Cover based on an image generated by Microsoft Bing

An ebook published by

Project Gutenberg Australia

Guns of the Gods:

Talbot Mundy:

eBook No.: fr100305.html

Language: English

Date first posted: Dec 2012

Most recent update: May 2023

This eBook was produced by Roy Glashan and Colin Choat

Cover based on an image generated by Microsoft Bing

Adventure, 3 Mar 1921, with first part of "The Winds of the World"

"Guns of the Gods," Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis, 1921

"Guns of the Gods," Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis, 1921

"Guns of the Gods," Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis, 1921

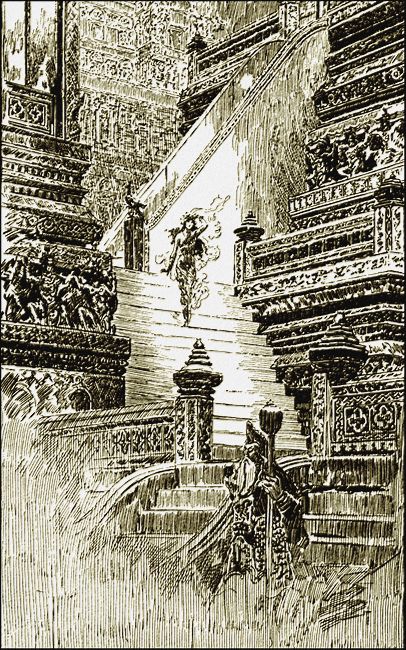

Headpiece from "Adventure"

At the top of the stairs Yasmini stood waiting.

Old Troy reaped rue in the womb of years

For stolen Helen's sake;

Till tenfold retribution rears

Its wreck on embers slaked with tears

That mended no heart-ache.

The wail of the women sold as slaves

Lest Troy breed sons again

Dreed o'er a desert of nameless graves,

The heaps and the hills that are Trojan graves

Deep-runneled by the rain.

But Troy lives on.

Though Helen's rape

And ten-year hold were vain;

Though jealous gods with men conspire

And Furies blast the Grecian fire;

Yet Troy must rise again.

Troy's daughters were a spoil and sport,

Were limbs for a labor gang,

Who crooned by foreign loom and mill

Of Trojan loves they cherished still,

Till Homer heard, and sang,

They told, by the fire when feasters roared

And minstrels waited turns,

Of the might of the men that Troy adored,

Of the valor in vain of the Trojan sword,

With the love that slakeless burns,

That caught and blazed in the minstrel mind

Or ever the age of pen.

So maids and a minstrel rebuilt Troy,

Out of the ashes they rebuilt Troy

To live in the hearts of men.

—Out of the Ashes

THE why and wherefore of my privilege to write a true account of the Princess Yasmini's early youth is a story in itself too long to tell here; but it came about through no peculiar wisdom. I fell in a sort of way in love with her, and that led to opportunity.

She never made any secret of the scorn with which she regards those who singe wings at her flame. Rather she boasts of it with limit-overreaching epithets. Her respect is reserved for those rare men and women who can meet her in unfair fight and, if not defeat her, then come close to it. She asks no concessions on account of sex. Men's passions are but weapons forged for her necessity; and as for genuine love-affairs, like Cleopatra, she had but two, and the second ended in disaster to herself. This tale is of the first one that succeeded, although fraught with discontent for certain others.

The second affair came close to whelming thrones, and I wrote of that in another book with an understanding due, as I have said, to opportunity, and with a measure of respect that pleased her.

She is habitually prompt and generous with her rewards, if far-seeing in bestowal of them. So, during the days of her short political eclipse that followed in a palace that had housed a hundred kings, I saw her almost daily in a room—her holy of holies—where the gods of ancient India were depicted in three primal colors working miracles all over the walls and where, if governments had only known it, she was already again devising plans to set the world on fire.

There, amid an atmosphere of Indian scents and cigarette smoke, she talked and I made endless notes, while now and then, when she was meditative, her maids sang to an accompaniment of rather melancholy wooden flutes. But whenever I showed a tendency to muse she grew indignant.

"Of what mud are you building castles now? Set down my thoughts not yours," she insisted, "if your tale is to be worth the pesa."

By that she referred to the custom of all Eastern story-tellers to stop at the exciting moment and take up a collection of the country's smallest copper coins before finishing the tale. But the reference was double-edged. A penny for my thoughts, a penny for the West's interpretation of the East was what she had in mind.

Nevertheless, as it is to the West that the story must appeal it has seemed wiser to remove it from her lips and so transpose that, though it loses in lore unfortunately, it does gain something of directness and simplicity. Her satire, and most of her metaphor if always set down as she phrased it, would scandalize as well as puzzle Western ears.

This tale is of her youth, but Yasmini's years have not yet done more than ripen her. In a land where most women shrivel into early age she continues, somewhere perhaps a little after thirty, in the bloom of health and loveliness, younger in looks and energy than many a Western girl of twenty-five. For she is of the East and West, very terribly endowed with all the charms of either and the brains of both.

Her quick wit can detect or invent mercurial Asian subterfuge as swiftly as appraise the rather glacial drift of Western thought; and the wisdom of both East and West combines in her to teach a very nearly total incredulity in human virtue. Western morals she regards as humbug, neither more nor less.

In virtue itself she believes, as astronomers for example believe in the precession of the equinox; but that the rank and file of human beings, and especially learned human beings, have attained to the very vaguest understanding of it she scornfully disbelieves. And with a frankness simply Gallic in its freedom from those thought-conventions with which so many people like to deceive themselves she deals with human nature on what she considers are its merits. The result is sometimes very disconcerting to the pompous and all the rest of the host of self-deceived, but usually amusing to herself and often profitable to her friends.

Her ancestry is worth considering, since to that she doubtless owes a good proportion of her beauty and ability. On her father's side she is Rajput, tracing her lineage so far back that it becomes lost at last in fabulous legends of the Moon (who is masculine, by the way, in Indian mythology). All of the great families of Rajputana are her kin, and all the chivalry and derring-do of that royal land of heroines and heroes is part of her conscious heritage.

Her mother was Russian. On that side, too, she can claim blood royal, not devoid of at least a trace of Scandinavian, betrayed by glittering golden hair and eyes that are sometimes the color of sky seen over Himalayan peaks, sometimes of the deep lake water in the valleys. But very often her eyes seem so full of fire and their color is so baffling that a legend has gained currency to the effect that she can change their hue at will.

How a Russian princess came to marry a Rajput king is easier to understand if one recalls the sinister designs of Russian statecraft in the days when India and "warm sea-water" was the great objective. The oldest, and surely the easiest, means of a perplexed diplomacy has been to send a woman to undermine the policy of courts or steal the very consciences of kings. Delilah is a case in point. And in India, where the veil and the rustling curtain and religion hide woman's hand without in the least suppressing her, that was a plan too easy of contrivance to be overlooked.

In those days there was a prince in Moscow whose public conduct so embittered his young wife, and so notoriously, that when he was found one morning murdered in his bed suspicion rested upon her. She was tried in secret, as the custom was, found guilty and condemned to death. Then, on the strength of influence too strong for the czar, the sentence was commuted to the far more cruel one of life imprisonment in the Siberian mines. While she awaited the dreaded march across Asia in chains a certain proposal was made to the Princess Sonia Omanoff, and no one who knew anything about it wondered that she accepted without much hesitation.

Less than a month after her arrest she was already in Paris, squandering paper rubles in the fashionable shops. And at the Russian Embassy in Paris she made the acquaintance of the very first of the smaller Indian potentates who made the "grand tour." Traveling abroad has since become rather fashionable, and is even encouraged by the British-Indian Government because there is no longer any plausible means of preventing it; but Maharajah Bubru Singh was a pioneer, who dared greatly, and had his way even against the objections of a high commissioner. In addition he had had to defy the Brahmin priests who, all unwilling, are the strong supports of alien overrule; for they are armed with the iron-fanged laws of caste that forbid crossing the sea, among innumerable other things.

Perhaps there was a hint of moral bravery behind the warrior eyes that was enough in itself and she really fell in love at first sight, as men said. But the secret police of Russia were at her elbow, too, hinting that only one course could save her from extradition and Siberian mines. At any rate she listened to the Rajah's wooing; and the knowledge that he had a wife at home already, a little past her prime perhaps and therefore handicapped in case of rivalry, but never-the-less a prior wife, seems to have given her no pause. The fact that the first wife was childless doubtless influenced Bubru Singh.

They even say she was so far beside herself with love for him that she would have been satisfied with the Gandharva marriage ceremony sung by so many Rajput poets, that amounts to little more than going off alone together. But the Russian diplomatic scheme included provision for the Maharajah of a wife so irrevocably wedded that the British would not be able to refuse her recognition. So they were married in the presence of seven witnesses in the Russian Embassy, as the records testify.

After that, whatever its suspicions, the British Government had to admit her into Rajputana. And what politics she might have played, whether the Russian gray-coat armies might have encroached into those historic hills on the strength of her intriguing, or whether she would have seized the first opportunity to avenge herself by playing Russia false,—are matters known only to the gods of unaccomplished things. For Bubru Singh, her Maharajah, died of an accident very shortly after the birth of their child Yasmini.

Now law is law, and Sonia Omanoff, then legally the Princess Sonia Singh, had appealed from the first to Indian law and custom, so that the British might have felt justified in leaving her and her infant daughter to its most untender mercies. Then she would have been utterly under the heel of the succeeding prince, a nephew of her husband, unenamored of foreigners and avowedly determined to enforce on his uncle's widow the Indian custom of seclusion.

But the British took the charitable view, that covering a multitude of sins. It was not bad policy to convert the erstwhile Sonia Omanoff from secret enemy to grateful friend, and the feat was easy.

The new Maharajah, Gungadhura Singh, was prevailed on to assign an ancient palace for the Russian widow's use; and there, almost within sight of the royal seraglio from which she had been ousted, Yasmini had her bringing up, regaled by her mother with tales of Western outrage and ambition, and well schooled in all that pertained to her Eastern heritage by the thousand-and-one intriguers whose delight and livelihood it is to fish the troubled waters of the courts of minor kings.

All these things Yasmini told me in that scented chamber of another palace, in which a wrathful government secluded her in later years for its own peace as it thought, but for her own recuperation as it happened. She told me many other things besides that have some little bearing on this story but that, if all related, would crowd the book too full. The real gist of them is that she grew to love India with all her heart and India repaid her for it after its own fashion, which is manyfold and marvelous.

There is no fairer land on earth than that far northern slice of Rajputana, nor a people more endowed with legend and the consciousness of ancestry. They have a saying that every Rajput is a king's son, and every Rajputni worthy to be married to an emperor. It was in that atmosphere that Yasmini learned she must either use her wits or be outwitted, and women begin young to assert their genius in the East. But she outstripped precocity and, being Western too, rode rough-shod on convention when it suited her, reserving her concessions to it solely for occasions when those matched the hand she held. All her life she has had to play in a ruthless game, but the trump that she has learned to lead oftenest is unexpectedness. And now to the story.

There is a land where no resounding street

With babel of electric-garish night

And whir of endless wheels has put to flight

The liberty of leisure. Sandaled feet

And naked soles that feel the friendly dust

Go easily along the never measured miles.

A land at which the patron tourist smiles

Because of gods in whom those people trust

(He boasting One and trusting not at all);

A land where lightning is the lover's boon,

And honey oozing from an amber moon

Illumines footing on forbidden wall;

Where, 'stead of pursy jeweler's display,

Parading peacocks brave the passer-by,

And swans like angels in an azure sky

Wing swift and silent on unchallenged way.

No land of fable! Of the Hills I sing,

Whose royal women tread with conscious grace

The peace-filled gardens of a warrior race,

Each maiden fit for wedlock with a king,

And every Rajput son so royal born

And conscious of his age-long heritage

He looks askance at Burke's becrested page

And wonders at the new-ennobled scorn.

I sing (for this is earth) of hate and guile,

Of tyranny and trick and broken pledge,

Of sudden weapons, and the thrice-keen edge

Of woman's wit, the sting in woman's smile,

But also of the heaven-fathomed glow,

The sweetness and the charm and dear delight

Of loyal woman, humorous and right,

Pure-purposed as the bosom of the snow.

No tale, then, this of motors, but of men

With camels fleeter than the desert wind,

Who come and go. So leave the West behind,

And, at the magic summons of the pen

Forgetting new contentions if you will,

Take wings, take silent wings of time untied,

And see, with Fellow-friendship for your guide,

A little how the East goes wooing still.

—Royal Rajasthan

DAWN at the commencement of hot weather in the hills if not the loveliest of India's wealth of wonders (for there is the moon by night) is fair preparation for whatever cares to follow. There is a musical silence cut of which the first voices of the day have birth; and a half-light holding in its opalescence all the colors that the day shall use; a freshness and serenity to hint what might be if the sons of men were wise enough; and beauty unbelievable. The fortunate sleep on roofs or on verandas, to be ready for the sweet cool wind that moves in advance of the rising sun, caused, as some say, by the wing-beats of departing spirits of the night.

So that in that respect the mangy jackals, the monkeys, and the chandala (who are the lowest human caste of all and quite untouchable by the other people the creator made) are most to be envied; for there is no stuffy screen, and small convention, between them and enjoyment of the blessed air.

Next in order of defilement to the sweepers,—or, as some particularly righteous folk with inside reservations on the road to Heaven firmly insist, even beneath the sweepers, and possibly beneath the jackals —come the English, looking boldly on whatever their eyes desire and tasting out of curiosity the fruit of more than one forbidden tree, but obsessed by an amazing if perverted sense of duty. They rule the land, largely by what they idolize as "luck," which consists of tolerance for things they do not understand. Understanding one another rather well, they are more merciless to their own offenders than is Brahmin to chandala, for they will hardly let them live. But they are a people of destiny, and India has prospered under them.

In among the English something after the fashion of grace notes in the bars of music—enlivening, if sharp at times—come occasional Americans, turning up in unexpected places for unusual reasons, and remaining —because it is no man's business to interfere with them. Unlike the English, who approach all quarters through official doors and never trespass without authority, the Americans have an embarrassing way of choosing their own time and step, taking officialdom, so to speak, in flank. It is to the credit of the English that they overlook intrusion that they would punish fiercely if committed by unauthorized folk from home.

So when the Blaines, husband and wife, came to Sialpore in Rajputana without as much as one written introduction, nobody snubbed them. And when, by dint of nothing less than nerve nor more than ability to recognize their opportunity, they acquired the lease of the only vacant covetable house nobody was very jealous, especially when the Blaines proved hospitable.

It was a sweet little nest of a house with a cool stone roof, set in a rather large garden of its own on the shoulder of the steep hill that overlooks the city. A political dependent of Yasmini's father had built it as a haven for his favorite paramour when jealousy in his seraglio had made peace at home impossible. Being connected with the Treasury in some way, and suitably dishonest, he had been able to make a luxurious pleasaunce of it; and he had taste.

But when Yasmini's father died and his nephew Gungadhura succeeded him as maharajah he made a clean sweep of the old pension and employment list in order to enrich new friends, so the little nest on the hill became deserted. Its owner went into exile in a neighboring state and died there out of reach of the incoming politician who naturally wanted to begin business by exposing the scandalous remissness of his predecessor. The house was acquired on a falling market by a money-lender, who eventually leased it to the Blaines on an eighty per cent. basis—a price that satisfied them entirely until they learned later about local proportion.

The front veranda faced due east, raised above the garden by an eight-foot wall, an ideal place for sleep because of the unfailing morning breeze. The beds were set there side by side each evening, and Mrs. Blaine—a full ten years younger than her husband—formed a habit of rising in the dark and standing in her night-dress, with bare feet on the utmost edge of the top stone step, to watch for the miracle of morning. She was fabulously pretty like that, with her hair blowing and her young figure outlined through the linen; and she was sometimes unobserved.

The garden wall, a hundred feet beyond, was of rock, two-and-a-half men high, as they measure the unleapable in that distrustful land; but the Blaines, hailing from a country where a neighbor's dog and chickens have the run of twenty lawns, seldom took the trouble to lock the little, arched, iron-studded door through which the former owner had come and gone unobserved. The use of an open door is hardly trespass under the law of any land; and dawn is an excellent time for the impecunious who take thought of the lily how it grows in order to outdo Solomon.

When a house changes hands in Rajputana there pass with it, as well as the rats and cobras and the mongoose, those beggars who were wont to plague the former owner. That is a custom so based on ancient logic that the English, who appreciate conservatism, have not even tried to alter it.

So when a cracked voice broke the early stillness out of shadow where the garden wall shut off the nearer view, Theresa Blaine paid small attention to it.

"Memsahib! Protectress of the poor!"

She continued watching the mystery of coming light. The ancient city's domed and pointed roofs already glistened with pale gold, and a pearly mist wreathed the crowded quarter of the merchants. Beyond that the river, not more than fifty yards wide, flowed like molten sapphire between unseen banks. As the pale stars died, thin rays of liquid silver touched the surface of a lake to westward, seen through a rift between purple hills. The green of irrigation beyond the river to eastward shone like square-cut emeralds, and southward the desert took to itself all imaginable hues at once.

"Colorado!" she said then. "And Arizona! And Southern California! And something added that I can't just place!"

"Sin's added by the scow-load!" growled her husband from the farther bed. "Come back, Tess, and put some clothes on!"

She turned her head to smile, but did not move away. Hearing the man's voice, the owners of other voices piped up at once from the shadow, all together, croaking out of tune:

"Bhig mangi shahebi! Bhig mangi shahebi!"*

[* Alms! Alms!]

"I can see wild swans," said Theresa. "Come and look—five— six—seven of them, flying northward, oh, ever so high up!"

"Put some clothes on, Tess!"

"I'm plenty warm."

"Maybe. But there's some skate looking at you from the garden. What's the matter with your kimono?"

However the dawn wind was delicious, and the night-gown more decent than some of the affairs they label frocks. Besides, the East is used to more or less nakedness and thinks no evil of it, as women learn quicker than men.

"All right—in a minute."

"I'll bet there's a speculator charging 'em admission at the gate," grumbled Dick Blaine, coming to stand beside her in pajamas. "Sure you're right, Tess; those are swans, and that's a dawn worth seeing."

He had the deep voice that the East attributes to manliness, and the muscular mold that never came of armchair criticism. She looked like a child beside him, though he was agile, athletic, wiry, not enormous.

"Sahib!" resumed the voices. "Sahib! Protector of the poor!" They whined out of darkness still, but the shadow was shortening.

"Better feed 'em, Tess. A man's starved down mighty near the knuckle if he'll wake up this early to beg."

"Nonsense. Those are three regular bums who look on us as their preserve. They enjoy the morning as much as we do. Begging's their way of telling people howdy."

"Somebody pays them to come," he grumbled, helping her into a pale blue kimono.

Tess laughed. "Sure! But it pays us too. They keep other bums away. I talk to them sometimes."

"In English?"

"I don't think they know any. I'm learning their language."

It was his turn to laugh. "I knew a man once who learned the Gypsy bolo on a bet. Before he'd half got it you couldn't shoo tramps off his door-step with a gun. After a time he grew to like it—flattered him, I suppose, but decent folk forgot to ask him to their corn-roasts. Careful, Tess, or Sialpore'll drop us from its dinner lists."

"Don't you believe it! They're crazy to learn American from me, and to hear your cowpuncher talk. We're social lions. I think they like us as much as we like them. Don't make that face, Dick, one maverick isn't a whole herd, and you can't afford to quarrel with the commissioner."

He chose to change the subject.

"What are your bums' names?" he asked.

"Funny names. Bimbu, Umra and Pinga. Now you can see them, look, the shadow's gone. Bimbu is the one with no front teeth, Umra has only one eye, and Pinga winks automatically. Wait till you see Pinga smile. It's diagonal instead of horizontal. Must have hurt his mouth in an accident."

"Probably he and Bimbu fought and found the biting tough. Speaking of dogs, strikes me we ought to keep a good big fierce one," be added suggestively.

"No, no, Dick; there's no danger. Besides, there's Chamu."

"The bums could make short work of that parasite."

"I'm safe enough. Tom Tripe usually looks in at least once a day when you're gone."

"Tom's a good fellow, but once a day—. A hundred things might happen. I'd better speak to Tom Tripe about those three bums—he'll shift them!"

"Don't, Dick! I tell you they keep others away. Look, here comes Chamu with the chota hazri."*

[* chota-hazri (Hindi, "little breakfast")]

Clad in an enormous turban and clean white linen from head to foot, a stout Hindu appeared, superintending a tall meek underling who carried the customary "little breakfast" of the country—fruit, biscuits and the inevitable tea that haunts all British byways. As soon as the underling had spread a cloth and arranged the cups and plates Chamu nudged him into the background and stood to receive praise undivided. The salaams done with and his own dismissal achieved with proper dignity, Chamu drove the hamal* away in front of him, and cuffed him the minute they were out of sight. There was a noise of repeated blows from around the corner.

[* hamal (Arabic)—a porter or bearer in certain Moslem countries.]

"A big dog might serve better after all," mused Tess. "Chamu beats the servants, and takes commissions, even from the beggars."

"How do you know?"

"They told me."

"Um, Bing and Ping would better keep away. There's no obligation to camp here."

"Only, if we fired Chamu I suppose the maharajah would be offended. He made such a great point of sending us a faithful servant."

"True. Gungadhura Singh is a suspicious rajah. He suspects me anyway. I screwed better terms out of him than the miller got from Bob White, and now whenever he sees me off the job he suspects me of chicanery. If we fired Chamu he'd think I'd found the gold and was trying to hide it. Say, if I don't find gold in his blamed hills eventually—!"

"You'll find it, Dick. You never failed at anything you really set your heart on. With your experience—"

"Experience doesn't count for much," he answered, blowing at his tea to cool it. "It's not like coal or manganese. Gold is where you find it. There are no rules."

"Finding it's your trade. Go ahead."

"I'm not afraid of that. What eats me," he said, standing up and looking down at her, "is what I've heard about their passion for revenge. Every one has the same story. If you disappoint them, gee whiz, look out! Poisoning your wife's a sample of what they'll do. It's crossed my mind a score of times, little girl, that you ought to go back to the States and wait there till I'm through—"

She stood on tiptoe and kissed him.

"Isn't that just like a man!"

"All the same—"

"Go in, Dick, and get dressed, or the sun will be too high before you get the gang started."

She took his arm and they went into the house together. Twenty minutes later he rode away on his pony, looking if possible even more of an athlete than in his pajamas, for there was an added suggestion of accomplishment in the rolled-up sleeves and scarred boots laced to the knee. Their leave-taking was a purely American episode, mixed of comradeship, affection and just plain foolishness, witnessed by more wondering, patient Indian eyes than they suspected. Every move that either of them made was always watched.

As a matter of fact Chamu's attention was almost entirely taken up just then by the crows, iniquitous black humorists that took advantage of turned backs (for Tess walked beside the pony to the gate) to rifle the remains of chota hazri, one of them flying off with a spoon since the rest had all the edibles. Chamu threw a cushion at the spoon-thief and called him "Balibuk," which means eater of the temple offerings, and is an insult beyond price.

"That's the habit of crows," he explained indignantly to Tess as she returned, laughing, to the veranda, picking up the cushion on her way. "They are without shame. Garuda, who is king of all the birds, should turn them into fish; then they could swim in water and be caught with hooks. But first Blaine sahib should shoot them with a shotgun."

Having offered that wise solution of the problem Chamu stood with fat hands folded on his stomach.

"The crows steal less than some people," Tess answered pointedly.

He preferred to ignore the remark.

"Or there might be poison added to some food, and the food left for them to see," he suggested, whereat she astonished him, American women being even more incomprehensible than their English cousins.

"If you talk to me about poison I'll send you back to Gungadhura in disgrace. Take away the breakfast things at once."

"That is the hamal's business," he retorted pompously. "The maharajah sahib is knowing me for most excellent butler. He himself has given me already very high recommendation. Will he permit opinions of other people to contradict him?"

The words "opinions of women" had trembled on his lips but intuition saved that day. It flashed across even his obscene mentality that he might suggest once too often contempt for Western folk who worked for Eastern potentates. It was true he regarded the difference between a contract and direct employment as merely a question of degree, and a quibble in any case, and he felt pretty sure that the Blaines would not risk the maharajah's unchancy friendship by dismissing himself; but he suspected there were limits. He could not imagine why, but he had noticed that insolence to Blaine himself was fairly safe, Blaine being super-humanly indifferent as long as Mrs. Blaine was shown respect, even exceeding the English in the absurd length to which he carried it. It was a mad world in Chamu's opinion. He went and fetched the hamal, who slunk through his task with the air of a condemned felon. Tess smiled at the man for encouragement, but Chamu's instant jealousy was so obvious that she regretted the mistake.

"Now call up the beggars and feed them," she ordered.

"Feed them? They will not eat. It is contrary to caste."

"Nonsense. They have no caste. Bring bread and feed them."

"There is no bread of the sort they will eat."

"I know exactly what you mean. If I give them bread there's no profit for you—they'll eat it all; but if I give them money you'll exact a commission from them of one pesa in five. Isn't that so? Go and bring the bread."

He decided to turn the set-back into at any rate a minor victory and went in person to the kitchen for chapatis such as the servants ate. Then, returning to the top of the steps he intimated that the earth-defilers might draw near and receive largesse, contriving the impression that it was by his sole favor the concession was obtained. Two of them came promptly and waited at the foot of the steps, smirking and changing attitudes to draw attention to their rags. Chamu tossed the bread to them with expressions of disgust. If they had cared to pretend they were holy men he would have been respectful, in degree at least, but these were professionals so hardened that they dared ignore the religious apology, which implies throughout the length and breadth of India the right to beg from place to place. These were not even true vagabonds, but rogues contented with one victim in one place as long as benevolence should last.

"Where is the third one?" Tess demanded. "Where is Pinga?"

They professed not to know, but she had seen all three squatting together close to the little gate five minutes before. She ordered Chamu to go and find the missing man and he waddled off, grumbling. At the end of five minutes he returned without him.

"One comes on horseback," he announced, "who gave the third beggar money, so that he now waits outside."

"What for?"

"Who knows? Perhaps to keep watch."

"To watch for what?"

"Who knows?"

"Who is it on horseback? A caller? Some one coming for breakfast? You'd better hurry."

The call at breakfast-time is one of the pleasantest informalities of life in India. It might even be the commissioner. Tess ran to make one of those swift changes of costume with which some women have the gift of gracing every opportunity. Chamu waddled down the steps to await with due formality, the individual, in no way resembling a British commissioner, who was leisurely dismounting at the wide gate fifty yards to the southward of that little one the beggars used.

He was a Rajput of Rajputs, thin-wristed, thin-ankled, lean, astonishingly handsome in a high-bred Northern way, and possessed of that air of utter self-assuredness devoid of arrogance which people seem able to learn only by being born to it. His fine features were set off by a turban of rose-pink silk, and the only fault discoverable as he strode up the path between the shrubs was that his riding-boots seemed too tight across the instep. There was not a vestige of hair on his face. He was certainly less than twenty, perhaps seventeen years old, or even younger. Ages are hard to guess in that land.

Tess was back on the veranda in time to receive him, with different shoes and stockings, and another ribbon in her hair; few men would have noticed the change at all, although agreeably conscious of the daintiness. The Rajput seemed unable to look away from her but ignoring Chamu, as he came up the steps, appraised her inch by inch from the white shoes upward until as he reached the top their eyes met. Chamu followed him fussily.

Tess could not remember ever having seen such eyes. They were baffling by their quality of brilliance, unlike the usual slumberous Eastern orbs that puzzle chiefly by refusal to express emotion. The Rajput bowed and said nothing, so Tess offered him a chair, which Chamu drew up more fussily than ever.

"Have you had breakfast?" she asked, taking the conscious risk. Strangers of alien race are not invariably good guests, however good-looking, especially when one's husband is somewhere out of call. She looked and felt nearly as young as this man, and had already experienced overtures from more than one young prince who supposed he was doing her an honor. Used to closely guarded women's quarters, the East wastes little time on wooing when the barriers are passed or down. But she felt irresistibly curious, and after all there was Chamu.

"Thanks, I took breakfast before dawn."

The Rajput accepted the proffered chair without acknowledging the butler's existence. Tess passed him the big silver cigarette box.

"Then let me offer you a drink."

He declined both drink and cigarette and there was a minute's silence during which she began to grow uncomfortable.

"I was riding after breakfast—up there on the hill where you see that overhanging rock, when I caught sight of you here on the veranda. You, too, were watching the dawn—beautiful! I love the dawn. So I thought I would come and get to know you. People who love the same thing, you know, are not exactly strangers."

Almost, if not quite for the first time Tess grew very grateful for Chamu, who was still hovering at hand.

"If my husband had known, he would have stayed to receive you."

"Oh, no! I took good care for that! I continued my ride until after I knew he had gone for the day."

Things dawn on your understanding in the East one by one, as the stars come out at night, until in the end there is such a bewildering number of points of light that people talk about the "incomprehensible East." Tess saw light suddenly.

"Do you mean that those three beggars are your spies?"

The Rajput nodded. Then his bright eyes detected the instant resolution that Tess formed.

"But you must not be afraid of them. They will be very useful— often."

"How?"

The visitor made a gesture that drew attention to Chamu.

"Your butler knows English. Do you know Russian?"

"Not a word."

"French?"

"Very little."

"If we were alone—"

Tess decided to face the situation boldly. She came from a free land, and part of her heritage was to dare meet any man face to face; but intuition combined with curiosity to give her confidence.

"Chamu, you may go."

The butler waddled out of sight, but the Rajput waited until the sound of his retreating footsteps died away somewhere near the kitchen. Then:

"You feel afraid of me?" he asked.

"Not at all. Why should I? Why do you wish to see me alone?"

"I have decided you are to be my friend. Are you not pleased?"

"But I don't know anything about you. Suppose you tell me who you are and tell me why you use beggars to spy on my husband."

"Those who have great plans make powerful enemies, and fight against odds. I make friends where I can, and instruments even of my enemies. You are to be my friend."

"You look very young to—"

Suddenly Tess saw light again, and the discovery caused her pupils to contract a little and then dilate. The Rajput noticed it, and laughed. Then, leaning forward:

"How did you know I am a woman? Tell me. I must know. I shall study to act better."

Tess leaned back entirely at her ease at last and looked up at the sky, rather reveling in relief and in the fun of turning the tables.

"Please tell me! I must know!"

"Oh, one thing and another. It isn't easy to explain. For one thing, your insteps."

"I will get other boots. What else? I make no lap. I hold my hands as a man does. Is my voice too high—too excitable?"

"No. There are men with voices like yours. There's a long golden hair on your shoulder that might, of course, belong to some one else, but your ears are pierced—"

"So are many men's."

"And you have blue eyes, and long fair lashes. I've seen occasional Rajput men with blue eyes, too, but your teeth—much too perfect for a man."

"For a young man?"

"Perhaps not. But add one thing to another—"

"There is something else. Tell me!"

"You remember when you called attention to the butler before I dismissed him? No man could do that. You're a woman and you can dance."

"So it is my shoulders? I will study again before the mirror. Yes, I can dance. Soon you shall see me. You shall see all the most wonderful things in Rajputana."

"But tell me about yourself," Tess insisted, offering the cigarettes again. And this time her guest accepted one.

"My mother was the Russian wife of Bubru Singh, who had no son. I am the rightful maharani of Sialpore, only those fools of English put my father's nephew on the throne, saying a woman can not reign. They are no wiser than apes! They have given Sialpore to Gungadhura who is a pig and loathes them instead of to a woman who would only laugh at them, and the brute is raising a litter of little pigs, so that even if he and his progeny were poisoned one by one, there would always be a brat left—he has so many!"

"And you?"

"First you must promise silence."

"Very well."

"Woman to woman!"

"Yes."

"Womb to womb—heart to heart—?"

"On my word of honor. But I promise nothing else, remember!"

"So speaks one whose promises are given truly! We are already friends. I will tell you all that is in my heart now."

"Tell me your name first."

She was about to answer when interruption came from the direction of the gate. There was a restless horse there, and a rider using resonant strong language.

"Tom Tripe!" said Tess. "He's earlier than usual."

The Rajputni smiled. Chamu appeared through the door behind them with suspicious suddenness and waddled to the gate, watched by a pair of blue eyes that should have burned holes in his back and would certainly have robbed him of all comfort had he been aware of them.

Bright spurs that add their roweled row

To clanking saber's pride;

Fierce eyes beneath a beetling brow;

More license than the rules allow;

A military stride;

Years' use of arbitrary will

And right to make or break;

Obedience of men who drill

And willy nilly foot the bill

For authorized mistake;

The comfort of the self-esteem

Deputed power brings—

Are fickler than the shadows seem

Less fruitful than the lotus-dream,

And all of them have wings

When blue eyes, laughing in your own,

Make mockery of rules!

And when those fustian shams have flown

The wise their new allegiance own,

Leaving dead form to fools!

—Thaw on Olympus

THE man at the gate dallied to look at his horse's fetlocks. Tess's strange guest seemed in no hurry either, but her movements were as swift as knitting-needles. She produced a fountain pen, and of all unexpected things, a Bank of India note for one thousand rupees—a new one, crisp and clean. Tess did not see the signature she scrawled across its back in Persian characters, and the pen was returned to an inner pocket and the note, folded four times, was palmed in the subtle hand long before Tom Tripe came striding up the path with jingling spurs.

"Morning, ma'am,—morning! Don't let me intrude. I'd a little accident, and took a liberty. My horse cut his fetlock—nothing serious—and I set your two saises* to work on it with a sponge and water. Twenty minutes—will see it right as a trivet. Then I'm off again—I've a job of work."

[* sais, saice, syce (Hindi)—a coachman, a groom.]

He stood with back to the sun and hands on his hips, looking up at Tess —a man of fifty—a soldier of another generation, in a white uniform something like a British sergeant-major's of the days before the Mutiny. His mutton-chop whiskers, dyed dark-brown, were military mid-Victorian, as were the huge brass spurs that jingled on black riding-boots. A great-chested, heavy-weight athletic man, a few years past his prime.

"Come up, Tom. You're always welcome."

"Ah!" His spurs rang on the stone steps, and, since Tess was standing close to the veranda rail, he turned to face her at the top. Saluting with martinet precision before removing his helmet, he did not get a clear view of the Rajputni. "As I've said many times, ma'am, the one house in the world where Tom Tripe may sit down with princes and commissioners."

"Have you had breakfast?"

He made a wry face.

"The old story, Tom?"

"The old story, ma'am. A hair of the dog that bit me is all the breakfast I could swallow."

"I suppose if I don't give you one now you'll have two later?"

He nodded. "I must. One now would put me just to rights and I'd eat at noon. Times when I'm savage with myself, and wait, I have to have two or three before I can stomach lunch."

She offered him a basket chair and beckoned Chamu.

"Brandy and soda for the sahib."

"Thank you, ma'am!" said the soldier piously.

"Where's your dog, Tom?"

"Behaving himself, I hope, ma'am, out there in the sun by the gate."

"Call him. He shall have a bone on the veranda. I want him to feel as friendly here as you do."

Tom whistled shrilly and an ash-hued creature, part Great Dane and certainly part Rampore,* came up the path like a catapulted phantom, making hardly any sound. He stopped at the foot of the steps and gazed inquiringly at his master's face.

[* Rampore, Rampore hound—a breed of large, strong-limbed, big-boned dogs.]

"You may come up."

He was an extraordinary animal, enormous, big-jowled, scarred, ungainly and apparently aware of it. He paused again on the top step.

"Show your manners."

The beast walked toward Tess, sniffed at her, wagged his stern exactly once and retired to the other end of the veranda, where Chamu, hurrying with brandy gave him the widest possible berth. Tess looked the other way while Tom Tripe helped himself to a lot of brandy and a little soda.

"Now get a big bone for the dog," she ordered.

"There is none," the butler answered.

"Bring the leg-of-mutton bone of yesterday."

"That is for soup today."

"Bring it!"

Chamu was standing between Tom Tripe and the Rajputni, with his back to the latter; so nobody saw the hand that slipped something into the ample folds of his sash. He departed muttering by way of the steps and the garden, and the dog growled acknowledgment of the compliment.

Tess's Rajput guest continued to say nothing; but made no move to go. Introduction was inevitable, for it was the first rule of that house that all ranks met there on equal terms, whatever their relations elsewhere. Tom Tripe had finished wiping his mustache, and Tess was still wondering just how to manage without betraying the sex of the other or the fact that she herself did not yet know her visitor's name, when Chamu returned with the bone. He threw it to the dog from a safe distance, and was sniffed at scornfully for his pains.

"Won't he take it?" asked Tess.

"Not from a black man. Bring it here, you!"

The great brute, with a sidewise growl and glare at the butler that made him sweat with fright, picked up the bone and, at a sign from his master, laid it at the feet of Tess.

"Show your manners!"

Once more he waved his stern exactly once.

"Give it to him, ma'am."

Tess touched the bone with her foot, and the dog took it away, scaring Chamu along the veranda in front of him.

"Why don't you ever call him by name, Tom?"

"Bad for him, ma'am. When I say, 'Here, you!' or whistle, he obeys quick as lightning. But if I say, 'Trotters!' which his name is, he knows he's got to do his own thinking, and keeps his distance till he's sure what's wanted. A dog's like an enlisted man, ma'am; ought to be taught to jump at the word of command and never think for himself until you call him out of the ranks by name. Trotters understands me perfectly."

"Speaking of names," said Tess, "I'd like to introduce you to my guest, Tom, but I'm afraid—"

"You may call me Gunga Singh," said a quiet voice full of amusement, and Tom Tripe started. He turned about in his chair and for the first time looked the third member of the party in the face.

"Hoity-toity! Well, I'm jiggered! Dash my drink and dinner, it's the princess!"

He rose and saluted cavalierly, jocularly, yet with a deference one could not doubt, showing tobacco-darkened teeth in a smile of almost paternal indulgence.

"So the Princess Yasmini is Gunga Singh this morning, eh? And here's Tom Tripe riding up-hill and down-dale, laming his horse and sweating through a clean tunic—with a threat in his ear and a reward promised that he'll never see a smell of—while the princess is smoking cigarettes— "

"In very good company!"

"In good company, aye; but not out of mischief, I'll be bound! Naughty, naughty!" he said, wagging a finger at her. "Your ladyship'll get caught one of these days, and where will Tom Tripe be then? I've got my job to keep, you know. Friendship's friendship and respect's respect, but duty's what I'm paid to do. Here's me, drill-master of the maharajah's troops and a pension coming to me consequent on good behavior, with orders to set a guard over you, miss, and prevent your going and coming without his highness' leave. And here's you giving the guard the slip! Somebody tipped his highness off, and I wish you'd heard what's going to happen to me unless I find you!"

"You can't find me, Tom Tripe! I'm not Yasmini today; I'm Gunga Singh!"

"Tut-tut, Your Ladyship; that won't do! I swore on my Bible oath to the maharajah that I left you day before yesterday closely guarded in the palace across the river. He felt easy for the first time for a week. Now, because they're afraid for their skins, the guard all swear by Krishna you were never in there, and that I've been bribed! How did you get out of the grounds, miss?"

"Climbed the wall."

"I might have remembered you're as active as a cat! Next time I'll mount a double guard on the wall, so they'll tumble off and break their necks if they fall asleep. But there are no boats, for I saw to it, and the bridge is watched. How did you cross the river?"

"Swam."

"At night?"

The blue eyes smiled assent.

"Missy—Your Ladyship, you mustn't do that. Little ladies that act that way might lose the number of their mess. There's crockadowndillies in that river—aggilators—what d'ye call the damp things?— mugger.* They snap their jaws on a leg and pull you under! The sweeter and prettier you are the more they like you! Besides, missy, princesses aren't supposed to swim; it's vulgar."

[* mugger (Hindi magar, "crocodile") —a large crocodile.]

He contrived to look the very incarnation of offended prudery, and she laughed at him with a voice like a golden bell.

He faced Tess again with a gesture of apology.

"You'll pardon me, ma'am, but duty's duty."

Tess was enjoying the play immensely, shrewdly suspecting Tom Tripe of more complaisance than he chose to admit to his prisoner.

"You must treat my house as a sanctuary, Tom. Outside the garden wall orders I suppose are orders. Inside it I insist all guests are free and equal."

The Princess Yasmini slapped her boot with a little riding-switch and laughed delightedly.

"There, Tom Tripe! Now what will you do?"

"I'll have to use persuasion, miss! Tell me how you got into your own palace unseen and out again with a horse without a soul knowing?"

"'Come into my net and get caught,' said the hunter; but the leopard is still at large. 'Teach me your tracks,' begged the hunter; but the leopard answered, 'Learn them!'"

"Hell's bells!"

Tom Tripe scratched his head and wiped sweat from his collar. The princess was gazing away into the distance, not apparently inclined to take the soldier seriously. Tess, wondering what her guest found interesting on the horizon all of a sudden, herself picked out the third beggar's shabby outline on the same high rock from which Yasmini had confessed to watching before dawn.

"Will your ladyship ride home with me?" asked Tom Tripe.

"No."

"But why not?"

"Because the commissioner is coming and there is only one road and he would see me and ask questions. He is stupid enough not to recognize me, but you are too stupid to tell wise lies, and this memsahib is so afraid of an imaginary place called hell that I must stay and do my own—"

"I left off believing in hell when I was ten years old," Tess answered.

"I hope to God you're right, ma'am!" put in Tom Tripe piously, and both women laughed.

"Then I shall trust you and we shall always understand each other," decided Yasmini. "But why will you not tell lies, if there is no hell?"

"I'm afraid I'm guilty now and then."

"But you are ashamed afterward? Why? Lies are necessary, since people are such fools!"

Tom Tripe interrupted, wiping the inside of his tunic collar again with a big bandanna handkerchief.

"How do you know the commissioner is coming, Your Ladyship? Phew! You'd better hide! I'll have to answer too many questions as it is. He'd turn you outside in!"

"There is no hurry," said Yasmini. "He will not be here for five minutes and he is a fool in any case. He is walking his horse up-hill."

Tess too had seen the beggar on the rock remove his ragged turban, rewind it, and then leisurely remove himself from sight. The system of signals was pretty obviously simple. The whole intriguing East is simple, if one only has simplicity enough to understand it.

"Can your horse be seen from the road?" Yasmini asked.

"No, miss. The saises are attending to him under the neem-trees at the rear."

"Then ask the memsahib's permission to pass through the house and leave by the back way."

Tess, more amused than ever, nodded consent and clapped her hands for Chamu to come and do the honors.

"I'll wait here," she said, "and welcome the commissioner."

"But you, Your Ladyship?" Tom Tripe scratched his head in evident confusion. "I've got to account for you, you know."

"You haven't seen me. You have only seen a man named Gunga Singh."

"That's all very fine, missy, but the butler—that man Chamu —he knows you well enough. He'll get the story to the maharajah's ears."

"Leave that to me."

"You dassen't trust him, miss!"

Again came the golden laugh, expressive of the worldly wisdom of a thousand women, and sheer delight in it.

"I shall stay here, if the memsahib permits."

Tess nodded again. "The commissioner shall sit with me on the veranda," Tess said. "Chamu will show you into the parlor."

(The Blaines had never made the least attempt to leave behind their home-grown names for things. Whoever wanted to in Sialpore might have a drawing-room, but whoever came to that house must sit in a parlor or do the other thing.)

"Is it possible the burra-sahib will suppose my horse is yours?" Yasmini asked, and again Tess smiled and nodded. She would know what to say to any one who asked impertinent questions.

Yasmini and Tom Tripe followed Chamu into the house just as the commissioner's horse's nose appeared past the gate-post; and once behind the curtains in the long hall that divided room from room, Tom Tripe called a halt to make a final effort at persuasion.

"Now, missy, Your Ladyship, please!"

But she had no patience to spare for him.

"Quick! Send your dog to guard that door!"

Tom Tripe snapped his fingers and made a motion with his right hand. The dog took up position full in the middle of the passage blocking the way to the kitchen and alert for anything at all, but violence preferred. Chamu, all sly smiles and effusiveness until that instant, as one who would like to be thought a confidential co-conspirator, now suddenly realized that his retreat was cut off. No explanation had been offered, but the fact was obvious and conscience made the usual coward of him. He would rather have bearded Tom Tripe than the dog.

Yasmini opened on him in his own language, because there was just a chance that otherwise Tess might overhear through the open window and put two and two together.

"Scullion! Dish-breaker! Conveyor of uncleanness! You have a son?"

"Truly, heaven-born. One son, who grows into a man—the treasure of my old heart."

"A gambler!"

"A young man, heaven-born, who feels his manhood—now and then gay —now and then foolish "

"A budmash!" (Bad rascal.)

"Nay, an honest one!"

"Who borrowed from Mukhum Dass the money-lender, making untrue promises?"

"Nay, the money was to pay a debt."

"A gambling debt, and he lied about it."

"Nay, truly, heaven-born, he but promised Mukhum Dass he would repay the sum with interest."

"Swearing he would buy with the money, two horses which Mukhum Dass might seize as forfeit after the appointed time!"

"Otherwise, heaven-born, Mukhum Dass would not have lent the money!"

"And now Mukhum Dass threatens prison?"

"Truly, heaven-born. The money-lender is without shame—without mercy—without conscience."

"And that is why you—dog of a spying butler set to betray the sahib's salt you eat—man of smiles and welcome words!—stole money from me? Was it to pay the debt of thy gambling brat-born-in-a-stable?"

"I, heaven-born? I steal from thee? I would rather be beaten!"

"Thou shalt be beaten, and worse, thou and thy son! Feel in his cummerbund, Tom Tripe! I saw where the money went!"

Promptly into the butler's sash behind went fingers used to delving into more unmilitary improprieties than any ten civilians could think of. Tripe produced the thousand-rupee note in less than half a minute and, whether or not he believed it stolen, saw through the plan and laughed.

"Is my name on the back of it?" Yasmini asked.

Tom Tripe displayed the signature, and Chamu's clammy face turned ashen-gray.

"And," said Yasmini, fixing Chamu with angry blue eyes, "the commissioner sahib is on the veranda! For the reputation of the English he would cause an example to be made of servants who steal from guests in the house of foreigners."

Chamu capitulated utterly, and wept.

"What shall I do? What shall I do?" he demanded.

"In the jail," Yasmini said slowly, "you could not spy on my doings, nor report my sayings."

"Heaven-born, I am dumb! Only take back the money and I am dumb forever, never seeing or having seen or heard either you or this sahib here! Take back the money!"

But Yasmini was not so easily balked of her intention.

"Put his thumb-print on it, Tom Tripe, and see that he writes his name."

The trembling Chamu was led into a room where an ink-pot stood open on a desk, and watched narrowly while he made a thumb-mark and scratched a signature. Then:

"Take the money and pay thy puppy's debt with it. Afterward beat the boy. And see to it," Yasmini advised, "that Mukhum Dass gives a receipt, lest he claim the debt a second time!"

Speechless between relief, doubt and resentment Chamu hid the banknote in his sash and tried to feign gratitude—a quality omitted from his list of elements when a patient, caste-less mother brought him yelling into the world.

"Go!"

Tom Tripe made a sign to Trotters, who went and lay down, obviously bored, and Chamu departed backward, bowing repeatedly with both hands raised to his forehead.

"And now, Your Ladyship?"

"Take that eater-of-all-that-is-unnamable," (she meant the dog), "and return to the palace."

"Your Ladyship, it's all my life's worth!"

"Tell the maharajah that you have spoken with a certain Gunga Singh, who said that the Princess Yasmini is at the house of the commissioner sahib."

"But it's not true; they'll—"

"Let the commissioner sahib deny it then! Go!"

"But, missy—"

"Do as I say, Tom Tripe, and when I am maharani of Sialpore you shall have double pay—and a troupe of dancing girls—and a dozen horses —and the title of bahadur—and all the brandy you can drink. The sepoys shall furthermore have modern uniforms, and you shall drill them until they fall down dead. I have promised. Go!"

With a wag of his head that admitted impotence in the face of woman's wiles Tom strode out by the back way, followed at a properly respectful distance by his "eater-of-all-that-is-unnamable."

Then the princess walked through the parlor to the deeply cushioned window-seat, outside which the commissioner sat quite alone with Mrs. Blaine, trying to pull strings whose existence is not hinted at in blue books. Yasmini from earliest infancy possessed an uncanny gift of silence, sometimes even when she laughed.

There's comfort in the purple creed

Of rosary and hood;

There's promise in the temple gong,

And hope (deferred) when evensong

Foretells a morrow's good;

There's rapture in the royal right

To lay the daily dole

In cash or kind at temple-door,

Since sacrifice must go before

The saving of a soul.

The priests who plot for power now,

Though future glory preach,

Themselves alike the victims fall

Of law that mesmerizes all—

Each subject unto each—

Though all is well if all obey

And all have humble heart,

Nor dare to hold in cursed doubt

Those gems of truth the church lets out;

But where's the apple-cart,

And where's the sacred fiction gone,

And who's to have the blame

When any upstart takes a hand

And, scorning what the priests have planned,

Plays Harry with the game?

—No Trespass!

HE was a beau ideal commissioner. The native newspaper said so when he first came, having painfully selected the phrase from a "Dictionary Of Polite English for Public Purposes" edited by a College graduate at present in the Andamans. True, later it had called him an "overbearing and insane procrastinator"—"an apostle of absolutism" —and, plum of all literary gleanings, since it left so much to the imagination of the native reader,—"laudator temporis acti." But that the was because he had withdrawn his private subscription prior to suspending the paper sine die under paragraph so-and-so of the Act for Dealing with Sedition; it could not be held to cancel the correct first judgment, any more than the unmeasured early praise had offset later indiscretion. Beau ideal must stand.

It was not his first call at the Blaines' house, although somehow or other he never contrived to find Dick Blaine at home. As a bachelor he had no domestic difficulties to pin him down when office work was over for the morning, and, being a man of hardly more than forty, of fine physique, with an astonishing capacity for swift work, he could usual finish in an hour before breakfast what would have kept the routine rank and file of orthodox officials perspiring through the day. That was one reason why he had been sent to Sialpore—men in the higher ranks, with a pension due them after certain years of service, dislike being hurried.

He was a handsome man—too handsome, some said—with a profile like a medallion of Mark Anthony that lost a little of its strength and poise when he looked straight at you. A commissionership was an apparent rise in the world; but Sialpore has the name of being a departmental cul-de-sac, and they had laughed in the clubs about "Irish promotion" without exactly naming judge O'Mally. (Mrs. O'Mally came from a cathedral city, where distaste for the conventions is forced at high pressure from early infancy.)

But there are no such things as political blind alleys to a man who is a judge of indiscretion, provided he has certain other unusual gifts as well. Sir Roland Samson, K. C. S. I., was not at all a disappointed man, nor even a discouraged one.

Most people were at a disadvantage coming up the path through the Blaines' front garden. There was a feeling all the way of being looked down on from the veranda that took ten minutes to recover from in the subsequent warmth of Western hospitality. But Samson had learned long ago that appearance was all in his favor, and he reinforced it with beautiful buff riding-boots that drew attention to firm feet and manly bearing. It did him good to be looked at, and he felt, as a painstaking gentleman should, that the sight did spectators no harm.

"All alone?" he asked, feeling sure that Mrs. Blaine was pleased to see him, and shifting the chair beside her as he sat down in order to see her face better. "Husband in the hills as usual? I must choose a Sunday next time and find him in."

Tess smiled. She was used to the remark. He always made it, but always kept away on Sundays.

"There was a party at my house last night, and every one agreed what an acquisition you and your husband are to Sialpore. You're so refreshing —quite different to what we're all used to."

"We're enjoying the novelty too—at least, Dick doesn't have much time for enjoyment, but—"

"I suppose he has had vast experience of mining?"

"Oh, he knows his profession, and works hard. He'll find gold where there is any," said Tess.

"You never told me how he came to choose Sialpore as prospecting ground."

Tess recognized the prevarication instantly. Almost the first thing Dick had done after they arrived was to make a full statement of all the circumstances in the commissioner's office. However, she was not her husband. There was no harm in repetition.

"The maharajah's secretary wrote to a mining college in the States for the name of some one qualified to explore the old workings in these hills. They gave my husband's name among others, and he got in correspondence. Finally, being free at the time, we came out here for the trip, and the maharajah offered terms on the spot that we accepted. That is all."

Samson laughed.

"I'm afraid not all. A contract with the British Government would be kept. I won't say a written agreement with Gungadhura is worthless, but— "

"Oh, he has to pay week by week in advance to cover expenses."

"Very wise. But how about if you find gold?"

"We get a percentage."

Every word of that, as Tess knew, the commissioner could have ascertained in a minute from his office files. So she was quite as much on guard as he —quite as alert to discover hidden drifts.

"I'm afraid there'll be complications," he went on with an air of friendly frankness. "Perhaps I'd better wait until I can see your husband?"

"If you like, of course. But he and I speak the same language. What you tell me will reach him—anything you say, just as you say it."

"I'd better be careful then!" he answered, smiling. "Wise wives don't always tell their husbands everything."

"I've no secrets from mine."

"Unusual!" he smiled. "I might say obsolete! But you Americans with your reputation for divorce and originality are very old-fashioned in some things, aren't you?"

"What did you want me to tell my husband?" countered Tess.

"I wonder if he understands how complicated conditions are here. For instance, does your contract stipulate where the gold is to be found?"

"On the maharajah's territory."

"Anywhere within those limits?"

"So I understand."

"Is the kind of gold mentioned?"

"How many kinds are there?"

He gained thirty seconds for reflection by lighting a cigar, and decided to change his ground.

"I know nothing of geology, I'm afraid. I wonder if your husband knows about the so-called islands? There are patches of British territory, administered directly by us, within the maharajah's boundaries; and little islands of native territory administered by the maharajah's government within the British sphere."

"Something like our Indian reservations, I suppose?"

"Not exactly, but the analogy will do. If your husband were to find gold —of any kind—on one of our 'islands' within the maharajah's territory, his contract with the maharajah would be useless."

"Are the boundaries of the islands clearly marked?"

"Not very. They're known, of course, and recorded. There's an old fort on one of them, garrisoned by a handful of British troops—a constant source of heart-burn, I believe, to Gungadhura. He can see the top of the flag-staff from his palace roof; a predecessor of mine had the pole lengthened, I'm told. On the other hand, there's a very pretty little palace over on our side of the river with about a half square mile surrounding it that pertains to the native State. Your husband could dig there, of course. There's no knowing that it might not pay—if he's looking for more kinds of gold than one."

Tess contrived not to seem aware that she was being pumped.

"D'you mean that there might be alluvial gold down by the river?" she asked.

"Now, now, Mrs. Blaine!" he laughed. "You Americans are not so ingenuous as you like to seem! Do you really expect us to believe that your husband's purpose isn't in fact to discover the Sialpore Treasure?"

"I never heard of it."

"I suspect he hasn't told you."

"I'll bet with you, if you like," she answered. "Our contract against your job that I know every single detail of his terms with Gungadhura!"

"Well, well,—of course I believe you, Mrs. Blaine. We're not overheard are we?"

Not forgetful of the Princess Yasmini hidden somewhere in the house behind her, but unsuspicious yet of that young woman's gift for garnering facts, Tess stood up to look through the parlor window. She could see all of the room except the rear part of the window-seat, a little more than a foot of which was shut out of her view by the depth of the wall. A cat, for instance, could have lain there tucked among the cushions perfectly invisible.

"None of the servants is in there," she said, and sat down again, nodding in the direction of a gardener. "There's the nearest possible eavesdropper."

Samson had made up his mind. This was not an occasion to be actually indiscreet, but a good chance to pretend to be. He was a judge of those matters.

"There have been eighteen rajahs of Sialpore in direct succession father to son," he said, swinging a beautiful buff-leather boot into view by crossing his knee, and looking at her narrowly with the air of a man who unfolds confidences. "The first man began accumulating treasure. Every single rajah since has added to it. Each man has confided the secret to his successor and to none else—father to son, you understand. When Bubru Singh, the last man, died he had no son. The secret died with him."

"How does anybody know that there's a secret then?" demanded Tess.

"Everybody knows it! The money was raised by taxes. Minister after minister in turn has had to hand over minted gold to the reigning rajah—"

"And look the other way, I suppose, while the rajah hid the stuff!" suggested Tess.

Samson screwed up his face like a man who has taken medicine.

"There are dozens of ways in a native state of getting rid of men who know too much."

"Even under British overrule?"

He nodded. "Poison—snakes—assassination—jail on trumped-up charges, and disease in jail—apparent accidents of all sorts. It doesn't pay to know too much."

"Then we're suspected of hunting for this treasure? Is that the idea?"

"Not at all, since you've denied it. I believe you implicitly. But I hope your husband doesn't stumble on it."

"Why?"

"Or if he does, that he'll see his way clear to notify me first."

"Would that be honest?"

He changed his mind. That was a point on which Samson prided himself. He was not hidebound to one plan as some men are, but could keep two or three possibilities in mind and follow up whichever suited him. This was a case for indiscretion after all.

"Seeing we're alone, and that you're a most exceptional woman, I think I'll let you into a diplomatic secret, Mrs. Blaine. Only you mustn't repeat it. The present maharajah, Gungadhura, isn't the saving kind; he's a spender. He'd give his eyes to get hold of that treasure. And if he had it, we'd need an army to suppress him. We made a mistake when Bubru Singh died; there were two nephews with about equal claims, and we picked the wrong one—a born intriguer. I'd call him a rascal if he weren't a reigning prince. It's too late now to unseat him—unless, of course, we should happen to catch him in flagrante delicto."

"What does that mean? With the goods? With the treasure?"

"No, no. In the act of doing something grossly ultra vires— illegal, that's to say. But you've put your finger on the point. If the treasure should be found—as it might be—somewhere hidden on that little plot of ground with a palace on it on our side of the river, our problem would be fairly easy. There'd be some way of—ah— making sure the fund would be properly administered. But if Gungadhura found it in the hills, and kept quiet about it as he doubtless would, he'd have every sedition-monger in India in his pay within a year, and the consequences might be very serious."

"Who is the other man—the one the British didn't choose?" asked Tess.

"A very decent chap named Utirupa—quite a sportsman. He was thought too young at the time the selection was made; but he knew enough to get out of the reach of the new maharajah immediately. They have a phrase here, you know, 'to hate like cousins.' They're rather remote cousins, but they hate all the more for that."

"So you'd rather that the treasure stayed buried?"

"Not exactly. But he tossed ash from the end of his cigar to illustrate offhandedness. "I think I could promise ten per cent. of it to whoever brought us exact information of its whereabouts before the maharajah could lay his hands on it."

"I'll tell that to my husband."

"Do."

"Of course, being in a way in partnership with Gungadhura, he might —"

"Let me give you one word of caution, if I may without offense. We— our government—wouldn't recognize the right of—of any one to take that treasure out of the country. Ten per cent. would be the maximum, and that only in case of accurate information brought in time to us."

"Aren't findings keepings? Isn't possession nine points of the law?" laughed Tess.

"In certain cases, yes. But not where government knows of the existence somewhere of a hoard of public funds—an enormous hoard—it must run into millions."

"Then, if the maharajah should find it would you take it from him?"

"No. We would put the screws on, and force him to administer the fund properly if we knew about it. But he'd never tell."

"Then how d'you know he hasn't found the stuff already?"

"Because many of his personal bills aren't paid, and the political stormy petrels are not yet heading his way. He's handicapped by not being able to hunt for it openly. Some ill-chosen confidant might betray the find to us. I doubt if he trusts more than one or two people at a time."

"It must be hell to be a maharajah!" Tess burst out after a minute's silence.

"It's sometimes hell to be commissioner, Mrs. Blaine."

"If I were Gungadhura I'd find that money or bust! And when I'd found it—"

"You'd endow an orphan asylum, eh?"

"I'd make such trouble for you English that you'd be glad to leave me in peace for a generation!"

Samson laughed good-naturedly and twisted up the end of his mustache.

"Pon my soul, you're a surprising woman! So your sympathies are all with Gungadhura?"

"Not at all. I think he's a criminal! He buys women, and tortures animals in an arena, and keeps a troupe of what he is pleased to call dancing-girls. I've seen his eyes in the morning, and I suspect him of most of the vices in the calendar. He's despicable. But if I were in his shoes I'd find that money and make it hot for you English!"

"Are you of Irish extraction, Mrs. Blaine?"

"No, indeed I'm not. I'm Connecticut Yankee, and my husband's from the West. I don't have to be Irish to think for myself, do I?"

Samson did not know whether or not to take her seriously, but recognized that his chance had gone that morning for the flirtation he had had in view —very mild, of course, for a beginning; it was his experience that most things ought to start quite mildly, if you hoped to keep the other man from stampeding the game. Nevertheless, as a judge of situations, be preferred not to take his leave at that moment. Give a woman the last word always, but be sure it is a question, which you leave unanswered.

"You've a beautiful garden," he said; and for a minute or two they talked of flowers, of which he knew more than a little; then of music, of which he understood a very great deal.

"Have you a proper lease on this house?" he asked at last.

"I believe so. Why?"

"I've been told there's some question about the title. Some one's bringing suit against your landlord for possession on some ground or another."

"What of it? Suppose the other should win—could he put us out?"

"I don't know. That might depend on your present landlord's power to make the lease at the time when he made it."

"But we signed the agreement in good faith. Surely, as long as we pay the rent—?"

"I don't know, I'm sure. Well—if there's any trouble, come to me about it and we'll see what can be done."

"But who is this who is bringing suit against the landlord?"

"I haven't heard his name—don't even know the details. I hope you'll come out of it all right. Certainly I'll help in any way I can. Sometimes a little influence, you know, exerted in the right way—well —Please give my regards to your husband—Good morning, Mrs. Blaine."

It was a pet theory of his that few men pay enough attention to their backs,—not that he preached it; preaching is tantamount to spilling beans, supposing that the other fellow listens; and if he doesn't listen it is waste of breath. But he bore in mind that people behind him had eyes as well as those in front. Accordingly he made a very dignified exit down the long path, tipped Mrs. Blaine's sais all the man had any right to expect, and rode away feeling that he had made the right impression. He looked particularly well on horseback.

Theresa Blaine smiled after him, wondering what impression she herself had made; but she did not have much time to think about it. From the open window behind her she was seized suddenly, drawn backward and embraced.

"You are perfect!" Yasmini purred in her ear between kisses. "You are surely one of the fairies sent to live among mortals for a sin! I shall love you forever! Now that burra-wallah Samson sahib will ride into the town, and perhaps also to the law-court, and to other places, to ask about your landlord, of whom he knows nothing, having only heard a servant's tale. But Tom Tripe will have told already that I am at the burra commissioner's house, and Gungadhura will send there to ask questions. And whoever goes will have to wait long. And when the commissioner returns at last he will deny that I have been there, and the messenger will return to Gungadhura, who will not believe a word of it, especially as he will know that the commissioner has been riding about the town on an unknown errand. So, after he has learned that I am back in my own palace, Gungadhura will try to poison me again. All of which is as it should be. Come closer and let me—"

"Child!" Tess protested. "Do you realize that you're dressed up like an extremely handsome man, and are kissing me through a window in the sight of all Sialpore? How much reputation do you suppose I shall have left within the hour?

"There is only one kind of reputation worth the having," laughed Yasmini; "that of knowing how to win!"

"But what's this about poison?" Tess asked her.

"He always tries to poison me. Now he will try more carefully."

"You must take care! How will you prevent him?"

By quite unconscious stages Tess found herself growing concerned about this young truant princess. One minute she was interested and amused. The next she was conscious of affection. Now she was positively anxious about her, to use no stronger word. Nor had she time to wonder why, for Yasmini's methods were breathless.

"I shall eat very often at your house. And then you shall take a journey with me. And after that the great pig Gungadhura shall be very sorry he was born, and still more sorry that be tried to poison me!"

"Tell me, child, haven't you a mother?"

"She died a year ago. If there is such a place as hell she has gone there, of course, because nobody is good enough for Heaven. But I am not Christian and not Hindu, so hell is not my business."

"What are you, then?"