a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

The Prisoner in the Opal:

A.E.W. Mason:

eBook No.: 0200971h.html

Language: English

Date first posted: Jan 2013

Most recent update: Dec 2021

This eBook was produced by Colin Choat, Matthias Kaether and Roy Glashan

by

A.E.W. Mason

"The Prisoner In The Opal,"

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd., London, 1928

"The Prisoner In The Opal,"

Crime Club Edition, Doubleday, New York, 1928

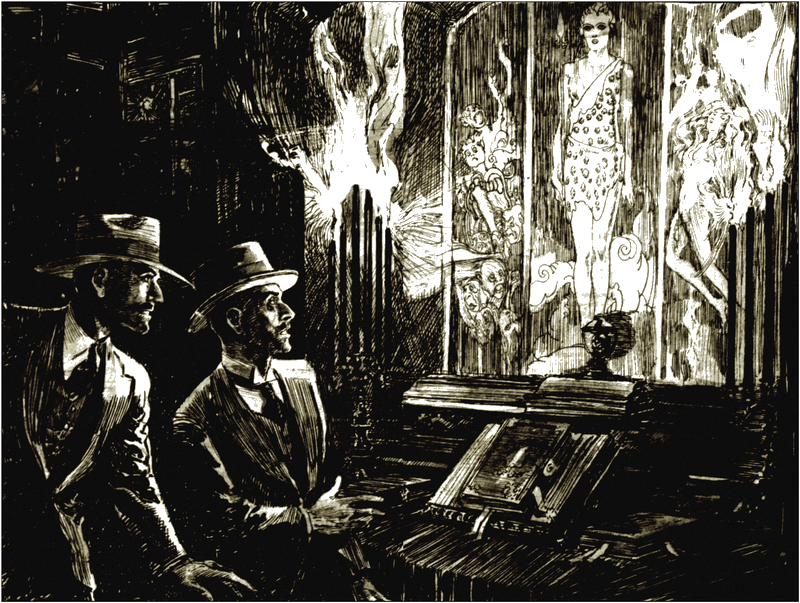

McClure's, May 1928, with first part of "The Prisoner In The Opal"

Headpiece from McClure's, May 1928

WHEN Mr. Julius Ricardo spoke of a gentleman —and the word was perhaps a thought too frequent upon his tongue—he meant a man who added to other fastidious qualities a sound knowledge of red wine. He could not eliminate that item from his definition. No! A gentleman must have the great vintage years and the seven growths tabled in their order upon his mind as legibly as Calais was tabled on the heart of the Tudor Queen. He must be able to explain by a glance at the soil why a vineyard upon this side of the road produces a more desirable beverage than the vineyard fifty yards away upon the other. He must be able to distinguish at a first sip the virility of a Château Latour from the feminine fragrance of a Château Lafite. And even then he must reckon that he had only learnt a Child's First Steps. He could not consider himself properly equipped until he was competent to challenge upon any particular occasion the justice of the accepted classification. Even a tradesman might contend that a Mouton Rothschild was unfairly graded amongst the second growths. But the being Mr. Ricardo had in mind must be qualified to go much farther than that. It is probable indeed that if Mr. Ricardo were suddenly called upon to define a gentleman briefly, he would answer: "A gentleman is one who has a palate delicate enough and a social position sufficiently assured to justify him in declaring that a bottle of a good bourgeois growth may possibly transcend a bottle of the first cru."

Now Julius Ricardo was a man of iron conscience. The obligations which he imposed upon others in his thoughts, he imposed in his life upon himself. He made it a point of honour to keep thoroughly up to date in the matter of red wine; and he mapped out his summers to that end. Thus, on the Saturday of Goodwood week he travelled by the train to Aix-les-Bains. There he found his handsome motor-car which had preceded him, and there for five or six weeks he took his absurd cure. Absurd, for the only malady from which he suffered was that he was a bad shot. He shot so deplorably that his presence on a grouse-moor invariably provoked ridicule and sometimes, if his host wanted a big bag, contumely and indignation. Aix-les-Bains was consequently the only place for him during the month of August. His cure ended, he journeyed with a leisurely magnificence across France to Bordeaux, planning his arrival at that town for the end of the second week of September. At Bordeaux he refitted and reposed; and after a few days, on the eve of the vintage, he set out on a tour through the hospitable country of the Gironde; moving by short stages from château to château; enjoying a good deal of fresh air and agreeable company; drinking a good deal of quite unobtainable claret from the private cuvées of his hosts; and reaching early in October the pleasant town of Arcachon with a feeling that he had been superintending the viniculture of France. This was the curriculum. But as he was once dipped amongst agitations and excitements at Aix, so on another occasion he was shaken to the foundations of his being during his pilgrimage through the vineyards. He was even spurred by the touch of the macabre in these events to a rare poetic flight.

"The affair gave me quite a new vision of the world," he would declare complacently. "I saw it as a vast opal inside which I stood. An opal luminously opaque, so that I was dimly aware of another world outside mine, terrible and alarming to the prisoner in the opal. It was what is called a fire opal, for every now and then a streak of crimson, bright as the flash of a rifle on a dark night, shot through the twilight which enclosed me. And all the while I felt that the ground underneath my feet was dangerously brittle just as an opal is brittle—" and so on and so on. Mr. Ricardo, indeed, embroidered and developed and expounded his image of an opal to a degree of tediousness which even in him was phenomenal. However, the crime did make a stir far beyond the placid country in which it ran its course. The records of the trial do stand wherein may be read the doings of Mr. Ricardo and his friend Hanaud, the big French detective, and all the other people who skated and slipped and stumbled and shivered in as black a business as Hanaud could remember.

For Mr. Ricardo, the trouble began in a London drawing-room during the week which preceded Goodwood races. The men had just come up from the dining-room and were standing, as is their custom, uncomfortably clustered near to the door. Mr. Ricardo looked up and caught a distinct smile of invitation from the prettiest girl in the room. She was seated deliberately apart from her companions on a couch made for two, and no less deliberately she smiled. Mr. Ricardo could not believe his eyes. He certainly knew the young lady. She was a girl from California with a name as pretty as herself, Joyce Whipple, and from time to time in London, and in Paris, and in Venice, he had enjoyed the good fortune of being freshly introduced to her. But what in the world had he, a mere person who would never become a personage, the amateur of a hundred arts and the practitioner of none of them, a retired tea-broker from Mincing Lane—what qualities had he that could interest so radiant a creature during the hours before a dinner-party could decently disperse? For radiant she was from her sleek small head to her slender brocaded shoes. Her hair was dark brown in colour, parted in the middle and curved in the neatest of ripples over her ears. Her face was pale without being sallow; her forehead low, and she had that space between her large grey eyes which means real beauty; her nose was just a trifle tip-tilted, her upper lip short, and her mouth if anything on the large side, her lips healthily red. She had a small firm chin, and she was dressed in an iridescent frock shot with pale colours which blended and separated with every movement which she made. She was so trim and spruce that the first impression which she provoked was not so much that she was beautiful as that she was exquisitely finished down to the last unnoticeable detail. She had apparently been sent straight to the house in a bandbox and set on her feet by the most careful hands. Mr. Ricardo could not believe that smile was meant for him. He had merely intercepted it, and was beginning to look round for the fortunate youth for whom it was intended, when the young lady's face changed. A look of indignation swept over it first, that he should be so reluctant to approach her. The indignation was succeeded by an eager appeal as his hostess bore down upon him. Mr. Ricardo hesitated no longer. He slipped quickly across the room, and Joyce Whipple at once made room for him on the couch by her side.

"We must talk very earnestly," she said. "Otherwise you will be snatched away from me, Mr. Ricardo." She bent forward urgently and with the air of one speaking of life and death babbled about the first thing which came into her head.

"One of your great ladies, shrewd as your great ladies are, told me, when I first came to England, that if I ever wanted particularly to speak to a man, my moment would come when he and the other men joined the ladies. She said that there were always a few seconds when they stood rather self-conscious and embarrassed in a silly group, wondering to whom they'd be welcome and to whom they would not. If at such a time a girl directed the least tiny beckoning glance to one of them, he would be gratefully at her feet for the rest of the evening. But the plan almost missed fire tonight, although I gave you a ploughman's grin."

"I thought that there must be some Adonis just behind my shoulder," Mr. Ricardo replied; and the hostess, who had not quite abandoned her chase, hesitated.

Mr. Ricardo had a certain value of an evening. He had no wish to run away and dance at night clubs. So he could be depended upon to play bridge until the party broke up. And though, alas, he did occasionally say with a giggle, "Now, where shall we go for honey?" or perpetrate some such devastating jest, he played a sound, unenterprising game. But it was evident to his hostess that tonight he was winged for higher flights. She turned away, and Joyce Whipple drew a little breath of relief.

"You know a friend of mine, Diana Tasborough," she said.

"She is kind enough to nod to me across a ballroom when she remembers who I am," Mr. Ricardo answered modestly.

Joyce Whipple betrayed a little impatience.

"But you are going to stay with her, of course, at the Château Suvlac when you go wine-hunting in the autumn."

Mr. Ricardo winced. He could not have imagined a phrase so unsuitable to his dignified pilgrimage through the Médoc and the Gironde.

"No," he replied rather coldly. "I shall be staying in the neighbourhood, but with the Vicomte Cassandre de Mirandol."

He is not to be blamed if he rolled the name rather grandly upon his tongue. It belonged undoubtedly to the first cru among names, and had a delicate fine flavour of the Crusades. However, Mr. Ricardo was honest and, after only the slightest possible struggle with his vanity, he added: "But I have not yet made the acquaintance of the Vicomte, Miss Whipple. There is illness in the house where I was to have stayed and I have been passed on in the hospitable way people have there."

"I see." Joyce Whipple was clearly disappointed and almost aggrieved. "I made certain, since I have met you at Diana's house, that you would be breaking your journey at Suvlac."

Mr. Ricardo shook his head. "But I shall be no more than a mile away, and if I can do anything for you I certainly will. As a matter of fact, I haven't seen either Miss Tasborough or her aunt for at least six months."

"No. They have been all the summer at Biarritz," said Joyce.

"I have never stayed at the Château Suvlac," Mr. Ricardo continued naively, "though I should have liked to. For from the outside it is charming. A rose-pink house of one story in the shape of a capital E, with two little round towers in the main building and a great stone-paved terrace at the back overlooking the river Gironde—"

But Joyce Whipple was not in the least interested in his description of the rose-pink country house, and Mr. Ricardo broke off. Joyce Whipple was leaning forward, her elbow on her knee and her chin propped in the cup of her hand, and a look of anxiety upon her face.

"Yes—after all," said Mr. Ricardo on quite a new note of interest, "it is a little odd."

"What's odd?" asked Joyce Whipple, turning her face to him.

"That the Tasboroughs should have spent the whole summer at Biarritz. For if anywhere was anybody's spiritual home, London was Miss Diana's."

Rich by the inheritance of the Suvlac vineyards, and chaperoned by a submissive aunt, Diana Tasborough was the heart and pivot of one of those self-contained sets into which young London is sub-divided. A set of people, youthfully middle-aged for the most part, who had already reached distinction or were on the way to it. Diana, it is true, fished a river in Scotland and hunted in the Midlands, but London was her home and the headquarters of the busy company of her friends.

"She has been ill?" Mr. Ricardo suggested.

"No. She writes to me and there's never a word about any illness. All the same, I am troubled. Diana was terribly kind to me when I first came over to England and knew nobody at all. I should hate anything to happen to her—anything, I mean —evil."

Joyce pronounced the word slowly, not because she had any doubt that it was the right word to use, but so that Mr. Ricardo might not make light of it. Mr. Ricardo, indeed, was startled. He looked about the room. The banks of roses, the brightness of the illumination, the smartly dressed people, were not in accord with so significant a word.

"Do you really think that something evil is happening to her?" he asked. He was thrilled, even a little pleasurably thrilled.

"I am sure," Joyce Whipple declared.

"Why are you sure?"

"Diana's letters to me," said Joyce, and turning towards Mr. Ricardo, she fixed her big grey eyes upon his face. "I tell you frankly that I can't find in any one of them a single sentence, even a single phrase, which taken by itself is alarming. I know that, for I have analysed them carefully over and over again. And I want you to believe that I am not imaginative, or psychic —no, not the least bit in the world. And yet I never read a letter from Diana without going through the most horrible experience. I seem to see"—and she broke off to correct herself—"no, there's no seeming about it. I do see underneath the black-ink letters, swinging backwards and forwards somehow between the written words and the white paper they are written on, a chain of faces, grotesque, unfinished and dreadful. And they are always changing. Sometimes they—how shall I describe it?—flatten out into featureless, pink round discs with eyes which are alive. Sometimes they quiver up again into distorted human outlines. But they are never complete. If they were, I feel sure that they would be utterly malignant. And they are never still. They float backwards and forwards, like" —and she clasped her hands over her eyes for a moment and shivered so that a big fire-opal on a plain gold bracelet flamed against her wrist—"like the faces of drowned people who have been swinging to and fro with the tides for months."

Joyce Whipple was no longer concerned with the effect of her narrative upon Mr. Ricardo. She had almost forgotten his presence. Her eyes, too, though they moved here and there from a bridge table to a group of people talking, saw really nothing of the room. She was formulating her strange experience for the hundredth time to herself, in the hope that somewhere, in her story, by some chance word, she would be led to its explanation.

Joyce Whipple was no longer concerned with Mr. Ricardo.

"And I am afraid," she continued in a low but—very distinct voice. "I am afraid that sooner or later I shall see all those cruel dead faces complete and alive, the faces of living people."

"Living people who are threatening Diana Tasborough," said Mr. Ricardo gently, so that he might not break the train of Joyce Whipple's thoughts.

"More than threatening her," said Joyce. "Harming her— yes, now already doing her harm which already it may be too late to repair. No doubt it sounds mediaeval and—and— ridiculous, but I have a horrible dread that utterly evil spirits —the elementals are fighting in the darkness for her soul, that she herself isn't aware of it, but that by some dispensation the truth is allowed to break through to me."

Joyce threw up her hands suddenly in a little gesture of despair. "But, you see," she cried, "the moment I begin to piece my fears together into a pattern of words, they just shred away into little wisps too elusive to mean anything at all to anybody except myself."

"No," Mr. Ricardo objected. It was his proud thought that he was a citizen of the world with a very open mind. There were thousands of strange occurrences, of intuitions, for instance, subsequently justified, which science could not explain and only the stupid could deride. "I would never say that the shell of the world mightn't crack for any one of us and let some streak of light come through, misleading perhaps, true perhaps—a will-o'-the-wisp, or a sunbeam."

It seemed to him that to no one might this hint of a revelation be more naturally vouchsafed than to this girl with the delicate, sensitive face and the grey eyes to which her long silken eyelashes, with their upward curve, lent so noticeable a look of mystery.

"After all," he continued. "Who knows enough to deny that there may come messages and warnings?"

"Yes." Joyce Whipple caught at the word. "Repeated warnings. For if I put the letters away, and after a time take them out and read them again, I have just the same dreadful vision. I see just the same heave and surge of water with the unfinished faces washing to and fro."

Mr. Ricardo began to rebuild his recollections of Diana Tasborough, fitting one in here, and another in there, until he had a fairly clear picture of the girl. She was tall, with hair of the palest gold, very pretty but a trifle affected in strange company. She had a way of fluttering her eyelids and pursing her mouth as she spoke, as if each word that she dropped was a pearl of rarest price. There was another quality too.

"She was always a little aloof," he said.

Joyce took him up at once. "Yes, but sedately aloof. Not as if she was living some mysterious secret life of her own all the time. I know what you mean. But it really only signified that she was just a little bit more her own mistress than were most of her friends. She—what shall I say?—she romped without romping. And don't you see that precisely that extra hold she had upon herself increases my fears? She is the last person for whose soul and body the powers of evil should be fighting in the shadows."

A movement amongst the guests diverted Mr. Ricardo's thoughts. The evening was growing late. One of the bridge tables had already broken up. Mr. Ricardo was a practical man.

"But what in the world can I do about it?" he asked.

"You will be in the neighbourhood of the Château Suvlac in September?"

"Yes."

"And Diana always has a party for the vintage."

Mr. Ricardo smiled. Diana's parties were famous in the Gironde. For ten nights or so the windows of that old rose-pink château of the sixteenth century blazed out upon the darkness until dawn. The broad stone terrace was gay with groups of young people dancing, and the music of their dances and even their laughter were heard far out upon the river, by the sailors in their gabares waiting upon the turn of the tide. The hour at which the guests retired precluded early rising, except perhaps upon the first day. But somewhere about twelve o'clock the next day they might be seen picking grapes in attractive costumes and looking rather like the chorus of a musical comedy whose action took place in a vineyard of France.

"Yes, she certainly has a party for the vintage," he said.

"Well then, you see what I want you terribly to do," said Joyce, turning again towards him and plying him—oh, most unfairly!—with all the glamour of a lovely girl's confidences and appealing eyes. "If you will, of course. It's a little prayer, of course. I have no claim. But I know how kind you are—" Did she see the poor man flinch, that she must pile flattery upon prayer and woo him with the most wistful, plaintive voice? "I want you to spend as much time as you can at the Château Suvlac. You will be welcome, of course"—she dismissed the ridiculous idea that he could ever be unwelcome with a flicker of her fingers. "You could watch. You can find out what is happening to Diana—whether there is anybody really dangerous to her amongst her associates and then—"

"And then I shall write to you, of course," Mr. Ricardo said, as cheerfully as these arduous duties so confidently laid upon him enabled him to do. He was surprised, however, to discover that letters to Joyce Whipple upon the subject were not to be included in his duties.

"No," she answered with a trifle of hesitation. "Of course I should love to hear from you—naturally I should, and not only about Diana—but I can't quite tell where I shall be towards the end of September. No, what I want you to do is, once you have found out what's wrong, to jump in and put a stop to it."

Mr. Ricardo sat back in his chair with a very worried expression on his face. For all his finical ways and methodical habits he was at heart a romantic. To play the god for five minutes so that a few young people stumbling in the shadows might walk with sure feet in a serene light—he knew no higher pleasure than this. But romance must nevertheless be reasonable, even if it took the shape of so engaging a young lady as Joyce Whipple. What she was proposing was work for heroes, not for middle-aged gentlemen who had retired from Mincing Lane. And as he ran over in his mind the names of more suitable champions, a tremendous fact leaped into his mind.

"But surely," he stammered in his eagerness. "Diana Tasborough is engaged. Yes, I am sure of it. To a fine young fellow too. He was in the Foreign Office and went out of it and into the City, because he didn't want to be the poor husband of a rich wife." Mr. Ricardo's memory was working at forced draught, now that he saw the way of escape opening in front of him, a passage between the Scylla of refusal and the Charybdis of failure. "Bryce Carter! That's his name! That is his business. You must describe your experiences to him, Miss Whipple, and—"

But Miss Whipple cut him short, very curtly, whilst the blood mounted curiously over her throat and painted her cheeks pink. "Bryce Carter has crashed."

Mr. Ricardo was shocked and disappointed. "In an aeroplane? I hadn't heard of it. I am so sorry. Crashed? Dear me!"

"I mean," said Joyce patiently, "that Diana has broken off the engagement. That's another reason why I think something ought to be done about it. She was very much in love with him and it all went in a week or two—she gave him no reason. So he's barred out, isn't he? I feel that I can't really stand aside —not, of course, that I have anything to do with it—" Joyce Whipple was rapidly becoming incoherent, whilst the colour now flamed in her cheeks. "So unless you can help—"

But Mr. Ricardo felt that his position was more delicate than ever. He was not at all attracted by his companion's confusion; and since the hoped—for avenue of escape was closed for him, he cast desperately about for another; and found it.

"I have got it," he said, shaking a finger at her triumphantly.

"What have you got?" Joyce asked warily. "The only possible solution of the problem." He was most emphatic about it. There was to be no discussion at all. His arrangement must just go through.

"You are the one person indicated to put the trouble right," he declared. "You are Diana's friend. You know all her other friends. You can propose yourself for her party at the Château Suvlac. You have influence with her. If there is anyone— dangerous—wasn't that the word you used?—no one is so likely as you to discover who it is—yes."

He looked her over. There was a vividness about her, a suggestion of courage and independence which went very well with the straight, slim figure and the delicate tidiness of her appearance. She seemed purposeful. This was the age of young women. By all means let one of them, radiant as Joyce Whipple, blow the trumpet and have the intense satisfaction of seeing the walls of this new Jericho collapse. He himself would look on without one pang of envy from the house of the nobleman with the resonant name, the Vicomte Cassandre de Mirandol.

"You! Of course, you!" he exclaimed admiringly.

Suddenly the positions were reversed. So great a discomfort was visible in Joyce Whipple's movements and in her face that Mr. Ricardo was astonished. He had chanced upon a quite unexpected flaw in her armoury. It was she who now must walk delicately.

"No doubt," she admitted with a great deal of embarrassment. "Yes, and I have been asked to Suvlac... and I shall go if —I can. But I don't think that I can." She broke out passionately: "I wish with all my heart that I could! But I shall probably be out of reach. In America. That's why I said that it was of no use to write to me, and why I wanted to unload the whole problem upon you. You see"—she looked at Mr. Ricardo shyly and quickly looked away again—"you see, Cinderellas must be off the premises by midnight," and with a hurried glance at the clock, "and it's almost midnight now."

She rose quickly as she spoke, and with a smile and a pleasant word, she joined a small cluster of young people by the flower-banked grate. These had obviously been waiting for her, for they wished their hostess good night and immediately went away.

Mr. Ricardo certainly had the satisfaction of knowing that he had not committed himself to Joyce Whipple's purposes. But the satisfaction was not very real. The odd story which she had told him was just the sort of story which appealed to him; for he had a curious passion for the bizarre. And even then he was less intrigued by the narrative than by the narrator. He tried indeed to fix his mind upon the problem of Diana Tasborough. But the problem of Joyce Whipple popped up instead. Almost before he realized his untimely behaviour, he had got her dressed up like some wilful beauty of the Second Empire. There she was, sitting in front of him, as he drove back to his house in Grosvenor Square, her white shoulders rising entrancingly out of one of those round, escalloped gowns which kept up heaven knows how, and spread in voluminous folds about her feet. Yet even so, with her thus attired before his eyes, as it were, he began to doubt, to wonder whether he was not growing a trifle old-fashioned and prejudiced. For after all, could Joyce Whipple, with her straight, slender limbs, her wrists and hands and feet and ankles as fragile seemingly as glass, have looked more lovely in any age than she had looked in the short shimmering frock which she had worn that night? Her voice certainly supported the argument that her proper period was the Second Empire. For instead of the brisk high notes to which he was accustomed, it was soft and low and melodious and had a curiously wistful little drawl which it needed great strength of character to resist. There were, however, other points which affected him less pleasantly. Why had his two suggestions thrown her into so manifest a confusion? What had she to do with Bryce Carter that she must blush so furiously over the rupture of his engagement to Diana Tasborough? And—

"Bless my soul," he cried, in the solitude of his limousine, "what was all this talk of Cinderella?" The glass-slipper portion of that pretty legend was all very appropriate and suitable. But the rest of it? Miss Joyce Whipple had come over from the United States with a sister a year or two older than herself, and almost as pretty—yes. The sister had married recently and had married well—yes. But before that event, for two years wherever the fun of the fair was to be found, there also were the Whipple girls. Deauville and Dinard had known them and the moors of Scotland, from which Mr. Ricardo was excluded. He himself had seen Joyce Whipple flaming on the sands of the Lido in satin pyjamas of burnt orange. For Mr. Ricardo was one of those seemly people who from time to time looked in at the Lido in order that they might preach sermons about its vulgarities with a sound and thorough knowledge. Joyce Whipple had certainly looked rather dazzling in her burnt orange pyjamas—but at that moment Mr. Ricardo's car stopped at his front door and put an end to his reflections. Perhaps it was just as well.

A MONTH later chance, or destiny, if so large a word can be used in connection with Mr. Ricardo, conspired with Joyce Whipple. Mr. Ricardo was drinking his morning coffee at the reasonable hour of ten in his fine sitting-room on the first floor of the Hotel Majestic, with his unopened letters in a neat pile at his elbow, when the writing upon the envelope of the top one caught and held his eye. It was known to him, but he did not recognize it. He was in a vacuous mood. The sun was pouring in through the open windows. It was more pleasant to sit and idly speculate who was his correspondent than to tear open the envelope and find out. But years ago he had received a lesson in this very room at Aix-les-Bains on the subject of unopened letters, and, remembering it, he opened the letter and turned at once to the signature. He was a little more than interested to read the name of Diana Tasborough. He read the whole letter eagerly now. The Vicomte Cassandre de Mirandol did not, after all, propose to bring his servants out of Bordeaux and open up his château for the vintage. He would be amongst his vineyards himself for ten days or so, with no more attendance than his valet and the housekeeper at the château. Under these circumstances it would be more comfortable for Mr. Ricardo if he put up at the Château Suvlac.

There will only be a small party, and you will complete it, Diana wrote very politely. You will meet Monsieur de Mirandol at dinner here, and I shall look forward to your arrival on the list of September.

Mr. Ricardo had perused every word of this letter before he realized that it had provoked in him no uncanny sensations whatever; and when he did realize that disconcerting fact, he was not a little mortified. But there it was. Not one dead drowned incomplete malignant face heaved on a tide between the ink and the paper. No, not one! It is true that the ink was purple instead of black; and for a moment or two Mr. Ricardo sought an unworthy consolation in that difference. But his natural honesty made him reject it. The colour of the ink could be only the most superficial circumstance.

"Not one dead drowned face, not a suggestion of evil, not a pang of alarm," Mr. Ricardo announced to himself as he nicked the letter away with considerable indignation. "And yet I am no less sensitive than other people."

It might be, of course, that if he suspended his mind more thoroughly he in his turn might receive the thrill of a message from the world beyond. It was certainly worth an experiment.

"My best plan," he argued, "will be to shut my eyes tight and think of nothing whatever for five minutes. Then I will read the letter again."

He shut his eyes accordingly with the greatest determination. He was modest. He did not ask for very much. If he saw something pink and round like a jelly-fish when he opened his eyes, he would be content and his pride quite restored. But he must give himself time. He allowed what he took to be a space of five minutes. Then he opened his eyes, pounced upon the letter— and received one of the most terrible shocks of his life. On the table, by the letter, rested a hand, and beyond the hand an arm. Mr. Ricardo with startled eyes followed the line of the arm upwards, and then uttering a sharp cry like the bark of a dog he slid his chair backwards.

Mr. Ricardo with startled eyes followed the line of the arm upwards.

He blinked, as well he might do. For sitting over against him, on the other side of the table, sprung silently; heaven knew whence, sat a brigand—no less —a burly brigand of the most repulsive and menacing appearance. A black cloak was wrapped about his shoulders in the Spanish style, a big, unkempt, bristling beard grew like a thicket upon his face, and crushed upon his brows he wore a high-crowned, broad-brimmed soft felt hat. He sat amazingly still and gazed at Mr. Ricardo with lowering eyes as though he were watching some obnoxious black beetle.

Mr. Ricardo was frightened out of his wits. He sprang up with his heart racing in his breast. He found somewhere a shrill piercing voice with which to speak.

"How dare you? What are you doing in my room, sir? Go out before I have you flung into prison! Who are you?"

Upon that the brigand, with a movement swift as the shutter of a camera, lifted up his beard, which hung by two bent wires upon his ears, until it projected from his forehead, leaving the lower part of his face exposed.

"I am Hanaudski. The King of the Chekas," said the alarming person, and with another swift movement he nicked the beard back into its proper position.

Mr. Ricardo sank down into his chair, exhausted by this second shock which trod so quickly upon the heels of the first.

"Really!" was all that he had the breath or the wit to say. "Really!"

Thus did Monsieur Hanaud, the big inspector of the Sûreté Générale, with the blue chin of a comedian, renew after a year's interval his incongruous friendship with Mr. Ricardo. It had begun a lustrum ago in Aix-les-Bains, and since Hanaud took his holidays at a modest hotel of this pleasant spa, each August reaffirmed it. Mr. Ricardo was always aware that he must pay for this friendship. For now he was irritated to the limits of endurance by Hanaud's reticence when anything serious was on foot; and now he was urged in all solemnity to expound his views, which were then rent to pieces, and ridiculed and jumped upon; and again he found himself as now the victim of a sort of schoolboy impishness which Hanaud seemed to mistake for humour, and was in any event totally out of place in a serious person. In return, Mr. Ricardo was allowed to know the inner terrible truth of a good many strange cases which remained uncomfortable mysteries to the general public. But there were limits to the price he was prepared to pay, and this morning Monsieur Hanaud had stepped beyond them.

"This is too much," said Mr. Ricardo, as soon as he had recovered his speech. "You come into my room upon tiptoe and unannounced at a time when I am giving myself up to thought-concentration. You catch me—I admit it—in a ridiculous position, which is not half so ridiculous as your own. You are, after all, Monsieur Hanaud, a man of middle age—" And he broke off helplessly.

There was no use in making reproaches. Hanaud was not listening. He was utterly pleased with himself. He was absorbed in that pleasure. He kept lifting up his beard with that incredibly swift movement of his hand, saying to himself with startling violence, "Hanaudski, the Cheka King," and then nicking down the great valance of matted hair into its original position.

"Hanaudski, the King of the Chekas! Hanaudski from Moscow! Hanaudski, the Terror of the Steppes!"

"And how long do you propose to go on with this grotesque behaviour?" Mr. Ricardo asked. "I should really be ashamed, even if I were able to excuse myself on the ground of Gallic levity."

That phrase restored to Mr. Ricardo a good deal of his self-esteem. Even Hanaud recognized the shrewdness of the blow.

"Aha! You catch me one, my friend. A stinger. My Gallic levity. Yes, it is a phrase which punishes. But see my defence! How often have you said to me, and, oh, how much more often have you said to yourself: 'That poor man Hanaud! He will never be a good detective, because he doesn't wear false beards. He doesn't know the rules and he won't learn them.' So all through the winter I grow sad. Then with the summer I shake myself together. I say: 'I must have my dear friend proud of me. I will do something. I will show him the detective of his dreams.'"

"And instead, you showed me a cut-throat," Mr. Ricardo replied coldly.

Hanaud disconsolately removed his trappings and folded them neatly in a pile. Then he cocked his head at his companion. "You are angry with me?"

Mr. Ricardo did not demean himself to reply to so needless a question. He returned to his letter; and for a little while the temperature of the room even on that morning of sunlight was low. Hanaud, however, was unabashed. He smoked black cigarette after black cigarette, taking them from a bright blue paper packet, with now and then a whimsical smile at his ruffled friend. And in the end Mr. Ricardo's curiosity got the better of his indignation.

"Here is a letter," he said, and he took it across the room to Hanaud. "You shall tell me if you find anything odd about it."

Hanaud read the address of an hotel in Biarritz, the signature and the letter itself. He turned it over and looked up at Mr. Ricardo.

"You draw my leg, eh?" he said; and proud, as he always was, of his mastery of English idioms, he repeated the phrase. "Yes, you draw my leg."

"I don't draw your leg," Mr. Ricardo answered with a touch of his recent testiness. "A most unusual expression."

Hanaud took the sheet of paper to the window and held it up to the light. He felt it between his fingers, and he saw his companion's eyes brighten eagerly. There could be no doubt that Mr. Ricardo was very much in earnest about this simple invitation.

"No," he said at length. "I read nothing but that you are bidden to the Château Suvlac for the vintage by a lady. I congratulate you, for the Bordeaux of the Château Suvlac is amongst the most delicate of the second growths."

"That, of course, I knew," said Mr. Ricardo.

"To be sure," Hanaud agreed hastily and with all possible deference. "But I find nothing odd in this letter."

"You were feeling it delicately with the tips of your fingers, as though some curious sensation passed from it into you."

Hanaud shook his head.

"A mere question in my mind whether there was anything strange in the texture of the paper. But no! It is what a thousand hotels supply to their clients. What troubles you, my friend?"

With even more hesitation than Joyce Whipple had used, Mr. Ricardo repeated the account which she had given to him of her disquieting reactions to letters written in that hand. Joyce had confessed that even to herself, when she came to translate them into spoken words, they shredded away into nothing at all. How much more elusive they must sound related now at second hand to this hard-hearted trader in realities? But Hanaud did not scoff. Indeed, a look of actual discomfort deepened the lines upon his face as the story proceeded, and when Mr. Ricardo had finished he sat for a little while silent and strangely disturbed. Finally he rose and placed himself in a chair at the table opposite to his friend.

"I tell you," he said, his elbows on the cloth and his hands clasped together in front of him. "I hate such tales as these. I deal with very great matters, the liberties and lives of people who have just that one life in that one body. Therefore I must be very careful, lest wrong be done. If through fault of mine you do worse than lose five years out of your few, if you keep them, but keep them in hardship and penance, nothing can make my fault up to you. I must be always sure—yes, I must always know before I move. I must be able to say to myself, 'This man or that woman has deliberately done this or that thing which the law forbids,' before I lay the hand upon the shoulder. But a story like yours—and I ask myself, 'What do I know? Can I ever be sure?'"

"Then you don't laugh?" cried Mr. Ricardo, at once relieved and impressed.

Hanaud threw wide his hands. "I laugh—yes—with my friends, at my friends, as I hope they laugh with me and at me. I am human—yes. But stories like this one of yours make me humble too. I don't laugh at them. I know men and women who have but to look into a crystal and they see strange people moving in strange rooms, and all more vivid than scenes upon a stage. But I? I see nothing—never! Never! It is I who am blind? Or that other who is crazy? I don't know. But sometimes I am troubled by these questions. They are not good for me. No! They make me uneasy about myself—yes, I doubt Hanaud! Conceive that, if it is possible!"

He unclasped his hands and flung out his arms with something burlesque and extravagant in the gesture. But Mr. Ricardo was not deceived. His friend had confessed the truth. There were moments when Hanaud doubted Hanaud—moments when he, like Mr. Ricardo, was aware of cracks in the opal crust.

Hanaud bent his eyes again upon that handwriting which had so alarming a message for just one person alone, and not an atom of significance for the rest.

"She has broken off her engagement—this young lady. Miss Tasborough," he said, pronouncing the name as Tasbruff. "That is curious too." He sat for a moment or two in an abstraction. "There are three explanations, my friend, of which we may take our choice. One. Your Miss Whipple is playing some trick on you, for some end we do not know of. To establish her credit—after some—thing has happened. To be able to say: 'I foresaw—I tried to avert it. I warned Mr. Ricardo.' Eh? Have you thought of that?"

He nodded his head slowly and emphatically at his friend, who certainly had not thought of anything of the kind. But the notion disturbed Mr. Ricardo a little now. He had after all been troubled on his way home after that conversation. Troubled by an excuse which Joyce Whipple had given for her own inability to interfere. "Cinderellas must be off the premises by midnight." What sort of an excuse was that for a young lady with a pipe-well of oil in California? No, it certainly wouldn't do!

But Hanaud, reading his thoughts, raised a warning hand. "Let us not run too fast. There are still two explanations. The second? Miss Whipple is an hysterical—she must make excitements. She is vain, as the hysterical invariably are."

Here Mr. Ricardo shook his head; as emphatically as a moment ago Hanaud had nodded his. That spruce young lady with tidiness for her monomark dwelt thousands of leagues away from the country of hysteria. Mr. Ricardo preferred explanation number one. It was more likely and infinitely more thrilling. But he must not be in a hurry.

"And your third explanation?" he asked. Hanaud pushed the letter back to Ricardo and rose from his chair, slapping his hands against his hips.

"Why, simply that she was speaking the truth. That some warning came to her through that handwriting, even though the writer knew nothing of the warning she was sending."

Hanaud turned away to the window and stood for a while looking out over the little pleasant spa, its establishment of baths down here by the park, its gay casino over there, and its villas and hotels shining amongst green streets. But he was deep in his own reflections. He might have been gazing at a wall for all that he saw. Mr. Ricardo had seen him in such a mood before, and he knew that this was a moment which it would be definitely inadvisable to interrupt. A sensation of awe stole over him. He felt the floor of the opal very brittle beneath his feet.

Hanaud turned his head towards his companion, without in any other way relaxing his attitude.

"The Château Suvlac is thirty kilometres from Bordeaux?" he asked.

"Thirty-eight and a half," Mr. Ricardo replied helpfully. He was nothing if not accurate.

Hanaud turned once again to the window. But a minute afterwards, with a great heave of his shoulders, he shook his perplexities from him.

"I am on my holiday," he cried. "Let me not spoil it! Come! Your servant, the invaluable Thomson, shall pack up my Hanaudski paraphernalia and send it back at your expense to the Odéon Theatre from which I borrowed it yesterday. You and I, we will motor in your fine car to the Lake Bourget, where we will take our luncheon, and then like good wholesome tourists we will make an excursion on the steamboat."

He was all gaiety and good-humour. But he had broken in upon the sacred curriculum of his holiday; and all that day, as Mr. Ricardo was aware, some grave speculations were with an effort held at bay.

MR. RICARDO progressed in a leisurely fashion from Bordeaux, staying a day here and a night there, and arrived at the Château Suvlac at six o'clock on the evening of the twenty-first of September, a Wednesday. The day of the week is important. For the last mile he had driven along a private road which sloped gently upwards. On the top of this rise stood the house, a deep quadrangle of rose-pink stone with its two squat round turrets breaking the line of the main building at each end, and the two long wings stretching out to the road. The front of the quadrangle was open, and in the middle of this space rose a high arch completely by itself, like some old triumphal arch of Rome. This side of the house looked to the south-west, and the ground fell away from it in a slope of vineyard to a long and wide level of pasture. At the end of this plain of grass there rose a definite hill upon which, through a screen of trees, a small white house could just be seen. As Mr. Ricardo stood with his back to the Château Suvlac, stretching his legs after his long drive, he saw that a secondary road struck off at the end of the sloping vineyard, descended the incline, passed a group of farm buildings and a garage just where the vineyard joined the pasture-land, but on the opposite side of the road, and climbed again towards the small white house.

Plan of Château Suvlac.

No one of the house-party was at home except the aunt and

chaperon, Mrs. Tasborough, who was lying down. Mr. Ricardo was

served with a cup of tea by Jules Amadée, the young manservant,

in the big drawing-room, which opened on to the stone terrace and

looked out over the wide Gironde to the misty northern shore.

Having drunk his tea he sauntered out on to the terrace. Four

shallow steps led down into a garden of lawns and flowers, and on

his right hand a closely planted avenue of trees sloped almost to

the hedge at the bottom of the garden, sheltering the house and

shutting out from its view the massive range of chäis

where the wine was stored and the big vats were housed.

Mr. Ricardo walked down across the lawn to the hedge and, passing through a gate on to a water meadow, saw a little to his right a tiny harbour with a landing-stage to which a gabare, one of those sloop-rigged heavy sailing boats which carry the river trade, was moored. A captain and two hands were engaged in unloading stores for the house. Mr. Ricardo, curious as ever, made his inquiries. The captain, a big black-bearded man, was very willing to accept a cigarette and break off his work.

"Yes, monsieur, these are my two sons. We keep the work in the family. No, the gabare is not mine yet. Monsieur Webster, the agent of mademoiselle, bought her and put me in charge, and when I pay off the cost she will be mine. Soon?" The captain flung out his arms in a gesture of despair. "It is difficult to grow rich on the Gironde. For half of our lives we are waiting for the tide. See, monsieur! But for those cursed tides, I could finish my work here, and start back for Bordeaux later in the night. But no! I must wait for the flow and I shall not put out until six o'clock in the morning. Ah, it is difficult for the poor to live, monsieur." He had his full share of the French peasant's compassion for himself, but he was sitting on the stout bulwark of the boat and he began to stroke and caress the wood as though there were nothing nearer to his heart. "The gabare is a good gabare," he continued. "She will last for many years, and perhaps I shall own her sooner than a lot of people think."

His little eyes, set too close together under heavy black eyebrows, gleamed unpleasantly. He had not only the self-pity of his kind but its avarice too. He was not, however, very clever, Mr. Ricardo inferred. No man could be clever who paraded such an air of cunning before a stranger. The captain, however, waked to the knowledge that his two sons had stopped working too. He thumped upon the bulwark.

"Rascals and good-for-nothings, it is not to you that the gentleman talks! To work!" he cried in a rage. "Bah! You are only fit to turn the paddles of Le Petit Mousse in the public gardens."

Mr. Ricardo smiled. He had sauntered through the public gardens at Bordeaux only yesterday. He had seen Le Petit Mousse, a little pleasure boat shaped like a swan, floating on an ornamental water. It had two little paddle wheels which were turned by two little boys, and on Sundays and fete days it set out upon adventurous little voyages under the palms and chestnuts.

The youths resumed their work, and Mr. Ricardo turned away from the little dock. He noticed, without paying any particular attention to the circumstance, the name upon her bows—La Belle Simone. He would probably never have noticed it at all, but the first two words of it were weathered and the third stood out glaringly in fresh white paint. Inquisitiveness made him ask: "You have changed her name?"

"Yes. I named her La Belle Diane. A little compliment, you understand. But Monsieur Webster said no, I must change it. For mademoiselle would think she looked the fool if ever she perceived it. Not that mademoiselle perceives very much these days," and his little black eyes glittered between half-closed lids. "However, I changed it."

Mr. Ricardo turned away. He walked back along the broad avenue and saw beyond the border of trees, on the far side from the house, a little chalet of two storeys, which stood by itself in an open space, and was approached by a small white gate and a garden bright with flowers. It was now, however, seven o'clock, and without exploring it Mr. Ricardo returned to the drawing-room. There was still no sign of the house-party. He rang for Jules Amadée, and was conducted by him to his bedroom at the very end of the eastern wing. It was a fine big room with two windows, one in the front which commanded the sloping vineyard, the pasture land and the wooded hill opposite, the other at the side, looking upon the avenue and affording a glimpse of the little chalet beyond. Mr. Ricardo dressed with the scrupulous attention to his toilet which not for the kingdom of Tartary would he have modified; and he was still giving the final caress to the butterfly bow of his cravat when, over the top of the looking-glass, he saw a youngish man in a dinner-jacket cross the avenue towards the château. The reason for the chalet was now clear to Mr. Ricardo.

"A guest-house for the younger bachelors," said he. "Thomson, my pumps and the shoehorn, if you please."

He walked down the long corridor—he was astonished to notice what a large tract of ground the house covered, and how many empty rooms stood with their doors open—turned to the left at the end of it, and came to the drawing-room, which was in the very centre of the main building. As he stood at the door, the hall and the front door was just behind him. He stood there for a few moments, listening to a chatter of voices and invaded by an odd excitement. Was he to solve by one flash of insight the mystery of Joyce Whipple's letters? Was he to look round the room and identify by an inspiration the sinister figure of the person who had detained Diana Tasborough in the seclusion of Biarritz throughout the summer?

"Now," he said to himself firmly. "Now," and with a gesture of melodrama he flung open the door and stepped swiftly within. He was a little disappointed. Certainly there was a moment of silence, but the abruptness of his entrance accounted for that. No one flinched, and the interrupted conversations broke out again.

Diana Tasborough, looking as pretty as ever in a pale green frock, hurried to him.

"I am so glad that you could come, Mr. Ricardo," she said pleasantly. "You know my aunt, don't you, very well?"

Mr. Ricardo shook hands with Mrs. Tasborough.

"But—I am not sure—I think Mrs. Devenish is a stranger to you."

Mrs. Devenish was a young woman of about twenty-five years, tall, dark of hair, with a bright complexion, and black liquid eyes. She was brilliant rather than beautiful, big, and she suggested to Mr. Ricardo storms and wild passions. It passed through his mind that if he ever had to take a meal with her alone, it should be tea and not supper. She gave him her right hand negligently, and by chance Mr. Ricardo's gaze fell upon the other. Mrs. Devenish wore no wedding-ring, no jewels indeed of any description.

"No, I don't think we have ever met," she said with a smile, and suddenly—it was certainly not due to her voice, for he had never heard her utter a word before, it may have been due to some gesture of her hand, or to some movement of her body as she turned to resume her conversation, it was probably due to the slowness of Mr. Ricardo's perceptions—anyway, suddenly he was conscious of a thrill of triumph. So quickly had he solved Joyce Whipple's problem. Mrs. Devenish was the dominating force which menaced Diana Tasborough. She was the malignant one. It was true that he had not met her before, but he had seen her, and in just those morbid circumstances which settled the question finally.

"Yet, I saw you, I think, exactly nine days ago in Bordeaux," he said, and he could have sworn that terror, sheer, stark naked terror, stared at him out of the depths of her eyes. But it was there only for a moment. She looked Mr. Ricardo over from his pumps to his neat grey hair and laughed.

"Where?" she asked; and Mr. Ricardo was silent. It was an awkward, bold question. He was more than a little shy of answering it. For he would be accusing himself of a taste for morbidities if he did. He might look a little puerile, too.

"Perhaps I was wrong," he said, and Mrs. Devenish laughed again and not too pleasantly.

Mr. Ricardo was rescued from his uncomfortable position by his young hostess, who laid her hand upon his arm.

"You must now make the acquaintance of your host that was to have been," she said. "Monsieur Le Vicomte Cassandre de Mirandol."

Mr. Ricardo had been startled by the previous introduction. He was shocked by this one. No doubt, he reflected, there were all sorts of crusaders, but he could not imagine this one storming the walls of Acre. He was a tall, heavy, gross man with a rubicund childish face, round and dimpled; he had a mouth much too small for him and fat red lips, and he was quite bald.

"I shall look upon your visit to me as merely postponed, Mr. Ricardo," he said in a thin, piping voice, and he gave Mr. Ricardo a hand which was boneless and wet. Mr. Ricardo made up his mind upon the instant that he would rather abandon altogether his annual pilgrimage than be the guest of this link with the Crusaders. He had never in his life come across so displeasing a personage. He should have been ridiculous, but he was not. He made Mr. Ricardo uncomfortable, and the feel of his wet boneless hand lingered with the visitor as something disgusting. He could hardly conceal his relief when Diana Tasborough turned him towards the man whom he had seen crossing from the chalet.

"This is Mr. Robin Webster, my manager, and my creditor," said Diana with a charming smile. "For I owe to him the prosperity of the vineyard."

Mr. Webster disclaimed the praise of his mistress very pleasantly. "I neither made the soil nor planted the vines, nor work any miracles at all, Mr. Ricardo. Mine is a simple humble office which Miss Tasborough's kindness makes a pleasure rather than a toil."

The disclaimer might have sounded just a trifle too humble but for the attractive frankness of his manner. He was of the average height with quite white hair, and a pair of bright blue eyes. But the white hair was in him no sign of age. Mr. Ricardo put him down at somewhere between thirty-five and forty years of age, and could not remember to have seen a man of a more handsome appearance. He was clean-shaven, fastidious in his dress, with some touch of the exquisite. He spoke with a certain precision in his articulation which for some unaccountable reason was familiar to Mr. Ricardo; and altogether Mr. Ricardo was charmed to find anyone so companionable and friendly.

"I shall look forward to seeing something of the vintage under your guidance tomorrow, Mr. Webster," he said; and a voice hailed him from the long window which stood open to the terrace.

"And not one word of greeting for me, Mr. Ricardo?"

Joyce Whipple was standing in the window relieved against the evening light. Of the anxiety which had clouded her face the last time he had seen her, there was not a trace. She was dressed in a shimmering frock of silver lace, there was a tinge of colour in her face, and she smiled at him joyously.

"So, after all, you put off your return to America," he said, advancing eagerly towards her.

"For a month, which is almost ended," she replied. "I am leaving here tomorrow for Cherbourg."

"If we let you go," said de Mirandol gallantly; a phrase which Mr. Ricardo was to remember.

Mr. Ricardo was introduced to two young ladies from the neighbourhood and two young men from Bordeaux, none of whose names were sufficiently pronounced for him to distinguish them. But they were merely guests of the evening, and Mr. Ricardo was not concerned with them.

"For whom do we wait now, Diana?" Mrs. Tasborough's voice broke in rather pettishly.

"Monsieur l'Abbé, aunt," Diana answered.

"You should persuade your friends to be punctual," said the aunt, and there was no gentleness in that rebuke. Mr. Ricardo had been startled and shocked. Here was a third riddle to surprise him. He remembered Mrs. Tasborough as the most submissive of pensioned relations, a chaperon who knew that her duties did not include interference, a silent symbol of respectability. Yet here she was interfering and talking with all the authority in the world. No less surprising was Diana's meekness in reply.

"I am very sorry, aunt. The Abbé is so seldom late for his dinner that I am afraid that he has met with an accident. I certainly sent the car for him in good time."

Mrs. Tasborough shrugged her shoulders, and was not appeased. Mr. Ricardo looked from one to the other. The old lady in her dowdy, old-fashioned dress sitting throned in a great chair, the pretty niece in her modern fineries humble as a village maid. There was a reversal of positions here which thoroughly intrigued Mr. Ricardo. He glanced towards Joyce Whipple, but the door was opening, and Jules Amadée announced:

"Monsieur l'Abbé Fauriel."

A little round man in a cassock, with a ruddy face, thick features and a small pair of shrewd twinkling grey eyes, bustled into the room in a condition of heat and perturbation. "I am late, madame. I express my apologies upon my knees," he protested, raising Mrs. Tasborough's hand to his lips. It was noticeable perhaps that he looked to her as his hostess. "But when you hear of my calamity you will forgive me. My church has been robbed."

"Robbed!" Joyce Whipple cried in a most curious voice. There was dismay in it, but not surprise. The robbery was unexpected, and yet, now that it had happened, not unlikely.

"Yes, mademoiselle. A sacrilege!" and the little man threw up his hands.

"My church has been robbed. It is a sacrilege!"

"You shall tell us about it at the dinner-table," said Mrs. Tasborough, cutting him short. Mrs. Tasborough was a Protestant. At home she sat under a man who preached in a Geneva gown. The robbery of a Roman Catholic church was to her a very minor offence, and dinner should not be delayed by it.

"It is true, madame; I forget my manners," said the Abbé Fauriel, and, indeed, he had barely time to greet the rest of the party before dinner was announced.

The rest of that evening passed apparently as uneventfully as most evenings pass in country houses. But Mr. Ricardo, whose faculty of observation was keyed up to a sharper pitch than usual, did notice during the course of it some things which were odd. The Abbé Fauriel's complaint, for instance. No money had been stolen, nor any sacred vessel from his church, but a vestment of fine linen, the alb, which he wore when he celebrated Mass, and a little scarlet cassock and white surplice used by the young acolyte who swung the censer.

"It is unbelievable!" the old man cried. "They were of value, to be sure. My dear Madame de Fontanges, now dead, presented them to the church. But they must be cut up at once and then their value is gone. Who would commit a sacrilege for so small a gain?"

"You have, of course, informed the police," said the Vicomte de Mirandol.

"But understand, Monsieur Le Vicomte, that it is only within the hour that I discovered my loss. You would all realize" —and a twinkle of humour lit up his face—"if you were not all heathens, as you are, that tomorrow is the feast of Saint Matthew, a most sacred day in the Calendar of the Church. I went to the sacristy to assure myself that those garments of high respect were in order, and they are gone. However, Madame Tasborough, I must not spoil your evening with too much of my misfortune," and he swerved off into an amusing dissection of the foibles of his parishioners.

A small interruption brought him in a moment or two to so abrupt a stop that all eyes were turned on the interrupters. Mrs. Devenish was the cause of the interruption. She had been taking no part in any of the conversation, beyond answering at random when she was addressed, and sat occupied by some secret thought of her own. But once she shivered, and so violently that the little bubbling cry which people will utter involuntarily when they are freezing, broke from her lips. The sound recalled her to her environment, and she glanced guiltily across the table. Her eyes encountered Joyce Whipple's, and Joyce suddenly exclaimed in a queer, sharp, high-pitched voice:

"It's no use blaming me, Evelyn. It's not I who dispense the cold," and then she caught herself up too late, her face flushed scarlet, and in her turn she looked quickly from neighbour to neighbour. This was the first sign which Mr. Ricardo got, that under the smooth flow of talk nerves were strained to the loss of self-control by secret preoccupations. The Abbé Fauriel was even quicker than Mr. Ricardo to notice it. His eyes darted swiftly to Evelyn Devenish, and from her to Joyce Whipple. His face, in spite of the long, drooping nose and the thick jaw, became alert and birdlike.

"So, mademoiselle," he said slowly to Joyce, "it is not you who dispense the cold. Who, then?"

He did not insist upon an answer, but a moment or two later, when, as if to cover Joyce Whipple's confusion, the chatter in her neighbourhood broke out afresh, Mr. Ricardo noticed that almost imperceptibly he made the sign of the Cross upon his breast.

So far Mr. Ricardo was little more than curious and excited. But a quarter of an hour afterwards he caught a momentary glimpse of passion which shook him from its sheer ferocity. The men had retired from the dinner-table with the ladies, in the French fashion, and had split up into little groups. Joyce Whipple was sitting in a low chair at the side of the hearth, her knees crossed and one slender foot in its silver slipper swinging restlessly, whilst on a couch at her elbow Robin Webster was talking to her in a low voice and with an attention so complete as to make it clear that there was no one else in the room for him at that moment. The Vicomte de Mirandol was chatting with Mrs. Tasborough and the Abbé. Evelyn Devenish stood near the window in a group with Diana and the two young Frenchmen. Suddenly from that group sprang a phrase which was heard all over the room.

"The Cave of the Mummies."

It was one of the Frenchmen who uttered it, but Evelyn Devenish took it up. The Cave of the Mummies is a famous show-place of Bordeaux. Under the soaring tower of St. Michel in the open square in front of the church there is an underground cavern where bodies, mummified by some rare quality of the earth in which they were originally buried, stand mounted in a row upon iron rests for all the world to see at a price of a few pence.

"It is a scandal," cried the Abbé. "Those poor people should be put decently away. It is a nightmare, that cavern, with that old woman showing off the points of her exhibits by the light of a candle!" He shrugged his shoulders with disgust and looked at Joyce Whipple. "Now I, too, mademoiselle—yes, now I, too, feel the cold."

Evelyn Devenish laughed. "Yet we all go to that spectacle, Monsieur l'Abbé. I plead guilty. I was there eight or nine days ago. It was there, too, I think, that Mr. Ricardo saw me."

She challenged that unhappy gentleman, with a smile of amusement, to deny the charge. But, alas, he could not. A taste for the bizarre was always at odds with his respectability.

"It is true," he said lamely, shifting his weight from one foot on to the other. "I had heard so much of it—I had so often passed through Bordeaux without seeing it. But now that I have seen it, I take my stand with Monsieur l'Abbé." He recovered his assurance and felt as virtuous as he now looked. "Yes, a dreadful exhibition; it should be closed."

Evelyn Devenish laughed again, quizzing him. "A most unpleasant young woman," said Mr. Ricardo to himself, "bold and without respect." He was relieved when she averted her eyes from him. But he observed that they travelled slowly round until they reached Joyce Whipple, and there for a moment they stayed, half hidden by the eyelids; but not hidden enough to conceal the hatred which grew slowly from a spark in the depths to a blaze of devouring fire. Mr. Ricardo had never seen in his life the evidence of a passion so raw. It was covetous to punish and hurt. The dark eyes could not leave, it seemed, the girl radiant in her silvery frock. They rested with a dreadful smile upon the foot swinging in its gleaming slipper and ran up the slim leg in its silken sheath to the bent knee. Mr. Ricardo understood by a flash of insight the cruel thought behind the eyes and the smile. "Oh, certainly, it would have to be to tea and not to supper," he said to himself, almost in an agony as he thought of that imaginary meal alone with Evelyn Devenish which his fears had conjured up.

Diana Tasborough crossed the room to him. "You will play whist, with my aunt and the Abbé and de Mirandol, won't you?" she pleaded. "It must be whist, for the Abbé has never played bridge"; and plaguing his brains to recollect how the game of whist was played, he was led to the card-table.

So far, then, Mr. Ricardo had undoubtedly earned some good marks, not so much for putting two and two together as for discerning that there might be two and two which would possibly want putting together afterwards. But at this hour, half-past nine by the clock, he ceased to be meritorious, and the most important circumstance of the whole evening completely escaped his observation. He was really too much occupied in the effort to revive his recollections of whist; which was made even more difficult by the action of the younger members of the party.

The dining-room, drawing-room and library of the Château Suvlac were arranged in a suite, the drawing-room being in the middle; and all of these rooms had windows to the ground opening upon the broad terrace. Diana, as soon as the elders were seated at the card—table, went into the library and set a gramophone playing. Within the minute all the young people were dancing upon the terrace. The connecting door between the salon and the library was shut, it is true, but the night was warm and all the windows stood open. So the music with its pleasant lilt floated in to the card players, and joined with the rhythmical scuffle of the dancing shoes upon the flags to distract Mr. Ricardo from his game. It was the time of moonlight, but the moon was obscured by a thin fleece of white clouds so that a pale silvery and rather unearthly light made the garden and the wide river beyond a fairyland of magic. On the far shore a light twinkled here and there through a mist, and close at hand, the long avenue of trees, now black as yews and motionless as metal, protected the terrace as though it was some secret and ancient place of sacrifice. But instead of sacrifices, Mr. Ricardo saw the flash of white shoulders, the sparkling embroideries upon the light frocks of the girls, the dancers appearing, disappearing, gliding, revolving, and altogether he made so many mistakes that his fellow players were delighted when the rubber came to an end. Robin Webster came in from the terrace. "You will excuse me, Mrs. Tasborough. The morning begins for me at daybreak, and I have still a few preparations to make before I can go to bed."

"I too," said the Vicomte de Mirandol, rising from his chair, a trifle abruptly perhaps. "The Mirandol wine will not compare with the Château Suvlac, alas! Yet I must take just as much care of it." He looked out of the window rather anxiously. "A good shower or two, not too violent, just for a couple of hours during the night—that would help us, Monsieur Webster. Yes, two hours of gentle rain—I beg you to pray for them, Monsieur l'Abbé."

Mr. Robin Webster shook hands with Mr. Ricardo. "You said that you would like to come round with me tomorrow," he said. "I live in the chalet beyond the avenue. It is my office too. You will find me there or about the chäis."

He went out through the window, Monsieur de Mirandol through the door to the front of the house, where his car waited for him. Jules Amadée brought in a tray of refreshments, and Mrs. Tasborough lifted her voice petulantly.

"Diana! Diana!" she cried. "Will you please come in at once and prepare his nightcap for Monsieur l'Abbé!"

The Abbé, however, would by no means break in upon the girl's enjoyments. "I can mix my grog very well for myself, madame. Let mademoiselle dance, and so I can put a little more of your excellent whisky into my glass than it would be seemly for me to allow mademoiselle to do."

As he moved towards the table Joyce Whipple stood in his way. "And I," she said, laughing, "since I know nothing of the proper proportions, will in my ignorance put more whisky into your glass than you would."

Joyce Whipple, in a word, took possession of the buffet. It was in a corner of the room and she stood with her back to the company. A lemonade for Mrs. Tasborough, a whisky and soda for Mr. Ricardo, a hot grog for Monsieur l'Abbé. The young people drifted back into the room. Joyce Whipple served them all in their turn with beer and sirops and spirits, laughing gaily all the while, and proclaiming that she had a future as a barmaid. Diana came from the library and was the last to join the group.

"I shall have a brandy and soda with a lot of ice," she said, and again Mr. Ricardo was conscious of an unsteady note in her voice, and a laugh which threatened to rise out of gaiety into hysteria.

Joyce threw a quick glance backwards over her shoulder.

"So, after all, I do dispense the cold," she cried, and in her case, too, the words and the laughter on which they were launched were edged with excitement, and undoubtedly the glass which she held clattered against the siphon when she filled it, as though her hands trembled.

The party, however, was already breaking up and within a very few minutes the Château Suvlac was silent and Mr. Ricardo back in his own room. He opened both of the windows. When engaged upon the side-window, he saw that a light was still burning in a room upon the ground floor of the chalet. Mr. Robin Webster was still then at work in his office. Looking out from the front window his gaze wandered over the peaceful stretch of empty country. The white house upon the hill might have been black for all that he could make of it. Not a window glimmered anywhere. Mr. Ricardo wound up his watch and went to bed. It was then ten minutes to eleven.

MR. RICARDO was not the man to sleep comfortably in a strange bed, and though he did fall asleep quickly, he awaked whilst it was still dark; and with a vague uneasiness. He reached up for the light-switch, which in his house in Grosvenor Square was set into the wall above his head, and was disconcerted not to find it there. Gradually, however, he remembered. He was not at home. He was at the Château Suvlac, and discovering the cause of his uneasiness in the unfamiliar environment, his uneasiness itself departed. But he was now thoroughly awake.

He had his own remedies for this mischance. Sheep were of no use to him. He had counted most of the sheep upon the South Downs upon an unhappy night, but having missed one he had been forced to go back and count them all over again; and his annoyance at his carelessness had kept him awake till morning. His better plan was to throw open his curtains and raise his blinds, and the inrush of fresh air through the open windows as a rule quickly sent him off. He tried this cure now.

First of all he turned on his bedside lamp and looked at his watch. It was a few minutes before two o'clock in the morning. Then he rose from his bed and freed the side-window from all its coverings. He noticed that a light was still burning even at that late hour in the chalet beyond the avenue, but it was now upon the first floor and not in the office.

"Mr. Webster has finished his work and is now going to bed," he reflected with a warm approval of the young man's industry.

The next moment assured him that his judgment was correct. For whilst he looked, the light flickered and went out. Mr. Ricardo wished the manager a deeper repose than he was enjoying himself, and passed on to his front window.

He threw the curtains wide open with a rattle of rings, and wound the blind up with its roller. The country was spread wide in front of him upon this side, and the air fresher. The moon had set, leaving the night dark and clear and the sky gemmed with stars. But it was not the coolness of the air nor the blaze above his head which kept Mr. Ricardo standing in so fixed an attitude. When he had taken his last look from this window before getting into bed more than three hours ago, not one light had been burning in the white house upon the hill. Now the long range of windows was ablaze from end to end, shining clear in little oblongs of light where the front of the house was in full view, and throwing the trees into relief at the two ends. The building was illuminated like a palace.

"Now, what is the meaning of that?" Mr. Ricardo was asking himself. "Who in a country district would start the evening at so late an hour? It is very, very odd."

No answer being forthcoming, and his feet growing cold upon the polished boards of the floor, he retired to his bed and turned out his lamp. But his curiosity was thoroughly roused. From his position upon his pillows, he could see that golden blur upon the darkness. He could not but see it, he could not but think of it.

"This will never do," he said to himself. "I must try recipe number two."

Recipe number two was a book. But it must be read for itself, not as the gateway of dreams. If you put the thought of sleep altogether out of your mind and settled down to your volume, presto! the trick was done. You are aware suddenly of broad daylight, a cup of tea by your bedside and a lamp extravagantly burning. Mr. Ricardo's trouble was that he hadn't a book in his room. Very well then, he must go to the library and take one. So on went his light again. He got out of bed and into his pumps, draped his form in a Japanese dressing-gown of flowered silk, and with a box of matches in his hand stole oft along the corridors. He knew their geography by now, and one match took him to the dining-room door. The French windows of the three rooms en suite were undraped. He passed therefore through that room and the salon and into the library without having to strike a second match. He remembered that there was a light-switch in the library, close to the long window and just within the door. He was feeling for it when something dark on the terrace outside flicked past the panes and vanished. Mr. Ricardo was so startled that he dropped his box of matches on the floor. He stood in the dark, with his heart pounding noisily in his breast, not daring to move. And in the silence, even above the clamour of his heart, he heard a key grate in the lock.

The truth must be told. Mr. Ricardo's immediate impulse was precipitately to retire. But with an effort he rejected it as unworthy. The thought of the long corridor, too, through which he must return, daunted him. He stood his ground, and in a little while the fluttering of panic subsided. He was his own man again; and being so he could not leave things as they were, select a book and go quietly back to his bed. For the prospect of an adventure never failed to thrill him.

He opened the long window very cautiously and stepped out on to the pavement of the terrace. Far away a star beam trembled on the water of Gironde. Close to him upon his left the projecting round of the turret loomed largely, and from the front of it some rays of light streamed out. Mr. Ricardo moved cautiously forward from the angle made by the turret and the house wall; the light slipped out at the edges of a curtain drawn across a long window in the front of the turret. Someone was awake in the room behind the window. Someone had slid with the swiftness of a snake into that room and turned a key. Mr. Ricardo was in doubt what to do. He had heard of strange doings in country houses, even in England. How much more must he expect them in the gay atmosphere of France!

"I certainly don't want to butt into the middle of some highly illicit affair," he argued. "On the other hand, who knows what trouble may be occurring behind that curtained door? A sudden illness perhaps! Perhaps a crime! At the worst I can be sent about my business. At the best I may be of help."

Thus he stood and disputed. But his romantic disposition got the upper hand. He advanced and rapped gently upon the framework of the glass door; and at once the light went out. But with a speed so instantaneous that the knock upon the door and the extinction of the light seemed to be not so much two consecutive movements as two facets of the same one.

Mr. Ricardo had the most uncomfortable sensations. Someone in that room had heard the sound of his pumps upon the stone slabs of the terrace. That someone had been ever since half expecting and wholly dreading that he would knock upon the window, had been ready then with ears alert and fingers actually on the switch. But who? Mr. Ricardo's eyes could not pierce those curtains; nor had he the least excuse to renew his signal. He retired discreetly to his room without troubling to select a book from the library at all. There he watched one by one the windows on the hill recede into the night. But whether the emotions through which he had passed were the cause, or the mere movement and fresh air, he fell at once into a heavy sleep, and never stirred until the morning.