness of childhood, they evidently regarded the occasion as only a pleasant holiday, too soon brought to a close. At length the moment for the final leave-takings came; the last affectionate adieux were exchanged, the last tearful embraces were given and taken, the last good wishes were spoken; the visitors were conducted on board the "Gladys;" and, with waving of white handkerchiefs and many unspoken prayers for a prosperous voyage and a safe return for the adventurers, they reluctantly turned their faces in the direction of Sydney.

The North Head was passed at 10.40, and, steering her course North by East, our gallant little vessel fairly entered on her mission, with a fair westerly wind, a smooth sea, and weather of the true Australian mildness and brilliancy. Broken Bay was speedily left behind us, and next Newcastle, famed for its coal mines. As the sun was sinking below the horizon we found ourselves abreast of the Port Stephens Lighthouse. The wind had freshened considerably during the afternoon, so as to spoil the appetites of some of our party, who had not yet found their sea-legs; the carpenter was battening down the hatches, evidently in anticipation of a squally night, and the company generally betook themselves to the horizontal position in their berths at an early hour of the evening. Happily, the fears of a coming storm were not realised. About midnight the wind fell, and the adventurers slept as calmly in their bunks as if they had been in a palatial hotel on shore.

Sunday morning dawned with Sabbath stillness and brightness. After breakfast the Commissioner issued orders for a general muster at half-past ten. The hour appointed found every man not actually engaged on duty ranged on the quarter-deck; the roll was called, and the Captain announced that Divine Service would be held at eleven, that attendance was not compulsory, but that the Commissioner would be pleased to see every man in attendance. Punctually at eleven the bell tolled for prayers; the crew, to a man, came up on deck, the ship then going at half-speed; prayer books and hymn books were handed round, and then the Commissioner read with great solemnity the beautiful service of the Church of England for those at sea, Mr. Fort leading in the reading of the responses. The singing of the 166th hymn, in which the whole of the little congregation heartily joined, concluded this very impressive service, and every one of the worshippers seemed to feel that he had performed an act of devout thankfulness to Almighty God for vouchsafing so happy a start and such fair prospects to our expedition.

Once more the engines were put at full speed, and with a light wind and a calm sea our vessel went joyfully skimming over the deep. Smoky Cape and Trial Bay were passed before noon; the lighthouse tower on South Solitary hove in sight; the S.S. "Birksgate" passed us on our way southward; several smaller sailing craft were sighted, and one of them, a three-masted schooner, passed so close under our bows that we could read her name—the "Sarsfield"—with the naked eye.

Next day we breasted the Clarence Peak, a well-known landmark, at 4.15 p.m.; and passed the Clarence River Heads at 5.30. After dinner we discerned the lights of the camp-fires of the Custom House officers guarding the wreck of the "Cahors," wrecked a few days before on Evans Reef, and the red light at the Richmond River Heads showed out just as the company were "turning in." During the night the mouths of the Tweed and Brunswick rivers were passed; Cape Byron, the most easterly point of Australia, was rounded, and our vessel kept thenceforward a more northerly course. The next point passed was the southern entrance to Moreton Bay, which—it is a pity to record—has of late years become shallower and unsafe for vessels of any size. Moreton Island, a sandy, sterile-looking spot, was passed on the left, and at 9.45 a.m. we breasted the lighthouse situated on the highest part of the island. Entering the mouth of the Brisbane River, the harbour-master's steam-launch conveyed on board Mr. Romilly, the Deputy Commissioner, and Mr. Chester, police-magistrate at Somerset and Thursday Island, who had the honour of hoisting the British flag at Port Moresby and taking possession of New Guinea in the name of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. Next appeared H.M.S. "Gayndah," which had been specially constructed for the defence of the Port, to escort us up the river, and at 2 p.m. the "Governor Blackall" cast anchor opposite the Government Domain.

At this point in our narrative it may not be unfitting to give the reader a description of our gallant ship and the appointments made for the expedition. The trial trip in Sydney Harbour was thus described in the "Sydney Morning Herald" of 7th August:—

"About two months ago Her Majesty's High Commissioner for New Guinea, Sir Peter Scratchley, chartered the A. S. N. Company's steamer 'Governor Blackall,' in which to visit the different parts of the new colony over which he has been appointed to act as the Queen's representative; and on her arrival in Sydney she was taken over to the Company's works, and altered and improved in her internal fittings to such an extent as to give her the appearance of a new ship. Yesterday the steamer was taken for a trial trip, and the result was regarded as in every way highly satisfactory. She cast off from the A.S.N. Company's wharf at about a quarter to eleven, and proceeded down the harbour and outside the Heads for a distance of several miles, the speed attained when covering the measured mile being equal to eleven knots per hour. As the day was beautifully fine, with a gentle 'north-easter,' the trip was greatly enjoyed by the company present, among whom were Messrs. Cruickshank (chief Government engineer-surveyor), A. B. Portus (superintendent of dredges), Gray (Mort's Dock), Captain Vine Hall, Dr. Glanville, and others.

"There was but one opinion among the the company as to the suitability of the steamer for the work in which she is to be engaged, also in reference to the exceedingly comfortable, even luxurious manner in which she has been fitted out. The 'Governor Blackall' is a most attractive looking vessel of 487 tons gross register, and was built from designs supplied by Mr. Norman Selfe by Mort's Dock and Engineering Company, in 1871, to the order of the Queensland Government, who employed her for some years in conveying the mails along the coast of that colony. She then came into the possession of the Australasian Steam Navigation Company, and has been running in the coastal trade of Queensland ever since. About five years ago the Company went to the expense of providing her with new engines and boilers, which, with the other parts of the ship, have been carefully overhauled and put in first class order, so that yesterday the machinery worked very smoothly and without the slightest hitch of any kind. On the 1st of July last the "Governor Blackall" was placed in the hands of Mr. Cruickshank to superintend the necessary alterations and repairs, and he has carried out his work in a very creditable manner. The hull of the vessel, both inside and out, has been chipped, cleaned, and painted, the paint outside being white, which certainly adds to the attractiveness of the vessel's appearance. The old fittings in the saloon have been removed, and the apartment has been entirely re-arranged to suit the requirements of the expedition. State rooms running its entire length have been erected, with ample room ventilation, and light for every member of the expedition; and the dining-table, with swing trays overhead, runs down the centre. On the right of the companion leading to the saloon is the apartment, formerly the ladies' cabin, to be used by Sir Peter Scratchley as a bed and sitting-room, which is fitted up in most complete style, and with a considerable display of taste in the furnishings, &c. Each of the officers has a separate cabin, and in addition one has been set apart specially for the use of Mr. Lindt, the photographer to the expedition, who has over 400 plates with him, and who intends to take views of New Guinea to be sent home to the exhibition to be held in London next year. Then Dr. Glanville has a room, in addition to his private cabin, for the dispensary. There is a bath-room for the use of the general, and another for the officers, and in each hot, cold, and shower-baths may be had at any moment, the cold water coming from a tank on the bridge, from which the whole ship is supplied, and the hot from the boiler. All the furniture in the cabins is quite new, and made of beautifully polished cedar, thus adding greatly to the general effect. The fore cabin has also been altered and improved and the petty officers and men will find most comfortable quarters therein. The ventilation of the vessel has been carefully studied, and a system has been adopted which has so far been an undoubted success, and in the trying climate of New Guinea should prove a boon to all on board. The ventilating machinery is driven by a separate engine, to which is attached a large and powerful exhaust fan, which draws out the heated air from all parts of the ship most effectually. There is a large pipe, six inches in diameter, extending from one end of the ship to the other. This is slung from the roof in the saloon and in it there are airslits at intervals, which can be opened and shut at pleasure. As the heated or foul air rises it is drawn into these orifices, and then through the pipe till it is sent overboard. The steam-engine will only be required to work the system when the vessel is at anchor in the harbour, as when she is at sea the pipe is connected with the funnel, and an effective 'up-cast' shaft is thus created. Two of Kircaldy's patent condensers for condensing fresh water are placed on the bridge, and on trial proved wonderfully effective, over 1,000 gallons being obtained from them in one day. They occupy but little room, and should prove invaluable to the expedition. They were the only two in Sydney, and Mr. Cruickshank obtained them as a special favour from Mr. Wildridge, the Superintendent of the E. and A.S.S. Company. The next noticeable addition to the resources of the ship is one of Oscar Kroff's ice-making machines, which has been tried and has been found to work well, turning out fifteen pounds of ice every four hours. One of Sir William Thompson's sounding machines has also been supplied to the 'Blackall,' and in the coral seas it should be of great service. Yesterday it was tried under the supervision of the local agent, Captain Vine Hall, and acted most efficiently, telling the depth of water off the heads very accurately. In addition to every requisite in a general way for the expedition, the steamer has been provided with a complete set of spare gear in the engine-room, and an ample supply of stores; also with a smart little steam-launch, which should prove useful for a variety of purposes, especially for ascending shallow rivers, &c.; a Gatling gun, with a stand of small arms, including Winchester and Martini-Henri rifles, and revolvers, and about 6,000 rounds of ammunition; and double awnings fore and aft. What was formerly the commander's room aft has been fitted up in a very inviting way as an extra room for General Scratchley. The 'Governor Blackall' has been placed under the command of Captain T. A. Lake, one of the most valued officers in the Company's service, and there is every likelihood that under his careful and skilful supervision the steamer will wend her way safely through the dangers which surround the navigation of the coast of New Guinea. After the steamer returned to the harbour she brought up in Farm Cove, where she will remain until she leaves for her destination. She will call at Brisbane, Townsville, and Cooktown, en route to New Guinea, probably staying a couple of days at each place."

From this description it will be seen that no expense was spared (as was fitting) in adapting our vessel to the requirements of the expedition. With a laudable purpose of lightening by innocent amusement the monotonous duties of the seamen, and enlivening the spirits of the company generally, the Commissioner, whilst in Brisbane, purchased a handsome stock of musical instruments—concertinas, flutes, banjos, bones, &c.—suitable for what, in the language of the music halls, is called a "variety entertainment." Those of the party who were musically inclined no doubt anticipated much pleasant recreation from this new acquisition; but it may, perhaps, be doubted whether, on the whole, the amateur performers themselves do not win larger delight from these performances than the average of their auditors. Another provident purchase was a set of oil-skin suits for the use of the crew; but when, on the second day after our leaving Brisbane, the cases containing the waterproof gear was opened, it was found that most of the suits were rotten and quite useless. They were of all colours, from lemon yellow to Vandyke brown, and looked very much as if they had been bought by the vendors as salvage stock from a great fire in the warehouse. No doubt the clever fellows thought that they had done a very smart stroke of business in thus disposing of a case of worthless and damaged goods at the price of sound and serviceable articles; but the Commissioner had the bad goods carefully repacked, and re-shipped from Townsville to the too clever vendors.

Whilst at Brisbane, our vessel was constantly beset by sight-seeing citizens, and our party equally so with "interviewing" reporters. The visitors were treated with uniform courtesy, and they all appeared to be very much pleased with the arrangements. Here the party was joined by Mr. H. O. Forbes, the eminent naturalist. His instruments had been damaged at Batavia, through an accident that sunk the lighter conveying his luggage, and he had come on to Brisbane to get them repaired. On our starting, Mr. Forbes left behind him, to follow by the next steamer, his Malay servant and Amboynese hunters. He spoke to me very highly of these dusky retainers as being faithful and affectionate; some of them were in tears at their master temporarily leaving them. This testimony I am able to corroborate from my own experience; I have found both the Malays and the Sundanese as servants industrious and obedient, and so long as they are kept in their native tropical climate they are hardy and enduring; but they cannot stand the cold, and what to an English constitution is pleasant and bracing weather is to them severe suffering and complete collapse.

We left Brisbane on the 20th, at 3 p.m., the Commissioner having finished his inspection of the fortifications. Mr. Romilly, the Deputy Commissioner, embarked with us. He was limping a little, as I noticed, from a slightly lamed foot. Our vessel was laden rather above the Plimsol standard, in consequence of the quantity of coal and luggage taken on board at the city; but as this was a defect that time would remedy, not much notice was taken of the circumstance. It told materially, nevertheless, against the comfort of the voyagers throughout the stormy night that followed, the ship rolling heavily in a swell from the eastward. At nine on the morning of the 21st we passed Sandy Cape.

The Captain had fitted up one of Walker's Patent Taffrail Logs, to test its accuracy. The instrument was not altogether a success; the distance from Sandy Cape to Lady Elliot Island is seventy-two nautical miles, and the dial of the Patent Log showed only sixty-three miles. Captain Lake ascribed the discrepancy to the use of an unsuitable line carrying the fan, or propeller, of the log, which error he proposed to rectify upon a second trial.

Lady Elliot Island was passed about six in the afternoon. This place is merely a low stretch of coral reef, standing only a few feet above the water level; but it bears a lighthouse, and it is of some importance geographically, as indicating the commencement of the Great Barrier Reef. A showery day, with a rather rough sea on, was followed by a bright and tranquil evening, so that we looked forward to enjoying a quiet dinner and a calm night afterwards. This anticipation, happily, was not disappointed.

On passing Percy Island No. 1 in the afternoon of the next day, the 22nd, Captain Lake mentioned that he knew the place well from a tragic incident that occurred there within his own knowledge. The captain has spent all his naval life on these coasts, and in the year 1854—some time before the separation of Queensland from New South Wales—the Government of Sydney sent out an expedition to make explorations along that portion of the territory. The party started from Brisbane in a cutter named the "Percy," and after making an inspection of various islands they came upon the one that was now in sight. As the place presented an inviting appearance, they all landed to make researches, with the exception of four men, who formed the crew of the little vessel. But they never returned, every one of them being murdered by the blacks. The geologist of the party, Mr. Strange, was a personal friend of our captain's, and the sad catastrophe was therefore stamped indelibly upon his memory. The island bears the name of the cutter, and the recollection of the tragedy is thus perpetuated.

A second trial of the taffrail log already mentioned was made on the 23rd, with much more satisfactory results. The instrument rings a bell every quarter of a mile traversed, and is self registering up to one hundred miles. Then the time is taken, and the same process is repeated, the instrument requiring no attention save oiling a couple of times a day.

We noticed here a peculiar yellowish scum spread over the surface of the ocean. Upon inquiring of our skipper what the substance was, he told me that seamen suppose it to be the spawn of the coral insect. Sometimes it is met with in such large quantities that a landsman would think that the vessel was running on a sandbank. The substance, whatever it may be, makes its appearance in these waters about the beginning of August, and is rarely seen later than December.

At 4 p.m. we passed Percy Island No 2, or rather, two islands divided from one another by a narrow strait. Seen under the tinted lights of a brilliant sunset, the place looks as lovely to the eye as Prosperos' enchanted island. The sky was covered with those aerial "woolpacks" which the trade winds always bring with them, and the soft shadows of the silvery clouds flecked the green hillsides of the happy land. There is abundance of timber, pine, and grazing ground sufficient for a few thousand sheep in all seasons. An inlet runs up to a perfectly sheltered basin, navigable for small craft. Our second engineer had once been driven upon this island through stress of weather, and going ashore, he found a fine lake of fresh water, with unlimited fishing and shooting privileges for whomsoever chose to claim them. Two or three European settlers vegetate in calm contentment in this ideal island-pastoral solitude.

Pine island is the name of the adjacent small territory, and is so called from the immense quantity of white-stemmed pine, growing right up to the summit of the highest hills, which it contains. A lighthouse has recently been erected here, and the cottage of the keeper, standing amidst a grove of tall graceful pines, looks to the distant observer a charmingly romantic habitation for a sentimental hermit. Whilst we were gazing at the house through our glasses we caught sight of the lighthouse-keeper's wife walking up and down in the verandah, with her baby in her arms. We waved our handkerchiefs by way of kindly greeting, and the good woman, handing the baby to her husband, re-turned our salute. On the side of the island which fronts the continent the cliff is extremely steep, the rise and fall of the tide being fully twenty feet. To draw up the building materials and stores from the landing-place on the beach the aid of an iron-wire tramway is required.

I could not help thinking that this group of islands would be a most delightful place to spend a summer holiday. Access to the place could easily be obtained by means of a boat from the Australian Steam Navigation Company's vessel. The islands are well sheltered, game is abundant, and the climate is simply perfection; what other element of holiday enjoyment is needed? One of the settlers would, no doubt, readily lend his services to the party of excursionists, and what glorious campings out they would have! One of the group is named Sphinx Island, from a fanciful idea of its resemblance in shape to the fabled monster of the Egyptians.

During the night our skipper was busily engaged superintending the navigation of the vessel through Whit-Sunday Passage, a narrow strait running through an almost bewildering maze of islands. This passage is counted the most beautiful spot in the whole extent of the Queensland coast. We cleared the passage at six in the morning, so that we just missed feasting our eyes on the varied loveliness of this romantic archipelago. Ever since passing Lady Elliot Island we have had perfectly calm seas and Italian skies; the vessel skims along the surface of the unruffled waves like a sea-bird; and one happy result of these favourable conditions is that not a soul amongst the party is now absent from the table at meal times.

Cape Upstart and Cape Bowling Green stand closely adjacent to one another, both named from their peculiar aspects. The one rises abruptly from the sea to a height of more than 1,000 feet; the other lies flat with the sea-level. A vessel might very easily run aground at the latter spot, as the captain of the S.S. "Gunga" found to his cost a few months ago, when he got stranded there. The casualty occurred in broad daylight, and so simply, that the wife of the lighthouse keeper, standing only a few yards inland, waved her apron to warn the skipper of his danger.

Late in the evening we entered Cleveland Bay, and dropped anchor in the open roadstead, about two miles from shore. Townsville stands upon the beach, on both sides of Ross's Creek, and high hills, rising abruptly, enclose it all round. I had learned from the Brisbane papers that "The Vagabond" was abroad in Northern Queensland, and next morning, upon landing, I encountered this particular eye of the "Melbourne Argus," looking as fresh and jolly as ever. By Mr. Julian Thomas I was introduced to Mr. Gulliver, of Acacia Vale, who received me very hospitably, and lent me the manuscript diary of Mr. Edelfeld, who had been employed by him in collecting botanical specimens in New Guinea. From the perusal of this record I gained much valuable information. Here a small flock of about fifty sheep were bought for the use of the expedition, the survivors of the voyage amongst the lot being reserved for pasturage at the mission station at Port Moresby. Amongst our visitors whilst at Townsville were Captain Sandeman and his amiable wife, who took a farewell dinner with us, and then returned home in their smart steam launch.

We left Townsville at 10 p.m. on the 24th, and next day at noon were abreast of the Johnston River, the scenery along the banks of which was described to me by "The Vagabond" as being more beautiful than anything he had ever seen, with the exception of the wizard Fijian streams.

Cooktown was reached at 9 a.m. of the 26th. The wharf here is situated at the base of a steep hill, on the top of which stands the signalling station at an elevation of about 500 feet. As the cliff intercepts the cool south-east breezes, we began to experience, while lying here, the true tropical heat, the thermometer in the saloon rising to 80°. So steep is the hill, that when the dwelling of the company's agent was being built, it was necessary to make an excavation in the side, in order to lay the foundations. The situation of the house exposes it to the danger of inundation from the tropical rains, but in the dry season the fresh water required for domestic purposes has to be carried up the steep ascent. On the opposite bank of the Endeavour River rises the volcanic pile, Mount Sanders, its rugged slopes deeply scarred and worn by the rains of many centuries. Cooktown wears a straggling and stagnant appearance, in this respect contrasting strongly with Townsville. As is usual with all the towns in Northern Queensland, galvanised corrugated iron is here the universal building material, being so useful as a rain-catching roofing. Walking through the town I noticed a good hospital (built on a principle that suits it to a tropical climate) and several churches and schools. At the girls' school the children were being taught their lessons on the shady side of the building under the verandah. Their appearance struck me as being particularly neat and tidy. I took two photographic views of the town, one of them from the summit of the hill, taking in the mangrove swamps of the Lower Endeavour River. The missionary schooner, the "Ellangowan," a very well-fitted and smart-looking craft, lay at the wharf next to our vessel, and H.M.S. "Raven" was moored a little way up the river, which is navigable for a short distance for smaller craft. Chinese abound in Cooktown, and very valuable residents they are, as they are the sole cultivators of fruit and vegetables. Scores of aboriginals were strolling about the town, and they afforded us some amusement by the expertness with which they dived into the river for coins. At about midnight our last visitor from Cooktown, Mr. Milman, who had been spending the evening with the Commissioner, left us, and the stragglers of our own party being all brought on board, the tide serving, we weighed anchor at 1 a.m. of the 27th, and so bade adieu to the last civilized settlement we should see until our return from the newly-acquired territory.

At daybreak Cape Flattery was passed, and, about 7 o'clock, Lizard Island, where a few years ago a party of bêche-de-mer gatherers were murdered by the blacks. This incident was rendered memorable by a peculiarly tragic circumstance. Mrs. Wilson, the wife of one of the party, had accompanied her husband on the expedition. With her baby at her breast, she contrived to escape from the massacre, and accompanied by the Chinese cook to the party, put to sea in a ship's tank, in the hope of saving their lives. The poor fugitives drifted on to an island in the Howitt group, about forty miles to leeward, and there perished from want of water. The son of our skipper, happening to touch at this spot some months afterwards, found the skeletons of the poor mother and her babe lying on the beach, and that of the Chinaman a little way off. Beside the bleached remains of the mother lay a scrap of paper, upon which she had contrived to scribble, in the midst of her prolonged agony, a rough diary of the adventures and sufferings of herself and her companion. What unrecorded tragedies these sunlit ocean regions have witnessed!

Clearing Lizard Passage, and keeping the largest island of the Lizard group right astern, we steered straight for the mile-and-a-half opening in the Great Barrier Reef. Our skipper here mounted to the fore-cross-trees, to keep sharp observation of our course; nor was the precaution needless, for on both sides of our little craft we could plainly discern the long waves breaking heavily into foam on the coral reefs. Skilful piloting carried us safely through all dangers; and, the Barrier Reefs once cleared, our vessel ploughed securely the deep waters of the open Pacific, heaving into billows under the influence of the south-east trade winds.

A favourable run of thirty-six hours further brought us within sight of the shores of the island of our destination.

First View of Papua—Breakers Ahead—Haven of Safety reached—First Welcome—The Missionary and his Wife—Excursion to Rano Falls planned—Native Villages on the Littoral—Frolicsome Young Savages—A Degraded Race—A tribe of potters—A Strange Flotilla—Preparations for Excursion—A Christian Salbath in a Savage Land—Elevating Influence of Christianity—A Photographer's Impedimenta—First Landing—Religious Service in the Motu Language—"Granny" the Prime Minister—A Start resolved on—A Guide and Carriers engaged—Also a Native Head Cook

The south-east trade winds were blowing when we first sighted the shores of New Guinea; and as, during their prevalence, a mist more or less dense hangs about the mountain tops, we caught only a short glimpse of the towering heights of the magnificent Owen Stanley Ranges. About noon the low-lying lands of the fore-shore came distinctly into view. Stationed at his post of observation on the fore-crosstrees, our skilful commander gave forth his directions for steering the little craft securely through the labyrinth of coral reefs. Abreast of Fisherman Island we could clearly discern the breakers flashing and foaming on the shallows, and at one time we seemed to be in the very midst of them. At this moment our course was easterly, and dead in the face of the heavy swell of the ocean. Although our prudent skipper slackened speed by a full half, before we had passed the narrows abreast of Pyramid Point the waves dashed in glittering cascades over our bows continuously for about an hour. It was a very wonderful sight to observe the beautiful rainbows woven by the dazzling sun-rays upon the mounting and falling sprays, each in succession appearing and vanishing with the speed of light. At length Paga Point was passed, we were in smooth water, and our vessel came to anchor in the land-locked harbour of Port Moresby. We had reached our destination.

05. Loading Lakatoi, Port Moresby — Women making Pottery

Our position was about a mile from the Mission Station, and close by us lay anchored H.M. Surveying Ship the "Lark." The time being about 3 o'clock in the afternoon, it was decided that none of the party should go ashore till next morning. Speedily there came to welcome us Mr. Musgrave, Assistant Deputy Commissioner, and Mr. Frank Lawes, eldest son of the missionary. News was mutually exchanged, and Mr. Musgrave stayed to dine with the Commissioner. Next morning our feet trod for the first time the soil of New Guinea, and we had a very cordial welcome from the missionary and his amiable wife. Arrangements were made by the Commissioner for an excursion on the following Monday up the Laloki River, as far as the Rano Falls, the photographer being in charge of the party. Then we took a first look at the native villages standing close by the shore. They reminded us somewhat of those ancient cranoges, or lake dwellings, once common in Scotland, Ireland, and various parts of Continental Europe. Built upon mangrove stakes, planted something below low-water mark, each hut is connected by a sort of rude bridge with the shelly beach. Troops of naked Papuan children, some so young as to be barely able to stand on their tiny limbs, frolicked fearlessly about the ricketty stages upon which the huts stood. They had evidently no apprehension of danger from falling overboard. We could imagine the feelings of a civilized mother at seeing her offspring diverting themselves in such a situation: the savage matrons appeared to regard the scene with the tranquil satisfaction of a motherly old duck which sees her young brood taking for the first time to the water! The natives hereabouts are an indolent and filthy race, many of them being disfigured by ugly sores on their faces and bodies—the effects of bad and insufficient food, combined with carelessness of the primary laws of health. This foul disease is, however, not contagious; if it were so, the whole race would speedily perish of scorbutic and scrofulous epidemics.

06. Lakatoi, or Motu Trading Vessel, under Sail