an ebook published by Project Gutenberg Australia

Title: On Our Selection

Author: Steele Rudd

eBook No.: e00095.html

Language: English

Date first posted: Jan 2013

Most recent update: Oct 2023

This eBook was produced by: Walter Moore

To You “Who Gave Our Country Birth;”

to the memory of You

whose names, whose giant enterprise, whose deeds of

fortitude and daring

were never engraved on tablet or tombstone;

to You who strove through the silences of the Bush-lands

and made them ours;

to You who delved and toiled in loneliness through

the years that have faded away;

to You who have no place in the history of our Country

so far as it is yet written;

to You who have done MOST for this Land;

to You for whom few, in the march of settlement, in the turmoil

of busy city life, now appear to care;

and to you particularly,

GOOD OLD DAD,

This Book is most affectionately dedicated.

“STEELE RUDD”

Chapter 1. - Starting The Selection

Chapter 2. - Our First Harvest

Chapter 3. - Before We Got The Deeds

Chapter 4. - When The Wolf Was At The Door

Chapter 5. - The Night We Watched For Wallabies

Chapter 6. - Good Old Bess

Chapter 7. - Cranky Jack

Chapter 8. - A Kangaroo Hunt From Shingle Hut

Chapter 9. - Dave’s Snakebite

Chapter 10. - Dad And The Donovans

Chapter 11. - A Splendid Year For Corn

Chapter 12. - Kate’s Wedding

Chapter 13. - The Summer Old Bob Died

Chapter 14. - When Dan Came Home

Chapter 15. - Our Circus

Chapter 16. - When Joe Was In Charge

Chapter 17. - Dad’s “Fortune”

Chapter 18. - We Embark In The Bear Industry

Chapter 19. - Nell And Ned

Chapter 20. - The Cow We Bought

Chapter 21. - The Parson And The Scone

Chapter 22. - Callaghan’s Colt

Chapter 23. - The Agricultural Reporter

Chapter 24. - A Lady At Shingle Hut

Chapter 25. - The Man With The Bear-Skin Cap

Chapter 26. - One Christmas

It’s twenty years ago now since we settled on the Creek. Twenty years! I remember well the day we came from Stanthorpe, on Jerome’s dray—eight of us, and all the things—beds, tubs, a bucket, the two cedar chairs with the pine bottoms and backs that Dad put in them, some pint-pots and old Crib. It was a scorching hot day, too—talk about thirst! At every creek we came to we drank till it stopped running.

Dad didn’t travel up with us: he had gone some months before, to put up the house and dig the waterhole. It was a slabbed house, with shingled roof, and space enough for two rooms; but the partition wasn’t up. The floor was earth; but Dad had a mixture of sand and fresh cow-dung with which he used to keep it level. About once every month he would put it on; and everyone had to keep outside that day till it was dry. There were no locks on the doors: pegs were put in to keep them fast at night; and the slabs were not very close together, for we could easily see through them anybody coming on horseback. Joe and I used to play at counting the stars through the cracks in the roof.

The day after we arrived Dad took Mother and us out to see the paddock and the flat on the other side of the gully that he was going to clear for cultivation. There was no fence round the paddock, but he pointed out on a tree the surveyor’s marks, showing the boundary of our ground. It must have been fine land, the way Dad talked about it! There was very valuable timber on it, too, so he said; and he showed us a place, among some rocks on a ridge, where he was sure gold would be found, but we weren’t to say anything about it. Joe and I went back that evening and turned over every stone on the ridge, but we didn’t find any gold.

No mistake, it was a real wilderness—nothing but trees, “goannas,” dead timber, and bears; and the nearest house—Dwyer’s—was three miles away. I often wonder how the women stood it the first few years; and I can remember how Mother, when she was alone, used to sit on a log, where the lane is now, and cry for hours. Lonely! It was lonely.

Dad soon talked about clearing a couple of acres and putting in corn—all of us did, in fact—till the work commenced. It was a delightful topic before we started; but in two weeks the clusters of fires that illumined the whooping bush in the night, and the crash upon crash of the big trees as they fell, had lost all their poetry.

We toiled and toiled clearing those four acres, where the haystacks are now standing, till every tree and sapling that had grown there was down. We thought then the worst was over; but how little we knew of clearing land! Dad was never tired of calculating and telling us how much the crop would fetch if the ground could only be got ready in time to put it in; so we laboured the harder.

With our combined male and female forces and the aid of a sapling lever we rolled the thundering big logs together in the face of Hell’s own fires; and when there were no logs to roll it was tramp, tramp the day through, gathering armfuls of sticks, while the clothes clung to our backs with a muddy perspiration. Sometimes Dan and Dave would sit in the shade beside the billy of water and gaze at the small patch that had taken so long to do; then they would turn hopelessly to what was before them and ask Dad (who would never take a spell) what was the use of thinking of ever getting such a place cleared? And when Dave wanted to know why Dad didn’t take up a place on the plain, where there were no trees to grub and plenty of water, Dad would cough as if something was sticking in his throat, and then curse terribly about the squatters and political jobbery. He would soon cool down, though, and get hopeful again.

“Look at the Dwyers,” he’d say; “from ten acres of wheat they got seventy pounds last year, besides feed for the fowls; they’ve got corn in now, and there’s only the two.”

It wasn’t only burning off! Whenever there came a short drought the waterhole was sure to run dry; then it was take turns to carry water from the springs—about two miles. We had no draught horse, and if we had there was neither water-cask, trolly, nor dray; so we humped it—and talk about a drag! By the time you returned, if you hadn’t drained the bucket, in spite of the big drink you’d take before leaving the springs, more than half would certainly be spilt through the vessel bumping against your leg every time you stumbled in the long grass. Somehow, none of us liked carrying water. We would sooner keep the fires going all day without dinner than do a trip to the springs.

One hot, thirsty day it was Joe’s turn with the bucket, and he managed to get back without spilling very much. We were all pleased because there was enough left after the tea had been made to give each a drink. Dinner was nearly over; Dan had finished, and was taking it easy on the sofa, when Joe said:

“I say, Dad, what’s a nater-dog like?”

Dad told him: “Yellow, sharp ears and bushy tail.”

“Those muster bin some then thet I seen—I don’t know ’bout the bushy tail—all th’ hair had comed off.”

“Where’d y’ see them, Joe?” we asked. “Down ’n th’ springs floating about—dead.”

Then everyone seemed to think hard and look at the tea. I didn’t want any more. Dan jumped off the sofa and went outside; and Dad looked after Mother.

At last the four acres—excepting the biggest of the iron-bark trees and about fifty stumps—were pretty well cleared; and then came a problem that couldn’t be worked-out on a draught-board. I have already said that we hadn’t any draught horses; indeed, the only thing on the selection like a horse was an old “tuppy” mare that Dad used to straddle. The date of her foaling went further back than Dad’s, I believe; and she was shaped something like an alderman. We found her one day in about eighteen inches of mud, with both eyes picked out by the crows, and her hide bearing evidence that a feathery tribe had made a roost of her carcase. Plainly, there was no chance of breaking up the ground with her help. We had no plough, either; how then was the corn to be put in? That was the question.

Dan and Dave sat outside in the corner of the chimney, both scratching the ground with a chip and not saying anything. Dad and Mother sat inside talking it over. Sometimes Dad would get up and walk round the room shaking his head; then he would kick old Crib for lying under the table. At last Mother struck something which brightened him up, and he called Dave.

“Catch Topsy and—” He paused because he remembered the old mare was dead.

“Run over and ask Mister Dwyer to lend me three hoes.”

Dave went; Dwyer lent the hoes; and the problem was solved. That was how we started.

If there is anything worse than burr-cutting or breaking stones, it’s putting corn in with a hoe.

We had just finished. The girls were sowing the last of the grain when Fred Dwyer appeared on the scene. Dad stopped and talked with him while we (Dan, Dave and myself) sat on our hoe-handles, like kangaroos on their tails, and killed flies. Terrible were the flies, particularly when you had sore legs or the blight.

Dwyer was a big man with long, brown arms and red, bushy whiskers.

“You must find it slow work with a hoe?” he said.

“Well-yes-pretty,” replied Dad (just as if he wasn’t quite sure).

After a while Dwyer walked over the “cultivation”, and looked at it hard, then scraped a hole with the heel of his boot, spat, and said he didn’t think the corn would ever come up. Dan slid off his perch at this, and Dave let the flies eat his leg nearly off without seeming to feel it; but Dad argued it out.

“Orright, orright,” said Dwyer; “I hope it do.”

Then Dad went on to speak of places he knew of where they preferred hoes to a plough for putting corn in with; but Dwyer only laughed and shook his head.

“D—n him!” Dad muttered, when he had gone; “what rot! Won’t come up!”

Dan, who was still thinking hard, at last straightened himself up and said he didn’t think it was any use either. Then Dad lost his temper.

“No use?” he yelled, “you whelp, what do you know about it?”

Dan answered quietly: “On’y this, that it’s nothing but tomfoolery, this hoe business.”

“How would you do it then?” Dad roared, and Dan hung his head and tried to button his buttonless shirt wrist-band while he thought.

“With a plough,” he answered.

Something in Dad’s throat prevented him saying what he wished, so he rushed at Dan with the hoe, but—was too slow.

Dan slept outside that night.

No sooner was the grain sown than it rained. How it rained! for weeks! And in the midst of it all the corn came up—every grain-and proved Dwyer a bad prophet. Dad was in high spirits and promised each of us something—new boots all round.

The corn continued to grow—so did our hopes, but a lot faster. Pulling the suckers and “heeling it up” with hoes was but child’s play—we liked it. Our thoughts were all on the boots; ’twas months since we had pulled on a pair. Every night, in bed, we decided twenty times over whether they would be lace-ups or bluchers, and Dave had a bottle of “goanna” oil ready to keep his soft with.

Dad now talked of going up country—as Mother put it, “to keep the wolf from the door”—while the four acres of corn ripened. He went, and returned on the day Tom and Bill were born—twins. Maybe his absence did keep the wolf from the door, but it didn’t keep the dingoes from the fowl-house!

Once the corn ripened it didn’t take long to pull it, but Dad had to put on his considering-cap when we came to the question of getting it in. To hump it in bags seemed inevitable till Dwyer asked Dad to give him a hand to put up a milking-yard. Then Dad’s chance came, and he seized it.

Dwyer, in return for Dad’s labour, carted in the corn and took it to the railway-station when it was shelled. Yes, when it was shelled! We had to shell it with our hands, and what a time we had! For the first half-hour we didn’t mind it at all, and shelled cob after cob as though we liked it; but next day, talk about blisters! we couldn’t close our hands for them, and our faces had to go without a wash for a fortnight.

Fifteen bags we got off the four acres, and the storekeeper undertook to sell it. Corn was then at 12 shillings and 14 shillings per bushel, and Dad expected a big cheque.

Every day for nearly three weeks he trudged over to the store (five miles) and I went with him. Each time the storekeeper would shake his head and say “No word yet.”

Dad couldn’t understand. At last word did come. The storekeeper was busy serving a customer when we went in, so he told Dad to “hold on a bit”.

Dad felt very pleased—so did I.

The customer left. The storekeeper looked at Dad and twirled a piece of string round his first finger, then said—“Twelve pounds your corn cleared, Mr. Rudd; but, of course” (going to a desk) “there’s that account of yours which I have credited with the amount of the cheque—that brings it down now to just three pound, as you will see by the account.”

Dad was speechless, and looked sick.

He went home and sat on a block and stared into the fire with his chin resting in his hands, till Mother laid her hand upon his shoulder and asked him kindly what was the matter. Then he drew the storekeeper’s bill from his pocket, and handed it to her, and she too sat down and gazed into the fire.

That was our first harvest.

Our selection adjoined a sheep-run on the Darling Downs, and boasted of few and scant improvements, though things had gradually got a little better than when we started. A verandahless four-roomed slab-hut now standing out from a forest of box-trees, a stock-yard, and six acres under barley were the only evidence of settlement. A few horses—not ours—sometimes grazed about; and occasionally a mob of cattle—also not ours—cows with young calves, steers, and an old bull or two, would stroll around, chew the best legs of any trousers that might be hanging on the log reserved as a clothes-line, then leave in the night and be seen no more for months—some of them never.

And yet we were always out of meat!

Dad was up the country earning a few pounds—the corn drove him up when it didn’t bring what he expected. All we got out of it was a bag of flour—I don’t know what the storekeeper got. Before he left we put in the barley. Somehow, Dad didn’t believe in sowing any more crops, he seemed to lose heart; but Mother talked it over with him, and when reminded that he would soon be entitled to the deeds he brightened up again and worked. How he worked!

We had no plough, so old Anderson turned over the six acres for us, and Dad gave him a pound an acre—at least he was to send him the first six pounds got up country. Dad sowed the seed; then he, Dan and Dave yoked themselves to a large dry bramble each and harrowed it in. From the way they sweated it must have been hard work. Sometimes they would sit down in the middle of the paddock and “spell” but Dad would say something about getting the deeds and they’d start again.

A cockatoo-fence was round the barley; and wire-posts, a long distance apart, round the grass-paddock. We were to get the wire to put in when Dad sent the money; and apply for the deeds when he came back. Things would be different then, according to Dad, and the farm would be worked properly. We would break up fifty acres, build a barn, buy a reaper, ploughs, cornsheller, get cows and good horses, and start two or three ploughs. Meanwhile, if we (Dan, Dave and I) minded the barley he was sure there’d be something got out of it.

Dad had been away about six weeks. Travellers were passing by every day, and there wasn’t one that didn’t want a little of something or other. Mother used to ask them if they had met Dad? None ever did until an old grey man came along and said he knew Dad well—he had camped with him one night and shared a damper. Mother was very pleased and brought him in. We had a kangaroo-rat (stewed) for dinner that day. The girls didn’t want to lay it on the table at first, but Mother said he wouldn’t know what it was. The traveller was very hungry and liked it, and when passing his plate the second time for more, said it wasn’t often he got any poultry.

He tramped on again, and the girls were very glad he didn’t know it was a rat. But Dave wasn’t so sure that he didn’t know a rat from a rooster, and reckoned he hadn’t met Dad at all.

The seventh week Dad came back. He arrived at night, and the lot of us had to get up to find the hammer to knock the peg out of the door and let him in. He brought home three pounds—not enough to get the wire with, but he also brought a horse and saddle. He didn’t say if he bought them. It was a bay mare, a grand animal for a journey—so Dad said—and only wanted condition. Emelina, he called her. No mistake, she was a quiet mare! We put her where there was good feed, but she wasn’t one that fattened on grass. Birds took kindly to her—crows mostly—and she couldn’t go anywhere but a flock of them accompanied her. Even when Dad used to ride her (Dan or Dave never rode her) they used to follow, and would fly on ahead to wait in a tree and “caw” when he was passing beneath.

One morning when Dan was digging potatoes for dinner—splendid potatoes they were, too, Dad said; he had only once tasted sweeter ones, but they were grown in a cemetery—he found the kangaroos had been in the barley. We knew what that meant, and that night made fires round it, thinking to frighten them off, but didn’t—mobs of them were in at daybreak. Dad swore from the house at them, but they took no notice; and when he ran down, they just hopped over the fence and sat looking at him. Poor Dad! I don’t know if he was knocked up or if he didn’t know any more, but he stopped swearing and sat on a stump looking at a patch of barley they had destroyed, and shaking his head. Perhaps he was thinking if he only had a dog! We did have one until he got a bait. Old Crib! He was lying under the table at supper-time when he took the first fit, and what a fright we got! He must have reared before stiffening out, because he capsized the table into Mother’s lap, and everything on it smashed except the tin-plates and the pints. The lamp fell on Dad, too, and the melted fat scalded his arm. Dad dragged Crib out and cut off his tail and ears, but he might as well have taken off his head.

Dad stood with his back to the fire while Mother was putting a stitch in his trousers. “There’s nothing for it but to watch them at night,” he was saying, when old Anderson appeared and asked “if I could have those few pounds.” Dad asked Mother if she had any money in the house? Of course she hadn’t. Then he told Anderson he would let him have it when he got the deeds. Anderson left, and Dad sat on the edge of the sofa and seemed to be counting the grains on a corn-cob that he lifted from the floor, while Mother sat looking at a kangaroo-tail on the table and didn’t notice the cat drag it off. At last Dad said, “Ah, well!—it won’t be long now, Ellen, before we have the deeds!”

We took it in turns to watch the barley. Dan and the two girls watched the first half of the night, and Dad, Dave and I the second. Dad always slept in his clothes, and he used to think some nights that the others came in before time. It was terrible going out, half awake, to tramp round that paddock from fire to fire, from hour to hour, shouting and yelling. And how we used to long for daybreak! Whenever we sat down quietly together for a few minutes we would hear the dull thud! thud! thud!—the kangaroo’s footstep.

At last we each carried a kerosene tin, slung like a kettle-drum, and belted it with a waddy—Dad’s idea. He himself manipulated an old bell that he had found on a bullock’s grave, and made a splendid noise with it.

It was a hard struggle, but we succeeded in saving the bulk of the barley, and cut it down with a scythe and three reaping-hooks. The girls helped to bind it, and Jimmy Mulcahy carted it in return for three days’ binding Dad put in for him. The stack wasn’t built twenty-four hours when a score of somebody’s crawling cattle ate their way up to their tails in it. We took the hint and put a sapling fence round it.

Again Dad decided to go up country for a while. He caught Emelina after breakfast, rolled up a blanket, told us to watch the stack, and started. The crows followed.

We were having dinner. Dave said, “Listen!” We listened, and it seemed as though all the crows and other feathered demons of the wide bush were engaged in a mighty scrimmage. “Dad’s back!” Dan said, and rushed out in the lead of a stampede.

Emelina was back, anyway, with the swag on, but Dad wasn’t. We caught her, and Dave pointed to white spots all over the saddle, and said—“Hanged if they haven’t been ridin’ her!”—meaning the crows.

Mother got anxious, and sent Dan to see what had happened. Dan found Dad, with his shirt off, at a pub on the main road, wanting to fight the publican for a hundred pounds, but couldn’t persuade him to come home. Two men brought him home that night on a sheep-hurdle, and he gave up the idea of going away.

After all, the barley turned out well—there was a good price that year, and we were able to run two wires round the paddock.

One day a bulky Government letter came. Dad looked surprised and pleased, and how his hand trembled as he broke the seal! “THE DEEDS!” he said, and all of us gathered round to look at them. Dave thought they were like the inside of a bear-skin covered with writing.

Dad said he would ride to town at once, and went for Emelina.

“Couldn’t y’ find her, Dad?” Dan said, seeing him return without the mare.

Dad cleared his throat, but didn’t answer. Mother asked him.

“Yes, I found her,” he said slowly, “dead.”

The crows had got her at last.

He wrapped the deeds in a piece of rag and walked.

There was nothing, scarcely, that he didn’t send out from town, and Jimmy Mulcahy and old Anderson many and many times after that borrowed our dray.

Now Dad regularly curses the deeds every mail-day, and wishes to Heaven he had never got them.

There had been a long stretch of dry weather, and we were cleaning out the waterhole. Dad was down the hole shovelling up the dirt; Joe squatted on the brink catching flies and letting them go again without their wings—a favourite amusement of his; while Dan and Dave cut a drain to turn the water that ran off the ridge into the hole—when it rained. Dad was feeling dry, and told Joe to fetch him a drink.

Joe said: “See first if this cove can fly with only one wing.” Then he went, but returned and said: “There’s no water in the bucket—Mother used the last drop to boil th’ punkins,” and renewed the fly-catching. Dad tried to spit, and was going to say something when Mother, half-way between the house and the waterhole, cried out that the grass paddock was all on fire. “So it is, Dad!” said Joe, slowly but surely dragging the head off a fly with finger and thumb.

Dad scrambled out of the hole and looked. “Good God!” was all he said. How he ran! All of us rushed after him except Joe—he couldn’t run very well, because the day before he had ridden fifteen miles on a poor horse, bare-back. When near the fire Dad stopped running to break a green bush. He hit upon a tough one. Dad was in a hurry. The bush wasn’t. Dad swore and tugged with all his might. Then the bush broke and Dad fell heavily upon his back and swore again.

To save the cockatoo fence that was round the cultivation was what was troubling Dad. Right and left we fought the fire with boughs. Hot! It was hellish hot! Whenever there was a lull in the wind we worked. Like a wind-mill Dad’s bough moved—and how he rushed for another when one was used up! Once we had the fire almost under control; but the wind rose again, and away went the flames higher and faster than ever.

“It’s no use,” said Dad at last, placing his hand on his head, and throwing down his bough. We did the same, then stood and watched the fence go. After supper we went out again and saw it still burning. Joe asked Dad if he didn’t think it was a splendid sight? Dad didn’t answer him—he didn’t seem conversational that night.

We decided to put the fence up again. Dan had sharpened the axe with a broken file, and he and Dad were about to start when Mother asked them what was to be done about flour? She said she had shaken the bag to get enough to make scones for that morning’s breakfast, and unless some was got somewhere there would be no bread for dinner.

Dad reflected, while Dan felt the edge on the axe with his thumb.

Dad said, “Won’t Missus Dwyer let you have a dishful until we get some?”

“No,” Mother answered; “I can’t ask her until we send back what we owe them.”

Dad reflected again. “The Andersons, then?” he said.

Mother shook her head and asked what good there was it sending to them when they, only that morning, had sent to her for some?

“Well, we must do the best we can at present,” Dad answered, “and I’ll go to the store this evening and see what is to be done.”

Putting the fence up again in the hurry that Dad was in was the very devil! He felled the saplings—and such saplings!—trees many of them were—while we, “all of a muck of sweat,” dragged them into line. Dad worked like a horse himself, and expected us to do the same. “Never mind staring about you,” he’d say, if he caught us looking at the sun to see if it were coming dinner-time—“there’s no time to lose if we want to get the fence up and a crop in.”

Dan worked nearly as hard as Dad until he dropped the butt-end of a heavy sapling on his foot, which made him hop about on one leg and say that he was sick and tired of the dashed fence. Then he argued with Dad, and declared that it would be far better to put a wire-fence up at once, and be done with it, instead of wasting time over a thing that would only be burnt down again. “How long,” he said, “will it take to get the posts? Not a week,” and he hit the ground disgustedly with a piece of stick he had in his hand.

“Confound it!” Dad said, “haven’t you got any sense, boy? What earthly use would a wire-fence be without any wire in it?”

Then we knocked off and went to dinner.

No one appeared in any humour to talk at the table. Mother sat silently at the end and poured out the tea while Dad, at the head, served the pumpkin and divided what cold meat there was. Mother wouldn’t have any meat—one of us would have to go without if she had taken any.

I don’t know if it was on account of Dan arguing with him, or if it was because there was no bread for dinner, that Dad was in a bad temper; anyway, he swore at Joe for coming to the table with dirty hands. Joe cried and said that he couldn’t wash them when Dave, as soon as he had washed his, had thrown the water out. Then Dad scowled at Dave, and Joe passed his plate along for more pumpkin.

Dinner was almost over when Dan, still looking hungry, grinned and asked Dave if he wasn’t going to have some bread? Whereupon Dad jumped up in a tearing passion. “D—n your insolence!” he said to Dan, “make a jest of it, would you?”

“Who’s jestin’?” Dan answered and grinned again.

“Go!” said Dad, furiously, pointing to the door, “leave my roof, you thankless dog!”

Dan went that night.

It was only upon Dad promising faithfully to reduce his account within two months that the storekeeper let us have another bag of flour on credit. And what a change that bag of flour wrought! How cheerful the place became all at once! And how enthusiastically Dad spoke of the farm and the prospects of the coming season!

Four months had gone by. The fence had been up some time and ten acres of wheat put in; but there had been no rain, and not a grain had come up, or was likely to.

Nothing had been heard of Dan since his departure. Dad spoke about him to Mother. “The scamp!” he said, “to leave me just when I wanted help—after all the years I’ve slaved to feed him and clothe him, see what thanks I get! but, mark my word, he’ll be glad to come back yet.” But Mother would never say anything against Dan.

The weather continued dry. The wheat didn’t come up, and Dad became despondent again.

The storekeeper called every week and reminded Dad of his promise. “I would give it you willingly,” Dad would say, “if I had it, Mr. Rice; but what can I do? You can’t knock blood out of a stone.”

We ran short of tea, and Dad thought to buy more with the money Anderson owed him for some fencing he had done; but when he asked for it, Anderson was very sorry he hadn’t got it just then, but promised to let him have it as soon as he could sell his chaff. When Mother heard Anderson couldn’t pay, she did cry, and said there wasn’t a bit of sugar in the house, nor enough cotton to mend the children’s bits of clothes.

We couldn’t very well go without tea, so Dad showed Mother how to make a new kind. He roasted a slice of bread on the fire till it was like a black coal, then poured the boiling water over it and let it “draw” well. Dad said it had a capital flavour—he liked it.

Dave’s only pair of pants were pretty well worn off him; Joe hadn’t a decent coat for Sunday; Dad himself wore a pair of boots with soles tied on with wire; and Mother fell sick. Dad did all he could—waited on her, and talked hopefully of the fortune which would come to us some day; but once, when talking to Dave, he broke down, and said he didn’t, in the name of the Almighty God, know what he would do! Dave couldn’t say anything—he moped about, too, and home somehow didn’t seem like home at all.

When Mother was sick and Dad’s time was mostly taken up nursing her; when there was nothing, scarcely, in the house; when, in fact, the wolf was at the very door;—Dan came home with a pocket full of money and swag full of greasy clothes. How Dad shook him by the hand and welcomed him back! And how Dan talked of “tallies”, “belly-wool”, and “ringers” and implored Dad, over and over again, to go shearing, or rolling up, or branding—anything rather than work and starve on the selection.

That’s fifteen years ago, and Dad is still on the farm.

It had been a bleak July day, and as night came on a bitter westerly howled through the trees. Cold! wasn’t it cold! The pigs in the sty, hungry and half-fed (we wanted for ourselves the few pumpkins that had survived the drought) fought savagely with each other for shelter, and squealed all the time like—well, like pigs. The cows and calves left the place to seek shelter away in the mountains; while the draught horses, their hair standing up like barbed-wire, leaned sadly over the fence and gazed up at the green lucerne. Joe went about shivering in an old coat of Dad’s with only one sleeve to it—a calf had fancied the other one day that Dad hung it on a post as a mark to go by while ploughing.

“My! it’ll be a stinger to-night,” Dad remarked to Mrs. Brown—who sat, cold-looking, on the sofa—as he staggered inside with an immense log for the fire. A log! Nearer a whole tree! But wood was nothing in Dad’s eyes.

Mrs. Brown had been at our place five or six days. Old Brown called occasionally to see her, so we knew they couldn’t have quarrelled. Sometimes she did a little house-work, but more often she didn’t. We talked it over together, but couldn’t make it out. Joe asked Mother, but she had no idea—so she said. We were full up, as Dave put it, of Mrs. Brown, and wished her out of the place. She had taken to ordering us about, as though she had something to do with us.

After supper we sat round the fire—as near to it as we could without burning ourselves—Mrs. Brown and all, and listened to the wind whistling outside. Ah, it was pleasant beside the fire listening to the wind! When Dad had warmed himself back and front he turned to us and said:

“Now, boys, we must go directly and light some fires and keep those wallabies back.”

That was a shock to us, and we looked at him to see if he were really in earnest. He was, and as serious as a judge.

“To-night!” Dave answered, surprisedly—“why to-night any more than last night or the night before? Thought you had decided to let them rip?”

“Yes, but we might as well keep them off a bit longer.”

“But there’s no wheat there for them to get now. So what’s the good of watching them? There’s no sense in that.”

Dad was immovable.

“Anyway”—whined Joe—“I’m not going—not a night like this—not when I ain’t got boots.”

That vexed Dad. “Hold your tongue, sir!” he said—“you’ll do as you’re told.”

But Dave hadn’t finished. “I’ve been following that harrow since sunrise this morning,” he said, “and now you want me to go chasing wallabies about in the dark, a night like this, and for nothing else but to keep them from eating the ground. It’s always the way here, the more one does the more he’s wanted to do,” and he commenced to cry. Mrs. Brown had something to say. She agreed with Dad and thought we ought to go, as the wheat might spring up again.

“Pshah!” Dave blurted out between his sobs, while we thought of telling her to shut her mouth.

Slowly and reluctantly we left that roaring fireside to accompany Dad that bitter night. It was a night!—dark as pitch, silent, forlorn and forbidding, and colder than the busiest morgue. And just to keep wallabies from eating nothing! They had eaten all the wheat—every blade of it—and the grass as well. What they would start on next—ourselves or the cart-harness—wasn’t quite clear.

We stumbled along in the dark one behind the other, with our hands stuffed into our trousers. Dad was in the lead, and poor Joe, bare-shinned and bootless, in the rear. Now and again he tramped on a Bathurst-burr, and, in sitting down to extract the prickle, would receive a cluster of them elsewhere. When he escaped the burr it was only to knock his shin against a log or leave a toe-nail or two clinging to a stone. Joe howled, but the wind howled louder, and blew and blew.

Dave, in pausing to wait on Joe, would mutter:

“To hell with everything! Whatever he wants bringing us out a night like this, I’m damned if I know!”

Dad couldn’t see very well in the dark, and on this night couldn’t see at all, so he walked up against one of the old draught horses that had fallen asleep gazing at the lucerne. And what a fright they both got! The old horse took it worse than Dad—who only tumbled down—for he plunged as though the devil had grabbed him, and fell over the fence, twisting every leg he had in the wires. How the brute struggled! We stood and listened to him. After kicking panels of the fence down and smashing every wire in it, he got loose and made off, taking most of it with him.

“That’s one wallaby on the wheat, anyway,” Dave muttered, and we giggled. We understood Dave; but Dad didn’t open his mouth.

We lost no time lighting the fires. Then we walked through the “wheat” and wallabies! May Satan reprove me if I exaggerate their number by one solitary pair of ears—but from the row and scatter they made there were a million.

Dad told Joe, at last, he could go to sleep if he liked, at the fire. Joe went to sleep—how, I don’t know. Then Dad sat beside him, and for long intervals would stare silently into the darkness. Sometimes a string of the vermin would hop past close to the fire, and another time a curlew would come near and screech its ghostly wail, but he never noticed them. Yet he seemed to be listening.

We mooched around from fire to fire, hour after hour, and when we wearied of heaving fire-sticks at the enemy we sat on our heels and cursed the wind, and the winter, and the night-birds alternately. It was a lonely, wretched occupation.

Now and again Dad would leave his fire to ask us if we could hear a noise. We couldn’t, except that of wallabies and mopokes. Then he would go back and listen again. He was restless, and, somehow, his heart wasn’t in the wallabies at all. Dave couldn’t make him out.

The night wore on. By-and-by there was a sharp rattle of wires, then a rustling noise, and Sal appeared in the glare of the fire. “Dad!” she said. That was all. Without a word, Dad bounced up and went back to the house with her.

“Something’s up!” Dave said, and, half-anxious, half-afraid, we gazed into the fire and thought and thought. Then we stared, nervously, into the night, and listened for Dad’s return, but heard only the wind and the mopoke.

At dawn he appeared again, with a broad smile on his face, and told us that mother had got another baby—a fine little chap. Then we knew why Mrs. Brown had been staying at our place.

Supper was over at Shingle Hut, and we were all seated round the fire—all except Joe. He was mousing. He stood on the sofa with one ear to the wall in a listening attitude, and brandished a table-fork. There were mice—mobs of them—between the slabs and the paper—layers of newspapers that had been pasted one on the other for years until they were an inch thick; and whenever Joe located a mouse he drove the fork into the wall and pinned it—or reckoned he did.

Dad sat pensively at one corner of the fireplace—Dave at the other with his elbows on his knees and his chin resting in his palms.

“Think you could ride a race, Dave?” asked Dad.

“Yairs,” answered Dave, without taking his eyes off the fire, or his chin from his palms—“could, I suppose, if I’d a pair o’ lighter boots ’n these.”

Again they reflected.

Joe triumphantly held up the mutilated form of a murdered mouse and invited the household to “Look!” No one heeded him.

“Would your Mother’s go on you?”

“Might,” and Dave spat into the fire.

“Anyway,” Dad went on, “we must have a go at this handicap with the old mare; it’s worth trying for, and, believe me, now! she’ll surprise a few of their flash hacks, will Bess.”

“Yairs, she can go all right.” And Dave spat again into the fire.

“Go! I’ve never known anything to keep up with her. Why, bless my soul, seventeen years ago, when old Redwood owned her, there wasn’t a horse in the district could come within coo-ee of her. All she wants is a few feeds of corn and a gallop or two, and mark my words she’ll show some of them the way.”

Some horse-races were being promoted by the shanty-keeper at the Overhaul—seven miles from our selection. They were the first of the kind held in the district, and the stake for the principal event was five pounds. It wasn’t because Dad was a racing man or subject to turf hallucinations in any way that he thought of preparing Bess for the meeting. We sadly needed those five pounds, and, as Dad put it, if the mare could only win, it would be an easier and much quicker way of making a bit of money than waiting for a crop to grow.

Bess was hobbled and put into a two-acre paddock near the house. We put her there because of her wisdom. She was a chestnut, full of villainy, an absolutely incorrigible old rogue. If at any time she was wanted when in the grass paddock, it required the lot of us from Dad down to yard her, as well as the dogs, and every other dog in the neighbourhood. Not that she had any brumby element in her—she would have been easier to yard if she had—but she would drive steadily enough, alone or with other horses, until she saw the yard, when she would turn and deliberately walk away. If we walked to head her she beat us by half a length; if we ran she ran, and stopped when we stopped. That was the aggravating part of her! When it was only to go to the store or the post-office that we wanted her, we could have walked there and back a dozen times before we could run her down; but, somehow, we generally preferred to work hard catching her rather than walk.

When we had spent half the day hunting for the curry-comb, which we didn’t find, Dad began to rub Bess down with a corn-cob—a shelled one—and trim her up a bit. He pulled her tail and cut the hair off her heels with a knife; then he gave her some corn to eat, and told Joe he was to have a bundle of thistles cut for her every night. Now and again, while grooming her, Dad would step back a few paces and look upon her with pride.

“There’s great breeding in the old mare,” he would say, “great breeding; look at the shoulder on her, and the loin she has; and where did ever you see a horse with the same nostril? Believe me, she’ll surprise a few of them!”

We began to regard Bess with profound respect; hitherto we had been accustomed to pelt her with potatoes and blue-metal.

The only thing likely to prejudice her chance in the race, Dad reckoned, was a small sore on her back about the size of a foal’s foot. She had had that sore for upwards of ten years to our knowledge, but Dad hoped to have it cured before the race came off with a never-failing remedy he had discovered—burnt leather and fat.

Every day, along with Dad, we would stand on the fence near the house to watch Dave gallop Bess from the bottom of the lane to the barn—about a mile. We could always see him start, but immediately after he would disappear down a big gully, and we would see nothing more of the gallop till he came to within a hundred yards of us. And wouldn’t Bess bend to it once she got up the hill, and fly past with Dave in the stirrups watching her shadow!—when there was one: she was a little too fine to throw a shadow always. And when Dave and Bess had got back and Joe had led her round the yard a few times, Dad would rub the corn-cob over her again and apply more burnt-leather and fat to her back.

On the morning preceding the race Dad decided to send Bess over three miles to improve her wind. Dave took her to the crossing at the creek—supposed to be three miles from Shingle Hut, but it might have been four or it might have been five, and there was a stony ridge on the way.

We mounted the fence and waited. Tommy Wilkie came along riding a plough-horse. He waited too.

“Ought to be coming now,” Dad observed, and Wilkie got excited. He said he would go and wait in the gully and race Dave home. “Race him home!” Dad chuckled, as Tommy cantered off, “he’ll never see the way Bess goes.” Then we all laughed.

Just as someone cried “Here he is!” Dave turned the corner into the lane, and Joe fell off the fence and pulled Dad with him. Dad damned him and scrambled up again as fast as he could. After a while Tommy Wilkie hove in sight amid a cloud of dust. Then came Dave at scarcely faster than a trot, and flogging all he knew with a piece of greenhide plough-rein. Bess was all-out and floundering. There was about two hundred yards yet to cover. Dave kept at her—thud! thud! Slower and slower she came. “Damn the fellow!” Dad said; “what’s he beating her for?” “Stop it, you fool!” he shouted. But Dave sat down on her for the final effort and applied the hide faster and faster. Dad crunched his teeth. Once—twice—three times Bess changed her stride, then struck a branch-root of a tree that projected a few inches above ground, and over she went—crash! Dave fell on his head and lay spread out, motionless. We picked him up and carried him inside, and when Mother saw blood on him she fainted straight off without waiting to know if it were his own or not. Both looked as good as dead; but Dad, with a bucket of water, soon brought them round again.

It was scarcely dawn when we began preparing for a start to the races. Dave, after spending fully an hour trying in vain to pull on Mother’s elastic-side boots, decided to ride in his own heavy bluchers. We went with Dad in the dray. Mother wouldn’t go; she said she didn’t want to see her son get killed, and warned Dad that if anything happened the blame would for ever be on his head.

We arrived at the Overhaul in good time. Dad took the horse out of the dray and tied him to a tree. Dave led Bess about, and we stood and watched the shanty-keeper unpacking gingerbeer. Joe asked Dad for sixpence to buy some, but Dad hadn’t any small change. We remained in front of the booth through most of the day, and ran after any corks that popped out and handed them in again to the shanty-keeper. He didn’t offer us anything—not a thing!

“Saddle up for the Overhaul Handicap!” was at last sung out, and Dad, saddle on arm, advanced to where Dave was walking Bess about. They saddled up and Dave mounted, looking as pale as death.

“I don’t like ridin’ in these boots a bit,” he said, with a quiver in his voice.

“Wot’s up with ’em?” Dad asked.

“They’re too big altogether.”

“Well, take ’em off then!”

Dave jumped down and pulled them off-leaving his socks on.

More than a dozen horses went out, and when the starter said “Off!” didn’t they go! Our eyes at once followed Bess. Dave was at her right from the jump—the very opposite to what Dad had told him. In the first furlong she put fully twenty yards of daylight between herself and the field—she came after the field. At the back of the course you could see the whole of Kyle’s selection and two of Jerry Keefe’s hay-stacks between her and the others. We didn’t follow her any further.

After the race was won and they had cheered the winner, Dad wasn’t to be found anywhere.

Dave sat on the grass quite exhausted. “Ain’t y’ goin’ to pull the saddle off?” Joe asked.

“No,” he said. “I ain’t. You don’t want everyone to see her back, do you?”

Joe wished he had sixpence.

About an hour afterwards Dad came staggering along arm-in-arm with another man—an old fencing-mate of his, so he made out.

“Thur yar,” he said, taking off his hat and striking Bess on the rump with it; “besh bred mare in the worl’.”

The fencing-mate looked at her, but didn’t say anything; he couldn’t.

“Eh?” Dad went on; “say sh’ain’t? L’ere-ever y’ name is—betcher pound sh’is.”

Then a jeering and laughing crowd gathered round, and Dave wished he hadn’t come to the races.

“She ain’t well,” said a tall man to Dad—“short in her gallops.” Then a short, bulky individual without whiskers shoved his face up into Dad’s and asked him if Bess was a mare or a cow. Dad became excited, and only that old Anderson came forward and took him away there must have been a row.

Anderson put him in the dray and drove it home to Shingle Hut.

Dad reckons now that there is nothing in horse-racing, and declares it a fraud. He says, further, that an honest man, by training and racing a horse, is only helping to feed and fatten the rogues and vagabonds that live on the sport.

It was early in the day. Traveller after traveller was trudging by Shingle Hut. One who carried no swag halted at the rails and came in. He asked Dad for a job. “I dunno,” Dad answered—“What wages would you want?” The man said he wouldn’t want any. Dad engaged him at once.

And such a man! Tall, bony, heavy-jawed, shaven with a reaping-hook, apparently. He had a thick crop of black hair—shaggy, unkempt, and full of grease, grass, and fragments of dry gum-leaves. On his head were two old felt hats—one sewn inside the other. On his back a shirt made from a piece of blue blanket, with white cotton stitches striding up and down it like lines of fencing. His trousers were gloom itself; they were a problem, and bore reliable evidence of his industry. No ordinary person would consider himself out of work while in them. And the new-comer was no ordinary person. He seemed to have all the woe of the world upon him; he was as sad and weird-looking as a widow out in the wet.

In the yard was a large heap of firewood—remarkable truth!—which Dad told him to chop up. He began. And how he worked! The axe rang again—particularly when it left the handle—and pieces of wood scattered everywhere. Dad watched him chopping for a while, then went with Dave to pull corn.

For hours the man chopped away without once looking at the sun. Mother came out. Joy! She had never seen so much wood cut before. She was delighted. She made a cup of tea and took it to the man, and apologised for having no sugar to put in it. He paid no attention to her; he worked harder. Mother waited, holding the tea in her hand. A lump of wood nearly as big as a shingle flew up and shaved her left ear. She put the tea on the ground and went in search of eggs for dinner. (We were out of meat—the kangaroo-dog was lame. He had got “ripped” the last time we killed.)

The tea remained on the ground. Chips fell into it. The dog saw it. He limped towards it eagerly, and dipped the point of his nose in it. It burnt him. An aged rooster strutted along and looked sideways at it. He distrusted it and went away. It attracted the pig—a sow with nine young ones. She waddled up, and poked the cup over with her nose; then she sat down on it, while the family joyously gathered round the saucer. Still the man chopped on.

Mother returned—without any eggs. She rescued the crockery from the pigs and turned curiously to the man. She said, “Why, you’ve let them take the tea!” No answer. She wondered.

Suddenly, and for the fiftieth time, the axe flew off. The man held the handle and stared at the woodheap. Mother watched him. He removed his hats, and looked inside them. He remained looking inside them.

Mother watched him more closely. His lips moved. He said, “Listen to them! They’re coming! I knew they’d follow!”

“Who?” asked Mother, trembling slightly.

“They’re in the wood!” he went on. “Ha, ha! I’ve got them. They’ll never get out; Never get out!”

Mother fled, screaming. She ran inside and called the children. Sal assisted her. They trooped in like wallabies—all but Joe. He was away earning money. He was getting a shilling a week from Maloney, for chasing cockatoos from the corn.

They closed and barricaded the doors, and Sal took down the gun, which Mother made her hide beneath the bed. They sat listening, anxiously and intently. The wind began to rise. A lump of soot fell from the chimney into the fireplace—where there was no fire. Mother shuddered. Some more fell. Mother jumped to her feet. So did Sal. They looked at each other in dismay. The children began to cry. The chain for hanging the kettle on started swinging to and fro. Mother’s knees gave way. The chain continued swinging. A pair of bare legs came down into the fireplace—they were curled round the chain. Mother collapsed. Sal screamed, and ran to the door, but couldn’t open it. The legs left the chain and dangled in the air. Sal called “Murder!”

Her cry was answered. It was Joe, who had been over at Maloney’s making his fortune. He came to the rescue. He dropped out of the chimney and shook himself. Sal stared at him. He was calm and covered from head to foot with soot and dirt. He looked round and said, “Thought yuz could keep me out, did’n’y’?” Sal could only look at him. “I saw yuz all run in,” he was saying, when Sal thought of Mother, and sprang to her. Sal shook her, and slapped her, and threw water on her till she sat up and stared about. Then Joe stared.

Dad came in for dinner—which, of course, wasn’t ready. Mother began to cry, and asked him what he meant by keeping a madman on the place, and told him she knew he wanted to have them all murdered. Dad didn’t understand. Sal explained. Then he went out and told the man to “Clear!” The man simply said, “No.”

“Go on, now!” Dad said, pointing to the rails. The man smiled at the wood-heap as he worked. Dad waited. “Ain’t y’ going?” he repeated.

“Leave me alone when I’m chopping wood for the missus,” the man answered; then smiled and muttered to himself. Dad left him alone and went inside wondering.

Next day Mother and Dad were talking at the barn. Mother, bare-headed, was holding some eggs in her apron. Dad was leaning on a hoe.

“I am afraid of him,” Mother said; “it’s not right you should keep him about the place. No one’s safe with such a man. Some day he’ll take it in his head to kill us all, and then—”

“Tut, tut, woman; poor old Jack! he’s harmless as a baby.”

“All right,” (sullenly); “you’ll see!”

Dad laughed and went away with the hoe on his shoulder to cut burr.

Middle of summer. Dad and Dave in the paddock mowing lucerne. Jack sinking post-holes for a milking-yard close to the house. Joe at intervals stealing behind him to prick him with straws through a rent in the rear of his patched moleskins. Little Bill—in readiness to run—standing off, enjoying the sport.

Inside the house sat Mother and Sal, sewing and talking of Maloney’s new baby.

“Dear me,” said Mother; “it’s the tiniest mite of a thing I ever saw; why, bless me, anyone of y’ at its age would have made three of—”

“Mind, Mother!” Sal shrieked, jumping up on the sofa. Mother screamed and mounted the table. Both gasped for breath, and leaning cautiously over peeped down at a big black snake which had glided in at the front door. Then, pale and scared-looking, they stared across at each other.

The snake crawled over to the safe and drank up some milk which had been spilt on the floor. Mother saw its full length and groaned. The snake wriggled to the leg of the table.

“Look out!” cried Sal, gathering up her skirts and dancing about on the sofa.

Mother squealed hysterically.

Joe appeared. He laughed.

“You wretch!” Mother yelled. “Run!—run, and fetch your father!”

Joe went and brought Jack.

“Oh-h, my God!”—Mother moaned, as Jack stood at the door, staring strangely at her. “Kill it!—why don’t he kill it?”

Jack didn’t move, but talked to himself. Mother shuddered.

The reptile crawled to the bedroom door. Then for the first time the man’s eyes rested upon it. It glided into the bedroom, and Mother and Sal ran off for Dad.

Jack fixed his eyes on the snake and continued muttering to himself. Several times it made an attempt to mount the dressing-table. Finally it succeeded. Suddenly Jack’s demeanour changed. He threw off his ragged hat and talked wildly. A fearful expression filled his ugly features. His voice altered.

“You’re the Devil!” he said; “The Devil! The Devil! The missus brought you—ah-h-h!”

The snake’s head passed behind the looking-glass. Jack drew nearer, clenching his fists and gesticulating. As he did he came full before the looking-glass and saw, perhaps for the first time in his life, his own image. An unearthly howl came from him. “Me father!” he shouted, and bolted from the house.

Dad came in with the long-handled shovel, swung it about the room, and smashed pieces off the cradle, and tore the bed-curtains down, and made a great noise altogether. Finally, he killed the snake and put it on the fire; and Joe and the cat watched it wriggle on the hot coals.

Meanwhile, Jack, bare-headed, rushed across the yard. He ran over little Bill, and tumbled through the wire-fence on to the broad of his back. He roared like a wild beast, clutched at space, spat, and kicked his heels in the air.

“Let me up!—Ah-h-h!—let go me throat!” he hissed.

The dog ran over and barked at him. He found his feet again, and, making off, ran through the wheat, glancing back over his shoulder as he tore along. He crossed into the grass paddock, and running to a big tree dodged round and round it. Then from tree to tree he went, and that evening at sundown, when Joe was bringing the cows home, Jack was still flying from “his father”.

After supper.

“I wonder now what the old fool saw in that snake to send him off his head like that?” Dad said, gazing wonderingly into the fire. “He sees plenty of them, goodness knows.”

“That wasn’t it. It wasn’t the snake at all,” Mother said; “there was madness in the man’s eyes all the while. I saw it the moment he came to the door.” She appealed to Sal.

“Nonsense!” said Dad; “Nonsense!” and he tried to laugh.

“Oh, of course it’s nonsense,” Mother went on; “everything I say is nonsense. It won’t be nonsense when you come home some day and find us all on the floor with our throats cut.”

“Pshaw!” Dad answered; “what’s the use of talking like that?” Then to Dave: “Go out and see if he’s in the barn!”

Dave fidgetted. He didn’t like the idea. Joe giggled.

“Surely you’re not frightened?” Dad shouted.

Dave coloured up.

“No—don’t think so,” he said; and, after a pause, “you go and see.”

It was Dad’s turn to feel uneasy. He pretended to straighten the fire, and coughed several times. “Perhaps it’s just as well,” he said, “to let him be to-night.”

Of course, Dad wasn’t afraid; he said he wasn’t, but he drove the pegs in the doors and windows before going to bed that night.

Next morning, Dad said to Dave and Joe, “Come ’long, and we’ll see where he’s got to.”

In a gully at the back of the grass-paddock they found him. He was ploughing—sitting astride the highest limb of a fallen tree, and, in a hoarse voice and strange, calling out—“Gee, Captain!—come here, Tidy!—wa-ay!”

“Blowed if I know,” Dad muttered, coming to a standstill. “Wonder if he is clean mad?”

Dave was speechless, and Joe began to tremble.

They listened. And as the man’s voice rang out in the quiet gully and the echoes rumbled round the ridge and the affrighted birds flew up, the place felt eerie somehow.

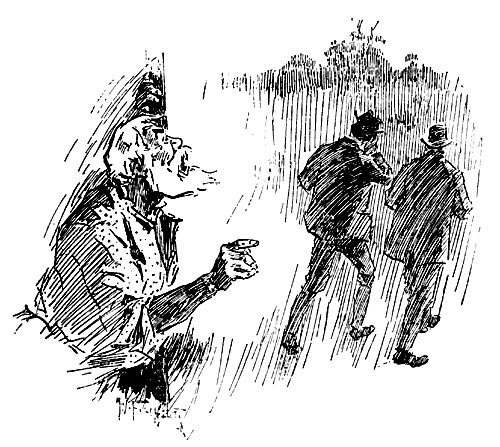

“It’s no use bein’ afraid of him,” Dad went on. “We must go and bounce him, that’s all.” But there was a tremor in Dad’s voice which Dave didn’t like.

“See if he knows us, anyway.”—and Dad shouted, “hey-y!”

Jack looked up and immediately scrambled from the limb. That was enough for Dave. He turned and made tracks. So did Dad and Joe. They ran. No one could have run harder. Terror overcame Joe. He squealed and grabbed hold of Dad’s shirt, which was ballooning in the wind.

“Let go!” Dad gasped. “Damn y’, let me go! ”—trying to shake him off. But Joe had great faith in his parent, and clung to him closely.

When they had covered a hundred yards or so, Dave glanced back, and seeing that Jack wasn’t pursuing them, stopped and chuckled at the others.

“Eh?” Dad said, completely winded—“Eh?” Then to Dave, when he got some breath:

“Well, you are an ass of a fellow. (Puff!). What th’ devil did y’ run f’?”

“Wot did I run f’? What did you run f’?”

“Bah!” and Dad boldly led the way back.

“Now look here (turning fiercely upon Joe), don’t you come catching hold of me again, or if y’ do I’ll knock y’r d—d head off! . . . Clear home altogether, and get under the bed if y’re as frightened as that.”

Joe slunk behind.

But when Dad did approach Jack, which wasn’t until he had talked a great deal to him across a big log, the latter didn’t show any desire to take life, but allowed himself to be escorted home and locked in the barn quietly enough.

Dad kept Jack confined in the barn several days, and if anyone approached the door or the cracks he would ask:

“Is me father there yet?”

“Your father’s dead and buried long ago, man,” Dad used to tell him.

“Yes,” he would say, “but he’s alive again. The missus keeps him in there”—indicating the house.

And sometimes when Dad was not about Joe would put his mouth to a crack and say:

“Here’s y’r father, Jack!” Then, like a caged beast, the man would howl and tramp up and down, his eyes starting out of his head, while Joe would bolt inside and tell Mother that “Jack’s getting out,” and nearly send her to her grave.

But one day Jack did get out, and, while Mother and Sal were ironing came to the door with the axe on his shoulder.

They dropped the irons and shrank into a corner and cowered piteously—too scared even to cry out.

He took no notice of them, but, moving stealthily on tip-toes, approached the bedroom door and peeped in. He paused just a moment to grip the axe with both hands. Then with a howl and a bound he entered the room and shattered the looking-glass into fragments.

He bent down and looked closely at the pieces.

“He’s dead now,” he said calmly, and walked out. Then he went to work at the post-holes again, just as though nothing had happened.

Fifteen years have passed since then, and the man is still at Shingle Hut. He was the best horse Dad ever had. He slaved from daylight till dark; keeps no Sunday; knows no companion; lives chiefly on meat and machine oil; domiciles in the barn; and has never asked for a rise in his wages. His name we never knew. We call him “Jack.” The neighbours called him “Cranky Jack.”

We always looked forward to Sunday. It was our day of sport. Once, I remember, we thought it would never come. We longed restlessly for it, and the more we longed the more it seemed to linger.

A meeting of selectors had been held; war declared against the marsupial; and a hunt on a grand scale arranged for this particular Sabbath. Of course those in the neighbourhood hunted the kangaroo every Sunday, but “on their own,” and always on foot, which had its fatigues. This was to be a raid en masse and on horseback. The whole country-side was to assemble at Shingle Hut and proceed thence. It assembled; and what a collection! Such a crowd! such gear! such a tame lot of horses! and such a motley swarm of lean, lank, lame kangaroo-dogs!

We were not ready. The crowd sat on their horses and waited at the slip-rails. Dogs trooped into the yard by the dozen. One pounced on a fowl; another lamed the pig; a trio put the cat up a peach-tree; one with a thirst mounted the water-cask and looked down it, while the bulk of the brutes trotted inside and disputed with Mother who should open the safe.

Dad loosed our three, and pleased they were to feel themselves free. They had been chained up all the week, with scarcely anything to eat. Dad didn’t believe in too much feeding. He had had wide experience in dogs and coursing “at home” on his grandfather’s large estates, and always found them fleetest when empty. Ours ought to have been fleet as locomotives.

Dave, showing a neat seat, rode out of the yard on Bess, fresh and fat and fit to run for a kingdom. They awaited Dad. He was standing beside his mount—Farmer, the plough-horse, who was arrayed in winkers with green-hide reins, and an old saddle with only one flap. He was holding an earnest argument with Joe . . . Still the crowd waited. Still Dad and Joe argued the point . . . There was a murmur and a movement and much merriment. Dad was coming; so was Joe—perched behind him, “double bank,” rapidly wiping the tears from his eyes with his knuckles.

Hooray! They were off. Paddy Maloney and Dave took the lead, heading for kangaroo country along the foot of Dead Man’s Mountain and through Smith’s paddock, where there was a low wire fence to negotiate. Paddy spread his coat over it and jumped his mare across. He was a horseman, was Pat. The others twisted a stick in the wires, and proceeded carefully to lead their horses over. When it came to Farmer’s turn he hesitated. Dad coaxed him. Slowly he put one leg across, as if feeling his way, and paused again. Joe was on his back behind the saddle. Dad tugged hard at the winkers. Farmer was inclined to withdraw his leg. Dad was determined not to let him. Farmer’s heel got caught against the wire, and he began to pull back and grunt—so did Dad. Both pulled hard. Anderson and old Brown ran to Dad’s assistance. The trio planted their heels in the ground and leaned back.

Joe became afraid. He clutched at the saddle and cried, “Let me off!” “Stick to him!” said Paddy Maloney, hopping over the fence, “Stick to him!” He kicked Farmer what he afterwards called “a sollicker on the tail.” Again he kicked him. Still Farmer strained and hung back. Once more he let him have it. Then—off flew the winkers, and over went Dad and Anderson and old Brown, and down rolled Joe and Farmer on the other side of the fence. The others leant against their horses and laughed the laugh of their lives. “Worse ’n a lot of d—d jackasses,” Dad was heard to say. They caught Farmer and led him to the fence again. He jumped it, and rose feet higher than he had any need to, and had not old Brown dodged him just when he did he would be a dead man now.

A little further on the huntsmen sighted a mob of kangaroos. Joy and excitement. A mob? It was a swarm! Away they hopped. Off scrambled the dogs, and off flew Paddy Maloney and Dave—the rest followed anyhow, and at varying speeds.

That all those dogs should have selected and followed the same kangaroo was sad and humiliating. And such a waif of a thing, too! Still, they stuck to it. For more than a mile, down a slope, the weedy marsupial outpaced them, but when it came to the hill the daylight between rapidly began to lessen. A few seconds more and all would have been over, but a straggling, stupid old ewe, belonging to an unneighbourly squatter, darted up from the shade of a tree right in the way of Maloney’s Brindle, who was leading. Brindle always preferred mutton to marsupial, so he let the latter slide and secured the ewe. The death-scene was most imposing. The ground around was strewn with small tufts of white wool. There was a complete circle of eager, wriggling dogs—all jammed together, heads down, and tails elevated. Not a scrap of the ewe was visible. Paddy Maloney jumped down and proceeded to batter the brutes vigorously with a waddy. As the others arrived, they joined him. The dogs were hungry, and fought for every inch of the sheep. Those not laid out were pulled away, and! when old Brown had dragged the last one off by the hind legs, all that was left of that ewe was four feet and some skin.

Dad shook his head and looked grave—so did Anderson. After a short rest they decided to divide into parties and work the ridges. A start was made. Dad’s contingent—consisting of himself and Joe, Paddy Maloney, Anderson, old Brown, and several others—started a mob. This time the dogs separated and scampered off in all directions. In quick time Brown’s black slut bailed up an “old man” full of fight. Nothing was more desirable. He was a monster, a king kangaroo; and as he raised himself to his full height on his toes and tail he looked formidable—a grand and majestic demon of the bush. The slut made no attempt to tackle him; she stood off with her tongue out. Several small dogs belonging to Anderson barked energetically at him, even venturing occasionally to run behind and bite his tail. But, further than grabbing them in his arms and embracing them, he took no notice. There he towered, his head back and chest well out, awaiting the horsemen. They came, shouting and hooraying. He faced them defiantly. Anderson, aglow with excitement, dismounted and aimed a lump of rock at his head, which laid out one of the little dogs. They pelted him with sticks and stones till their arms were tired, but they might just as well have pelted a dead cow. Paddy Maloney took out his stirrup. “Look out!” he cried. They looked out. Then, galloping up, he swung the iron at the marsupial, and nearly knocked his horse’s eye out.

Dad was disgusted. He and Joe approached the enemy on Farmer. Dad carried a short stick. The “old man” looked him straight in the face. Dad poked the stick at him. He promptly grabbed hold of it, and a piece of Dad’s hand as well. Farmer had not been in many battles—no Defence Force man ever owned him. He threw up his head and snorted, and commenced a retreat. The kangaroo followed him up and seized Dad by the shirt. Joe evinced signs of timidity. He lost faith in Dad, and, half jumping, half falling, he landed on the ground, and set out speedily for a tree. Dad lost the stick, and in attempting to brain the brute with his fist he overbalanced and fell out of the saddle. He struggled to his feet, and clutched his antagonist affectionately by both paws—standing well away. Backwards and forwards and round and round they moved. “Use your knife!” Anderson called out, getting further away himself. But Dad dared not relax his grip. Paddy Maloney ran behind the brute several times to lay him out with a waddy, but each time he turned and fled before striking the blow. Dad thought to force matters, and began kicking his assailant vigorously in the stomach. Such dull, heavy thuds! The kangaroo retaliated, putting Dad on the defensive. Dad displayed remarkable suppleness about the hips. At last the brute fixed his deadly toe in Dad’s belt.

It was an anxious moment, but the belt broke, and Dad breathed freely again. He was acting entirely on the defensive, but an awful consciousness of impending misfortune assailed him. His belt was gone, and—his trousers began to slip—slip—slip! He called wildly to the others for God’s sake to do something. They helped with advice. He yelled “Curs!” and “Cowards!” back at them. Still, as he danced around with his strange and ungainly partner, his trousers kept slipping—slipping. For the fiftieth time and more he glanced eagerly over his shoulder for some haven of safety. None was near. And then—oh, horror!—down they slid calmly and noiselessly. Poor Dad! He was at a disadvantage; his leg work was hampered. He was hobbled. Could he only get free of them altogether! But he couldn’t—his feet were large. He took a lesson from the foe and jumped—jumped this way and that way, and round about, while large drops of perspiration rolled off him. The small dogs displayed renewed and ridiculous ferocity, often mistaking Dad for the marsupial. At last Dad became exhausted—there was no spring left in him. Once he nearly went down. Twice he tripped. He staggered again—down he was going—down—down, down and down he fell! But at the same moment, and, as though they had dropped from the clouds, Brindle and five or six other dogs pounced on the “old man.” The rest may be imagined.

Dad lay on the ground to recover his wind, and when he mounted Farmer again and silently turned for home, Paddy Maloney was triumphantly seated on the carcase of the fallen enemy, exultingly explaining how he missed the brute’s head with the stirrup-iron, and claiming the tail.

One hot day, as we were finishing dinner, a sheriff’s bailiff rode up to the door. Norah saw him first. She was dressed up ready to go over to Mrs. Anderson’s to tea. Sometimes young Harrison had tea at Anderson’s—Thursdays, usually. This was Thursday; and Norah was starting early, because it was “a good step of a way”.

She reported the visitor. Dad left the table, munching some bread, and went out to him. Mother looked out of the door; Sal went to the window; Little Bill and Tom peeped through a crack; Dave remained at his dinner; and Joe knavishly seized the opportunity of exploring the table for leavings, finally seating himself in Dad’s place, and commencing where Dad had left off.

“Jury summons,” said the meek bailiff, extracting a paper from his breast-pocket, and reading, “Murtagh Joseph Rudd, selector, Shingle Hut . . . Correct?”

Dad nodded assent.

“Got any water?”

There wasn’t a drop in the cask, so Dad came in and asked Mother if there was any tea left. She pulled a long, solemn, Sunday-school face, and looked at Joe, who was holding the teapot upside-down, shaking the tea-leaves into his cup.

“Tea, Dad?” he chuckled—“by golly!”

Dad didn’t think it worth while going out to the bailiff again. He sent Joe.

“Not any at all?”

“Nothink,” said Joe.

“H’m! Nulla bona, eh?” And the Law smiled at its own joke and went off thirsty.

Thus it was that Dad came to be away one day when his great presence of mind and ability as a bush doctor was most required at Shingle Hut.

Dave took Dad’s place at the plough. One of the horses—a colt that Dad bought with the money he got for helping with Anderson’s crop—had only just been broken. He was bad at starting. When touched with the rein he would stand and wait until the old furrow-horse put in a few steps; then plunge to get ahead of him, and if a chain or a swingle-tree or something else didn’t break, and Dave kept the plough in, he ripped and tore along in style, bearing in and bearing out, and knocking the old horse about till that much-enduring animal became as cranky as himself, and the pace terrible. Down would go the plough-handles, and, with one tremendous pull on the reins, Dave would haul them back on to their rumps. Then he would rush up and kick the colt on the root of the tail, and if that didn’t make him put his leg over the chains and kick till he ran a hook into his heel and lamed himself, or broke something, it caused him to rear up and fall back on the plough and snort and strain and struggle till there was not a stitch left on him but the winkers.

Now, if Dave was noted for one thing more than another it was for his silence. He scarcely ever took the trouble to speak. He hated to be asked a question, and mostly answered by nodding his head. Yet, though he never seemed to practise, he could, when his blood was fairly up, swear with distinction and effect. On this occasion he swore through the whole afternoon without repeating himself.

Towards evening Joe took the reins and began to drive. He hadn’t gone once around when, just as the horses approached a big dead tree that had been left standing in the cultivation, he planted his left foot heavily upon a Bathurst-burr that had been cut and left lying. It clung to him. He hopped along on one leg, trying to kick it off; still it clung to him. He fell down. The horses and the tree got mixed up, and everything was confusion.

Dave abused Joe remorselessly. “Go on!” he howled, waving in the air a fistful of grass and weeds which he had pulled from the nose of the plough; “clear out of this altogether!—you’re only a damn nuisance.”

Joe’s eyes rested on the fistful of grass. They lit up suddenly.

“L-l-look out, Dave,” he stuttered; “y’-y’ got a s-s-snake.”

Dave dropped the grass promptly. A deaf-adder crawled out of it. Joe killed it. Dave looked closely at his hand, which was all scratches and scars. He looked at it again; then he sat on the beam of the plough, pale and miserable-looking.

“D-d-did it bite y’, Dave?” No answer.

Joe saw a chance to distinguish himself, and took it. He ran home, glad to be the bearer of the news, and told Mother that “Dave’s got bit by a adder—a sudden-death adder—right on top o’ the finger.”

How Mother screamed! “My God! whatever shall we do? Run quick,” she said, “and bring Mr. Maloney. Dear! oh dear! oh dear!”

Joe had not calculated on this injunction. He dropped his head and said sullenly: “Wot, walk all the way over there?”

Before he could say another word a tin-dish left a dinge on the back of his skull that will accompany him to his grave if he lives to be a thousand.

“You wretch, you! Why don’t you run when I tell you?”

Joe sprang in the air like a shot wallaby.

“I’ll not go at all now—y’ see!” he answered, starting to cry. Then Sal put on her hat and ran for Maloney.

Meanwhile Dave took the horses out, walked inside, and threw himself on the sofa without uttering a word. He felt ill.

Mother was in a paroxysm of fright. She threw her arms about frantically and cried for someone to come. At last she sat down and tried to think what she could do. She thought of the very thing, and ran for the carving-knife, which she handed to Dave with shut eyes. He motioned her with a disdainful movement of the elbow to take it away.

Would Maloney never come! He was coming, hat in hand, and running for dear life across the potato-paddock. Behind him was his man. Behind his man—Sal, out of breath. Behind her, Mrs. Maloney and the children.

“Phwat’s the thrubble?” cried Maloney. “Bit be a dif-adher? O, be the tares of war!” Then he asked Dave numerous questions as to how it happened, which Joe answered with promptitude and pride. Dave simply shrugged his shoulders and turned his face to the wall. Nothing was to be got out of him.

Maloney held a short consultation with himself. Then—“Hould up yer hand!” he said, bending over Dave with a knife. Dave thrust out his arm violently, knocked the instrument to the other side of the room, and kicked wickedly.

“The pison’s wurrkin’,” whispered Maloney quite loud.

“Oh, my gracious!” groaned Mother.

“The poor crathur,” said Mrs. Maloney.

There was a pause.

“Phwhat finger’s bit?” asked Maloney. Joe thought it was the littlest one of the lot.

He approached the sofa again, knife in hand.

“Show me yer finger,” he said to Dave.

For the first time Dave spoke. He said:

“Damn y’—what the devil do y’ want? Clear out and lea’ me ’lone.”

Maloney hesitated. There was a long silence. Dave commenced breathing heavily.

“It’s maikin’ ’m slape,” whispered Maloney, glancing over his shoulder at the women.

“Don’t let him! Don’t let him!” Mother wailed.

“Salvation to ’s all!” muttered Mrs. Maloney, piously crossing herself.

Maloney put away the knife and beckoned to his man, who was looking on from the door. They both took a firm hold of Dave and stood him upon his feet. He looked hard and contemptuously at Maloney for some seconds. Then with gravity and deliberation Dave said: “Now wot ’n th’ devil are y’ up t’? Are y’ mad?”

“Walk ’m along, Jaimes—walk ’m—along,” was all Maloney had to say. And out into the yard they marched him. How Dave did struggle to get away!—swearing and cursing Maloney for a cranky Irishman till he foamed at the mouth, all of which the other put down to snake-poison. Round and round the yard and up and down it they trotted him till long after dark, until there wasn’t a struggle left in him.

They placed him on the sofa again, Maloney keeping him awake with a strap. How Dave ground his teeth and kicked and swore whenever he felt that strap! And they sat and watched him.

It was late in the night when Dad came from town. He staggered in with the neck of a bottle showing out of his pocket. In his hand was a piece of paper wrapped round the end of some yards of sausage. The dog outside carried the other end.

“An’ ’e ishn’t dead?” Dad said, after hearing what had befallen Dave. “Don’ b’leevsh id—wuzhn’t bit. Die ’fore shun’own ifsh desh ad’er bish ‘m.”

“Bit!” Dave said bitterly, turning round to the surprise of everyone. “I never said I was bit. No one said I was—only those snivelling idiots and that pumpkin-headed Irish pig there.”

Maloney lowered his jaw and opened his eyes.

“Zhackly. Did’n’ I (hic) shayzo, ’Loney? Did’n’ I, eh, ol’ wom’n!” Dad mumbled, and dropped his chin on his chest.

Maloney began to take another view of the matter. He put a leading question to Joe.

“He muster been bit,” Joe answered, “’cuz he had the d-death adder in his hand.”

More silence.

“Mush die ’fore shun’own,” Dad murmured.

Maloney was thinking hard. At last he spoke. “Bridgy!” he cried, “where’s th’ childer?” Mrs. Maloney gathered them up.

Just then Dad seemed to be dreaming. He swayed about. His head hung lower, and he muttered, “Shen’l’m’n, yoush disharged wish shanksh y’cun’ry.”

The Maloneys left.