a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: Title: Thyra: A Romance of the Polar Pit Author: Robert Ames Bennet * A Project Gutenberg Australia eBook * eBook No.: 0900541h.html Language: English Date first posted: July 2009 Date most recently updated: October 2009 This eBook was produced by: Robert D Cody Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

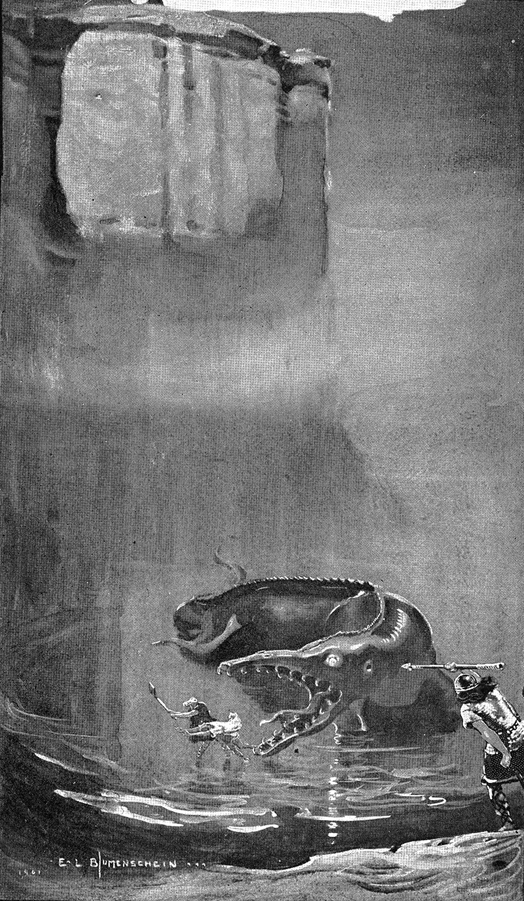

Hoding stood erect and whirled his axe up against the descending muzzle (Chapter XX).

Ice--ice on every side, north and south, east and west, as far the eye can see--not the broad, level floes of the Arctic Circle, with here and there a majestic berg towering skyward like some gigantic crystal cathedral, but a vast stretch of ponderous floe-bergs, ridged with jagged hummocks, their broken surface covered with snow, fast turning to slush under the blaze of the six months' sun. Here and there a narrow blue lane winds through the frozen wilderness, widening in places, closing in places, as the fragments of the great pack, separated by the spring break-up, drift south across the Polar Basin.

Such was the icy waste that had been our sole landscape for full eight months. In the fall of 1896, confident of success, we had started out across the Polar pack from our base camp on the north of Franz Josef Land. Never had a dash for the Pole been more carefully planned. Our equipment was as near perfect as money and experience could make it, and every member of our party was a trained athlete, thoroughly inured to Arctic travel. Lieutenant Balderston and his trusty negro sergeant, Black, each stood over six feet two, clear measure, while I myself could claim the negro's great girth and an inch more of height. As to Thord Borson, the Icelander, he was a veritable giant, seven and a half feet tall, and broad in proportion.

It was perhaps due as much to Thord's gigantic strength as to our good luck with the dogs that we covered a round three hundred miles of "northing" before the cold and darkness compelled us to go into winter quarters. We were fortunate, as well, in laying in a stock of bear meat sufficient to supply both ourselves and the dogs until spring.

The dreary months of twilight had passed with disheartening slowness, but the returning sun found us still cheerful and full of hope. Our one desire was to push on to the Pole. We had little doubt of reaching it. We need only duplicate our fall journey. But Fortune, never so fickle as in the Arctics, at last ceased to smile on us. Many of the dogs grew mad and died of that strange Arctic disease mistakenly called hydrophobia, and we had no more than started on from the winter camp when Balderston severely sprained his left ankle. As he could not walk, he was lashed to one of the sleds, and we struggled on as best we could across the terrible surface of the pack.

But the weather, too, turned against us. For weeks we had to lie under shelter while the spring storms raged over the frozen waste. Balderston's ankle improved very slowly; one after another the dogs continued to sicken and die; the floe-bergs became smaller in area, the hummocks higher more jagged, the drifts deeper. Still we struggled on, with dogged persistency, resolved to reach the Pole, or die.

Then at last came disaster, sudden and hopeless. After hardships and toil such as one cannot look back upon without a shudder, we had added another fifty miles to our northing. Almost spent, with only half a dozen dogs left, we yet faced the north, unshaken our purpose. But time had sped swiftly during our toilsome march. The spring had slipped by almost unnoted, and even while we vowed our firm resolve to continue onwards the end came.

In the spring break-up we were roused from sleep by a terrific crashing, and crawled out of our bags only in time to save ourselves as the floe beneath split open. We sprang safely away from the crevasse which yawned down into the icy-blue water, and Thord dragged with him the gun-sled. But the bulk of our outfit was engulfed and ground to powder as the walls of the crevasse crashed together under the shifting pressure of the pack.

The wreck of course compelled us to abandon all hope of attaining the Pole. The one object now was to regain Franz Josef Land alive. It was a problem--almost a hopeless one. We were out on the disintegrated pack, over three hundred and fifty miles from known land, without a boat to cross the lanes between the drifting floes, without food to last a fortnight.

But in the passing weeks, though our progress southward was almost imperceptible, no one starved. With the break-up of the pack, life returned to the frozen sea. The guns and ammunition saved by Thord stood us in good stead. After we had eaten the last scrap of dog meat, and were gnawing the bones, Balderston managed to shoot a bear. Long before that was devoured, another bear was killed, and, after it, two full-grown walruses. Then we rested easy. With food in abundance, we had only to await rescue by some venturesome whaler, when the drift had carried us down near Nova Zembla.

The 15th of June found us in the best of health, thanks to the fresh meat and frequent baths in the snow-water pools. For the sake of exercise we had spent much of our time in athletic contests, and each took turn-about in maintaining a constant patrol around the floe, on the lookout for game and a possible ship. But perfect as was our health, we were no longer the cheery, hopeful men who had fought their way northward against all the fearful odds of Polar travel. The bitterness of our failure had affected even Balderston, and we sadly missed his gay humour. Nor was our diet of raw flesh calculated to allay the irritation natural to men in our position.

Yet up to this time we had had no quarrels, none of those bickerings which occur so frequently in such parties, even during good fortune. I cannot remember a single harsh word spoken throughout all those eight months, and this notwithstanding Thord Borson's fiery temper. But on that June day the Icelander's patience at last stretched to the breaking point. Sergeant Black had come in from his four-hour watch, and halted before Thord, who sat staring morosely at the nearest hummock. Not noticing the latter's ill humour, Black saluted and held out the rifle, his face drawn up in the grin that the bullet-scar across his cheek made so grotesque.

"Yoah gahd, sah," he said, and he let the rifle slide down through his hand. In falling the weapon's stock glanced on a point of ice and struck sharply against Thord's foot. In an instant the giant was up, his eyes ablaze, his fiery hair and beard bristling, and his fist clenched to strike the astonished negro.

"Curse you!" he roared. "What do you mean by that, you black idiot?--You grinning dog!--Drop that gun, damn you, else I'll break your cursed neck."

"What's that?" cried Balderston, and we sprang up in amazement. We saw the Icelander striding forward, his gigantic frame quivering with fury, while the negro retreated before him, frightened and perplexed, but with the rifle at his shoulder. At the moment, his back struck against a hummock, and in sudden desperation, he sighted straight at the giant's heart.

"Halt!" he commanded. "One moah step, an' I shoot!"

"Thord!" I yelled, and together Balderston and I rushed forward to intervene. The giant turned at my cry, but we would have been too late. Seeing us coming, he swung about to rush upon Black. It meant death either to himself or to the negro--perhaps to both. For the moment, Thord was a madman--a Berserkir. But even as his great body bent forward to spring, the sergeant flung aside the rifle and pointed with both arms over the Icelander's head.

"Oh Lawd!--look!" he yelled. "A balloom!--a balloom!"

Around spun Balderston and I, and around spun Thord, sobered at the very height of his rage. Even as we turned a shadow fell upon and our upraised eyes were met by a gigantic sphere, drifting majestically over the floe, not a hundred feet above us.

"A balloon!--it is a balloon!" shouted I, and we craned our necks in our efforts to catch a glimpse of the aeronauts. But not a sign of life could we see. No hand waved to us from the car, no curious face stared down to meet our upturned gaze.

"They're asleep!" roared Thord. "Signal them. Where's the guns?--Ahoy, there! Ahoy!"

The Icelander's hail could have been heard a mile; but the balloon drifted on without a word or sign from the car. The blood surged back into Thord's face and his eyes blazed with reawakened fury.

"Shoot! shoot!" he roared. "Riddle the scoundrels in their car!"

"No, no! Look at the guide-ropes. Capture her!" cried Balderston, and he dashed towards the three lines which trailed down from the balloon and far out on the floe behind.

"We can't stop her!" I protested. Nevertheless, I ran with the others, and together we seized the nearest line.

"She'll drag us over into the sea. We can't stop her," I repeated.

"Not by pulling," replied Thord; "but take a bend around a hummock--"

"There's the very one we want," cried Balderston. "Forward now, with a rush, and pass the slack about that ice-cake."

"Forward!" we shouted together, and in half a minute we had the line coiled twice around a block of ice that would have anchored a battleship.

"Good!" growled Thord, as we stood clinging to the line behind the coil. "We have her fast! I hope the shock will spill them."

"They'll at least wake up. See her sway!" I exclaimed. "Hold fast, all!"

"Fast she am, sah!" shouted Black, and we stared, panting and excited, up the tautened line to our monster prize. So swiftly had all occurred that we had lacked time for wonder; but now, scarce able to believe our good fortune, we could only stand open-mouthed and gaze in speechless fascination at the huge sphere, which tugged and swayed at the end of the line like a noosed bird striving to escape.

Presently another wonder came upon us. After all our shouting and the sudden stoppage of the balloon, there was yet no cry or signal from the car. If there were any aeronauts aboard, they must either be dead, or in urgent need of aid. The thought aroused me.

"What can a balloon be doing here?" I gasped.

"The car is empty, or I'm a liar," exclaimed Thord. "I'll bet the balloon broke loose before the party got aboard."

"Empty or not, we'll pull her down and see," replied Balderston.

"Ay; that's the word," assented the Icelander, and with a deft sailor hitch, he made fast the line. Then he turned frankly to Black and extended a huge fist--"I was mad just now, sergeant. Shake?"

The negro grinned his ghastliest, as he hastened to grip the proffered hand.

"All right, Mistah Thod,--all right. An' now, we'll haul in de captibe balloom."

"If we can," I added.

"We can, if there is no one aboard to cut her loose or shoot us," said Balderston.

"I don't expect that; but our weight may not be enough. It's a whale of a balloon."

"Our weight?--Why, John, we scale up over a thousand pounds between the four of us. If that's not enough, I can shin up one of the lines and open a valve."

"Ay; don't worry, doctor. We'll have her down, one way or another. Lend a hand, Black, with the sled. It'll be well to take our guns aboard whatever we do with the airship."

"Or she with us!--But it's a good idea, Thord, if we ever do get aboard."

"Come on, then. I'm not dying to linger on this cursed floe."

So the sled was loaded with the remains of our equipment, and we tramped across the floe, through the slush and over the hummocks, to a spot directly beneath the sway of the balloon. At a word from Balderston, Black knotted the rueraddies into a sling for the sled. Then, all together, we grasped one of the slack guide-ropes and began dragging it down, hand over hand.

"This is play," laughed Thord, as the coils of line piled up beneath our feet. But Balderston shook his head.

"Only wait a bit," he replied. "She's pulling harder already. I may have to climb for it yet."

"Not if we can help it," said I. "To lose gas, would mean a greater loss of ballast when we ascend."

"And probably the only ballast aboard is food and equipment," remarked Thord.

"Haul away, and save your breath," said Balderston.

The advice was well given, for with every yard of line we took in, our task became more difficult. As if this was not enough, we had to contend with the unsteady jerking of the line as the balloon swayed in the breeze. By the time three-fourths of the line had passed through our hands, even Thord longed for a rest. It was now that Balderston's sled sling came in good play. The line being hitched to it, we stepped upon the sled, and our weight, with that of the ammunition, served to anchor down the balloon.

Panting and exhausted, but full of joy, we stretched our aching arms and gazed up at our captive. The bevelled bottom of the wicker car swung less than thirty feet overhead, so that we could plainly see how it was splintered all along one edge, as though by some violent shock.

"Hello! Looks like our air-cart had been in a smash-up," remarked Thord.

"Rather!--Stand steady! I'm going aboard," replied Balderston, and up the line he went like a sailor. In a little while he was above the rim of the car; his hands grasped the bearing-ring, and he drew himself up into the little swinging gallery above the car. We waited impatiently for several minutes before his head reappeared over the bearing-ring.

"Empty house!" he shouted. "I've been in the car--down through a man-hole. But there's no one aboard. One of the valves is partly open, or she would never have sunk so low."

"Luckily for us. Now what do you say, boys,--shall we go for the Pole again?"

"Yes! For the Pole! We'll make the Pole yet. Hurrah for Doctor Godfrey!" roared Thord.

"De Pole!--de Pole! Jes' wait, honey; wese a-comin' dah!" sang Black, and he cut a pigeon-wing on top of the sled.

"Get a move on you, then," laughed Balderston, as he flung over a rope ladder.

"We're ready, Frank, you may bet," I replied.

But how about the sled?"

"One of you come up to help hoist. Two had better stay there to hold things steady. We don't want the car to swing around against a hummock and knock us out."

"That's true," I replied, and at a sign from me, Black climbed the ladder, with all five rifles and the two shotguns slung on his back. He was soon beside his lieutenant, and the two together speedily hoisted up every package of ammunition and the scant remainder of our equipment. Then, while Thord and I stood on the lower rungs of the ladder, Balderston swung himself up among the suspension ropes of the car and began ripping into the great canvas bags which held the stores. Soon he came upon a quantity of heavy articles such as he thought we could best spare, and he cast out enough to raise Thord and myself five or six yards clear of the floe.

"All right. Come aboard," he called, and we scrambled hurriedly up the swaying ladder. With a shout, we clambered in over the bearing-ring and stood beside Black on the little platform, staring up at the great sphere of varnished silk and the confusing network of rope and cord. Neither Thord nor I had ever before been in a balloon, and we felt like fish out of water. Fortunately, however, both Balderston and Black had seen no little service in the army captive balloon manoeuvres, and were therefore better acquainted with aeronautics. Balderston was almost wild with delight. The moment we climbed aboard he cast over enough ballast to lift us fully thirty yards above the floe.

"All's well, boys!" he shouted. "It's a fair northerly breeze. We've only to let go and start on for the Pole!"

"Good-bye to the floe! We won't miss it! Let her go, Black," I cried.

"Done, sah!" shouted the sergeant, and he cast loose the anchor line.

"Hurrah!" cried Thord. The balloon had bounded forward like a hound from the leash. But our joy was short-lived. Checked by the weight of the two remaining lines, the balloon careened dizzily and swooped down into the very midst of the hummock crests.

Thord, with a sailor's quickness, leaped to the guide-rope bar, whirling an ice-axe, while Balderston up above slashed the lashings of a storage bag. Neither was an instant too quick. The car was dashing straight against the green crest of a hummock. I braced myselffor the shock. In another instant I expected to find myself whirling down upon the floe. Already I could hear the clash of the collision--when, in the snap of a finger, the ice crag dove beneath us and vanished. After it flashed the bag cut loose by Balderston. I saw the horizon begin to rise and widen, and the floes below us seemed to be falling into an immense basin. Even as I looked, the illusive sinkage became more swift, and I caught a glimpse of a slender object that whipped down through the air below the car. Then I understood. Thord had cut loose the second guide-rope before Black could interfere. We were ascending like a rocket.

Up, up, up we shot, balloon and car revolving like a bauble on a twisted string. We no longer gazed down on the falling ice world. We could only cling fast to the ropes and long for the whirling ascent to cease.

At last the seeming downward rush of air slackened, and the car revolved more slowly. But when, dizzy and gasping, we turned our eyes to the barometers hanging on the suspension ropes, the indicators already pointed to an altitude of five thousand feet.

"Where is the valve-cord?" I cried. "Quick, Frank, open an escape valve!"

"No, no," he replied. "The ascent has stopped. Wait--what wind have we?"

"North!" bellowed Thord. "We fly due north, in the heart of a gale! See, the floes are sweeping beneath us like driving clouds."

"Fast express for the Pole!" shouted Balderston, and he swung down to join in the general handshake.

After the first whirling and swaying of our ascent, the balloon became perfectly steady, and swept along in the super-terrestrial hurricane like a bubble on a placid stream. We had only to close our eyes to imagine ourselves motionless on solid earth and in a dead calm. Relatively speaking, this last was indeed true; for swift as was the air-current in which we floated, it bore the balloon along with equal swiftness, so that to us there was not enough breeze perceptible to flicker a match flame. Yet, gazing down ward from our lofty height, we could see ourselves driving along at arrowy speed above that terrible ice pack whose hummocks and crevasses had put us to so much vain toil and hardship.

The thought of thus attaining in a few short hours what we had failed to win by months of strenuous exertions, keyed our spirits up to the highest pitch. Careless alike of cold, of hunger and of thirst, we stood immovable on the little platform, our eyes fixed steadfastly to the north. Mile after mile, the great ice-pack below glided away to the southward, while before us new stretches of the glittering waste rolled up above the distant horizon.

Hours passed--still we soared over the vast ice-world, cold and rugged and desolate as a lunar landscape. The winding lanes of blue water had long since disappeared, and nothing was visible to our straining eyes but the huge vault of heaven above us, and below, the illimitable fields of palaeocrystic floe-bergs.

Hunger at last roused the sergeant to action. He slipped down through the man-hole into the car, and in rummaging about, discovered an arrangement for swinging a little stove below the car's bottom. Presently the rest of us were drawn from our fascinated watch by a delicious aroma that wafted up around the car.

"Coffee!" cried Balderston, and all three of us sniffed the odour with an eagerness sharpened by months of abstinence.

"Black is cooking!" I exclaimed. "Think of eating civilised food again!"

"It makes my mouth water," said Thord. "Hurrah for the sergeant!"

"Ay; for at last he is doing something, while we stand here like fools," replied Balderston. "There must be instruments aboard, John, and it's high time we began taking observations."

"True enough," said I, and our idleness gave place to hurried action. As was to be expected, we found the balloon well provided with nautical instruments, and together we sought hastily to determine our latitude, our hearts beating with feverish anxiety.

"Half a degree beyond Nansen's farthest!"--we could scarcely credit our own words. Yet there was the calculation in black and white, plain before our eyes. All that the "Fram" had won by months and years of northward creeping, our balloon had covered and outstripped by a few short hours of eagle flight,--and still we swept on northward towards the great goal.

As the full realisation of our good fortune dawned upon us, we whirled our woollen caps overhead and yelled like madmen. Not until Black popped up from the car and set a savoury meal under our noses--and even then not until our hunger overpowered us,--did we cease shouting. After months of famine and raw meat, however, even the Pole itself could not long have kept our thoughts from Black's steaming dishes. We fell to upon them like savages, and no one stood on the common decencies of etiquette.

Each devoured what first came to hand, and the meal ended only when the dishes had been scraped.

As the last morsel disappeared in Thord's cavernous mouth, Balderston turned with a sigh of contentment, and took up the binoculars. Leisurely he leaned upon the bearing-ring and raised the glasses to sweep the horizon. From northeast to north they turned. Suddenly they stopped, and I saw Balderston's lithe figure stiffen as though he had received an electric shock. Then he whirled about, his blue eyes and fair face beaming like a bride groom's.

"Land ho!" he yelled.

In an instant we were beside him, striving to see with the naked eye what was barely discernible through the binoculars. Realising this, I reached for the glasses.

"What's it like?" I demanded.

"Black and cloudy."

"It is a cloud! I can see it change shape. If that is your land--"

"Look at the lower edge."

"The lower edge?--A-h; mountains! I see them well now, with the dark background. Not large--but they can't be ice. They stand too high above the horizon."

Thord took the glasses and gazed long and steadily. When at last he handed them on to Black, he spoke with conviction "Never before have I looked at land so far; yet doubtless those are fells or jokuls. The black cloud is smoke from a burning jokul beyond."

"A volcano!"

"Why not?" said Balderston gleefully. "Think of warming our toes at a crater on the Pole! Now, old boy, we'll soon see what's what."

"Ay; and see about Jarl Biorn," muttered Thord.

"Jarl Biorn--what of Jarl Biorn?" I asked.

"Have you never heard the saga of Jarl Biorn and the storming of Jotunheim?"

"Did Snorre Sturleson write of him?"

"No, but my father had a very old writing in Runic which told of him. He was a jarl outlawed from Norway about the year 925. He came to Iceland, and organised a large expedition to colonise the fair land which, Biorn said, they should find by sailing due north. They thought that by storming the icy walls of the frost giants they would come to a rich and beautiful country."

"Did they turn back?" asked Balderston.

"Not one of all the ships that sailed. All vanished into the north, never to return."

"The first Arctic explorers. Poor fellow they head a long list of victims.

"Perhaps; and yet, Doctor Godfrey, is it not possible they may have escaped? All the early writers agree that the Icelandic climate was far milder in the tenth century than now. The East Greenland pack did not then exist, as it does to-day. I believe it possible that such bold and hardy sailors could have crossed the Polar pack even this far north, and if that land is habitable, we may find their descendants living about the Pole."

Balderston and I roared with laughter at this absurd fancy, and the lieutenant replied flippantly: "We may find white Biorn, Thord, warming his toes; but I have my doubts of any Biornsons."

"That is to be seen," the giant coolly rejoined. "I'm glad you two are well versed the Eddas. Biorn must have sailed before Christianity reached Iceland, so no doubt we will find the colony's descendants still worshippers of the Asir."

"I differ with you there," said I. "If we find them at all, I bet we find them--well packed in ice."

"As some one may find us a few centuries hence," suggested Balderston.

"Ugh-- don't mention it!" I exclaimed. "The mere prospect of stalking about over the Pole is chilly enough for me."

"On the contrary," said Balderston, "that prospect is warming to me. To think that a few short hours will bring us to the Pole!"

"Ay, or past it," replied Thord. "Another observation wouldn't hurt."

"True. Frank will see to it, while Black and I take stock of the balloon's stores."

With no little caution, the sergeant and I drew ourselves up among the suspension ropes and began overhauling the great storage sacks. Our work in such a position was of course hurried and cursory, and we had dropped down again upon the platform, when Balderston announced the result of his work.

"Eighty-seven degrees!" I repeated--"eighty-seven degrees!"

Then Thord's deep voice rolled out in triumph: "Skoal, skoal to our Skidbladnir! She's truly an Eagle! Five hours more will bring us to the Pole."

"Hurrah! We's gettin' dah. Jes' see dem mountings grow!" shouted Black.

We turned to look. Already the mountains were visible to the naked eye, being distant about a hundred miles. The glasses showed that they formed a jagged chain of peaks, somewhat higher at the east end, and trending off to the left until lost in the iceblink. Over their crests, and backed by the black volcanic cloud, appeared a broad white plain, but whether a snow-covered plateau or a cloud-bank we could not at first determine. Minute after minute, however, the view became clearer, until Thord at last declared that the white plain was a sea of fleecy clouds, floating at an elevation somewhat higher than that of the mountains.

"Looks like a warmer temperature beyond the peaks, judging from the appearance of the clouds," observed Balderston, when the glasses passed around to him.

Thord's big face lighted with sudden humour.

"No doubt it's Paradise we're coming to," he said. "Some of you scientific fellows say that man first came from the north."

"Well, it may be the Garden of Eden," replied Balderston smilingly; "yet I look more for the other place,--fire and brimstone--a big crater, you know."

"We may find both," remarked Thord in a serious tone. "It may be the Niflheim of our heathen ancestors."

"Don't talk crazy!" said I. "All we'll find would pass for Iceland in winter dress."

"Maybe!" retorted Thord. "At any rate, we'll find nothing if we keep at this altitude. Beyond the fells, that cloud-sea blankets the whole earth. We must dip beneath if we wish to see anything."

"True," said Balderston; "and yet that would likely bring us into a cross-wind, or even a counter-current."

"We might try it," I replied. "If the wind is wrong, a sack or two of ballast will bring us up again. Being so near the Pole, we can well spare the gas and stores to survey this terra incognita. What do you say?"

"You're boss, doctor," said Thord laconically.

"Well, Frank?"

"All right. It will give us a chance to christen our discovery. I suppose there is no champagne aboard; but no doubt I can rummage out a bottle of brandy."

"Will we Ian', sah?" asked the sergeant, who was already making arrangements for his next culinary triumph.

"Land?--Well, it is possible," I replied.

"Any Apaches up dis way, sah?"

"Hardly."

"Ay; but my Biornsons may have run wild," put in Thord, with his broad grin.

"Den I'll look to de guns, sah," said Black, taking the matter seriously. Without a moment's delay, he started in to inspect and load the guns with the utmost care. Thord and I grinned at each other, but we did not interfere. Neither of us expected to come across even the amiable Esquimo here in the heart of the Polar world; but we did look for white bears and Polar wolves.

Every minute of the balloon's swift flight was now bringing out to our view the details of the Polar range. Already the white slopes and wind-swept peaks stood out clear to the unaided eye. Beyond the first ridge, however, the veiling cloud-banks and the great black pall of volcanic vapours still concealed all that lay beneath. Only the ragged peaks and crags of the range, rearing up a thousand feet above sea-level, stood out intensely black against the snow, and Balderston presently declared that they were basaltic.

"But what will the Pole be, lieutenant?" asked Thord in an anxious tone.

"The Pole?--Oh, the Pole is a shaft of pure gold, seventeen feet three inches high, with a nice place on this side for us to cut our names with our penknives."

"Am dat really true, sah?" cried Black, his eyes bulging.

"True as the world is flat," said I. "Unfortunately, gold is so heavy, we will be unable to carry any away with us."

"Besides, sergeant, the earth might get to wobbling, if we took off the end of its axis," added Thord.

"Some folks's tongues is wobblin' now," muttered Black, as he saw the Icelander's blue eyes twinkle. "We'll see no gole pillows dis side Johdan."

"`In the sweet fields of Eden--that's what we're coming to now," rejoined Thord.

"We're coming down, at any rate, and pretty soon, too," said I. "Get some ballast handy, in case of accidents. Frank, you can look to the valve, seeing you have run balloons before."

"All ready, whenever you say go," replied Balderston, and he took the cord of one of the escape-valves high up on the balloon's side.

"Ten minutes from now should bring us down just short of that long ridge," observed Thord.

"In ten minutes then," said I, and with quickened pulse, we waited the moment for our return towards Mother Earth. Eagerly we stared down upon the serrated peak crests while the last few miles of icefield glided beneath us. Six miles--five--four--three--two--

"Let her go!" I shouted.

I saw Balderston tug at the valve cord. Almost instantly a little gust of air fanned my face, like the waft of unseen wings. I hastened to gaze down over the bearing-ring. We were sinking--falling--with startling rapidity. It seemed as though some buried Titan was heaving mountains and floes alike swiftly upwards into mid-air.

Even Thord, fearless as was his nature, could not stifle a cry of alarm. But I found assurance in Balderston's cool bearing. Cord in hand, he gazed over at the upheaving mountains, with no other expression on his handsome face than quiet curiosity. Yet he was none the less fully alert to his duty, as I could see by his quick glances at the barometer before him.

Down, down we plunged, until Thord shouted that we should be dashed on the hummocks.

"Steady--steady!" commanded Balderston, as the Icelander heaved up a sack of ballast, and with that he closed the valve.

"You've dropped us too far!" I exclaimed, turning from the hummocks, in appearance so perilously near the car's bottom, to the mountain crests, which seemed to tower far above our level. But our eyesight was deceived by the sudden descent from the great altitude. Balderston only laughed at our dismay, and, after a little pause, held his barometer out to me.

"See," he said, "twelve hundred feet."

"Twelve hundred inches!" muttered Thord, and we stared down again at the hummocks. But already our eyes had begun to adjust themselves to the altered perspective, and we realised that Balderston was right. The balloon's descent had terminated at an altitude between eleven and twelve hundred feet.

The next question was the direction of the wind at our new elevation. Thord was first to answer it.

"Good," he said, closely eying the ice pack beneath us. "Our luck still holds--about a ten-knot breeze, bearing us towards the left end of that long ridge."

"We will just scrape over the crest," remarked Balderston; "then, clear sailing. I see no other range in below the cloud-bank."

"Those under mists obscure the view," I replied. "But if they hide any loftier peaks, we will have ballast ready, and can rise. If I'm right on the compass variation, we are heading only a little west of north, and the breeze is moderate enough to allow us a good view of the country in passing."

"Reglah 'commodashun train to de Pole," observed the sergeant, no less elated than the rest of us.

"Right you are, Black," replied his lieutenant. "But Station No. I is only a siding. I will heave out my brandy bottle, and we will not stop unless there are passengers."

"Better get your bottle ready," said I. "If it is the ridge you are calling your station, it is not over three minutes off--and you have a new land to christen."

"Don't worry; I have both liquor and name ready. But the honour should be yours, John."

"Too late," I replied, waving aside the brandy flask. "I couldn't think up a name in a week. Another minute, and we'll be alongside that top ledge--thirty feet clearance--just nice and handy for your throw."

"Ay; but hold on, lieutenant," cried Thord. "Give me a pull at the good stuff before you waste it."

A smile flickered across Balderston's face, only to give way to deep gravity. He raised the flask in his right hand, and at the moment we were about to cross the ridge, his voice rang out clear and solemn: "In the name of the United States of America, I take possession of this land; and I name it--Polaria!"

With the word, out whirled the flask of liquor, and all eyes turned to watch its flight. Out over the crest ledge it whirled, and we listened expectantly for the crash of shattered glass,--a crash which never came. Instead, our ears rang with a bestial howl, and up from the hollow where the bottle had fallen leaped the figure of a savage,--naked, squat, hairy, with the face of a gorilla.

For a moment the creature gaped at us in stupid wonder; then, with a yell of rage, he snatched a stone from the ledge beside him and hurled it at the balloon. The sack might as well have been tissue paper so far as offering any resistance to the missile. Through the lower bend the flint tore its way like a rocket, whirling out on the farther side with undiminished velocity.

But the injury did not pass unavenged. As I craned my neck to stare upwards, aghast at the havoc wrought, Black clapped a rifle to his shoulder and fired. The savage, who had stooped for a second flint, leaped high in the air and pitched forwards over the cliff. His death-shriek mingled with the echo of the shot, which came up from the mountain slopes like a thunder-clap.

"Huh--Apaches!" grunted the sergeant, and he slipped a fresh cartridge into his rifle.

"Apaches? Bah, worse!" cried Balderston, staring back at the brown, misshapen body on the snowy slope. "Makes one feel queer; eh? Lucky you took him so quick, Black. That stone fairly sizzled--a second, better aimed, might have done for one of us."

"Better aimed!--You say that, with those great rips in the balloon!"

"Don't worry, John. The holes are not so large as you fancy, and after the gas we've let out, they are too far down for much more to escape."

"Ay; we're sinking,--but as if we were in jelly," said Thord. "We can make an easy landing across this big hollow, on yonder slope. The friction of the guide-rope is already slackening our speed."

"Yet it will mean a big bump, unless we rig an anchor," said Balderston.

"Didn' fin' no ankahs. Yoh mus' hab cut dem loose, sah. But dah's plenty ob rope."

"Yes, here is a thirty-fathom line," I added. "With a sack of ammunition to catch in the rocks, it will be just the thing. There is another question, though--how about more savages? What a brute--"

"That's the word!" cried Balderston. "Why, the creature could have posed for a pre-glacial caveman. See any more, sergeant?"

"No, sah. Single track up de snow to de ledge. But dah might be a whole tribe ambushed ober in dose rocks, sah."

"If so, we'll have to clean them out, that's all. The balloon must be landed in one of the drifts between those rock heaps. We shouldn't waste any more ballast or gas than we can help."

"Drag is ready, such as it is," remarked Thord.

"Stand by, then, you and Black," I ordered. "Frank can manage the landing. Look to him for directions. I will keep watch for savages."

Placing both my express and Balderston's army rifle beside me, I took up the glasses, and as the balloon slanted down across the hollow, I scrutinised every rock and depression within a radius of half a mile. To all appearances, the slope was devoid of life, but I maintained my outlook with the closest attention. For all I knew, every heap of the frost-split basalt blocks might conceal a score of bloodthirsty beast-men. Having encountered one hyperborean on these Polar .Alps, it was not unlikely we should see more. I stood with down-pointing rifle as the balloon glided a few feet above the first outcropping ledges.

"No enemy!" I cried; but my sigh of relief choked short--we were drifting straight upon a second rock heap. Though checked by the friction of the guide-rope, our movement was yet swift enough to dash the car in flinders on the sharp edged basalt cubes. But already Thord and Black were lowering the drag. At the right moment Balderston gave the word to let go, and the balloon, relieved of the weight, bounded upwards.

"Steady now, steady," exclaimed Balderston, gripping the anchor line with Thord and Black. "Pay out--pay out, I say, else the jerk will snap the line, or pull us overboard. Good! it's caught fast. She's coming to. Now, hold her!"

Only Thord's giant strength saved all three from going overboard during the final tug; but somehow or other, our aerial craft was snubbed without too severe a jerk, and the last fathom of the anchor line was at once knotted to the bearing-ring. "Well done!" I exclaimed.

The balloon, lying over before the pressure of the breeze, swayed gently from side to side above promising snowdrift. At once Balderston drew himself up above the bearing-ring, and, securing the necessary materials, climbed into the netting to mend the holes torn by the stones. We watched him until he was at work on a patch for the hole to windward. Then we divided our time between eying the nearest ledges and gauging our descent upon the snowdrift.

Steadily but gently we sank as the leaking balloon sagged under its load. The loss of gas was now very slow, and it was some time before the car's bevelled bottom broke through the crust on the drift and settled in a bed of the loose dry snow beneath.

"At last," said I--"we have arrived!"

"Yes; thank heaven!" answered Thord. "This plaguey car is cut too small for me. I'd as soon be a sardine for the trip back. I've just been longing for a good stretch, and here goes," and he laid hold of the bearing-ring to vault out.

"Stop!" I yelled, none too soon. The giant paused, surprised. Then the truth flashed upon him, and he glanced quickly about at the barren slope and then skyward.

"Thank you, doctor," he said huskily, his face a shade less ruddy than usual. "This is not a pleasant station to stop at alone--with a horde of my Biornsons, like as not, sunning themselves on the peaks around."

"Yes; I'm afraid we must keep you snug aboard. Better a cramp than a freeze."

"That's all right for you who can stretch out on the platform. I'll have to dangle my legs through the ropes. I'd give anything to stretch them on the ground."

"Huh--pull de rope inboa'd den."

The solution to his difficulty was so simple that Thord paused to kick himself before laying hold of the guide-rope. Black and I took the line behind him, and, hauling together, we soon had the platform full of the coils.

"Hold," I said. "We certainly have enough aboard."

"Not yet, doctor. Black will want out, to use his stove. He can't light it here so near the balloon's neck; but we might as well have a meal while we wait here."

"Shuly, sah," assented the sergeant.

"How are you making out, Frank?" I called. "Will you be much longer?"

"Just finished one,"-came the cheery reply, and Balderston swung down to pass under the balloon's neck and ascend to the opposite hole.

"You're in for a tough job now," remarked Thord.

"Sure!" replied Balderston, and clinging to the netting cords with hands and feet, he climbed up and out under the overhang of the great sack. It was a feat to make a sailor dizzy; but the lieutenant reached the hole in safety. Hooked fast in the netting, he hung suspended head down, like a fly on a swaying ceiling, and started in on his half-hour's job with serene assurance. The danger and difficulty of his position only served to stimulate his venturesome spirit.

"What a man, doctor! You couldn't find many to whistle while head down."

"You would growl, either end up, eh?"

"So would you, with this cursed rope. It catches back there."

"'Nuff boa'd now foh you."

"Ay--but yourself, Black?"

"We don't want any more coils inboard. There's hardly room to stir now. You get out, Thord, and fetch some of those basalt blocks. Four or five would let us all out."

"All right," said the Icelander, and swinging over, he let himself down knee-deep in the drift. But he held cautiously to the rim of the car, lest we should have miscalculated the weight of the guide-rope coils. Greatly to his relief, the car merely stirred in its bed, and he at once left it to wade through the snow to the nearest rock heap. Swinging up with ease one of the square black cubes that could not have weighed less than two hundred pounds, he waded back and laid it on the platform. A second, no less weighty, was soon placed beside the first. The task was mere child's play for the Icelander's giant thews. Without a moment's pause, he turned to fetch a third stone.

"Out with your stove, sergeant," I ordered, and Black was overboard and had his stove blazing on the nearest ledge before Thord brought my release.

"Ho, doctor!" exclaimed the giant. "This is jolly work to stretch the muscles. I'll fetch one more stone, in case the lieutenant wants to get out; then I'll go and free the guide-rope. It's caught in between the rocks."

"Yes, we must keep it. Though to ascend again, we will have to cast out a lot more of the stores."

"Not a funny thing to do this side the Arctic Circle, doctor,"--and Thord looked about at the desolate waste of snow and rock with a grim smile. "We might make a virtue of necessity, and say that the stuff we leave is wergild to the Biornsons for the death of their solitary chief."

"Very likely the white Biornsons will be the first to find the goods. But, seriously, I hope neither bears nor savages come this way. If we leave food here, it may prove invaluable to us on our return south, should anything happen to the balloon."

"Perhaps we will not return south."

"Well, that's true. Yet, between balloon and wind, Fortune has favoured us marvellously so far; and while I admit that many an Arctic explorer has perished--"

"I didn't speak of perishing. We may stay here alive," rejoined Thord, and with a jerk of his thumb northwards, he strode off down the slope. I smiled upon his great back, much amused by the absurdity of his remark. It was true that this Polar land was habitable--that was proven by the presence of the bestial savage. But who would choose an Esquimo existence?--Still smiling, I waded through the snow to the sergeant, drawn by the savoury odour of his cooking. Black had been more than half a chef when some scrape caused him to enlist in Balderston's regiment. The meal he was now concocting promised to do full justice to his reputation.

I was teasing him for a taste of his half-cooked stew, at the same time listening to the lively tune by which Balderston announced the wind-up of his task, when the gay whistling abruptly stopped in the middle of a note.

For a moment all was silence--the dead, cold silence of the Polar waste. Then, ringing down the slope against the breeze, came a high-pitched musical cry, such as only a woman's throat could utter:

"Haoi--a-o--haoi!"

At first I could not see anything. It was otherwise with Balderston, who shouted something in an astonished tone, and swung down the netting with reckless haste. Puzzled and alarmed, I followed Black, who, with a soldier's instinct, dashed instantly for the guns. As we floundered through the snow, I heard Thord's deep voice roar out a word that sounded like "Biorn," and a side glance showed him coming up the slope at a tremendous pace. Over the rocks and drifts he bounded like a deer, but he was not making for the balloon.

"Biorn! the Valkyr!--Bring the guns!" he roared, and cutting across our tracks, he rushed on up the slope. Breathless with excitement, I leaped to the side of the car, where Balderston and Black stood staring up the mountain-side. I stared also, expecting to see a second brute-man. Yet the halloo and Thord's shout might have forewarned me.

Instead of the savage my fancy had pictured, I saw bounding toward us down the slope a creature beautiful as a Norse goddess. It was a girl, tall and fair, in the costume of a huntress, and she was running as though for life. Dumfounded, we stood gaping beside the car, while the maiden sped swiftly over a stretch of bare rocks. Suddenly she flourished overhead a long lance, and repeated her strange cry, "Haoi--a-o--haoi!"

"An attack!" I gasped.

"Hardly--I--"

"De guns!" shouted Black, and then all saw what Thord had meant. Up from a hollow behind the girl loomed a shaggy grizzled beast. It was a bear, larger than any polar or grizzly I had ever hunted.

"Curse that twist!" cried Balderston, and snatching his rifle, he limped forward to kneel behind a ledge. He had his rifle sights up as Black and I spurted past him. And it was none too soon. I could see the huntress struggling across a broad drift, through which the bear ploughed a path without the slightest hindrance. Thord was yet many yards distant.

At first girl and bear were so directly in line that Balderston could not fire; but when the girl leaped from the drift out upon a bit of rocky ground, she swerved a little to one side and faced about, too hard pressed to run farther. Down went the lance butt against a stone, and the girl bent forward, one knee upon the shaft, to meet the onrushing brute.

Already the monster was at the edge of the drift, when I saw him spin around in his tracks and roll sideways. The crack of Balderston's army rifle told me the cause. But the beast was up again, like a cat, and charged upon the spear, with a roar of fury. Again Balderston's rifle rang out--once, and then three times more, in quick succession. The bear kept on--and the rifle was empty!

The ground reeled before me as I ran, and I uttered a frenzied cry. I flung myself down to shoot, but was far too shaky to aim straight. Black was staggering in my wake, more breathless and spent than I. Thord still lacked fifty yards of the bear, and he had no weapon. For all we could do, the girl's fate lay in her own hands. Gazing over my wobbly rifle barrel, I saw her poised like a statue, her lance pointed straight at the beast's shaggy breast. It was a wonderful sight--that bright, graceful figure, so still and resolute, awaiting the shock of the furious monster.

Great as were the odds, my hopes rose at sight of the girl's courage. Should she gain but ten seconds of respite, I knew I could kill the beast. The range was not great, and already my hands were steadying. Yet it was not to be.

Straight upon the levelled spear charged the bear, and at the instant the point pricked his breast, he struck nimbly at the shaft. Away flew the splintered wood, and I looked to see the girl fall forward into the monster's jaws. I could fancy the sickening crunch of bones as the great fangs mangled her white flesh.

But I had failed to estimate the girl's skill. Quick as was the blow that broke the lance, she sprang back like a flash, and plucked from her side a short-handled axe. Up went the weapon in a sweeping circle, and I saw the beast stagger as it whirled down upon his skull. Well he might--the blade shore through hair and skin and bone to the very brain cavity. Fearful as was the wound, the beast reared up and struck a blow in turn that swept the girl from her feet. She fell in a drift, five yards away, and lay maimed, helpless to save herself.

The beast turned to rush upon his victim. I gasped--then shouted wildly. A sixth shot from Balderston had pierced the beast's foreleg, and it gave a moment's delay. I drew a deep breath and raised my rifle. With one shot I would end the matter.

But my chance was gone. Thord, running on like a madman, leaped between me and the bear. Straight upon the beast he rushed in reckless fury, empty-handed but utterly devoid of fear. What followed was the grandest feat I had ever seen. The bear reared up, with a terrible snarling roar, to confront this new foe; but the giant Icelander leaped on without a falter.

Suddenly he stooped, not six paces from the grey beast. I saw him clutch downwards--then up he straightened and swung high overhead a massive block of basalt. Forward hurled the great stone between the threatening paws, driven by all Thord's giant strength and the momentum of his rush. The beast, monster though he was, went down before that missile like a cardboard puppet. There was no need of a second blow.

When I came up, on a run, the iron claws were still feebly beating the air; but it was the beast's death throe. One glance I took at the massive limbs, waving spasmodically above the shapeless mangled bulk--and I knew I beheld the cave-bear of the Stone Age--Ursus Spelaeus, the terror of early man.

But my thoughts flashed from the dying beast to his victim. I sprang past him to where Thord was lifting the girl from the snow. The moment I looked at her, I saw that Thord's Biornsons were not a myth. The girl was as purely Norse in type as Balderston himself. But the impression of her appearance that I had received from a distance fell far short of the reality. Her lissome figure, nearly six feet in height and beautifully proportioned, was well set off by the huntress costume,--buskins and leggins of otter skin, an ermine blouse, and knee-skirt of blue fox. Her golden-yellow hair was plaited in two heavy strands and crowned by a round ermine cap with scarlet wings.

But it was the girl's face that held my gaze. I had seen beautiful women of many nations, yet never one whose beauty so much as compared with the clear-cut features and exquisite colouring of this Polar Valkyrie. I must confess that for a moment I stood and stared at the girl like a country gawk.

Then she looked wondering at me with eyes of the deepest, tenderest blue, now misty with pain. I could see them widen with a sort of awe; but they showed no sign of fear,--only a wordless appeal for aid. At that I found my wits, and hastened to look to her injuries.

The bear's chisel claws had ripped through the left sleeve and down her breast, and already the white fur was streaked with red. Worse still, the injured arm dangled loosely about as Thord raised the girl to her feet. Though she did not cry out, I saw her face contract with agony.

"Bone smashed, Doctor Godfrey," explained Thord, his rough voice strangely softened. The girl started at his words, and bent forward beseechingly.

"Ah, good Frey, help me!" she cried.

So like the Icelandic was her language, I understood every word. I had expected as much. But I was surprised at the name the girl gave me. Clearly, she thought that Thord had addressed me as the Vana-god, a supposition strengthened by the presence of the balloon, which no doubt she had already taken to be Frey's cloud-ship Skidbladnir. Under the circumstances my godhood was very apt, for Frey was the healer.

"Take comfort, maiden," I replied in Icelandic. "Your pain will soon be eased."

As I spoke I drew open the tattered blouse to examine the wounds. At my touch, however, the colour, which was fast leaving the girl's cheeks, came back in full flood, and she shrank from me.

"Go on, doctor," growled Thord. "It's no time for squeamishness. Her bodice is already full of blood."

I shook my head. The look in the girl's deep eyes compelled me to respect her modesty. I pointed to the balloon.

"You must carry her down," I said, and I waved to Black, who had regained his wind, and was trotting up to see the bear.

"Run down, Black," I shouted. "Hot water and chloroform--lieutenant knows."

The sergeant turned on his heel, saluting in the act, and started double quick down the slope.

"Ready," said Thord warningly, and his voice softened again as he dropped into Old Norse--"Now, maiden, I bear you to Skidbladnir to be healed. There is naught to fear."

Reassured by his tone, the girl made no attempt to shrink from him, and he lifted her in his giant arms like a child. I took my place beside him, to hold the broken arm, and we walked as rapidly as possible down to the car. There she was lifted gently in upon the couch of furs that Black had spread on the platform, and she lay gazing about in awed amazement, while I made my hasty preparations for the operation.

The sergeant already had his kettles full of melting snow, and, best of all, Balderston, up among the stores, rummaged out a surgical case. A moment later I had it down beside me, and was opening a half-pound can of chloroform. With it I turned to the girl, whose white face betrayed the acuteness of her suffering.

"This is a sleep-charm, maiden," I said, again in Icelandic. "Do you fear?"

For answer, the girl looked at me with the utter trustfulness of a child, nor did she shrink when I held the drug-saturated cloth to her face. Steadfastly the deep blue eyes gazed up at me, full of mingled awe and faith, until the life within waned and the long lashes drooped with the coming sleep. A minute later she was fully under the influence of the drug.

"Now," I said, "I want Thord. The rest can go to see the bear."

Thord promptly ran to fetch the hot water, while Black and Balderston set off up the slope. By the time Thord returned, I had everything ready.

"Come aboard," I directed. After you chuck out those rope coils, I want your help with the lint and sponges."

"I know, doctor," replied the Icelander, and his ready aid showed former experience. Before starting to throw out the guide-rope, he thrust a pair of scissors into my hand. With a few snips, I laid open the girl's tattered blouse and bodice and the eider-skin chemise beneath. Another cut bared the round white arm. Greatly to my relief, the fracture proved to be simple, and was easily set. There were splints in the surgical case.

The bandaging I completed with the utmost haste, for the long gashes torn across the girl's snowy breast and shoulders were still bleeding freely. This was the only danger, however, as none of the wounds penetrated the chest cavity. While Thord bathed them with hot water, I plied my needle, and between us we soon had all the cruel gashes stanched and closed. The whole had not taken fifteen minutes.

As I applied the dressings and stitched together the tattered garments, Thord signalled the others to return.

"She's coming to already," he said. "When she can talk, we all want to hear, and consider what lies before us...Think of it, doctor Only a few short hours ago on that cursed floe--and now, at the very threshold of the Pole--and--and this! What next?"

I did not wonder at Thord's outburst. But with me a softer emotion had overcome this excess of elation and amazement. Heedless of all else, I sat watching the bloom creep back into the rounded cheeks of my patient, fascinated by the beauty of her features and the colouring of milk and roses.

Presently the blue eyes opened and looked about dazed wonderment. Then they met my gaze, and at once grew radiant with gratitude.

For some time the Polar maid and I gazed at each other in mute wonder. But Thord at last thought to fetch a cup of coffee. The stuff had been boiling so long that it was thick and muddy; yet when I raised the girl's head and held the cup to her lips, she drained it like an obedient child. No doubt she thought the hot, bitter draught some kind of powerful medicine, and indeed it had the effect of counteracting the lingering stupor of the chloroform. Before I could prevent her, she sat up, the movement twisting her arm and shoulder so severely that she was unable to restrain a cry of pain.

"You must keep still, maiden," I exclaimed, and I hastened to adjust the sling for her arm. As I drew back, a sudden sense of awe seemed to overcome her, and she bent her head reverently.

"Lord Frey is very gracious," she murmured. "He acts the Holy Rune."

Before I could reply, Balderston came up, limping from the twist that had aroused the old sprain, but full of cordial greetings for our guest. Forgetful alike of her pain and her awe, the girl smiled back at him. Then she chanced to glance around at Thord's giant figure, and her eyes widened.

"Biorn's bani!--hail to the Son of Jord!" she cried, and bowing to each of us in turn, she murmured in a voice scarcely audible--"I give greeting to the skyfarers. The Asir are welcome to Updal."

"You over-honour us," replied Balderston, smiling. "We are men, not gods."

The girl looked about at us and up at the balloon in bewilderment. Then she thought she understood.

"It is Skidbladnir," she said, nodding to herself--"Skidbladnir; and the Lord Frey has bound my hurt. Yet the sagas tell of like comings, and if they wish to pass as men--"

"She bowed again to us.

"The wanderers are very welcome," she said.

"And who is it greets us?" asked Balderston.

"I am Thyra Ragnersdotter."

Thord took off his sealskin cap and stood with the sun gleaming on his fiery hair and beard.

"Maid Thyra," he began in his deepest voice, "I am Thord, son of Vegtam, son of Bor. This fair one is called Frank Balderston, and beside you stands Jan Godfrey."

Not a word of this introduction was untrue, but if Thord had calculated to confirm the girl's belief in our godship, he could not have done it more effectually by an outright lie. To her ears, my name no doubt sounded like Vana-god Frey, while the other names seemed but thin disguises for Thor and Balder. I perceived the awe deepening in the girl's eyes, and cried indignantly: "Shame on you, Thord, to trifle with her!"

Thord grinned, highly amused--"Why, doctor, you don't believe she really--"

"Where are your eye? Between the balloon and our looks, and the way you gave our names--"

I dropped English, and turned abruptly to the wondering girl: "It is a jest, Thyra. We are only men--men of like blood to you, descended from your early ancestors in the south land."

The girl opened her lips to reply; but a sudden look of horror distorted her face. Clutching my shoulder, she drew herself behind me and shrieked in terror: "Surt!--fiery Surt! Oh, save me, Frey!"

I stared about in amazement. Sergeant Black, who had loitered by the bear, stood a few paces off, puffing at a cigar and evincing his enjoyment by one of his grotesque grins. We all laughed as the situation dawned upon us, and I took the girl's hand, with a reassuring look.

"Only consider, maiden," I reasoned; "would Surt fare in peace with the Asir? We are all merely men--he also. He is a true carl, despite his colour. His forefathers came from a land where the sun burns men black."

"The dwerger are more ugly," said the girl, panting and still half alarmed; "yet they are brown. He is so black, I thought it must be Surt; and--and he breathes fire--the smoke-!"

"A small wonder--only smoke," said I. "We will show you the mystery soon. But now, tell us,--is it often you hunt grey biorn alone?"

"The others follow the trail of bera and the cubs. I crossed the blood snow to cut them off; but biorn rushed upon me. Few can fight grey biorn singly. I fled to seek my brother. From the crest I saw Skidbladnir and ran towards it for aid. I was hard pressed. But for the thunderstones you cast so far, and the huge rock hurled by this great one, I should have been fey."

"No wonder!" commented Balderston. "What did he measure, sergeant?"

"Muns'ous big, sah--muns'ous big! Ten feet, shuly!"

"Not ten of your own feet!" protested Thord.

"No, sah; no, sah; I doan say dat, sah. Only seben ob dem."

"Yes; I didn't think he was quite a whale," said Thord. "But hustle out your knives. We want that skin."

"No we don't," said I. "The thing will weigh two or three hundred, and with our fair passenger, we'll have enough aboard. Leave the bear alone, and help consider what's to be done next."

"No time for that either," interrupted Balderston. "Look there!"

All followed his gesture up the slope to the right. Five hundred yards or so away, a man had leaped up suddenly above the sky-line. For a moment he paused on the bare crest of the ridge, to gaze back down the opposite slope; then, with a defiant shake of his lance, he turned and bounded towards us.

"It is my brother, Rolf Kaki!" cried Thyra, and she sent a clear "Haoi!" ringing up the mountain side. The man flung up his hand in response, and came on faster than ever.

"Hello! That looks like flight," exclaimed Balderston.

"I'll get another stone ready," said Thord grimly.

"Yet the man is big enough to do it himself. He can't be a span shorter than I. Bah! with a woman it's different; but a fellow who would run from a bear--"

"Bear!" I cried. "See him zigzag. He wouldn't do that for a bear."

"Must be savages, then," said Thord.

"No; see! There's another like him, on the crest--two!--and they're shooting with bows. He's had a scrap with his comrades."

Balderston was right, at least in part. I even fancied I could see the arrows flash around the fugitive as he leaped sideways in his flight. Suddenly three more men came leaping up on the ridge crest. One of them paused to shoot, but the other two rushed on in chase. Then, all in a body, came a dozen more pursuers, headed by a gigantic woman in huntress dress. At a shout from her, the whole party charged on down the slope.

"Thorlings!" cried Thyra. She stood with flashing eyes, and her nostrils quivered with excitement as she snatched eagerly at her empty belt. Lance and axe lay by the dead bear. As she remembered, she threw up her hand in despair--"Unarmed! unarmed!--and the odds so great!"

"Courage! Here he comes, safe!" I shouted.

"Ay; and the arrows with him," added Thord. "Good Lord! how they shoot! We'll soon be in range."

"Boots and saddles!" shouted Balderston. Black made a dash to bring in his cook outfit; the rest of us seized our rifles.

"We must stop that rush," said Thord coolly.

Balderston's answer was a shot that dropped the foremost pursuer. Thord and I knocked over our men a moment later, and a second ball from the army rifle winged a fourth. That was enough for the Thorlings. Down they went behind a pile of rocks, just out of arrow range, while the hunted man staggered up to the car, all but spent, a great arrow fast in his shoulder and the blood spurting from a sword-cut on his broad chest.

He was of huge build, half a head shorter than Thord, but still almost a giant. As he halted a dozen paces off, and leaned gasping on his lance shaft, he appeared, for all his sorry plight, a magnificent type of manhood. Hard pressed as he was, badly wounded, and as yet ignorant of our intentions, he stood like a lion at bay, not a trace of fear in his bold, questioning gaze.

Thyra was the first to speak.

"Friends!" she cried warningly, as her brother caught sight of the sergeant's scarred black face, and gripped his lance.

"Friends?" he repeated hoarsely.

"Ay!" replied Thord, striding forward with outstretched hand. "Come aboard Skidbladnir."

"Come yourself, Thord," cried Balderston. "The gang up there are stretching their bows. See the arrow beside you."

"Yes; hustle aboard, and out with ballast. We don't want the balloon full of holes again. Keep the enemy close, Frank."

"Just what I had in mind," replied Balderston, and he drove a bullet through the forehead of an incautious Thorling. But the other bowmen lay back out of sight and sent volleys of arrows curving high through the air.

"Dey's comin' close, sah!" warned Black, as a long shaft, thick as his finger, glanced down the out-leaning side of the balloon, and buried its head viciously in the car rim.

"Out with the stones!" I yelled, tugging at a huge block. "Look sharp, Thord."

"Coming, doctor."

The two big men released their handgrip, and Thord almost carried the stranger to the platform. In the excitement of the moment we did not think to put the girl down within the car, where she would have been out of the way as well as more comfortable. As it was, between our numbers and the ballast stones, the little space on the platform was all but jammed. But Thord and I quickly tumbled three stones overboard, and a moment later Black, up above the bearing-ring, cut loose half a thousand pounds of stores.

"Look out! They're going to rush us. The big woman is up and calling them to follow," warned Balderston.

"Rush ahead," growled Thord, as he heaved up the fourth stone. The car was already shifting in its bed. I slashed through the taut anchor rope at the instant that the last block went overboard. Up we soared, a grand and marvellous sight to the astonished Thorlings, and an equal wonder to our rescued guests.

The weight of the guide-rope checked our ascent at no great height, but the raise was sufficient to expose the refuge of the Thorlings. Seeing this, they stood up boldly beside their Amazon leader, and held their bows in readiness as we drifted towards the ridge crest. The breeze bore us somewhat to the left of them, yet not out of arrow-shot of the level on which they stood. Balderston and Thord at once prepared to open fire; but Black, at a sign from me, saved our powder by cutting loose more ballast.

As the sergeant swung down into our midst, we caught sight of a new spectator on the ridge,--a huge Thorling, tall as Rolf Kaki and fully as broad as Thord himself. Through the glasses, I could plainly see the man's evil face, contorted with the ferocity of a wild beast. One of his eyes seemed half-closed by a scar. The other, which was very prominent, rolled uneasily about with a terrible leer. His undershot jaw and brutal expression reminded me of the savage on the peak, but his clothing was of silky furs and a broad band of gold bound his shaggy red hair.

We had no need to ask the name of this ogre. The moment Rolf caught sight of him, he uttered a furious cry--"King Hoding!--Hoding Grimeye! I left him for dead!--Curse the sword which failed me!"

"I'll end the fellow," said Thord, his hard eyes keen for murder. But I struck up his rifle.

"Stop!" I cried. "It will be time to shed more blood when we know the quarrel. There is no need now. We're safe."

"No, by heaven! The others are running for the guide-rope."

"They can't catch it."

"Ef dey do--" muttered Black, patting his rifle.

"If they do, they'll find it hot," added his lieutenant. "Och, me Thorling frins, jes' thread on th' tail o' me coat, now."

We laughed at the invitation, all except Thord. He took deliberate aim at the Thorling who was running with the big woman several yards in advance of the others. With a splendid burst of speed, the unlucky man reached the end of the line and sprang to grasp it as it drew up a ledge. Out roared Thord's express. The Thorling spun around and fell flat.

"Ake-Thor!" shouted Rolf Kaki in wild joy. "That was Eyvind Deerfoot. He it was slew Haldor."

"But the others?" cried Thyra anxiously.

"Arrow-pierced, all three. We were hot on the trail, when the forestmen surprised us. There were five at first, Hoding in the lead; and when the three fell to their arrows, they attacked. Haldor pierced two of them with his javelins, and then fought the second pair, while I met Hoding. It was a hard fight. Hoding cut me, as you see, but I felled him, and Haldor slew the others. Then half a score more came running, led by the woman, who is Bera herself,--Bera of the Orm, the king's half sister. So we fled. But Haldor fell to Eyvind's spear, and Hoding, it seems, was only stunned."

Thyra's eyes overflowed at the recital, but there was no vengefulness with her sorrow. She laid her hand on her brother's arm and said: "Remember, Rolf, the Holy Rune--hold no blood thoughts. The Thorlings have paid doubly, and more. Rather let us thank those who have saved us. But for them, grey biorn would have devoured me,"--and the girl gave a vivid account of her rescue.

Rolf looked at Thord as at a demi-god, and then he turned to me. But I cut short his thanks.

"It is my craft to heal. I will now bind your wounds also," said I, and I opened the surgical case. At once the Polar Northman turned about, and stood without a flinch or groan while I drew the arrow from his shoulder. The tip of the six-inch head had pierced through until it showed in front, but there was no barb, and neither the lung nor any artery had been injured.

I had the arrow wound dressed in short order, but the ugly sword gash was a different proposition. To close it required thirty or forty stitches, yet the man bore the painful operation with wonderful fortitude, almost with indifference. While I still sewed away at the quivering flesh, Balderston picked up the heavy Thorling arrow and wiped the blood from its head.

"Hello!" he exclaimed. "This isn't steel. It's platinum, or I'm a fool!--and the lance head, too."

Thord and Black, who were still watching the Thorlings, now gathered on the crest near their king, at once wheeled about to examine the weapons; but I was so absorbed in my work that at the time the discovery made no impression on my mind.

After I had finished with the needle, it did not take me long to apply my dressings. Not until then did I become conscious of a pair of deep blue eyes that followed my every movement with flattering constancy. Their look put me in a glow, as I realised the advantage I had gained over Balderston by winning the girl's gratitude. To tell the truth, I was already head over heels in love with our fair Polar Valkyrie, and it seemed impossible to me that Balderston should be indifferent. Therefore I was filled with jealousy of the best of friends, and thought enviously of his handsome features. I forgot my dark eyes and black Van Dyke, which, among a blond people, gave a novel attraction to my homely phiz.

"All right, friend Rolf," said I, as I pinned the last bandage. Then, anxious to take all possible advantage of my opportunity, I turned at once to his sister. But before I could speak, our attention was drawn by a shout from Black--"Golly!--red snow!"

I stared down over the bearing-ring, side by side with Thyra. Black's surprise was easily explained. The balloon had crossed a hollow beyond the crest where the Thorlings yet stood gazing after the cloud ship, and now, skimming close above a second ridge, she floated out over a vast glacier field, the nearer side of which was belted with a broad streak of crimson.

"The blood snow," explained Thyra.

"Yes; Protococcus nivalis!"

I replied absently, my gaze following the line of the glacier. It descended into a narrowing valley that seemed to extend downwards to an astonishing depth. For the first time an inkling of the truth entered my mind. I raised my eyes quickly. Thyra stood puzzling over my scientific remark, but the big Northman caught the question in my gaze.

"The Ice-Street," he said, nodding downwards. "It leads up from the Thorling Mark."

"Thorling Mark--a forest?"

"Ay; that of the Ormvol--on the mid-land."

"Betwixt Updal and Niflheim," added Thyra; and I found myself more perplexed than before.

"Niflheim?" I exclaimed, in a voice that attracted the attention of Thord and Balderston.

"Niflheim--Dwergerheim," repeated the girl, puzzled in turn by my surprise. "Surely you know of Hel's under-world--of Hela Pool, where Nidhug lies."

"Oh, she's talking mythology," explained Balderston, laughing.

"Not so," protested Thord. "I really believe--"

"A heavy lurch of the platform flung us in a heap against the bearing-ring--almost overboard. All uttered a cry of alarm, for close in the balloon's wake a great cliff of black rock seemed to shoot up into the air. So swiftly were we falling, I thought the balloon had burst. Yet that did not explain the violent lurch. Then, in a flash, I understood. The trailing portion of the guide-rope had dropped into some deep chasm, and its weight was dragging us clown. A glance at the basalt cliff showed that the speed of our descent was already lessening. But my sigh of relief was answered by a groan from Black. He was glaring down over the side, his face blanched to ashen grey and his eyes almost starting from their sockets.

"Good God, man! what is it?" cried Balderston.

"Lawd--O Lawd!" gasped the negro, his teeth chattering. "De bottomless pit!--O Lawd!"

Seized by a contagion of terror, we peered fearfully down over the side of the car. No wonder the negro was terror-stricken. The balloon hung suspended over the gloomy depths of a vast gulf--a chasm yawning in the earth's crust like the empty bed of an ocean. Overcome with vertigo, we clutched the suspension-ropes, and stared with dizzy eyes at the black wall of the pit, running down, down, down in grand sheer precipices, thousands upon thousands of feet, until lost to view in the gloom of the great deep.

Our blood ran cold in our veins, and every nerve in our bodies tingled with fear of the awful abyss. It was as if the solid earth had collapsed beneath us. For a time we could neither move nor speak, so great was the shock of the discovery.

At last, however, Thord and Balderston and I realised that the balloon was no longer sinking, and the knowledge somewhat restored our presence of mind. Our rigid muscles relaxed, and we gazed about, half fearfully, to measure the extent of the gulf. Eastward the black precipices of the mighty escarpment jutted out in a Titan buttress that hid from our view all the land beyond; while to the north the whole abyss was veiled by wisps of vapour, floating up out of the black depths to the cloud sea. In that direction we could see neither earth nor sky. To the west, however, across a great southward bend of the gulf, we caught vague glimpses of a faraway land, sloping up from the gloom of the lower pit to a dim white sierra of icy mountains.

Balderston was the first among us to speak, and his voice sounded harsh and strained.

"Symmes' Hole!" he muttered.

I shook my head, and, with much effort, managed to reply: "No; I see bottom--miles down--where the sun strikes through the vapours."

"Niflheim!" cried Thord meaningly.

"Ay!" gasped Rolf Kaki, panting as when chased by the Thorlings--"ay, Niflheim--yonder in the lower depths. We float above the Ormvol."

"Lower depths--lower depths!" I repeated, and my jaw fell.

"Where lies Updal?" demanded Thord.

The Northman pointed to the dim outlines of the icy sierra.

"Yonder, beneath the Utgard Jokuls," he answered. "If we float on as now, we shall soar across."

"Good!" cried Balderston, and we breathed easier. The dread of the abyss that had so dazed and appalled us, fast gave place to other emotions. An oath from Thord broke the last bond of the spell. Angry at his own panic, the giant turned upon Black, who still crouched in his place, ashen-faced and rigid, exactly as at first.

"Here, you blasted nigger! Stand up, or I'll kick you over!"

To the rest of us the brutal words acted as a powerful tonic, stimulating all our self-control. But the sergeant only licked his blue lips and moaned hoarsely: "De bottomless pit!--de bottomless pit!"

The man was half crazed with terror. But for his lieutenant, another hour would have seen him raving. With ready wit, Balderston adopted what was perhaps the only way to reach the man's tottering reason.

"Attention!" he commanded, in curt martial tones. "'Bout face!--salute!"

Like an automaton, the sergeant straightened up, wheeled about, and jerked up his hand. Up went Balderston's hand with the same mechanical motion.

"Special order No. 10," he snapped out, "Sergeant Black detailed to cook dinner for the mess."

Again the sergeant gave his jerky salute, and again the lieutenant responded in kind. Suddenly Black drew a deep gasping breath. His scarred face lost its ashen hue, and the hideous glare of his eyes softened to a more human look. His reason was saved. But still he stood at attention, dazed and hesitating.

"Damn you! Step out, sir! What you standing there for?"

"Yas, sah! Goin', sah!" stuttered Black. Then abruptly he flung up his arms and burst into tears.