a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

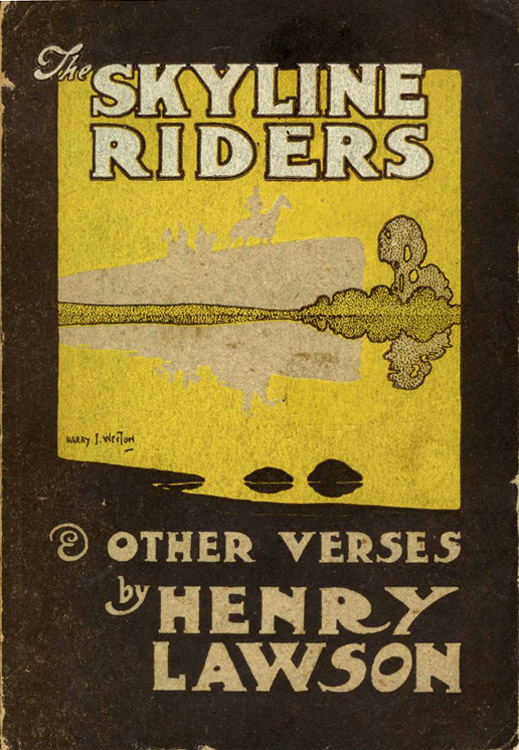

Title: The Skyline Riders and Other Verses Author: Henry Lawson * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 0607541h.html Language: English Date first posted: August 2020 Most recent update: August 2020 This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

Introduction

The Skyline Riders

“Outside”

Do They Think That I Do Not Know?

Somewhere Up in Queensland

Down the River

Success

Billy of Queensland

The Lily and the Bee

William Street

The King of Our Republic

The Bonny Port of Sydney

“Broken Axletree”

Clinging Back

The Memories They Bring

Above Lavender Bay

He Had so Much Work to Do

The Foreign Drunk

Cromwell

The Imported Servant

At the Beating of a Drum

Nineteen Nine

Grace Jennings Carmichael

The Old, Old Story and the New Order

The Briny Grave

Bonnie New South Wales

Sheoaks That Sigh When the Wind

is Still

The Men Who Stuck to Me

The Heart of the Swag

The Men Who Made Bad Matches

“Here Died.”

The Black Bordered Letter

A Bush Girl

“Fall In, My Men, Fall In.”

The Scots

The Song of a Prison

The “Soldier Birds”

Captain Von Esson of the “Sebastopol”

I’d Back Again the World

The Horse and Cart Ferry

The Song of Australia

The Wattle— No Better Right than I

The World is Full of Kindness

As It Was in the Beginning

The Patteran

The King

Ben Boyd’s Tower

Seaweed, Tussock, and Fern

The Rose

“Everyone's Friend”

Handwritten dedication

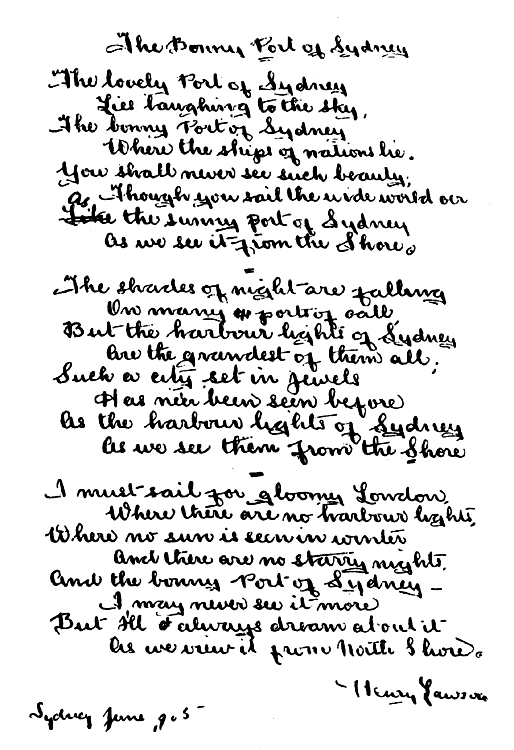

Handwritten “The Bonny Port of Sydney”

An Unconventional Sketch

By J.G.L.

Henry Hertzberg Lawson, one of Australia’s most popular poets, was born at Grenfell, N.S.W., on June 17th, 1867. His early life was spent on the home farm, where he got his first taste of the bitter experiences which so often follow the footsteps of the man on the land. Hardships and pinchings were much more frequent than bumper harvests or big successes. Of luxury or pleasure Lawson knew little or nothing. He was forced to fight every inch of his way. “Cockie” farming is not the easiest of livelihoods. Only the true sons of toil who plod on through year after year of drought and failure, ever striving to hold the bit of a home together, make of it anything like a success. Of those early days Lawson does not say over much. He would rather forget them. Still it is possible to catch many a glimpse of the poet’s home-life from his work. His verses tell the story more forcefully than his tongue. Lawson’s strength lies not in autobiography. When he lifts the pen to picture either bush or city conditions he seldom errs. His experience of both is full and varied.

He “gets there” every time with words that ring true, because they are freighted with stern, hard facts.

Listen to him when he tells you “How the Land was Won,” and in the telling drops in a bit of autobiography—

“They toiled and they fought through the shame

of it—

Through wilderness, flood, and drought;

They worked, in the struggles of early days,

Their sons’ salvation out.

The white girl-wife in the hut alone,

The men on the boundless run,

The miseries suffered, unvoiced, unknown—

And that’s how the land was won.”

—Verses Popular and Humorous.

No man knows this sort of life intuitively. He must live it. No one need ever doubt that Henry Lawson went right through the mill. For better or for worse he took the gruelling like a man.

Leaving the farm, Henry Lawson learnt carriage painting. What sort of a hand he was with the brush I cannot say. It is not often that the poetic temperament can be persuaded to successfully master the uninteresting trade accomplishments.

How and when he began to write, and with what measure of success his work was received by the editors to whom the first lines were sent is another matter on which I have no statement to make. Lawson will tell you all this himself one of these days. He has it written and ready. When the right day comes the manuscript will be carefully edited and be given to the world in book form.

During 1887 Lawson began his connection with the “Bulletin.” It was then that he found the audience he desired. Editor and readers alike were not slow to recognise the strength and ability of the new comer. Here was a man of merit to whom they might reasonably look for something above the average. And Australia did not look to Henry Lawson in vain, for during the winter of 1888 he gave us his true and powerful “Faces in the Street,” which will live for a long time among the very best things done by an Australian hand. If you have not read this poem do so at the earliest opportunity. It is a fine piece of work, full of literary ability and heart. Lawson, at twenty years of age, could see and feel. If there is any heart in you this great poem will find it.

“They lie, the men who tell us in a loud decisive

tone

That want is here a stranger, and that misery’s unknown;

For where the nearest suburb and the city proper meet

My window-sill is level with the faces in the street—

Drifting past, drifting past,

To the beat of weary feet—

While I sorrow for the owners of those faces in the street.

And cause I have to sorrow, in a land so young and fair,

To see upon those faces stamped the marks of want and care;

I look in vain for traces of the fresh and fair and sweet,

In sallow sunken faces that are drifting through the street—

Drifting on, drifting on,

To the scrape of restless feet;

I can sorrow for the owners of the faces in the street.

In hours before the dawning dims the starlight in the sky,

The wan and weary faces first begin to trickle by,

Increasing as the moments hurry on with moving feet,

Till, like a pallid river, flow the faces in the street—

Flowing in, flowing in,

To the beat of hurried feet—

Ah! I sorrow for the owners of those faces in the street.

—In the Days when the World was Wide.

These verses will give you some idea of the work which finds a place of honour in “In the Days when the World was wide,” the earliest of the volumes which carry Henry Lawson’s name. This book was published in 1896, by which time he had a big following, and was rapidly rising into favour. The title poem of the volume mentioned above, which is replete with forceful stanzas that are known throughout Australia, had placed Henry Lawson among the first of our poets. Here are a few verses of this great poem—

“’Twas honest metal and honest wood—in

the days of the Outward bound—

When men were gallant and ships were good—roaming the wide world round.

The gods could envy a leader then, when ‘Follow me, lads!’ he

cried—

They faced each other and fought like men in the days when the world was

wide.

They tried to live as a freeman should—they were

happier men than we,

In the glorious days of wine and blood, when Liberty crossed the sea;

’Twas a comrade true or a foeman then, and a trusty sword well tried—

They faced each other and fought like men in the days when the world was

wide.”

—In the Days when the World was Wide.

“Faces in the Street” Henry Lawson claims to be his masterpiece. Only very recently did he tell me that he was under twenty years of age when he wrote this, his best, poem. I distinctly remember him mentioning the name.

It was in 1896 that I first met Lawson. At this time he and Mr. Le Gay Brereton were engaged putting the finishing touches on “In the Days when the World was Wide,” which Messrs. Angus and Robertson then had in the press. They were working in a back store with galley and page proofs all over a long table, and seemed not to take matters very seriously. It was in that same old store room that Lawson wrote “To an Old Mate,” the introductory poem to his first volume.

You will find in these pages a trace of

That side of our past which was bright,

And recognise sometimes the face of

A friend who has dropped out of sight—

I send them along in the place of

The letters I promised to write.

—In the Days when the World was Wide.

This is Lawson all over.

He is so human. Indeed, he has too much heart. What Lawson suffers through that poetic temperament of his no one but himself can ever fully know. He sees and feels more keenly than you or I can ever hope to do, and through his eyes and his heart he has added materially to the literature of his native land.

There are many people who say they cannot see anything in Henry Lawson’s work. There are always people who find it so much easier to criticise than to praise. Anyone can criticise; very few know just how to express their approval of what they see or read.

Then there is a strong opposition among a certain class to anything Australian. “We live in Australia; give us something that does not smell of the bush,” is frequently heard. And this, too, from people who should know better. It is a good thing that Henry Lawson began his life in the bush. Had he spent his early days in the heart of any of our capitals, he might never have written a line worth reading. His work is a standing rebuke to those who see no good in their own country. Not even his worst enemy could ever say that Henry Lawson has gone back on Australia. He has placed the nation under an obligation which can never be fully paid. He is a man in a million, sent to speak to us of things that our own half-blind eyes fail to see. And how he has spoken! Ever since 1887, when he first got a footing in the “Bulletin,” he has written hard. Now and then he shoots wide of the target, but he generally “gets home” with a clinking “bully.” He many a time phrases a thing in rather an ugly way. That cannot be helped. Eyes are not all focussed alike. Nor are all hearts tuned to the same key. Henry Lawson is fearless and outspoken to a degree which many dislike. Yet it is a good thing that there are men of his stamp in the world. If there were not, many a wrong would go unrighted. In “The Writer’s Dream” (Verses Popular and Humorous) he says:—

‘I was born to write of the things that are! and the strength was

given to me;

‘I was born to strike at the things that mar the world as the world should

be!

‘By the dumb heart-hunger and dreams of youth, by the hungry tracks I’ve

trod—

‘I’ll fight as a man for the sake of truth, nor pose as a martyred

god.

‘By the heart of “Bill” and the heart of “Jim,” and

the men that their hearts deem “white,”

‘By the handgrips fierce, and the hard eyes dim with forbidden tears!

—I’ll write!

And the men of the back country do stand by him. They are his audience and his friends at the same time. Henry Lawson, the man who “humped bluey” with them, is always sure of a warm reception. He is the bushman’s poet every time. The “back blocker” appreciates his work better than I do.

I can tell you a queer incident that will go to show the feeling which exists in the minds of some of the men who follow his work very closely. Lawson was taking a “refresher” or two on North Sydney one night, and got his tongue loosened. More than likely he started, as he often does when he gets a little “jolly,” to roll off “The Ballad of the Rouseabout,” or something of the kind, which one of his audience recognised.

“Where did you learn that?” the listener asked.

“I wrote it,” was the reply.

“A nice chance you’ve got of writing anything like that. That’s Lawson’s.”

“I’m Lawson — Henry Lawson.”

“You lie! Lawson’s a ——” and with this the men came to blows, the poet defending his own name, and his admirer hitting out in defence of the writer he admired.

Being a poet, then, is not all joy, especially when one has to do battle for his own name.

Reverting to the ballad quoted above, I find a passage which holds a lot of truth. Poets, Australian poets in particular, have a way of making their creations tell rather much of their own history. Henry Lawson is no exception to the rule. Of course, it may just happen that there is not the slightest connection between the writer and his rouseabout.

“A rouseabout of rouseabouts, above—beneath

regard,

I know how soft is this old world, and I have learnt how hard—

A rouseabout of rouseabouts—I know what men can feel,

I’ve seen the tears from hard eyes slip as drops from polished steel.

“We hold him true who’s true to one however

false he be

(There’s something wrong with every ship that lies beside the quay);

We lend and borrow, laugh and joke, and when the past is drowned,

We sit upon our swags and smoke and watch the world go round.”

—Verses Popular and Humorous.

You would like to know how Henry Lawson works? Very fast. He is one of the quickest writers in Australia, and one of the surest. There is no fiddling with every second or third line. Once he sits down to write, his thoughts fly too fast for his pen. There is no striving for rhymes. He finishes verse after verse in one writing. Once he makes a beginning, he invariably goes through to the end.

On one occasion I asked Lawson to write me an ode to an old gum tree. He said he would. Several days after he came to me saying, “I can do that poem for you now, and I’ll call it ‘The Stringy-Bark Tree.’ ” “Right, Henry,” I replied, “start now.” Getting pencil and paper he made himself an impromptu desk in the yard at Angus & Robertson’s, and wrote the following verses, which were first published in “The Amateur Gardener”:—

“There’s a whitebox and pine on the ridges

afar,

Where the ironbark, bluegum, and peppermint are;

There is many another, but dearest to me,

And the king of them all was the stringy-bark tree.

“Then of stringy-bark slabs were the walls of the

hut,

And from stringy-bark saplings the rafters were cut;

And the roof that long sheltered my brothers and me

Was of broad sheets of bark from the stringy-bark tree.

“Now still from the ridges, by ways that are dark,

Come the shingles and palings they call stringy-bark;

Though you ride through long gullies a twelve months you’ll see

But the old whitened stumps of the stringy-bark tree.”

—When I was King, and Other Verses.

It is not one man in a million who can see as much in the old stringybarks which Lawson has turned to such good account. Many of us rather discount the value of these trees. Gums are too common for us. Or is it that we have little or no poetry in our “mind’s eye?”

On another occasion to test his memory I asked him to give me a duplicate copy of a fairly long thing I had purchased for publication in the “Amateur Gardener.” At first he said he could not possibly do what I asked. “Where did you lose it?” he asked. “You know how much I liked that poem. You are always losing something.”

Thinking for a minute, he asked me two questions. They were—“Can you give me the first line?” and “Have you got half-a-dollar?” Answering both questions in the affirmative, a bargain was struck, and Henry went to work. It was not long before he had re-written, word for word, the whole poem. “Now,” said he, as he pocketed the half-crown with a smile, “you just be more careful in future, or I’ll raise my fees.”

Henry Lawson’s work is no trouble to him. It is all inspiration. When he burns the “midnight” oil it is to unburden his mind of something that has been haunting him for days.

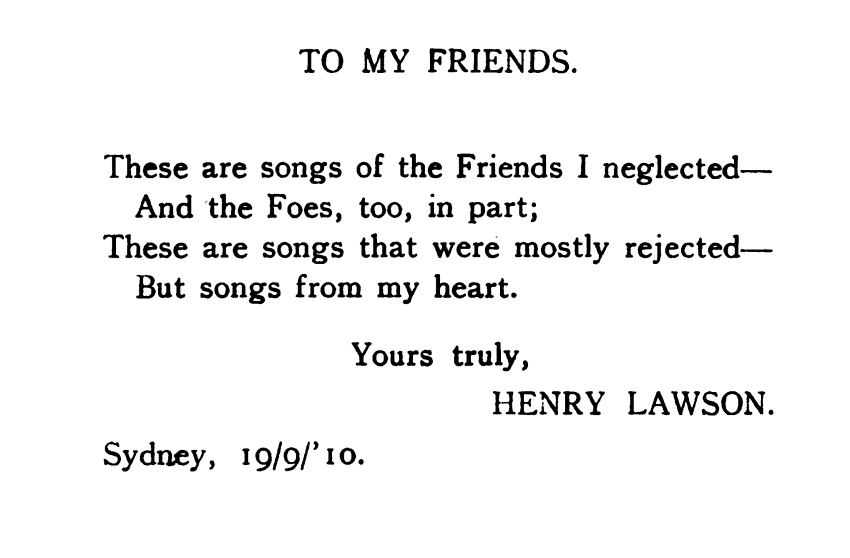

Directly after the last verse, you have two examples of Henry Lawson’s handwriting. The bolder hand was done in 1905, and the smaller writing during 1909.

Speaking about estimating the value of a poet’s work (and it is on this point that I wish to say something to those who criticise Henry Lawson), Frederick Harrison says:—In our estimate of poetry we must avoid the reckoning up of blunders such as examiners score with blue pencil and use to subtract marks. . . . We have to take into account the sum of truly fine things, the permanent harvest of beauty, power, and insight contained in them, of a kind which is independent of place, time, and fashion. And in weighing it in this measure we have to admit that uniform grace and polish do not constitute in themselves a claim to the highest rank of poetry. . . . In the Day of Judgment, they tell us, gross offences may be forgiven for the sake of transcendent merits, which will outweigh a long life of decorous virtue such as needs no expiation.

If the critics will bear these facts in mind they will do better work. Some of them may even be inclined to forget that they are judges of poetry.

But what does it matter whether a man here and there thinks that Henry Lawson, or any other writer, is past his prime? The final court of appeal after all is the “man in the street,” or the man in the bush. What he fancies he will have. Your recommendations or mine he takes but little notice of. It is enough for him to know that his favourite wrote the poem he is doing his best to commit to memory. Against this sort of thing criticisms do not count.

Lawson’s fame is firmly rooted. His popularity must increase. To-day he belongs to Australia. Some day he will be known the whole world round. His work is too human to be soon forgotten. He has written whole-souledly of things which men and women know to be true. He has given us quite a big sheaf, in which there are many ears full of golden grain. He has pictured the hard working men and women as few other pens have ever done. But unfortunately Australia does not appreciate him as she ought. You can help to remedy this. Let this small volume, and this hastily written and very imperfect introduction, set you thinking how best you can help to bring Henry Lawson into his own. He deserves the best we can give him. His work is a national one. He has done it well. The more I read of him, the more I like him. His follies and his failings notwithstanding, I think Henry Lawson’s books of poems should be in every home in the Commonwealth. Men and women who wish to know what is still happening in their own land will find much that is strong, and not a little that is wonderfully sweet in its weakness, in the verses which have placed Henry Lawson at the head of our truly Australian Poets.

A verse or two from “The Last Review” and I have finished:—

“Turn the light down, nurse, and leave me, while

I hold my last review.

For the bush is slipping from me, and the town is going, too;

Draw the blinds, the streets are lighted, and I hear the tramp of feet—

And I’m weary, very weary, of the Faces in the Street.

I was human, very human, and if in the days misspent

I have injured man or woman, it was done without intent;

If at times I blundered blindly—bitter heart and aching brow—

If I wrote a line unkindly—I am sorry for it now.”

—When I was King, and Other Verses.

In closing, let me make one last appeal. Read your Lawson. If you do not like the sordid and the ugly, turn to the humorous things, and the clean things, of which there are many in the volumes published. You will never regret the time you spend in company with this versatile and powerful Australian.

J.G.L.

Against the light of a dawning white

My Skyline Riders stand—

There is trouble ahead for a dark year dead

And the selfish wrongs of a land;

There are hurrying feet of fools to repeat

The follies of Nineteen Eight,

But darkly still on each distant hill

My riders watch and wait.

My Skyline Riders are down and gone

As far as the eye can see,

And the horses stand in the shades of dawn

Where a single man holds three.

We feel the flush and we feel the thrill

Of the coming of Nineteen Nine,

For my Skyline Riders are over the hill

And into the firing line.

The skyline lifts while a storm-cloud lowers—

What’s that? A shot! All’s well!

There is news out there for this land of ours

That the tattling rifles tell.

A “thud” and a “thud” and a flash like blood!

There is light on the land at last!

Australian guns on the nearer hills

Are talking about the past.

O, a lonely place in the days gone by

Was the long first firing line,

Where we fought as strangers, you and I,

For the land that was yours and mine.

There was time to dream in the firing line,

There was time to starve and die,

When the only things in that world of mine

Were my Native Land and I.

O, a lonely place was the firing line

When the gaps were wide between—

Hundreds of miles, in this land of mine

And never a soldier seen.

The dying must die and the dead were left

Unmarked by the deadly tired—

When struck to the heart in a firing line

Where never a shot was fired.

O, a lonely place was the firing line

In the days of the dearth of men,

But hundreds and hundreds of soldiers’ sons

Have flocked to the line since then

We left it weak in the hour of pride,

When our rule seemed firmly set,

But danger threatened the firing line,

And there’s deadly danger yet.

Proud of virtue, and proud of sin,

Or proud ’neath a cruel wrong;

Proud in failure or proud to win—

Oh, the pride of man is strong!

Proud of gold or of being without

Or proud of women and wine—

But get you down from your horse of pride

And into the firing line.

Pride in poverty—all the same—

There’s work for all men to do,

With wrong to fight there is deathless fame

To win in a land so new.

Preacher and drunkard! and sportsman and bard!

In the dawning of Nineteen Nine—

Saints and sinners! ride hard! ride hard!

They are pressed in the Firing Line.

I want to be lighting my pipe on deck,

With my baggage safe below—

I want to be free of the crowded quay,

While the steamer’s swinging slow.

I want to be free of treachery,

And of sordid joys and griefs—

To be out of sight of the faces white,

And the waving of handkerchiefs.

I want to be making my ship-board friends,

I want to be free of the past—

I want to be laughing with kindred souls,

While the Heads are opening fast.

I want to be sailing far to-day,

On the tracks where the rovers go,

To feel the heave of the deck, and draw

The breath that the rovers know.

They say that I never have written of love,

As a writer of songs should do;

They say that I never could touch the strings

With a touch that is firm and true;

They say I know nothing of women and men

In the fields where Love’s roses grow,

And they say I must write with a halting pen—

Do you think that I do not know?

When the love-burst came, like an English Spring,

In the days when our hair was brown,

And the hem of her skirt was a sacred thing

And her hair was an angel’s crown.

The shock when another man touched her arm,

Where the dancers sat round in a row;

The hope and despair, and the false alarm—

Do you think that I do not know?

By the arbour lights on the western farms,

You remember the question put,

While you held her warm in your quivering arms

And you trembled from head to foot.

The electric shock from her finger tips,

And the murmuring answer low,

The soft, shy yielding of warm red lips—

Do you think that I do not know?

She was buried at Brighton, where Gordon sleeps,

When I was a world away;

And the sad old garden it’s secret keeps,

For nobody knows to-day.

She left a message for me to read,

Where the wild wide oceans flow;

Do you know how the heart of a man can bleed—

Do you think that I do not know?

I stood by the grave where the dead girl lies,

When the sunlit scenes were fair,

And the white clouds high in the autumn skies,

And I answered the message there.

But the haunting words of the dead to me

Shall go wherever I go.

She lives in the Marriage that Might Have Been—

Do you think that I do not know?

They sneer or scoff, and they pray or groan,

And the false friend plays his part.

Do you think that the blackguard who drinks alone

Knows aught of a pure girl’s heart?

Knows aught of the first pure love of a boy

With his warm young blood aglow,

Knows aught of the thrill of the world-old joy—

Do you think that I do not know?

They say that I never have written of love,

They say that my heart is such

That finer feelings are far above;

But a writer may know too much.

There are darkest depths in the brightest nights,

When the clustering stars hang low;

There are things it would break his strong heart to write—

Do you think that I do not know?

He’s somewhere up in Queensland,

The old folks used to say;

He’s somewhere up in Queensland,

The people say to-day.

But Somewhere (up in Queensland)

That uncle used to know—

That filled our hearts with wonder,

Seems vanished long ago.

He’s gone to Queensland, droving,

The old folks used to say;

He’s gone to Queensland, droving,

The people say to-day.

But “gone to Queensland, droving,”

Might mean, in language plain,

He follows stock in buggies,

And gets supplies by train.

He’s knocking round in Queensland,

The old folks used to say;

He’s gone to Queensland, roving,

His sweetheart says to-day.

But “gone to Queensland, roving”

By mighty plain and scrub,

Might mean he drives a motor-car

For Missus Moneygrub.

He’s looking for new country,

The old folks used to say;

Our boy has gone exploring,

Fond parents say to-day.

“Exploring” out in Queensland

Might only mean to some

He’s salesman in “the drapery”

Of a bush emporium.

To somewhere up in Queensland

Went Tom and Ted and Jack;

From somewhere up in Queensland

The dusty cheques come back:

From somewhere up in Queensland

Brown drovers used to come,

And someone up in Queensland

Kept many a southern home.

Somewhere up in Queensland,

How many black sheep roam,

Who never write a letter,

And never think of home.

For someone up in Queensland

How many a mother spoke;

For someone up in Queensland

How many a girl’s heart broke.

I’ve done with joys an’ misery,

An’ why should I repine?

There’s no one knows the past but me

An’ that ol’ dog o’ mine.

We camp an’ walk an’ camp an’ walk,

An’ find it fairly good;

He can do anything but talk,

An’ he wouldn’t if he could.

We sits an’ thinks beside the fire,

With all the stars a-shine,

An’ no one knows our thoughts but me

An’ that there dog o’ mine.

We has our Johnny-cake an’ “scrag,”

An’ finds ’em fairly good;

He can do anything but talk,

An’ he wouldn’t if he could.

He gets a ’possum now an’ then,

I cooks it on the fire;

He has his water, me my tea—

What more could we desire?

He gets a rabbit when he likes,

We finds it pretty good;

He can do anything but talk,

An’ he wouldn’t if he could.

I has me smoke, he has his rest,

When sunset’s gettin’ dim;

An’ if I do get drunk at times,

It’s all the same to him.

So long’s he’s got me swag to mind,

He thinks that times is good;

He can do anything but talk,

An’ he wouldn’t if he could.

He gets his tucker from the cook,

For cook is good to him,

An’ when I sobers up a bit,

He goes an’ has a swim.

He likes the rivers where I fish,

An’ all the world is good;

He can do anything but talk,

An’ he wouldn’t if he could.

“O! did you see the troop go by,

World-weary and oppress’d,

A dead light in each drooping eye,

And a dead rose on each breast?”

—Rod Quinn.

Did you see that man riding past,

With shoulders bowed with care?

There’s failure in his eyes to last,

And in his heart despair.

He seldom looks to left or right,

He nods, but speaks to none,

And he’s a man who fought the fight—

God knows how hard!—and won.

No great “review” could rouse him now,

No printed lies could sting;

No kindness smooth his knitted brow,

Nor wrong one new line bring.

Through dull, dumb days and brooding nights,

From years of storm and stress,

He’s riding down from lonely heights—

The Mountains of Success.

He sees across the darkening land

The graveyards on the coasts;

He sees the broken columns stand

Like cold and bitter ghosts;

His world is dead while yet he lives,

Though known in continents;

His camp is where his country gives

Its pauper monuments.

“Queensland,” he heads his letters—that’s all:

The date, and the month, and the year in brief;

He often sends me a cheerful scrawl,

With an undertone of ancient grief.

The first seems familiar, but might have changed,

As often the writing of wanderers will;

He seems all over the world to have ranged,

And he signs himself William, or Billy, or Bill.

He might have been an old mate of mine—

A shearer, or one of the station hands.

(There were some of ’em died, who drop me a line,

Signing other names, and in other hands.

There was one who carried his swag with me

On the western tracks, when the world was young,

And now he is spouting democracy

In another land with another tongue.)

He cheers me up like an old mate, quite,

And swears at times like an old mate, too;

(Perhaps he knows that I never write

Except to say that I’m going to).

He says he is tired of telling lies

For a Blank he knows for a Gory Scamp—

But—I note the tone where the sunset dies

On the Outside Track or the cattle camp.

Who are you, Billy? But never mind—

Come to think of it, I forgot—

There were so many in days behind,

And all so true that it matters not.

It may be out in the Mulga scrub,

In the southern seas, or a London street—

(I hope it’s close to a bar or pub)—

But I have a feeling that we shall meet.

I looked upon the lilies

When the morning sun was low,

And the sun shone through a lily

With a softened honey glow.

A spot was in the lily

That moved incessantly,

And when I looked into the cup

I saw a morning bee.

“Consider the lilies!”

But,

it occurs to me,

Does any one consider

The

lily and the bee?

The lily stands for beauty,

Use, purity, and trust,

It does a four-fold duty,

As all good mortals must.

Its whiteness is to teach us,

Its faith to set us free,

Its beauty is to cheer us,

And its wealth is for the bee.

“Consider the lilies!”

But,

it occurs to me,

Does any one consider

The

lily and the bee?

’Tis William Street, the link street,

That seems to stand alone;

’Tis William Street, the vague street,

With terraces of stone:

That starts with clean, cool pockets,

And ancient stable ways,

And built by solid landlords

And in more solid days.

Beginning where the shadow streets

Of vacant wealth begin,

Street William runs down sadly

Across the vale of sin.

’Tis William Street, the haggard,

Where all the streets are mean

That’s trying to be honest,

That’s trying to keep clean.

’Tis William Street with method,

And nought of show or pride,

That tries to keep its business

Upon the right-hand side.

No pavement exhibition

Of carcases and slops;

But old-established principles

In old-established shops.

’Tis William Street the highway—

Whichever way it be—

To business and the theatres,

Or empty luxury.

’Tis William Street (the East-end)—

The world-wise and exempt—

That sells Potts Point its purgatives

With something of contempt.

With fronts that hint of England,

As England used to be,

Old houses once in gardens,

And signs of Italy.

With hints of the forgotten,

Strange Sydney of the past,

When bricks were burnt for all time,

And walls were built to last.

’Tis William Street that rises

From stagnant dust and heat,

(Old trees by the Museum

Hold back with hands and feet)—

And where the blind are plying

Deft fingers, supple wrists—

’Tis William Street, exclusive,

Where pray the Methodists.

The blind courts see the clearer,

Side lanes grow trim and neat,

The wretched streets are cleaner

That run from William Street.

The sick streets’ lonely matron

Seems stern, as matrons do—

’Tis William Street, redeeming,

Regenerating “Loo.”

He is coming! He is coming! without heralds, without

cheers.

He is coming! He is coming! and he’s been with us for years:

And, if you should pause to wonder who’s the man of whom I sing—

’Tis the King of our Republic, and the man we shall call King.

No, he comes not to amuse us, and he comes not to explain,

With the bathos of the old things over all the land again.

The debatable and tangled, and the vain imagining

Shall be swept out of our pathway by the man that we’ll call King.

He is coming! He is coming! He has heard our spirit call;

He’ll be greatest man since Cromwell in the English nations all,

And he’ll take his place amongst us while the rest are wondering—

Shall the King of our Republic, and the man we will call King.

If you find him stern, unyielding, where his living task is set,

I have told you that a tyrant shall uplift the nation yet;

He will place his country’s welfare over all and everything,

Shall the King of our Republic, and the man that we’ll call King.

Yet his heart shall still be gentle with his brothers gone astray,

For the Great Man of Australia shall be simple in his day—

Modest, kindly, but unyielding, while the watching world shall ring

With the name of our Republic and the man that we call King.

The lovely Port of Sydney

Lies laughing to the sky,

The bonny Port of Sydney,

Where the ships of nations lie.

You shall never see such beauty,

Though you sail the wide world o’er,

As the sunny Port of Sydney,

As we see it from the Shore.

The shades of night are falling

On many ports of call,

But the harbour lights of Sydney

Are the grandest of them all;

Such a city set in jewels

Has ne’er been seen before

As the harbour lights of Sydney

As we see them from the Shore.

I must sail for gloomy London,

Where there are no harbour lights,

Where no sun is seen in winter,

And there are no starry nights;

And the bonny port of Sydney—

I may never see it more,

But I’ll always dream about it

As we view it from North Shore.

On the Track of Grand Endeavour, on the long track out to Bourke,

Past the Turn-Back, and past Howlong, and the pub at Sudden Jerk,

Past old Bullock-Yoke and Bog Flat, and the “Pinch” at Stick-to-me,

Lies the camp that we have christened—christened “Broken Axletree.”

We were young and strong and fearless, we had not seen Mount Despair,

And the West was to be conquered, and we meant to do our share;

We were far away from cities, and were fairly off the spree

When we camped at Cart Wheel River with a broken axletree.

Oh, the pub at Devil’s Crossing! and the woman that he sent!

And the hell for which we bartered horse and trap and “traps” and

tent!

And the black “Since Then”—the chances that we never more

may see—

Ah! the two lives that were ruined for a broken axletree!

“Fate” is but a Cart Wheel River, placed to test us by the Lord,

And the Star of Live Forever shines beyond At Blacksmith’s Ford!

Shun all fatalists and “isms”—heed no talk of “destiny”!

Ride a race for life to Blacksmith’s with your broken axletree.

When you see a man come walking down through George Street loose and

free,

Suit of saddle tweed and soft shirt, and a belt and cabbagetree,

With the careless swing and carriage, and the confidence you lack—

There is freedom in Australia! he’s a man that’s clinging back.

Clingin’ back,

Holdin’ back,

To the old things and the bold things clinging back.

When you see a woman riding as I saw one ride to-day

Down the street to Milson’s Ferry on a big, upstanding bay,

With her body gently swaying to the horse-shoes’ click-a-clack,

You might lift your hat (with caution)—she’s a girl who’s

clinging back.

Clinging back,

Swinging back.

To the old things and the bold things clinging back.

When you see a rich man pulling on the harbour in a boat,

With the motor launches racing till they scarcely seem to float,

And the little skiff is lifting to his muscles tense and slack,

You say “Go it” to a sane man. He’s a man that’s

clinging back.

Clinging back,

Swinging back,

To the old things and the bold things clinging back.

When you see two lovers strolling, arm-in-arm—or round the waist,

And they never seem to loiter, and they never seem to haste,

But indifferent to others take the rock or bush-hid track

You be sure about their future, they’re a pair that’s clinging

back.

Clinging back,

Holding back,

To the old things and the bold things clinging back.

I, a weary picture writer in a time that’s cruel plain,

Have been clinging all too sadly to what shall not come again,

To what shall not come and should not! for the silver’s mostly black,

And the gold a dull red copper by the springs where I held back.

Clinging back,

Holding back,

To the old things and the cold things clinging back.

But if you should read a writer sending truths home every time,

While his every “point” goes ringing like the grandest prose

in rhyme,

Though he writes the people’s grammar, and he spreads the people’s “clack,”

He is stronger than the Public! and he’ll jerk the mad world back.

Yank it back,

Hold it back,

For the love of little children hold it back.

I would never waste the hours

Of the time that is mine own,

Writing verses about flowers

For their own sweet sakes alone;

Gushing as a schoolgirl gushes

Over babies at their best—

Or as poets trill of thrushes,

Larks, and starlings and the rest.

I am not a man who praises

Beauty that he cannot see,

But the buttercups and daisies

Bring my childhood back to me;

And before life’s bitter battle,

That breaks lion hearts and kills,

Oh the waratah and wattle

Saw my boyhood on the hills.

It was “Cissy” or Cecilia,

And I loved her very much,

When I wore the white camelia

That will wither at a touch.

Ah, the fairest chapter closes

With lilies white and blue,

When the wild days with the roses

Cast their glamour over you!

Vine leaves fall and laurels wither

(Madd’ning drink and pride insane),

And the fate that sends us hither

Ever takes us back again.

Fading flowers—slow pulsations—

Flowers pressed for memory

But the red and pink carnations

Speak most bitter things to me.

’Tis glorious morning everywhere

Save where the alleys lie—

I see the fleecy steam jets bid

“Good morning” to the sky.

The gullies of the waratah

Are near, with fall and pool,

And by the shadowed western rocks

The bays are fresh and cool.

To “points” that hint of Italy—

Of Italy and Spain—

I see the busy ferry boats

Come nosing round again.

To the toy station down below

I see the toy trains run—

(I wonder when those ferry boats

Will get their business done?)

Above the Bay called Lavender

This bard is domiciled,

Where up through rich, dark greenery

The red-tiled roofs are piled—

(At least some are—I hope that soon

They all shall be red-tiled)—

A moonlight night in middle-age

That makes one feel a child.

Close over, to the nearer left—

That feels the ocean breeze—

A full moon in a dim blue sky

A church spire and dark trees.

And, further right, the harsher heights

Of Mosman, Double Bay,

And Rose Bay, with their scattered lights,

Have softened with the day.

And fair across to where we know

The shelving sea cliffs are—

The lighthouse, with a still faint glow,

Beneath a twinkling star.

Across the harbour from the right,

And fairly in a line,

The Clock-tower on the City Hall,

A ship-mast and a pine.

The pale and bright, yet dusky blue,

And crossed by fleecy bars,

Flings out the brilliant city lights,

The moonlight and the stars—

And like a transformation scene,

On sheet glass down below,

The fairy-lighted ferry boats

Are gliding to and fro.

Tell a simple little story of a settler in the West,

Where the soldier birds and farmers, and selectors never rest

While the sun shines—and they often work in rainy weather, too:

But it’s all about a young man who had so much work to do.

One of Mason’s sons, Jim Mason, and the straightest of the lot,

(They were all straight for that matter) Jim was working for old Scott—

(Scott that fired at Brummy Hughson, when the “stick-ups” used

to be),

Jim was courting Mary Kelly down at Lowes, at Wilbertree.

Jim was trucking for a sawmill to make money for the home,

He was making, out of Mudgee, for the family to come,

And a load-chain snapped the switch-bar, and Black Anderson found Jim,

In the morning, in a creek-bed, with a log on top of him.

There was riding for the doctor—just the same old reckless race:

And a spring cart with a mattress came and took him from the place,

To the hospital at Gulgong—but they couldn’t pull him through—

And Jim said “It seems a pity—I—had so much work to do.”

“There’s the hut—it’s close-up finished; and the

forty acres fenced;

And—I’ve cleared enough for ploughin’, but the dam is just

commenced!”

Then he said—and for a moment from the nurse his eyes he hid—

“But I’m glad we wasn’t married, for there might have been

a kid.”

That was all—at least it wasn’t for he didn’t die until

He had “fixed it up for Mary with a proper lawyer will,”

And the “Forty acre paddick,” “And I only hope,” said

he,

“That she’ll get some decent feller when she’s quite got

over me.”

Poor old broken-hearted Mason and his “missus” took their spell,

But another son and Mary finished Jim’s work very well.

They have grown-up sons and daughters—some on new selections, too,

And their hands and hearts are fitted for the work they have to do.

Now, my brothers! see the moral, lest the truth should come too late!

We are far too apt to quarrel with the writer’s fancied fate—

Damn the Past! and leave to-morrow: millions are worse off than you!

Think, ere you would “drown your sorrow,” of the work that you

should do.

Though the fates have seemed unkind to our unhappy brotherhood,

We are too apt to be blind to our great power to do good;

Many thousands, starved and stinted, for a line of comfort come,

We can write, and have it printed—They must suffer and be dumb.

Think not of the hours we wasted in “oblivion” foully won,

Or the bitter cups we tasted. Let us work! that, when life’s done,

We shall have in bush or city, shaped our future course so true

That they’ll say “It is a pity—they had so much more to

do.”

When you get tight in foreign lands

You never need go slinking,

No female neighbours lift their hands

And say “The brute!—he’s drinking!”

No mischief-maker runs with smiles

To give your wife a notion,

For she may be ten thousand miles

Across the bounding ocean.

Oh! I’ve been Scottish “fu” all night,

(O’er ills o’ life victorious),

And I’ve been Dutch and German tight,

And French and Dago glorious.

We saw no boa-constrictors then,

In every lady’s boa,

Though we got drunk with Antwerp men,

And woke up in Genoa!

When you get tight in foreign lands,

All foreigners are brothers—

You drink their drink and grasp their hands

And never wish for others.

Their foreign ways and foreign songs—

And girls—you take delight in:

The war-whoop that you raise belongs

To the country you get tight in.

When you get tight in a foreign port—

(Or rather bacchanalian),

You need no tongue for love or sport

Save your own good Australian.

(A girl in Naples kept me square—

Or helped me to recover—

For mortal knoweth everywhere

The language of the lover).

When you get tight in foreign parts,

With tongue and legs unstable,

They do their best, with all their hearts

And help you all they’re able.

Ah me! It was a happy year,

Though all the rest were “blanky,”

When I got drunk on lager beer,

And sobered up on “Swankey.”

They took dead Cromwell from his grave,

And stuck his head on high;

The Merry Monarch and his men,

They laughed as they passed by

The common people cheered and jeered,

To England’s deep disgrace—

The crowds who’d ne’er have dared to look

Live Cromwell in the face.

He came in England’s direst need

With law and fire and sword,

He thrashed her enemies at home

And crushed her foes abroad;

He kept his word by sea and land,

His parliament he schooled,

He made the nations understand

A Man in England ruled!

Van Tromp, with twice the English ships,

And flushed by victory—

A great broom to his masthead bound—

Set sail to sweep the sea.

But England’s ruler was a man

Who needed lots of room—

So Blake soon lowered the Dutchman’s tone,

And smashed the Dutchman’s broom.

He sent a bill to Tuscany

For sixty thousand pounds,

For wrong done to his subjects there,

And merchants in her bounds.

He sent by Debt Collector Blake,

And—you need but be told

That, by the Duke of Tuscany

That bill was paid in gold.

To pirate ports in Africa

He sent a message grim

To have each captured Englishman

Delivered up to him;

And every ship and cargo’s worth,

And every boat and gun—

And this—all this, as Dickens says—

“Was gloriously done.”

They’d tortured English prisoners

Who’d sailed the Spanish Main;

So Cromwell sent a little bill

By Admiral Blake to Spain.

To keep his hand in, by the way.

He whipped the Portuguese;

And he made it safe for English ships

To sail the Spanish seas.

The Protestants in Southern lands

Had long been sore oppressed;

They sent their earnest prayers to Noll

To have their wrongs redressed.

He sent a message to the Powers,

In which he told them flat,

All men must praise God as they chose,

Or he would see to that.

And, when he’d hanged the fools at home

And settled foreign rows,

He found the time to potter round

Amongst his pigs and cows.

Of private rows he never spoke,

That grand old Ironsides.

They said a father’s strong heart broke

When Cromwell’s daughter died.

(They dragged his body from its grave,

His head stuck on a pole,

They threw his wife’s and daughter’s bones

Into a rubbish hole

To rot with those of two who’d lived

And fought for England’s sake,

And each one in his own brave way—

Great Pym, and Admiral Blake.)

From Charles to Charles, throughout the world

Old England’s name was high,

And that’s a thing no Royalist

Could ever yet deny.

Long shameful years have passed since then,

In spite of England’s boast—

But Englishmen were Englishmen,

While Cromwell carved the roast.

And, in my country’s hour of need—

For it shall surely come,

While run by fools who’ll never heed

The beating of the drum.

While baffled by the fools at home,

And threatened from the sea—

Lord! send a man like Oliver—

And let me live to see.

The blue sky arches o’er mountain and valley,

The scene is as fair as a scene can be,

But I’m breaking my heart for a London alley,

And fogs that shall never come back to me.

I choke with tears when the day is dying—

The sunsets grand and the stars are bright;

But it’s O! for the smell of the fried fish frying

By the flaring stalls on a Saturday night.

And this, oh, this is the lonely sequel

Of all I pictured would come to pass!

They are treating me here as a friend and equal,

But they’d say in London that they’re no

class.

When I think of their kindness my tears flow faster—

The girls are free and the chaps are grand:

It’s “the boss” and “the missus” for mistress

and master,

And they may be right—But I don’t understand.

I see the air in its warm pulsation

On sandstone cliffs where the ocean dips,

But I’m miles and miles from the railway station

Where trains run down to the wharves and ships.

Those streets are dingy and dark and narrow,

The soot comes down with the rain and sleet;

But, O! for the sight of a coster’s barrow,

And Sunday morning in Chapel Street!

Fear ye not the stormy future, for the Battle Hymn is strong,

And the armies of Australia shall not march without a song;

The glorious words and music of Australia’s song shall come

When her true hearts rush together at the beating of a drum.

We may not be there to hear it—’twill be written in the night,

And Australia’s foes shall fear it in the hour before the fight.

The glorious words and music from a lonely heart shall come

When our sons shall rush to danger at the beating of a drum.

He shall be unknown who writes it; he shall soon forgotten be,

But the song shall ring through ages as a song of liberty.

And I say the words and music of our battle hymn shall come,

When Australia wakes in anger at the beating of a drum.

There’s a light out there in the nearer east

In the dawn of Nineteen Nine;

There’s the old ghost light in the salty yeast

Where the black rocks meet the brine.

Here’s the same old strife and toil in vain—

Here’s the same old hope and doubt—

Here’s the same old useless care and pain—

And the sea is my way out—

My dear—

The sea is my way out.

’Tis a grey and a sad old sea for me—

With a growing grey head too.

Oh, the heads were brown and the eyes were bright

When the sea was white and blue.

It was round the world and home again,

We could turn and turn about,

And the sea means exile now in vain,

But the sea is my way out—

My dear—

The sea is my way out.

“But the broken heart of the poet is written between the lines.”

Grace Jennings Carmichael, bush girl, born in Gippsland, Vic., spent her young life in the bush; went to Melbourne into the Children’s Training Hospital and obtained a certificate. Wrote verses for many years to the Australasian. Died in great poverty in London in 1904. Three younger children (one or more probably Australians) still in a London workhouse.

I hate the pen, the foolscap fair,

The poet’s corner, and the page,

For Grief and Death are written there,

In every land and every age.

The poets sing and play their parts,

Their daring cheers, their humour shines,

But, ah! my friends! their broken hearts

Have writ in blood between the lines.

They fought to build a Commonwealth,

They write for women and for men,

They give their youth, we give their health

And never prostitute the pen.

Their work in other tongues is read,

And when sad years wear out the pen,

Then they may seek their happy dead

Or go and starve in exile then.

A grudging meed of praise you give,

Or, your excuse, the ready lie—

(O! God, you don’t know how they live!

O! God, you don’t know how they die!)

The poetess, whose gentle tone

Oft cheered your mothers’ hearts when down;

A lonely woman, fought alone

The bitter fight in London town.

Your rich to lilac lands resort,

And old-world luxuries they buy;

You pour out gold to Cant and Sport

And give a million to a lie.

You give to cheats who rant and rave

With eyes that glare and arms that whirl,

But not a penny that might save

The children of the Gippsland girl.

The press of Australia and its unspeakable mediocrities have ever had a tendency to belittle its own writers, both as regards their genius and character. The dead have been spared less than the living.

They proved we could not think nor see,

They proved we could not write,

They proved we drank the day away

And raved through half the night.

They proved our stars were never up,

They’ve proved our stars are set,

They’ve proved we ne’er saw sorrow’s cup,

And they’re not happy yet.

They proved that in the Southern Land

We all led vicious lives;

They’ve proved we starved our children, and—

They’ve proved we beat our wives.

They’ve proved we never worked, and we

Were never out of debt;

They’ve proved us bad as we can be

And they’re not happy yet.

The Daily Press, with paltry power—

For reasons understood—

Have aye sought to belittle our

Unhappy brotherhood.

Because we fought in days like these,

Where rule the upper tens—

Because we’d not write journalese,

Nor prostitute our pens.

They gave our rivals space to sneer—

Their mediocrities;

The drunkard’s mind is pure and clear

Compared with minds like these.

They sought to damn with pitying praise

Or the coward’s unsigned sneer,

For honour in the “critics’” ways

Had never virtue here.

They’ve proved our names shall not be known

A few short years ahead;

They hied them back through years of moan,

And damned our happy dead.

A newer tribe of scribes we’ve got,

Exclusive and alone,

To prove our work was childish rot,

And none of it our own.

The cultured cads of First Gem cells,

Of Mansion, Lawn and Club,

Not fit to clean the busted boots

Of “Poets of the Pub.”

They prove the partners of the part,

The wholeness of the whole,

The gizzardness of gizzards, and

The Soulness of the Soul.

They’ve proved that all is nought—but there

Are things they cannot do—

The summer skies are just as fair

And just as brightly blue.

They’ve buried us with muddied shrouds,

When our strong hearts they’ve broke.

They can’t bring down yon fleecy clouds

And make them factory smoke.

They’ve proved the simple bard a fool,

But still, for all their pains,

The children prattling home from school

Go tripping down the lanes.

They’ve proved that Love is lust or hate,

True marriage is no more,

But Jim and Mary at the gate

Are happy as of yore.

These insects seeking to unloose

The Bards of Sympathy!

Who strike with the sledge hammer force

Of their simplicity.

(They cannot turn the world about,

Nor damp the father’s joy,

When some old doctor bustles out,

And nurse says “It’s a boy!”)

They want no God but many a god,

And many gods, and none—

The preacher by the upturned sod

Shall pray when all is done.

Amongst the great ’twas aye the same—

The envious crawler’s part—

The lies that blackened Byron’s name

And banished poor Brett Harte.

We’ve learnt in bitter schools to teach

Man’s glory and his shame

Since Gordon walked along the beach

In search of bigger game.

Maybe, our talents we’ve abused

At times, and ne’er been blind

Since Barcroft Boake went out and used

His stockwhip to be kind.

But laugh, my chums, in prose and rhyme,

And worry not at all,

They’re insects whom the wheels of time

Shall crush exceeding small.

Have faith, my friends, who stand by me,

In spite of all the lies—

I tell you that a man shall die

On the day that Lawson dies.

I notice in “Answers to Correspondents” that the “Bulletin” has no sympathy for, or can’t understand the poet bloke that wishes to be buried at sea. I don’t wish to be buried anywhere just at present, but I’ve seen three such burials, and might be able to throw light on the subject. Give me a show. Quick time:—

You wonder why so many would be buried in the sea,

In this world of froth and bubble,

But I don’t wonder, for it seems to me

That it saves such a lot of trouble.

And there ain’t no undertaker—

Oh! there ain’t no order that your friends can give

On the quiet to the coffin-maker—

To a gimcrack coffin-maker,

They make no differ twixt the absentee swell

And the clerk that cut from a “shortage”—

Oh! there ain’t no pauper funer-el,

And there ain’t no “impressive cortege.”

It may be a chap from the for’ard crowd,

Or a member of the British Peerage,

But they sew his nibs in a canvas shroud

Just the same as the bloke from the steerage—

As that poor bloke from the steerage.

There ain’t no need for a gravedigger there,

For you dig your own grave! Lord love yer!

And there ain’t no use for a headstone fair

When the waters close above yer!

The little headstone where they come to weep,

May be right for the land’s dry-rotters,

But you rest just as sound when you’re anchored deep

With the pigiron at your trotters—

(Our fathers had iron at their trotters).

The sea is democratic the wide world round,

And it don’t give a hang for no man,

There ain’t no Church of England burial ground,

Nor yet there ain’t no Roman.

Orthodox and het’rodox by wreck-strewn cliffs,

At peace in the stormiest weather,

Might bob up and down like two brother “stiffs,”

And rest in one shark together—

And mix up their bones together.

The bare-headed skipper is as good any day

As an authorised shifter of sin is,

And the tear of shipmate is better anyway

Than the tear of the next-of-kin is.

It saves your friends, and it fills your needs,

It is best when all is reckoned,

And she can’t come there in her widder weeds,

With her eyes on a likely second—

And a spot for the likely second.

It surely cannot be too soon, and never is too late,

It tones with all Australia’s tune to praise one’s native State,

And so I bring an old refrain from days of posts and rails,

And lift the good old words again, for Sunny New South Wales.

She bore me on her tented fields, and wore my youth away,

And little gold of all she yields repays my toil to-day;

By track and camp and bushman’s hut—by streets where courage

fails—

I’ve sung for all Australia, but my heart’s in New South Wales.

The waratah and wattle there in all their glory grow—

And if they bloom on hills elsewhere, I’m not supposed to know,

The tales that other States may tell—I never hear the tales!

For I, her son, have sinned as well as Bonnie New South Wales.

I only know her heart is good to sweetheart and to mate,

And pregnant with our nationhood from Sunset to the Gate;

I only know her sons sail home on every ship that sails,

Though round the world ten times they roam from dear old New South Wales.

Why are the sheoaks forever sighing?

(Sheoaks that sigh when the wind is still)—

Why are the dead hopes forever dying?

(Dead hopes that died and are with us still.)

As you make it and what you

will.

Why are the ridges forever waiting?

Ridges that waited ere one man came,

Still by the towns with their life vibrating

Lonely ridges that wait the same.

Ridges and gullies without

a name.

Why is the strong heart forever peering

Into the future that speaks no ill?

Why is the kind heart forever cheering,

Even at times when the fears are still?

As you make it, and what you

will.

Why is the distance forever drawing?

(The wide horizon is round us still!)

Why is resentment forever gnawing

Against a world that may mean no ill?

Why are so many forever sawing

On strings that rasp and can never thrill—Soothe

or thrill?

As you make it, and what you

will.

They were men of many nations, they were men of many stations,

They were men in many places, and of high and low degree;

Men of many types and faces, but, alike in all the races,

They were men I met in trouble, and the men who stuck to me.

Some were friends, but most were strangers; some were weary world-wide rangers;

Some in freedom were in prison, and in prison some were free,

Oh, I have a vivid vision of the men I met in prison—

In the craving for tobacco they were men who stuck to me.

Some I never met and never knew their great but vain endeavour,

For my sake! And some were old mates whom I never more may see;

Never heard me, some I talked with; never saw me, some I walked with;

Blind and deaf, and dumb and foreign were the men who stuck to me.

“Yes, I’ll stick!” the words most human, be the trouble

man or woman;

Stick with money or without it, and whoever you may be;

Right or wrong—in drink or sadness—“stick” in sanity

or madness—

Such as these, the men I stuck to, and the men who stuck to me.

Ah! we see not in our blindness that the world is full of kindness,

Kindness to make full atonement for all evil that there be;

Oh! my life was deadly fateful, but my heart was always grateful,

And I send this song at Xmas to the men who stuck to me.

Oh, the track through the scrub groweth ever more dreary,

And lower and lower his grey head doth bow;

For the swagman is old and the swagman is weary—

He’s been tramping for over a century now.

He tramps in a worn-out old “side spring” and “blucher,”

His hat is a ruin, his coat is a rag,

And he carries forever, far into the future,

The key of his life in the core of his swag.

There are old-fashioned portraits of girls who are grannies,

There are tresses of dark hair whose owner’s

are grey;

There are faded old letters from Marys and Annies,

And Toms, Dicks, and Harrys, dead many a day.

There are broken-heart secrets and bitter-heart reasons—

They are sewn in a canvas or calico bag,

And wrapped up in oilskin through dark rainy seasons,

And he carries them safe in the core of his swag.

There are letters that should have been burnt in the past time,

For he reads them alone, and a devil it brings;

There were farewells that should have been said for the last time,

For, forever and ever the love for her springs.

But he keeps them all precious, and keeps them in order,

And no matter to man how his footsteps may drag,

There’s a friend who will find, when he crosses the Border,

That the Heart of the Man’s in the Heart of his

swag.

’Tis the song of many husbands, and you all must understand

That you cannot call me coward now that women rule the land;

I have written much for women, where I thought that they were right,

But the men who made bad matches claim a song from me to-night.

Oh, the men who made bad matches are of every tribe and clime,

And, if Adam was the first man, then they date from Adam’s time.

They shall live and they shall suffer, until married life is past,

And the last sad son of Adam stands alone—at peace at last.

Oh, the men who made bad matches, and the Great Misunderstood,

Are through all the world a mighty and a silent brotherhood.

If a wife is discontented, every other woman knows—

But the men who made bad matches keep the cruel secret close.

You may say that you can tell them, by their clothing, if you will,

But a man may seem neglected, and his home be happy still.

You may tell by their assumption of conventional disguise—

But, the men who made bad matches, I can tell them by their eyes!

I have seen them by the camp-fire, where a child’s voice never comes,

I have seen them by the fireside, in their seeming happy homes—

Seen their wives’ false arms go round them, and the kisses that were

lies—

Oh, the men who made bad matches! I can tell them by their eyes.

I have seen them bad in prison—seen them sullen, seen them sad;

I have seen them (in the mad-house)—I have seen them raving mad.

Watched them fight the battle bravely, for the children’s sake alone,

Like a father who has wronged them, and who lives but to atone.

But it’s cruel, oh! it’s cruel, for the husband and the wife,

Who have not one thought in common, and are yoked for weary life.

They must see it through and suffer, for the children they must rear—

Oh, the folk who made bad matches have a heavy cross to bear.

There is not a ray of comfort, in the future’s gloomy sky,

For the children of bad matches will make trouble by-and-bye.

And though second wives be angels, while the first wives were the worst,

No second wife yet wedded makes a man forget the first.

Ah! the men who made bad matches think more often than we know,

Of the girls they should have married, in the glorious long ago,

And there’s many a wife and mother thinks with bitter pain to-day,

Of her giddy, silly girlhood, and the man she sent away.

Life is sad for men and women, but the thoughts are bitter sad

Of the girls we should have married, and the boys we should have had.

But we’ll part now with a handshake, if we cannot with a kiss,

And bad matches may be mended in a better world than this.

There’s many a schoolboy’s bat and ball that are gathering

dust at home,

For he hears a voice in the future call, and he trains for the war to come;

A serious light in his eyes is seen as he comes from the schoolhouse gate;

He keeps his kit and his rifle clean, and he sees that his back is straight.

But straight or crooked, or round, or lame—you may let these words

take root;

As the time draws near for the sterner game, all boys should

learn to shoot,

From the beardless youth to the grim grey-beard, let Australians ne’er

forget,

A lame limb never has interfered with a brave man’s shooting yet.

Over and over and over again, to you and our friends and me,

The warning of danger has sounded plain—like the thud of a gun at sea.

The rich man turns to his wine once more, and the gay to their worldly joys,

The “statesman” laughs at a hint of war—but something

has told the boys.

The schoolboy scouts of the White Man’s Land are out on the hills

today;

They trace the tracks from the sea-beach sand and sea-cliffs grim and grey;

They take the range for a likely shot by every cape and head,

And they spy the lay of each lonely spot where an enemy’s foot might

tread.

In the cooling breeze of the coastal streams, or out where the townships

bake,

They march in fancy, and fight in dreams, and die for Australia’s sake.

They hold the fort till relief arrives, when the landing parties storm,

And they take the pride of their fresh young lives in the set of a uniform.

Where never a loaded shell was hurled, nor a rifle fired to kill,

The schoolboy scouts of the Southern World are choosing their Battery Hill.

They run the tapes on the flats and fells by roads that the guns might sweep,

They are fixing in memory obstacles where the firing lines shall creep.

They read and they study the gunnery—they ask till

the meaning’s plain,

But the craft of the scout is a simple thing to the young Australian brain.

They blaze the track for a forward run, where the scrub is everywhere,

And they mark positions for every gun and every unit there.

They trace the track for a quick retreat—and the track for the other

way round,

And they mark the spot in the summer heat where the water is always found.

They note the chances of cliff and tide, and where they can move, and when,

And every point where a man might hide in the days when they’ll fight

as men.

When silent men with their rifles lie by many a ferny dell;

And turn their heads when a scout goes by, with a cheery growl “All’s

well”;

And scouts shall climb by the fisherman’s ways, and watch for a sign

of ships,

With stern eyes fixed on the threatening haze where the blue horizon dips.

When men shall camp in the dark and damp by the bough-marked battery,

Between the forts and the open ports where the miners watch the sea;

And talk perhaps of their boy-scout days, as they sit in their shelters rude,

While motors race to the distant bays with ammunition and food.

When the city alight shall wait by night for news from a far-out post,

And men ride down from the farming town to patrol the lonely coast—

Till they hear the thud of a distant gun, or the distant rifles crack,

And Australians spring to their arms as one to drive the invaders back.

There’ll be no music or martial noise, save the guns to help you through,

For a plain and a shirt-sleeve job, my boys, is the job that we’ll

have to do.

And many of those who had learned to shoot—and in learning learned

to teach—

To the last three men, and the last galoot, shall die on some lonely beach.

But they’ll waste their breath in no empty boast, and they’ll

prove to the world their worth,

When the shearers rush to the Eastern Coast, and the miners rush to Perth.

And the man who fights in a Queenscliff fort, or up by Keppel Bay,

Will know that his mates at Bunbury are doing their share that day.

There was never a land so great and wide, where the foreign fathers came,

That has bred her children so much alike, with their hearts so much the same.

And sons shall fight by the mangrove creeks that lie on the lone East Coast,

Who never shall know (or not for weeks) if the rest of Australia’s

lost.

And far in the future (I see it well, and born of such days as these),

There lies an Australia invincible, and mistress of all her seas;

With monuments standing on hill and head, where her sons shall point with

pride

To the names of Australia’s bravest dead, carved under the words “Here

died.”

An’ so ’e’s dead in London,

An’ answered to the call,

An’ trotted through the Long Street,

With ’earse an’ plumes an’ all?

We was village boys an’ brothers—

We was warm as we could be,

In the milk-walk an’ the fried fish,

Up in London, ’im an’ me.

We was warm,

We was warm,

As we ’ad always been;

We never ’ad a dry word

Till she come between.

I lived round Windsor Terrace,

An’ ’im across the wye,

An’ when I sailed a emigrant

We never said good-bye!

He wos better than a brother—

Wot you Bushmen call a mate.

(Did he reach the rylwye stytion,

As they told me, just too late!)

We was warm,

We was warm,

As pals was ever seen;

We never ’ad a dry word

Till she come between.

I meant to go back ’ome again,

I meant to write to-night;

I meant to write by every mail,

But I thought ’e oughter write.

An’ now ’e’s left North London—

For a better place, perhaps—

She’s flauntin’ in ’er widder weeds,

With eyes on other chaps.

We was warm,

We was warm,

As we ’ad always been;

We never ’ad a dry word

Till she come between.

Oh! tongues is bad in wimmin,

When wimmin’s tongues is bad!

For they’ll part men an’ brothers

World oceans wide, my lad!

There was seven years between us,

An’ fifteen thousand mile,

An’ now there’s death an’ sorrer

For ever an’ awhile.

We was warm,

We was warm,

As two was ever seen;

We never ’ad a dry word

Till she come between.

She’s milking in the rain and dark,

As did her mother in the past.

The wretched shed of poles and bark,

Rent by the wind, is leaking fast.

She sees the “home-roof” black and low,

Where, balefully, the hut-fire gleams—

And, like her mother, long ago,

She has her dreams; she has her dreams.

The daybreak haunts the dreary scene,

The brooding ridge, the blue-grey bush,

The “yard” where all her years have been,

Is ankle-deep in dung and slush;

She shivers as the hour drags on,

Her threadbare dress of sackcloth seems—

But, like her mother, years agone,

She has her dreams; she has her dreams.

The sullen “breakfast” where they cut

The blackened “junk.” The lowering face,

As though a crime were in the hut,

As though a curse was on the place;

The muttered question and reply,

The tread that shakes the rotting beams,

The nagging mother, thin and dry—

God help the girl! She has her dreams.

Then for “th’ separator” start,

Most wretched hour in all her life,

With “horse” and harness, dress and cart,

No Chinaman would give his “wife”;

Her heart is sick for light and love,

Her face is often fair and sweet,

And her intelligence above

The minds of all she’s like to meet.

She reads, by slush-lamp light, may be,

When she has dragged her dreary round,

And dreams of cities by the sea

(Where butter’s up, so much the pound),

Of different men from those she knows,

Of shining tides and broad, bright streams;

Of theatres and city shows,

And her release! She has her dreams.

Could I gain her a little rest,

A little light, if but for one,

I think that it would be the best

Of any good I may have done.

But, after all, the paths we go

Are not so glorious as they seem,

And—if t’will help her heart to know—

I’ve had my dream. ’Twas but a dream.

“Fall in, my men, fall in.”

—Walt Whitman.

The short hour’s halt is ended,

The red gone from the west,

The broken wheel is mended,

And the dead man laid to rest.

Three days have we retreated

The brave old Curse-and-Grin—

Outnumbered and defeated—

Fall in, my men, fall in.

Poor weary, hungry sinners,

Past caring and past fear,

The camp-fires of the winners

Are gleaming in the rear.

Each day their front advances,

Each day the same old din,

But freedom holds the chances—

Fall in, my men, fall in.

Despair’s cold finger searches

The sky is black ahead,

We leave in barns and churches

Our wounded and our dead.

Through cold and rain and darkness

And mire that clogs like sin,

In failure in its starkness—

Fall in, my men, fall in.

We go and know not whither,

Nor see the tracks we go—

A horseman gaunt shall tell us,

A rain-veiled light shall show.

By wood and swamp and mountain,