a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

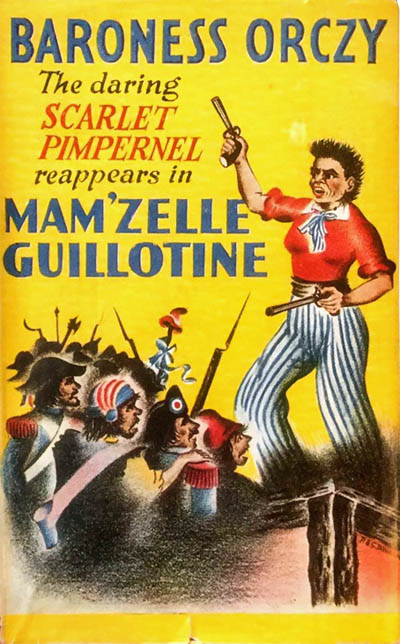

Title: Mam'zelle Guillotine Author: Emmuska Orczy * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 0602621h.html Edition: 1 Language: English Character set encoding: Latin-1(ISO-8859-1)--8 bit Date first posted: July 2006 Date most recently updated: June 2020 This eBook was produced by: Richard Scott and Colin Choat Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg of Australia License which may be viewed online at http://gutenberg.net.au/licence.html

GO TO Project Gutenberg of Australia HOME PAGE

To all those who are fighting in the air,

on the water and on land for our country and

for our homes, I dedicate this romance because

it is to them that we shall owe a happy issue

out of all our troubles and a lasting peace.

EMMUSKA ORCZY.

Monte Carlo,

1939-40.

BOOK ONE

1. 1789 — THE DAWN OF REVOLUTION

2. PARIS IN REVOLT

3. ONE OF THE DERELICTS

BOOK TWO

4. LONDON 1794

5. A SOCIAL EVENT

6. THE PRINCE OF DANDIES

7. A VALOROUS DEED

8. A ROYAL FRIEND

9. THE BITTER LESSON

BOOK THREE

10. A UNIQUE PERSONAGE

11. BAFFLED

12. CHAUVELIN TAKES A HAND

13. THE ENGLISH SPY

14. LE PARC AUX DAIMS

15. WHATEVER HAPPENS

16. A MASTER SLEUTH

17. THUNDER CRASH

18. AT THE COMMISSARIAT OF POLICE

19. THE INTERLOPER

20. THE COURIER

21. AN OUTRAGE

22. NIGHTMARE

BOOK FOUR

23. A MESSAGE

24. THE COSY CORNER

BOOK FIVE

25. THE MAN IN BLACK

26. FORTUNE IN SIGHT

27. AT THE CROSS ROADS

28. THE FIGHT

29. HELL-FOR-LEATHER

30. THE SILENT POOL

31. AN INTERLUDE

"Arms! Arms! Give us arms!"

France to-day is desperate. Her people are starving. Women and children cry for bread; famine, injustice and oppression have made slaves of the men. But the time has come at last when the cry for freedom and for justice has drowned the wails of hungry children. It is Sunday the twelfth of July. Camille Desmoulins the fiery young demagogue is here, standing on a table in the Palais Royal, a pistol in each hand, with a herd of gaunt and hollow-eyed men around him.

"Friends," he demands vehemently, "shall our children die like sheep? Shall we continue to plead for ears that will not hear and appeal to hearts that are made of stone? Shall we labour to feed the welled-filled and see our wives and daughters starve? Frenchmen! The hour has come: the hour of our deliverance. To arms, friends! to arms! Let our oppressors look to themselves. Let them come to grips with us, the oppressed, and see if brutal force can conquer justice."

With burning hearts and quivering lips they listened to him for a while, some in silence, others muttering incoherent words. But soon they took up the echo of the impassioned call: "To arms!" and in a few moments what had been a tentative murmur became a delirious shout: "To arms! To arms!" Throughout the long afternoon, until dusk and nightfall, and thereafter the call to arms like the roar of ocean waves breaking on a rocky shore resounded from one end of Paris to the other. And all night long men in threadbare suits and wooden shoes roamed about the streets, gesticulating, forming groups, talking, arguing, shouting. Shouting always their rallying cry: "To arms!"

By dawn the next day the herd of gaunt, hollowed-eyed men has become a raging multitude. The call for arms has become a vociferous demand: "Give us arms!" Right to-day must be at grips with might. The oppressed shall rise against the oppressor. But the oppressed must have arms wherewith to smite the tyrant, the extortioner, the relentless task-master of the poor. And so they march, these hungry, wan-faced men, at first in their hundreds but soon in their thousands. They march to the Town Hall demanding arms.

"Arms! Arms! Give us arms!"

It is Monday morning but all the shops are shut: neither cobblers, nor weavers, barbers nor venders of miscellaneous goods have taken down their shutters. Labourers and scavengers are idle, for every worker to-day has become a fighter. Alone the bakers and the vinters ply their trade, for fighting men must eat and drink. And the smiths are set to work to forge pikes as fast as they can, and the women up in their attics to sew cockades. Red and blue which are the municipal colours are tacked on to the constitutional white, thus making of the Tricolour the badge of France in revolt.

The rest of Paris continues to roam the streets demanding arms: first at the Hôtel de Ville, the Town Hall where provost and aldermen are forced to admit they have no arms: not in any quantity, only a few antiquated firelocks, which are immediately seized upon. Then they go, those hungry thousands, to the Arsenal, where they only find rubbish and bits of rusty iron which they hurl into the streets, often wounding others who had remained, expectant, outside. Next to the King's warehouse where there are plenty of gewgaws, tapestries, pictures, a gilded sword or two and suits of antiquated armour, also the cannon, silver mounted and coated with grime, which a grateful King of Siam once sent as a present to Louis XIV, but nothing useful, nothing serviceable.

No matter! A Siamese cannon is better than none. It is trundled along the streets of Paris to the Debtors' prison, to the Chatelet, to the House of Correction where prisoners are liberated and made to swell the throng.

News of all this tumult soon wakens the complacent and the luxurious from their slumbers. They tumble out of bed wanting to know what "those brigands" were up to. The "brigands" it seems were in possession of the barriers, had seized the carts which conveyed food into the city for the rich. They were marching through Paris, yelling, and roaring, wearing strange cockades. The tocsin was pealing from every church steeple. Every smith in the town was forging pikes; fifty thousand it was asserted had been forged in twenty-four hours, and still the "brigands" demanded more.

So what were the complacent and the luxurious to do but make haste to depart from this Paris with its strange cockades and its unseemly tumult? There were some quick packings-up and calls for coaches, tumbrils, anything whereon to pile up furniture, silver and provisions and hurry to the nearest barrier. But already Paris in revolt had posted its scrubby hordes at all the gates, with orders to stop every vehicle from going through and to drag every person who attempted to leave the city, willy-nilly to the Town Hall.

And the complacent and the luxurious, driven back into Paris which they wished to quit, desire to know what the commandant of the city, M. le baron Pierre Victor de Besenval is doing about it. They demand to know what is being done for their safety. Well! M. de Besenval has sent courier after courier to Versailles asking for orders, or at least for guidance. But all that he gets in reply to his most urgent messages are a few vague words from His Majesty saying that he has called a Council of his Ministers who will decide what is to be done, and in the meanwhile let M. le baron do his duty as beseems an officer loyal to his King.

Besenval in his turn calls a Council of his Officers. His troops are deserting in their hundreds, taking their arms with them. Two of his Colonels declare that their men will not fight. Later in the afternoon three thousand six hundred Gardes Françaises ordered to march against the insurgents go over to them in a body with their guns and their gunners, their arms and accoutrements. Gardes Françaises no longer, they are re-named Gardes Nationales, and enrolled in the fastgrowing Paris Militia, which is like to number forty—eight thousand soon, and by to-morrow nearer one hundred thousand.

If only it had arms, the Paris Militia would be unconquerable.

And now it is Tuesday, the fourteenth of July, a date destined to remain for all time the most momentous in the annals of France, a date on which century-old institutions shall totter and fall, not only in France, but in the course of time, throughout the civilized world, and archaic systems shall perish that have taken root and gathered power since might became right in the days of cave-dwelling man.

Still no definite orders from Versailles. The Council of Ministers continues to deliberate. Hoary-headed Senators decide to sit in unbroken session, while Commandant Besenval in Paris does his duty as a soldier loyal to his King. But what can Besenval do, even though he be a soldier and loyal to his King? He may be loyal but the men are not. Their Colonels declare that the troops will not fight. Who then can stem that army of National Volunteers, now grown to a hundred and fifty thousand, as they march with their rallying cry "To arms!" and roll like a flood to the Hôtel des Invalides?

"There are arms there. Why had we not thought of that before?"

On they roll, scale the containing wall and demand entrance. The Invalides, old soldiers, veterans of the Seven Years' War stand by; the gates are opened, the Garde Nationale march in, but the veterans still stand by without firing a shot. Their Commandant tries to parley with the insurgents, put they push past him and his bodyguards; they swarm all over the building rummaging through every room and every closet from attic to cellar. And in the cellar the arms are found. Thousands of firelocks soon find their way on the shoulders of the National Guard. What indeed can Commadant Besenval do, even though he be a soldier and loyal to his King?

And now to the Bastille, to that monument of arrogance and power, with its drawbridges, its bastions and eight grim towers, which has reared its massive pile of masonry above the "swinish multitude" for over four hundred years. Tyranny frowning down on Impotence. Power holding the weak in bondage. Here it stands on this fourteenth day of July, bloated with pride and, conscious of its impregnability, it seems to mock that chaotic horde which invades its purlieus, swarms round its ditches and its walls, and with a roaring like that of a tempestuous sea, raises the defiant cry: "Surrender!"

A tumult such as Dante in his visions of hell never dreamed of, rises from one hundred and fifty thousand throats. Floods of humanity come pouring into the Place from the outlying suburbs. Paris in revolt has arms now: One hundred thousand muskets, fifty thousand pikes: one hundred and fifty thousand hungry, frenzied men. No longer do these call out with the fury of despair: "Arms! Give us arms!" Rather do they shout : "We'll not yield while stone remains on stone of that cursed fortress."

And the walls of the Bastille are nine feet thick.

Can they be as much as shaken, even by a hurricane of grapeshot and the roaring of a Siamese cannon? Commandant de Launay laughs the very suggestion to scorn. He has less than a hundred and twenty men to defend what is impregnable. Eighty or so veterans, old soldiers who fought in the Seven Years' War, and not more than thirty young Swiss. He has cannons concealed up on the battlements, and piles of missiles and ammunition. Very few victuals, it is true, but that is no matter. As soon as he opens fire on that undisciplined mob, it will scatter as autumn leaves scatter in the wind. And "No Surrender!" has already been his answer to a deputation which came to him from the Town Hall in the early morning, suggesting parley with the men of the National Guard, the disciplined leaders of this riotous mob.

"No surrender!" he reiterates with emphasis; "rather will I hurl myself down from these battlements into the ditch three feet below, or blow up the fortress sky-high and half Paris along with it."

And to show that he will be as good as his word, he takes up a taper and stands for a time within arm's length of the powder magazine. Only for a time, for poor old de Launay never did do what he said he would. All he did just then was to survey the tumulteous crowd below. They have begun the attack. Paris in revolt opens fire on the "accursed stronghold" with volley after volley of musket-fire from every corner of the Place and from every surrounding window. De Launay thrusts the taper away, and turns to his small garrison of veterans and young Swiss. Will they fire on the mob if he gives the order? He has plied them with drink, but feels doubtful of their temper. Anyway, the volley of musket-fire cannot damage walls that are nine feet thick. "We'll wait and see what happens," thinks Commandant de Launay, but he does not rekindle the taper.

Just then a couple of stalwarts down below start an attack on the outer drawbridge. De Launay knows them both for old soldiers, one is a smith, the other a wheelright, both of them resolute and strong as Hercules. They climb on the roof of the guard-room and with heavy axes strike against the chains of the drawbridge, heedles of the rain of grapeshot around them. They strike and strike again, with such force and such persistence that the chain must presently break, seeing which de Launay turns to his veterans and orders fire. The cannon gives one roar from the battlements, and does mighty damage down below. Paris in revolt has shed its first blood and reaches the acme of its frenzy.

The chains of the outer drawbridge yield and break and down comes the bridge with a terrific clatter. This first tangible sign of victory is greeted with a delirious shout, and an umber of insurgents headed by men of the National Guard swarm over the drawbridge and into the outer court. Here they are met by Thuriot, second in command, with a small bodygaurd. He tries to parley with them. No use of course. Paris now is no longer in revolt. It is in revolution.

The insurgents hustle and bustle Thuriot and his bodyguard out of the way. They surge all over the outer court, up to the ditch and the inner drawbridge. De Launay up on the battlements can only guess what is happening down there. His veterans and young Swiss stand by. Shall they fire, or wait till fired on? Indecision is clearly written on their faces. De Launay picks up a taper again, takes up his position once more within arm's length of the powder magazine. Will he, after all, be as good as his word and along with the impregnable stronghold blow half Paris up sky-high? He might have done it. He said he would rather than surrender, but he doesn't do it. Why not? Who shall say? Was it destiny that stayed his arm? destiny which no doubt aeons ago had decreed the downfall of this monument of autocratic sovereignty on his fourteenth day of July, 1789.

All that de Launay does is to order the veterans to fire once more, and the cannons scatter death and mutilation among the aggressors, whilst all kinds of missiles, pavingstones, old iron, granite blocks are hurled down into the ditch, till it too is littered with dead and dying. The wounded in the Place are carried to safety into adjoining streets, but so much blood has let a veritable Bedlam loose. A cartload of straw is trundled over the outer drawbridge into the court. Fire! Conflagaration! Paris in revolution had not thought before of this way of subduing that "cursed fortress", but now fire! Fire everywhere! The Bastille has not surrendered yet.

Soon the guard-room is set ablaze, and the veterans' mess-room. The fire spreads to one of the inner courts. De Launay still hovers on the battlements, still declares that he will blow up half Paris rather than surrender his fortress. But he doesn't do it, and a hundred feet below the conflagaration is threatening his last entrenchments. The flames lick upwards ready to do the work which old de Launay had sworn that he would do.

Inside the dungeons of the Bastille the prisoners, lifewearied and indifferent, dream that a series of earthquakes are shaking Paris, But what do they care? If these walls nine feet thick should totter and fall and bury them under their ruins, it would only mean for them the happy release of death. For hours has this hellish din been going on. In the inner courtyard the big clock continues to tick on; the seconds, the minutes, the hours go by: five hours, perhaps six, and still the Bastille stands.

Up on the battlements the garrison is getting weary. The veterans have been prone on the ground for over four hours making the cannons roar, but now they are tired. They struggle to their feet and stand sullen, with reversed muskets, whilst an old bearded sergeant picks up a a tattered white flag and waves it in the commandant's face. The Swiss down below do better than that. They open a porthole in the inner drawbridge, and one man thrusts out a hand, grasping a paper. It is seized upon by one of the National Guard. "Terms of Surrender," the Swiss cry as with one voice. The insurgents press forward shouting: "What are they?"

"Immunity for all," is the reply. "Will you accept?"

"On the word of an officer we will." It is an officer of the National Guard who says this. Two days ago he was officer in the Gardes Françaises. His word must be believed.

And so the last drawbridge is lowered and Paris in delirious joy rushes into the citadel crying: "Victory! The Bastille is ours!"

It is best not to remember what followed. The word of an officer, once of the Gardes Françaises, was not kept. Old veterans and young Swiss fell victims to the fury of frenzied conquerors. Paris in revolution, drunk with its triumph, plunged through the labyrinthine fortress, wreaking vengeance for its dead.

The prisoners were dragged out of their dungeons where some had spent a quarter of a century and more in a living death. They were let loose in a world they knew nothing of, a world that had forgotten them. That miserable old de Launay and his escort of officers were dragged to the Town Hall. But they never got there; hustled by a yelling, hooting throng, the officers fell by the wayside and were trampled to death in the gutters. Seeing which de Launay cried pitiably: "O friends, kill me fast." He had his wish, the poor old weakling, and all of him that reached the Town Hall was his head carried aloft on a pike.

To the credit of the Gardes Nationales, once the Royal Regiment of Gardes Françaises, be it said that they marched back to their barracks in perfect order and discipline; it was this same Garde Nationale who plied hoses on the conflagration inside the fortress and averted an explosion which would have wrecked more than a third of the city.

But no one took any notice of the liberated prisoners. A dozen or so of them were let loose in this World-Bedlam, left to roam about the streets, trying all in vain to gather up threads of life long since turned to dust. The fall of the mighty fortress put to light many of its grim secrets, some horrible, others infinitely pathetic, some carved in the stone of a dank dungeon, others scribbled on scraps of mouldy paper.

"If for my consolation" [ was the purport of one of these] "Monseigneur would grant me for the sake of God and the Blessed Trinity, that I could have news of my dear wife: were it only her name on a card to show that she is alive. It were the greatest consolation I could receive, and I would for ever bless the greatness of Monseigneur."

The letter is dated "A la Bastille le 7 Octobre 1752" and signed Quéret-Démery. Thirty-seven years spent in a dark dugeon with no hope of reunion with that dear wife, news of whom would have been a solace to the broken heart. History has no record of one Quéret-Démery who spent close on half a century in the "cursed fortress." What he had done to merit his fate no one will ever know. He was: that is all we know and that he spent a lifetime in agonized longing and ever-shrinking hope.

One can picture him now on this evening of July 14th turned out from that prison which had become his only home, the shelter of his old age, and wandering with mind impaired and memory gone, through the streets of a city he hardly knew again. Wandering with only one fixed aim: to find the old home where he had known youth and happiness, and the love of his dear wife. Dead or Alive? Did he find her? History has no record. Quéret-Démery was just an obscure, forgotten victim of an autocratic rule, sending his humble petition which was never delivered, to "Monseigneur." Monseigneur who? Imagination is lost in conjecture. The profligate Philippe d'Orleans or one of his like? Who can tell?

The attempt to follow the adventures or misadvantures of those thirteen prisoners let loose in the midst of Paris in revolution, would be vain. There were thirteen, it seems. An unlucky number. Again history is silent as to what became to twelve of their number. Only one stands out among the thirteen in subsequent chronicles of the times: a woman. The only woman among the lot. Her name was Gabrielle Damiens. At least that is the name she went by later on, but she never spoke publicly either of her origin or of her parentage. She had forgotten; so she often said. One does forget things when one has spent sixteen years—one's best years—living a life that is so like death. She certainly forgot what she did that night after she had been turned out into the world: she must have wandered through the streets as did the others, trying to find her way to a place somewhere in the city, which had once been her home. But where she slpet then, and for many nights after that she never knew, until the day when she found herself opposite a house in the Boulevard Saint-Germain: a majestic house with an elaborate coronet and coat of arms carved in stone, surmounting the monumental entrance door: and the device also carved in stone: "N'oublie jamais." Seeing which Gabrielle's wanderings came to a sudden halt, and she stood quite still in the gutter opposite the house, staring up at the coronet, the caot of arms and the device. "N'oublie jamais," she murmured. "Jamais!" she reiterated with a curious throaty sound which was neither a cry nor a laugh, but was both in one. "No, Monsieur le Marquis de Saint-Lucque de Tourville," she continued to murmur to herself, "Gabrielle Damiens will see to it that you and your brood never shall forget."

There was a bench opposite the house under the trees of the boulevard and Gabrielle sat down not because she was tired but because she had a good view of the coronet and the device over the front door. Desultory crowds paraded the boulevard laughing and shouting "Victory!" Most of them had been standing for hours in queues outside the bakers' shops, but not everyone had been served with bread. There was not enough to go round, hence the reason why with the cry of "Victory!" there mingled one which sounded like an appeal, and also like a threat:

"Bread! Give us bread!"

Gabrielle watched them unseeing. She too had stood for the past few days in queues, getting what food she could. She had a little money. Where it came from she didn't know. She had a vague recollection of scrubbing floors and washing dishes, so perhaps the money came from that, or a charitable person may have had pity on her: anyway she was neither hungry nor tired, and she was willing to remain here on this bench for an indefinite length of time trying to piece together the fragments of the past from out the confused storehouse of memory.

She saw herself as a child, living almost as a pariah on the charity of relatives who never allowed her to forget her father's crime or his appaling fate. They always spoke of him as "that abominable regicide," which he certainly was not. François Damiens was just a misguided fool, a religious fanatic who saw in the profligate, dissolute monarch, the enemy of France, and struck at him not, he asserted, with a view to murdering his King but just to frighten him and to warn him of the people's growing resentment against his life of immorality. Madness of course. His assertion was obviously true since the weapon which he used was an ordinary pocketknife and did no more than scratch the royal shoulder. But he had struck at the King and royal blood had flown from the scratch, staining the royal shirt. In punishment for this sacrilege, Damiens was hung, drawn and quartered, but to the end, in spite of abominable tortures which he bore stoically, he maintained steadfastly that he had no accomplice and had acted entirely on his own initiative.

François Damiens had left his motherless daughter in the care of a married sister Ursule and her husband Anatole Desèze, a cabinet-maker, who earned a precarious livelihood and begrudged the child every morsel she ate. Gabrielle from earliest childhood had known what hunger meant and the bitter cold of a Paris of winter, often without a fire, always without sufficient clothing. She had relaxation only in sleep and never any kind of childish amusement. The only interests she had in life was to gaze up at an old box fashioned of carved wood, which stood on a shelf in the living-room, high up against the wall, out of her reach. This box for some unknown reason, chiefly because she had never been allowed to touch it, had always fascinated her. It excited her childish curiosity to that extent that on one occasion when her uncle and aunt were out of the house, she managed to drag the table close to the wall, to hoist a chair upon the table, to climb up on the chair and to stretch her little arms out in a vain attempt to reach the tempting box. The attempt was a complete fiasco. The chair slid away from under her on the polished table, and she fell with a clatter and a crash to the floor, bruised all over her body and her head swimming after it had struck against the edge of the table. To make matters worse, she felt so queer and giddy that she had not the strenght at once to put the table and chair back in their accustomed places. Aunt and uncle came back and at once guessed the cause of the catastrophe, with the result that in addition to bruises and an aching head Gabrielle got a sound beating and was threatened with a more severe one still if she ever dared to try and interfere with the mysterious box again. She was ten years old when this disastrous incident occurred. Cowed and fearfull she never made a second attempt to satisfy her curiosity. She drilled herself into avoiding to cast the merest glance up on the shelf. But though she was able to control her eyes, she could not control her mind, and her mind continued to dwell on the mystery of that fatal box.

It was not until she reached the age of sixteen that she lost something of her terror of another beating. She was a strapping girl by then, strong and tall for her age and unusually good-looking inspite of poor food and constant overwork. Her second attempt was entirely succesful. Uncle and aunt were out of the way, table and chair were easily moved and Gabrielle waas now tall enough to reach the shelf and lift down the box. It was locked, but after a brief struggle with the aid of an old kitchen knife the lid fell back and revealed—what? A few old papers tied up in three small bundles. One of these bundles was marked with the name "Saint-Lucque," a name quite unknown to Gabrielle. She turned these papers—they were letters apparently—over and over, conscious of an intense feeling of disappointment. What she had expected to find she didn't know but it certainly wasn't this.

The girl however, was no fool. Soon her wits got to work. They told her that, obviously, if these old letters were of no importance to her, Aunt Ursule would not have kept them all these years out of her reach. As time was getting on and uncle and aunt might be back at any moment, she made haste to replace the box on the shelf, carefully disguising the damamge done by the kitchen knife. Chair and table she put back in their accustomed places and the old letters she tucked away under the folds of her fichu. By this time she had worked herself up into a fever of conjecture, but she had sufficient control over herself to await with apparent calm the moment when she could persue the letters in the privacy of her own room. She had never been allowed to have a candle in the evenings, because there was a street-lamp opposite the window which, as Aunt Ursule said, was quite light enough to go to bed by. Gabrielle hated that street-lamp because as there were no curtains to the window, the glare often prevented her getting to sleep, but on this never-to-be-forgotten night she blessed it. Far into the next morning sitting by the open window, did the daughter of François Damiens read and re-read those old letters by the flickering light of the street-lamp. When the lamp was extinguished she still remained sitting by the window scheming and dreaming until the pale light of dawn enabled her to read and read again. For what did those old letters reveal? They revealed the fact that her unfortunate father who had been sent to his death as a regicide had not been alone in his design against the King. The crime—for so it was called—had been instigated and aided by a body of noble gentlemen who like himself saw in the profligate monarch the true enemy of France. But whilst Damiens bore loyally and in silence the brunt of this conspiracy, whilst he endured torture and went to his death like a hero, those noble gentlemen had remained immune and left their miserable tool to his fate.

All this Gabrielle Damiens learned during those wakeful hours of the night. A great deal of it was of course mere inference; the letters were all addressed to her father apparently by three gentlemen, two of whom with commendable prudence had refrained from appending their signature. But there was one name "Saint-Lucque" which appeared at the foot of some letters more damnatory than most. Before the rising sun had flooded the towers of Notre Dame with gold Gabrielle had committed these to memory.

Yes! Memory was reawakened now, and busy after all these years unravelling the tangled skein of the past. Sitting here on the boulevard opposite the stately mansion with the coat of arms and the device "N'oublie Jamais" carved in stone above its portal, Gabrielle saw herself as she was during the three years following her fateful discovery. Her first task had been to make a copy of the letters in a clean and careful hand, after which there were the days spent in establishing the identity of "Saint-Lucque" and tracing his whereabouts. M. le Marquis de Saint-Lucque turned out to be one of the greatest gentlemen in France, attached to the Court of His Majesty King Louis XV. He lived in a palatial masion on the Boulevard Saint-Germain ans was a widower with one son. His association with François Damiens had seemingly never been found out. Presumably the whole episode was forgotten by now.

Then there came the great day when Gabrielle first called on Monsieur le Marquis. It was not easy for a girl of her class to obtain an interview with so noble a gentlemen, and at once Gabrielle was confronted with a regular barrage of lackeys, all intent apparently on preventing her acces to their master. "No, certainly not," was the final pronouncement of the major-domo, a very great gentleman indeed in this lordly establishment, "you cannot present yourself before Monsieur le Marquis, he will not see you." Gabrielle conscious of her personal charm tried blandishments, but these were of no avail, and undoubtedly she would have failed in her purpose had not Monsieur le Vicomte, son and heir of Monsieur le Marquis, come unexpectedly upon the scene. He was in riding kit. An exceptionally handsome young man, and apparantly more impressionable than the severe major-domo. Here was a lovely girl whose glance was nothing less than a challenge, and she wanted something which was being denied her by a lot of louts. Whatever it was, thought the handsome Vicomte, she must have her wish; preliminary, he added to himself with an appraising look directed at the pretty creature, to his getting what he would want in return for his kind offices. There was an exchange of glances between the two young people and a few moments later Gabrielle was ushered into the presence of Monsieur le Marquis de Saint-Lucque by a humbled and bewildered major-domo. Monsieur le Vicomte had given the order, and there was no disobeying him. "I'll wait for you here," he whispered in the girl's ear, indicating a door on the same landing. She lowered her eyes, put on the airs of a demure country wench, and disappeared within the forbidden precincts.

The first interview with the old aristocrat was distinctly stormy. There was a great deal of shouting at first on his part. A stick was raised. A bell was rung. But Gabrielle held her grounds: very calmly, produced the copy of a damnatory letter, and presently the shouting ceased, the stick was lowered, and the lackey dismissed who came in answer to the bell. The letter doubtless brought up vivid and most unpleasant memories of the past. Presently a bargain was struck, money passed from hand to hand—quite a good deal of money, more than Gabrielle had ever seen in all her life, and the interview ended with a promise on her part to destroy all the original letters. She was to bring them to Monsieur le Marquis the next day and burn them before his eyes. She trotted off with the money safely tucked away in the fold of her fichu. The handsome Vicomte was waiting for her, and she duly paid the tribute which he demanded of her. But she did not call on the old the old Marquis either the next day, or the day after that, or ever again, because a week later Monsieur le Marquis de Saint-Lucque had a paralytic stroke, and thereafter remained bedridden for over four years until the day when he was laid to rest among his ancestors in the family mausoleum in Artois.

In the meantime Gabrielle Damiens's relationship with Vicomte Fernand de Saint-Lucque had become very tender. He was for the time being entirely under the charm of the fascinating blackmailer, unaware of the ugly role she had been playing against his father. He had fitted up what he called a love-nest for her in a rustic chalet in the environs of Versailles and here she lived in the greatest luxury, visited constantly by the Vicomte, who loaded her with money and jewellery to such an extent that she forgot all about her contemplated source of revenue through the medium of the compromising letters.

Everything then was going on very well with the daughter of François Damiens. Her uncle and aunt with the philosophy peculiar to hoc genus omne of their country were only too ready to approve of a situation which contributed largely to their well-being, for Gabrielle, ready to forget the cavalier way in which she had been treated in the past, was not only generous but lavish in her gifts to them. And all went well indeed for nearly three years until the day when Fernand de Saint-Lucque became weary of the tie which bound him to the rather common and exacting beauty and gave her a decisive if somewhat curt congé, together with a goodly sum of money which he considered sufficient as a solace to her wounded vanity. The blow fell so unexpectedly that at first Gabrielle felt absolutely stunned. It came at a moment when, deluded into believing that she had completely enslaved her highborn lover, she saw visions of being herself one day Vicomtesse and subsequently Marquise de Saint-Lucque de Tourville, received at Court, the queen and leader of Paris society.

She certainly did not look upon the Vicomte's partin gift as sufficient solace for her disappointment. It would not do much more than pay her debts to dressmakers, milliners and jewellers. With the prodigality peculiar to her kind she had spent money as freely and easily as she had earned it. She had, of course, some valuable jewellery, but this she would not sell, and the future, as she presently surveyed it, looked anything but cheerful. Soon, however, her sound common sense came to the rescue. She took, as it were, stock of her resources, and in the process remembered the letters on which she had counted three years ago as the foundation of her fortunes. She turned her back without a pang on the rustic chalet, no longer a love-nest now, and returned to her uncle and aunt, in whom she now felt compelled to confide the secret of her disappointment in the present and of her hopes of the future.

She made a fresh attempt to see the old Marquis. Then only did she learn of his sickness and the hopeless state of mind and body in which he now was. But this did not daunt Gabrielle Damiens. Her scheme of blackmail could no longer be succesfully directed against the father, but there was the son, the once enamoured Vicomte, her adoring slave, now nothing but an arrogant aristocrat, treating the humble little bourgeoise as if she were dirt and dismissing her out of his life with nothing but a miserable pittance. Well! He should pay for it, pay so heavily that not only his fortune but also his life would be wrecked in the process. Moreover, she, the daughter of that same François Damiens, who had been dubbed the regicide and died a horrible death, would see her ambition fulfilled and herself paid court to and the hem of germent kissed by obsequious courtiers, when she was Madame la Marquise de Saint-Lucque de Tourville.

She started on her campaign without delay. A humble request for an interview with M. le Vicomte was at first curtly refused, but when it was renewed with certain veiled threats it was conceded. Armed with the copies of the damnatory letters Gabrielle demanded money first and then marriage. Yes! no less a thing than marriage to the hier of one of the greatest names in France, failing which the letters would be sent to the Comte de Meaurevaisre, Chief of the Secret Police of His Majesty the King. Well! When Fernand de Saint-Lucque had dismissed her, Gabrielle, with a curt word of farewell, he had dealt her a blow which had completely knocked her over. But it was her turn now to retaliate. He tried to carry off the affair in his usual high-handed manner. He began with sarcasm, went with bravado, and ended with threats. Gabrielle stood as she had done three years ago before the old Marquis. Already she felt conscious of victory, because she had seen the look almost like a death-mask which had come over Fernand de Saint-Lucque's face when he took in the contents of this the first of the fateful letters. When she held it out to him he had waved her hand aside with disdain. She placed it on the table, and waited until natural curiosity impelled him to pick it up. He did it with a contemptuous shrug, held it as if it were filth.

But the look so like a death-mask soon spread over his face. He did his best to disguise it, but Gabrielle had seen it and felt convinced that victory was already in sight. She left, not taking any money away with her, not exacting any promise at the moment save that her victim—he was her victim already—would see her once more. He had commanded her to bring the letters: "Not the copies remember! The originals!" which the Vicomte declared with all his old arrogance did not exist save in the imagination of a cinderwench.

For days and weeks after that first interview did Gabrielle Damines keep the Vicomte de Saint-Lucque on tednerhooks without going near him. The old Marquis was still alive, slowly sinking, with one foot in the grave, and Gabrielle hugged herself with thoughts of the hier of that great name writhing under the threat of disgrace to the head of the house, disgrace followed by confiscation of all his goods, exile from court and country, his name for ever branded with the stigma of regicide: disgrace which would redound on his heir and on all his family, and migh even be the stepping stone to an ignominious death.

When Gabrielle felt that Fernand had suffered long enough she sent him a harsh command for another interview. Devoured with anxiety, he was only too ready to accede. She came this time in a mood as arrogant as his own, exacting writtenpromise of marriage: the date of the wedding to be fixed here and now. She did not bring the original letters with her. They would, she said curtly, be handed over to him when she, Gabrielle Damines, was incontestably Vicomtesse de Saint-Lucque de Tourville.

Fernand at his wits' end did not know what to do. He tried pretence: a softened manner as if he was prepared to yield. Quite gently and persuasively he explained to her that whatever his ultimate decision might be—and he gave her to understand that it certainly would be favourable—he was compelled at the moment to ask for a few days delay. He had been, he said, paying court to a lady, at His Majesty's express wish, had in fact become officially engaged, and all he needed was a little time for the final breaking off of his obligations. In the meanwhile he was ready, he said, to give her a written promise of marriage duly signed, the wedding to take place within the next three months.

As usual Gabrielle's common sense warned her of a possible trap. The Vicomte had made a very sudden volte-face and had become extraordinarily suave and engaging. He even went to length of assuring her that he never ceased to love her, and that it was only at the King's command that he had become engaged to the lady in question. The breaking off of that engagement, he declared in conclusion, would cause him no heartache. A little doubtful, inclined to mistrust this plausible dissembler, Gabrielle remained impervious to his blandishments, even when she suddenly found herself in his arms, under the once potent spell of his kisses. No longer potent now. She smiled back into his glowing eyes, accepted the written promise of marriage and endured his kisses while keeping her wits about her. When she finally freed herself from his arms she merely assured him that the compromising letters would be returned to him when she had become his lawful wife.

She trotted home that afternoon happy and triumphant with the written promise of marriage duly signed "Fernand de Saint-Lucque de Tourville" safely tucked away in the folds of her fichu. Aunt Ursule and Uncle Desèze congratulated her on her triumph, and the three of them sat up half the night making plans for a golden future. Aunt and uncle would have a farm with cows and horses and pigs, a beautiful garden and plenty of money to give themselves every luxury.

"You need never be afraid of the future," Gabrielle declared proudly. "I'll never be such a fool as to give up the original letters. Even when I am Marquise de Saint-Lucque I will always keep that hold over my husband."

There ensued four days of perfect bliss, unmarred by doubts or fears. They were destined to be the last moments of happiness the blackmailer was ever to know in life. Saint-Lucque, whose engagement to Mademoiselle de Nesle had not only been approved of but actually desired by the King, was nearly crazy with terror at the awful sword of Damocles hanging over his head. Not knowing where to turn or what to do he finally made up his mind to confide the whole of the miserable story to his future mother-in-law, the person most likely to be both discreet abd helpful. Madame de Nesle was just then in high favour with the King, whose daughter Mademoiselle was reputed to be, and she was just as anxious as was His Majesty to see the girl married to the bearer of a great name who would secure for her the entreé to the most exclusive circles of aristocratic France. One could not, Madame declared emphatically, allow a dirty blackmailer to come athwart the royal plans, and at once she suggested a lettre de cachet, one of those abominable sealed orders which consigned any person accused of an offence against the King to lifelong imprisonment, without the formality of a trail. She was confident that she could obtain anything she desired from her adoring Louis, and anyhow incarceration in the Bastille was the only way of silencing that audacious malefactor.

And Madame was as good as her word. Four days later Gabrielle Damiens saw herself cast into a cell in the Bastille. All her possessions were seized by the men who came to arrest her. Pinioned between two of them she watched the other two turning out her table drawers, and pocket everything they found there, including the precious letters, the promise of marriage and the pieces of jewellery which she had saved from the débâcle of the love-nest. Neither tears, nor protest, nor blandishments were of any avail. Her demands for a trail were met with stolid silence, her questions were not answered. She had become a mere chattel cast into a dungeon, there to remain till she was carried out, feet first, to be thrown into an unknown grave. She never knew what had become of her aunt and uncle, nor did she ever hear the name of Saint-Lucque mentioned again while she spent her best years in a living death.

Gabrielle Damiens was nineteen years old when this catastrophe occurred. Sixteen years had gone by since then.

"Tell me more about that young woman, Blakeney. She interests me."

It was the Prince of Wales who spoke. He was honouring Sir Percy and Lady Blakeney with his presence at dinner in their beautiful home in Richmond. The dinner was over; the ladies had retired leaving the men to enjoy their port and their gossip. It had been a small and intimate dinner-party and after the ladies had gone only half a dozen men were left sitting round the table. In addition to the host and the royal guest, there were present on this occasion four of the more prominent members of that heroic organization known as the League of the Scarlet Pimpernel: Lord Anthony Dewhurst, my Lord Hastings and Sir Philip Glynde, also Sir Andrew Ffoulkes, his chief's right hand and loyal lieutenant, newly wed to Mademoiselle Suzanne de Tournay, one of the fortunate ones whom the League had succeeded in rescuing from the horrors of revolutionary France.

Without waiting for a reply to his command, His Royal Highness went on meditatively:

"I suppose Paris is like hell just now."

"With the lid off, sir," was Blakeney's caustic comment.

"And not only Paris," Sir Andrew added; "Nantes under that fiendish Carrier runs it close."

"As for the province of Artois—" mused my Lord Hastings.

"That is where that interesting young woman takes a hand in the devilish work, isn't that it, Blakeney?" the Prince interposed. "You were about to tell us something more about her. I confess there is something that thrills one in that story in spite of oneself. The idea of a woman—"

His Highness broke off and resumed after a moment or two:

"Is she young and good-looking?"

"Young? No sir," Blakeney answered. "Nearer forty than thirty, I should say."

"And not good-looking?"

"She must have been at one time. But sixteen years in the Bastille has modified all that."

"Sixteen years!" His Highness ejaculated. "What in the world had she done?"

"It has been a little difficult to get to the bottom of her story. But I was interested. So were we all, weren't we, Ffoulkes? As you say, sir, there is something thrilling-horrible really-in the idea of a woman performing the revolting task of a public executioner. For that is Gabrielle Damiens's calling at the moment."

"Damiens?" His Highness mused; "the name sounds vaguely familiar."

"Perhaps you will remember sir, that some twenty-five years ago a kind of religious maniac named François Damiens created a sensation by slashing the late King with a penknife, without doing real harm, of course; but for this so-called crime he was condemned to death, hung, drawn and quartered. He maintained to the end, even under torture, that he had acted entirely on his own and that he never had any accomplice."

"Yes! I remember the story now. And this female executioner is his daughter?"

"His only child. She was only a baby at the time. As far as we have been able to unravel the tangled skein of this extraordinary tragi-comedy, Damiens bequeathed her a packet of old letters which involved the old Marquis de Saint-Lucque-the father of the present man-in that ridiculous conspiracy. Armed with these the girl-she was only sixteen at the time-started a campaign of blackmail, first against the old Marquis and, when he became bedridden, against his son, who, I understand, was deeply in love with her at one time."

"What a complication! But go on, man. Your story is as interesting as a novel by that French fellow Voltaire. Well!" His Highness continued, "and what happened to the blackmailer?"

"The usual thing sir. Saint-Lucque got tired of his liaison, broke it off, became engaged to Mademoiselle de Nesle..."

"Good old Louis's daughter, what?"

"Supposed to be," Blakeney replied curtly.

"I remember Madame de Nesle," His Highness mused. A beautiful woman! She even made the du Barry jealous. I was in Paris at the time. And her daughter married Saint-Lucque, of course...I remember!"

"Then you can guess the rest of the story, sir. Madame de Nesle wanted her daughter's marriage to take place. She had great influence over the King, and obtained from him one of those damnable lettres de cachet which did effectually silence the blackmailer by keeping her locked up in the Bastille without trial and without a chance of appeal. There she would have ended her days had not the revolutionaries captured the Bastille and liberated the prisoners."

"Most interesting! Most interesting! And how did the blackmailer become the executioner?"

"By easy stages, sir."

"What was she like when she came out, one wonders."

"Like a raging tigress."

"Naturally."

"Vowing before anyone who cared to listen that she would make Saint-Lucque and all his brood pay eye for eye and tooth for tooth."

"That was inevitable, of course," the Prince mused, "and not difficult to accomplish these days. I suppose," he went on, "that this Gabrielle Damiens has already got herself mixed up with the worst of the revolutionary rabble."

"She certainly has. She began by joining in the crowd of ten thousand women who marched to Versailles demanding food. She seized a drum from one of the guard-rooms in the suburb where she lived, and paraded the streets beating the Generale and shouting: 'Bread! we must have bread!...' and 'Come, mothers, with your starving children... .' and so on."

"You weren't there, were you, Blakeney?"

"I was, sir. Tony, Ffoulkes and I were the guests of the King that day at Versailles. We saw it all. It was the queerest crowd, wasn't it, Tony?"

"It certainly was," my Lord Tony agreed lightly; "fat fishwives from the Halles, chambermaids shouldering their brooms, pale-faced milliners and apple-cheeked country wenches. All sorts and conditions."

"And this Damiens woman was among them?"

"She led them, sir," Blakeney replied, "with her drum. The whole thing was really pathetic. Food in Paris was very scarce and very dear and there were many cases of actual starvation. The trouble was, too, that the Queen had chosen to give a huge banquet the day before to the officers of the army of Flanders who came over to take the place of certain disloyal regiments. Three hundred and fifty guests sat down to a Gargantuan feast, ate and drank till the small hours of the morning. It was most injudicious to say the least."

"Wretched woman!" the Prince put in with a sigh; "she always seemed to do the wrong thing even in those days."

"And did so to the end, poor woman," one of the others observed.

"Was that the banquet you told me about, Blakeney, where you first met your adorable wife?"

"It was, sir," Blakeney replied, while a wonderfully soft look came into his lazy blue eyes, as it always did when Marguerite's name was as much as mentioned. It was only a flash, however. The next moment he added casually:

"And where I first saw Mam'zelle Guillotine."

"Such a funny name," His Highness remarked. "As a rule they speak of Madame Guillotine over there."

"Gabrielle deserves the name, sir, odious as it sounds. I have been told that she has guillotined over a hundred men and women and even a number of children with her own hands."

Then as they all remained silent, unable to pass any remark on this horrible statement, Sir Percy went on:

"After the march on Versailles she became more and more prominent in the revolutionary movement. Marat became her close friend and gave her all the publicity she wanted in his paper L'ami du Peuple. I know for a fact that she actually took a hand in the wholesale massacre of prisoners the September before last. Robespierre thinks all the world of her oratory, and she has spoken more than once at the Club des Jacobins and at the Cordeliers. I listened on several occasions to the harangues which she likes to deliver in the Palais Royal Gardens, standing on a table with a pistol in each hand as Camille Desmoulins used to do. They were the most inflammatory speeches I ever heard. And clever, too. The sixteen years she spent in the Bastille did not dull her wits seemingly. Finally," Blakeney concluded, "Robespierre got her appointed last year, at her own request, public executioner in his native province of Artois, and there she has been active ever since."

There was silence round the festive board after that. They were all men here who had seen much of the seamy side of life. Even His Highness had had experiences which do not usually come in the way of royal personages, and he was the only non-member of the League of the Scarlet Pimpernel who knew the identity of its heroic chief. His eyes now rested with an expression of ill-concealed affection and admiration on that chief, whom he honoured with his especial friendship.

He raised his glass of port and sipped it thoughtfully before he spoke again, then he said with an attempt at gaiety:

"I know what you are thinking at this moment, Blakeney."

"Yes, your Highness?" Sir Percy retorted.

"That Mam'zelle Guillotine will soon be...what shall we say?...lying in the arms of the Scarlet Pimpernel."

This sally made everybody laugh, and conversation presently drifted into other channels.

There are many records extant to-day of the wonderful rout offered to the élite of French and English society in London by Her Grace the Duchesse de Roncevaux in her sumptuous house in St. James's Square. The date I believe was somewhere in January, 1794. The decorations, the flowers, the music, the banquet-supper surpassed in magnificence, it is asserted by chroniclers of the time, anything that had ever been seen in the ultra-fashionable world.

The Duchesse, as everybody knows, was English by birth, daughter of Reuben Meyer, the banker, and immensely rich. His Grace the Duc de Roncevaux, first cousin to the royal house of Bourbon, married her not only for her wealth but principally because he was genuinely in love with her. His name and popularity at court secured for his wife a brilliant position in Paris society during the declining years of the monarchy, whilst his charming personality and always deferential love-making brought her a full measure of domestic happiness. He left her an inconsolable widow after five years of married bliss. The revolutionary storm was by then already gathering over France. The English-born Duchesse thought it best to return to her own country, before the cloud-burst which appeared more and more threatening every day. She chose London as her principal home, and here with the aid of her wealth and a heart overflowing with the milk of human kindness she did her best to gather round her those more fortunate French families who had somehow contrived to escape from the murderous clutches of the revolutionary government of France. Thus a delightful set of charming cultured people could always be met with in the Duchesse de Roncevaux's luxurious salons. Here one rubbed shoulders with some of the members of the old French aristocracy now dispossessed of most if not all their wealth, but bringing into the somewhat free-and-easy tone of eighteenth-century London something of their perfect manners, their old-world courtesy and that atmosphere of high-breeding and distinction handed down to them by generations of courtiers. The Comte de Tournay with Madame his wife and their son the young Vicomte were often to be seen at these social gatherings. Mademoiselle de Tournay had recently married Sir Andrew Ffoulkes, the handsome young leader of fashion, who was credited with being a member of the heroic League of the Scarlet Pimpernel. There was Félicien Lézenne, who had been chairman of the Club des Fils du Royaume, his young wife and Monsieur de Lucines, his father-in-law, who were actually known to have been saved from the guillotine by that mysterious and elusive person the Scarlet Pimpernel himself.

There were others, of course, for the list of refugees from revolutionary France waxed longer day by day and all found a welcome in the Duchesse de Roncevaux's hospitable mansion; and not only did they find a welcome but also a measure of gaiety! for the daughter of Reuben Meyer the Jewish banker had understanding as well as social ambition. Her aim was to make her salon the most attractive one in town, and what society could be more attractive than that of those French aristocrats, most of whom had palpitating stories to tell of past horrors, of dangers of death, and, above all, of those almost phenomenal rescues of condemned innocents sometimes under the very shadow of the guillotine, effected by that heroic organization known as the League of the Scarlet Pimpernel and its lion-hearted chief.

To hear one of those deeds of unparalleled courage recounted by one of those who owed their lives to that intriguing personality was voted unanimously to be far more exciting than a melodrama at Drury Lane, and the Duchesse de Roncevaux could always be relied on to provide her guests with one of those soul-stirring narrations which caused every velvet cheek to flush with enthusiasm and every bright eye to glow with hero-worship. There were other entertainments too to be enjoyed in the sumptuous mansion in St. James's Square, there were operas, ballets, comedies, concerts: young musicians often made their first formal bow before a discriminating company which often included the Prince of Wales himself and the élite of English society, and more than one disciple of the late Mr. Garrick first tasted the sweets of success in the Duchesse's salon. But none of these entertainments had the power to excite interest as did the relation of one of those hair-raising exploits of the mysterious Scarlet Pimpernel, told with fervour and a charming French accent by whoever happened to be the honoured guest of the evening.

On this occasion it was the abbé Prud'hon, lately come from France in the company of Monsieur le Marquis de Saint-Lucque and the young Vicomte. The arrival of Monsieur de Saint-Lucque had been a real event in the chronicle of London society. He was known to have been saved from death by the hero of the hour: in fact, he and the abbé had proclaimed this openly, and everybody—the men as well as the ladies—had been on tenterhooks to hear the true version of their amazing rescue. All sorts of rumours had been afloat, as they always were whenever a French family came to join the colony of recent émigrés who had found refuge in hospitable England. Everyone was agog to know how they had been smuggled out of France, for that was what it amounted to. Men, women and children, the old, the infirm, whenever innocent seemed literally to have been snatched from under the very noses of the revolutionary guard, and this led to all sorts of tales, medieval in their superstitious extravagance, of direct interference from the clouds or of a supernatural being, of unearthly appearance and abnormal strength who scattered revolutionary soldiers before him as easily as he would a swarm of flies.

There was a first-class sensation in fashionable circles when Madame la Duchesse de Roncevaux issued invitations for one of her popular routs. The invitation promised a concert by the London String Band, a playlet to be performed by His Majesty's mummers, and a supper prepared by Monsieur Haon formerly cook-in-chief to Madame de Pompadour. But all these attractions paled in interest before the one brief announcement: "Guest of Honour: M. l'Abbé Prud'hon." Everyone in town knew by now that M. l'Abbé Prud'hon was tutor to the young Vicomte de Saint-Lucque and had been summarily arrested along with him and M. le Marquis by the revolutionary government under the usual futile pretext of having plotted against the safety of the Republic.

The salons of Madame la Duchesse de Roncevaux were thronged on this occasion as they had never been before, and there was such a chattering up and down the monumental staircase as the guests filed up to greet their hostess, as in an aviary of love-birds.

"My dear, isn't it too wonderful?"

"I declare I am so excited, I don't know if I am standing on my head or on my heels."

"I know I shall scream if that London String Band goes on too long."

"I call it cruel to put them on before we have heard M. l'Abbé."

"Hush! you mustn't say that. The dear Duchesse had them only in order to bring our blood to boiling point."

"Mine has been over boiling point all day, and I am on the verge of spontaneous combustion."

By ten o'clock all the guests had arrived, and the hostess, wearied after standing for over an hour at the head of the staircase receiving the company, had retired to the rose-coloured boudoir where His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, Sir Percy and Lady Blakeney, Sir Andrew and Lady Ffoulkes and a small number of the more privileged guests were discussing the coming event somewhat more soberly than did the gaily plumaged birds in the adjoining ball-room. M. l'Abbé was there too, a pathetic figure in his well-worn soutane: his cheeks, once round and full, were pale and wan now, showing signs of the many privations, the lack of food and warmth, which he had suffered recently. He looked ill and very weary. It was only his eyes, tired-looking and red-rimmed though they were, that retained within their depths a merry twinkle which every now and then came to the fore, when his inward glance came to rest on a memory less cruel than most: that merry twinkle was the expression of a keen sense of humour which no amount of sorrow and suffering had the power wholly to eradicate.

At the moment he certainly seemed to have thrown off some of his lassitude; finding himself the centre of interest in a sympathetic crowd, all anxious to make him forget what he had suffered, and to make him feel at home in this land of freedom and of orderly government, his whole being seemed to expand in response. A warm glow came into his eyes and the smiles so freely bestowed on him by the ladies found their reflection round his pale, drooping lips. Everyone was charming to him. The Prince of Wales was most gracious, and his hostess lavish in delicate attentions. He had had an excellent dinner, and a couple of glasses of fine old Burgundy had put heart into him.

"Ah, Monsieur l'Abbé," sighed lovely Lady Lauriston, "you will tell us, won't you, the true, unvarnished facts about your wonderful escape."

"Of course I will, dear lady," the old priest replied; "nothing could make me happier than to let the whole world hear, if it were possible, the story of one of the most valorous deeds ever accomplished on this earth. I have seen men and women, especially recently, show amazing pluck and endurance under the terrible circumstances which alas obtain in my poor country these days, but never did I witness anything like the courage and resourcefulness displayed by that noble gentleman who rescued us from certain death at risk of his life."

The abbé had spoken so earnestly and in a voice quivering with such depth of emotion, that instinctively the chatter around him died down, and for a few moments there was silence in the pretty rose-coloured boudoir, whilst the old priest and several of the ladies surreptitiously wiped away a tear. Everyone felt thrilled, emotional; even the men responded readily to that feeling of pride in the display of courage and endurance, those virtues which make such a strong appeal to the finest of their sex.

It was the hostess who first broke the silence. She asked:

"And you do not know who your rescuer was, M. l'Abbé?"

"Alas, no, Madame la Duchesse. Monsieur de Saint-Lucque, the Vicomte and I were locked up inside the coach which was conveying us to Paris for trial and, of course, execution. It was very dark. To my sorrow I saw nothing, no one. And that is a sorrow I shall take with me to my grave. To touch the hand of the most gallant man on earth would be an infinite joy to me. And I know that Monsieur le Marquis thinks as I do over that."

"How is Monsieur le Marquis, by the way?" His Royal Highness enquired.

The abbé shook his head and drew a deep sigh.

"Sadly, I am afraid. He is heart-broken with anxiety about his wife and the other two children: and he keeps on reproaching himself for being safe and free while they are still in danger."

"Don't let him break his heart over that, M. l'Abbé. Didn't you tell us the other day that the Scarlet Pimpernel had pledged you his word to bring Madame de Saint-Lucque and her two little girls safely to England?"

It was Lady Blakeney who spoke. She was sitting on the sofa near the old priest and while she said those comforting words she put her hand on his arm. She was the most beautiful woman there, easily the queen among this bevy of loveliness. The abbé turned to her and met those wonderful luminous eyes of hers so full of confidence and encouragement. He raised her hand to his old lips.

"Yes," he said; "we did get that marvellous pledge, Monsieur de Saint-Lucque and I. How it came to us is another of the many miracles that occurred during those awful times after we were arrested and incarcerated in the local gaol. There was a funny old fellow, dirty and bedraggled, whom we caught sight of one day through the grated window of our prison-cell. He was stumping up and down the corridor outside singing the Marseillaise very much out of tune. Two days later we saw him again, and this time as he stumped along he recited in a cracked voice that awful blasphemous doggerel: 'Ça ira!' It was then that the miracle occurred, for after he had gone by we saw a crumpled wad of paper on the floor, just beneath the window."

Here the abbé's narration was suddenly broken into by a shrill little cry of distress.

"Sir Percy, I entreat, do hold my hand. I vow I shall swoon if you do not."

The cry broke the tension which was keeping the small company in the boudoir hanging on the words of the old priest. All eyes were turned to the dainty lady who had uttered the pitiful appeal. The Lady Blanche Crewkerne had edged closer and closer to the sofa where sat the abbé; her eyes were glowing, her lips quivered; she was in a regular state of flurry. As soon as she had attracted all the attention she coveted to her engaging personality she raised a perfumed handkerchief to her tip-tilted nose, fluttered her eyelids, closed her eyes and finally tottered backwards as if in very truth she was on the point of losing consciousness. From all around there came an exclamation of concern until a pair of masculine arms was stretched out to receive the swooning beauty, whereupon concern turned to laughter, loud and prolonged laughter while Lady Blanche opened her eyes, thinking to find herself reclining against the magnificent waistcoat of the Prince of Dandies. They encountered the timid glance of old Sir Martin Cheverill, who felt very much embarrassed in the chivalrous role of supporter to a lady in distress thus unexpectedly thrust upon him. Nor did the lady make any effort to conceal her mortification. Already she had recovered her senses, as well as her poise. With nervy movements she plied her fan vigorously and remarked somewhat tartly:

"Methought Sir Percy Blakeney was standing somewhere near."

There was more laughter after this, and old Lady Portarles who never missed an opportunity of putting in a spiteful word where the younger ladies were concerned, interposed mockingly:

"Sir Percy, my dear Blanche? Why, he has been fast asleep this last half-hour."

And picking up her ample train she swept across the room to where a rose-coloured portière was drawn across the archway of a recess. Lady Portarles drew the curtain aside with a dramatic gesture and there of a truth across a satin-covered sofa, his head reclining against a cushion, fast asleep, lay the Prince of Dandies, Sir Percy Blakeney, Bart. An exclamation of horror, amounting to a groan, went round the room. Such disgraceful behaviour surpassed any that that privileged person had ever been guilty of. Had it been anyone else...

The groan, the exclamation of horror, had quickly roused the delinquent from his slumbers. He struggled to his feet and looking round on the indignant faces turned on him he had the good grace to look thoroughly embarrassed.

"Ladies, a thousand pardons," he stammered shame-facedly. "His Royal Highness deigned to keep me at hazard the whole afternoon and..."

But it was no use appealing to His Highness for protection against the irate ladies. He was sitting back in his chair roaring with laughter.

"Blakeney," he said between his guffaws, "you'll be the death of me one day."

And after a time he added: "It is to Monsieur l'Abbé Prud'hon that you owe an abject apology."

"Monsieur l'Abbé..." Sir Percy began in tones of the deepest humility, "to do wrong is human. I have done wrong, I confess. To forgive is divine. Will you exercise your privilege and pronounce absolution on the repentant sinner?"

His manner was so engaging, his diction so suave, and he really did seem so completely ashamed of himself that the kind old priest who had a keen sense of humour was quite ready to forgive the offence.

"On one condition, Sir Percy," he said lightly.

"I am at your mercy, M. l'Abbé."

"That you listen to me—without once going to sleep, mind you—while I narrate to Madame la Duchesse's guests the full story of how Monsieur de Saint-Lucque and his son as well as my own insignificant self were spirited away out of the very jaws of death, and at the risk of his own precious life, by that greatest of living heroes the Scarlet Pimpernel."

"I am at your mercy, M. l'Abbé ," Sir Percy reiterated ruefully.

"And now I pray you, Sir Percy," the Lady Blanche resumed, and gave a playful tap with her fan on Sir Percy's sleeve, "to hold my hand. I am still on the point of swooning, you know," she added archly.

She held out her pretty hand to Blakeney, who raised it to his lips, then turning to the Prince of Wales he pleaded: "Will your Royal Highness pronounce this painful incident closed and command Monsieur l'Abbé to give us the story of what he is pleased to call a miracle."

"Monsieur l'Abbé..." His Highness responded, turning to the old priest, "since you have been gracious enough to forgive..."

"I will continue, c'est entendu," Monsieur l'Abbé readily agreed. And once more the ladies crowded round him the better to listen to a tale that had their beau ideal for its hero. Nor were the men backward in their desire to hear of the prowess of a man whose identity remained as incomprehensible as were the methods which he employed for getting in touch with those persecuted innocents whom he had pledged himself to save.

"And what was written on that scrap of paper, M. l'Abbé?" His Highness asked.

"Only a few words, your Highness," the priest replied. "It said: We who are working for your safety do pledge you our word of honour that Madame de Saint-Lucque and her two children will land safely in England before long," and in the corner there was a drawing of a small flower roughly tinted in red chalk."

"The Scarlet Pimpernel!" The three magic words coming from a score of exquisitely rouged lips had the sound of a deep-drawn sigh. It was followed by a tense silence while the abbé mopped his streaming forehead.

"Your pardon, ladies," he murmured. "I always feel overcome with emotion when I think of those horrible and amazing days."

Thus was the incident closed. The hostess rose somewhat in a flurry.

"In my excitement to hear you, M. l'Abbé," she said, "I am forgetting my guests. Will your Royal Highness deign to excuse me?"

"I'll follow you in a moment, dear lady. Your guests I am sure are dying with impatience. And," he added, turning with a smile to the other ladies, "all the best seats will soon be occupied."

It seemed like a hint, which from royal lips was akin to a command. Lady Lauriston, Lady Portarles and the other ladies followed in the wake of Madame la Duchesse. Only at a sign from His Royal Highness did a privileged few remain in the boudoir: they were Sir Percy and Lady Blakeney, Sir Andrew Ffoulkes and his young wife, Lord Anthony Dewhurst, Monsieur l'Abbé Prud'hon and two or three others.

The Prince turned to the old priest and asked:

"And M. de Saint-Lucque you say, reverend, sir, could find no trace of the whereabouts of his wife and daughters?"

"None, monseigneur," the abbé replied. "When M. de Saint-Lucque did me the honour of seeking shelter under my roof with Monsieur le Vicomte, he entrusted his wife and daughters to the care of a worthy couple named Guidal, who had a small farm a league or so from Rocroi. They had both been in the service of old M. le Marquis, who had loaded them with kindness, and I for one could have sworn that they were loyalty itself. The night before our summary arrest—we already knew that we were under suspicion—the woman Guidal came to my presbytery. She was in tears. I questioned her and through her sobs she contrived to convey to me the terrible news that her husband fearing for his own arrest had talked of denouncing Madame la Marquise to the police; that she herself had entreated and protested in the name of humanity and past loyalty to the family, but terror of the guillotine had got a grip over him and he wouldn't listen. The woman went on to say that Madame la Marquise had unfortunately overheard the discussion and in the early dawn before she and her husband were awake had left the farm with her two little girls going she knew not whither. "Your Highness may well imagine," the old man went on, "how completely heart-broken Monsieur de Saint-Lucque was and has been ever since. At times since then I have even feared for his reason. Had it not been for his son he would I feel sure have done away with himself, but never for one moment would I allow M. le Vicomte to be away from his father. This was not difficult as the guard put over us during our captivity and in the coach that was taking us to Paris kept the three of us forcibly together. The first ray of light that came to us through this abysmal horror," the abbé now concluded, mastering the emotion which had seized him while he told his pitiable story, "were the few lines written on the scrap of paper which a dirty and be-draggled scavenger threw in to us through the grated window of our prison-cell: 'We who are working for your safety do pledge you our word that Madame de Saint-Lucque and her two children will land in England before long.'"

"And you may rest assured, M. l'Abbé, that that pledged word will never be broken."

It was Marguerite Blakeney who said this, breaking the tense silence which had reigned in the gay little boudoir when the old priest had concluded his narrative. She put her hand on his, giving it a comforting pressure and the old man raised it to his lips.

"God bless you!" he murmured. "God bless England and you all who belong to this great country." He rose to his feet and added fervently: "And, above all, God bless the selfless hero of whom you are so justly proud and to whom so many of us owe life and happiness: your mysterious Scarlet Pimpernel."

"God bless him!" they all murmured in unison.

Over in the ball-room the London String Band had finished playing the last item on their programme and the final chords of the Magic Flute followed by a round of applause came floating in on the perfumed air of the rose-coloured boudoir.

"Your Royal Highness," came in meek accents from Sir Percy Blakeney, "will you deign to remember that I am forbidden to go to sleep until Monsieur l'Abbé has told us a lot more about that shadowy Scarlet Pimpernel, and frankly I am dead sick of the demmed fellow already."

The Prince had already regained his habitual insouciance.

"Nor do we wish," he said, and gave the signal for every one to rise and follow him, "to miss another moment of M. le Abbé's interesting talk. But I'll warrant, my friend," he added, with a chuckle, "that you won't get to sleep till after you have completely atoned for your abominable conduct."

He shook an admonishing finger at Sir Percy Blakeney, the darling of society, the pattern of the perfect gentleman, caught in flagrante delicto of bad manners, and finally led the way into the adjoining ball-room. It was crowded with an ultra-fashionable throng. The elite of English society was present in full force as well as a goodly contingent of French émigrés. Lady Lockroy was there with her two pretty daughters. The old Earl of Mainbron had brought his charming young wife, and the Countess of Lauriston, acknowledged to be next to Lady Blakeney the best-dressed woman in town, had donned one of the new-fashioned dresses of clinging material and high waist said to be the latest mode in Vienna. And many others, of course. When His Highness entered the ball-room and the ladies swept their ceremonial courtesy to him down to the ground, there was such a rustling of silks and satins as if a swarm of bees had suddenly been let loose. His Highness had Lady Blakeney on his arm, and immediately behind him came Sir Percy with young Lady Ffoulkes. The Prince was in the best of humours.

"Ladies! Ladies!" he said gaily; "you have missed such a scandal as London has not witnessed for many a day. Has not our charming hostess told you?"