a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

Title: New Light on the Discovery Of Australia

Author: Henry N Stevens (Editor)

* A Project Gutenberg Australia eBook *

eBook No.: 0900011h.html

Language: English

Date first posted: January 2009

Date most recently updated: January 2009

Production notes: In this ebook, placemarkers for page numbers have been

inserted between {}. After page 85, only odd page numbers are shown since

the even pages show the Spanish text, which has not been reproduced in

this ebook. The placemarkers may not exactly match the top of the relevant

page in the book. They have been inserted at convenient points where a

new paragraph appeared in the text. They should, however, still enable the

user to find reference points referred to in the text.

Project Gutenberg Australia eBooks are created from printed editions

which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice

is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular

paper edition.

Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the

copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this

file.

This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg Australia License which may be viewed online at

http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

This volume is also issued by

The Hakluyt Society

as Series II, Vol. LXIV

forming a supplement to

The Voyages of Quiros

edited by Sir Clements Markham

Series II, Vols. XIV and XV

TO THE MEMORY OF

SIR CLEMENTS MARKHAM, K.C.B.

TO WHOSE WORK ON THE VOYAGES OF QUIROS

PUBLISHED BY THE HAKLUYT SOCIETY IN 1904

THIS VOLUME

COMPILED FROM HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS SINCE COME TO LIGHT

NECESSARILY FORMS A SEQUEL

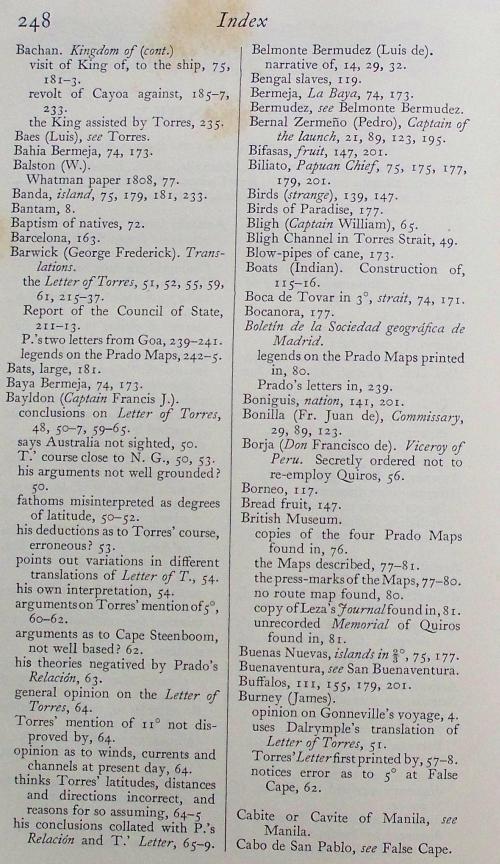

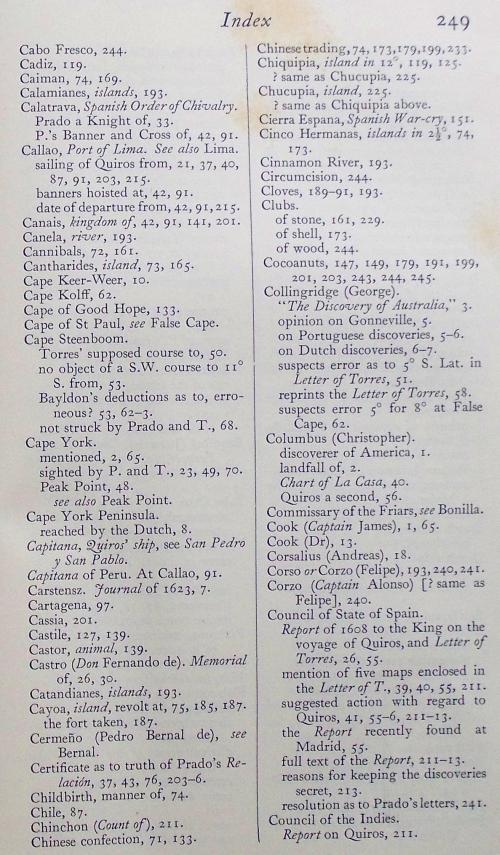

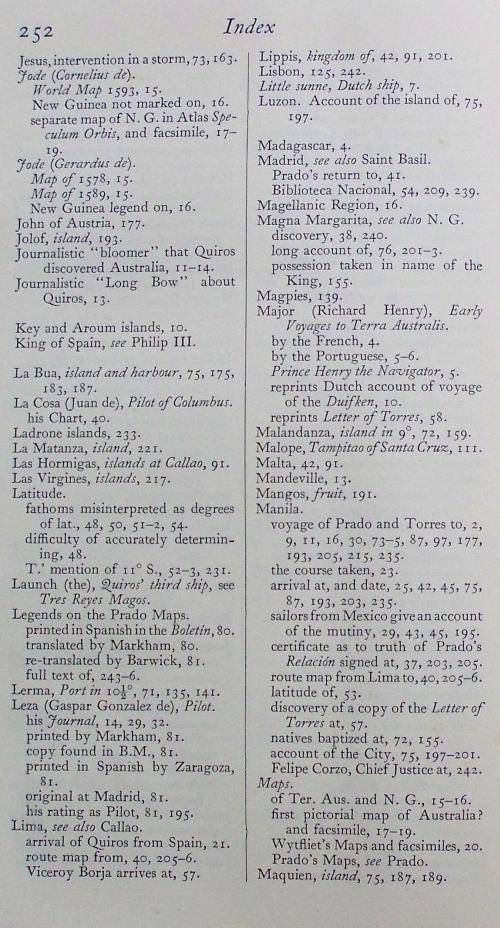

CONTENTS: 1. Editor's Preface 2. New Light on the Discovery of Australia 3. Note on Prado's Relación 4. Relación de don Diego de Prado (Spanish and English) 5. Appendices: I. Report of Council of State with Letter of Luis Vaez de Torres (Spanish and English) II. Mr Barwick's translations of Prado's two Letters sent from Goa in 1613 III. Mr Barwick's translations of the Legends on the Four Prado Maps 6. Index

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS: 1. Map of New Guinea from Cornelius de Jode's Speculum Orbis Terrae of 1593 2. Map of World from Wytfliet's Descriptionis Ptolemaicae Augmentum 1597 3. Map of "Chica sive Patagonica et Australis Terra" from Wytfliet 4. Reduced facsimile of the first page of Prado's Relación 5. Reduced facsimile of the last page of Prado's Relación 6. Facsimiles of the Four Prado Maps 7. Sketch Map of the Voyage of Prado and Torres deduced from dates, latitudes, etc.

{Page ix}

The recovery of the long-lost manuscript Relación of Captain Don Diego de Prado y Tovar, who accompanied Pedro Fernandez de Quiros on his famous voyage of exploration in the South Seas in 1605-6, is undoubtedly the most important "find" of virgin historical material made in modern times. It furnishes us for the first time with a detailed account of the discovery of Torres Strait and Northmost Australia, made during the continuation of the voyage to Manila by Prado and Torres after the parting of the ships at the Island of Espiritu Santo, whence Quiros returned to America.

In 1904 the Hakluyt Society published The Voyages of Pedro Fernandez de Quiros, edited by the late Sir Clements Markham, which included everything known up to that time about the expedition of Quiros as far as the Island of Espiritu Santo and the continuation, presumably by Torres, of the voyage to Manila. Very little was known of the details of the completion of that voyage beyond the bare fact that Torres forced his way through the Strait which now bears his name, and ultimately reached Manila. The knowledge (as revealed by the new Relación) that after the departure of Quiros the office of Chief of the Expedition had devolved upon Prado under sealed orders opened at the Island of Espiritu Santo, and that Torres was thereafter merely acting as his navigating Captain, will come as a complete surprise to students of historic geography. It has always been supposed, from the scanty evidence hitherto available, that the voyage was completed by Torres alone.

{Page x}

The voyage of Prado and Torres was one of the most eventful made since the days of Columbus, although the great importance of its results has not been fully recognised because so little has hitherto been known about it. Besides giving a lengthy and graphic account of the voyage itself, Prado's Relación largely resolves the mystery which has prevailed for more than three hundred years concerning the character and actions of Quiros, and explains the reasons which caused him so suddenly to abandon his expedition and return to America.

From a hitherto unrecorded Report of the Spanish Council of State made to the King in September 1608 (a copy of which was unexpectedly secured from Madrid whilst the present volume was in the press)we now learn for the first time the reasons why so little information about the voyage of Quiros and its continuation ever reached the world at large. Quiros by this time (1608) had returned to Spain from America, and was dancing attendance at Court, petitioning for further employment in order to continue his discoveries. The Report states that "quite recently" there was laid before the Council a letter from Luis Vaez de Torres (presumably his well-known letter of July 12th, 1607) giving an account of what had been discovered in his voyage and how "likewise were exhibited five maps which he sent of some ports and islands where he landed." From this Report it is evident that the Council was in possession of ample information both as regards the voyage of Quiros himself and its continuation by Torres. The Report gives the Council's cogent reasons why the recent discoveries should be kept secret, and why Quiros should not be commissioned to make further voyages but should be kept employed in Spain as a cosmographer, in order that he might not be in a position to give information of his discoveries to the King's enemies. The discovery of this Report, which adds so greatly to the interest of thepresent volume, was made just in time to permit of the Spanish text being printed in full in the Appendix, together with a translation into English.

{Page xi}

Some few years ago, at the dispersal by auction at Sotheby's of the Spanish Manuscripts collected by the late Sir Thomas Phillipps, my firm (Henry Stevens, Son and Stiles) acquired a large number of miscellaneous papers bound up in several thick volumes. As we were unable to deal immediately with this mass of material the volumes were laid aside until an opportunity should occur to examine the various papers in detail. Some time afterwards my partner, Mr Robert E. Stiles, undertook to make a preliminary inspection of these Manuscripts. Then it was that on going through one of the volumes he came across this Relación of Captain Don Diego de Prado, buried amongst a quantity of comparatively unimportant documents relating to Portugal and the Indies. He immediately recognised the fact that anything relating to the continuation of the voyage of Quiros, after he himself had abandoned it and returned to America, must be entirely new and unknown material, and consequently of the utmost value to the history of maritime discovery.

A study of the aforementioned work by Sir Clements Markham, The Voyages of Quiros, revealed the importance of the newly-recovered Manuscript. Furthermore an examination of the facsimiles of the four Prado Maps appended to Markham's book, and a comparison of the handwriting on them with that of the Relación, proved beyond doubt that the latter was entirely in the autograph of Prado. The identification of the Manuscript being thus definitely established, and Mr Stiles being unable on account of his health to continue the investigation, the whole matter was turned over to me, but as my knowledge of Spanish was quite inadequate to complete the work, I at once consulted an eminent Spanish scholar in the person of my friend Mr G. F. Barwick, Keeper of Printed Books, British Museum, 1914-1919. Mr Barwick, immediately realising the vast importance of the Relación, very kindly offered to translate it into English.

{Page xii}

In the meantime a preliminary report embodying an abstract of the Relación had been prepared, and after some negotiation the Manuscript was acquired by that indefatigable and zealous collector, Sir Leicester Harms-worth, who, generously recognising that considerable kudos attached to the discovery of such a valuable historical document, kindly consented to its publication under my editorship.

Through the kind instrumentality of Dr Henry Thomas of the British Museum, a photostat has just been obtained of a copy of the original Letter of Torres in Spanish, preserved in the Biblioteca Nacional at Madrid. It is thus possible to print for the first time the Spanish text of this important letter. Mr Barwick has made an entirely fresh translation which is also given, and which will be found to vary considerably from the hitherto accepted version. It is to be hoped that the new translation will elucidate many of the doubtful points which, ever since Burney's time (1806), have puzzled historians endeavouring to interpret Torres' meaning.

To Mr Barwick is also due the re-discovery of copies of the four Prado Maps in the Manuscript Department of the British Museum, where they have lain practically unidentified for some eighty years, having apparently escaped recognition by all writers on historical geography during that lengthy period. They are fully described in the Bibliographical Notes at the end of the introductory text (Vide p. 76).

HENRY N. STEVENS

39 Great Russell Street London, W.C. 1

March 1930

{Page 1}

Ask whom you will Who discovered America?--even the veriest tyro would unhesitatingly reply Christopher Columbus, but to a similar question Who discovered Australia? the answers would be surprisingly diverse and uncertain. Many would confess at once I don't know, but a few would probably add interrogatively Wasn't it the French? or Wasn't it the Portuguese? Others again would exhibit equal uncertainty by replying with a counter-question, Wasn't it the Dutch in the Duifken? Some might even suggest Captain Cook, but he, of course, must be ruled out absolutely, as obviously more than a hundred and fifty years too late. Undoubtedly the majority of those having any pretensions to a knowledge of historic geography would answer The Spaniards under Quiros, though a few, still better informed, might attribute the discovery to Torres. It is, however, safe to say that no one would have mentioned the name of that comparatively unknown and hitherto much-maligned man Captain Don Diego de Prado y Tovar (the author of the recently recovered Relación), to whom the honour of the first definite discovery of Australia undoubtedly belongs, for, as will be seen, he succeeded to the supreme command of the Quiros expedition under sealed orders opened at the Island of Espiritu Santo, after Quiros himself had abandoned the voyage and returned to America. This important fact, as revealed by the new Relación, is entirely new to history, for it has always hitherto been supposed that the voyage was continued under the command of Torres alone. We now learn that Prado, in company with Torres as his second in command, completed the voyage to Manila, but instead of passing to the north of New Guinea on the direct course, as provided for in the general orders, was compelled by stress of weather to sail along the south coast. To that fortuitous circumstance we owe not only the discovery of the tortuous passage between New Guinea and Australia (now known as Torres Strait) but incidentally the first definite discovery of Australia itself.

{Page 2}

In case it should be thought that too much is being claimed for this new Relación in saying that it contains the first definite account of the discovery of Australia, it will be sufficient to recall the fact that whether Prado and Torres did, or did not, actually sight the mainland (on which point historians differ), all the islands in the passage between New Guinea and Cape York form part and parcel of Australia, for they are under the jurisdiction of the Colony of Queensland. The Boundary of Queensland extends on the north almost to the coast of New Guinea, including the Talbot Islands, and on the \neast as far as the Great Barrier Reef, hence any islands discovered within those lines, in latitudes higher than 9° 20'S., may unquestionably be claimed as Australia. The case is somewhat analogous to that of Columbus, who discovered America in 1492. His landfall was certainly not on the mainland, but on an island in the West Indies a long distance away from it, which island has never been under the jurisdiction of any country on the mainland, and yet no one would dispute the claim that Columbus discovered America. In the case of Prado and Torres the islands they discovered, actually landed on and named, do belong to the adjacent mainland of Australia, and many of them are only a few miles away.

{Page 3}

As the main object of the present volume is to reveal the new light shed by Prado's Relación on the voyage of Quiros, and more especially on the discovery of Torres Strait and Australia, it does not come within our province to discuss at any length the obscure problem of the gradual evolution of the great continent from the "sea of darkness". Anyone wishing to follow the general discovery of Australia in all its ramifications cannot do better than consult Collingridge(*) in the first instance, for he discusses at great length, in chronological sequence, every known or reputed voyage to Terra Australis or Australia from the earliest times. There are of course numerous other later historians whose works may also be consulted.

[* Collingridge, George. The Discovery of Australia. 4to. Sydney, 1895.]

Australia is so large that the discovery at one period of any part of it has little bearing on the discovery at other times of other portions which might well be hundreds, if not thousands, of miles apart. There is of course some sentimental interest in the vexed problem as to which nation first discovered any part of the great continent, but all accounts of the earliest discoveries are based more or less on supposition derived from insufficient or doubtful evidence. Moreover the discoveries of the French and Portuguese, even if they could be definitely authenticated, do not conflict in the slightest degree with those of the Dutch and Spaniards, for those of the former are supposed to have been made somewhere on the west side of Australia, whereas those of the latter are definitely located on the north coast. Consequently it has not been thought necessary to do more here than to touch very briefly on the claims made on behalf of the French and Portuguese, but those of the Dutch, having more direct relation to our subject, are discussed rather more fully. It will, however, be realised that in setting forth in the present volume the immense importance of the discoveries made by the Spaniards under Prado and Torres, one cannot altogether ignore the rumoured previous discoveries of other nations, although they were comparatively unimportant.

{Page 4}

A good deal of the uncertainty existing as to the prime discovery of any part of the great Australian continent appears to have arisen through the confounding of the name Australia with the term Terra Australis as used by the map makers of the sixteenth century to denote the lands depicted on their charts in the austral regions. These imaginary lands were often shown as completely encircling the antarctic region, and extending north in some places to within fifteen degrees of the Equator. Hence the Terra Australis supposed to have been discovered need not necessarily have been any part of the Australia of to-day.

THE FRENCH. Major in Early Voyages to Terra Australis, p. xxiii, 1859(*), states "The earliest discovery of Australia to which claim has been laid by any nation is that of a Frenchman, a native of Honfleur named Binot Paulmier de Gonneville, who sailed from that port in June 1503 on a voyage to the South Seas". Major devotes three pages to a recital of all that was then known of Gonneville, but does not seem to give much credence to the idea that his discoveries included Australia. In fact he appears to agree with Burney(**) who says "let the whole account be reconsidered without prepossession, and the idea that will immediately and most naturally occur, is, that the Southern India discovered by Gonneville was Madagascar".

[* Hakluyt Society, vol. xxv, 1859.]

[** Burney, James. A chronological History of the Discoveries in the South Sea or Pacific Ocean. 5 vols. 4to. London, 1803. Vide 1, 379.]

Little, if any, fresh evidence has come to light since Major's day, though some modern historians seem to think that the maps of Pierre Descelier afford indications that the French had some knowledge of land in the position of Australia. Collingridge(*) on p. 93, in discussing the claim made for Gonneville that he landed on the west coast of Australia in 1503, states that it cannot be considered as having been established. In his Appendix, p. 210, he deals with the matter in greater detail, and gives cogent reasons for his conclusions that the French claim for Gonneville is untenable.

[* Op. cit. ante, p. 3.]

{Page 5}

THE PORTUGUESE. As to their supposed discovery of Australia, Major in Early Voyages(*), p. xxi, 1859, thinks that a more reasonable claim than that of the French may be advanced for the Portuguese, based on the evidence of various manuscript maps still extant. He devotes over forty pages to a careful analysis of the existing evidence, which is, however, merely cartographical. He sums up his arguments concisely on p. lxiv as follows: "Our surmises, therefore, lead us to regard it as highly probable that Australia was discovered by the Portuguese between the years 1511 and 1529, and, almost to a demonstrable certainty, that it was discovered before the year 1542". In 1861 Major strengthened his arguments, for in that year he published a Supplement to his Early Voyages in which he announced the recent discovery in the British Museum of a manuscript Mappemonde on which is marked a country "which I shall presently show beyond all question to be Australia". Nevertheless, Major at a later date, having come across fresh data in the meantime, seems to have changed his mind, for he reverts to the subject in his famous book Prince Henry the Navigator published in 1877, and therein sets forth his altered views at great length.

[* Op. cit. ante, p. 4.]

Collingridge(*) on p. 93 states that in his opinion the claim to the discovery of Australia on the western coast in 1601 by the Portuguese, under Manoel Godinho de Eredia, cannot be considered as having been substantiated. In his Appendix, p. 315, he discusses the question of the supposed earlier discovery and quotes Major's altered views at some length. As far as the writer is aware, no fresh evidence bearing on the Portuguese discoveries has come to light since the time of Collingridge (1895).

[* Op. cit. ante, p. 3.]

{Page 6}

THE DUTCH. The claims for the French and Portuguese, as already suggested, do not in any case conflict with those made for the Dutch and the Spaniards, for the voyages were at different periods and the supposed landfalls of the two former were at vast distances from those of the two latter. The voyages of the Dutch and the Spaniards are, however, to a certain extent intermingled, for they were contemporary (1606) and the places visited were practically contiguous. The case for the Dutch is based on the supposed voyage of the ship Duifken(*) in 1605-6, and the subject has been touched on more or less extensively over a lengthy period by numerous writers on early geographical discovery. An analysis of the opinions of four of them (perhaps the best known of modern authorities), taken in chronological sequence, will be sufficient to show that the question is still somewhat vexed, doubtless owing to the fact that no actual contemporary documentary evidence is known to exist. The story has consequently been deduced from sundry references to the voyage made in documents of a later period, perhaps the most important of which bears date as late as 1644. Nevertheless there are certainly good grounds for believing that such a voyage was actually made, though the precise landfall in Australia and even the definite date are both somewhat problematical.

[* The spelling Duifken is copied from the Dutch as quoted by Heeres. Other authorities give Duyfken, Duifhen, Duyfhen, etc.]

1. Collingridge(*) (1895). Collingridge at the opening of his chapter xl confesses that on entering upon the Dutch period of discovery in Australia "we feel very diffident and ill at ease". He devotes nearly eight pages to a lengthy analysis of the authenticity of the record of the Duifken, and points out numerous discrepancies in the evidence on which the claim to the discovery by that vessel is based. In particular he shows that the Journal of Captain John Saris (as printed in Purchas His Pilgrimes, vol. 1, Part 2, p. 385, 1625) does not actually mention the Duifken by name but refers to another vessel called the Little sunne. In conclusion he states that "the whole matter seems to resume (sic) itself into the examination of the provenance or authenticity of the said documents" (i.e. the various documents he has mentioned).

[* Op. cit. ante, p. 3.]

{Page 7}

2. Heeres(*) (1899). Dr Heeres confesses that the Journal of the voyage of the Duifken has not come clown to us, "so that we are fain to infer its results from other data, and fortunately such are not wanting". He then mentions some authentic documents of 1618, 1623 and 1644 which relate more or less to the voyage of the Duifken. He refers to the Journal of Carstensz of 1623 as containing important particulars of the voyages of his predecessors in 1605-6, and mentions the fact that Carstensz had on board the Chart of the Duifken, but was himself unable to find any open passage such as appeared to be indicated on the said Chart. Heeres also describes the recital of previous Dutch voyages which was prefixed to the Instructions issued to Captain Abel Jansz Tasman in 1644, the first item of which actually describes the voyage of the Duifken and its results. This document is printed in full by Major in Early Voyages, pp. 43-4.

[* Heeres, J. E. The Part borne by the Dutch in the Discovery of Australia, 1606-1765. 4to. Leiden and London, 1889. In Dutch and English.]

3. Heawood (1912). Mr Edward Heawood, Librarian of the Royal Geographical Society, in his concise and most useful reference manual, History of Geographical Discovery in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries(*), devotes several pages to the discovery of New Guinea and Australia 1605 to 1642. He first discusses the voyage of the Dutch in the Duifken and raises no doubt as to the credibility or reliability of the collateral evidence relating thereto. Consequently his conclusion is "that the priority of discovery undoubtedly belongs to the Dutch as compared with the Spaniards under Torres".

[* Cambridge, at the University Press, 1912. Cr. 8vo. Vide chap. iii, pp. 70-1.]

{Page 8}

4. Jack(*) (1921). Mr R. Logan Jack in Northmost Australia devotes several pages to the voyage of the Duifken. He merely repeats and comments on the evidence already adduced by previous writers (principally Heeres), but as he offers no new facts, it is not necessary to refer to him further, especially as he expresses no definite opinion as to the credibility of the evidence he re-exhibits or quotes.

[* Jack, Robert Logan. Northmost Australia. Three centuries of exploration, discovery and adventure in and around the Cape York Peninsula, Queensland. 2 vols. Royal 8vo. London, 1921. Vide chap. iii, pp. 22-7.]

It is submitted that from the foregoing summary a reasonable deduction can now be drawn that any claim for a French or Portuguese prime discovery may be dismissed as too indefinite to be entertained. On the other hand the claim for the Dutch in the Duifken, although not based on contemporary documents, is so well supported by collateral evidence that it cannot well be doubted or disproved. According to the evidence, the Duifken in 1605-6 sailed eastward from Bantam along the south coast of New Guinea as far as the beginning of Torres Strait, and then turning southward reached land on the west coast of the Cape York Peninsula at about 13¾° S. Lat. Authorities seem to be agreed that Willem Janszoon, the commander of the Duifken, failed to recognise that there was a passage through to the east at the south side of New Guinea, for it is generally supposed that he considered all the land he had seen formed part of that great country.

{Page 9}

The evidence hitherto existing on behalf of the voyage of the Spaniards in 1606 (i.e. the letters of Torres and Prado and the Prado maps) is now enormously strengthened by the recovery of the lengthy Relación of Prado. All this evidence is not only firsthand but contemporary, and is thus far more definite and convincing than the indirect accounts of the voyage of the Duifken. The Dutch and Spanish voyages do not in any way conflict, except on the one point as to which nation first sighted (quite unconsciously in either case) the great continent of Australia. The Dutch approached Australia from the west and returned without discovering or passing through the strait. The Spaniards on the other hand came from the east, and by stress of weather were forced into the eastern opening of the strait, through which they picked their tortuous way amongst the numerous islands and shoals, and ultimately completed the voyage to Manila along the south side of New Guinea.

Taking all the circumstances into consideration it would appear that by reason of the few months' priority in date, the honour of the first discovery of any part of Australia cannot be denied to the Dutch. Let it be granted therefore that the Dutch, coming from the west, were the first to discover Australia on the west side of the strait, whilst the Spaniards, approaching from the east, were the first to discover not only the strait itself but that part of Australia adjacent thereto. But when we come to analyse the comparative importance of the two voyages and the two discoveries, the palm must unquestionably be awarded to the Spaniards, as the above brief contrast of the results makes abundantly manifest. The Dutch in their own official recital of the voyage of the Duifken, as prefixed to the Instructions to Tasman in 1644, practically admit the failure of that voyage, for it is stated that nothing could be learned of the land or waters visited, so that "they were obliged to leave the discovery unfinished". The Narrative is so interesting and important that it may be as well to quote here the salient parts of it from Major's Early Voyages, p. 43, where the document is printed in full.

{Page 10}

...the yacht the Duifken...sailed by the islands Key and Aroum, and discovered the south and west coast of New Guinea...from 5° to 13¾° south latitude: and found this extensive country, for the greatest part desert, but in some places inhabited by wild, cruel, black savages, by whom some of the crew were murdered; for which reason they could not learn anything of the land or waters, as had been desired of them, and, by want of provisions and other necessaries, they were obliged to leave the discovery unfinished; the furthest point of the land was called in their Map Cape Keer-Weer(*), situated in 13¾ S.

[* Cape Turn again.]

It is extremely difficult at this late date to trace the origin of the popular myth that Quiros personally was the actual discoverer of of Australia. The late Sir Clements Markham in his admirable work on the Voyages of Quiros edited for, and published by, the Hakluyt Society in 1904(*), summarises all that was known at that time about the voyage in 1605-6 when Quiros set sail from Peru under a mandate from the King of Spain, in search of unknown but rumoured lands in the southern seas. It is probable that the name Austrialia del Espiritu Santo(**) which Quiros had given to a large island discovered early in his voyage, and which he mistook for continental land, may have become confounded as time progressed with the name Australia afterwards popularly conferred on the great continent as we know it to day. Be this as it may, the fable that Quiros was the discoverer of the real Australia gained almost general acceptance, until Markham's book showed conclusively that he had nothing whatever to do with the discovery and never came within a thousand miles of the great continent.

[* The Voyages of Pedro Fernandez de Quiros, 1595 to 1606. Translated and edited by Sir Clements Markham, K.C.B., P.R.G.S., President of the Hakluyt Society. In 2 vols. London. Printed for the Hakluyt Society 1904. (Second Series, vols. xiv and xv.) Herein afterwards cited as Markham, Op. cit., or simply Markham or M.]

[** Cf. Markham, Op. cit. pp. xxv, xxx, 251, 442, 470, 487, 503, 507, etc.]

{Page 11}

Notwithstanding all that Markham wrote in 1904, the fiction still persists, and seems actually to have gained ground during the last twenty years or so. It will hardly be credited that one of London's leading daily journals, usually well informed and reliable, printed, as recently as August 1928, a special article on The Discovery of Australia, in which the long since exploded Quiros myth was resuscitated, and supported by considerable plausible detail. The article announced the recent acquisition by an American dealer of some hitherto unknown documents relating to "Pedro Fernandez de Quiros the discoverer of Australia", and a facsimile of his handwriting was given, lettered "The Signature of Pedro Fernandez de Quiros the discoverer of Australia". The article proceeded to give a brief account of how Quiros in December 1605 set sail with two ships from Callao on a voyage of discovery in the "unknown austral regions of the South Sea". We are then told that "The expedition discovered the islands which fringe the coast of Australia, and the two ships becoming separated in a storm Quiros returned to Mexico while the other ship went to Manila...It will be seen therefore that while Captain Pedro Fernandez de Quiros came within sight of the great Australian Continent and actually discovered the outlying islands he never reached the continent itself". What delightful romance, so plausible and convincing and yet all pure imagination! The only grain of truth in the whole of the above quotation is the distorted fact that the ships did become separated in a storm, and that Quiros did actually return to Mexico, but the storm and the departure for Mexico did not occur anywhere near Australia. Quiros must have possessed the longest sight of any man on record if he really "came within sight of the great Australian Continent", for the nearest point he ever reached was the Island of Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides group, roughly some fourteen hundred miles away! It was at this island that the storm occurred during which Quiros turned back to America.

{Page 12}

The writer pointed out to the editor of the journal in question the inaccuracy of its statements (as did at least one other correspondent), but, as far as he is aware, no correction or retraction was ever vouchsafed. It can only be presumed, therefore, that the editor and his contributor are still of the opinion that Quiros discovered Australia, and are peacefully enjoying that blissful state which Gray seems to suggest 'twould be folly to disturb. For that reason this most amazing journalistic "bloomer" of modern times, which has so amused the geographical world, is placed on record here as an excellent example of the modern pernicious, but very prevalent, practice of writing on historic subjects without first verifying the prime sources of information. By the neglect of this precaution the erroneous deductions of the writers of one generation become the accepted truths of the next. Fictions and the facts from which they emanate become so inextricably mingled that often the original modicum of truth is distorted, obscured and finally lost. Only by an independent analysis of basic facts and the sweeping away of the superincumbent fictions of successive writers quoting and enlarging one from another, can we hope to arrive at a solution of some of the many mysteries which becloud early geographical history. The present investigation, as will be seen, has brought to light several curious and flagrant examples of the way in which historic facts have gradually become distorted over a long period of years, owing to mistranslations or misinterpretations of the meaning of the original writer.

{Page 13}

It was not until seven months after the article on The Discovery of Australia had appeared in the journal in question, that the editor on Easter Saturday, March 30, 1929 (perhaps the slackest day in the whole journalistic year), published the writer's letter in much abbreviated form, from which had been eliminated all direct correction or contradiction of the error of August 1928, which it was no doubt thought had faded into oblivion in the meantime. Only a preliminary announcement was made of the discovery of the new manuscript and the intended publication of it in the present volume. By a strange coincidence the same journal published on May 3, 1929, a leading article on "The Long Bow", and cited several instances of bogus claims to geographical discovery, e.g. Mandeville, De Rougemont, Dr Cook, etc., etc., but curiously enough no reference was made to its own "long bow" in championing Quiros as the Discoverer of Australia, a claim that poor Quiros never made for himself.

Antiquarian booksellers seem also to be marching with the times, for they are frequently responsible for the further propagation of the Quiros fable. When offering for sale in their Catalogues material relating to Quiros they generally make erroneous reference to his discovery of Australia. Book auctioneers also seem to be imbued with this spirit of the times, for as recently as June 24, 1929, Sotheby's Catalogue, under Lot 30, described Hessel Gerritsz's Collection of the voyages of Hudson, Quiros and others, published at Amsterdam in 1612, as "the first printed account of Hudson's discoveries in North America and the second published account of the discovery of the Northern Coast of Australia by Quiros".

These instances are mentioned as tending to show how deeply rooted and widely disseminated is the Quiros myth, and how difficult it appears to be to eradicate it. It is to be hoped that the new Prado Relación will now give the coup-de-grâce to this long-persistent Quiros hydra, though it must not be forgotten that Theodore Hook once wrote that "a reply to a newspaper resembles very much the attempt of Hercules to crop the Hydra without the slightest chance of his ultimate success".

{Page 14}

It is greatly to be regretted that the discovery of the Prado manuscript was not made in Sir Clements Markham's time, so that he could have included an account of it in his book on the Voyages of Quiros. One can imagine how overjoyed that eminent geographer would have been to have had the opportunity of collating the new Relación with the existing Narratives of Belmonte Bermudez, Gaspar de Leza and Torquemada(*). At the same time we cannot but realise how different would have been his estimate of the respective characters of Quiros and Prado, after he had weighed impartially the new facts in the entirely independent Relación of the latter, against the three above-mentioned narrations all apparently more or less inspired or influenced by Quiros himself.

[* All printed by Markham]

It is not of course a congenial task to have to traverse the deductions drawn by so eminent an authority as Sir Clements Markham from evidence existing in his time. The Relación of Prado is however so clear and circumstantial, and is moreover so obviously confirmed by the letters of Torres and Prado and the four Prado Maps already known and hereinafter reprinted(*), that it is impossible to doubt that it bears the impress of truth.

[* Vide Appendix]

Prado's description of events up to the separation of the ships at Espiritu Santo agrees in the main with the three existing Narratives, but his account of the continuation of the voyage to Manila covers entirely new ground. He gives a detailed record of events following the departure of %tiros, hitherto only known from the very scanty account given by Torres in his letter to the King dated from Manila, July 12, 1607, and from Prado's four maps, and from his two letters sent home from Goa in 1613(*).

[* Vide Appendix]

{Page 15}

(Continued on page 24.)

Before describing the newly discovered Relación it may be as well to state briefly what was apparently known about "Terra Australis incognita" prior to the Voyage of Quiros in 1605-6, and also to give a short résumé of the principal facts hitherto known respecting that Voyage, as detailed by Sir Clements Markham in his aforementioned book or recorded by other writers. Afterwards it is proposed to collate the existing knowledge of the Voyage with the new information to be derived from Prado's Relación, and then to comment on the differences.

During the latter half of the sixteenth century, rumours which had long prevailed as to the existence of a great Antarctic Continent, became so persistent that the map makers of the period began to insert on their maps large tracts of continental land in the Southern Seas, sometimes unnamed, but generally marked "Terra Incognita", "Terra Australis", or "Terra Australis nondum cognita", etc., etc. Amongst such world-maps may be mentioned those of Orontius Finaeus 1531, Vopelius 1543, Demongenet 1552, Ortelius 1570, Gerardus de Jode 1578, Mercator 1587, Gerardus de Jode 1589, Cornelius de Jode 1593 and Myritius 1596. Reproductions of most of these maps may be seen in Nordenskiöld's Facsimile Atlas published in 1889. There are of course many others, but these will serve as examples.

{Page 16}

The maps of Ortelius, Mercator and Gerardus de Jode (1589) show Nova Guinea as a complete Island with a narrow strait between it and the continental land marked Terra Australis etc. On the first two of these maps the following two legends appear in identical terms: Nova Guinea nuper inventa que an sit insula an pars continentis Australis incertu est--New Guinea lately discovered whereof it is uncertain whether it be an island or part of the Austral Continent--Hanc continentem Australem, nonnulli Magellanicam regionem ab eius inuentore nuncupant--This Austral Continent some call the Magellanic region from its discoverer. The second legend also appears on the map of Gerardus de Jode 1589. On the hemispherical world-map of Cornelius de Jode 1593, Nova Guinea is not marked at all, but on that of Myritius it is laid down and named as actually forming part of the mainland, which is lettered Terra Australis nondum bene cognita.

In such of the above-mentioned maps as show a passage between New Guinea and Terra Australis, the strait is never laid down in its true place between 9° and 11° S. Lat., but always much farther south in varying positions between 18° and 22°. This fact alone tends to demonstrate that any knowledge of the supposed strait had not been derived from actual observation, but was merely hypothetical. Nevertheless some modern writers are inclined to the belief that Torres had a definite knowledge of the strait and was making for it on his voyage to Manila, but it is shown later on(*) that this conclusion cannot be substantiated. It is clear, however, that there must have been rumours of a supposed passage, for the strait is definitely mentioned by Wytfliet in 1597 in the text of his book(**), but even his knowledge appears to have been based on legendary supposition.

[* Infra, pp. 46-7.]

[** Vide infra, p. 20]

{Page 17}

The curious hypothetical representations of various prime discoveries, which occur more or less on all early maps, both manuscript and printed, are amongst the most abstruse problems with which students of historic cartography have to contend, for it is generally not only difficult to trace their origin, but still more difficult to disprove them altogether. When, as frequently occurs, these cartographical vagaries are used and quoted as definite evidence in support of modern theories of early geographical discovery, the results are often extremely ludicrous. An amusing example (somewhat analogous to the present case of the supposed strait to the south of New Guinea) is that of the American journalist who, when reviewing in 1903 the then recent publication of the facsimile of the great Waldseemüller map of 1507, emphasised the fact that on that map the North and South American continents were not joined, and that therefore the Panama Canal was merely the re-opening of the old channel which must have become silted up during the intervening centuries.

Perhaps the most interesting of all the early maps relating to New Guinea and the strait is the large-scale special one of "NOVAE GVINEAE Forma & Situs" which appears as No. 12 in Cornelius de Jode's Atlas of 1593 Speculum Orbis Terrae. This map is so rare that it has been thought desirable to reproduce it here in reduced facsimile(*). The east end of New Guinea is shown with a wide strait between it and a large tract of unnamed continental land, in the position of Australia, extending from the Tropic of Capricorn southward to 56°, where it is cut off unfinished by the bottom border line. The east and west sides are similarly cut off. It will be observed that the strait in its narrowest part is here laid down between 20° and 23°, which fact alone militates against the authenticity of the whole map. Consequently we cannot accept the large tract of land to the south of the strait as representing a continent actually known. This is unfortunate, for the interior of the country is embellished with ranges of mountains, and pictures of a dragon, a lion, a serpent, and a hunter armed with bow and arrows. If this map could have been definitely identified as part of the continent we now know as Australia, we should have here the very first pictorial representation of Australian fauna.

{Page 18}

The sea is similarly decorated with a ship in full sail and several nondescript sea-monsters. In any case this map is an excellent example of the methods employed by the map makers of the period to portray rumoured discoveries from insufficient data. It shows also how it was the custom to fill in vacant spaces with pictorial embellishments at the fancy of the draughtsman. Further proof that this map cannot be considered as authentic is given in the Latin inscription engraved on it in the interior of New Guinea, which (translated) reads:

New Guinea. So called by the sailors, because its shores and character greatly resemble the land of Guinea in Africa. Whether it joins on to the Austral land or is an Island is unknown.

[* Vide p. 19, size of the original 8½ by 13 5/8 inches at the plate mark.]

A long Latin description of the map, type-printed on the verso, states:

This Region up to the present day is almost wholly unknown, for after the first and second voyage, navigation hither has been omitted, so that up to this time it is doubtful whether it be mainland or an island. The sailors called it New Guinea, because the shores, position and character of this region greatly resemble the land of Guinea in Africa. It seems to have been called Peccinacolij by, Andreas Corsalius. On the South of this region is the great tract of the Austral land, which when explored may form the fifth part of the world, so wide and vast is it thought to he. On the east it has the Solomon Islands, on the North is the Archipelago of S. Lazarus, and it begins at two or three degrees below the Equator. On the west, if it be not an island, it is joined to the Austral land.

Unquestionably the most important and relevant maps of this period are the two (here reproduced) which are found in Cornelius Wytfliet's Descriptionis Ptolemaicae Augmentum first published in Latin at Louvain in 1597, for on p. 101 of the descriptive text accompanying them is the following remarkable passage, wherein the strait is definitely mentioned:

{Page 19} [Map of NOVAE GVINAE--see below]

{Page 20}

Australis igitur terra omnium aliarum terrarum australissima, directe subiecta antarctico circulo, Tropicum Capricorni vltra ad Occidentem excurrens, in ipfo penè aequatore finitur, tenuique difcreta freto Nouam Guineam Orienti obijcit, paucis tãtum hactenus littoribus cognitam, quòd post vnam atque alteram nauigationem, curfus ille intermissus fit, & nisi coactis impulsifquc nautis ventorum turbine, rarius eò adnauigetur. Australis terra initium sumit duobus aut tribes gradibus fub aequatore, tantaeque a quibufdam magnitudinis esse perhibetur, vt fi quando integrè deteda erit, quintam illam mundi partem fore arbitrentur. Guinea a dextris adhrent Salomoniae insulae multae & quae nauigatione Aluari Mendanij nuper inclaruêre, &c.

The terra Australis is therefore the southernmost of all other lands, directly beneath the antarctic circle; extending beyond the tropic of Capricorn to the West, it ends almost at the equator itself, and separated by a narrow strait lies on the East opposite to New Guinea, only known so far by a few shores because after one voyage and another that route has been given up and unless sailors are forced and driven by stress of winds it is seldom visited. The terra Australis begins at two or three degrees below the equator and it is said by some to be of such magnitude that if at any time it is fully discovered they think it will be the fifth part of the world. Adjoining Guinea on the right are the numerous and vast Solomon Islands which lately became famous by the voyage of Alvarus Mendanius.

It will be observed that this translation varies considerably from that given by Major in Early Voyages, p. lxix.

Wytfliet's statement, made in his book published as early as 1597, is so very definite that it is difficult to believe he was not in possession of some actual information on which to base it. On the other hand the strait is laid down on his maps in the latitude of 18° to 22° S., whereas the actual position of Torres Strait is approximately 9° to 11° S. Hence it would appear that whatever knowledge Wytfliet possessed was merely suppositional. On the contemporary English map by Emmerie Mollineux, published by Hakluyt in his Principal Navigations in 1599, and generally considered to be the most accurate world-map made up to that date, the south side of New Guinea is shown incomplete and there is no sign of Terra Australis incognita. Hence it may fairly be concluded that nothing definite was then known about the south side of New Guinea and the strait between it and Australia, or Hakluyt would have caused the details to be shown on his map.

{Page 21}

In the year 1602 a Portuguese pilot and navigator, Captain Fernandez de Quiros (often cited as De Quir), who had already made several voyages in the Pacific Ocean, laid before the Court of Spain a grand project for a new voyage of exploration in southern waters, in the hope of finding the rumoured great Antarctic Continent of Terra Australis or other lands and islands. After many months of negotiation, he so impressed the Spanish Court with his own firm belief in the existence of such a continent, and the great importance to Spain of its discovery (not only in the acquisition of new territory, but also in the glory of the conversion of the inhabitants to the true faith), that King Philip III eventually looked with favour on his proposals. By Royal Orders dated March 1603 the Viceroy of Peru was directed to furnish Quiros with two suitable ships, properly equipped for the purpose of enabling the projected voyage to be undertaken.

Quiros set out from Spain for Peru in the summer of 1603, but having been delayed on the way by shipwreck and other unexpected causes, he did not arrive in Lima till March 1605, and it was December 21 in that year before he actually sailed on his momentous voyage from Callao, the Port of Lima. The expedition consisted of two ships and a small launch or tender. The senior ship bore the name San Pedro y San Pablo and was commanded by Quiros himself, with Captain Don Diego de Prado y Tovar (the writer of the newly discovered manuscript) as second in command. The second ship named the San Pedrico was under the charge of Captain Luis Vaez de Torres. The launch was named Los Tres Reyes and was captained by Pedro Bernal de Cermeño.

{Page 22}

Quiros and Torres, attended by the launch, sailed in company towards the west-south-west, discovering many small islands on their way, until on May 1, 1606, they found themselves in a large bay, which Quiros named St Philip and St James, on the north side of a large island which he mistook for continental land and to which he gave the name of Austrialia del Espiritu Santo. It seems that Quiros and Prado could not agree, so that some few weeks before the ships arrived at Espiritu Santo, Prado, by his own desire and with the consent of Quiros, had transferred himself to the San Pedrico, at the Island of Taumaco, and consequently was henceforth associated with Torres. [Vide Prado's account of this incident quoted on p. 29.]

The ships remained for several weeks in the Bay of St Philip and St James, exploring in all directions, until on June 11 Quiros' ship, the San Pedro y San Pablo, broke away in a gale and never afterwards rejoined the San Pedrico and the launch. The island of Espiritu Santo was the nearest point to the great continent of Australia (some fourteen hundred miles away) ever reached by Quiros personally. For instead of returning to the bay, or proceeding to the island of Santa Cruz, the rendezvous he had himself appointed in case of the separation of the ships(*), he shaped his course to the north and east and returned to America, arriving at Acapulco on November 23, 1606. The mystery of the reasons which caused Quiros suddenly to abandon the voyage and return to America has never hitherto been satisfactorily explained. No less than three different narratives of the voyage of Quiros as far as the island of Espiritu Santo and his return to America are in existence(**), but not one of these offers any adequate explanation, probably for the reason that they were all more or less inspired by Quiros himself.

[* Cf. Markham, pp. 184-5.]

[** All printed by Markham]

{Page 23}

As to what happened to the San Pedrico and the launch after the departure of Quiros, and how the voyage was continued and completed, very little has been known up to the present. All the evidence hitherto available was derived from a letter which Torres wrote to the King of Spain from Manila in July 1607, and from four maps made by Prado in 1606 now preserved at Simancas, or from two very short letters which Prado sent home to the King from Goa in 1613(*). From Torres' letter we learn that they remained in the bay for fifteen days, when finding Quiros did not return "we took Your Majesty's orders and held a consultation with the officers of the launch. It was determined that we should fulfil them"(2). Accordingly they proceeded as far south as 21° S. Lat. in search of new lands, and not finding any, they followed their instructions and turned to the north, shaping their course for Manila. They were evidently intending to proceed on the direct known course to the north of New Guinea, but Torres tells us in his letter that after falling in "with the beginning of New Guinea,...I could not weather the east point, so I coasted along to the westward on the south side"(**), that is to say on the side directly opposite to Australia. To that lucky chance of failing to weather the east point of New Guinea we owe the unconscious discovery of Australia. Torres of course had no idea of the importance of the discoveries which were being made to the south of New Guinea, for he devotes only a few lines to the mention of this part of the voyage. But from the very meagre details he does give, many geographers are agreed in supposing that in addition to discovering "islands without number" in the strait, he must actually have sighted the great continent of Australia, having presumably mistaken the narrow northern point of Cape York for a large island. Torres definitely mentions that before they could get clear of the shoals they sailed as far south as 11° S. Lat., which is considerably farther to the south than the latitude of Cape York. All doubts and suppositions on these points are resolved by the lengthy details given in Prado's Relación.

[* Vide Appendix II.]

[** Burney-Markham version.]

{Page 24}

(Continued from page 15.)

An account has already been given in the editor's preface as to how this most important manuscript was recovered after having been lost to sight for more than three hundred years, and how it was identified as being wholly in the handwriting of Prado.

The manuscript is foolscap folio in size and consists of sixteen leaves, very closely and neatly written on both sides, making thirty-two pages in all, containing in the Spanish about nineteen thousand words, equivalent in the English translation to about twenty-two thousand seven hundred and fifty words. In condition it is clean and sound, doubtless due to the fact that it has been preserved with numerous other Spanish manuscripts stitched together and bound in a limp vellum cover, perhaps two hundred years or more ago.

As the present volume must necessarily be largely supplementary to the Voyages of Quiros edited by the late Sir Clements Markham in 1904(*), it has been thought desirable to print it in the same size (viz. demy 8vo). To reproduce the entire manuscript in facsimile in the size of the original (foolscap folio) would defeat that object, and would moreover add greatly to the cost of the volume. Furthermore the manuscript, although very clear and legible, is somewhat difficult to read owing to the spelling of the period, and the numerous contractions used. Hence it has been thought best to print it in the form of a transliteration into modern Spanish with the contractions expanded. The first and last pages of the manuscript are reproduced in reduced facsimile as illustrative plates (Vide pp. 85 and 206).

[* Vide footnote, p. 10.]

{Page 25}

The title-heading(*) (translated) reads as follows:

JESUS MARIA JOSEPH

Summary relation of the discovery begun by Pero Fernandez de Quiros, a Portuguese, in the Southern Sea in the southern parts up to the island of Irenei called by him the Great Astrialia of the Holy Spirit, and completed for him by Captain Don Diego de Prado, now a monk of our father Saint Basil the Great of Madrid, with the help of Captain Luis Baes de Torres in the ship San Pedrico in the year 1607(**) up to the city of Manila on the 22 of May of the said year, to the honour and glory of the omnipotent God, Amen.

[* Vide the facsimile on p. 85.]

[** Cf. p. 42 and facsimile on p. 85.]

Just above Prado's title-heading the following inscription in Spanish (but here translated) appears in a later hand(*), doubtless written before the volume was bound. It was evidently intended as a filing-heading, after the manner of an ordinary endorsement.

[* Vide the facsimile on p. 85.]

Discovery made by Pero Fernandez de Quiros in the Southern land, and completed for him by Don Diego de Prado who was afterwards a monk of the Order of S. Basil.

About one-quarter of the manuscript relates to events which took place whilst Prado was still associated with Quiros as captain in the San Pedro y San Pablo. A small portion describes what happened between the time of Prado's transference to the San Pedrico about the middle of April 1606, and the separation of the ships on June 11. The remainder gives a detailed account of his continuation of the voyage to Manila in company with Torres. It will thus be seen that about three-quarters of the whole manuscript is virgin material.

{Page 26}

The geographical record given by Prado in the first part of the manuscript, of the discoveries made prior to the separation of the ships, covers much the same ground as the existing narratives inspired by Quiros. But Prado's Relación was written from an entirely independent point of view, hence the details he gives of certain events vary considerably from the other accounts. The chief interest of his graphic narrative, down to the time of the separation of the ships, lies, however, in the lengthy personal details he gives of the character and actions of Quiros. Although his statements may not be considered absolutely impartial, it must be admitted that they are apparently written in good faith and in straightforward and definite terms. Moreover they confirm in a remarkable manner certain other contemporary independent documents which undoubtedly cast grave doubts on the bona fides of Quiros. (Cf. the Letter of Torres, the Memorial of Dr Juan Luis Arias, the Memorial of Don Fernando de Castro, etc., etc., all printed by Markham.)

Notwithstanding that Markham refers to all these various documents, he sums up Quiros as a very skilful pilot--a great navigator and idealist, but unfortunate in his enterprises in not meeting with due recognition and recompense for his great services--and a hardly used man, worn out by years of wearisome and unsuccessful solicitation at the Court of Spain for further employment as commander of another expedition to attempt further discoveries in the Southern Seas. Entirely new and important information explaining the reasons why Quiros met with such ill success at Court after his return from his expedition of 1606, has come to hand in a Report of the Council of State to the King in 1608, a copy of which has just (July 1929) been secured from Spain and which is fully described on pp. 55-6 infra.

There has always been much uncertainty as to the reasons which caused Quiros so suddenly to abandon his expedition and return to America, leaving the other two ships to continue the voyage. A document preserved in the British Museum, the Memorial of Dr Juan Luis Arias to Philip III King of Spain, written about 1615, states the case most concisely even at that early date. (Vide Markham, p. 525.)

{Page 27}

For certain reasons (they ought to have been very weighty) which hitherto have not been ascertained with entire certainty, Pedro Fernandez de Quiros left the Almiranta [i.e. Torres' ship] and the launch in the said bay [i.e. the Bay of St Philip and St James] and himself sailed with his ship the Capitana for Mexico, &c., &c.

This doubt existing as early as 1615 has never been fully resolved until the recent recovery of Prado's manuscript. Markham, evidently basing his introductory story on the existing narratives, merely implies that the breaking away of Quiros' ship was unavoidable, for the reason that Quiros himself was too ill to come on deck and that the pilots, losing their heads in the confusion caused by the storm, eventually stood out to sea before the wind and, being unable to regain the Bay, decided to return to America(*). Torres in his letter to the King from Manila, July 12, 1607, tells a very different tale(**), as also does Prado in his letter to Antonio de Arostegui, the King's secretary, dated from Goa, December 24, 1613(***). In this letter Prado definitely states that the crew mutinied and carried off the ship with Quiros as prisoner. Markham, commenting on the fact that Quiros does not mention any actual mutiny, merely states that "his enemy Prado y Tovar, who must have got his information from the men who remained at Mexico, and perhaps afterwards found their way to the Philippines, makes the assertion ". But Markham does not seem to attach the slightest credence to this assertion of Prado, although in the same letter he (Prado) speaks of the incipient mutiny whilst he was still on board the Capitana with Quiros. Here are Prado's own words: "I knew what took place on board, took part in it, and as it was not in conformity with the good of the service of Your Majesty I could not stay. So I disembarked at Taumaco and went to the Almiranta [i.e. Torres' ship] where I was well received".

[* Vide Markham, pp. xxv and xxvi.]

[** Vide Appendix I]

[*** Vide Appendix II]

{Page 28}

Here then is the reason for finding Prado associated with Torres in the second ship. In the newly discovered manuscript Prado relates this incident in detail, telling how he and Torres had continually remonstrated with Quiros about his actions and warned him of the imminent mutiny, until at last he (Prado) was so disgusted at Quiros' dilatoriness and inattention to the orders he had received for the King's service that he craved permission, which was granted, to remove to Torres' ship. The transference took place about the middle of April 1606.

Markham seems to have formed a most unfavourable opinion of the character of Prado, in fact he goes so far as to accuse him of "stirring up mutiny and disaffection on board" (Markham, p. xxii). Again on p. xxix he describes him as a mutinous officer who was "sent on board the Almiranta" by Quiros. On pp. xxxii and xxxiii, when mentioning the letters and maps sent home by Prado from Goa, Markham returns to the attack and describes him as "the malignant enemy of Quiros" and further states that "the abuse of Quiros by this insubordinate officer can be taken for what it is worth".

It is submitted that from the evidence existing at the time, all of which he exhibits in his book, Markham does not seem to have had any adequate foundation for such very severe condemnation. He appears to have erroneously assumed that Prado must have been a mutinous officer simply because, by his own statement, he left the Capitana and went to the Almiranta, but it makes all the difference in the world whether he transferred himself by permission or was "sent on board the Almiranta" by Quiros, as Markham definitely states. In the quotation from his letter given above, Prado, after referring to the mutiny, simply says: "So I disembarked at Taumaco and went to the Almiranta where I was well received ". The new Relación explains in full the circumstances of the transference and the reasons for it, and clearly shows that Prado was anything but a mutinous officer. Instead of stirring up mutiny he seems to have done his best to quell it. Here is the story told in his own words:

{Page 29}

Captain Don Diego de Prado knowing for certain that the men of the Capitana were going to mutiny informed the said Quiros by way of confession through the Father Commissary of the Franciscans, who told the said Don Diego that he also knew it and had informed him [i.e. Quiros] and would do so again, but the said Quiros took no notice of it, so the said Don Diego, seeing the little remedy that was to be expected, asked leave of the said Quiros to pass to the Almiranta...he granted it to get rid of the bother...The said Don Diego knew who were the mutineers and how they wanted him for head, but he did not want to mix in such conflicts and lose the honour which he had gained in the service of his Majesty, so he at once shifted his things to the Almiranta, whereat the Captain thereof [i.e. Torres] was very pleased. The next day the surgeon did the same. [Vide pp. 112-13.]

Prado's narrative is so circumstantial and clear throughout that it may be said to carry conviction with it, and its truth is largely corroborated by the aforementioned existing independent evidence. Surely, as no adequate reason has ever been given for the defection of Quiros at Espiritu Santo, no one who reads Prado's account (as quoted above) of the imminent mutiny at the time he left the Capitana, can have any doubt that the mutineers carried off the ship at the time of the storm on June 11 and compelled Quiros to return to America. This view is amply confirmed by the account given by Prado near the end of his Relación, derived from information he received after he reached Manila from some sailors who had been in the Capitana at the time and had returned with Quiros to America and had since voyaged to the Philippines. (Vide pp. 194-7.)

Little has hitherto been known of Prado beyond the very brief mention made of him in the narratives of Belmonte Bermudez, Leza and Torquemada. But even before the recovery of Prado's Relación, his two short letters sent home from Goa in 1613, addressed to King Philip III and to the King's secretary, Antonio de Arostegui, make very grave charges against the character and actions of Quiros.

{Page 30} Markham seems to have regarded these letters merely as the ex parte abusive statements of a mutinous officer, and yet he admits the great interest and value of the four maps made by Prado in 1606. In his detailed account of them Markham states (pp. 469-73) that "all the maps are signed by Diego de Prado y Tovar, who thus claims to be their author. The surveys were no doubt made by Torres himself or by his Chief Pilot Fuentidueñas". Markham further testifies to the accuracy of these maps as proved by comparison with the surveys of modern times. Now if the accuracy of the maps is thus proved and admitted, what reason can there be for doubting the truth and accuracy of the descriptive legends upon them(*) which are largely amplified in detail by the new manuscript Many of the places marked on the maps are mentioned in the Relaciòn, as hereinafter noted. Again, if the accuracy of the maps and their descriptions is admitted, what reason can there be for questioning the truth of the other statements about Quiros made by Prado in his letters to the King, the details of which are fully set forth in the new manuscript? When we remember that Quiros returned direct to Mexico after the separation of the ships instead of proceeding to Manila (thereby entirely ignoring the orders and instructions he had himself promulgated for the conduct of the expedition in such an event, and also contravening the sealed orders given by the Viceroy of Peru for the conduct of the expedition in case of the separation of the ships (Vide infra, p. 34), what reason can there he for doubting the very circumstantial account given by Prado as to what took place, especially when it is corroborated by the independent statements of Torres, Arias, Castro, Iturbe and others? (Cf. Markham, pp. 525, 508, xxix, xxxiii, etc., etc.)

[* Vide Appendix III; also Markham, pp. 470-3.]

{Page 31}

The truth and accuracy of the statements made by Prado being once established, it is obvious that an entirely different estimate must henceforth be formed of the character of Quiros, whose name can no longer be held to merit the exalted position it now occupies in the annals of the world's greatest pioneer discoverers. On the other hand Don Diego de Prado y Tovar becomes revealed to the world as a great captain and discoverer, whose name has never yet received due recognition. He must in future be placed in the ranks of the great navigators and his name, henceforth freed from obloquy, coupled with that of Torres as joint discoverer of Australia.

The character of Prado has been assailed by other writers since Markham's time. For instance the late Mr Robert Logan Jack in his extensive work Northmost Australia, published in 1921(*), with no more evidence than was possessed by Markham in 1904, was yet able to heap additional discredit on Prado. It is the old story of giving a dog an ill name, when each succeeding writer takes for granted the accuracy of the deductions of his predecessors, and enlarges upon them without making any attempt at an independent re-examination of the basic facts.

[* Jack, Robert Logan. Northmost Australia. Three centuries of exploration, discovery and adventure in and around the Cape York Peninsula Queensland. 2 vols. Royal 8vo. London, 1921.]

Here is what Jack says of Prado:

The insubordination on the flagship had to be dealt with. The ringleader was the Chief Pilot, or Captain, Juan Ochoa de Bilbaho, for whom Quiros considered that a sufficient punishment was to be relieved of his office and sent on board the Almarinta...A bitterly spiteful enemy of Quiros, and necessarily a supporter of the disrated Captain, was Diego de Prado y Tobar, who according to his own account, voluntarily accompanied Ochoa and boarded the Almiranta at Toumaco. In allowing an officer of the flagship to desert openly and to side with a degraded malcontent, it seems to me that Quiros displayed a weakness which was most reprehensible...The assertion [by Prado] that he was Captain is sheer impudence, as there can be no question that the Captain was Ochoa. Prado was perhaps a "mate" of some sort. [Jack, p. 13.]

In another place (p. 15), Jack speaks of "the outrageous conduct of Prado".

{Page 32}

Here is manufactured history with a vengeance. Let us analyse it. The reader is invited to collate these wild extravagant stories of Jack and the somewhat milder censures of Markham, with the letters of Prado and Torres printed in the Appendix (which constitute all the evidence which either of those writers had to go upon), and then to form his own opinion as to whether or not their aspersions are justified. Not a word of discredit is thrown on Prado in the narratives of Belmonte Bermudez, Leza and Torquemada. As far as the writer is able to judge there is no foundation whatever for Jack's statement that Prado was a supporter of the "disrated Captain Ochoa", or that he "according to his own account voluntarily accompanied Ochoa and boarded the Almiranta". Prado made no such statement, for Ochoa is not even mentioned in either of his two letters. Neither is there any ground for the charge that Prado deserted openly, nor is there any evidence that Ochoa was captain. Prado was certainly captain, as he himself states, whilst Ochoa was merely chief pilot, and is frequently mentioned as such in the existing narratives. In confirmation we now have the definite statement in the certificate appended to Prado's Relacidn where Juan Ochoa de Vilbao is described as "chief pilot of this expedition ". (Vide infra, p. 37. Cf. also p. 89.)

Prado's newly recovered Relación definitely refutes all the obloquy cast upon his name and further shows that his two letters from Goa were accurate in their statements. It is therefore now evident that the tenor of those letters was misinterpreted by historians, who, preferring to believe the narratives of the associates of Quiros, necessarily discredited Prado, as both versions could not be true.

{Page 33}

The writer, standing in the position of sponsor, as it were, for the newly discovered Relación, has felt it his bounden duty to employ every possible means of refuting absolutely the calumnies hitherto showered upon Prado. What credence could possibly be claimed even for such a wonderful narrative as the Relación whilst its author was held to be the disreputable person characterised by modern historians?

Fortunately, from the internal evidence of the new manuscript and from independent genealogical and heraldic researches, a very different estimate can now be formed of the true character of this much-maligned man. Captain Don Diego de Prado y Tovar, to give him his full title, belonged to one of the noblest families of Madrid, and was a Knight of Calatrava, one of the oldest and most distinguished of Spanish Orders of Chivalry, founded in 1158. He was undoubtedly the most important and distinguished person in the whole expedition, far above Quiros and all the other officers in rank and social position, and was actually nominated by the Viceroy of Peru in his sealed orders to succeed to the chief command in case of anything happening to Quiros (Vide infra, p. 34). He evidently had a love for adventure, for he mentions that he had previously served the King in the East and West Indies. With such a record, surely he would have been the very last person to have stirred up mutiny as Markham suggests. Moreover it is a significant fact that in neither of the existing narratives is the slightest complaint or censure of his behaviour expressed. His position at the commencement of the expedition was captain of the San Pedro y San Pablo, that is to say he was second in command to Quiros himself, whilst Torres was captain in a similar position in the second ship, the San Pedrico. Prado's disagreements with Quiros, and the reasons which caused him to transfer to the San Pedrico, have already been explained.

{Page 34}

It must now be recorded how Prado came to succeed to the supreme command over the head of Torres, after the separation of the ships on June 11, 1606, a fact entirely new to history. Prado tells us that Torres, after searching in vain for the San Pedro y San Pablo, held a council, when it was decided to wait in the Bay of St Philip and St lames until June 20, to see if Quiros returned or whether any traces of the wreck of his ship could be found. Meanwhile they searched the coast in both directions, but found nothing. The sequel is best told in Prado's own words.

On the 25th [June], S. John's Day, Luis Baes [i.e. Torres] again summoned a council and produced a closed and sealed paper, and said it was from the Viceroy of Peru; in substance it contained and said that in case any of the ships should go astray they should make every effort to go up to 20° of S. altitude and see if there was any land in that region, and not finding itshould go to the city of Manila and wait there for four months for the other ships, as they also carried the same orders; and in case Pedro Fernandez de Quiros should fail they were to take Captain Don Diego de Prado for chief in order that he might direct that voyage...The said Don Diego accepted the charge as committed to him, and thenceforth executed his office [etc.]. [Vide infra, pp. 130-3.]

These sealed orders are absolutely in accordance with the King's mandate to the Viceroy dated May 9, 1603, as given in Quiros' own narrative. (Cf. Markham, pp. 171-2.) Torres himself makes mention of these orders in a somewhat indefinite passage in his Letter, the exact meaning of which has not hitherto been fully realised, because it was not known to what orders he was referring. Speaking of what occurred in the great bay in the island of Espiritu Santo after the departure of Quiros, Torres says:

{Page 35}

I had to return to the Bay to see if perchance they [i.e. Quiros and his men] had returned to it, all this I did for further loyalty in this Bay, and I waited fifteen days for them at the end of which I brought forth Your Majesty's orders and calling a council jointly with the officers of the Launch, it was agreed that we should fulfil them, though against the inclination of many, I might say of the majority, but my condition(*), was different from that of Captain Pero Fernandez de Quiros(**).

[* Condicion in Spanish has the same variety of meanings as in English.]

[** This translation is from the copy of the Spanish text recently obtained from Madrid (Vide pp. 54-5) and printed herewith in Appendix I. It varies considerably from the versions given by Markham and others, with which it should be compared (Vide M. p. 462).]

But Prado, although succeeding to the supreme command, seems to have remained on the best of terms with Torres, and does not appear to have interfered with him in his nautical captaincy. That is to say Prado was now the chief of the expedition, whilst Torres was his captain, exactly in the same position as Prado occupied when he was captain under Quiros, the former chief. This is evident from the fact that on Prado's maps, which bear his name as maker, all the discoveries laid down are attributed to Torres. (Vide the facsimiles and the legends in the Appendix.) In this new manuscript, when speaking of nautical matters, Prado usually uses the plural "we discovered", "we drew out", "we coasted along", etc., etc., but when naming places he generally speaks in the singular, " I gave the island the name of", etc., etc., and when taking possession of any lands in the name of the King of Spain he uses the formula, "I Don Diego de Prado Captain and Chief take possession", etc., etc.

Although it has hitherto been supposed that Torres was in command of the voyage after the separation of the ships, it must be admitted (now that the circumstances of the failure of Quiros have become known) that Prado's succession to the chief command follows the customary course. For Prado was originally the captain of the senior ship and would have been entitled to the chief command by seniority, even if there had been no sealed orders from the Viceroy.

{Page 36}

Throughout his narrative it appears that Prado acted as an honourable man, always carrying out his orders with the sole object of serving faithfully his lord the King. Even after complaining of the conduct of Quiros he was still loyal to him, for, as may be seen from the title-heading of his Relación, he states that it is a "summary relation of the discovery begun by...Quiros...and completed for him by Captain Don Diego de Prado...with the help of Captain Luis Baes de Torres...". He was no egotist, and beyond stating the actual details of the events in which he was concerned, he takes to himself no credit whatsoever for the important discoveries made.

Before giving an abstract of the contents of the Relaciòn it may be as well to describe it more fully in order to indicate that it is in the handwriting of Prado, and to endeavour to show when and for what purpose it was written.