a treasure-trove of literature

treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership

(and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files)

or

SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or get HELP Reading, Downloading and Converting files) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

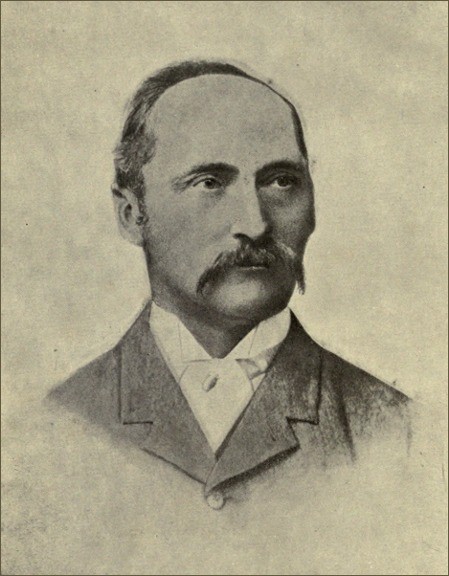

The Author. 1890.

Brisbane:

A. H. FRATER,

Inns Of Court, Adelaide Street.

1921

Printed by

H. Pole & Co. Limited,

Elizabeth Street, Brisbane.

The reasons for this book are as follow:—Whilst talking over early days with Mr. Courtenay-Luck, the popular Secretary of the Commercial Travellers' Club, that gentleman suggested that I should write a paper, to be read at a meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland.

In writing that paper, so many long-forgotten men, places and incidents came back to memory that I thought my reminiscences might prove interesting to others. I may be occasionally incorrect in dates, or in the sequence of events, but I relate facts and personal experiences. As they are, I leave them to the kind consideration of readers.

W. H. CORFIELD

Sandgate,

October, 1920.

As it is in the blood of most Englishmen from the "West Country" to seek adventure abroad, it is little wonder that the visit of an uncle from Australia strengthened a desire I felt to seek my fortune in that country. This uncle—H. C. Corfield—was the owner of some pastoral country in the Burnett district, and described in glowing terms life in the Australian bush. I might say here this was not all it had been painted, but that by the way.

And so it happened that on a cold, foggy morning in February, 1862, I found myself with an old schoolmate—George Custard—on board of, as it was then customary to advertise, "the good ship, 'City of Brisbane,' 1,100 tons burthen, 'Neville,' Master," which lay in Plymouth Sound, waiting her final complement of passengers for Queensland.

Mr. Henry Jordan, who was representing the Colony, came on board to address the passengers, who, he said, were going to a land of promise, where in the evening of his life, a man—as the reward of his labour—would sit in the shade of his own fig tree and enjoy the rest he had earned.

Soon the capstan was manned, and the anchor lifted to the old chantey:

[8] This we found was our good-bye to England, and, towed out by a tug, we commenced our long voyage to Australia. When well clear of the land, the tug dropped us, and with a favourable breeze, we made quick passage to the entrance of the channel.

By this time most of the passengers were suffering the usual disabilities felt by landsmen for the first few days at sea. I soon gained my sea legs, and was able to take a view of my surroundings.

Here we were—365 human beings, who would be cooped up for weeks in a sailing ship, and with as many different characters, sympathies and antipathies, one wondered if it could be possible to live long with harmony and unselfishness in such daily crowded contact. I suppose we were representative of the many, who, whether in the poop or steerage of similar ships, were looking hopefully towards the far off, not-long-named southern colony, which was becoming known to the people of Great Britain.

I was just nineteen, and all things looked bright and cheerful, but I was impatient for the time when, on a bounding steed, I would be scouring the plains, following the sheep and cattle on my uncle's property where, as an employee, I was to begin my adventures.

After a passage of 137 days, spent either in glorious runs before favouring winds, wearisome calms, or battling against heavy gales, we arrived in Moreton Bay, and in due course at Brisbane.

The city, as it was in 1862, has so often been described, that it is unnecessary for me to say anything as to its appearance. All I need say is that it did not enter my mind to anticipate its growth and importance.

Our ship's surgeon was Dr. Margetts, who, for many years afterwards, practised his profession at Warwick. It is to his credit that we had no deaths on the voyage, but immediately after landing, a little girl passenger died. I helped to dig her grave on the ridges somewhere out towards Fortitude Valley.[9] My destination was "Stanton Harcourt," 55 miles north-west from Maryborough, which my uncle held as a station. He was taking an active part in the great developments which, at this time, were being carried out by the squatters. I was directed by my uncle's agents, George Raff and Co., to engage five or six of the immigrants as shepherds. These accompanied me to Maryborough by the old steamer "Queensland." On arrival at Maryborough the shepherds were taken charge of by the local agents, and I was instructed to ride on to the station. I left Maryborough alone the same afternoon, but had not gone far when I found I was bushed. Riding back I struck the main road, and followed it to the public house at the Six-mile, which was a favourite camping place for carriers. My new-chum freshness immediately attracted the attention of the bullock-drivers camped there, who told me of the dangers I would meet from the blacks, unless I propitiated them by generous gifts of tobacco.

These stories so much impressed me that I bought a large quantity of tobacco from the publican. After that, when I saw any blacks, even if off the road, I would ride over and give some tobacco, which surprised and amused them considerably. I arrived at the public house, at a place known as "Musket Hat," in time for dinner. A gentleman who knew my uncle happened to be there, and whilst waiting for dinner, said, "Come out, and I will show you a good racehorse." Outside a horse was being groomed by a man, who took some pains to describe his good points. I appreciated the man's kindness, and on leaving handed him a shilling to buy a drink. This he took with a smile, and thanked me. I felt somewhat small when my friend told me that I had tipped the owner of the horse himself, and that he would tell the joke in such a way that it would be long before I forgot it, and this proved to be so.

Towards sundown, my friend left me at the turn off of the main road. My first ride through Australian bush was very lonely, and I was very timid. I heard what sounded like revolver shots, loud shouting, and much swearing. This I learned later was the ordinary language used when driving bullocks, while what I took to be revolver [10]shots, was the cracking of bullock-whips. At the time I imagined a battle was being fought with bushrangers, but it turned out that it was merely the station bullock teams going to Maryborough for stores, and to bring up the hands engaged by me, with their belongings.

I found the station in charge of a manager, and that my uncle had gone north in search of new country for the sheep. Grass seed and foot rot were playing havoc with the sheep on "Stanton Harcourt." Shortly after my arrival, 1,000 head of cattle purchased from White, of Beaudesert, reached the station. In those days pounds were unknown, and I now had my first experience in drafting cattle in an open yard. An old cow, evidently knowing that I was raw, came at me, and would have caught me, but that my hat fell off and attracted her attention. She impaled the hat instead of me. My next lesson was in bullock driving. I was sent with two loads of wool to Maryborough, having a black boy to drive one team, and another boy to muster the bullocks. These would not allow the black boys to go near them to yoke up, so I had to do this for both teams. After capsizing my dray three times on the road, and pulling down a fence in the town, I delivered the wool. The blacks had a short time before stuck up several drays, and carried the loading in their canoes across the river.

On the far side there was a dense scrub through which it was difficult to track them. My boys said I would be stuck up when passing this spot, so I rode on the dray, carrying a loaded revolver. However, I was not molested, probably due to the fact that, unknown to me, Lieutenant Wheeler with his troopers were at the moment busy among the blacks.

My uncle had returned before me, but had not been successful in securing country. When lambing came on, Custard and I were sent out without any special instructions to lamb a flock of ewes. Following the strong mob back to the yards in the evening, [11]the lambs tried my temper. I provided myself with stones, and being a fairly good shot, I reduced the percentage of lambs to some extent.

One night there was a great stampede in the yard, and thinking it was a dingo among the sheep, I went out with a gun. Seeing an object moving in the dark, I fired both barrels, and the supposed dingo fell. I had shot one of the ration sheep which had been dropped during the day. Being without any control or instructions in regard to the sheep, we decided our working hours to be—rise at 7 a.m., breakfast at 7.30, start work at 8. The sheep remained in the yard until the last-mentioned hour. This did not improve their condition. One morning my uncle arrived before we had turned out, and expressed himself strongly upon the laziness of new chums in general. Excusing ourselves by the fact that it was not yet seven did not calm the atmosphere. My uncle was one who insisted upon plenty of time for a long day's work. I very quickly learned the value of early rising in the bush, and in the interest of the sheep, when necessary, to go without breakfast.

I remember my first night alone in the bush. I was sent to an out-station with 300 sheep, and a black boy to assist in driving them. At sundown I could see nothing of the hut. I had read that fires would keep off native dogs or dingoes. I tied my horse to a tree, and gathered wood, forming a ring of fires around the sheep. The black boy said something to me in his own language. Thinking he asked me if he should bring some more wood, I replied with the only word I knew, "Yewi." After a little time I missed the boy, and cooeed for him. He replied as from a distance. I wondered why he had gone so far when there was plenty of wood close by. He did not return, and it was not long before my horse broke away. All night was spent walking around the sheep. What weird sounds I heard, and what strange shapes I saw moving. When one is alone in the bush at night, even after years of experience, the imagination is apt to run riot. Especially is it so at midnight and [12]towards the small hours of the morning. At daylight the sheep commenced to move. I followed them, carrying my saddle and bridle. About mid-day one of the station boys found me, and inquired why I sent the black boy home. It then dawned on me why I had been left alone. The boy had asked to be allowed to go home, and I had said "Yewi"—yes. I suppose I was only undergoing the usual bush experience of the new chum, and had a good deal to learn, but I was undoubtedly learning.

Following the cotton strike in England during 1863, a large number of Lancashire operatives emigrated to Australia. As the station needed shepherds, the agents in Brisbane were instructed to engage two married couples and three single men. I was despatched with a black boy, three horses and a dray, to bring them from Maryborough. Their luggage filled the dray, but I managed to find room for the two women and the children. The others had to walk. The first day out we reached Mr. Helsham's station at South Doongal. He allotted me an empty hut for the party. At dinner that evening I told him and the overseer how very frightened the emigrants were of the blacks. "Is that so," he said. "Well, we will try them to-night after the boys have had their evening corroborree." A number of blacks were camped there at the time, so he sent word to his station boys to come up. When they did so, he told them to surround the hut, and yell out, "Kill 'em white fella, kill 'em white Mary." We went down to see what we thought was fun. I never had to run harder than I did to reach the station before the new chums, who streamed out of the hut in their night attire, and made for the house. I had the greatest difficulty in pacifying them. They refused to return to the hut, and camped on the verandah, the single men remaining on watch.

After their flight from the hut, the pigs appropriated their rations which confirmed their belief in a narrow escape from wholesale slaughter. I felt sorry for the joke, more particularly as for the remainder of the journey they would not leave the dray, or go for water, unless the black boy or I went with them. As shepherds these men were not a success. They were invariably losing sheep, adding to my responsibility as overseer.

In September of that year, I had my first experience of shearing—getting through 20 the first day. It was back-aching and wrist-breaking work, and I longed for the day when I went out with the ration pack-horse.

In those days the sheep were hand-washed in a water hole, in which we worked up to our middle all day. The blacks had to be watched very closely, as, if opportunity offered, they would catch a sheep's hind leg with their toes, and drown the animal, expecting they would get the meat. I detected them in the act, so I burnt the carcase. This put an end to the practice. Mustering and branding the cattle followed the shearing, and these were much livelier occupations. We had a heavy wet season in that year, and I had plenty of opportunities to gain experience in flooded creeks. About April, 1863, Edward Palmer (years afterwards M.L.A. for Carpentaria), who was in charge of his uncle's station "Eureka," four miles from "Stanton Harcourt," started with the sheep depasturing there for the Gulf country. He eventually settled at Canobie, on the Williams River, a tributary of the Cloncurry.

[14]In September one of the new shepherds absconded, leaving his sheep in the yard at an out-station. I was instructed by my uncle to take out a summons, and applied to Mr. W. H. Gaden, a neighbouring squatter, for it. The summons was sent to Maryborough for service. In due time I had to appear as prosecutor. The man had engaged a solicitor, who, when the case was called on, applied for a discharge, as the summons did not state it was sworn to, but only signed W. H. Gaden, J.P. The man was discharged on these grounds. I was not sorry. He was useless as a shepherd, but through him I had obtained an enjoyable ride to Maryborough with all expenses paid.

My uncle in the meantime had again started out to seek new country for the sheep, and engaged Mr. Walter Carruthers, of Carruthers and Wood, Rocky Springs station, Auburn River, to take charge of the mob of 12,000, leaving instructions that they were to start before the end of 1864.

[15]Great preparations were required to equip the party. We were taking 30 saddle horses, two bullock teams, and one horse team. In addition to the stores, we had to provide all sorts of tools, etc., to build and form a new station.

I preferred to drive one of the bullock teams. My duties on arrival at camp were to erect a tent and two iron stretchers for Carruthers and myself, take my watch every night from three to daylight, and then to muster the bullocks. In the case of dry stages I also had to take water to the men.

When passing through Gayndah I purchased tobacco from John Connolly (who died lately at the very great age of 102 years), and for which I had to pay £1 per pound.

When we came to the Dawson River, near Mrs. McNabb's station, it was in flood. We felled a big tree across the stream, and with boughs and other timber, improvised a bridge. For three days we were working in our shirts only, getting the sheep and—when the water fell—the teams across. Mosquitoes, sandflies, and a hot sun made us nearly raw. Along this road Carruthers had his favorite horse "Tenby" stolen. He had hung the animal up to the verandah post of a wayside public house, to see the sheep and teams pass. After they had gone by, and while Carruthers was having a drink, a man jumped on the horse and galloped away. Carruthers walked on to the sheep, got a fresh horse, and with our black boy followed the thief until they came to the spot where, in a piece of scrub, he had pulled the mane and tail of the horse to alter its appearance. Darkness coming on, they had to abandon further pursuit. The horse was a very fine chestnut. A new saddle and bridle, a pouch containing cheque book and revolver, were taken with him, so the robber had a good haul. There were no telegraph stations out back in those days.

When passing Apis Creek, near the Mackenzie River, I met a man named Christie, whom I afterwards learnt was Gardiner, the ex-bushranger. We passed through Taroom, Springsure, [16]on to Peak Downs station, where we essayed a short cut on to the Cotherstone road, but when we had got half-way, the owner made us turn back. I had a very rough time driving the leading dray through the loose, black soil, and was glad to get back on the road, which was well beaten by the teams carrying copper from Clermont to Broadsound.

We eventually reached Lord's Table Mountain, where we had permission to remain, whilst I took the drays into Clermont to be repaired, and to obtain an additional supply of rations. Whilst staying at Winter's Hotel, I met Griffin, the warden—afterwards hanged for shooting the troopers guarding the gold escort, of which he was in charge.

I also met Fitzmaurice, destined in after years to become my partner in the far west. He had brought in drays from Surbiton station to be repaired.

Carruthers then rented some country from Rolfe, on Mistake Creek, on which to shear the sheep. I shore 800. My salary was now £80 per year, for which I acted as overseer, bookkeeper, and giving a hand as general utility at all kinds of work. After shearing, the sheep were taken down to Chambers' Camp, on the same creek, whilst I took the wool to Port Mackay. When crossing the Expedition Range, before reaching Clermont, on my way from Mistake Creek, I rode over to a small diggings to purchase meat. The only butcher was a man named Jackson, whose wife served me. She was a fine, comely woman, whom I afterwards met on the Lower Palmer, where her husband was keeping a store. He was burnt to death on Limestone Creek on that river. Eventually, she married Thos. Lynett, a packer from Cooktown to Edward's Town (as Maytown was popularly known), and who, with Fitzmaurice and myself, was, in later years, one of the founders of Winton, on the Western River. Mrs. Lynett lately died in Winton at the ripe age of 84, her husband, Tom Lynett, having pre-deceased her some years. Like most of the women who pioneered, she had a grand heart, and I learnt how the diggers appreciated her motherly kindness.

[17]The early wet season caught me at Boundary Creek, ten miles beyond Nebo. I was stuck in a bog for five weeks, rain pouring the whole time. I eventually delivered the wool, loaded up rations from Brodziak Bros., and started on my return journey. In those days the range was in a primitive state, and coming down my mate capsized his dray. While I was assisting him, I had a Colt's revolver stolen off my dray, presumably by some of the road party who were cutting down the steep parts.

After crossing the range, the pleuro broke out amongst my bullocks, and I lost one whole team. I went into Retreat station and purchased several steers. The hot weather and heavy pulling soon killed these, leaving me stranded on the Isaacs River. One day a squatter from North Creek station rode up, and hearing my plight, said there was a team of bullocks running on his country for several months. Who the owner was, or where they came from, was unknown. Acting on his hint, I picked out what I considered the best, and continued my journey to the sheep. Having met my requirements, I turned the bullocks loose. In response to enquiries, I denied that I was the owner of them; they had served my purpose, and I was content to let well alone.

The blacks were very bad, and continually worrying the men we had shepherding. One of these was rather daft. One night the rams did not return. I got on their tracks the next day and brought them to camp, but there was no sign of the shepherd. Two evenings after we were surprised to see a couple of Myalls bringing in the lost man. We gave the blacks some tucker, and they left, but not before the shepherd, raising his hat, said to them, "I thank you, gentlemen, most sincerely." His eccentric manner had doubtless saved his life, as the coloured races generally appear to respect a demented person.

I had a very bad attack of fever and ague, and managed to ride into Clermont, where I was treated by a chemist named Mackintosh, who kindly allowed me to stay at his house. I [18]shall never forget the kindness of him and his wife in pulling me through. Carruthers in the meantime had taken the sheep back to a creek which is still known as "Corfield's Creek." There the lambing took place.

We next moved down to Balgourlie Station, still on Mistake Creek, where we had an early shearing, and left the wool to be taken by carriers to Bowen.

I now had my first experience of what was called in those days, "Belyando Spew." Everything one ate came back again and no one seemed to know of an antidote to what appeared to be a summer sickness. The gidya around seemed to accentuate the complaint, until I became a walking skeleton.

In the meantime we received word that my uncle had purchased Clifton Station from Marsh and Webster, of Mackay.

This country was situated on a billabong 12 miles from Canobie, where Edward Palmer, as I have previously mentioned, had settled down.

The travelling away from the gidya scrubs down the Belyando River soon dispelled all signs of the sickness.

Previous to leaving Balgourlie Station we had lost a mob of horses, and on our arrival at Mount McConnell Station, the two men who had been despatched to look for them, returned without success. Carruthers then sent me back with an Indian named "Balooche Knight" to make a search. We had a riding horse each, and a pack horse to carry our blankets, tucker, etc. After scouring all the scrubs on Mistake Creek, we arrived at Lanark Downs Station, where a traveller informed me he had seen a number of horses at Miclere Creek, 17 miles on the road to Copperfield. My optimism suggested I should ask the owner of Lanark Downs to lend me a fresh horse. He did so, and I rode away one morning, returning the same evening with the whole of the 17 horses we had lost. I had now to travel over one hundred miles to where I had left the sheep, which were still continuing their journey. It was a most enjoyable ride [19]with only one drawback. The Indian's blankets and mine being together, I had gathered a lively community in my head. Procuring a small tooth-comb at a way-side place, I commenced operations, with the result that soon I had quite a colony on a newspaper in front of me. With the aid of tobacco water, I finally succeeded in driving the pests away.

In following down the Belyando River, I proved my expertness as a tracker by recognising the track of a bullock crossing the road. I did not know the beast had been lost, but the peculiarity of the track, caused by the hind feet touching the ground ahead of the fore feet, led me to follow the tracks through a scrub, and there I found him camped. We had over 60 miles to overtake the sheep, and as he could not keep up with the horses, I had to leave him.

We had passed St. Ann's and Mt. McConnell's Stations where Lieutenant Fred Murray was stationed with his black trackers. Proceeding up the Cape River, we overtook the sheep at Natal Downs, then owned by Wm. Kellett. We left the Cape River here, and followed Amelia Creek through a lot of spinifex country.

On the third camp, in my early morning watch, I noticed several of the sheep jumping. At daylight we found about 60 lying dead on the ground. We learnt that they had been eating the poison bush which abounds throughout what is designated as the "Desert Country."

The leaf of this bush is shaped like an inverted heart, and in colour is a very bright green. The flower resembles a pea blossom, and when in bloom the bush is most deadly to all stock. This experience taught us to be more careful, and in one place we cut a track through five miles of it for the sheep to pass.

When we reached Torren's Creek, we saw a water-hole containing the bones of some 10,000 sheep which had perished from the same cause. They were a portion of 20,000, which, [20]we were informed, were in charge of a Mr. Halloran, who had preceded us for the Flinders, and owned by a Mr. Alexander.

We afterwards passed a green flat, quite dry, but in the wet season covered with water, called "Billy Webb's Lake."

I was suffering from a severe attack of sandy blight in both eyes, so had to ride a horse which was tied to the bullock dray. I was hors-de-combat for over a week. Not having any eye-water, the only relief I could get was cold tea leaves at night. Both eyes were so swollen that I was completely blind. Fortunately, we met the McKinlay expedition returning from an unsuccessful search after Leichhardt. The doctor gave me a bottle of his eye-water, which he informed me contained some nitrate of silver; this he instructed me how to use, and I soon regained my eye-sight, but the eyes continued very weak.

Shortly afterwards we met some travellers, and enquired how far it was to the jump-up—meaning the descent from the plateau to the level country at the head of the Flinders. They replied, "in two miles you will be amongst the roly-poly."

These we found were not stones, as we thought, but dry stumps of a weed which grows on the open downs in the shape of a ball. The strong trade-winds blow the plant away from its roots, and send it careering over the downs, jumping for yards, and high in the air, frightening one's horse when it gets between his hind legs, giving him the impression that he had slept, and dreamt he was young again.

We passed Hughenden Station, which had just been taken over by Mr. Robert Gray from Mr. Ernest Henry, and camped the sheep where the town of Hughenden now stands.

We then had a long stage of fifteen miles to the bend of the river without water. The remainder of our trip down the river was uneventful. We passed Telemon (Stewart's), Marathon (then owned by Carson), Richmond Downs (Bundock and Hayes), Lara (Donkin Brothers), and Canobie (Edward Palmer).

[21]At Clifton, our destination, there was a fine water-hole two and a-half miles long, trees on the banks were crowded with cockatoos, corellas, with galahs in flocks on the plains.

Work soon commenced in earnest, and progress made, in building a small house, sheep yards, and the necessary improvements for a sheep station. The country consisted of plains, with patches of scrub between, in which there was abundance of salt-bush, all carrying good feed for the sheep.

Mr. Carruthers' agreement to take charge of the sheep until they arrived at their destination having expired, my uncle wrote me to take over the station, and advised that if I remained in charge, he would increase my salary to £200 per year. As Carruthers was anxious to return to his station, I accepted the former, but replied that unless the pay for managing was increased to £300 per year, to send someone at once to take my place.

In the meantime, the blacks had come into Canobie at night, and attacked three men who were camped on the river, within sight of the station. They killed two, and the third was left for dead. He was found to be alive, and afterwards recovered from the severe battering he received.

Palmer sent word asking me to send all the men I could spare to come over to assist in hunting the murderers. I did so, Carruthers taking charge of the armed party.

A few days previous to this occurrence I had visited an out-station to count the sheep, taking a man with me to help in repairing the yard.

On returning after dark we passed a billabong, from which a very strong stench, as if from decomposed vegetable matter, arose. The following morning we both felt unwell, and vomited a good deal. The man with me was much older than I, and succumbed to the sickness in nine days.

After the party had left for Canobie, I was completely prostrated, and had no medicine on hand except Epsom salts. During the night we (the cook, a new-chum Cockney, and myself) heard voices down at the water-hole, which we took as from a [23]party of travelling Chinamen. In the morning we found that, some of the blacks who were implicated in the murder had doubled back, and had taken away every article of iron they could find, our camp oven included, and my clothes, which had just been washed. This so preyed on my mind that when the party returned, they found me delirious.

Mr. Carruthers, seeing the helpless state I was in, and the condition of affairs generally, engaged Mr. Reg. Uhr to take charge on my behalf, whilst he took me down to Burketown, distant 155 miles, in a cart, with two horses. The road was almost deserted, and the blacks were very bad. Carruthers would boil his billy at water-holes in the afternoon, and go out to the centre of the plains to camp, with no bells on the horses. As for myself, I was sick and weak. Not being able to eat damper or meat, I was almost starved, lost all vitality, and cared little whether I survived the trip or not. We had to cross the "Plains of Promise." These consisted of an uninterrupted run of about 30 miles of devil-devil country. It was a succession of small gutters and mounds, which, to a sick man in a cart without springs, was intolerable. We arrived at Burketown about November, 1866, and the public house was the only place in which I could get accommodation. There I suffered all the nightly noises incidental to a bush shanty.

Burketown at this time was an almost new settlement, with a population of about 50 whites, but the number of graves of those who died within its short life from fever was more than twice as many, and increasing daily.

The Burketown fever was more virulent than any other I had hitherto or since come in contact with, and was supposed to be a kind of yellow jack fever, introduced by some vessel from Eastern countries.

The danger of a second introduction of the same, or perhaps worse, epidemic does not appear in these days to be realised in Australia.

[24]There was no doctor in the town, but a chemist named Peacock was practising as one. Just as I arrived, Captain Cadell, in the old "Eagle," arrived to send despatches of his explorations of the rivers on the west coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria, where the party had seen numerous herds of buffaloes.

Mr. Carruthers heard that there was a doctor with the expedition, and on his interviewing him, the latter said he would see me, provided I paid the fee to the resident doctor. This professional etiquette was agreed to. The doctor took great pains in diagnosing my case, which he called something between a gastric and jungle fever, and prescribed five grains of calomel every night. This I found later to have loosened my teeth, and 15 grains of quinine daily seriously affected my hearing. The local chemist was then sent for. He felt my pulse, looked at my tongue, and prescribed a box of Holloway's pills. I paid him his fee of one guinea, but almost needless to say which advice I followed.

I remained in Burketown about a fortnight, slowly recovering. Before leaving I purchased a microscope which was for sale, and presented it to the doctor of the expedition with sincere thanks for saving my life. During the time I was in Burketown, Mr. Sharkey, Lands Commissioner, came over from Sweers Island, and offered to submit my name for the Commission of Peace, and said Mr. Landsborough, the Police Magistrate, would swear me in. I declined the honour.

When returning to Clifton Station we spent a week at Floraville Station, on the Leichhardt River. Here I purchased stores for the station from Mr. Borthwick, who was managing for Mr. J. G. Macdonald. At this station there was a water-hole 25 miles long, and in bathing one would see crocodiles basking on the rocks and bank, but they appeared to be harmless. At the lower end of this hole there was a perpendicular drop of over 40 feet, with a very deep hole at the foot, infested by sharks and alligators. The tides came to this point.

[25]We called at Donor's Hill Station, where I first made the acquaintance of the Brodie brothers, one of whom afterwards managed Nive Downs for a number of years. The other—his twin brother—died in New South Wales not long since, after a long and successful business career. At this place I visited a cave containing many skulls of blacks, who had been dispersed by the whites, after committing a series of depredations in the district. I was told the cave was so dark that matches were lighted to allow of aim being taken at the blacks during the dispersal.

In later years, I have often thought what fortunes might have been won, or lost, or the settlement of Western Queensland been advanced by years, had the early seekers for pastoral country but known what was west of the so-called desert country, and south of the Flinders. This could only be learnt by forcing a way through the desert to the west instead of skirting its edge and going north. As it was, we, in following the Flinders down, were traversing some of the finest sheep country in the world, and did not realise there were millions of acres lying to the south, unknown, unowned. Ultimately, settlement of the west was affected more from Rockhampton than from northern ports; extending as it did from Springsure towards Tambo, Blackall, and thence north and north-west.

It seems, however, the irony of fate that Townsville, which did little or nothing towards the exploration or development of the country south from the Flinders, has obtained the trade of that portion of Queensland. But this is anticipating.

Mr. J. F. Barry, who first took up the country on the head of the Western River, was laughed at by residents of Blackall, when he rode in to have his application registered, and described the country. So that it might be recorded that his statements as to its quality would prove correct, he called the country "Vindex," by which it is now known as one of the finest sheep properties in Queensland.

[26]But let me quote from "The Polar and Tropical Worlds," written by two scientists, one apparently a German, the other designated "Scientific Editor of the American Cyclopedia." The book was published in 1877, eleven years or more after the north-western country was becoming occupied.

In alluding to the great deserts of the world, these authorities say:—"Perhaps the most absolute desert tract on the face of the globe is that which occupies the interior of the great island, or as it may not improperly be styled, 'Continent of Australia.'

"The island has an area of something more than 3,000,000 of square miles, nearly equal in extent to Europe.

"For the greater part of its circumference, it is bounded by a continuous range of mountains or highlands, nowhere rising to a great height, and for long distances, consisting of plateaus or tablelands.

"There is, however, a continuous range of water-shed, which is never broken through, and which never recedes any great distance from the Coast.

"The habitable portions of Australia are limited to the slopes of the mountains, and the narrow space between them and the sea. The interior, as far as is known, or as can be inferred from physical geography, is an immense depressed plain more hopelessly barren and uninhabitable than the great desert of Sahara."

These authorities say more on this imaginary desert, but the quotation is sufficient to show that even scientists do not know everything, although one might believe that they did.

I have not learnt that either Messrs. Landsborough or Phillips, who were on the Diamantina in 1866, and crossed from that river over to the Flinders, commented on the quality of the country through which they travelled, and I can only explain that its naturally waterless state up to early in the eighties prevented its value becoming known.

[27]During these years immense sums of money were spent in water conservations by the Government of the day and Victorian investors, and in a large measure without meeting success.

When I went to Townsville in 1868, the principal, and also the first carrier there, was a man named Courtney, who owned eight bullock teams. He had been taking stores to the different stations on the Flinders as that country was opened up. In conversation one day, he informed me that some two or three years previously his bullocks had strayed many miles across the downs from Richmond Downs. Seeing the beautiful sheep country still extending to the south, he determined to explore it to learn if there were any good water courses. Taking a pack horse with rations, he started on a S.W. course until he found a large river running in a southerly direction. A few miles further north the river runs from west to east. He marked a tree with his initial C., and this was found long afterwards to be on a water-hole between Kynuna and Dagworth. He expected to realise money on his exploration, but the Diamantina country was, as I have previously remarked, occupied by people coming from the Central district. The route from Townsville through long stretches of dry country was out of the running.

In after years Courtney took to drink. Finally, after one of his bouts, on leaving Normanton in an intoxicated condition, he camped at a water-hole 10 miles out. His clothes were found, but not the body. It was supposed that he had gone in for a swim, and that alligators, which swarm in these holes, had taken him. I could not learn if he had given any information as to the country, but I have no reason to doubt his statements.

[28]After my return to Clifton, I was kept busy preparing for lambing. This did not turn out very successful. The hot, scorching sun so scalded the backs of the lambs, that the growth of wool was greatly retarded.

After a month's hard work, I found myself so weak and depressed from the fever that I decided to return to England. In the meantime, Carruthers had left for his station on the Auburn River.

I was relieved in mind, by a letter from my uncle, who informed me that my request for a salary of £300 a year was exorbitant, and that he was sending a Mr. Hawkes to take the station over from me.

Soon after I was pleased to welcome this gentleman, and left for inside with a young fellow named Carolan, who had been working on Canobie. My uncle visited Clifton late in 1867, and decided to have the sheep boiled down at the works owned by Mr. Harry Edkins, on the Albert River.

During his stay at Burketown he became the guest of Mr. Surveyor Sharkey on Sweers Island, and met Miss Huey, sister of Mrs. Edkins, late of Mount Cornish Station, who became the second Mrs. Corfield. His first wife was a Miss Murray, sister of the highly-respected Police Magistrate, who died in Brisbane a few years ago, and also of the late Inspector Fred Murray. Her death on Teebar, in 1853, so affected my uncle that he sold the property for a nominal sum to his head stockman, John Eaton. He then took up and formed Gigoomgan, which he soon after sold to Anderson and Leslie. He afterwards bought Stanton Harcourt from W. H. Walsh, of Degilbo Station. There I joined him in 1862.

After handing the station over to Mr. Hawkes, I went to Canobie to muster my horses, which were running on the Williams River, and thence travelled eastward in company with Carolan.

On arrival at the Punch Bowl, on the Flinders River, we heard that there was a hundred mile dry stage ahead, so decided to camp.

One afternoon, Mr. Roland Edkins, later so long manager of Mount Cornish, and his wife, travelling on their honeymoon, drove up and asked if we had any meat we could spare. I informed him we had none, but that if he had a gun, and lent it to me, I would get some. A mob of cattle had been to the water-hole earlier in the day. Armed with his gun I followed the cattle and shot a clean-skin, which we dressed, and jerked in the sun, not having salt. The supply of meat was sufficient for all our needs. Mr. Edkins informed us that thunderstorms had fallen up the river, so we made a start. While camping in the bed of the river one night the water came down on us rather suddenly. We managed to get our belongings up the bank before they became wet.

In those days thunderstorms seemed to be more prevalent during November than in later years. Before we reached Telemon, the river was a banker, flooding the plains, and compelling us one night to camp on an ant bed, which was the only dry spot we could find. Fortunately, the ants were not of the bulldog breed.

We arrived at Telemon about noon of a sweltering hot day, and found Mr. Stewart, the owner, lying on his bunk with a tallow cask in close proximity, the grease oozing out on to his [30]bed. He invited us to have some dinner, and we gladly availed ourselves of the invitation. Learning that we were bound for the coast, he advised us to take the short cut up Bett's Gorge. Mr. Stewart had been adjutant of the Cameron Highlanders during the Crimean War, and was then considered to be the smartest officer in the regiment. When he came to Australia, and took up the runs of Southwick and Telemon, he altered so much that he became known as "Greasy Stewart." When spoken to about it, he would say, "When you are amongst savages, do as savages do." Otherwise he was in manners and conduct a gentleman, and a delightful conversationalist. When visiting Sydney he was considered to be a remarkably well-dressed man. He afterwards became the possessor of a large estate in Scotland, where he died.

We found the creek running through Bett's Gorge a banker, and had to swim 23 crossings in one day. Being so often in the water, we did not trouble to dress, consequently the sun played havoc with our bodies.

All the country for miles around being of a basaltic nature, our horses became very footsore, and when we reached Lolworth Station we asked Mr. Frank Hann, the manager, if he would allow us to spell them. He consented, and invited us to the house. We stayed there about three weeks, assisting him at mustering, and branding the cattle.

The Cape River diggings had just broken out, and as I was now getting stronger—the fever was going off gradually—I decided to remain in Australia, and try my hand at gold digging.

Both Carolan and myself were novices at the game, especially in putting down a shaft. We decided to go up on a spinifex ridge, out of sight, to sink, what turned out to be a three-cornered shaft, and so gain experience. This we bottomed at 100 feet, obtaining good specimens of shotty gold. Mr. Robert Christison, owner of Lammermoor Station, and Mr. Richard [31]Anning, from either Cargoon or Reedy Springs Stations (I forget which), arrived with two horses and a dray. They camped close to us, and like ourselves, intended trying their luck at gold digging.

Whilst working at this, one Sunday evening, we overheard some Chinamen speaking of a flat they were going to in the morning. We decided to watch, and follow them. At daylight they made a rush to peg out claims; we did likewise, and obtained one well placed as to water. The difficulty then was how to work both claims, and it was decided Carolan should get a mate and go on with the deep sinking on which we were working. I was to work the shallow one myself. Our first claim turned out to be on the edge of rich gold-bearing country, which was good while it lasted, but soon petered out. The surrounding claims turned out very rich, and got the name of the "Deep Lead."

In the meantime I had bottomed my shaft at eleven feet. It turned out to be a very wet one, so I had to work without my shirt. When I took the first dish down to wash, I noticed a number of men taking great interest in it, especially when the panning-out showed two dwts. of shotty gold in the dish. The men engaged me in conversation. When I returned to my claim, I found my pegs thrown away and fresh ones surrounding the shaft in place of them. I strongly demurred to this, but without avail, until a party of men who were our camp neighbours came over and took my part. Through them I recovered my claim without more than wordy warfare. After doing well out of the claim I found I could not continue it without a mate. Having to throw the wash-dirt eleven feet, a lot of the pebbles in it would come back on and bruise my naked body.

Carolan and his mate determined to sink another shaft in the deep sinking to hit the lead again. We had a consultation, and decided I should take in as partner an old miner known as "Greasy Bill," who possessed a horse and cart, cradles, and all the plant required for shallow sinking.

[32]For the first month we were getting as much as an ounce and a-half to the load of sixty buckets. As I puddled the wash-dirt he cradled it, and consequently was in possession of the gold bag which held the proceeds from the cradle. Although I could detect no difference in the wash-dirt, the cradling results dwindled down by degrees to a quarter ounce per load. As this did not pay our tucker bill, my mate suggested we should sink another shaft, which we bottomed, and it turned out with similar results. Carolan had now sunk his second shaft with no payable results, and as I was dissatisfied with the result of my new venture, we both decided to go prospecting. This we did, dry-blowing in the ranges with no payable results.

I afterwards met "Greasy Bill" at the Cape township, when he informed me that after I had left he had struck it rich in both claims. Others told me he had boasted he had got five hundred pounds out of the claim by abstracting the gold from the bag when I was not looking, and that the claim I pegged out was good throughout.

Our experiences as diggers had completely disgusted Carolan and me, so on hearing that carriage of loading to the gold field was very high, we determined to start as carriers.

I heard that a Mr. Mytton, of Oak Park Station, had a team of bullocks for sale, and having some money in the Savings Bank at ——, we decided to travel to Oak Park to investigate.

On reaching Craigie Station, on the Clarke River, to enquire the way, Mr. Saunders, the owner, informed us that he had seven bullocks and a dray for sale for £120, but I wished to purchase a full team of 12 or 16, such as Mr. Mytton had at Oak Park, and decided to go there. Mr. Saunders kindly lent us a Snider rifle for protection, as the blacks were bad through the ranges, between his station and Mytton's.

We camped the first night at the Broken River, a weird looking place. This was about May, 1868, and the nights [33]being very cold we would place one blanket under and have the other over us, with our heads on the saddle, and the rifle between us. During the night I was awakened by my saddle being pulled from my head. I immediately caught the rifle, and turning around saw a native dog dragging my saddle by one of the straps. Without waking my mate, who was a man six feet in height, I fired——. Carolan made one leap, taking the blanket with him, saying he was shot. This frightened me also. However, the howling of the dog who had apparently received the bullet through his body, and full explanations restored calm and a feeling of safety. In the morning we tracked the dog to the water-hole, where we found him dead.

On arrival at Oak Park, without further adventures, I found Mr. Mytton had leased his team of bullocks and waggon to a man named Jack Howell, who contemplated carrying. The latter was credited with being double-jointed, and I believe it. He was the strongest man I ever met. He afterwards married the widow of Jimmy Morrell, who had lived for seventeen years with the blacks in the Cleveland Bay district.

It is related that when he saw a white man after this length of time, Morrell jumped on a stock-yard fence, and called out, "Don't shoot, I'm a British object." The Government gave him a position in the Customs in Bowen, where he died a few years afterwards.

I later on attended Jack Howell's wedding. It was held in a house at the foot of Castle Hill, in Townsville. Some, uninvited, came up to tin-kettle the newly-married couple, but on Jack putting in an appearance they showed discretion and scampered away, leaving one of their mates hung up on a clothes line.

During our stay of three days at Oak Park, we received great kindness, which led to a life-long friendship with Edward Mytton. Carolan and I returned to Craigie Station to give back the borrowed rifle. I then decided to purchase [34]the seven bullocks and dray, giving Saunders a cheque for the price mentioned. I had to muster the bullocks myself, finding four of them the second day. Mr. Saunders said he would go out to find the remainder, as he knew where they were running. We both started, but in different directions. I found the tracks, and succeeded in bringing the bullocks to the yard, but Mr. Saunders did not turn up until the next evening, having been bushed on his own run. The bullocks were very fat, and had no leaders amongst them, so Mr. Saunders gave me a hand by leading my horse and driving the spare bullock. At every water-hole we came near these brutes would rush in, and I had to go, with my clothes on, after them. Carolan had left me at Craigie, and gone on to a public house at Nulla-Nulla, on the main Flinders road from Townsville. He bought in shares with a teamster, who had two teams, and as there was good grass and water, there he decided to camp. Here I met "Black Jack," who said he was the first white man to cross the Burdekin. Carolan having come out to give me a hand, Mr. Saunders returned to Craigie.

There were several carriers camped at Nulla, amongst them being a man named James Wilson, from whom I bought five bullocks. One of these was a good near-side leader, for which I was grateful. From that time Wilson and I became travelling mates. We loaded in Townsville for the Cape River diggings at twenty pounds per ton.

As my additional bullocks allowed me to put on three tons, the sixty pounds for carriage enabled me to pay for the bullocks and supplies for the trip. When I returned to Townsville I met Mr. Saunders, who had sold me the bullocks. He informed me that my cheque for payment had been dishonoured, marked "no account." This news was a staggerer. I explained that I had an account in the Government Savings Bank at ——, and that before I left the Cloncurry, I had sent my pass book and a receipted order to the Savings Bank officer, asking him to withdraw the money and place it to my credit in the local [35]branch of the A.J.S. Bank. Also that I had advised the bank of the prospective remittance, and following my request, had received a cheque book. Mr. Saunders was good enough to accept my explanation, and agreed to remain in Townsville while I proceeded to ——. I had very little money, so took a steerage passage in the old "Tinonee," which was conveying a large number of disappointed diggers returning to New Zealand. It was a rough and uncomfortable trip. One had to stand at the door and snap the food as it was carried to the table, not to do so meant going without. On arriving at ——, I put up at a boarding house, which was far from being first class. I called on the Postmaster, and told him my name. When he heard it he became very pale, and agitated, and showed great uneasiness. He invited me into his office, where I stated my business, and added that if my money was not forthcoming at once I would report him. He then told me that he was so long without hearing of me, that he was confirmed in believing the rumour of my death on the way in, and that he had invested the money in some land, which gave promise of soon rising in value. I gave him until the next boat was leaving for Townsville, which would be in four days, to repay the money. I also insisted upon being refunded my expenses, and a return saloon fare from Townsville to —— and back. He gladly agreed to my terms, and I promised not to proceed further. I had a splendid trip back per saloon. I met Mr. Saunders, who was pleased that I had recovered the money, and remarked, "I thought you had an honest face," etc. He added that he would give me preference for loading to the station.

This affair was brought back forcibly to my memory owing to the matter having been mentioned not long since by a friend of later years, who, in his capacity as a Government officer, happened to be stationed in this town some 30 years ago. He told me of a property bought by the Postmaster of the place, upon which there was a fine orchard. This was looked after by a German of gigantic stature, who patrolled the orchard [36]with a loaded shot gun. He said that an old resident of the place had told him that the property had been bought with money drawn from the Government Savings Bank by a man out in the Gulf country, who was reported to have died on the road down, but who turned up some months afterwards, and claimed his money. I did not at any time speak of the matter, and can only conclude that the Postmaster raised the money in the town, and gave the information to the lender. It was peculiar that my friend, fifty years afterwards, should mention a matter in which I was so concerned and without having any previous knowledge that I was the reported dead man.

The late Hon. B. Fahey, M.L.C., was then second officer of Customs in Townsville. He allowed me to see the ship's manifests of cargo arriving. I was thus enabled to apply beforehand for loading to these merchants who would be receiving consignments. This was a great help to my mate—Wilson—and myself to obtain loading quickly.

When carrying became slack, Mr. Marsh, of Webster and Marsh, of Mackay, arrived in Townsville, and being an old school-fellow of mine, said he would send up two loads from Mackay to keep me going.

About this time (1869), I made the acquaintance of Messrs. Watson Bros., of Townsville, who were very kind to me, inviting me to their house to spend the evenings when in the Bay (as Townsville was then generally spoken of). They had two sisters, one of whom afterwards married my friend Edward Mytton, and the other, Mr. Page, in after years of Wandovale Station. They were a cultured family, and the time I spent with them reminded me of home life more than anything I had then experienced since I left England.

On my last trip to the Cape diggings, Wilson and I had returned as far as Homestead, when Bob Watson rode up, and enquired for what we would take loading to the Gilbert River. We knew this place to be somewhere beyond Oak Park, and[37] we asked for £30 per ton. This was agreed to, with the proviso that the teams were to be loaded at night on the Lower Cape. At the time the township was honeycombed with shafts, and we had many misadventures driving our teams in the dark. Watson explained the reason for our loading at night was that the Gilbert diggings had only just been reported, and his firm wished to get supplies on the ground early to obtain high prices. We were to travel via the Upper Cape, Lolworth, Craigie, Wandovale, Junction Creek. Lyndhurst, and Oak Park, etc.

Long before we reached the latter place droves of people of both sexes, in all sorts of vehicles, on horse back, and afoot, passed us. The news had quickly spread that good gold had been found on the Gilbert.

This move of the Watson's was rather smart. They had a quantity of damaged flour to get rid of. We had to purchase our rations from them. The only way in which we could use the flour was to make it into johnny cakes, and eat them hot. Flour was selling at 3/- for half-a-pint, and the damaged flour soon found ready customers at fancy prices.

The township consisted of tents, but as the storekeepers required something more substantial than calico, I sold my tarpaulin for a good price, and made contracts to supply bark at 5/- per sheet. We engaged men to strip the bark. This work kept us both busy hauling with our teams, and lasted until the wants of the township were fully supplied.

We then started on our 350-mile journey back to Townsville, and reached there about the end of September. Mr. Mytton arranged for me to load for him, and I obtained a load for my mate for Lyndhurst, the station adjoining.

This station was managed by a Mr. Smith from the Clarence River. For some reason, I could not learn how, he was known as "Gentle J——." He was a remarkably small man, but was noted as being a very plucky one. His store was stuck-up[38] by a man called "Waddy Mundoo-i," from his having a wooden leg. Smith fought and knocked him out, afterwards giving him help to get along the road. We spent about a fortnight in Townsville having repairs made to the drays, etc., and we started on our return journey to Oak Park on the 14th of November, 1869, making as much haste as possible before the wet season set in. This, however, caught us at the Broken River, where we had to camp for over nine weeks. We were joined here by many other teams loaded for the Gilbert.

With us we had an old ship's carpenter, who helped to make a canoe from a currajong tree. On the stern he attached a board, on which was painted "Cleopatra, Glasgow." This boat proved very useful in ferrying over the large number of footmen arriving daily, and saving our rations, as all travellers expected to be fed without payment. One day we ferried Inspector Clohesy and his troopers across the river, which at the time was running very high. After a great deal of difficulty and some danger, we landed them and 2,000 ounces of gold in safety. Before the river was crossable for teams, I cut my name on a tree, bearing date 1870, which I again saw many years later. On arrival, we were warmly welcomed at the station.

When in Townsville I had asked Fitzmaurice, who had reached there from Peak Downs and was going to Sydney for a spell, to get a waggon made for me below. I now decided to turn out my bullocks at Oak Park to spell, and take on stock riding and droving fat bullocks into the diggings, where Mr. Mytton, having taken a partner named John Childs to look after the station during his absence, had opened a shop, and was butchering himself. Mr. Childs was married and had one little girl, named Beatrice, now married to one of our greatest sheep-owners.

Amongst those who camped a night at the Broken River was a young new-chum Irishman, who asked if we knew a man in "Australia" called Tom Ripley. We replied "Yes, he is [39]now at the Gilbert with his teams." He said, "I am his brother; he has bullock cars, hasn't he?" This remark, simple as it was, a long standing joke among the carriers.

In conversation we gleaned that he had left Ireland on the same day that we had left Townsville, had crossed the ocean, and was passing us bound for nearly the same destination as ourselves.

As two hundred and fifty miles is to thirteen thousand, so was the speed of bullock teams attempting travelling during the wet season to that of a sailing ship from the foggy seas.

My mate, Jim Wilson, returned to Townsville after delivering his load at Lyndhurst. Mr. Mytton had purchased Junction Creek Station (afterwards called Wandovale), from Mr. Cudmore, and had left the Gilbert to take delivery, intending afterwards to go on to Townsville to be married to Miss Watson. As the station was short-handed, and Mr. Mytton wished to make some alterations to prepare for his bride, he asked me if I would stay and use my team to bring in the timber, and also to assist Childs with the cattle. I consented to remain for a couple of months. During this time the black boys on the station bolted, taking with them Mrs Childs' gin, and my black boy. A carpenter named Jack Barker and myself started with three horses in pursuit, eventually finding the absconders where the Woolgar diggings now are. On our return we ran out of rations, and lived on iguanas, snakes, opossums, etc. Childs induced me to take charge of a mob of bullocks, and drove them to Wandovale, where Mr. and Mrs. Mytton were now living.

After delivering the bullocks at Wandovale, I returned to Oak Park to muster my bullocks and horses, and found a bay mare missing. Although assisted by the stockmen, we failed to find her. I then determined to start for Townsville, and again take up carrying. When I reached Wandovale on my way down, I camped at the station. Returning from putting my bullocks on grass, I saw a number of Chinamen with pack horses preparing to camp at the creek. One of their horses attracted my attention, so I rode over and recognised my mare. I rode on, and watched the direction in which the Chinamen hobbled their horses. Mr. Mytton and I then decided that [41]I should go out before daybreak to bring the mare in. He was to be at the slip rails to allow the animal to be driven into the paddock. In the dark of the early morning I had a difficulty in locating the animal amongst so many horses. Eventually, I found her, but I could not catch her. At daybreak I saw she was long hobbled, and getting near enough, struck her with the bridle, I turned her towards the station. The Chinamen were just starting out for their horses, and seeing me, tried to cut me off, and then ensued a race for the slip rails. I had half-a-mile to go to reach the paddock; however, putting on a spurt, I succeeded in reaching the slip rails first, hunting the mare through them, but I was completely winded. In response to the Chinamen's "Wha for," Mr. Mytton said he was a Justice of the Peace, and dared them to interfere with anything on his property. It ended by my giving my name and address, after stating that the mare was my property, and had been stolen from Oak Park Station.

Some time afterwards Inspector Clohesy, who was in charge of the police on the Gilbert, informed me that the Chinamen had come to him for redress, but he remembered how I had helped him and his escort across the Broken River, and assured them that he knew I would not have taken such action unless the mare was my property. The matter ended, and I found out afterwards the mare had been stolen and sold to the Chinamen.

Mention of Inspector Clohesy reminds me that he was a remarkable personality, now-a-days not so common—tall, slight and wiry, he could sit a horse as well as the best of riders and hold his own with men of all sorts. Endowed with quick insight into the character of men who were in many instances indifferent to law, he exercised a restraining influence without in any way neglecting his duty as a police officer. His presence and word alone frequently calmed excited diggers in a way that commanded their respect and admiration. When the diggers broke into rioting at Charters Towers, the tact, patience and courage of Clohesy was of more use and value than a posse[42] of police. Many a time I have heard a witty remark, or a pithy Irish phrase from him, turn a likely disturbance into a pleasant laughing meeting. Wherever he controlled, he kept things in order without his hand being felt. When he died about 1879, Queensland lost a good officer, and many a northern pioneer a true friend.

When I reached Townsville I procured a load for Ravenswood diggings, which had just been opened. I went to load my new waggon at Clifton and Aplin's store, accompanied by a man named Tom Hobbs, who was also loading at the same place, and for the same destination. When I drove my team and new waggon from Sydney through the streets toward the German Gardens—since the war, Belgium Gardens—where we were camped, I noticed every one laughing as I went by. After crossing the ridge where the Anglican Cathedral now stands, I went around to the off side, and there saw that some wag, while I was loading, had obliterated a letter on the name of my waggon, which Fitzmaurice had christened the "Townsville Lass." Striking the "L" out gave it a different name. I quickly procured a paint brush and renewed the name as it should be.

At that time the road to Ravenswood was lined with vehicles and pedestrians, making their way to the new field. Cobb and Co. were running a coach for mails and passengers, driven by Mick Brady, who afterwards was well and favourably known on the very bad road from Cooktown to Maytown. After making a quick trip we returned, and loaded again for the Gilbert diggings.

In going up Thornton's Gap, on the coast range, I had the misfortune to lose the top of my third finger on my right hand. We had 36 bullocks on the waggon, and a faulty chain breaking, only six bullocks were left to hold the waggon. The near side ones being lazy, allowed the waggon to drift down towards the steep descent of 500 feet to the bottom. I ran with a piece of heavy log to prevent a smash, but the wheels caught the log[43] before I could release my hand, and completely crushed the top of my finger until the bone protruded. That night I had to lay with my finger in hot water to relieve the pain. The next day I started at daylight for Townsville, had the finger dressed by the doctor, and returned to the teams the same day, having ridden a distance of 60 miles. I was unable to yoke my team, but this my mate, Tom Hobbs, kindly did for me. I was, however, able to drive the team the 350 miles to the Gilbert. On returning from there, I had a bad attack of fever and ague, which compelled me to ride on to Townsville for medical advice, having various difficulties on the way down. I left my black boy to assist my mate to bring down the two teams, by hitching my waggon behind his, and yoking up sufficient bullocks drafted from each team to draw them.

My mate, Tom Hobbs, was a "white man," which means a lot, but rather backward as regards education. In leisure moments I would assist him in reading, writing, etc. Before he left the Bay on this trip, he had become engaged to a young lady in the town, and enlisted my services to write his letters for him. I remember the last I wrote before leaving him contained the following:—

In a few weeks after reaching Townsville, under the doctor's care, I regained my usual good health, and found Tom's fiancee and delivered the messages which he had entrusted me with. The wet season of 1871 had set in, and Tom was stuck at the Burdekin River with the teams, so I concocted the following rhyme to send him as if they came from his lady-love:—

When I last visited Townsville in 1917, I called on Mrs. Hobbs, who showed me the original of the above, still in good preservation.

Tom was a very shy man, and asked me if I could arrange for his marriage to be held by the Registrar at the Court House on a Sunday evening. This I did, the wedding party arriving at the Court House by different routes to avoid publicity. The Registrar had only a candle, which did not give sufficient light, so he asked if I could obtain a lamp. I went down the hill to Evans', afterwards Enright's, Tattersall Hotel, and borrowed a lamp ostensibly to look for lost jewellery for a lady. Several loungers, doubting the reason given, followed me, with the result that at midnight Tom's house was surrounded by uninvited guests, and I had to hand out some bottles of brandy before they could be induced to leave. We kept things up until daylight, when I rode back to my camp at Mount Louisa, six miles away.

About this time the carriers were challenged by the Townsville cricket club to a match, to be played on a ground prepared at the German Gardens. A carrier named Billy Yates took his [45]waggon, decorated with boughs and bush flowers, drawn by bullocks, to bring out the town team. The principal bowler for Townsville was L. F. Sachs, of the A.J.S. Bank. Ours were Charlie and Fred Hannaford. After a hard-fought game of two innings each, the carriers won, I having the honour of being top scorer. The particulars did not go into print, so I am unable to give the details, although I remember the happenings connected with and after the match were interesting.

I was loaded at Mount Louisa on my way to Ravenswood, when, during the night a man wakened me, and asked if I could give him a drink. I gave him a nip of rum from the jar. Shortly afterwards I noticed the smell of burning, and on looking round saw a dray with a load of wool well alight. I immediately raised the alarm, and the men from several other teams who were camped there ran over, but all that we could save were the bullock yokes. We then tipped the dray up, thinking the ropes had been burnt through, and that the bales of wool would roll off, when we could deal with them. This was not the case, and the wind getting underneath so fanned the flame that soon the wool was burning as fiercely as the wood. The police investigated the matter, and found that the man I gave the drink to had travelled down with this team, and had a grievance about the payment of his wages. The Police Magistrate committed him to the Supreme Court for trial for arson. I was subpoenaed as principal witness, and had to ride back some 70 miles to give evidence. The jury found the man guilty, and he was sentenced to two years' hard labour. As he was leaving the Court, in passing me, he said, "You have only two years to live," but in this he did not prove a true prophet.

About this time I first made the acquaintance of the gentleman now known as Sir Robert Philp. He has a reputation throughout this country, to which, if I attempted to add anything would be simply gilding refined gold. But in 1870 the name of Bob Philp, accountant for James Burns, was throughout North Queensland a synonym for business ability, integrity[46] of character, and kindness of heart. This reputation has not been dimmed by the passing of years. It is something of a pleasure to know Sir Robt. Philp, but it is a matter of pride to have known Mr. Philp "Lang Syne," when men of ability, character, and generosity were not rare or difficult to find.

I have alluded several times to "partners," or "mates," which was the more popular term. These partnerships were quite common amongst carriers and diggers in bygone days. It was simply chums, owning and sharing everything in common, and without any agreement, written or otherwise. There were many such partnerships involving large sums of money and valuable property which existed only on a complete trust in mates.

Among others on the Gilbert and Etheridge, were the mateship of Steel, Hunt and O'Brien. There were several such partnerships on the Palmer, notably that of Duff, Edwards and Callaghan. Of the high characters and generosity of all these men many interesting stories could be told. I doubt if their prototypes now exist. In my own case, in carrying and in business, I carried on with partners for many years without any agreement. The partnerships were based on mutual trust. When it was felt between the partners for some reason or other—generally a mere liking for a change—that the partnership might end, a friendly squaring-up would take place; each would go his own way and probably enter into partnership with some other party. With the exception of the partner I had in a claim on the Cape goldfield, I found all my mates or partners to be men in every sense of the term.

I had a very good black boy, a little fellow of about 10 years of age, a native of Cooper's Creek, whom I called Billy. On one of my trips to the Gilbert, when passing Dalrymple, Billy Marks, the store and hotel-keeper, presented me with a well-bred cattle pup and a gin case to put him in. This I placed on top of the load. We had six miles to go over very rough basalt country [47]to our camp. That day I had yoked a steer for the first time, and I intended to hobble him at night. When we reached camp I told Billy to bring up a quiet bullock called Darling, and this I coupled to the steer, instructing the boy to hold the whip-stick in front of the steer to attract his attention whilst I hobbled him. I had just put the hobble on the off leg, and was preparing to put it on the other, when the steer gave a tremendous jump, and the old bullock knocked me on my back on the yokes lying on the ground. When I rose I looked at the boy to see if he was laughing, but he was quite demure. I then saw the pup on the ground. He had caused my discomfiture by jumping on the steer's back, the box having broken open coming over the stones. When I returned from putting the bullocks on the grass, I saw my mate laughing, and to my inquiry he replied: "When you left with the bullocks I inquired from the boy what the trouble was?" The boy said, "Puppy been jump down on the steer's back, and old Darling been throw 'em a good way." My mate said, "You been laugh?" The boy answered, "Baal! me only been laugh alonga inside." He thought I might have beaten him if I had detected a smile on his face. While I was camped just outside Dalrymple, I one day told the boy if anyone wanted me, to say I was in the township. I had just finished a game of billiards at the hotel, when a man entered laughing. He called me on one side, and said he had asked my boy where I was. He said "That fella along public house playing—he got 'em spear in his hand, and knock about things all a same like it duck egg." He added the boy had followed me and watched my actions.

I continued carrying to Ravenswood, Charters Towers, the Gilbert and Etheridge goldfields until October, 1872, when I loaded for the latter place, delivering my load towards the end of the year, and just as the wet season set in. My travelling mate at this time was Billy Wilson, and he, wishing to return to port, left me in charge of his team. I camped on the Delaney River, and as there was abundance of grass, the bullocks gave no trouble. On Wilson's return, we decided to purchase two loads of stores from Clifton and Aplin's branch store, to take to the Palmer River rush which had just broken out, owing to William Hann's report on his exploration through the Peninsula becoming known.

William Hann was a first-class bushman, but it is quite evident he was very much astray in one portion of the trip, which led to the great gold discovery. On page 13 of his report, referring to his following up the Normanby River, he stated he crossed the divide between the Normanby and Endeavour Rivers, and followed a gully for nine and a-half miles; ... when it became a considerable creek which he called Oakey Creek, it being the first place he saw the familiar oaks. Under date 21st September, 1872, he reports:—"Running this creek down in an easterly direction, and being compelled to cross it several times until it junctioned with a large river running north and south"; he adds "this river was, of course, no other than the Endeavour, of which so much has been said and heard from time to time." In this assumption he was far out. Owing to the rough country, Oakey Creek had to be crossed three times, and while being only one creek its crossings were afterwards known as Big, Middle and Little Oakey. The creek forms one[49]of the heads of the Annan River, so named by Dalrymple. This river coming from the south-east falls into the sea some miles south of Mount Cook, which, with its spurs, divides it from the estuary of the Endeavour. Although there was a qualified surveyor in the party, it does not appear that he put Hann right. I do not mention this with any other desire than to show what difficulties our early explorers met with.

The manner in which Hann extricated his party from the terrible rough country at the heads of the Bloomfield and Daintree Rivers stamps him as a fine bushman, resourceful and dauntless.

We had a very exciting trip passing Fossilbrook, Mount Surprise, and Firth's Stations, crossing the Lynd, Tate, Walsh and Mitchell Rivers. These were all running strong. When we arrived at the Walsh, two horse teams had been camped there for a fortnight, and the owners told us the river was uncrossable. After putting the bullocks on grass, my mate (who was a splendid bushman), rode into the river. The water being clear, he was able to zig-zag a sand bank, avoiding deep water, and found we could get the waggons across by putting the goods on the guard rails. This we did that night unknown to the owners of the other teams who were camped farther on, but out of sight. In the morning we yoked up, and passed them, stating we were going to attempt crossing. This they declared was impossible, but came down to see us make the attempt. We only had our shirts on, and rode our horses bare-back. We made the crossing successfully, and camped on the northern bank. The river came down again that night, and delayed the horse teams another week. When we reached the Mitchell River, we found there were forty teams of all sorts and sizes waiting to cross. The next day my mate said that the river was fordable, and he would cross. We led the way, followed by the others. Quite a little village of people of both sexes camped that night on the north side of the Mitchell. Our troubles were now over, and we had thirty miles of easy travelling, past Mount Mulgrave to the Palmer River.

[50]There was such a quantity of stores arriving at the one time that we could not dispose of ours, so it was arranged that Wilson should take his team to Cooktown, and purchase a load jointly for us, and that I should remain, put up a tarpaulin store for the goods, and dispose of them as opportunity offered. To do this I decided to sell my bullock team and horses, as I did not know how long I should remain.

In the meantime, another diggings called Purdie's Camp broke out forty miles up the river, so I purchased some more stores and engaged a horse team to carry all the goods there at £40 per ton. The only grass on the road was that known as "turpentine." This the horses would not eat, consequently we had to feed them on flour and water. On arrival, I disposed of everything at high prices. Thus flour, 200lb. bag for £20, and other things at like values.

When at Purdie's camp, a packer—that is, a carrier using pack horses—came in with his horses, one of which had thrown his shoe. This rendered the horse useless to travel over the stony ridges. The packer wanted horse-shoe nails, so, as a joke, a carrier named Billy Yates offered to let him have five horse-shoe nails for their weight in gold. The offer was accepted, and I saw the nails put in one scale and the gold in the other. The packer was receiving one shilling per pound for packing goods eleven miles, and on that day's trip the horse took 150lbs., thus giving him £7/10/-, less the price for the nails. I forget the value of the gold paid for the latter.