a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

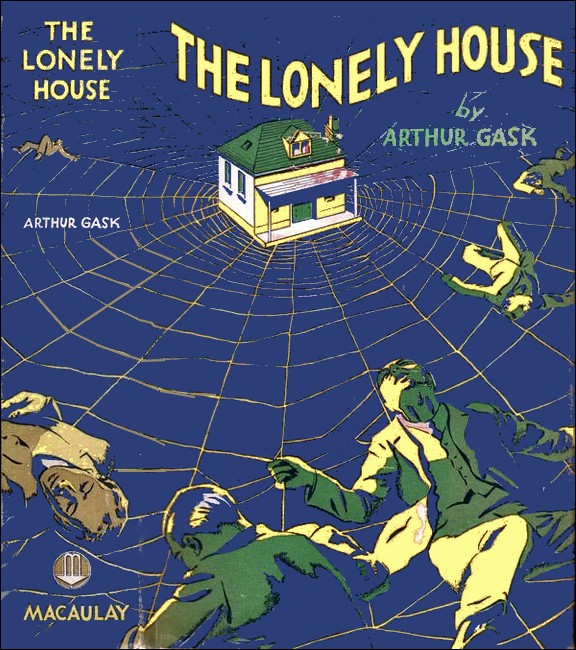

Title: The Lonely House Author: Arthur Gask * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1000851h.html Language: English Date first posted: Dec 2010 Most recent update: Feb 2021 This eBook was produced by Maurie Mulcahy, Colin Choat and Roy Glashan. Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html To contact Project Gutenberg of Australia go to http://gutenberg.net.au

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

"The Lonely House," Herbert Jenkins Ltd., London, 1929

"The Lonely House," Macaulay Company, New York, 1931

A story full of excitement and interest will

begin in "The Advertiser" on Tuesday next. It is written by

Arthur Gask, a resident of Adelaide, who has gained a reputation

with English publishers as a writer of first-class mystery

stories. The scene or the plot is in South Australia. It is a

more than usually absorbing story, and in addition to its appeal

as detec-tive fiction it has a strong love interest. Don't miss

the first instalment next Tuesday.

THE detective had been watching for four days before he realised suddenly that the house was inhabited.

It was a sinister-looking house that stood alone upon a lonely shore in South Australia, and it lay by the margin of the waves in a little sandy cove between the dip of two high hills.

It was a place where few men came, for it was cut off from the distant townships by long, barren wastes of rock-strewn land.

There were no roads nor tracks within many miles of it, and its only highway was the dark and restless sea, forever teased and fretted by the winds that blew across the gulf.

And for four whole days he had watched it through his binoculars from the cliff less than two hundred yards away, and the whole time there had been no suggestion about it of any life within.

It was a silent house, as still and silent as the grave.

Its door had never opened, he had seen no faces from its window and no smoke had ever issued from its chimneys—yet in the falling light of dusk that evening it had flashed to him, as lightning flashes through the blackness of a midnight sky, that human beings were in hiding there.

And their hiding had been the closer because they had seen him watching.

Then they were evil-doers—they were creatures of crime.

Exactly a week previously, and on a beautiful summer's evening

towards dusk, Gilbert Larose, the best known of all the

detectives of the great Commonwealth of Australia, was crouching

down behind a small bush high up upon the sides of Mount Lofty,

watching with an annoyed and frowning face four men who were

climbing slowly up the slope towards him.

They were only about two hundred yards away, and through his binoculars he could discern plainly the expressions upon their faces. They looked alert and eager, as if they had some particular and important business on hand.

They were sturdy, thick-set men, and were all armed with stout sticks. They walked spread out, fanwise, with about ten yards between them, and they peered intently into all the bushes as they passed.

"Now if it were not impossible," muttered the detective slowly, "if it were not impossible, I would swear that they were looking for me." He nodded his head. "Yes, and they'll find me, too. I ought never to have camped with that cliff behind me. It serves me right." He glanced round quickly in every direction.

"Ah!" he ejaculated, "but that rock might save me yet, if only I could get there first."

He dropped sharply on to his hands and knees and rapidly, but with extreme caution, began to crawl towards a small rock about a hundred yards away.

"I may be able to dodge them there," he went on, "and, another chance too, they mayn't have noticed my bicycle. But what a fool I've been!"

Suddenly then he heard a shout from one of the men. "They've seen me!" exclaimed the detective disgustedly. "I knew I'd left it until too late."

But he was mistaken.

"Hell! here's a snake," called out a voice excitedly, "a big death-adder. Look out, you fellows—it'll be the very place for them here."

"Kill him." shouted someone else. "Don't run behind, you idiot! He may spring back. Hit him from the side."

There was a lot of noise, a chorus of shouting, and then the detective heard an exultant cry.

"Got him! In the middle of the back, just as he was going to turn on me too."

The detective stopped crawling, and looked round. The four men were all close together now, and bending over the ground. There was an animated discussion for a couple of minutes, and then one of them straightened himself up and gave a long look round.

"Well. I'm tired of this," he announced emphatically, "we've come quite far enough, and I'm going back on the road. I'm thirsty, and we shall be too late to get a drink if we're not quick."

There was some talking amongst the other men, and then, apparently being all in agreement, off they went at right angles to the way they had previously come.

Smiling in his relief, Larose watched them disappear, and then, after a long scrutiny to make sure that the coast was quite clear, he walked down to where they had been standing.

He found the death-adder they had killed, all fouled over now in blood and dust. The body was still quivering, and picking it up carefully, he examined the evil-looking head. He pulled the jaws wide open, and exposed the dreadful poison fangs. "Horrible," he exclaimed with a shudder. "What agonies of death lay in those little fangs! But why had it to die?" He sat down upon a bank, and with a handful of leaves, almost reverently wiped clear the body from its stains. "Yes, it is beautiful," he went on admiringly, "beautiful in its dreadful way. Its coloring and its symmetry are perfect, but I wonder—"

He paused suddenly, for out of the corner of his eye he had seen something moving among a heap of stones close by. He kept perfectly still, and a moment later a second adder glided into the open, and, raising its head off the ground, swayed itself gently from side to side.

"Evil to evil," whispered Larose very softly—"the way of the world for all time."

He reached stealthily for a piece of rock that lay near to him, and then, rising sharply to his feet, he hurled it on to the snake. The rock dropped squarely on the reptile and broke its back. It writhed viciously, but he picked up a big stone and quickly put it out of misery by battering in its head.

"His wife probably or perhaps her husband," he remarked with a sigh, "but it was best it should be so. Violence always for the enemies of the world. A stick or a stone for those that creep and crawl and then, as we get higher up, the lash, the prison, and the rope for humankind. Mercy's a mistake with evildoers. The community must protect itself." He sighed again. "And that is why such men as I have their work."

He walked back up the slope and then a thought struck him.

"But what were those men doing here?" he asked frowningly. "They couldn't have come here after rabbits, for they had no guns. What were they looking for?" He answered his own question. "Sheep probably. They have lost some sheep." He shrugged his shoulders. "Well, they won't disturb me again. I'll be off to- night. I was tired already of this place, and I feel much stronger now. Yes, I'll start for Cape Jervis, and I ought to do the seventy miles in two nights and a day."

The detective was on holiday in South Australia, but the vacation was neither of his choice nor making. It had been forced upon him by the incidence of a serious illness.

Bearing a charmed life among the desperate class in which he moved, and apparently immune always to the dangers that threatened him in pursuit of his calling, he had nevertheless fallen an easy prey to the minute typhoid bacilli, and for days had hovered between life and death. Then, convalescence supervening, he had been, ordered away for a complete rest, and Adelaide had been chosen for him as being a city least likely to remind him of his work. Adelaide was so quiet and peaceful, he had been assured. Adelaide was so law-abiding, and so rarely there did Crime lift up its baleful head.

So to South Australia, he had come, expecting to be intensely bored and wondering gloomily how he would be able to fill in his time.

Then suddenly an idea had seized him just as the train was running down through the hills into Adelaide, and he had laughed happily at the very thought of it. It was a strange and extraordinary idea, but it would provide him, he was sure, with an interesting holiday after all.

There should be no wearying hotel life for him, he told himself, no monotonous days passed in seeing the sights, no bored waiting for the holiday to end.

He knew what he would do. He would become a boy again and play at hide-and-seek. He would play a game of make-believe. He would hide himself away from everyone as if it were a matter of life or death.

He would imagine that he was an escaped convict, and would see if it were possible for him to live undiscovered and unseen in South Australia for six weeks. He would pretend that everyone was looking for him and that he himself, for once, was pitted against the law.

He would secrete himself away among the hills, in the bush upon the mountain sides, or in the lonely places on the sea-board where no one ever came.

Yes, he would creep like a phantom over South Australia, and the winning of the game would be—that no one should have set eyes on him until the time was up.

The whole adventure would be of absorbing interest, and the quietness and the solitude would be the very things that he was needing to rest his nerves.

It was typical always of Larose to make up his mind quickly, and so directly his train had drawn into the railway-station in Adelaide—he had at once set about putting his ideas into execution.

Taking only a few things from his luggage, he had left his trunk in the station cloak-room, and had then proceeded into the city to make some purchases.

He had bought a bicycle, a small camping outfit and the least quantity of provisions that he thought he would be able to make do with. A good fisherman and no mean expert in the trapping of small game, he reckoned that once well away from the city he would be easily able to provide himself with food.

He had had one good meal at the Australasian Hotel, and then in the failing light of the dusk he had slipped furtively into the Adelaide hills, and like a shadow the darkness had swallowed him up.

For seven nights and six days he had lain hidden on Mount Lofty, and, until the episode of the death-adders, no one had come near him or disturbed him.

He had made his bivouac at the base of a stretch of grey cliff near the summit. He had chosen the place there because he could light a fire and the smoke could not be seen against the color of the cliff behind him, and also because from his elevated position he could enjoy such a magnificent panorama of the wide Adelaide plains, and the miles upon miles of waving trees below.

As he had promised, he had given himself an easy restful time.

By night, he had slept the long deep slumbers of a man who was convalescing from a serious illness, and by day he had basked idly in the sun, watching a sub-conscious and disinterested sort of way the comings and goings of the great city that lay outstretched beneath him.

As the crow flies he was quite close to Adelaide, and a bare seven miles almost would have taken him into the very heart of the city itself. Through his glasses he could see plainly the trams and motors gliding through the streets and the people moving about like ants. Also, when the wind was favorable, he could hear the hourly chimes from the big clock on the Post Office opposite the Town Hall.

For four days and nights life had been quite uneventful, all peace and quiet and rest, and then on the evening of the fifth day something had happened, and henceforward a jarring note had been struck in the otherwise perfect harmony of these beautiful trees and hills.

He sensed somehow that something unusual was happening about him.

Nothing indeed that occasioned him much interest, and nothing that moved him even to speculate over-much as to its cause, but still—he felt that things were now in some subtle way different from what they had been before.

He noticed for one thing that there seemed to be more people than usual moving on the roads that led to the hills, not people in motors, but horsemen and people on foot. They seemed to hang about more, too, to be longer in view, and to be from time to time talking in groups.

Then after dark he thought the lights were kept burning much later in the scattered homes among the hills and upon two nights he had finally dropped off to sleep with some of them still shining. Also at dusk once, when he had been creeping as usual to the spring for water, a dog somewhere had heard him and barked, and immediately three men had rushed out of a nearby homestead, and for quite a long while had stood staring round in every direction. About this last episode the detective had been greatly annoyed, for it had made him about an hour late in filling his can.

So had things been up to that last night when, shortly after eleven o'clock he again took to the road.

He had provided himself with a map of South Australia, and he had a good idea of the lie of the land. It was his intention to make for a lonely stretch of coast near Cape Jervis, a part apparently untouched by roads or tracks in any direction. He reckoned he had about eighty miles to cover, and he was expecting to do it comfortably in the travelling of two nights.

But he soon found he had greatly miscalculated his chance of progress and he was hindered and delayed from the very beginning. Before even he had gone half a mile from his bivouac on Mount Lofty, he had had to lift his bicycle hurriedly off the road and hide himself in the thickets.

Two men had come by very slowly, and he was surprised to notice that, although there was a new moon, they both were carrying lanterns.

A mile farther on and a man was leaning over some fencing, for all the world as if he were waiting for someone, and it was an hour nearly before he finally turned and went into the house that lay close behind. Quite half a dozen times during the night, too, he saw people moving about, and each time he had to wait until the road was clear. Morning found him only about thirty miles from the city and he had to hide during all the day in a clump of trees not three hundred yards from the outlying houses of a small township.

The next night, however, he made a little better progress, but it was not until dawn was breaking on the third day that he found himself at the place for which he had originally set out.

He was then about seven miles off the track that led to the Cape Jervis lighthouse, and for several hours he had seen no signs of human habitation.

He was on a rugged promontory of land that jutted for about half a mile into the sea. On one side the cliff was high and sheer, but on the other side the ground sloped down gently for about three hundred yards to a little sandy cove.

The place was studded everywhere about with big rocks.

"Just what I wanted," sighed the detective wearily. "I shall be all alone here. I can bathe and fish, and there's a creek of fresh water over there." He hastily unpacked his things and then, too tired to think of preparing anything to eat, he spread his ground-sheet by the side of a big rock and, making a pillow of his arm, in a few moments was fast asleep.

He slept heavily until well past high noon, and it was then only the glaring of the hot sun that awoke him.

He stood up, and, gazing interestedly around, was more pleased than ever with his surroundings. He took out his binoculars and swept the coastline in both directions as far as he could see.

"Excellent," he remarked, "I couldn't have found a better place. I can see round everywhere for miles, except for that little dip in the cliff over there. No one will be coming here, and there should be plenty of rabbits and fish. I will have a glorious time. I will rest and sleep. I will worry about nothing. I will start writing my memoirs and the world will then know what a fine fellow I am," and he rubbed his hands gleefully and laughed happily as a boy.

Methodically he proceeded to set up his camp. He lashed his little lean-to tent securely to the rock and with his small mattock dug a deep trench all round, in case it should come on to rain. Then he made himself a neat fireplace with round stones, and gathering some dried twigs together soon had a fire going and was boiling his billy.

"But I must be careful with the water," he said, shaking his head, "until I make sure about that creek over there."

His simple meal over, he set out to explore, and a quarter of a mile away found the creek as he had anticipated.

"Not too much water," he remarked, "but still it doesn't look as if it would dry up before the time comes to leave here. Besides, we may get a shower or two any day."

He had a long bathe off the sandy cove and then, after setting a few rabbit snares, retired to his tent directly it began to get dark. The exertions of the two previous days had tired him much more than he thought.

The following day dawned bright and clear and he was early astir. He found two nice young rabbits in his snares and was very pleased with his good fortune.

"Everything here I could want," he exclaimed happily. "I couldn't wish for anything more." He looked round on every side. "Alone in the great heart of nature. Alone with the sea gulls the sea, the sun, and the sky." He drew in deep breaths of the invigorating air. "Away from the foul breath of the cities, away from the sordid struggles of competing men, away from the black haunts of crime. Why I might be the only man alive in the world now. I don't suppose, year upon year, anyone ever comes here."

He walked meditatively down to the sandy cove and then it struck him suddenly that he had not yet explored down the dip in the other cliffs, the only spot that was not in view from his little tent by the big rock.

"I must go there at once," he smiled whimsically—"it is the only part of my property that I haven't yet seen." Humming lightly to himself and pausing many times to look back and enjoy the view, he climbed up over the other side of the cove. It was a stiff climb and his legs ached when he reached the top.

He sat down upon a rock, and then, his eyes roving with interest around a startled exclamation burst from his lips.

"Hullo!" he exclaimed disappointedly, "why—there's a house, and I shall be seen and lose the game," and immediately he dropped down behind the rock exactly as if he had been shot.

Very cautiously then he peered round.

The cliff in front of him sloped down to another little bay, this time, however, only about two hundred yards distant, and upon the edge of the sands below was perched a small black house.

Viewed through his binoculars, he saw that the house was quite substantially built and was square in shape. There was one large window facing in his direction and at a good height from the ground.

By the side of the house, drawn up high above the sands, lay a good-sized rowing boat.

"Whew," exclaimed the detective disgustedly. "Fishermen! Now, I wonder if they are here now?"

For an hour and longer he lay with his eyes glued to his binoculars, alternatively watching the house and sweeping round upon the cliffs on every side.

But there was no sign of life anywhere except for about a dozen seagulls which patrolled upon the sands before the house in a lively and animated manner. Satisfied at last that at any rate for the time being there was no one near, the detective pocketed his glasses and walked down to investigate closer.

The sea-gull rose up screeching as he approached and it flew to a short distance away, to resume their previous occupation of quarrelling with each other.

The house was shut up and closed by a stout nail-studded door that was securely locked.

"Hum!—an ugly house," muttered the detective, "and built quite a while ago." He smiled to himself. "But there would be no difficulty about that lock, if I were curious. Any bit of old wire would open it."

He walked round the house. It was built solidly of stone, but had a sloping wooden roof. There were no windows to it other than the one he had noticed from the cliff and that, from its position, appeared to provide light only to some kind of upper room, for it was fully twelve feet off the ground.

He stepped back several yards, hoping that from a greater distance he would be able to look into the room, but the glass of the window was almost black with dirt, and be obtained no reward for his pains.

"Funny place," he muttered. "I wonder how often anyone comes here." He sighed. "I shall have to move off again I suppose, but I can wait, at any rate, until someone comes. I'm quite safe. They'll never notice my tent on the other cliff."

He turned round and examined the boat. There were no oars, and everything movable in it had been taken away.

"Now, more than one person comes here," he said meditatively. "One person certainly could push this boat down into the sea, but it would require more than one person of ordinary strength to haul it up on the bank where it is. It looks—hullo! it had a name on it once and it's been scraped off."

He bent down and examined carefully the side of the boat. "Yes," he went on, "and they've been at some pains to blacken the place where they scraped the name away. They had no paint so they heated a piece of iron or something, and then smeared the spot over with tar. Quite recently, too, for it is not caked hard yet." He passed his fingers along the wood. "Ah! it's quite smooth where there are no scratches. They scraped it with a piece of glass." He nodded his head. "Now that's what I should do if I had stolen the boat and had to take the name off in a hurry." He looked up and frowned thoughtfully. "Really, I should like to see inside this house."

He walked back and pushed hard against the door, but there was no movement. It did not budge the fraction of an inch.

"Good lock," he muttered, "but still I could pick it in two minutes,"—he shrugged his shoulders—"if I wanted to, which I do not."

But somehow he thought quite a lot about the house on his way back to his tent, and as a result of his cogitations he returned there again in the afternoon to have another look.

This time he had brought with him a piece of stout iron wire, which he had taken from the luggage carrier of his bicycle.

The sea-gulls were still in evidence in front of the house, and he frowned again when he caught sight of them.

"Hum!" he murmured—"it would almost seem that they were expecting to be fed. Somebody evidently comes here pretty often—I must look out."

For quite a long while he manipulated with his piece of wire upon the lock of the door, but to his disappointment he could make no impression at all. He could not get the wire to catch anywhere.

"Now I would almost swear," he muttered, "that the door is not locked at all. There seems to be no bolt to prise back."

But the door fitted too close in the jamb for him to form any certain opinion as to whether his surmise were correct or not. He gave it up at length, and sitting down, proceeded to light a cigarette. He regarded the house very thoughtfully.

"Now why does it interest me at all?" he asked, very puzzled. "It's quite an ordinary house, built, naturally, of the stone that is plentiful about here. And that high window was undoubtedly designed to give a light out to sea facing up the gulf, where the fishing grounds probably are. Yes, quite an ordinary house, and yet—yet why was that name so carefully scraped off the boat and tarred over so that the scraping should not show? It puzzles me, for of course there was a reason for it somewhere. Yes, it puzzles me."

He was a long while getting off to sleep that night, and with his last waking moments his thoughts were of the black house.

In spite of his determination to forget everything that would remind him of his normal work, his imagination would insist upon running in familiar grooves, and he kept harping upon the probable association of the house with evildoers.

It was not a house of simple fisherfolk, he told himself sleepily. It did not belong to honest men. It was a rendezvous of murderers, it was a place of crime, and it harbored breakers of the law.

He became quite annoyed with his imaginings at last and, making his mind a blank, drew in deep heavy breaths and finally hypnotised himself to sleep.

The next morning however, he found the same thoughts continually recurring to his mind, and, partly to his amusement and partly to his annoyance, the black house became the chief source of interest to him in his enforced hours of solitude and ease.

He would climb up over the far cliff and almost the whole day long, perching himself upon a big rock, watch the house below. All the time he speculated idly, weaving romantic episodes of crime, with the square black house always the storm-centre of his imaginings.

He did this almost continually for four days—four days of scorching and terrific heat, with the sun all the time like one big red blister in the sky, and then suddenly his mind seemed all at once to clear and all his thoughts to crystallise into one strange and startling fact.

It burst upon him like a thunderclap that the house below was actually inhabited and that he himself was being watched from within it all the time.

He realised it all in an instant upon the fourth evening just before dusk, but later, thinking it over, he saw that two things particularly had led him up to this final conclusion and prepared his mind to accept it irresistibly and without hesitation, as a fact.

When going for his water that morning he had noticed the imprint of a boot in the mud by the side of the creek, but without giving any thought to the matter he had taken it naturally for one he had himself made when upon the same errand the previous day. He had, however, observed idly how much larger the impression had grown, but he had attributed that to the action of the water trickling down over the sides.

Then the second thing—subconsciously he had always been curious about the seagulls. They had been so persistent in staying in front of the house as if it were quite customary for them to pick up scraps thrown outside. He knew how tame seagulls were everywhere in Australia and how rarely they were harmed, and it had struck him over and over again that these particular birds were waiting before the house in the expectation of a meal.

Then had come the climax.

Sitting perfectly motionless, as he always did in his musings, he had seen a fox come lurching down over the hill, and the animal, catching sight of the seagulls, had at once started to stalk them. Crouching low upon his stomach and taking cover of every rock and every depression in the ground, he had crept furtively forward. He had reached the back of the black house; he had crossed along the side and had progressed until he had been almost level with the door; then—he had stopped suddenly as if he had been turned to stone, and for five seconds had stood with one paw raised and his head thrust forward exactly as if he were sniffing at the door. Barely five seconds, and then—he was off back like an arrow over the hill.

Like lightning had the meaning of it come to Larose.

The fox had sensed the smell of human beings and in the vicinity of dreaded Man had flown for his very life.

The detective put up his glasses and covered the house. Then he sat perfectly still again. The sun was sinking blood-red into the sea behind him, and he knew his head and shoulders would be silhouetted in sharp outline against the sky.

He held his breath in excitement, but his brain was cold and clear. He must not betray himself; he must not give himself away. If anyone were watching him it must not be known that he had noticed anything.

He wanted time to think, to gather in his thoughts. What did it mean if the house were occupied?

If someone were there, if someone were hiding himself, then he was an evildoer and he had good reason for keeping himself hidden. He had not shown himself because he had seen there was a stranger about and was afraid.

Then quickly the detective's thoughts ran on, and his mind harked back to all the happenings since he had left the city.

Of course, he could understand everything now—the men who had killed the death-adder, the horsemen he had seen upon the roads among the hills, the lights burning in the houses late at night, and the many people he had had to avoid when travelling from the city.

It was all clear now—everything fitted in so well.

Someone was 'wanted' in the State. Some crime had been committed somewhere and everyone had been on the look-out for the perpetrator or perpetrators of the deed. They had been picketing the roads, they had been searching through the thickets round Mount Lofty, they had been beating the bush all around the hills.

And now the very criminals that were being sought for were probably here in hiding in that house below. And there must be two of them, for if they had come by sea, as seemed most likely, one alone could not have pulled up that heavy boat to where it lay. Yes, there were certainly two of them, and for four days and nights he had been the whole time within a few hundred yards of where they were concealed.

And they had seen him too.

There could be no doubt about it—they had seen him like a spy creeping about their place of refuge.

They had watched him through the window, with his binoculars glued hour after hour upon the house that sheltered them. They had heard him prowling round and manipulating, too, with his piece of wire upon their door.

Then what must they have been doing and what indeed must have been their thoughts?

Their faces must have blanched in fear, their hearts must have drummed against their ribs, and many times they must have held their breaths lest he should hear their breathing through the walls.

They must have been agog, too, with doubt as to who he was and what was his mission there. They must have felt like rats caught in a trap.

They must have suffered, too, in body as well as mind, for all the hot days long they had lain sweltering behind the heat of that closed door. No breezes from the sea had reached them, and they must have been almost suffocated for want of air.

Then one of them from dire necessity had had probably to leave the house for water, and at night he had crept like a stricken animal to the creek. All the time then his heart must have been quaking and every moment he must have been expecting the crack of a pistol and the tearing of a bullet through his loins.

The detective puckered his brow in perplexity.

But what after all, if he were mistaken? What if it were all an imagining and the fevered thoughts of a sick man's dream? He was not yet completely recovered from his illness, and might not his mind be still unsteady like his body?

He thought for a long while.

No, no, the evidence was cumulative in every way, and he understood, too, now why he had not been able to pick the lock of that door. It had not been locked at all, but simply bolted on the inside. That was why his piece of wire had not been able to engage anywhere with the catch of the lock. Oh! what a fool he had been!

Yes, things were clear now. Criminals or no criminals, crime or no crime, the house in the falling darkness there, he was sure, harbored humankind, and it was according to all the habits of his life that he should at once take steps to find out what their hiding meant.

DIRECTLY it was fully dark Larose crept back to his tent, and by the light of a carefully screened oil lamp made ready for an adventure in the night. He was determined to put his suspicions to the test.

He was going to watch the house until the moon rose, for he was sure that after the burning heat of the day someone in the house of darkness would be going again for water to the creek. He changed his boots for a pair of rubber shoes, he buckled a small hunting knife to his belt, and carefully cleaned and oiled the little automatic that was always on his hip.

Half an hour later and he was crouching within a few feet of the door of the black house. It was then just nine o'clock, and, as he knew the moon would not rise until after three, he expected that a long vigil lay before him.

He settled himself close to the wall, and strained his ears to catch the slightest sound within the house. Everything was perfectly still. Not a sound, not a movement to betoken that there were any living creatures near.

An hour passed—two—three, and then suddenly the detective sat bolt upright, and two seconds later had slipped to his hands and knees, and was creeping like a shadow to the nail- studded door. He put his head close down and then—he smiled. He was satisfied. He had smelt the odor of tobacco smoke.

In a quarter of an hour he was back again in his tent and thinking hard.

Certainly he must learn something about the occupants of the black house, but he must alter his tactics now. They must not catch sight of him again; he must make them think he had left for good. He would move his camp directly it got light, and take it away at least a mile, but he himself would return at once, and from quite a different direction would continue to watch, but now unseen.

There were plenty of places where he could find cover, and he could lie even closer to the house than he had been before; then, when those who were hiding saw no more sign of him, they would naturally think that he had gone away and would come out. He would then see what manner of men they were. But he must be careful, he must be very careful, he told himself, for they were probably dangerous men who would not be over squeamish in finding means to make him hold his tongue. If they caught him, all the surroundings of the place were so lonely there would be small chance of discovery if they did away with him by violence. They could throw his body over the cliffs into the sea, and the sharks would see to it that no evidence would ever be forthcoming as to how he had met his end.

Then another thought struck him. Suppose already they were planning to get hold of him and find out his business there! Suppose even now they were out upon his track! For four days they had seen him watching the house, and the uncertainty and anxiety they must have felt would surely have gone a long way to make them willing now to take some risks.

No, no, they could not at any rate be searching for him yet. They could not search among the rocks in the pitch dark, and they would not dare to carry a light. But what about when the moon rose, as it would do between three and four o'clock? They might slip out then and try to find out where he was sleeping, or at any rate secrete themselves in some convenient position, so that when morning came they would be able to take him unawares. They knew from which direction he had always appeared, and by making a detour they might, directly it grew light, become the trackers instead of the tracked.

He smiled grimly to himself. Well, he would sleep away from "home." So he picked up his ground-sheet and, without undressing, made his way to a long flat rock about fifty yards away. No one could get behind him there, he knew, for the rock was at the edge of the cliff, and on the far side there was a sheer drop of a hundred feet and more to the sea below. The cliff jutted out sharply and, high water or low, the waves were always lapping at its base.

He looked at his watch. It was a quarter to one. Good! Then he had just over three hours to sleep, and with his senses trained as they were he could wake as he willed, at four o'clock. He spread his ground-sheet by the side of the rock and, lying down, in five minutes was fast asleep.

He had dropped off quite certain that in the friendly darkness he was secure from all harm and that no danger to him lurked anywhere. Yet such is the uncertainty of life, a big tiger-snake lay coiled under the other side of the rock, and not ten paces away a death-adder was sleeping in a tuft of grass.

Towards morning there was a rustle of movement within the black house and the beam of an electric torch shot across the floor. "Four o'clock," said a low voice, "and the moon is up. I'll unbolt the door and we'll go round by the creek first."

Larose slept heavily and the three hours he had allotted lengthened quickly into five. His senses might certainly be trained, as he had told himself, but he had made no allowance for his recent illness, and Nature now contemptuously ignored the resolutions he had made. It was after six when he awoke and the sun was well up in the sky, and he only woke then because he heard a sound near him, the crunch of a boot upon a stone. Opening his eyes quickly, they nearly froze in his head. A man was standing not five paces from him, leaning over the very rock under which he lay.

The man was holding a pistol in one hand and with the other he was shading his eyes from the sun. The end of a thick iron bar protruded from the pocket of his coat. The man was burly and thickset, and he had a big frowning face and a square jaw. He was unshaven and unkempt. Standing with his head craned forward, he was sweeping his eyes round in every direction. There was, however, something furtive in his movements, as if he were anxious to see and yet not himself be seen. Suddenly, on the instant, the expression of his face changed, his gaze became fixed, his eyes stared and his mouth opened wide.

"He's seen my tent." muttered Larose softly. "Now—something's going to happen," and the detective very gently drew out his own automatic and released the safety catch.

The big man turned round and began to gesticulate wildly. Apparently he was pointing out the direction of the tent to someone lower down the cliff. Then he leant heavily upon the rock and, raising his pistol, appeared to be taking deliberate and careful aim.

"Oh!" whispered the detective, "he's seen my haversack and thinks it's me. He's going to shoot, the devil." But the big man was evidently uncertain what to do. Three times he lifted his pistol and three times he lowered it again to his side. Then he bent down as if he were trying to peer under the flap of the tent.

The detective thought rapidly. The man meant murder without doubt. The wretch was going to shoot on sight. It was no time for squeamishness, and hesitation was a fool's card to play. Any moment the man might turn his eyes and then his pistol would spit out instant death. Larose raised his own pistol and covered him over the heart.

Then suddenly the man made to creep stealthily forward, and he looked down to see where to plant his foot. His eyes met those of Larose, his face grew ghastly, his jaw dropped, his hand—but there was a flash of fire from under the rock, the crash of a pistol at close range, and spinning round with a hoarse cry he fell backward to the edge of the cliff. For perhaps five seconds he lay poised with inches only between him and the drop to the sea, below. Then, a last convulsive shudder shaking him, he turned on his side and suddenly, quicker than the eye could follow, disappeared from view.

Larose sprang to his feet to look over the cliff, but instantly had reason to regret his haste, for three bullets in quick succession splattered on the rock. He threw himself down again and swore deeply at his want of thought. Of course, he ought to have remembered there were two of them, he told himself disgustedly. He had seen the man he had shot beckoning to someone, and without doubt the other wretch was not far away.

The detective's heart pumped like a piston. The position now was menacing to a degree. His second adversary knew exactly where he lay, but he himself had no means of knowing from which particular direction danger threatened, and at any moment the pistol might open fire again.

Instantly the detective made up his mind. At all risks he must move away. He knew the lie of all the rocks upon the cliff, and with caution he ought to be able to work round, so that anyone who was stalking near his tent would be taken in the rear.

Ah—a thought struck him. Better still, he would make for the black house and lie in ambush there. That was the very thing. The man who was after him would sooner or later return down the cliff, and then would meet with a reception that was quite unexpected.

Larose said afterwards that all his life long he would remember the two hours that followed. He had to make a long detour and crawl low upon the ground the whole time. Never once did he dare to rise even to the level of his knees, and very soon his muscles were so sore that he could have cried out with the pain. His eyes were full of dust, the burning sun beat down upon his head, he was saturated with perspiration, and a fierce thirst tortured him.

Over every yard he covered he had to hold his pistol raised ready to fire, and all the time he had to keep on looking backwards, in case he should be sniped from behind. He was in both great physical and great mental distress.

It was a dreadful journey, and a sigh of relief burst from him when finally he had left the rocks behind, and was no longer in a position to be taken unawares.

Then suddenly he smelt something burning, and straight before him he saw faint spirals of smoke coming up from over the other side of the hill.

"Now, what the deuce?" he began, and then he rose abruptly to his feet and raced across the turf to where he could look down over the cliff.

He whistled in astonishment. The black house was on fire. Smoke was pouring out of the window, and he could hear the loud crackle of burning wood.

For a moment the smoke formed a screen, and he could see nothing beyond the house itself. Then a puff of wind came, and the screen suddenly lifted.

A cry of dismay burst from his lips. The boat was no longer by the black house. It was two hundred yards out to sea—there was a man in it, and he was hoisting a sail.

An hour later, and a very tired Larose limped back to where he

had left his tent. In appearance he was very subdued.

He had watched the boat until it had become a mere white speck up the gulf, he had searched fruitlessly among the burning embers in the black house, and he had sighed many times as he had thought of all that had happened and what it must mean to him now.

The rest and peace of his holiday had been rudely broken, and he must return at once to his life's work. Crime and evil were calling to him, and it was not in his nature to turn a deaf ear. He had become involved, too, in happenings that were terrible, and it would trouble him all his life long if he could not justify his actions.

He had killed a man of whom he knew nothing at a moment's notice almost, and he must find out why it had been necessary to do it.

What now had been the reason for the deadly purpose of those in hiding in the black house that they must murder him offhand, simply because they had seen him watching in their vicinity? Why had they been hiding there at all? Was not his surmise correct that they were fugitives from the law, and 'wanted' for some dreadful crime?

Ah! But he would find out. He must find out, for his wounded pride insisted that he should. He had cut a poor figure that morning. He had greatly under-estimated the intelligence of those he had been up against, and he had suffered accordingly.

To think that all the time he had been crawling along painfully among the rocks on his stomach that second man had been calmly and contemptuously preparing for his get-away!

With the tide low as it was it must have taken the wretch quite a long while to drag that boat over the sands into the sea, and yet from all appearance he had gone back afterwards with complete assurance to set fire to the house.

The detective gritted his teeth in annoyance, but there was more annoyance for him still when he got back to his camp.

A scene of destruction awaited him.

His haversack had been torn open and all his things strewn about. His binoculars had been crushed viciously into the ground, the lenses and the prisms all broken. His water-bottle had been cut and emptied, the tyres of his bicycle slashed to ribbons, and his boots had been taken away.

"Really, a most thorough workman," sighed Larose when at last he had gauged to the full the extent of his misfortunes, "and most far-seeing, too. Evidently I am to be delayed as long as possible from getting in touch with the police." He nodded his head grimly. "Ah! but it will be a great day for me when I have him in the dock. He's bested me now, but I'll get him presently."

SOME four days later the Chief Commissioner of the South Australian Police was sitting alone in his room, at headquarters, in Victoria-square.

He looked tired and anxious, and his face was puckered in a frown. He was going through some papers and he signed from time to time.

He was a small spare man of wiry physique, about fifty years of age, and his hair was growing grey about the temples. He had keen, shrewd eyes, and a good chin, but the general effect of strength in his face was marred to some extent by a certain weakness of the mouth. He had a small moustache, spikily waxed at the ends. He was well, indeed almost foppishly dressed, and he sported a large diamond pin in his cravat. His hands were well cared for and white.

A police constable knocked and entered. He handed the Commissioner a letter.

"Bearer waiting, Sir," he announced. "He gives his name as Hunter, and says he would like to see you, if you could spare him a few minutes."

The Commissioner opened the letter and then at once elevated his eyebrows.

"Show him in," he said briskly, adding after a second—"and if anyone wants me now, say I am engaged for a few minutes."

A youngish-looking man was ushered in. He appeared to be somewhere in the late twenties, and had a pleasant boyish face and smiling eyes. He was well dressed and carried himself jauntily, as if life were very happy for him and he were well satisfied with everything. He bowed politely to the Chief Commissioner.

The latter waited until the door was shut, and then with a pleased and interested expression upon his face rose from his chair.

"How do you do, Sir?" he began, smilingly. Then he seemed to start. He looked down, and began to turn over the papers on his desk.

"Colonel Mackenzie suggested I should call upon you, Sir." said the young man. "I have come over here on holiday, and he asked me to see you and give you his kind regards."

"Yes, yes," said the Commissioner, looking up after quite a long pause. "Please be seated. How is my old friend, Robert Mackenzie? I haven't seen him for years."

"Andrew, Sir," corrected the young man deferentially, "Andrew, not Robert, and he's quite well, I am glad to say."

"No more trouble with his heart, eh?" queried the Commissioner. "That excessive cigarette smoking of his hasn't knocked him up then?" and he regarded his visitor very keenly.

The young man smiled and shook his head. "He never smokes cigarettes, Sir: nothing but a pipe, and as for his heart—well, I've known him, almost intimately I may say, for seven years, and never seen him ill or heard him complain."

"Ah!" said the Commissioner, "that's good to know, very good." and he continued to regard the young man with a very thoughtful pair of eyes.

His visitor laughed shyly.

"Oh! it's quite all right, Sir, I am Gilbert Larose. I'm purposely carrying no cards or letters of introduction on me because I am on holiday, as I've told you, and am ordered to keep away from everything connected with my work. I have just got over a bad bout of typhoid." His eyes twinkled merrily. "I certainly have not had the pleasure of meeting you before, but I've handled several cases for you over in New South Wales, also I am well known to Inspector Davis and Sergeant Driller in the force here. If you remember, it was I who found Laurence, the absconding banker, for you last August and you were good enough then to send me a letter of personal thanks, also—"

"Enough, enough," said the Commissioner, and he smilingly held out his hand, "but there were suspicions, you know, and it was best that I should make sure."

"Suspicions?" asked Larose, smiling back. "Pray what suspicions, sir?"

The Commissioner frowned. "Look here, young man," he said with mock severity, "you come in here to interview me with a loaded Yankee pistol in your hip pocket. You give the name of Hunter to the constable, you tell me you are Gilbert Larose, and yet you are now staying at the Southern Cross Hotel under the name of Edgar Barratt." His face broke into an amused smile. "Now isn't that enough to make anyone suspicious to start off with?"

The detective got very red. "Oh! you know then that I am at the Southern Cross!" he exclaimed.

"Certainly," replied the Commissioner. "It is my business to know." He laughed gently. "And I know a lot more about you, besides that. Listen!" He picked up a paper from his desk and scanned down its contents. "You arrived in Adelaide fifteen days ago. To be exact, upon the seventh of the month, and you went off upon a bicycling expedition to a lonely part of the coast. You returned the day before yesterday and put up, as I have said, at the Southern Cross. Yesterday you spent two and a half hours at the Public Library, looking through the newspaper files of the past fortnight. You are interested in the escape of Miles Fallon from the Stockade, and you are of opinion that it is gross carelessness on our part that the murderer has slipped through our hands. This morning—"—the Commissioner leant back in his chair and spoke as if half in fun and half in earnest—"well, this morning you have come to tell me you can find the fugitive, and that in due time you will claim the 500 pounds reward that we are offering for his apprehension. Now is not that so?"

The face of Larose was the very picture of astonishment and he regarded the Commissioner with an expression that was almost frightened.

"You are correct, sir, as to my movement," he said very slowly, "but I won't pretend that I know how you learnt them all."

"Oh! quite simple, Mr. Larose," chuckled the Commissioner, enjoying to the full the detective's discomfiture. "Just one of those chance happenings that come to us all at times. No, I won't try and mystify you. We got on your track simply because of your curiosity yesterday at headquarters here."

"My curiosity!" exclaimed the detective. "My curiosity here?"

"Yes, here!" laughed the Commissioner. He leant forward and pointed his finger at the detective. "You were passing in the square here yesterday morning, Mr. Larose, and you stopped to read the announcement on the notice board outside. You read most carefully through the placard giving the description of the escaped Miles Fallon, and the 500 pounds reward offered for his apprehension. You then walked away but returned twice again at short intervals to re-peruse the placard. Your obvious interest attracted the attention of one of our plainclothes men who was on duty in the station yard—we are all very much on the jumps just now about anything concerning the missing man—and he followed after you the third time when you went away. He watched you go straight into the Public Library on North-terrace and saw you turning over the newspaper files. He moved near to you and saw that you were reading everything you could find about the murder at the Rialto Hotel. He is quite an intelligent fellow, this plainclothes man of ours, and he snapped you with a pocket camera as you came out of the library. Here, by the by, is the snapshot. Quite good enough to enable me to recognise you when you came in here three minutes ago. Your style of collar is rather high, and, if I may say so, at once catches the eye. Well, he shadowed you next to the Southern Cross Hotel, and when you were at lunch made some enquiries about you." The Commissioner laughed again. "And with the connivance of the manager he even went over your things in your room. He saw the obviously recently-purchased fishing rod with Fleming's name upon it, and also the Adelaide railway-station cloakroom ticket pasted on your valise. He then proceeded to pursue his enquiries at both those places. The number on the cloak-room ticket made quite clear how long the valise had been left at the railway-station, and at Fleming's they remembered you at once, when the snapshot was shown. They told him then that you had had a strap sewn on to the case of the fishing rod so that you could carry it on a bicycle. Also, you had asked them about the likely places on the coast where you could catch snapper from the rocks."

The Commissioner leant back again in his chair in great good- humor. "All very simple, isn't it, Mr. Larose? but it just shows how very dangerous chance may be. Of course, we had nothing definite against you, but the incomplete box of automatic cartridges in your valise made us curious enough to want to keep an eye on you, and I have no doubt but that someone even followed you here this morning. We don't like inter-State visitors who carry arms you know. As to your opinions of the Rialto Hotel affair, well,"—he shrugged his shoulders—"you pumped the head waiter of the Southern Cross pretty thoroughly, now didn't you?"

The eyes of the detective were on the ground. He had been expecting far more embarrassing disclosures and he was smiling in his relief. After a moment's hesitation, he looked up.

"I see I'm quite a beginner in my profession, sir," he said humbly. "I shall have to start at the bottom of the ladder again."

"Not at all, not at all," laughed the Commissioner, "you are still the star detective of the Commonwealth, our one and only incomparable Gilbert Larose." He suddenly became serious again. "But your visit to me now. You came to suggest something?"

Again Larose hesitated. "I am on holiday, sir," he said. "I have been very bad with typhoid and I came here to rest." He sighed. "But I am bored, and this is a very interesting case."

The Commissioner nodded gloomily. "A very terrible case, too," he said. "We are just at a dead end. The man has vanished completely, and there is not the ghost of a clue to suggest where he has gone. The public are calling out against us, and we are under a dreadful cloud. Your coming may turn out to be most opportune, for we will clutch now at any straw. No, no," he went on hurriedly, for he saw Larose smile. "I don't mean that at all. You are not a straw. You would be a tower of strength to us if you would help."

"But I act like a child now," said Larose sadly. "Or you wouldn't have been able to turn me inside out like this. My illness has given me a soft head."

The Commissioner spoke impressively.

"Mr. Larose, this should be just such a case as you would love. It should appeal in every way to that strange instinct of yours. Nothing apparently to help you. Nowhere to start off from. Only the bare and naked fact that the prisoner escaped from our stockade here, when all eyes must have been on him—in broad daylight, too."

The Commissioner pulled his chair forward.

"But come," he went on briskly, "you shall hear everything before you decide. I will give you all the inside information from the very beginning, and you can tell me then what you think."

He touched his bell, and the constable who had ushered in Larose immediately reappeared.

"I am engaged," said the Commissioner curtly, "and I am not to be disturbed." The constable retired.

"Now, Mr. Larose," said the Commissioner, folding his hands together and lowering his voice almost to a whisper. "I'll tell you as strange a story as has ever been recorded in all the black annals of Australian crime, a story perhaps without parallel in its easy and contemptuous flouting of the law." He raised his hand protestingly. "But please for the moment forget everything that you have read in the papers yesterday, and try and listen to me as if you had heard nothing of the matter before. I want you to approach everything with an entirely open mind."

He paused for a moment as if to weigh his words.

"Now, to begin with, you know, of course, the social conditions pertaining generally everywhere, all the world over, since the Great War." Larose nodded. "Well, ours here are just the same. Money opens all doors. Our social aristocracy is appraised to an extent on a strictly cash basis, and if you have money to throw about you are assured of a seat among the elect. Well, just about two years ago. Miles Fallon descended on the city. He came as part proprietor and manager of the Rialto, our crack hotel here. He was then about five-and-thirty years of age and a good-looking, polished man of the world. He was a man of personality, likeable and apparently with plenty of money, and was received with open arms. He went everywhere, and was a favorite with everyone. His name appeared almost every day in the social news. He was received in quiet select circles, and he hobnobbed with the rich people of importance in our State. He was lunched and tea-ed by the racing clubs, and at many public functions he was prominently in evidence. In effect, he was a big bug in our little insect world. Well—imagine the absolute amazement of his admirers and friends when just a fortnight ago he was arrested for murder. Yes! Caught at 2 o'clock in the morning, practically in the very act, and seized when the body of his victim was still quivering in the throes of death. He had smothered an old man, a visitor to his own hotel, smothered him with a pillow, and it was only by the merest chance, mind you, that he was caught.

"He had just committed the crime, and was creeping out of the bedroom, attired in a dressing gown, and with his head muffled in a towel, when he banged right into two night revellers who, in consideration of their reputations, were sneaking up the corridor with their shoes off.

"Something about the appearance of Fallon made the two men immediately suspicious—there was blood upon the towel, for one thing—and they barred his way and asked him what was up.

"Then Fallon, quite unusually for him, for he has always had the reputation of being a cool fellow, apparently lost his head and he lunged out instantly and knocked down one of his interrogators, but the other got in one under the jaw and Fallon collapsed.

"Then things happened very quickly.

"The bedroom door was still open, and while one of the men kept an eye on Fallon the other went in and switched on the lights.

"A ghastly sight met him—an old man with a blue-black face, and a bed with the pillows all smeared over with blood.

"Ten minutes later our men were on the spot, with a medical man close upon their heels. It was remarked at once that the manager of the hotel was not present, but the information was forthcoming that he could not be found.

"It was seen immediately that the old man in the bed was beyond all aid, and attention was accordingly turned to Fallon. He was still unconscious from the blow he had received, and had not yet been recognised.

"He was carried into an empty bedroom and his face sponged with cold water. Immediately then, the eyebrows and the moustache came away and, to the consternation of these standing round, the assassin was recognised as the suave and polite manager of the hotel."

The Commissioner raised his hand impressively. "Imagine the bombshell when it became known in the city! Later in the day, Fallon was charged with wilful murder and was lodged in the cells.

"The motive for the murder was quite plain. Robbery, pure and simple. The victim was a well-to-do resident of Kapunda, and it appeared he had come down the previous day to sell some property in the city. The sale had been effected late in the afternoon and as is usual in such cases the deal had been transacted in hard cash. In some way, Fallon must have got to hear of it, and so in the dead of night he had gained entrance into the old man's room with the master-key of the hotel. Absolute murder was probably not intended, although from the contents of Fallons dressing-gown pockets, the wretch was prepared to go pretty far. He was carrying not only chloroform, but also tablets of sulphate of morphia and a hypodermic syringe.

"What we think is, that the old man woke up as Fallon was attempting to chloroform him, and then the latter, in a panic, seized upon a pillow as the only way to quieten him. At any rate the old man had put up some sort of a fight, for Fallon had bled profusely from the nose, and it was actually the wretch's own blood that had made the character of the death look so ghastly."

The commissioner stopped speaking to light a cigarette, and Larose remarked thoughtfully:

"Was there any reason, do you know why the sleeping man should have been disturbed at all?"

"Oh! yes," replied the Commissioner, "I was going to tell you. Fallon was carrying away the old man's money belt that contained 3,800 pounds in Treasury notes. The old chap had undoubtedly been wearing the belt in bed, and from the disorder in the room we think Fallon had searched everywhere else first, before turning to the sleeper and discovering the belt on him."

"But how do you know," asked Larose, "that he had got the belt on him in bed?"

"Because," replied the Commissioner, "it had been torn off so hurriedly and with such violence that the straps were broken."

Larose made no comment, and the Commissioner continued.

"Well, two days later, a verdict of wilful murder was brought in in the coroner's court, and Fallon was committed for trial. Now comes the most disconcerting part of the whole business, and the one which, occasions us such profound disquiet." The Commissioner spoke very slowly. "The prisoner had not been in the stockade for forty-eight hours before he walked out again in broad daylight, as if he had been no prisoner at all."

The voice of the Commissioner took on a bitter and incredulous tone.

"Yes! Walked out as if he were a free man! Opened and shut his cell door and vanished from that moment as if he had never existed at all! No one heard his door open or shut, no one saw him go, no one noticed anything at all and yet—yet the stockade yard was full of people, there were guards on duty everywhere, and it was in the middle of the afternoon."

The commissioner dropped his voice still lower and leant forward across his desk until his face was close to that of Larose.

"Now, what does that mean, sir I ask you? What does that mean?" His voice rose and hardened. "It means, Mr. Larose, and that is why we in authority are in such trouble here—it means that the miscreant Fallon was only one of several. He must have had allies somewhere, confederates both within the Stockade and without. He was one of a gang. We are sure of it. But listen again." The Commissioner spoke now in his natural voice. "Now, what happened after? We at once suspended two of the warders at Blendiron, the assistant chief warder, who was in charge of that part of the Stockade where Fallon was confined, and Bullock, a warder under him, who had charge, amongst others, of the prisoner's particular cell." The voice of the Commissioner was slow and solemn. "Well, Blendiron, too, vanished off the face of the earth within twenty-four hours, and Bullock was found drowned in the Torrens River upon the evening of the next day." The Commissioner sat up with a jerk. "Now, Mr. Larose, ask me what questions you like."

But the detective, it seemed, was in no hurry to ask any questions at all. He was looking out of the window, and from the expression on his face his thoughts were far away. It was quite a long while before he spoke.

"The greater problem and the lesser," he said slowly. "Well, we'll take the lesser first." He became brisk and animated. "Now how much start do you think the prisoner had had, before you discovered that he had got away?"

"Ten minutes," replied the Commissioner promptly, "not a second more. We are sure of that because he had been out previously in the exercise yard, and had just been returned to his cell to be in readiness for a doctor who was coming to see him at 4 o'clock. He had been complaining of a bad cough that would not let him sleep at night."

"And it was certain," asked Larose, "that he had escaped straight away out of the stockade? I mean, he couldn't have been in hiding somewhere in the buildings, and have got away later on?"

"No, quite impossible," replied the Commissioner, shaking his head: "he must have got right away at once, for a quarter of a minute after we had discovered that the cell was empty—not even a mouse could have got outside the prison walls. Every crack and every crevice was gone through with a fine comb."

"And no traces of him were found anywhere, afterwards?"

"None whatever," said the Commissioner. "It was just as if he had gone up in smoke. No one had seen him, and there were no rumors even that anyone like him had been seen outside on the road. He couldn't immediately have got away to the city either, for we had drawn a cordon round Adelaide at once. Nor could he have got out of the State, for every road and every railway- station was watched—as indeed they have been ever since."

"There was the sea," said the detective thoughtfully. "In the description published of him, I remember he is described as tattooed with an anchor upon one arm, and that almost certainly means that at one time he has followed the sea. Yes, there was the sea, and I have always noticed that a sailor-man in trouble turns back to the sea. That is his first thought."

The Commissioner shook his head again. "No chance whatever," he said—"every outgoing vessel was searched."

"But a boat," persisted the detective. "He might have gone off in a boat."

"None was missing," said the Commissioner emphatically. "We thought of that, and most exhaustive enquiries were made."

"But there was a fire," said the detective very softly. "I saw in the newspapers that there was a fire on the night of the fifteenth in the Port Adelaide docks, and that the sailing barque Clan Robert was burnt to the water's edge." The tone of his voice became almost apologetic. "Might not now the fire have been engineered to cover the theft of one of the ship's boats?"

The face of the Commissioner grew rather pink.

"We had no report," he said brusquely, "that any of the ship's boats were not burnt, too."

The detective did not press the point.

"And the warders who were suspended?" he asked. "Had you any reason to suspect them of complicity in the escape? Anything definite, I mean."'

"No, not at the time," replied the Commissioner. "They appeared to be quite as astounded as everyone else. They were both men of long service, and we suspended them only as a matter of routine, until the official enquiry should be held."

"And they are both beyond questioning now. One is missing, you say, and the other dead?"

The Commissioner sighed wearily.

"Yes, it is mystery upon mystery, Mr. Larose, and we can make nothing of it. It looks now as if they had been implicated and were removed violently so that they should confess nothing. The man Bullock was of weak temperament, and if he had had anything to tell we should have got it all out of him very soon. But Blendiron was of quite a different type. He was of the fighting kind, and very sure of himself. He was big and burly in mind as well as in body. He would have been a hard nut to crack, I admit."

The detective stooped down suddenly to adjust the lace of his shoe.

"And have you had no news at all," he said slowly, and without looking up, "of this assistant chief warder, Blendiron, since that afternoon?"

"We know nothing," said the Commissioner, "except that he went straight home that afternoon, appeared to be very depressed, went out again just before 6 o'clock, and has never been seen since. Probably he was murdered in some such way as Bullock had been. No doubt they both knew too much, and were of no further use to their employers, so they were got rid of as speedily as possible." He shrugged his shoulders. "At any rate, that's what we think."

Larose made no comment. He had finished adjusting his shoe lace and was now looking out of the window again. There was a long silence, and the Commissioner chewed fiercely at the cold butt of his cigarette. Suddenly, however, he spoke again.

"But that is not all I have to tell you, Mr. Larose. You spoke just now of a greater and a lesser problem that lay before us, and you were quite right. These events of a fortnight ago were not isolated happenings; they were not events by themselves." He thumped his fist upon the desk. "They were links in a chain of crime: they were two events in quite a long series of crime."

He paused for a moment to relight his cigarette.

"But listen still further. For over a year now we have been conscious of a peculiar current of evil-doing stirring in the city, and we who are in authority are convinced there is a master criminal working here. There have been numerous robberies in hotels principally. There have been crimes of violence, murder has been done." He spoke with deliberation. "They have been all well-planned crimes, too, well thought out and well executed, and we have been baffled every time. No clues to pick up, nothing we could ever follow on. To take only the last few months—all crimes of night—a man drugged and robbed at the Gulf Hotel, a thousand pounds and more filched from two inter-State visitors at the Grand Australasian, a wealthy stockbroker stunned and his safe broken into when he was working late at his office, and the naked body of a man, tied up in a sheet, found under most suspicious circumstances in the Torrens River at the foot of the weir. This last man was never identified, but enquiries are now coming through from London for information as to the whereabouts of a party who was carrying a parcel of precious stones upon him, and who should have sailed from here by the Nestor ten weeks ago, and the description tallies with that of the body found in the Torrens weir." The voice of the Commissioner took on quite a pathetic tone. "Now you can understand how worried we are. The Press is up against us, the public is thirsting for our blood, and the other States are jeering at this city as being the most criminal of all the cities in the Commonwealth."

The detective smiled at the woebegone expression on the Commissioner's face.

"But this escape, Sir, from the stockade," he asked—"surely you have formed some theory as to how, when he had left his cell, he got away from the building itself?"

"We have formed no theory, Mr. Larose," said the Commissioner solemnly. "And it has amazed us all the time that even with the connivance of the two officials he was able to get clear from the buildings. Blendiron and Bullock could have helped him only a third of the way. He had to cross parts of the prison over which they had no control. But see here, I'll draw you a rough plan of the place." and the Commissioner took out his fountain-pen and pulled a pad of paper before him. "Now, here is the outer wall of the stockade, twenty-two feet high with the top four feet made up of loose bricks. You understand, of course, no one can consequently climb over without bringing down loose bricks and at once attracting attention by the noise. Well, here in the middle are the cells and here is the particular one where Fallon was confined. It opens into this corridor, which is about twenty yards long. At the end of this corridor comes the exercise yard. Unlock another door here and you are in the general courtyard. You cross this courtyard and here are the entrance gates to the stockade." He looked up at the detective. "You see, Mr. Larose, Fallon had not only to get out of his cell and along that first corridor, but he had also to open the door at the end, cross over the exercise yard, unlock another door there, cross over the main court-yard, and then induce the guard on duty at the entrance gates to unlock them and let him through. It seems a sheer impossibility, for, granting that Blendiron and Bullock had passed him through into the exercise yard, their territory ended there, and he would have needed more accomplices to see him clear of the entrance gates. The whole prison couldn't have been in his pay, yet he would have been under the observation of a score of pairs of eyes at least while passing through the two yards to reach the entrance gates. Just think of that."

"But if he were disguised," said Larose, "he could manage it?"

"But a stranger would have been remarked," retorted the Commissioner irritably. "And no one saw any stranger at all. Besides, if he were disguised, as you say, what became then of his old clothes? When he was remanded to the stockade he was wearing a light grey suit, and it was not left behind when he escaped, so undoubtedly he was wearing it."

The detective asked another question.

"Who were actually present when the discovery was made that he had escaped?"

"Three persons," replied the Commissioner. "Blendiron and Bullock and Fallon's medical man, Dr. Van Steyne. It was like this, as I have in part already explained to you. Fallon had complained that he was not feeling well, and, taking the privilege of prisoners on remand, he asked to see his own doctor. So they 'phoned to Dr. Van Steyne, who, by the way, is a foremost consulting physician in South Australia, and he arranged to come to the stockade about four o'clock. Accordingly at three-forty- five Fallon was locked in his cell to be in readiness, and within a few minutes—every one agrees certainly not more than ten—Dr. Van Steyne arrived. He was taken straight to the cell, the door was unlocked, and—the cell was found empty."

"And, of course, you asked the doctor," said Larose, "how the warders seemed to take it and whether they showed great surprise?"

"Yes," replied the Commissioner. "Van Steyne happens to be an intimate friend of mine, and I questioned him on the spot. At five minutes past four I got a telephone message from the stockade, and I was down there by a quarter past. I was told at first that the doctor had gone, but, I found he was in the infirmary yard with the prison surgeon. I questioned him minutely, and he was of opinion that the warders were in every way as much astonished as he was. He said Bullock went white as a sheet, and that Blendiron swore savagely."

There was a short silence, and then the Commissioner shrugged his shoulders.

"Well, that is all I have to tell you, Mr. Larose," he said with a sigh, "and I admit there is not much inducement for you to take up the case. As to where Fallon is hiding, as I say, we have not the remotest idea, and we don't know where to start looking." He smiled grimly. "Even you, sir, with that fabled extra sense of yours would not know where to begin. You would be bushed from the start."

"But I'm not so sure of that," said Larose thoughtfully. "There are some things that occur to me, there are some—" He hesitated, and the Commissioner broke in sharply.

"Oh! then you have some ideas, have you? You think that you can succeed where we have failed." He frowned slightly. "Good, then, you shall go down to the stockade at once. You shall—"

The detective shook his head. "No," he said quickly, "no, I'll take it on, but it is not at the stockade where I shall start. It is at the Rialto Hotel where I shall pick up the beginnings of the trail." He looked thoughtfully at the Commissioner. "A man cannot live for two years, you know, Mr. Commissioner, at any one place and not leave something of his inclinations and the tendencies of his mind behind. So we will gather up the threads of his life there, and they will help us to determine most likely what he is doing now." The face of the detective broke into a smile. "Yes, we must go to the place where he lived, and perhaps then we shall hear his voice still, speaking in the rooms that he inhabited, and maybe we shall even see his shadow still moving on the wall."

The frown on the face of the Commissioner deepened. He was at no time a man of much imagination, and he had no room in his psychology for poetical ideas.

"Good!" he said drily. "Then you shall be taken to the Rialto instead. I will detail Inspector Barnsley to go with you. He has been in charge of the case from the beginning and knows all there is to know." A suspicion of sarcasm crept into his voice. "And when you find out where Fallon is, please ring me up at once. It will be the best piece of news that has come in all my life and I shan't mind being disturbed. Now—" and he reached towards his bell.

"One moment, please, before you ring," interrupted Larose quickly. "If you don't mind. I should like as few people as possible to know that I am here. I always work as much as I can—alone."

"Oh! certainly," replied the Commissioner. "No one, indeed, except Inspector Barnsley, need know that you are helping us."